Adam Tooze's Blog, page 18

June 9, 2022

Chartbook 127 – The World Bank’s global take on the 1970s, stagflation and debt crises.

This week the World Bank announced that it is slashing its forecast for 2022 global growth to 2.9%, down from 5.7% in 2021. This is the sharpest deceleration in a post-recession recovery in 80 years.

The baseline scenario projects a slight re-acceleration 2023, but in the event of a severe Fed tightening, an energy embargo triggered by the war and continuing COVID issues in China, that number could fall to as low as 1.5 percent.

With inflation also running at record rates, comparisons are being drawn to stagflation of the 1970s. Heavy-weights like Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard have been to the fore in warning that inflation is now so rapid that to bring it under control may require a draconian monetary policy intervention.

This may well prove alarmist. Not only are the data on the degree of inflationary momentum ambiguous, but in the debate so far they are drawn overwhelmingly from the US and Europe.

The World Bank in the latest report on Global Economic Prospects for June 2022 takes a broader view. In a Special Focus section they take on the theme of Global Stagflation and the comparison to the 1970s. Their analysis, they claim, is the first to provide a

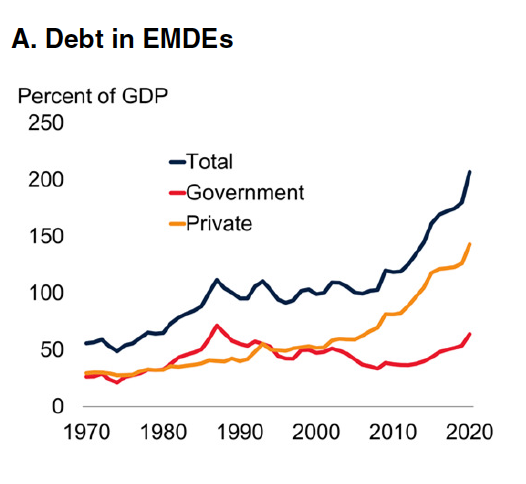

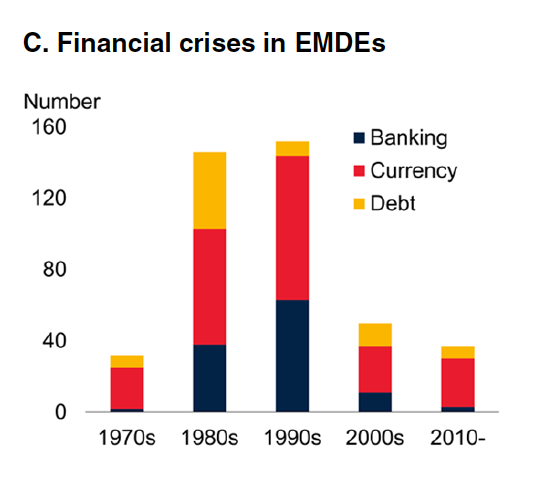

systematic comparison of the current juncture with the stagflationary period of the 1970s. The previous literature has mostly focused on a comparison of high inflation during that period with today’s inflationary challenges and studied the role of monetary policy and commodity price shocks in driving inflation in the two periods. This study considers the stagflation of the 1970s and examines the role of fiscal policy and broader structural differences in explaining weak output growth and high inflation. Second, in contrast to much of the earlier work, which has focused on the United States, this study presents a global perspective by examining the evidence of stagflation, and the challenges posed by it, for a broad set of countries.5 The threat of stagflation is global since the current combination of high inflation and weak growth is highly synchronized across many countries. Third, this Focus explicitly links the Emerging Market and Developing Economy debt buildup of the 1970s that culminated in the debt crises of the 1980s to the stagflation of that era and its eventual resolution in advanced economies. The 1970s witnessed the first global debt wave fueled by a prolonged period of accommodative monetary policies in major advanced economies. Since 2010, the global economy has been experiencing the largest, fastest, and most synchronized debt wave of the past five decades amid a protracted period of monetary policy accommodation. The study considers the lessons of the debt accumulation of the 1970s for the current debt wave.

As the World Bank remarks,

The current juncture resembles the early 1970s in three key respects: supply shocks and elevated global inflation in the near-term, preceded by a protracted period of highly accommodative monetary policy in major economies, together with recent marked fiscal expansion; prospects for weakening growth over the longer term, which echo the unforeseen slowdown in potential growth of the 1970s; and vulnerabilities in EMDEs to the monetary policy tightening by advanced economies that will be needed to rein in inflation.

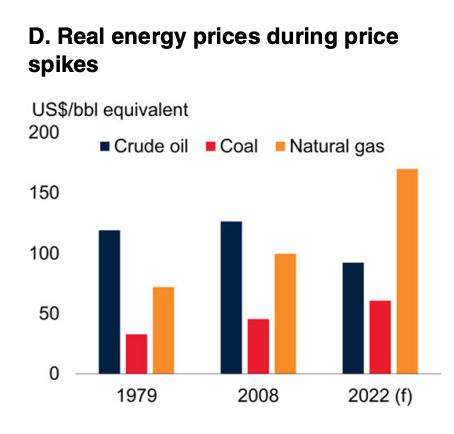

The energy price surge has rocked the entire world economy. In real terms the oil price shock of 2022 is in the same ballpark as 1979. The gas price shock is dramatically worse than anything previously seen.

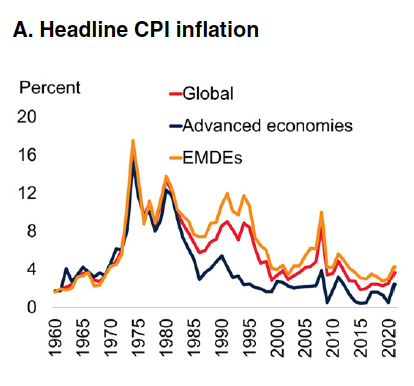

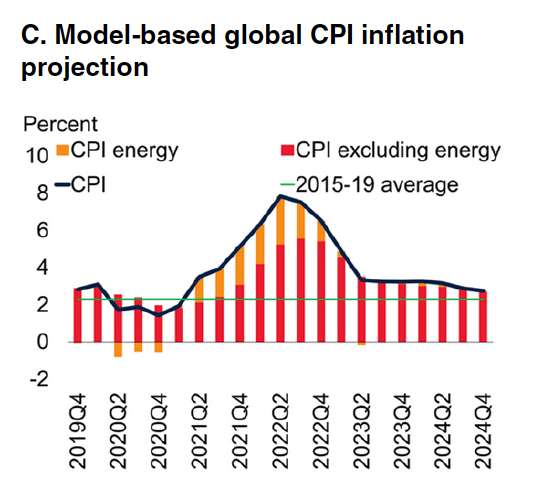

From a global point of view it is clear that though inflation has ticked up in recent months, following decades of lowflation, we are still a long way from the great inflation of the 1970s.

World Bank SF1.1 A.

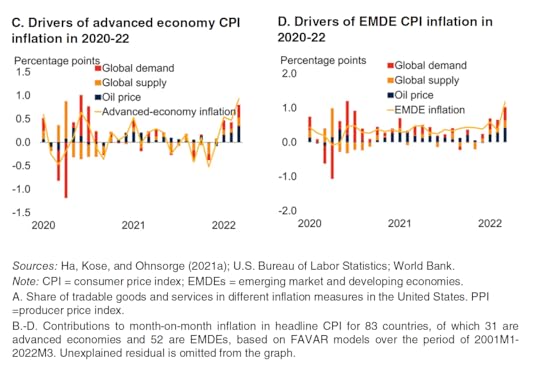

In both the advanced economies and emerging and developing economies, the World Bank analysis shows that the drivers of inflation in 2021-2022 are a cocktail of supply constraints, a demand shock and a surge in oil prices. In neither the advanced economies nor the emerging market world, are supply factors – the famous supply-chains – clearly dominant.

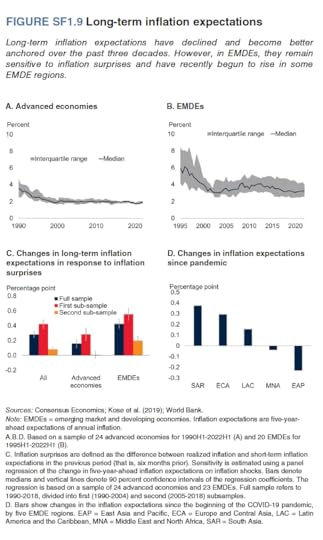

And despite this variety of shocks, long-term inflation expectations so far remain anchored both in the advanced economies and in the emerging market world.

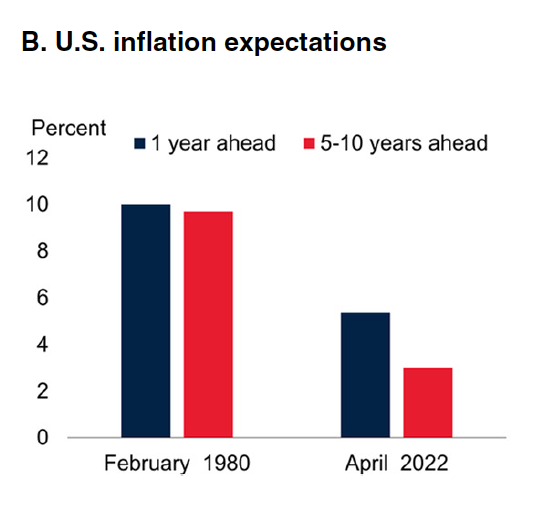

In the US, inflation expectations have significantly risen, especially over the 12-month time horizon. But they are no more than half the levels seen in February 1980.

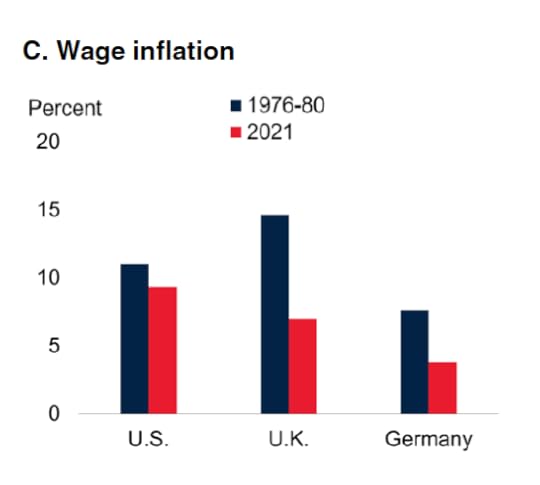

Wage inflation, which was a driver of wage-price spirals in the 1970s, is far more muted today, at least outside the US.

In the US, wage inflation is rapid, but remains behind price inflation, and, as the World Bank somewhat coyly remarks, in institutional terms there are huge differences between the 1970s and the present day. “Rigidities” are less pronounced, which is an unfortunate economist’s way of talking about the decline of organized labour and workers’ bargaining power.

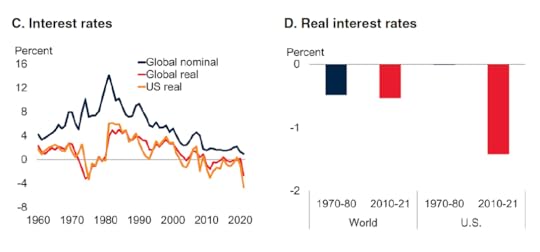

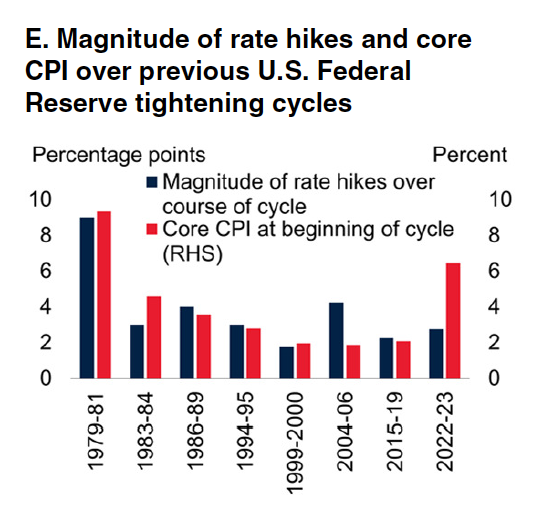

Part of the reason that markets are as relaxed as they are is, that if the Fed and the other central banks see fit to take action, they have plenty of scope to do so before needing to resort to Volcker-style shock therapy.

Right now, interest rates all over the world are in negative territory. In the US they are deeply so.

In the 1979-1981, the initial impact of the Volcker shock was simply to raise rates to the level of inflation. Then, as inflation rapidly slowed, interest rates surged to historic highs. We are a long, long way from that today.

What worries the World Bank is what happens if the Fed were to actually make use of its leeway to raise rates. Here too, the 1970s have lessons to teach. The World Bank’s worry is of a major emerging market and developing world debt crisis.

At that time, as the World Bank writes,

Low global real interest rates and the rapid development of syndicated loan markets encouraged a surge in EMDE debt, especially in Latin America and many low-income countries (LICs), especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Latin America, total external debt rose by 12 percentage points of GDP over the course of the decade while, in LICs, it rose by 18 percentage points of GDP. Much of this debt was in foreign currency and short-term, as capital flowed from oil exporters to EMDEs with large fiscal and current account deficits (figure SF1.5.C).

When the Volcker shock hit, it delivered a savage blow to emerging market borrowers, turning the 1980s into a decade of debt crises. The litany of financial crises in the 1990s was even worse, but now it was banking crises that were to the fore.

Despite COVID the number of emerging market and low-income country debt crises has never returned to the 1980s peak. But debt accumulation in the last fifteen years has been dramatic and a larger share of borrowing is susceptible to variable interest rates. From a share of c. 20 percent in the early 2000s, the variable rate component has risen to 35 percent.

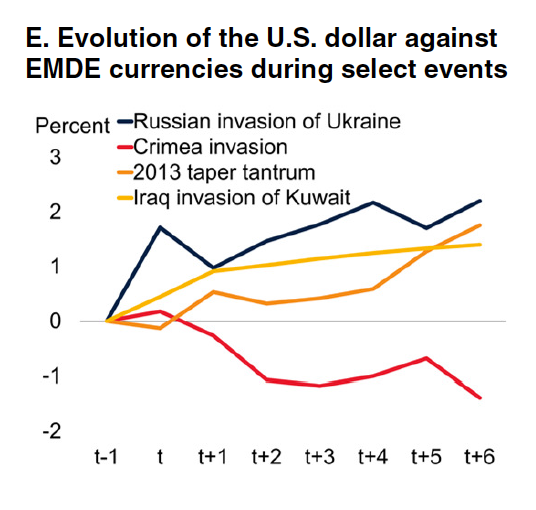

Even if dollar interest rates are still a long way away from imposing a real squeeze, the dollar itself poses problems.

In the 1970s following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the dollar devalued. By contrast, since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the dollar has strengthened sharply, exerting significant pressure on everyone who has borrowed in the currency, whether interest rate go up or not.

Those worst affected are emerging market and developing economies that are also commodity importers. They are being squeezed both by the appreciation of the dollar and the rise of commodity prices. And the bond markets are reacting. The spread paid by EMDE sovereigns that are commodity importers have surged by almost 250 basis points. Commodity exporters have seen a basis-point increase in their spreads of less than 100 points.

As far as the 1970s analogy in the advanced economies is concerned, the general impression conveyed by the World Bank’s analysis is that the similarities are more superficial than real. The World Bank expects global CPI inflation to fall back below 3 percent in 2023.

But the real question is what price will the world economy pay? As far as emerging market and developing market debt is concerned, the burden is far larger than it was in the 1970s. So too, of course, is the sophistication of their governance institutions. What Daniela Gabor calls the “Wall Street consensus” has sunk deep roots. The much-feared global COVID debt crisis of 2020 failed to arrive. Instead the accumulation of new debt went on. We may get lucky. There may be no tapering disaster in 2022-2024. But the World Bank alerts us to where the most serious risks lie. Along with the distributional question in rich countries, the main focus should be on ensuring that the tightening in the global dollar system does not impose intolerable pressure on its weakest links around the world.

***

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

June 6, 2022

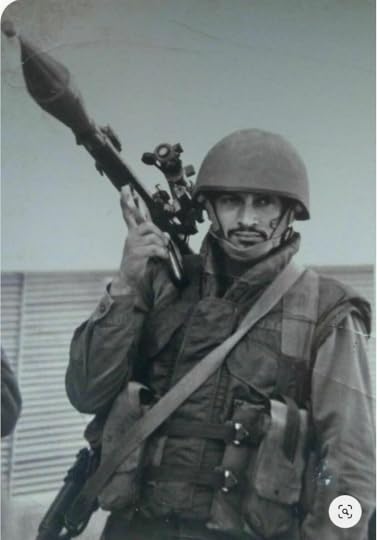

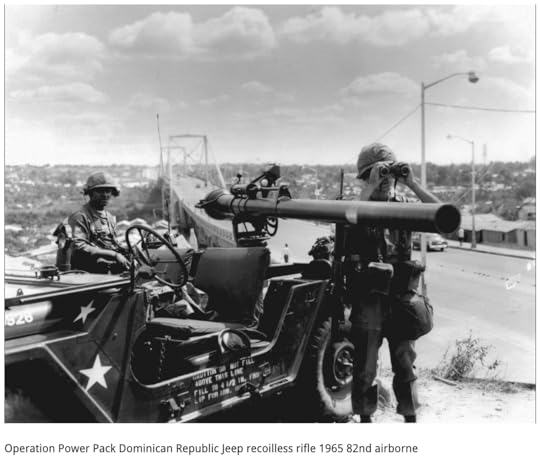

Chartbook #126: For the anniversary of D-Day – Blitzkrieg manquée? Or, a new mode of “firepower war”?

The successful Allied landings on the beaches of Normandy on 6 June 1944 stand as one of the defining events of mid twentieth-century history. D-Day ranks alongside the Marshall Plan, or the Manhattan project as one of the signal demonstrations of the potency of the Western democracies. The landings were as Churchill remarked to Eisenhower in awe-struck tones, “much the greatest thing we have ever attempted.” For those who honor the sacrifice and courage of the “greatest generation”, the beaches are a site of pilgrimage, the holy ground from which the “Great Crusade” for a new Europe was launched. The New York Times’s commentary on the 50th anniversary The Terrible and Sacred Shore” is a remarkable period piece. Not for nothing, the annual commemorations, now including the Germans, became for a while a fixture in trans-Atlantic diplomacy.

But why and how did D-Day succeed? The question has given postwar historians no peace. For all the solemnity and the weight of historical meaning loaded on the event, for military historians D-Day serves as a Rorschach blot, an open-ended, projective test of underlying assumptions and models of historical explanation. This review essay, which I first wrote back in 2017, seeks not to reconcile or synthesize the contending views, but to explore the logic of this perpetuum mobile of interpretation and reinterpretation.

Beyond the triumph of the landings and the enemy defeated, the D-Day literature has never found complacency easy to come by. The tactical performance of allied troops was inferior. The advance from the bridgeheads was disappointingly slow. Allied forces were halted on the German border over the winter of 1944-45 and did not breach the Rhine until March 1945. Meanwhile, Stalin’s Red Army surged across Eastern Europe towards Berlin. The frontline of the Cold War was defined by the sluggish advance that followed D-Day.

Some of the earliest commentators were scathing. Liddell Hart, J.F.C. Fuller, Chester Wilmont were all critical of both the generalship and the fighting power of the Allies. The 1950s and 1960s saw a wave of recrimination amongst the leading commanders of the invasion forces, divided above all over by the retrospective posturing of Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery. At stake was more than Montie’s status as a great commander. In his disagreements with Bradley and Eisenhower a more fundamental clash between hidebound British conservatism and the dash and glamour of American modernity was encapsulated. In 1983 Carlo D’Este’s Decision in Normandy not only adjudicated this argument, but provided a compelling narrative of how the postwar myth of Normandy and the controversy around it had taken shape. By then, however, the currents in the wider historiography had moved on. The argument between the Allies was displaced by invidious comparisons drawn between all of them and their Wehrmacht opponents. Whilst the wider historical literature moved in the 1980s to an ever more determined “othering” of the Nazi regime on account of its radical racism, amongst the military intelligentsia the reverse tendency prevailed. For analysts concerned to hone the “military effectiveness” of NATO’s armies in Cold War Europe, the Germans were not just different. They were better. As Colonel Trevor N. Dupuy the leader of the new breed of quantitative battlefield analysts wrote in Predictions and War, New York, 1978: “On a man for man basis, the German ground soldier consistently inflicted casualties at about a 50% higher rate than they incurred from the opposing British and American troops UNDER ALL CIRCUMSTANCES.”6

Inverting the terms of the earlier debate about generalship, Max Hastings in Overlord, published in 1983, arrived at the cruel conclusion that it was not Montgomery who had failed his troops, but the other way around. As Hastings put it: “Montgomery’s massive conceit masked the extent to which his own generalship in Normandy fell victim to the inability of his army to match the performance of their opponents on the battlefield.” “There was nothing cowardly about the performance of the British army in Normandy”, Hastings hastened to add. But it was simply too much to expect a “citizen army in the fifth year of war, with the certainty of victory in the distance” to match the skill and ferocity of the Wehrmacht at bay. It is worth remembering that Hastings concluded his D-Day book, shortly after participating as an embedded reporter in the Falklands campaign, in which the highly professional British army humbled a much larger force of Argentinian conscripts. And he did not hesitate to draw conclusions for NATO in the 1980s from D-Day. Given the overwhelming conventional superiority of the Warsaw Pact, the “armies of democracy” needed to examine their own history critically: “If a Soviet invasion force swept across Europe from the east, it would be unhelpful if contemporary British or American soldiers were trained and conditioned to believe that the level of endurance and sacrifice displayed by the Allies in Normandy would suffice to defeat the invaders. For an example to follow in the event of a future European battle, it will be necessary to look to the German army; and to the extraordinary defence that its men conducted in Europe in the face of all the odds against them, and in spite of their own demented Führer.”8

In the 1980s, whilst for liberal intellectuals Holocaust consciousness served to buttress a complacent identification with the “values of the West”, the military intelligentsia were both far less sanguine about a dawning end of history, in which their role seemed far less self-evident, and far more “open-minded” in the use they were willing to make of the history of Nazi Germany. The most striking instance of this kind of militarist cultural critic was the Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld, who was not then the marginal figure that he was to become in the 2000s. His Fighting Power published in 1982 was at the center of the “military effectiveness” debates that were convulsing the American army in the wake of Vietnam. Why, van Creveld asked, had the German army not only fought better but held together in the face of overwhelming odds, why did it not “run”, why did it not “disintegrate” and why did it not “frag its officers.” Creveld’s answer was simple. The Germans fought well because they were members of a “well integrated well led team whose structure administration and functioning were perceived to be …. Equitable and just.” Their leaders were first rate and despite the totalitarian regime they served were empowered to employ their freedom and initiative wherever possible. By contrast, the social segregation in America’s army was extreme. “American democracy” Creveld opined “fought world war II primarily at the expense of the tired, the poor the huddled masses” “between America’s second rate junior officers “ and their German opposite numbers there simply is no comparison possible.” On the battlefield Nazi Volksgemeinschaft trumped Western class society. If despite these devastating deficiencies, the allies had nevertheless prevailed, the reason was not military but economic. Overwhelming material superiority decided the outcome. Brute Force was the telling title chosen by John Ellis for his powerful summation of “Allied Strategy and Tactics in the Second World War”.

This was a conclusion backed up by economic histories that began to be published at the time, for instance my Wages of Destruction and David Edgerton’s The British War Machine. The Allies waged a “rich man’s war” against a vastly inferior enemy. In the mayhem of the Falaise Gap, as the German army in Normandy collapsed, the Allies were shocked to find the grisly carcasses of thousands of dead horses mingled with abandoned armor and burned-out soft-skinned vehicles. What hope did the half-starved slave economy of Nazi-occupied Europe have of competing with the Allies’ oil-fuelled, globe-spanning war machine?

But it was not just the battlefield contest and its material background that were being reexamined from the 1970s onwards. So too was the methodology of military history and its mode of story telling. The juxtaposition of Carlo D’Este’s Decision in Normandy and Max Hasting’s Overlord published within months of each in 1983-1984 marks a moment of transition. D’Este offers a classic view from the top, focusing on the high command. Hastings assembles his history from the bottom up. His was, one is tempted to say, a social history of combat – organized around the category of experience, intimate, personal and graphically violent. In this respect Hastings followed in the deep footprints left by John Keegan’s pathbreaking, The Face of Battle (1976).

The image that Hastings painted was savage. The struggle waged in Normandy was no “clean war”. Appalling death and destruction scarred the battlefield. Casualty rates on the cutting edge of the Allied side ran well above 100 percent by the end of 1944. Hastings did not deny the atrocities committed by the German soldiers he recommended as an example for NATO. But he leveled the score by pointing out how frequently the Allies armies shot both prisoners and Germans trying to surrender. Savagery begat savagery in a loop that was more anthropological than political. And if violence was no longer taboo, then this went for the civilians as much as the soldiers. Since the early 2000s, a powerful new strand of literature has sought to address the enormous collateral damaged produced in the course of the landings and the way in which “liberated” France struggled to come to terms with this harrowing experience. Allied ground and naval artillery, but above all air power wreaked havoc in French cities and claimed tens of thousands of lives. Tellingly, this grim history was uncovered in the context of a wider and highly critical investigation of the Allied strategic air war directed by Richard Overy – see Richard Overy, The Bombing War: Europe 1939-1945 (London, 2013) and C. Baldoli and A. Knapp, Forgotten Blitzes: France and Italy under Allied Air Attack, 1940-1945 (London, 2012).

This historical enquiry was flanked by a more wide-ranging inter-disciplinary enquiry into liberal societies and war. In the aftermath of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars and the legal questions posed by a new era of long-range and remote killing, the question hung in the air. Was the use of force by the Allied forces in Normandy proportionate? Did it constitute a crime against the French civilian population? The ambiguity of liberation is brought home most recently by Mary Louise Roberts, who in What Soldiers Do (2014) described how the bodies of French women were made the eroticized booty of the soldiers of the “Great Crusade”.

In World War II, there was nothing like the conscientious objection movement on the Allied side that there had been in World War I. But given the scale of the violence that they were dealing out in the final stages of the war, it is not surprising that at least some people spoke out in protest. Opposition to the destruction being wrought in France ranged from outraged ethical criticism in the House of Lords, to the shock of a corporal in the 4th Dorsets cited by Hastings who later recalled the incongruity of bursting into a French home during house to house fighting: ‘There we were, wrecking this house, and I suddenly thought – “How would I feel if this was mine?”

In 1940 the British Expeditionary Force in France had been under strict instructions to avoid all damage to French property, including a prohibition on knocking loopholes in brick walls so as to create firing positions. In the D-Day campaign Allied forces reduced entire cities to rubble. But horrific as the bombardments clearly were, research on the British side does not suggest that revulsion was the general response. The war had to be won and if firepower kept Allied soldiers out of harms way, so be it. Few allied soldiers apologize for the material preponderance they commanded. Many of them clearly relished the spectacle. For the commanders the war might be an end in itself, an opportunity to write their names into the annals of military history. For the vast majority of their troops it was a job to be accomplished. The Germans were to be defeated with whatever means and manpower was available to crush them. In so doing, the Allies may not have matched the military skill of the Wehrmacht. But it was not merely brute force. The Allied war effort had its own logic – political, strategic, operational, tactical and technical. Rescuing this logic from the damning but tightly circumscribed judgments of the “military effectiveness” literature, has been the purpose of two decades of revisionist scholarship.

This revisionism has been directed in three directions. Setting aside the question of whether Montgomery’s D-Day plan was executed as he claimed, the new work has sought to articulate the relationship that clearly did exist between grand strategy, the D-Day operation and the tactics of Allied war fighting. Especially crucial in this regard have been a variety of technical studies on firepower and how it was brought to bear. And embracing both of these more specialized currents have been more expansive social histories that help us to understand the men who fought in the Allied armies and the social relations produced and reproduced in the war.

The revisionism has been general, but it has been most comprehensive with regard to the forces of the British empire, which thanks to their “failure” outside Caen and the malaise of postwar Britain have been the subject to the most withering criticism. Both David French Raising Churchill’s Army: The British Army and the War against Germany 1919-1945 (Oxford, 2001) and Alan Allport’s Browned-off and Bloody Minded: The British Soldier Goes to War (1939-1945) (Yale, 2015) mount powerful critiques of the clichés that continue to dominate accounts of the British army. Both seek to overturn the stereotypes of the British officer corps as Colonel Blimps that dominated both contemporary and postwar commentary. David French does so by focusing on the professional logic that made the interwar British army into an organization dedicated to sustained, if rather quixotic, modernization. If it was held back from full-scale military revolution it was due to budgetary constraints and the need to accommodate the demands of imperial policing. French does not deny the influence of Britain’s all-pervasive class structure, but insists that what determined the history of the Army were not general social attitudes, but the evolution of a peculiarly rigid and unbending vision of military professionalism. It is telling, he points out, that officers at Sandhurst spent the vast majority of their time being drilled as exemplary private soldiers, rather than learning tactics or new technology. Building on French’s insights into the inner workings of the officer corps, Allport tackles the class issue head on. Whilst military professionalism might dominate the thinking of the officer corps, once the Army began to expand dramatically from 1939 onwards and millions of men were pent up for years in base camps, class hierarchy simply could not be ignored. Whilst enormous economic disadvantage and inequality persisted, what the Army had to contend with was a society in flux. 15 As the 1937 “Survey of the Social Structure of England and Wales” reported: ‘All members of the community are obviously coming to resemble one another.’ Against this backdrop of increasing egalitarianism in terms of consumer tastes and lifestyles, wartime military life was a shock, “a reminder that this superficial democratization in tastes had done little to alter the fundamental hierarchies that divided up British society. Class structure ‘was duplicated so grotesquely in the services’, thought Anthony Burgess, that ordinary soldiers who had hitherto paid it little attention could not help but be awakened to its existence. Richard Hoggart too believed that the Forces ‘reinforced, repeated, set in their own amber, the class-determined definition of British life’ in a way that was too obvious to ignore and too obnoxious to defend.” Talk of serious unrest, of course, was exaggerated. In the British army in World War 2 and on the home front there was nothing to compare with the radicalization of 1916-1921. If the British army was largely made up of working-class men in uniform, it was a class that in the 1920s had suffered a historic defeat and was recovering from mass unemployment. Organized labour was firmly in control of the Labour Party and integrated into Churchill’s government as the junior coalition partner. What was on display on the beaches of Normandy in 1944 was not subversive radicalism, but what Anthony Beevor has recently dubbed a “trade union mentality”, which upheld a bargained relationship with authority, military discipline and the ultimate demands of the war. If there was one thing that all ranks in the British army were united around it was the determination to avoid a repeat of the wholesale slaughter of the Somme or Passchendaele. As French puts it: “After 1918 senior British officers knew that never again would society allow them to expend their soldiers’ lives in the same profligate way that they had on the Western Front.” And, as Allport showed, this extended all the way down the ranks. Soldiers appreciated an energetic young officer, but not one whose courage and enthusiasm put the lives of his men at risk. The question was not one of out-right disobedience or refusal to follow orders, but a sense of proportion and reasonableness. Both soldiers and officers reacted badly to orders that were in the language of the time, ‘not on’. This, as Hastings put it, was “a fragment of British army shorthand which carried especial weight when used at any level in the ordering of war. Before every attack, most battalion commanders made a private decision about whether its objectives were ‘on’, and thereby decided whether its purpose justified an all-out effort, regardless of casualties, or merely sufficient movement to conform and to satisfy the higher formation. … following bloody losses and failures, many battalion commanders determined privately that they would husband the lives of their men … making personal judgements about an operation’s value. …. as the infantry casualty lists rose, it became a more and more serious problem for the army commanders to persuade their battalions that … tomorrow’s map reference, deserved of their utmost. …. The problem of ‘non-trying’ units was to become a thorn in the side of every division and corps commander, distinct from the normal demands of morale and leadership….”.

Not that there was anyone in senior leadership who did not understand the need to husband manpower. Despite their overwhelming material advantage, none of the Allied armies was oversupplied with infantry draftees. The British army at D-Day started at 2.75 million men and dwindled from there. In May 1944 the American army disposed of only 89 combat divisions in all theaters, of which only 60 were available for deployment in Europe. Of these 16 were armored. This compared to c. 100 divisions in the Japanese army, c. 240 in the Wehrmacht and over 300 in the Red Army. Conscious of their modest manpower reserves and the need to limit casualties, the Allied armies sought to compensate with material and machinery. But what kind of machines did their armies need?

Both the British army, with Imperial “small wars” in mind, and the US, with its legacy of the frontier wars and a strong cavalry tradition, gave priority to mobility over striking power. This preference did not stand the test of combat in World War II. From North Africa onwards, it was clear that motorization and mechanization were not enough. On the battlefield the ability to move without massive casualties depended on the suppression of the enemy’s fire, which depended on establishing fire superiority. Ideally, this would have required heavier and better-armed tanks and more and better infantry small arms. But given development time lags, in 1944 the Allied armies had to make do with the botched results of several waves of misdirected modernization, which yielded both inferior infantry weapons and tanks. The German army, by contrast, was benefiting in 1944 from a burst of new weapons development that had been energized by the Wehrmacht’s shocking experience on the Eastern Front in 1941. In tanks, anti tank weapons, anti-aircraft and small arms this gave them a distinct qualitative edge. As a result, the encounter in Normandy was strikingly asymmetric. Whilst at the macroscopic level, the Allied armies enjoyed overwhelmingly material superiority with regard to air and naval power, petrol, ammunition and limitless supplies of new weapons – in any given tactical encounter they were more often than not at a disadvantage. In tank battles the Allies could compensate through sheer weight of numbers. But in infantry firefights it was the Allies, not the Germans who tended to be out-gunned. Crucially, the Germans equipped their infantry companies with as many as 15 light machine guns (as opposed to only 2 in the US army), allowing them to concentrate huge weights of small-arms fire. As a result of this mismatch, despite the desire to husband manpower and to avoid any repetition of World War I, the casualty rate at the sharp end of the Allied armies was terrible.

These then were the parameters of allied war-fighting. They were sustained and haunted by the confident expectation of ultimate victory that many of those in the fighting line would not live to see. They faced a fearsome, skillful and well-equipped German army, with equipment that was mediocre and manpower that was limited. The British army was willing to fight and to sacrifice, but was skeptical towards the traditional hierarchies and the language of heroism. Allied soldiers were unashamedly interested in surviving to enjoy the victory that was rightfully theirs. It was out of this set of parameters that Stephen Ashley Hart in Montgomery and Colossal Cracks (Praeger, 2000) distills an ideal type of Montgomery’s mode of war-fighting. Each part corresponds to one side of the Clausewitzian trinity. Montgomery’s bold, even triumphalist talk helped to sustain the sense of the historic inevitability of Allied victory. At the same the operational conduct of the campaign was cautious, setting modest and attainable operational demands that helped to maintain morale and avoid a devastating setback that might have fractured the fragile belief in battlefield superiority. To square the circle the Allies deployed absolutely overwhelming long-range fire power. “Colossal cracks” was the phrase that Montgomery liked to use to describe his gigantic artillery barrages.

It was not gratuitous desire for destruction or blunt tactical incompetence, but the very obvious technical inferiority of the Allied armies and the urgent need to minimize casualties that caused the British, American and Canadian soldiers to rely to such an unprecedented extent on long-range fire support: artillery, naval guns and every kind of airpower. As the revisionist literature stresses, it is precisely in the orchestration of long-range fire support that Allied war-fighting was at its most skillful and innovative. Never before had naval artillery been used to such devastating effect in a land campaign. The awesome blunt force of strategic bombers was turned loose on the battlefield. The spectacle was overwhelming, the destruction was awful and the tactical benefits uncertain, but never before had a weapons system of such complexity – fleets of up to a 1000 aircraft guided by invisible electronic rays – been deployed on a battlefield. At the same time, tactical airpower assumed an unprecedented significance, with squadrons of fighter-bombers loitering over the armored columns as they advanced, in constant radio contact, ready to reconnoiter and strike targets ahead at a moment’s notice. It was a distinctly futuristic vision of a new type of war. As General Pete Quesada, who headed IX Tactical Air Command commented triumphantly to his mother, “My fondness for Buck Rogers devices is beginning to pay off” – as cited in T.A. Hughes, Overlord, General Pete Quesada and the Triumph of Tactical Airpower (New York, 2010)

Even the artillery, the king of the battlefield since the dawn of the gunpowder age, was undergoing a dramatic and easily under-rated evolution. Orchestrated by an elaborate radio and field telephone system, linking forward and aerial observers to Fire Control Centers, British and American gunners were able, within minutes, to concentrate unprecedented weights of fire at key points on the battlefield. As powerful new histories of the Canadian sector to the West of Caen have shown – notably T. Copp, Fields of Fire. The Canadians in Normandy (Toronto, 2004) and M. Milner Stopping the Panzers (Kansas, 2014) – what gave the Canadians the ability to stop German armored counterattacks against the bridgehead was the speed with which they could bring down devastating artillery firepower on any visible concentration of German troops.

But if these are the elements of a far-reaching revisionist synthesis, the result is an increasingly evident tension between form and content. The new consensus on how the Allies fought the war is at odds with the narrative strategies used by historians since the 1980s. This tension is quite pronounced in the most ambitious of the new synthetic accounts of the D-Day campaign, Antony Beevor’s D-Day and Allport’s Browned Off. Both books are very much in the new mode of experiential military history, taking us close to the action and the hearts and minds of the men who fought. This focus on the reality of combat anchors the narrative in the frail bodies and tortured souls of the men at the sharp end. The lyricism of the literary testimony in Browned Off and the narration of battlefield horror in Beevor’s D-Day set a new standard of intensity. Since the taboos on talking about death in modern combat were broken, unshrinking realism has become its own formula. Beevor’s D-Day is a relentless parade of horrors – phosphorous burns, the incineration of tanks crews, decapitation, dismemberment, the smashing of bodies, faces, arms, feet and legs blown off, bowels eviscerated, wounded men burned alive in blazing fields and crushed by tank tracks. As Allport puts it in his remarkable conclusion: “The human body was a frail thing to expose to fire and steel, shrapnel and high explosive, flying concrete and glass. Soldiers were shot, punctured with shell fragments, lacerated by shards of debris. They had their backs broken, their hands and feet scythed off, their limbs pulverized, their eardrums permanently shattered by concussive explosions, their eyes burned out of their sockets.”

The men who experienced such violence most directly were in the infantry and armoured divisions. It is their memoirs and reminiscences that dominate Beevor and Allport’s narratives, as they do the entire historical literature. But this is not only unrepresentative of the Allied armies in which 45 percent of the manpower was in rear area functions, as against 14 % infantrymen, and 6 % tank crews.23 More importantly, it cannot capture precisely what the revisionist literature is at pains to stress, namely the central importance to Allied war-fighting of long-range firepower. It was not by accident that the gunners made up the largest single group in the British army (18 % of the force in Normandy) and that by the end of World War II the Royal Artillery outnumbered the manpower of the Royal Navy.

This bias towards the immediate experience of combat distorts Beevor’s account of military operations in D-Day throughout. The artillery and the bomber rarely appear in his narrative without doleful emphasis on their misdirection and the collateral damage they inflicted. Only in the final sections of the narrative does he begin to do justice to what was in fact a fully three-dimensional campaign. There is a grudging discussion of the role of airpower and artillery in the Cobra offensive and the repulse of the German counterattack at Mortain in August 1944. But airpower appears at this point in the narrative more as a deus ex machine than a concerted technological and tactical development. And even here, whereas Beevor extolls the resilience and bravery of the infantry of the 30th Division who suffered 300 casualties out of 700 men in holding Mortain in the face of German encirclement, he goes on to attribute the destruction of the town itself to a “fit of pique” on the part of a staff officer far behind the lines, reinstating every cliché of the Frontgemeinschaft and obscuring the fact that the heroic stand of the “lost battalion” was made possible only by long-range artillery fire support. As Robert Weiss makes clear in Fire Mission! The Siege of Mortain, Normandy August 1944 (Portland, 2002), by the second day of the Mortain battle, the infantrymen holding out on hill 314 had virtually no ammunition with which to return German fire directly. The radio with which to call up fire support was their only weapon.

In this clinging to a conventional personalized narrative of horror and heroism, now supplemented by the anguish of bombed out civilians, the protocols of a “humanistic”, bottom up history of modern war, and the emotions and ethical questions it summons up, clash with what the revisionist history has established as the basic mode of Allied war-fighting in Normandy, namely its reliance on long-range firepower and the complex, anonymous and mundane logistical apparatus that delivered it. The tension is summed up in one of Allport’s witnesses, who remarks that whilst the Allied artillery barrages were reassuring in their awesome firepower, it was troubling that such ‘dispassionate acts of mechanical precision employed in killing’ were set into motion by men who, moments after unleashing their murderous fire on the enemy infantry, would be calmly ‘lifting mugs of tea and lighting cigarettes’ in their dugouts miles behind the front.”25 As Hastings noted, the gap between individual and war machine was a problem haunting the Allied war effort: “The sheer enormity of the forces deployed in Normandy destroyed the sense of personality, the feeling of identity which had been so strong, for instance, in the Eighth Army in the desert. The campaign in north-west Europe was industrialized warfare on a vast scale. For that reason, veterans of earlier campaigns found this one less congenial – dirty and sordid in a fashion unknown in the desert. Many responded by focusing their own loyalties exclusively upon their own squad or company.”26 Characteristically, in the spirit of the 1980s military effectiveness argument, Hastings turns these observations about military alienation into an explanation for diminished fighting power. But is this not an evasion? Rather than flinching away from this disconcerting reality, rather than clinging to the visceral experience of the combatants who lived the war in the most unmediated way, should a history of modern war, and of Allied war-fighting in particular not take this mounting sense of dissociation as its central focus? What would a history of the Normandy campaign look like that took its own conclusions seriously and revolved around firepower rather than combat?

This is not a new question in the history of war in the twentieth-century. It was already posed with dramatic force by World War I. And the fighting around Caen did seem to reawaken for a month or two the nightmarish memories of Passchendaele. The force of the traumatic memory of World War I tempts one to describe the shock of combat in Normandy in those terms – as winding back of the historical clock. The fast-moving armored warfare of 1939-1941 had seemed to promise an escape from the horrors of trench warfare. In 1944 the armor-heavy landing forces of the Allies, were looking forward to waging their own Blitzkrieg across France. Normandy delivered something else. This was disorientating to both sides. As one German commander said about his colleagues in the Panzer divisions: The moment for free-wheeling tank-on-tank clashes had come and gone. “They now had to wake up from a beautiful dream!” The question is whether to think of this shock as a throwback to Passchendaele, or as pointing to the future. Rommel, who was not only amongst the first practitioners of Blitzkrieg but also one of the most innovative infantry commanders of World War I, warned his colleagues when he arrived on the Atlantic Wall that their encounter with the Allies would be different. What they would face would not be 1917, or 1940, or even the Eastern front. The volume, coordination and three-dimensional reach of Allied firepower – both artillery and air power – changed everything. Perhaps rather than looking backwards to the trenches of 1916 or 1917, it is precisely to the strategic air war that we should look for models of how to write the history of the new kind of combat seen after D-Day.

In the case of strategic air war, old models of combat clearly do not apply. To capture the strategic bombing campaign, books such as Alexander Kluge’s Der Luftangriff auf Halberstadt am 8. April 1945 (Frankfurt, 1977) and M. Middlebrook, The Battle of Hamburg: The Firestorm Raid (London, 1980) and J. Friedrich’s sensationalist and derivative Der Brand (Munich, 2002), have experimented with dissociated, multi-perspectival narratives, in which it is precisely the abstraction of large-scale organization, the labor of war and its complex mechanisms for delivering firepower, that are the focus as much as the visceral reality of combat.

An obvious starting point would be to trace the networks of communication and observation that animated the Allied firepower system and brought the mortars, guns and fighter bombers into play. Balkoski in his unit history of the 29th division, Beyond the Beachhead (Mechanicsburg, 1989), one of the two divisions that had the misfortune to be first ashore at OMAHA beach, gives a fascinating account of the command chain for artillery. 29 A fire request might start with one of the SCR-536 “handy-talkies” – one per platoon – or with a Forward Observer team equipped with a SCR-300 FM radio with a speaking range of 5 miles.

How might the battle look if its history were viewed from the vantage point of one of the ubiquitous Piper Cub spotter planes (or its British equivalent the Auster), which hovered ominously over the German ranks – an anticipation of present-day drone warfare? One might stark, for instance, with the account of aerial observation in S. Bidwell, Gunners at War. A Tactical Study of the Royal Artillery in the Twentieth Century (London, 1970),

What might we find if we dusted off the massive official histories of Army Signals during World War II, notably George Raynor Thompson and Dixie R. Harris, The Signals Corps (Washington DC, 1966, )which recount the remarkable wire networks and wireless relay systems that the Allies spanned across France, including a radio relay atop the Eiffel tower? How would our narrative of the war read, if we centered it in one of the Battalion Fire Direction Centers, an assembly of “ultra-modern communications equipment” crammed into a mobile shed little bigger than a closet, a cross between a “telephone exchange and a draftsman’s workroom”, laced with wires running to a “buzzing, flashing switchboard”, filled with bulky high-powered radio sets and officers hunched over maps “using compasses and protractors to plot artillery fire” in real time. This is a war of what Rayner Banham would later call gizmos or gadgets.

By August 1944 Quesada’s centralized MEW/SCR-584 radar center, connected to fighter-bomber groups by 10,000 miles of telephone wire was able to direct strike missions even in the worst weather. From such vantage points the war could be experienced at the same time as very close and disconcertingly remote. Spotter planes flew no more than a few hundred meters above the ground and the barrages they called down often passed so close that they “jolted” the wings of the aircraft. At the same time, one pilot noted, “it was a very disembodied business,’ “One day he was puzzled by piles of logs lying beside a road, until he saw that they were dead Germans.”32 It was not until he did a tour of duty as a forward air observer calling in strikes from inside a tank, remarked one Thunderbolt pilot that he gained any idea of “what it’s like down there”.33 A similar disjuncture marks the remarkable memoir of Lieutenant Robert Weiss, who commanded the forward observer group for 230rd Field Artillery Battalion and orchestrated the artillery fire that saved the American position on Hill 314 during the Mortain counterattack. During the battle between 7 and 12 August in a staccato series of radio messages clipped by fading battery power he called down no less than 193 fire missions from battalion and division level artillery. He had no other communication with higher echelon command. And, but for one brief breakthrough by a lone German tank, he never saw the enemy except at long range through binoculars. Positioned as he was, on a high vantage point, the battle was, as one colleague remarked “an artilleryman’s dream come true”. But what, Weiss asked, does an artilleryman dream of? “Are his conceptions those of glory and victory … ? Does he dream of shooting soldiers and tanks as if they were on a make-believe battlefield? Or … does he hear the scream and whine of shells, see men huddled against the earth shaking with fear?”34 Even a soldier as close to one of the most intense battles of the Normandy campaign as Weiss, never overcame the sense of dissociation. And what of the gunners and mortar-men themselves? As one remarked to Max Hastings they felt themselves and their firepower to be a fungible resource: “We would suddenly find ourselves put with a different army [said Ratliff of his 155 mm battery], and we would more likely hear about it on the grapevine than from orders. Much of our firing was blind or at night, and we often wondered what we were shooting at. Nobody would say down the telephone: ‘I can see this village and people running out.’ We would just hear ‘50 short’ or ‘50 over’ called to the Fire Control Centre.”35

Devastating as the artillery firepower of the Allies was, what haunted the Germans was airpower. This is clear from accounts such as Ian Gooderson, Air Power at the Battlefront. Allied Close Air Support in Europe 1943- 1945 (NY, 1998) and Richard P. Hallison, D-Day 1944. Air Power Over the Normandy Beaches and Beyond (1994)

It was, commented Admiral Ruge Rommel’s naval advisor, as if the Allies could open a new, vertical flank on any German position.36 Alternatively, as Patton would demonstrate, tactical airpower could also be used in the manner of a cavalry screen, to close the exposed flanks of his army as it charged up the Loire valley. Yet, to a remarkable extent even the recent histories of the Allied campaign replicate the famously fraught lines between army and air force. Atkison and Allport write histories of the American and British armies respectively. Beevor and Hastings purport to provide general histories of the campaign, but actually repeat the conventional narrative of land warfare. A history of the battle in three dimensions would not doubt feature moments of slaughter. Beevor quotes the “pitiless” testimony of an Australian Typhoon pilot who recalled making “cannon attacks into the massed crowds” of Wehrmacht soldiers trying to escape the Falaise pocket. “We would commence firing, and then slowly pull the line of cannon fire through the crowd and then pull up and go around again and again until the ammunition ran out. After each run, which resulted in a large vacant path of chopped up soldiers, the space would be almost immediately filled with other escapees.” But the recent literature on tactical airpower shows how untypical such situations of one-sided massacre actually were. In general, low-level ground attack mission were amongst the most dangerous assignments in the war. Though the Luftwaffe had been swept from the sky, the Germans had pioneered a new generation of small caliber automatic anti-aircraft canon, which was lethal at altitudes anywhere below 1000 meters. Altogether in the order of 20,000 flak batteries were deployed in Normandy. Beyond a17 sorties, a Typhoon pilot flying low-level rocket missions was considered to be living on borrowed time.39 Remote killing and visceral fear went hand in hand. Once hit, a Typhoon pilot, if he was lucky enough to regain control, had seconds to climb to altitude before attempting to bail out. If captured pilots could expect no quarter. Aware of the hatred they aroused, Typhoon pilots took to wearing army uniforms to avoid identification.

Behind the pilots and the gunners and the radio men and the spotters was a giant force, literally half the army, responsible for sustaining this modern, “rich man’s” war. In the American way of war, wrote one official Army historian, “it was hard to say which was more important – the gun that fired the ammunition at the enemy or the truck that brought the ammunition to the gun position.” Airmen were no good without air bases. As the front moved forward the Engineer Command of IX TAC built sixty new air strips across France in August and September alone. Each fighter group supporting 90 planes involved a ground staff of 1000 men and a wagon train of ground equipment.40 Never before had armies waged war with the material and logistical intensity that the Allies did in 1944. Never before had the labour of war come so close to replicating that of an entire modern society on the move. If this was made the center of our attention, not as a object of critique and unfavorable comparison to more frugal, more “military” armies, but as definitional of a new mode of warfighting, the D-Day campaign could be understood not as a throw back to Passchendaele, or as a pale imitation of true Blitzkrieg, but as something more radical, as a step beyond land warfare as it had been hitherto conducted, towards a more all-encompassing orchestration of destructive force.

In 1944 German propaganda threatened the Allied soldiers that they would soon find themselves on the wrong side of the channel, cut off from their home base whilst “robot planes scatter over London and Southern England explosives, the power and incendiary efficiency of which are without precedent.”41 It was a vain threat. Germany’s V1 and V2 rockets may have pointed the road ahead. But their warheads carried only one ton of explosives each. In a major artillery concentration the Allies could deliver several thousand tons of shells either in a rolling bombardment over a matter of hours, or as a moving barrage ahead of the infantry. In a strategic bombing attack they could deliver more than 3000 tons of high explosives in a matter of minutes. And the scale of Allied firepower deployment did not peak in Normandy. It rose to a crescendo in the final offensives into Germany in 1945 and it did not stop there. If we make firepower not combat into the organizing thread of our history of Allied war-making then the obvious terminus is 6 August 1945, three months after Germany’s surrender, 13 months after D-Day, when a B29 dropped a single nuclear device over the city of Hiroshima. Exploding 580 meters above the city, the first atomic bomb delivered, in a single devastating flash an explosive force of 16 kilotons, roughly three times the largest bombardment seen in Normandy.

Drawing a line forward from the firepower deployed at D-Day to the nuclear age may seem forced. But whether spoken out loud or not, it is one of the questions that hangs over the debate about the performance of the Allied armies in Normandy.

What drove the preoccupation with the relative “military effectiveness’ of Allied and German forces amongst analysts in the 1980s was precisely the search for a conventional alternative to Mutually Assured Destruction. Writers like Dupuy, Hastings and van Creveld argued that if NATO’s Armies was to withstand the Warsaw Pact without massive use of nuclear weapons, they would have to repudiate their own military history and take lessons from the Wehrmacht. The Allied commanders after 1945 agreed, but they drew the opposite conclusion. Much as we tend to separate World War 2, as the last great conventional war, from the nuclear age, the line is in fact blurred. After Hiroshima, it was the victors of Normandy – Eisenhower, Montgomery, Bradley, Ridgeway – who remade themselves as the first generation of nuclear warriors and introduced “nuclear mindedness” to NATO’s ground forces.

As early as 1947 Montgomery conducted a war game, in which the invasion of Italy in 1943 was rerun, but this time with nuclear weapons. He was delighted with the results. After the formation of NATO, it was Montgomery as Deputy SACEUR to Eisenhower who would place the emphasis of NATO’s war-planning on confronting the Warsaw Pact forces in the North German plain. Already in the breakout from Normandy and the ill-fated Arnhem operation, Montgomery had had this arena in mind. None of the American or British military leaders were opposed to rearming West Germany or improving “military effectiveness”. As Dieter Krueger, David T. Zabecki and Jan Hoffenaar show in the studies collected in Blueprints for Battle: Planning for War in Central Europe, 1948-1968 (University of Kentucky, 2012) in America’s 7th Army, reactivated in 1951 in Southern Germany, the influence of the Wehrmacht example of “mobile defense” ran deep. But NATO’s commanders knew the battlefield odds were stacked against them. The breakneck disarmament after 1945 confirmed what they already knew about the limited willingness of democracies to put large numbers of soldiers in the frontline. The answer, as at D-Day was firepower, air power now supplemented by the nuclear weapons. It was under Eisenhower’s presidency in 1953 that the nuclear “New Look” strategy was first adopted. The first artillery regiment equipped with M65 280 mm atomic cannon was deployed to Kaiserslauten in 1954, smaller 155 mm nuclear shells soon followed. Meanwhile, licensed by MC-48, Montgomery’s staff at SACEUR were rapidly incorporating tactical nuclear firepower into their vision of modern war. In 1954 in the Battle Royal exercise, NATO simulated the effect of firing 10 nuclear shells on an advancing Soviet tank division, a supercharged version of the kind of tactics deployed by the Canadians in the summer of 1944. A year later, between 23 and 28 June 1955, under the code name Carte Blanche NATO played out large-scale air war over Europe. This involved thousands of aircraft and the simulated explosion of 355 nuclear weapons, 268 of them on German soil. The civilian casualty estimate was 5.2 million, 1.7 million of which would be immediately fatal. When pushed by journalists to confirm that NATO was serious about the use of such weapons of mass destruction. Montgomery affirmed that: “We at SHAPE are basing all our planning on using atomic or thermo nuclear weapons in our defence. . . . It is no longer ‘they may possibly be used,’ it is very definitely: they will be used if we are attacked.” If one bore in mind the massive weight of firepower with which he had decided the battle in Normandy, there was little reason to doubt him.

***

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

June 5, 2022

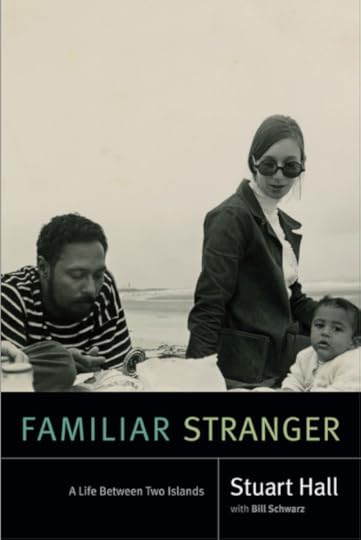

Chartbook #125: Familiar Stranger – Stuart Hall on diasporic thought

A few weeks ago, browsing the bookshop at the Barbican in London I chanced on Familiar Stranger – A Life Between Two Islands, the posthumous memoir by Stuart Hall edited by his friend and colleague Bill Schwarz.

Stuart Hall, born in Kingston Jamacia in 1932, was one of the founders of Universities and Left Review, which after merging with the New Reasoner, gave birth in 1960 to the New Left Review. Hall was one of the original contributors to the Birmingham school of cultural studies, co-author of one of most impressive pieces of analysis to come out of the 1970s, Policing the Crisis. In the 1980s, as a contributor to Marxism Today amongst other publications, Hall was one of the foremost analysts of Thatcherism and the crisis of the Labour Party. The subtlety of his diagnosis of the black diasporic condition, as exemplified by this memoir, is second to none. In our current age of polycrisis, Hall’s thought seems more relevant than ever. Policing the Crisis was constantly in the back of my mind in writing Shutdown.

But encountering Hall’s memoir in the last few weeks touched me in a different way.

In emotional and professional terms the last years, and the last few months in particular have been a maelstrom. Resuming travel to Europe after a long hiatus, in the wake of the consummation of Brexit, this internal turmoil was compounded by questions of identity and meaning that have been in abeyance for a while. For this, Hall’s text – a restless puzzling over the question of diasporic identity and thought – is not just clarifying, but consoling.

“What shall we call our “self”? Where does it begin? Where does it end?”

Hall’s epigraph taken from Henry James The Portrait of a Lady (1881) sets the tone for the text.

As Hall explains:

“These memories represent now, for me, not so much specific recollections as a sense of generalized absence – a loss, especially acute since I will probably never be well enough to see them again. They guarantee that I shall be Jamaican all my life, no matter where I am living. Though what that actually meant for men, in terms both of the practicalities of my life and of where my sense of belonging was to be located was much more problematic.” P. 10

Transitioning in 1951 from Jamaica, already on the off ramp to independence, to London and Oxford, never returning to Jamaica as anything more than an occasional visitor, Hall writes that he experienced his “life as sharply divided into two unequal but entangled, disproportionate halves. You could say I have lived … on the hinge … “. P. 11

A place on a hinge – whether in Jamaica in the transition to independence or, for instance, in 1989 in Europe, or China after Tiananmen – is not something you choose. You find yourself there.

“…. The transformations of self-identity are not just a personal matter. Historical shifts out there provide the social conditions of existence of personal and psychic change in here.” P. 16

A moment of transition can cast a long shadow. Hall was a small child at the time, but it was the anti-colonial upheaval and labour protest in Jamaica in 1938 that, in later life, he came to understand as overshadowing his youth. As he writes:

looking back, it feels as if 1938 has come to represent the opening skirmish in my personal war of position with my family, where I was uneasily torn between the enclave of the colonial coloured family and the tumultuous world of black Jamaica against which my familial ·enclave was designed to insulate me. These childhood experiences represented for me a slow disentangling of threads, a process of disenchantment and disaffiliation, pointing towards a radically different path ahead: an unpleasant experience, replete with gaps, contradictions, evasive silences, guilt and rage,· But also a journey with only one possible destination: out.

As Hall writes, in relation to these vast historical forces, “what mattered was how I positioned myself on the other side – or positioned myself to catch the other side.” 16

In this “war of position” (a Gramscian phrase), Hall takes inspiration from James Joyce, “who in his own situation, recommended ‘silence, exile and cunning’.”

Silence, exile and cunning are all forms of agency, a muted agency, but agency nevertheless. They are modes of positioning.

This relational idea of positioning runs through the text. As Hall writes:

“… identity is not a set of fixed attributes, the unchanging essence of the inner self, but a constantly shifting process of positioning. We tend to think of identity as taking us back to our roots, the part of us which remains essentially the same across time. In fact identity is always a never-completed process of becoming – a process of shifting identifications. rather than a singular, complete, finished state of being.” 16

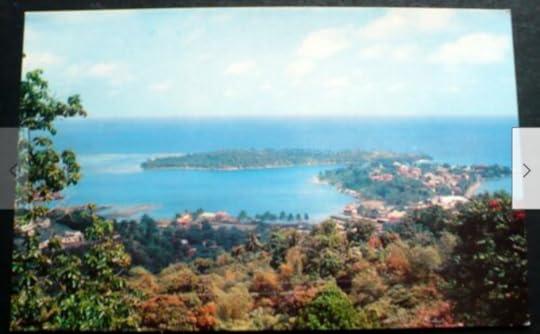

“From the very moment” Hall “watched the shoreline of Port Antonio in Jamaica receding into the distance”, he “was shadowed by the question of whether” he would return.

“I think I knew from the beginning that there could be no return, in the sense of regaining what had once been. That delusion never entered my soul, in part, I suspect, because I had no desire to relive my earlier life. But the complex amalgam of these questions about the self impressed itself sharply, both in my inner life and gradually, later, in my more academic and theoretical investigations. The line dividing the two was never great; … The core of the conceptual problem we are dealing with here is this. Are the positions we take regarding the general problem of return to one’s origin best understood as the product of our psychic formation and the way inner conflicts are ‘resolved’? Does psychic formation, in other words, ultimately determine where we stand in relation to such a discourse of restitution? Or, alternatively, are we positioned by discourse and power, as Foucault suggests? This is the theoretical dilemma I’m left with, turning on the explanatory weight we accord to the psychic, on the one hand, and the discursive, on the other: the ‘subjective’ and the ‘objective’. … It’s no doubt true that the dilemma of whether to return home distilled all these dilemmas in peculiarly concentrated form. But I’m making no larger claim than that. It wasn’t an experience that was exceptional.” p. 170

For Hall the experience of a black intellectual migrant in the dying days of the British Empire was illuminating of wider problems.

“The great value of diasporic thought, as I conceive it, is that far from abolishing everything that refuses to fit neatly into a narrative – the displacements – it places the dysfunctions at the forefront. In the imaginary it is possible to condense different persons in a single figure, to alter places, to substitute different time frames, or to slip ‘irrationally’ between them, as dreams frequently do. Montage is its lifeblood. We have to work with such ways of telling and speaking, with no attempt to iron out the disruptions. …. There are no alternative, direct routes. In historical reality, we cannot turn back the ever-onward flight path of time’s arrow. We can never go home again, and we need to fashion narrative forms able to catch the full complexities – the displacements, again – of this collective predicament.” 171

For Hall this goes to the heart of his appreciation of theory. For some exponents of the New Left, Marxism functioned as a safe harbor. For others the self-certainty of academic and theoretical rigor was an end in itself. Hall was satisfied by neither and ultimately resigned from the New Left Review editorial board.

‘I shifted from thinking of history as the search for the certainty of all-embracing totalities, to the necessity of recognizing the power of contingency in all historical processes and explanations. Or, in other words, of recognizing that the dynamics of displacement underwrite all social relations.” P. 76

If we cannot reverse time’s arrow, nor is Hall’s embrace of displacement a fuite en avant, a flight into the future. As much as we cannot go backwards, nor can we ever erase the past. As he approached death, Hall knew that he was forever Jamaican. As Hall remarks: “The dynamic of what Freud calls “afterwardness” “undoes any simple ‘before and after’ historical sequence.” P. 78

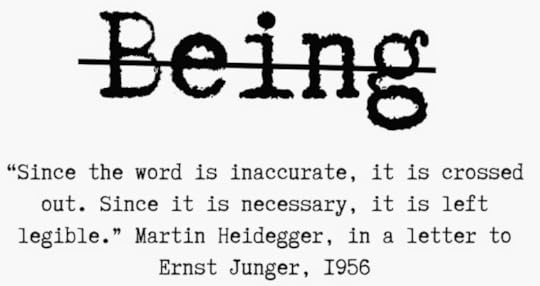

The “post” in postcolonial is

“not just a matter of the passage of time. It refers to the way one configuration of power, institutions and discourses, which once defined the social field, has been replaced by another. The old has indeed radically changed its form. However, the old has not been transcended. We continue to stand in its shadow. …. not two successive regimes but the simultaneous presence of a regime and its after-effects. …. Jacques Derrida points out that in his use of erasure … one can still read the metaphysical concept through which a cancelling line has been drawn … what options are there except to go on thinking with those old contaminated concepts in their deconstructed state? … there is no “beyond” …. We are what comes “after”, because the after-effects of what was in place “before” have not been superseded, overcome or (as Hegelians have it) sublated. The present still carries the specters of the past hiding inside it.” 24

Though Hall is speaking of the postcolonial condition, it struck me that one might think of both our relationship to neoliberalism, or the current condition of China in these terms, in terms of multiple erasures in which the cancelling and over-writing leaves the past all too visible. Indeed, one could extend the same vision of canceling and over-writing to our intimate lives, in which the past is irretrievably gone and yet inescapably and repeatedly, unexpectedly present.

Displacement poses questions of identification. It poses questions of history. It also poses questions of comprehension. As Hall spells out, the entire project of critical cultural studies was framed by his acute consciousness of displacement, in particular his sense that as a reader of the English literary cannon he was always at one remove, excluded from the habitus that informed the apparent meaning of texts for “native” English and American readers. The texts spoke to him with urgency, but in a different way to that in which they were read by British and American students.

What was in play in these jarring hermeneutic encounters was not a Freudian unconscious, but the discursive unconscious. What Hall’s displacement revealed was the thick web of mutually understood realities and relations – the phenomenological tradition would speak of lifeworlds, Michel Pecheux spoke of the pre-construit – that sustains reciprocity between speaker and hearer. This is what Barthes calls the connotative level.

To illustrate this point, Hall chooses a striking example taken from Barthes’ Mythologies.

An image shows two figures, a man and a woman, walking in the woods, engrossed in conversation.

This is spontaneously read by all knowledgeable viewers in terms of a richer set of metaphorical associations. It is obvious what one is witnessing.

“(T)wo lovers “wrapped up” in one another, oblivious to the rest of the world …”.

The warmth of their affection symbolized by their closeness and the harmony of their appearance.

Nothing further needs to be said. The image has the power that it does because, as Hall puts it, it serves as “the gateway through which ideology invades language. It’s a matter of both cognitive comprehension and what Barthes identified as the “pleasure of the text”.”

We relish the familiar image, which “organizes a discourse of romantic love and its recognizable scenarios. It arouses pleasure and desire.” That, in turn, both motivates and gives meaning to action. “It is at this structural level that language and ideology, or language and power, connect.”

That power, for Hall, is never merely discursive. It is real.

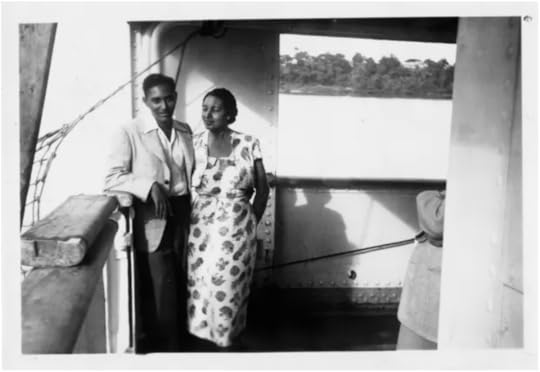

If his mother was the dominant force in Stuart Hall’s early life, weaving him into her desperate effort to maintain a late colonial world of social and racial hierarchy, imparting to him a profoundly fraught sense of identity, another woman, Catherine Hall who he met in 1962 on an Aldermarston protest march turned his life in another direction. As Hall wrote half a century later,

it’s not an exaggeration to say that among many other things – without I think quite knowing what she was doing -~ she rescued me, and saved my life.

Again and again throughout Stuart Hall’s text, Catherine Hall – herself a groundbreaking historian of Victorian Britain and the Caribbean – recurs as his interlocutor and as a fellow traveler across historic hinges and complex play of identifications.

In 1988 Stuart and Catherine Hall embarked on a family holiday in Jamaica. It was by Stuart Hall’s own admissions a difficult trip, on which he was dogged by his growing sense of alienation from the place where he was born. But Stuart Hall found redemption in the fact that for Catherine the same trip had a mirror image effect. She discovered that Jamaica was studded with villages whose names and Baptist churches mirrored those where she had herself grown up and whose history she knew intimately. These villages bearing English names were, they discovered, “free villages” that had been founded by Baptist missionaries in the hope of recruiting recently freed slaves.

The process of researching this historic displacement was for them, both individually and as a couple, generative and consoling.

Over a number of summers which followed we found ourselves off the beaten track, traversing the hills of rural Jamaica in search of the ‘free villages’ which had been established after Abolition … We navigated steep, potholed roads, one of us driving, the other trying to make sense of the maps which never seemed quite right. Many prolonged conversations with passers-by ensued, bringing into my line of vision a Jamaica which for an age I had barely encountered. … Moving from one back road to another, we were, step by step, tracking the processes of the entanglement of Britain and Jamaica through space and time. Our journeys helped us rediscover a vanished past; and they represented for us memory acts which resurrected, and worked with, forgotten histories. … It proved a moving, shared experience. It marks the moment when Catherine first immersed herself in the history of the Caribbean. But it was also important for me, bringing me face to face with a history that only had a distance hazy presence in my mind.” 80

Hall’s book is a precious reminder of the fact that much as we must all navigate the shifting terrain of identification – as Ijeoma Umebinyuo puts it in Disapora Blues, “too foreign for home, too foreign for here, never enough for both” – and as much as that terrain is poorly mapped and studded with potholes, as much as its pivots may be shaped by forces beyond our control, we have at our disposal both the creative energy of “positioning” and the strength of human bonds, of love, friendship and comradeship. As Hall’s title – Familiar Stranger – reminds us, displacement may be our inescapable condition, but solitude, anger, disorientation and lovelessness are not.

***

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

June 3, 2022

How Banning Ones & Tooze: Abortion Affects the Economic Lives of Women

With the U.S. Supreme Court apparently poised to overturn abortion rights, Adam and Cameron discuss the potential economic impact on women. Later on the show, they look at the economic indicators that characterized the 1970s—inflation, high energy prices, and slower growth—and discuss whether our national feeling of déjà vu is warranted.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

How Banning Abortion Affects the Economic Lives of Women

With the U.S. Supreme Court apparently poised to overturn abortion rights, Adam and Cameron discuss the potential economic impact on women. Later on the show, they look at the economic indicators that characterized the 1970s—inflation, high energy prices, and slower growth—and discuss whether our national feeling of déjà vu is warranted.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

May 28, 2022

Chartbook #124 The Currency of Politics

My brilliant friend Stefan Eich has a book out this week – The Currency of Politics – which I want everyone to read.

It offers an urgent and provocative analysis of political thinking about money from Aristotle to the present.

Stefan’s book is driven by questions that could hardly be more pressing: Why are we so afraid of the political malleability of money? What links political theories of money to moments of crisis? What makes money so tricky for democracies? And how can we democratize money?

These questions grew out of the politics of the 2008 banking crisis, which saw uninhibited central bank support for banks and financial markets, and out of the crisis of the Eurozone, where the ECB at times amplified pressure on the weaker and more indebted economies. His questions acquired further urgency with debates about MMT, “central banking for the people” and the question of how to finance the green energy transition. Stefan’s book is a milestone in the contemporary debate about money.

Eich laid out some of the key questions of his book in a wonderful twitter thread, which I am amplifying and embroidering on here.

The Currency of Politics is not just a history of political ideas about money. It offers an argument about how histories of crises and genealogies of thinking about money are interwoven and layered. It is to that extent also an intervention at the level of the philosophy of history, which is precisely what we need at the current moment.

As Eich puts it,

The Currency of Politics is about the layers of past monetary crises that continue to shape our idea of what money is and what it can do politically. Grappling with past crises helped previous theorists to escape the blindspots of their own time. We must do the same today.

As Eich shows, thinking about money as a political institution turns out to have a very long and distinguished history. Aristotle, for example, thought that coinage was a political form of money that communities gave themselves to strive toward justice. Very much like law!

As Eich shows in an important article, “The Greeks, it has sometimes been observed, did not have a word for money (von Reden 1995, 173).” But, “(r)ather than simply concluding that the Greeks did not have a specific word for money in our sense, I argue that the Greek conception of nomisma contained a political dimension that we have since lost, …”. It is not the Greeks, but we who have lost track of the true understanding of currency, as a foundational instrument of political community.

You might suspect that a book that stretches from Aristotle to the New International Economic Order is overreaching. But first Eich has the skillset to pull this off – the benefits of a German humanistic education! Like Keynes, and unlike most of the rest of us in the early 21st century, Eich can read Aristotle in the original Greek and comment authoritatively on the texts. He wears his scholarship so lightly that you barely notice the extraordinary things he is doing in this regard. Plus, as Eich shows, these deep intellectual historical connections are native to his material. Keynes thinks about money through Aristotle, whereas others, like Locke, are trying to drive Aristotle out.

As Eich points out this gives further meaning to Keynes’s comment that: “Money is, above all, a subtle device for linking the present to the future.” Money does that not only as a store of value, but as Eich shows as a thread of political conversation about currency and power.

As Eich shows, while money might seem far removed from politics (let alone democracy!), the modern monetary system actually depends crucially on the state and central banks. That does not mean all states can make money as they please. Instead, money is always suspended between trust & violence.

The Currency of Politics not only recovers this complex politics, but also explains how money disappeared from political thought. To do so, Eich grapples with the Lockean politics of monetary depoliticization and maps various responses to it by Fichte, Proudhon, Marx, Keynes, & others. One of the truly surprising chapters of the book traces the thinking about money that was triggered by the financial demands of the Napoleonic wars and their aftermath.

One of the key messages of the book is that though repressed politics will not stay down. The fault lines and tensions repeatedly make themselves felt.

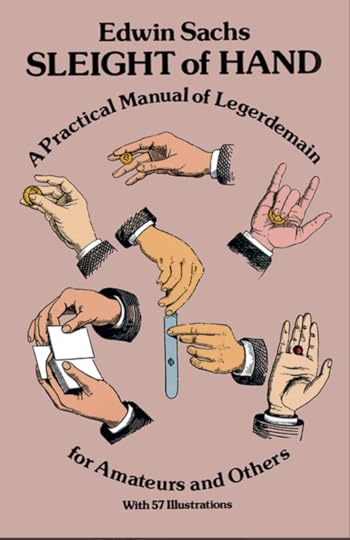

What follows from this, Eich asks? First, to present money as removed from politics is a magician’s sleight of hand. Even where it announces itself in an anti-politics, money is always already political. Instead, the depoliticization of money is better understood as a de-democratization.

If money is always already political the really key question is: What kind of politics should guide it? An oligarchic one? Or a democratic one? The suggestion of The Currency of Politics is that we should struggle to find ways to democratize our monetary systems.

As this image elegantly points out, all the heroic masculinist talk of Odyssean “self-binding” – a key image in central banker discourse about money – has, seen from the other side, a rather comical aspect.