Adam Tooze's Blog, page 27

January 12, 2022

Chartbook #68 Putin’s Challenge to Western hegemony – the 2022 edition.

As NATO meets to discuss the tension on the Russian border to Ukraine, and the papers fill with denunciations of Putin’s aggression, I still find it useful to return to the framework I developed in Crashed for analyzing the intersection of geopolitics and economics and the rise of Russia as a challenger. This framework consists of three basic propositions.

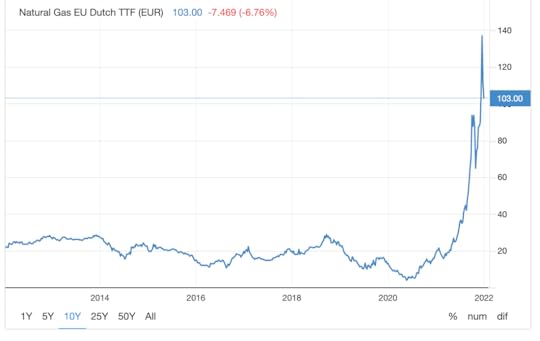

The first is that though it is tempting to dismiss Putin’s regime as a hangover from another era, or the harbinger of a new wave of authoritarianism, it has the weight that it does and commands our attention because global growth and global integration have enabled the Kremlin to accumulate considerable power. The sophistication of Russian weaponry and its cyber capacity betoken the underlying technological potential of the broader Russian economy. But what generates the cash is global demand for Russian oil and gas. And Putin’s regime has made use of this. It is reductive to think of Russia as a petrostate, but if you do indulge in that simplification you must recognize that it is a strategic petrostate more like UAE or Saudi than an Iraq, or Algeria.

Russia is a strategic petrostate in a double sense. It is too big a part of global energy markets to permit Iran-style sanctions against Russian energy sales. Russia accounts for about 40 percent of Europe’s gas imports. Comprehensive sanctions would be too destabilizing to global energy markets and that would blow back on the United States in a significant way. China could not standby and allow it to happen. Furthermore, Moscow, unlike some major oil and gas exporters, has proven capable of accumulating a substantial share of the fossil fuel proceeds. Since the struggles of the early 2000s, the Kremlin has asserted its control. In the alliance with the oligarchs it calls the shots and has brokered a deal that provides strategic resources for the state and stability and an acceptable standard of living for the bulk of the population. According to the WID-er data after the giant surge in inequality in the 1990s, Russia’s social structure has broadly stabilized.

Putin’s regime has managed this whilst operating a conservative fiscal and monetary policy. Currently, the Russian budget is set to balance at an oil price of only $44. That enables the accumulation of considerable reserves.

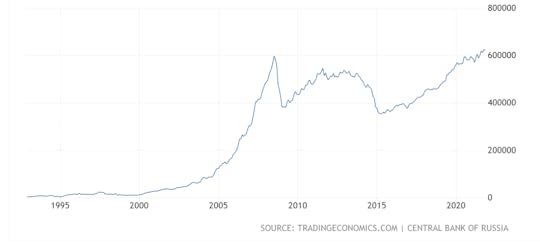

If you want a single variable that sums up Russia’s position as a strategic petrostate, it is Russia’s foreign exchange reserve.

Source: Trading Economics

Hovering between $400 and $600 billion they are amongst the largest in the world, after those of China, Japan and Switzerland.

This is what gives Putin his freedom of strategic maneuver. Crucially, foreign exchange reserves give the regime the capacity to withstand sanctions on the rest of the economy. They can be used to slow a run on the rouble. They can also be used to offset any currency mismatch on private sector balance sheets. As large as a government’s foreign exchange reserves may be, it will be of little help if private debts are in foreign currency. Russia’s private dollar liabilities were painfully exposed in 2008 and 2014, but have since been restructured and restrained.

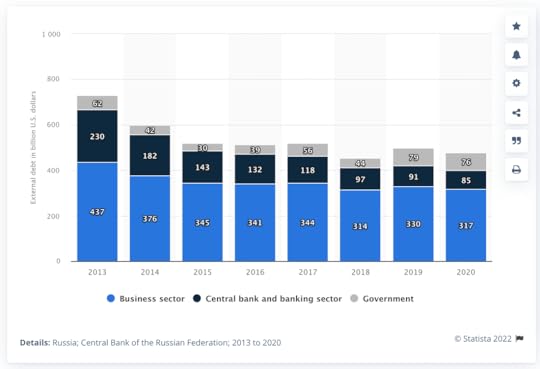

Source: Statista

According to data released by the Bank of Russia, Nominal foreign debt of banks and non-financial companies (corporate foreign debt) increased by US$6bn to US$394bn in 2Q21 (c.25% of GDP), easily covered by the foreign exchange reserves.

This strong financial balance means that Putin’s Russia will never experience the kind of comprehensive financial and political crisis that shook the state in 1998.

Nor was it by accident that it was as those foreign exchange reserves approached their first peak in 2008 that Putin began to articulate his determination to end the period of Russia’s geopolitical retreat. This is the second key element of the diagnosis.

Putin laid out his position in no uncertain terms in his sensational speech to the Munich Security Conference in February 2007 in which he outlined his comprehensive critique of Western power and Russia’s refusal to accept any further eastward expansion of NATO.

Today, China’s fundamental opposition to American hegemony articulated from within the global economy dominates the global scene. But the first to expose the fact that global growth might produce not harmony and convergence but conflict and contradiction, was Putin in 2007-8.

Putin’s stance produces outrage in the West. His assertion of Russia’s autonomy by all means necessary exposes the vanity of the post-Cold War order, that assumed that the boundary between different forms of power – hard, soft and financial – would be drawn by the Western powers, the United States and the EU, on their own terms and to suit their own strengths and preferences. The West has itself always employed a blend of strategies – financial pressure, soft power and military force – to achieve its goals. Russia’s challenge has forced a reshuffling of that pack and new combinations of diplomatic persuasion, soft power, financial and ultimately military threats and coercion. That this should be happening in Europe compounded the scandal.

The third essential point is that the consequences of this resurgence of Russian power depend on where you are and how you are set up to meet the challenge.

In Eastern Europe the crucial question is how Russia’s neighbors, whether former Soviet Republics, or former Warsaw Pact members navigated the staggering economic and social shocks of the 1990s. In this regard, Poland and the Baltics are at one end of the spectrum. They have rebounded from the 1990s crisis, have relatively high-functioning post-Communist polities and gained membership in NATO and EU in early waves of expansion. Ukraine is, in every respect, at the opposite end of the spectrum.

What makes Ukraine into the object of Russian power is not just it geography, but the division of its politics, the factional quality of its elite and its economic failure.

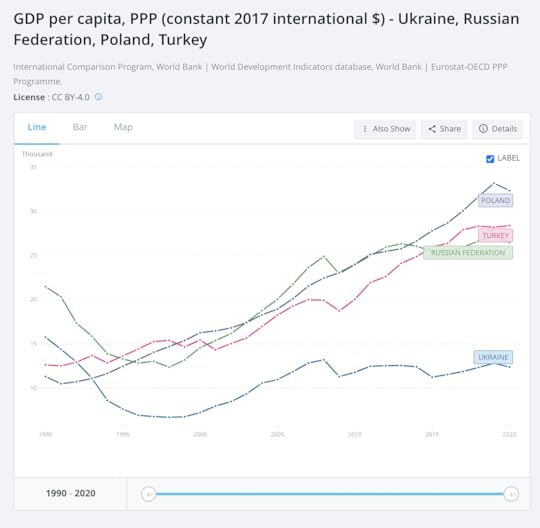

The end of the Soviet Union may have given Ukraine independence but for Ukrainian society at large it has been an economic disaster. Like Russia, Ukraine suffered a devastating shock in the 1990s. GDP per capita in constant PPP terms halved between 1990 and 1996. It then recovered to 80 percent of its 1990 level in 2007 and has stagnated ever since. Thirty years on, Ukraine’s GDP per capita (in constant PPP dollars as measured by the World Bank) is 20 percent lower than in 1990.

Source: World Bank

Ukraine’s experience contrasts sharply with that of Russian Federation which since the 1998 crisis has seen much more dramatic and sustained recovery. It also contrasts painfully with the growth trajectory of Ukraine’s neighbors Turkey and Poland.

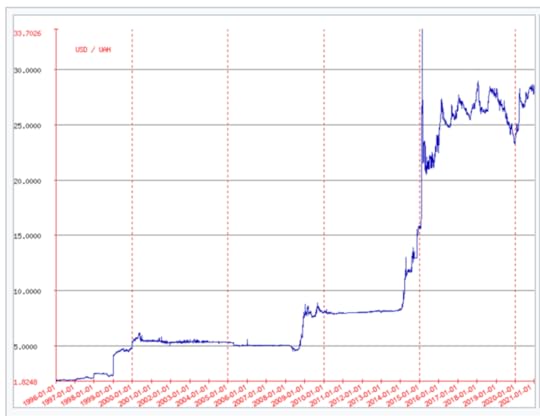

GDP per capita numbers paint a picture of painful stagnation. In addition, Ukraine’s weakness have left it vulnerable to repeated and painful foreign exchange and financial crises, best summarized by the erratic chart of the hryvina’s devaluation against the dollar and euro. There were big shocks in the late 1990s. In 2008. In 2014-5. Since 2015 the hryvina has swung around a new plateau. Given the depreciated level of the currency, in percentage terms the swings are now smaller. But Ukraine continues to be a fragile ward of the IMF.

Source: Wikipedia

Russian nationalist simply dismisses Ukraine’s claim to statehood altogether. That is propaganda. But what is clearly true is that Ukraine’e elite have not come up with a formula for delivering the material basis of legitimacy, i.e. a minimum of stability and sustained economic growth. Economic frustration compounds the divisions between regions, language groups, factional interests. Since independence, the oligarchic super-rich have played a baneful and disruptive part in Ukraine’s politics.

When President Zelensky declared after his first encounter with Putin in the talks in Paris in December 2019, “Ukraine is an independent, democratic state, whose development vector will always be chosen exclusively by the people of Ukraine”, we should bear these basic economic facts in mind. Clearly, Zelensky wished to insist on Ukraine’s sovereignty vis a vis an overmighty Russia. But if sovereignty consists in determining a development vector – which does seem like a good definition – what can one say about Ukraine’s sovereignty? At best it could be described as a desperate and so far vain search for a development model that could command the support of a majority in Ukraine.

That desperate search was made more urgent by the rising geopolitical tension announced by Putin’s speech in 2007 and by the financial shock of 2008. But it was also made more dangerous.

The basic options as discussed before 2014 were alignment with Russia, alignment with the EU-NATO or balancing between the two. Balancing between the two was the mode preferred in the 1990s and early 2000s. But by the mid 2000s in the wake of the color revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine in 2004, with both Poland’s prosperity and Russia’s ambition increasingly evident, the choices began to seem more stark.

Then in 2008, the Bush administration sought to decide the issue. It encouraged both Georgia and Ukraine to aspire to NATO membership and wrangled the other NATO members, at the NATO Bucharest conference in April 2008 into promising them membership. This confirming Russia’s worst fears. Ever since Ukraine’s politics has been torn by the scale of this choice. The worst consequences were graphically illustrated in Georgia.

Following the Bucharest NATO summit, Georgia’s ambitious leadership under President Mikheil Saakashvili concluded that to expedite NATO membership it would need to resolve outstanding issues with the breakaway region of South Ossetia. It also imagined that it had received a green-light from Washington. In August 2008, just weeks ahead of the Lehman crisis, Moscow’s massive military reaction to Georgia’s offensive in South Ossetia sent a clear and decisive message. Do not attempt to move forward on NATO’s ill-judged Bucharest commitments.

If that was not enough, economic and financial crisis in US and Europe halted any further moves in that direction. In 2008 Ukraine was immediately thrown into appealing to the IMF. Given its reliance on heavy-industrial exports, Ukraine was one of the economies worst hit by the 2008 shock.

By 2013, Kiev was desperately trying to play off IMF, EU and Russia looking for a deal. The result in 2013 was a winner takes all bidding war between the EU and Russia for influence over Ukraine’s economy. Yankukovych’s corrupt regime first encouraged its population to believe that it was swinging towards the EU. Then, faced with the niggardly European financial terms, and with a far more lucrative offer from Moscow in hand, it swung abruptly back towards Russia. That triggered the Maidan revolution. With the West hastening to recognize the revolution, Yanukovych was unwilling to stand and fight. Faced with a fait accompli Russia decided to save what could be saved. In 2014 it annexed Crimea and intervened to create Russian-backed separatist Republics in the Eastern Donbass region.

This is where the current media story typically begins: “Russian aggression against sovereign Ukraine in 2014”.

Desperate to hold the Kiev regime together, the West instrumentalized the IMF under Christine Lagarde to provide financial assistance to Kiev. This was the first time that the Fund has made a program for a country in Ukraine’s unstable condition, with an ongoing conflict on its territory. But neither the EU nor the US had any intention of backing Ukraine sufficiently to win the war in the East. Instead, the Obama administration backed away and handed off the Ukraine crisis to France and Germany. In the so-called Normandy format negotiations – amidst the eruption of the Eurozone clash with the new Syriza government in Athens and the swelling refugee crisis (the original polycrisis) – Berlin and Paris =shepherded Ukraine into the Minsk II agreement in 2015. After years of alienation (remember Snowden 2013) it was a moment of restored US-German harmony.

The Minsk agreement of 2015 is key to the current crisis. The original deal was a reflection of Russia’s massive military superiority over Ukraine but also Russia’s unwillingness to escalate to the point of full-scale invasion. The deal satisfied Russia because it promised a decentralized Ukraine with language rights guaranteed for Russian speakers. That in Moscow’s view was enough to ensure that Ukraine would not slide into the Western sphere of influence. If no progress was made on implementing the deal, Ukraine would be left in a state of frozen conflict. The ongoing conflict might not stop IMF support, but it would rule Ukraine out as a candidate for closer integration with either the EU or NATO. But it is also a painful provisorium. It is deeply unsatisfying to the increasingly nationalist tone of politics in Kiev. Moscow found itself backing the Donbass region and having to adjust to life under a sustained sanctions regime imposed by the US and the EU.

Resolving the Minsk agreement impasse is what the argument has been about since 2019 when Zelensky was elected on a peace-ticket and President Macron of France took steps to revive the process in the hope of bringing Russia out of the deep freeze.

With Trump in the White House and increasing concern about China, France did not want to persist with the status quo. An independent Franco-European diplomacy towards Russia has been a fantasy since the days of De Gaulle. Germany has continued its economic relations with Russia regardless of the Ukraine crisis, notably in the energy sector. The agreement between Gazprom, Royal Dutch Shell, E.ON, OMV, and Engie to build Nordstream 2 was signed in the summer of 2015 and though it was put on ice, German permits were issued in January 2018 and construction on the German end began in May of that year.

But moving beyond the Donbass impasse requires concessions from both sides. Russia would need to concede at least independent monitoring of elections and institution-building in the Donbass segment it controls. And Ukraine and Russia would need to agree on the ultimate goal. To satisfy Russian concerns, Minsk envisioned a high degree of autonomy for the Eastern regions. The most Kiev is willing to agree to is the incorporation of Donbass into general structure of federation which does not go anywhere near far enough for Russia. Furthermore, after years of struggle Ukrainian nationalists regard any steps towards the actual implementation of the Minks agreement in a form that would be acceptable to Moscow, as an act of treason.

So if this is the backdrop to the impasse in Ukraine, and if 2019 seemed to open a new era of engagement, what I have been trying to figure out is what explains the current escalation to the point in which since the spring of 2021 we have had two major war scares in the period of 12 months. Furthermore, these are war scares of a different order of magnitude. .

Russian military analysts will tell you the Russia has been building capability for a while so it may simply have been a matter of time before they decided to wield this instrument of coercion.But that still begs the question of timing.

It is sometimes suggested that Putin needs a war scare for domestic political purposes. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 earned him a huge popularity bump. That has dissipated. There is little evidence from Lavarda polling data to suggest that the Russian population would welcome a new war and particularly not one with Ukraine.

It is true that since 2014 the gloss has come off Russia’s economy. Putin’s regime can no longer offer a good news story of an improving welfare bargain. In 2018 it raised the pension age, further undermining morale. As analysts at the Carnegie center have remarked, the Putin-era social contract – “you provide for us and leave our Soviet-style social handouts alone, and we’ll vote for you and take no interest in your stealing and bribe-taking” – has worn thin. In the autumn elections to the Russian parliament the legacy Communist party gained strength. But, again, that hardly provides a good reason for a sudden escalation to the current level of military tension.

The more compelling logic is driven by the tensions within the Minsk compromise, Russia’s geopolitical concerns about America’s stance, and Putin’s own political clock.

Inside the Kremlin, Putin’s own timeline is crucial. In 2024 he faces a choice as to whether to continue in power or to begin to prepare his final exit. Russia could step away from the Ukraine issue. But Putin is too dug in. He wants to resolve Ukraine. This does not mean annex it. It means achieving what the struggle between 2007 and 2015 was about i.e. drawing a line on western expansion. That needs to be achieved both by consolidating a Russian veto in Ukrainian politics and driving home the message to the West not to attempt a further expansion. If 2024 is the date that is on Putin’s mind, then this overlaps with the term of the Biden Presidency. So, setting the terms of Russo-US relations on the issue as early as possible must be a priority for the Kremlin. The Biden administration has clearly signaled that its priority is China and that it is willing to pay a political price for retrenching its strategic position (Afghanistan), perhaps that opens the door in Ukraine.

Then there are internal dynamics within Ukraine. The Western media tend to treat Russia’s commentary on Ukraine as purely instrumental talk. But what if we take seriously what the Russians say? In that case what they are concerned about is something like the Georgian scenario. An over-ambitious or desperate nationalist regime in Kiev, encouraged by loose Western talk about NATO membership, attempts, through force, to reincorporate Donbass. That would require Moscow to react with massive force. Better to resolve the issue on Moscow’s own terms by making clear the vast imbalance in military power and forcing the US to engage with the diplomatic process, out-maneuvering Berlin and Paris, which Moscow regards as helpless and pro-Ukrainian.

In 2018, Putin publicly declared that a Ukrainian attempt to regain territory in the Donbas region by force would unleash a military response.

The election in 2019 election of Volodymyr Zelensky was seen as potential opening. He ran as a peace candidate. He returned to the Normandy format negotiations and Russia put a lid on any violent clashes in Donbass. But Zelensky’s popularity has collapsed. Like all his predecessors he faces a choice between Russophone opposition based in the east of the country, and the nationalists rooted in Ukraine’s west. Like all his predecessors he is trying to deliver for the electorate whilst negotiating with the IMF. Ukraine’s economic situation continues to be miserable.

The divisions within Ukrainian politics continue to be extreme, with the nationalist exerting a whip-hand. In March 2020 Zelenskiy’s chief of staff, Andryi Yermak, met with the Putin’s point man Dmitry Kozak, and agreed on a special Advisory Council in which Ukrainian officials would discuss the peace process with representatives of the Russian-backed separatist governments. On his return to Kiev, Yermak was slapped with criminal charges by the Ukrainian security services and faced accusations of treason in parliament. This confirmed Moscow’s view that nationalist zealots in Ukraine call the shots.

Meanwhile, the NATO-Ukraine issue continues to bubble.

In early December 2019 the Ukrainian parliament adopted a resolution “regarding priority steps to ensure Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration and acquire Ukraine’s full membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.”

Nor was this simply an appeal from the Ukrainian side. According to Carnegie Moscow center’s Vladimir Frolov, the moment when Moscow’s strategic patience regarding the Zelensky government finally snapped was in June 2020, when NATO decided to grant Ukraine the status of Enhanced Opportunities Partner.

This was welcomed by a representative of Zelensky’s party as follows:

Lisa Yasko, Ukrainian MP, Servant of the People Party: NATO’s decision to grant Ukraine Enhanced Opportunities Partner status is great news. The Ukrainian government has been working on this issue since autumn 2019. Earlier obstacles resulting from misunderstandings with Budapest regarding Ukrainian language policy and education reforms have been resolved thanks to fruitful bilateral dialogue with Hungary. Enhanced cooperation between Ukraine and the NATO alliance is of the utmost strategic importance for regional and global security. EOP status gives us new opportunities in Ukraine, in Brussels, and across the globe. In particular, this opens up new possibilities for the further exchange of information and intelligence, mutual training, and the participation of the Ukrainian military in NATO missions. At the same time, it is important to underline that our claim for a NATO membership action plan remains valid. With this in mind, Ukraine continues to implement reforms in the security and defense sectors. In 2020 this includes the reform of military ranks in line with NATO standards. President Zelenskyy has also presented a bill on Security Service reform. This reflects our ongoing commitment to greater Euro-Atlantic integration. Over the summer of 2020, there was talk in Kyiv of attaining the status of Major Non-NATO Ally, which would remove virtually all restrictions on military cooperation with the Americans.” That is probably the main Russian worry at this point.

As far as the Carnegie team working under Dmitri Trenin can judge, this was a crucial turning point.

Moscow, however, did not immediately move to a war footing. In the second half of 2020 it had to deal with two other major crises in its immediate neighborhood. In August the rigged presidential elections in Belarus triggered an unprecedented storm of protest. In September 2020 war broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with Azerbaijan, backed by Turkey, scoring a major victory. A fragile peace was achieved in November 2020 with Moscow acting as the broker.

Both of these crises could have provided a reckless regime in Moscow with opportunities for dramatic intervention. In neither case did Moscow push hard. In the Caucasus conflict it has adopted a balancing position. In Belarus Moscow’s aim seems to be largely defensive, to avoid what for Putin would be a Maidan-style distater. But it has not foisted on Lukashenko a complex or expensive new integration with Russia. The Russo-Belarusian integration agreement of November 2021 is an empty letter. With Lukashenko beginning to plan his exit,

the main objective for the Kremlin is to maintain a controlled, pro-Russian transition of power. It wants to prevent Lukashenko and the Belarusian elite from casting around in search of new allies and hatching harebrained schemes. Such behavior might escalate the domestic situation and prompt the EU and the United States to look for new approaches, which might again steer Belarus toward the West.

As for Ukraine, the decisive escalation in the spring of 2021 was triggered by actions taken on the Kiev side over winter of 2020-2021.

In December Ukrainian Defense Minister Andrii Taran announced that Ukraine hopes to receive a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) at the upcoming NATO summit.

He stated this at a briefing entitled “Defense aspects of Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic integration: key aspects and tasks for the future,” according to the Ukrainian Defense Ministry’s website.

“Please inform your capitals that we count on your full political and military support for such a decision [granting Ukraine the MAP] at the next NATO summit in 2021. This will be a practical step and a demonstration of commitment to the decisions of the 2008 Bucharest Summit,” Taran said, addressing the ambassadors and military attaches of NATO member states, as well as representatives of the NATO office in Ukraine.

According to him, today Ukraine’s course for full membership in NATO is enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine, and the rapid receipt of the NATO Membership Action Plan is a goal set in the recently adopted National Security Strategy of Ukraine. Taran noted that over the past seven years, Ukraine has firmly defended not only its own independence, but also the security and stability of Europe, and acts as a powerful outpost on NATO’s eastern flank.

“We believe that Ukraine and Georgia’s joining the Alliance would be the right decision for NATO. Our countries have a lot in common. These are post-Soviet republics, the countries that have been affected by Russian aggression. From our point of view, Ukraine’s and Georgia’s potential membership in NATO will have a significant impact on Euro-Atlantic security and stability, in particular in the Black Sea region,” Taran said.

2021 February, in an unexpected move the Ukrainian authorities announced severe sanctions against pro-Russian politicians and media. On February 2, Zelensky shut down three pro-Russian TV channels, accusing their owner of financing Donbas separatists. This was followed on February 19 by sanctions against Ukrainian and Russian individuals and companies on the same charges. Most dramatically, Kiev struck against Viktor Medvedchuk, who in recent years has been Putin’s only interlocutor in Ukrainian politics and is a crucial go between. Given the strong support for his pro-Russian party Medvedchuk was also a serious challenger to Zelensky in political terms.

Clearly this merited a reaction from Moscow. In direct response, Moscow unleashed the separatist forces in Donbass resulting in a surge in ceasefire violations. But intensifying the fighting in Donbass was one thing, why the full-scale military mobilization?

Here the military logistical issues may play a role. Russia has the means. But it also had the motive not simply to intimidate Kiev but to test the relationship between Kiev and Washington. It was in early 2021 that Moscow source began to refer more often to Mikheil Saakashvili syndrome. Would Zelensky attempt something similar in Donbass in 2021, in the expectation of American support?

The Kremlin does not treat Ukrainian politics very seriously. They are strongly convinced that the real force in deciding Kiev’s actions is Washington. Russia had nothing good to expect from an in-coming Democratic administration and Biden had made clear his determination to take a firm line in the campaign. The attack on Alexei Navalny and his jailing added further tension. By raising the military pressure on Kiev, Moscow would test Biden’s mettle and make clear that if the Ukraine situation was to be resolved, then Washington could not rely on Europe to deliver a resolution by means of the Minsk process.

During the crisis, Kozak, who is also the Kremlin’s deputy chief of staff, essentially repeated President Vladimir Putin’s earlier stern warning that a Ukrainian offensive in Donbas would spell the end of Ukrainian statehood. And Washington responded.

Throughout 2021 the Biden administration has walked a line between seeking a working relationship with Russia and responding to pressure to take a strong stance on what are judged to be Russian provocations. Given that the Biden administration’s clear focus is on China it is striking how much attention has been directed towards Russia.

From this initial escalation in the spring, triggered by Zelensky’s moves against pro-Russian political forces, by way of the telephone diplomacy with Biden, which led to a deescalation in April, to the June summit in Geneva, the sparring in the summer, and the reescalation of tension since August, we can retrace the steps which by November led back to an acute war scare.

On the Russian side, one significant moment in the longer-term may turn out to be the publication on 2 July 2021 of Russia’s new National Security Strategy. Even more explicitly than its predecessor document of 2015 it sets out a new and antagonistic view of the world.

On the Ukrainian side one might point to the Crimean Platform summit that president Zelenskiy opened in Kiev on 22 August, “to build pressure on Russia over its annexation of the Crimea territory, …Officials from 46 countries and blocs are taking part in the two-day summit, including representatives from each of the 30 NATO members. The U.S. delegation is headed up by Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm.”

The structure of this conflict is clear as are the routes which generate escalation. The question is, can it be resolved? Personally I am sympathetic to Anatol Lieven’s take in the Nation. Or the proposal by Thomas Graham (NSC Russia Director for George W Bush) and my colleague Rajan Menon in Politico.

Whichever route one proposes, it will be a disaster for US grand strategy if the upshot of the current crisis is a military escalation or an increase in hostilities with Russia that drives if further towards China. The Putin-Xi summit is already scheduled for the winter Olympics in February.

****

I love putting together Chartbook and am delighted it goes out free to thousands of subscribers. But if you like what you are reading and feel you can support the effort, please pick one of the subscription offers here:

January 9, 2022

Chartbook #67: In the middle of things (sic) -Hommage to Tsing’s Mushroom at the End of the World

Amongst the books that affected me most in 2021 was Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World, a study of communities of mushroom pickers in the Pacific Northwest, Yunnan China and Kyoto Prefecture, Japan.

Out of this seemingly obscure topic, out of its obscurity Tsing weaves a dizzying account of capitalist modernity. It is a study, as her subtitle has it, of “the possibility of life in capitalist ruins”.

On the second reading I was struck by the way that a book that celebrates story-telling and story-collecting, is at the same time cross-cut by a set of concepts, methodological reflection and something akin to a philosophy of history. I found it utterly fascinating. And then I realized the title that Tsing had chosen for her Part IV was “in the middle of things” (in medias res) and, well, that really set me off.

What follows are a series of quotations and short excepts from the book with brief commentary from me. To avoid any possibility of confusion I have italicized the passages from Tsing’s book.

Throughout the book, Tsing evokes musical analogies and metaphors. It is a strange, haunting, mysterious, challenging piece of music. I won’t pretend that everything about this book is totally clear to me. For me it has a poetic appeal. I find it all the more compelling for that.

***

What unites the mushroom growing and collecting communities that Tsing describes is the Matsutake, a kind of mushroom particularly prized in traditional Japanese cuisine that is highly sensitive to forest conditions and grows particularly well in abandoned/(ruined) industrial forests.

It is not a comparative study, so much as a study of interconnection, of “patches” as Tsing puts it. Implicitly, however, it is framed, as it must be, by her own position as an Asian American reflecting on the very different experience of assimilation to the US that characterized her family’s experience and that of migrants to the US arriving in the era of neoliberalism in the wake of the Vietnam war. Some of the pickers in the Oregon forests are White Vietnam veterans. There are also large communities of Cambodians and Hmong from Lao. Many of them are marked by war. But Tsing’s narrative is anchored in mid-century, in World War II.

After the War

After the war, the promises of modernization, backed by American bombs, seemed bright. Everyone was to benefit. The direction of the future was well known; but is it now? (3)

But those certainties are gone. They have evaporated since the 1970s.

Tsing challenge is to understand how we live and think the world without those “handrails, which once made us think we knew, collectively, where we were going. (2)

To appreciate the patchy unpredictability associated with our current condition, we need to reopen our imaginations. The point of this book is to help that process along—with mushrooms. (4-5)

Matsutake are a place to begin: However much I learn, they take me by surprise. (6)

Thus we arrive at her somewhat surprising question.

(W)hat kind of economy is this anyway? (4)

By way of informal mushroom gatherers we arrive at the question:

How might capitalism look without assuming progress?

Tsing’s answer: It might look patchy. (5)

… I find myself surrounded by patchiness, that is, a mosaic of open-ended assemblages of entangled ways of life, with each further opening into a mosaic of temporal rhythms and spatial arcs. I argue that only an appreciation of current precarity as an earthwide condition allows us to notice this—the situation of our world. As long as authoritative analysis requires assumptions of growth, experts don’t see the heterogeneity of space and time, even where it is obvious to ordinary participants and observers. Yet theories of heterogeneity are still in their infancy. (4)

Tsing’s is a contribution to the thinking of heterogeneity. Hence her central question: How do we know “capitalism beyond its heroic reifications”. (x)

The inspiration here is the feminist critique of political economy developed amongst others by J. K. Gibson-Graham (the pen name shared by feminist economic geographers Julie Graham and Katherine Gibson).

In approaching capitalism beyond heroic reifications we will do better not to begin with pristine nature (1st nature), or with the capitalist machine, the factory. We will do better if we start with ruins, “spaces of abandonment for asset production. Global landscapes today are strewn with this kind of ruin.” (6)

As Tsing insists, we must then also refuse the obvious temptation when confronting a ruin, to assume that they are, in fact, abandoned and dead. “these places can be lively despite announcements of their death; abandoned asset fields sometimes yield new multispecies and multicultural life.” (6)

Nor should we linger over ruins out a sense romance. We should recognize our own situation. For us, ruins are not a tourist attraction. They are our condition.

“In a global state of precarity, we don’t have choices other than looking for life in this ruin.” (6)

In an extended sense the very atmosphere that wraps around our planet, burdened as it is with our emissions, is a ruin.

History & progress

If we acknowledge our precarity, we give up the promise of a certain future but gain a recognition of a certain, limited kind of freedom.

“A precarious world is a world without teleology. Indeterminacy, the unplanned nature of time, is frightening, but thinking through precarity makes it evident that indeterminacy also makes life possible.” (20-21)

Even stating these facts is unsettling. As Tsing nicely points out, such statements take us two ways. “The only reason all this sounds odd is that most of us were raised on dreams of modernization and progress.” And on the other hand, as critical contemporaries, we also imagine ourselves free from such illusions.

“… I imagine you talking back: “Progress? That’s an idea from the nineteenth century.” The term “progress,” referring to a general state, has become rare; even twentieth-century modernization has begun to feel archaic.” (21)

But. Tsing doesn’t buy it. The categories and assumptions of progress are everywhere. “we imagine their objects every day: democracy, growth, science, hope. Why would we expect economies to grow and sciences to advance? … our theories of history are embroiled in these categories. So, too, are our personal dreams.” (20-21)

Refreshingly, she fully admits to her own unease amongst the postmodern mushroom pickers. She does not indulge in any romantic embrace of the neo-primitive.

“abandoning progress rhythms … is not a matter of virtuous desire. Progress felt great; there was always something better ahead. Progress gave us the “progressive” political causes with which I grew up. I hardly know how to think about justice without progress.” (24-25)

“I admit it’s hard for me to even say this: there might not be a collective happy ending.” (21)

Beyond specific political agendas and programs, progress is embedded in our very notions of what it means to be human. Our attachment to progress in the most general sense is what separates us from what we define as animals.

“Even when disguised through other terms, such as “agency,” “consciousness,” and “intention,” we learn over and over that humans are different from the rest of the living world because we look forward—while other species, which live day to day, are thus dependent on us. As long as we imagine that humans are made through progress, nonhumans are stuck within this imaginative framework too.” (21)

Abandoning the promise of progress is not easy. It is not virtuous. It is, according to Tsing, simply realistic.

“The problem is that progress stopped making sense. More and more of us looked up one day and realized that the emperor had no clothes.” (24-25)

The question is how to equip ourselves for this new reality.

Curiosity versus despair

One thing we need to guard against is despair. Declinism may be seductive. But, in its simple negativity, it signals a lingering attachment to its opposite, i.e. progress.

I am not proposing a story of decline. The story of decline offers no leftovers, no excess, nothing that escapes progress. Progress still controls us even in tales of ruination. (21-2)

What we need to muster are the tools and arts of “noticing” and the curiosity to notice new things that we may be able to hear, now that the pounding rhythms of progress have lost their force (24-5).

It is time to reimbue our understanding of the economy with arts of noticing. (132)

To recognize this fact and begin to come to terms with it, we need precisely to overcome our preconceptions and sense of déjà vu.

“Our first step is to bring back curiosity. Unencumbered by the simplifications of progress narratives, the knots and pulses of patchiness are there to explore.” (6)

How then are we to think this reality beyond, progress and decline?

The concept of assemblage is helpful. (22)

It is common to think of capitalism as a machine. A machine has a clearly defined purpose and a number of particular parts.

A factory is a giant machine. A plantation is designed to be a machine. It is tempting to think of all sorts of things as machines that are actually not.

Mushroom picking for Tsing is fascinating precisely because it is, in her words, the “anti-plantation” (37), the anti-factory, the anti-machine, an assemblage.

The mushroom economy, is an economy. It generates considerable value. But it is an assemblage not a machine.

Assemblages for Tsing are comings together of people and animals and things. They do not constitute firm and clear identities. They have no clearly defined boundaries. But they are powerfully productive. They are well-suited to navigating the terrain of ruins.

The time of assemblages

Interestingly, for Tsing this heterogeneous notion of an aggregate, that avoids the notion of a fixed totality, or a closed system, or a thing with clearly defined boundaries, also offers a different way of understanding time and history.

If history without progress is indeterminate and multidirectional, might assemblages show us its possibilities? (23)

So far, I’ve defined assemblages in relation to their negative features: their elements are contaminated and thus unstable; they refuse to scale up smoothly. Yet assemblages are defined by the strength of what they gather as much as their always-possible dissipation. They make history. This combination of ineffability and presence is evident in smell: another gift of the mushroom. 43

Assemblages don’t just gather lifeways; they make them. (24)

Assemblages are open-ended. They show us potential histories in the making. (23)

Thinking through assemblage urges us to ask: How do gatherings sometimes become “happenings,” that is, greater than the sum of their parts? (24)

And before your attention wanders amidst all these abstractions, Tsing brings us back to earth.

Surprisingly, this turns out to be a method that might revitalize political economy as well as environmental studies. Assemblages drag political economy inside them, and not just for humans. … Assemblages cannot hide from capital and the state; they are sites for watching how political economy works. If capitalism has no teleology, we need to see what comes together—not just by prefabrication, but also by juxtaposition. 23-24

This you might say is the metaphysics of “supply-chains”.

The polyphonic assemblage … moves us into the unexplored territory of the modern political economy. The farther we stray into the peripheries of capitalist production, the more coordination between polyphonic assemblages and industrial processes becomes central to making a profit. (24)

Categories

Assemblages defy definition. They challenge the conventional categories of social theory, modernization theory, developmental economics etc. And Tsing embraces this. It is freeing.

Her method, “follows … multiple temporalities, revitalizing description and imagination. This is not a simple empiricism, in which the world invents its own categories. Instead, agnostic about where we are going, we might look for what has been ignored because it never fit the time line of progress. (21)

But she also immediately acknowledges the problem it poses. How are we to characterize assemblages without categories?

… using category names is problematic. But not to use them is worse because then everything is alike, or everything is individually different. Both undifferentiated. 29

So what then are we to do? Forcing assemblages into categories betrays their complexity and open-endedness. They are not things.

On the other hand, not to apply categories leaves us with no way of differentiating between types of assemblages.

Tsing’s answer is pragmatic. It is a commitment to enquiry.

If categories are unstable, we must watch them emerge within encounters. To use category names should be a commitment to tracing the assemblages in which these categories gain a momentary hold. 29

And when we trace the making and unmaking of assemblages and how categories sometimes take hold, what will we find?

If we assume difference. If we assume heterogeneity and divergence, “(w)hat calls out for explanation, then, is when they happen to converge. In these moments of unexpected coordination, global connections are at work. But rather than homogenizing forest dynamics, distinctive forests are produced despite the convergences. It is this process of patchy emergence within global connection that a history of convergences can show. (206)

Scale

So we are going to set aside the noisy narratives of progress and decline. We are going to cultivate the art of noticing. We are going to listen to the stories that actors tell and we will recognize and valorize that story-telling as a method. Indeed, Tsing insists, why not make the strong claim and call” (37) this gathering of stories, “a science, an addition to knowledge? Its research object is contaminated diversity; its unit of analysis is the indeterminate encounter(s)” (37) Out of all this assemblages emerge.

But this leaves us with a problem. Stories are stories. Just that. The question is what we do with such anecdotage. Can we scale it up? Stories undeniably have the power to convey meaning, but how far do they reach?

Again, Tsing does not simply side with the anecdote, the small or the particular. Instead, she reframes the problem.

Arts of noticing are considered archaic because they are unable to “scale up” in this way. The ability to make one’s research framework apply to greater scales, without changing the research questions, has become a hallmark of modern knowledge. To have any hope of thinking with mushrooms, we must get outside this expectation. 37-8

The striking thing here is the parallelism that Tsing establishes between her object and her way of knowing it. The mushroom economy is not a machine. It does not scale. It is radically particular. And yet, it generates value. It has reach. The same is true for the knowledge that she is generating about this far flung global network of mushroom harvesting, valorization and consumption.

In this spirit, I lead a foray into mushroom forests as “anti-plantations.” The expectation of scaling up is not limited to science. Progress itself has often been defined by its ability to make projects expand without changing their framing assumptions. This quality is “scalability.” The term is a bit confusing, because it could be interpreted to mean “able to be discussed in terms of scale.” Both scalable and nonscalable projects, however, can be discussed in relation to scale. (37-8)

Scalability, in contrast, is the ability of a project to change scales smoothly without any change in project frames. A scalable business, for example, does not change its organization as it expands. This is possible only if business relations are not transformative, changing the business as new relations are added. Similarly, a scalable research project admits only data that already fit the research frame. Scalability requires that project elements be oblivious to the indeterminacies of encounter; that’s how they allow smooth expansion. Thus, too, scalability banishes meaningful diversity, that is, diversity that might change things. Scalability is not an ordinary feature of nature. Making projects scalable takes a lot of work. (38)

Tsing, by contrast, is advancing a nonscalable knowledge of nonscalability. It starts, as she says, by exposing the “work it takes to create scalability—and the messes it makes. One vantage point might be that early and influential icon for this work: the European colonial plantation.” (38)

Hence the interest of economies built on mushrooms that grow amidst the wreckage left amidst the detritus of plantation forestry, an opportunity for far-reaching but nonscaleable knowledge.

Back to the large

Does this focus on mushrooms consign Tsing to the esoteric? Does it provide only, “the view from a frog in a well?” No, she replies, “On the contrary.”

Why? Because modernity’s own account of capitalism, in the grand heroic, progressive mode is self-deluding. In fact, capitalism always operates in multiple modes. Capitalism in its development has of course, seen the gigantic development of machine-like, scalable production, distribution and consumption. But, the totality it pretends to, is never complete. It exists alongside, depends on and helps to create new models of economy that operate in salvage mode, amongst ruins in the manner of assemblages. And successive histories are layered upon each other.

“the modest success of the Oregon-to-Japan matsutake commodity chain is the tip of an iceberg, and following the iceberg to its underwater girth brings up forgotten stories that still grip the planet. … It is the very negligible quality of the matsutake commodity chain that hid it from the view of twenty-first-century reformers, thus preserving a late-twentieth-century history that shook the world. This is the history of encounters between Japan and the United States that shaped the global economy. Shifting relations between U.S. and Japanese capital, I argue, led to global supply chains—and to the end of expectations of progress aimed toward collective advancement.” (109-110)

Tsing’s provocative thesis, is that Matsutake, which hit their prime in the late 1980s and early 1990s when the Japanese boom was at its height, are a relic and evolution of the Japanese mode of merchant capitalism that transformed the world from the late 1960s onwards. They are a memento of the arrival of the “Reverse Black Ships” that “propelled the U.S. economy into the world of Japanese-style supply chains.” (110)

And again Tsing refuses any simple periodization or stage theory.

Yet it would be a mistake to see matsutake commerce as a primitive survival; this is the misapprehension of progress blinders. Matsutake commerce does not occur in some imagined time before scalability. It is dependent on scalability—in ruins. Many pickers in Oregon are displaced from industrial economies, and the forest itself is the remains of scalability work.(40-41)

And likewise it would be a mistake to fall into any easy normative assessment. The aim of her analysis is to register and analyze “scaleability and nonscaleability” free of progress narratives and their obverse. But free also of premature judgement. “it would be a huge mistake to label one good the other bad” (42). The difference is not ethics but greater or lesser diversity enabled by the imperatives of scale and the open-endedness of the assemblage. 42

Capitalism

So, we arrive at this fascinating de-reified, non-heroic description of capitalism. Capitalism is a translation machine.

In collecting goods and people from around the world, capitalism itself has the characteristics of an assemblage. However, it seems to me that capitalism also has characteristics of a machine, a contraption limited to the sum of its parts. This machine is not a total institution, which we spend our lives inside; instead, it translates across living arrangements, turning worlds into assets. But not just any translation can be accepted into capitalism. The gathering it sponsors is not open-ended. An army of technicians and managers stand by to remove offending parts—and they have the power of courts and guns. This does not mean that the machine has a static form. As I argued in tracing the history of Japanese-U.S. trade relations, new forms of capitalist translation come into being all the time. Indeterminate encounters matter in shaping capitalism. Yet it is not a wild profusion. Some commitments are sustained, through force. (133)

Part II Chapter 7 What happened to the state?

If Tsing de-reifies capitalism and seeks to release her account from the imperatives of progress narratives, the same is true for her thinking about the state.

This for her has a personal dimension. Between the arrival of Japanese Americans, who first appreciated Oregon’s mushrooms and her mother’s arrival from China after World War II, and the coming of Lao and Cambodian Americans in the 1980s. “something important has changed in the relationship of the state and its citizens. The pervasive quality of Japanese American assimilation was shaped by the cultural politics of the U.S. welfare state from the New Deal through the late twentieth century. The state was empowered to order people’s lives with attractions as well as coercion. Immigrants were exhorted to join the “melting pot,” to become full Americans by erasing their pasts.” (101) For those who arrived in the 1980s that was no longer true.

“The freedom they had endorsed to enter the United States (as anti-Communist allies of the US) had to be translated into livelihood strategies. Histories of survival shaped what they could use as livelihood skills.” (102) That is what they were living out in the forest gatherings and market-places of the Oregon backwoods: A scant notion of freedom, organized no longer around a a state, but as an assemblage.

Nor was the American state as a physical presence, any longer an effective force in organizing the forest itself. Tsing’s account of the American forestry officials she encountered could hardly be more downbeat.

Their programs, they said, were a series of experiments, and most all of them had failed. 194

Since there was no good alternative, they just kept trying. (194)

What of Politics?

Deprived of the progress narrative. With freedom occupied as a term, what is the scope for creative, constructive, “progressive” politics, amidst ruins, amidst assemblages?

This is no doubt a problem for Tsing, as it is for every observer of the contemporary scene. She offers no easy answers.

She resists any attempt to cast the forest hunter-gatherers as workers. Indeed, resisting work is a key part of their project.

The closest she comes to sketching a vision of transformative politics comes in the passages in which she describes the activities of Beverly Brown a legendary organizer who bought pickers and the Forest Services together.

It was the determinacy of political categories such as class—their relentless forward motion—that brought us the confidence that struggle would move us somewhere better. Now what? Brown’s political listening addresses this. It suggests that any gathering contains many inchoate political futures and that political work consists of helping some of those come into being. Indeterminacy is not the end of history but rather that node in which many beginnings lie in wait. To listen politically is to detect the traces of not-yet-articulated common agendas. (253)

Listening, noticing – that is the procedure.

But what are you listening for? Beyond the certainties of progress and the identities offered by categories like class, what Tsing holds out is the possibility of a “latent commons”, entanglements that might be mobilized in a common cause. But those cannot be presupposed, or projected onto a situation.

the hints of common agendas we detect are undeveloped, thin, spotty, and unstable. At best we are looking for a most ephemeral glimmer. But, living with indeterminacy, such glimmers are the political. (253-5)

Part IV in the middle of things (251)

Tsing wants us to think and act from the middle of things, a suggestion I find very appealing. I tend to think that problem temporally. We think from within the flow of time. Tsing acknowledges that and adds another dimension.

Tsing wants us to think from places, in a situated way, from and about the histories of places, as in her mushroom patches and their complex histories. Science should not be more reified than capitalism or the state.

For Tsing the concept that links thought, history and place, is disturbance. Disturbances alter ecologies. They result from actions, human or non-human. They mark differences. They are points of entry.

This part of the book begins with disturbance—and I make disturbance a beginning, that is, an opening for action. Disturbance realigns possibilities for transformative encounter. Landscape patches emerge from disturbance. 152

She is worried that her emphasis on “disturbance” will be taken to imply the prior existence of an “undisturbed” state. So she insists:

as a beginning, disturbance is always in the middle of things: the term does not refer us to a harmonious state before disturbance. Disturbances follow other disturbances. 160

And then in the final sections of the book she adds this further specification. To be in the middle of things is a matter of time. It is a matter of place. It is also a matter of people, of society.

Muddling through with others is always in the middle of things. …. it does not properly conclude. Even as I reiterate key points, I hope a whiff of the adventure-in-process comes through. (277-8)

Muddling through with others (human and non-human) is Tsing’s answer to the overwhelming, gigantic and radically anthropocentric notion of the anthropocene.

Conjunctures

But once again, as is so characteristic of her restless thought, Tsing is not satisfied with tying us to a particular place.

The hard work—and the creative, productive play—of science, as well as emerging ecologies, happens in patches. But one might also sometimes wonder: What moves beyond them, making them? (227)

A patch becomes a patch after in relation to something else, in relation to other patches. And those patches are sometimes linked, to form interconnections and conjunctures, moments of coordination (118).

Not by a giant historical frame, but by more accidental and haphazard connections.

Sometimes conjunctures are the result of international “winds,” the term Michael Hathaway uses to describe the force of traveling ideas, terms, models, and project goals that prove charismatic or forceful (206)

In a phrase I adore, Tsing describes her own role in exploring this world thus:

I work the conjunctures … (163)

I work the conjunctures. Like working the winds. And then some pages further on, by way of comfort, she adds:

Luckily, in doing so, there is still company, human and not human. (282)

Good mottos to take from an extraordinary book.

*****

I love putting out Chartbook for free to a wide and diverse range of subscribers from all over the world. It is a pleasure to write and a great place to pull ideas together. It is also, however, a lot of work. If you feel moved to support the project, there are three subscription options:

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.January 7, 2022

The Economics of the Beatles vs. the Rolling Stones

Season 1, Ep. 15

After watching the Beatles: Get Back sessions, Cameron Abadi was inspired to dive deeper into the economics of the Beatles versus the Rolling Stones with Adam Tooze. So, rock lovers rejoice, that’s what you’ll get in the second half of Ones and Tooze this week.

But first, Tooze and Abadi dig into the heated online debate over price controls. For those not following, the internet somewhat broke over a Guardian op-ed arguing that price controls could fight inflation. Tooze tempers the hysteria and looks at the historic data.

January 6, 2022

Chartbook #66: More on inflation and price controls

“The price per liter of LPG jumped to 120 tenge (28 U.S. cents) at gas stations in hydrocarbon-rich Mangystau – where up to 90% of vehicles run on LPG – at the start of this year, compared to the price of 50-60 tenge the year before, igniting the unrest.

The nearly 100% rise that doubled the prices in the oil-rich region prompted almost countrywide demonstrations. The unrest has already prompted the nation’s president to sack the Cabinet on the fourth day of the protests.” Source: Daily Sabah

Debates about price controls are getting out of hand https://t.co/daZjCYhe9a

— Max Jerneck (@MaxJerneck) January 6, 2022

Hands up anyone who predicted that we would start 2022 by discussing strategic price controls, 1971, 1946 and the crisis of the Kazakh regime.

This thread has great meme game:

The Guardian piece on price controls really triggered people. Alan Blinder wrote a famous paper on why these were ineffective in the 70s, only changing the timing of inflation rather than its magnitude: https://t.co/o7hqc76Ene

— Dario Perkins (@darioperkins) December 30, 2021

On the US situation and price controls

On the original piece by Isabella Weber on price controls that triggered this entire debate, I still like this thread by Eric Levitz and the piece it is attached to.

Jotted down a few thoughts on the burgeoning debate over price controls/other unorthodox approaches to inflation management:

— Eric Levitz (@EricLevitz) January 2, 2022

Anti-inflation tools:

For a wide ranging consideration of different anti-inflation measures, this by Buddy Yakov is excellent.

The first layer is an industrial policy designed to push forward innovative production and make sure there are sustainable supply chains for that production.The second layer is a savings and incomes policy that guarantees demand by putting a floor under consumption but also encourages households to invest in public instruments and thus put some caps on consumption.The third layer should be credit and price controls meant to tamper down on extremely volatile components of CPI.The fourth layer – the red button – should then be aggressive interest rate hikes.We are left with a huge set of tool kits to deal with prices. I like to see it as a layer cake:

The purpose of this post is to discuss some ideas for how to deal with short-term inflationary bouts to pave the way for a wage-led economy. In addition to commenting on the hikes v. price controls debate that Weber’s article has inspired, I want to propose another way – deferring consumption via public savings. This is the proposal made by Keynes during the Second World War and is also present in Adolph Lowe’s theory about how to cross a traverse toward a full-employment economy.

Inflation Management

This piece by By Skanda Amarnath and Arnab Datta of Employ America, is very interesting:

Policymakers outside of the Fed can get ahead of this scenario by proactively adopting an “inflation management” approach that better achieves its policy goals. This does not have to mean Nixonian price controls. It means that the White House and Congress should, where feasible, use targeted fiscal policies and structural reforms to equitably address the demand- and supply-side challenges that contribute to inflationary pressure.

Healthcare as a sector is unique in terms of the influence that the federal government can exert over inflationary dynamics through legislation and regulation. It also makes up about a quarter of the Fed’s preferred real-time gauge of forward-looking inflationary pressures–”core PCE.” Rent inflation is likely to contribute more substantially to inflation readings in 2022 (0.4% additional contribution according to our forecasts), but those effects can also be entirely offset with healthcare policies that current law and proposed rulemaking already favors.

Profits and Prices

For a skeptical take on the relationship between profits and prices, I quoted the fantastic piece by Joey Politano. Here is Joey Politano is being super charming and very modest.

I just have to clarify that I'm not an economist at BLS—the work I do there is financial/budgetary and I don't have a graduate degree in Econ.

— Joey Politano

I know it seems pedantic, but as a federal employee I have to be careful not to misrepresent myself.(@JosephPolitano) January 3, 2022

Thomas Philipon one of the key economists on profit-gouging weighed in here:

1/n. My take on this question of monopoly power and inflation: two things are true at the same time:

— Thomas PHILIPPON (@ThomasPHI2) January 4, 2022

1/ The proximate cause for inflation is not a sudden increase in monopoly power.

2/ High demand and inflation suggest now is a good time to crack down on monopoly rents. https://t.co/IiPuH6GpOK

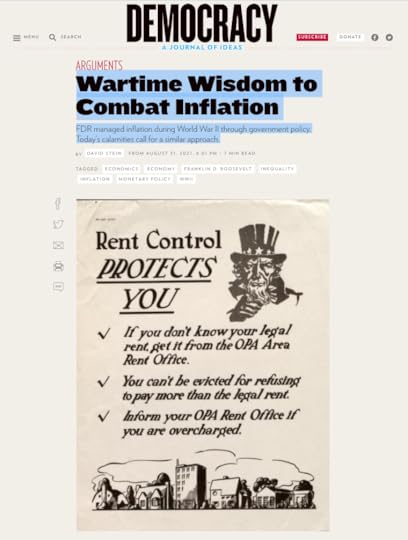

Office of Price Administration and all that

Before Isabella Weber made her case for price controls with reference to the 1940s, David Stein did something similar in Democracy Journal.

In this way, wartime frugality became an explosive political flashpoint. The rural South was outraged that preachers and ministers were not considered essential, and so Franklin Delano Roosevelt was too. He called in John Kenneth Galbraith, his lieutenant in price management with the Office of Price Administration (OPA), to ask him to ensure that ministers received their proper designation.

During World War II, pricing and production were too important to let the market bid up the cost of war material. Tires, cars, coffee, sugar—these were issues of critical national security. The size of the OPA reflected this; its staff of 250,000 was rivaled in the federal bureaucracy only by the Post Office. OPA had twice the number of economists as the Treasury Department; its decisions made front-page headlines.

Amongst historical references, David Stein cites the work by Meg Jacobs Pocketbook Politics: Economic Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America published by Princeton UP

Wirtschaftswunder

One of the discoveries for me in Isabella Weber’s interesting book about shock therapy in China was her discussion of Uwe Fuhrmann’s recent book on the hidden history of West Germany’s economic miracle.

Fuhrmann shows how much social discontent and struggle went along with the famous plans by Ludwig Erhard to introduce the Deutschmark and liberalize prices. I have to say it was news for me.

Unfortunately, the book is only available in German, but here is Uwe offering a thread in English.

The story about the German Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) was – and is – crucial for the central neoliberal narrative about the alleged self-regulation of prices through supply and demand.

— Uwe Fuhrmann (@Uwe_Fuhrmann_) January 5, 2022

But neither the narrative nor the german example matches reality: A #Thread #prices

Why price controls are a bad idea

Skip the polemics with the MMT crowd, but read this by Noah Smith through to the end.

Perhaps we do need monetary measures.

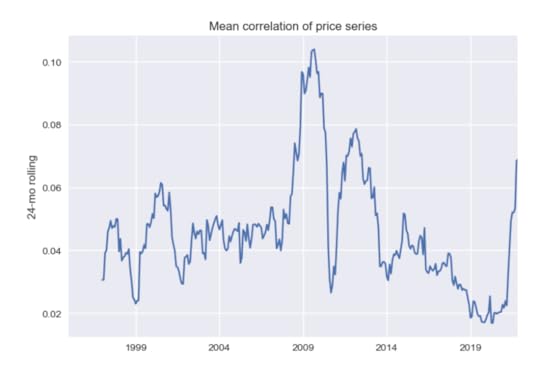

Policy Tensor thinks I am over optimistic about general inflation and therefore general, monetary measures against inflation are warranted. This graph from his post is particularly striking.

Clearly it shows a correlated upward surge in prices since 2020. But does this imply a true common cause or rather a common bounce back after a common shock?

We went back and forth on this on twitter.

Hi @policytensor thanks for taking this so seriously. I note the dramatic decline in correlation up to 2020, followed by the sudden co-movement. Is there a way of picking out the bit that is co-movement as a result of COVID-shock v. more general inflationary processes? pic.twitter.com/kbTkAbSfIY

— Adam Tooze (@adam_tooze) January 5, 2022

Forty centuries of price controls

Agree or not, the historical examples are great.

The delusion that governments can successfully manipulate prices has spanned cultures, nations and epochs.

— Peter Young (@petermiyoung) December 7, 2020

Inspired by Scheuttinger & @eamonnbutler's excellent book "Forty Centuries of Wage & Price Controls", I have catalogued my top 8 historical price control blunders.pic.twitter.com/RX7unUUyyW

And here is the thread by way of a thread reader app.

*****

I love putting out Chartbook for free to a wide and diverse range of subscribers from all over the world. It is a pleasure to write and a great place to pull ideas together. It is also, however, a lot of work. If you feel moved to support the project, there are three subscription options:

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.January 3, 2022

Chartbook #65: Inflation & Price Controls

“We have a powerful weapon to fight inflation: price controls. It’s time we consider it.”

Last week, Isabella Weber’s op-ed in the Guardian, which – on the basis of positions taken by prominent American economists in 1946 – advocates “strategic price controls” as a means to controlling profit margins and inflation, has caused quite a storm.

I’m late to the game having been on a break from social media visiting in-laws in rural Kentucky.

Coming back to twitter this week, the ugliness of the reaction to Weber’s op-ed is depressing. Perhaps one should not be surprised. But it is depressing and telling, nevertheless.

I would much prefer to discuss the substance of the issues and I will do so below. But one should not pass over the tone of this debate without comment.

When it comes to the politics of intellectual life, I’m committed to showing not telling. Chartbook is part of that effort. But given the importance of the subject matter and since my name was invoked in one widely quoted thread, forgive me for making an exception in this case.

In this kind of debate there should be no room for disrespect. Full stop. However wrong and ill-judged you may feel Weber’s op-ed to be, there should be no room for disrespect. It was good to see Paul Krugman apologizing. But the harm was done.

This is not merely a matter of etiquette, manners, or personalities. In the tone of a debate, issues of professional authority are at stake. If the personal is political, so too is the tone of a debate.

Regrettably, the aggression triggered by Weber’s op-ed is also profoundly unproductive in intellectual terms. It turned what should be a serious argument about an important issue – the means of inflation-control – into an ugly slanging match. This is not by accident. One way to shut down an unwelcome discussion is by means of fist-pounding. Another is the tantrum. In either case, the unproductiveness of the ensuing conversation is not a bug. It’s a feature.

***

Weber’s op-ed is short on substance. She does not tell us what kind of price controls she advocates, on what sectors etc. But, in fairness, the op-ed links to work that is more specific.

If you are serious about engaging in the argument, don’t focus on Weber’s 800 word squib, read it in light of her important historical work on price control politics in the West and China after 1945, which poses its own questions. And acknowledge the fact that her suggestion is not without context. It reflects a rich vein of recent post-Keynesian writing that has urged “unconventional” approaches to inflation control.

I say post-Keynesian deliberately. Tilting at MMT was another of the distractions of the price control debate on twitter.

What can we salvage from the wreckage? How can we take this debate in a more productive direction?

As Eric Levitz makes clear in his excellent write-up of the debate, whether you find Weber’s op-ed convincing or not, there is a serious position to be argued with. The effort to assert the monopoly of conventional inflation-fighting disarms us.

One could make a strong case for more stringent controls throughout the American health-care system. And price controls are themselves just one of many unorthodox approaches to inflation management. Reducing the monopoly power of price-gouging firms, channeling credit to sectors where demand outstrips supply, forcing (or strongly encouraging) workers to save a fraction of their paychecks, and direct public investment in expanded production are others.

All of these measures have the potential for negative side effects and unintended consequences. But the same can be said of raising interest rates. If policymakers reflexively presume the wisdom of conventional tools, and dismiss the potential of unorthodox ones, we will all pay the price.

On the history of price controls in the US since 1945, follow the excellent Andrew Elrod, whose PhD is going to make a major impact. Start with this thread.

Exasperating to see price controls hitting such a raw nerve in real time over the past few days on here. Guess the Cold War isn't over after all!

— Andrew Elrod (@andrewelrod) January 2, 2022

It includes this great line: “Informed debate then was never about whether prices should be controlled but who should control them.”

For a serious discussion of how price controls have actually operated in the US up to the present, check out this piece by Todd Tucker.

For post-Keynesian proposals on how regulations and price controls of various types might assist in managing America’s current inflation problems, check out the position of Josh Mason and Lauren Melodia at the Roosevelt Institute.

Having said all that, I remain unpersuaded that price controls can be an important remedy in our current situation.

***

Some are skeptical because they believe that inflationary pressure is broad-based and merits a monetary policy response.

For my part, I’m a paid-up member of team transitory, a diagnosis Weber mentions but does not seriously address. In fact, I am not just part of team transitory. I am a member of team sectoral, as well. To put a point on it, I am not convinced that the current round of price increases should really be thought of as a general inflation at all. I am impressed by recent BIS work which shows the common factor in recent price movements declining in significance. And if that is true for data up to 2019, it is all the more the case for the period since the COVID shock. Matt Klein’s breakdown of the data into COVID and non-COVID elements is highly persuasive on this score.

If one takes this approach, the question becomes which instruments might usefully address which drivers of which price increases. It is not obvious to me that either interest rate hikes or price controls in general can be of much help.

Weber starts by stressing rising profit margins as an important driver of general inflation. On that score I find the critique by BLS-financial analyst and Substacker Joseph Politano wholly persuasive. It just isn’t likely that a general surge in profit margins is doing the damage here.

Likewise, I find Politano’s breakdown of the sectoral logic of inflation highly persuasive as well as his skepticism towards price controls as a means of addressing inflation in energy prices, for instance.

There is no doubt a case for driving down the price of pharmaceuticals in the US. Rent controls may be part of housing-policy trade-off in some cities. The meat lobby has an anti-trust case to answer. But I see little advantage in packing an array of discrete measures using existing instruments under the (deliberately) provocative rubric of “price controls”.

I don’t think it is pejorative to describe the use of the term “price controls” as provocative. I take it to be the purpose of this language to provoke debate and break open the confines of conventional discourse.

But as desirable as that kind of heterodox challenge may be in general terms, we will be kidding ourselves if we imagine that such measures are a “powerful weapon” to fight the spike in prices in 2022.

Cleaving to team transitory does not imply complacency. It just implies that faced with a range of bad options we should practice restraint in adopting any anti-inflationary policy, whether that involves monetary policy, regulatory policy or fiscal policy.

***

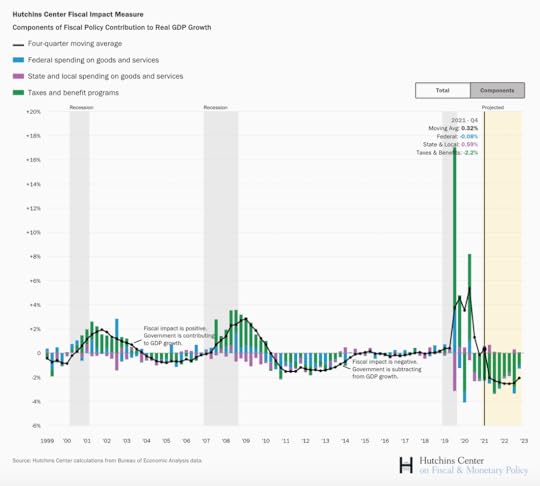

One of more striking set of data to appear of late are the quarterly numbers for fiscal impact produced by Brookings. For all the talk of Biden stimulus, the fiscal impulse went into negative territory in Q2 2021. Even on a four-quarter moving average basis it is now on the border of negative territory.

Source: Brookings

For more on the impact of Biden’s fiscal policy and the Rescue Plan in particular, check out this excellent piece by the EPI.

Though I would take issue with the language Weber uses to characterize the team transitory position – “houses on fire” etc – no one would deny that there are political risks involved in the current price surge. The Biden team clearly think it is important to be seen to be doing something about the price of petrol, meat etc.

But what purpose is served by labeling this as a policy of “price controls” and harking back to the 1940s?

On purely intellectual grounds a more wide-ranging debate is no doubt to be welcomed. But we are not in a debating club. This is the arena of high-stakes politics. What matters for the Biden administration are the midterms in 2022. Has anyone done any polling on how talk of “price controls” might play with important swing constituencies and media outlets that make a difference?

On drug prices, a large majority of Americans seem to favor robust drug price negotiations. But when the issue of price control is raised, at least one yougov poll (take it or leave it) shows little enthusiasm (and yes I am aware of the website this is published on).

Happy to be corrected on this, but perhaps an activist, tough government negotiator is more attractive than the bureaucratic visions summoned up by talk of “price control”. Certainly, the experience of 1940s control cast a long shadow over American public debate of the issue of price controls for decades to come.

Which brings us finally to the uses of history.

***

Some folks in the progressive camp are clearly convinced that taking inspiration from history, not just from the general aura of the New Deal, or from specific policies, but even from policies, like peacetime price controls, that were debated in 1946 but not implemented, is intellectually productive and politically helpful. I’ve been a skeptic on this “blast from the past”-strategy since the Green New Deal came on the scene. I find it hard to see how progressive politics benefits from this kind of historicism. As far as the Green New Deal is concerned I have come around. I’ve ended up embracing its grand vision of our historic predicament, whilst continuing to worry about strong analogies being drawn between the mid-century moment and our current situation. On those grounds I find Weber’s effort to segue from 1946 to 2022 unpersuasive.

Obviously, I share her interest in history and I share the enthusiasm for the writings of mid-century macroeconomists like Keynes, Kalecki, Lerner et al. But I am deeply skeptical when it comes to teleporting structural analyses and particular policy lessons from the mid 20th century into the present. And we should particularly guard against the kind of nostalgia that is evoked by the evocation of “If only, …..”.

In another domain of history and policy one might refer to this as the “Lost Victories” syndrome.

Precisely because the dynamic of modern history is so dramatic and so violent, because the pace at which complexity increases is so staggering, because the kaleidoscope of power and political economy shifts so radically, I don’t think that history’s role should be to invite us to refight past battles.