K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 30

May 18, 2020

Creativity vs. Distraction: 13 Tips for Writers in the Age of the Internet

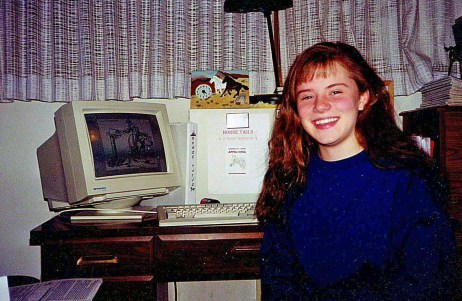

I was twelve when I learned how to use my first hand-me-down computer. It ran Windows for Workgroups and played games like Crystal Caves and Commander Keen. Getting that computer was a life-changing experience. In some ways, it was probably the event that truly fated me to be a writer. Although I had written stories on a typewriter, the computer was a delightful toy that pulled me deeper into the possibilities of word processors and design software. I wrote as much because I liked typing away at the computer as much as I liked the actual writing.

I was twelve when I learned how to use my first hand-me-down computer. It ran Windows for Workgroups and played games like Crystal Caves and Commander Keen. Getting that computer was a life-changing experience. In some ways, it was probably the event that truly fated me to be a writer. Although I had written stories on a typewriter, the computer was a delightful toy that pulled me deeper into the possibilities of word processors and design software. I wrote as much because I liked typing away at the computer as much as I liked the actual writing.

When I was fifteen, my computer got hooked up to the Internet. It was dial-up, which meant only one computer in the house could be connected at a time. It loaded a three-minute video in about three hours. And in absolutely definite ways, it put me in the career path of a writer. The innovations that followed rapidly in the next ten years, not least among them the advent of the Kindle and the self-publishing boom, were timed to allow me opportunities that past generations couldn’t even have imagined.

The Internet has been good to me, in ways large and small. It’s allowed me to make a living doing something I’m passionate about. It’s allowed me the ability to talk to all of you every week and to get to know so many people I never would have encountered in actual life. It’s taught me to be a better writer. It’s allowed me to live in the middle of nowhere and still purchase just about anything I could want from just about anywhere in the world. It’s given me access to the world’s library of books, music, and movies. It’s put a mind-boggling amount of information at my fingertips. It’s plugged me in to a global community of opinions, news, passion, support, and possibilities.

Twenty years after first dialing up the Internet on my clunky old computer, I take for granted how phenomenally this technology has affected my life, as a person and a writer.

Vintage everything. My first computer, sans Internet.

But along with all the blessings have come an equal number of challenges.

If I sometimes take for granted the gifts given by the Internet and its related technologies, I also sometimes take for granted how much its very blessings are also its curses.

If the Internet has given my creativity a voice and a platform, it has also encroached upon the way I create. My fifteen-year-old self could have had no idea how this technology would change her life and the world in the next two decades. She could have no idea how this technology would literally change her, her brain, her very physiology.

In short, if the astounding technologies of our lifetime have given us countless good things, they have also given us… Internet brain. This creates concerns for any human anywhere who uses a screen (and, honestly, for those who don’t too), but as writers we must confront special challenges in protecting and empowering our creativity in this Age of the Internet.

The Unique Challenges for Writers in the Age of the Internet

When I was fifteen and just starting out as a writer, I had no idea I would face challenges much different from those encountered by Charles Dickens (other than, you know, the ink-stained fingers). But in the last half of those two intervening decades, I have found myself putting more and more energy into combating the totally unexpected challenges of the very real ways in which my brain has changed.

Comparative carefreeness of childhood aside, I’ve recognize that as an adult it has become so much more difficult for me to sink into the dream space where the stories live. A lifetime of habits and skills keeps me writing, but it’s not the same as back in the day. And as I’ve been chronicling in the past year or so particularly, I’m not too happy about that.

Despite the fact I’ve always been determined not to let technology run my life, I’m far more addicted to and affected by it than I want to admit. It’s a Catch-22 since, as noted, the Internet is both the blessing and the bane of life as a writer. But I am determined to learn to live in peace, and even true creative productivity, with this omnipresent centrifuge of my life.

To that end, here are fifteen steps I believe are important to help modern writers walk that fine line between being masters of our technology or being mastered by it.

8 Steps to Mitigate Distraction

I recognize that the first, the biggest, and probably the most important task I must accomplish is to reduce the amount of distraction I allow into my life. Without hindering necessary functions, I must learn how to take back ownership of my own brain—and with it my creativity.

1. Turn Off Notifications (and Texts)

Our computers and phones are great at letting us know about things right away. But probably 95% of those “things”—whether notifications from email, social media, text, or even phone calls—are hardly crucial, much less time-sensitive. Every time one of them “pings” into our attention, our concentration is broken. Whether this happens during an actual writing session, or perhaps just a daydream, we’ve lost at least a measure of momentum and continuity.

The Solution: Turn off the notifications and/or log out of sites and apps when you’re not actively using them. If you can’t see/hear them, they can’t control where your attention goes.

2. Never Use More Than One Screen at a Time

These days, we may have the TV on the background while we’re typing on our computers with our phones (or even multiple phones) nearby just in case any notifications come through. This is rarely, if ever, as productive as it seems. It trains us to be ever less present, even as it divides and conquers our limited attention into multiple surface channels rather than encouraging a single deep dive.

The Solution: Make a strict “one screen at a time” rule. If you’re watching TV, watch TV. If you’re using the phone, use the phone. If you’re writing on your computer, write on your computer.

3. Opt Out of Ads When You Can

Part of the problem with #InternetLife is that we have so little control over our experience. We may google an article we need for research, only to be bombarded by half a dozen cookie-enhanced animated ads urging us to stop writing and go buy something. At the very least, our attention is now schismed. One minute we’re thinking about how our character might escape the guillotine—and now we’re thinking that, yeah, that new yoga mat is super cute and maybe we should buy one or at least go look at it because what can it hurt it’s just a second ohwaitIjustwastedtwentyminutesofwritingtime!!!

The Solution: Use AdBlocker where you can (although seems to be growing less effective). Or if you’re able, splurge for the ad-free versions of your favorite sites, apps, and subscription services. The ads seem harmless enough, but it’s shocking how much static they add to our daily lives (not to mention how much time they get us to waste window-shopping and impulse-buying). Of course, when none of the above is possible, you can always opt for not jumping onto the Internet for that quick research check while in the middle of creative time.

4. Resist “Crazy Tabs” in Your Browser

My regular Internet routine of checking email, social media, and other daily necessities (and some not-so-necessities) sees me opening 20-30 tabs in my browser—and then blowing through them as fast as possible. It’s time-effective, and it’s stimulating enough to keep my attention even on the routine boring tasks. But I know it contributes to my Internet brain. How can it not?

The Solution: I admit, I’m still struggling with this one—mostly because I haven’t found an alternative that gets me through my work as quickly. But when possible, I encourage trying not to open more than a handful of tabs at once. In fact, one tab a time would be peachy. Even just having tabs open in the background (I currently have five open—two as reminders to do things later) keeps you from focusing completely on what you’re actually doing. (*goes to close extra tabs*)

5. Categorize Tasks Into Related Groups

One of the problems with “crazy tabs” is that it has your brain jumping all over the place. One minute you’re checking your bank account, the next you’re liking a cat video on Facebook, then you’re trying to understand some heavy-duty article about world economics, then you’re confirming your grocery pickup order—all in the span of five minutes. On the one hand, that’s kind of impressive. On the other—no wonder our brains are fried.

The Solution: Something I’m experimenting with is grouping all my crazy tabs into categories. By grouping all the social media sites together, all the articles-I’m-reading together, all the emails-I’m-answering together—I’m at least giving my brain a chance to settle on one type of task for a longer period of time.

6. Unsubscribe, Unsubscribe, Unsubscribe

It’s just good email hygiene to go through your inbox at least once a year and unsubscribe from anything you don’t read and/or don’t truly benefit from. However, most of us aren’t so great at this. I’m just now doing my first email purge in years, and I’m surprised by how much stuff I receive that I brainlessly delete without reading and/or browse through daily even though I never find anything that actually enhances my life. And yet, even just taking the time to notice and reject/delete an email is a precious bit of attention wasted—over and over again on a daily basis.

The Solution: Clean up your inbox. Delete all the junk so you don’t have to look at it anymore. Put stuff in folders, so it’s organized and you can find it when you want it. And unsubscribe like a crazy person. If you don’t read it, unsubscribe. If it doesn’t enhance your life or encourage you to be a better person in some specific way, unsubscribe.

7. Do One Thing at a Time

Even we’re not on the Internet (but especially when we are), we’re Masters of Multi-Tasking. But studies have shown multi-tasking actually doesn’t make us more productive. We feel busier and therefore more productive. But because our attention is split, we’re not able to dig as deep. Granted, sometimes focusing on one task at a time does mean we get less done. But actually standing there and waiting while the coffee percs, instead of checking email or browsing Pinterest for inspiration, can be exactly the reset time our brains need before we turn our attention to writing.

The Solution: Become conscious of when you’re multi-tasking. Often, we do this without even recognizing it. Or we may even think we’re doing it as part of a useful strategy. For example, when I’m in the midst of a comparatively boring task such as typing up notes, I will “bribe” myself into focusing by hopping over to browse Etsy every ten minutes or so. Yes, it makes the boring job more fun, but is it really helping me be more productive? I think not.

8. Turn Off the Internet, Use Focus-Enhancing Extensions, Set Up Different Machines/Accounts

It’s one thing to decide to limit technology. It’s another thing entirely to resist popping onto the computer to check our email real quick. It’s just five seconds after all. We’re not even going to respond; we just want to see if anything new came in. Or maybe it’s killing us that we can’t name that familiar celebrity we saw in last night’s movie. So we pop on real quick just to remember that oh, yes, that’s who she is. Or maybe our story requires us to know the name of the twenty-sixth Vice President of the United States. So we pop on real quick, and before we know it, we’re thirty pages deep in Wikipedia. (Or… that yoga mat ad got the better of us again…)

Even if we’re true to our self-promise and the visit is, indeed, real quick, we’ve still severed our attention. We have to start all over—and then, when the next urgent need pops in our heads ten minutes later, we have to start all over again and again and again.

The Solution: Sometimes willpower and good habits aren’t enough. Sometimes we have to physically remove ourselves from temptation. When possible, it’s often helpful to create two desk/computers/accounts to help us separate necessary Internet work from our creative work. We can also simply unplug the Internet during writing time. Or we can find an add-on or app that will block our inability to control ourselves. (I’m currently experimenting with Freedom.)

5 Steps to Enhance Creativity

Controlling and cutting down on distraction is the first step in reclaiming our full creative capacity. But from there, we also have to look for ways to nurture the creativity itself.

1. Ground Yourself

Take time every day to return your brain to its full and deep potential. Meditating, doing yoga (as long as you aren’t using it as an excuse to go yoga-mat shopping…), or even taking a walk or a bath can be all it takes to reclaim your brain. You may also need to take it a step further. If your emotions are all over the place, it will be difficult to be fully present to your creativity. You may need to actively work through anxiety and even trauma. This may take time (but in my opinion can totally be counted as creative work).

2. Make Time for Active Imagination

In addition to your writing sessions, try to make time for regular “artist’s dates” (as Julia Cameron calls them). This can take any variety of forms, but one of the most pertinent is focusing on what Carl Jung called “active imagination,” and what I’ve always thought of as “dreamzoning.” In other words, make space and time to just zone out and daydream. Because this is a form of active meditation, it is not the time to let your thoughts wander and think about any old thing. Nor is it necessarily the right time to work through your feelings. It should be a time of “watching the movies in your head.”

3. Become Conscious of Monkey Mind

One minute I’m thinking about writing—then I’m thinking about what I read this morning—then I’m remembering something that happened yesterday—then I’m thinking about my plans for the day—then I’m realizing my thoughts are all over the place. Every time you recognize your thoughts are a train that’s come off the track, focus on bringing yourself back to conscious presence. Just as with the unwanted ads on the Internet, we can learn to discipline our minds to focus primarily on the thoughts that bring the most value into our lives. And I’m not talking about doing this just during meditation. Do it all the time.

4. Concentrate on the Pictures, Rather Than the Words

One thing I’ve realized about the difference between my pre-Internet brain and my post-Internet brain is that my creative thinking used to manifest largely in pictures and now manifests largely in words. Instead of walking through life and seeing stories, now I just talk, talk, talk to myself incessantly. Psychologists say the unconscious has no language; it speaks to us solely through symbols, or images. To me, that says I’m much less in touch with my unconscious creativity than I used to be. So now, in the down moments of my life, I am trying to shut up and see again.

5. Savor Your Beautiful Life

I’ve decided (somewhat belatedly) that my word for this year is savor. I want not just to be present, not just to ground my wandering and distracted brain, but to savor everything around me—whether it’s the golden sun in the green leaves or the cardinals prattling at each other or just putting on my pants in the morning. It’s my life, and I don’t want to miss a second of it.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you struggle with in balancing creativity and distraction these days? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post Creativity vs. Distraction: 13 Tips for Writers in the Age of the Internet appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 11, 2020

Critique: 7 Possible Hooks for Your Opening Chapter

What are some good hooks for your opening chapter? This is a question every writer must ask at the beginning of a story. How can we introduce the story and the characters in a plot-pertinent way that also deeply interests readers?

What are some good hooks for your opening chapter? This is a question every writer must ask at the beginning of a story. How can we introduce the story and the characters in a plot-pertinent way that also deeply interests readers?

A good hook sets your book apart. It promises readers you’re going to deliver something worth their time—whether it’s a familiar genre romp or something they’ve never quite seen before. It signals you know what you’re doing and you’re offering a story that will keep them intrigued on every page.

Although hooks for your opening chapter are often specialized (to the point writers sometimes spend far more time learning how to write a good first chapter than they do the rest of the book), mastering the opening-chapter hook will provide you with the skills to keep hooking readers over and over as the story progresses.

Learning From Each Other: WIP Excerpt Analysis

Today’s post is the eighth in an ongoing series in which I am analyzing the excerpts you have shared with me. My approach to these critiques is a little different from those you normally see on writing blogs. Instead of editing each piece, I’m focusing on one particular lesson that can be drawn from each excerpt, so we can deep-dive into the logic and process of various useful techniques.

Today, my thanks to Stuart Sweet for sharing from his space opera The Santa María. Let’s take a look! The bolded entries and subscript numbers will correspond with the tips I’ll talk about in the subsequent section.

The entirety of the human race gathered before screens of all dimensions.1 Almost no job was too urgent to postpone nor any person too apathetic to hear what was going to be said. The Captain by the name of Charles2 was to address the solar system with a short speech mere hours after revelations of doomsday predictions of an unlikely planet with an impossible threat.3 On the Santa María4, the captain looked up at the camera.

“Dear friends, comrades, colleagues and all assembled members of the human race, speaking to you now is Captain Charles Mendoza Davies of the NSC Santa María en route to the rogue planet known as Deucalion, astronomical designation NSIS 976704-154614, on its hazardous, and indeed precarious, multi-year voyage to ascertain the level of threat that exists, if any, to meet it head on, and to do so on behalf of the human species. As you are all no doubt, well aware by now, current projections place the rogue planet entering our solar system within a few degrees of our ecliptic and within several AU of the planet Earth, with certain models suggesting terrible consequences for the interactions that could follow. Turning now to the question of our chances of success, shared by every mind who listens, I am assured by every authority that the ingenuity and the imagination of the people who have worked so hard on this project are without peer. The novelty of their adopted methods and the passion displayed in exploring every outlandish concept and idea have proved to be an exercise in a bridleless passion to reach out to the space between the stars, beyond our own realm for the first time, and a love for the human race without comparison. I, myself, have the full confidence that the best arrangements have been made, that no precaution has been neglected and that we will fulfill our duties and prove ourselves with the utmost resolve once more, and for many additional years if required, until we have achieved that which we have set out to do. If necessary, we shall defend, to the death, the balance that we Homo Sapiens have established here on our home territory, wherever there is another gram of soil to nurture or another person to call one’s own and to cherish with all of the profound maturity that our species finally has within its grasp.”

Charles paused to take a deep breath and refocus his eyes on the tiny camera on the wall panel before continuing. Although exhausted5, the rest of the room sat enchanted and still, enjoying what they were sure was a sacred moment of history in the making.

“It is my hope that this mission will further inspire us all to put aside our differences and cast away our divisions6 in favour of a united and continued future of interstellar progress. The crew here and myself have all made serious choices and many sacrifices in order to embark on a mission without guarantees on the precipice of the unknown. Now that our collective will has been resolved and asserted, we shall continue on until the very end. We shall prevail, despite the coming storms of adversity for our small boat upon an open expanse of the endless abyss. We shall fight to make scientific discoveries, even if our ship should fly off course and the misfortunes of the oceans beyond the edge of the map prove to be too great.7 We shall fight at every stage of the journey against the challenges that befall us no matter what the personal cost may be. And if the terrible fate should transpire that the majority of this crew were to perish or starve, we shall struggle on until our rescue or until the very end of our existence, accepting that no matter what the outcome, we will have added to our corpus of scientific knowledge and to the great human experience, and that our burial at sea will allow the individual photons of trillions of stars to shine their brilliance upon us, reflecting back into the darkness until the edges of the known universe, forever travelling at the speed of light to places beyond our comprehension, taking our hopes with them, where only our dreams may dare to follow.”

Although these paragraphs hint at a lot of good information and interesting situations, their foundational problem is that the speech comes across as an info dump. This could be problematic anywhere in the book but is particularly hazardous as an opening. Stuart didn’t specify whether this was an excerpt from the first chapter or not. When I first read it, I assumed that it was, and for the purposes of this post I will be treating it as if it is comprises the opening hook. However, even if it is an excerpt pulled from later in the book, many of the same ideas could still be applied.

7 Types of Hooks for Your Opening Chapter (or Anywhere Else in Your Book)

We know a hook is something interesting. It gets readers to at least subconsciously ask an implicit question that piques their curiosity about your story. But beyond simply the idea of a hook as a question, let’s consider several specific types of hook you can use in your own opening chapter. You can use one or all of them, and you can keep using them throughout your book to pull readers’ attention ever deeper into the narrative.

The potential for each of these types of hook is already present in Stuart’s excerpt. By changing the format a little to avoid the info dump and instead focus more attention on dramatizing the characters and their conflict, the inherent promise of these hooks could be amplified to truly grab readers.

1. The “Why” Hook

This is the most basic and most important type of hook. This is the type of hook that immediately prompts readers to engage with the story by asking a question. Why is this happening?

The excerpt opens with a form of this hook: “The entirety of the human race gathered before screens of all dimensions.”

Immediately, readers are prompted to ask “why?” This is helped along by the incongruent specific “the entirety of the human race” (consider how different this hook would be were it simply about one person looking at a screen), which clues readers in on the fact that something is amiss.

2. The “Character” Hook

Your second best hook, which can be used alone but should always follow the “why” hook, is your characters—specifically your protagonist. Except in certain kinds of purposefully distant narratives, it’s best to begin with your protagonist as the first character mentioned and/or as the character whose innate viewpoint immediately reveals any prior information.

Our excerpt opens with what amounts to a head-hop, showing something outside the protagonist’s POV (humanity watching the screens), but it does promptly give readers a named character with whom to identify. It also gives us a Characteristic Moment that implies pertinent facts about this man—although the effect would be much stronger were these facts dramatized in a scene rather than info-dumped in a lengthy monologue.

3. The “Catastrophe” Hook

One of the most popular hooks for your opening chapter is that of the catastrophe. This is technically a “why” hook, but it is focused less on curious incongruities and more on shock and awe.

Usually when writers first learn about the concept of opening a story in medias res—or “in the middle” of things—they think it means opening with a catastrophe. Sometimes this is true, and sometimes it can be extremely effective. However, as Stuart shows, the best approach is usually to open immediately after the catastrophe, so you can dramatize your characters’ reactions. In an opening chapter, when readers don’t yet have a reason to identify with characters, reactions are often better hooks than actions.

4. The “Setting” Hook

Setting, in itself, won’t always be a hook. But by its very specificity, naming a good setting at the outset can often provide readers with coveted details that will draw them into your story world. Sometimes the mention of an interesting setting (such as Stuart’s spaceship the Santa María) is enough to perk reader interest.

Often, readers develop specific predilections for certain kinds of settings, especially those related to genre. But you can also use setting details to hint at more of those curious incongruities—for example, a king in a cell or an orphaned waif at a coming-out ball.

5. The “Contradicting Emotions” Hook

Hinting at anything that seems contradictory is a great way to hook readers. The contradictions must be honest (i.e., not twisted through wordplay to suggest something is out of the ordinary when really it’s not), but used properly they are one of the single best setups for scene conflict.

You can offer these contradictions outright in the scene drama, but you can also choose the subtler but no less effective route of hinting at a character’s contradictory emotions. Stuart does this in the excerpt simply by introducing the word “although” in “although exhausted.” This, again, appears as a head-hop out of the captain’s narrative, but it hints at the interesting events that just happened and how the captain might still be processing them.

6. The “Inherent Problem” Hook

For my money, the single most interesting line in the excerpt is this one: “[I] hope this mission will further inspire us all to put aside our differences and cast away our divisions.”

This line hints at the inherent problems and potential conflict already sown within the fabric of the story. It immediately makes me want to know more about what’s afoot with the crew; it suggests inner conflict that will complicate the external catastrophe with which the characters must contend.

This is one of the best tricks for hooking readers in medias res. It doesn’t require fireworks or lots of action; it just points at relationships and dilemmas that are already in motion and therefore brimming with the promise of subtext.

7. The “Goal” Hook

Finally, one of the foundational principles for hooking readers (and avoiding info dumps) in your opening chapter is promptly establishing forward momentum. Even if you’re focusing on your characters’ reaction to events that have already happened, you should immediately look for ways to get them moving toward the problem’s initial solution and their next scene goal.

Characters sitting around are never as interesting as characters who are wanting, seeking, and doing. This goal doesn’t have to (and probably shouldn’t) be something monumental at this point, but it should be specific. If it is characterizing and curious as well, so much the better.

***

Hooks for your opening chapter are some of the hardest-working elements in your entire story. If you can master them, you’ll not only be able to pull readers into your first chapter, you’ll also be able to reuse the technique to great effect over and over throughout your story.

My thanks to Stuart for sharing his excerpt, and my best wishes for his story’s success. Stay tuned for more analysis posts in the future!

You can find previous excerpt analyses linked below:

5 Ways to Successfully Start a Book With a Dream

How to Use Paragraph Breaks to Guide the Reader’s Experience

8 Quick Tips for Show, Don’t Tell

4 Ways to Write Gripping Internal Narrative

10 Ways to Write Excellent Dialogue

10 Ways to Write a Better First Chapter Using Specific Word Choices

6 Tips for Introducing Characters

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What have you used as hooks for your opening chapter? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post Critique: 7 Possible Hooks for Your Opening Chapter appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 4, 2020

Need a Good Book Editor? Top Up-to-Date Recommendations

Where do I find a good book editor?

Where do I find a good book editor?

This is without doubt the question I receive most frequently from fellow writers. It’s a hard question to answer because, while finding an editor is easy, finding a good book editor is something else again.

I originally published this post a few years ago after asking other writing experts, whose opinions I trust, for their recommendations of freelance book editors. I then suggested readers post their own recommendations in the comments. In the intervening years, the comment section grew tremendously, while a few of the originally published editors went out of business.

So I decided it was high time I update the post.

The following editors are in alphabetical order, with their names linked to their websites, so you can do further research to discover which is best suited to your needs. I’ll continue adding to the list whenever an appropriate new name comes to my attention (you can always find the list on the Start Here! page—accessible from the site’s top toolbar).

If you you’ve personally worked with a good book editor, please feel free to add his or her name and URL in the comments. (If you’re an editor yourself and would like to be included, please ask one of your satisfied clients to nominate you.) The goal is to make this as useful a resource for everyone as possible.

The Top Recommended Freelance Book Editors

Marlene Adelstein

Services: Developmental Editing, Publishing Consultations, Screenplay Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Commercial Fiction, Thriller, Mystery, Women’s Fiction, Literary Fiction, Historical Fiction, Memoir, and Screenplay.

Jennifer Blanchard

Services: Developmental Editing.

Rates: $.03 per word.

Specialties: Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Grace Bridges

Services: Line Editing, Developmental Editing, Proofreading.

Rates: $3–$30 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy.

Averill Buchanan

Services: Development Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Indexing.

Rates: £8–£35 / €12–€45 per 1,000 words or £800–£1,200 / €950–€1,500 per 100,000-word book.

Specialties: Fiction, especially for independent/self-publishing writers.

Kelly Byrd

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Line Editing, Proofreading.

Rates: $12–$27 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Crime and Mystery, Thriller, Romance, Literary Fiction, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Memoir.

Sherry Chamblee

Services: Developmental Editing, Proofreading, Transcription.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Christian Fiction, Christian Non-Fiction, Children’s Fiction, Middle Grade Fiction.

Lauren Chasen

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Evaluation, Non-Fiction Proposal Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Literary Fiction, Young Adult, Upmarket Women’s Fiction, Memoir.

Dario Ciriello

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: 1.25¢–1.5¢ per word.

Specialties: Science Fiction and Fantasy, Mystery and Crime, Romance, Literary Fiction.

Rochelle Deans

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Query Editing, Academic Editing, Non-Fiction Editing.

Rates: Varies by word, 1,000 words, hour, or project.

Specialties: Plot structure.

Harry DeWulf

Services: Developmental Editing, Story Consultation, Editorial Assessment.

Rates: $3,000–$5,000 for full novel edit.

Specialties: Unspecified, but seems to lean toward Science Fiction and Fantasy.

Christy Distler

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Critique.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified, but seems to lean toward Christian Fiction.

Jill Domschot

Services: Developmental Editing, Proofreading.

Rates: ½¢–1¢ per word.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy, Mystery, Romance, Literary, Poetry, Non-Fiction.

Joshua Essoe

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Genre Fiction, Fantasy, Science Fiction, Horror.

Elizabeth Evans

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Assessment, Proposal Crafting and Editing, Ghostwriting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Lorna Fergusson

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Appraisals.

Rates: £275–£1280, depending on service and length of project (could be more).

Specialties: Unspecified.

Savannah Gilbo

Services: Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $497-$1,497 depending on length.

Specialties: Story Grid.

Dori Harrell

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: $2 per page–$2,800 per 100,000 words (depending on service).

Specialties: Novel, Novella, Non-Fiction, Children’s Fiction, Memoir, Short Story, Website Content, Newsletter.

Jon Hudspith

Services: Developmental Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Novel, Novella, Short Story, Flash Fiction.

Caroline Kaiser

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Line Editing, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Mystery, Thriller, Historical Fiction, Children’s Fiction, Young Adult, Fantasy, Science Fiction.

Nicole Klungle

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $2–$3 per standard page.

Specialties: History, Humor, Writing Instruction, Memoir, Literary Fiction, Paranormal Romance.

Mary Kole

Services: Developmental Editing, Coaching, Outline Evaluation, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $199–$3,999.

Specialties: Children’s Literature.

Ann Kroeker

Services: Coaching.

Rates: $125–$1,025.

Specialties: Unspecified.

C.S. Lakin

Services: Developmental Editing, Proofreading, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction.

Steve Mathisen

Services: Developmental Editing Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: $1.75–$5.75 per page.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Katie McCoach

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $300–$3,200.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy, Dystopian, Romance.

Leslie McKee

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Romance.

Andrea Merrell

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Mentoring.

Rates: $30–$40 per hour.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Christian Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Victoria Mixon

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Synopsis Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Novel, Short Story, Narrative Non-Fiction, Memoir.

Ginger Moran

Services: Developmental Editing, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction.

Roz Morris

Services: Developmental Editing.

Rates: £60 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Fiction, Memoir, Non-Fiction

Robin Patchen

Services: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $2–$7 per page.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Christian Fiction.

Anastasia Poirier

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: 1¢–3¢ per word.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Arlene Prunkl

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Indexing, Fact Checking.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Lauren I. Pruiz

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: 1¢–8¢ per word.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Bryan Thomas Schmidt

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Ghostwriting, Short Story Review.

Rates: $30-$50 per hour.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Crystal Watanabe

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Lara Willard

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Ben Wolf

Services: Developmental Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Linda Yezak

Services: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $30 per hour.

Specialties: Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Ginny Ytrrup

Services: Developmental Editing, Coaching.

Rates: $8–$18 per page.

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Web Content, Devotional, Query or Cover Letter, Book Proposal, Fiction Synopsis.

***

In today’s market, getting feedback from a skilled editor is crucial—especially if you’re planning to publish independently. If you’ve yet to find a good book editor, start with the names here and get ready to transform your story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever worked with a good book editor? Can you add to the recommendations here? Tell me in the comments!

The post Need a Good Book Editor? Top Up-to-Date Recommendations appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 27, 2020

15 Productive Tasks You Can Still Do Even When You Don’t Feel Like Writing

Don’t feel like writing right now? Or maybe you don’t have the time? Or maybe you’re just blocked as all get out at the moment? Whatever the case, there’s no reason you can’t still use what time and motivation you do have to feel productive about your writing—because “writing” is really about a whole lot more than just the writing.

Don’t feel like writing right now? Or maybe you don’t have the time? Or maybe you’re just blocked as all get out at the moment? Whatever the case, there’s no reason you can’t still use what time and motivation you do have to feel productive about your writing—because “writing” is really about a whole lot more than just the writing.

I’m often asked if “write everyday” means you actually have to, you know, write every day. What about all the other important tasks you have to accomplish as a writer? What about outlining, researching, note-typing, editing, proofreading, browsing Pinterest, and all that other vital stuff?

First off, everybody’s mileage varies on this. However much writers sometimes want there to be Ten Commandments of How to Be a Writer, there really aren’t. There’s only what works for you and what doesn’t. But for my money, any task that is directly contributing to the creation of a story counts as “writing productivity.” This includes all prep work such as outlining and researching, and all editing work including proofreading. (Personally, I do not include publishing and marketing efforts in this category, since they’re more about product production than story creation.)

This broadening of the definition of “writing” to include all parts of the creation process is, I think, valuable for several reasons.

For starters, it eliminates one of the many possible self-recriminations with which writers like to flagellate themselves. We put so much pressure on ourselves. We tell ourselves we must write so many words a day, so many days a week (and they better be good words), or we’re failures. But realistically, daily productivity is about much more than just high word counts. In fact, sometimes the reason the words won’t come is because we haven’t put in enough time on other parts of the process.

Second, it allows us to better manage our time and energy. Sometimes it’s hard enough to find a solid chunk of writing time every day, much less additional time for the outlining, researching, editing, and Pinterest browsing. This is why I recommend devoting your daily writing session to whichever single part of the process you’re currently working on. If you have two hours a day set aside to work on your book, then you’ll use that time for outlining when you’re in outlining mode, research with you’re in research mode, and writing when you’re in writing mode, etc. This helps you better organize your process, combats the distraction of “monkey mind,” and takes away some of the pressure of thinking you have to “do it all.”

Finally, recognizing the equal validity of necessary “non-writing” tasks can allow you to tap into a powerful feeling of productivity even when you’re not lining up words on the page. This realization can be especially valuable in times when you don’t feel like writing, for whatever reason—as many people don’t in these ongoing weeks and months of quarantine.

15 Productive Things You Can Still Do When You Don’t Feel Like Writing

I have to admit I haven’t done much fiction writing these last weeks. But I’ve shown up at my desk every single day and moved the needle on my story projects in some way. I may not be tallying record word counts, but I feel good about what I’m doing because a) I enjoy it and b) I know I’m contributing to my ability to write later on when when the time comes.

If you find that you don’t feel like writing right now—or perhaps that you just know there are other things you need to do first in order to be able to write—here’s a list of important writing tasks you may be more in the mood for. Not only can you honor your own energetic needs of the moment, you can do so without slackening your productivity and in a way that still lets you foster a daily habit of showing up at the desk and stewing in your story juices.

1. Journal About Why You’re Personally Blocked

Sometimes there’s a lot to be said for making yourself sit there and stare at the blinking cursor until finally the words come. But sometimes the more productive route is to stop long enough to figure out why the words aren’t coming. If the reason you don’t feel like writing has more to do with life than with the story itself, try devoting at least a couple writing sessions to journaling. See if you can work through your emotions and fears until you get back to a place where you’re happy to be working on your story again.

2. Brainstorm Solutions for Why Your Plot Is Blocked

Conquering Writer’s Block and Summoning Inspiration

If the reason you’re unable to write your characters out of that fix you got them into is because there doesn’t seem to be a way to get them out—you’re probably dealing with good old-fashioned plot block instead. This too can be helped, once again, by journaling. My outlining process basically is journaling—a stream-of-conscious conversation with myself on the page about whatever’s not working. If I get really stuck in the middle of a story, I’ll return to this same process—sometimes by typing in a new doc on my computer, sometimes by returning to pen and notebook.

3. Create Something Else (a Story or Not)

Maybe you’re currently stuck because the story in front of you isn’t the right story for this moment. If you’re an obsessive “finisher” like me, switching horses midstream can be tricky, but sometimes a change can make all the difference. Moving on to a new novel or perhaps a short story or poem—or even a new medium, such as painting or crafting—will help you return to a feeling of productivity. You never know—it might be just the ticket for giving you a new perspective on the old story as well.

4. Read About Writing

For most of us reading is so pleasurable it almost feels like a cheat. But it can be so productive. You may be blocked because you’re lacking specific information you need to find in a writing guide. Or you may have a backlogged TBR pile of writing books full of inspiration and motivation you didn’t even know you were lacking (this happened to me a few years ago). If the actual writing just isn’t happening for you right now, give yourself wholehearted permission to use your writing time to read about writing. This time will not be wasted.

5. Read Your Research Pile

By the same token, you may have a pile of research books waiting for your attention—or maybe just a list of research questions you know you have to figure out how to answer. Whenever I’m in research mode, I joke that I get to sit around reading all day and call it work. But it’s true. Many stories can’t move forward until you’ve learned a great deal. When the words won’t come, make use of someone else’s.

6. Learn About and Apply New Story Theory Systems

There’s always more to learn. Whether it’s the principles of story structure, the foundational elements of character arc, a specific system taught by writing guru, or a new theory all your own, you can vastly advance your storytelling abilities by mastering a new perspective on story itself. This is how I’ve been spending much of my writing time during the quarantine—working through ideas about a progressive system of archetypal character arcs, which will contribute to a future blog series and will also, hopefully, help me move forward with my own novel-in-progress.

7. Devote Some Time to Prep Work (Even if You’re in the Middle of Your Novel)

Sometimes we get this idea that the only “real writing” is the writing we do in the first draft and beyond. But outlining is totally writing. Whether you prefer Roman-numeral outlines or stream-of-conscious brainstorming, it’s all story development. Even if you’re halfway into the first draft, you may find that one of the most productive things you can do is return to do some prep work, such as developing your story’s structural beats or double-checking the progression of your characters’ arcs—or maybe just re-working your way through some stubborn plot holes that have cropped up in the first draft.

Returning to prep work can feel like taking a step back, but (I speak from experience) it’s often much more productive to swallow your pride, screech a recalcitrant first draft to a halt, and go back to shore up the entire outline before moving ahead.

8. Interview Your Characters

Although generally considered a part of prep work (for me, a vital part of the outlining process), it’s never a bad time to stop for a chat with your characters. You can do this in a formal way, using a list of questions to make sure you know everything important about your characters. Or you can do it in a more freewheeling fashion, just throwing out questions on the page and seeing how your characters respond. This can be a great (and fun) method when the characters seem as blocked as you do. Asking them about their motivations can be especially revealing.

9. Analyze Your Story’s Scene Structure

If you’re not in the mood to write a new scene, you can feel just as productive (maybe more so!) by stopping to map out the scene structure of your existing (and future) scenes. Proper scene structure asks that each scene offer six specific beats (goal, conflict, outcome, reaction, dilemma, decision), which then lead seamlessly into the next set of beats in the following scene. Analyzing and double-checking your scene structure for weak links in the chain can be game-changing both in terms of tightening your manuscript and even in showing you plot holes and blocks you may not have yet recognized.

10. Type Up Notes

If you’re a slave to your notebook, like I am, then you know the creative power of writing by hand—but you also know the drudgery of having to type up your notes. This is often a chore that gets put off and put off, until you hardly remember what’s in your notes to begin with. But if right-brain creativity just isn’t happening for you, you can make great use of your time by taking care of boring busywork like notekeeping.

11. Organize Your Notes

For many, organizing your notes may go hand in hand with typing them up. But if you have a lot of notes—whether from inspiration, outlining, or research—you no doubt know how easy it is for them to somehow sprawl their way all over your computer. Even the mighty organizational powerhouse Scrivener can quickly turn into a rabbit’s warren of random files and folders. At a certain point my brain explodes, and I have to take the time to consolidate and reorganize notes so I can easily make sense of them when in a more creative frame of mind.

12. Spring Clean Your Story Folders/Computer/Office/House

Technically this doesn’t meet my initial qualification that a productive writing task must directly contribute to the creation of a story. But if you’re one of those people (ahem) who need an orderly environment in order to concentrate, then putting some time into cleaning, tossing, and organizing anything from your Scrivener project to your entire house may turn out to be a very creative use of your time. If nothing else, consider it “creative lollygagging” and use it as daydreaming time.

13. Edit Your Story

There is always more editing that can be done. If you don’t feel like writing, you can always scroll to the top of your document and start reading. Or return to a shelved project and start tweaking. A change of pace can shake up your creativity, and you’ll never regret putting a little more polish on what you’ve already written.

14. Edit for Someone Else

Again, this doesn’t explicitly qualify as productive creative work on your stories. But if you just can’t write anything right now, then offering to read and/or edit another writer’s story will allow you to at least keep yourself in a writerly atmosphere while also doing good for someone else.

15. Dreamzone

Finally, don’t forget that sometimes the most productive thing you can do is… just stare into space. Put on some music, go for a walk, lean back in your chair and close your eyes, build a campfire—and work on your story via mind pictures rather than words for a while.

***

It should go without saying that all these useful tasks can easily turn into procrastination gambits. But it’s vital for authors to be able to take their own temperatures and know the difference between an undisciplined dodging of the daily writing session versus a genuine need to take a break and focus on something else. If you identify with the latter right now, you can use any of the above tasks to stay close to your writing, feel productive, and still honor your need for a little creative rest.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s something productive you try to do when you don’t feel like writing? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 15 Productive Tasks You Can Still Do Even When You Don’t Feel Like Writing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 20, 2020

4 Ways Writing Improves Your Relationship With Yourself

Writing—especially the writing of stories—is ultimately a relationship with oneself. It is true that we write to communicate with others. Perhaps that is even the foremost conscious motivation sometimes. But communication itself necessitates a relationship, and what we are trying to communicate is ourselves—that unfolding inner dialogue between the Self and the self, the observer and the observed, the unconscious and the conscious, the Muse and the Recorder.

Writing—especially the writing of stories—is ultimately a relationship with oneself. It is true that we write to communicate with others. Perhaps that is even the foremost conscious motivation sometimes. But communication itself necessitates a relationship, and what we are trying to communicate is ourselves—that unfolding inner dialogue between the Self and the self, the observer and the observed, the unconscious and the conscious, the Muse and the Recorder.

You must have a relationship with your stories before your readers can, and really this is a relationship with yourself. In recognizing this, writing becomes both an investigative tool for getting to know yourself better and a vast playground for exploration and experimentation on a deeply personal level. Depth psychologist Jean Shinoda Bolen points out:

Creative work comes out of an intense and passionate involvement—almost as if with a lover, as one (the artist) interacts with the “other” to bring something new into being. This “other” may be a painting, a dance form, a musical composition, a sculpture, a poem or a manuscript, a new theory or invention, that for a time is all-absorbing and fascinating.

Particularly in this ongoing period of quarantine and isolation, it can be a tremendously rewarding process to use writing to improve your relationship with yourself. Whether you live alone right now or in a crowded house, the one person you cannot escape, the one person who will always be there for you, is you.

Too often, I think we underestimate this person and our relationship with him or her. We’d rather distract ourselves or hang with someone else because limiting beliefs lead us to think this most intimate of all relationships is too flawed, too painful, too shallow. Isn’t this why writing sometimes scares us so badly we can barely sit at the computer? It is also, I believe, why most of us come to the page in the first place: this person within has something to say and so long as this communication comes out in the form of fun and colorful stories, we are willing to sit still and listen in ways we are rarely willing to offer during the rest of life.

The more we learn to listen to the self that appears on the page, the more we will become conscious of the things we are truly desiring to communicate—both to ourselves and eventually to readers. Writing becomes not just distraction, entertainment, or vocation—it becomes an ever-deepening relationship with life itself.

4 Ways Writing Improves Your Relationship With Yourself

Today, I want to talk about several ways in which our writing reveals itself as a relationship with ourselves—and how we can embrace and deepen our approaches to this magnificent form of self-exploration and self-expression.

1. Dreams, the Shadow, and the Unconscious

How can one not dream while writing? It is the pen which dreams. The blank page gives the right to dream.–Gaston Bachelard

From Where You Dream by Robert Olen Butler

I don’t know about you, but my actual night dreams are all but useless as story material. They’re an evocative smear of rehashed memories and crazy symbolism. My dream journal, although sometimes revealing, is usually more amusing than anything. More easily interpreted are the revelations I discover in my stories. Even more than my actual writing, my ability to consciously enter what I (and Robert Olen Butler) call the “dreamzone” is a mainline to my unconscious.

Your stories are “out loud” dreams. Even though you may exercise nominal control over their subject and direction, the best of them are effortless blasts of imagery and feeling straight up from your depths. Once your body of work is large enough for you to start recognizing patterns and cross-referencing them with the happenings of your own life, you will be able to mine your stories for some of your inner self’s deepest treasures.

It surprises me that more depth psychologists don’t reference and analyze stories in the same way they do dreams. Although I have always known my stories must offer an unwitting commentary about myself, it wasn’t until the last few years that I began to be able to recognize some unintended, occasionally even prescient, parallels between the things I was writing at a given time and the things that were either happening or about to happen in my own life.

More than that, your stories, your characters, and the scenarios and themes you write about are often revelations of the hidden parts of you—your shadow self, or the aspects of your personality you have not yet made conscious. Hidden emotions, desires, and even memories can surface in our writing, there for us to recognize if only we look. Some of our discoveries will be glorious and magical; others will be difficult and painful. But all are instructive.

2. Personal Archetypes and Symbols

Archetypal stories and characters—those that offer universal symbolism—resonate with people everywhere. Whenever you hear of a particularly popular story, you can be pretty sure the reason for its prevalent and enduring success is its archetypal underpinnings. This is a vastly useful bit of information if you want to write a successful story of your own. But it is also useful because an understanding of archetypes and symbolism can offer you a guide to translating you own inner hieroglyphs.

Consider your characters. What types of characters consistently appear in your stories? These are likely archetypes that are deeply personal to, representative of, and perhaps even transformative for you. Just as in dream analysis, it is useful to remember that every character is you. The wounded warrior, the damsel in distress, the sadistic villain—each represents a facet of your psychological landscape.

I’ve long thought we all have just one story to tell which we go on telling over and over in different ways. I’ve also heard it said that all authors have roughly a dozen actors in their playhouse—and we just keep recasting them in new stories. There’s truth to this. Certainly, I can recognize decided archetypes that perennially fascinate me however I try to dress them up in unique costumes from story to story.

As these patterns emerge over time, I get better at recognizing what they represent. Sometimes I am almost embarrassed to realize how much of myself I have bled onto the pages of my novels—secrets so intimate even I didn’t know them at the time I wrote them. Chuck Palahniuk observes aptly:

The act of writing is a way of tricking yourself into revealing something that you would never consciously put into the world. Sometimes I’m shocked by the deeply personal things I’ve put into books without realizing it.

Learning to speak the language of archetype and symbol can grant you tremendously exciting perception into your inner self. Stories that you loved when you wrote them, that meant one precious thing to you at the time of creation, can come to offer all new treasures even years after your first interactions with them.

3. Emotional and Hypothetical Exploration

Writing is also, always and ever, a conscious dialogue with ourselves. We put something onto the page; the page—that is to say, ourselves—responds. And the conversation takes off! Jean Shinoda Bolen again:

The “relationship” dialogue is then between the person and the work, from which something new emerges. For example, observe the process when a painter is engaged with paint and canvas. An absorbed interchange occurs: the artist reacts or is receptive to the creative accidents of paint and brush; she initiates actively with bold stroke, nuance, and color; and then, seeing what happens, she responds. It is an interaction; spontaneity combines with skill. It is an interplay between artist and canvas, and as a result something is created that never before existed.

Although we may not be fully conscious of everything we’re saying about ourselves when we first put a story to words, we almost always begin with some conscious intent. We are writing to experience something—perhaps something we’ve already experienced and want to recreate or relive, or perhaps something hypothetical that we wish to experiment with in a simulated way.

Even outrageous story events, such as fantasy battles or melodramatic love scenes, which we know are impossible or unlikely in reality, can still offer us the ability to symbolically create and process our own emotions. When we are angry, we often write scenes of passionate intensity. When we are stressed, we sometimes write horrifying but cathartic scenes or perhaps loving and comforting scenes.

Sometimes emotion pours out in ways that shock us, and when it does we have the opportunity to follow up and seek the root of something true and honest within ourselves that we perhaps have not fully acknowledged.

It is as if we say to the page: “Joy.” And a scene comes pouring out of us and shows a vivid dreamscape of what joy means to us. Or perhaps we simply wish to present a functional scene in which characters act out gratitude, trauma, love, or grief—and what we discover is our own sometimes stunning emotional response. We speak—and the page speaks back.

4. Logical and Creative Dialogues

I’ve always liked the idea of a dialogue between the left or logical brain and the right or creative brain. Both logic and creativity are wonderful in their unique ways, and both are intrinsic to a full realization of each other.

Of first importance is making sure neither the logical self nor the creative self is overpowering the other. Too often, the creative self is beaten down and starved by a dominant and cruel logic that criticizes every word creativity puts on the page. But creativity can also run wild, like an unruly child with no regard for the advice of its logical parent.

In order to appreciate and cultivate a relationship with both these aspects, we must make sure they respect each other enough to carry on a balanced back-and-forth conversation. This can happen moment by moment when we’re in the throes of writing—our creative minds manifesting ideas and our logical minds putting those ideas to words. But it can also be looked at as a larger dialogue in which different parts of the writing process become the domain of one half of the brain or the other.

I consider the early conception stages—those of imagining, daydreaming, and dreamzoning—to be deeply creative, with very little logical input. Then comes the more conscious brainstorming of outlining, in which I sculpt my dreams and logically work through plot problems. This is followed by writing itself, in which creativity is again brought front and center as I dream my ideas to life on the page. And finally, logic returns to trim the ragged edges during editing.

Understanding how we interact with these two vital halves of personality gives us an edge in honing all parts of our writing. Likewise, in honing our writing, we are given the opportunity to shape these two opposing aspects of ourselves. Very often, one or the other is undervalued or underdeveloped. In learning to respect and appreciate both—and to give both room to properly do their jobs, while maintaining communication with one another—we can refine their presence in our larger lives.

***

In so many ways, writing is the study of the soul. Stories allow us to study the collective soul of humanity. But our stories particularly allow us to study our own souls, to suss out their treasures, relieve their wounds, celebrate their uniqueness, and share their common features.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you think your writing improves your relationship with yourself? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 4 Ways Writing Improves Your Relationship With Yourself appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 13, 2020

How to Get Some Writing Done: Discipline vs. Enthusiasm

Sooner or later, most writers discover that the most difficult part of writing isn’t dreaming up characters or perfecting our sentences or learning story structure. No, the hardest part of getting some writing done is just… doing it. Procrastination is a hot topic (and a self-deprecating joke) among writers for the very reason that almost all of us struggle to maintain the sheer force of will often required in simply putting our fingers to the keyboard and making them move.

Sooner or later, most writers discover that the most difficult part of writing isn’t dreaming up characters or perfecting our sentences or learning story structure. No, the hardest part of getting some writing done is just… doing it. Procrastination is a hot topic (and a self-deprecating joke) among writers for the very reason that almost all of us struggle to maintain the sheer force of will often required in simply putting our fingers to the keyboard and making them move.

One of the best bits of advice I ever received, years ago when I began taking my writing seriously, was to “treat it like a job.” I memorized Peter de Vries great quote and then posted it above my desk for good measure:

I write when I’m inspired, and I see to it that I’m inspired at nine o’clock every morning.

Enthusiasm may have prompted an interest in this approach, but really what we’re talking about is discipline, pure and simple. And yet as important as discipline may be in keeping us at the desk, it isn’t enough. When life gets real, discipline may (or may not) bring us to the desk, but it can’t always make the words flow. A couple weeks ago, @Amira568 tweeted me the following:

I think it’s because writing requires such concentration–it’s almost a meditative state. I suggest starting small–maybe a journal entry or just fifteen minutes at a time.

— K.M. Weiland (@KMWeiland) March 30, 2020

During this COVID-19 quarantine, many people are trying to take the opportunity to learn new skills, further creative desires, and write. New Wordplayer Matthew Zweig wrote me from China:

I wanted to take a moment to thank you for your awesome work, site, free content (ebooks yay!) and advice! Your site has been a source of guidance, inspiration, and knowledge! Thank you!

I’m an ex-pat, living in China, on … day 69(?) of “lockdown” since the COVID19 broke out here in January—and while a lot of folks are struggling with, what I am calling, Stuckhome Syndrome (Stuckhome… Stockholm… get it? Very punny haha) I have been using the time to get stuck into writing and doing a ton of writing prompts and exercises.

I never truly appreciated how intimidating writing can be! I’ve always wanted to be a writer, a novelist—it was only when I sat down to write that it hit home. Writing is scary! Putting your inner thoughts and experiences and stories down on paper and making them “real”… truly scary stuff! But your site has given me structure, calmed me down, pointed me in the right direction. So THANK YOU!

I do hope that you and yours keep safe during this interesting time!

Matthew nailed it. Writing is scary, even at the best of times! While discipline can help us construct structures and systems to help us work through fear and resistance, the discipline will eventually run dry if we’re not also cultivating sheer unadulterated enthusiasm for our work (which I think you can feel radiating from Matthew’s email!).

How to start (and keep) writing even when it’s really hard is an evergreen subject among writers. But it’s particularly pertinent right now, in part because more people than ever are exploring those stories they’ve always wanted to tell. This is a great time to explore our enthusiasm for writing, both because enthusiasm can be harder to access in times of stress and also because enthusiasm is a powerfully positive emotion that, in itself, can bring much good into your life.

Today, let’s look at the subjects of discipline and enthusiasm—and how a proper balance between them will help you get some writing done during the quarantine and after.

Top 5 Tips for Cultivating the Discipline of a Daily Writing Practice

I used to say discipline in writing came down to “willpower, old boy, willpower.” And it does—to an extent. But willpower is a limited resource. If you don’t support it with good habits, it will eventually run out. If you’re consistent in disciplining yourself to show up at the desk for at least a month, your habitual brain will take over and you’ll find you need to employ less and less willpower.

There will still be days (and whole periods) when those habits are challenged by outside circumstances, but showing up at your desk for the 30th day in a row (or, even better, the 6,000th—which is approximately where I’m at after 18+ years of regular writing) is a whole lot easier than showing up sporadically for 30 days spread out over a longer period of time.

Discipline is directly linked to motivation. If your motivation for sitting down to write is strong, then the discipline will follow. By the same token, if you’re struggling with discipline, check your motivation. How bad do you really want to write this story? To be a writer? To have a daily writing practice?

There are no wrong answers. But honesty will either prepare you to better meet your goals—or save you a lot of trouble if it turns out you have different desires.

Assuming you do want to cultivate the habit of discipline in your writing life, here are my top five tips.

1. Build a Writing Session Into Your Daily Schedule

I’ve talked about this in several different posts, but recently in this one: “8 Challenges (and Solutions) When Writing From Home.” If writing is truly going to happen for you on a regular basis, then you must build it into a larger schedule. This schedule must not only make time for your writing, but also support you physically, mentally, and energetically so you have the necessary resources when you do show up at the desk. A good daily writing session, done regularly, is what will build those muscles of habit.

2. Create a Warm-Up Routine

Writing requires deep levels of concentration from both our logical brains and our imaginative brains. It’s difficult to cold-start either. Although you can absolutely train yourself (habits again!) to sit down, switch gears, and start writing like a mad person at the drop of the hat, you’ll probably encounter less inner resistance if you ease into full-blown writing with a few warm-ups. This is a build-your-own-burrito exercise, but tricks I’ve used in the past include:

Journaling about your goals for the writing session.

Brewing coffee and preparing a light snack.

Re-reading what you wrote the day before.

Reviewing research or outline notes.

Watching a thematically appropriate music video.

Wordplayer Eric Troyer commented a few weeks ago that:

I also do 10 minutes of meditation right before starting my morning fiction writing. I found that helps me focus.

3. Be Realistic About Necessary Preparation

One of the biggest reasons writers freeze when they sit down to write is that they’re not actually ready to write. If you find yourself revved up and willing but still unable to get started, you may need any of the following to provide the necessary resources for a full-blown writing session:

Research.

Outline/plot preparation.

Further understanding of story theory and writing techniques.

People often ask if “writing every day” literally means writing. I say, no. For my money, any necessary writing task, including all those mentioned above, counts. When I’m in research phase, I don’t write at all but spend my entire writing session reading and/or transcribing notes.

4. Set the Timer

When you are ready to write, you may find yourself with your fingers hovering over the keyboard: hovering, hovering, hovering. Before you know it, thirty minutes have passed. I’ve found that setting a short time limit, such as fifteen minutes, and then just diving in and writing like crazy will get me going and keep me going. Writing for fifteen minutes doesn’t seem as intimidating as writing for an hour or two. When the fifteen minutes is up, I start another round.

5. If You’re Struggling, Ask Why

Sometimes, no matter how much willpower you’re churning out, the words just won’t come. At this point, you have to ask yourself why. The reason you’re struggling to write almost certainly is not because you’re a lazy bum who lacks discipline. Something’s wrong. Something’s difficult. So be kind to yourself. But also be smart and look deeper. What’s the real hang up here? Maybe you need some time off to care for your physical and emotional health. Or maybe… you’re running low on enthusiasm…

Top 5 Tips for Renewing Your Enthusiasm for Writing

Another recent email, from Colleen Janik, addressed the essential nature of enthusiasm in any act of creativity:

The problem is, really, that people SAY that if you sit in that chair in front of your computer long enough and WRITE, that the Muse will obediently appear….

The truth is, as far as I have experienced, writing is partially a matter of willing the muse to come and pull up a chair next to you, sip tea and chat while you wildly type all the brilliant ideas about all the great characters and conflicts.

The trick, I believe is, to set up a place that is quite comfortable for the Muse and to invite him/her very cordially and wait very patiently for that presence and then don’t EVER EVER EVER rush him/her out the door before the visit is over.

We CANNOT artificially create the magic of writing without the Muse.

The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron

The inimitable Julia Cameron went even farther in her classic The Artist’s Way (which is, in my opinion, the one book every writer should read during this quarantine—as you’ve probably guessed, since I think I’ve talked about it in every single post I’ve written this past month):

Over any extended period of time, being an artist requires enthusiasm more than discipline. Enthusiasm is not an emotional state. It is a spiritual commitment, a loving surrender to our creative process, a loving recognition of all the creativity around us.

Enthusiasm (from the Greek, “filled with God”) is an ongoing energy supply tapped into the flow of life itself. Enthusiasm is grounded in play, not work. Far from being a brain-numbed soldier, our artist is actually our child within, our inner playmate. As with all playmates, it is joy, not duty, that makes for a lasting bond.

True, our artist may rise at dawn to greet the typewriter or easel in the morning stillness. But this event has more to do with a child’s love of secret adventure than with ironclad discipline. What other people may view as discipline is actually a play date that we make with our artist child: “I’ll meet you at 6:00 A.M. and we’ll goof around with that script, painting, sculpture…”

When your enthusiasm is on tap, no one needs to tell you how to find it. It’s just there, an effervescent well of life bubbling up from deep inside. But when it goes missing, it can be difficult to relocate it, and in my experience, the steps usually aren’t directly related to writing. In fact, if you’re really struggling with enthusiasm, whether in general or for writing in particular, you may want to relent on your discipline and give yourself the permission for a break.

If you’re striving to access your enthusiasm, here are a few exercises you can play with to cultivate it (and don’t be mistaken: healing tapped-out enthusiasm requires a discipline all its own).

1. Reconnect With Your Inner Child

I love Cameron’s emphasis that creativity is inherently linked to one’s inner child. There are many things we can do to rediscover this most playful part of ourselves, including some of the following:

Reflect on childhood memories, using photos, home movies, and old journals as aids. Try to remember what it felt like to be enthusiastic and creative when you were young.

Interview your inner child. Just as if he or she were a character in a story, start asking questions and seeing what answers you find. Particularly, ask about things your inner child might be afraid of or areas in which your inner child may not trust you. Visualize what he or she may look like (mine came to me as a wary, feral “wolf girl,” a la Princess Mononoke).