K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 34

September 2, 2019

Creating Your Character’s Inner Conflict: Want vs. Need

Man vs. Self—it’s the most archetypal of all stories. This is because all stories are ultimately rooted in the primal and personal struggle of a character’s inner conflict.

Man vs. Self—it’s the most archetypal of all stories. This is because all stories are ultimately rooted in the primal and personal struggle of a character’s inner conflict.

As individuals, our conflicts with others or the world itself are almost inevitably either reflections or projections of our inner conflicts—our cognitive dissonances, our conflicting wants and needs, sometimes even our conflicting wants and wants or conflicting needs and needs. Finding inner peace is ultimately about working through the chatter of the many competing voices in our heads (some of them accurate, all of them passionate) on our way toward understanding the following:

What each voice is saying.

What underlying motivation each voice is representing.

Which motives and desires are healthy and which are not.

How to harmonize those that are healthy but still seem competitive.

Letting go of some desires in favor of others.

Coming to peace with all choices.

Moving forward in holistic action based on those choices.

As I’m writing that list, it all sounds pretty lofty and serene. (I keep hearing Shifu from Kung-Fu Panda: “Inner peace… inner peace… inner pea— Would you please quiet down!”) But actually what that list describes is nothing more or less than the (positive) arc of a character over the course of a story.

In a story, that internal progression may be the forefront preoccupation of the author and the character. But more likely, the internal conflict is happening behind the scenes and under the surface of the external plot—which, as we’ve talked about before, can often be thought of as an external metaphor for the internal conflict. The external plot is the reflection/projection of the character’s inner struggle upon the external world.

Today, I want to take a closer look at that inner struggle. In discussions of character arc and theme, I’ve talked a lot about how a character’s inner conflict is framed around the dichotomous struggle between the Thing the Character Wants (which is Lie-based) and the Thing the Character Needs (which is Truth-based).

Although this black-and-white dichotomy is helpful for an at-a-glance understanding of the character’s inner conflict dynamics, we can find greater nuance by looking a little deeper at what is actually going on inside your character.

The Thing Your Character Wants: What Is It Really?

At its simplest, the Thing Your Characters Wants is the plot goal. Usually, the Want is part of a bigger picture—a desire or goal that existed prior to the specific conflict of your story’s Second Act—but it will funnel directly into your character’s plot goal.

Luke Skywalker’s Want is to escape his lonely orphaned adolescence and find a life of meaning and purpose in the larger galaxy. In the first movie, this translates to the specifically-iterated goal of wanting to “learn the ways of the Force and become a Jedi like my father”—a desire that progresses throughout the trilogy and frames his entire arc.

In any kind of Change Arc, the Want shows the Lie the Character Believes in action. The Want itself may not be a bad thing (more on that in a bit), but even if it is positive in itself, it represents a negative mindset or motivation. Within the character’s inner life, the Lie has created either a hole or a block. It is preventing the character from growing toward health; it may even be actively pushing him toward mental or moral sickness.

>>Click here to read about all the different types of character arc.

At the root of the Lie and its ambiguous motivations is a Ghost from the character’s past—something that created that hole or that block.

Luke Skywalker’s Ghost is his orphanhood, particularly the absence of his seemingly heroic father.

Luke Skywalker’s Lie is that to fill this inner hole and be worthy, he must be just like that father. This false belief fuels his impatience and reckless desire for adventure and glory.

Because the Lie and the Want are linked (as are the Need and the Truth—see below), the obvious implication is that the Want is bad.

Sometimes this is true. Sometimes what a character wants is blatantly destructive and evil. However, even in these situations, it’s important to note that the character will rarely see it so clearly. He wouldn’t pursue the Want if he didn’t believe, on some level, that it was worthy, that the end justified the means. As T.S. Eliot so chillingly noted:

Most of the evil in this world is done by people with good intentions.

At the very least, the character may believe that a “bad” Want at least represents the best possible outcome (as, for instance, when a woman believes she’s safer staying in an abusive relationship rather than leaving).

However, even more often, the Want won’t, in itself, be a bad thing. In fact, the Lie and its resultant motivation may not be obviously destructive either. After all, the reason the character believes in the Lie and wants the Want is because he thinks it will make his life better. Rather than recognizing his misconception of reality as part of the problem, he sees it as the answer.

This delusion is only possible if the character himself is either utterly deluded or if he’s caught between two conflicting choices, both of which bring their own benefits and consequences. In the case of the abused woman needing to leave her destructive relationship, there will be good things and bad things about either of her choices—which is why the struggle to choose may be waged down to the very bottom of her soul before it can be completely manifested in her external conflict.

Luke Skywalker’s Want and plot goal aren’t quantifiably bad or destructive. On the surface, all of his Wants and plot goals are actually quite healthy: wanting to become a Jedi, wanting to join the righteous Rebellion and fight the evil Empire, and wanting to move into a more meaningful life in a broader context.

Don’t get confused by the terminology. The “Want,” as a technical term within the theory of character arc, specifically references a plot-advancing desire that doesn’t (yet) represent a wholly integrated or holistic mindset. But just because the character currently wants the wrong thing or wants it for the wrong reason doesn’t mean that thing isn’t also something he does in fact need. The Ghost almost always represents a deep gaping need, and the character’s initial attempts to fulfill that need are rarely 100% misguided.

The Thing Your Character Needs: What Is It Really?

Whereas the Want is a direct equivalent of the plot goal, the Thing the Character Needs is a direct correlative of the thematic value. Whatever Truth your story is positing about reality, that is the ultimate Thing the Character Needs.

Luke Skywalker’s Need is to overcome the fear and anger that tempt him into darkness. He Needs to give up his hubristic desire to fight his way to glory as a means of protecting those he loves. What he learns over the course of the trilogy is that being a Jedi has nothing to do with being “like my father.” (Indeed, his father must learn to be more like Luke.) Even more than just that, being a Jedi is about surrendering the need for glory, accomplishment, or even control. He learns these Truths slowly, over the course of the series, climaxing in the moment when he refuses to give in to his hate and throws away his lightsaber.

The Need is always available—an often simplistic antidote to the character’s inner pain and conflict. But the character is confused, usually because the Want realistically seems to offer the correct solution to her problem. Just as often, the character may either push away from the Need or embrace it only halfway because she can’t gain the Need without also accepting significant consequences (for instance, in leaving an abusive relationship, a woman might have to leave behind much more than just the abuse—not to mention facing punitive reactions from the abuser).

And yet, no matter how difficult or Pyrrhic it might be to pursue and accept the Need, the character will never find health or wholeness without it. Ultimately, what the Need/Truth represents is a resolution of the inner conflict. Embracing the Truth shows the character which of the competing voices in her head is right. With this rightness—with Truth—comes a realignment with reality. When that happens, the character may have to face difficult consequences, but she will instantly be freed from the tremendous burden of fighting against reality itself.

Luke Skywalker’s Need is to let go of his fear, anger, and hatred. But in choosing to do so, he consciously puts at risk his own life, those of his family and friends, and even the success of the Rebellion. As it turns out, his story ends positively, since his choice catalyzes his father’s subsequent decision to destroy the Emperor and save his son. However, in a story with a Disillusionment Arc, the choice to embrace the Need and the Truth might, in fact, end negatively with the character facing the full consequences of the choice (e.g., Han and Leia die and the Rebellion fails).

Just as the Want is not always quantifiably “bad,” the Need is also not quantifiably “good” in the sense that choosing it means everything is suddenly sunshine and roses. If embracing the Need were that simplistic, the character would have no reason not to choose it outright at the beginning of the story.

The only reason any of us obstruct our own progression toward health is because pursuing health is hard. Anyone who chooses to lose weight for health reasons can attest to this. Even knowing your excess weight might someday threaten you with heart disease or diabetes does not mean the daily grueling sacrifices of exercising and eating right are easy choices. This is true even when your bad choices have direct consequences. Maybe you know eating that donut is going to make you feel crummy about five minutes from now. But saying no to all that yumminess is super-hard, so you eat it anyway.

The same goes for healthy mental and spiritual choices. Doing the right thing doesn’t always get you a pat on the back; sometimes it gets you crucified—metaphorically and even literally. Choosing to recognize truths about yourself and the world around you doesn’t always make life easier; sometimes it rips off the Band-Aid and makes your psychic wounds start bleeding all over again.

That said, the Need always represents the path toward health and recovery. A nuanced presentation of the Need will accurately portray all the reasons the character doesn’t embrace it outright. But this does not always mean the character might not also actively want the Need. For instance, anyone who is overweight (and lots of people who aren’t) want to lose pounds. They probably even know they need to lose pounds.

This is where some of the most powerful of a character’s inner conflict comes into play. A conflict between something a character Wants and something she does not (even if she Needs it) can be powerful and compelling. But usually, an even more compelling scenario is that in which the character internally struggles between two competing wants—or even two competing needs.

She can’t have both. She can only have one. In these cases, the true Need (in its technical, character-arc definition) will be the one that serves the greater good. For example, the character might Want to be with her true love. Nothing wrong with that. Indeed, the relationship may represent everything that is good about her. It promises nothing but health and happiness for the future.

But the character also Needs to do the right thing. For example, she has to make the big sacrifice and save the world because only she can do what must be done. Or, on a smaller scale, maybe doing the right thing means staying faithful to her marriage vows and making sure her children grow up in a stable family environment. If she were to choose the good Want over the better Need, she isn’t the only one who will suffer. And she will suffer. Choosing a Lie over a Truth is always a recipe for suffering, even if the consequences are delayed.

***

Why is all of this important? It’s important because as you’re planning your character’s arc and trying to identify the Want, Need, Lie, and Truth, it can be confusing (and limiting) when you feel you have to make the Want and the Lie obviously “bad” and the Need and the Truth obviously “good.” Even a good-vs.-evil conflict as obvious as Star Wars offers a nuanced view of why a character might simultaneously need the Want and want the Need.

Don’t get too caught up in the terminology. Ultimately, a character’s inner conflict is always between two things the character wants on at least some level. This is, in turn, mirrored in the outer conflict, which also represents want vs. want—the protagonist’s plot goal vs. the antagonist’s plot goal.

The more nuanced your approach to the dichotomies of Want vs. Need and Lie vs. Truth, the more nuanced your thematic discussion and your presentation of plot and character will always be.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What Want and Need represent your character’s inner conflict? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/inner-conflict.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Creating Your Character’s Inner Conflict: Want vs. Need appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 26, 2019

How to Use a “Truth Chart” to Figure Out Your Character’s Arc

“How do I figure out my character’s arc?”

“How do I figure out my character’s arc?”

This is a question I receive commonly—and with good reason. Not only is your character’s arc central to all your other story choices—plot and theme foremost among them—character arc can also seem like one of the most daunting parts of story. Mostly this is because of its very integrality. In so many ways, your character’s arc is your story.

As we’ve discussed lately, character arc is particularly essential to your development of theme. If you don’t develop your theme and your protagonist’s character arc as two halves of the same whole, the story is likely to feel inorganic. Central to this relationship is your main thematic Truth, along with the character-specific Lie obstructing your character(s) from benefiting from a more realistic and holistic perspective.

Over the years, I’ve created quite a few resources for helping authors (me too!) understand how to organically evolve a character’s understanding (or misunderstanding) of a story’s central thematic Truth. My blog series and book Creating Character Arcs offer an act-by-act, plot-point-by-plot-point examination of the relationship between character arc and plot structure. If you’re new to the idea of consciously constructing your character’s arc, I definitely recommend starting there for a big-picture view of the subject.

Today, I want to share a new tool, one I’ve refined for my own use while writing the sequels to my portal fantasy Dreamlander. I’m calling this tool a “Truth Chart.” It’s a fast, one-page beat sheet designed to help you get your head around the big picture of theme and character, so you can see at a glance if everything is holding together and progressing realistically.

Thematic Truths (and, to a lesser extent, Lies) often seem unwieldy in their abstract vastness (for example, the thematic Truth underlying your story may be something as titanic as Love). Because these universal subjects can be accurately expressed in so many ways, they’re often difficult to pin down. Over the course of your story, you may find yourself expressing the same core Truth in a dozen different ways. When trying to create a thematically cohesive story, the abstract nature of the subjects with which you’re dealing can often be bewildering. After all, we all want complex thematic premises, right?

Several years after writing my book Creating Character Arcs, I decided I needed a standalone post that addressed the Truth, so I wrote this one, using Marvel’s Black Panther as an example of how the thematic Truth can be developed act by act. While in the middle of outlining the (still-untitled) third book in my Dreamlander trilogy, I found myself referring to this post over and over again to help me ensure my plot and character arc were thematically sound at every beat. Somewhere along the road, this practice turned into a exercise all its own—the Truth Chart.

What Does a Truth Chart Look Like?

In a minute, we’ll define each of the specific parts of the Truth Chart, but first off, here’s what it looks like:

Story’s Big Truth (Main Theme):

Story’s Big Lie:

Character’s Specific Truth:

Character’s Specific Lie:

The Thing the Character Wants:

The Thing the Character Needs:

Ghost:

1st Act—Specific Manifestation of the “Big Lie”:

1st Act—The Story’s “Small” Introductory Truth:

2nd Act —An Aspect of the Truth Acting as an Antidote to the Specific Lie (Moment of Truth):

3rd Act—Remaining “Biggest” Chunk of the Lie:

3rd Act—Climactic Truth:

Building Your Thematic Truth Chart—Line by Line

For the entire picture of what each of these elements are and how they should interact with your story, you’ll want to check out both Creating Character Arcs and the previously-mentioned post “How the Truth Your Character Believes Defines Your Theme.” For now, here’s a quick overview of each piece.

Story’s Big Truth (Main Theme): This will be your story’s thematic premise. It should be a universal principle (e.g., “hope gives people a reason to go on living”) rather than your character’s specific Truth (e.g., “hope will help you survive and escape an unjust prison sentence”). It’s also best if you can create an intentional statement, rather than just a single-word principle (e.g., “Hope”).

Story’s Big Lie: This is the Big Lie standing in opposition to the Big Truth. Like the Big Truth, it is a generalized version of the specific Lie the Character Believes. This is the Lie that will affect every part of your story, including supporting characters, the world around the protagonist, and the antagonistic force.

Character’s Specific Truth: This your character’s specific version of the Truth, as found in the circumstances of this specific story. Many stories offer a “Big Truth” about “Redemptive Love,” but the manifestation of your story’s specific Truth can be as vastly different as Jane Eyre is from Logan.

Character’s Specific Lie: I positioned the Big Truth (and Big Lie) at the top of the chart because that Truth is your story’s defining principle. However, your creative process will more likely discover your story’s thematic premise via a specific Lie the Character Believes. This Lie is at the root of the plot problems. The character believes something about himself or the world that is untrue—and his lack of understanding will create consistent obstacles (aka, conflict) between him and his ultimate plot goal.

The Thing the Character Wants: Although often representative of a larger, more abstract desire (e.g., “to be loved”), the Thing the Character Wants will manifest specifically in her plot goal. Often, the Thing the Character Wants is at least partially misguided, based on the character’s mistaken (Lie-based) reasons for wanting it or methods for gaining it.

The Thing the Character Needs: The Thing the Character Needs is ultimately an understanding of the Truth. Usually, the Need will also be represented by a more concrete and specific outer-world objective. Sometimes the character will run away from the Need in the beginning, but in many stories, he may consciously “want” the Need, which exacerbates the inner conflict between his Lie-based Want and the Truth-based Need.

Ghost: The Ghost (sometimes referred to as the Wound) is a motivating event in your character’s past, which represents the moment and the reason the Lie first took root in her life. Often the Ghost is a traumatic event (e.g., the death of one’s parents), but it can also be a “good” occurrence (e.g., receiving too much praise for a specific accomplishment) that led to a misunderstanding about life.

1st Act—Specific Manifestation of the “Big Lie”: In the First Act, the story’s Big Lie will initially manifest in a specific message that is either urging the protagonist toward the Want and/or presenting a direct obstacle to the protagonist’s ability to move forward toward the Need and/or the Want. It is usually a mindset or belief presented by the Normal World around the protagonist (even in most Negative-Change Arcs). The character will likely take this manifestation of the Lie for granted without questioning it much, if at all.

1st Act—The Story’s “Small” Introductory Truth: Although the protagonist will spend most of the First Act in a comparative state of tranquility in which the Truth does not proactively contradict the Lie, the Truth will still be present via a “small” introductory version of the story’s larger thematic premise. This will often be the thinnest edge of the spear, the first tiny prick of Truth that begins to slowly wedge open a Change-Arc character’s awareness of the Lie (which, in a Negative-Change Arc, will prompt still greater resistance to the Truth).

2nd Act—An Aspect of the Truth Acting as an Antidote to the Specific Lie (Moment of Truth): After the setup of the First Act, the Second Act will represent the protagonist’s full-on immersion into the conflict—and, as an extension, her full-on immersion in her inner conflict between Lie and Truth. Throughout the First Half of the Second Act, events will conspire to grant her a growing (if often unconscious) awareness of the Truth.

This finally manifests in the external conflict at the Midpoint, when the character experiences a Moment of Truth. How the character reacts to this revelation will depend on what type of arc she is following. Regardless, the Truth she finds here will not be the complete Big Truth. Rather, it will be a “halfway” Truth of sorts. In order for this thematic revelation to flow properly with the external plot development, the Moment of Truth should be framed as an “antidote” to the specific Lie the character believed in the First Act.

Throughout the subsequent Second Half of the Second Act, the character will not fully reject the entire Lie (or embrace the entire Truth), but the Lie and Truth in which she believes are now modified versions of those with which she started out in the First Act.

3rd Act—Remaining “Biggest” Chunk of the Lie: The Third Act can be a tricky time for character arcs. The character needs to have completed most of his growth by this point, but the biggest revelations should remain in order for the Third Act to feel properly climactic. This is why it’s important to retain the “biggest” chunk of the Lie for the character to confront in the Third Act. By this point, the character will have embraced most of the Truth. But there’s a big mote still in his eye. There’s still a crucial bit of Lie that he (or the world around him) hasn’t seen past. This will be the Lie’s final “argument” within the story.

3rd Act—Climactic Truth: Combating the Third Act’s “big chunk of Lie” will be the climactic version of your story’s Truth. In essence, this will be the Big Truth of your thematic premise (see above). But it’s helpful to refine that Big Truth into the very specific Truth needed to resolve your story’s main conflict. You can see various ways in which your character will interact with this final Truth, depending on what type of arc she is demonstrating.

How to Find the Right Answers for a Character Arc

You almost certainly will not (should not) fill in the blanks on this Truth Chart right at the beginning your story-creation process. Discovering the proper Truth, Lie, theme, and character arc(s) for your story will be an organic process. You won’t know the right answers until you first (and simultaneously) have accumulated enough knowledge about your story’s plot and your characters’ journeys within that plot.

To work well, your story’s thematic Truths must emerge organically from every other mechanical piece within the overall structure. Once you’re far enough along to know the general shape of your story, you can start looking for its emergent Truths.

Consider what questions your story is asking. Some thematic questions I recognized in my WIP included:

Why am I here?

Who am I supposed to be?

What is my destiny in this life?

What is my responsibility in this life?

What is Life’s narrative?

Just talk to yourself on the page. What themes do you see emerging? What themes do you want to explore in this story? Start trying to sum up the theme in a single Truth. You may find several. Keep going, keep refining. Always check yourself against the Truth that emerges in the Climax. How does that Truth tie in within the characters’ struggles and misconceptions earlier in the story?

Eventually, you should come up with the single best option for summing up your story’s Truth. Hang on to all the other Truths you may have written down, because some of them may turn out to the be the “smaller” Truths your character has to work through in the First and Second Acts, on his way to overcoming the Big Lie and accepting the Big Truth in the Climax.

Truth Chart Examples From My Dreamlander Series

To help you see what the Truth Chart looks like in action, here are examples from my outline for Book 3 in the Dreamlander trilogy. (For those of you interested in the series, I suppose this might be a little spoiler-y, but only on an abstract level. Plus, the book won’t be out for several years, so you’ll probably forget all about this in the meantime. :p )

I’m including two different versions of the Chart. The first is for the protagonist and therefore represents the story’s main theme. The second is for the most prominent supporting character. You’ll see how her chart riffs off the main Lie/Truth but explores some ancillary angles.

***

Story’s Big Truth (Main Theme): What you do matters (and you know what to do).

Story’s Big Lie: Destiny is a lie; your life has no narrative, no meaning.

Protagonist/Main Theme Truth Chart

Character’s Specific Truth: Responsibility to my truth is my greatest destiny.

Character’s Specific Lie: I am not destined to to save the worlds; my actions are all random and some are mistakes.

The Thing the Character Wants: To save the worlds—and live happily ever after with Allara.

The Thing the Character Needs: To live a meaningful life.

Ghost: The apocalyptic consequences of his mistakes.

1st Act—Specific Manifestation of the “Big Lie”: There’s no guarantee my actions will turn out for the good.

1st Act—The Story’s “Small” Introductory Truth: I can’t give up; I have to act.

2nd Act—An Aspect of the Truth Acting as an Antidote to the Specific Lie (Moment of Truth): What I do matters because only I have the abilities, as Gifted, to do what must be done.

3rd Act—Remaining “Biggest” Chunk of the Lie: Either Destiny is a set narrative, or life is meaningless.

3rd Act—Climactic Truth: Destiny is inscrutable but still accessible if I am willing, no matter the cost, to listen to my inner truth.

Supporting Character/Subplot Truth Chart

Character’s Specific Truth: My destiny is bigger than my understanding of a narrative.

Character’s Specific Lie: The narrative is true, so it must be just me messing it up.

The Thing the Character Wants: To fulfill her narrated destiny.

The Thing the Character Needs: To surrender into the faith and freedom of a larger, more complex acceptance of reality and her place in it.

Ghost: Realizing the narrative she had believed in, regarding her destiny as a Searcher, was not what she always believed.

1st Act—Specific Manifestation of the “Big Lie”: My destiny is found in my identity: Queen of Lael and Searcher.

1st Act—The Story’s “Small” Introductory Truth: I must stop denying the truth about reality and my place in it.

2nd Act—An Aspect of the Truth Acting as an Antidote to the Specific Lie (Moment of Truth): If I want to fulfill my destiny, I must give up my stubborn grip on my own identity and my own limited narrative.

3rd Act—Remaining “Biggest” Chunk of the Lie: To fulfill my destiny, I must understand it.

3rd Act—Climactic Truth: The only thing I can do that matters is act in faith.

***

I hope you’ll find this Truth Chart as useful a tool as I already am. Go forth and write powerful themes!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What thematic Truth are you exploring in your story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/truth-chart.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Use a “Truth Chart” to Figure Out Your Character’s Arc appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 19, 2019

How to Tell if Your Story Has Too Much Plot, Not Enough Character

Can a story have too much plot?

Can a story have too much plot?

It might surprise you (especially if you’re a regular reader of the site), but the answer is absolutely, yes.

Implicit in the question of too much plot is the idea that a story should have more of something else. Usually that something else is character. This is where we find the well-entrenched battleground of “plot vs. character.”

It’s unfortunate these two crucial ingredients of story are often presented as exclusive opposites—bitter rivals who can barely stand each other—because the discussion at the heart of “plot vs. character” is much more nuanced. As you probably know if you’ve spent any time on the site, I dislike the whole structure of the “plot vs. character” discussion. Too often, it’s presented as a simplistic either/or paradigm that demands a the clear winner: either plot or character must be the undisputed Monarch of Story.

Ultimately, what that argument is really about is a style of writing. Those arguing for more plot are usually arguing for more conventional, often genre fiction; those arguing for more character are usually arguing for more interior-oriented, often experimental, literary fiction. That’s a discussion for another day, but suffice it that both types of story almost inevitably require both plot and character.

As we’ve discussed in many previous posts, plot and character are less competitors and more symbiotes. Once you understand the self-generating cycle of “character creating plot creating character creating plot,” you understand that the two work optimally when they balance each other within the overall storyform.

But what happens when something is out of balance? What happens when your story has too much character? Or too much plot?

Can Your Story Have Too Much Character Development?

It’s actually really hard to do too much character. Usually, if there’s “too much” character development in a story, it’s a sign not so much of character problems as it is self-indulgent writing in which the author counted too much on readers’ loving the characters enough to watch them do… nothing.

When characters are vibrant and well-drawn, they enter that beautiful cycle of creating plot. It’s tough to write good characters without also writing plot of some sort. Even in more literary-leaning books, such as Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain, which are obviously preoccupied with character, the characters are vibrant enough to create a forward-moving plot out of even mundaneness such as farm chores.

(It’s true that even more “literary” stories may spend almost their entire word count within the characters’ head, with little happening in the exterior world. Plot is admittedly thin in these stories. The authors have intentionally created a “story” that is more about the descriptive detail or philosophical thesis. Sometimes you’ll also see these devices woven into a larger, more obvious plot, as in some of Thomas Mann’s or Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s brooding asides.)

Pretty much the only time you’ll run into problems with a story having “too much character” is if those characters are either failing to generate plot and/or aren’t entertaining enough to carry the story past scenes that are lacking in external conflict or momentum.

What About Too Much Plot?

Much more common than “too much character development” is the complaint of a story that has “too much plot.”

Poor maligned plot. It’s always getting a bad rap:

“That book was too plot heavy.”

“Too much plot vs. character!”

“That movie was nothing but stuff blowing up.”

But as it turns out none of these problems are about plot. Rather, the problem is “not enough character.”

“Too much plot” is almost always a sign the external conflict is operating on its own accord without being driven by dynamic characters. Stuff is happening, but the characters are just ciphers along for the ride. As a viewer or reader, I’m sure you can think of more than a few stories that fit the bill. They’re frustrating as all get-out. The plot might be great. If it’s a movie, the cast might be stellar. The theme might even be powerfully strong. But if the characters are just vapid automatons, the story feels empty.

5 Signs of Cardboard Characters

Recently, I watched several movies that checked all the above boxes. They could have been great. But they all stumbled and ended up just going through the motions, not because their plots were problematic but because the characters just weren’t there.

Today, we’re going to look specifically at Netflix’s recent army/heist flick Triple Frontier (along with The Red Sea Diving Resort and Amazon’s The Dressmaker) as a way of discovering what went wrong and how you can identify and rectify imbalances between plot and character in your own stories.

1. The Characters’ Personalities Don’t Inform the Plot

Why are your characters in your story? Why are these specific characters in this story? If there’s no reason why this specific character is important to this story, you know you’ve got a problem.

The surest symptom is an unmemorable character. Almost always this lack of memorability is really a lack of specificity. It points to the fact that this character—his personality, his choices, his actions—are so bland and generalized that the character could be switched right out for an alternate take.

You might also recognize the problem if you realize the character’s most important actions in the story could be undertaken just as easily by a different character. When this happens, you can be pretty sure you’ve got a character (or two) who’s nothing more than an interchangeable part—a Lego guy who just needs a new head.

For Example: Triple Frontier has the sweet double advantage of a simple plot and a simple cast—just five main players. But why five? Why these five? With the exception of Oscar Isaac’s protagonist, most of the other characters have little to no development. In particular, Garrett Hedlund and Pablo Pascal are immediately forgettable. One’s a boxer dumb enough to get his brains beat out every week; the other’s a pilot dumb enough to get caught running drugs. That’s pretty much the only specific contributions either make to the story.

The Red Sea Diving Resort suffers exactly the same problem. Its protagonist is sketched pretty well, but almost all the supporting characters exist in the story with no more than one defining characteristic—none of which impact the story. We’ve got tough judo chick, vain beach dude, and stone-cold assassin—but none of them are developed past their characteristic moments.

2. The Story Isn’t About These Characters

Do you know what your story is about? I mean do you really know what your story is about?

The easy answer is that stories are always about their characters. Events in a story exist only to develop character. Either specific characters generate specific events, or they react to events (generated by other characters) in specific ways. If not—if your story is peopled with characters so bland they could be replaced at a moment’s notice—then you end up with a story that ultimately doesn’t mean anything. This is true no matter how great the premise or the action may be.

For Example: In its very first scene, Triple Frontier tells us what it’s about: the negative effects of the warrior lifestyle. It opens with Charlie Hunnam’s character talking to a group of soldiers about how his stint in Special Forces made it difficult for him live without violence or in his post-Army life. This throughline is emphasized many times, culminating when [SPOILER] the team’s once-respected leader, played by Ben Affleck, murders a farmer and is then retributively killed himself [/SPOILER].

But these developments never play organically, mostly because Affleck’s character isn’t well-developed. His Corruption Arc plays out more like a crazy personality shift than it does an organic devolution as the result of his specific choices and actions within the story. Had the script allowed its characters’ development to generate the plot, rather than shoehorning their character twists into the plot beats, the story could easily have shifted into a compelling and thought-provoking thematic discussion.

3. The Characters Lack Concrete and Specific Motivations

Often, the root cause of cardboard characters is a lack of concrete and specific motivations. What a character does in the plot is often much less important than why she does it. Monumental events can end up feeling bland when we don’t understand what is personally at stake for characters. Even small everyday events take on new significance when we understand what motivates the character (think of Liesel’s reading in The Book Thief).

Even if a character’s motivations aren’t explored in depth, if they are at least indicated early in the story they will have the ability to inform the subtext. What might otherwise be a two-dimensional hero in an action flick can take on at least a semblance of depth (think of Jason Bourne’s deeply personal and existential motivations adding unspoken depth and meaning to even the straight-up-race-em-chase-em of the third installment Bourne Ultimatum).

For Example: Triple Frontier didn’t totally bomb on this one. Viewers are given to understand that all five of the main characters have agreed to the central heist because of their problems in their post-military lives. We are given at least the hint of a specific personal reason for each character, even though only Isaac’s and Affleck’s motivations end up being pertinent.

The Red Sea Diving Resort fares even worse in this regard. Only the protagonist, played by Chris Evans, is given a slight backstory with an explanation of his fanatical motivation for rescuing the Ethiopian refugees. His teammates aren’t afforded even that. They’re there because they’re there, and that’s that. Not only does this skip over what might have been a lot of compelling development, it also robs the film of the potential for much stronger interpersonal conflict than what we get from Alessandro Nivola’s two-dimensional doctor.

4. The First Half of the Story Spends More Time Setting Up the Plot Than It Does the Characters

If your story spends more time setting up the plot than it does the characters, that’s almost always going to point to a disparity.

Complicated plots are annoying. And boring.

Yep. You read right.

We don’t like stories because the plots are complicated. To begin with, complicated plots usually don’t work. (Think about it. There’s nothing simpler than a good whodunit.) But more than that, complicated plots take time away from what audiences really do enjoy—and that’s complex characters dealing with simple but difficult situations.

These situations often seem complicated, but they’re not. Good plots are as simple as presenting characters with a really difficult lose-lose (or win-win) choice. The mechanics of the choosing might be complicated, but the question itself is not.

When this happens, a ton of story space is freed up for—you guessed it—character development. Most of that development should happen upfront. If the characters aren’t the most compelling thing about your story, then chances are audiences won’t stick with it (or, best case, they stick with it but promptly forget about it).

For Example: Neither Triple Frontier nor Red Sea Diving Resort were terrible in this respect. But compare them to a classic action movie: Jurassic Park.

Jurassic Park balances plot and character just about perfectly. The entire first half of the story is spent on the characters and their reactions to the dilemma with which they’ve been presented (dinosaurs are back—is this a good thing or a very, very bad thing?). No action whatsoever happens until the Midpoint when the tropical storm unleashes the dinos. By then, the characters have been suitably developed so we care what happens to them and we understand why they make the choices they make. From the Midpoint on, the plot can roar furiously to the forefront without seeming like it’s “too much.”

5. Characters Are Specific But Exist Only as Shallow Stereotypes to Fulfill Plot Points

At this point, you might look at your cast and be relieved to discover all your characters have specific roles to play, they all have specific personalities and motivations, and none of their actions could be seamlessly handed over to another character.

But there’s one last problem to be aware of.

Sometimes characters check all the above boxes and yet still exist not to generate plot, but to serve it. Almost always, this character emerges as a stereotype of some sort (either a stereotyped character or a character whose development is forced to fit a formulaic plot). Two of the most common culprits are antagonists (who are bad just because they’re expected to be bad) and love interests (who fall in love with the protagonist just because they’re expected to fall in love). But even protagonists can fall into this pit when they’re heroic just because they’re expected to be heroic or they end up “winning” the conflict just because they’re expected to win.

Be wary of characters going through the motions. Make sure there is a solid and compelling reason for a character’s every action within the story. Just as importantly, make sure his arc is developed throughout the story. Whatever happens to him at the end must fulfill two requirements:

It must be properly set up in the story’s beginning.

It must resonate thematically in the story’s end.

For Example: Most of the characters in Triple Frontier and Red Sea Diving Resort are so one-dimensional they don’t even risk this problem. A better example is found in The Dressmaker. Characterization in this film is excellent until the Third Act when everything falls apart to little thematic purpose.

By far the weakest character throughout is the protagonist’s love interest, played by Liam Hemsworth. Throughout the story, he has little to do except fall in love with Kate Winslett and little reason to do so except… why not? (I have a feeling that might have been better executed in the novel, which I have not read.) But this doesn’t become blatantly problematic until the Third Plot Point when [SPOILER] the character dies out of the blue—and the rest of the Third Act fails to make his death a plot-generating catalyst. Rather, what it feels like is that the love-interest character existed for no other reason than to shock both the protagonist and the audience with his death.[/SPOILER]

***

The holy grail of good storytelling is great characters in a great plot. Learning to recognize the proper balance of plot and character is sometimes easiest when you first learn to understand what an imbalance looks like. If you can spot and correct instances where your plot is operating without enough input from your characters, you’ll be well on your way to writing exceptional stories.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever feared you’ve written a story with too much plot—or too much character? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/too-much-plot.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Tell if Your Story Has Too Much Plot, Not Enough Character appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 12, 2019

How to Evoke Reader Emotions With “Surprisingness”

Have you ever read a book for a second, third, even tenth time—just to experience the emotion the story evokes? Clearly the elements of the story aren’t a surprise. You know exactly what to expect. If so, you were benefiting from an author who knew how to evoke reader emotions.

Have you ever read a book for a second, third, even tenth time—just to experience the emotion the story evokes? Clearly the elements of the story aren’t a surprise. You know exactly what to expect. If so, you were benefiting from an author who knew how to evoke reader emotions.

Literary agent Donald Maass says that emotions are most effectively evoked by trickery–when readers aren’t noticing we are manipulating them. He says:

Artful fiction surprises readers with their own feelings.

I can honestly say that, as a reader, the best novels do just that. They evoke such emotions from me—unexpected emotions—that I am stunned by my own reactions.

We writers want to evoke emotion throughout our novels—big, small, expected, and unexpected—so that even when readers know what emotion is being stirred in them, when they see what’s coming, it doesn’t reduce the impact.

The Net of “Surprisingness”

C.S. Lewis said people go back and reread certain stories over and over not to be surprised (because the reader already knows what is going to happen) but for the “surprisingness.” It’s the quality of unexpectedness that delights us, just as it does children who want the same story read over and over. The fact that children know what is about to happen only makes them more excited. Like children, we savor the richness of a story again and again.

Lewis calls the plot of the story “the net whereby to catch something else.” That“something” is what he refers to as “much more than a state or quality.” Real life, he says, is a series of events, but if that is all it is, there is no deeper meaning or feeling of adventure. That net of the story, for a little while, transcends us and entangles us in the wonder and awe of living. That is what Lewis says the best stories will do.

When we can catch readers in a net of emotions—especially unexpected and surprising ones—that’s powerful magic.

Research shows when someone is surprised, dopamine increases and emotions intensify up to 400%. Heightened attention ensues, as does extreme curiosity, in an attempt to figure out what is happening.

Surprise also causes a shift. It forces a change in perspective. Your reader becomes hyper-alert, curious, in the moment, a perfect state for receiving the unexpected emotion.

How to Evoke Reader Emotions That Are Unexpected

When I began to read the chapter in Garth Stein’s The Art of Racing in the Rain in which Enzo the beloved narrator dog is dying, I just knew what was going to happen to me, what I was about to get into. Most people relate to losing a pet. Most people share that universal affection for sweet animal companions.

When I began to read the chapter in Garth Stein’s The Art of Racing in the Rain in which Enzo the beloved narrator dog is dying, I just knew what was going to happen to me, what I was about to get into. Most people relate to losing a pet. Most people share that universal affection for sweet animal companions.

While I have met many readers who confessed they wept their heart out reading this joyously sad scene, I imagine some readers weren’t moved at all. But I bet almost everyone who read that book felt something. You don’t bother to read a novel told in “first-person dog POV” if you don’t like dogs. And it says something that this novel was on the NYT’s bestseller list for 156 weeks.

The key to its brilliance lies solely in neither the wonderful writing nor the universal resonance of “it’s so horrible to lose someone (person or animal) you love.” Rather, it’s the masterful execution of the scene as joyously sad. I chose that phrase to make a point: when unexpected emotions are evoked in us, it awes us.

Pay attention to that.

You wouldn’t expect a scene that has you watching a dog die—one that breaks your heart—to make you simultaneously happy even to the point of laughing. That’s what makes that scene so brilliant. The whole time I was crying in anguish, I was also laughing with joy. The scene was absolutely authentic in every way. It was utterly surprising as much as it was totally expected.

Don’t Try to Name Emotions

I felt when reading Enzo’s death scene. I could toss around a whole lot of words, but trying to name complex emotions is like trying to catch the wind with chopsticks. The secret lies in Hemingway’s brilliant advice:

Find what gave you the emotion . . . then write it down, making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling as you had.

Think of it this way. You might not know what to name a particular color shade, but if you have a few tubes of paint and play around with the quantities, you just might be able to re-create the color. That’s what you need to do with the words on your palette to create the same emotion you wish readers to experience.

There is something to be said about building intimacy with characters. It might be hard to evoke emotion in readers for a character to whom they have only just been introduced. This is why Garth Stein placed his most powerful emotional scene near the end of the book, when readers are fully committed to Enzo and Denny, so it might pack the biggest emotional punch.

If you haven’t read The Art of Racing in the Rain, I highly recommend it as a way of understanding the power of “surprisingness.” Those of you who have already read the book may want to read this post and pay attention to the incongruous, unexpected emotions you feel as you go through the powerful passage at the Climax of the story. Note the universal feelings the old dog Enzo expresses that make you think, Me too!

Garth Stein does a brilliant job of not only conveying Enzo’s complex emotions, which are both expected and unexpected, but evoking so many emotions in the reader.

Finding a way to surprise your character and your reader adds micro-tension to your pages. This sparks those emotions in your readers that keep them engaged, whether it be something positive like amusement or negative like outrage or fear. Know how you want your readers to feel and lead them there.

***

Yes, readers love to be surprised. The unexpected surprises us. It might scare us, delight us, or move us profoundly. Yet, often a character’s reaction to a situation is wholly predictable and still it moves us deeply. Consider just about any love story that ends in happily ever after. Predictability really has nothing to do with emotional impact. It’s how the story is shown that matters—how those emotions are conveyed in a way that is believable, masterful, and moving.

Want to learn how to become a masterful wielder of emotion in your fiction? Enroll in C.S. Lakin’s new online video course, Emotional Mastery for Fiction Writers, before September 1st, and get half off using this link!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you hope to evoke reader emotions by the end of your story? Tell us in the comments!

The post How to Evoke Reader Emotions With “Surprisingness” appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 5, 2019

Learn 5 Types of Character Arc at a Glance: The 3 Negative Arcs (Part 2 of 2)

Stories are about change. Sometimes that change is positive, driven by hopeful or even heroic people. But sometimes that change is negative, driven by humanity’s darkest urges and blindnesses. Both stories are necessary, which is why we’re rounding out our two-part series with a beat-by-beat look at the three Negative Arcs—the Disillusionment Arc, the Fall Arc, and the Corruption Arc.

Stories are about change. Sometimes that change is positive, driven by hopeful or even heroic people. But sometimes that change is negative, driven by humanity’s darkest urges and blindnesses. Both stories are necessary, which is why we’re rounding out our two-part series with a beat-by-beat look at the three Negative Arcs—the Disillusionment Arc, the Fall Arc, and the Corruption Arc.

Last week when we looked at the two Heroic Arcs (the Positive-Change Arc and the Flat Arc), I talked about how someone pointed out I didn’t yet have an easily-scannable resource that put the basic structures of all the arcs in one place. This series ended up being too long to put in precisely one place. But as of today, you can at least find the five major arcs all linked from one place!

>>Click Here to Read Pt. 1: The 2 Heroic Arcs

You’ll remember last week’s post also covered the six basics common to all types of arc. Be sure to check that post for the overview, or click the links below for more in-depth posts on each topic:

2. The Lie the Character Believes

3. & 4. The Thing the Character Wants & the Thing the Character Needs

5. The Ghost

Don’t forget that for a more in-depth look at all things character arc, you can check out my book Creating Character Arcs and its companion workbook.

And now let’s down and dirty with the Negative-Change Arcs.

The Negative Change Arcs

>>Click Here to Read more About the Negative Change Arcs

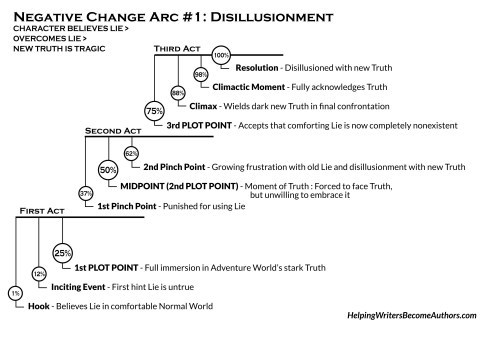

1. The Disillusionment Arc

Character Believes Lie > Overcomes Lie > New Truth Is Tragic

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)

1%: The Hook: Believes Lie in Comfortable Normal World

The protagonist believes a Lie that has so far proven necessary or functional in the existing Normal World, which is often a comfortable and complacent place.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Hint Lie Is Untrue

The Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle hint that the Lie will no longer serve the protagonist as effectively as it has in the past.

25%: The First Plot Point: Full Immersion in Adventure World’s Stark Truth

The protagonist is faced with a consequential choice, in which the comfortable “old ways” of the Lie-ridden First Act show themselves ineffective in the face of the main conflict’s new stakes. The protagonist will pass through a Door of No Return, in which he is forced to enter the Adventure World of the main conflict in the Second Act, where he is confronted by a stark and painful new Truth.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Punished for Using Lie

The protagonist is “punished” for using the Lie. In the Normal World, he was able to use the Lie to get the Thing He Wants. But in the Adventure World, this is no longer a functional mindset. Throughout the First Half of the First Act, he will try to use his old Lie-based mindsets to reach his goals and will be “punished” by failures until he begins to learn how things really work.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Forced to Face Truth, But Unwilling to Embrace It

The protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth in which he comes face to face with the thematic Truth (often via a simultaneous plot-based revelation about the external conflict). This is the first time the protagonist consciously recognizes the Truth and its power. He is, however, horrified by the implications of this dark new Truth. Although he can no longer deny the Truth, he is unwilling to fully embrace it or to surrender his comparatively wonderful old Lie.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Growing Frustration With Old Lie and Disillusionment With New Truth

The protagonist is forced to confront consistently-increasing examples of the Lie’s lack of functionality in the real world. He grows more and more frustrated with the Lie’s limitations. He begins to accept the horrible Truth. He is profoundly disillusioned by his new worldview, even as he begins to be “rewarded” for using the Truth to reach for the Thing He Wants.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Accepts That Comforting Lie Is Now Completely Nonexistent

The protagonist is confronted by an irrefutable “low moment,” in which he can no longer fool himself that the dark Truth is not true. He must not only accept this new Truth, he must also admit that his comforting old Lie is now completely nonexistent.

88%: The Climax: Wields Dark New Truth in Final Confrontation

The protagonist enters the final confrontation with the antagonistic force to decide whether or not he will gain the Thing He Wants. Directly before or during this section, he consciously and explicitly embraces and wields the dark new Truth.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Fully Acknowledges Truth

The protagonist uses the Truth and all it has taught him about himself and the conflict to gain the Thing He Needs. Depending the nature of his Truth, he may also gain the Thing He Wants (only to discover that, in light of his new knowledge, it is worthless), or he may realize he needs to sacrifice it for his own greater good. As a result, he definitively ends the conflict between himself and the antagonistic force.

100%: The Resolution: Disillusioned With New Truth

The protagonist either enters a new Normal World or returns to the original Normal World, but with a jaded eye now that he knows the Truth.

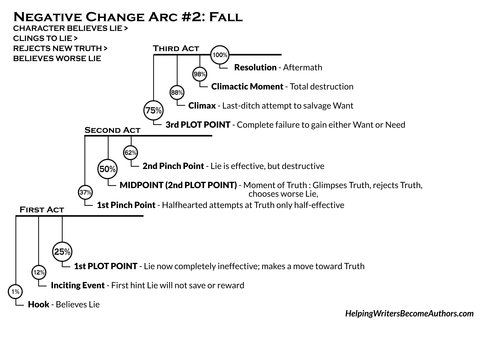

2. The Fall Arc

Character Believes Lie > Clings to Lie > Rejects New Truth > Believes Worse Lie

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)

1%: The Hook: Believes Lie

The protagonist believes a Lie that has so far proven necessary or functional in the existing (often destructive) Normal World.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Hint Lie Will Not Save or Reward

The Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle hint that the Lie will no longer effectively protect or reward the protagonist in her current circumstances.

25%: The First Plot Point: Lie Now Completely Ineffective; Makes Move Toward Truth

The protagonist is faced with a consequential choice in which the “old ways” of the Lie-ridden First Act show themselves ineffective in the face of the main conflict’s new stakes. The protagonist is given an early choice between old Lie and new Truth. She passes through a Door of No Return, in which she makes a move toward the Truth and, in so doing, is forced to leave the Normal World of the First Act and enter the Adventure World of the main conflict in the Second Act.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Halfhearted Attempts at Truth Only Half-Effective

The protagonist tries to wield the Truth as a means of gaining the Thing She Wants, but does so only with limited understanding or enthusiasm. She is stuck in a limbo-land where the old Lie is no longer a functional mindset, but where her halfhearted attempts at the Truth prove likewise only half-effective.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Glimpses Truth, Rejects Truth, Chooses Worse Lie

The protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth in which she comes face to face with the thematic Truth (often via a simultaneous plot-based revelation about the external conflict). This is the first time the protagonist consciously sees the full power and opportunity of the Truth. However, she also sees the full sacrifice demanded if she is to follow the Truth. Unwilling to make that sacrifice, she rejects the Truth and chooses instead to embrace a Lie that is worse then the original.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Lie Is Effective, But Destructive

Uncaring about the consequences, the protagonist wields her Lie well and finds it effective in moving toward the Thing She Wants. However, the closer she gets to her plot goal, the more destructive the Lie becomes both to her and to the world around her.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Complete Failure to Gain Either Want or Need

The protagonist is confronted by a “low moment,” in which she experiences a complete failure to gain the Thing She Wants. This failure is a direct result of the collective damage wrought by her Lie in the Second Half of the Second Act. The “means” caught up to her before she reached her “end.” However, even when faced by all the evidence of the Lie’s destructive power, the protagonist still refuses to repent or to turn to the Truth.

88%: The Climax: Last-Ditch Attempt to Salvage Want

Upon entering the final confrontation with the antagonistic force, the protagonist doubles down on her Lie in a last-ditch attempt to salvage the Thing She Wants.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Total Destruction

Crippled by the Lie (in both the internal and external conflicts), the protagonist is unable to gain the Thing She Wants (or gains it only to discover it is useless to her). Instead, she succumbs to total personal destruction.

100%: The Resolution: Aftermath

The protagonist must confront the aftermath of her choices. She may finally and futilely accept the inescapable Truth. Or she may be left to cope, blindly, with the consequences of her choices.

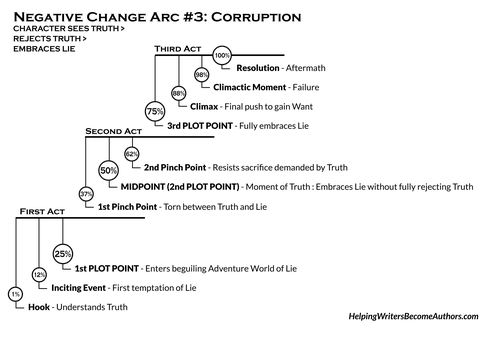

3. The Corruption Arc

Character Sees Truth > Rejects Truth > Embraces Lie

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)

1%: The Hook: Understands Truth

The protagonist lives in a Normal World that allows for or even encourages the thematic Truth. As a result, the protagonist starts out with an understanding of the Truth.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Temptation of Lie

The Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle temptation that the Lie might be able to serve the protagonist better than the Truth.

25%: The First Plot Point: Enters Beguiling Adventure World of Lie

The protagonist is faced with a consequential choice, in which he is enticed out of the First Act’s safe, Truth-based Normal World into the Second Act’s beguiling, Lie-based Adventure World. Not realizing the danger (or believing he is weighing the consequences), the protagonist is lured through the Door of No Return by the promise of the Thing He Wants.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Torn Between Truth and Lie

The protagonist is torn between his old Truth and the new Lie. The Lie proves itself effective in moving him nearer the Thing He Wants. But he wages an internal conflict as he recognizes he is moving further and further away from his old convictions and understandings of the world.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Embraces Lie Without Fully Rejecting Truth

The protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth in which he comes face to face with the Lie in all its power. He recognizes he cannot gain the Thing He Wants without the Lie. Although he is not yet willing to fully and consciously reject the Truth, he makes the decision to fully embrace the Lie.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Resists Sacrifice Demanded by Truth

The protagonist is “rewarded” for using the Lie. Building upon what he learned at the Midpoint, the protagonist will start implementing Lie-based actions in combating the antagonistic force and reaching toward the Thing He Wants. The Truth pulls on him, demanding sacrifices he is not willing to give. He begins resisting the Truth more and more adamantly.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Fully Embraces Lie

The protagonist utterly rejects the Truth and embraces the Lie. He acts upon this in a way that creates a “low moment” for the world around him (and for him morally, even if he refuses to recognize it). He is now willing to knowingly endure the consequences of rejecting the Truth in exchange for what he sees as the rewards of embracing the Lie.

88%: The Climax: Final Push to Gain Want

The protagonist enters the final confrontation with the antagonistic force to decide whether or not he will gain the Thing He Wants. Unhampered by the Truth, he pushes forward ruthlessly toward his plot goal.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Moral Failure

The protagonist uses the Lie and all it has taught him in an attempt to gain the Thing He Wants. He may gain the Thing He Wants and remain senseless to the evil engendered by his actions. Or he may gain the Thing He Wants only to be devastated when he realizes it wasn’t worth what he sacrificed. Or he may fail to gain the Thing He Wants and be devastated by the realization that his sacrifices to the Lie were fruitless. One way or another, he definitively ends the conflict between himself and the antagonistic force.

100%: The Resolution: Aftermath

The protagonist must confront the aftermath of his choices. He may turn away from the Lie, admitting his mistake and accepting the consequences. Or he may callously forge ahead, intent on continuing to use the Lie to further his own ends.

***

Needless to say, there are many variations of these five arcs. But if you can identify and master these five, you’re well on your way to writing a powerful evolution that will resonate with all your readers.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What types of character arc have you written? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/negative-change-arcs.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Learn 5 Types of Character Arc at a Glance: The 3 Negative Arcs (Part 2 of 2) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 29, 2019

Learn 5 Types of Character Arc at a Glance: The 2 Heroic Arcs (Part 1 of 2)

There are only two or three human stories, but they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they never happened.–Willa Cather

The many different approaches to story theory break down the number of “human stories” into different categories. Perhaps there are just two—comedy and tragedy. Perhaps there are Vonnegut’s eight “shapes.” Today, I’m going to argue for five—the five basic types of character arc.

These include the two Truth-driven or heroic arcs—the Positive-Change Arc and the Flat Arc. And the three Lie-driven or Negative-Change Arcs—the Disillusionment Arc, the Fall Arc, and the Corruption Arc.

I’ve talked about all these arcs extensively, beat by beat, both in my series of posts and my book Creating Character Arcs and its companion workbook. But as someone recently pointed out in an email, I’ve never compiled a basic structural beat sheet of what all the arcs look like at a glance.

As of now, I’m remedying that with a two-part series that puts the basic principles and types of character arc all in one place. Today, we’re going to start by talking about, first, the basic ingredients necessary in any type of character arc, followed by a detailed but at-a-glance look at the two “truth-based” heroic arcs.

The 6 Foundational Ingredients of All Character Arcs

Let’s get started. All five arcs share several commonalities, beginning with their foundational structure (which I prefer to break into three acts and ten beats, as you’ll see below). Beyond that, they also share the following six foundational ingredients, which can then be mixed to the author’s needs according to whichever arc has been chosen for the story.

1. The Thematic Truth

The theme is your story’s Truth. It is a universal statement about how the world works. In almost all instances (with the arguable exception of the Disillusionment Arc), the Truth will represent an ultimately positive (if sometimes painful) value, which will help the characters interact more fruitfully and less futilely with the world.

>>Click Here to Read More the Truth Your Character Believes

2. The Lie the Character Believes

The Lie is a misconception about the world that stands in contrast to the Truth. At the beginning of the story, the Lie will be preventing someone (either the protagonist or, in the case of the Flat Arc, supporting characters) from seeing, understanding, and/or accepting a necessary Truth. The entire character arc—and, indeed, the entire story—is about if and how the character(s) will be able to evolve past the Lie into the Truth.

>>Click Here to Read More About the Lie Your Character Believes

3. & 4. The Thing the Character Wants vs. the Thing the Character Needs

The inner thematic conflict of Truth vs. Lie will manifest in the external plot conflict as the Thing the Character Wants vs. the Thing the Character Needs. Usually, the Need is nothing more or less than the Truth, although it can take a physical form as well. The Want may be something large and abstract (such as “respect”), but it should boil down to a very specific plot goal (“a promotion” or “a college degree”). Your character’s evolving proximity to the Want and the Need will change in direct relation to the specific character arc.

>>Click Here to Read More About the Thing Your Character Wants and the Thing Your Character Needs

5. The Ghost

The Ghost (sometimes also referred to as the “wound”) is the motivating catalyst in your protagonist’s backstory. This is the reason the character believes in the Lie and can’t see past it to the Truth. As its name (coined by script doctor extraordinaire John Truby) suggests, the Ghost is something that haunts the character, something that can’t just be moved past. Often, it is a traumatic event, but even something seemingly positive (such as a parent’s pride in a child) can cause a character to believe the damaging Lie.

>>Click Here to Read More About the Ghost

6. The Normal World

The Normal World is the initial setting in the story’s First Act, meant to illustrate the character’s life before the story’s main conflict. Depending on the type of arc, the Normal World will symbolically represent either the story’s Truth or the story’s Lie. The Normal World may be a definitive setting, which will change at the beginning of the Second Act, when the character enters the Adventure World of the main conflict. However, it may also be more metaphorical, in which case the setting itself will not switch, but rather the conflict will change the setting around the protagonist (for example changing the atmosphere from friendly to hostile).

>>Click Here to Read More About the Normal World

The 2 Heroic Arcs

The Positive-Change Arc and the Flat Arc are the “happy” or “heroic” arcs. In these stories, the protagonist either learns or already knows the Truth—and uses it to positively impact the story world.

1. The Positive-Change Arc

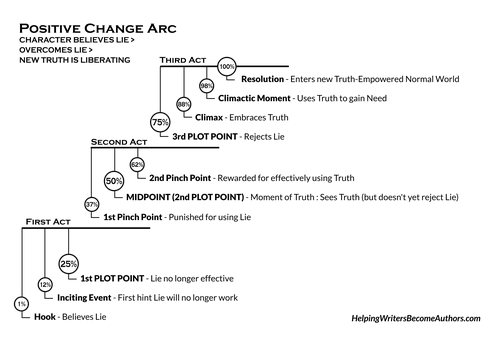

Character Believes Lie > Overcomes Lie > New Truth Is Liberating

>>Click Here to Read More About the Positive-Change Arc

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)

1%: The Hook: Believes Lie

The protagonist believes a Lie that has so far proven necessary or functional in the existing Normal World.

12%: The Inciting Event: First Hint Lie Will No Longer Work

The Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, also brings the first subtle hint that the Lie will no longer serve the protagonist as effectively as it has in the past.

25%: The First Plot Point: Lie No Longer Effective

The protagonist is faced with a consequential choice, in which the “old ways” of the Lie-ridden First Act show themselves ineffective in the face of the main conflict’s new stakes. Although the protagonist does not yet recognize the inefficacy of the Lie, he will still pass through a Door of No Return, in which he is forced to leave the Normal World of the First Act and enter the Adventure World of the main conflict in the Second Act.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Punished for Using Lie

The protagonist is “punished” for using the Lie. In the Normal World, he was able to use the Lie to get the Thing He Wants. But in the Second Act, this is no longer a functional mindset. Throughout the First Half of the Second Act, he will try to use his old Lie-based mindsets to reach his goals and will be “punished” by failures until he begins to learn how things really work.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Sees Truth, But Doesn’t Yet Reject Lie

The protagonist encounters a Moment of Truth in which he comes face to face with the thematic Truth (often via a simultaneous plot-based revelation about the external conflict). This is the first time the protagonist consciously recognizes the Truth and its power. He does not yet, however, recognize the Truth and the Lie as incompatible. He will attempt to use both in the Second Half of the Second Act.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Rewarded for Effectively Using Truth

The protagonist is “rewarded” for using the Truth. Building upon what he learned at the Midpoint, the protagonist will start implementing Truth-based actions in combating the antagonistic force and reaching toward the Thing He Wants. He will be “rewarded” by successes as he moves nearer and nearer his ultimate plot goal.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Rejects Lie

The protagonist is confronted by a “low moment” brought about by his continuing refusal to fully reject the Lie. Finally, the protagonist must confront the true stakes of what he stands to lose if he continues to embrace the Lie. Feeling all but defeated, he rejects the Lie. Implicitly, he also fully embraces the Truth.

88%: The Climax: Embraces Truth

The protagonist enters the final confrontation with the antagonistic force to decide whether or not he will gain the Thing He Wants. Directly before or during this section, he consciously and explicitly embraces and wields the Truth.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Uses Truth to Gain Need

The protagonist uses the Truth and all it has taught him about himself and the conflict to gain the Thing He Needs. Depending upon the nature of his Truth, he may also gain the Thing He Wants, or he may realize he needs to sacrifice it for his own greater good. As a result, he definitively ends the conflict between himself and the antagonistic force.

100%: The Resolution: Enters New Truth-Empowered Normal World

The protagonist either enters a new Normal World or returns to the original Normal World, where he can now live as a Truth-empowered individual.

2. The Flat Arc

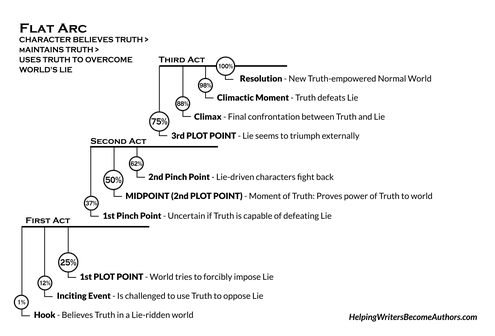

Character Believes Truth > Maintains Truth > Uses Truth to Overcome World’s Lie

>>Click Here to Read More About the Flat Arc.

Graphic by Joanna Marie, from the Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Click the image for a larger view.

The First Act (1%-25%)

1%: The Hook: Believes Truth in a Lie-Ridden World

The protagonist believes a Truth that the rest of the Normal World around her rejects. The Normal World and most of its characters are mired in a central Lie which enslaves them in some way.

12%: The Inciting Event: Challenged to Use Truth to Oppose Lie

The Call to Adventure, when the protagonist first encounters the main conflict, presents a direct challenge to her Truth. The question at this point is whether or not she can be convinced to take action in wielding her Truth against the Lie of the world around her.

25%: The First Plot Point: World Tries to Forcibly Impose Lie

The protagonist is faced with a consequential choice, in which the antagonistic force attempts to forcibly impose the Lie upon her or others. In refusing to relinquish her Truth for the Lie, the protagonist passes through a Door of No Return, in which she is forced to leave the Normal World of the First Act and enter the Adventure World of the main conflict in the Second Act.

The Second Act (25%-75%)

37%: The First Pinch Point: Uncertain if Truth Is Capable of Defeating Lie

The protagonist struggles to use her Truth against the strength of the antagonistic force’s Lie. She experiences doubt about whether her Truth is capable of defeating the Lie and, as a result, if it is indeed the Truth.

50%: The Midpoint (Second Plot Point): Proves Power of Truth to World

The protagonist perseveres in following her Truth. She offers a Moment of Truth to the world around her. This is the first time the protagonist will demonstrably exhibit the full power and purity of the Truth. At least one significant supporting character will be impacted (positively or negatively) by this revelation.

62%: The Second Pinch Point: Lie-Driven Characters Fight Back

In response to the protagonist’s powerful demonstration of Truth at the Midpoint, other Lie-driven characters will double down on the Lie and use it to mount a formidable counter-attack upon the protagonist and her Truth.

The Third Act (75%-100%)

75%: The Third Plot Point: Lie Seems to Triumph Externally

The Lie-driven tactics of the antagonistic force hit the protagonist hard, even to the point of the protagonist’s seeming defeat in the external conflict. The protagonist is confronted by a “low moment” brought about by the supporting characters’ continuing refusal to fully reject the Lie. The protagonist must confront the true stakes of what she stands to sacrifice if she continues to embrace the Truth. Even in the face of overwhelming odds, she reaffirms her conviction of the Truth.

88%: The Climax: Final Confrontation Between Truth and Lie

The protagonist enters the final confrontation with the antagonistic force to decide whether or not she will gain the Thing She Wants. She consciously and explicitly embraces and wields the Truth.

98%: The Climactic Moment: Truth Defeats Lie