Adam Tooze's Blog, page 6

March 16, 2023

Ones & Tooze: The Non-Bailout Bailout

Adam and Cameron discuss what really caused Silicon Valley Bank to collapse and what other potential calamities to look for in the coming weeks and months.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

March 14, 2023

Chartbook #201 Venture dominance? The meaning of the SBV interventions.

At the weekend the Treasury, Fed, FDIC stepped in to stop developing bank run getting any worse.

Rob Armstrong at Unhedged has the list of the smaller banks that have been int eh crosshairs.

I am as much a sucker for a financial crisis-fighting story as anyone. But even I could not repress a horrible sense of deja vu and disgust at events over the weekend. Are the same people going to go on doing this over and over again: Tragedy, farce and then what? Zombie horror show? Of course the authorities should have seen it coming. If there are no resignations at the Fed, it will be a sign of the morbid state of the US governmental elite.

Was what the authorities in Washington organized a bailout? Not in the sense that the management at SVB, or the bank or the shareholders were saved. But Joe Weisenthal, Matt Klein and many othersm, rightly have little patience for that face-saving argument.

The crucial point is that an ecosystem of depositors was saved. And SVB’s depositors were in no regular sense, depositors. They are badly run and ill-advised businesses that for obscure reasons parked huge cash balances in a highly vulnerable bank. As Matt Klein remarks in his brilliant post at Overshoot the real problem at SVB was that its depositor was base was so “low quality” i.e. extremely prone to run with influence exerted by a small group of VC advisors. This was not so much classic large-scale bank in which mass psychology played its part on a grand scale, as a bitchy high-school playground in which the cool thing to do was to bank with SVB until it no longer was. As Klein puts it: “this was more a case of a “bank-run by idiots” rather than a “bank run by idiots”.”

It is those idiots that got bailed out. Why?

One could refer to the theory of financial dominance, which in the wake of 2008 argued that the Fed would ultimately face insuperable pressure from asset holders to step back from a high interest rate policy that inflicted losses on them.

But what happened over the weekend has a particular quality. On the face of it SVB is not a bank big enough to do systemic damage. That was the prima facie reason for exempting it from the oversight that extends to really big banks. Finance per se will not explain the emergency intervention.

But as should have been obvious all along SVB matters very much indeed, because its depositors are very powerful, very rich and very influential people who own a narrative that makes them indispensable to one vision of America’s future. And that force was brought to bear on the Biden administration over the weekend in an extraordinarily overt exercise of “venture dominance”

As Bloomberg reported:

SVB’s vast reach was laid bare to Joshua Frost, Treasury’s assistant secretary for financial markets, as he addressed a virtual audience of almost 1,000 venture capitalists and their portfolio companies on Friday evening. During a members-only Zoom call, representatives of the lobbying group National Venture Capital Association threw question after question at Frost, who would later that evening speak with FDIC officials. They implored him to consider the industry’s view when officials crafted a response. “The magnitude of what this industry is responsible for, and on behalf of the country, this is significant,” said NVCA president Bobby Franklin. “This is where the innovation happens.” The same day, some 20 private equity CFOs and executives with exposure to SVB jumped on a call. Some said that if it became clear deposits weren’t secure at smaller institutions like SVB, they would stop parking assets in them altogether, said a person briefed on the call.

The FT’s reporting on the same meetings exposes further piquant details:

Amid fears the government was prepared to let SVB and its uninsured depositors go to the wall, venture capitalists launched a concerted lobbying effort. They argued that it would not only have big economic repercussions, with companies struggling to write paycheques, but also that an outright failure would have geopolitical ramifications. “The theme was: ‘this is not a bank’,” said one person involved in the lobbying campaign. “This is the innovation economy. This is the US versus China. You can’t kill these innovative companies.” According to Brad Sherman, a Democratic congressman from California on the House financial services committee, the government became convinced that it had to take aggressive action to restore confidence after the failure of Signature. “One black swan is a black swan. Two black swans is a flock,” he said. “Once a second regional [bank] was shut down, this was systemic.”

This is what it looks like when the bourgeoisie in the true sense swings into action. It is what it looks like when an executive committee or committees constitute themselves and demand action from the state. It is highly reminscent of 2008 thought he specific sociology of Wall Street-Treasury relations in 2008 was rather different then from the Silicon Valley-Washington connection in 2023.

But as revealing as this is of underlying power relations should we be scandalized and lose ourselves in silly discussions about what is and what is not a “bailout”? Surely not. This is how financial capitalism operates. We know it.

As Yakov Feygin argues in a brilliant substack post.

The bailout is how modern capitalism deals with investment cycles through the state’s intervention. And in doing so, the state assigns losses to someone. That’s where the politics lie! This dynamic is especially vicious in the United States. As I like to tell my European counterparts, “America does social policy through investment and industrial policy.” This means that the US has a very weak welfare state but is not a small state. The American government is very good at stimulating investment and cleaning up the consequences of bubbles. At its best, this makes the American economy extremely innovative and productive and creates many highly paid jobs and employer-provided benefits. However, at its worst, it leads to lost decades and massive inequality…. the tools we developed to do so were constructed in ad-hoc ways in response to lots of crises and learning by doing. Thus, what we don’t know how to do as well is to apply these mechanisms in a way that is pre-planned and explicit in how it distributes the downside. This is where my friend Saule Omarova steps in! In her work with Robert Hockett and others, she has noted that the state is vital to the smooth functioning of the private banking system and its support for investment. So, she asks, why not make it official? Instead of an ad hoc bailout of real assets through a private financial system, which tends to be very indirect in its effect, why not have some public entities which can do the work directly? This is most explicit in work Saule, and I did together on a “bailout manager” whose job is to buy out the tangible assets of critical sectors facing bubble dynamics. However, this theme of recognizing the state’s enablement of private investment and, thus, the need to have an explicit policy for managing the bailout and fallout of financial capitalism runs through all her work. And this recognition of capitalism’s natural and normal functioning and how to make it more efficient apparently makes someone some raging Marxist…

Saule Omarova was the proposed candidate for OCC of the Biden administration who was red-baited in the Senate with a bipartisan coalition of credit unions and bank lobbyists blocking her progress.

I take Feygin’s proposal to be a diagnostic thought-experiment rather than a realistic proposal under America’s current political conditions. But it is indeed highly diagnostic and a useful political economy corrective to moralistic and legalistic arguments about the meaning of the current interventions.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters and receive the full Top Links emails several times per week, click here:

March 11, 2023

Chartbook #200 Something Broke! The Silicon Valley Bank Failure – How tech hubris and low interest rates combined to produce a big mess.

For a while we have been asking, as the Fed drives a global interest rate hike, what will bend and will break? The stress has been felt around the world. With Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse we now have a significant bank failure at the heart of a vital part of the US economy directly linked to the interest rate hike.

Silicon Valley Bank was not a small bank. It was the 16th largest in US financial system (and there are a LOT of banks in the US). Its collapse is the largest failure, by far, since 2008.

Source: WSJ

How did it happen? This by Noah Smith is really helpful, especially on the Silicon Valley side of the story, Peter Thiel etc

Why was there a run on Silicon Valley Bank?

The immediate cause of bank failures is almost always a run. No bank however solvent can withstand a full-scale run. SVB was a VERY VERY runnable bank.

To prevent bank runs, the US, like most countries, offers guarantees, by way of the FDIC, to depositors who have deposits of less than $250,000. They will be made whole whatever happens and so have no incentive to run, whatever the state of the bank. The average bank in the US has about 50 percent of its deposits insured in this way. JP Morgan and Bank of America have c. 30 percent covered.

h/t Gian Luca

At SVB at the end of 2022 only 2.7 percent of deposits were covered by FDIC insurance! As Noah Smith explains:

Why did SVB have so many uninsured deposits? Because most of its deposits were from startups. Startups don’t typically have a lot of revenue — they pay their employees and pay other bills out of the cash they raise by selling equity to VCs. And in the meantime, while they’re waiting to use that cash, they have to stick it somewhere. And many of them stuck it in accounts at Silicon Valley Bank. If you’re a startup founder, why would you stash your cash in a small, weird bank like SVB instead of a big safe bank like JP Morgan Chase, or in T-bills? This is actually the biggest mystery of this whole situation. Some companies put their money in SVB because they also borrowed money from SVB, and keeping their money in SVB was a condition of their loan! For others, it was a matter of convenience, since SVB also provided various financial services to the founders themselves.

So SVB was a big accident waiting to happen. What pushed it over the edge?

Did SVB make speculative loans? Yes, some. But not enough by itself to blow it up. Did it engage in adventurous financial engineering? No! A large part of its depositors’ money was invested in what is supposed to be the safest part of the financial system, Treasuries and government-backed bonds like agency-backed Mortgage Backed Securities.

SVB adopted this strategy precisely in the hope of always having the cash on hand it needed to meet any cash withdrawals from its large depositors. As the FT reported already in late February.

At the peak of the tech investing boom in 2021, customer deposits surged from $102bn to $189bn, leaving the bank awash in “excess liquidity”. At the time, the bank piled much of its customer deposits into long-dated mortgage-backed securities issued by US government agencies, effectively locking away half of its assets for the next decade in safe investments that earn, by today’s standards, little income. Becker said the “conservative” investments were part of a plan to shore up the bank’s balance sheet in case venture funding of start-ups went into freefall. “In 2021 we sat back and said valuations and the amount of money being raised is clearly at epic levels . . . so we looked at that and were more cautious.” That decision also created a “stone anchor” on SVB’s profitability, said Oppenheimer research analyst Christopher Kotowski, and it had left the bank vulnerable to changing interest rates.

A portfolio of government backed bonds will be something you can sell. The question is what price do you sell it at and will you suffer a loss? In 2021 interest rates were still low and bond prices were high. SVB’s bonds looked like a safe piggybank. Then came the great inflation scare of 2022. The Fed hiked rates, bonds suffered their worst year in history. Why? Because bond prices go down as prevailing interest rates go up. At a rough guess SVB suffered at least a $1bn loss on its books every time interest rates went up by 25 basis points and the Fed has hiked by 450. So if they had to sell their “safe” portfolio of bonds they would actually suffer a huge loss.

Of course, SVB were not the only ones in this position. And for that reason there is a big market in interest rate hedges. Did SVB have interest rate hedges? No it didn’t.

h/t Joseph Wang

It was not holding a safe piggybank. It was, in effect, taking a huge $100-billion-plus, one-way bet on interest rates.

As Matt Levine summarized it in a single brilliant paragraph, tech fed off low interest rates:

And so if you were the Bank of Startups, just like if you were the Bank of Crypto, it turned out that you had made a huge concentrated bet on interest rates. Your customers were flush with cash, so they gave you all that cash, but they didn’t need loans so you invested all that cash in longer-dated fixed-income securities, which lost value when rates went up. But also, when rates went up, your customers all got smoked, because it turned out that they were creatures of low interest rates, and in a higher-interest-rate environment they didn’t have money anymore. So they withdrew their deposits, so you had to sell those securities at a loss to pay them back. Now you have lost money and look financially shaky, so customers get spooked and withdraw more money, so you sell more securities, so you book more losses, oops oops oops.

Tech-finance is, no doubt, “special”. But is SVB the only financial institution sitting on large losses on its bond holdings? NO it isn’t. Chartbook noted this back in December:

The big bank bond losses

For years big US banks have been piling excess cash into bonds. Following the pandemic there was a 44 per cent surge in their bond holdings, to $5.5 trillion.

In 2022 the Fed began a tightening cycle and those bonds took a serious beating, inflicting HUGE paper losses on the bank holdings.

At the end of 2022, tthe FDIC cooly reported that

Unrealized Losses on Securities Increased: Unrealized losses on securities totaled $689.9 billion in the third quarter, up from $469.7 billion in the second quarter. Unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities totaled $368.5 billion in the third quarter, up from $241.8 billion in the second quarter. Unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities totaled $321.5 billion in the third quarter, up from $227.9 billion in the second quarter.

The distinction between HTM and AFS is all-important because as FT’s Lex explains

Banks can classify their security holdings as “held-to-maturity” (HTM) or “available-for-sale” (AFS). Those that are labelled HTM cannot be sold. But that means any changes in market value will not count in the formulas regulators use for calculating capital requirements. By contrast, any losses in the AFS basket have to be marked to market and deducted from the bank’s capital base.

The upshot. Even allowing for accounting help, there is a huge paper loss sitting on the balance sheet of America’s banks. Were there to be a liquidity squeeze, then a large part of the banks’ portfolios – the HTM part – could not easily be sold.

Lex finishes the year by warning:

For now, US banks remains awash in liquidity and are suffering no obvious financial stress. But rising deposit outflows and the increase in unrealised losses could become problematic if they need to sell investments to meet unexpected liquidity needs. Bond holdings could emerge as a serious pressure point for banks in volatile markets. Investors should watch out for this in 2023.

OK! … that was on December 27 2022. Two months later on 28 February the chair of the FDIC warned: “the combination of a high level of longer–term asset maturities and a moderate decline in total deposits underscores the risk that these unrealized losses could become actual losses should banks need to sell securities to meet liquidity needs.”

Guess where the outflows started in early 2023? The stressed tech sector! Since Q4 2021 VC activity has been declining in Silicon Valley and that was showing up in SVB’s balance sheet:

h/t Jack Farley

The panic began when SVB tried to raise capital to cover its losses. As Lulu Cheng explains this went terribly wrong.

SVB made the responsible decision to strengthen its financial position with a cap raise.

— Lulu Cheng Meservey (@lulumeservey) March 10, 2023

It made sense.

Where things went terribly wrong was the communication, specifically:

(1) WHAT they said, (2) WHO the audience was, (3) WHEN they did it, and (4) HOW they framed it.

Standing back, how could SVB have ended up in this exposed position? Why was it not stress-tested? Because in 2018 the regulations were changed and SVB was leading the charge pushing for the onerous regulations to be lifted.

https://t.co/sjuJI0IicI pic.twitter.com/sZBSxtU6Nw

— Josh Marshall (@joshtpm) March 10, 2023

The bank executive lobbying in this instance, is the same Greg Becker who “sold $3.6 million of company stock under a trading plan less than two weeks before the firm disclosed extensive losses that led to its failure. The sale of 12,451 shares on Feb. 27 was the first time in more than a year that Becker had sold shares in parent company SVB Financial Group, according to regulatory filings. He filed the plan that allowed him to sell the shares on Jan. 26.” As reported by Business Standard

What happens next? The FDIC will move quickly to wind the bank up. The politics will start around the 97.5% of the deposits that are not FDIC covered. Larry Summers and Andrew Yang are out there arguing for the FDIC to cover all the banks depositors. The impact on the Silicon Valley and Start Up Scene could be ugly. The damage may easily spread to the “private markets” which generate the billions in cash that sloshed into SVB’s accounts.

What is the risk of the damage spreading? A lot will be written about the rest of the. US banking system in coming days, so let me pivot instead to the rest of the world, where Brad Setser offers a typically superb overview:

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank highlighted the risks posed by "underwater" long duration bonds — particularly when those bonds funded with short-term liabilities.

— Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) March 10, 2023

Who else in the global economy holds a lot of underwater bonds?

Asian insurers and policy banks …

1/ pic.twitter.com/Y3FViq39G8

****

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters and receive the full Top Links emails several times per week, click here:

March 9, 2023

Ones & Tooze: The ESG Backlash

Environmentally conscious investing has been a thing for at least two decades now, with many corporations around the world embracing it. But the backlash is now a thing as well, driven largely by anti-woke activists and lawmakers. On the show this week, Adam and Cameron explain the mechanics of ESG—environmental, social and governance investing—and break down the arguments for and against.

Also on the show: The economics of divorce.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

February 24, 2023

The west’s limited support for Ukraine fails to measure up

Europe and the US may sincerely want Kyiv to prevail over Moscow but they are failing to match ends with means.

Read the full article at Financial Times

Ones & Tooze: The Miracle of Poland

Poland has had an incredible economic rise since the collapse of communism, even as its government has become increasingly illiberal. Are the two things connected? Or contradictory? Adam and Cameron dig in.

Also on the episode: The economics of marriage.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

February 19, 2023

Chartbook #196 The Closing of the Cocoa Frontier

This Valentines day, Americans gifted each other in the order of 58 million pounds of chocolate, much of it wrapped in 36 million heart-shaped boxes. It was a particularly busy period for the global chocolate industry, which in 2020 processed c. 5 million tons of cocoa beans into chocolate confectionary, generating around 130 billion dollars in revenue. The cocoa-chocolate business is an agro-industrial complex that has emerged from millennia of human ingenuity and entrepreneurship mixed with commerce, political power and violence. At the front end are well known chocolate brands, the likes of Cadbury, Mars, Lindt and so on. Behind them are the grinder-traders, giant agro-industrial trading corporations like Cargill. There would be no chocolate, however, without the cocoa beans and they are grown overwhelmingly on small peasant plantations, most no larger than 3 hectares, yielding 300-400 kg in beans per hectare and worked by c. 6 million farming families. Together with their families, perhaps 50 million people are directly involved in cocoa cultivation and processing, including many youths and children. A rough calculation suggests that the cocoa-farming dependent population worldwide outnumbers the entire farming population of the United States and Europe. At 14 million the main workforce on the cocoa farms significantly outnumbers the 9 million workers engaged in motor vehicle production worldwide.

Recently, Indonesia has emerged as a major grower. Both Central and South America, the original home of the cocoa bean, still contribute to global supplies. But 70 percent of the world’s cocoa beans come from West Africa and 60 percent from the farms of just two states, Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire (CdI). In a year of good harvests, CdI with a yield of well over 2 million tons of beans, can account for 40 percent of the global production. De facto the global pyramid of chocolate confectionary balances on the peasant producers of Ghana and CdI who have been the drivers of a production revolution of huge scale.

***

What first catches the eye about this supply chain are the spectacular hierarchies of power. For journalistic purposes and in NGO campaigns, these hierarchies are commonly dramatized in two clichés. The first is the contrast between the tiny peasant producer and the agro-industrial multinationals. The second is that between Western consumers of chocolate and child labourers in the cocoa plantations.

One piece of recent research by Staritz, Tröstere, Grumiller and Maile maps the global supply chain as follows:

Along the top row you have the futures price for cocoa as determined by the interplay between financial investors, chocolate manufacturers and grinder-traders on markets in New York and London. The futures price determines the price at which cocoa beans are exported by the parastatal marketing boards of CDI and Ghana. They seek to maximize revenue in a market where they are subject to quality controls, and the constraints of limited financing and volatile exchange rates. CdI’s Conseil du Café-Cacoa and Ghana’s Cocoa Marketing Company oversee the buying or directly manage the purchase of beans from local intermediaries who deal directly with the cocoa farmers. The farm-gate price of the beans is set as a fraction of the export price under the supervision of bodies like the Producer Price Review Committee.

The net result of this price-setting mechanism, is that of the final value of the chocolate bar sold to consumers, the peasant producers garner around 5-6 percent. In recent years, unsurprisingly, given this gross imbalance cocoa farmers have struggled to make ends meet. It was recently estimated that more than half of Ivorian cocoa farmers and their families subsist on less than $1.20 a day. It is a set of relations that gives supply-chain, a rather different connotation.

Nevertheless, even in the face of falling incomes, farmers continue to cultivate their plantations. Maintaining the family comes first. Their land is valuable, but the prospect of selling up and moving to the overcrowded cities or trying other, no-less precarious lines of work, is daunting. So they hang on, in the hope of better times to come. And in the mean time everyone in the family must chip in.

Assessing the scale of child labour on cocoa plantations is a difficult business. But perhaps as many as 1.5 million children and young people are involved in one way or another in cocoa farming. A small minority, the most unfortunate, are trafficked and work in conditions akin to indentured labour. A larger group of children end up as casual migrant laborers on cocoa farms. But aside from these two groups, the overwhelmingly majority of children working in the cocoa plantations are family members helping their parents to sustain marginal family farms.

With regard to household labour, modern-day cocoa farming is typical of peasant farming in general and of household economies across the poor world. In the unregulated and unlicensed informal sector – the main form of employment in much of the developing world – the line between work and household economies is fluid and school attendance for children is haphazard. What is unusual about the case of cocoa is that such informal household economies are directly harnessed to global supply chains that deliver every day items of indulgence to consumers in the rich world. Furthermore, rather than peasant production of cocoa being a shrinking or residual system beating a retreat from the historic stage, the last century and a half has seen a huge surge in the scale of production without which the global growth in chocolate consumption would have been impossible.

***

Cocoa is not native to Africa. The beans were introduced from latin America in the course of the 19th century by European colonialists. But the widespread adoption and cultivation was from the outset the work of African peasants, notably on what the British then called the Gold Coast. Since cocoa, whether in the form of a beverage or chocolate, has never been a part of the West African diet, cocoa bean cultivation is a commercial, market-orientated operation. The beans are grown for one reason and for one reason only: to sell them for cash. And the entrepreneurialism of West Africa’s farmers has been astonishing. As Gareth Austin writes in the Economic History Review

Ghana exported no cocoa beans in 1892, yet 19 years later, at 40,000 tonnes year, it became the world’s largest exporter of the commodity. Output reached 200,000 in 1923, and passed 300,000 in 1936.

By 1950 Ghana entirely dominated the world market, having increased the global supply tenfold. As Órla Ryan records in her excellent book Chocolate Nations:

one British colonial official described the Ghanaian cocoa boom as ‘spontaneous and irresistible, almost unregulated’. In a government report in 1938, he wrote: We found in the Gold Coast an agricultural industry that perhaps has no parallel in the world. Within about forty years, cocoa farming has developed from nothing until it now … provides two fifths of the world’s requirements. Yet the industry began and remains in the hands of small, independent native farmers.

Following Ghana, the explosion of production in Cote d’Ivoire was even more dramatic. After being held back in the colonial period by French policy, in the sixty years since independence in 1960, CdI has unleashed a spectacular boom. Today, the peasants of CdI deliver at least forty times more cocoa beans to the global market than were harvested worldwide in 1900.

As impressive as it is, the African revolution in cocoa cultivation has ambiguous implications for the growers themselves. The production surge is crucial to understanding the power imbalances between corporations and peasants, consumers and child laborers. The situation is as unbalanced as it is, because the relentless peasant entrepreneurialism of Africa’s small producers, combined with the push of population growth and the availability of land, has made the supply curve highly elastic. Even with a voracious global appetite for chocolate, given the speed with which production has been been expanded, the trend in cocoa bean prices has generally been against the producers.

Source: Gilbert, 2016.

If this were a story of falling prices driven by productivity increases, in other words a story of intensive growth, it would be grounds for celebration. Everyone would be a winner. The fundamental problem is that cocoa farming in Africa over the last 130 years has been a dramatic example of extensive not intensive growth. It has been highly dynamic in terms of output but achieves that dynamism through mobilizing more resources, typically of labour or land.

Across West Africa, the moving frontier of cocoa cultivation was a land grab akin to those which drove agrarian growth across South America, or, for instance, in Manchuria in East Asia. In this case the settlers were African peasants and the land they was incorporated into production were the West African forests. The great French historian and analyst of cocoa François Ruf speaks of the “forest rent” harvested by the cocoa farmers. Ruf sees the history of cocoa as driven by a series of “pioneer fronts” that have extended around the world from South America to Indonesia and West Africa. As William Gervase Clarence-Smith and Ruf explain in their introduction to the edited collection Cocoa Pioneer Fronts:

A forest rent exists because it is rarely economically viable to replace decrepit cocoa trees by new ones in the same land, or to plant cocoa in land used previously for other crops, as long as forest is available. Planters clearing poorly regenerated secondary forest and former coffee groves to grow cocoa in eastern Madagascar found that they could not compete on the world market (Chapter 11 ). Producers clearing primary forest, in contrast, benefited from the fertility of virgin soils and low concentrations of weeds, pests and diseases. There have been a few examples of permanent cocoa cultivation in the same land, but they have usually depended on excessively expensive inputs of labour and capital. It is also possible to leave land fallow for very long periods before replanting cocoa, but forest regenerates slowly and incompletely, and it is normally more economical to use the land for other crops. Permanent techniques of cocoa cultivation are therefore likely to remain marginal until there is no more primary forest available in the world, either because it has all been cut down, or because it has at last been effectively protected (Ruf, 1991, 1995).

Apart from land, labour is of course vital to cocoa production. In the 19th century in Brazil and in Portugues São Tomé, slave labour was employed. As recently as 1900 São Tomé was still the largest producer. But in the 20th century forced labour and even large-scale plantations have failed to compete up with the energetic expansion of small-scale, family based peasant cultivation.

If the cocoa story is one of land-grabbing, this inevitably raises the question of competition for resources and the question of politics. Within Ghana, the main producer of the early 20th century, conflict was relatively successfully contained by a strong system of property rights. In CdI production was expanded in a helter-skelter fashion through mass in-migration to the cocoa territories. Not for nothing CdI, which saw the most dramatic surge in cocoa production in the late 20th century, would, in the early 21st century, become the arena for violent struggles over citizenship rights and control of land.

This brings us to the question of the post-colonial state. Alongside fundamental material factors such as the availability of land and the mobilization of labour, alongside the global balance of demand and supply, the chocolate industry has been shaped in fundamental ways by the political economy of African states. The cocoa supply-chain as we know it today encodes the history of policy choices by post-colonial regimes in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, a history in which fundamental questions about economic sovereignty and freedom were posed and answered largely in the negative.

***

Ghana was not just the premier cocoa producer of the world between 1900 and 1965. Not coincidentally, in 1957 it was also the first African state to gain independence. In Kwame Nkrumah it had the most charismatic leader of the early independence moment. Nkrumah insisted that Africa needed to achieve not just formal independence but also a qualitative leap in economic development. For Nkrumah this meant infrastructure and industrial development. Most spectacularly the newly independent Ghana would invest in hydropower and aluminium smelting, a project realized in the form of Volta Aluminium, a highly unequal partnership with America’s Kaiser corporation.

In Nkrumah’s vision, the springboard for Ghana’s leap towards industrial modernity would be the West’s addiction to cheap chocolate bars and Ghana’s cocoa beans. Nkrumah and his advisors resolved that it would be taxes on the cocoa farmers that would provide Ghana with the funds it needed to drive investment. It was a classic vision of development as first explicitly theorized in the Soviet Union in the 1920s. If Ghana’s first development plan after independence was drafted by Western-orientated economists, the second, finalized in 1962, relied heavily on Eastern European expertise. Not that Accra envisioned a collectivization of the Ghanian peasantry, or even villagization, as was later to happen in Tanzania. Instead, the newly independent Ghana focused on raising taxes on the cocoa-growing peasantry to feed industrialization.

As Órla Ryan reports in her book Chocolate Nations, according to the Ghanian Cocoa Marketing Board

In 1956/57, the average sale price of cocoa was £189 per tonne; the government took £40, leaving the farmer with £149. By 1964/65, the average sale price was £171; the government took £59, leaving the farmer with £112.

These high tax rates were a heavy burden on peasant cocoa production and they were bearable only so long as world-market prices remained high. In 1965 despite vain efforts to Accra to resist the trend, world market prices collapsed. The wheels were coming off Nkrumah’s development vision. In February 1966 whilst he was in Beijing, on one of his many foreign trips, Nkrumah was ousted by a coup.

Nkruhma’s fall from power was extremely popular at the time, but it ushered in a period of both political and economic uncertainty for Ghana. Though global cocoa prices recovered and then surged in the early 1970s, Ghana failed to take advantage because of domestic political chaos and punitive tax rates on cocoa exporters. In Ghana the implicit taxation on cocoa farmers increased from 20 per cent in 1960 to more than 80 per cent around 1980. Even more ruinous was the absurdly overvalued exchange rate which robbed Ghana’s farmers of any incentive to export their cocoa beans. The cocoa harvest collapsed by two thirds. Ghana was overwhelmed by foreign debts and reduced to trading cocoa beans for East German chemicals and Cuban sugar. In 1983 GDP per capita was 25 percent below its level at independence. Government revenue as a share of GDP, a basic measure of state-capacity, shrank from 17.3 percent in 1972 to 6.1 percent a decade later. The share of industry in Ghana’s employment fell from 14 to 12 percent. The effort to build a development strategy on cocoa had comprehensively failed.

Nkrumah and his supporters will to this day attribute the failure to the force of neo-colonial structures in the world economy. A more subtle critique from the left points to the malign and self-serving influence of bureaucratic elites within the post-colonial state that Nkrumah created to bring his vision of industrialization into effect. But as Cambridge economic historian Gareth Austin has pointed out (in a seminar at Edinburgh in 2018), we also need to avoid anachronistic retrospect. A strategy of labour-intensive industrialization may appear very attractive in the 21st century. Today Ghana like the rest of West Africa is struggling to cope with a population explosion. It desperately needs jobs. It seems implausible that the tertiary sector (services) alone can fill the gap. This confers on Nkrumah in retrospect the appearance of a prophet. But it is more than questionable whether Nkrumah’s proposed strategy made sense for Ghana in the 1950s.

The defining feature of Ghana’s economy in the 1950s, like that of the rest of Africa, was labour scarcity and land abundance. Hardly the ideal conditions to develop comparative advantage in low-wage manufacturing. It would likely have made more sense to focus development on basic infrastructure, health and education rather than attempting to leap to the “next stage” of industrialization. Nor is this an anachronistic retrospect. The analyst who argued against forced-pace industrialization at the time was none other than Nobel-prize winning Caribbean development economist Arthur Lewis, first in his report on the Ghanian economy in 1954 and then as economic advisor to Nkrumah between 1957 and 1958. After barely more than a year Lewis would resign from his post, accusing Nkrumah not only of padding his investment projects with political white elephants but also of authoritarian tendencies that Lewis in private declared to be “fascist”.

***

The alternative to milking the cocoa farmers to pay for industrialization was to base economic growth on their entrepreneurial energies. This meant perpetuating the existing division of labour and seeking to grow out of it by taking maximum advantage of the opportunities on offer. This was the approach adopted by Cote d’Ivoire after independence in 1960.

It is true that growth in CdI was, in a sense, waiting to happen. Under the French, peasant-based cocoa production had been stifled by colonial forced labour regimes and the French preference for cotton and rice production. The forest rent in CdI’s sparsely populated Southern and Western regions was waiting to be harvested. But, the pace at which farmers in CdI took advantage of these structural conditions was accelerated by policy and a general approach of laissez-faire.

After independence, CdI’s leader Felix Houphouet-Boigny, himself a prosperous farmer, adopted a policy that rejected both the colonial past and Nkrumah’s policy of industrialization in neighboring Ghana. As Órla Ryan explains in her excellent book Chocolate Nations, Houphouet-Boigny’s slogan was ‘the land belongs. to those who make it bear”. He liked to refer to himself as the nation’s “First Peasant”. CdI’s encouraged a free for all of migration to the cocoa and coffee-growing areas. Many of the migrants were from the Baoule, Houphouet-Boigny’s own ethnic group. Other cocoa pioneers came from the North of the CdI, and hundreds of thousands more came from Burkina Faso and Mali. The result was the second African cocoa revolution.

The result was spectacular economic growth. With enthusiastic backing from Paris, CdI was the anchor of the francophone African region. By 1986 CdI’s GDP per capita was rated at twice the African average. The result was a spectacular in-migration of people from around the French-speaking world. In the late 1980s, 190,000 Lebanese resided in CdI – mainly Shiite Lebanese fleeing the civil war. After independence, the population of French residents in CdI actually increased to over 40,000. In the late 1980s the ex pat constituency was so numerous and affluent that French politicians took to campaigning in Abidjan both for votes and financial backing.

On CdI’s cocoa frontier, the reshuffling of population was even more intense. In the South-west of Cote d’lvoire by the late 1980s, the native Kru and Bakwe were outnumbered to such an extent that they accounted for just 7.5 per cent of a population that had swollen by a factor of ten in a matter of a few decades. Baule migrants made up 35.7 per cent of the population. Burkinabe from neighboring Burkina Faso accounted for 34.4 per cent of the population. They were granted the right to vote and formed a captive electorate for the President.

The cocoa gold rush in CdI went well so long as the pro-migration political regime remained in place, cocoa prices stayed high and there was enough good land and other opportunities to go around. On the cocoa frontier, any conflicts were mitigated by the fact that locals could make a handsome return by selling their land to new-incomers giving them the means to start a new life in the booming towns and cities.

The Ivorian model was tested in the 1980s by a sharp fall in cocoa prices. Houphouet-Boigny’s regime responded by borrowing billions from foreign lenders and doubling down, diversifying into a variety of other agricultural sectors, including rubber. Then, in the late 1980s, the CdI’s African economic miracle came apart. As Jean-Pierre Chauveau and Eric Léonard describe the shock in the contribution to the Cocoa Pioneer Fronts:

Between 1988 and 1992, the effective farm gate price of cocoa fell to nearly a third of former levels. In 1988, and again in 1993, cocoa growers were not even able to sell their crop. All in all, farmers faced a reduction of 60 to 80 per cent in their monetary income

In an effort to resist falling prices, CdI boycotted global buyers, but that effort failed. In 1989, taking the advice of the IMF and the World Bank, Abidjan cut by half the payments to coffee and cocoa farmers. With the urban economy in free fall as well, the drift of the Ivorian population was back to the land. As one interviewee told, Órla Ryan, ‘Suddenly cocoa prices drop through the floor and the economy is not growing. Everyone wants to go back to the land. The problem is who owns it.’ Into this fraught situation, CdI embarked on its first openly contested democratic election. Capitalizing on the growing struggle for land, Laurent Gbagbo challenged Houphouet-Boigny accusing him of favoring foreign newcomers. Houphouet-Boigny won the election decisively, but the genie of xenophobia and ethnic sectarianism was well and truly out of the bottle.

Inter-communal pressure was compounded by ongoing economic crisis. In the course of the 1990s the more highly productive Baule plantations were increasingly displaced on the cocoa frontier by Burkinabe farms who relied on a subsistence model of family economy to weather the economics crisis. Whilst output plateaued, Cote D’ivoire, once the acme of stability in Francophone Africa, and the anchor for the region descended into inter-ethnic and regional strife. Twice, between 2002 and 2007 and then again in 2011 CdI was racked by civil war. Cocoa harvesting continued. No one could afford to see the harvest fail. But the period of CdI’s economic miracle was over.

***

After the bankruptcy of both the Ghanian industrialization model and CdI’s free-wheeling agrarian model of development, both were in search of new models of development. And in the 1990s it was Ghana that showed the way forward.

From the 1980s onwards under the more pro-peasant regime of Jerry Rawlings, production and investment recovered. Production was a fraction of Cote d’Ivoires but it tripled by the early 2000s to 600,000 for the first time surpassing the records set in in 1965. Crucially, Ghana resisted World Bank and IMF pressure to fully liberalize its price-setting system. The Cocoa Board shed the vast majority of its bloated staff but it continued to offer Ghanian farmers a fixed price for every harvest based on a fraction of what the Board was able to obtain in selling the cocoa beans for export. The fraction left with the farmers was far more generous than had been the case by the low point of the 1980s and since 1992 Ghana’s increasingly vibrant multi-party democracy ensured that it has stayed that way. No elected politician could afford to ignore the cocoa-farming interest.

CdI by contrast was by the late 1990s in such dire straits that it could not resist the IMF and World Bank’s pressure for full liberalization. By the early 2000s, Ivorian peasant producers would receive not a guaranteed price but whatever they could negotiate with commercial buyers. What would emerge from that haggling would depend on market conditions and the specific circumstances of buyer and seller. But what the peasants would no longer have to deal with was the bureaucracy of the indebted and rapacious state. The state for its part would be made able to function without exorbitant cocoa tax revenue by being put through a process of debt relief.

This at least was the theory. It did not work like that in practice. Instead, the stabilization board was abolished but Ivorian politicians set up five separate institutions, notionally to support the farming population, but each separately imposing levies that on net left the cocoa farmers with nor more than 35 and 40 percent of the export proceeds.

The model could survive in the 2000s because the trend in prices was positive and global demand was surging. New markets for chocolate were opening up in the emerging markets and particularly in Eastern Europe. But following the swithback of 2008-9, cocoa interests in the CdI had had enough of the liberalized model. In 2011, following the end of the second round of civil war, and a major scandal involving corrupt cocoa administrators, CdI reverted to a system of price fixing with the Conseil du Café-Cacoa setting an annual price that was revised during the course of the harvest. The CCC operates a scale called the “barème”, which defines prices and margins for farmers, traders and exporters on the basis of prices paid for export permits. The policy goal is to ensure that the minimum producer price for farmers is 60% and not below 50 percent of the world CIF reference price for Ivorian cocoa beans.

Since the early 2000s for all the institutional differences, there has been a strong convergence between both the model of pricing and the results earned by farmers in the Ghanian and Ivorian systems.

Meanwhile, in recent decades Ghana and CdI face ever more concentrated power on the side of the exporting firms. As Staritz et al report:

In Ghana, the number of cocoa bean trading partners decreased from about 100 in 2000 to 11 in 2013 (van Huellen 2015). In Côte d’Ivoire, grinder-traders own the top five exporters—Cargill, SUCDEN, Touton, Olam and Barry Callebaut—and bought 80% of the export contracts during the 2018–2019 season (Aboa 2019), which is the same share that the top 10 bought in 2010–2011 (Araujo Bonjean and Brun 2016). Grinder-traders not only have dominant positions as buyers, but they also are involved in internal marketing, particularly in Côte d’Ivoire, where they also act as exporters in external marketing.

The global cocoa industry has thus reached a new concentrated organizational form, with the cocoa controls agencies of Ghana and CdI, facing off with a compact group of exporters. It is a highly unstable balance. Following the sudden slump in world prices in 2016-7, CdI and Ghana entered into high-level talks and in March 2018 signed the Abidjan Declaration. They agreed to adopt a common strategy to drive up producer prices. In June 2019 they set a common floor price for the 2020-21 season of 2,600 per ton of which farmers were to receive 70%, or USD 1,820 per ton. In the face of buyer resistance the CdI and Ghana backed down to agree instead that prices would be set as normal, but buyers would pay a premium of $400 per ton to support farm incomes and in the event that this did not yield at least $1820 per ton for the farmer, the price setting agencies in CdI and Ghana would cover the gap. In effect they declared a minimum price guarantee. It was a substantial risk for the buying agencies and one that was immediately exposed by the COVID crisis. Faced with tumbling world prices, in mid year 2021 the Ivorian CCC slashed the price for CdI farmers to $1350 per ton. Meanwhile the global buyers, having agreed pro forma to the $400 per ton levy in favor of the farmers, have now taken to cutting the country premiums they previously paid to Ghana and CdI.

***

Ghana’s room for maneuver has been narrowed by the financial crisis that has forced it to seek debt restructuring from its creditors. It is possible that by expanding the cocoa cartel to Nigeria and Cameroon the producers can gain more leverage. But there are more fundamental factors that might shift the balance and disrupt the market. One influence may come from the side of demand. If chocolate consumption takes off either in India and China, as the chocolate firms hope, the demand for beans could be gigantic. CdI’s President Ouattara has recently been wooing Chinese investment in the cocoa sector. The impact on the market would be all the more spectacular because the frontier expansion of cocoa growing in West Africa has reached its limit. There is no more forest in Cote D’Ivoire to clear. The forest rent has been exhausted.

The stiffening of the conditions for extensive growth could betoken a shift in favor of the producers, creating the conditions for a strategy of intensification, as recommended, for instance by the World Bank.

The first approach would be to launch a “technological revolution” that would enable producers to increase their yields. Such a revolution is not just a pipe dream, as the techniques, such as shading, grafting, and irrigation, have all already been mastered by the Center for Agricultural Research in Côte d’Ivoire, and their application has already quadrupled yields (from 500 kg to 2,000 kg per hectare) on pilot farms. The challenge now is to scale up the use of such techniques

More worryingly reaching the limits of the forest frontier may signal the beginning of a more comprehensive crisis of the ecological conditions of cocoa farming, which would compound the limits to growth with the effects of increasingly severe cocoa blight and climate change. The crop is planted where it is, because of the sensitivity of the trees to precise climactic conditions. Currently, cocoa can only be grown 10-20 degrees either side of the equator. But those conditions are changing. The predicted two percent change in temperature over coming decades will fundamentally challenge the existing production regime. The cocoa frontier may be closing, but there is no end to chocolate’s turbulent history in sight.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

February 17, 2023

Ones & Tooze: Move Over Elon Musk

As Elon Musk’s fortune dwindles to a mere $190 billion, a new oligarch has been crowned the richest person in the world: Bernard Arnault of France. On the episode this week, Cameron and Adam discuss how Arnault made his money and what his empire tells us about his home country.

Also on the show: the economics of chocolate.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

February 10, 2023

Ones & Tooze: The Economics of Dating Apps

This week’s episode happens to overlap with Valentine’s Day, so we thought we’d use that as an opportunity to start a new series on the economics of love. For the next several weeks, we’re going to be spending part of every show talking about romantic relationships from an economic perspective.

We thought we’d start this week with the place that most romantic relationships tend to start, and that is with dating, specifically with dating apps. And the data point there is 39 39%. That is the share of all heterosexual couples who now report having met their partner online. That makes online including dating apps the most popular single method of meeting a romantic partner more popular than all the traditional avenues, whether through family friends at a bar, their work, church in the neighborhood, etc..

And actually, that means heterosexual couples are only now catching up to same sex couples. 65% of same sex couples say they met their partner online. So they have been ahead of the curve. All this adds up to dating apps, being in the center of our national romantic life. So we thought we’d dig in…

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy.

February 8, 2023

Chartbook #195: How to pay for Putin’s war? Russia’s technocrats torn between defense of the austerity status quo and national mobilization.

It is clear that the Russian economy emerged from the first shock of the war and sanctions in 2022 far better than many expected. The official data show a fall in 2022 of just over 2 percent and a prediction for at least some economic growth in 2023, no worse than that expected for Germany and better than the outlook for Britain.

Gdp contracted by just 2.2% last year, smashing many economists’ expectations, made in the spring, of an annual decline worth 10% or more. Uncomfortable, perhaps, but nowhere near enough to cripple Vladimir Putin’s war effort. Unemployment remains low, even if many people are being paid less. House prices have stopped rising, but there is no sign of a crash. Consumer spending is dragging on the economy, but not by much. In 2023 the imf even predicts that Russia will grow by 0.3%—a superior performance than Britain and Germany, and only marginally worse than the eu.

Putin’s reaction was to crow that the experts were wrong. As the FT reported:

“The real dynamics turned out to be better than many expert forecasts,” said Putin. “Remember, some of our experts here in the country — I’m not even talking about western experts — thought [gross domestic product] would fall by 10, 15, even 20 per cent.”

Some of the more fascinating coverage in the West takes the opposite view. Far from taunting his technocratic advisers, Putin should be thanking them for seeing Russia through the first year of his ruinous war.

It is clear from inside reports that many leading experts warned Putin against his military adventure. Some objected more or less publicly. A few resigned. Others, such as Elvira Nabiullina at the central bank, tried to bow out of public service, but were effectively ordered to stay put. The majority have worked on, whether out of fear, or a sense of duty towards their embattled country.

This narrative makes for a high-stakes moral drama. As one former central-bank official told the Economist

he was both impressed and appalled by his colleagues’ efforts to keep the war machine afloat. “They understood what they were doing, even while they comforted themselves by pretending the people who would replace them would be worse.” One high-level source close to the Kremlin says, “The elite are prisoners. They are clinging on. When you are there for that long, the seat is all you have.”

But as compelling as this is, viewing the issue in terms of morality can distract us from the underlying issues of economic management.

It makes sense to see the professional management of the central bank as key to stabilizing the financial situation in March and thus averting a financial crisis or a spectacular ruble crisis. On this score the essay by Oleg Itskhoki offers an excellent summary. Essentially, the financial system was placed under direct control and then Moscow waited for the shock to wear off and the proceeds of the oil and gas boom to roll in.

It was coolly done and it is reminiscent of the way in which Russia also road out the shock of the 2014 sanctions post Crimea for which Nabiullina was awarded not one but two prizes by her fellow central bankers.

But, as several of us argued back in March 2022, the track record of stability clocked up by Putin’s regime, the overcoming, again and again, of the trauma of 1998, comes at a heavy price in terms of macroeconomic imbalance. Nicholas Birman Trickett has been particularly forceful in arguing that since 2014 Russia has run a regime of ruinous macroeconomic austerity that contributed to trade surpluses that rival those of famously unbalanced economies like Germany and China. In their case huge trade surpluses in manufactured goods are the symptom of imbalance, in the Russian case it is the energy sector that becomes the fulcrum of a completely unbalanced political economy. What was squeezed, as a result, was investment in the development of new sectors of the economy. It is not just structural constraints, bad institutions or insecure property rights that inhibited Russian growth, but lack of aggregate demand, which validates and justifies investment.

To this extent the technocrats personified by Nabliuova are not really a counterweight to Putin’s authoritarian rule. They may be a source of financial stability. They may vainly seek to restrain his more aggressive impulses. But the objective consequence of their policies is to reinforce the constraints that increasingly define the parameters of Putin’s rule. Caught in an austerity straight jacket of their devising, Putin’s regime has backed itself into a socio-economic impasse that encouraged zero-sum rent seeking rather than growth. On this interaction I highly recommend the essay “Empire of Austerity” by Trickett.

For the defenders of the austerity consensus in Moscow, the war is objectionable not just on moral grounds, or grounds of grand strategy. They object because they correctly sense that it puts their entire edifice of financial constraint in question. Most recently, there are reports of tensions between the central bank and the Ministries of Putin’s government. These are only to be expected when a conservative central banker confronts a government that wants to move the society and economy on to a mobilization footing. Russia’s deficits are by no means gigantic by western standards, but they are rising abruptly.

In a war economic situation, different rules do apply. Though the central bank played a key role in containing the financial crisis, if you ask why Russian GDP has been relatively robust, then at least one of the key contributors is clearly the scale of government spending. This is a key prop for aggregate demand and a driver of a veritable boom in the military-industrial complex.

As the Economist reports:

Russia’s 2022 budget was planned at 23.7trn roubles ($335bn). Government figures indicate that actual spending in 2022 reached at least 31trn roubles. According to Natalia Zubarevich, an economist at Moscow State University, only about 2.5trn roubles of the extra spend are accounted for by benefits and other transfers: pensions, cheap loans, additional child allowances. That leaves roughly 5trn roubles unaccounted for; much of it, presumably, going on armaments. There are obvious signs of the economy being mobilised for war. Defence firms are working 24 hours a day, in three shifts. Uralvagonzavod, Russia’s main tank manufacturer, has enlisted at least 300 prisoners to fulfil its new orders. And steel production fell by just 7% in 2022, far less than the 15% some expected given the decimation of the car industry, heavily affected by sanctions that have interrupted the supply of semiconductors.

As Bloomberg reports, Russian businesses have responded to the crisis by investing at an unprecedented rate:

Companies big and small spent to replace foreign equipment and software or channeled money into building new supply chains to reach alternative markets. Facing initial forecasts for a decline of up to 20% in capital expenditure, Russia instead saw it increase 6% in 2022, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Beyond the hard core of the military industries, as Volodymyr Ishchenko has argued, Putin’s regime has increasingly resorted to “War Keynesianism”. Large salary payments to soldiers prop up incomes and compensate for higher inflation. They build a constituency loyal to the regime.

There will no doubt be some in Russia who see the wartime moment as a break from the financial corset of austerity and as a strategic opportunity to build a new nation-centered industrial growth strategy, in close partnership with China and possibly India. It is an unlikely prospect, indeed. In fact, as Alexandra Prokopenko argues, the Russian economy faces a decade of regress and mounting dependence on China and its currency.

Much of the investment unleashed by the crisis is make-shift rather than truly productivity enhancing. As Bloomberg reports:

The disappearance of many imports has become one of the forces warping Russia’s wartime economy, driving growth based on less sophisticated technology toward what its central bank termed “reverse industrialization.”

The effects of this investment in import-substitution will take years to make themselves felt. In the meantime, between the short-run of financial crisis, which threatened in the spring of 2022, and the long-run of stagnation that now awaits Russia, there is the middle ground of medium-term macroeconomic management. And this is where the politics will center in the coming year. In this balancing act two things are crucial. First, Russia must manage the bottlenecks imposed by sanctions. This is crucial to avoid sudden stoppages on the supply side. Second, it must ensure that aggregate demand continues to bubble along. In the face of increasingly serious energy sanctions that will be a tougher ask in 2023 than in 2022. But it will not be only a technical problem. It will also be a severe test of the coherence of the economic policy establishment in Moscow.

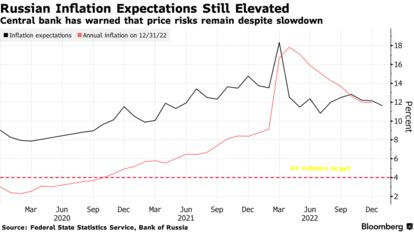

So far the truce between the war economists and the conservative advocates of continuity as personified by Nabiullina has held. It will be interesting to see whether that no doubt tense arrangement can continue into 2023. As in the West it will be fought out over technical questions such as inflation expectations and rate hikes.

Under its most recent outlook last October, the central bank anticipated its benchmark will average 6.5%-8.5% this year, meaning both hikes and cuts are possible. Economists unanimously predict that on Friday the key rate will stay at 7.5% for the third time in a row.

As the Economistsputs it:

However much the Russian economy is forced to cannibalise itself into a more primitive wartime outfit, its governing class understands there is no turning back, at least while Mr Putin is around. It heard the president declare in December that there would be “no limits” to the resources available for the armed forces. That means cuts elsewhere. Health and education spending will be reduced, suggests Ms Zubarevich. Russia’s sovereign-wealth fund, which stands at 10.4trn roubles, or 7.8% of gdp, can be drawn on. “The worse things get, the more necessary war will become,” says one former mandarin.

Will the compromise between the war party and the technocrats be to crush civilian public spending. Or will the budget simply expand? There will be those who ask where the money is to come from?

Russian #budget starts the year with a large #deficit of 1.8 trillion RUB (1.2% of GDP). Highly unusual and points to a larger deficit for the full year (depens on oil price, under current conditions 4-5% of GDP). Liquid assets in the National Welfare Fund amount to 4% of GDP. pic.twitter.com/jPNOJkLp90

— Janis Kluge (@jakluge) February 6, 2023

If Russia is really shifting on to a war footing it is, as far as domestic spending is concerned, an irrelevant question. There is no need to pilfer national welfare funds, other than as a matter of accounting. In a closed financial system, the answer lies with the central bank. But will the central bank play along?

Under the cover of technical argument, huge tensions are tearing at a regime that is caught within a trap of its own making.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

Adam Tooze's Blog

- Adam Tooze's profile

- 767 followers