K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 38

November 26, 2018

20 Unique Gifts for Writers This Christmas

Christmas gifts that offer a mix of whimsy, fun, and practicality are the best. Whimsy, fun, and practicality are also three things writers seek on as daily basis. Guess that means we’re the perfect gift recipients! This year’s round-up of unique gifts for writers will help you find the right gift for your writing buddies, critique partners, and editors—and it just might help you nudge family and friends in the right direction for your own stocking as well.

Christmas gifts that offer a mix of whimsy, fun, and practicality are the best. Whimsy, fun, and practicality are also three things writers seek on as daily basis. Guess that means we’re the perfect gift recipients! This year’s round-up of unique gifts for writers will help you find the right gift for your writing buddies, critique partners, and editors—and it just might help you nudge family and friends in the right direction for your own stocking as well.

And if you want even more fun ideas, check out these roundups of gifts for writers from previous years:

3 Gifts for Writers Under $10

1. “I Read Past My Bedtime” Keychain – $4

2. Gold (or Silver—or Rose Gold) Mouse Pad – $9.50 (w/ S&H)

3. “My First Draft of My Amazing Novel” Notebook – $10

6 Gifts for Writers Under $20

4. Q&A a Day for Writers: 1-Year Journal – $12

5. Desktop Weekly Planner and Organizer – $15

6. “I Am Either Writing or Thinking About It” Phone Stand and Grip – $15

7. Writer Patent Prints, Set of 4 – $18

8. Library Card Tote Bag – $19

9. “Plot–It Builds Character” T-Shirt – $20

5 Gifts for Writers Under $30

10. “Caffeinated Writer” Spoon – $22 (w/ S&H)

11. “Write Your Story” Ring – $23 (w/ S&H)

12. Customized Journal – $24

13. “Pay No Attention to My Browsing History—I’m a Writer, Not a Serial Killer” Mug – $25 (w/ S&H)

14. Superhero Bookend – $28

3 Gifts for Writers Under $50

15. “The Reader” Desktop Decor – $36

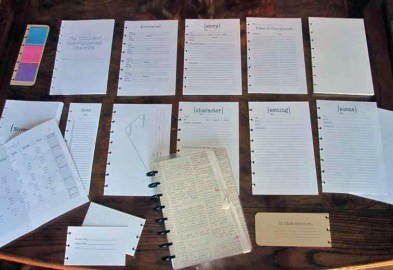

16. WriteMind Planner – $36 (w/ S&H)

>>Click here to read my rave review of the WriteMind Planner.

17. The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands – $41

3 Gifts for Writers Under $70

18. Tree Bookcase – $60

19. Monitor Stand – $67

20. Writing Desk – $70

Bonus Christmas Gifts for Writers: Writing Books

And if you still haven’t found the right gift for your list or a fellow writer’s this year, you can’t go wrong with the gift of learning. You can check out my full list of Recommended Reading for Writers and my own series of writing books below. Merry Christmas, everyone!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What gifts for writers have you asked Santa for this year? Tell me in the comments!

The post 20 Unique Gifts for Writers This Christmas appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 23, 2018

Black Friday Special: 25% off the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software

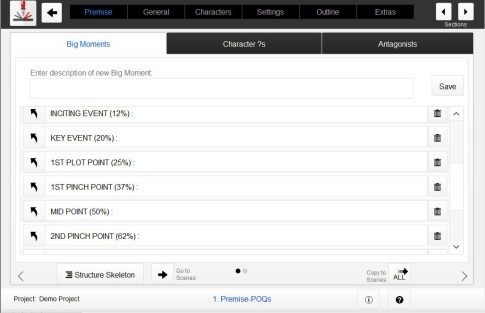

This Black Friday weekend, you can use the code OUTLINE to grab my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software at a special holiday discount of 25% its normal price of $40.

Start Outlining Your Best Book Today

As a reader of my blog, you can access a special 25% discount code for my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software. Just enter the code OUTLINE at checkout. This deal will only be available Black Friday through Cyber Monday. Enjoy!

How Can the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software Help You?

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook computer program is a brainstorming tool for writers. It is designed to guide you in discovering the brilliant possibilities in your ideas, so you can identify those best suited to creating a solid story that will both entertain and move your readers.

The software provides an easy fill-in-the-blanks format that will guide you through every step of the process. Creating your own outline is as simple as starting on the first screen, using the prompts and lessons to work through your story in the most intuitive way, and clicking through the tabs at the top to access important sections.

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook program makes outlining a fun and empowering process that will help you write your best story.

Features:

• Outline – Create a story with a solid Three-Act plot structure and perfect scene structure.

• Premise – Easy fill-in-the-blanks give you a perfect elevator pitch every time.

• General Sketches – Brainstorm the big picture of your scene list, character arcs, and theme.

• Character – Get to know your characters with an extensive character interview, featuring 100+ questions.

• Settings – Keep track of your settings, explore your best options, and answer helpful world-building questions.

• Fun Extras – Import your mind maps and world maps, keep track of your story’s timeline, cast your characters, and create story-specific musical playlists.

Here’s Your Coupon Code:

Don’t forget to use the code below to get 25% off your order of the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software:

OUTLINE

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

The post Black Friday Special: 25% off the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 19, 2018

How to Choose Your Story’s Plot Points

You’ve got a story, and you’ve got characters who are doing stuff in that story. That means you’ve got a plot. But how do you know if you’ve got your characters doing the right stuff at the right time?

You’ve got a story, and you’ve got characters who are doing stuff in that story. That means you’ve got a plot. But how do you know if you’ve got your characters doing the right stuff at the right time?

At first glance, this seems intuitive. Story is (or should be) a chain of causes and effects. Something happens, and that causes something else to happen. Nothing could be more sensible.

But the realities of plotting are more complicated.

If you’re attempting a specific artistic effect (and you should be), then it’s probably not going to suffice to just let your story’s events pour onto the page at random. Instead, you’re going to need to carefully plan each major structural moment—and everything in between—to create that end effect you’re going for.

Regardless whether your personal method favors plotting or pantsing, applying an understanding of structure to your story offers you a great advantage. Once you understand story’s fundamental framework, you can then make informed decisions about how to create your best possible Hook, Inciting Event, First Plot Point, Midpoint, Third Plot Point, Climax, and so on.

However, sometimes this sounds simpler and more obvious than it is in actual application—as evidenced by so many recent films and novels. These well-intentioned stories usually succeed in presenting plots that feature plausible chains of cause and effect. But because they haven’t optimized their structural integrity, they still end up failing in their chief mandate: offering stories of heart and soul.

Having just viewed Netflix’s Outlaw King, about Robert the Bruce’s final bid for Scottish independence, I feel this film offers a particularly good learning opportunity.

On its surface, there isn’t much to critique. Production values are good; the plot is a decent chain of causes and effects; the structural pieces are all in place; the story is one of wrenching sacrifice and determination.

And yet, as more than one IMDb review has stated, “the writing didn’t have a lot of heart.” Or, as Manohla Dargis aptly grumbles in the introduction to her NYTimes.com review of the movie:

At least in old Hollywood, filmmakers would also try to entertain you amid the clashes and post-combat huddles, giving you something more to watch and ponder than this movie’s oceans of mud, truckloads of guts and misty, unconsidered nationalism.

Here’s the thing: this film could easily have had it all. It’s all there in the story, waiting to be mined. A better understanding of structure and theme would have created better organization, which would have incalculably amplified the story’s power, effectiveness, and, yes, heart.

If that sounds like something you’d like to accomplish in your own story, let’s take a look at just how to make it happen.

How to Choose the Right Plot Points for Your Story

This almost rhetorical question gets bandied about a lot by the writing intelligentsia. There are many, many responses, because plot actually remains a surprisingly abstract concept.

But here’s my answer for today.

Plot is pacing.

From a certain perspective (said in best Obi-Wan voice), structure is about nothing more or less than controlling a story’s pacing for optimal entertainment value.

(And since we’re defining stuff, let’s define “entertainment” for what it really is: “emotional impact.” If you want to keep your audience’s attention—aka, entertain them—then you’ve got to engage them personally and primally. Obviously, there are varying levels of this—everything from mildly funny jokes to life-changingly empathic experiences. But the principle remains the same: engage the emotions.)

What this means is that each structural beat—particularly, the major turning points at the First Plot Point, Midpoint, and Third Plot Point—should be designed to control pacing in order to create the optimal emotional effect upon audiences.

But this only works when the author understands and utilizes these structural beats properly.

What Happens When You Choose the Wrong Plot Points?

Here’s a quick overview of how Outlaw King is structured (and therefore paced):

Hook: The Scottish lords, including Bruce, unhappily surrender to King Edward I of England and swear fealty.

Inciting Event: The timing tells us the Inciting event is Bruce’s marriage to Edward’s goddaughter. But the true Inciting Event is the riot he witnesses when Wallace’s dismembered arm is displayed publicly.

First Plot Point: Bruce appeals to his rival for the crown, John Comyn, to help him fight the English. Comyn threatens to betray him, and Bruce murders him. Bruce is subsequently crowned King of Scots.

First Pinch Point: The English treacherously attack Bruce’s camp the night before an agreed-upon battle. His followers are slaughtered, and he is forced to go on the run.

Midpoint: Bruce flees to Ireland, while his wife and daughter are imprisoned and two of his brothers killed.

Second Pinch Point: Bruce finally returns to Scotland and starts taking back some of the castles, which spurs the English to pursue him with promises of no quarter.

Third Plot Point: Bruce and his followers prepare their first pitched battle against the English—at Loudoun Hill.

Climax: They enter battle.

Climactic Moment: They are triumphant, and the English retreat.

Resolution: Bruce wins, his family is returned to him, Scotland is free (as summarized in subtitles).

So what’s wrong with this picture (other than the messy Inciting Event)? At first glance, it might seem like everything’s in place, but the single biggest problem is that the structural beats get weaker and weaker and weaker as the story progresses, instead of growing stronger and more powerful.

Whereas the Midpoint should be the single greatest turning point in the entire story—shifting the protagonist from reaction to action—here, the protagonist’s actions are almost passive; he won’t actively regroup until another eighth of the story has passed. And when the Second Pinch does arrive, Bruce’s return to Scotland and immediate triumph in regaining his own castle seems to be almost taken for granted by the filmmakers.

This isn’t, however, a problem that starts with the story’s Midpoint. Rather, this is a problem that originates in a poor choice of structural beats and a correlated poor control of pacing.

Don’t Know Where to Begin Choosing Your Plot Points? Start at the End

The events of Bruce’s life, post-Wallace, create a naturally compelling three-act story: his decision to claim the crown and rebel, his exile from and return to Scotland, his hard-fought triumph.

On the surface, that’s exactly what this film gives us…. except, inexplicably, it cuts out Bannockburn. As anyone familiar with Scottish history knows, the Battle of Bannockburn was the finale of Bruce’s triumphant story.

The Battle of Loudoun Hill, which ends the movie, was only the beginning of his eventually victorious campaign against the English, and as such, it feels rightfully anticlimactic.

Honestly, I’m agape at how anyone could decide, Hey, we’re going to tell a story about Robert the Bruce—and NOT end the story with Bannockburn. It’s like deciding to write about the Battle of Stirling Bridge without Stirling Bridge. (Oh, wait…)

From a structural point of view—and, therefore, a dramatic point of view—Bannockburn is the obvious point of the story. It’s the single structural moment that is tailor-made for this story’s Climax. (More than that, it is astonishingly cinematic, not least in Bruce’s opening duel against Henry de Bohun, a gambit historically celebrated as one of the most impressive instances of single combat.)

Understanding Bannockburn’s appropriateness for the Climax reveals an entirely different and better-organized structure for the story.

Let’s take a look at how this story’s plot points might have been rearranged and strengthened for a more powerful overall effect.

Hook: The Scottish lords, including Bruce, unhappily surrender to King Edward I of England and swear fealty.

This is still a good choice for the opening scene. It’s clearly the first domino in the events of the conflict to follow; it begins the story in medias res without omitting anything important; and by starting after the demise of the famous William Wallace, it squarely centers this as Bruce’s story.

Inciting Event: Bruce witnesses the public display of Wallace’s dismembered arm and the subsequent riot.

The Inciting Event is the moment that defines the entire story to follow. As such, its timing is important. By delaying this scene until almost the quarter mark in the story (crowding it up against the First Plot Point and the end of the First Act), in favor of Bruce’s awkward relationship with his new wife, the film muddied its throughline. Is this a story about Bruce and Elizabeth—or Bruce and Scotland?

There is absolutely nothing wrong with emphasizing and developing a relationship subplot (indeed, I’d argue Elizabeth’s scenes end up being the most interesting and compelling of the story), but not at the expense of the story’s cohesion. A story’s major structural moments create its backbone and, as such, must be unified.

This is where timing becomes an important part of pacing. Readers and viewers instinctively respond to the timing in a story. When story requires nearly a quarter of its length to get to the Inciting Event, its focus muddies.

Key Event: Were this my story, I would have tied the timing of Bruce’s murder of Comyn in more tightly with the Call to Adventure (above). In a busy story that covers a lengthy period of time, there isn’t space to waste. By tightening up the First Act to provide better timing for the Inciting Event, this far more consequential scene with Comyn could be given more weight, leading directly to the First Plot Point when…

First Plot Point: …Bruce is crowned king—and immediately goes to battle against the English, who treacherously attack his camp the night before the agreed-upon battle. His followers are slaughtered, and he is forced to go on the run.

Now that the set-up of the First Act is complete, we have reached the story proper: Bruce’s fight against the English. And since we’re just now entering the Second Act, we still have plenty of time in which to explore and develop the main conflict.

First Pinch Point: The first half of the Second Act is all about the protagonist’s reactions to the consequences of the First Plot Point. This is where he will struggle—futilely, as often as not—to regain his balance.

This, of course, means this section of the story would be the perfect place for Bruce to feel the full impact of his choices, leading up to a First Pinch Point when he goes into exile in Ireland for the winter, knowing he has left his family and his country in devastation behind him.

Midpoint: Now that we’ve accomplished a tighter first half of the story, we have the time and the space to leverage a truly important moment for the story’s centerpiece: Bruce’s return to Scotland.

This event is a tremendously important moment in both the story’s plot and its character development. As such, it deserves to be developed from the inside out. In addition to providing the protagonist a swivel point from reaction to action in the exterior plot, the Midpoint should also function as a Moment of Truth within the character’s interior arc.

Unfortunately, this was a tremendous missed opportunity in Outlaw King. As a historical figure, Robert the Bruce presents an almost perfect character arc—from a shilly-shallying political opportunist to an all-in king of his people. But the film doesn’t even touch that. Had it spent its opening scenes more wisely in setting up the foundation for Bruce’s inner evolution from Lie to Truth, it could have added depth and meaning to its otherwise straightforward account of medieval brutality.

The film sends Bruce back to Scotland (at the Second Pinch) with no more dramatic grist than a grim face and a little patter from his buddy about the efficacy of vengeance. How much better to mine this moment as a personal sea change? What might have started for Bruce as his one shot to grab the crown has suddenly become eminently important on a deeply personal level. (Is that how it went for the real Bruce? Maybe, maybe not. But telling a story means telling a story.)

Second Pinch Point: And finally we come to the proper place for the Battle of Loudoun Hill. Here, Bruce sets up for his first battle against the English. He is just now starting to stick it to his enemies. He wins, but he feels the pinch as he suffers great losses (the death of his young vassal arguably works even better here, since it only raises the stakes for what is yet to come).

Third Plot Point: So many action movies these days either skip the Third Plot Point or use it simply as a turning point into the beginning of their final climactic battle. Again, it’s a timing issue: they want enough time to pull off at least a twenty-minute epic battle. But in skipping or glossing over what should be one of the most impactful moments in a story, they almost inevitably gut their stories’ emotional impact.

The Third Plot Point represents the “dark night of the soul” for the protagonist. Even if what happens here isn’t literally the worst thing that happens in the entire story, it is an event that prompts the protagonist to reconsider his actions—and, just as importantly in a Positive Change Arc, his devotion to his newfound Truth.

Without this moment, the power of the character’s willingness to make sacrifices for that Truth (thereby proving the true scope of his personal change) lacks all teeth.

In plotting my own stories, I don’t pull punches with major plot points, including the Third Plot Point. Always, I try to create an event for this structural moment that is suitably impressive—something that at least symbolizes death, since that is what is represented here for the protagonist’s inner journey, as he once and for all dies to the old Lie-driven self and steps consciously into the Truth-surrendered self.

However, even just a deep moment of personal doubt experienced by the character on the eve before battle is better than nothing. At least pay heed to the emotional downbeat needed here before the rise into the final confrontation of your Climax.

Climax: In Outlaw King, that Climax should have been the Battle of Bannockburn. Because with the finality of this battle, the story, too, reaches its looked-for end. The war is won. Scotland is free. Bruce is king.

Resolution: When you end the story where it belongs, you have no need to sum up all the good action in a few quick subtitles at the end. Instead, you can focus on a scene that demonstrably shows how the character—and his world—has been changed by the story’s events.

***

Although Outlaw King‘s historical background provides easy examples to draw from in reorganizing its particular structural challenges, the same principles apply when you’re writing straight-up fiction. In fact, when you have total control over your plot and characters, you have even more leeway (and, I would argue, more responsibility) for creating dynamic and well-organized structures.

Start looking for the most important and impactful moments in your story—and mindfully make the most of them by placing them each in the right place at the right time in your characters’ personal journeys.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How did you choose your story’s plot points? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/plot-points.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Choose Your Story’s Plot Points appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 12, 2018

5 Ways to Successfully Start a Book With a Dream

Don’t start a book with a dream.

Don’t start a book with a dream.

This has become one of those bits of writing advice that has passed into legend, right along with “show, don’t tell” and “write what you know.” There are so many good reasons for this.

Dream openings are notorious for being boring, irrelevant, misleading, and cliched. As a “fake” opening, dreams share many of the same challenges and pitfalls as regular prologues—and have received the same amount of pushback from agents and editors weary of seeing the same problems over and over again.

Of course, unpublished manuscripts (and even published ones) keep churning out dream-sequence openings just because they always have the potential to be so much fun.

There’s a reason writers absolutely love them, and it’s usually because they first loved dream sequences as readers.

We all understand the inherent drama and symbolism of a good dream sequence. We all shiver with delight with the impactful foreshadowing handed down through these harrowing journeys into the subconscious. In fact, dreams have become a trope all their own: just as we know characters are death-bait if they start randomly coughing, we can also count on the delicious doom foreboded by characters who dream.

Right? I mean, seriously, I’d ask you to raise your digital hand if you’ve ever written a dream sequence, but then we’d all be raising our hands. I’m writing an entire series about dream sequences (which always makes me feel a little sheepish when I then proceed to adamantly recommend authors not start a book with a dream).

What this tells us is that there’s obviously a lot of good storytelling juice inherent in dreams. But as we also already know, adding a dream to a book (especially trying to start a book with a dream) isn’t an easy recipe for success. There are more ways to do it wrong than right.

But.

It can be done.

Learning From Each Other: The First WIP Excerpt Analysis

This brings me to the first installment in our series of Work-in-Progress Excerpt Analyses. Last month, I prompted the idea of an intermittent series of blog posts, in which I would analyze short excerpts from your works-in-progress, with an eye toward identifying and discussing particular techniques we could all learn from.

You guys floored me with your enthusiastic response. I’m currently planning to do probably one analysis post per month, and considering that I now have an email folder filled with over two hundred submissions, it’s safe to say we’re not going to run out of material anytime soon.

Today’s post is inspired by Jennifer Sutherland’s submission of the opening to the second chapter of her fantasy novel The First Goddess. She wanted to know if she succeeded in her use of a dream sequence to introduce a character:

I have two protagonists in my story. I know that a dream sequence is a no-no for an opening scene, but is it always a bad idea? I’d like to introduce my female protagonist in chapter two with something like the following.

Jennifer’s submission immediately popped out at me as a great learning opportunity, both because this is a hot topic, and also because she demonstrates how to successfully start a book with a dream.

Her excerpt:

Snow was falling. The soft flakes cascaded all around us, catching on my eyelashes while I stared up at the tall man before me. Clad in a sleek, red suit, he was as stark against the snow as a drop of blood on white parchment. He considered me with murky, bloodshot eyes and I shuddered, glad for my mother’s firm grip on my hand.

“Janie, don’t let go,” she said, and pulled me closer to her side.

“Why,” I asked, only to realize that no sound emerged when I spoke. Were I to let go, there would be nowhere to run anyway. Nothing but snow covered terrain surrounded us for miles. A sudden touch, something colder than the snow, made me jump. I whipped around to find the man reaching for me with hands wrapped in a swirling pattern of delicate, black tattoos.

My mother yanked me away and said, angrily, “We had a deal.”

The man angled his bald head and smiled, displaying perfect, porcelain teeth. His reply whispered from his lips like moths rustling dry leaves. “A deal requires the participation of all parties involved. You,” he emphasized the word, “have not upheld your end of the bargain.”

He looked at me again. Those putrid orbs bore into me and the scraping, fluttering sound returned. It intensified to a roar, drowning out whatever he’d been about to say.

I awoke suddenly, the familiar noise still echoing in my ears. Cold, hard rain pelted me from above and I squinted as it struck my face. Grass encompassed me, looming so high that it obscured the sky and my view of the immediate area. A tangy scent of blood drifted in the air and I sat up cautiously, worried it might be my own.

Or my brother’s.

“Jason,” I called softly.

My body was unharmed, other than a few cuts and scrapes. My clothes, however, were torn in several places and soaked in frigid, muddy water. They clung to me as I stood, weighing heavily on my arms and legs. Height was not a gift my parents’ gene pool had bestowed upon me, so I could barely see over the colossal plants around me. Peering through the wispy ends of the blades, I could make out the edge of a forest less than a quarter mile away on my right.

Hugging myself for warmth, I turned full circle in my little patch of flattened grass, looking for the highway we had left earlier. But there was no road in sight, only the long line of the forest extending into the horizon. Any other landmarks that may have been present weren’t visible through the deluge of water and towering foliage. There wasn’t even a trail of broken stalks around to denote where I had come from. As though the sky had dropped me there with the rain.

What an excellent deduction Jane. The sky is raining people.

“Jason,” I said a little louder. There was still no response. Shivering, I continued to glance around, alarmed that there was no sign of him.

The plains were as isolated as the snowy hills of my dream.

5 Ways to Make Dream Openings Work

The major complaints against starting a book with a dream usually center around dreams that lack drama, structural integrity, or pertinence. Too often, authors will slap a dream onto their opening, believing the very nature of the trope makes it an insta-hook. The inevitable revelation, halfway through the scene, that “ta-da! she was dreaming” seems inherently gripping.

But it’s not. Readers don’t care that a character is dreaming—especially in the beginning when they don’t yet have any context. More than that, readers don’t want their time wasted in that first chapter, when what they’re really wanting is to get straight to the meat and discover whether or not this story is going to offer them something worth their time

>>More Here: Your Ultimate First Chapter Checklist

In short, authors must earn their dream openings. You can’t just slap a dream onto the beginning, believing it possesses some special power to hook readers, then blithely power on into the “real story.” Instead, you must carefully craft your dream—as Jennifer has—into the single best introduction of your plot and character.

Here are the five top signs you’ve chosen to start your book with a dream that works.

1. The Dream Isn’t Really a Dream

You know those fictional dreams that actually are exciting to you, as a viewer or reader?

I’m talking about scenes like Luke Skywalker facing down Darth Himself in the cave on Dagobah, or Jane Eyre watching a ghostly aberration rend her wedding veil in the middle of the night, or Jason Bourne jolting awake from another nightmare of assassinating someone.

They’re not dreams at all. They’re visions, premonitions, realities, and memories.

Real dreams are random and vague and largely meaningless to the conscious mind. Last night, I dreamed I was attending a chipper family reunion that was calmly dispersing because the meteorologists were predicting the descent of an apocalyptic windstorm.

Now, if it turned out, later in my life story, that I attended a family reunion under the threat of Hurricane Armageddon, then, yeah, that dream might be pertinent. But I’m betting not and filing it with all the rest of my crazy night ramblings.

That’s fine for me in real life. But it’s not okay for characters on the page whose every moment must contribute to the story’s larger structure and meaning. Dreams in a story are a promise to readers that this matters. That alone is why they offer the potential to be great hooks. They are power-packed foreshadowing.

But their foreshadowing only works when used with consciousness and purpose—as Jennifer has. Although I haven’t read the rest of her story, I trust that her sleek, red-suited man with the swirling tattoos is either a direct memory for the protagonist, a transferred memory or vision from her mother, or a premonition of something yet to come.

In short, it’s a clue to this character’s entire existence within this story. It’s not just a dream. It’s not just a random nightmare. It’s pertinent. It has given readers information they both need and crave.

2. The Dream Is a Great Hook

Just coming up with a foreboding or interesting dream that hints at good stuff to come is not, in itself, enough to hook readers.

You must also frame it as dramatically as possible. There are two specific elements to this.

1. Make the Dream Ask a Question

Hooks are questions. They introduce discordant elements that pique readers’ curiosity. The most interesting question in all of fiction is: Why? Why is this happening? Why does this matter? Get readers to ask these questions, and you’ll almost certainly hook them into the rest of your story.

2. Make the Dream Visually Arresting

In my post “Don’t Write Scenes–Write Images,” I quoted Pulitzer-winner Jane Smiley’s insightful observation that “ultimately … images are” what’s most “important and enduring” in written fiction. The principle of “show, don’t tell” is arguably nowhere more important than in your opening chapter and especially if you’re opening with something as visceral as a dream.

In her excerpt, Jennifer accomplished both of these challenges. She uses the dream sequence to raise several questions without answering any of them. Readers understand that if they want to find out what’s going on, they must keep reading.

Furthermore, Jennifer has created a evocatively visual scene. Her well-chosen descriptions of color and detail—the man’s swirling tattoos and the antagonistic snowfall—paint a picture that pops. Readers will remember this scene when finally they get to the payoff that fulfills their curiosity.

3. The Dream Is Followed By a Second Hook

The fundamental problem shared by dream openings and prologues is that they are essentially “false beginnings.” Because a dream’s events exist outside the story’s immediate plane of reality, whatever hook the dream provides is necessarily not the story’s “real” hook. That comes later when the dreamer wakes up in the real time of the main story.

What this means is that the story must essentially begin twice. And what that means is you’re going to have to write two hooks.

Transitioning from a dramatic dream sequence to the protagonist lying in bed thinking about the dream does not create a strong dramatic throughline for your opening chapter.

Again, Jennifer does a great job with this. She transitions smoothly from the eerie menace of her opening dream to the logical follow-up hook of the protagonist groping through her disorientation and fear. The character is not safe in bed with her family around her. Instead, she finds herself in another strange and curiosity-inducing environment, clearly on the run for unknown (but, we assume, related) reasons with her little brother, who may or may not have just disappeared on her.

4. The Dream Creates Plot

One of the major reasons dream sequences often fail is that they don’t move the immediate plot. Opening with a visceral dream that foreshadows delicious things to come isn’t enough if that same dream isn’t immediately pertinent to the character’s choices and reactions in that same scene.

Later on in a story, it’s possible to use dream sequences that influence their scenes tonally, rather than causally. But in your opening chapter, you’ve got to hit a lot harder. There needs to be an immediate causal link between the pertinence of the dream and whatever happens next in the real-time story to set up the plot to follow. Otherwise, the dream just isn’t pertinent enough at this moment to provide the strong opening hook you’re looking for.

By linking her two hooks—the dream itself and then the disorientation of waking up—Jennifer demonstrates one way to use dreams to move the plot. The character is directly influenced by her dream—it wakes her up and it motivates her to check on her brother. Assuming both of these actions are important to what follows in the rest of the chapter, this provides a solid structure to this opening.

Another way in which a dream might actively influence the “real” story is by providing information that turns the plot. Presumably, what Jennifer’s character learns in this dream will be a clue that factors into the story later. But had she wanted to, she could also have used it to provide her protagonist with a revelation that informs her immediate actions—which, again, would ground the dream’s pertinence in this scene.

5. The Dream Doesn’t Lie to Readers

This is the trickiest dream “rule” of all. Most of the time, dreams open with no hint that what the character (and the reader) is experiencing isn’t real. But this is a two-edged blade. On the one hand, it ups the ante of the dream’s events and can sometimes allow authors to create spectacularly fanciful hooks (there’s no gravity! the protagonist has magic powers! the protagonist’s dead parent is speaking to him!). But on the other hand, it also opens with a promise to readers that they’re getting a story about one thing—only to immediately break that promise.

I’ve been grabbed by many a great opening sequence, only to realize a few paragraphs later that the story wasn’t anything like what it had originally seemed to be about. “She woke with a start” is one of my least favorite lines to find in an opening chapter.

Personally, I find it much more advantageous to immediately tell readers that what they’re experiencing is a dream. Doing so kills almost none of the suspense, while helping shape readers’ expectations for the real story to follow. I opened my portal fantasy Dreamlander with the line:

Personally, I find it much more advantageous to immediately tell readers that what they’re experiencing is a dream. Doing so kills almost none of the suspense, while helping shape readers’ expectations for the real story to follow. I opened my portal fantasy Dreamlander with the line:

Dreams weren’t supposed to be able to kill you.

I wanted readers to immediately understand that the events to follow weren’t literally happening to the protagonist (or… were they?).

Jennifer’s excerpt does break this “rule.” The consequences are not egregious since she clues readers in pretty quickly. Most readers will adjust easily, especially since Jennifer follows up the dream’s hook with a credibly strong hook in the main part of the story. Still, were this story mine, I would find a way to hint within the first paragraph that this is a dream.

***

As with many of the “always/never” rules in writing, “don’t start a book with a dream,” is an oversimplification. It’s a reaction to the many, many, many poorly crafted dreams, most of which are written in the mistaken belief that dreams are always inherently interesting.

That said, it is a rule you can break, as long as you do it carefully—with respect for your readers’ reactions—and consciously—with a total understanding of your story’s needs and the effect you’re trying to create.

My thanks to Jennifer for sharing her excerpt and question, and my best wishes for her story’s success. We’ll do another analysis post in a couple weeks.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever tried to start a book with a dream? How did it go? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/start-a-book-with-a-dream.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 5 Ways to Successfully Start a Book With a Dream appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 5, 2018

When Writing, How Do You Know When Enough Is Enough?

Last month, I invited you to tell me what topics you’d like me to write about. You flooded my inbox and comments section with suggestions. (I scheduled this as an “easy” post that wouldn’t require much maintenance while I was in the midst of the a big move. When I logged on that first day to over a hundred comments needing to be approved, I was all, Wha? Gah— Ahhh!)

Last month, I invited you to tell me what topics you’d like me to write about. You flooded my inbox and comments section with suggestions. (I scheduled this as an “easy” post that wouldn’t require much maintenance while I was in the midst of the a big move. When I logged on that first day to over a hundred comments needing to be approved, I was all, Wha? Gah— Ahhh!)

I’m psyched by your enthusiasm—and excited to have such a deep well of ideas to draw from for future posts. So, first off—thank you for contributing to the discussion!

And, second, let’s get started…

How Do You Know When Enough Is Enough?

One of the first questions in the queue to catch my eye was Karen Keil’s:

My biggest issues have to do with the term “enough.” How do I know when I have described enough, not described enough, edited enough, not edited enough, dialogued enough, not dialogued enough, been humorous enough… etc.

One of the most difficult things about the art form of writing is how… unquantifiable many aspects are.

What is story but a great big blast of colors and feels right smack in your face?

As a reader or viewer, you just know when something works or it doesn’t. (Lack of artistic credentials has never been—nor ever should be—enough to hold anyone back from passionately loving or hating a piece of art). Explaining the why of any particular technique’s success or lack thereof is much harder. Indeed, even identifying which particular technique is at play sometimes seems like trying to figure out what the elephant is by poking at it in the dark.

Although story is a hugely complicated beast, made up of thousands of tiny individual pieces, it should never look that way. Or at least not when done well. When done well, a story just seems like… a story. It’s cohesive, every piece and every technique flowing effortlessly into the next to create, not a mosaic, but a living photograph.

That’s the beauty of art.

Perhaps not surprisingly, it’s also the very thing that causes huge pain points for the artist.

We must learn to deconstruct the living photograph into the individual pixels that create it. Otherwise, we will never be able to identify what’s gone wrong when one of the colors is incorrect or over-saturated or blacked out.

This is particularly pertinent when it comes to questions of what is “enough” in any aspect of your story.

The reason this is a difficult problem is the very fact that it is so abstract. There are no concrete answers. What might be enough description or dialogue in one section of the story will not be enough in another section. Learning to understand when enough is enough in your story is largely a matter of refining your storytelling instincts to the point where you can just feel whether something is too sparse or too excessive.

So how do you learn to refine those instincts? What that question is really asking is: How do you take your vague, sometimes-hard-to-access feelings about your story and turn them into a conscious understanding based on quantifiable parameters?

Ultimately, that’s what the entire pursuit of story theory and technique has been about for me. You could argue that the entire body of work I’ve created in this blog and my how-to books has been my effort to answer that question. But today, in response to Karen’s question, let’s specifically look at ways you can quantify when you’ve done “enough” in the four sections she’s highlighted.

1. How Much Description Is Enough?

Why not start with the toughest one first, right?

Finding that sweet spot between “too much description” and “not enough description” is a tricky one for many writers. Most of us start out info-dumping descriptive details like a garbage truck the day after Christmas. We want readers to see everything we see: every room of the character’s childhood house, every freckle on the love interest’s nose, every piece of clothing in the protagonist’s warrior ensemble.

But then somewhere along the line, a wise beta reader slaps us with the dictate to “trim the description.” So we overcompensate, looking for that one, right “telling” detail that pops the whole setting without requiring detailed descriptions.

And then… another beta reader tells us, “I can’t get any kind of sense of the setting these characters are supposed to be in.”

Gah. Maddening.

This seesawing between extremes is, however, an important part of honing those storytelling instincts. Learning to find the sweet spot of “enough” description is very much a matter of trial and error.

Last spring, I wrote an entry in the Most Common Writing Mistakes series about “Too Much Description.” In it, I wrote over-the-top examples of what “too much” description looked like. Then I went hunting for examples, from some of my favorite authors, of what the “just right” amount of description looked like. Ironically, many of their excellent descriptions actually ended up being longer than the egregious examples I created.

The lesson here is that “enough” description has nothing to do with word count. It has everything to do with pertinence; with finding the right details; and looking at settings, people, and objects through the strict viewpoint of the narration.

Know exactly what effect you’re trying to achieve in any given passage.

Is the whole point to introduce the setting? Well then, maybe you can get away with a chapter’s worth of description as Thomas Hardy famously did in

Return of the Native

(or maybe not).

Is the whole point to introduce the setting? Well then, maybe you can get away with a chapter’s worth of description as Thomas Hardy famously did in

Return of the Native

(or maybe not).Is the point to quickly enliven a walk-on character? Then a swift, well-chosen detail will likely suffice.

Is the scene focused on advancing the plot? Then opt for interspersing details throughout the scene, as the characters interact with them.

Study how your favorite authors utilize description. Even go so far as to copy out whole passages of their work. Description is rarely just dumped into a story one huge paragraph at a time. Most of the time, it is a living, breathing part of the story, interacting with every other part, sentence by sentence and even word by word.

2. How Much Editing Is Enough?

Now we take a temporary step back from the nitty-gritty of actual technique to look at the broader topic of how much time we should be spending on the story itself.

To me, the question of “when should I stop editing” shares the same pitfalls as the question of “when should I write ‘the end’?”

Lewis Carroll said it with appropriate gravity in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

Lewis Carroll said it with appropriate gravity in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said, very gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

In short, just as choosing when to write “the end” to your story is not an arbitrary decision, neither is choosing when you stop editing.

You stop editing when the story is finished—when there is nothing more to fix.

That might sound a little blithe. After all, most of us agree with Leonardo da Vinci that:

Art is never finished, only abandoned.

And it’s true. There is always something an author wants to change about a story. We are always growing, always learning—which means the totality of understanding we bring to a story on any given day will always be surpassed by what we have learned on the next. Plus, there’s the little fact that our intent always grows at a slightly faster rate than our ability to execute it.

Still, there are quantifiable ways in which to judge whether or not a story has reached a reasonable level of completion—in both the writing and the editing. For the most part, both approaches overlap.

There are two fundamental questions I ask myself to help me know whether I’m finished with a story or not:

1. Is the Story Structurally Complete?

The only way to know whether a story has reached its end—whether it is a complete whole—is to examine whether or not it is structurally cohesive and complete. When structure is observed, you never have to guess when it’s time to end a story—it just ends itself after the Climactic Moment.

2. Is There Anything Specific Left to Change?

Even after you’ve written/edited your story into a state of structural wholeness, you will very likely still find weaknesses to fix. A structurally sound story doesn’t, by any means, instantly qualify as a good story. You may still find yourself identifying any number of issues—everything from sloppy prose (too much/too little description, anyone?) to sloppy themes to ugly plot holes to ugly scene structure.

Don’t approach your editing like a street brawl: don’t just go in swinging. Have a plan. Consciously evaluate your story and make a list of all the problems you know need fixing. Then fix them. Then consciously re-evaluate your story. Make another list. Fix the problems on the list. And repeat. And repeat. And repeat. Until… there’s nothing left on your list.

Once you’ve got an empty list, you’re done editing.

But what if your list never empties? After all, if there’s no such thing as a perfect novel, there will always be more imperfections to address.

Two things.

First off, differentiate between things you think might be a problem with the story (aka, heretofore unsubstantiated doubts) and things you know are problems. Having doubts about a story is not the same as identifying specific problems that need to be addressed.

Second, know when to cut loose. Maybe you’ll never reach the very end of that list of edits. But there will come a time when you get close enough that it counts. For this, I like deadlines. I tell myself I have five years, from outline to final edit, to get a story right. If it’s not right by then, it’s time to cut loose and move on.

3. How Much Dialogue Is Enough?

I’d like to say there’s no such thing as too much dialogue—because personally I adore dialogue. But the more accurate approach to the proper amount of dialogue is different, if just as simple.

Dialogue becomes too much at the exact moment it isn’t pertinent to the story.

Often, authors will “write their way into dialogue” in order to figure out a scene or a conversation as they go. Dialogue is exceptionally characterizing, so feeling your way through a dialogue section may also be a (great) way of learning about who your characters really are, from the inside out.

This is is all fine and well in the first draft. But meandering conversations that only gradually find their way to a point—or, just as faulty, conversations that exist just for the sake of conversation—are always going to be problematic.

Just as you should examine every single sentence of narrative to make sure each one contributes in its own right, so too you should also examine every line of dialogue. If it contributes—either by advancing the plot, developing the character, or revealing important information—then it belongs. If not, it’s too much.

One of an author’s most important (and, in some ways, most difficult) jobs is being able to identify the purpose of each word in the narrative. Once you learn to do this, it becomes easy to identify which ones belong and which ones do not.

4. How Much Humor Is Enough?

My response to humor is kinda like my response to dialogue: no such thing as too much, right?

Except that, too, is facetious. Really, what I’m responding to is the element of entertainment both dialogue and humor bring to story. I do dearly love to be entertained.

If your humor is entertaining (i.e., it works), then you’ve already aced its primary reason for existing.

Beyond that, humor shares other qualifiers with dialogue in that it must be pertinent to the story. Funny can’t exist just to be funny. It must offer resonance and contribute to cohesion.

But do you need humor?

I honestly can’t think of a single story that can’t benefit from a meaningful inclusion of humor at appropriate moments. But humor, perhaps more than any other element of story, must flow. You can’t force it. It must arise from the situations and characters you’ve already created.

Whenever you have the opportunity to include humor, go for it. But if those opportunities aren’t arising, don’t worry. However entertaining humor may be, it’s not a prerequisite to an amazing story. There’s many a great story out there that cracks nary a smile.

***

Know what effect you’re trying to achieve in your writing and stick to that with confidence. The “enough” you’re seeking will always find its balance when you’re able to realize your intended effect. If, by the story’s end, you’ve succeeded in creating that effect, then your story is “enough.” If not, it’s time to go back and figure out whether you’re missing the mark because you’ve included “too much” or “too little” of any of the above elements.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you struggle with knowing when enough is enough in certain areas of your writing? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/enough-is-enough.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post When Writing, How Do You Know When Enough Is Enough? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 29, 2018

5 Lessons From a Lost Novel

Mistakes are unavoidable. To fear them is to fear life itself. To try to eliminate them is to waste life in a futile struggle against reality itself.

Mistakes are unavoidable. To fear them is to fear life itself. To try to eliminate them is to waste life in a futile struggle against reality itself.

I daresay no one has more opportunities to learn these truths than does a writer.

As writers, our lives are a never-ending litany of mistakes. Certainly mine has been full of mistakes—everything from the opening sentences I wrote for this post, thought better of, and replaced—to literally hundreds of thousands of deleted words I’ve carefully saved from all my rough drafts—to entire story ideas (representing hundreds of hours of dedicated, hopeful work) that have proven themselves unsalvageable and earned a dusty place in a back corner of a closet shelf.

I won’t say I don’t regret these mistakes. I do. I regret the wasted time and effort. I regret the bereavement of loving and nurturing something that never came to fruition. I regret my own lack of foresight, wisdom, and understanding in failing to see pitfalls before I walked into them.

If I’m being really honest I’ll have admit that, given the chance, I’d probably take back every single one of those mistakes.

Fortunately, however, that is one mistake that the very design of life will prevent any one of us from every making.

I can’t take back my mistaken words, ideas, and stories. And in being robbed of the chance to exercise my own foolish desire to do so, I am instead given the priceless gift of being able to learn from those retained mistakes.

Learning From Our Mistakes

Learning from mistakes is unavoidably natural. Even when we’re not consciously aware of the lessons we’ve absorbed from false starts, we have absorbed them. Whatever the mistakes we make in the future, they won’t be the same ones we’ve made in the past, whether or not we avoid them purposefully.

However, sometimes we will be able to consciously review mistakes at a later date. When this happens, we are essentially getting the chance to go back in time, revisit the cause and effect of earlier mistakes, and intentionally learn from them.

Again, I daresay no one has more opportunities to do this than does a writer—since our mistakes are recorded forever in black and white.

A few months ago when writing this post on the advanced principles of show versus tell, I was feeling too lazy to write up brand new examples of “showing,” so I mined an old failed story. In so doing, I was drawn back to re-read the whole thing.

This book, titled The Deepest Breath, was a story of vengeance and forgiveness set in post-World War I Kenya. Since the start of my career as a published author, it is the only novel I have finished and then abandoned—a decision I used as the basis for this post talking about three valid reasons for giving up on a story.

Re-reading this book after having grown and changed significantly as both a writer and a person was an eye-opening experience. The reason I gave up on the book back then was that I could sense its problems, but couldn’t quantify them in a way that would allow me to fix them. Now, five years after abandoning it, I can see both what was wrong and what was right about the book.

The mistakes I made then were made because I had not yet learned what I needed to know in order to avoid them. They were honest, earnest mistakes, born of the struggle to understand. Ultimately, they were mistakes that, however painful in their seeming fruitlessness at the time, were the very mistakes that taught me what I needed to now see clearly.

Some of these mistakes were unique to the story itself. But some are, I feel, universal mistakes that many struggling novelists make—and instinctively recoil from without yet knowing what exactly the problem is or how to fix it.

Today, I would like to look at five of the mistakes I made that ultimately contributed to The Deepest Breath becoming one of my “lost” novels, how I could have avoided those mistakes had I known then what I know now, and how you can learn from my mistakes.

5 Lessons You Can Learn From My Mistakes

Looking back, I’d almost argue that The Deepest Breath was the one novel, out of my novels, that I worked hardest on. I outlined and researched the heck out of it. It went through many iterations. In fact, to all intents and purposes, I wrote it as three separate and distinct novels along the way.

Originally, I intended it as a dual-timeline story with the three main characters’ “present-day” story in 1925 Kenya juxtaposed against their dark backstory during World War I. I initially decided to write the entirety of the war section first, with the intent of then interweaving it throughout the “main” story (an approach I would now adamantly reject, due to its inherent problems with organic flow between timelines).

After realizing that wasn’t working (based mostly on the epiphany that the backstory had some major causal issues), I decided to scrap the idea of dramatizing the backstory and instead just focus on the main story—about the fallout in the relationships among two men who had met in World War I and the woman they realized they both loved. I wrote one iteration (in the present tense), realized it was a mess, and rewrote it extensively in another draft (in past tense).

Along the way, the book improved dramatically. But despite all my years of work, I eventually realized it was still broken—and I had no idea how to fix it.

Now, looking back, I can see that it actually ended up being a pretty good story. There’s a ton I like about it. In some ways, I think it’s the best character piece I’ve ever written. The setting in Kenya is one of my best realized settings ever. The plot is quietly foreboding, the pacing moving slowly and yet with the power of a train hurtling toward an inevitable collision.

And yet… it didn’t work because at the time I wrote it, I didn’t understand enough about the fundamental principles of story to be able to ask myself the five following questions.

1. Who Is the Protagonist?

The Problem: The one unavoidably massive issue with this book was its pervasive lack of focus. Ultimately, it’s a story of a complicated love triangle. Each of the three main characters were equally important, and I chose to equally balance the story amongst their three POVs.

Nothing inherently wrong with that. But at the time I wrote it, I didn’t yet fully understand how story structure guides and creates a story’s focus. This showed up in several areas of this story, but most obviously in the fact that I clearly didn’t understand who this book’s protagonist was. And if I, as the author, didn’t know, then how were readers supposed to know?

But… couldn’t all three main characters be the protagonist?

That’s actually a question I’m asked frequently by writers in regard to their own stories.

What I understand now (and didn’t back then) was that the answer is an unequivocal no.

The Fix: A story’s structural unity is bound up in the relationship of important plot points to the protagonist. However prominent other characters may be, the protagonist is the one who ultimately defines the story.

How?

By providing a strong, consistent throughline. The structural beats tell us what a story is about. If the First Plot Point is about one character, the Midpoint about another character, and the Third Plot Point about still another—then this is a story that doesn’t know what it’s about.

So, in a story in which multiple characters are prominently important to the story, how do you decide which is the protagonist?

The best way of identifying your story’s “throughline” character or protagonist is by examining the Climactic Moment. Which character is the agent of action in the Climactic Moment? Which character definitively ends and/or comments upon the plot’s primary conflict? This character is the character who defines the story. This is the protagonist. This is the story’s linchpin. That must be reflected at every major structural point throughout the story. Otherwise, your story will fall into the same category as mine—a beautiful mess.

2. What Is the Essence of This Story?

Structuring Your Novel Workbook

The Problem: Too often, when a story’s structure is left undefined by a strong central character, the result is a correspondingly wobbly theme.

In my case, The Deepest Breath was actually a deeply thematic novel. What interested me most about it was its theme: of undeserved forgiveness. The title itself was a quote from the story’s climactic line when one character finally acted out that forgiveness on behalf of another.

So you’d think the theme would have been the one thing I got right.

Not so much.

At the time of writing that book, I was neck deep in learning how to grapple with the principles of structure. I hadn’t yet even begun to understand how to consciously actuate theme by purposefully creating cohesion between plot and theme at every important structural moment.

The result was a well-intentioned story that, although it may have had some great thematic moments and ideas, didn’t actually execute its theme on every page. Actually, it was kinda hard to tell what the story was really about. Was it about forgiveness? Was it about PTSD and fear? Was it about trust in relationships? Was it about striving against the confines of social class? Was it about love? Was it about friendship? Was it about justice versus mercy?

If I’d possessed a better understanding of how to create a cohesive thematic Truth against which to measure every aspect of my characters’ struggles, I could very well have written a story that unified all these ideas by pointing them toward the same end goal. Instead, I ended up with a story full of half-baked notions that seemed to be pointing in a dozen directions at once.

The Fix: Were I writing this story again today, I would start by forming my thematic idea about forgiveness into a definitive Lie/Truth for all three of my main characters. With so many prominent characters, I would have had the opportunity to explore multiple facets of my topic, but in a way that tied all their journeys into the tapestry of a larger picture.

This, in turn, would have given me a guideline against which to choose which subplots supported this thematic idea—and its ultimate realization in the Climactic Moment—and which distracted from the unified premise I was trying to create.

3. Is the Backstory Pertinent?

The Problem: Something I’ve noticed as I’ve grown up as a novelist is that when a writer doesn’t fully understand her story (or story in general), backstory has a way of trying to take over.

In the days before I understood how the structure of plot, character, and theme worked, I often spent an unwonted amount of time amassing huge backstories designed to help me try to understand what the main story—and the characters’ motivations within it—was really about.

Nothing inherently wrong with huge backstories. Indeed, they’re the deep wells from which complex novels draw their subtext. But backstory, like the main story, must always be focused and pertinent.

As I said before, I originally intended The Deepest Breath to present dual timelines that alternated between the characters’ past and present. Looking back, I realize this idea was mostly a crutch designed to try to help me flesh out character motivations I didn’t yet fully understand. The reason I eventually rejected this approach and axed the novel-length backstory section I’d already written, was that the backstory was a crazy mess of boring trench scenes and unrealistic spy thriller stuff that had very little to do with the main story.

The Fix: Backstory is always important. Even when it is not shared outright with readers, it will always influence the author’s understanding of the characters and their story. Therefore, it must be pertinent. It can’t be a fun, rambling romp through ancillary adventures. It must be the staging ground for the character’s journey through the main story.

From a structural vantage point, the backstory’s single most important job is that of setting up the character’s motivation for investing in the Lie/Truth that will be explored in the main part of the story.

I did understand this when I wrote Deepest. In fact, the whole point of the backstory was to create the Ghosts that would drive my characters in the main part of their story ten years later. Unfortunately, I got distracted and created a whole rambling mess of a backstory that detracted from the main story’s focus far more than it contributed. Had I this book to do over again, I would vastly simplify the backstory, focusing it less on all the stuff I’d researched about World War I, and more on the needs of the main story’s plot and theme.

4. Are You Clinging to “Ugly Darlings”?

The Problem: We write stories because at some point we fell in love with some beautiful kernel of inspiration. It’s only natural we wouldn’t want to relinquish that special kernel. And yet… sometimes as a story evolves, it evolves past its early inspirations.

Deepest got its start as a dream—the only story I’ve ever written based on a dream. I woke up one morning with a vivid memory of a man dressed in early 20th-century clothes, escaping with his injured wife on a passenger liner.

I loved that scene. I still love it. It’s incredibly evocative to me on both a sensory and an emotional level.

But I tried way too hard to keep that scene, exactly as I’d dreamed it, in the story.

The Fix: Perhaps the hardest part of being a writer is realizing that just because an idea is wonderful doesn’t mean it deserves to be written. The mark of all great stories is their cohesion and focus. Any element—no matter how organically beautiful–that detracts from the larger picture is an element that must be eliminated.

This principle gets harder and harder to enforce the more time and effort we spend on an idea. Axing an imagined idea is one thing; axing an idea you’ve spent perhaps years writing and rewriting and tweaking and fixing is a thousand times more difficult—not least because familiarity and propinquity cause us to lose perspective.

When I wrote this book, I had a hard time cutting elements that, at the time, felt like the whole point. Today, from a more distant perspective, I could dispassionately identify, chop, and rearrange for the story’s greater benefit.

5. Do You Truly Understand the Story You’re Trying to Tell?

The Problem: Stories are strange beasts. Sometimes the story we think we’re telling isn’t the story at all. Other times, we may understand what we’re trying to do, but get hung up on habitual techniques and approaches that don’t serve the art as well as they might.

Five years later, I recognize The Deepest Breath is an entirely different type of story from anything else I’ve ever written. It’s more character-focused, less plot-driven. It’s darker. It’s quieter. It’s more realistic, more literary.

I knew all of that, on some level, when I wrote it. And yet—I still tried to shoehorn it into my own familiar tropes of the heroic action-adventure genre. The story’s Climax, in particular, suffers from my mistaken attempt to take a hitherto subdued character story and funnel it into a shoot-’em-up finale.

The Fix: It often takes time and experience to recognize, but an author’s two greatest commandments are:

1. Know Your Story.

2. Trust Your Story.

Looking back, I didn’t trust my story—or myself—enough to let it be what it wanted to be. I feared its quietness, feeling it was too slow or too boring. However, in re-reading it, I was surprised to realize how strong and compelling the tension is throughout the book. Had I just trusted that in the beginning, I might have written a much better Third Act.

Again, this principle returns to the idea of cohesion. The point of any piece of art is the creation of an effect. We wish to have an effect on our readers, to leave them with a specific feeling or thought. To do this, we must consciously craft that effect at every stage of the story—bringing plot, character, theme, tone, setting, and pacing together into a unified whole, with each piece trusting the other to support it.

***

I know what you’re thinking. Now that I think I’m all old and wise and have figured out all of my book’s problems, I should go back and rewrite it, right?

Maybe.

Honestly, I’m just happy to have returned to what has been a somewhat painful memory and discover that, after all, I had not betrayed or been betrayed by this dear friend from whom I had parted on less than genial terms.

The Deepest Breath is not, by far, the worst thing I’ve ever written. But perhaps for that very reason, I do think of it as my greatest mistake. I doubt I will ever return to fix it; there are just too many new stories to write. Happily, however, every one of those new stories will benefit from the many, many mistakes I made when writing that particular novel.

So maybe it wasn’t a mistake after all.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you have any “lost stories”? What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned from them? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/lessons-from-a-lost-novel.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 5 Lessons From a Lost Novel appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 22, 2018

4 Things Writers Can Learn From Making a Movie

I’ve been a book editor and a writer for a number of years now. As an author, I have one published novel in The Listeners; as an editor, I’ve worked on more than seventy. I’ve written screenplays that were optioned but never made, and I’ve sat at book signings to which no one showed up. I’ve spoken at conferences to audiences full of aspiring writers, I’ve counseled authors, and I’ve taught high school students the craft of fiction.

I’ve been a book editor and a writer for a number of years now. As an author, I have one published novel in The Listeners; as an editor, I’ve worked on more than seventy. I’ve written screenplays that were optioned but never made, and I’ve sat at book signings to which no one showed up. I’ve spoken at conferences to audiences full of aspiring writers, I’ve counseled authors, and I’ve taught high school students the craft of fiction.

But this summer brought an experience I’ve never had before, and one reasonably likely never to happen.

This summer I saw the filming of my very first movie.

As my cryptozoological dramedy Ape Canyon now navigates its way through post-production, I find myself considering four important lessons I’ve learned through this process.

Ape Canyon co-lead Anna Fagan (Samantha Piker) in the foreground with members of the crew behind (Gabby Sturgeon on sound, alongside production designer Jari Neuman and, on a tree stump, gaffer Ty Gentner) during filming in the area of Roslyn, WA.

1. Never Abandon a Good Story

More than one member of the remarkable cast and crew of Ape Canyon asked me what it was like to finally see the production of something that had existed in my head for a year or two. I had to correct them: it’s been so much longer than that.

Ape Canyon is a screenplay I started thinking about in 2009. I started writing it in 2011, and writing it in earnest in 2013, completing it in 2014. I have a lot of other screenplays, and a litany of short stories I saw myself adapting into short films. I didn’t know Ape Canyon would resonate with director Josh Land and director of photography Victor Fink when I met them in 2016, and I sure didn’t know we’d be filming it in 2018.

If I’d let Ape Canyon go when it was just an idea or abandoned it after 2011, or if I hadn’t committed myself to finishing it in 2013, or if I’d forgotten it when it didn’t set the world on fire immediately in 2014, then I would never have had the experience of watching it come to life before my eyes.

Leads Anna Fagan and Jackson Trent (Cal Piker) in the lens of director of photography Victor Fink.

2. A Good Writer Must Be Agile

This is a lesson I preach to my clients in fiction and memoir, but it can be a tough one to put into practice. What I wrote in the Ape Canyon script was the film as I envisioned it—but it turns out films have budgets. And when you’re making an indie film, those budgets provide some limitations. It’s on you—and your team—to adjust on the fly and come up with ways to maintain the integrity of the story while remaining realistic relative to what you can actually do.

One particular problem area was the sequence in which protagonist Cal Piker (played, beautifully, by Jackson Trent) gets lost in the woods. In the screenplay, this happens during a storm. But you can’t control the rain. He falls into a rain-swollen river and nearly drowns, but that’s a major, costly stunt. So we lost the storm. We lost the river. Cal fell down a hill. (And Jackson, fortunately, was not injured.)

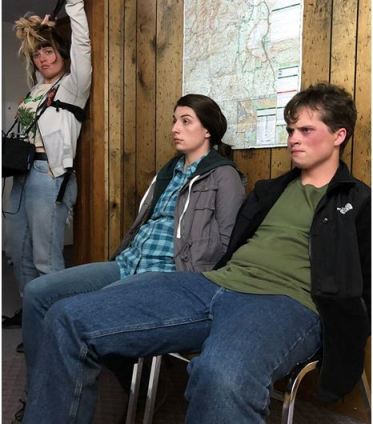

Though not badly injured, Cal has had a very rough couple of days. Anna and Jackson, with Gabby operating the boom mic.

The real tricky part, though, was the squirrel.

As written, Cal wanders into the woods because he thinks he hears Bigfoot. He realizes he’s lost after he discovers the true source of the sound: a squirrel, scampering away. It was virtually impossible on our budget to get a squirrel to scamper about the woods on cue—but equally impossible to control another animal, or a gust of wind, or whatever else might make a similar sound.

Josh suggested trash left in the woods. From there I proposed a bag hanging in the trees, as campers sometimes do to keep their supplies away from animals. Through some careful adjustments, we had a pretty great sequence—not the one I envisioned, but one that works just as well.

It wouldn’t have happened without Josh. That brings me to the third lesson.

3. Respect the Collaborative Process

Writing is frequently a solo act, but revision comes often with the creative input of others. Film compounds this, because film is all about collaboration. Without collaboration, and the teamwork of many creative people, there can be no film. This is one of the central ways in which the filming of Ape Canyon was unlike anything I’ve ever experienced.

We ran into another budget issue with the car chase scene. First we had to lose the chase. Then we had to lose the highway. Soon the car could hardly move at all. I tried to be agile. I wrote three alternative versions of this scene and did everything I could to make them at least almost as good as what I’d written originally. But I wasn’t happy about it.

I was there the day this scene was filmed—and I discovered Josh, Victor, and the rest of the team had done something amazing. They’d kept the dialogue and the arc of the most budget-friendly version of the scene, but they’d also sped it up, transforming it from sardonic to manic. It was a brilliant change because it maintained the energy of the chase within the confines of our limited budget. It wasn’t my idea, but it’s exactly what I would have written had I thought about it.

The Ape Canyon team films the reimagined no-longer-a-car chase. Left to right: director Josh Land, 1st AD (assistant director) Duncan Hill, 1st AC (assistant camera) Jessie Dubyoski, director of photography Victor Fink, and gaffer Ty Gentner. Unseen: Jackson Trent, hot-wiring the car.

That’s the magic of collaboration. There are lines in this film I didn’t write—lines the actors improvised or otherwise developed in the course of the filming that fit so perfectly even I couldn’t be sure they weren’t always there. And of course the entire visual element of the film is dependent on Josh and Victor and the craft they bring to what they do.

Part of the magic of watching a film come to life is in the fact that it’s not just you making it happen.

4. Embrace the Surreal

It’s hard to express the wonder I felt the first time I visited the set to watch actors playing characters that have existed in my head for, in some cases, nearly a decade. I experienced this first during auditions, hearing my words read by a variety of different performers with a variety of voices, but it’s different in the context of filming. The first time the majority of the cast was gathered on our campground set, seeing all the characters in the same place was like my own personal Avengers.

The majority of the Ape Canyon cast gathers around the campfire. From left to right: Donny Ness (Charlie), Lauren Shaye (Gina), Clayton Myers (Mark), Anna, Jackson, and Skip Schwink (Franklin).

But it’s not just the actors. It’s the locations. I wasn’t on set every day, but I would see photographs of settings and instantly recognize them from wherever they appear in the story. How do you recognize something you’ve never actually seen?

At heart, this isn’t just the wonder of filmmaking. It’s the wonder of firsts. Whatever new opportunity emerges to take your writing out into the world, even if it means entrusting your work to others, try it. Give yourself the opportunity to see your work in a brand new light. You’ll learn in the process that embracing the surreal can be one of the great joys of being a writer.

One of the last shots of the film: Cal and Samantha (Jackson and Anna) looking out over the beautiful Washington scenery.

Ape Canyon will surely have many more lessons to teach me as it develops into a finished film. I’m looking forward to it seeing it. It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been writing, or editing for that matter—there’s always something new out there. That’s what makes it so exciting.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What has been your most surreal moment as a writer? Tell me in the comments!

The post 4 Things Writers Can Learn From Making a Movie appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 15, 2018

Words Are Radical! (or, How to Cherish Language)

Years ago, I was hiking with someone around the Scotts Bluff National Monument in western Nebraska. A bird flew over our heads, black against a metallic July sky. A lover of all things beautiful, my hiking partner was the first to point it out.