Adam Tooze's Blog, page 22

April 1, 2022

Ones & Tooze: The French Election

The first round of the French presidential election is coming up on April 10. On the latest episode of Ones and Tooze, Adam and Cameron analyze what French President Emmanuel Macron’s views really are – and what it says about how France has changed.

Also, there’s an April Fools’ Day special: a segment on the economics of humor.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

March 30, 2022

Chartbook – Unhedged Exchange #2: The End Of Globalization As We Know It ?

The end of globalization as we know it?

Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock’s annual letter to shareholders stirred a flurry of debate last week about Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the future of globalization, supply-chains, inflation and its implications for investors.

Even in our moment of general pessimism about the world’s economic prospects, the boss of the largest asset manager in the world declaring that we are witnessing the end of globalization, is worthy of a headline.

In truth, like most people, the FT’s summary of Fink’s letter was all I read until I agreed with my friends Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu to make the future of globalization the topic of our second exchange of newsletters between Chartbook and Unhedged, the top financial markets newsletter at the FT.

Partnering with Unhedged is a real privilege.

Unhedged is the FT’s indispensable newsletter on the stories and ideas moving the markets. There is no better place to read the mind of the market.

Number 2 in our series offers readers of Chartbook a flavor of Robert and Ethan’s view of the headwinds facing globalization and the inflationary pressures ahead. See below:

To read my take on the same topic, readers of Chartbook can use this exclusive link to access Unhedged and all its excellent content.

It is, as I said last week, quite a thrill to be offering readers of Chartbook access to such premium content.

****

FROM HERE YOU ENTER THE WONDERFUL WORLD OF UNHEDGED

Last August, in the context of the “is inflation transitory” debate, Rob wrote that, “determining whether we are entering a new regime or returning to the old one is above my pay grade (it may be above everyone’s).” That remains Unhedged’s attitude. In September 1981, it was recently pointed out to us, few people would have recognized that we were at the high water mark for interest rates or appreciated how transformational figures such as Reagan, Thatcher, and Volcker would turn out to be. Grand theses about the direction of history sell books but age badly. Understanding the present is hard enough.

That said, there are a number of big changes taking place simultaneously, and the pace of many of those changes appears to have been accelerated by the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine. To an extent, this is obvious. Brexit, the election of Trump, the collapse of the TPP, rising tensions between China and the US, the 40-year high in inflation — all this is in front of our noses. Yet it is not obvious how much any of this will actually affect the way trade is done, markets operate, or capital is priced.

Unhedged’s guess is that there will be meaningful impacts. The world of the past several decades has gained from low rates, low inflation and growing global ties under liberal-democratic hegemony. We think that world is on its way out, and put the key changes into four categories: geopolitical shifts, the rise of populism, the energy transition, and demographics.

In geopolitics, borders are hardening. The US and China are pulling apart in fits and starts, especially where technology is concerned — with US restrictions on Huawei, and threats to revoke US listings of other Chinese tech firms matching China’s long standing limits on US tech giants operations in China.

The US business lobby that once pushed for cordial relations with China has almost entirely switched its stance toward confrontation, notes former IMF China head Eswar Prasad. First drawn in by the country’s vast and increasingly rich population, firms began to realise that access to Chinese markets came with strings attached. As accusations of intellectual property theft and forced technology transfer flew, corporate America soured on China.

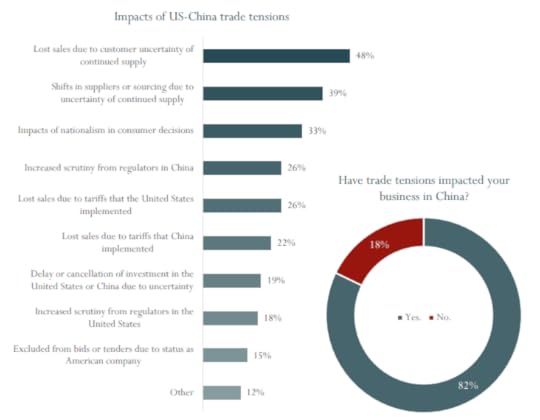

US foreign direct investment in China peaked in 2008 at $21bn and has since fallen to $9bn as of 2020. Chinese FDI flows to the US have also stalled. American businesses in China report lost sales, consumer boycotts and suffocating uncertainty — some of which is Washington’s doing. From the US-China Business Council’s 2021 member survey:

The Ukraine war and the sanctions regime that have followed will bring this balkanization into the financial realm, as the sanctioning of Russia’s central bank puts other regimes, including China’s, on notice. Martin Wolf recently wrote in the FT about what might result from the “weaponisation” of reserve currencies:

The overwhelming dominance of the US and its allies in global finance, a product of their aggregate economic size and open financial markets, gives their currencies a dominant position. Today, there is no credible alternative for most global monetary functions … In the long run, however, China might be able to create a walled garden for use of its currency by those closest to it … What might emerge are two monetary systems — a western and a Chinese one — operating in different ways and overlapping uncomfortably.

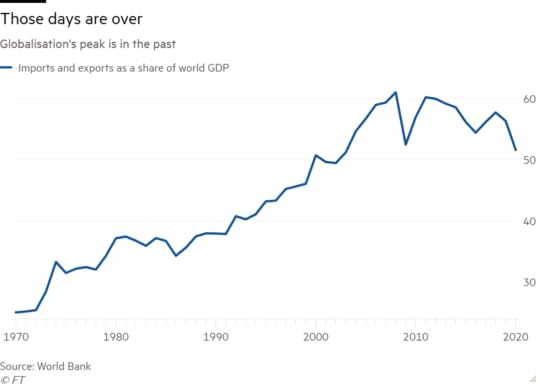

Even before the war, trade as a portion of global GDP had been flatlining. Recent flare-ups will reinforce a pattern that was already in place:

A more balkanized word, potentially split along a democratic/authoritarian axis, will not enjoy the deflationary benefits of a more unified one. Michael Hartnett of Bank of America — perhaps Wall Street’s leading adherent to regime change view — thinks that it also heralds a shift in stock market leadership:

With the balkanization of the global financial system and internet, you don’t get the benefits of scale [tech thrives on]. Then liquidity dries up [as policy tightens and rates rise]. What kills a bull market in tech is saturation and regulation … for national security reasons regulation tightens, at the same time as rates go up, so valuations should go down, and the stuff that is most egregiously overvalued is damaged the most. That happened already for unprofitable tech, and we have not seen it yet for profitable tech … tech is going to be the worst performing sector in the 2020s.

What will work? It comes back to selling hubris and buying humiliation, and we know where the humiliation is … banks, Europe, to an extent Japan

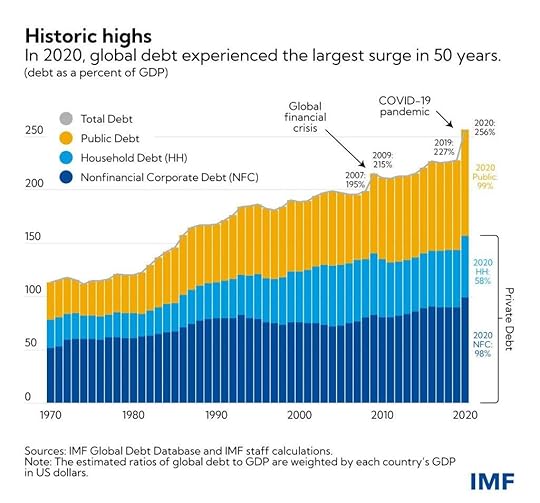

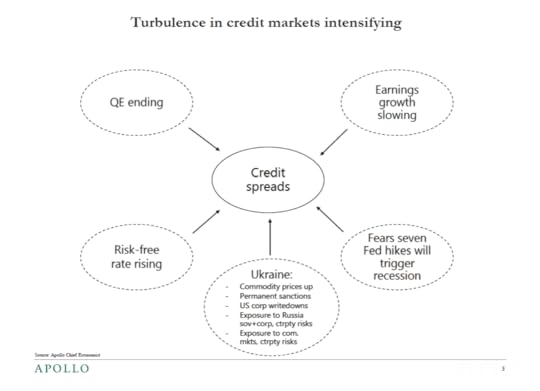

The post-pandemic manifestation of populism in politics is the addition of fiscal profligacy to the easy monetary policies that have characterised the decade since the financial crisis. Debt has spiked, and the policial temptation to deploy fiscal alongside monetary stimulus, after combination proved its power in the pandemic, will not prove easy to resist:

Historic public debt loads are not in themselves catastrophic. But combined with rising interest rates, debt-servicing burdens around the world will grow. Some governments will face a nasty choice — fiscal austerity or fully monetising the debt. The former will probably hurt growth; the latter could stoke inflation. Both are likely to be unpopular, and could further embolden populists playing to real anxieties. A financial crisis can’t be ruled out. IMF research finds that a swift uptick in household debt — precisely what Covid has brought — raises the probability of a future banking crisis by nearly 30 per cent (though the base risk is low).

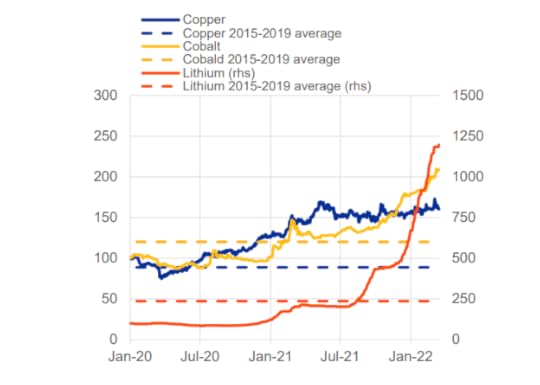

The energy transition is proving to be inflationary in two respects: investment in it is driving the price of hard commodities, while oil prices rise due to weak supply, driven by environmental policies, investor demands for high returns, and possibly the simple exhaustion of easily accessible reserves in the ground.

Isobel Schnabel of the ECB provided a good summary of the first inflationary effect in a speech about policy responses to greenflation:

Most green technologies require significant amounts of metals and minerals, such as copper, lithium and cobalt, especially during the transition period. Electric vehicles, for example, use over six times more minerals than their conventional counterparts. An offshore wind plant requires over seven times the amount of copper compared with a gas-fired plant. No matter which path to decarbonisation we will ultimately follow, green technologies are set to account for the lion’s share of the growth in demand for most metals and minerals in the foreseeable future. Yet, as demand rises, supply is constrained in the short and medium term. It typically takes five to 10 years to develop new mines… Export restrictions on Russian commodities may add to pressure on prices over the near term… the faster and more urgent the shift to a greener economy becomes, the more expensive it may get in the short run…

the significant need for private and public investment associated with the green transition itself is a reason to believe that real interest rates may rise from their subdued pre-pandemic levels.

She provides this eye-popping chart of percent changes of key “green” metal prices:

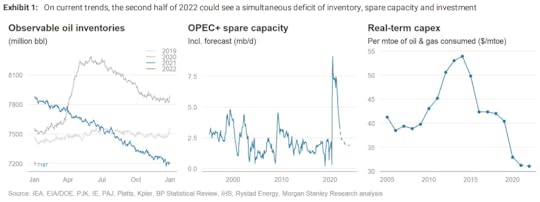

The likelihood of lasting upward pressure on oil prices is neatly described in this graph from Morgan Stanley, showing historically low inventories above ground, diminishing spare capacity among Opec countries, and low investment:

Many of these emerging trends point towards either higher interest rates or higher inflation, or both. Demographic changes, specifically the ageing of the global population, could well exacerbate those effects. This argument’s most well-known proponents are the economists Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan.

Unhedged has written about their views several times before. To sum up, for several decades moving production to low-wage countries has kept inflation low, but as the populations of those countries (particularly China) crest and begin to fall, wages there will rise at the same time as working age populations in rich countries fall. The increasing number of ageing dependents over workers is inflationary, and at the same time, as those dependents spend their savings, the global balance of savings and investment shifts back towards investment, driving the neutral interest rate up. A declining savings glut could also reduce inequality.

The Goodhart/Pradhan view is controversial, but there is no doubting the scale of the demographic shift that is taking place, with China at the forefront of it. It will matter, even if we are not sure how.

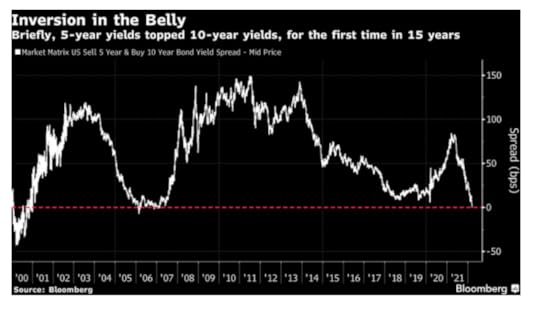

However wise or dumb our view of the future is, markets don’t share it, as Larry Summers pointed out to us. Current prices strongly imply the current spike in inflation and rates will subside before very long, and the old world of “secular stagnation” will re-assert itself. This is most easily visible in the Fed funds futures curve, which suggests rate increases will stop below 3 per cent some time next year, and that policy will weaken thereafter.

“The yield curve is telling us we will end this expansion with negative real rates … the market is telling us there still is secular stagnation on steroids” Summers says. “The demographic arguments, the green investment arguments, the new fiscal era arguments are all of the form ‘we will leave the world of secular stagnation and move to a world of permanent excess demand.’ The markets think they are wrong — if you look at multiples of real estate and PE multiples on stocks, the market does not foresee higher real rates.”

To repeat: Unhedged is acutely aware of the limits of big-trend prognostication. What we are arguing is that geopolitical tension, populist fiscal policy, the energy transition, and an ageing world are all important, all coming to a head simultaneously, and are all discontinuous with the low rate, low inflation, high integration, hegemonically liberal-democratic world we have enjoyed since 1980s. That era does seem to be dying, even if we can’t be sure yet what era is being born.

March 29, 2022

Chartbook #106: The new buttresses of the dollar system.

Triggered by the sanctions imposed on Russia’s central bank there is a lot of excited talk right now about the possibility of major holders of reserves diversifying away from the dollar.

I’ve been a skeptic. My sense is that the main lesson from Russia’s experience is that there is nowhere else to go. If you diversify out of dollars the only large-scale bolt hole is Euros and as far as major international crises are concerned the chances of the US and Europe not moving together is slight. And even if European governments did not take action, European financial institutions by now know the cost of finding themselves on the wrong side of the US authorities.

It is comforting to see my two esteemed fin-twitter colleagues @JosephPolitano and @RobinBrooksIIF in broad agreement.

Joseph Politano offers a typically well-argued and richly sourced take on why the dollars grip is likely to remain strong. The gist of his argument is that the dollar is simply too deeply dug into trade finance and global credit to be easily abandoned.

“”The US dollar will likely continue its 70 year reign as global reserve currency” doesn’t get clicks or sell papers, and so it doesn’t get written or shared. But that doesn’t make it any less true.” — @JosephPolitano illuminating as always https://t.co/oZXJ19pDxM

— Michael (@profplum99) March 26, 2022

Robin Brooks meanwhile tracks the daily capital flows with an eagle eye. And in this crisis he sees no erosion of the dollar’s strength. Rather the contrary.

There's chatter that Russia's invasion of Ukraine and ensuing US sanctions are causing a "stealth" erosion of US reserve currency status. This chatter is a long way from the reality in markets, where the Dollar is near record strength. There is no erosion of Dollar dominance… pic.twitter.com/cLuzDZXgJK

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) March 28, 2022

But then, in yesterday’s FT none other than Barry Eichengreen weighed in to the debate with a short peace announcing the “stealth erosion of dollar dominance”.

Eichengreen is by far the most influential international economic historian of his generation. Books like Golden Fetters anchor the entire literature on the interwar period.

So, when Barry Eichengreen sneezes we listen. When he announces the stealth erosion of the dollar’s standing you really pay attention.

In reading Eichengreen’s FT piece it is useful to add some background.

Eichengreen has long argued that it is simplistic to assume that the dollar’s current dominance is baked in for the foreseeable future. In a book published in 2017 with European Central Bank economists Arnaud Mehl and Livia Chițu, How Global Currencies Work: Past, Present, and Future (Princeton University Press), Eichengreen challenged the traditional “winner-take-all” view that there can only be one dominant reserve currency at a time. This assumption about reserve currencies, Eichengreen and his co-authors argued, was an artifact of the historical transition from the British pound dominated to the US dollar took over. It may now apply to the future.

Using evidence on central bank reserves from the 1910s to early 1970s, Eichengreen and his co-authors found that reserve currencies can and do coexist. In the interwar period, the British pound and the US dollar functioned side by side. Also before World War I, even though sterling was the most important currency, the French franc and German mark also functioned as major reserve assets.

“From this vantage point, it is the second half of the 20th century that is the anomaly, when an absence of alternatives allowed the dollar to come closer to monopolizing this international currency role,” Eichengreen and his co-authors argue.

On this basis they see no reason why the dollar might not find its relative share of reserve assets declining “sooner rather than later.” The dollar will be forced to share prominence with the yuan and the euro, in particular.

Quartz spoke to Eichengreen in London on what to expect if the dollar loses its hold over global financial markets.

Quartz: This book dismantles a long-standing theory about the global currency system. What was wrong with the traditional theory?

Eichengreen: The traditional view is that international currency status is a winner-take-all game, that there’s room on the global stage for only one true international currency. The argument was that network effects are so strong they create a natural monopoly because it pays to use the same currency in cross-border transactions that everybody else has used. The new view is that financial technology has moved on and network effects are no longer so strong. It’s easier to switch between currencies. It’s similar to how operating systems for personal electronics have transformed. Everyone doesn’t have to use Windows anymore.

I like the historicized approach to modeling the global currency system. It is easy to agree that the situation after 1945 was profoundly anomalous. Indeed, recognizing this point marks an important evolution in Eichengreen’s own thinking about financial hegemony.

Since the 1970s the dominance of the dollar has been maintained by scrambling improvisation. And in recent decades the euro has emerged as an alternative. I sketched a possible historical narrative along these lines in a piece for Foreign Policy back in January 2021.

But, as the current crisis illustrates, a diversification out of dollars into euros has turned out, as far as Russia is concerned, to be a difference that does not make a difference. Russia finds itself in what amounts to a euro-dollar trap – a triangle consisting of dollars, offshore euro-dollars and euros. It is this triangle of currencies that dominates the North Atlantic and East Asian financial hubs. It is subtended by dollar swap lines in unlimited amounts and is buttressed by a similar expansive monetary relationship with Japan.

Eichengreen’s most recent FT piece is based, as ever, on original historical research, this time in collaboration with Serkan Arslanalp and Chima Simpson-Bell. Their paper, “The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance: Active Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies” was published by the IMF.

As they summarize their results in their abstract:

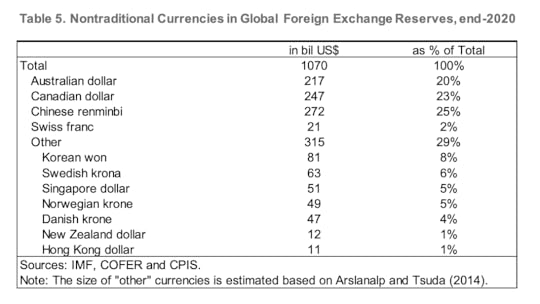

We document a decline in the dollar share of international reserves since the turn of the century. This decline reflects active portfolio diversification by central bank reserve managers; it is not a byproduct of changes in exchange rates and interest rates, of reserve accumulation by a small handful of central banks with large and distinctive balance sheets, or of changes in coverage of surveys of reserve composition. Strikingly, the decline in the dollar’s share has not been accompanied by an increase in the shares of the pound sterling, yen and euro, other long-standing reserve currencies and units that, along with the dollar, have historically comprised the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights. Rather, the shift out of dollars has been in two directions: a quarter into the Chinese renminbi,and three quarters into the currencies of smaller countries that have played a more limited role as reserve currencies. A characterization of the evolution of the international reserve system in the last 20 years is thus as gradual movement away from the dollar, a recent if still modest rise in the role of the renminbi, and changes in market liquidity, relative returns and reserve management enhancing the attractions of nontraditional reserve currencies. These observations provide hints of how the international system may evolve going forward.

Since 2000 the share of the dollar in global reserves has fallen from 70 to 59 percent in 2021. The chief beneficiaries are Canada, Australia, Sweden, South Korea and Singapore.

Now this is an interesting observation. And in the context of the debate about the financial sanctions on Russia is is likely to attract much attention as evidence for a shift away from the dollar.

In technical financial terms that is clearly true. Reserve managers are diversifying. But does this shift indicate a shifting balance of power in the global financial system, to the detriment of the dollar and the US authorities? That seems more than debatable.

All of the non-traditional currencies that Eichengreen and his co-authors identify are very much part of America’s extended financial security system. They are all recipients of swap lines. If it came to the crunch in a confrontation with Russia or China who would doubt which side they would be on? Rather than seeing them as rivals or substitutes to the core dollar system is it not plausible to see them as extended buttresses of that system, providing options for diversification whilst continuing to benefit from the liquidity and sophistication provided by America’s financial markets.

As far as the renminbi is concerned, the conclusions reached by Eichengreen and his colleagues is in fact downbeat. As Eichengreen puts it in the FT.

What about faster diversification towards the renminbi? Anyone contemplating moving reserves in that direction will have to consider the possibility that China could become subject to secondary sanctions. Moreover, Putin’s actions are a reminder that authoritarian strongmen can act capriciously when there are few domestic counterweights to restrain them. That President Xi Jinping has shown little inclination to interfere in the operations of the People’s Bank of China is no guarantee that he will maintain that stance in the future. It is no coincidence that every leading reserve-currency issuer in history has had a republican or democratic form of government, with checks on executive power. Russia’s reserve managers have no choice but to turn to the PBoC so long as it continues to grant them access. But for other central banks, an ironic result of the US decision to weaponise the dollar may actually be to slow international take-up of the renminbi.

March 28, 2022

Chartbook #105: Heat pumps for energy sovereignty – Europe’s options in the face of Putin’s War

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is driving Europe to reconsider its energy policy options.

I featured the German debate about immediate sanctions in Chartbook #97.

Chartbook on Substack

Since then, the substance of the German debate, or rather the lack of substance in the debate, has been disappointing.

I want, instead, to focus on three excellent contributions that are all pitched at the broader European level.

Following the invasion, on 11 March 2022, EU heads of state agreed to phase out EU dependency on Russian fossil fuel imports as soon as possible. With this target in view, the European Commission will prepare a “RePowerEU” plan to be presented by the end of May 2022.

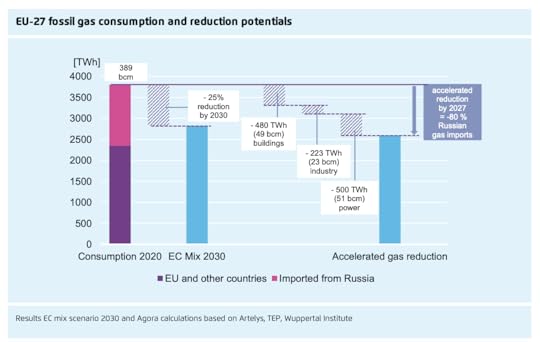

The most substantial is the memo from Agora Energiewende written by a team headed by Matthias Buck. They makes a powerful case that the principal goal of energy policy in Europe at this moment, should be a step change in efforts to reduce fossil fuel consumption. This will be done by an urgent new drive to increase efficiency of energy usage and a major new wave of investments in renewables.

As the Agora Energiewende team argue. By 2027, energy efficiency measures, district heating and a massive, continent-wide drive to install heat pumps could save 480 TWh in energy used in buildings. In European industry, likewise, efficiency measures and electrification in low and medium temperature heat processes can provide for 223 TWh savings. In addition, a dramatic ramp up of wind & solar PV installation combined with more system flexibility could contribute 500 TWh in the power sector.

Together these measures would take out 80% of the energy demand currently covered by Russian supplies.

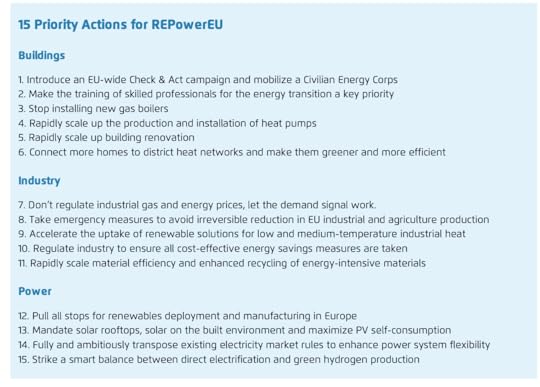

The specific list of 15 proposals is no ambitious, but also seems doable.

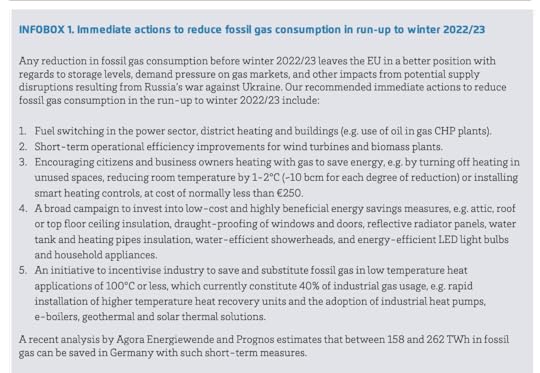

One particularly interesting aspect of the report is the attention paid by the Agora team to what is the most urgent issue in political terms: the crunch that Europe and Germany in particular is likely to face over the winter of 2022-23.

Getting broad-based buy-in for some packages of measures of this kind in Germany, is crucial if Europe is to harden its position versus Putin on energy imports.

One of the things that makes these kind of proposals so dizzying is the way that they spell out the relationship between macro-level concerns of geoeconomics, and the minutiae of heat pump installation and the efficiency of boiler operation. This gives a whole new meaning to the notion of realism in that it forces us to reckon with the fact that very large-scale trade offs depend on rather small-scale technical knowledge. And we need that knowledge not just to assess the hypothetical viability of a program. We need it to be embodied in the labour force, if any of this is going to happen.

Finding these efficiency gains and then training the skilled labour to actually carry out the program will require huge parts of European society to become much more savvy and expert in all things energy. It is akin to the revolutions implied by motorization or digitization. We need the entire chain of energy production, distribution and use to be brought out of the black box and opened up to massive collective experimentation and implementation.

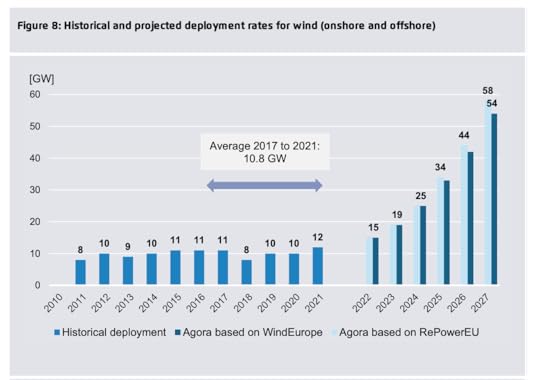

To achieve the targets now set for Europe’s renewable energy capacity by 2030 – to get from 350 to 900 GW within 8 years – will require, as the Agora team point out a “true European industry project”. The rate of annual new installation needs to surge at a spectacular rate.

Are these rates of installation plausible? Are they realistic? As Agora comments:

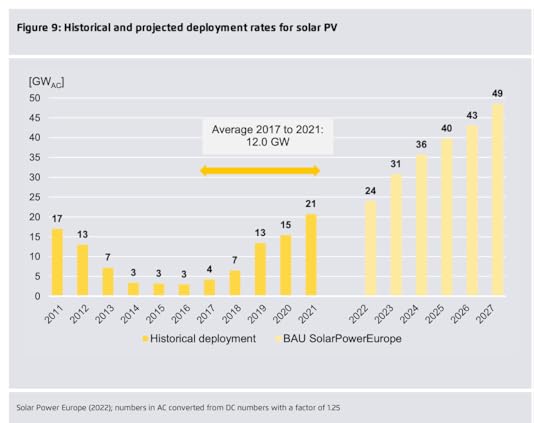

The updated wind power installation target of 480 GW by 2030 is aligned with the industry’s estimates for the end of the decade, provided an enabling regulatory framework and favourable funding conditions are in place. Around 80% of the new wind turbines will be built onshore, the rest offshore. However, an instant and real gearshift in scaling new wind turbines is needed to reach the projected deployment pathway. While the RePowerEU target for wind reflects the upper end of industry’s potential, the solar PV industry could see Europe reach an installed solar capacity of around 600 GW by 2027 under its “accelerated high scenario” – assuming that the EU were to follow an ambitious high policy support regime mirroring China’s approach to solar PV expansion.

If you look at the recent trajectory of solar installation in the EU it becomes clear that what is needed is a dramatic turnaround. Since the highpoint of 2011 it has been heading in the wrong direction.

In the long-run using less energy saves money. The Agora team estimate that currting 1200 TWh reduction in gas consumption by 2027 would save an estimated 127– 318 billion euros and generate additional savings going forward. The savings would be even larger if prices were to settle at the hugely elevated levels we have seen recently.

But, getting those savings will require investment.

The Agora team suggest that their measures would need to be flanked by a new EU Energy Sovereignty Fund, modelled on NextGenEU and equipped with 100 bn EUR until 2027.

This figure is not the cost of investment, which will be far higher. It is the public support necessary to make renewable projects investible and to stabilise their revenue streams. How much subsidy is actually needed will vary depending on how expensive fossil fuels become (the more expensive the better from this point of view) and Agora suggests a bandwith from 30 billion to 285 billion euros, in the event that fossil fuel prices were to plunge.

As an important side note, the Agora team note that

Transmission and distribution grid investments were not modelled as part of this analysis. Based on various scenarios (Goldman Sachs, McKinsey, Eurelectric and EC modelling), estimates range from 0.9 billion euros to 3 billion euros of grid investments per additional GW of RES in the EU, resulting in 470–1650 billion euros of cumulative grid investments for this decade. This compares to 130 bn between 2011-2020 according to Commission data.

Given all the various measures needed to address the crisis, these estimates seem on the modest side. Mario Draghi has spoken of 2 trillion euros in spending on energy, defense and social welfare to cushion the impact of the shock. That raises the issue of Europe’s fiscal constitution.

In 2020 Europe made a huge leap forward with the issuance of common debt to finance the NextGen EU program. Christian Odendahl and John Springford of CER argue that the same approach should be taken to finance the response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

The necessary spending should be financed by raising taxation, cuts to fossil fuel subsidies, national borrowing and a new program of common borrowing.

During the pandemic, Europe has found common resolve in fiscal policy few thought it could gather. Considering that Europe’s security (and once more its economic recovery) is at stake, it is also in the interests of the richer North that the East and the South are able to invest. The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is a smart combination of transfers from richer to poorer member-states, and cheap loans (in effect, subsidised national borrowing), in return for reforms and investment commitments. Europe should put together a RRF 2.0 to focus on energy that is green and secure, that is, on projects that can rapidly reduce the need for imported fossil fuels. That would make Europe as a whole less vulnerable to Russia, and will allow all countries to invest in energy and defence with the same boldness that Germany has done.

European policy-makers should use this crisis to secure the triple dividend that green investment can bring: make Europe less dependent on Russian energy, help fight inflation and reduce Europe’s carbon emissions. Match that with a triple funding of taxation, national and European borrowing, and Europe will have made another big step forward towards meaningful integration where it matters: in protecting two of Europe’s most important public goods, security and a stable climate.

The argument over the future of the EU’s fiscal constitution had begun already before Putin unleashed his war. It is now more urgent than ever.

In 2020 the EU demonstrated the creative effect that can be achieved not by rehashing old points of contention, but by setting a new agenda. In that spirit Martin Sandbu makes a typically constructive suggestion in his regular column in the FT.

If the EU is going to go through a painful phase of transition in weaning itself off Russian gas, why not turn this into a driver of a new common policy of energy purchasing.

Europe can also turn energy policy into an active tool of external influence. The EU is — not before time — probing its ability to constitute a buyers’ cartel. … on Friday the European Council vowed to work on a common purchase platform. This is a momentous move. Consider the global effects should EU countries collectively procure and manage the gas needed to fully replenish the bloc’s gas storage every year. That would mean annually buying up to 100bn cubic metres of gas, about one-tenth of the world’s annual trade. If it was all bought as liquefied natural gas it would be one-fifth of the LNG market. If largely concentrated in the summer, the temporary market share would be higher still.

In the short-run this will likely drive prices up, but, as Sandbu points out, from the point of view of the energy transition that is only to be welcomed.

In the long run, joint procurement would make it easier for EU countries to pre-announce plans for scaling down gas use — which, through its global market influence, would cast doubt on the wisdom of investing in long-term gas development elsewhere. The overall effect would be a boost to incentives for global renewable energy investments today.

The EU is not ready overnight to become a gas-buying cartel at scale. It will have to build up expertise and boost its regasification and domestic piping capacity. … The 1970s shocks came from the young Opec flexing its muscles. The 2020s shocks should give birth to a European anti-Opec.

Again and again, the arguments comes back to this double point – expertise and investment. Plus, the political coalition building implied by Odendahl and Springford’s financing roadmap.

Upcoming on Chartbook:

The 2nd round of the exchange with Unhedged – on Larry Fink and the end of globalization.

More on Mariupol

Barry Eichengreen’s vision of the dollar’s future as a reserve currency

In medias res: An appreciation of Deborah Cohen’s brilliant Last Call at the Hotel Imperial

Luxembourg: the making of a European financial center

and I guess I probably will have to say something about my vision of “synthesis”.

Thanks to everyone for their support and a many kind words of late. It means a lot!

March 26, 2022

Chartbook #104: From Mostar to Mariupol – Urbicide and MOUT

In trying to wrap my head around the Mariupol siege and the battles for the cities of Ukraine that seems to be looming, I have been going back to two bodies of writing that were very much to the fore in the 1990s and 2000s:

(1) the military-technical literature on Military Operations on Urban Terrain (MOUNT).

(2) and the literature on “urbicide” – war waged not just on urban terrain but against cities as such – work which came out of critical urban sociology.

Strands of both literatures were important in helping to shape the study of what one might loosely call “new wars” from the 1990s onwards.

Tellingly, the notion of urbicide coined by anarchist science-fiction author Michael Moorcock in 1963 was first taken up by critics of urban redevelopment in the United States, to characterize the bulldozing and reconstruction of American cities around the needs of the car.

These interventions were not only destructive of urban space, but went hand with the clearance of Black neighborhoods and new forms of segregation. In light of the shock, it hardly seemed exaggerated to refer to a war on urban space.

In the early 1990s, the concept of urbicide was revived with a more literal intensity to make sense of the appalling destruction of the towns and cities of Bosnia in the Yugoslav wars. In particular, it was mobilized in 1992 by Bosnian intellectuals and architects to conceptualize the destruction of the historic city of Mostar.

Some of the testimony and documentaries of the period are truly shocking in their uncensored form. This report by Jeremy Bowen, on life and death in Mostar -“UNFINISHED BUSINESS” – BBC 1993. (The War In Mostar) – is unforgettable. https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embe...

The return of siege warfare forced a reflection on the longer history of this kind of warfare.

As Mary Kaldor noted in her essential work on “New Wars”, one way to read the Yugoslav conflict was as a collapse back into archaic ethnic strife. But, as the decade wore on that became increasingly implausible. Instead, what it seemed that we were witnessing was a new configuration of war, or the mode of war-making.

To simplify a huge debate brutally, “new wars” were more informal, unconventional, asymmetric and they were conflicts taking place in a world that was increasingly urbanized. Ever more often cities became battlefields.

As Michael Desch put it rather brutally:

Asked why he continually robbed banks, Willy Sutton said, “That’s where the money is.” One could answer the question of “why fight in cities?” with the equivalent answer: “That’s where the people are!”

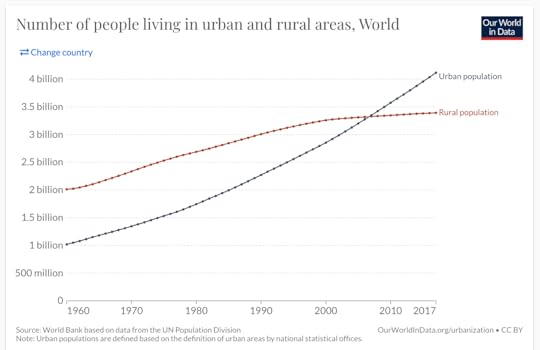

To see the force of that point consider that in 1900 only one in ten of the world’s population of 1.8 billion lived in cities. That is a 180 million people living in cities all told. Only rich countries in Europe and North America had high rates of urbanization. Today, the world’s urban population is over 4 billion. In the first decade of the 21st-century for the first time in the history of our species, the number of city-dwellers overtook the rural population. So yes, if we fight wars today, it is more likely that we will fight them in cities.

Source: Our World In Data

Of course, the “urban revolution” of the late 20th century cannot account for the fact of fighting in city like Baghdad, which was founded in the 700s, or a medieval town like Mostar.

But if we look past the question of historic origins of particular cities, and look instead at the form of the urban space in which combat took place, we can see something distinctive and modern in this new kind of urban warfare from the middle of the twentieth century onwards.

Strategic bombing, for instance, targeted the city as a site of production, social life and politics. Not only did you have to have the technology to do it. But, as the discovered in Vietnam, carpet bombing rice paddy has its limits as a strategy of war.

The genocidal racial visions of the Nazi regime was keyed to the development of urbanism in the negative sense that it envisioned rolling back the tide of urbanization in Poland and much of the occupied Soviet Union. Subhuman slavs would not live in cities and tens of millions of them would not live at all.

World War II also witnessed the battle itself taking place within the modern city. War was directly shaped by the urban spaces created by mid-century modern development. In Stalingrad, the giant factories and city gardens created by Soviet development in the 1930s became battlefields. They proved to be ideal terrain of defense. Fortresses waiting to happen.

As apartments and offices were raised into the air in the form of the high-rise and the skyscraper, so the battle went vertical as well. At the latest since Israel’s siege of Beirut in 1982, war amongst the high-rises has become a recurring image of modern cognitive dissonance.

The dissonance is unforgettably captured by Mahomoud Darwish’s description in Memory of Forgetfulness of making coffee in his modern apartment under bombardment by Israeli jets.

Planned, high-rise, industrial development created the great towering monuments of twentieth-century urbanism and created ideal locations for snipers, who hunted their prey from living room and kitchen windows 30 floors up.

But modern urbanism, for most people in most of the world does not consist of giant factories and high-rises. It has instead taken the form of the sprawling informal developments that surround every low and middle-income city around the world, from Lima to Fallujah.

Accordingly, much of the urban fighting of the late twentieth-century and early 21st-century has been “low-rise”, fought across roof tops and narrow alleys, festooned with pirated power lines.

So ominous is this sprawl of informal settlement from the point of view of conventional military doctrine, that one Israeli analysts referred to urban sprawl itself as a mortal threat to his country.

Uncontrolled spontaneous urbanization is a threat of war! The attacks against us are not physical but are aimed at our very order. The threat is not conventional or terrorist, but invasive. In the context of the global War on Terrorism, this is very important. It is destructive not through direct damage but through its invasive spread which will eventually kill off the host state. As of today we have a tumour installed within the Israeli system. This is a cancerous threat; the cells multiply. We see a mosque appearing there; a mass of buildings here. Thus we see order destroyed.footnote

This horrifying quote comes from retired Brigadier General Eitam, former commander of Iraeli forces in South Lebanon, quoted in an influential essay by Stephen Graham on “The Lessons of Urbicide” published in New Left Review of 2003.

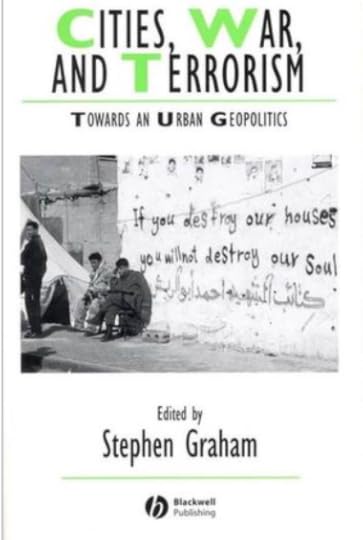

In 2004 Graham edited a landmark collection of essays centered around the theme Cities, war, and terrorism: towards an urban geopolitics. This is essential reading in the current moment.

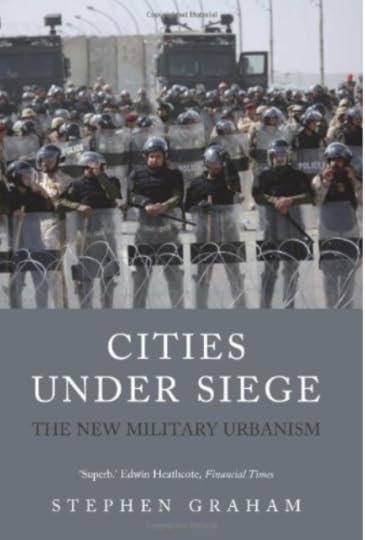

After the massive violence in Iraq and Gaza over the following decade, Graham’s magnum opus on the theme appeared in 2011.

As Graham explains:

War has entered the city again – the sphere of the everyday. •s In the ‘new’ wars of the post-Cold War era – wars which increasingly straddle the ‘technology gaps’ that separate advanced industrial nations from informal fighters – the world’s burgeoning cities are the key sites. Indeed, urban areas have become the lightning conductors for our planet’s political violence. Warfare, like everything else, is being urbanized. The great geopolitical contests – of cultural change, ethnic conflict and diasporic social mixing; of economic re-regulation and liberalization; of militarization, informatization and resource exploitation; of ecological change – are, to a growing extent, boiling down to violent conflicts in the key strategic sites of our age: contemporary cities. The world’s geopolitical struggles increasingly articulate around violent conflicts over urban strategic sites, and in many societies the violence surrounding such civil and civic warfare strongly shapes quotidian urban life. In the process, the distinctions between wars within nations and wars between nations radically blur, making long-standing military/civilian binaries increasingly unhelpful.66 Indeed, what this book labels the new military urbanism tends to ‘presume a world where civilians do not exist:67 All human subjects are thus increasingly rendered as real or potential fighters, terrorists or insurgents, legitimate targets

Fighting in cities had specific effects on the societies caught up in war. The spaces involved might be small, but they were highly significant. A lot of social life is compressed into a city.

As Martin Coward’s Urbicide The politics of urban destruction explained, urbicide had the effect of annihilating the physical space in which communities mixed. Urbicide and genocide were close cousins.

In the mixed communities of Bosnia this was particularly dramatic. As Coward writes about the destruction of the Stari Most bridge in Mostar

These images of the assault on a bridge literally linking east and west gave graphic representation to the notion that the former Yugoslavia was being forcibly ‘unmade’.

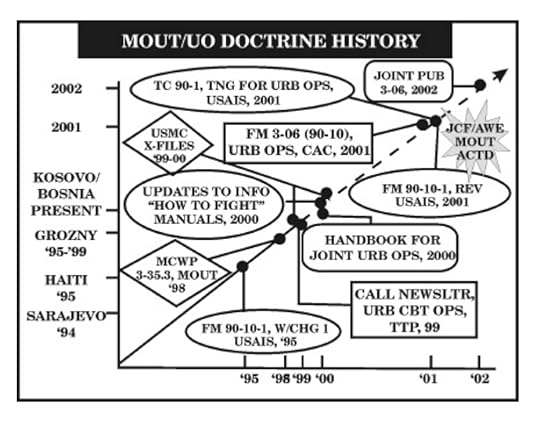

In the 1990s and 2000s, the urbicide literature in the critical social sciences ran in parallel with an intense discussion within the military ranks, the ranks of military advisors, security experts and historians about a new buzzword, Military Operations in Urban Terrain, aka MOUT.

On the basis of their experience in Somalia the US military were scrambling to devise a new urban warfare doctrine.

Source: Soldiers in Cities

For a modern army, centered on fast-moving mobile operations, with ground troops that are not simply tank-centric, but mechanized and motorized in a comprehensive sense, the urban space is challenging. The city may have been remodeled for the motor car. It is no longer ringed by city walls as was true across Europe until the late 18th century. In the early 19th century those walls were commonly razed to enable more traffic. Check out this fascinating history by Yair Mintzker on the defortification of Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries.

But even without fortress walls, the urban space can, all too easily, be made very hostile to an attacking force. For starters, tank guns are generally neither capable of elevating or depressing sufficiently to engage enemies at close quarters in cities. For infantry the urban space is truly terrifying.

It is true, famously, that wider avenues make the construction of classical barricades more difficult (Haussmann etc). But those wide roads also open fields of fire, they are terrifying to cross for attacking infantry. They make excellent killing zones for troops bunkered on either side, or perched at high vantage points to deliver plunging fire.

One early set of lessons of urban combat in the 20th century were collected in the volume edited by Michael Desch, Soldiers in cities. Military operations on urban terrain (2001)

If you want to see the state of the art twenty years on, check out West Point’s Modern War Institute, Urban Warfare Project It comes with a ringing endorsement from General Milley, which could be taken directly from the critical urban studies literature of the 1990s or 2000s.

For good reason, Russia’s two campaigns against the city of Grozny in Chechyna feature in both the literature of urbicide and MOUT. The two campaigns were both an example of massive urban destruction and an example of military lesson-learning between the disastrously botched attack of 1994-5 and the brutal success of 1999-2000.

For a graphic impression of how badly things went wrong in 1994 check out this extraordinary video documenting the destruction of Russia’s 131st Maikop Brigade in Grozny.

Since 1999-2000, unlike the US or Israeli armies, Russia has not been fully committed to full-scale urban warfare.

Perhaps not surprisingly after its experience in Grozny, in 2008 Russia stopped short of a final assault on Tbilisi. The Georgian capital was bombed but never assaulted in earnest.

In 2014, following the occupation of Crimea, there were fights for control of cities cross the Donbas region. But these were relatively small clashes. In March 2014 Putin decided against full-scale invasion in Ukraine. The fighting in the Donbas that followed did not involve major sieges of cities and Russia not did it publicly commit its main force.

On the character of the fighting in the Donbas, I highly recommend Brothers in Arms. Military Aspects of the Crisis in Ukraine edited by Colby Howard and Ruslan Pukhov, published by the CAST think tank in Moscow.

The essay by Mikhail Barabanov on “Viewing the action in Ukraine from the Kremlin’s Windows”, should have been essential reading this winter. He outlines with dramatic clarity the impasse of Putin’s strategy in Ukraine.

In 2015 Russia became involved in the devastating city-fighting in Syria, but mainly through airpower. Russia says that 63,000 service men rotated through the Syrian arena. But a small fraction of those will have been close to urban combat. To judge by the unit affiliation of the casualties acknowledged by Moscow, those close to the action were overwhelmingly air force and special forces as well as a smattering of artillery troops.

This reconfirms the basic point. Unlike the US or Israeli or for that matter the Turkish militaries, the Russian army has relatively little recent experience of high-intensity large-scale urban warfare.

And urban warfare in Ukraine is large-scale.

Mariupol before the war had a population in the 400,000s, bigger than Florence, almost as large as Dublin, comparable to Stalingrad’s population of 490,000 in 1940. The fighting in Stalingrad in 1942-1943 swallowed up entire armies. In Mariupol today neither side has the troops either to fully defend or comprehensively assault the city. The main force in the Ukrainian defense is reportedly a single brigade, the 36th Naval Infantry.

This video shows the Ukraine unit training with US Marines in 2021.

Mariupol is a lot for Russia to swallow.

Kyiv is a challenge of an even greater scale. With 2.9 million inhabitants in peacetime, it is the 7th most populous city in Europe, larger than Rome or central Paris. Kyiv’s population is almost six times larger than that of Stalingrad in 1940. With well-supplied and determined defense, Russia’s entire invasion force on all fronts (c. 190,000 men) could be swallowed up in fighting for just one part of modern day Kyiv.

As one timely post on Linkedin pointed out, Russia’s military experts were preparing sophisticated new schemes for urban warfare in recent years. These involved the use of precision artillery fires to seal off parts of a city.

But little of that has been in evidence so far. Instead, we have seen an ill-directed and bludgeoning assaults lacking clear operational rationale. The suffering of the Ukrainian civilian population has been horrible. But Russia has not yet demonstrated that it has the capacity to mount an urban assault intense enough to deliver the symbolic victory that Putin needs.

March 25, 2022

Ones & Tooze: The Economics Behind Mariupol

More than 100,000 people currently want to evacuate the besieged city of Mariupol in Ukraine. On this episode of Ones and Tooze, Adam Tooze and Cameron Abadi look at the significance of this port city to Ukraine and Russia’s military campaign.

Also on the show, Tooze and Abadi commemorate the Godfather’s 50th anniversary.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

March 23, 2022

Chartbook-Unhedged Exchange: China under pressure, a debate

It is hard to exaggerate the scale of the sell-off in China’s stock markets last week.

The drama caught my attention as it did the attention of my eagle-eyed friends Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu over at the FT’s Unhedged newsletter.

So, it seemed obvious to make China and its prospects the subject of the first of three paired newsletters between Chartbook and Unhedged – call it Uncharted or Hedgebook (h/t @joshspero).

Chartbook will feature three pieces written by the Unhedged team. The first you will find below. To read my piece today, click this link for exclusive free access to the FT’s Unhedged newsletter.

The current plan is to exchange columns every Thursday for the next three weeks.

If you don’t subscribe to the FT’s Unhedged newsletter already, you are missing out. If you are interested in following the mind of the financial markets there really is no better source.

The analysis from Unhedged is sharp. Sometimes technical, but never impenetrable. Plus the writing is great. It is, no kidding, the first thing I check in the FT every morning. It’s a pleasure to be in dialogue with Robert and Ethan.

Our pieces emerged out of email exchange and are closely keyed to one another. You can plunge into Robert and Ethan’s analysis below and then flip over to the FT using your exclusive link. Or you can start with me over at the FT and then come back here.

The choice is yours!

It is, frankly, very exciting to be able to offer readers of Chartbook exclusive access to top content from the world’s premier financial newspaper. In honor of the occasion, I wish I could tint the following newsletter pink. In any case …

… YOU ARE NOW ENTERING THE WORLD OF THE FT’s UNHEDGED:

Adam is clear-eyed about China’s challenges, but is optimistic that they can be overcome.

China’s investment-driven, debt-heavy development model needs replacement. Its geopolitical and economic position will become more precarious if the globe’s authoritarian and liberal democratic blocs decouple, a threat made vivid by the war in Ukraine. Its demographics will be a drag on growth. All of this is plain fact. But Adam sees reasons for hope:

China’s technocrats have, to date, demonstrated competence in managing the economy’s imbalances. “By means of its ‘three red lines’ policy, [China] is stopping in its tracks the most dramatic accumulation of wealth in history … if Beijing manages to stop the largest property boom ever without a systemic financial crisis, it is setting an entirely new standard in economic policy.” Pricking bubbles before they burst and wreak economic havoc is exactly what the US has serially failed to do. “If we look in the mirror, why aren’t we applauding more loudly?” Adam asks. Similarly, the Chinese state’s recent intervention in the tech sector, while it has led to market volatility, is aimed at doing exactly what western regulators want to do, but can’t seem to do: stop huge companies from extracting monopoly rents from the economy. Beijing has policy options. “China needs a welfare state befitting of its economic development. It needs to get serious about ending its dependence on coal. If it needs more housing, it should be affordable. All of this would generate more balanced growth. 5 per cent? Perhaps not, but certainly healthier and more sustainable … if you had to bet on a state which might actually have what it takes to break a political economy log-jam, which would it be? The United States, the EU or Xi’s China?”“On balance,” Adam sums up, “If you want to be part of history-making economic transformation, China is still the place to be.” Indeed there are certain sectors — green energy first among them — where serious investors really can’t reasonably avoid China.

At Unhedged, we have views about the first two points, but they are not well informed. We’re not policy guys. The third point is where we disagree. We just don’t see China as having any good options for maintaining strong growth.

Up until now, investors in China’s equity and corporate credit markets have had to deal with extreme volatility driven by both unpredictable government policy and the fickle risk appetite of local Chinese investors. In return, they have participated in a remarkable growth story, and have been able to do so at a reasonable price, given the often attractive relative valuations of Chinese stocks and bonds.

Focusing for just a moment on the stock market, mainland Chinese equities have performed well relative to the basic global alternatives over the long run. Here are 20-year total and annualised returns, all in dollar terms, through the end of February:

Mainland China has delivered significant extra returns — 87 basis points a year more than the mighty S&P — for anyone willing to hack the wild volatility. But we think China’s underlying growth story is coming to an end as the country’s economic imbalances become unsustainable and global decoupling picks up steam. The volatility and low valuations, on the other hand, are likely here to stay.

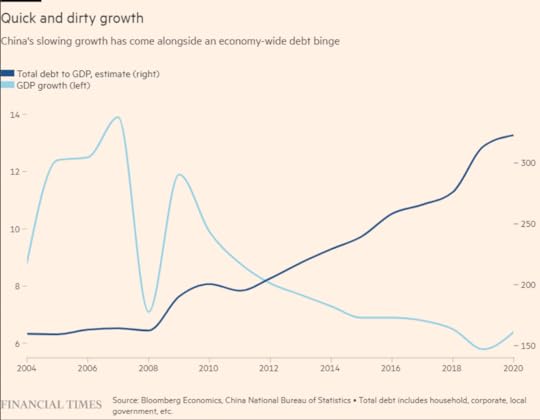

What imbalances are we talking about? In crude summary, China’s growth has been driven by debt-funded investment, especially in property and infrastructure. The problem is that the returns on these investments are in fast decline, even as debt continues to build up. Here are China’s official GDP growth numbers and the country’s estimated debt/GDP ratio:

The imbalances in China’s economy have only gotten worse in the decade since the financial crisis. This can’t go on forever. Eventually, you have all the bridges, trains, airports and apartment blocks you need, and the return on new ones falls below zero (How do you know that you have arrived at that point? When you have a financial crisis).

Another way to describe China’s imbalance is that as the state has driven investment, its households — as opposed to the business and government sectors — have received a very small share of GDP. Here’s an international comparison:

The problem is that without a healthy consumer, China’s only real options to create growth are investment and exports — and at the same time as return on internal investments are declining, the rest of the world, led by the US, are increasingly wary of dependence on Chinese exports.

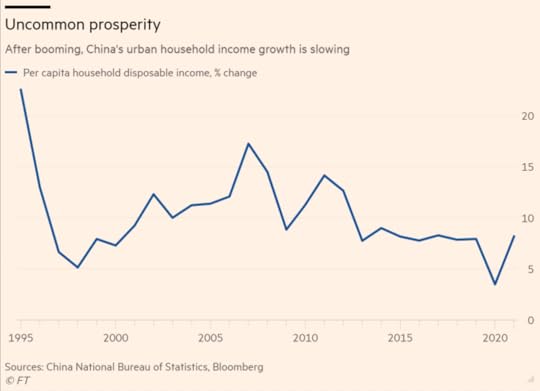

Household income growth has fallen over time:

What are China’s policy options? Broadly, there are five, as Micheal Pettis explained to us:

Stay with the current model.Replace bad investment in things like infrastructure and real estate with good investment in things like tech and healthcare.Replace bad investment with domestic consumption. Replace bad investment with (even) move exports and a wider current account surplus.Just quit it with the bad investment.At Unhedged, we think that options 1 and 5 are not really options at all. The current model will lead to a financial crisis as return on investment falls further and further behind the costs of debt. Simply ceasing to overinvest in infrastructure and real estate, without changing anything else, will simply kill growth.

What about options 2-4? Option 2 might be summed up — as Jason Hsu of Ralient Global Advisors summed it up to us — as China becoming more like Germany. Hsu argues that Chinese policymakers are very focused on not falling into the same developmental traps as Japan, whose investment-heavy model blew up in the late 1980’s, leading to a period of very low growth that persists today (Japan, it should be noted, carried a burden into its crisis that China today does not: a massively overvalued stock market). The idea is that China would steer more and more money away from real estate and towards high value-add sectors from biotech to chip manufacturing.

The problem with option 2 is that investment is such a huge part of the Chinese economy that it is difficult to see how that the capital could be efficiently allocated to the country’s tech-heavy, high value-add sectors, which are comparatively small. In 2020, China’s total capital formation (roughly, net capital invested in property, equipment, and inventories) was $6.4tn or 44 per cent of GDP, double the proportion of the US or Germany. Government policy would struggle to move a meaningful fraction of that to high-value-add sectors without creating hideous distortions. The most promising Chinese firms are swimming in capital as it is. And developing productive capacity isn’t just about capital. It takes things the state can’t rapidly deploy, like knowhow and intellectual property.

Option 3 is more promising. China could start, as Adam suggests, by building up a proper welfare safety net. But it is reasonable to expect pretty serious social and institutional resistance to this sort of mass redistribution. The income that would be distributed to households would come from the sectors that currently control outsized slices of GDP: government and corporations. They will resist. Local and provincial governments would be especially loath to give up resources and influence.

To put the same point another way: why hasn’t China increased its welfare state until now? Longtime China watcher and friend of Unhedged George Magnus suggests it is because of a deep bias in the Chinese policy establishment. “It’s how Leninist systems operate: they think production and supply are everything … if you see a demand problem as a supply problem, you get the wrong answers.” China’s latest policy solution to its growth problem, tax cuts aimed mostly at business, make exactly this mistake. The supply side in China doesn’t need help. Households do.

Option 4, increasing exports’ share of China’s economy even further, may be in the abstract the most appealing. But it runs directly into the fact that both China and the US and its allies have reasons to reduce mutual dependence on their economies. These reasons include China’s relationship with Russia, but are hardly limited to it. The US-EU policy establishment, for example, is not going to stand idly by while China increases its share of the semiconductor market. In the FT on Monday, our colleague Martin Wolf emphasised that the war will make the preexisting tensions worse:

The emergence of geopolitical divisions between the west, on the one hand, and Russia and China, on the other, will put globalisation at risk. The autocracies will try to reduce their dependence on western currencies and financial markets. Both they and the west will try to reduce their reliance on trade with adversaries. Supply chains will shorten and regionalise…

Russia must remain a pariah so long as this vile regime survives. But we will also have to devise a new relationship with China. We must still co-operate. Yet we can no longer rely upon this rising giant for essential goods. We are in a new world. Economic decoupling will now surely become deep and irreversible.

In all, the most likely scenario is that China’s growth just keeps slowing. That does not mean that investors in China will necessarily lose money. But it does suggest that generic China exposure — simply owning Chinese equity or credit indices — is going to be a losing proposition in the long-term. The analogy with Japan is again useful. The performance of Japanese indices has been awful for decades, but certain companies and even sectors have done unbelievably well.

Thanks for reading. Email us your thoughts: Robert.Armstrong@ft.com and Ethan.Wu@ft.com. We do hope you’ll consider subscribing to the FT. If you do, you not only get Unhedged, but the world’s best newspaper to boot.

March 22, 2022

Chartbook #103 How refugees’ need for cash exposes the limits of Euro sovereignty

When a nation is fighting for its life, with its cities are under bombardment and approaching a fifth or more of its population in flight, what is its currency worth?

If money functions in a matrix of public and private relations of financial obligation, authority and credit, what happens when those relationships are violently attacked by an outside force?

It might seem a frivolous question. There are more important things in life than money. This is a moment at which life and death are at stake.

But the question cannot be dodged either at the public or private level.

Money is a defining instrument of state sovereignty. The capacity to tax, the circulation of currency are key functions of government. The means that the Ukrainian military have at their disposal to fight off the Russians are limited by Ukraine’s pre-war defense budget and its current ability to access new weapons and support.

And for the millions of Ukrainians fleeing the devastation the question poses itself in an urgent private form.

Having found a place of safety the next questions is: “How are we going to live? What are we going to live on? What is left of what we had?”

At that point money reenters the picture with a vengeance. And it does so not just for the refugees.

Refugees are defined by dispossession. They leave their homes and the vast majority of their property behind. What will survive is at the mercy of the war, looting by the occupiers, neglect, decay.

But what of their financial claims? What of bank accounts, credit cards, cash?

These are supposed to be the fungible, liquid, abstract forms of property. They are supposed to be the store of value, the means of exchange, the unit of account. Do those functions of a national currency survive, as a state fights for its existence?

For the millions of refugees flooding to the West this is a matter of acute material concern, but it is also more than that. It defines how much of their normal identity they are losing.

In market society if you can pay, if your credit is still good, you are not a charity case. If your cash is no good and your card no longer works, you become dependent.

“Crossing the border from Ukraine into Poland at Zosin, there was a lot of help on offer — free food, free diapers,” one Ukrainian refugee told POLITICO. “But nobody willing to exchange cash.”

The contrast is telling. Gifts are one way transactions. Exchange would involve reciprocation.

Poles are generously giving of their own. They are less interested in accepting dubious claims on Ukraine in exchange for valuable Polish currency.

As Sam Fleming, Martin Arnold and James Shotter of the FT report:

The problem has arisen because Ukraine has suspended most currency trading and frozen the official exchange rate for the hryvnia at prewar levels. It has also imposed a moratorium on foreign exchange payments except for those supporting the country’s war effort.

This means that the actual exchange rate of the hryvnia is indeterminate.

The refugees are making forced sales. The exchange booths still willing to take their currency charge exorbitant premia effectively depreciating the Ukrainian currency from 7 hryvnia to the zloty to something closer to 20.

Ukrainian payments cards are, in many cases, no longer working outside Ukraine. ATM machines across Eastern Europe are swept bare of cash, both by refugees and locals rushing to withdraw means of payment.

The dash for cash has been contagious. As far away as Sweden, there has been a surge in demand for cash.

No one wants to say it out loud but the judgement of the exchange booths is harsh. Ukraine’s resistance may be heroic, one may wish the refugees well, but no one has much hope for their currency.

If one follows that thought to its conclusion, you might ask whether exchanging hryvnia for hard currency is not beside the point. As Politico remarks:

An alternative would be to only hand out cash (Polish zloty or euro) to refugees, a much simpler and legally straightforward operation. But authorities worry this could send a troubling signal to Ukrainians that Europe has no trust in the future of Ukraine’s currency.

So this is the dilemma: Europe is not giving up on Ukraine. It is determined as far as possible to preserve the belief in an unimpaired Ukrainian monetary sovereignty. And it clings to that idea even as millions of Ukrainians are desperately fleeing their country and in doing so fleeing its currency. They need out.

Presumably the hope is that at some point in the future Ukraine will be restored and normal financial and monetary relations can resume. In the mean time a painful tension must be bridged. This will require money, from Europe. And that is where the problem starts.

Since this is a question of cash, ATMs, payments cards, exchange booths and of banks, the central banks is the agency of government that matters in the first instance.

In the front line of the crisis, the National Bank of Poland (NBP) and its Ukrainian counterpart on March 18 signed an agreement that will enable each adult refugee to exchange up to UAH 10,000. The exchange will be possible at the official exchange rate as of March 25. It should result in c 1,400 złoty, or €300 per adult refugee. Given the number of refugees entering into Poland that is an obligation on the Polish central bank to the tune of hundreds of millions of euros. The exchanges will be done at branches of a Polish state-owned PKO BP bank.

Under many plausible scenarios, the tens of billions of hryvnia that Poland will acquire in exchange for the billions of zloty it dispense, will turn out to be worthless. The Polish tax payer, or some other multinational facility will have to absorb the loss.

This is a laudable commitment by Poland and it begs the question of what the rest of Europe is willing to do.

The Bulgarian central bank has said it is working on a facility while in Romania, the local unit of Erste Bank lets Ukrainians convert around 400 euros worth of hryvnia.

These are commendable initiatives, but they only go so far. 300-400 euros per adult is not going to last long.

What can Europe as a whole and specifically the ECB do?

When Christine Lagarde was asked about the response of the ECB at a recent press conference, she gave the following answer.

The second question is: what would the ECB’s reaction be if the Ukraine Central Bank was to request a swap line from the ECB?

I will start with the second one. We are actually exploring together with other European authorities and in particular with the Commission how we can deploy tools in order to support the Ukrainian people and the Ukrainian authorities. So clearly looking at how support can be structured, whether under an existing product – you mentioned swap line, repo line, or other products – because clearly, we have conditions under which we can extend swap lines and repo lines. If those conditions are not satisfied, we need to find alternative ways of providing support. That is what we are doing both in relation to the authorities, but also in relation to the people of Ukraine who, when they become refugees, unfortunately past the border need to access alternative currencies to theirs, which as a result of the decision that was made is not convertible as it used to be. So we are really working hard. I hope that in the next few days we’ll be able to provide tools and means to extend support to both the people and to the authorities together with the Commission and sometimes in some cases national authorities within the Eurosystem.

As one anonymous central banker remarked: “The simple question is: Who will carry exchange rate-related risk? It cannot be the central bank.”

Why not, you might ask? Don’t they print the money? But that, as far as the ECB is concerned, is precisely the problem.

Absorbing the losses on the transactions with Ukrainian refugees could be seen as tantamount to “monetary financing” i.e. printing money to support national finances, which was regarded with horror by the original architects of monetary union. And as a result it is strictly forbidden by the Maastricht Treaty.

Fear of monetary sovereignty is, once again, the problem.

As another ECB source remarked to Balazs Koranyi and Jan Strupczewski of Reuters: remarked: “This would be a humanitarian, goodwill effort, rather than a regular policy instrument, but we are still bound by laws so it’s not like we could just say, come, we’ll covert it for you.”

Within its legal charter, the ECB cannot act, unless it is provided with a cast iron loss guarantee by Europe’s national governments. And they, unlike Poland, have yet to come up with a formula.

As Christine Lagarde, ECB president, told the FT on Monday,

the central bank had spent the weekend seeking a solution permitting it to convert refugees’ hryvnia into euros. “It’s complicated,” she said. “We need a guarantee on the conversion. Sometimes our legal frameworks show their limits in crisis times.”

The obvious need is for a jointly guaranteed European facility with the ECB as the facilitator of transactions.

Actual conversion would be left up to commercial banks.

Part of the solution might include allowing Ukrainians to open bank accounts and spend hryvnia electronically.

But the critical question is what exchange rate to set for the conversion. If the refugees are to be assisted, the exchange rate must be better than that currently on offer on the black market. That implies larger eventual losses and will mean that European governments will likely impose an upper limit to the amounts that can be converted. The exchange rate and the cap are the critical issues.

As one source remarked to Reuters: “we have days, not weeks to figure it out.”

That was on March 11th. As of this morning, March 22, as reported by the FT, there is still no clear solution in sight.

In Europe since the Ukraine crisis began, the talk about sovereignty has reached a clamorous pitch. But sovereignty has preconditions. And one of them is a central bank that is not hobbled, but is able to perform the full functions of a sovereign monetary actor. Ought it not to be a matter of shame that it is central banks of EU members not yet in the Euro – Poland, Bulgaria, Romania – that are able to respond promptly to the needs of Ukraine’s refugees, whereas the far-richer eurozone members are paralyzed?

In this crisis, it is not just Ukraine’s monetary sovereignty that is being put to the test.

March 19, 2022

Chartbook #102: Soft landing in heavy weather – The Fed’s “no drama” policy.

We are at a strange juncture.

The symptoms seem familiar. We have experienced months of rising inflation and are living through something akin to an inflation scare.

Interesting. According to the UMich Survey, there's been a huge surge in people saying they've seen unfavorable news stories about what's going on with inflation.

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) March 18, 2022

Whereas there's been a big drop in news stories about progress made in the labor market. pic.twitter.com/5IOLyefMWI

There is war involving Russia, a major energy exporter. The war in Ukraine compounds an existing crisis in the global energy economy. There is even talk of oil boycotts.

For some commentators the shades of the 1970s are irresistible. Larry Summers is the most notable example of this tendency.

But the retrospective tendency is not confined to the centrist mainstream. Without drawing false equivalences, some of the left Keynesian discourse on inflation also has a “back to the future” feel. The price controls debate is after all a deliberately historicizing provocation. The idea is as scandalous as is it is to mainstream economists because it smacks of a return to what they regard as the failed experiments of half a century ago.

Rather than back to the future, the left position is better described as “back to an alternative future”.

Given the actual macroeconomic track record in the 1970s and 1980s it surely ought to be mysterious why anyone would take the record of Paul Volcker and the costly monetarist experiments of the era as a success rather than a brutish demonstration of the effect of a sudden tightening of the dollar system.

Nevertheless, homage to Volcker is the charade that Fed chair Jerome Powell enacted in front of Congress last week. As Colby Smith reported for the FT.

Testifying before Congress earlier this month, Jay Powell was asked if the Federal Reserve was prepared to “do what it takes” to get inflation back under control — and if necessary, follow in the footsteps of his venerated predecessor, Paul Volcker, who regained price stability “at all costs”. Calling the late Volcker “the greatest economic public servant of the era”, Powell responded: “I hope history will record that the answer to your question is yes.”

As less credulous observers noted, the Fed’s actions speak louder than words and they seem to suggest the very opposite of any Volckerian inclinations.

Powell struck an optimistic note at a press conference on Wednesday, saying the sheer strength of the US economy meant it could “flourish” in the face of less accommodative monetary policy. Economists have welcomed Powell’s embrace of a much more aggressive policy approach, compared to the gradual pace signalled just three months ago. They warned, however, that the amount of monetary tightening potentially needed to quell inflation may produce much more economic pain than the Fed is willing to admit.

The real novelty in the current situation is this stark discrepancy between discourse and practice.

Whilst the rhetoric on all sides is redolent of the 1970s and 1980s and the need to make tough choices, America’s central bank. The Fed has been slow to raise rates and when it did, it chose to raise them by no more than a quarter percentage point. This week it rejected the idea of sending a dramatic signal by making a half percentage point move.

Much as Larry Summers demands that interest rates must be hiked faster than inflation, the Fed is holding back. It it is refusing to add to the drama of the situation by delivering a true monetary shock.

To its critics, Powell’s Fed has simply lost the plot. It is “behind the curve” and incoherent. As John Authers pointed out in a typical sharp-eyed piece:

The (most recent) inflation estimates (by the Fed) are, obviously, much higher. Perhaps more shockingly, they are all over the place. This year has nine months to run, and yet the spread of estimates for inflation at the end of it covers almost two percentage points. There is no consensus. That is alarming, and prompted some to fear that the Fed was admitting it didn’t know what was going on.

Then there’s the question of the Fed’s internal inconsistency. The FOMC allegedly believes that inflation will come back down to 2% for the long term, without a recession and with barely an increase in unemployment. On top of that, the committee also thinks that the fed funds rate will top out for the long term at 2.4%. In the decade that the Fed has been publishing the dots, this is the lowest projection for long-term rates on record. Somehow it has actually dropped 10 basis points since December, despite rocket-like inflation, omicron, and a land war in Europe:

But if the Fed, according to the hawks, has lost the plot, the question is why? In the standard model of policy-failure in the 1970s the underlying logic derives from a balance of social forces – organized labour v. capital. That is hardly a plausible story today.

One can hardly claim that Powell’s Fed is under pressure from powerful social forces, other than perhaps the stock market. Last fall the largest industrial dispute across the workplaces of the United States was the graduate strike on the campus of Columbia University. We are not actually back in the 1970s.

In any case, whatever the reason for its complacency, the cardinal sin is not to have listened to the hawks like Larry Summers.

The Fed’s defenders point to the fact that it is not only the Fed that is complacent. Bond markets don’t believe in a scenario of runaway inflation or violent recession either. On this view, the markets and the Fed are muddling through an unprecedented situation – COVID, supply chain difficulties, energy shock, Ukraine – as best theyt can. If this takes a bit of hypocritical mood music about Paul Volcker, that is a small price to play.

Finally, on a third reading, the Fed is acting entirely consistently, but it has adopted a model of the American economy which denies the idea that there is a strong linkage between the current inflation and the underlying state of the American economy.

As the FT remarks:

The Fed’s recent forecasts are notable for the central bank’s apparent belief that it can painlessly reduce inflation. The central bank predicts that the unemployment rate will fall further to 3.5 per cent and then remain there, even as rates rise from the current 0.5 per cent to an expected 2.8 per cent by 2023. Powell has previously expressed admiration for his predecessor Paul Volcker’s choices in the late 1970s to raise rates aggressively even in the face of mass joblessness; the latest forecasts deny such trade-offs even exist.

At the end of the last year Jerome Powell officially buried any talk of “transitory” inflation i.e. inflation induced by temporary and abnormal COVID-related shocks. And yet the modesty of the Fed’s moves on interest rates suggest that the Fed still believes that they are a not the best weapon with which to moderate price increases. As Ramesh Ponnuru argues, the theory seems to be that the inflation we are experiencing is simply not best addressed by monetary means.

As Joe Weisenthal points, there are a variety of structural factors other than energy prices that are helping to drive inflation.

The @neelkashkari piece on why inflation has stayed hot longer than he expected is a good read.

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) March 18, 2022