Adam Tooze's Blog, page 23

March 17, 2022

What happens when a major economy can’t pay its debts in dollars? Russia is about to show us

As of Wednesday Russia has been scheduled to pay investors holding two dollar-denominated government bonds $117m in interest payments. It will likely make the payments, but probably in roubles rather than dollars. Some of Russia’s debt contracts permit such an arrangement; the two bonds in question do not. Russia has a grace period of 30 days within which to make payments in the normal fashion. If it fails to do so, it is likely to be declared in default by its creditor.

Sovereign defaults send shockwaves through the global financial system. They signal that a debtor at the very apex of the monetary system – a government – is either unwilling or unable to meet its obligations. Since, in a modern monetary system, government debt is generally treated as the ultimate safe asset, this is a shock that goes beyond the arena of high finance. Russian defaults have rocked the global financial system twice in modern history. In 1917, the Bolsheviks repudiated the debts of the Tsarist empire, souring relations with Russia’s former allies, most notably France, for decades to come. In 1998, in the financial crisis that defined Vladimir Putin’s rise to power, Russia defaulted on its domestic debt and some Soviet-era foreign debt. The repercussions were significant enough to bring about the meltdown of the LTCM hedge fund, the world’s biggest, in New York.

The current impending default is nothing like either of those occasions. Only a few short months ago Russia was a top-rated sovereign debtor. It had only $38bn in foreign currency debt outstanding, of which only $20bn was owned by foreign investors – a tiny amount for a trillion-dollar economy. The payment that is due now, $117m, is a small fraction of what Russia continues to earn every day for its oil and gas exports. For gas alone, Russia was a fortnight ago earning more than $700m a day.

Russia will pay in its local currency not because it is unable to find $117m, or because it has unilaterally decided that these debts are odious and should not be serviced. It is not paying its foreign creditors because it is locked in an asymmetrical proxy war with the west, a struggle in which the latter has chosen to weaponise the financial system.

Read the full article at The Guardian

Chartbook #101 Odious Claims – on Russia’s bonds

So, Russia is not defaulting after all?

As of 20 minutes ago the news is that JPMorgan processed interest payments from the Russian government. Acting as Russia’s correspondent bank, JP Morgan will pass the $117 million in coupon payments to Citigroup, who as the payment agent will distribute the money to investors.

The US Treasury signed off on the payment as not violating sanctions.

On the news, the price of a Russian dollar bond maturing in 2043 surged to 47 cents on the dollar, versus 20 cents a week ago.

47 cents on the dollar is hardly bad considering that we are perched on the edge of World War III.

But is this time to rejoice? Surely not.

If you invest in Russia to open hamburger franchises or Ikea’s stores, or to build cars, you are hoping to profit by selling daily necessities to ordinary Russian consumers, pretty much as you would anywhere else.

If you invest in Russian government debt what are you hoping to profit from?

As I argue in a piece that appeared in the Guardian earlier today, you are investing in Putin’s regime, warts and all.

As Tracy Alloway pointed out in a recent piece on Bloomberg trailing an Odd Lots conversation with Mitu Gulati, law professor at University of Virginia, the prospectus for Russian debt issued since Crimea are an itemized list of Putin’s conflicts with the West. As Gulati remarks some of the bonds seem structured so as to have clauses “in them that anticipates Russia misbehaving and sanctions being increased. It’s as if the investors are giving Putin insurance for bad stuff.”

You can read the details for two loans issued in 2020, here.

Seven pages later the section on sanctions concludes:

If you took up this offer of EUR 750,000,000 at 1.125 per cent due in 2027 or EUR 1,250,000,000 at 1.850 per cent due in 2032, you were along for the ride.

Not all the bonds have these clauses. The ones in question in recent days do no have an option for Russia to pay in rouble.

In the event of a default the FT speculated that some creditors

may actually want to quickly vote to demand immediate repayment and get court judgments from US and UK judges that allow them to try to seize overseas Russian assets, to ratchet up pressure on Moscow.

That is what really triggered my Guardian article.

Imagine a situation in which Western interests who have invested in Putin’s regime have priority in claims against Russian assets relative to other potential claimants, for instance Ukrainian victims of Putin’s aggression. Why? Because the Western interests were actual investors and thus had legal claims! It would be a staggeringly perverse situation.

Ukrainians would have to survive Putin’s onslaught, fight him to a standstill, and then go through the arduous process of peace negotiations and a reparations settlement, a hugely unlikely contingency.

Russia’s own citizens would have to brave political repression to hold anyone to account for the losses they are suffering.

Foreign direct investors in Russia are expected to simply write down their stakes.

But those who have invested directly in Putin’s regime, the foreign bond holders, may, by way of Western courts, have recourse against Russian public assets.

I’m no expert in international law like Professor Gulati. I may have the wrong end of the stick. But if this is broadly speaking correct, it is surely an intolerably perverse situation.

And it poses the question: should the fact that the $117 million in interest are currently flowing to Western investors be a cause for celebration or scandal?

Would it not be appropriate for those proceeds to be allocated to a common fund to compensate the victims of Putin’s aggression?

And should legislation not be drafted that would ensure that it is not bondholders who have the first claim on Russian assets overseas? Where this matters most is in the jurisdictions of England and New York, under whose law most international debts seem to fall.

March 16, 2022

Chartbook #100: Must central banks become lenders of last resort for commodity markets?

On March 8 as the global market for Nickel seized up and commodity markets spasmed, the European Federation of Energy Traders, a leading industry group, called on central banks to provide liquidity to support vital commodity markets.

The 4-page letter from lobby group the European Federation of Energy Traders pleading emergency liquidity support in full (with my own highlights).

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) March 16, 2022

EFET represents top trading houses, oil companies and utilities (think the likes of Vitol, BP, Trafigura, Uniper, Engie…) #OOTT pic.twitter.com/cVxzlqrJrO

Clearly the Ukraine crisis is a political and geopolitical event of the first order but in recent weeks many of us have been asking, how it might impact the global financial system. Does the letter by the commodity traders sound an important alarm?

At first it seems counterintuitive to imagine that markets with surging prices could be a source of financial distress. The more obvious line to pursue is the one suggested by a quip in the FT’s lex column.

Financial warfare creates collateral damage — and damage to collateral.

Robert Armstrong, for instance, in the excellent Unhedged newsletter explored the potential impact of sanctions on the finances of Russian oligarchs.

Following Zoltan Pozsar’s lead I did Chartbook #89 on Russia sanctions and the global dollar system.

Chartbook

Chartbook #89 Russia’s financial meltdown and the global dollar system. The Western sanctions on the Russian financial system announced over the weekend are doing their work on Monday. As far as Russia is concerned, financial markets are around the world have become a legal battlefield…

It is also clearly the case that the Ukraine crisis sharpens the dilemmas facing central banks around the world. Balancing inflation risk has become far more difficult. More on this in a future Chartbook.

But what has become clear in recent weeks is that key market-makers in commodity markets are struggling to cope financially with the huge surge in prices and the ensuing volatility.

Over a 48-hour period the price of Nickel soared by 250 percent. The entire Bloomberg Commodity Spot index leapt 13% in a week — the largest one-week price increase in 60 years. If you were on the wrong side of those price movement you were in serious trouble. Little wonder, perhaps, that hedging the risks became very expensive.

The scale of the stress becomes more apparent when one appreciates that global commodity markets involve an annual volume of at least 700 billion dollars in buying and selling, plus trillions in derivatives piled on those trades.

At the most simple level the price of buying a typical oil cargo of 2 million barrels surged from $140 million to $280 million. That involves raising more money in funding.

Since its earliest beginnings international commodity trade has been interwoven with finance. And commodity markets are also one of the places where derivatives were first put to use. If you take a long position on oil – spending $ 280 million on a shipment – what you want to hedge against is the possibility that its price might fall before you can deliver it to market. Those derivatives contracts have to be paid for. The trading house will generally only pony up a fraction of the price of the derivative, borrowing the rest from a bank or another source of funding. The cost of the derivative insurance will then be factored into the price that the trading house looks to sell for when it offloads the shipment of oil, nickel, gas ec.

Derivative contracts typically stipulate that if prices fall or rise beyond a certain point, implying a loss for the trading house that took out the hedge, the trading house must provide more of their own money to back the deal. Otherwise, the lender must fear that the borrower will simply walk away from the contract. That request for more cash in a leveraged deal is one of the most feared events in financial markets. It is known as a margin call.

That is what has been roiling commodity markets in recent weeks.

Take for instance the gas market as described by the FT.

Big commodity traders use derivatives to hedge contracts against price swings and lock-in margins. This typically involves selling futures contracts in Gunvor’s case linked to TTF, Europe’s wholesale gas price. As gas prices in Europe and Asia have soared, the losses on these contracts have increased, requiring Gunvor and other traders to make margin payments to brokers and exchanges. These losses from profitable positions will be offset once the commodities are sold, but in the intervening period margin calls can place strain on commodity traders, which are dependent on short-term credit lines from banks to fund their activities. “This cash flow mismatch can cause major liquidity problems,” said Craig Pirrong, a finance professor at the University of Houston. “And banks, for various reasons . . . may not be willing to extend credit sufficient to meet these liquidity needs …”

Peabody Energy, the world’s largest private coal producer, provides another example also from the FT. Despite surging coal prices it has been making a loss on its derivative hedges.

The contract agreed last year locked Peabody into a sales price of $84 per metric tonne until mid-2023 for a fraction of its seaborne thermal coal production in Australia. Soaring prices now means that it has been hit with a margin call of more than $500mn. In response, it has turned to Goldman Sachs which has extended a $150mn credit facility to help bolster its liquidity at a juicy interest rate of 10 per cent. That move is controversial, given Goldman’s previously announced aversion to coal companies. … Peabody’s hedge was mercifully limited to just about a tenth of its thermal seaborne production. As the company sells unhedged coal at high spot prices over time, it will generate the resources to both fund any impending margin calls and pay down the Goldman loan. Peabody, like all other commodity producers, has been caught off guard by the rally in prices. Its ordeal is a reminder that companies favour predictability over volatility.

Peabody’s hedge was for a limited volume of coal and as a producer it has a massive structural long position from which it currently profits. It will earn its losses back and more. Large trading houses are not in such a comfortable position. They trade billions of dollars per week and have not natural hedge against surging prices.

Normally the initial margins they have to put down to secure a derivatives hedge are no more than a few percentage points of the underlying instrument. But in recent weeks they have had to offer as much as 80 percent of the money down.

One trader, used to margin calls or reductions of €50mn during normal volatility, is now looking at ten times that within a single day.

Across the range of major trading houses the pressure of margin calls and rising demands for cash have amounted to tens of billions of dollars. At that point the financial issue becomes serious.

The business is discreet. News of a margin call is like rumors of a fire in a crowded theater. None of the major players likes to admit that it might be under pressure. But the telltale signs are there.

One marker is the price of debt issued by major trading houses. As commodity prices have surged the value of IOUs issued by the major companies that deal in commodities have plunged.

Several major players have found themselves acutely short of cash. The collapse of huge Chinese short positions in nickel has made global headlines, but humble European gas utilities are in trouble too.

A number of stories have circulated around Trafigura, one of the biggest players in the commodity market with a particular niche in dealing in the oil supplied by Rosneft.

In search of funding Trafigura has been in negotiations with private equity mega group Blackstone Inc. After that fell through it has approached Apollo Global Management Inc., BlackRock Inc. and KKR & Co. It seems to be looking for capital to the tune of $2 billion to $3 billion, which gives one an idea of the margin calls it has faced.

Trafigura also recently refinanced a $5.3 billion revolving credit facility, plus a new facility to the tune of 1.2- $2 billion. All told Trafigura according to its most recent annual report has credit lines to the tune of $66 billion with 140 banks.

Trafigura is a big player, but is it large enough to be systemic?

Owned by 1000 partners and recording profits of $3.1 billion, Trafigure would seem to be properly ranked not alongside a major commercial bank, or a Lehman-style investment bank, but in the midfield of hedge funds. Of course, of late, they too have been the beneficiaries of central bank intervention. But Trafigura does not look like another Lehman, whose short-term repo book in 2008 was numbered in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

In any case, a financial failure like that of Lehman, may not be the main threat in commodity markets. The main issue is the functioning of the market as such.

As the bigger players like Glencore Plc, Cargill Inc., Vitol Group and Trafigura Group are squeezed an even more intense pressure is applied to smaller players in the market. Their response is to pull back from the market altogether. That interrupts the smooth operation of offers for sales and bids to buy. The result is a surge in volatility and erratic price movements, which causes the larger houses that might still be able to raise finance, to pull back from the market. The overall result is that the market threatens to seize up altogether, as has happened in nickel.

As the FT reports:

In private, industry executives acknowledge they are skipping some deals to conserve cash. Lots of the price volatility of recent days can be traced by trading houses and others avoiding taking positions. The commodity market is trading risk, rather than supply and demand fundamentals. Liquidity is thin. …. Gunvor, one of the world’s biggest independent energy traders, cut trading positions after the gas price spike triggered margin calls from brokers and exchanges. The Geneva-based company reduced its exposure as wholesale gas prices surged over the past couple of months because of concerns about tight supplies ahead of the winter, said people with knowledge of the situation. The company, which has a significant European gas book, had received about $1bn of margin calls — demands for extra cash to cover its position, the people said.

This is the background against which the European Federation of Energy Traders wrote its letter of March 8th appealing for central bank intervention, to offer lender of last resort facilities to major commodity traders.

The EFET includes players like BP, Shell and commodity traders Vitol and Trafigura. What they asked for was “time-limited emergency liquidity support to ensure that wholesale gas and power markets continued to function. … Since the end of February 2022, an already challenging situation has worsened and more [European] energy participants are in [a] position where their ability to source additional liquidity is severely reduced or, in some cases, exhausted”. As a result it was “not infeasible to foresee . . . generally sound and healthy energy companies . . . unable to access cash”, the letter warned. People familiar with the matter said EFET members had raised the issue with central banks.

The EFET proposes that the European Investment Bank or central banks, such as the European Central Bank or the Bank of England, should provide support to lenders so that they do not need to intensify their margin calls on commodity traders.

“The overriding objective is to keep an orderly market for futures and other derivative energy contracts open,” said Peter Styles, executive vice-chair of the EFET board, in an interview. “Gas producers, European gas importers and power suppliers must retain the opportunity to hedge their positions.” Styles said it was possible to hedge risk without exchanges, but added that market participants needed the “liquidity, depth and visible price signals which futures exchanges with central clearing provide”.

So far Europe’s central bankers have been tight-lipped. Offering liquidity in the name of market functioning sounds laudable, but in practice what it means is providing a safety net for highly speculative, leverage commodity firms. Nevertheless, ECB vice-president Luis de Guindos has confirmed that the bank is closely monitoring derivatives markets. And it remains true that the banks involved in commodity lending can secure lender of last resort support from their central banks in any case.

The threat that markets might cease to function is, of course, alarming. And if it became a prolonged impasse it would have dramatic impact on the world economy. As Lex opines:

Financial risk aversion is applying a chokehold to oil supply chains that are already severely disrupted. This hardly benefits democracies intent on squeezing Russia via sanctions while improving energy security.

As Javier Blas of Bloomberg reminds us in a typically excellent op ed, the question of the systemic importance of commodity markets to the global financial system is not new. I was already put back in 2012 by Timothy Lane, then deputy governor of the Bank of Canada.

“Could the failure of one of the large trading houses cause serious disruption in the commodities markets?,” he asked in a speech in September 2012, arguing their size raised “the possibility” they were “becoming systemically important.”

Blas himself is skepical:

I have long argued that commodity traders don’t matter to the global economy in the same way that Lehman Brothers did: the collapse of one won’t trigger a global recession. And yet, they remain too big to be ignored — and a possible source of big trouble if left unattended. …

What if (the crisis in nickel had not been confined to nickel)?

What if, instead, it had been a large commodity trading house, and not just in nickel, but across a dozen markets? And what if the commodities affected were not nickel, but rather oil, natural gas, electricity, or, God forbid, wheat and other food staples? That may not be as bad as a Lehman-induced recession but would still be a gut-punch for the global economy.

Professor Craig Pirrong, interviewed by the FT concurred with Blas’s judgement. A liquidity squeeze on the commodity markets would lead major traders to cut positions. “This hurts, but it is not Armageddon.”

And the risk has been further reduced, as Blas remarks, by the fact that

The number of banks providing commodity-trade finance in large size has shrunk significantly over the last decade, particularly with the departures of one-time industry leaders BNP Paribas SA and ABN Amro Bank NV. Today, the traders rely on the likes of ING Groep NV, Credit Agricole SA, Unicredit SpA and a handful of other largely European banks. Several scandals, including the collapse of Singaporean oil trader Hin Leong last year, have prompted many banks to scale back their lending to the sector or even exit completely. … The result is an industry that has fewer doors to try in a crisis. … In public, all commodity traders, small and large, say everything is fine. Talk to executives in private, however, and the anxiety is plain — that their industry is one accident away from trouble. For now, we aren’t there, but central banks and policy makers should prepare for that eventuality.

And surely we have to ask: Why do the technicalities of financing energy trades matter?

What is at issue in the current moment is not the stability of the financial system as such, or the survival of particular trading houses, but the general sense of crisis and instability. Along with the war in Ukraine, the extreme spikes in oil and gas prices are a major manifestation of that instability. If there is a relevant lesson from Lehman in this context it is less a matter of financial technicalities than the realization that in a precariously balanced situation it can be very dangerous to let a major domino fall. And right now, the European gas market, is a very big domino indeed.

Another lesson from Lehman is that once the crisis has passed you must engage in wholehearted structural reform. The window of opportunity is narrow. And if you do not seize it, the structures that generated the risk in the first place will resume their growth and their vice grip on the political economy will become ever firmer.

If commodity businesses are part of the shadow banking ecosystem they too should be included in a major new regulatory push, drawing the lessons from 2020-2022.

****

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

In the mean time, please share Chartbook with your friends.

March 15, 2022

Chartbook #99 China under pressure

There is a changing of the guard in Beijing. Premier Li Keqiang is retiring and Vice Premier Liu He cannot be far behind. Once they were Xi’s point men on the economy. They leave the main stage amongst considerable turmoil.

Ukraine has thrown Xi’s geopolitics off balance and rallied the United States and its allies.

The dramatic transition in China’s domestic economic policy is continuing to cause a major shakeout. Last year China was dealing with an energy crunch. Now growth has slumped in Q4 2021 to 4 percent. For a few months the US actually grew faster than China.

The mood in the stock market is further worsened by rumors of impending fines to be levied on leading Chinese tech firms and an alarming surge in Omicron cases in Shenzhen and Shanghai, the heart of China’s manufacturing economy. Huawei, Oppo, TCL, Foxconn and Unmicron – key nodes in the smartphone supply chain – are all based in the zone affected by COVID lockdowns. The sanctions imposed on Russia are an alarming indicator of what might lie ahead in a future clash between China and the West.

The impact on the stock market has been brutal.

This thread by Rebecca Choong Wilkins vividly described the “carnage” in the Chinese markets earlier this week.

It’s carnage in Chinese markets today. These four charts show just how ugly it’s getting.

— Rebecca Choong Wilkins 钟碧琪 (@RChoongWilkins) March 14, 20221/5

By Monday March 14th the collapse in Chinese tech stocks amounted to a rout.

The China tech sell off continued in a big way today with new Covid lockdowns and regulatory crackdowns.

— Dani Burger (@daniburgz) March 14, 2022

Now the entirety of publicly-listed Chinese tech is worth less than Amazon.

h/t @DavidInglesTV pic.twitter.com/pEaWI4aQGO

It is cold comfort under these circumstances that Chinese trade with Russia surged 38.5% on the year in January and February, far outpacing Beijing’s 15.9% increase in total trade for the period.

Since the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2021 the talk in party circles has been of the “triple pressure” facing the Chinese economy, ranging from weakening expectations, shocks to supply, and a contraction in demand.

But to get a grip on China’s current situation, let us wind the clock back a little further, to the “before times”.

Remember January 2019 when Xi was warning officials to beware “grey rhinos” – the threats that become so familiar that we actually end up ignoring them – as well as truly unexpected “black swans”? Risk management was the order of the day for cadres. Xi warned that they faced “changes not seen in a century”.

Remember the “Six major effects” driving heightened global risk identified by CCP-thinker Chen Yixin in 2019 – Backflow, Convergence, Layering, Linkage, Magnification, Induction?

COVID was a classic grey rhino. But so too are the consequences of China having adopted a no-covid policy in a world which unlike China went the route of herd immunity and vaccination. It should not be surprising that Beijing now finds itself backed into a corner.

What is surprising is the failure to properly vaccinate the elderly population in a city like Hong Kong.

NEW: I’m not sure people appreciate quite how bad the Covid situation is in Hong Kong, nor what might be around the corner.

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) March 14, 2022

First, an astonishing chart.

After keeping Covid at bay for two years, Omicron has hit HK and New Zealand, but the outcomes could not be more different. pic.twitter.com/1Ol4HHs9kT

And the situation on the mainland is only little better. Omicron poses an acute risk to the vulnerable, unvaccinated and immuno-naive elderly population of China. Hong Kong is currently setting a record for a surge in mortality. Worse might be about to follow. Imagine the deaths in the nursing homes of England or New York State, multiplied ten times or more.

Earlier I warned about what might yet be around the corner.

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) March 14, 2022

Aside from Hong Kong itself, where the surge in cases in recent days is sure to have locked in hundreds more deaths, the looming crisis is mainland China, where elderly vaccination rates are only slightly better than HK pic.twitter.com/CsHW6UWWV7

The threat posed by China’s real estate bubbles has long been discussed and the challenge posed by the tech oligarchs was no secret either. These are the kind of crises that the West has regularly sleepwalked into. In this regard China’s regime is impressive precisely for the fact that it is acting in anticipation of emerging threats.

To prick the bubble is risky. It certainly isn’t good for stock markets, or growth figures. But you have to appreciate Beijing’s strategic foresight in deciding that it was time to do something about dangerous developments that were headed in the wrong direction.

The clash with the US too is no black swan. It was long foretold. It is predictable that China’s aggressive diplomacy should has unleashed a reaction from Washington. But it is not obvious what kind of diplomacy on China’s part could have avoided an eventual confrontation. To avoid antagonizing the Pentagon, China’s defense spending would have had to have been continuously reduced as a share of GDP.

Faced with the likelihood of an escalating confrontation with the US, an alliance with Russia looked like a good option. It added strategic depth, raw materials and energy supplies. It wasn’t Xi who cooked up the idea or the wolf warriors. It is an option that both China and Russia had been exploring since the 1990s.

What neither Beijing or anyone else truly reckoned with was Putin’s willingness to launch an all out invasion. Geopolitical tension over Ukraine was to be expected. China’s backing for Russia helped to foster it. But all out war with all its attendant risks is another matter altogether. From Beijing’s point of view, Putin’s extraordinary decision is no doubt a major shock.

Did China help to encourage Putin, if so that is a case of what Chen Yixin dubbed “backflow”.

In global opinion it has induced induction and magnification effects even more dramatic than the BLM moment. Ukraine has become a global symbol of popular resistance and self-empowerment.

Given the huge swing in global public opinion against China in the wake of COVID, the last thing Beijing needs is to be associated with a blood soaked and repressive Putin.

Furthermore, Russia’s aggression has rallied a coalition of hostile forces – convergence, layering and linkage in Chen Yixin’s terms.

As Gideon Rachman remarks in the FT:

The fact that the EU, UK, Swiss, South Koreans, Japanese and Singaporeans have joined in the financial sanctions on Russia has created a united front of developed economies that should concern Beijing. China has repeatedly measured itself directly against the US, ticking off milestones as it goes: largest trading power, largest economy measured by purchasing power, largest navy. Yet if China now has to measure itself against not just the US, but also the EU, UK, Japan, Canada and Australia, its relative position looks much less powerful. … The idea of an economic severance of China from the west, once unthinkable, is beginning to look more plausible. It might even appeal to the growing constituency of economic nationalists in the west who now regard globalisation as a disastrous error.

To exert pressure on Russia, the Western coalition has deployed its most dramatic weapon – a targeted attack on Russia’s national currency reserves.

The move against Russia’s fx reserves is a surprise. But, as far as China is concerned, this too ought to be considered a grey rhino rather than a black swan. Though the extent of the measures against Russia is certainly surprising, it has long been discussed that China will have difficulty escaping the grip of the dollar. Add the Europeans and you have a “Western bloc” that monopolizes 80 percent or more of reserve assets. A country like China that has used giant export surpluses to drive a lopsided pattern of growth will, in the end, find itself boxed in.

This is compounded by the entanglement of Chinese business with western financial markets and the dollar system. It was telling that President Xi Jinping’s in his address to the WEF in January warned Western economies not to “slam on the brakes or take a U-turn in their monetary policies.” A sudden tightening of US policy would squeeze the entire global economy. In light of the recessionary tendencies inside China, it would be most unwelcome in Beijing.

Russia faces a Eurodollar trap. China has to contend also with the pivotal role of Japan’s financial system as a conduit for dollars into the East Asian economy.

As Andrew Hunt and Ben Ashby write in Nikkei Asian Review, Japan’s megabanks perform a “vital but little understood function” in supplying dollars to the Asian economy.

Despite the growth of China’s banking system, much of it remains domestically focused. China’s banks also lack the creditworthiness and international connections that Japan’s financial institutions enjoy.

With the financing of much of Asia’s trade and the flows in and out of its various financial centers still heavily dependent on Japan, Japan’s bankers, squeezed between an overheating U.S. and an increasingly troubled China, have a difficult balancing act to perform…..

With the Fed now worried about inflation, likely to lead to a tightening of global liquidity, Japanese banks must now make some tough decisions over what to do with the more than $5 trillion worth of overseas claims they have amassed.

Do they cut back on risk and reduce their Eurodollar borrowing, charge a higher interest rate to borrowers, or become more selective in their lending? Our guess is that they will do a mixture of all three.

With $166 billion of direct exposure to mainland China and Hong Kong, and with huge problems beginning to surface in Chinese real estate, this sector will be a prime candidate for risk reduction. It will be a difficult balancing act and, if Tokyo’s bankers do not pull it off, it may add to China’s own problems at an already difficult time.

The Ukraine crisis has seen Japan aligned squarely with the United States. Rising tension with China points in the same direction.

As far as Beijing is concerned, Minxin Pei writing in Nikkei Asia Review comes to a bleak conclusion.

For China, which might have benefited from a prolonged period of tensions between Russia and the West, the paths ahead have suddenly become far more treacherous. Instead of being a net beneficiary of a conflict between Russia and the West, China now finds itself perilously close to being collateral damage. While the crippling economic blows against Russia are applauded in the West, Chinese leaders watch them with great alarm. Their country is far more economically tied to the West than Russia is. Although the same type of economic sanctions leveled at Russia would unavoidably hurt Western economies, they could be catastrophic for China in the event of a war across the Taiwan Strait.

But talk of Beijing becoming collateral damage seems exaggerated.

Ukraine is ultimately a European problem. A prolonged period of high tension between the West and Russia will be hard for America and its allies to sustain. It will be surprising if the current sense of purpose in the West endures.

The domestic problems of the Biden administration continue and will likely intensify in the course of 2022. His nominations for the Fed board are in trouble along with the rest of his domestic agenda.

Whether Europe will actually back decisive action against Russia remains to be seen. In Germany there are huge political obstacles to taking decisive steps against Russia. Whatever the EU decides to do, it has a bona fide energy crisis to deal with.

No doubt Russian energy is hard to do without, but it if can hold its nerve, Beijing might well conclude that there are limits to the kind of economic pressure it should expect.

Furthermore, the G7 front against Russia does not negate the basic diagnosis of growing multipolarity. In abstaining on the UN vote of censure against Russia, China had the company of India and governments representing more than half the world’s population.

With relations between Saudi Arabia and the US frosty, Xi is weighing an invitation to meet with MBS in Riyadh in April. Whatever Europe and America’s concerns, it is China remains the world’s number one fossil fuel importer and that earns it respect.

And if you turn the gaze back to the US, the fact remains – as discussed in Chartbook #94 – that the US does not truly have a policy to offer in the Indo-Pacific strategy. It has published a blueprint. But is concerns are overwhelmingly domestic – fashioning a trade policy that is acceptable to America’s “middle class”. Whether that will suit any major partners in Asia is another matter altogether. The war in Ukraine is not going to persuade major Asian players that their future belongs in an anti-China camp masterminded by Washington. They do not want to have to choose.

Ultimately, what matters most is that China sustain its position as the leading driver of global economic growth. It needs to be better balanced in economic, social and environmental terms. That will tend to reduce the growth in China’s appetite for raw materials and industrial components. But it may result in even larger and more diversified imports from the rest of Asia.

What Beijing is currently planning to stimulate its economy seems to be a blend of different policy tools. It is expanding social credit, the basic driver of demand. New total social financing hit a record high of 6.17 trillion yuan in January, beating market expectations of around 5.4 trillion yuan. New bank loans also rose to a record high of nearly 4 trillion yuan in January. But the February numbers were disappointing, indicating how much work Beijing may need to do to hit its growth target of 5.5%.

On January 18 Liu Guoqiang, a deputy governor of the PBOC promised that the central bank will “open the monetary policy toolbox wider, maintain stability in the money supply and avoid a collapse in credit.”

As in 2012, 2016 and 2019 one analyst noted, Beijing is in a “race between slowdown and stimulus”. But the real challenge for Beijing is to find new sources of growth.

Authorities in recent months have rolled out cash subsidies for high-end manufacturing, affordable housing and sustainable energy. Not all Chinese stocks are selling off. So-called Chinese red chips — Hong Kong-listed Chinese companies with significant state control — climbed 20% in six months. Since Xi pledged in late 2020 that China would hit carbon neutralityby 2060 renewable energy funds have in some cases returned more than 40%.

The regime is clamping down on excessive lending in private real estate, but at the same time the government had announced plans to build 6.5 million low-cost rental apartments by 2025. If this is realized it will mean that an estimated 26% of new home supply will be offered at 30% below the market rate. In early February lending for such projects was exempt from limits on property lending, prompting talk of the “next big thing”.

The annual Two Sessions closed last week with a commitment to a 5.5 percent growth rate. If realized this will be well below the growth in public spending which is expected to rise by 8.4 percent and result in a deficit of just below 3 %.

Source: Caixin

Within Chinese public expenditure, infrastructure investment will continue to play a key role, with central government expenditure rising by 5% to 640 billion yuan. But on top of that the central government will transfer 9.8 trillion yuan to local governments, up 18% from 2021, much of which will go towards funding investment spending.

This frankly sounds like relatively marginal adjustments to the familiar growth formula. How far “common prosperity” is really a comprehensive new formula and new vision of growth remains to be seen. But that is truly the decisive question also as far as China’s global standing is concerned.

Putin’s attack on Ukraine has shifted the international balance. It has, to say the least, not been a success for Russia so far. In a protracted struggle with the West, Russia might still end up sliding into China’s more or less reluctant embrace. But China won’t rush to take up that role and it will surely guard against getting sucked into a further escalation of US sanctions. What is clear, is that above all its future depends on facing domestic challenges both in the medium and the short-term.

If Beijing suffers a devastating Omicron outbreak in the next few months the entire narrative of the period since 2020 will have to be rewritten.

***

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

In the mean time, please share Chartbook with your friends.

March 14, 2022

Chartbook #98: Eastern Europe in the financial frontline

In 2008 Eastern Europe was caught up in the global financial crisis. In 2021 it was hit late by the COVID crisis. In 2022 Eastern Europe is in the frontline of the conflict with Russia over Ukraine.

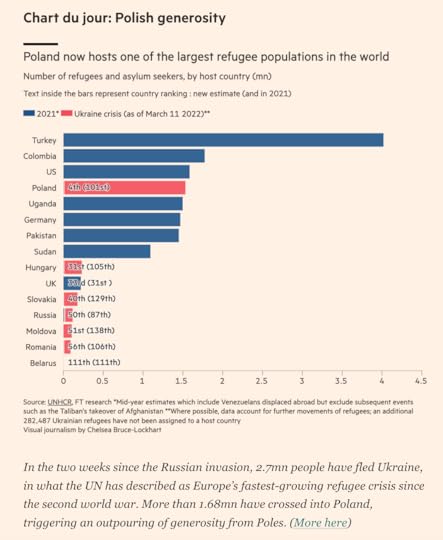

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Eastern Europe and Poland in particular are facing a gigantic refugee flow.

Source: FT

Meanwhile, the shockwaves from sanctions, surging energy prices and a loss of confidence are being felt across the economies of the region.

“You can draw a correlation map between proximity to the conflict areas and market impact,” Kasper Elmgreen, head of equities at Amundi in Dublin, told Katie Martin of the FT.

Poland and the Baltics, in particular, have strong trading and financial ties both to Russia and Ukraine, which put them in the firing line.

The most visible sign of the stress is to be seen in currency markets. The Polish Zloty has plunged across the psychologically important hurdle of 5 zloty to the euro, a more serious sell off even than during the 2008 crisis.

Source: Bloomberg

In recent weeks there have even been moments of near panic in Poland, which the central bank countered with a blunt assertion of authority. Too much financial news is bad for your grip on reality seems to be the line from central bank boss Glapinski.

After people rushed to withdraw money in Poland, the central bank chief has criticised the "stupid wave of panic".

— Notes from Poland

"These people are watching too much of the internet…Especially the young, educated in big cities…Poland is an absolutely safe country" https://t.co/rbpHnSfe4k(@notesfrompoland) March 10, 2022

Hungary’s forint tumbled as much as 3.2% and came close to 400 against the euro.

Central banks in both Poland and Hungary have taken a robust stance. They point out that the shock depreciation is not consistent with fundamentals. When the war scare has passed, their currencies should, therefore, offer good value to investors. In the mean time the central banks see no reason not to intervene in support if devaluation threatens either price stability or financial stability.

Hungary’s central bank said it was prepared to “intervene with all elements of the toolbox to ensure the stability of the domestic financial markets … The [central bank’s] goal is that the increased risks due to geopolitical conditions do not endanger the price and financial stability of Hungary. Money market movements are not fundamentally justified, but they increase upside inflation risks,” it said.

The Czech national bank too has been intervening to support the koruna.

The Czech National Bank defended its measures by arguing that they were “fully in line with the CNB’s previous communications, which emphasised that the central bank is ready to react to excessive exchange rate fluctuations using its instruments in line with the managed float regime”.

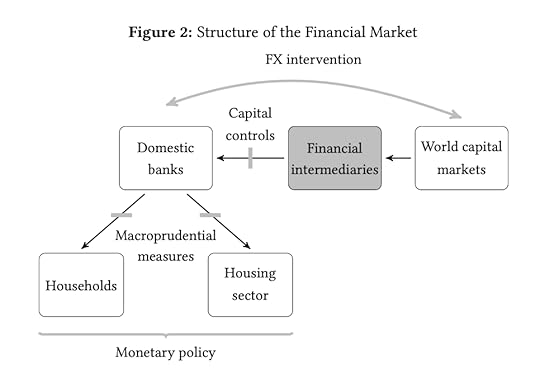

The fact that Hungary’s central bank referred to a “toolkit” is telling.

The East European policy-makers are doing precisely what you would expect competent emerging market policy makers to do under the circumstances. Tactical use of interest rates and foreign exchange interventions backed up by substantial reserves have become the normal way in which emerging markets manage their exposure to global financial risks. As I discussed in Shutdown, the same set of policies were used by EM to meet the financial shock from COVID in the spring of 2020.

Through successive crises the EM have developed a managed model globalization which in the end offers a more functional mix than adherence to doctrinal purity on floating rates and a balance of payments entirely dominated by private flows.

As Claudio Borio of the BIS put it in a speech he gave in June 2019 in managing their monetary policy frameworks, the practice of major EM had moved ahead of theory.

In July 2020 a team at the IMF consisting of Suman Basu, Emine Boz, Gita Gopinath, Francisco Roch, Filiz Unsal proposed to close that gap between theory and practice by offering what they called an A Conceptual Model for the Integrated Policy Framework.

The East European central banks certainly have the resources they need to pursue a stabilization strategy.

As Reuters explains:

The Czech bank has large reserves built up between 2013 and 2017, when it bought foreign currency to keep the crown weak. Reserves amounted to around 66% of gross domestic product at the end of January.

All told the region’s four biggest economies have amassed foreign reserves totaling roughly $430 billion.

Source: Bloomberg

The response of central banks across the region has reflected these reserve positions with Czechia, Poland and Romania intervening in markets and Hungary relying on interest rate increases.

As Jonathan Wheatley reports for the FT,

Hungary’s central bank raised its key policy interest rate by three-quarters of a percentage point on Thursday to 5.35 per cent, a bigger move than expected and the largest since 2008.

Even before the crisis, whilst the ECB argued over its policy response, across Eastern Europe policy-makers were responding to inflationary pressures.

Source: Bloomberg

The Ukraine shock impacts East European economies that were already experiencing more rapid inflation than their West European neighbors. With inflation at 10 percent in the Czech republic, the real interest ahead of the crisis is minus 5 percent. In Poland the gap between inflation of 9 percent and the policy rate of 2.75 ahead of the crisis was even larger.

Nor was it merely prices that were growing fast. they were also experiencing a particularly rapid economic rebound from COVID.

ING which publishes excellent research on Eastern Europe cites four risks to Polands economic growth in 2022.

(1) the decline in trade with Russia and Ukraine as well as (2) a general worsening of household and business confidence which will curb spending and domestic demand. Additional downside factors include (3) an energy shock that will further boost commodity prices and undermine purchasing power. Prolonging anti-inflation measures (indirect tax cuts) until December may counteract the increase in crude oil prices to as much as $130 per barrel and a potential hike in natural gas prices by 30% in the second half of 2022. On top of that (4) potential breaks in commodity supplies as a result of military action may also hit the economy, however, the impact is difficult to assess.

All told this leads it to cut its previous GDP growth forecast of 4.5% by 1.3%. .

As Michal Kranz explains in this nice piece for Foreign Policy, Poland has emerged as linchpin of the Western response to Russia’s aggression.

On its Eastern flank the smaller Baltic states are scrambling to adjust to the new situation. At least financially they are better prepared than they would have been four or five years ago when Latvia was rocked by a gigantic Russian money-laundering scandal. As the FT explains:

under heavy pressure from the US and international authorities it embarked on a clean-up of its banks and is now advising other EU countries on how to improve their anti-money-laundering controls. Non-resident deposits — those from outside the country, mostly Russia — have fallen sharply in the past five years.

We should count our blessings that we are not dealing with a gigantic Scandinavian and Baltic banking crisis as a result of the financial sanctions on Russia.

In the event of a financial squeeze the ECB would be the obvious point of call for the East Europeans. The FT in an editorial recommends the provision of swap lines as it did in 2020.

In the short-run the ECB has extended the EUREP emergency facility it set up in 2020 until Jan. 15, 2023. As Bloomberg explains EUREP allows central banks to receive euros in exchange for some euro-denominated debt securities.

EUREP will continue to complement regular euro liquidity-providing arrangements for non-euro area central banks, the ECB said Thursday. These measures form a “comprehensive set of backstop facilities to address possible euro liquidity needs in the event of market dysfunctions outside the euro area that could adversely affect the smooth transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy.” Requests for individual euro liquidity lines will be assessed by the Governing Council on a case-by-case basis, it said. Poland’s central bank said … it was discussing opening foreign-currency swap lines with international counterparts including the ECB, the Federal Reserve and the Swiss National Bank.

One problem that the Polish banking system could urgently do with help with, is, as Bloomberg reports, the immediate financial counterpart to the refugee flow.

Ukrainians struggling to stay afloat in Poland need to swap Ukrainian hryvnia into zloty, most often in quantities of a few hundred euros at a time. Financial markets in Ukraine are closed. In Poland this has led to a huge unbalanced flow of hryvnia into Polish foreign exchange booths and banks, currency for which there is no demand even at massively depreciated rates. As one exchange booth operator told Bloomberg.

“Banks aren’t interested in buying hryvnia from us and it’s not possible to send the currency back to Ukraine safely,” Pawlak, manager of Tavex in Poland, said by phone. “Our reserves are quickly becoming depleted.”

At this moments, markets cannot be a sensible mechanism to value Ukrainian currency and assets. Ultimately this is a political question. How far should Ukrainian refugees be asked to bear the financial consequences of massive devaluation? How far will they be supported by European assistance?

National Bank of Poland Governor Adam Glapinski said on Wednesday that he’s consulting with Ukraine’s central bank, commercial lender PKO Bank Polski SA and its smaller peers to alleviate the problem, calling on the industry to do more.

Following a currency swap agreement with Poland's central bank (hrynia-zloty), National Bank of Ukraine is now negotiating such an agreement with Sweden's Riksbank and seeks to initiate such deals with other central banks.

— Evgen Vorobiov(@vorobyov) March 10, 2022

As far as Poland’s central bank governor Adam Glapinski is concerned, one thing is clear. The war in neighboring Ukraine, may have upended European security and fueled a record weakening of the zloty, but this is not an argument for Poland to join the euro,

Glapinski said on Wednesday that membership in the 19-nation currency area won’t make his country — the European Union’s biggest economy outside the euro region — safer in military terms. Joining the euro, however, would lead to slower economic growth and higher inflation, he said, without providing any evidence to support this claim.“We’d lose the opportunity to catch up with richer countries,” Glapinski told reporters in Warsaw on Wednesday. Poles would be reduced to a nation of “asparagus-pickers,” he said, referring to a practice of Polish seasonal workers who travel to Germany to help collect the crop each year.

The comment exemplifies the broader tensions in play. The larger East European states benefit from their attachment to broader institutions of the West, like NATO and the EU, but they do not want to sacrifice any more of their sovereignty than they have to. Indeed, in a dangerous world they see those institutions primarily as supports for their national independence. Russia’s aggression only reinforces that double impulse towards both alliance and independence. It also confirms their broader diagnosis of the threat they face from the East. As Michal Kranz explains in this nice piece for Foreign Policy,

Poland no doubt relishes its new centrality to the Western alliance. At the same time, however, as Glapinski’s comment illustrates, they are also acutely aware of the fact that they could easily find themselves relegated to a subordinate position.

It should not be forgotten that the nationalist government of Poland has provoked an explosive dispute with the EU over basic issues of the rule of law. Or that in 2015/6 Warsaw was resolutely uncooperative with Berlin in its efforts to handle the “Syrian” refugee crisis.

Right now the mood in Europe is still one of solidarity and cooperation, but it could easily tip into something far more ugly.

March 12, 2022

Chartbook #97: Is boycotting Russian energy a realistic strategy? The German case.

How do you weigh the effectiveness of an economic weapon? How do you gauge the likely impact on your antagonist? How do you assess the cost to yourself?

As Nick Mulder has shown us in his powerful new history of the economic weapon, the calculus of sanctions is one of the important domains in which economic and social scientific expertise first came to the fore in 20th-century government.

Today Europe faces the question of how to respond to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The most obvious way to apply maximum financial pressure to Russia is to stop purchases of oil and gas. Russia’s export earnings are surging. The largest part of that revenue comes from Europe.

Russia just published its current account surplus for February. We compare Feb. 2022 to the same month in previous years. This year is off the charts (red), because the rise in energy prices – due to Putin's invasion of Ukraine – confers a huge hard currency windfall to Russia… pic.twitter.com/pM8Fr2XmoC

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) March 11, 2022

Stopping oil and gas purchases would clearly deal a severe blow to Russia. But what would such a boycott cost Europe?

Compared to the suffering of Ukraine the answer, of course, is that the costs will be slight. But no responsible government can avoid taking the costs seriously and weighing the balance. Apart from anything else, if we are in for a long economic war with Russia then we have to ensure that sanctions can be sustained.

Deliberately shutting off a large part of one’s network of energy supplies would be a dramatic demonstration of solidarity with few precedents outside actual wartime. It is the scale of action demanded by climate activists and climate experts, but commonly dismissed as “unrealistic”. The scale and type of economic shock that would be delivered to Europe’s economies – a huge “supply shock” – is most closely paralleled by the actions taken in response to the COVID crisis. As we know from recent memory the pain was intense. The hardship fell unequally on those with low incomes and the measures were highly controversial. We have not yet digested the full impact of COVID. Will Europe’s governments make a second dramatic choice over Ukraine? And how can the costs and benefits be assessed?

Nowhere is this decision weightier than in Germany, Europe’s economic great power. Germany is the key to any European boycott because it buys so much Russian energy. By the same token the impact on the German economy of ending energy imports from Russia is likely to be large. Energy has long been part of German statecraft, a way of exercising leverage and shaping its neighborhood. Will Berlin, faced with the current crisis, deploy the full force of the economic weapon?

The basic facts are clear. Oil accounts for 32 percent of German primary energy input and one third of that comes from Russia. Gas accounts for 27 percent of Germany’s primary energy input, of which 55 percent comes from Russia. Of the coal burned in Germany, which accounts for 18 percent of energy input, 26 percent comes from Russia. All told that means that just over 30 percent of Germany’s primary energy input comes from Russia.

Pipeline gas is the key issue because it cannot be easily substituted by alternative sources of supply.

At the political level, the decision must be agreed between the three parties in the traffic-light coalition, with Chancellor Scholz and Robert Habeck at the Ministry for Economic Affairs and climate playing key roles.

So far the Economics Ministry has taken a cautious position. Habeck has described the consequence for the German economy of boycotting Russian energy as being of the “heaviest proportions” (schwersten Ausmaßes).

That sounds dramatic and the scale of dependence is clearly large. But how do we actually calibrate the likely cost? Only economic expertise can give us any idea as to the orders of magnitude.

The German economics profession, it cannot be repeated too often, is no monolith. It is a world in motion. The problem of an energy boycott is not one that can easily be resolved by reference to familiar positions on inflation, long-term fiscal sustainability etc.

No doubt the analysts in the German economics ministry are burning midnight oil. So far, their calculations have remained behind closed doors. But in the last week the expert debate has spilled into the public sphere.

On March 8 the Leopoldina National Academy of Science published a paper focusing on the technical possibilities of substituting non-Russian sources of energy. They offered a practical to do list of measures with the conclusion that

Even an immediate supply stop of Russian gas could be “handled” by the German economy (handhabbar). There may be shortages in the coming winter, but there are options, through the immediate implementation of a package of measures, to limit the negative effects and to cushion the social impact. .

The authors of the Leopoldina memo were in the main Professors in STEM fields. Economists (Grimm, Schmidt, Wagner … apologies to anyone else I missed) were in a small minority and the memo offered no estimate of the likely costs of the measures they suggested.

The economic question was mapped the same day by a paper co-authored by a distinguished group of economists working both inside and outside Germany.

The team consists of Rüdiger Bachmann: University of Notre Dame, David Baqaee: University of California, Los Angeles; Christian Bayer: Universität Bonn; Moritz Kuhn: Universität Bonn und ECONtribute; Andreas Löschel: Ruhr University Bochum; Benjamin Moll: London School of Economics; Andreas Peichl: ifo Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Universität München; Karen Pittel: ifo Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Universität München; Moritz Schularick: Sciences Po Paris, Universität Bonn und ECONtribute with research support from Sven Eis.

It is a truly broad church group with no obvious political or institutional alignment in Germany’s spectrum of foundations and think tanks.

Everyone interested should check out the paper. It is technically sophisticated, using a state of the art global trade model, but it is written both in English and German and it is, as far as I am able to judge, comprehensible in its basic logic. We are very much in their debt for the speed and sophistication of this preliminary estimate.

I’ll do my best here to relay some of their key points.

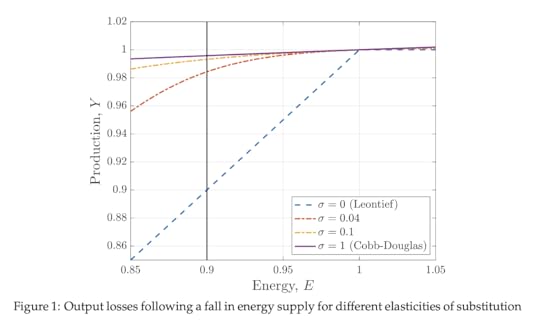

What happens if you cut off Russia as a source of supply depends on whether you can substitute other sources of energy and how far you can economize on energy use.

Bachmann et al take as their main scenario the case in which total gas supplies fall by 30 percent with the result that Germany loses roughly 8 percent of its primary energy supply. What will be the impact on industry, households and the service sector?

To provide a benchmark estimate they start from the multi-sectoral model of trade published by David Baqaee & Emmanuel Farhi in 2019. That model is a very ambitious attempt to model global trade as a set of general equilibrium flows.

The benchmark model has 40 countries as well as a “rest-of-the-world” composite country, each with four factors of production: high-skilled, medium-skilled, lowskilled labor, and capital. Each country has 30 industries each of which produces a single industry good. The model has a nested-CES (constant elasticity of substitution) structure. Each industry produces output by combining its value-added (consisting of the four domestic factors) with intermediate goods (consisting of the 30 goods). The elasticity of substitution across intermediates is θ1, between factors and intermediate inputs is θ2, across different primary factors is θ3, and the elasticity of substitution of household consumption across industries is θ0. When a producer or the household in country c purchases inputs from industry j, it consumes a CES aggregate of goods from this industry sourced from various countries with elasticity of substitution εj + 1. We use data from the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) (see Timmer et al., 2015) to calibrate the CES share parameters to match expenditure shares in the year 2008.33

One of the striking conclusions from the model is that the gains from trade may be much larger than is suggested by many standard models.

For example, for the US, the gains from trade increase from 4.5% to 9% once we account for intermediates with a loglinear network, but they increase further to 13% once we account for realistic complementarities in production. The numbers are even more dramatic for more open economies, for example, the gains from trade for Mexico go from 11% in the model without intermediates, to 16% in the model with a loglinear network, to 44.5% in the model with a non-loglinear network.

This is important for the Russia sanctions debate because many trade models generate very modest gains from trade and correspondingly small effects from any interruption to trade. Indeed, if I read the Baqaee and Farhi paper correctly, it would also allows us to assess the impact of sanctions on Russia. I hope someone will soon perform the same kind of calculation that Bachmann et al have performed for Germany for the Russian side.

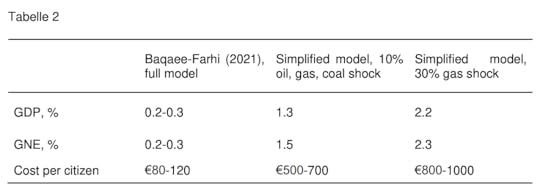

In choosing the Baqaee and Farhi model as their workhorse, Bachmann et al presumably hope to ensure that they capture the full effect of any trade interruption. Nevertheless, the results, in all scenarios, are surprisingly modest.

The workings of the Baqaee-Farhi model are very complicated, but the basic intuition is easy enough to follow.

Energy is vital but it does not make up a huge share of expenditure (GNE, Gross National Expenditure). The only scenario in which an energy shock causes catastrophic damage is one in which there is literally no way of substituting or switching economic activities impacted by the loss of energy supply. This would be the case if the basic parameters of production are unalterably fixed – the so-called Leontief case. Taken at face value, that scenario would yield implausibly dramatic results.

As soon as one assumes even a very small degree of substitutability, the effect of the energy supply shock is much more muted. According to the calculations by Bachmann et al, even in a worst case scenario the impact on GDP would come to 3 percent, which is less than the 4 percent shock that the German economy suffered in the COVID crisis.

As Bachmann et al remark

Purely in the spirit of being conservative, we therefore postulate a worst-case scenario that doubles the number without input-output linkages from 1.5% to 3% or €1,200 per year per German citizen. This number is an order of magnitude higher than the 0.2-0.3% or €80-120 implied by the Baqaee-Farhi model. We should emphasize that this is an extreme scenario and we consider economic losses as predicted by the Baqaee-Farhi model to be the more likely outcome

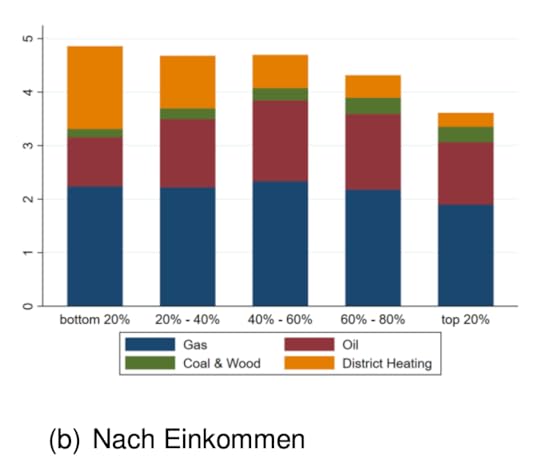

Bachmann et al also provide some pointers as to the distributional impact of any measures. As a share of income, heating and fuel costs do vary by income but not by as much as one might anticipate.

A severe spike in gas and oil prices is likely to cause serious hardship only at the bottom end of the income pyramid, where support should be targeted.

The Bachmann et al paper refrained from declaring the measures “manageable”, as the Leopoldina paper had done. But the scale of the losses they calculated certainly suggested that if sanctions were politically necessary they would be economically feasible. They recommended a cost mitigation strategy that cushioned low income consumers, but otherwise allowed the surge in energy prices to drive the search for energy efficiency. They also recommended that if sanctions were to be applied, they should be applied as soon as possible, so as to enable households and businesses to begin adaptation well before the fall and winter of 2022-2023, when supply difficulties will become most severe.

Taken together the Leopoldina and Bachmann et al papers tended to increase the pressure for action. If alternatives to Russian oil and gas were technological feasible and the economic cost was no more than a few percentage points of GDP, the onus was on the politicians to make the choice. Was it not time for Germany to be brave?

When he was asked about the Bachmann et al study Minister Habeck responded that his Ministry estimated the likely impact of sanctions as far more serious.

But how much more serious? The answer Habeck gave to journalists was a contraction of 5 percent. The significance of that figure is that it was worse than COVID.

Where did it come from?

In the days that followed the Leopoldina and Bachmann et al papers, other experts pushed back, expressing caution and even out-right skepticism about the estimates provided by their colleagues.

Michael Hüther Director of the business-backed private research center Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft in Cologne took issue vociferously with the conclusions of the Leopoldina report. Declaring that a certain policy was “manageable” was a matter of value judgement Hüther insisted.

Die dabei zitierten Studien zeigen nicht, dass man es machen kann oder machen sollte. Die Aussagen, ob dies "handhabbar" oder "machbar", sind reine Werturteile. Verantwortliche Politikberatung muss das deutlich machen. Über die Wirksamkeit der scheinbar "Handhabbaren" wird …

— Michael Hüther (@michael_huether) March 11, 2022

Later in the week two analysts from the Institute – Thilo Schäfer and Malte Küper – published a comment rebutting the idea that a gas and price stop was manageable. They insisted that it would involve “incalculable risks” and the certainty of a severe price shock with damaging effects for industry.

But “incalculable” is not the same as 5 percent.

It was not just the Leopoldina report that was coming under fire. As reported by Handelsblatt, the Bachmann et al paper was criticized in a confidential paper for the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate authored by Tom Krebs and Sebastian Dullien. Whereas the Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft was business-aligned, Krebs and Dullien are aligned with the SPD and the trade union movement. When Olaf Scholz headed the Finance Ministry, Krebs took leave from his chair at Mannheim University to serve as a visiting professor. In April 2019 Dullien succeeded Gustav Horn as scientific Director of the Institut für Makroökonomie und Konjunkturforschung (IMK) the macro think tank of the Hans Böckler Foundation of the German trade union movement.

In a paper presented to Habeck’s Ministry Dullien and Krebs apparently argued that Bachmann et al underestimated the likely impact of the shock. According to their calculations they thought a contraction of 4-5 percent of GDP more likely.

Ein sofortiger Lieferstopp (cold turkey) von Gas und Öl aus Russland könnte eine neue Wirtschaftskrise verursachen. Warum das ein sehr wahrscheinliches Szenario ist – ein

— Tom Krebs (@tom_krebs_) March 11, 2022. 1/

As Ben Moll one of the co-authors of the Bachmann et al paper pointed out, Krebs and Dullien did not offer a model to support their estimate. And, as Moll put it, “it takes a model to beat a model”. In fact, the Dullien and Krebs paper had never been intended for public discussion. It was leaked to the Handelsblatt. The IMK is now racing to run its own simulations to back up the initial estimate.

Meanwhile, Dullien and Krebs found themselves in an unfamiliar alignment with Hüther and the team at the Cologne Institute.

Dazu: wir haben bereits vereinzelt Produktionsstillstand wg der hohen Energiepreise. Und: Angebotsprobleme bei kritischen Rohstoffen wie Palladium etc.

— Michael Hüther (@michael_huether) March 11, 2022

Though the line between the two camps seemed clearly drawn, the striking thing is that the Krebs and Dullien estimate of 4-5 percent was not, in fact, dramatically different from the higher estimate by Bachmann et al.

Given the uncertainties involved in the calculation, the divergence is not significant.

After all, the point of the Bachmann et al paper was not to provide a very precise figure, but to gauge the likelihood of extreme negative outcomes. A 4-5 percent fall in GDP would be higher than their modeling suggested and much higher than any outcome suggested by the Baqaee and Farhi model, but it confirmed their broader conclusion that a catastrophe was unlikely.

As Moll pointed out, Goldman and Sachs analysts had also arrived at a similar conclusion. Germany would be hit hard, but its economy would not suffer anything like a catastrophic shock.

Und hier noch die Grafik aus der Goldman-Sachs Studie die auf 3,5% kommt.

— Ben Moll (@ben_moll) March 11, 2022

10/10 pic.twitter.com/3xJfLDYPW0

So, if Krebs and Dullien felt they were at odds with Bachmann et al, the difference did not in fact lie in their estimate of the economic outcome to be expected, but in their evaluation, in political, social or other terms, of that outcome.

As Moritz Schularick another co-author of the Bachmann et al paper told Handelsblatt: „The conclusion to be drawn should only be really be completely different, if we were talking about 20 or 30 percent.” That is, unless your premises in political, economic and social terms are different, or if beneath the apparent convergence on a prediction of 3-5 percent in GDP contraction you actually imagine very different realities.

Beyond the immediate protagonists in the four-way exchange, one senses other influential figures in the German economics scene aligning themselves on the question of sanctions. Clemens Füst, who heads the IFO institute in Munich, agreed with Krebs in warning of the possibility of cascade effects which result from single firms in production chains suffering sudden stoppages. If this was to occur on a large-scale the contraction in production would be larger than if the effect impacted evenly across the entire economy.

Das ist meines Erachtens ein wichtiger Punkt den @tom_krebs_ hier hervorhebt: https://t.co/VIqOM1Dp0I

— Clemens Fuest (@FuestClemens) March 10, 2022

More speculatively, and somewhat tongue in cheek, what is one to make of the fact that Lars P Feld who advises Christian Lindner at the Finance Ministry tweeted out Nick Mulder’s jaundiced take on the history of sanctions published by The Economist?

If one follows the Bachmann et al line it is tempting to say that the upshot of the economic analysis is that the cost to Germany of a boycott would be significant but not so significant that the idea can be dismissed as entirely unreasonable. Their analysis thus puts the ball back in the court of politics. That was the line taken by the Handelsblatt’s Julian Olk.

But on closer inspection it seems that the separation between economic expertise and political judgement is not that neat. If one believes that the costs are, in fact, “incalculable” then excessively precise estimates of the likely costs will in themselves – regardless of the conclusions reached – tend to encourage an activist bias entailing considerable risks. Secondly, the divergent assessment of the meaning of similar estimates of GDP contraction suggests that GDP is insufficient as a measure to capture what rival camps think is essential about the economy. That may help to explain the caution of those who are closer to industry or labour and have to think through the implications of what a 3, 4 or 5 percent shock would actually mean for individual firms, supply chains and workers. Rather than a matter of bias that should be considered a matter of situated perspective, or standpoint. Closeness to “the interests” of producers reveals things that cannot easily be seen from the vantage point of a global macro model however sophisticated it may be.

Certainly, if Berlin is to decide to go ahead with a boycott, what will be required will be a coalition-building exercise that will need to extend from the broader public, to key interest groups and to the realms of expertise, where the scale of the problem is being measured and assessed. Persuasion, calculation, mobilization and preparation is the work that would make a policy of full-scale sanctions realistic.

***

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

In the meantime, please share Chartbook with your friends.

March 11, 2022

Ones & Tooze: How Rising Oil Prices Will Change the World as We Know It

As the war in Ukraine entered its third week, the price of a barrel of oil peaked at $130, its highest since 2008. The pain is already spreading around the world—to people who rely on gas to get to work or oil to heat their homes. On the show this week, Adam and Cameron discuss the possible longterm effects of the spike, including the impact on inflation and climate change.

Also on the show: Don’t bet against New Yorkers. In the first month since gambling became legal in the state, residents put down a record $2 billion in wagers.The real winners are the tax authorities.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

March 8, 2022

John Mearsheimer and the dark origins of realism

“Why is Ukraine the West’s fault?” This is the provocative title of a talk by Professor John Mearsheimer – a famous exponent of international relations (IR) realism – given at an alumni gathering of the University of Chicago in 2015. Since it was first posted on YouTube, it has been viewed more than 18 million times.

In 2022 Mearsheimer is still delivering his message, most explosively on 1 March in an ill-advised down-the-telephone interview to the New Yorker. Against the backdrop of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Mearsheimer’s provocation is causing outrage. And it raises the question: what is the realism that Mearsheimer claims to espouse?

On the one hand, Mearsheimer is disarmingly even-handed. The push for Nato expansion in 2008 to include Georgia and Ukraine was a disastrous mistake. The overthrow of the Moscow-backed Viktor Yanukovych regime in 2014, a revolution supported by the West, antagonised Russia further. The West should accept responsibility for having created a dangerous situation by extending an anti-Soviet alliance into what is left of Russia’s sphere of influence. And then comes the inflammatory conclusion: Putin’s violent pushback should not come as a surprise.

Read the full article at The New Statesman

Chartbook #95: Is “Ukraine the West’s fault”? On great powers and realism

This fucking van in Seattle blasting the John Mearsheimer lecture on Ukraine lmao the propagandamobile pic.twitter.com/TUe7r0V7dH

— ɴɪɢʜᴛᴍᴀʀᴇ-ᴠɪꜱɪᴏɴ ɢᴏɢɢʟᴇꜱ(@worldlytutor) March 8, 2022

Yup. You read that correctly. That is apparently a van blasting a speech given by Chicago University professor of international relations John Mearsheimer on the Ukraine crisis over its loudspeaker. My guess is the speech in question is the one that Mearsheimer gave to the alumni of Chicago University in 2015. It is well worth watching, for the brilliant rhetorical performance alone. Mearsheimer really knows who to deliver a line.

When I checked on Monday morning the viewer figures stood at 17.5 million up from 15 million in the not too distant past. Today, as of the time of writing, the number is well past 18 million.

It has apparently gone viral in China.

Unsurprisingly, given Mearsheimer’s title, he has been called out by various liberal and neoconservative critics and there is a bit of a furore, involving Anne Applebaum et al. The idea that “Ukraine is the West’s fault” causes a lot of indignation.

I feel engaged by the debate because I share much of Mearsheimer’s analysis of the build up of tension between Russia and the West over Ukraine – at least in outline – but I reject his conclusion. Not only is explanation not justification, but diagnosis of a structural tension is also only the first step in an adequate explanation, certainly one that deserves to be called realistic.

On the distinction between explanation and justification, Eric Levitz at New York Magazine is predictably lucid.