Adam Tooze's Blog, page 26

January 22, 2022

Chartbook #74: Crypto and the politics of money

I’m not into crypto. I talk about it reluctantly. I don’t like repeating myself but I still like these lines from Chartbook Newsletter #15

Money talk is political talk. We should be selective in the political talk we engage in. I don’t like the politics of crypto/bitcoin. Indulging silly money talk is to indulge silly and dangerous politics. We should avoid doing that.

Money is tricky stuff. For some serious money talk check out Geoff Ingham’s excellent 2004 primer on The Nature of Money.

I don’t like to talk about crypto because I regard it first and foremost not so much as a technical or commercial proposition but as a conservative/libertarian efforts to escape the shadow of the political order of money that has half-emerged from the collapse of Bretton Woods.

To paraphrase Gramsci, crypto is the morbid symptom of an interregnum, an interregnum in which the gold standard is dead but a fully political money that dares to speak its name has not yet been born. Crypto is the libertarian spawn of neoliberalism’s ultimately doomed effort to depoliticize money.

But, in the end, as I conceded a year ago, not talking about this morbid symptom feels like a cop out. So, periodically, you have to.

This time the occasion was a request from Evgeny Morozov of the Syllabus. Evegeny is a fascinating and persuasive guy. And Syllabus is one of the cooler things on the interwebs. The Syllabus has an entire section devoted to crypto and digital things. Evgeny persuaded by brilliant and wise friend Stefan Eich to do an interview with him on the politics of money, Keynes and much else besides.

Stefan essential new book on political theory and money, The Currency of Politics, will be out with Princeton University Press in May.

So, who am I to resist, especially since Evgeny wanted to talk about those lines from Chartbook #15. Evgeny was also nice enough to agree to a co-publication between the Syllabus and Chartbook. So here it is.

Evgeny started our conversation with a great opener, which I will quote with minor amendment:

One of the most interesting things in the interview that follows is Adam’s critique of the belief, shared by many crypto-enthusiasts, that fiat money is not backed by anything. As a veteran observer of the recent financial crises, Adam is well-positioned to note the role that macrofinance plays in “backing” fiat money as we know it. …. (AT: The idea of fiat money not being “backed”) points to a certain one-dimensional formalism, which I’ve noted in other discourses that circulate around crypto. These technologies do present solutions to institutional deficiencies and problems of various kinds. However, their account of the underlying institutions that generate them either is extremely simplistic, grounded in all-too-rigorous interpretations of formal definitions (e.g. “fiat” = “no backing”; “governance” = “voting”; “institutions”= “entities with an org chart”; “law”= “contracts”). Perhaps, a closer, attentive engagement with the discipline of history – Adam’s specialty – is the way to fill in these analytical gaps.

~ Evgeny Morozov

We then went into the exchange. Evgeny’s lines are marked with EM, mine with AT.

EM: Before we delve into the specifics, perhaps you could give us a short outline of how you read cryptocurrencies and their broader political and economic import. Are they money? Why or why not?

AT: In a simple functionalist way, you can define the role of money as consisting in some combination of three things: means of payment, store of value, unit of account. Clearly, in certain circuits folks have begun to price things in cryptocurrencies – NFTs, digital art objects, etc. – so crypto is serving as some kind of unit of account. But crypto is not a particularly useful unit of account because its value in terms of other units of account fluctuates so much, which also means that crypto is a bad store of value (unless you have a high preference for speculative gambles) and is unlikely to become widely accepted as means of payment. (In an upswing, the risk is that, in using it, you undervalue your tokens. In a downswing in crypto prices, only a highly risk-tolerant merchant would accept payment in crypto, unless at a large discount.)

If we depart from such functionalist accounts of money and stress instead the role of money in constituting community, founding polities, etc., then crypto has clearly gained purchase in certain communities and helped to configure and constitute them. The question then is, how stable, robust, and widespread are these social groupings that have organized themselves around this money and/or how powerful are their opponents?

EM: In one of your newsletters from March 2021 – your first public foray into analyzing crypto – you cite Gramsci and write that “crypto is the morbid symptom of an interregnum, an interregnum in which the gold standard is dead but a fully political money that dares to speak its name has not yet been born. Crypto is the libertarian spawn of neoliberalism’s ultimately doomed effort to depoliticize money.” Could you expand a bit more on what this “fully political money” might look like, perhaps by contrasting it with the money that we have now?

AT: I should admit upfront that the idea of a “fully political money” is nothing more than an aspiration, a telos, a direction of travel. Indeed, you might ask whether we can live with anything that is “fully political.” After all, our politics regularly lurches into anti-political foundational gestures, not dissimilar to the gestures that we make when we try to found money on gold, or central bank independence, or a mechanical monetary policy rule, or an algorithm.

In this sense I absolutely agree with my dear friend Stefan Eich when he says: “there always been hysteric pronouncements about the fragility of fiat money, but … we might actually want to look at these voices as themselves part of the politics of money.” The politics of money includes an anti-political strain.

After all, the same goes for the law, which I would think of as the closest we have to a fully political architecture of social organization. In the limit, all too often, legal structures seek to anchor themselves in some more solid foundation than that provided by more or less widely accepted and deliberate societal agreement. Constitutions reach for god, or nature to do the work for them. (One brilliant account I learned a lot from is Bonnie Honig’s essay “Declarations of Independence” (1991)) Perhaps we cannot do without such gestures. But that is what I am gesturing to: the possibility of organizing ourselves around money that is accepted for what it is, i.e. a conventional set of arrangements ultimately arising out a complex of social and political interactions, part of the material constitution of our society, warts and all.

EM: I get what you say about neoliberalism’s influence on crypto and the connections you draw to the broader Hayekian vision for denationalizing money, which Stefan Eich so brilliantly documents in his essay and his forthcoming book. But I think there’s a second source of legitimacy – from the left – for many less visible but, perhaps, more ideologically important crypto projects, which is often ignored by such critics. For many decades now, the ideology of what we can call “localism” captured the imagination of the left, especially of those currents that look very favorably on the communitarian legacy of the early 1970s: these are people who celebrate cooperatives, time-banks, and, inevitably, alternative and complementary currencies (here I’m thinking especially of Peter North’s book Money and Liberation).

I wouldn’t say that these movements criticize the state the exact same way that the neoliberals do; they do complain about hierarchical, rigid, and bureaucratic structures – but it’s mostly a humanist rather than economic critique. A lot of this passes under the banner of “solidarity economy” or “alternative economy,” and it’s not very hard to see how this would fit into a conception of a post-capitalist society that is more decentralized, more autonomous, and, perhaps, more democratic. To start with, most of these “alternative economies” operate on tokens – so a shift to crypto is quite natural. I myself am critical of such localist tendencies, as I find them unable to offer any counterpoint to the likes of BlackRock or Amazon. But I can easily see how the crypto allows them to revive many of those earlier utopian undertakings and package them in a much more innovative way. What do you make of such efforts in general? Should this “fully political money” that you advocate be global rather than local in outlook? Are people trying to find localist uses to crypto mostly living in a fantasy world – not that different from, say, ethical consumption?

AT: Actually, I have a lot of sympathy for that kind of local money project. After all, it explicitly recognizes the societal project or counter-project it is involved in and I happen to be more sympathetic to its politics than that of the libertarian, anarcho-capitalists. If we are trying to think through what a fully political money entails, then we cannot shrink from political judgment. That is what makes it so disconcerting as an idea. If money is a tool of collective organization then it is the purposes of the collective project that are first and foremost important. What I regret about some localist visions is not the localism as such but the idea that localism should then be tied to a foundationalist move, i.e. to something which is, in fact, not part of the community at all, but outside it.

Furthermore, even local monies are going to need monetary policy. As a good Keynesian I can never forget Paul Krugman’s analysis of babysitter currency and the liquidity trap suffered by the Capitol Hill Babysitting Co-op. Small scale may promise but cannot deliver an escape from politics. And the need for monetary politics should not be regarded as a curse but rather the opposite, an opportunity for collective learning-by-doing and experimentation. That is another way of putting the essential point. Monetary policy is not a curse to be driven out by some non-political binding mechanism, algorithmic or otherwise, but an opportunity to expand the range of our politics and collective self-organization.

EM: The whole new field of “cryptoeconomics” seems to ignore the macro-level and just focuses on getting the Homo Economicus to behave through better-designed incentives… If one were to write an intellectual history of cryptoeconomics, it’s going to be almost exclusively dominated by mechanism/market design and game theory, its non-existent macro-economics stuck in denial somewhere between the extremes (all on the far-right) of someone like Murray Rothbard and his libertarian opponents who preach Free Banking. This ignorance of the macrofinancial is premised on what seem like wrong-headed ideas about the nature of fiat money and it not being “backed” by anything… Could you briefly tell us why in your opinion the standard crypto critique of fiat money makes a mistake in ignoring the ways in which the structures of macrofinance actually do back, say, the US dollar?

AT: Well it is a vertiginous realization isn’t it? That money is not backed by “anything.” I’ve shocked year after year of smart college students by forcing them to face that reality. There are always a significant minority who cling to some version of the gold standard. They actually do believe that when you “take the note to the central bank,” you will get “something” in exchange. It’s not an easy idea to give up. It’s not unlike the vertiginous feeling that is engendered by realizing that language is not “backed” by anything. We are familiar with solutions to this problem. Create a physical object that can be used as a reference for a word, a definition, a standard, etc.

But then I also find that it is not difficult to reverse the flood of skepticism and nihilism and simply reply: “No. Money is not backed by ‘any one thing.’ It is far better than that. It is backed by ‘everything.’ What backs money is the entire gigantic apparatus of macrofinance. It is backed not just by ‘everything’ but by ‘everybody,’ or perhaps one should put it more precisely, by ‘everyone who is anyone.'” Or, if you are headed towards state theories of money, you can add and what really matters is that it is “backed by the one power that matters,” i.e. the people with coercive power.

That generally induces a sense of relaxation. “Ah, yes…”

But if this is a fair account of the emotional politics of money, it is also diagnostic. In the background of true believing cryptothought is some kind of model of societal collapse brought on by irresponsible politics, either democratic or authoritarian. This is a line of thought that goes back at least to the 18th-century theorists of modernity, Hume et al. The best (truly deep) book on this is by Mike Sonenscher, Before the Deluge.

Not for nothing, in theories of sovereign debt we speak of “original sin,” i.e. the ability of sovereigns to default without serious penalty. In the fear of fiat money lurks a fear of original sin. And in the modern, secularized world there lurks in that space the fear of the famous “empty place” or openness of “the political” as diagnosed by Lefort, Gauchet, and company.

At the global level, we are a very, very, very long way from Bitcoin et al. challenging the global hegemony of the dollar to the point at which one could talk about a broader systemic effect.

EM: We have interviewed Andres Arauz, the former Ecuadorian minister who also ran in the presidential elections last year. One of the salient points he made with regards to Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies in general is that they do undermine, in a way, the bargaining power of the IMF and the US as well as the dominance of payment systems like SWIFT (which are often used as a bargaining tool, as we have seen during the war between Russia and Ukraine). Is there, perhaps, a charitable reading to be made of crypto as unwittingly helping the anti-systemic forces, many of them on the left, even if the underlying crypto-assets are designed and promoted by ardent libertarians, mostly in the US?

AT: Presumably we would want to distinguish different types of anti-systemic effects and also ask what kinds of new systemic risks and new hierarchies of power might emerge in a world in which crypto was more prominent. The issuance of central bank digital currencies or the creation of alternatives to SWIFT may indeed be part of a sovereigntist strategy. They are an update of classic strategies of economic sovereignty for a digital age. At the global level, we are a very, very, very long way from Bitcoin et al. challenging the global hegemony of the dollar to the point at which one could talk about a broader systemic effect. And one should surely expect regulators to crack down hard, well before we reach that point. Meanwhile, various types of asset-backed crypto generate their own hierarchies and their own risks of financial instability and thus financial compulsion.

EM: Related to this, how do you assess El Salvador’s move to issue Volcano Bonds? We have heard quite a wide variety of opinions on it. If we were to once again be charitable, by what logic could we say that, say, Varoufakis’s flirtation with starting his own digital currency in Greece was a clever bargaining tactic in negotiating with the European Commission but Bukele’s flirtation with Bitcoin bonds is not? Would you condemn both as populist and irresponsible? What if Bukele’s stance does help to secure more favorable conditions from the IMF though?

AT: A digital central bank currency, or digital Treasury-backed currency is a totally different beast from a situation in which a small, vulnerable country hitches its bandwagon to a highly speculative and volatile vehicle for private speculation, which is what Bitcoin is at this point. Why does it make sense for El Salvador, given its desperate need for infrastructure, to borrow $1 billion, half of which will be invested in an asset (bitcoin) whose value to the dollar has fluctuated since the spring of 2020 by a factor of almost ten? Will you end up with $500 million, $5 billion, or nothing? Only a truly desperate situation would warrant such a gamble. Unsurprisingly, El Salvador’s outstanding dollar debt sold off hard on the news. So there is real risk of collateral damage here.

EM: It’s common to hear that the rise of crypto is a direct consequence of the global financial crisis of 2008, a subject on which you’ve written extensively. On the one hand, given the historically low or even negative interest rates, investing in Bitcoin or Ethereum does seem like a way to make some non-trivial returns in an economy that no longer works for retail investors. (I’m not saying I buy this argument, as whatever these investors are losing in bonds they can recuperate on the stock markets and via ETFs but this argument does get made a lot.) On the other hand, given the post-OWS and post-Tea Party atmosphere of distrust in the financial system, it’s logical that people would buy into the idea of trustless money, where all the political work is done by the blockchain. As such, the mainstream appeal of crypto is a useful barometer of distrust towards both central banks and Wall Street. Short of a vast crypto crash, do you think that there is a way back to those pre-2008 times, when the trust in both public and private institutions of finance ran a bit higher? Wouldn’t one say that the Covid-related bailouts – a form of escalating neo-feudal plunder, if Robert Brenner is to be believed – only reinforced this broader distrust and now there’s surely no way back? Could CBDCs do the job of restoring this public faith somewhat?

AT: I don’t disagree with that broad diagnosis. All sorts of morbid symptoms are appearing at this moment, hence the appeal of the famous Gramsci line. But we should see them for what they are and put them in context. They are morbid symptoms, confined to a small but very vocal minority, particularly vocal in the tech/social media space, so they grab a lot of attention. As to the more general explanatory framework, if you look at data for trust in the Fed, then the collapse in confidence actually happened not after 2008 but under Greenspan, after dot.com.

And in Europe, despite the nightmare of the Eurozone crisis in which the ECB was largely culpable, confidence in Eurozone institutions is fairly high. I discussed some of the more recent research on that issue in my newsletter (Chartbook #62). This shows remarkably high levels of confidence in the ECB across the Eurozone, and strikingly most of all in the hard currency Northern European countries that you might expect to be most tempted by anti-fiat tendencies. Standing even further back, I take issue with Brenner’s simplistic account of the 2020 crisis response. I laid out my alternative interpretation at length in Shutdown. But that debate is for another occasion.

EM: There are voices on the left who insist that the democratization of finance epitomized by the rise of Robinhood-like apps (and, to some extent, many crypto infrastructures and assets) is something that progressives should be exploiting rather than condemning. This ties, somewhat, to the long-running efforts to, say, have workers play a greater role in deciding how pension funds invest their money; have the citizens of Norway more actively shape the activities of the country’s sovereign wealth fund; etc. So one can envision that, instead of dumping all these new crypto riches into NFTs, progressive organizations can, in fact, form their own financial vehicles in order to support progressive causes and also, perhaps, ensure that there are other criteria – beyond just profitability – that are taken into account by the cabal that is the world’s leading credit agencies. Some intellectuals and academics – I’m thinking of Michel Feher and Robert Meister – have made such arguments in the past. Do you think this is a viable project, especially if one considers what is already going on in the ESG space and the “social turn” by the likes of BlackRock and Vanguard? What I find so intriguing about such proposals is that they don’t advocate philanthropy – so you make money through hedge funds and then redistribute through foundations, the way, say, Soros has done – but they actually want to make money through finance and then also use it for political battles that are enacted through finance itself. Any thoughts on this?

AT: In Shutdown I described the Robinhood bros as the people who in the spring of 2020 “connected up the dots.” Rather than waiting for radical monetary politics to deliver central bank accounts for every citizen and people’s QE, they took their stimulus checks and dumped them into the stock market and thus rode the same escalator as the better-off investors courtesy of the Fed. There is an argument for investing a larger share of pension funds in the stock market, precisely so as to secure some of those gains. The risk, of course, is that it becomes a privatization boondoggle for overpaid fund managers.

One solution is index funds. But this kind of public investment is precisely what the big Sovereign Wealth Funds do. One can even make a case for making such bets on a leveraged basis. You don’t have to wait for a fund to accumulate before you speculate. “Only suckers do that.” Borrow money on the strength of future flow of contributions and invest that. What you would need, of course, is a safety net, hedging, all the usual safeguards. But let’s be clear, the entire American university system – in which so many of the folks contributing to this debate earn their living – operates on this basis. What do people think sustains the luxurious grants and conditions in graduate school in the US? In the inner circle of elite schools, both public and private, it is, to a considerable degree, endowment income generated in precisely the manner you describe. It is a two-way relationship. Yale’s endowment is one of the most highly rated investors. They have access to the most exclusive circles of unconventional assets, private equity, etc. And if you believe Coindesk, Harvard, Yale, and Brown have all been buying crypto.

If you think that money as we know it is backed by nothing, why do you think Facebook is so interested? After all, what is Facebook “backed” by?”

EM: Do you think that the rise of crypto might, paradoxically, reinforce China’s standing on the world stage? It took the most drastic measures to regulate crypto currencies; it moved very fast to introduce its own state digital currency, the e-yuan. Previously, it moved very aggressively to regulate FinTech and digital payments. Sure, its economy has its own problems like Evergrande, but, overall, it seems to be taking steps to limits its exposure in the eventual crypto-collapse but also to free up its hands when it comes to public policy in the monetary realm: they don’t want to share their monetary sovereignty with Alibaba, let alone Bitcoin or Ethereum. Do you think this strategy would eventually be vindicated? And what do you think of central bank digital currencies in general, and of the Digital Euro in particular?

AT: Central bank digital currencies seem to me an entirely logical development of the fiat system for the digital era. In fact, I struggle to understand the difference between what is proposed with such fanfare and the systems we already have in place for all large transactions. Clearly, in China’s case the aim is for something truly transparent to the state and the regime. In their case, this is particularly dramatic, not only because the regime’s ambitions to control are so sweeping, but because their entire banking system as we know it today, the entire gigantic edifice, is only 25 years old. So, the fear that haunts the West, that digital currencies could render private banking institutions irrelevant, has a more dynamic, historical character in China. Perhaps commercial banking there will be a brief interlude. It seems that concern for the profits of the incumbent private banking system is one of the main reasons not to push forward rapidly in Europe and the US. The banks will threaten us with “stability concerns.” Those claims seem like something we should investigate critically. Perhaps digital central bank currencies are interesting precisely because they offer us a way to change the terms on the incumbent financial system, not as a private venture (as with crypto) but as a public enterprise.

EM: The US and Europe are not China and such drastic measures are not very feasible, at least not in the short-term. What do you think the regulatory priorities should be and how feasible are they to implement, at least in the US, where some of the senators charged with regulating the crypto-industry have been found to be active investors and traders in it themselves? As we could see from the confirmation hearings of Saule Omarova, both Democrats and Republicans get very itchy when it comes to anyone with a more adversarial position with regards to both crypto and Wall Street… So it’s hard to imagine Robert Hockett’s ideas around the Democratic Digital Dollar getting much traction in Congress…

AT: Indeed. Apart from passing legislation to prevent active trading by elected officials and Fed staff, the priority should be to ensure that crypto models like Tether do not generate serious run risks. They are supposedly asset-backed. They are, for all intents and purposes, a hybrid of banks and ungated funds, which themselves are too much like banks. They need to be regulated as actively and thoroughly as banks, more so given their limited track record. 2020 revealed once more how dangerous the risks in the shadow banking system continue to be.

EM: Do you think we are too quick to write off Big Tech – the likes of Facebook and Google and Amazon – when we think about the future of money? In theory, they do have far more resources, technological know-how, and already existing technological networks (e.g. WhatsApp) through which to conquer the consumer market. Facebook has had a rough start with Libra (now rechristened Diem) but it’s still very much alive. And the European Parliament even issued a report, back in 2019, saying that “synthetic central bank digital currencies” – a public-private partnership of sorts – whereby the likes of Facebook will get to run these officially-sanctioned stablecoins in exchange for access to the central bank reserves. Do you find this vision plausible, especially given that, when situated against crypto, Big Tech look like angels?

AT: Big Tech is an established, dynamic, rapidly growing global power. I agree that putting them in the same pot as insurgent, two-bit crypto makes no sense. But for the same reason, we should be intensely vigilant with regard to any project to extend the already immense grip of the likes of Facebook, Google, and Amazon. But I hardly need to lecture you of all people on that point.

Shoshana Zuboff’s concept of the “Big Other”, stripped of its ominous Big Brother connotations, is actually not a bad way of thinking about how money functions in general. One might ask indeed, “If you think that money as we know it is backed by nothing, why do you think Facebook is so interested? After all, what is Facebook ‘backed’ by?”

But, to allow Big Tech into this arena is a specularly high-stakes gamble. Their infrastructural power is immense and we are only beginning to come to terms with it. So too, of course, is that of macrofinance. When you talk about bringing those two together you are really talking about two tectonic plates rubbing up against each other. Right now it is hardly as though we can be confident that we have the technical, legal, economic, or political capacity to regulate either of them, let alone the two of them in some kind of synthesis.

The convergence may be hard to stop. We may have to allow it. But let us not rule out other options. And let us not fall into deterministic talk. Remember Larry Summers dismissing Raghuram Rajan as a “luddite” for expressing concern about financial instability. And then came 2008!

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But, writing this newsletter takes a lot of work. If you are enjoying it and would like to support the project, sign up for one of the subscription options here.

January 21, 2022

Ones and Tooze: Why Do People Still Care About Davos?

Season 1, Ep. 17

It’s been lampooned as a gathering of “the rich and the clueless.” U2 lead singer Bono referred to its attendees as “fat cats in the snow.” So what makes the World Economic Forum’s annual conference in Davos so closely watched? Co-host Adam Tooze has been there twice and would have traveled to Switzerland again this year had the confab not been relegated to online-only status thanks to Omicron. Instead, he talks to Cameron Abadi about what really happens in Davos and how the super rich differentiate themselves from the run-of-the-mill aristocrats there.

Also on the show: Part two of our lifecycle series, this one focusing on education.

Chartbook #73: Crisis Pictures (Krisenbilder) – mapping the polycrisis

Yes, I know it is relentless. That is also a feature of the polycrisis we are in. It comes from all sides and it just doesn’t stop.

How to get a handle on this situation?

In German there is a compound noun: Krisenbilder – Crisis Pictures. I am going to draw some Krisenbilder.

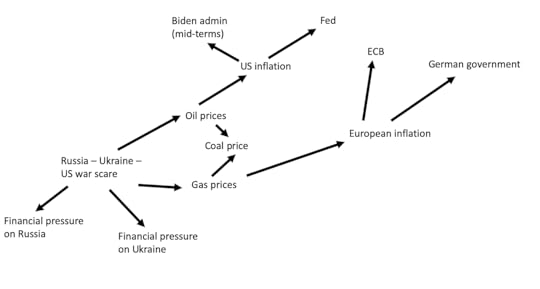

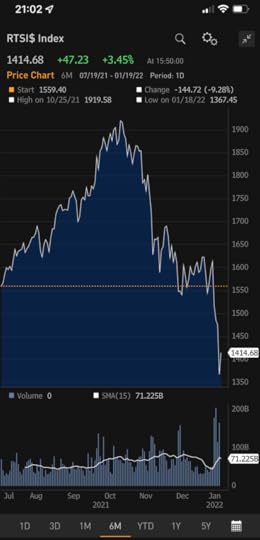

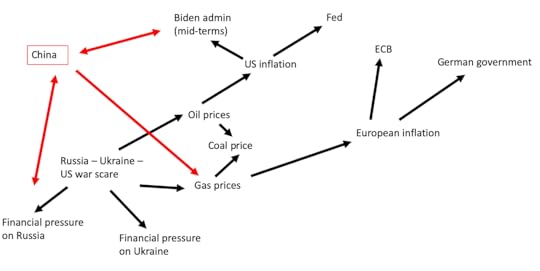

This one links the Russia-Ukraine-US war scare to financial pressure in Russia …

Source: Timothy Ash

and Ukraine where Credit Default Swaps (the cost of insuring government debt) are exploding…

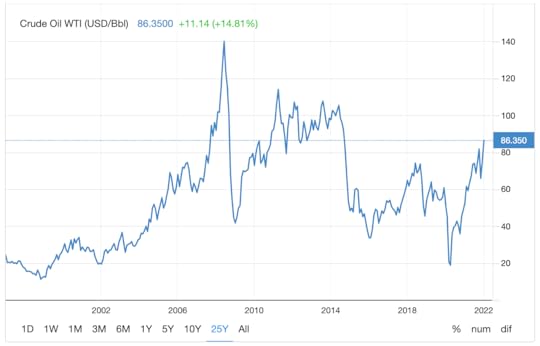

Could the West afford to sanction Russia? In 2014 US sanctions on Russia were carefully calibrated in light of the state of the oil market. How much more fragile is the situation today.

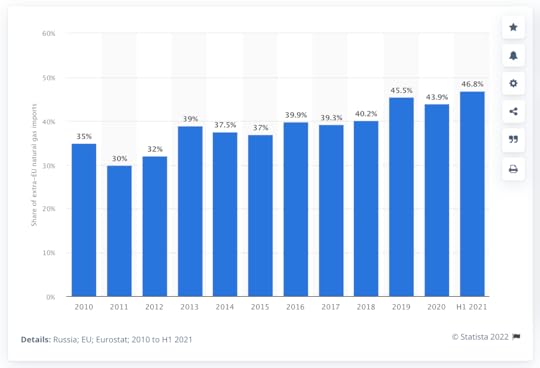

How vulnerable is the Biden administration given the inflation scare in the US and Europe. If there is one thing Europe does not need now, it is more pressure on gas prices. But Europe did nothing after 2014 to reduce its dependence on Russia for gas imports.

Everywhere you turn, these connections are manifesting themselves.

Framing the stand off between Russia and the West, is China.

Since the Ukraine crisis of 2014 Russia has developed a new and far closer relationship with Beijing. It will be a striking twist in Eurasian history if it is two crises in Ukraine (2013/4 and 2021/2) that drive Russia definitively into the arms of China.

Right now that same triangle – US-Russia-China – is manifesting itself in Europe in intense politicking around Lithuania!

After @noahbarkin reported that Berlin believed that Lithuania was an eager tool of US policy v. China (with eye to Russia) gmfus.org/news/watching-…

Now the well-connected @Dimi of the FT, reports that the US is using its diplomatic sway to soften Lithuanian stance!

File that under: “Things that make one go “Hmmmm…”

Certainly, China gains leverage as tension between the West and Russia mounts. At the same time it was China’s surging demand that triggered the explosive “pop” in global gas markets that has put so much pressure on governments in Europe and places them in Putin’s hands.

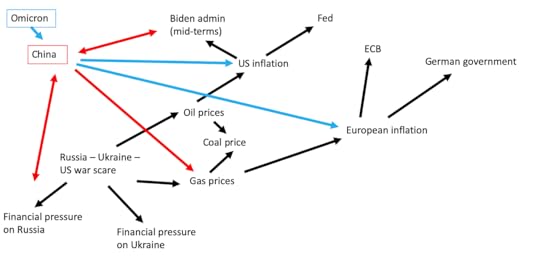

China also, however, poses another risk, by way of the unpredictable spread of Omicron. This could inflict further disruption on global supply chains transmitting a further supply-side shock and inflationary impulse directly to the US and Europe. This further expands our Krisenbild.

Little wonder perhaps that the US authorities were said yesterday to be closely following the unfolding Omicron threat in China. At least in this respect we appear to have learned the lessons of January and February 2020. What happens in China doesn’t stay in China!

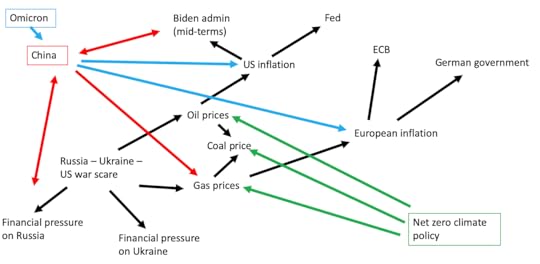

And, all of this, dizzyingly, is unfolding only weeks after the global climate conference in Glasgow produced unprecedented commitments to net zero – including a distinct shift in position from Russia – fanning the (over)excited talk of “greenflation”.

To be clear, I think we should regard many of these linkages with a fair degree of skepticism, notably the talk of greenflation. More on this in a future Chartbook. But these connections are “out there” in the conversation. As discourse they matter, whether we can quantify or measure their effects or not.

A map like this may be useful for taking stock and surveying the variety of linkages that are currently being invoked, the range of connections that are in play.

Many of the connections, indeed the war scare itself, hover between the actual and the hypothetical. It is the threat of an, as yet, hypothetical war that is causing all the commotion. But that commotion is very real. War scares are real.

The German philosopher-historian Reinhart Koselleck spoke of the gap in modernity between the space of experience and the “horizon of expectation”. Given our present mood, talk of a horizon of expectation feels like a rather pastoral image. What these Krisenbilder sketch is more like a mind map of our fears.

But, with Koselleck, let us hope that these fears do remain on the horizon.

Certainly, let us hope that we are not caught up by the shadows of the past that haunt this ominous interview with one of Russia’s most heavy-hitting conservatives.

Karaganov often speaks what Russia's most conservative foreign policy minds think (military but not only)

— Anton Barbashin (@ABarbashin) January 19, 2022

Few gems from his recent interview:

1/12

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But, writing the newsletter takes a lot of work. If you would like to support the project, sign up for one of the subscription options here.

January 20, 2022

After Biden’s first year, the US economy is surprisingly healthy. His prospects are not

At the 12-month mark, the obituaries for the Biden administration are being written. The polls are terrible. Biden’s marquee legislation is stalled. In recent weeks, even appeals by the president to the hallowed legacy of civil rights have failed to move the Democratic party’s holdouts in the Senate – Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema – thus blocking the passage of voting rights legislation. While the president invoked Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Manchin countered with the need to preserve the 232-year tradition of conservative stability in the Senate. Not for nothing, 2022 starts with talk about civil war.

It is a depressing picture. It is, however, worth reminding ourselves of where the nation was 12 months ago. As 2021 began, it was an open question whether the United States still had a functioning government. There was no orderly transition. The Trump administration simply gave up on Covid. As we now know, America’s senior soldiers were deeply concerned about the nuclear command chain. Then on 6 January there was the riot in the Capitol – now a morbid obsession of the Democrats – and the news from Georgia of the double Democrat win in the Senate runoff. It is on that thin basis that the Biden administration has since attempted to govern.

The restoration of normality that followed in the spring of 2021 was undeniably a relief, affirmed by the rapid rollout of vaccines. In foreign policy, Biden announced that the US was back. America rejoined the Paris climate treaty. Biden reasserted presidential control of the military command chain, insisting on his policy of withdrawal from Afghanistan, whatever the price. There were to be no distractions. All America’s resources were to be concerted around the competition with China. He was even open to a deal with Russia.

In March 2021, the passage of the $1.9tn American rescue plan was a big win. On top of the two other stimulus packages carried by the Democratic majority in 2020, the rescue plan has catapulted the US to the most rapid economic recovery on record. So large is the rebound that it has stretched global supply chains and engendered fears of a wage-price spiral. The inflation talk is now so deafening that it is worth reminding oneself that achieving a tight labour market was the point. As Biden remarked when employers complained about not being able to find workers: “Pay them more.” The problem for Biden, if there is one, is not that wages are increasing, but that they are not increasing rapidly enough. It is the erosion of real household purchasing power that makes inflation unpopular and means that Biden is not getting the credit you might expect given the surprisingly healthy state of the economy.

Read the full article at The Guardian

Chartbook #72: Team Transitory Roars Back

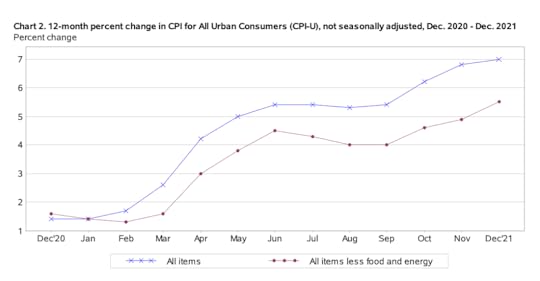

After the record series of “prints” for US CPI inflation in October, November and December 2021, there was a sense that the balance of policy argument had shifted. Inflation could no longer be dismissed as a temporary aberration. “Team transitory” and “team sectoral” were on the ropes.

From around the US economy, there was a rash of more or less amusing stories about shortages of essentials, like baking goods.

The Omicron wave got everyone baking again.

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) January 18, 2022

At the grocery store, baking categories of goods have seen the highest level of stockouts lately https://t.co/XdijFoiawA pic.twitter.com/03nwXVsIQm

And a BBQ-crisis in Texas.

Wtf I’m a hawk now https://t.co/RvLUpshgYo pic.twitter.com/Y1TMQ1a9t5

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) January 17, 2022

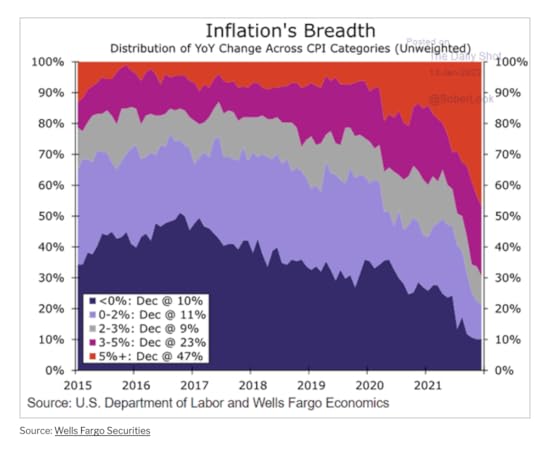

But the real source of concern was that inflation may no longer be confined to particular sectors. It may be becoming broad-based.

The share of CPI components rising by more than 5% has surged.

Source: Daily Shot

If the price rises are becoming a truly broad-based macroeconomic process embracing much, if not all, of the economy, it is time for the Fed to act. A monetary policy signal – a rapid ending of asset purchases and a move to raise rates – is essential to ensure that inflation expectations remain anchored and this post-COVID price adjustment does not become a general landslide. Policy Tensor has been as vigorous, as ever, in making the case for Fed action.

Policy Tensor

The Term-Structure of Inflation Expectations

Some interesting pushback from folks on econ twitter. People seem convinced that the current bout of inflation is broad-based. That result can hardly be argued with: But people seem to be less convinced that the current bout of inflation is not transitory but persistent. I am not a fan of the transitory vs permanent team sport. The issue is not inflation…Read more

Policy Tensor

For a less econometric, political economy approach to the inflation process, check out this excellent thread by Max Krahé of the Berlin think tank Dezernat Zukunft. He applies it to Europe, but his logic on how sectoral and distributional struggles might, or might not become a general inflation applies to the US as well.

THREAD: It's a distribution- not an inflation time bomb that's ticking.

— Max Krahé (@maxkrahe) January 19, 2022

Why? In Europe, inflation is sectorally concentrated, esp. in energy & food. It's bottleneck- (and savings-overhang-), not wage-driven. We're temporarily poorer than expected. (1/n)https://t.co/AtfquSNj9x

In Europe, as I argued in Chartbook #71, there is precious little evidence for generalized macroeconomic price pressure. But what about the US? Is the US different?

Clearly, the CPI data for the last few months have been exceptional, but do three rounds of price increases a “general inflation” make? In the last week we have seen a series of heavy-weight interventions resisting this mood-swing. Team transitory is not throwing in the towel. It is coming back strong.

For starters, it is worth reminding ourselves that a degree of modesty in making any firm predictions is called for. As this excellent thread by Dom White from December spells out, no one has a good model for our current situation.

I’ve spent a lot of this year thinking about inflation, so thought I’d write a little thread trying to summarize some of my thoughts. If you can’t be bothered to get to the end, the punchline is that there’s still a load we don't understand …

— Dom White (@DomWh1te) December 20, 2021

When the December CPI numbers were released, the Council of Economic Advisors issued this calming analysis.

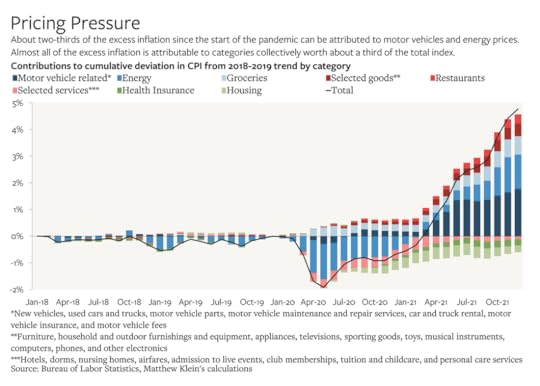

About half of the year-over-year headline inflation was due to energy and vehicle-related price increases. 3/ pic.twitter.com/UJ5TeBRQjS

— Council of Economic Advisers (@WhiteHouseCEA) January 12, 2022

Well, you might respond, Biden’s economists would say that, wouldn’t they. So let’s canvass some other well-informed people.

Joe Weisenthal at Bloomberg has been tracking the supply chain story as closely as anyone. He remains unconvinced that we are facing anything more than a transitional shock.

So what exactly is overheating? What’s “too hot?” The most plausible answer is that the speed with which we’ve returned to normal is extremely fast, and that’s taxing the system as a whole. This seems reasonable. It has been an extraordinary rapid bounce back, at least from the perspective of past downturns. And not only has the bounce back been very rapid, consumption patterns have changed amid the bounce back. As everyone knows by now, people are buying a lot more “stuff” relative to services, and as such the price of durable goods has shot up.

One takeaway from all this is that it may be too soon to bury the t-word, “transitory.” Sure, nobody uses the word anymore. Most people seem to be too embarrassed to even say it out loud. But there are still reasons to think that the big upward pressure we’ve seen in prices is related to the rapid journey back to trend and the shift in consumer demand. And it’s important to remember that the rapid journey back to trend is a good thing.

Matt Klein on his Overshoot Substack (Yes, it is pricey, but man is it good! Highly recommended) continued his forensic examination of the data.

Matthew C. Klein

The graph below is key. About two thirds of the deviation of CPI from pre-COVID trend can be attributed to just two categories – motor vehicles and energy prices. Almost all of the excess inflation is attributable to components collectively worth one third of the overall index.

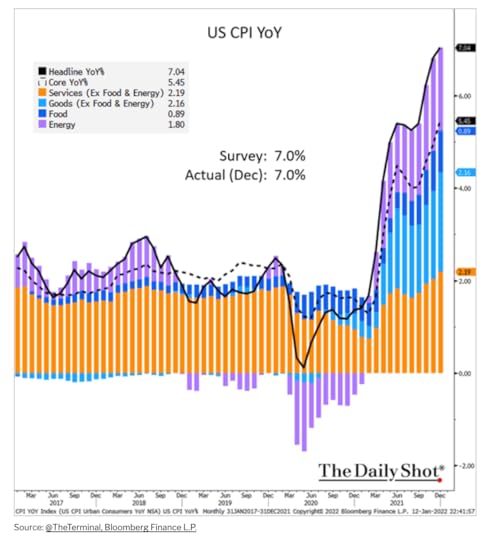

Crucially, as Martin Sandbu makes clear in his excellent recent article in the FT, prices in the service sector, which accounts for the bulk of CPI weighting, have shown little acceleration at all. Normally, inflation in the US service sector runs ahead of the overall inflation rate (there is less global competition). Normally, this is offset by deflation in the goods sector. Exceptionally, due to the COVID-rebound deflation in the goods sector has flipped to inflation, particularly in cars and energy.

The service sector rate of inflation (pertaining to by far the largest part of the economy) remains still largely unaffected by any broad-based inflation.

Source: Daily Shot

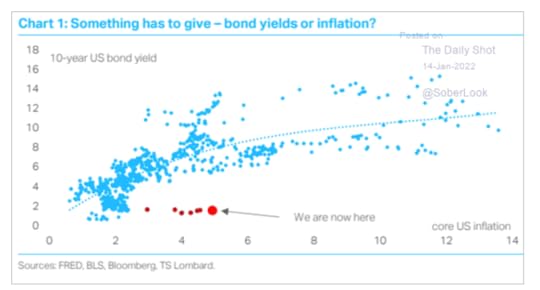

What about the markets? In recent weeks, yields on US Treasuries have twitched upwards. But we are a long, long, long way from the major capital allocators giving any signal that they fear sustained high rates of inflation. The trillion dollar question is what are the expectations on which this stability in the Treasury market is based?

Source: Daily Shot

The question of market expectations naturally points us towards the Fed and the expected interest rate hikes in 2022. But it also raises the question of the “fiscal theory of inflation”. Back in December, the Economist magazine devoted a long article to the idea. Remember back before 2020, in the “before times” when we used to argue that monetary policy was not enough. We needed fiscal policy to break out of secular stagnation, lowflation etc. Well, in 2020-2021 we got a fiscal policy jolt. And it has worked. We have inflation.

John Cochrane is rolling out a major new theory also called the fiscal theory in inflation, which he explains in relatively simple terms in this article. This is worth returning to, but as I read Cochrane, his theory expresses a pessimism not so much about our immediate prospects, as about the long-run consequences of running economic policy with a gigantic public balance sheet. How long will it be before bond holders realize that the public authorities cannot afford to raise rates, inflation expectations become unanchored and an avalanche of bond sales ensues?

This would seem to be a long-term theory of crisis, rather than an immediate theory of the price level. But this may be a superficial reading on my part.

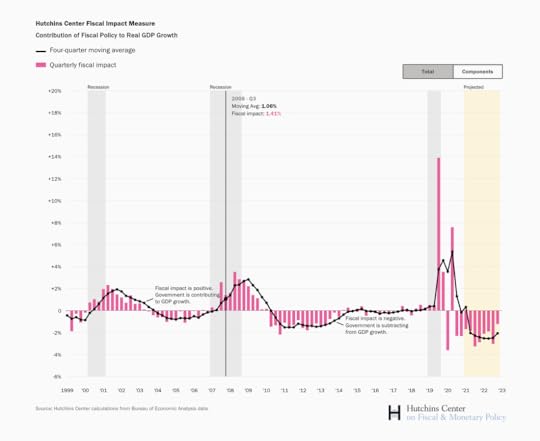

Certainly, in the short-run the outlook for fiscal policy is one more reason to be skeptical about the idea of an accelerating inflationary process. According to the outlook from the Hutchins Center all we have to look forward to is fiscal contraction.

Source: Data Hutchins Center

All things considered, the main reason to worry about inflation may be precisely that people are talking about it. Whatever its effects in the markets, in the political arena inflation talk is not neutral. Inflation tends to hurt the Democrats. Policy Tensor has put together a statistical model here. Inflation worry certainly seems to be hurting Biden and, heaven knows, he has enough to worry about. As I summarize them in this anniversary piece for the Guardian, his prospects are not looking good.

If one takes this argument seriously, then what the Biden administration needs is for the Fed to do the bare minimum necessary to anchor inflation expectations, calm public fears and the markets. Unfortunately, the calm in the markets is now based on pricing in four interest rate hikes. Let us hope that this is not more than the economy can bear.

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out to thousands of subscribers around the world for free. But it takes a lot of work. If you would like to contribute to the cause, sign up for one of the subscription options here.

January 18, 2022

Chartbook #71 The INFLATION-debate in Germany

Rising prices have unleashed an intense debate about inflation risk. Predictably this is particularly intense in Germany. The leadership trio at the helm of the ECB – Christine Lagarde, Isabel Schnabel and Philip Lane – are being tested. At the same time there is a new boss at the Bundesbank. And there is a new German government with an FDP-man (supposedly a conservative when it comes to fiscal policy) at the Finance Ministry. The Finance Ministry doesn’t set policy on inflation, but defining the terms of the inflation debate helps, at the same time, to set the terms for the debate on fiscal policy – more/less stimulus. This is also, inevitably, a war of position between different personalities and institutions in Germany’s increasingly diverse economic policy landscape.

The polite end of the conversation are interventions by accredited members of Germany’s official board of economic advisors, such as Volker Wieland, in the pages of the FAZ, asking for urgent ECB action on interest rates.

Wirtschaftsweiser: Wieland fordert von EZB Zinserhöhung schon 2022https://t.co/t5XRyEespB

— Gunther Schnabl (@GuntherSchnabl) January 17, 2022

Then there is Germany’s tabloid Fox-style Bild Zeitung (Circulation c. 7.8 million. By far the most influential daily news source in Germany).

*** Neues aus dem Populistenzirkus ***

— André Kühnlenz (@KeineWunder) January 17, 2022

Rote Ecke: Hr Doktor Krämer @DrJoergKraemer

Blaue Ecke: Fr Professor Doktor Schnabel @Isabel_Schnabel

Ratet mal, warum wer den Titel im Handle trägt? Alle Fachfragen & der verschwundene Diskussionsstil wurden eh am Wochenende geklärtpic.twitter.com/bT9M3xLmGG

In the corner of the inflation-hawks the stalwart chief economist of Commerzbank Dr Jörg Krämer and on the other side Isabel Schnabel of the ECB who is accused of disregarding the inflation threat. Schnabel has been regularly singled out for attack by the Bild Zeitung. “Your saving are in for it, when SHE (sic) is minding our money” (Wehe dem Sparschwein, wenn SIE über unser Geld wacht!) screamed one headline.

“This woman makes German savers tremble”. The relentless scare-mongering and the relentless emphasis of Dr Schnabel’s gender are typical of Bild coverage.

But banging the inflation drum is by no means confined to the populists. In September, Schnabel called out a large slice of the German media for their sensationalist reporting of the inflation numbers.

As Schnabel noted:

It is therefore important to offer a factual explanation for the recent price increases and an assessment of future risks, especially in Germany where many supposed experts and the media are again rousing people’s fears without explaining the reasons behind the price movements (Slide 5). Allusions are being made to conditions in the Weimar Republic. Comparisons are being drawn to the 1970s, when inflation in Germany was almost 8%. And there are warnings of a “meltdown” and a “runaway train” if interest rates remain low.

Schnabel has allies. Notably, Marcel Fratzscher of the DIW. In October he delivered this fantastic mega-thread on how not to think about rising inflation.

Die #Inflation von 4,1 % im September löst viel Empörung aus. Der Schuldige ist für manche in

— Marcel Fratzscher (@MFratzscher) October 2, 2021klar: es ist die #EZB, die die Inflation in die Höhe treibt und die #Sparer „enteignet“.

Der Alarmismus ist falsch, manipulativ und schädlich.

Ein Thread mit Zahlen und Fakten: pic.twitter.com/2eSDyV8Nsp

Another source of good sense is André Kühnlenz @KeineWunder who is an essential follow on the entire German-speaking world, Eurozone and more. Here he is, calling out TV and radio coverage of the inflation story.

In diesem Sinne, liebe Kollegen von @boerseARD @DLF @heutejournal @ZDFheute, schaut doch mal genauer hin, welche *Experten* da wirklich Eurem demokratischen Auftrag aus der Zivilgesellschaft nachkommen… Wär schon cool…

— André Kühnlenz (@KeineWunder) January 17, 202210/10https://t.co/kmVgPudqgW

In this spirit, kudos to Die Zeit for publishing this well-balanced exchange between Philippa Sigl-Glöckner and Hans-Werner Sinn. This doesn’t imply that I favor “two-siding” this story. But, in this particular instance, “balance” is commendable.

Besser als Kaffee um den Puls auf Touren zu bringen: Eine Diskussion mit @HansWernerSinn zu Inflation, Schulden u dem Arbeitsmarkt moderiert u verständlich zu Papier gebracht von @lisakatharina u @schieritz. Danke an Sie alle, das hat großen Spaß gemacht! https://t.co/PxI7R9e9YM

— Philippa Sigl-Glöckner (@PhilippaSigl) January 13, 2022

Somewhat surprisingly given the intensity of this fight, Schnabel actually helped to stoke the fires by taking up the question of “greenflation” in a recent speech. That led to a lot of exaggerated and hypothetical talk about how the energy transition was going to necessitate a more hawkish central bank stance. The energy transition is taking its sweet time. But, for largely unrelated reasons, gas prices have gone haywire. Putting two “and x” together it is easy to arrive wherever you fancy.

The following weekend, Schnabel took the pages of the Süddeutsche Zeitung to clarify her stance. The SZ is generally regarded as a liberal paper. The tone of the questions gives a pretty good idea of how tough it is being a central banker in Germany.

At the same time, Lagarde reassured the Handelsblatt that she was serious about inflation too.

As the excellent Sebastian Dullien points out, one of the real mysteries in the current moment is the fear of a wage-price spiral.

Yup. I am really wondering where some people get the idea of a price-wage spiral in Germany from. https://t.co/1pxKy9SOZr

— Sebastian Dullien (@SDullien) January 14, 2022

As @heimbergecon explains there is nothing in the wage data for the Eurozone to suggest such a spiral.

While many continue to worry about higher inflation in the €zone and predict a wage-price spiral/accelerating inflation…

— Philipp Heimberger (@heimbergecon) January 14, 2022

… the Eurozone wage data so far clearly reject this story, as wage growth remains muted.

Chart with the most recent data via @OliverRakau. pic.twitter.com/WqKwYB6h6D

For a wage-price spiral to be operative what you would need is pressure not just on wages, but on unit labour costs (wages adjusted for productivity) and even the Bundesbank does not actually fear that for 2022. On the contrary, the outlook for the growth of unit labour costs in 2022 is a miserable 0.2%!

Wichtig für Lohndruck auf die Inflation sind nicht die Arbeitnehmerentgelte/Tarifverdienste an sich, sondern die Lohnstückkosten (Risiken gibt es bei > 2%): Also um wieviel die Löhne stärker wachsen als das BIP… Für Deutschland sieht die @Bundesbank 0 Risiko 2022… #K_Notizen pic.twitter.com/ukBPZeTMOA

— André Kühnlenz (@KeineWunder) January 12, 2022

The real issue, as Marcel Fratzscher points out, is not so much inflation per se, but the distributional issue of how families on low incomes cope with a surge in the price of key consumer goods.

Die #Inflation in

— Marcel Fratzscher (@MFratzscher) January 7, 2022lag 2021 bei 3,1 % und sinkt wieder (0,2 % MoM im Dez). Das ist zu hoch,aber kein Grund zur Panik.

Die ungleiche #Verteilung ist das wirkliche Problem:steigende Mieten, Energie- und Lebensm.preise für Menschen mit geringen Einkommen. https://t.co/M2hB4FI6TN

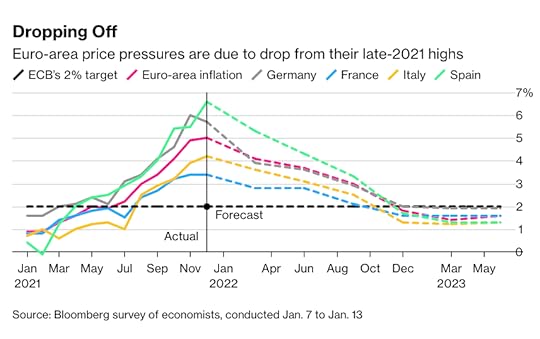

For Europe as a whole, the latest surveys of Eurozone economists suggest a rapid deceleration of inflation in the course of 2022. As Bloomberg reports: “The worst may over for firms and households feeling the pinch of higher prices in the euro area as inflation is fading from a record high.”

But every day the battle goes on. In this thread Fratzscher and Schnabl trade blows over the question of the symmetry of the ECB’s inflation target.

Ein widersprüchliches Argument von @WielandVolker: die #EZB solle Inflationsprognosen ignorieren und sich nur auf die #Inflation heute stützen,obwohl sie diese heute fast gar nicht, sondern nur für die nächsten 1-3 Jahre beeinflussen kann.

— Marcel Fratzscher (@MFratzscher) January 17, 2022

So würde die EZB der Wirtschaft schaden. https://t.co/jDvX1UpX0R

It is going to take time for a lot of German commentary to assimilate the idea that the target really is 2 percent not LESS than 2 percent. Watch this space.

*****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out to thousands of subscribers around the world for free. But it takes a lot of work. If you would like to contribute to the cause, sign up for one of the subscription options here.

January 16, 2022

Chartbook #70 Draghi for President?

Last week I did a new piece on the current political situation in Italy for Foreign Policy. Will Mario Draghi make a bid to take the office of Italian President? If so what would be the implications for Italy and for Europe?

It is an update to the piece I did for FP a year ago, comparing Yellen and Draghi’s roles as managers of the modern economy.

There is always a good reason to come back to Italy. The most important one, that should never go unmentioned, is that Italy is lovely. Plus, thanks to Dana I get to spend time there. The more academic and political reason is that Italy is pivotal to the future of the Eurozone.

Italy’s $2.9 trillion in debts are the critical issue. How Italy and Europe manage that pile of obligations, raises important questions in the relationship between politics and economics in Europe and in capitalist democracies in general.

Since the late 19th century Italy has been one of the laboratories for working out the tense relationship between capitalism and democracy. Not for nothing it has generated a fascinating tradition of thinking about political theory, jurisprudence and political economy. Italy was an important part of the narrative of the crisis of liberalism in the early 20th century that I developed in my book Deluge. The collapse of liberal crisis-management into fascism in 1922 should haunt us all. This year, as my colleague Angelo Caglioti recently reminded me, is the centenary of Mussolini’s March on Rome.

In the wake of the disastrous world war, after two decades of rapid postwar growth, from the late 1960s to 1992 Italy underwent a convulsive upheaval in its political economy, the echoes of which are still with us today. The senior figures on the current Italian political scene – most notably Mario Draghi, President Sergio Mattarella and Silvio Berlusconi – are veterans of that era. If in the US, economic policy discourse still could be said to revolve around the consequences of the Volcker shock of 1979, in Italy politics still refers to the crisis of 1992. In that extraordinary year a corruption crisis swept away much of the old political class, a financial crisis rocked the Italian state, and the centrist elite (including Draghi and Mattarella) committed itself to tying Italy to the Franco-German vision of the EU organized around a common currency.

I don’t, in this issue of the newsletter, want to put economic analysis at the center. But we would not be having this conversation if Italy’s growth had met the expectations of the centrists who made their wager on the euro from the 1990s onwards. Instead, and it cannot be repeated too often, Italy’s GDP per capita has stagnated in a dramatic fashion.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, governing a society experiencing this kind of stagnation under democratic conditions is not easy. It leaves Italians, in public and private, looking for answers and ways out of the impasse.

How much growth does Italy really need? I don’t want to engage in the degrowth debate here. But Italy is also interesting from that aspect. By most reasonable criteria, despite this stagnation in gdp per capita, the standard of living in Italy for a large majority of the population is very attractive, enviable indeed. Behind a rawlsian veil of ignorance, would you pick a “success story” like the United States over Italy? But Italians compare themselves not with the US but with Germany and France. They combine the benefits of a welfare state and functioning community life with much higher growth. The sense of being left behind by others is painful. Italy’s corporations have lost ground in the global competitive race. And comparison with others aside, it is obvious that Italy could do so much better. There are very real deficits of an institutional kind, in technical modernization, not to mention the future problems of the climate, energy transition etc. What Italy needs is not brute-force growth at any price, but faster, “smart” growth, reform of institutions to improve everyday life, above all in the legal system and state administration, and a major investment in its education system, which currently fails far too many young Italians.

If Italy cannot achieve an acceleration in growth, what it faces is relative decline, bitter zero-sum domestic struggles over a fixed cake, the stunting of the life chances of entire cohorts of young people and, in the event that financial markets start to sell off Italy’s government deb, the very real possibility of an acute financial crisis. The question of Italian spreads relative to Bunds is already back on the European agenda.

This isn’t a matter of “economic laws” or “financial gravity”. If Italy had a sovereign national central bank, or if the ECB had a different mandate there would be little immediate reason for panic. Even with the current monetary constitution, the arrangement can be managed, if Rome acts and talks in a cooperative fashion, if there is a bit of creativity in the legal department of the ECB, if the other national governments play along and if Germany’s Constitutional Court bites its tongue. But that is a lot of “ifs” and $2.9 trillion is a lot of debt.

All this means that Italian politics demands our attention and it rewards that attention with a rich and fascinating debate (as thanks to google translate one can glimpse even without Italian).

How can Italy be steered through the rapids and set on a more positive course of development? Since this is a hard task for elected politicians, five times in recent decades the job of Prime Minister has been handed to a non-parliamentary figure.

The most recent parachutist is Mario Draghi, recently retired from the ECB. He took office in January 2021 to oversee the spending of the NextGen EU package. This allocates over 200 billion Euro to Italy in grants and credits. This, if you like, is Europe’s gamble on using investment to accelerate Italian growth.

After one year, the question has arisen of whether Mario Draghi should remain as Prime Minister for a limited term that expires in 2023 at the latest, or gamble on his elevation to the Presidency, which would keep him in power for seven more years. The selection process begins on January 24. I go into the political calculations in the Foreign Policy piece. For a timely review of the constitutional issues, see Carlo Fusaro’s piece here.

Those who favor a move by Draghi to the Presidency do so either on optimistic grounds (missions accomplished as PM) or, more commonly, on the pessimistic grounds that Italy needs a powerful, authoritative check on its disorderly and populist parliament. That is the scenario that I want to explore further here.

The idea is that if Draghi were made President, in the event of a right-wing populist electoral breakthrough, he would have the authority to resist a government that embarked on an aggressive nationalist course that put Italy’s euro membership in doubt, thus risking a devastating sovereign debt crisis that through its entanglement with the Italian banking system would spill over into a banking crisis. For Europe this doom-loop is ominous. An Italian crisis was the nightmare that hung over Europe during the eurozone crisis of 2010-2012. Unlike Greece, Italy is both too big to fail and too big to bail. “Whatever it takes”, it must not be allowed to enter crisis.

Given the powers provided to the Italian President by the postwar constitution, Draghi could curb a dangerous government in various ways. He could veto legislation or particularly dangerous ministerial appointments. He can maneuver with the government’s enemies in parliament and, in the last instance, dismiss the Prime Minister and call new elections. None of this is science-fiction. These are the kind of tools that were deployed against Berlusconi in 2011 by then President Napolitano and more recently and relevantly by Mattarella against 5Star and the Northern League after their election victory in 2018. In particular, Mattarella intervened to veto the nomination of the euroskeptic economist Paolo Savona as Minister for the Economy by the League. When that stalled negotiations, Mattarella proposed the economist Carlo Cottarelli, ex of the IMF, as a safe pair of hands. Instead, the 5star came up with Conte, their own safe pair of hands. In 2019 Conte would form the pivot around which the government was reshuffled, the Lega bounced itself out and the “center left” DP was brought back into power. The DP and 5Star provide the mainstay of Draghi’s support today.

In 2018 Dana and I were in Italy and I did a blogpost on the events in real time. Blast from the past!

How should one interpret this Presidential intervention in 2018 and what implications might it have for a future Draghi Presidency?

In researching the latest article for FP I was excited to (re)discover the very interesting constitutional theory debates that unfolded in 2018 on the pages of the indispensable Verfassungsblog – some in German but much in English and it is really great – around the Presidential intervention and what it meant. It is worth emphasizing that the 2018 situation was dramatic. Bond markets were seriously worried. We are very far from that situation today. But 2018 is the closest thing we have to an experiment of the Draghi scenario envisioned for the future.

Was President Mattarella’s intervention legal and legitimate? What does it mean for European constitutionalism? How might one imagine this spinning forward in 2022 and beyond with Draghi as president?

The debate in 2018 was fierce. The leader of the Five Star Movement, called for President Mattarella to be impeached under Article 90 of the Italian Constitution, for «high treason or violation of the Constitution. Clearly, if you engage in this kind of heavy-duty intervention you have to have a politician’s thick skin. There isn’t much in Draghi’s track record to tell us, one way or the other, whether that is part of his character. So far, the applause has been so universal that he has hardly been tested.

More substantively the critics alleged that Mattarella’s veto on Savona was a classic case of European financial imperatives curbing national democratic politics. In a phrase coined by the German constitutional judge and theorist Dieter Grimm, it was a case of over-constitutionalization. Marco Dani and Agustin José Menendez argued that

“this episode is revealing of the democratic limits of the European constitutional architecture and institutional culture. Following Dieter Grimm, we claim that the events here analysed reveal the extent to which the EU legal framework is overconstitutionalised and the democratic costs and risks inherent in this legal and political order.”

In effect Mattarella was repressing debate in the name of unspoken constitutional principles that Italians could have any government they wanted except one that challenged the imperatives of eurozone membership.

As Dieter Grimm had observed about European law,

as interpreted by the European Court of Justice and, we would add, as practiced in the context of the European economic government, ties with the golden fetters of the euro the hands of national governments, rendering hopeless the task of removing the obstacles to the realization of substantive equality, as required by the Italian (and other) constitutions. It seems to us that Mattarella’s decision only starts to make sense if one adds a fundamental piece to the constitutional equation, namely a form of “convention” (functionally equivalent to a constitutional convention) according to which political parties or coalitions that are critical of the existing economic and monetary arrangements within the Eurozone cannot get into government. Or, more accurately, they are entitled to govern in a tamed form … Such a convention could be said to be a renovated form of “pactum ad excludendum”, only this time it would not be the communists, but those daring to be critical of European economic govermment arrangements that would have to be prevented from holding power.

This is a powerful critique, but it did not go unanswered. The defenders of the President argued that he was fully within his rights. The Italian constitution provides for the President to be an active force, not merely a tool of the Prime Ministers will. The constitution always foresaw precisely such action. Furthermore, one should not fall too easily for the rhetoric of popular or national sovereignty as opposed to elite-European rule. As Massimo Fichera commented Italy was playing out a (fictional dialectics):

“The people” suggest a simple, quick way out of complexity. “The elite”, instead, appear aloof and untrustworthy. Democracy, according to this dialectics, can only be protected by pleasing the former – never mind that “the people” is often a smokescreen, hiding concrete plans and targets identified by concrete individuals.

In 2018 the concrete individuals enacting the drama were all too evident, with Matteo Salvini of the League being seen as the main actor in the drama. And this was the nub of Mattarella’s action. As Diletta Tega and Michele Massa argued in their defense of Mattarella, a key defense of the President’s position was that the appointment of an openly euroskeptic government would precipitate a crisis that would forestall a serious debate about Italy’s European options.

participation in the Euro and the EU are fundamental choices and they must be given open and serious consideration, whereas they have not been at the forefront of the Italian political elections of March 2018.

As President Mattarella stated in justifying his decision to block Savona,

“The decision of joining the Euro is of key importance for the prospects of our Country and of our youth: if we want to discuss it, we have to do so openly and after a serious in-depth analysis. Also because it is an issue that was not brought up during our recent election campaign”.

According to his defenders, Mattarella did not deny the possibility of exiting the eurozone or flaunting its formal rules and the cooperative tissue that holds it together. But it was important to be clear about the gravity of the choice. The pressures generated by eurozone membership are due to deep and real entanglements. Nor is Italy’s entanglement a matter of fate. It cannot be blamed on anonymous forces like globalization. It was chosen. Now the logic of European integration is working itself out. As Fichera argued in a second blog post this has always had a compulsive logic based around the threat of crisis and the promise of security.

the reasons behind Mattarella’s decision are deeply linked with the “security of the European project”, a rationale which has been a constant feature of European integration. …. the President’s intervention is in line with the constant trend of the material constitution towards an ever-stronger role of the Head of State. ….

Casting off, or promising to cast off from this deeply entrenched security project is conceivable, but it will come at a huge costs and reverse a long-standing development of the practices of government. There is no denying, Fichera insists, the process that is underway. The critics of Mattarella’s choice

… correctly emphasise(s) the worrying tension between freedom and coercion, which can be detected in EU constitutional law. Although the Italian crisis was a matter of domestic constitutional law, it inevitably affects the EU legal and political framework, because of the commitment towards the European project, which is enshrined in the Italian Constitution (Articles 11 and 117). As recently argued by some Italian scholars when commenting on the appointment of the Monti government (above all Antonio Ruggeri), the persistent state of crisis might have modified some of the traditional theoretical categories employed to describe the “constitutional State”, to the extent that governments would now have to seek not only a formal vote of confidence from Parliament, but also an informal vote from the EU and the financial markets.

The tension between freedom and coercion is here particularly visible and is expressed by what I (Fichera) call the “security of the European project”, a meta-constitutional rationale which has been historically developing through discursive practices detectable both at the national and the EU level. As EU integration reaches a more advanced stage, its conflictual elements, which have been previously concealed, come to the surface- and, together with them, all the contradictions that affect the EU liberal model. Security is thus both the presupposition of, and a threat to, the project of European integration and such feature can be observed not only as regards the financial and economic crisis, but also in relation to the refugee crisis, the constitutional identity crisis, the rule of law crisis and Brexit.

Fichera concluded by demanding more debate.

Crisis and security are intertwined and mutually reinforced concepts. However, when crisis turns into a permanent condition and security becomes self-referential, the premises and foundations of a polity are themselves questioned. To be sure, precisely the contradictions and conflicts are an inherent feature of constitutionalism. They have been ignored for too long. It is now time to address them through an open and public debate, keeping in mind the risk of “over-constitutionalisation” both at the EU and at the domestic level.

But, where would that debate go. What follows if we “address” the tensions and contradictions and what implications might this have for a new era under a Draghi Presidency?

I take the drift of the apologists for Mattarella’s intervention to be one of realism. Let us recognize the scale and implication of our entanglement, including its compelling aspects. Let us not indulge in sovereigntist illusions. If you want to have a debate about leaving the euro, do so openly and face the full consequences. You will almost certainly conclude, as Syriza did that the risks are too high. Indeed, you may find that open debate itself is expensive. The markets don’t appreciate it. But that does not imply passive acceptance of the status quo. Certainly not after the shock of 2020.

On Draghi’s watch a raft of new proposals are already emerging as to modifications of the Stability and Growth Pact. Draghi has struck up a relationship with Macron to push for a fiscal settlement that enables investment to go ahead. It remains to be seen whether the Germans will bite. Rather than digging into technical details I want to continue to follow the path of legal theory that was opened up in 2018.

Aside from the indignation aroused by Mattarella’s intervention in 2018, what is the level at which we should appropriately analyse the process of political construction that is going on in Europe and playing out at the national level? In the LRB recently Perry Anderson made Luuk van Middelaar’s work into the anchor for a gigantic review of the European scene. For Middelaar finding a realistic language and conceptual basis for analysing Europe is the central challenge and this is presumably also his appeal to Anderson. There is nothing Anderson appreciates more than a bracing whiff of realism.

In the debate about the Italian crisis in 2018 one of the key moves made by Fichera is to argue that we should not get bogged down – for or against – in matters of textual interpretation of the Italian constitution. What needs to be recognized is the de facto development of what he calls the “material constitution”. He doesnt elaborate on his meaning, focusing instead on the rather ethereal meta-discursive frame of security. For a somewhat more substantial discussion of the material constitution, one can turn to Michael A. Wilkinson and Macro Goldoni. See also their Modern Law Review paper.

These are very rich interventions with a fascinating discussion of two interwar theorists of the law and the state who should be much better known. Hermann Heller and Constantino Mortati. But it is their analytical framework I want to focus on here.

What is the material context of constitutional order? The purpose of this paper is to offer an answer to that question by sketching a theory of the material constitution. Distinguishing it from related approaches, in particular sociological constitutionalism, Marxist constitutionalism, and political jurisprudence, the paper outlines the basic elements of the material constitution, specifying its four ordering factors. These are political unity, the dominant form of which remains the modern nation-state; a set of institutions, including but not limited to formal governmental branches such as courts, parliaments, executives, administrations; a network of social relations, including class interests and social movements, and a set of fundamental political objectives (or teloi). These factors provide the material substance and internal dynamic of the process of constitutional ordering. They are not external to the constitution but are a feature of juristic knowledge, standing in internal relation and tension with the formal constitution. Because these ordering factors are multiple, and in conflict with one another, there is no single determining factor of constitutional development. Neither is order as such guaranteed. The conflict that characterizes the modern human condition might but need not be internalised by the process of constitutional ordering. The theory of the material constitution offers an account of the basic elements of this process as well as its internal dynamic.

Abstract at this sounds – and this is the abstract of the paper – the idea of defining the “material constitution” of Italy and its relationship with Europe in terms of these four distinct dimensions – the grounds of political unity, institutions, social relations and the common purpose – is, in fact, extremely useful.

As for the grounds of political unity, you could say that Europe-Italy is in something of a counterflow. On the one hand in the wake of COVID, the notion of a community of fate at the European level is stronger than ever before. This is a phrase that Middelaar has picked up from the German usage. On the other hand in Italy it is also worth stressing that the particular parties that monopolize the integralist language of unity, are the far right. In particular Meloni’s post-fascist Fratelli d’Italia are now a real threat. Unity is a poisoned chalice.

Crisis management in 2020-2021 involved clear institutional development and it is for that reason that Draghi matters. Next Gen EU is a huge institutional step forward. In a classic institutionalist mode, Italy and France have announced their intention to insist on it as a precedent for further action. No less significant is the institutional autonomy again displayed by the ECB in responding to the COVID crisis and the ongoing recovery process. This is where Draghi is pivotal, as a representative of Italy and key institutional player. The independent reality of these institutional structures is not reducible to the sheer quantity of resources they can mobilize. In the worst case scenario of an escalating debt crisis, institutional and legal issues will come back to the fore with a vengeance.