K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 39

September 24, 2018

3 Tips for Improving Show, Don’t Tell

When looking for a new book to read, there are a couple quick tests I do to determine whether it seems like I can trust the author to know what they’re doing all book long. The first and most important of these tests usually requires just a quick glance across the first page to see whether the author demonstrates a grasp of “show, don’t tell.”

When looking for a new book to read, there are a couple quick tests I do to determine whether it seems like I can trust the author to know what they’re doing all book long. The first and most important of these tests usually requires just a quick glance across the first page to see whether the author demonstrates a grasp of “show, don’t tell.”

Show, don’t tell is one of the most basic principles of narrative fiction. Defined in a nutshell, it is the technique that allows readers to experience the events of the story, rather than observing them. Showing readers what’s happening involves active verbs that evoke all the senses. Showing invites readers to inhabit the context of the story with the subtext of their own imaginations.

Showing dramatizes.

This is in contrast to telling readers what happened. Telling spells things out as simply as possible. It doesn’t evoke a character’s joy. It just tells readers “she was happy.”

Telling summarizes.

Both showing and telling are equally viable and important fictional techniques. But the weight of a polished narrative should rest more heavily on showing than telling.

“The art of showing” is really “the art of narrative writing.” As such, it’s a technique all writers are constantly learning and refining. In the last year or so, I’ve learned some things about my own use of this technique that have helped me take dramatizing vs. summarizing to a better level in my own writing. That’s why, today, I want to talk about three ways you can up your “show, don’t tell” game.

What Show, Don’t Tell Really Means

First, a crash course.

“Show, don’t tell” is often one of the first critiques a fiction writer receives. Usually, the command is more than a little confusing. What does “show, don’t tell” even mean? You look at the passage your beta reader circled and you try to understand what’s wrong with the way you phrased it and how you could possibly have written it any other way.

Learning to recognize telling and differentiate it from showing can be a lengthy and sometimes less-than-intuitive process. I think many of us remember the moment when we suddenly got it and started recognizing telling in our writing and understanding how to rewrite it into more evocative showing.

Basically, the difference between showing and telling can be seen in the following:

Danny slogged through the tangled grass. Christopher marched along behind him, rifle in both hands, head up, eyes alert, just like his papa. Two or three times, Danny stopped to show him the buffalo tracks and the broken foliage the bull had torn up after his first shot.

vs.

The father and son were hunting a buffalo.

Both convey the same information. In fact, the second “telling” paragraph, conveys it much more efficiently (and therefore, would be appropriate in certain places in a story, for certain stylistic reasons). The second paragraph does not, however, show us what is happening. It does nothing to personify either the characters or the setting.

There are varied levels of showing. Part of the art of learning to write solid narrative is learning to consciously weave various degrees of dramatization into the story. Full-on showing at every juncture would drown most stories in unnecessary details (not to mention geysering their word counts). You will rarely, if ever, need to spell out every flinch of muscle involved in your character’s rising from a chair. There will even be times when your best option is to summarize whole swathes of action into a sentence or two.

But for the most part, all important events, actions, and feelings should be shown—dramatized. You want to paint word pictures for your readers, so they can experience the story on a sensory level.

Perhaps the most obvious example of this is dialogue. Dialogue is the purest form of showing. It gives readers a real-time accounting of what the character is hearing, word for word.

You can clearly see the difference in showing and telling in these examples:

The screen door blurred her features. “You’re back so soon?”

“We found the buffalo.” He crossed the yard. “A few miles upriver. Big one. Nearly took Quinn down.”

She pushed through the door onto the porch. “He’s all right? What happened?”

“Nothing much.” He tried to wave it off. “He missed a couple shots.”

She raised her eyebrows. “That’s unusual for him, isn’t it?”

“Everybody has an off day.”

vs.

He told her about the buffalo.

For more on the basics of show, don’t tell, see these posts:

>>Showing and Telling: The Quick and Easy Way to Tell the Difference

>>Are Your Verbs Showing or Telling?

>>Telling Important Scenes, Instead of Showing

3 Tips to Get Even Better at Show, Don’t Tell

Once dramatizing your story’s action has become second nature, you will have mastered the most important aspects of show, don’t tell. Chances are you’re now writing the kind of narrative that would pass a reader’s first-scan test of your book. But, as I said, learning to master show, don’t tell is largely the art of mastering writing itself. Always room for improvement!

Today, I want to talk about three specific ways to look for places in your story where you might be able to change out sneaky telling for more powerful showing.

1. Never Name an Emotion

This “rule” is total hyperbole. Of course it’s fine, in certain contexts , to say, “everyone was happy” or “a flinch of sadness creased his face.”

But I constantly repeat this little phrase—““—as my first line of defense against slipping into what is, perhaps, the easiest of all tells.

Emotion can be a difficult thing to describe, much less evoke. We can show characters falling in love, holding hands, laughing, kissing—but can we be sure readers know they’re happy? Or what if they’re going through all these motions, but it’s just on the surface and, really, they’re extremely unhappy? It’s so much easier to just name the emotion.

And this holds true for more than just emotions. You can also add the following slogans to your repertoire:

Never name a sense (e.g., “she felt cold”; “he saw the truck”; “she smelled the coffee”; “it tasted sweet”; “he heard the explosion”).

or

Never name an action (e.g., “she drove the car”; “he got dressed”).

Obviously, these are extreme guidelines. (In fact, “show, don’t tell” is itself an extreme statement, since there will be moments in every single scene where telling is the best choice. We’d be better off rephrasing the rule to “show before you tell.”)

But because telling is so much easier and, often, so much more natural than showing, it’s good to keep these phrases running through your head. That way, whenever you find yourself typing, “she was happy,” you’ll be more likely to stop and reexamine your choices. When you do, ask yourself the following questions:

1. Is naming the emotion/sense/action really the best choice for this scene?

She was happy.

2. Could you rephrase with a stronger, less obvious verb?

She effervesced.

3. Would you get more mileage out of an action if you dramatized it?

She picked up the train of her gown and twirled around, dancing through the empty garden.

4. Instead of mentioning a sensory experience, could you describe what the character is sensing?

The wet smell of earth, still cool from the night, filled her throat, and she closed her eyes and breathed.

5. Can you imply the character’s emotion through the context—either supportively or ironically?

He smiled at her, and she smiled back.

or

He smiled at her, and she forced herself to smile back.

2. Choose Illustrative Actions

I write novels; I don’t write memoirs (so far, anyway). But I still gleaned a ton from Mary Karr’s dead-on book The Art of Memoir. The whole book is a masterclass in vigorous vulnerability and integrity, but one of the best object lessons I took away was how I, as a novelist, could apply a memoirist’s rigorous approach to show, don’t tell.

I write novels; I don’t write memoirs (so far, anyway). But I still gleaned a ton from Mary Karr’s dead-on book The Art of Memoir. The whole book is a masterclass in vigorous vulnerability and integrity, but one of the best object lessons I took away was how I, as a novelist, could apply a memoirist’s rigorous approach to show, don’t tell.

Here’s a new exercise, inspired by Karr, that I now use all the time:

Imagine for a moment you’re not writing fiction. Instead of being a novelist, you’re now a memoirist, writing about real events from your own life. Pick something in your life that still causes you high emotion.

For the sake of illustration, let’s say you’re going to write about how an older girl at school bullied you mercilessly. You were her victim; she was clearly the antagonist in the scene; and you want your readers to understand this.

But here comes the tricky part. You are not allowed to offer any commentary on your relationship with this bully: how she made you feel back then or how her effect upon you still clangs through your life today. You are not allowed to tell readers she was the inexcusable abuser of an innocent child.

You are only allowed to show readers what happened. Nothing more, nothing less. You can’t tell us she was mean to you, but you can show us when she pulled your hair. You can’t tell us you think she was probably the victim of abuse in her own family, but you can show us that moment when you found her crying in the stairwell. You can’t tell us she scared you out of her mind, but you can show us that day you threw up before going to school.

Even just imagining these scenarios, you can see how much more power there is in the showing than the telling.

Now, apply this to your fiction. This is arguably a little trickier, since now you’re not remembering real details, but creating scenarios that will evoke your characters’ emotions. Doing so will not only enable you to create a stronger scene and a more vivid reading experience, it will also force you to dig deep for story events that properly align with your character’s emotions and motivations at every turn.

Remember: you’re not allowed to tell readers your character is conflicted in her love life. You have to show them why. You’re not allowed to tell readers your character is scared. You have to make them feel the fear too.

In short, you’re not allowed to slant your scenes. You can’t massage the commentary to force readers to see it how you see it. You have to make them see it all for themselves.

3. Don’t Explain the Context

Here’s the awesome thing about good showing: if you’re doing it right, you don’t ever have to hold readers’ hands by telling them.

Still, “reinforcement telling” is an easy crutch to hang onto. I know because I do it all the time.

I’ll do my best to write an evocative scene showing readers all the important actions, senses, and especially emotions. And… then I’ll start doubting myself and throw in a paragraph or two explaining the character’s mental process in the midst of it all.

For example, here’s a recent chunk I’ve cut from my WIP Dreambreaker during my first editing pass:

Nothing here was simple—not her uncle’s involvement, not her relationship with her Gifted, and certainly not her obligations to her crown and her country, which demanded another set of obligations entirely to Rivalé. If she’d been a simpler woman, perhaps she could have thrown all that over. But she wasn’t. That woman had been born and had died all within the few hours that ended the last war. Instead, she chased her demons back inside their dungeon and closed the door.

I really liked this paragraph, describing my female lead’s interiority in a complicated scene. But… I didn’t need it. I chopped it and immediately could feel that the scene breathed better without it. Thanks to recent beta reader (thank you, Kate Flournoy!), I’m finally starting to consistently recognize where I’m doing this in my fiction.

But, you may be thinking, what if I really do need to explain my character’s mental process?

Fair question. In fact, that question is one of the reasons this final pitfall is so easy to fall into and so hard to spot. After all, if you’re writing a deep POV, every single word is more or less in your character’s head. Readers want to be inside his head. They want to know what he’s thinking and feeling. And sometimes they’re even going to want it spelled out for them.

So here are a couple fast questions I’ve developed to help me gut-check when an introspective paragraph is worthy of inclusive—and when it’s just getting in the way by explaining the scene’s otherwise strong context.

Q1: Is this information evident from the context? Would readers understand this emotion or motive without the explanation?

Q2: Could I delete this telling explanation from the narrative and instead create context within the scene that shows it?

Q3: Could I shorten this internal monologue? (Look for spaces in the narrative where you find your natural reading pace taking a “breath.” Upon re-reading, if I find myself a little surprised that the narrative is going on, instead getting back to the action, I know I’ve gone on one sentence too long.)

Now a caveat: it’s perfectly fine to write out all this telling stuff—especially the parts where you’re working through your characters’ emotions—in the first draft. Get it all out there on paper if you need to. But think about it as if you’re explaining it to yourself. Once you’ve got it out of your system, go back and ruthlessly delete useless tellings. Readers don’t need them nearly as much as we do.

***

The better you get at refining show, don’t tell, the better your writing will grow on every single page. Use these tips to gut-check your progress and clear away any useless clutter getting in between your readers and your story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What has been your greatest challenge with show, don’t tell? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/show-dont-tell-tips.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 3 Tips for Improving Show, Don’t Tell appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 17, 2018

What Do You Want Me to Write About?

Hey, everybody!

Hey, everybody!

I’m making myself a bit sparse this week as I’m in the middle of moving. But I want to take the opportunity to flip things on its head this week and ask you to tell me something.

What would you like me to write about?

Is there a writing subject that’s really got your interest right now?

How about a gnawing question you just can’t figure out?

In short, as I start gearing up for a new round of posts and podcast episodes, I’d like to make sure I’m serving your needs as best I can.

Leave me a comment and tell me what post you’d most like me to write for you.

And thanks!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What writing topic or question would you like me to talk about in future posts? Tell me in the comments!

The post What Do You Want Me to Write About? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 10, 2018

3 Tips for Writing a Story That’s Better Than Its Flaws

Steven Schwartz (composer and/or lyricist for musicals as varied as Pocahontas, Wicked, The Prince of Egypt, and Enchanted) has said musicals are about structure first and foremost.

Steven Schwartz (composer and/or lyricist for musicals as varied as Pocahontas, Wicked, The Prince of Egypt, and Enchanted) has said musicals are about structure first and foremost.

If you get the structure right, then a multitude of sins can be forgiven.

This is certainly the case in The Greatest Showman, whose sins are multitudinous. Any selection of critics will tell you all its problems, from ignoring the problematic life Barnum actually lived, to its relatively simplistic structure and lack of historical substance.

But it works. If you’re judging by how leggy it was in theaters (very), how many copies of the album have sold (a million) or been streamed (a billion), something about The Greatest Showman connects with audiences. That something is the way Pasek and Paul’s songs tie theme to structure and pull the audience along for the ride.

3 Tips for Writing a Story That’s Better Than Its Flaws

Six of its eight songs (and three reprises) hit plot points, and hit the timing of those plot points to the minute in five of those six cases. A seventh song is the all-but-required Broadway “I want” song, which works in this case as a delineation of What the Protagonist Wants and What the Protagonist Needs. Theme is present in every song in some way. And, most interestingly, through the work of structure, Barnum is revealed as his own biggest antagonist.

Here are three reasons Greatest Showman still connected with audiences, and how you can go about writing a story that’s better than its flaws.

1. The Songs Hit Plot Points

In this 97-minute movie, more than half of which is music, the plot points come fast, often only minutes apart. To review its structure and songs:

Hook: A young P.T. Barnum dreams of running what will become the circus in the opening number “The Greatest Show.”

Inciting Event/Key Event: Barnum loses his desk job and decides to open a museum of curiosities. This is one of two plot points that isn’t set to music.

First Plot Point: Barnum decides to include living curiosities in his museum. “Come Alive” presents his call to action to the cast of the subplot.

First Pinch Point: While he’s obtained the Thing He Wants, his Ghost keeps him from being satisfied, leading him to court the bourgeoisie through Carlyle in “The Other Side.”

Midpoint: Barnum rejects the Thing He Needs to keep pursuing the Thing He Wants, underscored by Jenny Lind’s song choice, “Never Enough.”

Second Pinch Point: Barnum’s wife sings “Tightrope” while Barnum leaves New York for Lind’s opera tour and Carlyle is left in charge of the circus. His family and his business falter without him.

Third Plot Point: The tour is canceled, and the circus is set aflame. While isn’t set to music, it is bookended by “Tightrope” and Barnum’s “From Now On.”

2. Theme Permeates the Musical Numbers

In “A Million Dreams,” Barnum sings that “dreams for the world we’re gonna make” keep him awake at night. The Thing He Wants is to provide a stable life for his wife and children, one he never had as an impoverished boy. In the same song, his wife provides the counterpoint to the Thing He He Wants: the Thing He Needs. “Share your dreams with me. … Bring me along.” All he needs is his wife and family, but his Ghost leads him to crave more.

That more, though, is “never enough.” At the Midpoint, Barnum has the Thing He Wants and has not yet lost the Thing He Needs. Reaching that goal wasn’t enough. Stealing the stars from the night sky, towers of gold, fame and notoriety, nothing satisfies him. Barnum apparently misses a quiet lyric that Jenny Lind sings: “Darling, without you.” His truth is none of it is enough without the support of family, but Barnum is insatiable.

Finally, just after the Third Plot Point, Barnum’s found family, the cast of the circus, approach him at his lowest point and remind him what he’s done for them. Barnum then sings of all he’s accomplished, but claims they were “someone else’s dreams, pitfalls of the man I became.” He finally relearns that his family, both nuclear and found, is most important, and this truth permeates the remainder of the movie. He has, finally, understood the Thing He Needs.

3. Structure Reveals the True Antagonist

The critic and the mobs, who are set up as the external antagonists in The Greatest Showman, don’t work. They aren’t personal enough, don’t have clear motivations, and are hardly presented as people at all. Since they aren’t given songs of their own, we don’t see their motivations as we do other characters. Perhaps this was a choice necessitated by what they opposed (those who find this theater a spectacle would not join in the singing), but it was one that left me, even on a first viewing, disappointed.

However, structure shows that there are strong Pinch Points. Barnum, through his Ghost, has become the antagonist. His insecurities about his rich in-laws looking down on him lead him to invite Carlyle to join the circus to help him appeal to the upper classes. While “The Other Side” is a fun, almost seducing song, its location at a pinch point shows that this is Barnum unable to accept the Thing He Needs. He’s about to become the antagonist.

Since he has by the First Pinch Point received the basis of the Thing He Wants, and never lost the Thing He Needs, the middle of the story switches its focus slightly from Barnum to the acts he curates. The love story is played out (“Rewrite the Stars”); “curiosities” who were uncomfortable with who they were come out of their shell (“This Is Me”). Within the sub-world Barnum creates, others are free to explore the theme of found family and acceptance.

Here, Barnum is both its creator and its greatest threat. This is most clear in “Tightrope,” which marks the Second Pinch Point. Barnum has decided to take the singer Jenny Lind on a national tour that will cost him a fortune before it turns a profit, leaving Carlyle in charge of the circus, and his wife and daughters alone. No one wants him to go. The contrast between the circus failing without him and Barnum’s courting the social elite plays over the soundtrack of his wife reminding him that he has given up What He Needs.

***

Despite its flaws, The Greatest Showman provides an excellent example of how musicals use songs to hold together the structure, how to follow a Cinderella arc, and how a well-structured story can provide clues about what’s going on beneath its surface.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do think is the single most important element in a story that works despite its flaws? Tell me in the comments!

The post 3 Tips for Writing a Story That’s Better Than Its Flaws appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 3, 2018

Do You Have Sloppy Writing Habits? (And 4 Things to Do About It)

The question I want to ask today is whether sloppy writing habits are a deterrent to success, a natural and unavoidable part of the creative process, both, or neither.

The question I want to ask today is whether sloppy writing habits are a deterrent to success, a natural and unavoidable part of the creative process, both, or neither.

I’ve never met the writer (myself included) who didn’t suffer from sloppy writing habits. These habits fall into a number of categories—everything from sloppy handwriting to sloppy writing processes to sloppy writing techniques.

“Sloppy” is an inherently negative word that reeks of frustrated parents cajoling unwashed teenagers to impose order on their personal batcaves. And yet—sloppiness also seems kind of inherent to all things creative. Indeed, some researchers have gone so far as to famously insist “a messy desk is a sign of genius.”

Naturally, as a neat freak, I take exception to this. I like order and schedules. I hate chaos and spontaneity.

I’ve been that way since childhood. My sister, with whom I shared a bedroom (aka battle zone) for most of our childhood, recently dug up a “Sisters’ Constitution” I created for her to sign when I was around twelve and she was around eight. This highly legal and formal document gravely promised we would both “close my drawers, put my stuff away, respect my sister’s stuff, keep my stuff on my side of the room.” (She pointed out recently that it seemed a little unfair I hadn’t balanced it with clauses promising to “be nice to my little sister, leave the door open at night when my sister is scared, and let my sister play with me.”)

As a writer, my entire journey toward improving myself and my stories has been largely geared around ideas of organization. Over the years, I have created a streamlined writing process that allows me to be as effective as I can be at any given moment. Naturally, much of what I teach on this blog reflects that. I’m a proponent of outlining, story structure, schedules, logic, and linearity.

But during one of my morning walks recently, I started pondering a comment a fellow writer had made to me that expressed his acceptance of his own sloppy writing habits. He said something along the lines of “that’s just how it is.”

That got me thinking about my preconceptions about the place of sloppiness in the life of a writer, its almost stereotypical omnipresence in the lives of writers in general, and both its relationship to and influence upon art itself.

Why Writers Can Get Away With Sloppy Writing Habits

So. Sloppy writing habits. Is that really “just how it is”?

I think, upon reflection, the obvious answer is: “Yeah, totally.”

Almost any perusal of any writer anywhere—his or her lifestyle, writing habits, creative process, even writing techniques themselves—show us that writers are, in general, almost unavoidably sloppy.

We could argue that creativity is itself a sloppy and ungovernable process. Although I ultimately disagree with this, it is true up to a certain extent. There’s a reason Legos come out of the box as a bazillion seemingly chaotic pieces and only slowly end up as the recognizable Death Star. Even more than Legos, writing is a tremendously complex and complicated art form that requires the confluence of dozens of unique skill sets.

More than that, any organization within the writing life itself—the mindset of being a writer, the overarching process of creating a novel, or the daily routine of putting words on paper—requires an organization of ourselves on a personal level much deeper than anything to do with the writing itself. And that, of course, is the vocation of a lifetime.

In short, sloppiness of one degree or another (and usually a lot of others) is inevitable.

More than that, I’m going to posit the art of storytelling on paper is possibly more forgiving of sloppiness than just about any other creative discipline.

Think about it.

Something I say over and over is, “There’s no such thing as a perfect story.” That’s not actually true, since perfection always exists, as least theoretically. When I say that, what I actually mean when I say that “nobody ever has or ever will write a perfect story.” Phew. Pressure’s off.

However, what that means by extension is that every story you’ve ever loved, you’ve loved in spite of some inevitable sloppiness on the author’s part. Maybe the plot structure was a little off; maybe it was even a lot off. Maybe the characters didn’t ring quite true. Maybe there were plot holes requiring massive suspension of disbelief on your part. Maybe it was dumb as all get out and you’re actually embarrassed to admit you liked it—but you did because it connected with you on an emotional level and made you feel something you cherish.

On the other end of the spectrum, even if the story’s end product is relatively flawless, chances are the author’s process of getting to that end product wasn’t so flawless. He spent nights pacing the floor, pulling his hair out with frustration and self-doubt. She rewrote the entire thing twelve times. He wrote only sporadically—six hours one day, not a thing for months, only fifteen minutes another day. She neglected to research important details until deep into the revision phase—and had to ditch a whole subplot when it proved unrealistic.

But readers don’t really care. The writer finally got to an end product that was good enough despite its inevitable flaws. It’s not like a dance where one wrong move throws off the entire routine. Or a painting where a smush of paint in the wrong place ruins the whole thing. As long as a story is “good enough,” readers are primed to forgive a story (and, by extension, its writer) for not being perfect.

So, yay! Long live sloppiness! Right?

4 Do’s and Don’ts of Sloppy Writing Habits

Can you be a sloppy writer—and still be a good writer? A successful writer?

Unconditionally, yes.

But does that mean you should be a sloppy writer?

There’s a balance here, as with almost all aspects of the creative life, but I still believe the optimum leans more heavily away from sloppy writing habits and toward methods and mindsets that promote effectiveness, efficiency, clarity, and even simplicity.

We seek the balance between creativity and logic, spontaneity and discipline, instinct and knowledge because we wish to optimize all aspects of the craft (and life itself, which is ever a balance between subconscious and conscious). I have no desire to discipline all the creativity out of my art. But I also have no desire to let the unpredictable wildness, and, yes, sloppiness, of raw creativity govern my life and my career.

This is a personal balance. We’re all different people. I crave order; others feel stifled by it. Naturally, my personal approach to writing, on every level, has focused on optimizing my strengths and minimizing my weaknesses. This is what we all must do in figuring out which sloppy writing habits unleash our creativity and which inhibit us by unnecessarily complicating the process.

To that end, hear are several do’s and don’ts to consider in refining your own balance.

1. Don’t Make Excuses for Your Sloppy Writing Habits

The first step is calling a spade a spade. Saying “oh I’m just a pantser” or “oh I’m just a plotter” like they’re psychological conditions is not specific or helpful. Dig a little deeper and identify the habits you’re clinging to that are perhaps causing excesses on one side or the other of the writing balance.

Correcting sloppy habits—of any stripe—is difficult. Sometimes it’s easier to keep doing what we’re doing rather than trying to figure out what the problem is and how to fix it. But muddy thinking is never helpful to a writer, of all people.

If your desk is a mess, own it (after all, maybe it means you’re a genius). Don’t make excuses. Dig down and figure out why you have a hard time keeping it clean. Maybe it’s a good reason; maybe it’s not. But it’s important to know which it is, in order to optimize your response.

2. Do Identify the Parts of Writing That Are Most Difficult for You—And Do Something About It

Most sloppy writing habits—even ones we aren’t consciously aware of as sloppy—are the result of aspects of the writing life that are difficult for us.

One sloppy habit I’m currently working on conquering is my inherent laziness with certain aspects of causality within my plots. Oh, that character motivation doesn’t totally make sense? Or that battle choreography isn’t realistic? Or that plot hole got deeper because the fantasy physics didn’t quite work? Oh, well.

As a writer, I get almost claustrophobically bored with this stuff. I just want to race on to the good bits—character relationships, epic imagery, thematic grist. But, of course, as a reader, I’m much less likely to appreciate these ragged loose ends in someone else’s story. I recognize that, and I’m gritting my teeth and working to improve these difficult parts of my writing.

For you, the difficult bits might be understanding story structure, creating coherent POVs, maintaining a consistent writing schedule, avoiding procrastination temptations, or organizing research notes.

Whatever the case, dig around to identify what aspects of your writing you’ve currently got chained down in your mental dungeons where you don’t have to look them in the eye. Maybe it’s time to let them into the sunlight and start doing some rehabilitation.

3. Do View Writing as a Discipline—With Its Own Guidelines

Here’s a truth: A writer can remain in total ignorance of all higher concepts of theory and technique. This writer can ignore every good writing habit every known, throw onto the page a story that is strictly speaking a sloppy mess, and still connect with writers. (I’m sure you can think of a few popular authors today who might very well fit this description.)

You don’t have to view writing as a discipline in order to be a writer, or even to be a good(-ish) writer. But if you want to write to your potential—if you want to conquer your demons—if you want to get consistently and predictably better as both the art of writing and the process of writing—then viewing and treating writing as a discipline is your surest bet.

As a discipline, writing provides certain evident principles for slowly straightening up your mental desk and finding your best balance between the sloppiness of creativity and the structure of discipline. Somewhere in there, I guarantee there’s a sweet spot where everything sings together.

4. Don’t Ban Sloppiness Entirely

If we equate sloppiness, to a certain degree, with creativity, then we surely don’t want to entirely ban sloppiness from our lives. However much we may be able to learn to a harness a predictable flow of creativity, creativity itself will never be linear, logical, or even neat.

Diminishing the negative effects of sloppy writing habits is about clearing away unnecessary clutter so we can tap in as directly and powerfully as possible to the raw creativity itself. But we never want to block or even structure that initial creativity.

Most people view the concept of outlining as one of the most structured of writing techniques. So it may seem ironic to suggest that a free-form outlining style (aka stream-of-conscious brainstorming) is actually incredibly adept at channeling raw creativity. It does this by separating and protecting baby creativity from the most technical and precise of all writing techniques—the creation of the word-by-word narrative of the story itself. This is why I do all my story creation in an in-depth outlining phase, which then leaves the structured and disciplined aspects to stand on their own feet during the first draft.

Whatever your arrangement of the foundational aspects of creating, organizing, and getting your story down on paper, always check your balance. Discipline should optimize creativity. It should never inhibit it.

***

As always, conquering sloppy writing habits is really just the discipline of knowing ourselves—recognizing what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, how we work best, and how to create life choices that find and optimize our best balance.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What are some sloppy writing habits you’re currently struggling with? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/sloppy-writing-habits.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Do You Have Sloppy Writing Habits? (And 4 Things to Do About It) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 27, 2018

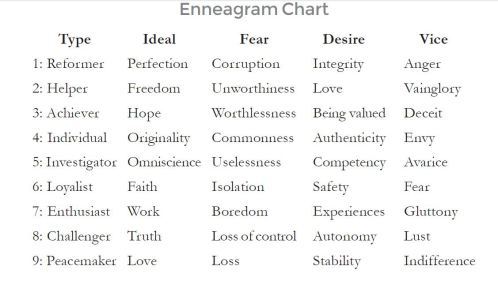

5 Ways to Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters

The Enneagram. Maybe you’ve heard of it. Maybe you’ve even used the Enneagram to write better characters.

The Enneagram. Maybe you’ve heard of it. Maybe you’ve even used the Enneagram to write better characters.

Like Myers-Briggs, Socionics, and the Four Temperaments, the Enneagram is one of many systems within the study of personality theory. These systems are designed to identify the patterns found in the different ways we approach various aspects of life, so we might better study and understand ourselves and others.

In short, the Enneagram is not only a useful life tool, it’s also the perfect character-creation tool.

I’ve always been interested in personality theory. Let’s face it, I just like theories (come to me, story theory, my love). But I don’t see it as any kind of coincidence that my interest in characters and stories dovetailed so conveniently with the ever-deepening rabbit hole of personality theory.

I’m not alone. In fact, my introduction to the Enneagram, many years ago, was on romance author Laurie Campbell’s site, where she offered a brief description of the system’s nine types as, you guessed it, a character tool. Since then, I’ve pursued Myers-Briggs—another personality-typing system—in some depth, but only this year have I finally dived headlong into the Enneagram.

I’m not exaggerating when I say it has changed my life—and my writing.

What Is the Enneagram?

Unlike Myers-Briggs, which is a “neutral” system focused primarily on the differing ways people take in and use information, the Enneagram is often called an “ego-transcendence tool.” Sounds all lofty and new-agey, but it’s really just code for “this-is-gonna-hit-you-where-it-hurts.”

(Side Note: I read once, in relation to Myers-Briggs, that if you typed yourself and had nothing but excitement about your discoveries, you very likely mistyped. A true typing is going to show you stuff about yourself that maybe you’d rather not look at. In short, you can be pretty sure you’ve found your type when you end up muttering, “Ah, dang.” If that’s true of Myers-Briggs, it’s about ten times truer of the Enneagram. But I digress.)

In their book The Road Back to You (which is a great overview of the Enneagram, uncomplicated by denser aspects of the theory), Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile introduce the Enneagram like this:

In their book The Road Back to You (which is a great overview of the Enneagram, uncomplicated by denser aspects of the theory), Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile introduce the Enneagram like this:

The Enneagram teaches that there are nine different personality styles in the world, one of which we naturally gravitate toward and adopt in childhood to cope and feel safe. Each type or number has a distinct way of seeing the world and an underlying motivation that powerfully influences how that type thinks, feels, and behaves….

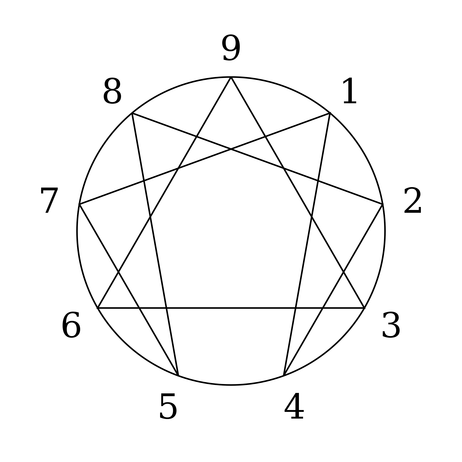

The Enneagram takes its name from the Greek words for nine (ennea) and for a drawing or figure (gram). It is a nine-pointed geometric figure that illustrates nine different but interconnected personality types. Each numbered point on the circumference is connected to two others by arrows across the circle, indicating their dynamic interaction with each other.

The Enneagram is a vast and deep system, impossible to completely summarize in a post like this, so I won’t even try. However, perhaps the simplest way to sum it up is to say that the Enneagram is designed to call baloney on the defensive lies we have been programmed from childhood to tell ourselves about ourselves and the world.

How I Discovered the Enneagram

My experience with the Enneagram went something like this.

I’d decided long ago, after reading the brief descriptions on Laurie Campbell’s site, that I was a Five: The Investigator. Introverted, studious, quirky. Yeah, totally. Fives are awesome!

Confidently, I started reading Cron and Stabile’s book—until I hit the chapter about the Three: The Achiever. It was like the authors reached out, grabbed their own book, and smacked me between the eyes with it. It was a total oh-dang moment.

Don’t get me wrong. Threes are awesome too. Productive, adept, ambitious. But I immediately knew, without question, I was a Three simply because so much of what I read hurt.

I would have been totally cool (too cool) with the Five’s problems of hyper-independence, trust issues, and sarcasm (because, hello, that’s all my favorite characters ever). I’ve always considered myself a relatively self-aware, self-honest person, but reading about the Three’s motivations made me face things about myself I’d never been willing to admit or face, things I really didn’t like about myself, such as the driving need for the approval of others and a pervasive underlying belief in, essentially, “salvation (and love) by works.”

For me, the revelations that followed were toppling dominoes that unlocked answers to questions I’d been asking about myself and my life for a long time. It was painfully liberating. My awareness of my Three-ness has since allowed me to acknowledge and own aspects of myself I’ve long hidden from, which, of course, now means I have to deal with them. It has been and continues to be incredibly exciting.

And now I get to use these new approaches to life, people, and the self to help me (I hope) write better characters.

Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters

There is just so much to say about how you can use the Enneagram to write better characters. I’m not even going to get into the wings, triads, integration/disintegration, instinctual variants, or tritypes (the latter of which I have yet to study in any depth but which, I think, bears out I wasn’t totally wrong in my initial association with the Five).

It was in reading Don Richard Riso’s Enneagram “bible” Personality Types that I was truly blown away by both the beautiful complexity of the system and its easy applicability to writing characters. After listening to the book on audio, I immediately bought my own copy and added it to my pile of easy-reach writing-resource books. I will be referring to it regularly when I start outlining my next book.

It was in reading Don Richard Riso’s Enneagram “bible” Personality Types that I was truly blown away by both the beautiful complexity of the system and its easy applicability to writing characters. After listening to the book on audio, I immediately bought my own copy and added it to my pile of easy-reach writing-resource books. I will be referring to it regularly when I start outlining my next book.

Following are the five primary ways I plan to use the Enneagram to write better characters in the future.

1. Typing Characters, the Fast and Easy Way

Let me start with a slight digression: I’ve been studying Myers-Briggs for years. I love it. In its own way, it too completely changed my life and my writing. But I actually find the system really difficult to use in typing my characters. For whatever reason, I can type other people’s characters with reasonable confidence, but I can’t type my own to save my life. For example, I have progressively typed Chris Redston, the protagonist of Dreamlander as: ISFJ, ESFJ, INFJ, ISFP (with ponderings about ISTJ and INTJ thrown in for good measure).

Let me start with a slight digression: I’ve been studying Myers-Briggs for years. I love it. In its own way, it too completely changed my life and my writing. But I actually find the system really difficult to use in typing my characters. For whatever reason, I can type other people’s characters with reasonable confidence, but I can’t type my own to save my life. For example, I have progressively typed Chris Redston, the protagonist of Dreamlander as: ISFJ, ESFJ, INFJ, ISFP (with ponderings about ISTJ and INTJ thrown in for good measure).

(Second Side Note: I actually have serious doubts that any author is able to truly write a character with differing cognitive functions from their own. For example, as an INTJ, I might be able to fake an ESFJ character based on ESFJs I personally know, but because I share no functions with that type, can I really write about the mental process of a character who absorbs information via Introverted Sensing and makes judgments via Extroverted Feeling? Maybe, but I kinda doubt it.)

In contrast to Myers-Briggs, the deceptive simplicity of the Enneagram makes it much easier to confidently recognize a character’s likely type/number and use it as a guideline while writing. Maybe it’s just me, but I find it far less complicated to look at a character and recognize, “she’s a One,” rather than running through a litany of criteria to determine her four cognitive functions and their order in her Myers-Briggs stack.

When I do figure out a character’s Enneagram, I instantly see them a little clearer, and I instinctively know just a little bit more about them. (Chris, by the way, is a Six. In case you were wondering.)

(Third Side Note: Although there is some overlap, the Enneagram is an entirely different system from Myers-Briggs, with an entirely different focus. Typing a character according to the Enneagram doesn’t accomplish the same things as will typing that character according to Myers-Briggs. So if you feel qualified—or, like me, literally unable to resist, do both!)

2. Keeping Characters Consistent: Strengths and Weaknesses

One of the Enneagram’s primary focuses is each type’s inherent strengths and weaknesses. This is convenient, since one of a writer’s primary focuses is each character‘s inherent strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, we could argue that the pairing of strength/weakness is one of the most important aspects of character, and thus story, since it drives everything that happens in the plot and theme.

In expanding on the chart at the beginning of the post, a super-simplistic approach to each type’s strength/weakness might look like this:

One, The Reformer: Responsible and idealistic/judgmental and hyper-perfectionistic

Two, The Helper: Kind and generous/intrusive and needy

Three, The Achiever: Productive and adaptable/overly image-conscious and out of touch with emotions

Four, The Individual: Creative and idealistic/self-absorbed and unrealistic

Five, The Investigator: Perceptive and self-reliant/emotionally-detached and cynical

Six, The Loyalist: Loyal and engaging/reactive and fearful

Seven, the Enthusiast: Optimistic and fun/impulsive and undisciplined

Eight, the Challenger: Bold and decisive/domineering and combative

Nine, the Peacemaker: Calm and reliable/passive-aggressive and unmotivated

Once you really start studying the system, you realize there’s so much more to it than just this. But even just these simple starting points give you an intuitive strength/weakness pairing for your character that sets everything up right for a solid character arc.

3. Identifying the Character’s Motivation, Want, Need, and Backstory “Ghost”

Because of the Enneagram’s talent for pointing a finger at painful motivations arising from our pasts (especially our childhoods), it’s perfect for figuring out the backstory Ghost motivating your character’s goals in your main story.

The Ghost (sometimes called the Wound) is a hole in your character’s self. It’s the hole where the Lie the Character Believes first started growing, and it’s the hole she must climb out of if she’s to grow into wholeness by the end of her arc.

Again, not so coincidentally, the Enneagram offers a basic Lie for each type:

One: Mistakes are unacceptable.

Two: I am not lovable.

Three: I am what I do.

Four: No one understands me/there is something wrong with me.

Five: I am not competent to handle the demands of life.

Six: The world is not safe.

Seven: I can’t count on people to be there for me.

Eight: Only the strong survive.

Nine: I don’t matter much.

Starting with some iteration of the above for your character, you can start extrapolating consistent motivations and goals within the specific needs of your plot.

4. Charting Character Arcs

Not only is the Enneagram system helpful in setting up character arcs, it’s also helpful in double-checking that the progression of your character’s arc is consistent and realistic.

One of the main reasons I ended up buying a hardcopy of Riso’s Personality Types was that the book methodically charts nine levels of “health” for each type. It divides these nine levels into three apiece under the headings of Healthy, Average, and Unhealthy. Once you know your character’s specific story Lie and the type of arc you want him to follow, you can reference Riso’s lists to nail down how a healthy, average, or unhealthy person of this type would behave.

For example, if you’re writing a Positive Change Arc for a generally likable character, you’re probably going to to start him out in one of the Average categories and let the story’s events help him progress to Healthy. Or maybe you’re writing a Negative Change Arc, about a descent into unwellness or psychosis, which brings me to…

5. Writing Better Bad Guys

For me, bad guys have always been one of my challenges. A large part of this was a struggle to find suitable motivations for their evil deeds. “Oh, they’re just crazy” is an easy out that doesn’t give due diligence to what should be one of the strongest characters in the story.

Yet another reason I was psyched by Riso’s “health charts” was that they immediately grounded my understanding of what would motivate a deeply unhealthy person to commit deeply unhealthy acts. At the bottom level of psychosis for each type (which is almost never reached without either deep-seated childhood trauma or a physiological catalyst), Riso suggests the “ultimate end” each type is most likely to fall to:

One: Punitive Sadism

Two: Hypochondria and Martyr Complex

Three: Murder (!)

Four: Suicide

Five: Schizophrenia

Six: Masochism

Seven: Addiction and Manic-Compulsive Behavior

Eight: Megalomania

Nine: Dissociative disorders

Personally, I take these with a massive grain of salt (because how likely is it that all, or even the majority of schizophrenia sufferers, are Fives?). But it is a useful guide for following the descent of personal and mental un-health to a consistent ending point. If you read all the sections in Riso’s book, it becomes easy to provide a proper motive to a character who is undergoing a realistic personal descent.

***

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the Enneagram. I’ve been studying it for months now and have barely scratched its surface. If you’re interested in digging deeper, both for yourself and your characters, I recommend starting with the book The Road Back to You by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile and following it up with the significantly heavier and more in-depth Personality Types by Don Richard Riso with Russ Hudson.

Brace yourselves, half fun, and get ready to say: Oh, dang. :p

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever used the Enneagram to write better characters? Tell me about it in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/5-ways-to-use-the-enneagram-to-write-better-characters.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 5 Ways to Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 20, 2018

Writer’s Envy—And 3 Thoughts on What to Do About It

Last year, one of your writing buddies landed your dream agent. This year, they published with a great publisher. Now, they just sent you a #happydance email, telling you they’ve been nommed for your genre’s biggest award. You’re happy for your friend. Really, you are. But try as you might, your gut just closed up with a sick but all-too-familiar feeling: writer’s envy.

Last year, one of your writing buddies landed your dream agent. This year, they published with a great publisher. Now, they just sent you a #happydance email, telling you they’ve been nommed for your genre’s biggest award. You’re happy for your friend. Really, you are. But try as you might, your gut just closed up with a sick but all-too-familiar feeling: writer’s envy.

The writing community is a great place, full of sensitive, supportive people all trying to prioritize the honesty of their art and the worthiness of chasing their dreams. But the writing community also has its dark sides, and none is perhaps more pervasive or insidious than a writer’s envy. I daresay only the most centered among us have evaded it entirely.

But why? Other than the fact we’re all humans and envy is perhaps one of the easiest of all human failings, why do writers seem particularly susceptible to the poison of envy?

And just to mix things up, here’s another question: Is envy really a poison?

What’s the best way to view and deal with writer’s envy?

Let’s take a look.

Writer’s Envy: Why Are We So Competitive?

Art is a cooperative.

Stories, perhaps more than any other art form, are shared experiences. In striving to hit that perfect note of verisimilitude with our writing, we are trying to share in the larger human experience, just as we are also trying to share our own personal experiences. We are tapping into a collective subconscious that resonates to the same symbolic triggers and archetypal constructs.

Most of us want, on some level, for our stories to positively impact others. We are trying to share something good with the world. Something true. Something of worth.

We are also taking what others have shared with us—both in life itself and in their art—and refashioning it, so we might reshare it yet again. Art is the ultimate recycling system: nothing is ever wasted; everything is reused.

I believe it is an absolute truth that when one artist succeeds, the rewards belong to all of us. When a good story (or song or picture) is given to the world, and then given a platform from which it can be shared with the greatest number of people, that is one of the most perfect things in life.

In short, on a purely artistic level, there is no competition. There is only cooperation. Your art makes my art better. My art makes your art better. And we all benefit.

Buuuuuuutt…..

Pure artistry, like any form of absolutism, doesn’t actually operate down here in the grungy real world.

Down here, it’s Rottweiler-eats-Chihuahua.

Down here, it’s all my-ego-is-a-ravenous-insecure-whining-powerful-beast-who-wants-everyone-else-in-a-bleeding-pile-under-my-jackboots.

4 Reasons for Writer’s Envy

So why? Why are artists—who are supposed to be all wise and ethereal and above the common longings for worldly acclaim—so susceptible to dark and seemingly useless feelings of envy?

1. We’re Not Wise, Ethereal, or Above It All

We’re just blokes and blokesses who, perhaps even more than others, are struggling really, really hard to make sense of our own hyper-abundant human frailties.

2. We’re Vulnerable

There are technical aspects of excellence involved in every art form. Just like a master carpenter, we take pride in our ability to craft solid structures and beautiful prose. And just like that carpenter, we’re going to be bummed when our skills don’t measure up to where we want them to be.

But, even more than our skills, we’re putting ourselves on display. When that is found wanting, in any measure, it hurts ridiculously. Someone criticizing our work might feel their comments are on par with saying, “I don’t like your shirt,” when what we feel they’re really telling us is, “I don’t like your face.”

3. We Have a Hard Time Succeeding

Book publishing isn’t obviously competitive in the sense that my achieving my dreams will rule out your achieving your dreams, and vice versa. Even still, it certainly seems like there are limited opportunities for success. It’s hard to make it as a writer. Very few of us make any money off writing, fewer still make a living off it, and very few indeed become famous millionaires. When someone reaches one of those coveted milestones, it’s easy to knee-jerk into feeling our own chances just got slimmer.

4. We Tend to View Other People’s Successes as a Yardstick of Our Own Failure

When another writer succeeds—especially someone you know personally—it’s hard not to feel as if their good fortune isn’t a giant spotlight revealing everything you, by contrast, have not achieved. They’re agented, published, bestselling, and award-winning. You… are not. Pretty stark.

Reframing Writer’s Envy: It Doesn’t Have to Be a Bad Thing

Is it possible for something objectively bad to be subjectively good?

With a little reframing, it just might be.

Envy is bad. I daresay none of us enjoys it. It sits in our guts like bad sushi. It’s sickening—literally. It makes us unhappy for others and unhappy for ourselves. And then, often, we feel bad for feeling jealous in the first place. It seems pretty irredeemable.

But envy itself is neither bad nor good. It just is. It’s a symptom—like a headache—telling us of a deeper issue.

It’s what we do with that feeling that creates either a bad experience or a good one.

Envy is telling you, first and foremost, that you want something. It might be something obvious, like: I want my book published or I want to win that award too. But even these statements are pointing to something deeper, whether it’s an unresolved insecurity or simply a dream you’ve yet to fulfill.

A writer’s envy is a flashing neon sign, reminding you about unfinished business. So often in life, we sit and we wish for a sign in answer to the old prayer: Just show me what to do! Envy is about as obvious a sign as you can ask for.

So do something about it.

But do something good.

Sage Cohen, in Fierce on the Page, said:

Sage Cohen, in Fierce on the Page, said:

When envy comes up in your writing life, I propose that you don’t subdue it in the name of propriety and good citizenry. I hope you do the opposite: investigate it until you get top that place in you that says, I want, I need, I DESIRE.

Envy only becomes bad when it prompts thoughts about others. Secret wishes for another’s downfall or even just, passive-aggressively, that they might not be quite so successful until you’ve caught them up, are negative in the extreme. Worse, they’re counter-productive. Fuming—even suppressed fuming—about frustrations with another’s success just gets in the way of your ability to act productively on your own behalf.

Instead, when envy strikes, focus on yourself:

1. Identify Your True Emotional Triggers

Why are you jealous? Because it’s your dream to land that specific agent? Because right now you’re doubting your ability to even write a good sentence, much less the dreamed-of book? Because you think the other writer’s success was undeserved for a specific, quantifiable reason (i.e., “I could write a better book than that!”)?

It’s easy to gripe about other people—whether accurately or not. What’s not so easy is facing down our own motives. Looking our insecurities in the eye can be terrifying. Admitting our work isn’t yet good enough to help us fulfill our dreams is, at best, frustrating. And feeling like you’re doing everything you know how to do—and still not getting what you want—is heartbreaking.

But the only way to address a problem is to first honestly acknowledge what’s really going on.

2. Step Away From the Ego

So many of our jealousies are just plain silly. As already mentioned, art is far more cooperative than competitive. Resentment of another writer’s success is often (always?) counter-intuitive. (If you write an amazing story and I read it, I am going to be that much more likely to write a better story myself thanks to the gifts your story has given me. And then, of course, there’s the fact that if a reader reads and loves your amazing story, they’re going to be that much more pumped to read another amazing story—and maybe they’ll read mine!)

But the ego isn’t always sensible. Certainly, it isn’t easy to overcome. Just realizing and admitting a) the undeniable reality of the ego’s demands and b) it’s often childlike short-sightedness is a huge step toward redirecting its power.

Looking at the bigger picture (of life, art’s role in life, and our role in art) is a helpful re-centering trick. Humility is inevitable when we are honest about how infinitesimal each of us is within that larger picture (and yet, how each of us, supplies an inevitable butterfly effect). It then becomes easier to recognize and embrace the contributions of our fellows, rather than feeling threatened by them.

3. Act on What You’ve Learned About Yourself

Once you’ve dug down deep inside yourself to discover what’s at the root of your writer’s envy, you will have gained information you can act on. You’ve faced down your insecurities. Maybe what you’ve found is something as surface level as My characters aren’t as good as my writing buddy’s characters! or something as deep as I will never feel worthwhile unless I can write an acclaimed book!

More than that, you’ve discovered uncluttered truths about what it is you want: to be published, to be a bestseller, to win an award, to impact readers of a certain group, to write for the pure joy of it.

Your envy has given you an indication of your progress. It tells you you’re not yet where you want to be. It’s a road sign, saying “120 miles to Graceland.” You’re not there yet. But you are on the right road. Congratulate yourself—and keep driving.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you ever struggle with writer’s envy? What do you do about it? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/writers-jealousy.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Writer’s Envy—And 3 Thoughts on What to Do About It appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

Writer’s Jealousy—And 3 Thoughts on What to Do About It

Last year, one of your writing buddies landed your dream agent. This year, they published with a great publisher. Now, they just sent you a #happydance email, telling you they’ve been nommed for your genre’s biggest award. You’re happy for your friend. Really, you are. But try as you might, your gut just closed up with a sick but all-too-familiar feeling: writer’s jealousy.

Last year, one of your writing buddies landed your dream agent. This year, they published with a great publisher. Now, they just sent you a #happydance email, telling you they’ve been nommed for your genre’s biggest award. You’re happy for your friend. Really, you are. But try as you might, your gut just closed up with a sick but all-too-familiar feeling: writer’s jealousy.

The writing community is a great place, full of sensitive, supportive people all trying to prioritize the honesty of their art and the worthiness of chasing their dreams. But the writing community also has its dark sides, and none is perhaps more pervasive or insidious than a writer’s jealousy. I daresay only the most centered among us have evaded it entirely.

But why? Other than the fact we’re all humans and jealousy is perhaps one of the easiest of all human failings, why do writers seem particularly susceptible to the poison of envy?

And just to mix things up, here’s another question: Is jealousy really a poison?

What’s the best way to view and deal with writer’s jealousy?

Let’s take a look.

Writer’s Jealousy: Why Are We So Competitive?

Art is a cooperative.

Stories, perhaps more than any other art form, are shared experiences. In striving to hit that perfect note of verisimilitude with our writing, we are trying to share in the larger human experience, just as we are also trying to share our own personal experiences. We are tapping into a collective subconscious that resonates to the same symbolic triggers and archetypal constructs.

Most of us want, on some level, for our stories to positively impact others. We are trying to share something good with the world. Something true. Something of worth.

We are also taking what others have shared with us—both in life itself and in their art—and refashioning it, so we might reshare it yet again. Art is the ultimate recycling system: nothing is ever wasted; everything is reused.

I believe it is an absolute truth that when one artist succeeds, the rewards belong to all of us. When a good story (or song or picture) is given to the world, and then given a platform from which it can be shared with the greatest number of people, that is one of the most perfect things in life.

In short, on a purely artistic level, there is no competition. There is only cooperation. Your art makes my art better. My art makes your art better. And we all benefit.

Buuuuuuutt…..

Pure artistry, like any form of absolutism, doesn’t actually operate down here in the grungy real world.

Down here, it’s Rottweiler-eats-Chihuahua.

Down here, it’s all my-ego-is-a-ravenous-insecure-whining-powerful-beast-who-wants-everyone-else-in-a-bleeding-pile-under-my-jackboots.

4 Reasons for Writer’s Jealousy

So why? Why are artists—who are supposed to be all wise and ethereal and above the common longings for worldly acclaim—so susceptible to dark and seemingly useless feelings of jealousy?

1. We’re Not Wise, Ethereal, or Above It All

We’re just blokes and blokesses who, perhaps even more than others, are struggling really, really hard to make sense of our own hyper-abundant human frailties.

2. We’re Vulnerable

There are technical aspects of excellence involved in every art form. Just like a master carpenter, we take pride in our ability to craft solid structures and beautiful prose. And just like that carpenter, we’re going to be bummed when our skills don’t measure up to where we want them to be.

But, even more than our skills, we’re putting ourselves on display. When that is found wanting, in any measure, it hurts ridiculously. Someone criticizing our work might feel their comments are on par with saying, “I don’t like your shirt,” when what we feel they’re really telling us is, “I don’t like your face.”

3. We Have a Hard Time Succeeding

Book publishing isn’t obviously competitive in the sense that my achieving my dreams will rule out your achieving your dreams, and vice versa. Even still, it certainly seems like there are limited opportunities for success. It’s hard to make it as a writer. Very few of us make any money off writing, fewer still make a living off it, and very few indeed become famous millionaires. When someone reaches one of those coveted milestones, it’s easy to knee-jerk into feeling our own chances just got slimmer.

4. We Tend to View Other People’s Successes as a Yardstick of Our Own Failure

When another writer succeeds—especially someone you know personally—it’s hard not to feel as if their good fortune isn’t a giant spotlight revealing everything you, by contrast, have not achieved. They’re agented, published, bestselling, and award-winning. You… are not. Pretty stark.

Reframing Writer’s Jealousy: It Doesn’t Have to Be a Bad Thing

Is it possible for something objectively bad to be subjectively good?

With a little reframing, it just might be.

Jealousy is bad. I daresay none of us enjoys it. It sits in our guts like bad sushi. It’s sickening—literally. It makes us unhappy for others and unhappy for ourselves. And then, often, we feel bad for feeling jealous in the first place. It seems pretty irredeemable.

But jealousy itself is neither bad nor good. It just is. It’s a symptom—like a headache—telling us of a deeper issue.

It’s what we do with that feeling that creates either a bad experience or a good one.

Jealousy is telling you, first and foremost, that you want something. It might be something obvious, like: I want my book published or I want to win that award too. But even these statements are pointing to something deeper, whether it’s an unresolved insecurity or simply a dream you’ve yet to fulfill.

A writer’s jealousy is a flashing neon sign, reminding you about unfinished business. So often in life, we sit and we wish for a sign in answer to the old prayer: Just show me what to do! Jealousy is about as obvious a sign as you can ask for.

So do something about it.

But do something good.

Sage Cohen, in Fierce on the Page, said:

Sage Cohen, in Fierce on the Page, said:

When envy comes up in your writing life, I propose that you don’t subdue it in the name of propriety and good citizenry. I hope you do the opposite: investigate it until you get top that place in you that says, I want, I need, I DESIRE.

Jealousy only becomes bad when it prompts thoughts about others. Secret wishes for another’s downfall or even just, passive-aggressively, that they might not be quite so successful until you’ve caught them up, are negative in the extreme. Worse, they’re counter-productive. Fuming—even suppressed fuming—about frustrations with another’s success just gets in the way of your ability to act productively on your own behalf.

Instead, when jealousy strikes, focus on yourself:

1. Identify Your True Emotional Triggers

Why are you jealous? Because it’s your dream to land that specific agent? Because right now you’re doubting your ability to even write a good sentence, much less the dreamed-of book? Because you think the other writer’s success was undeserved for a specific, quantifiable reason (i.e., “I could write a better book than that!”)?

It’s easy to gripe about other people—whether accurately or not. What’s not so easy is facing down our own motives. Looking our insecurities in the eye can be terrifying. Admitting our work isn’t yet good enough to help us fulfill our dreams is, at best, frustrating. And feeling like you’re doing everything you know how to do—and still not getting what you want—is heartbreaking.

But the only way to address a problem is to first honestly acknowledge what’s really going on.

2. Step Away From the Ego

So many of our jealousies are just plain silly. As already mentioned, art is far more cooperative than competitive. Resentment of another writer’s success is often (always?) counter-intuitive. (If you write an amazing story and I read it, I am going to be that much more likely to write a better story myself thanks to the gifts your story has given me. And then, of course, there’s the fact that if a reader reads and loves your amazing story, they’re going to be that much more pumped to read another amazing story—and maybe they’ll read mine!)

But the ego isn’t always sensible. Certainly, it isn’t easy to overcome. Just realizing and admitting a) the undeniable reality of the ego’s demands and b) it’s often childlike short-sightedness is a huge step toward redirecting its power.

Looking at the bigger picture (of life, art’s role in life, and our role in art) is a helpful re-centering trick. Humility is inevitable when we are honest about how infinitesimal each of us is within that larger picture (and yet, how each of us, supplies an inevitable butterfly effect). It then becomes easier to recognize and embrace the contributions of our fellows, rather than feeling threatened by them.

3. Act on What You’ve Learned About Yourself

Once you’ve dug down deep inside yourself to discover what’s at the root of your writer’s jealousy, you will have gained information you can act on. You’ve faced down your insecurities. Maybe what you’ve found is something as surface level as My characters aren’t as good as my writing buddy’s characters! or something as deep as I will never feel worthwhile unless I can write an acclaimed book!

More than that, you’ve discovered uncluttered truths about what it is you want: to be published, to be a bestseller, to win an award, to impact readers of a certain group, to write for the pure joy of it.

Your jealousy has given you an indication of your progress. It tells you you’re not yet where you want to be. It’s a road sign, saying “120 miles to Graceland.” You’re not there yet. But you are on the right road. Congratulate yourself—and keep driving.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you ever struggle with writer’s jealousy? What do you do about it? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/writers-jealousy.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Writer’s Jealousy—And 3 Thoughts on What to Do About It appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 13, 2018

How to Market Your Book–When You Hate Marketing

Writers these days don’t get to think about just writing. If you want to learn how to sell your books, you must also think about marketing. And yet, most writers hate marketing.

Writers these days don’t get to think about just writing. If you want to learn how to sell your books, you must also think about marketing. And yet, most writers hate marketing.

Popular marketing wisdom, particularly within the last decade, says newbie authors should start building marketing platforms before they’re ever published. Start a blog, start a podcast, start a YouTube channel. Get active on Twitter. Build an email list.

This is something I’m frequently asked about. I get emails from authors saying,

I’m just starting to write my first book. What can I do to market it?

The sense from most of these authors is a little confused, sometimes even a little desperate. “Do I really have to do this?”

Writers know marketing is inevitable if they want to sell any copies and make any money. And yet, I daresay for almost all of us, there is this intuition that marketing isn’t just hard, it’s sometimes downright… icky.

Instead of trying to fully overcome that disconnect, I think it’s important to really look at it, to understand the nuances of the competing demands upon you, and to use them to refine a vision for how to sell your books without selling out.

3 Disconnects Between Writing and Marketing

These days, a writer is expected to be a marketer. This is absolutely true if you’re publishing independently, and only slightly less true if you’re publishing traditionally. It’s a dog eat dog world out there, baby. Millions of books are published every year. If your book is ever going to bob close enough to the surface to be fished out by readers, you must be prepared to equip it with some orange floaties.

Writers, like all artists, have long bemoaned the necessity of selling their work, in the active sense. We love to have our work validated by sales. But only the happy unicorns among us enjoy getting out there in the world with our sandwich boards to convince people our words merit a couple of their hard-earned dollars and a couple more of their precious leisure hours. Indeed, a profitable sub-industry exists within the writing world, designed to help frustrated and hapless writers find the techniques (and sometimes hacks) that will guide their books into Amazon’s Top 100.

It’s just one of the uncomfortable paradoxes of being a modern writer: writing and marketing go together about as well as oil and water—and yet go together they must. There are a couple reasons why this balance is so difficult.

1. Writing Is an Introverted Task; Marketing Is an Extroverted Task

Why’d you become a writer in the first place? Likely, it was because you had something to express and found the comforting solitude of expressing it within the metaphor of story to be the most natural mode. This doesn’t necessarily mean you are an introvert (although, odds are), but it does mean you’ve chosen to apply yourself to an introverted task. You’re good at it, and you’re doing everything you can to get better at it.

Marketing, however, is not introverted. Marketing demands you get out there, shake hands, kiss babies, and generally flaunt whatever you’ve got and sometimes even what you don’t got. This is where the major disconnect comes in for most artists. And with good reason. We’re basically being told that to be successful in our chosen field, we must go through a major personality transplant with every new book launch.

2. Art Is Genuine and Vulnerable; Marketing Is Not

Another disconnect is that, at least on a surface level, art and marketing seem to be polar opposites. Art is an expression of one’s genuine and vulnerable self. It says, “Here I am. Take me as I am or leave me as I am.”

Marketing, even at its most low-key, is about putting on a glitzy outfit and jumping up and down in the crowd to make sure you are the one noticed. Marketing is about making campaign promises that swear readers are going to love this book even before they’ve opened the front cover.

This “promise” is obviously problematic even when what the marketing is intended to sell is a BMW. But when you’re pitching something as undeniably subjective as art? That’s a false promise—and no one knows it better than the honest artist.

3. Art Is a Gift; Marketing Is a Sales Pitch

Those artists who make enough money off their art to allow them to create full-time are blessed. But I daresay few of us really write for the money. (If it was all about money, we’d ditch the writing and become full-time marketers, right?) We write because the writing is a gift to ourselves and, we hope, eventually a gift to others.

Marketing, however, is not about giving gifts. Under the guise of giving someone something they really want (and which, indeed, we hope they do), what we’re really trying to do is get something in return, whether it’s royalties or just the gratification of gaining a reader.

How to Reframe Ideas of How to Sell Your Books

Maybe you’re nodding your head, saying, “Yes! That’s exactly how I feel! Down with marketing!” And yet… the disconnect is still unresolved. It’s still there, for all of us, itching away with its dichotomous but undeniable necessity.

I believe that’s a good thing.

The disconnect’s not going away for any of us, and while that may not be particularly comfortable, I believe it’s an excellent sign. This deep-seated disconnect the artist feels with marketing keeps us honest. It keeps us focused on our true motives, reminds of our priorities, and, I believe, makes us both better writers and better marketers.

That brings me back to our initial question: When and how should you think about how to sell your books?

But I don’t want to answer that question. I could say the usual bit about not getting your wires crossed too soon, about focusing on finishing the book first, on first having something to share with readers so they’ll have a reason to listen when you start talking on social media and your blog.