Adam Tooze's Blog, page 31

October 12, 2021

Chartbook #45: Of Scarface & the Nobel – The Double Life of Mariel

The award of the Nobel Prize for Economics to Berkeley’s David Card is important because of the recognition it extends to an economist who has consistently worked on urgent questions of labour economics. Together with the late Alan B. Krueger and the two other winners, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens, Card pioneered the methodology of natural experiments for the precise identification of causality.

The logic of natural experiments is janus-faced. It involves using happenstance and surprise to identify the degree to which broader, “general” laws, actually operate.

Commonly “natural” experiments arise from the arbitrary regulations of administrative systems. For instance, to test whether schooling impacts wages – an issue of huge general import – you exploit the fact that the birth dates on which kids are enrolled in school create arbitrary distinctions in terms of “school age”, whilst the date at which they may leave school, is simply set by their birth date. As a result, some high-school drop outs receive more education than others and that turns out to matter for their later earning potential. They are not a very large group in the workforce, but their particular characteristics allow identification of what we think is a general effect.

It is not just the unintended consequences of administrative regulations that can be exploited. Historical events, determined by a huge and complex web of politics and history, documented through complex mechanisms of power and knowledge, also generate shocks that may be described as “natural experiments”. The Mariel boatlift is a case in point.

On April 20 1980 Fidel Castro announced that Cubans who wished to leave to the United States were free to do so. The only stipulation was that they must depart through the port of Mariel. By 31 October 125,000 people had left for Miami. In May 1980 alone, over 86,000 arrived in the US.

It was chaotic. The migrants came in small groups – 1700 boats were used altogether. In Miami the authorities were overwhelmed. Meanwhile, the refugees struggled to find places for themselves in a city, which at the time was shrouded in a discourse of crisis.

Rumors that the boatlift included thousands of inmates of Cuban prisons and mental hospitals caused a widespread “moral panic”. At least a thousand were incarcerated and shipped back by the US authorities. Contemporary news accounts reported that some 20,000 gay and queer people had fled persecution in Cuba.

Decades later the New York Times quoted a former D.E.A. agent who described the migrants as “street urchins with bad intent … Within two weeks of getting here, some of them were working for dopers, bringing in loads and doing rip-offs.”” Old stereotypes die hard.

On May 17 a three-day riot erupted in several black neighborhoods in Miami. There were plenty of local grievances that served as an explanation, but an official report tied the unrest to the competitive pressure of the Cuban refugees.

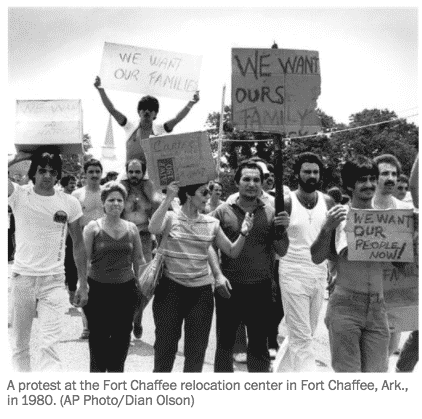

After shuffling through improvised accommodation in and around Miami, tens of thousands of refugees were shipped off to a variety of federal military facilities. By May 1980, 20,000 of the Mariel refugees found themselves concentrated at Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, triggering a second phase of the crisis.

In Arkansas the arrivals were fiercely resisted by locals and their governor, a young Bill Clinton. The ensuing riot is vividly described by the Washington Post:

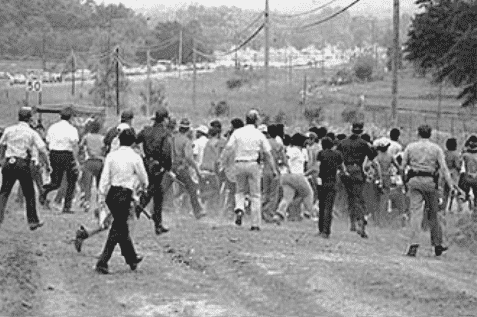

“The scene would later remind one witness of the Vietnam War. “Plumes of smoke billowed high into the illuminated night sky from barracks that had been set afire”. Flames still flickered from a charred guardhouse. Whoops and fierce cries of defiance echoed across the camp. Shotgun-toting civilians in pickup trucks loomed a mile or so beyond the gate. The mood was tense and chaotic. But this wasn’t Vietnam — or Iraq in the wake of an Islamic State attack. This was Fort Chaffee, a military installation in Arkansas, on June 1, 1980, when refugees from Fidel Castro’s Cuba rioted. The refugees had been sent there at the behest of President Jimmy Carter over the vociferous objections of an Arkansas governor with quite a political future: Bill Clinton. “The White House message seemed to be: ‘Don’t complain, just handle the mess we gave you,’” former Arkansas first lady — and possible future president — Hillary Clinton wrote in her memoir “Living History.” “Bill had done just that, but there was a big political price to pay for supporting his President.”””

The option preferred by the Clintons was to screen the Cubans on an aircraft carrier and to deport the unwanted back to the US base of Guantanamo. In Arkansas, Clinton warned Carter, he was struggling to prevent “a bloodbath that would make the Little Rock Central High crisis look like a Sunday afternoon picnic.” Clinton feared that he did not have the police resources necessary to prevent murderous clashes between protesting Cubans and heavily armed Arkansas locals (visible on the road in the background of this image).

According to Clinton “There had been a run on handguns and rifles in every gun store within fifty miles of Chaffee.”

Not surprisingly, many of the Cuban arrivals preferred to take their chances living rough on the streets of Miami. As innovative work by the Michigan PhD Alexander Stephens shows, they were subject to a regime of intensive police surveillance and documentation.

In the end, approximately half the Mariel arrivals managed to establish themselves permanently in the city.

Mariel entered urban legend by way of Scarface (1983), Brian de Palma and Al Pacino’s ultra-bloody portrayal of the Miami drug wars. The film’s opening sequence is set in a recreation of “Freedom Town”, an improvised tent city settlement put up under a Miami highway overpass, which erupted in riots in the fall of 1980.

The Miami Tourist Board was so sensitive about the reputational damage from the refugee crisis that Scarface had to be filmed largely in LA.

After an initial wave of sympathy, the attitude towards the Marielitos amongst Miami’s resident Cuban population rapidly soured. Some in the established Cuban population in Miami took to referring to them disdainfully as “Castro’s animals”. Statistical data confirms that they were younger and far less educated than the typical Cuban resident of Miami.

Source: Card 1990.

Driven by the moral panics surrounding the boatlift, the administrative machinery in Miami ground on. 125,000 came in the boatlift. As work by Alexander Stephens shows, in the final round up of Marielitos over the winter of 1980-1981 in the Miami area, 150 homeless people were stripped of their immigration parole. Intensive policing of this population documented a few hundred cases of unusual violence or dysfunction, and documented them so thoroughly that even 35 years later they are ready for the New York Times to regurgitate as emblems of the “Marelito crisis”.

The occasion was the normalization of relations with Cuba under President Obama. As the New York Times hastened to remind its readers, this reopened the Mariel question. Hundreds of the Mariel arrivals who had since fallen foul of the law face deportation back to Cuba. With the help of retired ex-cops in Miami, intrepid Times reporters traced down one paroled murderer to Illinois. Since the man in question refused to respond to their enquiries, the last word on this “bad hombre” (sic), was left to the detective, a Mr. Diaz: “He was vicious,” he said. “He was bad news. They should ship him back.”

As Stephens points out in this sharp piece, January 2017 was a good moment to revive 1980s visions of American carnage.

*********

How then do we get from Mariel as a violent emblem of America’s toxic relations with Cuba and the Caribbean, to the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel – aka the “Nobel” prize in economics?

What lured David Card onto this fraught terrain, what makes the Mariel boatlift irresistible, is a question of methodology, precisely the question highlighted by the 2021 Nobel awards.

Economists don’t like complex entangled histories. They don’t like them because they make it hard to cleanly identify causation.

Judging the impact of the large migrant flows from Mexico to the US is complex because the migrants themselves are heavily influenced by news about the labour market situation in the US. Migrants will not go to places where the labour market is so slack that their arrival would tend to depress wages severely and leave them unemployed. So, empirical tests will struggle to find large impacts of migration on unemployment and wages. But that does not mean that all else being equal the migration → wage effect is not real. It may simply be obscured by the fact that there is another causal loop running at the same time from wages and unemployment to migration flows.

One can cut through this complexity if one can find a moment – a natural experiment – in which those feedback loops are not operating.

Natural experiments are paradoxical – or perhaps dialectical. They are moments when out of complex and entangled social reality, events or interactions emerge that seem truly exogenous and random and thus allow the clear identification of what is cause and what is effect. Thesis-antithesis.

In the hands of Card, the Mariel boatlift became such a moment. The Miami labour market had been absorbing migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean for years. But, Castro’s decision in the spring of 1980 to release the flow of refugees to the United States was unrelated to the state of the Miami labour market.

It was a “natural” experiment, courtesy of the Cold War.

The inflow of migrants from Cuba and Haiti raised Miami’s workforce by 45,000 workers or 7 percent in a matter of months. Such an increase in the supply of labour ought – according to the precepts of neoclassical economic theory – to have shifted the price at which the labour market cleared in a downward direction. More workers → lower wages. And this effect ought to have been particularly pronounced at the bottom end of the labour market.

What David Card’s famous, 1990 paper on the Mariel shock in Miami demonstrated, was that this had not happened.

The average wages of workers in Miami were stable in the early 1980s, despite a national trend in the downward direction. This was true for white and black workers. The same was true for non-Cuban Hispanics who did relatively well in Miami compared to other cities.

The story for Cuban workers was more complicated. Their unemployment rate surged and their wages fell, as standard theory would predict. But the question is why? One can only speak of a displacement or competition effect if wages for Cubans already in the Miami labour market were forced down as a result of the Mariel arrivals. But what Card found was that the reduction in the average wage of Cuban workers was fully consistent with the lower skill level of the Mariel arrivals. As the Mariel arrivals joined the labour force, the average Cuban wage in Miami went down because the skill level of the new entrants was lower, not because they were exercising competitive pressure.

As Card pointed out, no natural experiment is ever actually isolated. One of the reasons that the Mariel boatlift population could be absorbed was that other migration to Miami slowed. All in all, Miami’s population in 1985 was where demographers had expected it to be in 1979, before the Mariel shock. There was no net deviation from trend.

Furthermore, as a city that had long grown through hispanic immigration, Miami had employers who were primed to employ Spanish-speaking migrant labour and were happy to take on the Mariel workers too.

*******

Qualifications aside, Card’s conclusions were remarkable. They go against the mainstream consensus not just with regard to recent migration, but of historical experience as well. In the first wave of globalization in the nineteenth century, we have robust evidence for distributional impacts on both ends of the flow.

But since the 1990s, Card’s research has spawned investigations in many other locations. This tends to confirm the view that migration on the scale we witness today in advanced economies has relatively slight impact on wages, unemployment and inequality. In the UK for instance, the large scale migration of the early 2000s is thought to have depressed wages for low-skilled service sector workers by 1 percent over a decade.

This finding, however, sits extremely uneasily with conventional economic understanding and with politics that favors immigration restriction, whether that be in the US, in Europe or elsewhere.

One economist who has been consistently concerned with the Mariel experience and is skeptical of the conclusions that Card draws, is George Borjas, who teaches at Harvard’s Kennedy school. In 2015 Borjas attracted considerable attention when in a paper published by the NBER he claimed to have overturned Card’s influential results.

Borjas set out to revise Card’s conclusion by tightening the focus on those groups that were most vulnerable to substitution – those with less than high school education. For that group Borjas claimed to have found a substantial negative effect associated with the Mariel shock. Wages for male, non-hispanic men of prime working age, plunged in 1980.

The result was a controversy that attracted attention across the entire world of wonkery. There were pieces in the Economist, reports in the WSJ and mentions on the FT’s blog, Alphaville. For the Trump administration, Stephen Miller seized on Borjas’s work. In Congressional hearings Geoff Sessions cited his results. .

But what are the data that these arguments rest on? Like the police records that scale from 125,000 migrants to a few hundred maladjusted individuals and violent criminals, it turns out that the battle over the laws of economics rests on a similar jeux d’échelles – a game of scaling.

The work of Card and Borjas is used to make general pronouncements about immigration policy, affecting tens of millions of people. But what is the empirical basis their rival results rests on?

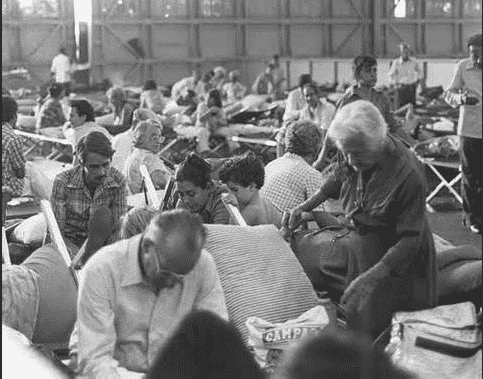

Forensic work by Michael Clemens traces the econometric assessment of the Mariel refugee movement back to their database in labour market surveys conducted in Miami in the 1970s and 1980s. In particular, the argument revolves around the returns for Miami from the March Supplement to the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, or CPS. Within those statistical compilations, the original finding by Card was based on returns taken from a population of c. 1200 of whom 185 were low-skilled workers with high school education or less. One might imagine that it was the people depicted in this image:

The Borjas’s result hailed by the Trump administration was derived by looking more precisely not just at those with less than high school education, but those who were male, non-Hispanic and of prime age only.

As Borjas shows this more carefully selected group saw a sharp decline in wages. But what Clemens detective work reveals is that the total number of respondents who fit Borjas’s more restrictive definition is 17. So, claims about America’s immigration policy involving tens of millions of people, depend on the answers given to a survey in Miami in 1980 by 17 non-Hispanic men of prime age with less than high school education.

Card’s group of 185 was not large. But Borjas’s restrictive definition excludes 91 percent of them.

Who were the 17 non-Hispanic poorly educated men on whom the argument rests? In the survey they remain name and voiceless. But, as Clemens shows, one thing about them is clear: they were overwhelmingly black.

In 1980 as a result of political protests about bias, the Census Bureau expanded its coverage to include a larger representation of low-skill black male workers. Not only were black workers lower paid, but the survey did not distinguish between different types of black respondent. In Miami, the figures for the black workforce in the early 1980s included an influx of exceptionally low-skilled and poorly paid Haitian refugees.

As Clemens shows, this double shift in the share of the black population in the sample and the composition of the black population to include Haitians, systematically skews Borjas’s sample of wages for low-skilled non-Hispanic workers precisely at the moment of the Mariel arrivals. To neutralize that effect, one might be tempted to to focus the analysis only on white low-skilled workers. But at that point the limitations of the survey intrude again. The number of white, male, prime age workers with less than high school education interviewed by the Census Bureau in Miami in 1980 was four. The wages of that plucky squad follow no very strong trend.

********

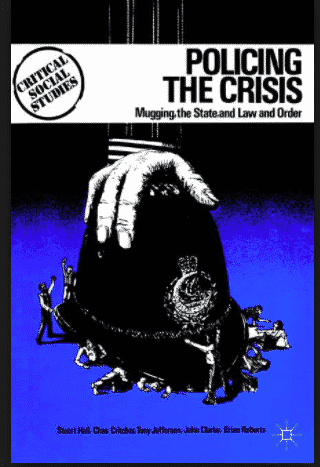

Mariel is thus constructed by two jeux d’échelles. On the one hand we have the mechanisms and procedures of discipline, control and surveillance applied to the individual refugees, which identified individuals and assembled them into social categories and made them disposable in a scandalized tabloid discourse of moral panic. The Birmingham School classic Policing the Crisis (1978) comes to mind.

At one and the same time the Mariel of the economists is constructed around labour force data and economic theories that are designed to enable statistical logic to be brought to bear. But due to the fixation on the identification of causation they require Mariel to be torn out of its context and figured as a “natural experiment” a truly “exogenous event”. Furthermore, when examined in detail the identification of the effects that economists are fixated on, requires a treatment of data that turns out to be the statistical equivalent of anecdotage. It involves the calculation of confidence intervals for a handful of respondents.

On the one flank widely circulating rhetorics of criminality and social control are generated out of an apparatus of individualized surveillance and control – the NYT reporters tracking down the paroled Marielito murderer laying low decades later in Illinois. On the other hand we have an apparatus of social scientific expertise notionally committed to making real a vision of statistical aggregation, generative of generalizable knowledge, that in fact comes to rely on family-sized samples of individuals.

But another common feature of both forms of power/knowledge, however, is that they leave systematic traces. As the work of Stephens and Clemens so forcefully demonstrates, we can open the black box for historical reconstruction and critique. We can demonstrate, once again, the power of second- and third-order observation.

October 10, 2021

Chartbook #44: The Cross of Gold – populism, democratic iterations and the politics of money

“Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

The address that Nebraska’s William Jennings Bryan delivered at 2 pm on July 9 1896 at the Chicago Convention of the Democratic Party – the “Cross of Gold” speech – is a stunning piece of oratory on the theme of the gold standard and the peril that this rigid monetary system poses to society.

The incident is familiar to anyone with a background in American history. But when I first encountered it, as a European, I was staggered. It struck me as a truly remarkable example of democratic politics engaging with the question of money. It is more than 120 years old, but everyone concerned with monetary politics today should read Bryan’s speech. The full text is here.

Bryan’s oration culminates in these glorious paragraphs:

“If the gold standard is the standard of civilization, why, my friends, should we not have it? So if they come to meet us on that, we can present the history of our nation. More than that, we can tell them this, that they will search the pages of history in vain to find a single instance in which the common people of any land ever declared themselves in favor of a gold standard. They can find where the holders of fixed investments have.

Mr. Carlisle said in 1878 that this was a struggle between the idle holders of idle capital and the struggling masses who produce the wealth and pay the taxes of the country; and my friends, it is simply a question that we shall decide upon which side shall the Democratic Party fight. Upon the side of the idle holders of idle capital, or upon the side of the struggling masses?

…

“There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, that their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous their prosperity will find its way up and through every class that rests upon it.

You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard. I tell you that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.

….

It is the issue of 1776 over again. Our ancestors, when but 3 million, had the courage to declare their political independence of every other nation upon earth. Shall we, their descendants, when we have grown to 70 million, declare that we are less independent than our forefathers?

….

If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we shall fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

*********

Bryan and the populist struggle with the gold standard seem particularly topical because we are, at this moment, debating the economics and politics of inflation and monetary policy. If Modern Monetary Theory insists that monetary sovereignty is there for the taking, in America, that is a claim with a deep history. Not that Bryan was an advocate of modern monetary policy, but he refused to subordinate America’s currency choices to the blackmail of monied interests.

Then there is the meta question. Set against the backdrop of recent history the fact that we are debating monetary policy at all can seem shocking. In the era of the 1980s and 1990s, insulating monetary policy from democracy was a key priority. The point, Rudiger Dornbusch, the influential MIT macroeconomist, liked to insist, was to put an end to “democratic money”.

But for money to be unpolitical, is not the natural order of things. It is the effect of a particular politics, a metapolitics of depoliticization. As Stefan Eich shows us in his forthcoming book, the Currency of Politics, the argument over the politics of money goes back to the ancients. The question should not be – “political money, or not?”. “Democratic money, or not?” The question should be – What kind of politics of money? What kind of democratic money?

The William Jennings Bryan moment rose to the top of stack for my stack in recent weeks, because I am teaching a grad class about the tense relationship between capitalism and democracy in the US and Europe. Our first session was on 1896, William Jennings Bryan and the Cross of Gold Speech. The readings for the session were as follows:

Bryan’s speech, which you can read here.Rockoff, Hugh. “The” Wizard of Oz” as a monetary allegory.” Journal of Political Economy 98.4 (1990): 739-760.Excerpt from Bensel, Richard Franklin. Passion and Preferences: William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Democratic Convention. Cambridge University Press, 2008.Bryan, William Jennings. “Has the Election Settled the Money Question?.” The North American Review 163.481 (1896): 703-710.Sanders, Elizabeth. “Farmers and the State in the Progressive Era.” The Progressive Era in the USA: 1890–1921. Routledge, 2017. 41-63.Sanders, Elizabeth. “In Praise of Populism.” Cornell International Affairs Review (2009): 11.Abbott, Philip. “Bryan, Bryan, Bryan, Bryan”: Democratic Theory, Populism, and Philip Roth’s “American Trilogy.” Canadian Review of American Studies 37.3 (2007): 431-452.Jäger, Anton, and Noam Maggor. “Phenomenal WorldOctober 1st, 2020 A Popular History of the Fed.”I will tinker with this reading list on future iterations. There is a piece by Milton Friedman, I wished I had included. But this reading list clicked.

To be clear, this is not an American history course. The course is intended for a cosmopolitan mix of students with varied backgrounds interested in the broad theme of capitalism and democracy. The aim of the game is to highlight a series of general issues circling around the politicization of money, how popular mobilization affects the development of economic policy institutions and ways in which politics continuously reactualizes the populist moment.

The majority of the students are not historians, so rather than issues in the American historiography – Who were the populists? Were they racist and exclusionary etc? – what I want to encourage is engagement with the complex entanglement of historicity as such. What I have in mind is Faulkner’s great line that, “the past is never dead. It is not even past”.

The readings are chosen for their content, of course. But I also encourage reading them as historiography and as historical sources, as signifying something about the moment they came out of. That is obvious with regard to the Bryan texts. But it is true also of a blogpost from 2020. This history IS not even past.

******

The starting point for the silver agitation was the agonizing deflation that squeezed down on the North Atlantic economy in the late 19th century.

Source: Rockoff (1990)

Wholesale farm prices crashed in the 1870s, then bounced, then crashed, then bounced again and then in the early 1890s fell to their lowest ebb. In 1896, at the moment that Bryan gave his speech, wholesale farm prices were 56 percent below their 1869 level.

The period 1893-1896 saw the US economy wracked by crisis. Unemployment rocketed into the teens and the survival of the US on the gold standard was in doubt.

Source: Political cartoon from Judge magazine, Oct. 5, 1895. Digitized by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The ultimate reasons for this deflation are complex and disputed. What the populists challenged was the decision to end the monetary chaos of the civil war era in the 1860s by returning to gold, a move completed in 1879. Specifically, what they contested was the Coinage Act of 1873 that ended the right to have silver minted into coin. As Rockoff remarks: “Between 1869 and 1879 the stock of money grew at about 2.6 percent per year and real output at about 5.0 percent per year, so the deflationary pressure from the lack of monetary growth is easy to understand.”

In any case, the point of this session was not so much to answer the question of what caused the late-19th-century deflation, as to show what folks made of it. What agitated the populists, was not only the fact that silver was downgraded relative to gold, but that deflation on this scale crushed debtors. Farm incomes shrank. Mortgages did not.

As Rockoff remarks: “Although the percentage of farmland that was mortgaged was low for the nation as a whole, western farmers … were heavily mortgaged. Kansas had one of the heaviest levels of indebtedness, with 60 percent of taxed acres under mortgage.”

The promise of the free silver movement was that by breaking the link to gold and enabling the minting of silver, an expansion in the money supply would raise prices and ease the pressure on debtors. In 19th-century language, inflation simply meant an expansion in the money supply.

Faced with the bitter hostility of the gold standard bloc, the free silver movement provoked intense controversy. At the Chicago Convention in 1896 there were scenes bordering on riot as advocates of the gold cause and silver took turns to demonstrate their enthusiasm. Richard Bensel in his remarkable microhistory brings the Convention to life in vivid detail. It is akin to an ethnology of late 19th-century American politics.

The Chicago Conference Hall, July 1896

Bryan’s speech sent the Convention into convulsions. So famous was the speech that in 1921, on the 25th anniversary, Bryan made a recording which you can hear on youtube.

As Bensel highlights there was nothing accidental about the sensation that Bryan generated. Bryan rehearsed his delivery. On the eve of his performance, he remarked to his wife and a companion: “So that you both may sleep well tonight, I am going to tell you something. I am the only man who can be nominated. I am what they call “the logic of the situation.””

Bryan’s confidence was rewarded. Whether he was “the logic of the situation” or not, he carried the day and was nominated for the Presidency.

A few months later he narrowly lost the election to McKinley. The gold standard remained safe and the populist cause suffered defeat.

Famously, the struggle was commemorated in the Wizard of Oz by Frank L. Baum. Rockoff provides a brilliant reading, of how Baum encoded the gold standard battle in his modern fairy tale.

Bryan’s defeat was a turning point in American political history, meaning that the 20th century opened under the sign of “control” rather than popular, democratic mobilization. Twenty years later the moment was commemorated by the anti-war poet Vachel Lindsey in a remarkable sentimental poem.

On Vachel Lindsey’s peculiar poetic and political persona see the Poetry Foundation.

***********

In the aftermath of defeat, Bryan was unbowed. In an essay he published in December 1896 he offered a remarkable diagnosis of the effects of his campaign, a paean to the democratic politics of money and to the importance of throwing open the agenda of economic policy.

“As a rule”, Bryan remarked, “the moneyed interests have looked after our financial policy, while the rest of the people have quarreled over the tariff. The Republican party met in convention last June and attempted to again give the tariff question pre-eminence, but when the Democratic, Populist, and Silver parties agreed in declaring for the free and unlimited coinage of gold and silver at the present legal ratio of 16 to 1, without wait ing for the aid or consent of any other nation, the Republicans found it impossible to confine discussion to the tariff issue. In fact, the silver question soon absorbed public attention to such an extent that it became practically the sole political topic considered throughout the country. People discussed the present legal status of the silver dollar, the various laws affecting silver, the amount of production, the cost of production, etc., etc. To the world at large this nation presented the interesting and inspiring sight of seventy millions of people thinking out their own salvation. Men who had never spoken in public before became public speakers; mothers, wives, and daughters debated the relative merits of the single and the double standards; business partnerships were dissolved on account of political differences ; bosom friends became estranged ; families were divided. In fact we witnessed such activity of mind and stirring of heart as this nation has not witnessed before for thirty years. Foreign newspapers daily reported the progress of the campaign and students of political economy came from Europe to obtain a closer view of the struggle. It is probable that the money question has been studied within the last four months by more people than ever before in all the history of the world simultaneously engaged in its consideration. And what was the result of that study ? Temporary defeat, but permanent gain for the cause of bimetallism.”

It was significant, Bryan remarked, that pro-silver sentiment was strongest where the question had been ventilated for some time, above all in the West and the South.

In the Eastern states, the heart of America’s business economy, debate of the money question had previously been silenced.

“In those States both parties were against free coinage; nearly all the leading news papers were against it; the banking interests were against it ; the corporations were against it; and it was also opposed by those influential members of society who live under the influence of the financial and corporate interests.”

The populist breakthrough at the 1896 convention overturned this repressive consensus. The Democratic Party in the East was reorganized and though the silver cause went down to defeat, it made great strides. And it was vital that this agitation should continue. Having defeated Bryan, the defenders of gold demanded unconditional acceptance of the status quo.

“They complain that agitation disturbs business, and they accuse the advocates of free coinage of stirring up discontent.”

But, Bryan retorted, “(those) who suffer because of the gold standard can hardly be expected to keep quiet and look pleasant while the injury continues. … They too want confidence restored, but it must be a confidence that their condition will be improved not that their lot will be made still harder. Agitation is the only means by which wrong can be redressed under our form of government. The man who denounces agitation simply opposes the discussion of a public question, and the man who attempts to put a stop to the discussion of a public question confesses his hostility to our form of government. In a nation where the people govern, they must be free to consider any subject which concerns their welfare.”

The money question, Bryan insisted,

“transcends in importance any other economic question which can occupy the attention of the American people. When we determine the kind and quantity of money we determine the level of prices, and the level of prices concerns every family in the land.”

Much less well known that the “cross of gold” speech, Bryan’s retrospect on the campaign stands as a powerful justification for a democratic politics of money. It was eloquent and compelling and it forces the question. What was the meaning of populism’s defeat? What consequences did that defeat have at the time?

*******

These are questions of interpretation that are irreducibly political. They echo down to the present.

Populism was defeated in 1896, America remained on the gold standard, but the early 20th century is widely seen as having been a period of reform. It was the era of Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. It set the stage for the New Deal. To what political force can those changes be attributed?

One political line characterizes the era as one of progressive triumph. Progressives were middle class reformers dedicated to forestalling the agrarian and grassroots mobilization of populism by means of technocratic reform.

Another current that came to the fore in the aftermath of 1896 was what has been termed “corporate liberalism”. On this view, the force that stood behind the modernization of government was the increasingly consolidated power of American capitalism, expressed in the merger wave.

Both progressive and corporate liberal readings of this historical moment minimize the role of populism and specifically the agrarian interests that it represented. But the populists have their defenders too. The most compelling counter-interpretation is offered by Elizabeth Sanders.

For Sanders the remarkable range of statist measures enacted between 1910 and 1916, often associated with the “New Freedom” agenda, crafted for Woodrow Wilson by Louis Brandeis, was, in fact, in large part the work of Congressional populists. Bryan himself served in Wilson’s administration as Secretary of State, pursuing an agenda of international conciliation in a vain effort to prevent the outbreak of World War I. At home, Wilson’s progressive agenda was in large part the fruit of the agrarian mobilization.

As Sanders lucidly argues, it would be simplistic to imagine that the progressive, the corporate liberal or the populist agenda would simply be carried into government policy. We need to consider a three-way configuration of forces including extra parliamentary pressure, Congressional action and the structures of government themselves.

As has recently been argued by Stefan Link and Naom Maggor, the United States of the late 19th century was a developing nation. The agrarian mobilization of the 1890s cast a long shadow.

The Fed in particular was a product of this balance of forces. The Wall Street lobby had its say, as did progressive technocratic ideas. But the Fed that emerged in 1913, as a public body with a governing board located in Washington DC rather than Wall Street, was viewed with deep suspicion by the financial lobby and denounced as product of meddling populist impulses.

***********

If there is one piece I would swap into the reading list for the session, it is the appreciation of populist monetary economics by Milton Friedman from 1990. Friedman is well known as an exponent of the quantity theory of money. The godfather of the quantity theory in its modern form was Irving Fisher (1867-1947), who began his career at the time of the populist mobilization. Fisher sympathized with the critics of the gold standard. Clearly, adherence to gold did not produce a stable value of money. Instead, money’s value rose inexorably against goods, as prices fell. Tying the value of money to silver as well as gold was a bit like trying to achieve stability by tying too drunks together. Rather than gold or a bimetallic silver-gold standard, Fisher argued for a stabilized “compensated dollar”. With hindsight, however, both Fisher and Friedman were willing to conceded that the populists had a point. The urgent need was for a monetary expansion by whatever means. If the world economy had not been boosted by a rash of gold discoveries in the 1890s, the technological innovations of the period, might well have led even deeper into depression and crisis.

*******

The embrace of populist economics in the course of the later 20th century, is indicative of a broader reevaluation, which in the hands of Elizabeth Sanders amongst others has a political edge. As Sanders remarked in 2009:

“Newspaper and Television commentaries in the United States and Europe abound with references to “outbursts of populism” in United States as a stereotypically American response to economic crisis. Their story lines trivialize historic Populism in the U.S., both its substance and its contribution to financial regulation.” In the wake of 2008 she hoped, against hope, that a reforming Democratic administration might side with the pitchforks against the entrenched interests of finance and push for truly radical reform.

Dodd-Frank was a bitter disappointment. But one can learn from the populists also in defeat. As Bryan remarked about 1896, campaigns to politicize and democratize money cannot be judged only by whether they come first at the polls. They are, as Seyla Benhabib might say, democratic iterations. Part of an ongoing struggle and deliberation that draws recursively on its own history and precedents. If the crisis of 2008 did one thing, it ended the illusion that money could be unpolitical. In the years since, central banking choices have been debated and open to public scrutiny. The level of popular engagement is nowhere near that described, perhaps wishfully by Bryan in 1896. But it is nonetheless novel. And, as the blog post by Jäger and Maggor attests, that process, again and again, recurs to the populist moment.

As Jäger and Maggor remark: “the Populist story gives historical heft to some recently floated reform schemes. Central bank planning might already be here and simply be awaiting democratization, but it is hardly unprecedented. Rather than a historical departure, the democratic empowerment of central banks could fulfill deep-seated democratic aspirations, articulated by farmers, workers, and craftsmen in the turmoil of the first Gilded Age.”

October 8, 2021

Chartbook #43: An IMF-Crisis Made in America

Will the Managing Director of the IMF survive the day?

This is not the normal question with which to begin the “fall meetings” of the Bretton Woods Institutions – IMF and World Bank. The annual meetings are the big global jamboree for policy wonks and policy-makers. Since 2009 they have come to be tied to meetings of the G20. Unlike the UN General Assembly, in which every country has one vote, or the Security Council, which reflects the global power structure at the end of World War II, the IMF/World Bank/G20 meetings are the world assembled according to the balance of economic power.

This is how that weighting looks right now.

Source: General Theorist

This year, the world economic powers have to start their deliberations by deciding whether Kristalina Georgieva, formerly the #2 at the World Bank and now the #1 at the IMF can stay in her post. And if not, what implications that has for the position of David Malpass at the World Bank.

The scandal, if that is the right name for what is happening, involves a report commissioned by the current leadership of the World Bank into activities involving the compilation of the World Bank’s Doing Business index in 2017.

The Doing Business Index was the most widely watched ranking issued by the World Bank. This may seem surprising, but as Dan Drezner explains in this smart column a wide range of political science research shows that governments actually care about these rankings.

It should also be said, however, that in the bestiary of economic numbers the World Bank’s Doing Business index was one of the most synthetic. All economic numbers are cocktails of concepts, institutional definitions, politics and quantifying enumeration. But the Doing Business index is a truly synthetic score – like a college ranking or a quarterback rating. The idea in this case was to measure how easy it is to invest or start a business.

The ranking seeks to summarize the fact that “an entrepreneur in a low-income economy typically spends around 50 percent of the country’s per-capita income to launch a company, compared with just 4.2 percent for an entrepreneur in a high income economy. It takes nearly six times as long on average to start a business in the economies ranked in the bottom 50 as in the top 20.”

Such differences are no doubt real. The question is how to measure them and to reduce them to a single index. In the eyes of its many critics, what the World Bank numbers actually amounted to was something more like a beauty contest, with countries judged on the degree to which they conformed to a script of Washington consensus-approved “reforms”, as judged by a handpicked group of local experts and by the World Bank analysts who “owned” the index. Tellingly, it took concerted pressure from the Obama administration, itself under pressure from US Labour Unions, to have an index component removed that rewarded countries for loosening protective labour legislation.

The numbers were, in short, Washington consensus orthodoxy, recast in statistical form. Simeon Djankov, the World Bank economist who presided over the index – rather high-handedly if one believes the reports – was a Bulgarian veteran of the transition debates of the 1990s. As Djankov has explained, the index was designed to reflect ideas about the role of institutions in promoting economic growth put forward by so-called “transitologists” and the campaigning neoliberalism of the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto. In particular, Djankov collaborated with Andrei Shleifer, one of the most controversial of the carpetbagging economists of the 1990s.

Independently of the scandal now engulfing it, an expert panel had subjected the index to withering criticism.

But, if the statistics were murky, so too were the politics that have triggered today’s scandal.

The critical investigation into the goings-on in 2017 was launched in 2020-2021, as a retrospective exercise. The current leadership of the World Bank was put in place by Donald Trump in 2019. The report concentrates on the activities of Georgieva, now at the IMF, under the World Bank Presidency of Jim Kim, nominated by Obama in March 2012.

The allegation is that in 2017 Kim and Georgieva exercised undue pressure on World Bank staff to produce a more favorable result for China in the influential annual ranking exercise.

The investigative report produced by the influential law firm WilmerHale on the basis of extensive interviews with World Bank staff, paints a vivid picture, of feverish bureaucratic politicking.

78 Was the ranking of China in the World Bank’s Doing Business index in 2017. In the summer of 2017 it became clear that China would rank lower in the next issue of the report, due for publication in October. This was not because China was backsliding but because others had upped their “reform” efforts. Existing procedures suggested that China would drop to rank 85. The WilmerHale report paints a vivid picture of the frantic effort to redress that result. It culminates over the weekend of 28-29 October with Georgieva meeting a “Doing Business manager” in the driveway of their home, to personally collect a copy of the final report, which safely restored China to 78th place in the global rankings.

The report is masterfully put together, both damning and yet careful in avoiding direct allegations of impropriety. The picture painted is somewhere between All the President’s Men and In the Thick of It.

Georgieva denies any wrong-doing. Senior members of the World Bank staff who were directly involved in compiling the index, exonerate Georgieva and insist that the WilmerHale report is slanted and took their testimony out of context.

In any case, the damage is done. The US Congress is in uproar. Georgieva’s alleged favoritism towards China will be red meat for the likes of Ted Cruz. As Ed Luce has argued, if she stays on, with her legitimacy weakened, the IMF is much enfeebled.

If, on the other hand, Georgieva is forced to resign, it would be a shock to the European countries that nominated her, as well as the many other countries in the developing world that have backed her as Managing Director and strongly approve of the direction she is taking the IMF in.

During her tenure so far, Georgieva, has been vocal in demanding a more proactive role for the Fund in addressing humanitarian crises and the climate emergency.

This Lunch with the FT profile by Brendan Greeley is intriguing.

”Kristalina Georgieva starts to sing, in Bulgarian, right there at the table — quietly, but firmly, the way you might sing to a child on absolutely her last lullaby of the evening. It is a song she wrote as a teenager in the late 1960s, in her grandparents’ village in the mountains in communist-era Bulgaria, when she ran out of shelves in the local library and started reading philosophy. She finishes a couplet, then translates.

But what is the value of Kant and Spinoza

If somebody else writes predictions for me?“

Ousting Gergieva, would be more than merely a personnel decision. It would be hard not to see it as a victory for the conservative wing of international finance.

*******

This crisis, spun out of allegations about events in 2017, has a strange timewarp quality about it.

It revolves, inevitably, around the rise of China, its influence at international organizations and differences between Americans and Europeans. It feels very 2020/2021. But what is actually at stake, is the degree to which China in 2017 was conforming to the World Bank’s standards of reform and market openness. The allegation is that Kim and Georgieva intervened because they feared that Beijing would be upset by a low score.

It is as if the old narrative of Chinese convergence (on standards set by the Washington consensus), has crashed into the new narrative of great power competition between China and the US. Either way, China cannot win. Or rather, either way, one or other group of Americans are angry.

So, the end of the Cold War and the rise of China are in the background here, but, the crucial point to insist upon, is that this is a crisis made in America.

The incident in 2017 and its subsequent investigation reflect the turmoil of the transition from the Obama to the Trump and the Biden Presidencies. The latest report was triggered in Washington DC, by office politics within the World Bank and IMF headquarters. The investigative reports were unleashed on the world by David Malpass, a notorious enemy of China’s rise, appointed to the World Bank Presidency by Trump. The Biden Presidency will have a key role in deciding the outcome. A critical factor in their decision-making will be the attitude of the US Congress.

******

American power is as visible in the silences in proceedings, as it is in the public criticism and denunciation. The report by WilmerHale frames its graphic account of the making of the index in September and October 2017 against a dramatic backdrop.

Kim and Georgieva were struggling to hold China on side because they feared that “one key stakeholder would meaningfully reduce its commitment to the institution”, as WilmerHale puts it. Georgieva told investigators that she feared that nothing less than the survival of multilateralism was at stake.

WilmerHale never tells us who the “key stakeholder” was that was causing such stress and making the World Bank’s situation so precarious. It was clearly not China. Beijing actively backed a capital raise. It was, the United States under Donald Trump.

In other words the WilmerHale report alleging favoritism towards China simply omits the context which put the World Bank leadership under such pressure.

In 2017 Trump opened his broadside against global institutions, like UNESCO and the WTO. The World Bank was in the crosshairs because it lends on a large scale to middle-income countries including China. Kim and Georgieva were not just trying to placate Beijing. They had to deal with the White House too. And whereas their concerns for China’s ranking were a matter for technical discussions behind closed doors, their efforts to ingratiate the World Bank with the Trump administration were embarrassingly public.

In the spring of 2017, the World Bank offered to put its infrastructure expertise at the disposal of the White House for its much ballyhooed infrastructure plan. Even more overtly it provided administrative support for Ivanka Trump’s pet project, a $200 million fund for women’s entrepreneurship with half the funding provided by the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

As the Financial Times remarked in May 2017:

“Mr Trump’s fondness for mixing public policy with personal considerations is not the least of his many flaws. But for the (World) bank, securing continuing funding from the US is not worth the blow to its credibility that such a quid pro quo would deliver. …. Mr Kim is in a difficult position. The World Bank does not normally have to deal with a White House that seems so indifferent to its continued existence. But risking the bank’s credibility by appearing to engage in personal favours for the US president is not the way to proceed.”

Not a word of any of this in the WilmerHale report. The report narrows to a police procedural what was, in fact, a geopolitical balancing act.

Nor should this be surprising. As Mark Copelovitch remarks, it is not as though politicking is not part of what the World Bank and the IMF do and that extends to the politics of statistics.

Also, maybe this is a "scandal." But anyone who tells you this sort of politics has not always been central feature of IMF policymaking – w/ some states exercising outsize influence & receiving preferential treatment – is trying to sell something.https://t.co/bM5Al3ahTQ

— Mark Copelovitch (@mcopelov) October 8, 2021

The tuning of the numbers may leave a bitter taste in the mouth, but there is no innocence in this business. Rather than denouncing their balancing act, it would be fairer to judge Kim and Georgieva by the outcome they achieved. For a fairly modest price, they held China onside and in the end persuaded the Trump administration to back a capital raise.

By 2018, it seemed perhaps as though Kim and Georgieva had navigated the rapids. They had, in Bruno Latour’s terms, withstood a trial of strength and when things hold together, “they start becoming true”.

But, the problem with the balancing act of modern global politics is that the trials of strength never ends. The forces at play are constantly shifting and so too is the narrative.

**********

The Doing Business index itself was a running sore. It was a rickety and unpredictable construction shot through with discretion and complex judgements.

In January 2018, shortly after the China incident, Nobel laureate Paul Romer resigned as chief economist of the World Bank, after calling into question the way in which Chile, under the social democratic government of Michelle Bachelet, had been repeatedly downgraded in the Doing Business rankings. He suspected foul play on the part of the staff involved with the index at the World Bank. At the time, none other than Georgieva took to the pages of the Wall Street Journal to defend the integrity of the index. And before resigning, Romer backed away from some of his criticisms.

At that point the front was still intact. But then, in January 2019, rather than hunkering down and outlasting the Trump presidency, Jim Kim resigned from the World Bank to join a private infrastructure firm. That enabled Trump to appoint David Malpass, one of the loudest critics of the Bank and its alleged pro-China bias, to the top job, leaving Georgieva in an uncomfortable position. When Christine Lagarde, then boss of the IMF, emerged as the replacement for Mario Draghi at the ECB, Georgieva jumped at the chance to succeed Lagarde at the IMF.

Malpass and Georgieva cooperated tolerably well in 2020, but the skeletons were in the closets and all it took was a whistle-blower at the World Bank to give Malpass his opportunity to settle some old scores. As one of the chief instigators of the Trump administration’s bullying of the World Bank in 2017 – the attack that had put Kim and Georgieva under such intense pressure – Malpass has now invited the world to see how the sausage was made.

*********

The operation has added piquancy because Malpass has his own problems with the index.

China isn’t the only major player. There are also the Gulf states to consider.

As Justin Sandefour of CGD makes clear in a powerful post. The WilmerHale report is remarkably taciturn when it comes to the spectacle of “Davos in the Desert” in 2019, the Saudi business summit hosted by MBS and attended by Jared Kushner, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and David Malpass of the World Bank.

As Sandefour sums it up:

“On the eve of the Riyadh event, the World Bank launched the 2020 Doing Business rankings, and declared with much fanfare that the top reformer in the world was none other than Saudi Arabia.

The only problem was that the data had been manipulated (again).

The WilmerHale report notes that the original calculation had Jordan coming out as the top reformer, but Simeon Djankov—the Doing Business founder who was also at the center of the China scandal—ordered the team to find a way to alter the data to knock Jordan out of the top place, and to add points to Saudi Arabia’s score. The method used to help Saudi Arabia inadvertently helped the UAE as well, but didn’t affect its overall ranking.”

The motive for this change, and even who ordered it, is contested among the individuals interviewed. But the WilmerHale report does note that “we identified no evidence suggesting that the Office of the President or any members of the Board were involved in the data changes affecting Saudi Arabia and UAE in the 2020 report.”

The Sandefour post is really excellent. Highly recommended.

Nor was Saudi Arabia the end of Malpass’s problems with the Doing Business index. As investigative reporting by Bloomberg has unearthed, after hailing Saudi Arabia as top reformer in 2019, in the summer of 2020 Malpass faced a set of data which showed China soaring up the league table from 31 to 25th place. Whatever may be said for the adjustments in 2017, they would seem to have been generally in the right direction!

Such a high ranking was clearly not to Malpass’s liking, and it would have sat even worse with his sponsors in the Trump administration. After discussing various technical changes that might have reduced China’s score, the decision was taken to announce that in light of “data irregularities” the publication of the entire report would be suspend.

An internal December 2020 Management Report to the World Bank confirmed not one but four instances of “data irregularities” that put in question the integrity of the entire system.

Source: World Bank

********

So, the world is confronted in October 2021 with a toxic hangover of the Washington consensus. A battle over a tendentious index that no longer exists, unleashed by a World Bank management team installed by Trump, at odds over China with their predecessors. Which begs a question, if this crisis is brewed in Washington, where does the Biden administration stand?

What about the US Treasury? Clearly it cannot act too publicly. Congress is a minefield. But why is Yellen not answering Georgieva’s calls? And why does the press know? Who is handling international affairs at Treasury?

When Georgevia arrived at the IMF, the number #2 was David Lipton, a heavy hitter appointed by Obama. Rather than allowing Lipton to finish out his term and drawing on his expertise, Georgieva pushed him out. Instead, she accepted the appointment by the Trump administration of a replacement for Lipton who has been politely described as inexperienced and under-qualified, and less politely as a “pot plant”.

Lipton’s ouster has been widely interpreted as a power move. It was widely regretted at the time.

On 2 February 2021 Lipton now as counsellor to Janet Yellen at the Treasury. Lipton’s precise role is somewhat ill-defined and significantly underreported, but it appears to involve handling relations with the G7 and the G20, the key stakeholders in the IMF and the World Bank. What he is reported as doing in September is attending meetings at which the Chinese authorities and American financiers discuss regulatory issues and Evergrande. What he is not reported as doing is running interference for the IMF.

Georgieva, one might conclude, does not have many friends in Washington.

It seems more than unlikely, however, that Lipton is part of any “coup” against the head of the IMF. Lipton, committed as he is to multilateral institutionalism, has better things to be doing that knifing Georgieva. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that anyone in the Biden administration welcomes the current mess. Not only is it embarrassing. But it exposes the vacuum where a concerted foreign economic policy on the part of the Biden administration ought to be. Admittedly, Janet Yellen has successfully cooperated with the Europeans on a global tax plan. But beyond that, the Biden administration is struggling to formulate a trade policy towards China that goes beyond platitudes. The Build Back Better World scheme announced at the G7 in Cornwall over the summer is, so far, an empty shell. Lipton is in the role that he is, because there is no Under Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs in place. The Yellen Treasury has a huge backlog of vacant positions to fill. Having failed to stop the Nord Stream in Germany, the Republican hawks are sanctioning the US Treasury instead.

America’s mess lands in the world’s lap. And above all in the lap of the Europeans. They still regard the IMF as their job. If Georgieva is to go, who is up next? In an alarming thread on twitter, “General Theorist” warns that the Europeans might go back to their shortlist of 2019 and might bump Jeroen Dijsselbloem into the job. That would likely betoken a return to conservative orthodoxy at the Fund.

At the very least Sandefur rightly argues, if Georgieva goes then Malpass should go too.

Make of it what you will, but I’ve just been informed that an event we were due to host at Columbia with France’s Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire on Friday October 15 has had to be canceled. He was expecting to be on his way back to Europe by then. Now Europe’s Finance Ministers have been called for an unscheduled meeting in Washington that day. In 2019 it was Bruno Le Maire who managed the shortlist of candidates to succeed Lagarde.

If you enjoyed this installment of Chartbook, why not considering subscribing.

The crisis at the IMF – the latest episode of Ones and Tooze is up!

Hi friends,

the latest episode of Ones and Tooze is up.

Cameron and I tackle the background to the scandal surrounding Kristalina Georgieva, MD at the IMF.

Its a story of economic statistics, skullduggery and geopolitics. How could we resist! And it could hardly be more timely. According to the FT, Friday is decision day.

If you haven’t tried the podcast yet, check it out.

You can get it from Apple here

And Spotify here

And lots of other links at our FP website.

If you’ve been following the Ones and Tooze show and enjoying it, please leave us a review. Every nice review helps!

And, for extra good karma, tweet out the show and tag @ApplePodcasts

We really want to get their attention!

If you are new to the newsletter, sign up here. Fee and free options available.

October 5, 2021

Chartbook #42 – The Great Inflation Debate

Whether we are living through the beginning of a new inflation is uncertain. What is clear is that we are living through a great inflation debate.

I cannot think of a period in recent memory, in which there was so little agreement on likely future trends.

The uncertainty causes real anxiety for policy-makers and the public. Does it amount to a crisis of the authority of economics?

“Nobody Really Knows How the Economy Works” ran the New York Times headline a few days ago. Might this be the opening for a new and better type of analysis? I would not presume to answer that question. But this is a moment to orientate ourselves. Once again, it is a moment for second-order observation, a moment to watch the inflation-watchers.

Why is this moment producing so much controversy and debate?

First there are the issues with the data themselves. When economic disruptions happen, they unleash adjustments that make the disruptions hard to measure. It is a bitter irony. Precisely when you need them the most, the data get difficult.

All the evidence both quantitative and qualitative suggests that the actual state of the economy right now is hard to read. The situation is illegible because different parts of the economy are moving at different speeds and in different directions.

Add to this the fact, that even before the COVID crisis hit, central bank economists were struggling to make sense of what was then a world of lowflation. That uncertainty has carried over to the post-COVID world. If economists struggled to explain low inflation, they now struggle to explain price increases.

There are some commentators, of course, who are only too ready to offer explanations and remedies. Price adjustments are political, inflation is a boogey man with which to scare conservative constituencies. In Europe, in particular, inflation-fear is about.

And politics comes in different flavors. Another, novel component of the current landscape are a brilliant group of neo-Keynesian economists, who have built good connections in think tanks and the media and are skillfully seizing this opportunity to prize open chinks in the armor plates of orthodoxy.

It adds up to a complicated scene. And Chartbook is here to help.

********

I love putting together this newsletter and I love the fact that it goes out free to many readers. If you are enjoying the read and can afford to support the project, please consider signing up for one of the three subscription options.

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.Subscribe now****************

Data

At moments of structural change, it is the weighting schemes that are used to construct price indices that come under pressure. Price index numbers are based on the assumption that the proportion of spending on food, clothing, housing, travel etc remain relatively constant over time. As the FT explains, statisticians face a dilemma as to whether to hold the share of different goods in the consumption basket constant, or whether to adjust to the new circumstances. Transport spending is down, whereas other goods and services are up. Unsurprisingly, the prices for transport services are rising less fast than for everything else. If you adjust the weights to downgrade the lower level of spending on travel, you produce a higher inflation number.

This is one of the effects driving inflation above 4 percent in Germany right now. As Bloomberg explains:

For some technical background check out this NBER paper.

Of course, consumption patterns also vary interpersonally. We all have our own personal strategies for adjusting to COVID. To allow for this problem, the WSJ offered an app that allowed its readers to calculate their own price index.

It this a historic first? America’s leading business newspaper offering us a statistical app to capture our personal “inflation truth”?

Baselines

A far more elementary problem with the inflation indices than the question of weighting, is the question of the baseline that we use to measure inflation.

Following a shock like 2020, using year-on-year measures of inflation produces a long-lasting echo. The exceptionally depressed level of prices in 2020 makes for remarkable inflation readings in 2021.

As Martin Sandbu points out in a typically level-headed piece, all you have to do to eliminate this effect is to take inflation readings month on month. Measured month-on-month inflation in the United States has been decelerating since the spring of 2021.

General v. particular

A point that cannot be emphasized strongly enough is that the conventional “macro” view of inflation defines it as a “general increase in prices”. The emphasis is on the word “general”.

For conventional analysis this assumption is essential.

The point is to distinguish between the underlying causes of price increases. Is the increase in the index the result of a surge in oil prices, driven by the idiosyncratic politics of OPEC+? Or, is the index capturing a widespread increase in prices across the board? The latter might be more moderate in percentage terms, but it might well reflect a more fundamental imbalance in the economy. Macroeconomics – certainly the kitchen sink variety invoked in mainstream commentary – would likely attribute this to an excess of money in circulation, or an excess in aggregate demand, aka “running the economy hot”. Addressing inflation in this more general sense clearly requires a different remedy than addressing an OPEC production cap.

If we take this distinction between general and particular causes seriously, the sort of inflation that most lends itself to macroeconomic analysis is the kind in which all prices move together. A true (macroeconomic) inflation is one where the price index increases and this is attributable to roughly proportional increases across a large number of sub-components. An increase in the overall index associated with a surge in price dispersion is far harder to interpret.

The degree of co-movement or dispersion within commonly-used price indices does not attract as much attention as you might expect. But it is at the heart of our current perplexity.

On the dispersion point, this piece by Macro Chronicles is particularly instructive. It shows a considerable increase in dispersion between early 2020 and 2021.

Not only did the average inflation rate (red dashed line) shift to the right between 2018 and 2021, but the dispersion of different inflation rates across the components of the index, as measured by standard deviation (dotted back line), increased dramatically.

There have been many excellent pieces about supply-chain obstructions, the price of lumber etc. But without doubt the most entertaining and weirdly instructive was this by Tracy Alloway on Mayonnaise inflation. You learn more than you may ever want to know about Mayonnaise, but much else besides.

What all these data issues add up to is a simple but important point.

Before getting too worked up about the inability of economists to read our current situation, we should recognize that it is, at least according to these measures, objectively hard to analyze.

Lowflation

Even before the 2020 shock, central banks were struggling to formulate a new approach to monetary policy. First the Fed in August 2020 and then the ECB issued new policy frameworks. Both of their policy moves shifted the balance of policy-making towards a more inflationary position.

This reflected the fact that neither bank had recently had much success in achieving inflation targets of 2 percent. They had tried very loose monetary policy but with little effect. They were afraid therefore of systematically biasing towards lowflation or even deflation.

As is explained in an excellent new Substack by Duncan Weldon, the central bankers will admit that they do not have a good model of inflation.

To make this point, Duncan cites a recent speech by Charles Goodhart at the annual European gathering of policy-makers at Sintra. You can see the video here.

In his typically succinct style, Goodhart laid out the problem: Neither the simple monetary theory of inflation (too much money chasing too few goods), nor the Phillips curve model (too low unemployment driving excess demand) provided much insight into persistent low inflation.

The ECB has just issued a thorough assessment of its consistent tendency to over-predict inflation.

The result, was that central bankers in practice focused less on fundamentals and more on a rather nebulous notion of inflation expectations. If businesses, consumers and workers converged on some rate of inflation that they expected, then their actions, conditioned on that belief, would likely validate that rate of inflation. So inflation control was about anchoring expectations. That in turn explains all the carefully scripted talking that central bankers do.

What to expect when you are expecting (h/t Claudia Sahm )

But how seriously should we take this somewhat circular conception of inflation as driven by inflation expectation? From inside the Fed itself it has been subject to withering criticism by Jeremy Rudd.

Rudd’s paper has taken the internet and indeed the media by storm. He is skeptical that expectations can be measured in a meaningful way or that the expectations we can measure have any meaningful relationship to inflationary processes.

For an excellent appreciation of Rudd’s intervention and its politics see this post by Claudia Sahm. As Sahm points out, Rudd and his colleagues have been warning since 2014 that the Fed does not have a robust inflation model.

“In January 2014—over seven years ago—Alan Detmeister, Jean-Philippe Laforte, and Jeremy Rudd wrote a memo to the FOMC, delivering some bad news about inflation:

The observed evolution of the empirical inflation process over time, the difficulty we [the staff] often have in explaining historical inflation developments in terms of fundamentals, and the lack of a consensus theoretical or empirical model of inflation all contribute to making our understanding of inflation dynamics—and our ability to reliably predict inflation—extremely imperfect.

Fedspeak translation: We don’t know what’s driving inflation. You don’t either. The memo also discusses why inflation expectations aren’t likely a good explanation.”

Unsurprisingly Rudd’s intervention is eliciting pushback from macroeconomists. Among the most forceful is Ricardo Reis. He offers this excellent thread on the issue.

For most surveys of expected inflation, is the median a good statistical forecaster of future inflation? Usually not.

— Ricardo Reis (@R2Rsquared) October 3, 2021

But does this mean that expected inflation does not matter to understand inflation? Absolutely not.

Forecasting is not the same as understanding, or mattering.

The jist according to Rais: inflation expectations may not be good short-term predictors. But that is not surprising. It would be naive to suggest that this makes them unimportant. And this is particularly the case when what is at stake is a regime-shift.

Watch this space!

Inflation politics

At this point, if not before, politics definitely enters the picture. We are engaged in a gigantic live experiment with an unprecedented combination of fiscal and monetary policies and a unique supply-shock. Both in the United States and Europe, the political balance is delicately poised. Unsurprisingly, passions are running high.

The message may be couched in technical language, as in this tweet, but the American Enterprise Institute wants Chairman Powell to tighten policy. From the old center of the Democratic Party, Larry Summers, who once argued for a 3-4 inflation target, has been sounding the alarm.

In Europe, and in Germany, in particular, the scare mongering has been so intense that it provoked the doughty Isabel Schnabel into a vigorous counterattack.

That a German central banker would ever launch a slide like this, calling out not just Bild, but Der Spiegel too, would once have been unthinkable.

Neo-Keynesian opportunity

What makes the current moment particularly interesting is that the inflation debate is not confined to central bank economists and the mainstream of academic economics. There are powerful voices from the neo-Keynesian left-wing, who thanks to connections forged over the last ten years (we need to talk more about the Occupy moment and the New York scene) are gaining a real hearing.

The argument is particularly interesting because it calls into question what exactly inflation is. It hones in on that all-important distinction between inflation in general and price increases in particular. In this particular moment, are we in fact dealing with inflation in general at all? Or, is what we are seeing simply the result of particular causes operating across a variety of different sectors. If the latter then the application of restrictive monetary and fiscal policies to cure it would be disastrously inefficient.

J.W. Mason has spelled out the argument in an interview with Eric Levitz in New York magazine, which I have recirculated several times, and in this more technical blogpost.

One of the things that is particularly interesting about the neo-Keynesian intervention in the current situation is that they are forcing a reevaluation of the historical inflation record.

Debating inflation history.

For those anxious about inflation, the standard references point are the 1970s, when inflation in the US and other rich countries accelerated into the teens and was stopped after 1979 by harsh action by the Fed. But what if our current moment is more like the 1950s inflationary episode associated with the aftermath of World War II and the Korean war?

That question, believe it or not, has made it into the pages of the Financial Times, courtesy of the excellent column written by @rbrtrmstrng

A series of exchanges ensued in which Gabriel Mathy, Skanda Amarnath and Alex Williams outlined an argument that suggested that early 1950s experience should be seen as a reason to take a relatively relaxed view to our current situation and to reevaluate the role of price controls. There was a response by Larry Summers & Nouriel Roubini who are not reassured by the 1950s experience. And a comeback from MAW

The longer former of the neo-Keynesian argument can be found at the Employ America site.

This thread from Skanda Amaranth is instructive:

Overdue thread on the piece @rbrtrmstrng kindly featured and Larry Summers hated…from @gabriel_mathy, @vebaccount, & yours truly.

— Skanda Amarnath ( Neoliberal Sellout ) (@IrvingSwisher) September 24, 2021

Policymaking is based on flaky explanations for the 70s inflation, but they look even flakier when used to explain the 50s 1/https://t.co/SB3VThsb32 https://t.co/62Iq4kNbBQ

Piling onto the debate, Tim Barker weighs in at The History of the Present blog on the true history of Fed policy in the 1950s.

An important intervention from @_TimBarker on the political economy of the 1950s. TLDR: the Fed was hawkish on inflation far before 1979. https://t.co/PzAwCwCnvh

— David Stein (@DavidpStein) September 24, 2021

Taking up the cause, Andrew Elrod in the Boston Review argues: “So long as journalists and thinkers continue to imagine “inflation” as a monolithic historical experience, … a serious discussion of how to think about inflation will be impossible.”

To remedy this problem he offers a fascinating reconstruction of America’s inflation history since 1945, focusing on the episode in the 1950s and 1970s.

The upshot is that inflation is not always a matter of total excess demand. It can also result from sectoral mismatches of supply and demand. If this is the case then restricting aggregate demand is a blunt instrument with side effects that have scarred America’s political economy for the last fifty years.