Adam Tooze's Blog

September 8, 2023

Ones & Tooze: The Economic Philosophy of George Soros

Billionaire George Soros has been funding democracy promotion around the world for decades, through his Open Society Foundation. For his efforts, he’s become a bogeyman for the far right. But what economic philosophies drive Soros’s charity work? And how do they align with the business strategies that made him so fabulously wealthy? Adam and Cameron dig in.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

Chartbook 238: Making & remaking the most important market in the world. Or why everyone should read Menand and Younger on Treasuries.

“The market for U.S. government debt (Treasuries) forms the bedrock of the global financial system.

The ability of investors to sell Treasuries quickly, cheaply, and at scale has led to an assumption, in many places enshrined in law, that Treasuries are nearly equivalent to cash. Yet in recent years Treasury market liquidity has evaporated on several occasions and, in 2020, the market’s near collapse led to the most aggressive central bank intervention in history. … a high degree of convertibility between Treasuries and cash generally requires intermediaries that can augment the money supply, absorbing sales by expanding their balance sheets on both sides. The historical depth of the Treasury market was in large part the result of a concerted effort by policymakers to nurture and support such balance sheet capacity at a collection of non bankbroker-dealers. In 2008, the ability of these intermediaries to augment the money supply became impaired as investors lost confidence in their money-like liabilities (known as repos). Subsequent changes to market structure pushed substantial Treasury dealing further beyond the bank regulatory perimeter, leaving public finance increasingly dependent on high-frequency traders and hedge funds—“shadow dealers.” The near money issued by these intermediaries proved highly unstable in 2020. Policy makers are now focused on reforming Treasury market structure so that Treasuries remain the world’s most liquid asset class. Successful reform likely requires a legal framework that, among other things, supports elastic intermediation capacity through balance sheets thatcan expand and contract as needed to meet market needs.”

This is the abstract for an essay modestly entitled “Money and public debt: Treasury Market Liquidity as a Legal Phenomenon” – the latest block buster collaboration from Lev Menand of Columbia University and Josh Younger (ex of JP Morgan now NY Fed) – in the Columbia Business Law Review.

My aim here is to amplify their crucial arguments. Everyone interested in global finance should read the article. If you are looking for a shorter summary, read Alexandra Scaggs’s excellent piece at the FT.

***

The essential starting point of the Menand and Younger account is the basic insight that

American public finance has long been closely intertwined with the American monetary framework and that deep and liquid Treasury markets are, in large part, a legal phenomenon. Treasury market liquidity, in other words, did not arise organically as a product primarily of private ordering. Instead, it was actively constructed by government officials. The high degree of convertibility between Treasury securities and cash—the market’s “liquidity”—depends upon entities that can create new, money-like claims to buy Treasuries. Sometimes the government’s central bank has issued these claims directly, as in March 2020; other times these claims were issued by central bank-backed instrumentalities, such as banks and select broker-dealers.

They connect here to three important strands of thinking about money and finance: the idea that the state money-finances its spending (MMT/Tankus et al), the political economy of financial markets (Braun, Gabor et al), the legal construction of finance (Pistor et al).

The key point is that the issuance of public debt goes in hand with the issuance of credit and money in a public-private partnership.

United States has never relied exclusively, or even primarily, on money instruments issued directly by government agencies. Instead, since the Founding, the government has outsourced money augmentation. By design, investor-owned enterprises—typically, chartered banks—have been the predominant money issuers in the economy. And the federal government, recognizing this, has set terms and conditions for their money creation.

The early stages of America’s modern monetary history nicely illustrates the point.

Between 1863 and 1916, Congress established a network of investor-owned federal corporations—national banks—to serve as the country’s primary money-issuing institutions and required that these instrumentalities back their paper notes with Treasuries. … In doing so, the federal government conjured captive demand for federal debt. Although, under the resulting legal regime, the government formally borrowed to manage deficits, it borrowed in significant part by selling Treasuries to national banks, which, in turn, funded their purchases with newly issued notes and deposits.

After the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913 and under the pressure of World War I finance,

Congress adjusted the law so that the Fed could incentivize banks to purchase Treasuries with newly issued deposits. Under this second configuration, government officials actively managed debt monetization by deposit-creating banks. Less than thirty years later, when the U.S. joined the Allied effort in World War II, the Fed went even further. It bought large quantities of Treasuries directly and administered prices for Treasury debt, pegging short-and-long-term Treasury rates using its own balance sheet—monetary finance ..

Up to 1951 there was thus a relatively direct conveyor belt that shuffled initially small volumes of debt and then (with the world wars) larger volumes directly onto the balance sheets of state-backed banks with money issuing privileges, or commercial banks that issued credit to their private clients and were back-stopped by the Fed.

As Menand and Younger highlight, the elasticity of the system in the 1940s was spectacular:

In total, the stock of … direct obligations of the government more than doubled relative to economic activity—from 43% of GDP in 1939 to more than 110% in 1945. To put this in a more recognizable, modern context, if we size a similar program to 2019 GDP it was as if the Treasury was able to issue more $40 trillion of new Treasuries over just a few years.

Up to the mid-century, secondary markets for already-issued government debt, what we think of today as the “bond market”, did not play a major role in the US monetary and fiscal nexus. In the 1950s this changed, with a deliberate policy decision to shift conduits of Treasury financing away from bank balance sheets attached to the Fed and instead to place Treasuries, through the capital markets (where bonds are bought and sold daily) with a much wider array of investors. This decision was motivated by the realization that a system for absorbing Treasuries based on bank balance sheets, left the banking system “clogged up” and inelastic.

Menand and Younger illustrate the shift in the debt-money nexus from a bank to a capital market model with a dramatic graph. Before 1914 almost two thirds of America’s very limited public debt was held by banks. By the early 2000s banks held a tiny fraction of a gigantic debt pile.

**

It might be tempting to think of this switch from banks to capital markets, as a retreat by the Fed. But not only did the Fed’s share of public debt ownership barely decline after World War II, but as Menand and Younger show, it was the Fed that was key to enabling the vast bulk of US Treasuries to be held outside the US banking system, through a new set of relationships with participants in capital markets.

As a major hiccup in 1953 revealed, for a large and dynamic market in Treasuries to be other than dysfunctional, it needed backstops and this required “creative lawyering and ongoing government support”. And so, to help stabilize the new market for Treasuries, the Fed set about developing and supporting the sale-and-repurchase agreement, or “repo.”

A repo is economically equivalent to a secured loan but structured as a sale of a bond combined with an agreement to repurchase that bond at an adjusted price on a date specified in advance. When the first and second transaction in a repo are spaced a day apart (and made exempt from the bankruptcy process), repos function (in certain respects) like bank deposits. Dealer firms, therefore, could conduct overnight repo transactions primarily with nonbank corporate “depositors,” effectively money-financing their operations.

The new role of the Fed as manager of the capital market-Treasury funding mechanism rather than the bank-based-Treasury funding mechanism, was to backstop the repo market.

The Fed did not indiscriminately extend this support to all comers but instead designated an inside group of “primary dealers”. Initially there were 18 primary designated in 1960. The number grew to 46 by 1988 before declining to 21 in 2007.

These were not high street banks benefiting from deposit insurance and intensive regulation, but market-facing investment banks – both US and foreign – and bond dealerships. Their access to Fed repos meant they could build a deep and liquid market for end-investors to buy Treasuries in the safe knowledge that they could always be repoed for cash with the primary dealers, with the Fed acting as the guarantor of the final link in the chain.

Developed with active Fed backing and defended against obstructive regulatory changes – crucially to exclude repoed collateral from any bankrupty proceedings – the repo system expanded “from roughly $2 billion in the early 1960s, to $12 billion in the late 1970s, to more than $300 billion in the mid-1980s.” From there it continued to progress.

The Fed-backed, primary dealer-managed Treasury market, operating on the basis of repos, was the anchor not just of America’s financial system, but that of the entire capitalist economic world. In the 1980s, 70-80 percent of reserves worldwide were held in dollar-denominated assets. Treasuries were the most liquid and widely traded US asset for foreign reserve holders. And roughly 30 percent of US Treasuries outstanding were in non-American hands.

By the early 2000s, with private bonds, and large packages of mortgage-backed debt entering the system, the repo market was churning many trillions of dollars in credit per day. In 2007 daily turnover reached a remarkable 13% of total marketable Treasury debt. And the primary dealers were operating with leverage of 47x their capital base. Despite the huge volumes and the hair-trigger responses of a market that was in effect offering trillions of dollars in overnight finance, the risks seemed manageable because, in the last instance, a primary dealer could always access the Fed backstop for their Treasury portfolio.

It was this system that imploded in 2008, with huge “runs on repo” the most famous victim of which was Lehman.

Through massive liquidity provision the Fed prevented a total collapse. But, though this forestalled an implosion, the pre-2008 structure did not survive. The elite group of primary dealers were shaken to their foundations and over the coming years, they either folded (Lehman) or were bought out and absorbed by bigger banks (Bear Stearns by J.P. Morgan Chase, Merrill Lynch by Bank of America), or formed their own bank holding companies (Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley), thus coming under the protection of deposit insurance and comprehensive bank supervision.

As Menand and Younger comment: “Though smaller dealers remained independent (e.g., Jeffries, Cantor Fitzgerald), for the first time in modern financial history (i.e. since the formation of a large secondary market in Treasuries in the 1950s) the majority of dealer activity was performed within BHCs.” The capital market-based-non-bank-primary dealer model first shaped in the 1950s was finished.

**

Though in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis much attention was paid to the systemic stability of the banking system, what received less attention was the stability of major financial markets. And yet the implications of regulatory change for banks for the wider markets was significant.

Having been absorbed into the banking system, the primary dealers fell under far more strict regulations applying to Bank Holding Companies and then to the global Basel III rules. To reduce the risk of a systemically important mega-bank getting into serious trouble, these regulations were designed to dissuade big banks (which now controlled the primary dealers in Treasuries) from engaging in very high volume, highly leveraged, low margin business, like running large repo books. This reduced the elasticity of the Treasury markets.

Despite the huge surge in Treasury issuance with gaping Federal deficits after 2008, this increasing rigidity in the capital market was not immediately obvious for two reasons.

First, the Fed was itself buying Treasuries in huge volumes.

Second, new financial actors emerged to take up some of the market vacated by the more tightly regulated bank-primary-dealers. As Menand and Younger put it:

new actors further beyond the bank regulatory perimeter, high-frequency traders (HFTs) and hedge funds, stepped in. Some refer to these entities as “shadow dealers,” as they are incentivized to serve the same economic function as dealer firms but are not currently subject to regulation as dealers (and are not required or expected to support the market to the same extent as dealers).

The growth in the new non-bank “shadow dealers” kept the market functioning, but from 2017 onwards pressures increased.

The Trump tax cut pushed the Federal deficit from 2.4% of GDP in 2015 to 4.6 % in 2019, an unprecedented number at a time of near full employment. Public debt in private hands increased by $2.7 trillion from 2017 to 2019. At the same time, the Fed was unwinding its QE purchases and America’s big banks had no appetite to expand their holdings of Treasuries. Increasingly, the Treasury market migrated back towards lightly regulated non-bank players.

Into the place of the old primary dealers stepped so-called principal trading firms (PTFs) and other high-frequency traders (HFTs) that earned margins on trade matching. At the same time hedge funds devised new strategies that incentivized them to hold long positions, effectively functioning as inventory managers for the market. Hedge funds gobbled up whatever balance sheet capacity was offered to them by the big banks, for fearing of losing their “allocation”.

The result was a build up of Treasury holdings in the hands of lightly regulated but highly leveraged balance sheets. Menand and Younger summarize as follows:

SEC Private Funds Statistics … show a rapid increase in gross exposure to Treasuries among the hedge funds in their sample, which had remained around $1 trillion from early 2014 (the earliest data available) until the fourth quarter of 2018,367nearly doubling to $2.2 trillion by the end of 2019.

It was this fragile patchwork of bank and non-bank actors in the US Treasury market that imploded in March 2020 under the impact of the COVID shock. Menand and Younger offer by far the most compelling account of the Treasury market dysfunction of March 2022 to date. I reproduce here only the briefest summary:

… in 2020, the onset of the pandemic revealed that shadow dealers, which were often much more thinly capitalized than commercial banks and lacked explicit or implicit access to central bank backstopping, were extremely vulnerable to run-like dynamics in the face of market volatility. Just when private intermediaries, including hedge funds and high-frequency traders as well as securities dealers, were most needed to warehouse a deluge of sales by end-investors in a largely one-sided market, these firms stepped back in unison.

Menand and Younger hedge their bets on the role of the big bank-primary dealers in the March 2020 spasm.

Size constraints may not have been strictly binding on the banking system or individual bank holding companies at the time, but they created a brittle internal arrangement that acted as an amplifier of market volatility.

Younger had a front seat in the action at JP Morgan and he did a huge service to the analytic community at the time with his commentary on market dynamics.

In any case, the role of particular big banks is not the key issue. From a historical point of view the key point is that under massive stress, the basic legal, financial and, ultimately, political structure that underpins the interlinked public and private system of money and public debt was starkly revealed:

The day was saved only by a dramatic intervention by the Fed, which used its balance sheet to absorb supply and smooth out price fluctuations. It was what Chairman Martin (chairman of the Fed between 1951 and 1970) had aimed to avoid: direct central bank intervention undergirding federal finance.

**

The disturbance of spring 2020 was both profoundly alarming and dangerous. Whether you regard the denouement – direct Fed stabilization – as a disaster depends on your worldview. It depends on how squarely you are willing to face the historical fact that our modern monetary and fiscal constitution profoundly entangles the state and the private financial system and it is the central bank that forms the ultimate backstop. You can reasonably advocate for a system that is even more transparently backstopped by the central bank. You can also reasonably prefer a new iteration of public-private partnership with new rules, new participants and new backstops. What Menand and Younger’s wonderful essay shows to be a fantasy is any idea of a fiscal and monetary system based on rigid separation, a “free” capital market, or a “privatized” money supply.

As Menand and Younger conclude, these questions are urgent. We are entering

… a critical phase in the financial history of the U.S. and the dollar. The trajectory of mandatory federal spending points to a secular widening of deficits over the medium-to long-term. Ensuring markets keep pace with that growth remains, as Chairman Martin observed back in 1959, “obviously needed for the functioning of our financial mechanism.” Absent reform, one possibility is another panic.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

September 3, 2023

Chartbook 237: Whither China? (4): Zero-Covid myths, dynamic clearing & the Omicron crisis of 2022

Politicized memory plays strange tricks. To listen to influential Western voices in 2023 you might imagine that China emerged in December 2022 from long confinement in a zero-COVID prison, a regime dictated by the vanity of Xi Jinping, a regime which inflicted years of comprehensive and repressive lockdowns on a hapless population and revealed the threat posed by the unfettered power of the CCP.

This is how Adam Posen begins his much-discussed Foreign Affairs article:

After three years of stringent restrictions on movement, mandatory mass testing, and interminable lockdowns, the Chinese government had suddenly decided to abandon its “zero COVID” policy, which had suppressed demand, hampered manufacturing, roiled supply lines, and produced the most significant slowdown that the country’s economy had seen since pro-market reforms began in the late 1970s.

Source: Foreign Affairs

Listening to the Checks and Balances pod from the Economist I heard a contributor casually remark, “for 2 years China stifled its economy with zero Covid”, or words to that effect.

This is, to say the least, an audacious rewriting of history and reflects the way events that took place as recently as 18 months ago are subject to reinterpretation in light of the new, overwhelmingly negative narrative.

***

The idea of zero-covid as a policy of sustained repression conforms to Western preconceptions about Xi’s regime. And it is true that between 2020 and 2023 it was hard for anyone from outside to visit China. It is also true that the Shanghai lockdown in the spring of 2022 was draconian and that in the second half of 2022 increasingly unpredictable and radical measures were taken across China. The most extraordinary of all were the “closed-loop” factories operating under inhuman quarantine conditions.

It is undeniable that by December 2022 Xi Jinping’s regime was forced into a humiliating climb down, accompanied by significant economic damage, a collapse in confidence, unprecedented streets protests and, over the winter of 2022-2023, a large-scale loss of life. But this is not a story of “the last three years”, stretching back to the original lockdowns in China in January and February 2020. For much of 2020 and 2021 the successs of zero-covid meant that China’s pandemic containment on the ground was less repressive than in many parts of the West. It was the Omicron mutation that turned a highly successful policy into a fiasco. Many will remember the scenes of partying in Wuhan in the summer of 2020.

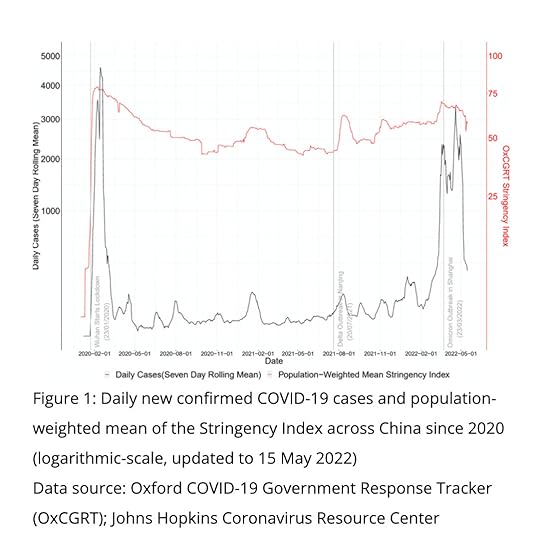

If you consult standard COVID response trackers you can see the way in which stringency in China varied over time.

Source: Hale et al 2022

This was the logic of what became known as the “dynamic clearing” model which operated successfully in 2021. As Gavekal explained:

Although often referred to as a “zero-Covid” strategy, dynamic clearing was actually adopted after it became clear that it was no longer possible to keep new case numbers at zero. The goal was instead to ensure that case numbers were at least heading to zero in every locality with an outbreak. As long as each outbreak is relatively isolated, it can be contained by restrictions in only the affected area, limiting the disruption and allowing the government to concentrate attention and resources where they are most needed.

It is easy to conflate the on-off quality of dynamic clearing with the original sin of unfettered CCP authority. But actually it followed a short sharp shock logic of pandemic containment. It was uncomfortable to live with, but was not arbitrary. And in 2021 it was highly successful allowing Delta to be stamped out.

Faced with Omicron it was clear that there would be bigger problems. Discussions about lifting restrictions began in earnest in Beijing at the end of 2021 and as early as March 2022, top medical experts submitted a detailed reopening strategy to the State Council, China’s cabinet. But before steps could be taken Omicron arrived in Shanghai and without a tried and tested alternative on hand, the authorities responded in familiar style with a massive and comprehensive lockdown.

In 2021 in Shanghai the anti-Delta measures had offered a reasonable trade off. In 2022 the lockdown was much longer and more damaging in its impact.

But even in 2022 it is a myth to claim that zero COVID required blanket application of lockdowns. According to the Gavekal tracker, in June 2022 cities acounting for 40 percent of GDP had abandoned all lockdown measures and two thirds of the Chinese economy was under Level 1 or below. This was the strategy of dynamic clearance in operation: not blanket and endless lockdowns, but tactical decisions taken on a case by case basis to stamp out local outbreaks, followed by quick reversal.

Over the summer, having achieved clearance, Shanghai relaxed. But the Omicron infection now spread to several other cities that did not have Shanghai’s resources. Notably in the Western provinces, containment began to breakdown. Within a matter of weeks Beijing lost control. As the decisive 20th Party Congress approached in October, for the first time since the pandemic began, Omicron was running rampant across the country.

Xi’s timeline was dominated by the Party Congress in mid-October. As soon as that was over, the debate about the future of zero Covid began in earnest. Leading health experts like Wu Zunyou, China’s CDC chief epidemiologist, called on October 28 for measures to be relaxed, criticizing Beijing city government for draconian controls that had “no scientific basis.” He scolded the municipality for a “distortion” of the central government’s zero-COVID policy, which risked “intensifying public sentiment and causing social dissatisfaction.”

In early November, then-Vice Premier Sun Chunlan, China’s top “COVID czar,” summoned experts from sectors including health, travel and the economy to discuss adjusting Beijing’s virus policies. This resulted in Xi’s orders on November 10 to adopt 20 new measures to optimize the policy response, including tweaking restrictions, such as reclassifying risk zones and reducing quarantine times.

These efforts to optimize policy only added confusion. The effort to liberalize, ironically, made decisions at every level of government, less not more predictable. This is how Gavekal’s researchers described the breakdown of control in the autumn of 2022:

The central government tried to correct the problem by announcing 20 measures to “optimize” Covid policy, which aimed to limit the administrative and fiscal burden on local governments and thus allow them to concentrate more effectively on the necessary measures to contain the virus. But the reception and interpretation of these optimization measures was confused, with several cities relaxing their Covid restrictions even as case numbers spiraled. Those decisions allowed outbreaks to become even larger and more widespread, and thus increasingly difficult to control. By last week, many cities had reversed course after the “optimized” measures failed to slow the spread. Two cities whose loose approach to Covid controls drew nationwide attention, Shijiazhuang and Zhengzhou, both re-imposed tough lockdowns as their outbreaks spiraled out of control. And many other large cities that had been trying to manage with only targeted restrictions have gotten more aggressive: Chengdu and Tianjin have both imposed city-wide restrictions on retail services over the past few days, and expanded residential lockdowns to wider areas. … Covid restrictions began to sharply intensify around November 19, just a week after the first announcement of the optimized policies. These reversals—which seemed to go against the central government’s promise of less invasive Covid controls—were the context for the sizable protests that broke out starting November 25. Local governments were already reluctant to use aggressive measures to contain Covid transmission, and will be even more so now as they will try to avoid direct confrontations with the public … Urumqi, where the protests began, quickly announced a partial reopening of public transportation and businesses even though it has not gotten new cases fully under control after more than three months of lockdown. In Beijing, where there were also many protests over the weekend, the local government has relaxed restrictions in several areas even though case numbers are still high. But the experience of Urumqi and other large cities struggling to contain outbreaks suggests that the “dynamic clearing” approach was already breaking down even before the protests, for a couple of reasons. … Now, outbreaks are no longer isolated, which increases the strain on government capacity and makes every outbreak harder to control. As of November 27, 306 of China’s cities, over 85% of the total cities that directly report such data, were reporting new Covid cases, the highest figure on record and twice the level before the “optimization” of policy. Targeted restrictions on individual buildings and neighborhoods, the optimized strategy envisioned by the central government, are extremely unlikely to be consistently effective in this environment.

Throughout November the debate raged about how to proceed. Xi’s preference, apparently, was to crackdown with ever greater force. But the telling point is that Xi did not get his way. Fresh from the Shanghai battlefield, the new #2 Li Qiang insisted that the costs were too high. The economy was clearly suffering. Protestors made the point loud and clear.

At the city level the resources for implementing tough testing and quarantine regimes were running out. As Reuters reported:

A local leader of a sub-district in Beijing with over 100,000 residents told Reuters that by the second half of last year it had run out of money to pay testing companies and security firms to enforce restrictions. “From my perspective, it’s not that we set out to relax the zero-COVID policy, it’s more that we at the local level were simply not able to enforce the zero-COVID policy anymore,” the official said. Beijing’s local government, which did not respond to a request for comment, spent nearly 30 billion yuan ($4.35 billion) on COVID prevention and controls last year, official data show.

At the G20 in Bali on November 14 during his meetings with Biden and Trudeau Xi showed himself without a mask. But at home he continue to take a hard line, demanding the “unswerving” execution of zero-COVID. But that was increasingly unrealistic. And as Li repeatedly emphasized the economics costs were mounting up. In meetings with Xi on November 19 after his return from the G20 trip, Li resisted Xi’s pressure to react to ever worse infection numbers by slowing the pace of reopening.

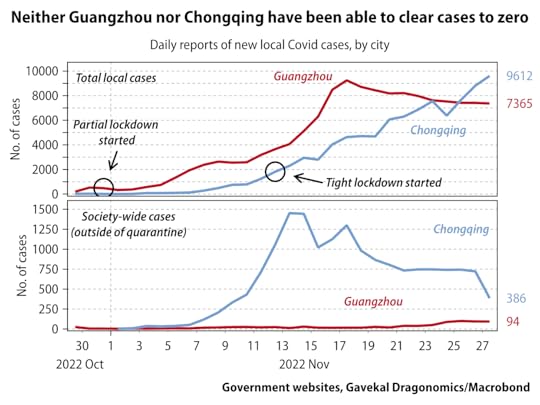

By the end of November it was clear that the outbreak in the two megacities of Guangzhou and Chongqing could no longer be contained. Both cities had adopted aggressive lockdown strategies but the case load was no longer reacting.

Rather than following Xi’s preference, or the more gradual timeline preferred by health experts, the decision was taken to accept the price in terms of life and to announce a complete end to all measures in early December.

It is hard to see how you turn this narrative into one of pigheaded and arbitrary repression. It is far more plausible to see it as an effort first at dynamic clearing and then optimization, an effort to minimize the impact on society and economy, which was successful in 2021 but failed when faced with Omicron. This exposed the limitations of local government resulting in an increasingly haphazard and incoherent policy. Once the failure was apparent, within a matter of weeks, despite the reputational cost, the repressive impulses of Xi were overruled and the regime opted to prioritize public order and economic recovery.

***

Of course, the pandemic period saw huge global economic uncertainty. But even in 2020 the regime was highly sensitive to the need to maintain production. And by the summer of 2020 the Chinese economy stood out globally precisely for the strength of its rebound from the first COVID shock.

From the last quarter of 2020 throug the end of 2021 subway ridership in Chinese citie was normal 2019 levels. No sign of any lockdown.

Rather than being consumed by emergency measures, as in Europe and the US, it was the success of zero COVID that set the stage for the regime to take a series of fateful strategic decisions on Hong Kong, tech platforms and housing, which betokened its sense of control and dominance. The trajectory of the Chinese economy in 2020 and 2021 was dominated not by a general downturn driven by zero-COVID but by the divergent forces on the one hand of booming exports driven by a huge surge in global demand and by the deflationary effect of pricking the housing bubble.

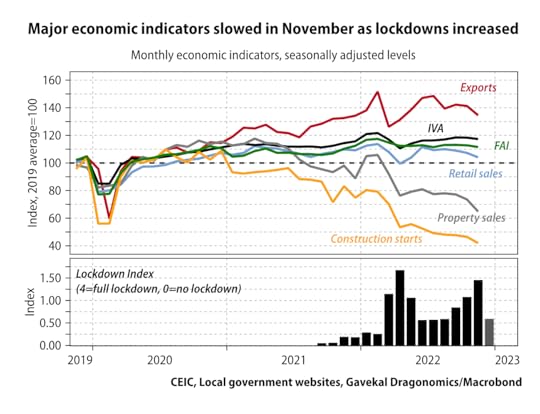

Source: Gavekal

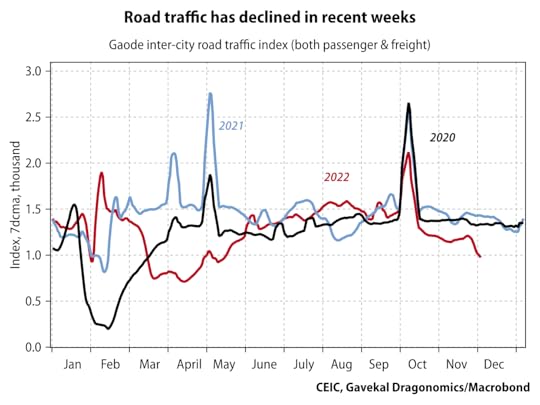

The impact of the Omicron lockdowns in 2022 was doubly damaging, threatening to disrupt the export supply chains and to intensify the depressed mood in the housing market. But the basic pattern of China’s economic development was set by exports and housing and not by the debacle of COVID policy. The road traffic index shows a significant slowdown in March and April 2022 which reflects the Shanghai lockdown. But from June until October it closely tracked previous years. Only in October did the new wave of lockdowns begin to bite in earnest.

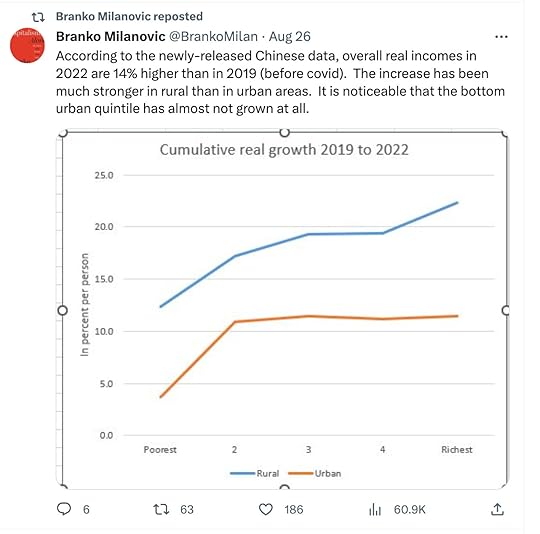

If you look at overall growth data for the period 2019 to 2023 as Branko Milanovic recently did in the course of inequality research you see the following

The impact of successive shocks on low-income workers in cities is clear from the data. But so is sustained progress overall. If these data are to be believed they give the lie to idea of 3 years of stagnation.

***

Up to 2022 the ultimate vindication of China’s zero covid policy was that it had saved lives. The contrast in mortality between China and much of the rest of the world was spectacular. The regime’s prestige was tied up with that success. That was galling for the rest of the world, but hardly surprising. Imagine, for a second, the boasting, if the United States had been able to claim a similar record.

It didn’t last. But the incoherence of the regime’s eventual pivot is hardly remarkable . There isn’t a political system in the world that can claim to have followed a policy towards COVID that was coherent or able to track the twist and turns of the virus. What is remarkable about the Chinese trajectory are not its contradictions, so much as the suddenness of the pivot and its completeness. That was presumably a mixture of both panic and calculation. If you are going to abandon Zero Covid you might as well reap the full benefits in economic terms.

It is clear that Beijing was fully aware that this change of policy would cost lives and weighed that seriously. In meetings in October and November, Wang Huning, deputy head of the party’s central COVID taskforce since early 2020 and a member of China’s elite seven-man Politburo Standing Committee, repeatedly asked for estimates of how many people would die if zero COVID were abandoned. On that basis different timelines were prepared for the eventual exit.

We are unlikely ever to know the eventual death toll from the sudden abandonment of zero COVID. No good records have been published. But the forecasts were that between 1.3 and 2.1 million, mainly elderly Chinese would likely die. One recent studyusing proxies like Baidu searches suggests a figure of 1.87 million excess deaths over the winter of 2022-2023. That is a final horrifying addition to the global COVID death toll. Placed in relation to population it means that China eventually found itself with a middling mortality, with roughly half the number of dead in proportional terms than in the USA.

It is a sign of the times that this sad, but in the end rather familiar story should be interpreted as an expression of the peculiar dysfunctions of China’s regime.

**

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

September 1, 2023

Ones & Tooze: The Pencil as Economic Metaphor

Adam and Cameron discuss the common pencil—both a must-have back-to-school item and a metaphor for the free-market economy.

Also on the show: The economics of Mongolia.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

August 31, 2023

Book Review: Joe Biden’s First Term and the ‘West Wing’ Fantasy of American Politics

How will the history of the Biden administration be written: as the turning point when America began to heal or as a hiatus between moments of deadlock and adversity? Franklin Foer’s “The Last Politician,” an account of Biden’s first two years in office, is the first draft of an answer. It has the makings of high drama. Crisis follows crisis. The problem is that, from Biden’s bleak inauguration to the surprise result of the midterms, we know the story in advance.

Read the full review at The New York Times

August 30, 2023

Chartbook 236: Russia’s Long-War Economy

Is Russia’s war economy on the brink of crisis, or settling into a new “long-war” mode?

Subscribed

With the ruble having fallen to new lows and fear of inflation stalking the headlines, the Russian economy, in the 18 month of its war in Ukraine, is under pressure. For many Russians to see their currency plunging through the threshold of 100 roubles to the dollar came as a rude psychological shock.

Source: Trading Economics

Valdimir Solovyov, one of Russia’s best-known state TV presenters, bemoaned the situation: “What is happening in this country!? How did this exchange rate come about? Eventually, this will lead to a rise in consumer prices, and it will coincide with the election campaign,”.

Cameron Abadi and I took on the topic on the podcast. Check it out:

The shock at the sudden depreciation has exposed fault lines within the regime. Old rivals such as Putin’s chief economic advisor Maxim Oreshkin and central bank boss Elvira Nabiullina are openly squabbling, with Oreshkin putting the blame for the sudden depreciation at Nabiullina’s door. As he wrote in a recent article:

As these data demonstrate, the main source of ruble depreciation and inflation acceleration is loose monetary policy. The Central Bank has all the necessary tools to normalize the situation in the near future and ensure that lending rates are reduced to sustainable levels.

As the FT explained, Oreshkin blamed the rouble’s fall on the central bank after it eased monetary policy, which he said had led to an extra Rbs12.8tn in debt-fuelled demand that was overheating the economy. To try to stop the price rises, Deputy Trade and Industry Minister Viktor Yevtukhov met with retail chiefs to demand that they limit price rises for consumers.

And when Putin spoke to top economic officials recently his message was clear:

“Objective data shows that inflationary risks are increasing, and the task of reining in price growth is now the number one priority,” Putin said, with a note of tension in his voice. “I ask my colleagues in the government and the Central Bank to keep the situation under constant control.”

***

The West may take comfort in Putin’s worries. But the fact that exchange rates still matters, that the rising cost of imports impacts on the cost of living tells you something important and sobering. Despite sanctions, imports are still a significant factor in Russia’s economy.

In 2022 imports fall sharply, but have now recovered. The reason that the currency is depreciating is that exports have followed the opposite pattern. Exports boomed in 2022 and have now slumped under the double impact of global energy price movements and sanctions. The result is a shift in the demand and supply of rubles and foreign currency.

The slide of the ruble began in December 2022 just as new sanctions regime came into force – the EU oil embargo and the oil price cap imposed by the Group of Seven (G7) countries in December 2022.

The effectiveness of the sanctions is widely debated. Elina Ribakova offers an excellent analysis. Direct European purchases of Russian oil have stopped and Russia is accepting large discounts to sell oil through terminals in the Baltic and the Black Sea that have formerly served European buyers. The effect, ironically is to render the price cap part of the sanctions less relevant. With prices well below $60 per barrel from the terminals close to Europe, G7/EU providers of shipping services, including ship owners and insurance companies, are allowed to remain actively involved in the Russian trade, shipping oil to non-European customers. Meanwhile, at the Pacific Ocean ports that never supplied Europe, notably Kozmino, prices are well above the $60 barrel threshold and the price cap rules are being widely flaunted. EU shippers and insurers are heavily involved in the trade. There too, however, Russia is forced to offer discounts. The principal beneficiary so far is India.

Russia is no doubt finding numerous ways to undercut the sanctions, but the impact on its oil revenues is serious and this is showing up, directly and indirectly, in the balance of trade and the foreign exchange markets. Discounts for Russian oil have led to a significant drop in export earnings. In Q1 2023, Russia exported US $38.8 billion worth of crude oil and oil products, a 29% decline vs. the last quarter of 2022. The fall in oil earnings in turn hits fiscal revenues. Oil and gas tax revenues for the period January to April 2022 were 52% down on the same period last year.

None of this need have impacted Russia’s curent account balance or the exchange rate, if imports had adjusted equivalently. But the opposite has happened. Imports have bounced back strongly meaning that Russia’s account surplus – the excess of exports over imports – fell from $124 billion in January–May 2022 to $23 billion in the same time frame in 2023.

***

The other side of the sanctions system are the measures put in place to restrict Russia’s imports and they are working even less well than the system designed to limit Russia’s export revenues.

Russia does not pay for its imports only from current export revenue. After having much of its reserves impounded at the start of the war, the huge export surge of 2022 allowed Moscow to accumulate a large war chest in foreign exchange. In 2022 Russia saw net financial account inflows to the tune of US $283 billion last year. On top of the giant current account surplus of US $233 billion its coffers were flushed with returning resident capital. This was more than enough to offset the withdrawal of $130 billion in non-resident capital. With the Central Bank of Russia under sanctions, official balance of payments data show other Russian entities – banks and corporates – accumulating foreign assets to the tune of $147 billion of which half is held in the form of financial assets like loans and deposits. In 2023 these foreign exchange holdings are continuing to build, though at a slower rate.

Russsia’s new fx reserves, held particularly in Hong Kong and the UAE, provide it with huge purchasing power with which to break the import sanctions regime. As far as imports critical to the Russian war effort are concerned the figures are dramatic. According to the Yermak-McFaul working group, in 2022 Russian imports of critical components came to $26.0 billion, 16% down on 2021. But this was entirely due to the first impact of the war in March-June. By the end of the year, in Q4 2022 imports were running at $33.9 billion in annualized terms. If this has continued in 2023, and there is no reason to doubt that it has, it would imply that Russia is importing at a faster rate than before the war. Unsurprisingly, much of this is sourced from and via China with Hong Kong trading companies acting as intermediaries.

***

But the strong recovery of Russian imports is not just a matter of sanctions-busting and the nitty gritty of supply chains. In the aggregate, imports are a macroeconomic variable. The fall in Russia’s trade surplus tells you that Russia’s economy is running hot and demand for imported goods, even at higher prices, is strong. More generally, aggregate demand is straining against aggregate supply capacity.

It is, of course, true that Russia’s aggregate supply function is constrained. Mmny sectors of Russia’s economy has long suffered from underinvestment. And in some sectors, at least, the war is making that worse. Furthermore, Russia is suffering from labour shortages as a result of the war.

Already in December last year, Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina warned that “the capacity to expand production in the Russian economy is largely limited by the labour market conditions”. A survey conducted in July by the Gaidar Institute in Moscow found that 42 percent of enterprises surveyed complained of a lack of workers. It has been interpreted as a sign of desperation, Putin last week decreed that restrictions on employing teenagers as young as 14 should be lifted. According to data quoted by TASS, the number of workers under 35 in Russia is at its lowest share of the labour market since the early 1990s, with the most significant decrease in 2022 amongst those aged between 25 and 29. This is hardly surprising when Russia is drafting hundreds of thousands of men for the front. It is also no secret that the war has exacerbated Russia’s long-term “brain drain”. It is estimated that 10 percent of the high tech workforce left Russia in 2022. Altogether, emigration and mobilisation may have cost the Russian workforce approximately 2% of male workers aged 20-49 last year. By the end of 2022 the ratio of vacancies to jobseekers in Russia had risen to 2.5, as compared to the ratio of 1.6 in the USA today, which is generally reckoned to be at full employment.

***

But, serious as these supply restrictions are, there can be little doubt that the main factor causing the shift in Russia’s current account and the pressure in exchange markets is not so much a shortfall in aggregate supply as the strength of aggregate demand.

In a war economy this is not surprising. But in Russia, after many years of austerity, it comes as a considerable shock. Added to which, the central bank after tightening rates in the spring of 2022 to 20 percent, subsequently cut them to 7.5 percent, putting Nabiullina in the crosshairs of critique.

At the start of the war, I and others argued that military Keynesianism was the obvious way for Moscow to cushion the blow of sanctions and ensure home front stability. Some have referred to this as jackboot Keynesianism. James Galbraith has even gone so far as to speak of the “gift of sanctions”. He sees sanctions as a shock which has freed Russia from an economic policy regime that stunted its growth.

“We conclude that when applied to a large, resource-rich, technically proficient economy, after a period of shock and adjustments, sanctions are isomorphic to a strict policy of trade protection, industrial policy, and capital controls. These are policies that the Russian government could not plausibly have implemented, even in 2022, on its own initiative.”

For all that, Russia is running nothing like a total war economy.

Defense spending, at least according to official figures, will come to c. 9 trillion roubles in 2023, or c. $100 billion. By one estimate, that is c. 6.2 percent of Russian GDP. That is comparable to the height of Reagan’s rearmament boom in the 1980s. If we allow for some undercounting, Russian spending might be in the ballpark of US spending during the Vietnam war, at around 9-10 percent of GDP. It is certainly far short of the early Cold War effort at the time of the Korean War, let alone the kind of total war effort that Ukraine is being forced to mount.

It is enough, in any case, to give a healthy boost to many sectors of Russian industry and to aggregate demand overall. If we take Russian budgetary figures at face value, Russia’s economy is feeling the effects of shifting from a fiscal surplus in 2021 of 0.4 percent of GDP, to a deficit in 2022 and 2023 of 2 percent of GDP.

That is clearly far short of the kind of deficit that would trigger hyperinflation and a currency collapse. But it is a large stimulus and assuming that Moscow is not successful in achieving the consolidation that Putin charted in his comments on the budget at the end of 2022, the taps will stay open. Fiscal and monetary conservatives will bewail the short fall of revenues and the sudden flush of borrowing. But from the point of view of Russia’s eocnomy and home front stability, it seems obvious that the kind of modes deficits that Moscow is running are by far the better option than premature budgetary consolidation.

The effect is visible in strong growth in industrial sector favored in the war economy.

The construction sector is benefiting from demand generated by discounted mortgages: currently, 51% of loans come with state support.

***

Nor is this merely short-term. As Alexandra Prokopenko remarks in her analyis for The Bell:

The war in Ukraine is woven into the fabric of public life in Russia. Russia’s war in Ukraine is already in its 17th month. In that time, President Vladimir Putin has clearly demonstrated that he is not bothered by losses — whether they be financial, material, or human. His war will go on as long as he needs. And, judging by how the authorities have woven the so-called “special military operation” into Russian life, that will be a long time. The government has cash reserves and policy options (such as tax hikes) that mean the current level of military expenditure can be maintained. Putin has not unveiled a coherent plan for “eternal war,” but the Russian parliament has recently passed many laws that institutionalize the war; making it ever-present in day-to-day life.

Putin’s regime, the Russian economy and Russian society seem to be adjusting to a long-war basis, a permanent state of elevated, nationally orientated war-driven demand. Of course, this isn’t anyone’s idea of an ideal growth-regime. But then Russia was not in an ideal growth regime before the war either. And, with Russia’s strong balance of trade and considerable untapped fiscal resources, it is certainly sustainable.

Think tanks like the Higher School for Economics Institute for Social Policy are compiling scenarios for Russian society’s future development under the impact of the war. Their planning cooly estimates the probability of rising unemployment and losses of real income depending on how far sanctions are tightened. None of their scenarios predicts a collapse, though, in the worst case, poverty rates would rise and the middle class might shrink back to 1990s levels. Whatever weight one attaches to such studies, they show a. that intellectual life goes on and b. Russians are thinking through their long-term future.

The mood is one of contemplating scenarios and likely policy responses, not panic or emergency. Were the pressures on the Russian economy becoming visible in the summer of 2023 to further intensify, then as Tony Barber spells out in an excellent op-ed, Moscow has options:

Kremlin policymakers still have measures available to sustain the militarised economy. It would be possible, for example, to increase withdrawals from Russia’s National Welfare Fund, a kind of rainy-day reserve of liquid assets, including gold and Chinese renminbi. The authorities could also expand domestic bond issuance. Other options, which might address the problems of capital flight and a falling rouble, include the imposition of capital controls and a requirement for exporters to convert foreign exchange earnings into Russian currency. Last but not least, the government could increase taxes, or cut non-military state spending, or do both. The last two measures appear unattractive to the Kremlin, which has tried to maintain the illusion for citizens that life can go on more or less as usual despite the war. … In economic terms, however, the Kremlin wants to minimise or avoid steps that risk squeezing living standards and alienating the public ahead of next year’s presidential election. Although this will be a strictly organised political ritual rather than a genuine contest, the authorities still want to deliver an overwhelming victory for Putin. The higher the turnout, the more tightly ordinary Russians are locked in the regime’s embrace — so at least goes official thinking.

***

This increasingly long-term perspective in Moscow should be profoundly ominous for Russia’s opponents because it means that Moscow is now aiming to turn the war into the kind of war that least favors Ukraine – a long attritional struggle.

Moscow’s own timeline probably extends at least as far as January 2025. As Barber puts it:

Time is the all-important factor for the Kremlin. Its apparent calculation is that the Russian economy needs to hold out until the tides of political opinion turn in western countries, above all the US. Next year’s American elections are less than 15 months away, and Moscow is surely hoping they will produce a president and Congress less enthusiastic about paying for Ukraine’s war of self-defence. Remove or reduce US and allied military and budgetary support for Ukraine, and the prospects for its resistance to Russia’s aggression would indeed look bleak.

In war, the question of economics is always relative. However difficult Moscow’s position may be, that of Ukraine is far worse. As Barber concludes:

For Ukrainians, the present war is … a struggle for survival, as an independent state and as a nation with its separate, non-Russian identity. For Russians, the war is not remotely about national survival. One day it may be about the survival of Putin’s regime — but, judged from a purely economic point of view, that day is still some way off.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

August 28, 2023

The west has failed to keep its promises on aid

US and EU attempts to respond to China’s Belt and Road Initiative have fallen dismally short

Read the full article at The Financial Times

August 26, 2023

Chartbook 235: Who is driving Germany’s far-right poll surge?

Europe’s centrist political class is looking anxiously towards elections for the European Parliament in 2024. What they fear is a “lurch” to the far-right.

In Germany the AfD has surged to joint second place with Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s SPD in the polls. At 19 percent the AfD’s support is roughly twice what it was at the time of the last Bundestag election in September 2021.

Does this reflect a right-ward shift in German public opinion? Or, is a tactical reaction by German voters who are signaling their dissatisfaction with particular policies? If so, what is most on their minds.

An interesting poll by Instituts für Demoskopie Allensbach commissioned by the FAZ and summarized by Thomas Petersen gives some answers.

The short answer is that there is no evidence for a strong right-ward shift in German public opinion over the last few years.

To establish this fact Allensbach uses a general index of political alignment based on responses to prompts designed to identify (1) general conservative positions, such as „Are there are too many foreigners in Germany?”, (2) populist attitudes, such as “we live in a mock democracy”, and (3) more extreme attitudes including the use of violence to challenge “the system” and hostility to the “influence of Jews in world affairs”.

On this basis, 2 percent of the German population qualifies as belonging to the neo-Nazi spectrum (Rechtsradikal) and 12 percent have far-right and authoritarian views. At the other end of the spectrum there is 1 percent left-radical and 7 percent extreme left. None of these figures have changed significantly since the Allensbach team last conducted such a survey, in 2019.

It remains true that only 20 percent of Germans think the AfD is a “normal” democratic party versus 71 percent who have their doubts.

Only in East Germany has the share who are willing to normalize the AfD risen from 21 to 32 percent but there too, a solid majority regard the AfD as a danger to democracy. Indeed, since 2017 across Germany as a whole, the share of those who regard the AfD as a serious threat has risen.

So the underlying political attitudes of the German population do not appear to have lurched to the right and this cannot explain the current standing of the AfD in the polls.

Amongst who count as AfD supporters, people with neo-Nazi attitudes make up roughly 13 percent. Those with far-right authoritarian attitudes account for another 43, which means that 44 percent of those expressing support for the party do so without a general identification with far-right politics.

What motivates them to make such a political choice?

The Allensbach study allows us to dig into this question with some precision. Amongst the 44 percent of AfD supporters who do not generally hold a neo-Nazi or far-right worldview, 87 percent said they were very concerned about the flow of refugees to Germany.

That is 31 percentage points higher than for the population at large. 73 percent said they were concerned about violence and criminality. These concerns overshadow all other issues such as climate policy or the war in Ukraine, on which AfD takes distinctive positions.

You might wonder how someone who, on account of their xenophobia was willing too support the AfD, could not be counted as at least far-right in their political views. This is a reflection of the Allesnbach methodology which scores respondents on their responses to the 10 prompts. Only those giving 5 positive responses count as far-right and 7 as “rechtsradikal”. So if xenophobia, racism, Islamophobia are your thing, but you do not “otherwise” have right-wing preferences, you fall outside the Allensbach classification.

Another way of thinking about the distinction may be in terms of the purpose behind expressed political views. For about half the AfD’s potential electorate, their vote is a matter of conviction. But for on top of that for a large part of the AfD’s electorate their preference is a way of signaling – presumably to what they take to be the mainstream – that they are dissatisfied with the status quo and do not believe that their voices will otherwise be heard. When asked why they might consider voting for the AfD at the next election – as 22 percent of those in survey said they would do – 78 percent said that it would be a sign that they were unhappy with “current policies” with 71 mentioning migration policy, in particular.

As the Allenbach data identify, the urgency of this protest is itself distinctive of AfD voters. In response to the prompt, “I am firmly convinced that our society is inexorably headed towards a major crisis. With our current means we cannot address it. We can only manage if we fundamentally change our political system”, 62 percent of AfD supporters agreed v. 30 percent in the population at large.

En passant, the contrast between the Greens and the AfD on this question is remarkably stark. Only 11 percent of Greens, the lowest of all parties, believe in a systemic crisis that requires radical change. It confirms in dramatic fashion that the Greens are no longer a party of “fundi” eco-radicals, but have become the party of eco-modernity, the ultimate “staatstragende” (state-supporting) party of the Federal Republic.

Subscribed

Overall, the conclusion of the surveys seems quite clear. There has not been a general shift to the right. In addition to a base of far-right wing support, which makes up 15 percent of the population, the AfD is attracting a protest vote that takes it to slightly more than 20 percent support. This is driven by dissatisfaction with migration policy and a general fear of societal crisis.

What is striking is the conclusion drawn by Thomas Petersen and the FAZ editors from the Allensbach results, which I loosely translate as follows:

AfD supporters see Germany’s migration policy as a catastrophe. Until “Politik” (policy … mainstream policy AT) “gets a grip on this problem” and until it stops creating the impression “with citizens” that it treats anyone who is concerned about migration with condescension and moral superiority, the appeals of the AfD will continue to fall on fertile soil.

What is striking about this framing is that it accepts the AfD’s definition of a “problem” – their view that migration policy is catastrophic. It also accepts their populist terms for discussing it i.e. there are regular people – the participants in the survey – and it is up to “policy” (Politik) to respond to them. One might also simply say that in German democracy distinct constituencies are represented by different political parties with different views on what policy should be. In the resulting debate and policy process, which seeks to respond to a huge global problem of displacement, poverty and violence, they make choices that leave a minority of Germans dissatisfied. Half of the dissatisfied group (c. 10-15 percent of the overall electorate) are confirmed neo-Nazis and far-right authoritarians. The other chunk – less than 10 percent – are engaged in the politics of protest rather than responsibility, aligning themselves with a party in which neo-Nazis and the far-right is a powerful presence, presumably with a view to pushing the CDU further to the right. From a centrist point of view this is regrettable, but it is hard to see why this should be a cause for panic or any exaggerated concern about elitism. The real concern is presumably that substantial slices of the CDU are actually minded to join the far-right in this populist discourse. 29 percent of CDU supporters believe in an inexorable crisis that requires systemic change, the second highest after the AfD. In that regard the slippage in the conclusion of the FAZ piece – the FAZ being the conservative paper of record – from descriptive statistics to prescription is telling.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

August 25, 2023

Ones & Tooze: A Tale of Two Economies

Economic growth in Japan is surging while the U.K. continues its long slump. Adam and Cameron explain what’s driving the trends in each country.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

August 20, 2023

Chartbook 234: Whither China? Part III: Policy hubris and the end of infallibility

China’s economy is in trouble because its authoritarian demons are catching up with it and paralyzing the private sector.

China’s economy is in trouble because its growth model exhausted itself and entrenched power structures make it hard to shift gear.

The distinction between the “authoritarian impasse” and “structural Keynesian” interpretations of China’s economic situation is clear enough.

Both are very powerful explanations rooted in well-established social scientific models – institutional economics and Keynesian macro, respectively.

The “authoritarian impasse” model focuses on property rights and the supposed inevitability that at some point an authoritarian regime will succumb to the temptation to abuse them unleashing a downward spiral into a condition Posen compares to that of Russia, Turkey or Venezuela.

In Pettis’s model, based on macroeconomic flows – investment, consumption, government spending – what ultimately sets the limit on growth is the rate at which the economy can productively absorb new physical assets. When that limit is reached, the investment-driven growth model becomes dysfunctional. This too provides a powerful way of understanding China’s current impasse.

What both these strong models also have in common is that neither has a very precise account of the particular recessionary dynamics that China is currently suffering or why they emerged when they did.

Posen waives the real estate crisis aside to focus on the shock impact of the second round of zero COVID measures in 2022, which revealed the fragility of “no politics, no problem” standoff between the regime and the population. He doesn’t offer an account of why zero COVID should have been the moment when the true nature of the regime revealed itself to the Chinese population at large. But on Posen’s reading it was, in any case, only a matter of time. The result, as Pettis points out, is that in Posen’s narrative the slowdown has come abruptly.

Pettis, by contrast, has been bearish about the prospects for China’s growth for many years. The implosion in real estate confirms that pessimism in broad terms. But it also poses questions for the Pettis interpretation, because, contrary to the normally growth-fixated logic of Beijing’s policy – a fixation which is a key element in Pettis’s crisis model – China’s real estate crunch was induced, by the regime opting for stability over growth.

Whether we side with Posen or Pettis, we need a more particular policy narrative to explain how China and Xi’s regime have ended up in the particular impasse they face in the summer of 2023. The key theme of that narrative is not authoritarianism, or fixation on growth, but overconfidence and hubris.

***

Such a narrative might well start with COVID. But it would start not in 2022, but with the first wave in the spring of 2020, which in China, unlike in the rest of the world, was successfully contained.

The victory in the “People’s War” against COVID in the spring of 2020 triumphantly vindicated the improvised policy of zero Covid imposed in late January and February 2020. That comprehensive lockdown policy, of course, suited the particular proclivities and resources of the CCP regime. And it is worth remembering that at the time it seemed to many, not just in China’s leadership, that the emerging conditions of the anthropocene favored solutions that relied on rapid blanket action. Pandemic-reality appeared to have an “authoritarian bias”. The shambles of COVID policy in the West gifted Beijing a huge propaganda victory.

With its mandate from heaven confirmed, Xi’s regime turned bold. In May 2020 Xi’s regime pivoted to address three perceived threats to its undisputed and broadly popular rule – tech oligarchs, Hong Kong, and the giant housing bubble. All of these were issues of longer standing. In what appeared to be the aftermath of the COVID crisis, the summer of 2020 seemed like a good moment to tackle them.

If unfettered political power has an “original sin” problem – it cannot bind itself to behave responsibly and not threaten the conditions of long-term general prosperity – so too does unfettered capitalism. Predatory capitalists cannot credibly commit to behaving like reasonable competitors, even if that is for the good of the economy as a whole, or staying out of politics, even if a clear demarcation between law-making and the economy benefits long-run growth.

Whereas the West lives with the capricious power of Elon Musk, the CCP decided to show Jack Ma who is boss. What Beijing is not going to tolerate is robber baron capitalism – an oligarchy so extreme that some in the West have taken to calling our era one of neo-feudalism (More on that in a future newsletter. More a symptom than a diagnosis in my view).

Clearly, Beijing does not practice the rule of law in the manner of the EU competition authorities, for instance. The crackdown on big tech was a menacing intervention. But, in interpreting it, we should not start with a mom and pop, Jeffersonian model of competitive capitalism. What China’s regime has done is to aggressively reorganize an oligarchic political economy in a highly concentrated sector. That will no doubt cool spirits in China’s platform economy and act as a warning sign to other billionaires, but its long-run impact on overall growth is hard to gauge. It seems implausible to suggest that it will deter Chinese entrepreneurs from hungering after immense wealth and working creatively and furiously hard to attain it. The huge surge of innovation, investment and growth in renewable energy and EVs betokens as much.

The move against the Hong Kong opposition was driven by the prospect of an embarrassing outcome in upcoming elections. As far as its impact on the economy is concerned, the repression had at least the tacit acceptance of major business interests in Hong Kong. Many of those elites are clearly of the view that if opposition and free speech per se are not bad for business, regular clashes between opposition and regime surely are. The crackdown may be odious to liberals everywhere, but it is popular with the majority in the mainland including the Chinese staff of many Western firms that straddle Hong Kong and the mainland. The regime’s bigger project vis a vis Hong Kong is not to stop growth there, but, on the contrary, to bring it up to mainland standards and speed by integrating the city into a vast economic area in the South.

Finally, and most importantly in August 2020, with the Three Red Lines policy, came the decisive turn in housing and real estate. There is MUCH more to be said about this in a future installment in the newsletter series. The point here is simply to locate this turn in relation to the authoritarian impasse (Posen) and structural Keynesian (Pettis) views.

Posen dismisses real estate as nothing more than a sectoral crisis. This is unconvincing in his own terms. Real estate has not only been the biggest single growth-driver in the Chinese economy. If anything embodies the “no politics. no problem” growth bargain for modern Chinese it is property ownership. Owning property is what the Chinese dream promises. If as Posen suggests, the shock that matters is that to the Chinese population at large, not just to big business owners, then real estate is not any-old sector, but the crisis to focus on.

Were the Three Red Line interventions of August 2020 an example of unfettered sovereign power demonstrating the risks of original sin? Hardly. Every analyst around the world had been telling Beijing for years that something needed to be done to deflate the real estate boom. What Beijing is involved in is an exceptionally ambitious macroprudential intervention, trying to reduce systemic risk by allowing the managed collapse of certain over-extended private real estate developers.

The slogan under which Xi authorized the action was telling: “Homes are for living in. Not speculating with.” i.e. Xi claimed to be acting precisely to protect the right to a secure place to live, against the rampant commercialization of real estate. If broad-based incentives and participation in the economy are what you are interested in, then there is a good case to be made that “Homes are for living in” should be your slogan. The opposite logic can be seen at work in the demoralizing excesses of real estate hot spots such as Sydney, Seattle, Seoul, London or the Bay Area.

But what was also always clear, was that Beijing’s decision abruptly to deflate China’s giant housing economy was unprecedented. No other government had ever undertaken a similar preemptive move against a bubble of comparable scale – no one in the West before 2008, for instance. The policy was very risky. In the short-run it was going to inflict large losses on existing stakeholders some of whom were operating with considerable leverage. The fall out, even in the best case, would be protracted. That increased the chance of the property slowdown coinciding with other shocks. And that is what happened.

In 2021, though a slow-motion crisis was unfolding in real estate, China’s economy was doing better than most of the rest of the world. Life in much of China was untouched by COVID. Exports were booming. Compared to the West China’s trajectory through the crisis looked far superior. Then, disaster struck in the form of Omicron.

There is much to be said about the failure of Beijing to prepare adequately for Omicron, notably the failure to vaccinate adequately – an instance of the regime shrinking from coercion when it might have yielded benefits. The important points to make here are twofold:

First, it was the development of the virus over time that turned Zero Covid from a spectacular success in 2020 into an oppressive debacle two years later. It was the virus that mutated and not Xi’s regime. Secondly, the seriousness of the blow to the Chinese economy in 2022 resulted from the coincidence of the desperate effort to uphold zero COVID with the high-risk effort to deflate the real estate bubble.***

The current acute sense of crisis, which both Posen and Pettis claim as confirming their structural interpretation of China’s problems, in fact resulted not from deep authoritarianism so much as over-confidence and slowness to react to changing circumstances, and it resulted not so much from the relentless pursuit of growth as a bold decision to prioritize medium and long-term stability and security.

If Xi’s regime had not emerged so self-confident from the initial success of its COVID policy in early 2020, if it had deferred its high-risk plan to deflate the housing bubble until after COVD was brought under control around the world, if it had recognized the threat posed by Western COVID variants, vaccinated more comprehensively and prepared the health system, if it had been ready, on that basis, to soften zero COVID at an earlier date, China would not have faced the devastating confluence of recessionary tendencies that have dealt it such a blow in 2022 and 2023.

If you are committed to a structural interpretation, you could, of course, insist that Beijing’s propensity to make such misjudgments reflects the increasingly enclosed system of power around Xi, the lack of good advice etc. It is easy to imagine better policies with more perfect timing. But, if we say that it is authoritarianism that explains clumsy policy on the part of Beijing since 2020, what counterfactual are we invoking? How many governments around the world – democratic, populist or authoritarian – actually have much to be proud of in their COVID response? And consider the unprecedented scale of China’s growth boom since the late 1990s. In light of the track-record of economic policy-makers in Japan, Europe and the US, faced with much smaller real estate booms, why would we jump to the conclusion that China’s main problem is its authoritarianism?

This is not to say that the authoritarian tendencies of Xi’s regime are not oppressive and discouraging to private initiative. This is not to say that the lopsided investment-heavy growth model that China has hitherto pursued is sustainable. But China’s current crisis cannot be understood unless we also allow for the role of overconfidence, risk-taking and, possibly, miscalculation on the part of a regime facing an unprecedented array of challenges.

We do not yet know how the real estate crisis will work itself out. Beijing may yet manage the crisis – more on that in a future installment in this mini-series. But, in the mean time, one important novelty is simply that the CCP regime has lost the nimbus of infallibility that had emerged enhanced by the first phase of the COVID crisis.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Adam Tooze's Blog

- Adam Tooze's profile

- 767 followers