Adam Tooze's Blog, page 24

March 6, 2022

Chartbook #93: Russia’s $720m per day gas windfall – the lopsided economic war

Like most folks I’ve been staggered by how rapidly the West has escalated the economic war against Putin’s regime.

But, we must remind ourselves that energy remains the giant exception.

In the oil market, there are reports of “self-sanctioning” by Western firms, which is making it harder for Russia to sell its oil. I have not yet seen any overall estimate of the effect in reducing oil revenue flow. Is there one out there?

The overall figure matters, because in gas the flow continues unabated and, with European customers now paying even more exorbitant prices, Russia is benefiting from a staggering surge in revenue. According to Javier Blas of Bloomberg, at the start of the year, Russia was earning $350 million per day from oil and $200 million per day from gas. On March 3 2022 Europe paid $720 million to Russia for gas alone.

Below, Russia's 2021 income from its EU export of gas not listing its income from our import of Russian oil. If we would not buy this Russian pipeline gas & oil, Moscow couldn't easily divert the enormous volumes to other markets. It lacks an alternative transport infrastructure. pic.twitter.com/6zwGhJTYnT

— Andreas Umland (@UmlandAndreas) March 5, 2022

Unless the oil revenues have collapsed, any self-sanctioning effect is likely to have been more than offset by the huge surge in gas prices.

Sanctions clearly are biting, however. And the central bank measures are the most decisive so far. As Florian Kern of the Dezernat Zukunft, the macrofinance think tank in Berlin, spells out in this brilliant thread, BOTH Russia financial claims AND its gold are effectively inaccessible at this time. In a war, there is no “outside money”.

Zoltan Pozsar is one of the world’s most respected money market specialists and predicted the repo crisis in September 2019. Here he is getting it wrong, as he misses key aspects about the gold market and MoPo implementation in his analysis (1/18)

— Florian M. Kern (@FlorianMKern) March 3, 2022https://t.co/V7dzBiHmbM

The sanctions on the central bank have effectively forced the imposition of an exchange-control regime in Russia. A non-exhaustive list of measures taken so far includes

(1) Fees on exchange transactions: up to 30% commission according to Jack Cordell.

(2) “Blocked” rouble accounts into which Russian debtors repay their foreign loans without the debt service being transferred. (Very reminiscent of 1920s and 1930s Germany).

(3) $5000 per month limits on conversion of rouble into western currencies.

Would love to know of more, if someone has a complete list.

This tweet from the arch Brexiteer Rees-Mogg was unintentionally revealing about where Russian wealth was most concentrated before the crisis. British talk about money laundering aside, the City of London is doing its thing as a global financial entrepôt.

The City of London leads the way in the effects of sanctioning Russian banks. pic.twitter.com/WAgFV64ghy

— Jacob Rees-Mogg (@Jacob_Rees_Mogg) March 5, 2022

On top of official sanctions , self-sanctioning by Western firms are leading to a cut off of services and supply in many critical areas. We should no doubt expect this to escalate, “tit for tat” (though there is clearly no equivalence in the means at the disposal of the two sides).

Asset freezes of the respective counties’ businesses might be the natural next step of Russia’s counter-sanction. https://t.co/zwAnGWQDt7

— Elina Ribakova(@elinaribakova) March 6, 2022

In Chartbook #91 I raised the question of how far Russia might be able to offset these blows to the home front through a more creative, expansionary economic policy. In researching that question I stumbled on the fact that the “MMT”-meme had in fact been part of the policy debate in Moscow in 2018-9 and at least one of Putin’s key advisors played a role in instigating that debate.

My two favorite responses to #91 were by Daniela Gabor (great thread on the options for the developmental state)

fascinating @adam_tooze on whether we'll see Russia abandon its Wall Street Consensus macrofinancial regime – fiscal austerity, floating exchange rate, domestic bond finance – that it deployed to accumulate a foreign reserves war chest. https://t.co/qoIdmDah2y

— Daniela Gabor (@DanielaGabor) March 4, 2022

And, Nick Trickett, an essential follow, who gives a brilliant, downbeat analysis of the realities of Russian fiscal policy.

Some thoughts on the latest @adam_tooze chartbook regarding MMT and Russia. Needless to say I’m happy that’s where the conversation is turning given it was a bugbear of mine throughout COVID just how much fiscal space the regime had and yet refused to make use of.

— Nick “in media MinRes” Birman-Trickett (@ntrickett16) March 4, 2022

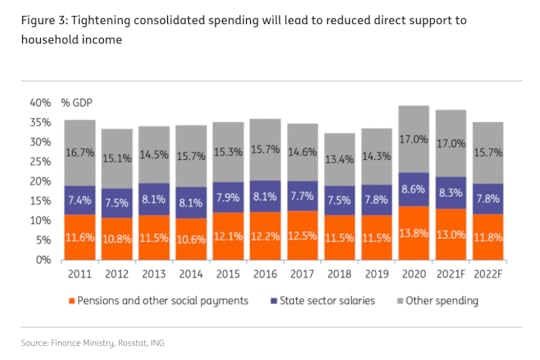

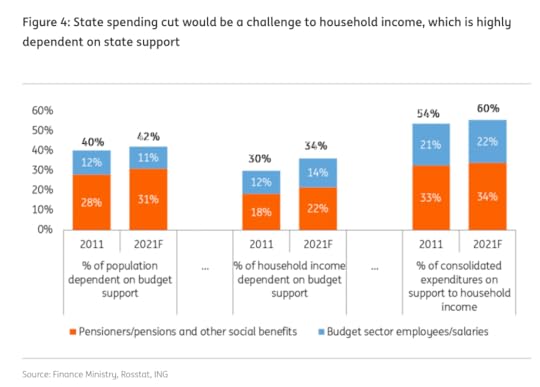

In part, my speculation about unchaining a Keynesian/MMT response to the shock in Russia was driven by reading Dmitry Dolgin’s analysis of the Russian economy at ING. His analysis often draws on rather interesting data on the share of Russian budget and household incomes that derives form state sources.

What fiscal measures have the Russians actually taken so far? Alex Nice is running an outstanding thread on the economic side of the conflict. He catalogues a list of fiscal measures and indexation of pensions etc. Predictable stuff. No Russian Rescue Plan so far.

159/ Duma passes packet of anti-crisis measures in a day, following the Covid playbook: moratorium on business checks; capital amnesty; powers to ministers to give biz support and increase social payments; Rb1trn from Wealth Fund used to buy gov debt… https://t.co/kGyNCjgtc6

— Alex Nice (@AlexNicest) March 4, 2022

If ideology does not get in the way and the Russian state has the capacity through its reformed tax system to deliver a boost in nominal incomes to a large slice of the population that may offset some of the immediate hurt from sanctions. Think of the effect of stimulus checks in the US during COVID. A fair portion wasn’t spent. Couldn’t be spent. But the checks made people feel less insecure and helped them pay down credit card bills.

Clearly, however, if supply constraints are massively binding that will limit the effects you can achieve even with an active monetary and fiscal policy. More money won’t save your military sector from running out of vital components (as emphasized by Yakov Feygin) and it wont keep your airplanes in the sky if you don’t have the parts. So how bad will the squeeze be?

Production of complex goods with international supply chains – such as cars, planes etc – will be virtually impossible in Russia in the coming months. Russia's industry is coming to a standstill. It would be easier if Russia was a petrostate, but it isn't. https://t.co/0rkayvhEID

— Janis Kluge (@jakluge) March 3, 2022

This thread on the weaknesses of the Russian economy from the highly knowledgeable Kamil Galeev acquired huge momentum online.

Russian economy is super fragile. It's critically dependent upon the:

— Kamil Galeev (@kamilkazani) March 4, 2022

1. Export of natural resources

2. Technological import

It has always been so. That's why Russia could never win a major war without massive economic help of the West. Without Western allies Russia's doomedpic.twitter.com/0HEe4tnYAD

There are plenty of predictions of collapse out there:

Surprising honesty from Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska on the unraveling economic crisis: "This is going to be like 1998 crisis but three times worse and will last 3 years"

— Anton Barbashin (@ABarbashin) March 6, 2022

1998 was a full-blown crisis of the Russian state and Russian society. Is this a likely scenario. JP Morgan, for one, does not think so.

LONDON, March 3 (Reuters) – JPMorgan said on Thursday it expected Russia's economy to contract 35% in the second quarter and 7% in 2022 with the economy suffering an economic output decline comparable to the 1998 crisis.

— tom balmforth (@BalmforthTom) March 3, 2022

A lot of folks pooh-poohed the JP Morgan estimate. But those kind of numbers are the kind of figure suggested by Iranian experience – and the Iranian sanctions were more comprehensive and severe and hit an economy that was more fragile. As this excellent thread points out.

1. So @adam_tooze is right that sanctions on Russia’s central bank, freezing reserves would mean a full “financial war” similar to that waged on Iran.

— Esfandyar Batmanghelidj (@yarbatman) February 26, 2022

But the financial war didn’t “cripple” Iran’s economy. There is always a structural adjustment. https://t.co/giC1eI5h5k

The FT’s analysis of the impact of sanctions on Iran also refuses the apocalyptic reading.

Iran is still completely cut off from the world’s financial system, including the Swift payments network that now excludes some Russian lenders. Its economy has suffered significantly. IMF figures suggest that gross domestic product per capita sank 15 per cent across 2018 and 2019 and that Iranians will not regain 2016 levels of living standards until at least a decade later. Inflation, which hit 48 per cent at the end of 2018, is forecast to remain well above 25 per cent. But in a sign of the potential impact on Russia, Iran’s oil exports to friendly countries continue and the economy has not collapsed after decades of restrictions. Supermarket shelves are usually full, and petrol stations rarely suffer fuel shortages. Wealthier Iranians, many of whom have political ties to the leadership in Tehran, have maintained their luxurious lifestyles. “With a nuclear agreement, Iran can have 15 per cent economic growth,” said Saeed Laylaz, an Iranian analyst. “Without an agreement, if oil prices remain high and Iran can continue to sell 1mn barrels a day [of oil] or so, and with rises in taxation, it can run the economy and have [modest] growth.”

Why these numbers matter is brought home by this excellent thread on oligarchic politics by University of Toronto’s Olga Chyzh. If we are talking about power politics there are TWO questions that matter – the size of the cake AND how it is distributed.

The bottom line: The current sanctions decrease the size of the pie, but the pie is still very large and Putin’s ability to distribute it is intact. No other candidate would guarantee a similar distribution to the current players. 20/

— Professor Olga Chyzh (@olga_chyzh) March 5, 2022

On the politics of the “oligarch” group, Max Seddon Moscow bureau chief of the FT did a great thread, which concluded as follows:

This list shows you how much Kremlin Inc has changed since Putin came to power. You'd only call a handful of these guys, like Yevtushenkov, oligarchs in the classical sense. A lot of them are state company bosses with KGB pasts like Akimov and Sechin

— max seddon (@maxseddon) February 24, 2022

March 5, 2022

Chartbook #92: “So like us” – Africa and the Russo-Ukrainian war

This arresting and mysterious image is one of many captured by Reuters photographers in Ukraine. Check out this amazing gallery

It adorns the mast head of the remarkable tracking project “What the Russia-Ukraine war means for Africa”. Mounted by Africa Policy Research Institute. On trying to get a handle on the impact of the war in Ukraine on Africa, I am also following this fantastic thread by David McNair.

The breadbasket of the world is at war. What are the aftershocks for Africa? A

— david_mcnair (@David_McNair) March 4, 2022

David McNair is ED for global policy at ONE, “a global movement campaigning to end extreme poverty & preventable disease by 2030, so everyone, everywhere can lead a life of dignity and opportunity”.

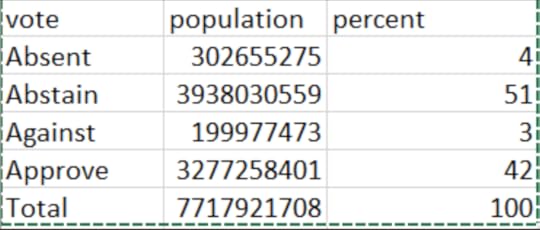

At the UN vote condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on March 2, 141 countries voted in favor, 4 against and 35 abstained. Those numbers are deceptive, however, because of which countries were in each camp. Though the motion to condemn Russia had an overwhelming majority, weighted by population the vote looked different. Of the 7.7 billion people represented by governments taking part in the vote, only 42 percent were from countries approving the motion condemning Russia. Governments representing 51 percent of the world’s population abstained.

Source: David McNair

The group of abstainers was led by China and India, who make up the bulk of these numbers. But half of the 35 states that abstained were African. Syria and Eritrea were in the handful voting with Russia to reject the motion.

African countries will face pressure to take sides. A UN resolution condemning Russia’s actions passed with 141 countries voting in favour.

— david_mcnair (@David_McNair) March 4, 2022

Half of the 35 that abstained were African inc. Mozambique, Senegal, South Africa, Uganda & Zimbabwe. https://t.co/FbEubEgI83

Many important African states assertively criticized and condemned Russia’s aggression. In a truly remarkable statement to the UN, Kenya’s ambassador Martin Kimani linked post-colonial African and post-Soviet European experience. It’s a truly remarkable intervention that really ought to teach lessons to Europe.

As Quartz reports:

In a statement to the UN Security Council at an emergency meeting on Feb. 22, Kimani criticized Russia for seemingly prioritizing ethnic self-determination over the pragmatic acceptance of borders. Many of Africa’s borders were created arbitrarily by colonial powers, he pointed out, but most countries chose not to dispute them because of the possibility of years of bloodshed. “Kenya, and almost every African country, was birthed by the ending of empire,” he said. “Our borders were not of our own drawing. They were drawn in the distant colonial metropoles of London, Paris, and Lisbon with no regard for the ancient nations that they cleaved apart.” “Rather than form nations that looked ever backward into history with a dangerous nostalgia, we chose to look forward to a greatness none of our many nations and peoples had ever known,” he continued. “We chose to follow the rules of the OAU [Organization of African Unity] and the United Nations charter, not because our borders satisfied us, but because we wanted something greater forged in peace.”

However, not everyone chose to follow Kenya in condemning Russia’s aggression.

The list of the abstaining countries included South Africa, Senegal, Mozambique, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Resolution ES-11/1 adopted. pic.twitter.com/P9HcvxfvMf

— UN GA President (@UN_PGA) March 2, 2022

The vote is a marker of ties to Russia that go back to the Cold War. In this sense the abstention by Zimbabwe, Mozambique or the ANC-government in South Africa was similar to that of India.

It was not, however, just a matter of Cold War legacies. In the case of India, modern day geopolitics played a key role (India plays Russia against China and Pakistan). And geopolitics played a role in the African votes as well.

It is hardly surprising, for instance, that Mali should have abstained, given the prominent role that Wagner mercenaries are playing in the effort by the new regime to consolidate power.

South Africa’s position also reflects present day concerns. As Bloomberg reported:

On the day the invasion began, South Africa’s foreign ministry urged Russia to immediately withdraw its forces and respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity. A day later, Ramaphosa took a different tack, saying U.S. President Joe Biden should have agreed to an unconditional meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin to avert war, and called for dialogue.

Kenyan political activist Nanjala Nyaboka said on Twitter. Africa bought almost 50% of its military equipment from Russia in 2015–2019, almost double its weapons imports from the U.S. and China, according to the South African Institute of International Affairs.

Russia also has a huge military presence in Africa. @LaurenBinDC shared this graphic a few days ago. Layer this map with how the UN vote went and you see a lot of correlation. The Global North doesn't have a monopoly on acting for its own self interest. pic.twitter.com/vYiUdGaZjI

— Nanjala Nyabola (@Nanjala1) March 2, 2022

Another excellent overview of the geopolitics comes from Nosmot Gbadamosi at Foreign Policy. As she reports:

Russia has been expanding its military support in Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Mozambique with advances in Mali in fighting rebels and jihadist insurgents. The second Russia-Africa summit was scheduled for October to November this year in Addis Ababa. As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began, the deputy leader of Sudan’s junta, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagolo, led a delegation to Moscow to strengthen closer ties between the two countries. (Russia has gold mining concessions in Sudan.)

Nigeria voted to condemn Russia, but there too there are worries about investment and trade. Particularly, over the future of the Ajaokuta Steel Complex

which has already cost more than $8bn over the past 40 years. However, the new sanctions Russia is facing in the light of its invasion of Ukraine are putting the project in jeopardy, experts say.

Nigerian experts and lobbyists worry that the decision to vote with the West on the UN motion might jeopardize the latest push to complete a project whose origins go back to the Cold War.

Conceived as the centrepiece of Nigeria’s industrial take-off in 1979, the first phase of the Ajaokuta project was built by Russian firm Technopromexport. The project was expected to have been completed in 1986, but due to policy inconsistencies caused by coups, this target was not met. In 1994, the Russian firm abandoned the project when it was at 98% completion, citing Nigeria’s inability to meet its contractual obligations. In 2001, Russia made moves to complete the complex. In 2004, then president Olusegun Obasanjo picked US firm Solgas Energy to complete it. The government cancelled the contract due to non-performance and subsequently handed it to Global Infrastructure Nigeria Limited (GINL), which is owned by Indian firm Global Steel Holdings.

Having resumed cooperation with the Russians on the steelworks in 2019, Nigeria may now turn to the Chinese.

Mapped like this, the conflict in Ukraine might be framed in terms of the “small world war” paradigm that Georgi Derluguian applied so productively to the Armenia-Azerbeijan war of 2020.. That conflict should not be underestimated as a link in the chain that led to Putin’s assault on Ukraine.

But, it would be reductive to treat the question simply from the point of view of geopolitical influence. It is not just governments and the play of power that are at stake here.

The presence of Africans in the midst of the crisis is striking. Thousands of Africans who were living, working and studying in Ukraine at the start of the war, have been caught up in the vast flow of refugees to the West.

It is a bitter irony that their presence was highlighted precisely by the fact that they were subject to racist exclusion by the border guards of Ukrainian and its neighbors. Otherwise, they would just have been people “like others” fleeing the war. Instead, black refugees were singled out and mistreated for breaking the frame of the unabashedly racist narrative that the refugees from Ukraine were “different” because they were “not from the third world”, were “blond and blue-eyed” and looked “just like us”.

What was lost on this commentary was the further irony that the Africans caught up in the war had not imagined themselves to be “in the Third World” either. The refugees in Ukraine – white and black – are flowing within the “global North”. Once again, Yugoslavia in the 1990s comes to mind. The flows are perhaps analogous structurally – though not in their immediate terror and violence – to those triggered by economic crises in the global North – Mexican return migrant, for example, when the US economy enters a recession.

The black refugees caught on the Ukraine-Poland border were not fleeing for their lives because they had lost their states, but because the Ukrainians were about to lose theirs. The shameful scenes of racism at the border were not inflicted on fleeing people who did not have rights, or the right to have rights. The “ordinary “procedures of racial profiling in legal passage by people of color across interstate borders were overlaid over a deregulated wartime crisis. So severe was the situation, that the diplomats of Ghana, South Africa and Nigeria, amongst others, were forced to intervene on their citizen’s behalf.

This drama was horrible, but it was perhaps to be expected. Racism at Europe’s borders is the norm, after all. What is more surprising is the sheer number of people of color in Ukraine when the war began.

By some counts it was as high as 80,000. Many of those were registered on student visas. The flow of educational migrants from many African states to Ukraine, made up a kind of middle-class migration, through which Africans seeking upward mobility enrolled in Ukraine’s education system … “just like us” in other words.

As the Globe and Mail reports:

tens of thousands of Africans are studying at Ukrainian universities, which many of them see as much more affordable than other foreign universities. There are more than 16,000 students in Ukraine from Nigeria, Morocco and Egypt alone, according to Ukrainian statistics.

As the BBC reports, the students too, not just the loyalty of the ANC and Nigeria’s steelworks, are legacies of Cold War-era globalization.

Ukraine has long appealed to foreign students, which can be traced back to the Soviet era, when there was a lot of investment in higher education and a deliberate attempt to attract students from newly independent African countries. Now, Ukrainian universities are seen as a gateway to the European job market, offering affordable course prices, straightforward visa terms and the possibility of permanent residency. “Ukrainian degrees are widely recognised and offer a high standard of education,” said Patrick Esugunum, who works for an organisation that assists West African students wanting to study in Ukraine. “A lot of medical students, in particular, want to go there as they have a good standard for medical facilities,” he added.

For the foreign students, the war comes as a catastrophic shock. Will they be able to continue their studies and recoup their investment? Or will a war in the North disrupt their upward mobility?

The war’s effects will also be felt more widely on the continent of Africa itself.

Commodity exporters will do well out of the general surge in commodity prices, triggered by the crisis. Algeria’s oil and gas exporters, for instance, look set to make a killing.

But importers may find themselves in severe difficulty.

This report about Egypt’s food situation from @michaltanchum at MEI, is dramatic.

With the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war on Feb. 24, 2022, Egypt’s food security crisis now poses an existential threat to its economy. The fragile state of Egypt’s food security stems from the agricultural sector’s inability to produce enough cereal grains, especially wheat, and oilseeds to meet even half of the country’s domestic demand. Cairo relies on large volumes of heavily subsidized imports to ensure sufficient as well as affordable supplies of bread and vegetable oil for its 105 millioncitizens. Securing those supplies has led Egypt to become the world’s largest importer of wheat and among the world’s top 10 importers of sunflower oil. In 2021, Cairo was already facing down food inflation levels not seen since the Arab Spring civil unrest a decade earlier that toppled the government of former President Hosni Mubarak. After eight years of working assiduously to put Egypt’s economic house back in order, the government of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi is now similarly vulnerable to skyrocketing food costs that are reaching budget-breaking levels.

The Russia-Ukraine war catapulted prices to unsustainable levels for Egypt, increasing the price of wheat by an additional 44% and that of sunflower oil by 32% virtually overnight. Even more troublesome, the war also threatens Egypt’s physical supply itself since 85% of its wheat comes from Russia and Ukraine, as does 73% of its sunflower oil. With activity at Ukraine’s ports at a complete standstill, Egypt already needs to find alternative suppliers. A further escalation that stops all Black Sea exports could also take Russian supplies off the market with catastrophic effect. With about four months of wheat reserves, Egypt can meet the challenge, but to do so, Cairo will need to take immediate and decisive action, which can be made even more effective with the timely support of its American and European partners.

As the Africa Report points out:

Food and transport account for around 57% of the consumer price index in Nigeria, 54% in Ghana, 39% in Egypt and a third in Kenya.

All of them will experience serious inflationary pressure as a result of the surge in energy and food prices. As the Report concludes

Africa has an overwhelming interest in peace in Europe.

And as Kenya’s ambassador Martin Kimani has so brilliantly demonstrated, it may have lessons to teach.

When the EU and African Union hosted a joint summit in mid-February that was no doubt not how the relationship was imagined. The summit was overshadowed by the crisis in Mali that betoken the unraveling of a large part of the West’s position in the Sahel. The result of the summit was another big EU initiative for investment in Africa.

At the EU-AU Summit, the @EuropeanCommiss announced a €150 billion investment in Africa. This investment could respond to climate change, support Africa’s economic development & improve Europe’s energy security. https://t.co/O6Q9JZP823

— david_mcnair (@David_McNair) March 4, 2022

The scale is big. It needs to be far larger. And how much of the 150 billion euro are actually delivered remains to be seen. The fruits of Angela Merkel’s “Marshall Plan With Africa” of 2017 were modest.

In the short-run the more immediate concern is for aid funding. When Europeans are spending their aid budgets on people “just like us”, what will happen to overseas funding? The precedent of the 2015-6 refugee crisis is not encouraging with many countries significantly reallocating aid funds to pay for refugee reception.

These costs can be counted as aid under @OECDdev rules which, as it did in 2016 during the so-called European ‘migration crisis’, could cut into European aid to Africa, which amounted to $8.9 billion from the EU, $4.6 billion from Germany and $4 billion from France in 2020.

— david_mcnair (@David_McNair) March 4, 2022

March 4, 2022

Ones & Tooze: The War on Russia’s Economy

On this episode, Adam and Cameron discuss the sanctions Europe and the United States have imposed on Russia’s economy in response to its invasion of Ukraine. The penalties are unprecedented in scope but will they bring an early end to the war? download(size: 27 MB )

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

March 3, 2022

Chartbook #91: What if Putin’s war regime turns to MMT?

Sanctions are the chosen weapon of the West against Putin’s aggression.

Rather than starting small we have gone immediately to an attack on the central bank.

In response, the Russian central bank has effectively stopped capital flows our of Russia and nationalized foreign exchange earnings of major exporters. It now requires Russian firms to convert 80 percent of the dollar and euro earnings into rouble. This helps to bolster the rouble’s value and provides a flow of foreign exchange into the country.

The “well-respected” i.e. highly conservative leadership of the Bank of Russia immediately raised rates and adopted the full array of central bank interventions that one might expect, pumping liquidity into the banking system and easing capital requirements. Reading the central bank’s website is a surreal experience – post-2008 style “macroprudential buffers” in the service of stabilizing Putin’s home front.

The question now, is how severe do we expect the impact of sanctions to be. How rapidly will they act? How will they impact Russian society and how might they change it politics?

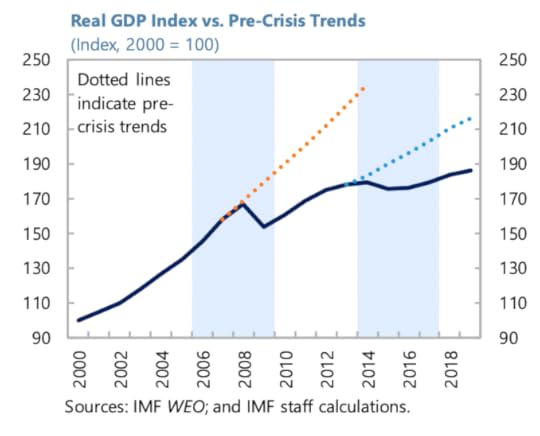

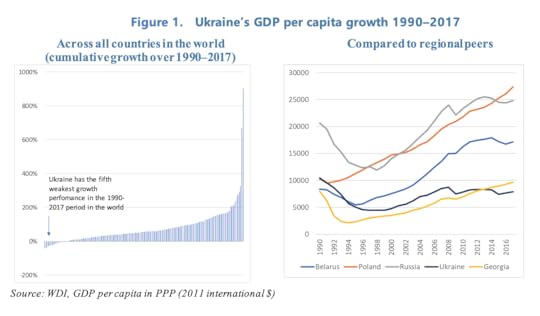

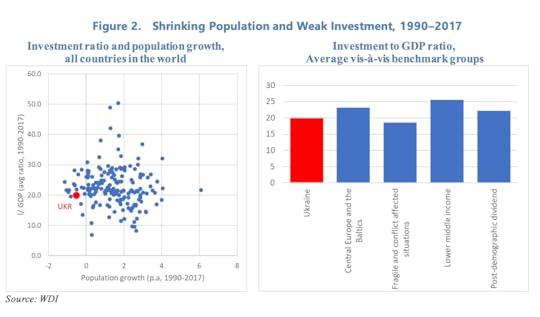

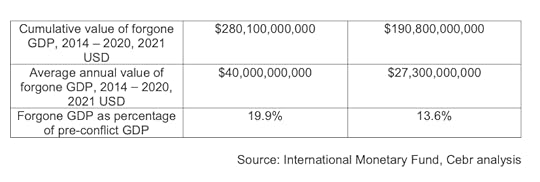

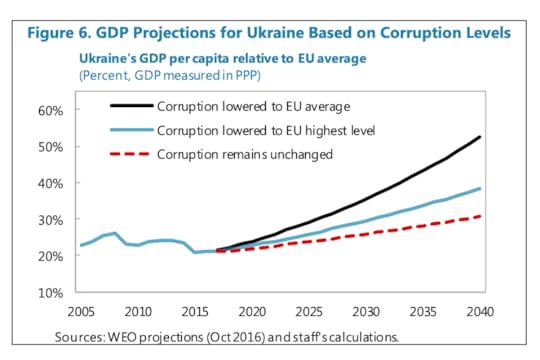

It is tempting to think about this in terms of the effects on exports, efficiency, long-term damage to economic growth etc. The outlook for Russia is surely grim. The sanctions will further worsen a growth-rate which, since Crimea, has already been depressed.

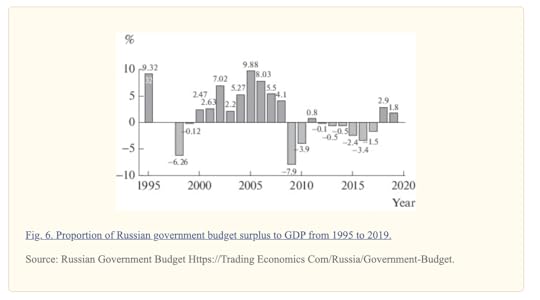

But why is Russia’s growth so poor? No doubt, sanctions, corruption, state-domination of the economy, all play a role. But, a factor that we too often neglect, is self-imposed – the draconian tightening of fiscal policy since 2016.

How rapidly would we expect a modern economy to have grown with a government budget shifting from a deficit of 3.4 percent of gdp to a surplus of 2.9 percent in a matter of three years?

Under Finance Minister Siluanov, Russia pursued a regime of severe austerity, coupled with the a free floating exchange rate and an increasing shift to a domestic bond market – the classic trifecta of the Wall Street consensus (Daniela Gabor).

By 2017 even Alexei Kudrin, the legendarily hawkish finance minister of Putin’s first decade, complained that the new regime proposed by his successor seemed “excessively severe”.

This is more than merely a point about macroeconomics.

It was commonly observed that Putin’s regime manifests a striking tension between its aggressive sovereignty and its immersion in the world economy. What is less frequently commented on is the tension between Putin regime’s “state capitalism”, which might be taken to imply freedom of action, and its rigid adherence to conservative fiscal and monetary norms. Putin is no Erdogan.

It is tempting to read the latter as the condition of the former i.e. the price for the smooth insertion of Putin’s regime into the regime of globalization – despite its aggressive diplomatic and military challenge to US hegemony – was Russia’s peerless orthodoxy in monetary and fiscal policy. If this is the case, in the current situation of open confrontation with the West should we expect Russia’s conservative economic policy regime to survive? If it does not, if Moscow puts its war economy on a Keynesian footing, what are the implications for the effectiveness of sanctions?

Already in the wake of the Crimean annexation and subsequent sanctions, Russia’s domestic policy regime was coming under internal pressure. After several years of stagnating real incomes, Russia’s economic policy elite began seriously to worry about economic growth. The new government of January 2020 came in with a growth mandate.

As Vladimir Mau, Rector of RANEPA, described the situation, in a fascinating articlepublished in 2020:

The formation of the new Russian government in January 2020, was a reflection of the society’s predominant desire to accelerate economic development. … Mikhail Mishustin’s government presented an economic transformation plan which included a set of financial, institutional and structural measures based on the national goals and national projects which the Russian President established in May 2018 …

This was a break with recent history. Hitherto, as Mau points out, Russia monetary and fiscal policy had been set without regard to the business-cycle or growth, with a focus above all on inflation and fiscal solidity. The experience of bankruptcy and inflation in the 1990s were formative. So too was the fact of Russia’s institutional weakness and the need to harden the economy against geopolitical pressures.

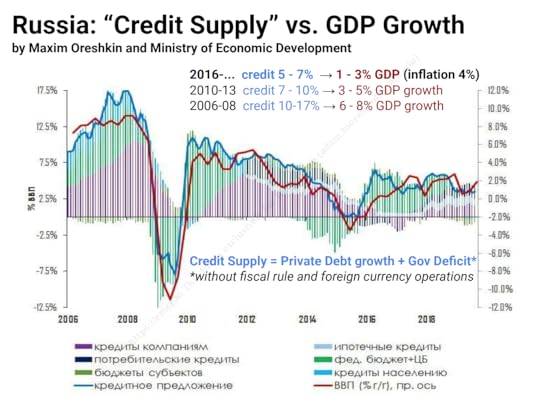

However, with all these caveats and reservations, (Mau commented in 2020), it looks like the government needs to gradually move towards a more flexible fiscal and monetary policy that would take cyclic fluctuations into account that are characteristic of a market economy. This was reflected in discussions during 2019 and 2020, concerning economic growth and the reasons it was slowing down. While institutional issues are indeed important, recent discussions on growth-related issues are increasingly focused on macroeconomic factors, primarily on supply and demand, i.e. on the sources of funding for the growth

As a result, growth acceleration was viewed mainly through the lens of fiscal stimuli and consumer lending from 2018 to 2020. National projects were to become the primary channel for the measures in question. Moreover, with inflation dropping below the 4% target and the budget in surplus, some room was left to maneuver. The issue of managing aggregate demand became highly relevant within economic policy. This was reflected in the key topics of economic discussions. These include, first of all, the nature and volume of fiscal demand.

In looking for sources to activate aggregate demand within the country, some Russian economists and politicians turned to the Modern Monetary Theory. …. Russia does not have heavy national debt and budget deficit problems. On the other hand, the ruble, though a sovereign currency, is not a global payment instrument, and economic growth is still weak. In this context, the applicability of MMT first of all means active engagement by the monetary authority to improve aggregate demand, which effectively translates to the Central Bank performing its function as an “institute for development.” This raises the issue of the Central Bank’s independent status. This problem was first raised in 2019, but the intensity of the discussion is likely to grow—not just within Russia but in other developed economies as well.

MMT in Moscow!

For some more glimpses of the debate going on in Russian economic policy at the time, check out this twitter thread

Aside of #MMT debate btw Galbraith and Rogoff @GaidarForum2020, there is another interesting event taking place in #Russia.

— Alexander Valchyshen (@AlexValchyshen) January 15, 2020

This is an appointment of new prime minister of Russian government Mikhail #Mishustin.

And this thread is my understanding of the development.

1/

The debate seems to have been kicked off by explosive interview given in October 2019 by the youthful Maxim Oreshkin, who we was then serving as Economy Minister.

As far as modern monetary theory MMT is concerned that around this history there are now many myths, there are many different speakers and all of them are trying to talk about it… but I am may be… I am, too, of cause acquainted with it. Then, what I would turn my attention to, what it seems to me correct, that colleagues says that, in reality, between private and state credit, between budget deficit and bank credit there is no big difference, in fact. And there are no, for example, such terms as equilibrium deficit of state budget or equilibrium interest rate. And that all these are determined by adequacy or in-adequacy of level of aggregate demand in the economy. And that main limit/constraint on demand is the level of price inflation. Because when inflation starts rising this in truth demonstrate that there is excess demand in the economy. Balance between budget deficit and private credit should be found from the point of view of those goals of socio-economic development that exist. And here the balance could be different for a certain country. In some countries, it may be big deficit [of gov’t budget] and there is nothing scary out of it. [Even] there is a rising public debt. If goals not connected to the rise of private credit but connected to the rise of state credit and there are no constraints to a country that has own currency [money unit of account], borrows in own currency from the point of view of [gov’t] deficit and [public] debt.

…

(Time 26:40) Question: The next question. I do not know whether Economy Minister will talk about the monetary policy. But, nevertheless I am to ask you this question. You are regularly criticizing the [Russia’s] central bank for the excessively tight stance of monetary policy…

Answer: …I will answer you right away by saying that… no, I do not do criticize [as you said] on a regular basis.

As is clear from the interview, the question of the independence of the central bank immediately arose. And the question was pointed: How could the central bank’s extremely conservative approach to inflation-control be reconciled with aspirations to more rapid growth?

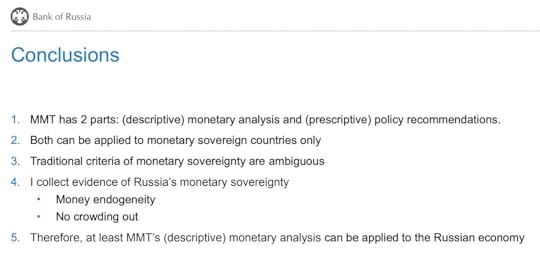

Following Mau’s lead, I have been able to find two papers dealing with MMT in the Russian context. One of them, by Vadim O Grishchenko, comes from inside Russia’s central bank.

Grishchenko focuses not on MMT’s policy prescriptions, but its description of the operation of the financial and monetary system. What he finds is that the generation of money in Russia is largely endogenous and that there is no evidence of crowding out. This is consistent with Russia being a potential candidate for monetary sovereignty in the sense that MMT suggests.

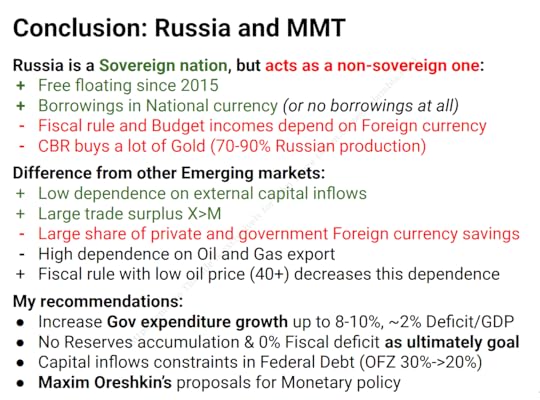

Victor Tunyov conducts a more searching exploration of the application of MMT to Russia as an emerging market economy and he does so in direct dialogue with Oreshkin’s take on MMT.

As Tunyov points out, up until the current crisis, one of the key constraints on Russian monetary sovereignty was the degree of dollarization of private accounts.

The risks, in his view was manageable.

The debate about MMT seems to have died down somewhat since 2020. The shock of COVID in Russia was severe. After the government in which he served was replaced en bloc, Oreshkin was appointed as one of Putin’s advisors on economic affairs.

In light of today’s developments Tunyov’s conclusions are truly haunting. As he put it in 2019, “Russia is a sovereign nation, but acts as a non-sovereign one”.

The current crisis has cast off any illusions on the score of sovereignty. Russia is indeed sovereign. It has violently asserted that. The question is, will it adopt an economic policy to match? Certainly with foreign exchange controls in place, questions of monetary sovereignty can be set aside for now. It is asserting an embattled sovereignty.

Here is Oreshkin on 28 February 2022 contemplating a darker future.

Elvira Nabiullina, the head of the Russian central bank, and Maxim Oreshkin, Putin's economic advisor, look like they are thinking hard about what to do with the western sanctions. pic.twitter.com/j9l2QzSBnJ

— max seddon (@maxseddon) February 28, 2022

So with these kind of arguments floating around Moscow, here is the question.

In placing so much weight on sanctions, are we not tacitly assuming that Putin’s regime, rather than using Keynesian fiscal and monetary policy to cushion the impact, will stick to the hawkish conservatism that dominated his regime’s fiscal policy up to the recent past?

If it was the rigidity of the Russian fiscal state that hitherto translated external shocks into shocks for the Russian population, what if Putin’s regime responds to its current existential crisis by adopting a more imaginative and expansive fiscal and monetary policy?

What if, within the beleaguered fortress of Russia, Putin’s regime dissolves the bind between globalization and domestic economic orthodoxy? Since it is now in an open confrontation with the West, why should Russia not use its monetary and fiscal sovereignty, reinforced by the new regime of exchange controls, to launch a stimulus program and, in so doing, negate a large part of the impact of sanctions?

If Russia has been cast into the outer darkness, what incentive does it have to uphold its orthodox reputation in fiscal matters? In a situation of direct financial confrontation with the West, markets are no longer interested in Russia’s fiscal fundamentals. If sanctions cause the ratings agencies to write Russia down to junk from one day to the next, is it surely inconsistent to expect his regime to go on playing by the fiscal and monetary rules?

The likes of Oreshkin certainly need no tutoring on the scope of action conferred by monetary sovereignty. What if Putin answers our sanctions with a “Russian Rescue Plan”? Might that negate the impact of sanctions on ordinary Russians that we are counting on to force a shift in Putin’s position?

There are others who know far more than me about the Russian policy scene. They will be able to gauge whether the Russian leadership is capable of jumping over the long shadow cast by the financial crisis of 1998 to embrace a more adventurous policy. They will be able to judge how powerful are the currents that Vladimir Mau describes in his overview.

In general, what we need urgently to debate is the “Russia model” on which our sanctions policy is based. Currently, the model is brutish and simple. Putin is a tyrant surrounded by crooks. The main idea is to “hit the oligarchs”. That plays well in the West. It may have real effects. But we should beware translating populism into strategy. The cheering in Congress for Biden’s promise to bash the Russian oligarchs was telling.

We need a more sophisticated account of Russia’s policy-making process. And we need to check our prejudices. In assuming that sanctions will cripple the Russian home front are we assuming a rigidly conservative response by Putin’s regime? That is an assumption well-warranted by the track record of Russian fiscal and monetary policy since 1998. But will it hold up, if his regime comes under real political pressure? Given the isolation we have imposed, and the controls that Russia has had to put in place, might we see a shift in Russia from a conservative deflationary policy to Keynesian stimulus? If that happens, if Moscow uses its considerable resources to cushion the home front, how then will we maintain the economic pressure on his regime?

March 2, 2022

The world is at financial war

Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s invasion has changed everything. Analysts in the West did not expect the war to go like this. They thought Ukraine would fold and that Russian forces would roll into Kyiv. Then, after the fact, the West would apply punishing economic sanctions and eventually force Russia to accept some modified version of the Minsk agreement, which was signed in 2015 and supposed to end fighting between Ukraine and pro-Russian separatists in the eastern Donbas region.

How hard they expected those sanctions to be is difficult to gauge from the lurching and seemingly haphazard manner in which the economic measures have escalated. Joe Biden’s announcement of US sanctions on Thursday 24 February was limited and clearly constrained by resistance from Europe — probably from Germany and Italy.

In any case, the crucial point is that the West expected sanctions to be delivered as punishment in a postwar situation with Ukraine crushed, humiliated and occupied. The continuity of energy supply from Russia to the US and European states is an emblem of how people expected the war to go. We would punish Russia’s crime but life would go on.

By the first weekend of the invasion that seemed increasingly incongruous. How can Europe and the US still be buying Russian gas and oil when Russia is waging this murderous, brutal and incompetent war against such a heroic, good-natured people? The brilliantly orchestrated spectacle of Ukrainian resistance has made a huge impact on global public opinion. It is yet another demonstration of the way in which battlefield events can change history, especially when relayed by TikTok.

Read the full article at The New Statesman

March 1, 2022

Chartbook #90: Heavy Fires

Gustave Doré L’Énigme, 1871

As Russian forces begin to resort to heavy artillery “fires” in their assault on Kharkiv, the character of the war in Ukraine may be about to take a terrible turn.

Except for heavy shelling around Kharkiv, use of fires have been limited compared to how the Russian mil typically operates. Sadly, I think this will change. Russian mil is an artillery army first, and it has used a fraction of its available fires in this war thus far. /16

— Michael Kofman (@KofmanMichael) February 28, 2022

In the days ahead, it is to be feared that the almost carnivalesque sense of the war as a people’s uprising against a clumsy, incompetent and oppressive enemy, will give way to something much grimmer. And that begs the question, how are we to locate this conflict in recent military history?

Is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as so often claimed, the first “big” war (in Europe) since 1945?

Clearly not. The obvious counter example to point to is Yugoslavia (1991-2001).

We tend to think of Yugoslavia in terms of atrocity and siege, or in terms of NATO intervention etc. All for good reason.

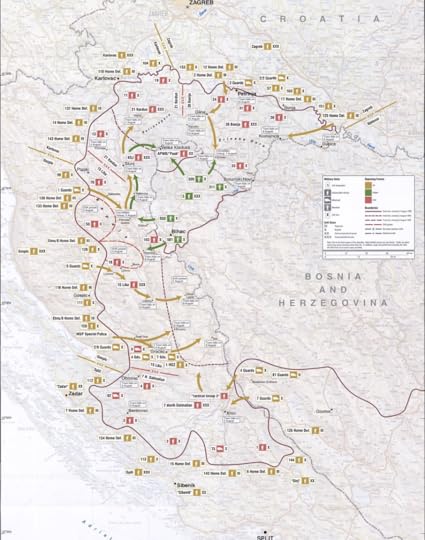

But, in some of its many phases, the war in Yugoslavia took on the form of more large-scale mobile operations, very akin to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Operation Storm unleashed by the Croat Army in the summer of 1995 was particularly dramatic. It was, at the time, the largest battle fought in Europe since World War II. Total troop strength on the Croat side came to 130,000 attacking on a 630 km frontline.

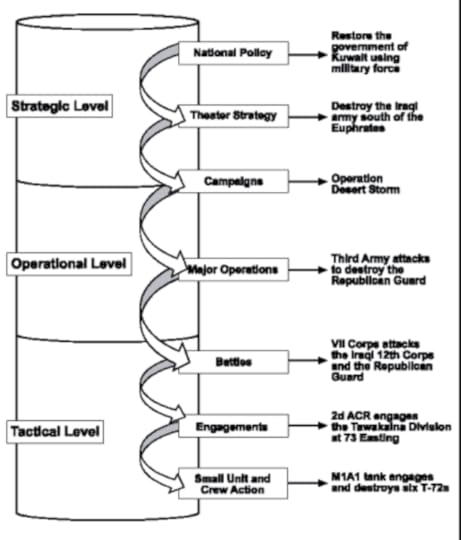

Operation Storm was war waged at what is called the “operational level” i.e. at the level of a campaign consisting of multiple interlocking battles. The Croatian army maneuvered at Corps level, i.e. in units of 30,000 men. So far you would have to say that it was vastly more coherent and effective than the Russian campaign against Ukraine.

Source: FM-3

But why restrict yourself to Europe?

For sheer scale and lethality nothing in recent history compares to the conflict in Central Africa in the 1990s and 2000s which claimed millions of lives.

But think also of the Eritrean-Ethiopian war between 1998 and 2000, which involved armies of more than a hundred thousand and well-over a hundred thousand killed in combat.

If we limit ourselves to Eurasia, we would need to consider Kuwait, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria.

In Iraq the US and its allies deployed a force of 250,000 with far heavier preparatory bombardment by aerial forces – remember “shock and awe”. Their progress in the early stages was similarly slow.

Russia's advance has been extraordinarily rapid. For comparison's sake, here are same-scale maps of 48 hours into the US invasion of Iraq and @JulianRoepcke's estimate after 36 hours in Ukraine.

— The Bazaar of War (@bazaarofwar) February 26, 2022

Anyone saying Russia is bogged down is nuts. https://t.co/X4iVuIW1Ei pic.twitter.com/U6pbpyvx8u

This animation gives an impression of how a large-scale military offensive can unfold slowly at first and then very rapidly.

For the full picture, here's the full 26 days of the Iraq invasion. pic.twitter.com/DKdzjpouEk

— The Bazaar of War (@bazaarofwar) February 26, 2022

This is NOT to say that the Russian offensive in Ukraine will follow the same pattern. But it is to warn against drawing premature conclusions from the first days of a campaign. Its logic may unfold only over time.

In the murderous campaign in Chechnya in 1999, Putin deployed a force of about 80,000 Russian troops. In the punitive expedition in Georgia in 2008, Russia deployed about 70,000 troops. Ukraine involves a force twice that size.

As one observer remarks, the last time we saw heavy Russian Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS) in use prior to Kharkiv was in Syria in 2018.

What appears to be a very clear cluster munition strike. Haven’t seen this kind of footage since the siege of Douma in 2018. https://t.co/rFCSxcBNhm

— Nick Waters (@N_Waters89) March 1, 2022

It is striking that in Ukraine these horribly imprecise, terrifying and devastating weapons have been employed sparingly so far. Back to the legendary BM-13 Katyushathey have been seen a staple of the Russian way of war.

Medium-sized wars

In any case, the post-Cold War period is not one characterized only by small-scale irregular conflict, fundamentalist insurgencies and the like. It has been punctuated by the explosion of wars involving substantial contingents of regular troops numbering between 50 and 200,000 strong.

It has been an era of “medium-sized wars” – forgive the phrase.

Size matters because it tells us something about the parties to the conflict and the relative scale of their commitment. What we have not seen since 1989 is anything like total war waged by any of the countries that might be considered major powers. Smaller and poorer states have waged something akin to total war. None of the G20 has.

For Russia and the United States, the size of the wars they have been involved in allows the conflicts to be defined as acts of policing, for the purpose of eliminating WMD, regime change, disarmament or “denazification”.

The justification may or may not be plausible. But the fact that the war can be carried by limited numbers of troops means that the rationale for the war does not need to be put to the test of broader public opinion. These are “wars of choice”.

This term is usually applied to the decision-makers. But the idea of a war of choice also extends to the home front.

As a civilian in one of the large states involved in a war of choice, you do not have to be involved. It is a matter of political conviction, career or lifestyle. Very different, of course, for those in the country made into the battlefield, whether it be Iraq, Afghanistan or, now, Ukraine. They are subject to all-encompassing and annihilating destruction, as Grozny was in 1999-2000 and Kharkiv and Kiev may be soon.

What did Russia spend in Syria?

In recent decades, Russia has been involved in at least three of these limited, “medium-sized” conflicts – Chechnya, Syria, and now Ukraine. This is not to mention its military engagements in Abkhazia, Transnistria, North Ossetia, Tajikistan, Dagestan and Georgia.

For its involvement in Syria, thanks to the liberal opposition in Russia, we have particularly detailed estimates of the cost, allowing us to gauge quite precisely the extent and the limits of the commitment.

The intervention in Syria through which Russia rescued the Assad regime cost Moscow at its height about a billion dollars per year (at exchange rates prevailing in January 2021). One can itemize the cost down to individual intervention. Air strikes per sorti by a Russian aircraft are costed about $75k. A cruise missile strike is closer to $1m. Families of Russian soldiers killed in Syria received the equivalent of $40k each.

To put this in perspective, all told according to one very useful summary by Nikola Mikovic of work by Novaya Gazeta

over the past 20 years the Kremlin spent $609 on geopolitics, including $224 billion for various energy projects, $270 billion to support its former and present client states, as well as $116 billion for debt relief. Critics could argue that it is nothing compared to what the US, the European Union and the United Kingdom have spent attempting to maintain the narrative of being global powers. However, unlike modern Russia, the Western powers are known for investing money in wars and regime changes, but at the end they almost always benefit from such operations.

According to Novaya Gazeta’s analysis, Ukraine has always been a key priority of Putin’s geopolitical spending.

Russia, on the other hand, invested at least $39 in Ukraine until 2014, according to Novaya Gazeta analysis, including $3 billion loan that Kiev openly refuses to pay back. Since the former Soviet republic effectively stopped being in Russia’s sphere of influence after the Maidan events, the Kremlin has no mechanism to force Ukraine to make a repayment.

Russia’s “investment” in Ukraine came in the form of loans and energy subsidies to Ukraine. It is grotesque to bring this up at this moment, but it shapes Russia’s contemptuous view of Ukraine as an ungrateful and unreliable puppet state.

It also helps to put in context, Russia’s engagement in supporting the breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk regions in Ukraine. In 2021, it was estimated that they were costing Moscow c. $6 billion per annum.

The long struggle in Ukraine

Pointing to that backdrop is crucial, because it is clearly misleading to think of the battle in Ukraine as starting last week. This was the point made repeatedly by Ukraine’s government over the last twelve months.

The war we are witnessing is not a “war scare” gone wrong but a spectacularly violent escalation of a long war of attrition. Ukraine has been involved in a shooting conflict with Russia since 2014 and in that conflict, whether the West recognized it or not, both Russia and the Ukrainians themselves, saw Ukraine as a proxy of the West.

On this count I found this Vice film from the frontline in Ukraine with commentary by Matthew Rojansky very compelling.

Similarly stark is the warning by Fiona Hill in this Politico interview.

We are already in a hot war over Ukraine, which started in 2014. People shouldn’t delude themselves into thinking that we’re just on the brink of something. We’ve been well and truly in it for quite a long period of time.

How did Ukraine’s military get so competent?

Which begs the question, how did Ukraine’s military become capable of withstanding the kind of assault we have seen so far?

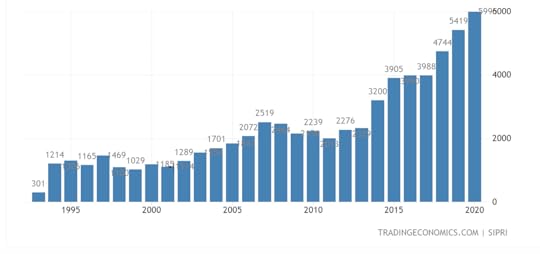

One simple way to index Ukraine’s defense effort is to look at military spending which has surged since 2014.

Source: Trading Economics

A law passed in 2018 requires Ukraine to spend at least 5 percent of GDP on security service. As the Congressional Research Service points out, it generally falls short. It also gives a figure of only $4 billion for budget spending in 2021. This is lower than that give by Trading Economics, but presumably this depends on exchange rates and it does not change the general conclusion of a large increase in spending since 2014.

That surge is also reflected in troop strength.

In 2014, Ukraine’s defense minister said the country had 6,000 combat-ready troops. Today, Ukraine’s army numbers around 145,000-150,000 troops and has significantly improved its capabilities, personnel, and readiness.

The overall strength of the armed forces comes to 200-250,000 troops.

Credit for this expansion must be given to President Poroshenko who despite involvement in corruption, or perhaps because of it, saw the military as a key area of state spending. It is not for nothing that he has now appeared on TV touting a Kalashnikov and claiming that it is the army “he made” that is winning the war.

Thanks to the brutal fighting against the separatists in the East, it is an army whose ranks include many with real combat experience. By 2017 Ukraine had suffered 10,00 casualties in the East.

What did NATO provide?

Already in the 1990s Ukraine was a partner of NATO and since 2014 those relationships have tightened. In 2016, NATO endorsed a Comprehensive Assistance Package (CAP) for Ukraine “to implement security and defense sector reforms according to NATO standards.” In June 2020, Ukraine became one of NATO’s Enhanced Opportunity Partners, a cooperative status currently granted to six of NATO’s close strategic partners.

NATO members provide training to and conduct joint exercises with the Ukrainian armed forces in a multinational framework.

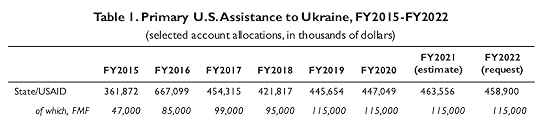

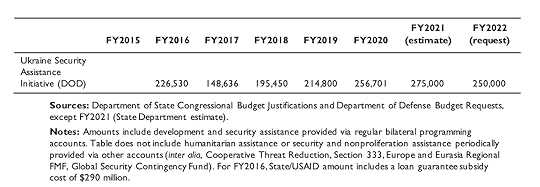

From FY2015 to FY2020, State Department and USAID bilateral aid allocations to Ukraine totaled about $418 million a year on average, of which Foreign Military Financing has recently accounted for $115 million.

Source: FAS

The Department of Defense’s Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative has recently added another $275 million for a total of about $400 million, or one tenth of Ukraine’s overall annual military spending.

In all, the Congressional Research Service estimated in October 2021 that the United States has allocated more than $2.5 billion in security assistance to Ukraine since Russia’s 2014 invasion.

From 2017 to 2021, security assistance has included not just training but assistance to

enhance the lethality, command and control, and situational awareness of Ukraine’s forces through the provision of counter-artillery radars, counter-unmanned aerial systems, secure communications gear, electronic warfare and military medical evacuation equipment, and training and equipment to improve the operational safety and capacity of Ukrainian Air Force bases.169 In 2018 and 2019, DOD notified Congress of two Foreign Military Sales to Ukraine for a total of 360 Javelin portable anti-tank missiles, as well as launchers, associated equipment, and training.170 According to media reports, these missiles were to be stored away from the frontline.171 In September 2021, the Biden Administration announced plans to provide “a new $60 million package for additional Javelin anti-armor systems and other defensive lethal and nonlethal capabilities.” 17

Famously, President Trump’s “negotiations” with his Ukrainian counterpart over the release of the 2019/2020 tranche of military aid would form a major part of his Congressional impeachment.

The US is not the only NATO partner to have been involved in training Ukrainian forces. The UK has since 2014 established Operation Orbital to support the Ukraine. And as is captured in the Vice video, there is also a US/Canada/UK/Ukraine Joint Commission for Defence Reform and Security Cooperation which was established in July 2014.

Can this smattering of aid have made the difference? It seems unlikely. As this report by David Axe of Forbes points out, though Western deliveries of Javelin’ anti tank missiles grab the headlines, the workhorse anti tank weapons of Ukraine’s army are relatively affordable ($20,000 per shot) Stugna-P rockets, manufactured in Ukraine, which have proven their worth in combat in the Donbass.

Are the Russians really as incompetent and unmotivated as our admittedly one-sided media feeds makes it seem?

It is very hard to tell at this stage. We can only rely on the best available Western expertise.

For my money the two indispensable follows on the US side, no disrespect to everyone else, are Michael Kofman and Rob Lee, both tagged in this tweet:

It’s clear from a spate of POW interviews I’ve seen the troops themselves had no idea they were going to launch this op and were completely unprepared for it, including officers. Morale is low, nothing was organized, soldiers don’t want to fight & readily abandon kit. https://t.co/hPtJGrZnR2

— Michael Kofman (@KofmanMichael) March 1, 2022

In light of their judgements, perhaps we should be less surprised than we are that Russia is bogged down and is increasingly forced to resort to massive firepower.

An analysis of the fighting in the Donbass in 2014 and 2015 by Nic Fiore of the US army highlights several fights in which Ukraine forces showed their ability to overcome the supposed material of superiority of Russian Battalion Tactical Groups.

The Clausewitzian triangle

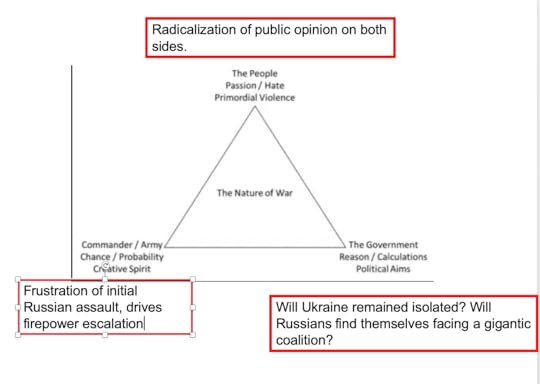

In watching the horrifying escalation over the weekend I could not stop thinking about the Clausewitzian triangle, which I had been lecturing about the previous week in my course on War in Germany.

I use a slide like this in a lecture about the Franco-Prussian war and the escalation that occurred in that war AFTER the defeat of the regular French army at Sedan on September 1-2 1870. There followed the franc tireurs conflict, the gruelling siege of Paris, the Commune, the punitive peace of Frankfurt.

The horrifying analogy to the current moment is that in seeking to end the war as quickly as possible, to avoid the further escalation of nationalist passions on both sides (which would make both definitive victory and peace elusive) and to forestall the possibility of wider international entanglement, the Prussians fell to arguing over how to apply greater pressure to the French government. The decision was to besiege and bombard Paris.

You get a sense of the argument here.

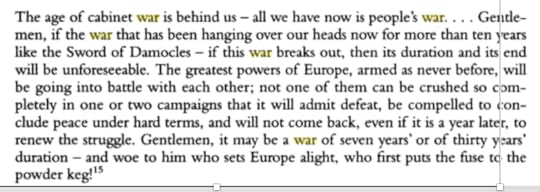

The lesson of that famously victorious war was summarized decades later in his final speech of the Reichstag by Chief of Staff Moltke on 14 May 1890:

February 28, 2022

Chartbook #89 Russia’s financial meltdown and the global dollar system.

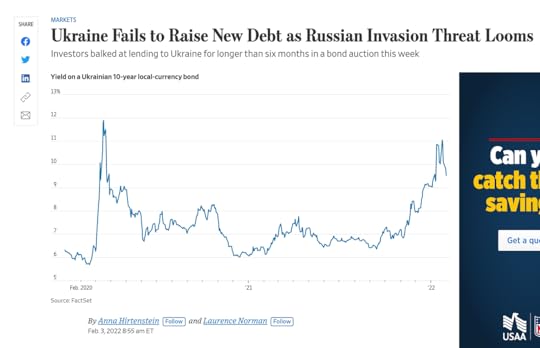

The Western sanctions on the Russian financial system announced over the weekend are doing their work on Monday. As far as Russia is concerned, financial markets are around the world have become a legal battlefield.

“There’s nothing certain in this environment. It’s not about fundamentals any more, it’s about compliance issues.”

— Katie Martin (@katie_martin_fx) February 28, 2022

or, as one fund manager put it to me: "Hoooooooooooooooooooooooo boy"

Russia sharply increases rates as sanctions send rouble plunging https://t.co/xclSgaMl5t

Already on Sunday the news was bad.

Ruble is not yet open, and might not even open on Monday. Local bank apps are quoting 150$ and ATMs are running out of cash.

— Elina Ribakova

Capital controls and massive rate hikes next (to 20%?) next. Question is if gradual or shock and awe on the already decelerating economy. https://t.co/LF2wi0VJ3R pic.twitter.com/l1hPaEKbMz(@elinaribakova) February 27, 2022

Most devastating of all was the threat to freeze the assets of Russia’s central bank in Europe. Without the central bank in support, rumors were of a collapse in the rouble by as much as 50 percent. Overnight on Sunday to Monday, in Sydney and Hong Kong international trading in rubles more or less ground to a halt. As one Bloomberg report put it:

“No trades are coming through at all on the ruble,” said Nick Twidale, chief executive Asia Pacific at FP Markets in Sydney. “When anything like this happens, we cut leverage and basically tell people to close positions. It’s just too high risk.”

The scale of dislocation is unprecedented in a market as large as that for roubles and Russian financial assets.

“The SWIFT sanctions in effect have closed Russia’s capital account,” said Peter Kinsella, global head of foreign-exchange strategy at Union Bancaire Privee in London. “This means you’re likely to end up with huge differences between offshore and onshore pricing. This is a new paradigm for the ruble.”

Anticipating the collapse, on Sunday Moscow saw panic buying of luxury goods that may have high resale value.

The operations of Russian banks in the West are under pressure. Over the weekend the ECB announced that Sberbank’s European branch was failing.

The European Central Bank took action on Sberbank Europe AG and its Croatian and Slovenian subsidiaries after determining that, in the near future, the bank is likely to be unable to pay its debts or other liabilities as they fall due. Sberbank Europe had 12.9 billion euros ($14.4 billion) of assets at the end of 2020, according to its website.

In London its listing collapsed.

The Moscow Stock Exchange is shut for now, but Sberbank has a London listing and has just collapsed 74% on opening pic.twitter.com/HMWhB0jYz3

— Robin Wigglesworth (@RobinWigg) February 28, 2022

Gazprom likewise at one point fell in London by 40 percent. How will Russia cope?

The Russian central bank has since 2008 acquired a wide range of tools to dampen stress in financial markets and limit their impact on the real economy. As Vladislav Inozemtsev put it on the invaluable Riddle website:

The Bank of Russia now has all the necessary support tools for the market (starting from the ability to allow financial institutions not to reflect losses from the revaluation of securities on the balance sheet to interventions in the foreign exchange market and provision of ruble and currency liquidity to banks).

Already on Sunday the bank announced across the board support for the financial system.

(Reuters) -Russia's central bank announces a slew of measures to support markets as it scrambles to manage the fallout from Western sanctions, including:

— Phil Stewart (@phildstewart) February 28, 2022

* Buying gold on domestic market

* Repurchase auction with no limits

* Easing curbs on banks' open foreign currency positions

It is also moving to block the exit for foreign investors, who can no longer liquidate financial assets they hold in Russia.

BREAKING – The Russian central bank has ordered market players to reject foreign clients' bids to sell Russian securities from 0400 GMT on Monday, according to a central bank document seen by Reuters.

— Phil Stewart (@phildstewart) February 27, 2022

The bank did not reply to a Reuters request for comment.

The latest report is that Russia will force companies to sell 80% of their foreign currency earnings – in other words buy rubles. This in effect substitutes private balance sheets for the central bank which is sanctioned. It is a de facto form of exchange controls.

Whether this will be enough to hold the system together only time will tell.

On Monday the first line of defense was to hike interest rates to a punitive 20 percent and put back the opening of markets until 3 pm Moscow time. All the trading up to that point consisted in Westerners unwinding exposed Russian positions.

As the FT reported:

Russia’s biggest foreign bond, a $7bn bond maturing in 2047, halved in price to 35 cents on the dollar, according to Tradeweb data. Investors said the market was extremely hard to trade. “If you see a quote on the screen it might be live or it might not,” said one. “There’s nothing certain in this environment. It’s not about fundamentals any more, it’s about compliance issues.”

The collapse of the Russian currency may have deep political implications. As Ben Judah put it, the current collapse to him was reminiscent of the

… worst day of the 1998 collapse. Gleb Pavlovsky once told me the default that followed was the “second founding of the state.” I am certain the crash we are about to see will in many ways come to be the third.

The Kremlin is not in denial about their effects

Putin will chair an emergency meeting with his cabinet and the central bank later today after sanctions “significantly changed Russia’s economic reality,” the Kremlin says.

— max seddon (@maxseddon) February 28, 2022

“These are heavy sanctions, they're problematic, but Russia has the potential to compensate the damage.”

Beyond the immediate market turmoil what are the consequences of freezing Russia and its reserves out of the global financial system?

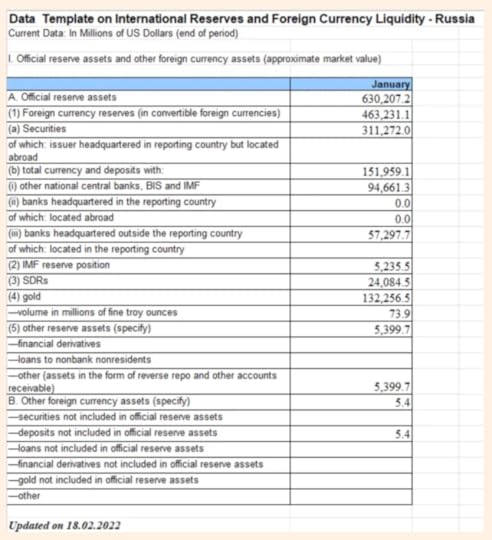

There are, at least, three ways to think of Russia’s reserve assets.

The first and most obvious way to think of Russia’s reserves is as a national strategic buffer. This is how they functioned in 2008 and 2014. When Russia’s financial system and currency come under pressure, dollars and euros from the reserve can be sold for roubles, thus propping up the value of the currency and slowing the process of devaluation, giving debtors the chance to unwind their exposure to foreign creditors and providing relief to importers and consumers.

What has changed is that the unprecedented step to sanction the Russian central bank will likely make a large part of Russia’s reserves unavailable to Russian policy makers. This is the best compilation of those reserves, from the indispensable Matt Klein.

Source: Matt Klein

The mechanics of sanctions are extremely well explained in this piece by Claire Jonesand Joseph Cotterill of the FT’s Alphaville. A must read.

The crucial thing is that reserves of euros and dollars can be put to work only by selling them in western financial markets. Those transactions require intermediary banks. And those banks can be blocked from engaging in transactions involving Russia’s central bank. To do this to a fellow central bank involves breaking the assumption of sovereign equality and the common interest in upholding the rights to property. It is a major step not easily taken against a central bank as important and as much part of the Western networks as the central bank of Russia. It was not, as far as I am aware, contemplated in 2013-14.

A second important way of thinking of the reserves is as a surplus of unspent revenue squeezed out of the Russian economy that has been deliberately throttled to generate a surplus in the hands of the state. This is the perspective that Nick Trickett highlighted in his excellent piece on “The false strength of Russia’s currency reserves”.

Seeing the reserves that way suggests that financial strength in the hands of the state will go hand in hand with weaker private balance sheets. And this will, indeed, be the test in weeks to come. How will Russian households and businesses cope?

Hard-hit banks are raising interest rates to their customers. That will apply a painful squeeze to real estate markets and indebted households.

Russia’s VTB bank – the country’s second largest which is now under heavy sectioned – will raise interest rates for new mortgages by FOUR percentage points.

— Jake Cordell (@JakeCordell) February 27, 2022

New mortgages will have an interest rate of 15.3%.

But there is a third way of thinking of the Russian reserves:

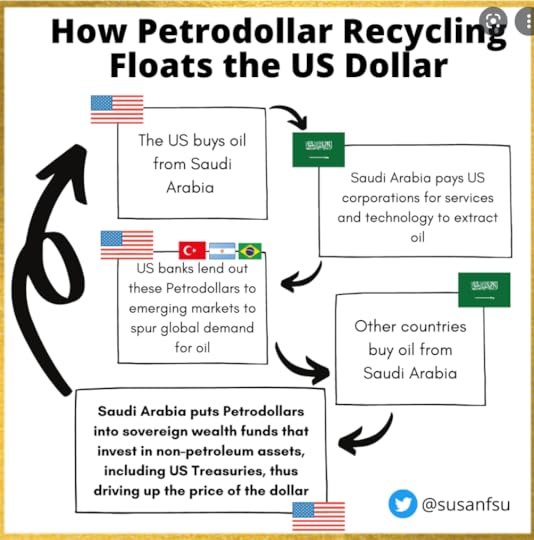

They are petrodollars. The export earnings of an oil and gas exporter. And the thing we know about petrodollars is that they are recycled. Conservative fossil fuel exporters do not simply blow the money they earn on immediate imports, they lend the money they earn from selling oil and gas back to their customers, building financial claims or, which is. the same thing, providing funding to global financial markets. Oil and gas are thus converted into a lasting stream of interest payments and dividends.

The classic model of petrodollar recycling that first emerged after the 1973 oil crisis, functioned something like this:

Source: Susan Su

The crucial point that this highlights is that Russia’s reserve accumulation, like reserve accumulation by other oil and gas producers such as Norway or Saudi Arabia, is a source of funding in Western markets. The reserves do not simply sit idly in central banks accounts, they are lent out. With sanctions, the funding provided by Russia’s petro- and gas-dollars is in jeopardy. And that impacts not only the Russians.

If you sanction Russia and thus block hundreds of billions of dollars in the global balance sheet, you have to ask yourself: what happens to the other side of the balance sheet? Reserves are Russia’s assets, they are someone else’s liabilities, who in turn has balanced that liability with an asset and so on. Those chains can be ramified and complicated.

In the 2000s like China and Japan, Russia bought US Treasuries. In effect, it became a creditor of the US government. That provoked unease on both sides culminating in 2008 in the (likely exaggerated) rumor that Russia was urging China to join it in a “bear raid” on the US Treasury market – selling US government debt deliberately to provoke a market slump.

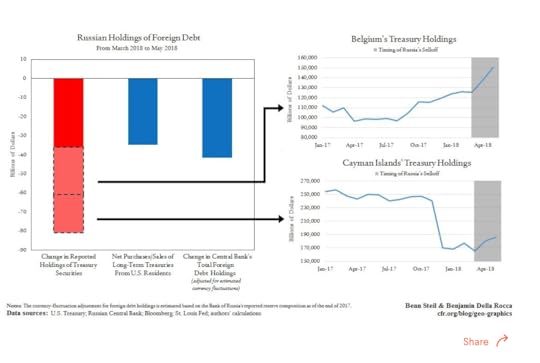

What is not disputed is that in 2018 under threat of sanctions Russia slashed its official and direct holdings of Treasuries. There are various theories as to what happened next. Where did the billions go?

One explanation offered in 2018 by forensic work done by Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca of the CFR is that the Treasuries were moved offshore, out of US jurisdictions, to holdings in Belgium and the Cayman Islands.

That seems a convincing explanation at least for the first stage. It would mean that Russia remained as a de facto creditor of the US government, just from the safety of an offshore haven.

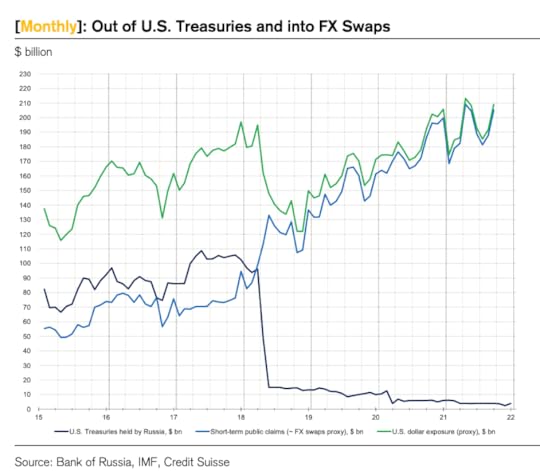

Since that first sell-off in 2018, as Zoltan Pozsar of Credit Suisse has argued in his “Global Money Despatch”, Russia’s dollar holdings have been put to work increasingly not in the market for long-term government debt, but in short-term money markets. Russia’s money was moved out of US Treasuries and into FX swaps, in which Russia lent dollars in exchange for non-dollar collateral. The Russian side of that pairing of assets and liabilities, Pozsar suggests, is what shows up in Russian holdings of reserve deposit in non-US central banks. Those are what is being sanctioned as of this morning.

Source: Zoltan Pozsar Global Money Despatch Feb 24 2022

The Russian funds in European central banks are not simply pools of money sitting idly. They are part of complex chains of transactions that may now be put in jeopardy by the sanctions.

As Pozsar puts it a large “surplus agent” has been removed from the system.

Consider for example if funds get frozen through sanctions – an event that would turn a surplus agent (Russia) into a deficit agent, which in turn would lead to missed payments, much like the onset of Covid-19 led to missed payments and turned surplus agents into deficit agents.

All told, Pozsar estimates that Russia may be responsible for providing in the order of $300 billion in funding to short-term money markets. If that funding disappears overnight it may deliver a serious shock to the Western financial system.

How serious remains to be seen, but the implication is that it is not only the Russian central bank that may come under pressure. Central banks in Europe and the Fed may need to stand by to make markets in the way that they did in 2020.

And this is true more generally for global financial markets at a time of huge uncertainty. As at the time of the COVID shock we are seeing a surge of demand into dollars, as a global safe haven.

That in turn puts pressure on everyone who has borrowed in dollars. This is a pattern we have seen repeatedly in moments of crisis since 2008: A global dollar shortage.

This is important to weigh against the speculation out there right now about the long-term impact of sanctions. Will it drive China to diversify further away from the dollar? Will alternatives to SWIFT take shape? Certainly Russia will need to get busy coming up with alternative payment mechanisms, that might run by way of the Renminbi or the Rupee.

As Ousmène Mandeng told the FT, one option would be the following:

Russia may accept payments for its exports in renminbi and increase imports paid in renminbi from China and possibly other countries accepting renminbi. As renminbi-based payments will most likely be conducted by institutions outside the immediate influence sphere of the West, this would work. … It would mean reorganising Russia’s international financial and economic relations, but that may be something it has been pursuing in any event.

But important though this shift may be, in the short-run the dollar is still king. And in the end there is only one unlimited source of dollars for the world economy, the Fed.

Never a crisis that the dollar doesn’t come out more dominant from, it seems. @DavidBeckworth https://t.co/KuKWLt98zM

— Nicholas Mairone (@nicholasmairone) February 28, 2022

So that is the next question for markets to digest. How will global demand for dollars as a safe haven, mesh with the Fed’s desire to tighten policy to counter inflation? Put the two together and you have the makings of a crushing dollar squeeze. Even before the crisis became acute there was worry about how the Fed could square the domestic priority of price stability with the stability of the global dollar system. That balancing act just got even harder.

February 13, 2022

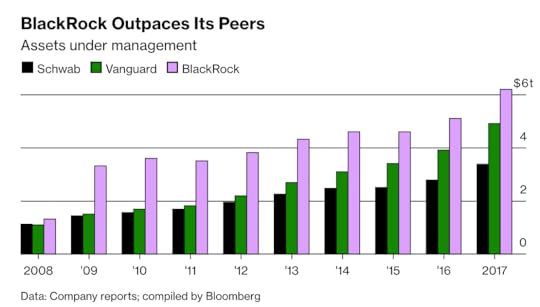

Chartbook #82: The rise of asset manager capitalism and the financial crisis of 2008

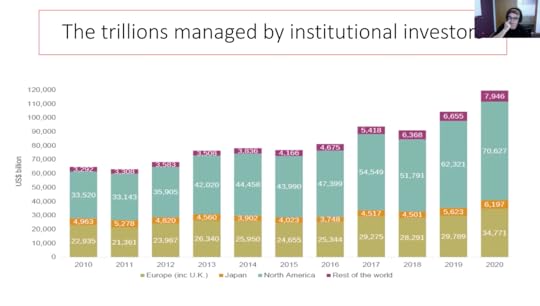

We live in a remarkable world. As of July 20 2021, three asset managers, BlackRock, Vanguard Group and State Street Corp. collectively owned about 22% of the average S&P 500 company, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, up from 13.5% in 2008.

Asset manager capitalism

My friend Prof Mark Blyth (Brown) – who needs no introduction, but is fantastic and an essential follow – gave this great short talk the other day on the theme of asset manager capitalism and inequality. It is, as you would expect highly recommended!

Mark features the work of our brilliant colleague Benjamin Braun. No that’s not a BlackRock exec, that’s Ben looking sharp! (And that’s Mark in the top right-hand corner)

Literally everything that Ben does is fascinating and his twitter account is an endless source of other good things to read. He is a great guide to the current scene in critical studies of finance etc. Here’s the description of Ben’s research on asset manager capitalism with links to two papers.

Financial capital has become abundant in the global economy. The logic of supply and demand would suggest that wealth owners and their financial intermediaries should see their structural power decline. Paradoxically, the ultimate gauge of rentier power – the gap between the rate of return on capital (r) and the rate of economic growth (g) – has proven remarkably resilient since the 1980s. Why did this gap not shrink? The guiding hypothesis of this project is that the power of wealth owners is partly a function of the organization of finance. The project studies the rise of different types of asset managers – firms that pool and manage “other people’s money” – and their impact on the economic and political determinants of the rate of return on capital. American Asset Manager Capitalism [2021] studies the rise of large asset managers in the United States and the consequences for the political economy of corporate governance. From Exit to Control [in progress] argues that the rise of asset manager capitalism means that the primary mechanism underpinning the structural power of finance has shifted from exit to control. However, asset manager capitalism differs from early 20th-century “finance capital” because unlike the banks studied by Hilferding, today’s asset management giants combine control with diversification.

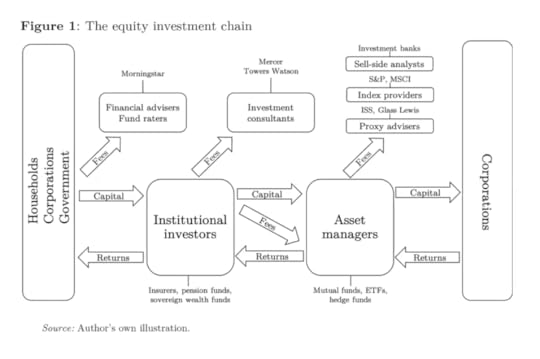

Source: Braun 2021

In this flow chart the key point to recognize is how asset managers earn their money. It isn’t through the returns of the corporations they invest in, but through the fees paid to them by institutional investors who aggregate the funds of households, corporations, governments etc. Those fees, of course, will ultimately only roll in if the asset managers earn good returns. But, if you stripped this down, the households could ultimately own the assets themselves. Adding the intermediation, advice, expertise, reduction of complexity etc etc is the key to the entire business.

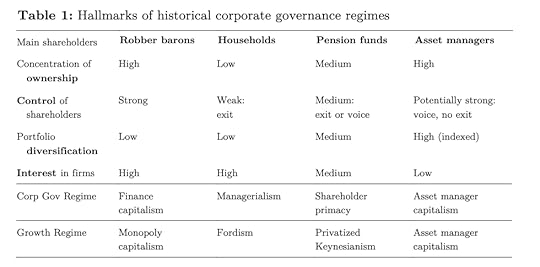

Universal Owners