Adam Tooze's Blog, page 21

April 13, 2022

Chartbook #112 Inflation is hurting, but will it last? Between normalization, Putin’s war and China’s Covid shock.

The current surge of inflation is having a painful impact on the cost of living especially for folks on below average incomes. The key questions are (a) will it last and (b) what can monetary policy do about it?

As Matt Klein makes clear in another excellent Overshoot newsletter, a variety of different factors are at work in the current situation. There is an energy shock, a China Covid-shock and a normalization of the world economy, all operating at the same time.

It is pricey, but if you can stretch Matt Klein’s newsletter does NOT disappoint. Highly recommended.

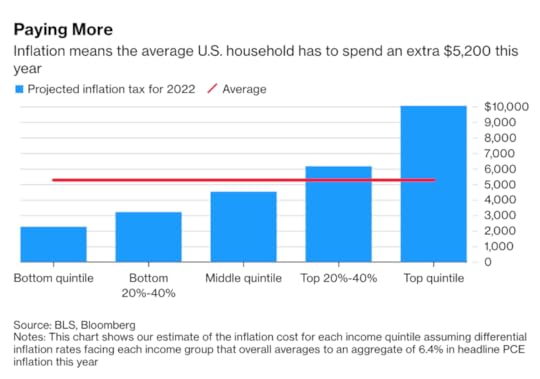

In the short-run the pain being inflicted by rising prices is all too real. According to a striking report over at Bloomberg by Andrew Husby and Anna Wong

Inflation will mean the average U.S. household has to spend an extra $5,200 this year ($433 per month) compared to last year for the same consumption basket, according estimates by Bloomberg Economics. The excess savings built up over the pandemic, and increases in wages, will cushion those costs, and allow spending to expand at a decent pace this year. But accelerated depletion of savings will increase the urgency for those staying on the sidelines to join the labor force, and the resulting increase in labor supply will likely dampen wage growth.

The percentage of Americans who expect to be worse off financially in the next 12 months hit the highest level in at least nine years.

Source: New York Fed via @soberlook

Those sentiment numbers reflect the hard reality that rising prices have been eating into whatever wage gains were made during the COVID shock and its aftermath. Real weekly earnings are now below their pre-COVID trend.

The source for this graph is The Daily Shot, another newsletter you should consider subscribing to if you are serious about following the markets. I love it for its breadth of coverage.

One thing these numbers tells you is that talk of a wage-price spiral is grossly exaggerated. Wages are not keeping up.

Furthermore, it remains true that though the headline figures are alarming,, most forecasters expect inflation in the US to ebb sharply and to fall close to 2 percent by the end of 2023.

We aren’t supposed to call this “transitory inflation”. So shall we call it a “spike”?

It is also important to remember that inflation rates are not the same as price levels. If you are the Biden administration facing the midterms in November, the surge in petrol prices is a nightmare. But once adjusted for general inflation, the current rate of petrol prices in the US, is still some way short of historic highs.

Source: FT

The evidence from the US price numbers suggests that apart from energy the other drivers of inflation may actually be calming. As far as energy is concerned, if Putin’s war pushes prices up, China’s COVID surge pulls them down. And in recent weeks it is the downward forces that have been winning.

What about the lockdowns and supply-chain problems? They could certainly get bad! All eyes on Shanghai. This image from Bloomberg dramatically captures the pile up of bulk carriers off the Chinese coastline.

But as Claire Jones points out at FT’s reinvigorated Alphaville blog, shipping rates are actually coming down. Why? Most obvious answer is that the huge surge in demand for goods in the United States is cooling.

Shipping companies have begun to take an increasingly sanguine view of available capacity going forward.

Whether this lasts will critically depend on developments in China. It is hard to exaggerate the significance of the drama there, as Robin Harding points out in an excellent column.

So, we face serious inflation. It is eating into real incomes. What are central banks going to do? They are determined to raise rates. But will this actually help? It is hard to see how it could do much to calm energy price inflation. But perhaps it will curb demand. That appeals to common sense. But is it actually born out by experience?

I’ll conclude with another amazing find from the Daily Shot.

With the naked eye it is pretty hard to detect any appreciable influence of Fed rate tightening on inflation in the US since the 1980s. Of course we all know about the Volcker shock. But that was extreme. In all the other tightening cycles since 1987 the effect has been virtually invisible.

April 12, 2022

Chartbook #111: What about Greece? Charting a future beyond the debt crisis

In early February 2022 – remember back then when inflation was still our principal concern – the ECB signaled a hawkish turn on monetary policy. What happened next? Italian and Greek debt sold off and their 10-year yields popped.

It wasn’t a crisis by any means, but the tremor was significant enough to set nerves twitching. The last thing Europe needs right now is a new sovereign debt crisis.

Two months on, the level of Greek yields is still elevated. This graph by Yardeni Research puts things in perspective. The current yield on the thinly traded market for 10-year Greek bonds is 2.9 %. That is not 40% as in 2011 – just ahead of restructuring. But it is by some margin the highest in the eurozone. 50 basis points ahead of Italy.

There is a reason that Italy hogs all the attention. Its debts are far larger. And they are held either by private investors (Italian and foreign) or by the ECB. By contrast, as a result of the restructuring in 2012, the overwhelming majority of Greek debt is inter-governmental or held by international organizations, principally in the EU. That means that market pressures are held in check and Greece services its debts at subsidized rates. The ESM (European Stability Mechanism) has a good summary of all the different ways in which Greek debt service costs are massaged down. On average, Greece pays a rate of 1.39 on its loans from the European Stability Mechanism.

That also means, however, that the politics of Greek debt are unmediated. It is government on government, tax-payer on tax-payer.

On April 4 2022 the Greek government announced that it had repaid the last of the 28 billion euros that the IMF had provided in funding in 2010 and 2014. 1.9 billion euros were still outstanding and they were the most expensive debts on Greece’s books. By paying off the IMF, Greece saved 230 million euros in debt service costs. To make that payment Athens needed the permission of the ESM, which waived the requirement that Greece make proportional early reimbursement of its loans to EU authorities. Everything is political.

IMF, EMS, proportional payments … just like that, we are back in the dark night of the debt crisis. Or not?

The remarkable thing is just how easily Greece came through the COVID crisis of 2020. This is despite the fact that Greece adopted what was proportionally the largest direct fiscal policy response to the COVID crisis anywhere in Europe. It needed to, In 2018 the WTTC estimated that tourism and travel contributed 20 percent to the Greek economy. If that figure seems inflated, there is no doubt that COVID was a severe shock for which the New Democracy government, despite its supposed conservative commitments, amply compensated.

Source: IMF

Athens did not just rely on “automatic” stabilizers i.e. unemployment benefits. It delivered a big discretionary burst.

For the second time since 2008, a conservative Greek government responded to a global crisis with a huge fiscal stimulus and a surge in debt.

Source Alogoskoufis Voxeu

In 2009, this bequeathed to the incoming PASOK government an epic financial crisis. In 2020 at far higher debt levels, there was no reaction from debt markets. Indeed, until the ECB’s swerve to conservatism in early 2022, Greek yields were at historic lows.

Why the calm? Because unlike after 2009, in 2020 the vast majority of Greece’s debt was already in public hands and the ECB was scooping up the rest.

Hitherto the ECB had been barred from doing this. To be included in the normal ECB Asset Purchase Program, a country has to have an investment grade rating, which Greece lost in 2009. In 2015, when Mario Draghi launched QE for the Eurozone, rather than helping Greece it boxed the left-wing Syriza government in. Whereas all other members were supported, Greece was left at the mercy of the markets. And because of ECB support there was no risk of contagion spreading from Greece to any other member states. Athens lost all bargaining power.

By contrast, in 2020 under the pandemic purchase program, the ECB was free to intervene. Even as Greek debt surged to the dizzying level of 220 percent of GDP, yields remained contained. On top of that, Greece under Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis is one of the largest recipients of NextGen EU aid.

On that basis, despite the setback of the crisis, Greece’s government makes a cheerful prognosis of economic growth with real GDP rising on official projections from just under 170 billion euros in 2020 to just shy of 210 billion by 2025. The IMF is slightly less optimistic, but there is no doubt that in 2021 Greece was one of the fastest growth rates in Europe. And far from arguing for restraint and urgent fiscal consolidation, the IMF’s advice to Athens in the spring of 2022 was complacent. Avoiding economic “scarring” was the priority (sic).

The fiscal adjustment should be gradual and growth friendly. The mission recommended a gradual consolidation path to achieve a primary surplus of 2 percent of GDP by 2027, underpinned by credible measures. Plans for permanent cuts in social security contributions and in the solidarity tax for all taxpayers should be reversed, as they shift the burden to future generations and are poorly targeted, or at least fully funded through benefit adjustments respectively base‑broadening measures. The mission welcomed improvements in the fiscal mix achieved during the pandemic, notably higher health care spending and public investment, and emphasized that these gains should not be sacrificed to achieve consolidation targets. Instead, spending pressures on pensions and civil service wages should be contained, including by respecting the pension freeze this year and the indexation formula from next year onwards. There remains ample scope to improve the fiscal policy mix further by phasing out transfers to public enterprises and fuel subsidies over the medium term and tackling tax evasion by the self-employed to make room for critical social spending and recurrent investment needs once NGEU funding ends. Accelerating fiscal structural reforms would facilitate these efforts.

To put it mildly, this was not the advice that Athens received between 2010-2018. After 2009, on the basis of faulty economic predictions and bad economics, Greece was driven into one of the most devastating economic crises on record. As bad, but far more sustained than America’s Great Depression of the 1930s.

Source: IMF

As employment collapsed, unemployment surged to 28 percent.

Looking back on this devastating experience, which shocked Greek society and broke the back of first PASOK and then Syriza, my hosts on a recent trip to Greece, the newly-founded progressive research institute Eteron wondered out loud: “Was it us who had to pay the price so that the IMF and the EU learned their lesson?”

And now with the ECB signaling a turn to rigor and the clock running out on the Pandemic Purchase Program, the question is how long can the calm continue?

Greece remains a nation under surveillance. To keep the debt politics show on the road, Greece’s future is mapped as far ahead as 2060. That is further ahead than the anthropocenic timescale of climate politics!

Under its “enhanced surveillance regime” the European Commission has even managed to construct a “baseline” scenario in which Greek debt falls to 60 percent of GDP by 2060, thus meeting the Maastricht criteria under which Greece entered the Euro back in 2001. To generate that prediction, all you have to assume is that interest costs remain under control. Greece runs a primary budget surplus of 2.2 percent of GDP for forty years and, at the same time, sustains nominal GDP growth close to 4 percent. What you have not to do is to linger over how realistic any of that is.

In fact, in the economic history of comparable societies, the IMF could find only eight examples since 1945 of countries that have managed sustained primary surpluses of more than 2 percent over 40 years. Since 2008 the only country to achieve that feat was oil-exporter Norway, and it fell off the wagon in 2014.

As far as Greece is concerned, the IMF concludes, to imagine that a sustained surplus of 2.2 of GDP is possible goes against all previous experience.

The largest surplus that the IMF considers viable in the long-run for Greece is 1.5 percent of GDP. A debt sustainability analysis conducted on that basis results in a range of plausible scenarios in which debt stabilizes between 160 and 120 percent of GDP by 2060. To aim for any tighter fiscal policy is likely to be counterproductive both in political and economic terms. As the IMF comments:

Greece’s long-term debt sustainability hinges on long-term fiscal discipline to sustain a high level of primary surplus, structural reforms to unlock long-run growth potential, and stable financing conditions to contain the risk-free rate and risk premium. A continued active debt management strategy will also be critical, …The scenario analysis shows that fiscal underperformance (due to policy choices and/or shocks), growth disappointments, a return to historical levels of risk-free rates, stronger sensitivity of risk premiums to debt levels, and/or shortening of new debt maturities would quickly lead to unsustainable debt dynamics over the long-term, necessitating policy adjustment and/or further financial support from European partners.

Given all of those imponderables, the IMF concludes:

… Greece’s long-term debt dynamics are too uncertain to reach a firm conclusion

The one thing that does seem clear, however, is that Greece’s story of convergence with Western Europe is over. The single most staggering graph in the IMF’s Article IV assessment from the summer of 2021 is this one:

Twice over Greece has experienced an optimistic boom, bringing it within striking distance of German GDP per capita. Twice over it has been shocked off that growth path. Once in the 1980s and then, even more savagely, after 2009. None of the future scenarios envisioned by the debt analysis implies strong convergence over the next forty years.

Instead what Greece experiences is chronic underemployment and a serious shortfall, relative, to other EU members, in vital social spending on childcare, housing and other key benefits. The principal victims of this shock and the ensuing dislocation and diminished expectations are young people. It is for that reason, that the Eteron Institute is turning its attention above all to generation Z.

It is early days for an Institute that hopes not just to serve as a platform for new thinking, but also to shape opinion. As veterans of the first Syriza government, the organizers of Eteron are clear-eyed about the challenges this involves. It was eye-opening at the Delphi Economic Forum to discuss the dimensions of the global policycrisis and its implications for Greece with Gabriel Sakellaridis Eteron’s founding director and spokesman in 2015 for the Tsipras government.

Again and again – in the revolution of 1821, the population exchange of 1923, the aftermath of World War II, the Cold War and the financial crisis of 2008 – Greece has been a fulcrum of history. It is beautiful, littered, literally, with ancient and modern culture and, at the same time it is a laboratory, not to say a petri dish of radical change. In the decades ahead, whether it be the politics of the welfare state, intergenerational equity, climate change, the refugee crisis or the geopolitics of the Eastern Mediterranean, Greece will be in eye of the storm.

April 10, 2022

Chartbook #110: Being There – Last Call At The Hotel Imperial

“The consciousness that I live in a revolutionary world is the central fact in my life. I go to sleep and I awake thinking of the world in which I live. My whole personal life has become in a profound sense of secondary importance, and indeed, it, so immediate and so practical, is the part which is dream-like and unreal, and the other, more remote, touching me personally so little, is the imminent, the overwhelming reality. At the center of what I know is the realization and the acceptance of the certainty that never in my lifetime will I live again in the world in which I was born and grew to maturity.”

These words were written by Dorothy Thompson in January 1937 in an essay titled, “The Dilemma of the Liberal” published in Story magazine.

Thompson was at the time one of the most influential and well-known journalists and commentators in the world. She was at the center of a group of American foreign correspondents, sometimes associated with the “lost generation”, who reshaped American understanding of world politics and foreign affairs in the interwar period. Thompson is at the center of a complex web of personal, professional and political relationships unpicked with exquisite care and insight by Deborah Cohen in her wonderful new book, Last Call at the Hotel Imperial.

Any new book by Deborah Cohen is an event. Family Secrets and Household Golds were extraordinary displays of historical imagination and intellectual creativity, opening up the past in new ways.

Last Call has all the hallmarks of Cohen’s craft but to my mind it also has a singular urgency. It is also, it should be said, entertaining and at times moving.

So why does it matter?

Dorothy Thompson, Vincent Sheean, H.R. Knickerbocker, John and Frances Gunther traveled interwar Europe, Middle East and Asia. They were connected. They interviewed everyone. And at the same time they experimented in flamboyant ways in their private lives.

As Cohen recounts:

Steven Marcus (in a review of Sheean’s Dorothy & Red) judges both Thompson and Lewis as entirely externalized people – “abstract and depersonalized,” calling their marriage “more like a treaty or trade agreement between two minor nations than what is usually thought of as a marriage.”

And, as Last Call brilliantly shows, they struggled to related the public and private spheres of their existence and to historicize the relationship between the two. As Dorothy Thompson remarked in “The Dilemma of the Liberal”:

This life which you lead, a voice says to me continually, is in the deepest sense senseless; a repetition of social gestures, somehow hollow; it ties to noting, it is part of nothing. It is a dream, and the reality lies elsewhere … this nucleus, myself, my husband, my child, the people dependent on us and our friends, should somehow tie up and be part of a larger collective life, be integrated with it thorough and through. My parents’ life was. They were adjusted to themselves and to society. But the security of our world stops at our doorstep. “I am wounded in my fundamental societal impulses,” cries a man of genius, of my generation, in a burst of agony. What D.H. Lawrence felt, I feel, continually, overwhelmingly. It is not enough to say that he was an ill man we are both neurotics. Or rather, this neuroticism, if it be such, is epidemic. … I am giving publicity to my symptoms only because they are endemic, I believe, to the largest section of western intellectuals.”

This tension was a dilemma for Thompson as a self-identified liberal, because her sense of being wounded in her “fundamental societal impulses” made her sympathetic to an uncomfortable degree with the more radical politics of the era.

“… I could not accept the communist doctrine, still less could I accept the Nazi … Yet I share the discontent with existing society which made both movements possible. I cannot read half the newspapers or see the average Hollywood film without feeling ever so little like a Nazi, or observe the irresponsible antics of some of the rich, without feeling like a communist.”

Of the Communists she remarked,

I whom individualism and skepticism had set adrift in a world where everything was challenged and nothing believed, was drawn to these taut young people almost enviously.

And it was not just a psychological or emotional attraction. There was also a hard political lesson. Thompson had witnessed the fall of the Weimar Republic close up, but what really moved here was the destruction of Austrian social democracy in 1934.

When, later, the guns were turned against Vienna Social Democrats, and destroyed the only society I have seen since the war which seemed to promise evolution toward a more decent, humane, and worthy existence in which the past was integrated with the future, real fear overcame me, and now never leaves me. In one place only I had seen a New Deal singularly intelligent, remarkably tolerant, and amazingly successful. It was destroyed precisely because it was insufficiently ruthless, insufficiently brutal. “Victory” (I saw) requires force to sustain victory. I had wanted victory, and peace.

Something else was required.

Ultimately, it is tempting to say that Thompson’s extraordinarily prominent role in America’s war effort in World War II, would bring her the closure that she craved in her 1937 essay.

The war would catapult other individualist and skeptical intellectuals too into a convulsive embrace of history. In France one thinks, immediately, of Sartre, de Beauvoir and Merleau-Ponty.

Fascinating as the Parisian super stars are, it is tempting to say that their extraordinary intellectualism makes them less representative of broader patterns of change. Most people did not negotiate the shock by way of Heidegger, phenomenology, or Kojeve’s reading of the master-slave dialectic.

By contrast, Deborah Cohen’s group are eminently relatable. They were part of a new cohort of College-educated men and women. They wrote for a broader audiences in fluent and accessible prose. And as Cohen’s deft reading reveals, this signified something quite fundamental.

In his classic text, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origina and Spread of Nationalism, Benedict Anderson explained how in the late 18th and early 19th century, the genres of the novel and the newspaper had helped enroll their readers in a new communal understanding of time. As Anderson, the anthropologist, saw it, a temporal frame defined by religion and monarchical sovereignty was replaced by a new perception of continuous, but eventful historical time. Individuals came to understand themselves as belonging to communities that progressed through history as quasi-organic wholes, in which individual mortality was subsumed in a collective immortality. No one could escape the collective story but it was also the ultimate source of meaning.

If the emergence of collective historical consciousness in its modern sense can be dated to what Reinhart Koselleck called the “saddle period” around 1800, what Cohen shows us is how in the early 20th century the nexus between history, the collectivity and the individual was disturbed for a second time.

Nineteenth-century certainties were blown apart by the explosion of violence and of economic crisis unleashed by World War I, which threw visions of regular historical development into question. At the same time the nexus of individual and collectivity was also disturbed by the putting into question of individual subjectivity by the widespread popularity of notions derived from Freudian psychoanalysis and a fundamental renegotiation of gender roles, sexual desire and identities.

A century on from the Anderson/Koselleck moment, the relationship between the individual and the collective was in flux. As Cohen notes, this was also a central preoccupation of the pragmatist movement, as exemplified by John Dewey.

The whirlwind of the individual and collective was all the more destabilizing for the fact that individual men had suddenly come to take on a larger than life importance in world history. As Cohen puts it:

liberals or conservatives (had not, AT) devoted much attention to the transformative power of the individual leader. 7 No matter how powerful politicians such as David Lloyd George or Raymond Poincaré were, they represented the distillation of the energies of their parties and their people. In that sense, they were interchangeable with another statesman. 8 But by the early 1930s, when Knick and John feuded in a Vienna café, it was clear that the “authority of personality,” as Hitler put it, mattered more than it ever had in their lifetimes. 9 One couldn’t account for what was happening otherwise. The individual leader, as Knick wrote, now counted for “nearly everything.” 10 They were the ones fomenting the world crisis: it was happening within them and through them. When the fate of the world hinged upon a handful of men, personal pathologies became the stuff of geopolitics. The correspondents needed a new way of thinking about the role of the individual.

One might take issue with this juxtaposition between liberal politicians and the personalistic fascist “leaders” of the interwar period. Lloyd George and Clemenceau were both charismatic figures in their own right and acknowledged as precursors by Mussolini and Hitler.

The fascists thought of themselves as giving their states the kind of personalistic leadership, which Britain and France had benefit from, but Italy and Germany had lacked in World War I.

But the point is well taken. One of the great challenges of comprehending interwar history is how to craft a general narrative of history if it depends on individual personalities to this degree.

John Gunther in particular developed an overarching theory of history shocked into motion by the happenstance of individual personality. As Cohen suggests there is an interesting contrast between Gunther’s understanding of history and that being developed at the time by anthropologists like Margaret Mead that also centered on questions of character.

The contrast with the work of contemporary social scientists, notably the anthropologist Margaret Mead, is striking. 67 Mead and her colleagues were trying to understand the workings of national character: why – say – the Germans submitted willingly to dictatorship or the Americans demonstrated a stubborn, wary, independence. Such “culture-cracking,” they believed, could be marshalled to defuse international rivalries, or to win a war. Their analysis, like John’s, was indebted to a sort of Freudianism, requiring the investigation of child-rearing practices and generational friction. However, the sense of what mattered most was very different. As John Gunther saw it, individual personality had jolted history into a new gear. He was making an argument about accident rather than deeply ingrained patterns of culture.

On Mead’s work, Peter Mandler’s Return from the Natives How Margaret Mead Won the Second World War and Lost the Cold War is brilliantly illuminating.

Whereas correspondents like Gunther and Knickerbocker tended to preserve the dignity of their interviewees by not probing too deeply – their access depended on being at least minimally polite – and thus tended to reinscribe the importance of the great man, others in their circle were more skeptical. Frances Gunther, who is the pivot of much of Cohen’s narrative, was particularly impatient with her husband’s superficial treatment of the great figures of the day.

Frances was a Marxist but she was also a Freudian, which meant that she thought that an investigation of personality in light of the formative experiences of childhood was imperative. But she thought John and his friends were going about it the wrong way. For one thing, they were far too cautious about what they put in print. Why wouldn’t they just write the truth – that Poland’s Marshal Piłsudski was subject to psychopathic temper tantrums and Turkey’s Kemal Atatürk was a mother-fixated drunk? 47 Tear the veil off the dictators, she urged her husband.

Even more scathing was Vincent Sheean, who was both the most hell-raising and wildly experimental of the group and perhaps the most profound in his struggle with the intertwining of history and subjectivity. Amongst his diverse bibliography is a translation of Croce’s Germany and Europe.

Sheean more than any of the group experienced the radical blurring of the boundaries between the personal and the political. Whereas Thompson was suffering from a sense of malaise in the late 1930s, the news from Spain triggered in Sheean a full blown psychosomatic collapse.

That month, devastated by the events in Spain, Jimmy collapsed in Ireland. He and Dinah, and their two-month-old baby, were staying at a friend’s country house in County Meath. Years later, when Jimmy told the story, he readily acknowledged he’d been on a drinking binge. But that didn’t even begin to explain the whole thing, he insisted. To account for what happened to him, you had to understand about Spain. The nervous breakdown came first. The night that Franco launched his coup attempt, Jimmy was off his head, delusional, bellowing at the top of his voice. The Irish doctors had him sedated and when that wasn’t enough, they bundled him into a straitjacket. Next came his physical collapse. He frothed thick yellow at the mouth for days; he was burning up with a fever. In succession, his lungs, liver and kidneys failed, and in a Dublin hospital, he slipped into a coma. 105

Improbably given his lifestyle, Sheean outlived all the other members of the group. In 1963 he would begin the work of unpicking and analyzing the relationships that bound together his contemporaries with his warts and all biography of Dorothy Thompson and Sinclair Lewis, Dorothy and Red (1963). But the book that made his name and framed the question that Cohen so brilliantly expounds, is Sheean’s Personal History (1934). As Cohen aptly summarizes it,

It was a coming-of-age story, his own and the world’s, brought together. He was mapping his own development as an individual onto the world crisis. The young American sheds the insularity of his station and upbringing to experience events for himself. He arrives in an Old World where the Victorian certainties – about the legitimacy of European empires, the beneficence of capitalism and free trade, the inevitability of progress – are in tatters. Through his reporting, he takes the measure of the new forces rising: the power of collectivism, especially Communism, and the strivings of colonial nationalism. Eyewitness to violent battles on the periphery, he sees that the twentieth-century movements are uncontainable and that the old order of class inequality and imperial exploitation cannot and should not be restored. More than that, he comes to understand, under Rayna’s influence, that the struggle to right the world’s wrongs is his own. He had to find his “place with relation to it,” he wrote on the final page, “in the hope that whatever I did (if indeed I could do anything) would at last integrate the one existence I possessed into the many in which it had been cast.”

Rayna was Rayna Prohme, a globe-trotting revolutionary who Sheean met and became infatuated with in the Communist-led enclave of the Chinese revolution in Hankou. Amidst the White terror unleashed by Chiang Kai-shek, Rayna and Sheean fled to Moscow where they were joined in 1927 by Dorothy Thompson, all of them eager to witness the ten-year anniversary celebrations of the 1917 revolution. On 21 November Rayna suddenly died, whether of encephalitis contracted in China or of a brain tumor remained unclear.

Sheean was devastated. Personal History is amongst other things an extended meditation on the debates he was having with Rayna up to the moment of her death and beyond. Her committed communism was the foil to his individualist search for meaning. Her devotion to revolutionary action stood in contrast to his sense of himself as an observer and chronicler not an actor in history. For Sheean as for Thompson the question was how to achieve meaningful integration.

In the final pages of Personal History, Sheean brings Rayna back to life as his guide, conceding to her the argument they left unfinished in 1927, the anniversary year of the revolution.

“I’m no revolutionary”, he imagines himself protesting. “I can’t remake the machine ..”. To which she replies:

“You don’t have to! All you have to do is to talk sense, and think sense, if you can. … Everybody isn’t born with an obligation to act. … But if you see it straight, that’s the thing: see what’s happening, has happened, will happen – and if you ever manage to do a stroke of work in your life, make it fit in. … if you are in the right place. Find it and stick to it: a solid place, with a view.”

Then, as Sheean imagines Rayna continuing:

“If you want to relate your own life to its time and space, the particular to the general, the part to the whole, the only way you can do it is by understanding the struggle in world terms … to see things as straight as you can and put them into words that won’t falsify them. That’s programme enough for one life, and if you can ever do it, you’ll have acquired the relationship you want between the one life you’ve got and the many of which it’s a part.”

As Sheean concludes:

…. even if I took no part in the direct struggle by which others attempted to hasten the processes that were here seen to be inevitable in human history, I had to recognize its urgency and find my place with relation to it, in the hope that whatever I did … would at least integrate the one existence I possessed into the many in which it had been cast.

Echoing the prose style of its subjects, Deborah Cohen’s Last Call is a compulsively readable work of history and essential contribution to understanding modern America’s relationship to the world.

As she describes her method:

My aim as author has been to follow their own lead as journalists – to convey how it felt to live so exposed to history in the making. When I indicate what a person felt or thought, I am always drawing upon documents to be found in the archives. Their reportorial method was intimate and immediate, and as I worked in their papers, it often felt like walking in on an argument. Even when they were far apart, even after they fell out, they kept right on talking and arguing, long after the actual conversations had ended.

Reading Last Call, I could not help feeling that the conversation that they began continues on to the present day.

For me Last Call reads as a brilliantly illuminating examination of the excitement and the peril of thinking and writing in medias res. How was one to cope with the forces of world history sweeping through the living room, Sheean’s long-suffering wife Dinah Forbes-Robertson was moved to wonder after his breakdown during the Spanish civil war. And as global geopolitics, pandemics, inter-generational stresses, technological change, economic crises, urban crisis, and the renegotiation of gender roles and sexuality continue to upheave our lives, those questions are still with us today.

Read through the lens offered by Deborah Cohen’s Last Call, Sheean, Thompson et al appear as our precursors, our predecessors and our contemporaries in navigating polycrisis.

********

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But it is voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters that sustain the effort. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

April 9, 2022

Chartbook #109: War at the end of history

War and history are intertwined. Entire conceptions of history are defined by what status one accords to war in one’s theory of change. War is certainly not the only way to punctuate history, but it is clearly one of the pacemakers. Battles and campaigns are not the only events that define winners and losers, but they do matter. In its heyday war was the great engine of history.

One of humanity’s recurring hopes has been that through history we might escape war. Since World War II Western Europe in particular has been invested in the idea of consigning war to the past. That is a hope that is based not just on a humanitarian impulse, but also on the sense that the basic questions of international politics were resolved and that for the settlement of whatever remained, the modern instruments of war – most notably nuclear weapons – were likely counterproductive. The era of military history was thus consigned to an earlier developmental phase.

If it was once sensible to think of war as the extension of policy by other means, historical development had closed that chapter. Both the main questions of policy and the repertoire of sensible policy tools have changed. With the passing of that epoch, war belonged to the past. Skepticism about war was not, first and foremost, a matter of moral values, it was a matter of realism, of understanding what actually made the modern world tick.

From this point of view, if major powers did “still” engage in war – as many regrettably did – it was either a sign that they were regressing to an earlier stage of statecraft, under the malign influence of reactionary elites. Or the elites in question had fundamentally miscalculated, not grasping the real stakes, or the proper means with which to pursue their best interest. Or the war in question was simply not very important, less a historic turning point than an atavistic indulgence. “Wars of choice” are an occasion to show off the raw power of the state without facing serious resistance.

All three modes of interpretation could be brought to bear on what to date was the biggest war engaged in by major powers in the post-Cold War period – the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Russia’s assault on Ukraine is shocking, therefore, not only for its violence, but for the fact that it reopens the question of war as such and thus also the question of history.

The weight of this question first impressed itself on me in the third week of February – in that blessed interval when it seemed that the COVID pandemic in NYC had passed, but before Putin actually launched his attack on Ukraine.

To be specific it was on Tuesday 22nd February when I had the pleasure of discussing the daring new book by Alex Hochuli, George Hoare and Philip Cunliffe, The End of the End of History, with one of its authors, Alex Hochuli.

It was a particular pleasure to debate with Alex Hochuli because he and I had previously gone back and forth on his “Brazilianization”-thesis of the 21st century.

In the End of the End of History, Hochuli, Hoare and Cunliffe offer a daring rereading of Fukuyama’s end of history thesis. They spell out the class politics of the end of history, the depoliticizing logic of neoliberalism and postulate a dynamic through which it will be surpassed and overcome. The supposed conclusion of history in which all fundamental ideological conflicts are resolved, produces, they suggest, its own gravediggers.

Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian media mogul and prime minister with his notorious “Bunga parties”, is for them both an archetypal figure of the end of history and an emblem of the fact that that epoch cannot endure. We are all caught up, as they gloriously put it, in “Aufhebunga Bunga”, a bit of Dada-theory doggerel that one hopes will enter the general vocabulary.

On that tip, their podcast Bungacast, is great listening.

But, if it is true that history has a tendency to restart, the question is, what key will it restart in?

Working from a Marxist framework, Alex and his co-authors pose the question of politics and history above all against the background of class analysis. Can the neoliberal paralysis of politics and history really endure? Will it not, in the end be destabilized and blown open by an insurgency of what they call “the masses”? Is so-called populism one of the forms that explosion will take?

Alex and I had a fascinating exchange about their class analysis and this takes up most of the time in the video. But I will admit that my mind that evening was on the possibility of something even more urgent. Speaking to military analysts earlier in the week it had been born in upon me that Russia’s forces were poised to attack.

What if history was restarted but on the other axis of modern history-making? Not class struggle, but war? And, if so, what kind of war would it be? This was the question I started wrestling as of minute 39 in the video. That question would be answered on February 24, two days later.

Following the conversation with Alex Hochuli, Gavin Jacobson, another avid reader of Fukuyama, asked me to elaborate on the question of war at the end of history. What came out is the essay that appeared this week in the New Statesman.

The original starting point for the essay was the fact that, as Gavin reminded me, in the final chapter of The End of History, Francis Fukuyama had anticipated a strong-man figure who might want to overturn the end of history by force majeure. This figure would want to restart the struggles of the past, to restore meaning and humanity to existence, almost regardless of ideological content. It would be the struggle for status that mattered, per se.

That ran contrary to Stephen Kotkin who reads Putin as a direct descendant of the lineage Russian expansionism that goes back to Ivan the Terrible.

Others have labeled Putin as a “19th-century man” stuck in a 21st-century world.

I am not convinced by any of these interpretations. Let us not grant to Putin and his war such a distinguished pedigree or such radical intent. Let us instead locate Putin where be belongs. In our epoch. Whether we like it or not, Putin is our contemporary.

Putin with Bono, Blair and Bob Geldof, from the Russian Presidential website.

As the war in Ukraine was originally conceived, it was, as I put it somewhat flippantly on February 22nd, a “Bunga war” – frivolous, gratuitous, neither a serious act of great power politics, nor a dramatic effort to restart history.

The original invasion plan, possibly cooked up by intelligence officials rather than soldiers, seems to have been to seize Kyiv, the Presidential offices and the TV stations by a coup de main. That failed. And then Plan B, the large scale air assault and standard Red Army encirclement of Kyiv, also failed.

That has left Putin fighting for his own regime’s survival, his military flailing, a war consisting less of coherent operations than a string of atrocities. Whatever the flow of battle on the ground, Russia has lost the ability to control the narrative through which the war is made sense of outside Russia’s own immediate orbit.

The really interesting thing is not so much Russia’s intent, but why it failed. In part it was incompetence and bad planning. Many of the Russian soldiers do not seem to have realized that they were actually engaged in an invasion at all – a Bunga syndrome if ever there was one. Propagandistic pastiche and violent reality merged completely in a manner reminiscent in some ways of the January 6th riot in Washington DC.

The harsh reality that Russia’s dazed invaders came up against – at least as far as our media allow us to glimpse it – was Ukrainian resistance backed by unexpectedly significant support by NATO.

So if the Ukraine war marks a a break, to put the emphasis on Putin may be misguided. If the honor of rekindling history, of “returning us to the 19th century” belongs to anyone, it is not to Bunga-Putin. That honor belongs to the Ukrainians.

It is the Ukrainians, to the amazement and not inconsiderable embarrassment of the West, who are enacting a drama of national resistance unto death. Under Russian attack, they are bonding together and demanding recognition of their sovereignty. There are many other peoples who are struggling for their existence and recognition today. The difference is that the Ukrainians do so in the classic form of a nation in arms rallying around a nation state. And the Ukrainians do so efficaciously. They have turned back a Russian army. They have saved their capital city. Those are not merely symbolic achievements.

Looking back at the conversation with Alex Hochuli I cannot but think of one of the most impressive passages in their book, which I quoted to him on the evening of February 22nd.

Hegel’s claim about the End of History did not rest on the durability and stasis of the post-Napoleonic settlement, but rather on the irreversible character of certain historic developments with respect to our collective self-understanding. Most important of these was the universality of freedom within the modern world that had been unleashed by the French Revolution. In Hegel’s view, the specific historic gain of the French Revolution was to reveal the universal character of human freedom, that is, the claim that freedom is in fact part of being human. Freedom was thus not merely an abstract philosophical proposition, but a political proposition that could be realized in concrete institutions. This was Hegel’s original meaning of the End of History – that whatever followed the French Revolution had to be based on the universal claims of human freedom. This in turn meant that no social or political order could ever be fully stable. The significance of this insight is that freedom cannot be limited or appended to one specific regime or order, as it is precisely the expansiveness and restlessness of human freedom that exceeds any one specific set of political and social institutions. It is this that explains how there can be a finality to the historic process – after the French Revolution, the irreversible and simultaneously contradictory character of human freedom serves as a backstop to history … Hegel’s real insight is that no order founded on human freedom can be ossified; all ends of history end, all modern political orders are eventually remade.

Hochuli, Alex; Hoare, George. The End of the End of History (pp. 33-34). John Hunt Publishing. Kindle Edition.

If Hegel talked of freedom in a collective sense, is it not likely that he had, amongst other things, in mind the example of the French revolutionary wars and Napoleonic wars? And to that degree is it not legitimate to extrapolate to the struggle of Ukraine today?

When we talked that evening in February, neither Alex or I – I think – conceived of what was to come next. (Read the book, watch the video and judge for yourselves). I spoke about war, but I anticipated a “Bunga war”, a brutal show of Russian force that crushed Ukraine. What we did not anticipate was a protracted and successful struggle for survival that would put Putin too at existential risk.

With Russia and Ukraine locked in battle, the question becomes how will the Western powers respond? It is up to them/us! As I put it in the New Statesman article, the End of the End of History will be what we make of it. That is what is at stake both in the war and even more in the peacemaking that must follow. How will order and freedom be combined in Europe?

For their interesting reading of Hegel, by the way, Hochuli, Hoare and Cunliffe draw on Todd McGowan’s book on Hegel, Emancipation after Hegel: Achieving a Contradictory Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

For my own part, this exchange with Alex Hochuli and Gavin Jacobson brought me back to an interest in Fukuyama’s end of history thesis that goes back to the early 2000s. In particular Perry Anderson’s reading of Fukuyama in Zones of Engagement changed the course of my intellectual life.

The most immediate impact was in the form of a course that I taught at Cambridge in 2006 and 2007 that built a series of sessions around the dialectic that Anderson traces from voluntarism – the sense of being able to make history by an act of will – to exhaustion of historical agency, at the end of history.

It was a fun course. The session titles were as follows:

Making History: The Hegelian Marxism of Lukacs, Gramsci, GentileThe End of History: Kojeve’s Hegel, Stalinism and the new EuropeTerror and the open-endedness of history: Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, Camus, Merleau-PontyNazism and the eclipse of reason: Architects of Annihilation and the Dialectic of the EnlightenmentModernizing Europe, Convergence, End of IdeologyFrom History to Biology: Herbert MarcuseHistory restarts? 1968-1978 The Crisis of Governability1989: Another endingYou can download the full syllabus here. Making History, Ending History Dec 2006

****

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But it is voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters that sustain the effort. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

April 8, 2022

Ones & Tooze: The Fall and Rise of the Russian Ruble

Western sanctions on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine quickly led the Ruble to lose more than 45 percent of its value. But these days, the Russian currency is back to its pre-war value. Cameron and Adam explain the turnaround and discuss what it means for the war.

Also on the show: The economics of canned fish.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

April 6, 2022

War at the end of history

It was the French Revolution that defined the stakes in modern war as an existential clash between nations in arms, in which fundamental principles of rule were in question. War was the world spirit on the march. That is what the German poet Goethe thought he witnessed at the Battle of Valmy in 1792, where a rag-tag revolutionary army unexpectedly turned back a much better-equipped counter-revolutionary invasion by royalist and Prussian forces. “From this day forth,” he wrote, “begins a new era in the history of the world.” Two days later, the French Republic was declared.

A “world-soul” on horseback is what Hegel thought he saw, as Napoleon cantered through the city of Jena in October 1806 on his way to the battle that would push the Prussian state to the brink of extinction. War was not simply a violent practice of princes, a duel writ large. War was History with a capital H – the “slaughter-bench”, Hegel would call it – “at which the happiness of peoples, the wisdom of States, and the virtue of individuals have been victimised”. It was something both fascinating and horrifying. Transformative and yet also on the edge of tipping over into absolute violence, as in the horrors of guerrilla war in Spain, depicted by Goya. Two centuries later, in the commentary on the war in Ukraine, one can feel the same spirit stirring.

The spectacle of war has always evoked mixed emotions. On the one hand, enthusiasm and something akin to relief: here, finally, is real politics, real freedom. And, on the other hand, horror at the violence, suffering and destruction.

In the wake of Waterloo in 1815, both diplomacy and contemporary social science tried to put the genie back in the bottle. For all his grandeur, Napoleon had been defeated. Millions had died in the global wars sparked by the French Revolution, and his project of modernising empire had come to naught. The lesson, according to the followers of the sociologist Auguste Comte, was that the future belonged to industry, not to the soldiers.

War, however, refused to be tamed. Contrary to myth, the 19th century was not an era of peace. Colonial wars and massacres merged in the middle of the century with a surge of violence triggered by the formation of nation states: in Italy (1861), in the US (1865), in Japan (1868) and in Germany (1871). Massed armies, mobilised by railways and equipped with lethal modern weapons, wrought terrifying destruction. The violence escalated further in the 20th century, with the series of wars spanning Eurasia that began with the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and ended in Korea in 1953.

Read the full article at The New Statesman

Chartbook #108: Containing the global shockwave – the real battle to shape the post-crisis world economy.

Did a piece for Foreign Policy on the global economic shockwave from Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

We have had a lot of debate about the way in which the war might trigger a challenge to dollar-hegemony from a new, ruble-yuan nexus – see Chartbooks 94, 106 and 107. I’m unconvinced and impatient with that debate.

In the new FP piece, I argue that it is time to stop worrying about distant Fin-Fi scenarios and to focus instead on the immediate fallout of this shock. The most ugent question right now is how the managers of the dollar system deal with the mounting pressures within that system.

One of the fallacies of the current moment is to imagine that Putin has rudely disrupted an otherwise functional system. In fact, the signs of tension amongst the more fragile low-income and emerging market economies have been mounting for years. And there is little reason, given the recent track record, for struggling low-income and emerging market economies to expect much constructive help.

As I discussed in Shutdown, following the COVID shock of 2020 there was no adequate global response to the debt service problems of the low-income countries. The so-called DSSI initiative was derisory. Rather than debt relief, the main prop for low-income debtors were the falling price of imports and the ultra-low interest rates adopted by the Fed, which unleashed a tidal wave of money looking for yield. Now, energy prices and food prices are rising and so too are interest rates in the dollar zone. Even the normally upbeat Economist has been warming of a “triple whammy”.

As Lee Harris reports in this excellent article in The American Prospect, this combination of pressures has set alarm bells ringing at the UN, World Bank and IMF.

Harris points to a report by the UNCTAD economics team, aptly titled Tapering in a Time of Conflict.

It warns that

For many developing countries, currency devaluation against the dollar is an important driver of inflation: domestic currency depreciation raises the domestic price of imported goods and therefore headline inflation measures. As the Fed and other central banks in developed countries central banks tighten, the currencies of developing countries are likely to devalue further. Policy tightening in the North, in response to supply-side bottlenecks, thus worsens the problem of rising prices in developing countries.

To counter the cycle of devaluation and inflation, EM and low-income markets have respond by sharply raising interest rates, which creates the risk of stagflation. Russia is the extreme case, where the West has induced chaos by deliberate action. But there are some low-income debtors who are not far behind.

Richard Kozul-Wright of UNCTAD is also the co-author with Kevin P. Gallagher of a bold new book making The Case for a New Bretton Woods.

While I am wholly sympathetic to their objectives, I should admit that I have long been a skeptic when it comes to new Bretton Woods proposals. Where is the agency?

Bretton Woods is commonly described as a “postwar conference”. But it was, in fact, convened by tightly coordinated wartime alliance. It met in July 1944 in the interval between the D-Day landings and Operation Bagration in which the Red Army crushed Germany’s position on the Eastern front. There is, mercifully, no equivalent today.

Instead, of the Bretton Woods model, in yesterday’s Foreign Policy article I suggest that a real impulse for action on the part of major financial powers might emerge not from cooperation, or domestic reform, as Gallagher and Kozul-Wright urge, but from great power competition.

Indeed, one might say that we will know whether the narrative of some kind of global competition for financial hegemony is serious, if a concerted response emerges from Europe, the United States or China to the various financial crises around the world.

The looming financial pressure across a large swath of low-income and emerging economies certainly merits a concerted response. In March 2021 Lars Jensen of UNDP published a prescient overview of debt vulnerability. He concluded that

Total debt-service payments at risk (risky-TDS) are estimated at a minimum of $598 billon for the full period covering 2021-2025, of which $311 billion (52%) is owed to private creditors. This year these figures are $130 and $70 billion respectively. For the group of 19 severely vulnerable countries, risky-TDS is $220 billion for the full period and $47 billion this year. LICs account for only 6% ($36.2 billion) of the full period risky-TDS; LMICs account for 49% ($294.1 billion); and UMICs account for 45% ($268.1 billion).

As Marcelleo Estevâo of the World Bank points out, not only is a lot of developing world debt owed to private lenders, thirty percent of poorest country debt is at variable rates (up from 15 percent in 2005) increasing the exposure to Fed rate hikes.

As Ceyla Pazarbasioglu of the IMF and Carmen M. Reinhart of the World Bank point out in an important paper, the debt service burden has been rising ominously.

As they go on to note,

during the period of high global commodity prices and relative prosperity that lasted until about 2014, many emerging market and developing economies looked beyond the Paris Club of official creditors and borrowed heavily from other governments, particularly China. A substantial share of these debts went unrecorded in major databases and remained off the radar of credit-rating firms. External borrowing by state-owned or guaranteed enterprises, which have uneven reporting standards, also escalated. The boom in hidden debts has given way to a rise in unrecorded debt restructuring (Chart 3) and hidden defaults (Horn, Reinhart, and Trebesch, forthcoming). Comparatively little is known about the terms of these debts or their restructuring terms. Historically, opacity derails crisis resolution or, at a minimum, delays it.Restructurings have always started.

Sri Lanka is one place where the mounting pressure of debt has exploded into the open. Sri Lanka is ground zero for the entire narrative of Chinese bare knuckles debt diplomacy. It is of acute interest to India and thus, presumably, to the planners of the Biden administration’s Indopacific strategy. On that score I cannot recommend highly enough The Geometry of Fear in Eurasia co-authored by policytensor (Anusar Farooqui) and Tim Sahay.

Another flashpoint of financial and political tension that has been gaining attention in Tunisia. As James Swanston of Capital Economics comments:

The current account deficit stands at more than 7% of GDP. And while FX reserves have increased in recent years, they are still low and are insufficient to cover the country’s large gross external financing requirement – that is, the sum of the current account deficit and short-term external debts.

Given its modest resources, Tunisia faces a tough repayment schedule through 2026. Its sovereign dollar bonds have seen spreads widening by a brutal 450bp and yields have surged to record highs near 23 percent.

To describe this situation as unsustainable is an understatement.

Around the region there are many oil and gas exporters, Algeria for instance, which are gaining considerable relief from the commodity price boom. But Egypt, like Tunisia, is coming under severe pressure. It has responded by devaluing the pound by 14 percent since the start of the year. Policymakers are gambling that the gain in export competitiveness outweighs the pain induced by rising import costs and surging price inflation. Egypt’s inflation rose to rose to 8.8% y/y in February – the highest in over two years and interest rates were raised to 9.25%. By the end of 2023 Capital economics expects rates to exceed 11 percent.

It is easy to see how tracing the unorthodox new methods to enable India to pay for Russian fertilizer might get the juices of the Fin-Fi exponents flowing, but in discerning the future of shape of the world economy, the response to these impending debt crises in low-income and emerging market economies will be at least as telling. If there is no response by the United States to Sri Lanka’s mounting crisis, why should we take seriously talk of a new era of geo-economic competition? It wasn’t a good start that Sri Lanka was not even invited to the “Summit of Democracies” in December. As Mihir Sharma pointed out at the time, “countries like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka — flawed democracies that are being wooed by the People’s Republic with money and flattery — are precisely the countries you want in the room.”

Likewise, the EU urgently needs to concert its response to the situation in Tunisia. It is a good sign that at the end of March Brussels committed 450 million euros in aid to support the Tunisian budget.

This is not to appeal for some neocolonial burden of stewardship. In neither case can the crisis be “solved” from the outside. And as Youssef Cherif spells out in this Carnegie Brief on the EU’s Tunisia policy, the choices involved are complex and divide the EU members. But insofar as external creditors are involved, the great powers have an indispensable role to play. To pretend to neutrality, as we now like to say, is either naive or cynical.

Chartbook-Unhedged #3: Is a Bull Market in Europe’s Future?

With the war in Ukraine grinding on and the French election heating up, for #3 in the three part exchange between the Chartbook and the FT’s Unhedged newsletters, our minds turned to Europe.

What happens, we asked ourselves, if you put the question of Europe’s future in market terms? Since 1999 Europe’s equity markets have lagged far behind those of the United States. That is a worry for investors. But it also means that the balance of global capitalism has shifted dramatically away from Europe.

As the Economist recently pointed out: “At the start of the 21st century 41 of the world’s 100 most valuable companies were based in Europe (including Britain and Switzerland but excluding Russia and Turkey). Today only 15 are.”

Will the downward trend continue, or might it be reversed?

Over at the FT’s Unhedged I take a skeptical view. Macroeconomics, and lagging technological development aside, I don’t think there are political majorities to be had in Europe for the kind of pro-business policies that would be necessary to unleash a US-style equity boom. Macron’s slide in the French election proves the point. The votes are just not there.

To read my piece and for exclusive access to the Unhedged pages, follow this link.

Meanwhile, in their essay for Chartbook Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu give a rather more upbeat assessment of Europe’s possible future.

It has been a privilege to work with them the last three weeks. I hope we do it again. In the meantime, enjoy!

****

Europe (to run in chartbook)

When markets people like us think about Europe, they tend to think about charts like this, which shows the relative performance of US and European stock indices (we have excluded the global tech giants that have led the US market, to make the comparison more representative):

For decades Wall Street strategists have been looking at charts like this and writing up investor pitches, arguing that the European gap with US markets must close, and next year — whatever that year was — was the year it would start to happen. Investors who acted on these arguments regretted it.

Excluding the big tech stocks, the price/earnings ratios of the S&P 500 and Stoxx 600 have hovered close together over most of the past two decades, differing on average by just 10 per cent. So US equities’ outperformance is not about inflated valuations, but rather about superior earnings growth at US companies. And this, in turn, must in part reflect better fundamentals of the US economy.

Here is total factor productivity growth, showing how peripheral countries have dragged on Europe, while even in northern Europe the gap with the US has persisted:

Europe’s economy has also seemed less nimble than America’s in times of crisis. Despite originating in the US, the 2008 financial crisis hit European output harder, followed by the added growth punch of the sovereign-debt crisis. During the height of the pandemic, startup creation in the US boomed 23 per cent while slowing or contracting across Europe, thanks in part to America’s more generous fiscal support. Pair fragility with weaker core growth and you get charts like this:

Despite the previous false dawns and dashed hopes, there is a case to be made that now is the moment that Europe turns a corner on growth and productivity, driven by two most unlikely catalysts: Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The twin crises have brought forth a unified European fiscal and political response, starting with the EU’s €800bn pandemic recovery investment fund. Already there is discussion among European officials about making the recovery fund permanent, and using the proceeds to meet the challenges revealed by Russia’s aggression. This is paired with recognition by national leaders (even German ones!) that more needs to be invested in the energy transition and in defence.

In sum, the hope is that the twin crises spur public investment in a region that has struggled with weak demand, and that these investments have private-investment multiplier effects which will meaningfully impact productivity in the long run.

Our FT colleague Martin Sandbu (who has forgotten more about Europe’s economy than either of us will ever know) points out that Europe’s strong fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic has led to a strong recovery. “In the pandemic, panic forced European leaders to drop their bad fiscal and monetary habits, and it worked — the danger now is that they backslide.”

Laurence Boone, chief economist at the OECD, told us she sees reason for hope. “What is encouraging is there was this collective response to the war, after the unified response to Covid. It’s not just a one-off.” She sees four targets for a pan-European investment program, some of which could be funded by a central fiscal mechanism: energy transition, food security, digital security, and defence.

She also makes the important point that fiscal policy is only part of the reason that Europe has under-invested and under-grown relative to the US. Attempting fiscal consolidation too early in the recovery from the great financial crisis was a mistake. But there are also non-fiscal issues, notably the fact that Europe is still not really a single market. Capital markets and digital markets regulation remain splintered, for example, which is a heavy drag on productivity. Investment must go hand in hand with unifying regulatory regimes. Researchers have found that membership in the single market boosts trade and turbocharges foreign direct investment, as much as 85 per cent by one estimate. Deeper integration could bring similar benefits.

As Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein argue in their Trade Wars Are Class Wars, Germany’s reliance on foreign demand to absorb its exports has become a broader problem for European growth. Without reliable domestic demand like in America, business profits are exposed to greater competition and external fluctuations in demand. Here, Europe warming up to more government investment looks promising. Less austere budgets have a redistributive effect that could help rebalance Europe toward consumption.

But for all the momentum towards an investing, unified, rebalanced Europe, there is another trend pushing in another direction. Populist nationalism is resurgent as most recently demonstrated by Marine Le Pen’s surge in France’s presidential race. Markets have taken notice. Jonas Goltermann of Capital Economics points out that over the last week, the yield spread between French and German 10-year bonds has widened by 10 basis points. He sums up neatly:

The spread between French (as well as Italian and Spanish) yields and German ones have been widening for several months. As we discussed here, we think that mainly reflects the ECB’s intention to tighten monetary policy and its muddled message around how, and to what extent, it plans to support “periphery” bond markets in future…But over the past few days, the yields of French bonds have risen by more than those of Spanish ones, and almost as much as Italian ones. In previous episodes of ECB-driven spread widening, French yields rose by less…In addition, the share prices of the major French banks have fallen sharply over the past week (and by significantly more than those of other EU banks). So, “Le Pen risk” appears to be making a comeback

Here is his chart of the spread:

Remember it is the wobbly peripheral countries that have dragged on the region’s productivity, and which stand to benefit the most from investment, unity, and reform. Populism would leave them isolated and paying more to make the investments they need.

Inconveniently, the political window for structural change in Europe has opened just as inflation is spiking. Some sort of EU Recovery Fund 2.0 could worsen the problem — or, at the very least, hand opponents of joint European spending a powerful line of argument.

Europe faces non-political headwinds, too. The biggest and most stubborn is its ageing workforce, which puts a cap on domestic demand. That forces the continent’s exporters to seek markets outside Europe, Claus Vistesen of Pantheon Macro told us, likely limiting much economic rebalancing toward domestic consumption.

For these and other reasons, transformation in Europe has always been slow, painful, or both. But greater fiscal union, higher investment and a more balanced economy are the way for Europe to close the gap with the US, and finally reward investors for betting on the continent.The twin crises of pandemic and war have opened the door to substantial change.

April 5, 2022

Ukraine’s War Has Already Changed the World’s Economy

For NATO and the West’s relations with Moscow, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is clearly a historic turning point. The atrocities committed in occupied Ukrainian communities mark a ghastly breach of international law. But does Putin’s war mark a break in the development of the world economy?

Some have gone so far as to speculate that this war might mark a turning point in the history of globalization, on a par with 1914. Conflict and lack of trust, they surmise, will undercut investment and trade and unleash a general retreat from international interdependence. Others see Russia’s efforts to open channels for trade with India and China as harbingers of a new multipolar order.

It is very early to be making such prognoses. So far, the most remarkable thing about the war is, after all, Russia’s military frustration. Given Russia’s performance, it is far from obvious why anyone, even those once counted as Putin’s allies, would want to associate themselves more closely with his regime.

What demands more urgent attention than long-range prognosis is the shock wave that the war has triggered across the world economy, starting with the combatants, the wider region of Eastern and Central Europe, and global energy and food markets. One lasting story of this war could be the way that Europe uses it to launch its next stage of integration.

Read the full article at Foreign Policy

April 3, 2022

Chartbook #107: The future of the dollar – Fin-Fi (finance fiction) and Putin’s war

What is the future of the dollar-based financial order in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Are we entering a new financial and economic regime? Will it be a regime of inflation? How safe are US Treasuries as a vehicle for investment?

A lot of folks are struggling with these questions right now. It has spawned a genre of future-orientated Finance-Fiction all of its own.

When I googled finance fiction, I discovered that since 2008, finance fiction and the finance novel has emerged as respectable genres of literature.

What I mean to refer to in using the terms is the less literary, more speculative variety of writing – by analysts and other authors of non-fiction – about possible future scenarios for the world economy and its financial system. To distinguish this less literary genre let me call it Fin-Fi for short, as in Sci-Fi or Cli(mate)-Fiction.

At the current moment, two lines of questions dominate these narratives.

One is the question of supply chains, which poses profound questions about the relationship between the monetary and the real economy.

The other is geopolitics and the power of the dollar.

With regard to both I am skeptical. My bet is that the current system has huge inertia and is tied down by gigantic network economies.

I discussed Eichengreen et al’s findings about diversification of reserve holdings away from the dollar in Chartbook 106.

I don’t find it convincing to claim that a greater use of Australian dollars or South Korean won in foreign exchange reserves amounts to a watering down of dollar hegemony. All these “alternatives” to the dollar are, in fact, underpinned by dollar swap lines.

In the last issue of Chartbook, I went back and forth with Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu of the FT’s Unhedged over Larry Fink’s comments about the Ukraine war and the end of globalization. I ended up unconvinced that Larry Fink was himself not in earnest. There is such a compulsion to cater to the demand for Fin-Fi right now that in his annual letter Fink could hardly avoid saying something. So he ended up saying something anodyne and incoherent.

Zoltan Pozsar’s writing on the theme, however, is in a different league. If Fin-Fi in the current moment has an H.G. Wells or a Jules Verne, it is Pozsar of Credit Suisse.

If Eichengreen and his co-authors demand attention because of the empirical depth of their work, what entices about Pozsar is his conceptual depth and idiosyncratic style. What sets Pozsar’s musings over the last two months apart is that he starts from a fundamental analysis of how money works.

In his latest must-read note, Pozsar starts with the framework for thinking about money offered by his intellectual mentor, the great Perry Mehrling.

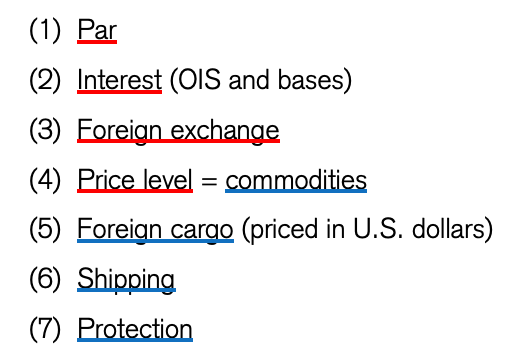

For Mehrling, money can be thought of as being situated in four different relationships, each calibrated by a price.

Par price refers to the price that you pay to exchange different types of money into each other – regular bank deposits for reserve deposits at the central bank, for instance. Claims that in good times are “as good as money”, will, in a crisis be exchangeable into central bank money only at a signifiant discount to par.

The interest rate is the price you pay to exchange money today for money at some other point in the future.

Foreign exchange is the price you pay to swap one currency into another.

The price level is the rate at which money exchanges for actual commodities.

Crises that play out in monetary domains (1), (2) and (3) are obviously within the reach of central banks. The central bank can ensure that assets trade with each other on stable and equal terms. It can manipulate interest rates and, to a degree, exchange rates. It can certainly ensure that markets continue to function for both credit and foreign exchange.

As Pozsar emphasizes, his perspective is that of a bond market analyst, so what concerns him is less whether the central bank can actually fix a particular exchange rate, but whether it has the tools, in a general sense, to intervene in that market and what implications that might have for government bonds. It is up to the market to haggle over particular exchange rates, or interest rate levels. If there are divergent perspectives on the proper price that can be hedged with derivatives of various kinds.

For someone coming from the monetary sphere, the bamboozling thing about the last few years is that central banks clearly do not have all the tools necessary to deal with shocks that originate on the supply side of the sphere of commodities and impact on the price level.

For decades the open secret has been that for all their talk about price stability, the one thing that central banks have not had to worry about is prices. Inflation was tamed. That no longer seems the case.

The problem first reared its ugly head during the COVID crisis and the ensuing supply chain problems. The war now adds the further dimension of national security to supply chain issues. Both factors push in an inflationary direction and they push from the “real side”, from the “supply side”, over which the central bank has precious little influence.

The importance of Pozsar’s latest note is that he expands Merhling’s money framework to explicitly address both the “real side” of the economy and its political frame.

What Pozsar then sets out to do is to map the seismic shocks the world economy is currently experiencing onto this list and to derive from that analysis a story about its likely future development.

To understand the drivers of his narrative we need to dig into his analytical framework a little more deeply.

The items on Pozsar’s seven-point list are conceptually and practically linked.

The real counterpart to the prices that we aggregate as “the price level”, are the commodities to which those prices are attached. Those commodities have an order that is more multi-dimensional than that of prices. Perhaps we ought to call it the “matrix of commodities”.

That matrix is geographically, nationally demarcated. So, the counterpart to foreign exchange is trade in foreign commodities.

The counterpart to the trade-off between money now and money later that defines the rate of interest in Pozsar’s scheme, is the fact that moving commodities from one place to another takes time. So, in our supply-chain-obsessed world, shipping is the counterpart to interest. One of the pleasures of reading Pozsar is to follow him as he loses himself in detail, whether it be bond markets, the plumbing flow of shadow banking, or oil tankers.