K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 43

January 8, 2018

The 5 Secrets of Good Storytelling (That Writers Forget All the Time)

I’m having a harder and harder time getting excited about stories these days. Not because I don’t love stories, but because I do love them—and because it’s ever-increasingly difficult to find truly great ones that employ all the secrets of good storytelling.

I’m having a harder and harder time getting excited about stories these days. Not because I don’t love stories, but because I do love them—and because it’s ever-increasingly difficult to find truly great ones that employ all the secrets of good storytelling.

By “great stories,” I mean stories that are put together with intelligence, understanding, passion, and vision, so that we, as viewers and readers, have the opportunity to react to characters and plots that both emotionally engage us and intellectually stimulate us. I bet I can count on my fingers and toes the number of stories—both books and movies—that have given me that experience in the last 5 years (and maybe longer).

Part of the reason for this is a corporate mindset (particularly in Hollywood) that hedges its bets with spectacle, instead of risking any chips on meaty storytelling. This, in turn, creates a vicious cycle in which new authors and filmmakers feel this is “the way to do it” and instinctively mimic these patterns. Much of the problem is simply a lack of understanding in those telling the stories.

I’ll admit upfront this post was inspired by Star Wars: The Last Jedi—which I thought was an unmitigated mess. Do I believe director Rian Johnson and others involved in its production were copping out to sheer spectacle just to chase the money? No, I don’t. I think these people love Star Wars as much as I do and sincerely wanted to tell a story that was, in every way, as great as the original trilogy.

Unfortunately, however, they missed the mark on several fundamental levels of good storytelling—as do so many high-profile stories these days.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that, as writers ourselves, we have the opportunity (and the responsibility) to learn from these highly visible mistakes and use them to create better stories in the next five years and beyond.

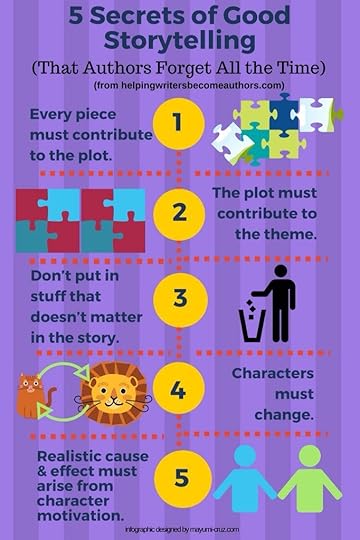

The 5 Secrets of Good Storytelling

Today, I want to talk about five principles of good storytelling. By “principles,” I mean basic storytelling truths that ring true in every story. If you want to write a good book or screenplay, these principles aren’t optional. There are more than just these five, of course, but these are arguably the most basic, and therefore the most important. They are also, unfortunately, the five principles I see neglected most often in well-meaning fiction that wants to hit the mark but lacks the grounding in strong story theory and application to make it happen.

All of these problems are blatantly on display in The Last Jedi. However, I’m not going to use direct examples from the movie—mostly because I don’t want to argue every point with viewers who were able to get past its problems and enjoy it. At the end of the day, viewer/reader enjoyment trumps any logical argument. If you enjoyed this movie, I’m happy for you. I wish I had too! I’m not trying to take away from that enjoyment.

But I would also encourage that you can and should be writing better stories than this. You can do that by starting with these five important not-so-secret secrets of good storytelling.

1. Every Piece Must Contribute to the Plot

Story is a unit. In order to be a unit, it must be cohesive. This is true most obviously on the level of plot and structure. Every piece—every scene—must link together, like a circle of dominoes, to create a unified chain of cause and effect. Any extraneous scene or plot twist will, at the least, be a speed bump in your readers’ journey through your story.

This is true of more than just scenes and structure. It applies to every element in your plot.

I’m always looking for ways to repeat motifs, pay off even the slightest bit of foreshadowing, and reuse settings and props in thematically meaningful ways. Most stories can support a few loose ends, but a good motto for any writer is: Everything matters.

This is nowhere more true than of your characters. Characters are the drivers of your plot, but more than that, they are the symbolic and archetypal representation of your theme (something Joseph Campbell helped George Lucas implement brilliantly in the original Star Wars trilogy).

As a result, every character needs to matter. You can’t just dream up a cool character, stick him in the story for a few scenes, then write him out or kill him off. That kind of character is like the nice guy who helps you jumpstart your car and then walks out of your life forever; his contribution to your story makes no lasting impression and his role could just as easily have been played by any other of a million passing strangers.

Check Yourself:

Structure gives you an easy way to determine whether you’ve added an integral story element or an extraneous one. The defining moment in any story’s structure is the Climactic Moment, which definitively ends the conflict.

Everything builds up to this. If you can delete a character, scene, or plot device and still get to your Climactic Moment in good shape—then you don’t need that character, scene, or plot device. However cool it may seem or however much fun it may be to write, it is dead weight in your story.

2. Plot Must Contribute to Theme

Writing a cohesive plot is a major step toward writing a story that can at least keep its feet under itself. Many fun “situation” stories never go farther than that. But if you can go farther, if you can take your story to another level, then why wouldn’t you?

That’s where theme comes in. Truly great stories aren’t just entertaining; they are emotional journeys that leave their viewers/readers changed in some way, however large or small. In order to accomplish this, the plot must be engineered to contribute organically and integrally to a theme.

These days, however, theme is the orphaned child of the storytelling world. Everybody tries to be kind to it, but because nobody knows quite what to do with it, it mostly just ends up sitting in the corner playing by itself. It kinda/sorta seems like it’s in sync with the rest of the big, boisterous family, but all their attempts to truly accept and include it are just… awkward.

Just as your Climactic Moment should be the light at the end of the tunnel that guides your every decision about what plot elements to include, your theme should be the lighthouse that guides the plot itself to a meaningful and resonant destination.

Usually, plot comes first in stories, and because the storytellers have no idea how to mine that plot for a pertinent theme, they end up, at best, with a scattered mess that fails to offer any important commentary on either the characters’ struggles or, as a result, the viewers/readers’ own lives.

This gets even more complex when you realize the more characters and plot lines you’re including, the more important it is to weave all this stuff together to reach one meaningful thematic ending for all of it.

Check Yourself:

What is your story trying to say?

And, trust me, every story is saying something. There’s no such thing as “just a story.” Frankly, that is a naïve and irresponsible cop-out.

The real question is whether you will dig down into the hearts of your characters, be brave enough and disciplined enough to figure out what it is you’re really trying to say, and then do the often messy and difficult legwork of creating a character arc and plot that serves the theme—rather than the other way around.

In his essay in Light the Dark, Jonathan Franzen offers a challenge to every writer:

In his essay in Light the Dark, Jonathan Franzen offers a challenge to every writer:

I’m trying to monitor my own soul as carefully as I can and find ways to express what I find there.

3. Stuff Can’t Happen Just to Have Stuff Happen

Storytellers notoriously get sidetracked by shiny baubles.

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to read the transcripts from the story planning sessions in which Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Lawrence Kasdan met to discuss Raiders of the Lost Ark. I get an endless kick over how Lucas and Kasdan are calmly working their way through ideas and plots to arrive at the story basically as we know it—and all the while, Spielberg just keeps on throwing in all these wild and crazy ideas, like a little kid having the best time playing make-believe: “Oh, and then you know what would be really cool? We should have a giant boulder come out and squish this guy!”

It’s hilarious mostly because it’s so relatable. We’re all Spielberg. Not only do we want our stories to be as cool as possible for our readers, we’re also just really excited about the cool possibilities for ourselves.

But beware of cool. Cool is seductive and can lead far too easily to stories that are chock full of stuff—but stuff that doesn’t matter. And without meaning, cool really isn’t that cool.

This temptation is especially dangerous for speculative writers. The endless possibilities of science fiction and fantasy provide us the opportunity to throw in all kinds of cool stuff just because it’s cool. But as another Spielberg character says in Jurassic Park:

They were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.

Check Yourself:

Why are you adding that gnarly new character? Why did you characters travel to that exotic new setting? Why have you included that funny little subplot? If your primary answer is Because… it’s cool?, stop and take a second look.

There’s no reason you can’t include all that cool stuff, but first you’ve got to make it matter to the story. It’s got to be so integral to the plot that if you yanked it, meaning would be lost. Even better, it needs to resonate on a thematic level. It needs to offer more than coolness; it needs to either ask questions or provide answers.

There’s nothing I love more than long, complex books or movies… when they work. When all that complexity comes together to create the warp and weft of a magical whole, it’s too delicious for words. But there’s also nothing I hate more than long, messy books or movies that drag me through the authors’ self-indulgent refusal to recognize and discard meaningless elements. This is even true of stories in which the pieces are great but ultimately detract from what might otherwise have been an even better whole.

4. Characters Must Change

Okay, I’m harping a lot on meaning. Stories have to have meaning. But sometimes that seems like a pretty vague directive. Authors are so deep in their own stories it’s often hard for them to know how to look for objective meaning. After all, the very fact that we are writing this thing means it’s already pretty darn meaningful to us.

The single easiest way to determine whether your story as a whole has meaning, or whether any particular element of your story contributes to that meaning, is to look for the arc of change within your story.

Story events that matter create change, either in your protagonist or the world around her. Lots of stuff can happen in a story, but if it doesn’t affect important and lasting change, then it’s just “sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Check Yourself:

Compare the beginning and ending of your story. What’s different? Which of your characters’ beliefs about the world have changed? How has this created change in their external actions? How have their external actions created change in the world around them? How have they changed physically? How has the world around them changed physically?

In answering these questions, look past the surface clutter. Maybe your characters fought an epic battle and a bunch of them died. At first glance, that seems like change. But unless that battle has changed your characters’ goals or proximity to those goals, nothing has changed.

This is often a particular challenge in series, since authors need to find a way to bring protagonist and antagonist into a climactic encounter in every story—without actually ending the conflict until the final installment. But the conflict must be advanced in each encounter; otherwise that particular installment is meaningless within the series.

5. Realistic Cause and Effect Must Arise From Character Motivation

Particularly in a plot-driven story, it can be easy to get so caught up in the external action that you fail to create meaningful character-driven reasons for those actions. You can’t have a solid plot without solid character motivations; it simply doesn’t work.

Characters can’t be at war just because, hey, wars are dramatic and interesting. Characters can’t recklessly dive into conflict just because, hey, reckless heroes are awesome. Characters can’t fall in love just because, hey, they’re both adorable, so why wouldn’t they fall in love? The more intelligent and experienced your characters are supposed to be, the more and more important this becomes.

Check Yourself:

If your Climactic Moment is the guiding light at the end of the story, then your characters’ motivations are the catalyst that sends them in search of that light. Those motivations need to be checked and double-checked in every scene you write. Are you characters making these decisions and executing these actions because they are in total alignment with their mission statements—their motivations—or are they deciding and acting like that just because it’s convenient for the plot and will let you stick in some cool “stuff”?

It is the author’s foremost (and arguably only) job to serve the story. That starts and ends with crafting meaningful character motivations and then adhering to them with honesty and conviction at every step.

Created by Mayumi Cruz.

***

Good storytelling should be hard—not because it’s impossible, but because it is a high-level skill that requires understanding, insight, energetically clear thinking, and absolute discipline when it comes to choosing elements that will support a worthwhile vision while rejecting those that detract.

Storytellers like you have the ability to rise above mediocrity, step into an understanding of the larger world of storytelling, and write the kind of stories that will save the galaxy. You’re our new hope.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you think is the most important secret of good storytelling? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/5-secrets-of-good-storytelling.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post The 5 Secrets of Good Storytelling (That Writers Forget All the Time) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 1, 2018

4 Life-Changing New Year’s Lessons for Writers

It’s weird, but I actually don’t like goals. Why does someone like me, who has always thrived on productivity, schedules, and forward momentum, not like goals? This morning, I realized it’s because the word “goal,” is associated with ideas of “yikes, that’ll be hard,” “probably won’t happen,” “doesn’t sound fun,” and “this isn’t really something I have much control over anyway.”

It’s weird, but I actually don’t like goals. Why does someone like me, who has always thrived on productivity, schedules, and forward momentum, not like goals? This morning, I realized it’s because the word “goal,” is associated with ideas of “yikes, that’ll be hard,” “probably won’t happen,” “doesn’t sound fun,” and “this isn’t really something I have much control over anyway.”

Sure, I have plans for every new year. But I’ve never considered them “goals.” Write 50-100 blog posts, record 50+ podcasts, write a book, publish a book, work out five days a week. I don’t look at any of these things as goals. They’re more like… future realities. Insofar as they are in my power and barring unforeseen events, they will happen.

Goals, on the other hand, have always been things like “be happy,” “don’t gain any weight,” “stay healthy,” “be nicer.” They’re things that are a little harder to control—and therefore always seem like setups for failure.

Instead of goals, this year I’d like to focus your attention on something else. Instead of good, but vague, wishes for the future—or even quantifiable plans for things you want to get done—what I want to focus on is the lessons of the past year, and how we can move forward in building upon their foundation.

What Did You Learn Last Year?

The major problem with most New Year’s goals is that they have no foundation. We’d all like to be smarter, healthier, prettier, kinder, and richer this year. But without some of kind of meaningful foundation of life experience and understanding, these are just birthday wishes—gone in the puff of a pink candle.

As Mater says in Pixar’s Cars,

Can’t know where you’re going until you’ve seen where you’ve been.

Focusing on the lessons you learned in the last year will show you the obvious next step for the new year.

For me, the last year and a half has been a watershed period of personal epiphanies and life changes. So many things I’ve always taken for granted about life, the world, and myself were challenged. Some mistaken ideas were shattered in painful but liberating ways. Others were reaffirmed.

None of this was even on my radar as a goal. It just happened. But it now gives me the opportunity to step forward into the new year, not with more goals, but with my life pack full of new ideas and experiences.

In a minute, I’m going to share some of my specific lessons from the last year, but for now, take a moment to consider what the last year taught you. Instead of looking back and judging the goals you might or might not have accomplished, consider what gifts you’ve picked up along the way during your adventures this year.

How are you different this January 1st from who you were last January 1st?

How is your life different?

What have you lost?

What have you gained?

What would you never want to trade from this past year’s experiences—whether it’s something beautiful or painful, or both?

What mindsets have served you particularly well this year?

What mindsets have failed you?

What answers do you feel you have found?

What questions are you still left with?

Plans for the future are great, but I’d venture that the answers you’ll glean from these questions will serve you far more valuably in shaping a fruitful new year.

4 Life Lessons That Should Be New Year’s Goals for Writers

As you’ve probably gathered by this point, this is not going to be one of those posts that tells you to commit yourself to writing two hours a day every day, or finishing at least one first draft this year, or putting aside four hours every week for social media, or trying to get at least one reviewer for your book every week. Or, or, or—that list could go on and on.

What I’m talking about here are life lessons more than writing lessons. But can you really have one without the other? Productive, centered writing habits grow out of productive, centered lifestyles. But, even more than that, the lessons of our lives are the very stuff of fiction. We can have nothing of worth to share with readers unless we are, first and foremost, focused on living the lives of seekers.

As writers, we must be people who are committed to seeking understanding in our own lives, being honest about the good and the bad, and embracing the little truths so we can move forward toward the larger Truths.

To that end, I want to share the four major “lessons” I feel I’ve learned this year. None of them are revolutionary. We’ve all heard them before, time and again. We all nod at them sagely: “Yeah, yeah, carpe diem, man!” But I’m here to tell you there’s a vast difference between agreeing with these ideas and getting them. This is the first year I feel I’ve gotten them. Every single one of them is beautiful, liberating, and empowering—all the more so because I’ve spent so many years unconsciously (and stubbornly) fighting them. Now, I can’t wait to see where they lead in the next year.

1. Stop Equating Productivity With Success

A few Christmases ago, while watching Scrooge fling his window open upon a bright new Christmas morning, I found myself asking: But was his life still a failure since his revelation didn’t come until the end?

I think it’s safe to say that anyone who has every read or watched this classic tale of redemption would respond with an adamant no. Indeed, the whole point of Scrooge’s story is that it’s never too late.

And yet, we are obsessed with the idea of earning success (in essence, buying salvation through works). I’ve talked before about how the revelation that equating productivity with success is an utterly wrongheaded, soul-sucking, ultimately self-defeating idea.

For me, this idea was probably the most life-changing in a life-changing year. It has changed everything about how I look at my life: from work to art to relationships. Instead of chasing after ideas of success that were largely self-imposed (and usually impossibly vague and ever-changing), I am now focusing on stepping back from the chronic diseases of over-achievement, perfectionism, and workaholicism—and their inherent symptoms of fear (what if I’m not good enough?) and guilt (I’m not good enough).

Takeaway: Instead of focusing on goals (and feeling like a failure when you don’t achieve them), focus on staying centered in each day and each moment. Life is not made up of checkmarks on your to-do list. It’s not even made up of landmark events, such as book releases. It’s made up of moments. Successful moments create successful lives.

2. Say “No”

My journey to saying “no” was kind of backwards. I started out as a bossy, blunt, aggressive oldest child. I had to work at being nice. I had to learn to be generous. I had to practice being patient, choosing the right words, avoiding hurting people’s feelings. And, honestly, I got pretty good at it. But it also got to a point where I was constantly overcompensating. In my 20s, I forgot how to say “no”—or, when I did, I felt terrible about it, like I was an incredibly selfish person.

The result was, inevitably, that I took on too much, said “yes” inauthentically, and started to go into pain-reflexed flinches whenever I could sense requests coming on. (But, hey, at least I was nice, right?)

Partly as an outgrowth of my new view of productivity (I don’t have to take advantage of every opportunity that passes in front of me) and partly as a result of a better understanding of boundaries (thanks in no small part to this fantastic book), I have slowly been saying “no” more and more often this year.

And I have never felt freer. It’s as if a huge burden has lifted off my shoulders. Now when I say “yes,” I’m doing it from a place of joy rather than guilt.

Takeaway: What saying “no” really means is saying “no” to yourself. You can’t protect your personal boundaries from the demands of others until you’re first willing to protect them from yourself. Evaluate the reasons you feel compelled to say “yes” even when your heart isn’t in it. What you find may not be pretty, but addressing it is the first step to a freer, happier, more empowered life.

3. Follow Your Bliss

I think, deep down, I’ve always embraced this masochistic idea that if something wasn’t hurting, just a little bit, then I was doing it wrong. If I wasn’t giving it 110%, then I was a weakling or a coward who was wimping out.

The result of that pretty little idea was that by the time I hit 30, I was basically a mess of repressed emotions, frazzled nerves, and just general befuddlement about what I was doing and why I was doing it. But then life did what it does best—it knocked some sense into me.

Why on earth would I think it was a good idea to spend my life doing stuff that made me miserable? I went through a couple months last year where I just didn’t have the energy—mentally or physically—to do much more than lie in a hammock and read. And by the time I got my legs back under me, I found myself looking around and going: “Hey, this is actually really nice. The world didn’t implode just because I wasn’t working like a maniac—and, would you look at that, there’s actually life beyond the desk.”

For a while now, I’ve been interested in the 80-20 rule (the idea that 80% of your results come from 20% of your effort), but I was never brave enough to really start implementing (what if, after all, I stop doing the wrong 80%?). But relinquishing my death grip on the importance of “success” has given me the courage to step back and start figuring out which things in my life are really important to me.

Takeaway: Turns out all the 80-20 rule really means is “following your bliss.” Yep, who knew, right? Basically, if you like doing it—if it makes you happy—do it. If you don’t like doing it—if it’s a burden on your soul—then that’s a sign you need to step back and figure out what it would really mean if you just stopped doing it. Chances are good not much would happen. If, however, there are sizable consequences, then it’s time to stretch that writer’s imagination of yours and start looking for alternative solutions.

4. Live in the Moment

You’re probably beginning to realize all these lessons are directly connected. Certainly, the whole carpe-diem thing is directly tied into the idea of following your bliss.

For me, I wasn’t able to fully understand or inhabit the concept of living in the moment until I had integrated the previous three lessons. But, really, what they were all about was getting to the place where I could grasp what it meant to live in the moment.

There are so many aspects to this—from just being aware of your body to coming to peace with past bitternesses to rejecting unreasonable fears of the future. But the aspect that has been most meaningful and powerful for me has been the realization that I needed to stop putting my life on hold.

That sounds like a huge statement—like what I really mean is “sell everything you own and go on a backpacking trip around the world.” Honestly, that’s what I always thought that meant, which is probably one of the reasons it took me so long to embrace it.

What I’ve found, however, is that this idea of “living my life now” is really all about the little things. It’s about being the person you want to be now instead of tomorrow. For me, this took on some external manifestations. I don’t think it’s any kind of coincidence that this was the year I remodeled half the house, donated truckload after truckload of stuff to Goodwill, and, for literally the first time in my life, paid more than passing attention to the style of clothes I was wearing.

Takeaway: If something you’re doing is making you miserable now, then why are you doing it? If the person you look at in the mirror seems like a stranger, then ask yourself why there’s this disconnect between how you feel and who you are. Finding the “center of life” will be different for all of us. Some of us need to stop doing the wrong things. Some of need to start doing the right things. Or both. Neither are easy, but they will lead us onto the path of a regret-free life.

***

This year, I encourage you to step back from the all the New Year’s goals for writers. By all means, make plans. Create schedules and outlines that will generate the future realities you desire. But instead of focusing on the intangible “should-dos,” focus instead on what the last year has taught you, as both a writer and a person, and how those lessons can become stepping stones to even more lessons next year.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What was your greatest takeaway from 2017? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/4-life-changing-new-years-lessons-for-writers.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 4 Life-Changing New Year’s Lessons for Writers appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 25, 2017

Wordplayers: Merry Christmas!

Merry Christmas, Wordplayers! I hope you are enjoying a beautiful day with your families and loved ones today. For me, this is, above all, a holiday of Thanksgiving, in which I am given plentiful opportunities to remember God’s blessings of abundance in my life.

Merry Christmas, Wordplayers! I hope you are enjoying a beautiful day with your families and loved ones today. For me, this is, above all, a holiday of Thanksgiving, in which I am given plentiful opportunities to remember God’s blessings of abundance in my life.

A huge part of my life is this website and all of you who read it, comment on the posts, and form the wonderful Wordplayer community.

I am deeply thankful for all of you—whether you’re someone with whom I toss around ideas and look to for advice, someone I chat with on a regular basis, someone who sends me funny Pinterest pictures, someone who has sent a kind note of encouragement or camaraderie, or just someone reading silently and sharing my life and my love of stories from afar.

You have changed my life, in countless ways. You have broadened my horizons and opened my mind and my heart. You challenge me, every day, to be both a better writer and a better person.

Thank you for being who you are, and thank you for being here.

Merry Christmas!

The post Wordplayers: Merry Christmas! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 18, 2017

Top 10 Writing Posts of 2017

We’re hurtling toward the end of the year, which means it’s time to hit pause, amidst all the winter festivities, and take a look back at 2017.

We’re hurtling toward the end of the year, which means it’s time to hit pause, amidst all the winter festivities, and take a look back at 2017.

For me, this has been a vastly different and vastly important year. As I talked about in the post “6 Lifestyle Changes You Can Make to Protect Creativity,” one of the greatest lessons I’ve learned is that of slowing down and appreciating the journey more than the destination. As a a result, 2017 hasn’t been a wildly productive year for me in so many obvious ways. And I feel like it was maybe my best year yet.

My personal highlights include:

The release of the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software, along with developer Bob Miller.

The publication of the Creating Character Arcs Workbook

Partial first draft of my portal fantasy sequel Dreambreaker

Visiting family on several different trips

Completely remodeling my basement, including my office

In the spirit of continuing down this new path of nurturing my creative life and smelling the roses, my goals for next year are also reasonably modest. At the top of the list is publishing my superhero historical Wayfarer (think Spider-Man meets Charles Dickens) next fall or winter, as well as finishing the first draft of Dreambreaker and maybe starting the outline for the third and final book in the series. Plus, I’ve also got some more travel plans up my sleeves.

My Top Writing Posts of 2017

But before we get too far ahead of ourselves (my specialty), let’s take a look at what were, according to your pageviews, this website’s top 10 writing posts of 2017.

1. 5 Rules for How to Write a Sequel to Your Book

2. How to Calculate Your Book’s Length Before Writing

3. How to Outline a Series of Bestselling Books

4. The Lazy Author’s 6-Question Guide to Writing an Original Book

5. The Great Novel-Writing Checklist

6. Top 10 Ways to Rivet Readers With Plot Reveals

7. The 7 Stages of Being a Writer (How Many Have You Experienced?)

8. 5 Misconceptions About Writing That I Used to Believe

9. Are You a Writer or a Storyteller?

10. 3 Ways to Choose the Right Protagonist

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What was your biggest writing breakthrough in 2017? Tell me in the comments!

The post Top 10 Writing Posts of 2017 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 11, 2017

My Top Books of 2017

When you’re a writer, stories are life. You can’t create them without ingesting them. That’s why Stephen King famously said:

When you’re a writer, stories are life. You can’t create them without ingesting them. That’s why Stephen King famously said:

If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.

That’s why this annual look back at my top books of 2017 is always one of my favorite posts. For better or worse, however, this year was the “worst” reading year in my entire life, in terms of quantity. I said that last year when I’d read only 80, but this year I really mean it. I’ve topped out at just 42 books read, which for me seems like a really dismal number. The good news, however, is that amongst those 42 books were some really good ones.

Following is my list of my top 5 favorite books in both Fiction and Non-Fiction, with a few bonus writing-craft titles thrown in.

But, first, some fun stats:

Total books read: 42

Fiction to non-fiction ratio: 20:22

Male to female author ratio: 28:14

Top 5 genres: History (with 10 books), Classic Fiction (with 9), Fantasy (with 5), Writing How-To (with 5), and Historical (with 3).

Number of books per rating: 5 stars (3), 4 stars (20), 3 stars (10), 2 stars (9), 1 star (0).

Top 5 Fiction Books

1. Blood Song by Anthony Ryan—Read 3-26-17

Loved it. It’s not as flashy as, say, Brent Weeks, but this is an incredibly thoughtful, well-realized, steady, and thoroughly enjoyable epic fantasy. The protagonist is one of those rare “good” characters that manage to be utterly sympathetic, engaging, and heart-rending (so much so that he was one of the inspirations for this post: “5 Tips for Writing a Likable ‘Righteous’ Character“). I can’t wait to start the sequel soon!

2. Among the Flames by Kim Vandel—Read 6-12-17

Kim Vandel has rocketed onto the elite list of my favorite authors. She has a solid style, a masterful control of character and subtext (which inspired this post “4 Ways to Amplify Your Characters’ Subtext“), a way of making even mundane details interesting, and a great slant on supernatural YA. My only true complaint about this second installment in the series is that it’s too short. I could happily have handled five hundred more pages of Kate and company. As it is, I must suffer heroically through another year of waiting for the sequel. At its heart, this is a romance—and yet, there’s no romance in either this book or the previous one. And that’s half the charm. Vandel is doing what so few authors have the patience or the guts to do in creating a long-lasting, evolving relationship that relies on characterization rather than gratuitously rushed romance. Again, can’t wait for the sequel!

3. Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett—Read 10-9-17

Sublimely hilarious, beautifully plotted (you can find my structural analysis in the Story Structure Database). Peopled with a delightful cast, most notably the charmingly heroic and lovable Carrot. My favorite Pratchett book so far.

4. Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell—Read 3-13-17

I love it when things live up to their reputations. This book is a tour de force in so many ways. Structurally, it’s amazing—which is, I think, the largest reason it’s so incredibly readable, even at its great size (you can read my structural analysis in the Story Structure Database). The characters are well-realized, the themes deep and nuanced, and the historical viewpoint certainly thought-provoking. It has its downfalls, of course (most notably its wretched portrayal of African-Americans), but overall, it’s a charmingly satirical novel that demands introspection from the reader in regard to the intervening ebb and flow of history.

5. Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann—Read 2-16-17

What an extraordinary book. Thomas Mann—even translated into English—has such an immersive and yet easy style of writing. He’s a pleasure to read even when he’s not saying anything interesting, which he certainly is here with this deeply symbolic web of personality and history. Most interesting of all, however, is his deft use of a highly unreliable but entirely earnest non-protagonist narrator. I didn’t enjoy this quite as much as Magic Mountain (one of my top five books last year), but it cements Mann as one of my favorite classic authors.

Top 5 Non-Fiction Books

1. Boundaries by Dr. Henry Cloud and Dr. John Townsend—Read 6-6-17

This book is life-changing. Turns out a discussion of boundaries is really a discussion about every single relationship in your life, your personal self-worth and discipline, your childhood, and your religion. The good doctors come at this from a Christian perspective, but they pull no punches in addressing the massive problem Christians, in particular, have with these issues. At every turn, they are brutally honest, logical, and biblical. The end result is the encouragement and empowerment to live a centered life, free of guilt and balanced in God’s will.

2. This Fabulous Century: 1950-1960 by Time-Life Books—Read 2-16-17

I’ve yet to read any of this series that wasn’t interesting, but this is a standout. It’s a thorough, in-depth, and always educational overview of one of the most transitional decades in the 20th Century.

3. A Mighty Fortress by Steven Ozment—7-16-17

This is a rapid-fire historical overview of the German people that often reads like a fast-paced documentary. I would have enjoyed a little more depth in the exploration of personalities, but overall, this is an excellent big-picture view that offers some surprising insights.

4. Rasputin: The Saint Who Sinned by Brian Moynahan—Read 5-23-17

Like most of the world, I have always been fascinated by the murky half-myth, half-reality in which lurks the dark figure supposedly at the heart of the Romanov dynasty’s downfall. Moynahan brings clarity, forthright details, and a fair-handed approach that ultimately casts the largest share of blame on Empress Alexandra’s wrongheadedness.

5. Life Lessons by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler—Read 10-6-17

A beautiful book with interesting insights. Nothing unforeseen, but good reminders about what it really means to live a full and meaningful life with no regrets.

Bonus: 3 Books for Writers

1. Cover Design Secrets Bestselling Authors Use to Sell More Books by Derek Murphy—Read 5-16-17

Great advice, much of which goes against the grain, but is so sensible it makes you wonder why you didn’t think of it yourself. I learned much and appreciated Derek’s viewpoint. I will be approaching my future covers with a new perspective.

2. Dramatica Unplugged: The Story Mind by Melanie Anne Phillips—Read 4-14-17

Dramatica is such a complex system that it’s really helpful to break it into down into smaller chunks like this. Gave me new ideas to think about.

3. 5 Minute Book Marketing for Authors by Penny Sansevieri—Read 4-15-17

This is an excellent primer for writers just starting out with marketing and wanting a rounded plan of action for selling books.

My Books

And if all these goodies aren’t enough to fill your To Be Read pile this year, here’s a few more!

December 4, 2017

It’s Time to Buy Christmas Gifts for Writers!

I love this time of year. The holly-jollyness, the cookies, the company, the carols, and the presents! I adore shopping for presents. And, yeah, I like receiving them too. Once again this year, I’ve done a little shopping for you too. Check out my fourth annual list of the best Christmas gifts for writers!

I love this time of year. The holly-jollyness, the cookies, the company, the carols, and the presents! I adore shopping for presents. And, yeah, I like receiving them too. Once again this year, I’ve done a little shopping for you too. Check out my fourth annual list of the best Christmas gifts for writers!

3 Christmas Gifts for Writers Under $10

1. “Novelist at Work” Warning Sign

When I posted this on Facebook and Twitter a few weeks back, everyone was asking where they could get one. Here’s where!

Price: $8.99

2. Writer Street Sign

Mark your territory!

Price: $8.99 (+ shipping)

3. The Writer’s Muse Owl on a Typewriter Print

Get stylish with this upcycled vintage dictionary page book art.

Price: $9.99

11 Gifts for Writers Under $20

4. Aluminum Mousepad

Spruce up your office space with a little bit of shine. Available in gold, silver, black, and rose gold.

Price: $10.99

5. Typewriter Coaster Set

Park your coffee in style.

Price: $11

6. “Keep Clam and Proofread On”

Need I say more?

Price: $12.85

7. Typewriter Patent Print

Does anyone appreciate the guts of a typewriter more than a writer? I think not.

Price: $13.96

8. “This Is What an Author Looks Like” Journal

Proclaim yourself to the world when you take your writing on the go.

Price: $14.95

9. Zippered Leather Pen Pouch

Organize and transport your pens, pencils, and styluses in luxurious style.

Price: $15.88

10. “Writing Is My Superpower” T-Shirt

Who needs telekinesis when you can write?

Price: $15.99

11. “Just One More Chapter” Throw Pillow Cover

Perfect for both readers and writers.

Price: $16.99

12. “Keep Talking – I Am Taking Notes for My Next Book” Pendant

At least give your victims fair warning with this charm necklace.

Price: $19.00

13. Pen Engraved With William Shakespeare’s “To Thine Own Self Be True”

Pay homage to the bard while also reminding yourself of this most important of writing tenets.

Price: $19.95

14. Postcards from Penguin: One Hundred Book Covers in One Box

Stock up on appropriately themed stationary for the year.

Price: $19.99

3 Gifts for Writers Under $50

15. Custom Set of 5 Red Personalized Spiral Memo Notepads with Attached Pens

Does it get any funkier and cooler than this?

Price: $32.98

16. Handmade Leather Journal Set

Keep all your outline notes in this gorgeous journal, with pen and box.

Price: $36.94

17. Handcrafted Natural Bamboo Wooden Wireless Keyboard and Mouse Combo

Goodbye, plastic. Hello, gorgeous.

Price: $49.99

3 Gifts for Writers Under $100

18. Book Lovers Gift Box

Stock up on all the essentials: mug, tea, pencils and erasers, magnetic memo cards, nuts, cookies, and coffee.

Price: $51.95

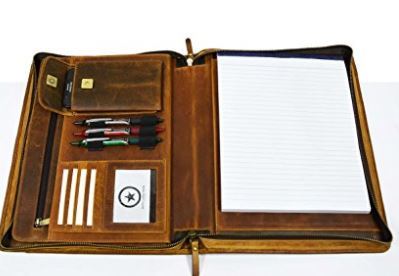

19. Premium Leather Business Portfolio and Professional Organizer

Keep all your gear in one easy place for whenever you want to take your writing on the go.

Price: $84.99

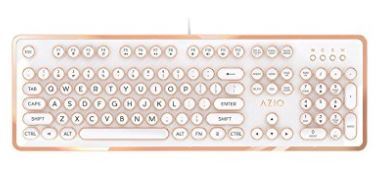

20. Retro Typewriter-Inspired Mechanical Keyboard

A little classy, a little steampunky, and a little vintage. What more could a writer want?

Price: $89.99

Bonus Christmas Gifts for Writers: Writing Books

And if you still haven’t found the right gift for your list or a fellow writer’s this year, you can’t go wrong with the gift of learning. You can check out my full list of Recommended Reading for Writers and my own series of writing books below. Merry Christmas, everyone!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Which of these gifts for writers is at the top of your Christmas list this year? Tell me in the comments!

The post It’s Time to Buy Christmas Gifts for Writers! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 27, 2017

How to Write Funny

Part 17 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 17 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

If you ask me, the trifecta of must-have story elements are: relationships, action, and humor. Of the three, arguably the most difficult is learning how to write funny. You can’t fake humor. It either works or it doesn’t.

This might prompt some writers to avoid it out of insecurity with their ability to pull it off. But don’t do that either. Well-executed humor won’t just make your story more entertaining, it will also offer the ability to bring greater depth to almost every other aspect of your story—including character, theme, and even plot.

Why? Because good humor is true humor. And when it’s true, it heightens every part of your story. Even the darkest story can benefit from not just humor itself, but an underlying understanding of what humor does and how it does it.

In Which Thor: Ragnarok Does Indeed Save the Trilogy

Welcome to Part 17 of our ever-expanding exploration of the storytelling techniques found in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The third (and conclusive?) installment in the Thor trilogy was much anticipated, not least because its addictive trailers hinted at a completely new take on the character. Happily those hints were fully paid off in a delightfully rompy movie that is not only easily the best of the three but also made a concerted and impressively successful effort to clean up its predecessors’ mess.

The Thor movies have always been the most problematic within the MCU. They’ve each struggled under a load of individual weaknesses that mostly stemmed from general confusion about what exactly to do with this character and his world. Muddy themes, overcrowded plots, and misplaced romances all contributed. Admittedly, I liked both Thor and Dark World, but that liking came mostly because I recognized the underlying good points of the characters and storylines—even though they weren’t fully executed.

But that was before director Taika Waititi, previously known primarily for his brilliant indie film Hunt for the Wilderpeople (oh yeah, and Team Thor), took the reins, took over, and took it to the house. He course-corrected the Thor storyline with a radical change of direction that refocused the story on the character’s strengths (hello, dorky humor) rather than trying to make him into something he never should have been (goodbye, epic lover).

I feel like I say this in preface to every Marvel post, but: this is not a perfect movie. As is par for the course, its villain conflict is largely ancillary. It’s a little scattered in places. And some might argue it changes tonally too much. But bottom line (and I know I say this all the time too): I loved it. It was ruthlessly fun, knew exactly what it wanted to be and what it should be, and closed off the character’s thematic arc in a deeply satisfying (if cursory) way.

Almost all of that was due to Waititi’s masterful understanding of humor-driven storytelling.

But before we dig down into what we can learn from his chops, here’s my highlight reel:

Hela. Is Cate Blanchett ever not awesome? Other than the fact that she looked Ragnarokin’ (see what I did there?) in every scene, I really loved the little plotline that made her Thor’s unknown older sister. It made very personal what would otherwise have been an even more ancillary conflict, as well as neatly mirroring some of the earlier thematic elements with Thor’s relationship to Loki—not to mention giving Odin new and interesting complexities. I wish she could have been developed more, but, hey, villains never have been Marvel’s strong point.

More Loki. Finally! From Day 1, Tom Hiddleston has been the bright center of the Thor movies, despite being sadly underused in almost all of them. But finally, he was brought on board as a main character and, even better, a main supporting character rather than an outright antagonist. This not only allowed for better development of the troubled brother relationship, but also gave Loki’s mischief-making duality the perfect playground.

Matt Damon. That little play Loki-as-Odin was enjoying when Thor first returned home to Asgard looked hilarious—but I honestly have no idea what it was about since I was too busy rubbernecking: “Is that Matt Damon? That looks like Matt Damon. That’s not Matt Damon, is it?”

Jeff Goldblum. Reportedly, when Goldblum came on board to play the Grandmaster, he asked Waititi: “Basically, you just want me to play Jeff Goldblum, right?” ‘Nuff said.

Waititi. Obviously, Waititi is this movie, from start to finish. But he gets extra props for also playing the entirely lovable leader of the Grandmaster’s “prisoners-with-jobs.” Plus: yay for Kiwi accents!

Valkyries. Because I totally agree with Thor: Valkyries are awesome.

Lightning. Raise your hand if you thought Mjolnir getting destroyed was a bad thing. Raise your other hand if you no longer think that. *chills*

No Jane. So this is kinda a highlight and kinda not. I loved Jane Foster in the previous movies, even while knowing she was one of the main reasons the stories never found their proper footing. So I wholeheartedly agree it was a good move axing her from this movie—but I wish they’d found a better way to do it than having her “dump” Thor, since that basically negates the whole point of the second movie.

The funnies. Why do we love this movie again? Oh yeah, that’s why.

How to Write Funny (Even in the Middle of an Apocalypse)

It’s not enough to write funny just for the sake of writing funny. Do that, and all you’ve got is a stand-up routine. In order for humor to contribute meaningfully, it must matter. It must be a carefully conceived technique that advances plot, character, or theme—or, preferably all three. Ragnarok nails them all, thanks largely to the following four tenets of how to write funny.

1. Be True to Your Characters

The best humor is character-centric humor. It’s humor that’s funny because it’s coming out of this person’s mouth. Put the same words in a different character’s mouth and the result just wouldn’t the same. It isn’t the joke that’s funny, it’s the character.

What this means, of course, is not every character can be funny. And no character can be funny in the same way as another character. You can’t superimpose the humor on top of the characters. Rather, you must dig down into the characters and find the funny that’s already there.

The only way to do this is to:

1. Be entirely aware of your character. Who is this person, really? Smart, dumb, strong, weak, brave, cowardly?

2. Love your character. Humor almost inevitably arises from making fun. If you’re making fun of a character from a place of disdain, it’s rarely as funny as when you’re doing it from a place of affection—and it’s much more likely to be offensive. But when you love your character not in spite of the personality traits you’re making fun of, but because of them—then you’ll find yourself in just the right environment to dig deep for the really funny stuff.

3. Make fun. Once you know and love your character, you get to exaggerate the larger-than-life personality traits that make this person interesting—because, really, that’s all humor is: something interesting that catches us off guard.

How Ragnarok Aced Its Characters

Honestly, up until Ragnarok, nobody at Marvel really seemed to know what to do with Thor. The best parts of his appearances in both his own movies and the Avengers’ movies were always thanks to the cheekiness with which Chris Hemsworth plays the character’s larger-than-life pomposity, bravado, and general obliviousness. The films kept trying to play up his epic-fantasy role as a warrior prince or star-crossed lover, and the results have always been mixed with more than a fair dose of corniness.

Until Ragnarok.

Waititi’s greatest triumph in this movie is letting Thor be Thor. Face it, in his best moments, the “strongest Avenger” has always borne more than a slight resemblance to an overgrown Lab puppy: big, destructive, overeager, and obliviously good-natured. Waititi saw that and took full advantage of it, letting Hemsworth turn loose his considerable comedic skills to make fun of the series’ most over-the-top character.

Although Ragnarok emphasizes this part of Thor’s personality far more than previous films (giving Ragnarok a completely different tone), it doesn’t invent any of this. It just takes advantage of it in an honest way to mine the humor that was always lying there under the surface.

2. Be Unexpected

Humor in a nutshell: the art of the unexpected. Learning how to write funny is largely about learning how to surprise readers by giving them something they didn’t see coming. Think the character is going to say this? Nope, she says the opposite. Think the character is going to react with anger? Nope, she’s actually laughing her head off. Think she’s gonna trip on that banana peel? Nope, she neatly dodges it—only to trip over the manhole cover.

In truth, this is really just the art of good writing, period. If readers can anticipate the end of your every sentence—if they know how one character is going to respond to the other before the words are out of her mouth—if they can guess the gag’s payoff from its setup—then it’s not only not funny, it’s boring.

This is true for every aspect of your story—from beat-by-beat action to the plot itself—but it’s perhaps nowhere more true than in dialogue. We see this especially in funny dialogue. When you’ve heard the joke before, it’s not surprising, and therefore not as funny (perhaps not funny at all).

With every sentence you write, you should be thinking twice about your first instinct: is it unexpected? is it entertaining? Even if it’s not meant to be funny, it should keep readers on their toes in exactly the same way humor does.

The Real Reason Ragnarok Was So Funny

Waititi’s brand of humor is all about the unexpected.

Think Thor’s going to throw that ball through the glass and escape the Hulk’s prison in heroic fashion? Nope, the ball’s going to bounce right back and smack him in the head in the middle of his epic speech.

Think the leader of the gladiators is going to be gnarly and nasty and make life miserable for Thor? Nope, he’s an adorable sweetheart who tried to start a revolution by printing pamphlets.

Think Thor’s going to triumph over the Hulk by using the Avengers’ “sun’s getting real low” code to bring Banner back? Nope, turns out he’s not quite as persuasive as Black Widow in that department.

Honestly, we could go through this movie beat by beat and talk about how almost every single moment makes use of the principle of the unexpected to hold its viewers’ interest, keep them entertained, and spark their laughter.

3. Give the Audience What They Want

At first, this one seems like a bit of a paradox. How do you give audiences what they want while also subverting their expectations?

Here’s the thing: your readers want to be surprised. But deep down, they want to be surprised by things they either subconsciously expected or consciously desired but were misdirected into feeling were unlikely. When you can set readers up to want something, then make them think they’re not going to get it, then circle back to give them exactly that in an unexpected way—they will love it.

Not all humor will be about pleasant things. There’s a reason the banana peel is a staple of physical humor. But often, the most enjoyable humor arises from giving audiences (and thus, characters) exactly what they want.

You have to be careful with this. Giving readers and characters what they want should never be straightforward. After all, if you keep giving characters what they want, you’ll run out of conflict fast.

Instead, give them what they want with complications. This is the essence of good scene structure. The character thinks he gains his scene goal—only to have it end with some disastrous complication. If you’re wanting to figure out how to write funny, this plays right into your hand. You get to delight readers with the outcome they wanted, while still surprising them and driving the conflict with unexpected eventualities.

How Ragnarok Gave Audiences Everything They Wanted

We might go so far as to say this is the principle that made this entire movie: this film was exactly what Thor fans wanted (a movie that worked), but in a way no one saw coming (a space comedy more in the vein of Guardians of the Galaxy than the previous Thor movies).

Waititi demonstrates this principle over and over again throughout the film. Perhaps the most blatant example is the Midpoint battle between Thor and the Hulk. The trailers unfortunately (if inevitably) spoiled this moment, but it was still awesome.

When the Grandmaster’s “beloved champion” bursts into the arena, we expect it to be some incredibly big, ugly monster. But what we want is for it to be someone we know. If it’s someone we know and love, even better.

So we’re both surprised and delighted when the monster smashing through those doors turns out to be the “innncreeeediiibleee…” Hulk!

4. Use Humor to Smooth Over the Rough Spots

There is no greater magic in storytelling than humor. It fixes just about everything (including crazy, mish-mashed plots, on occasion). This is especially true for your characters. As we talked about in our first point, above, humor is all about accentuating the extremes in your characters’ personalities. However, by their very nature, extremes are often problematic, sometimes even unlikable.

Your character is a jerk (hello, Tony Stark), a goody two-shoes (um, Cap?), a humorless bigot (Drax, anyone?)—no problem. A little humor greases those wheels, helps readers get past your characters’ less-than-attractive traits, and even eases them into the ability to empathize with and love these people for their faults.

But, again, this only works if you’re coming at your character from an “inside perspective” and using it to create situations that are self-deprecating. Creating humor from an “outside perspective” can also be useful, but instead of smoothing over the rough spots, it will serve to emphasize them—and not in a kind way. This can work when you’re making fun of truly awful traits or actions, but it is not a feel-good kind of humor and can easily cross the line into offensiveness. The former is about poking fun at ourselves; the latter is about making fun of “others.”

Why Ragnarok Gives Us Our Best Thor Yet

Like all of Marvel’s characters, Thor is a deeply flawed person. As the (essentially) immortal royal son of Asgard, both his strengths and his weaknesses are epically larger than life—to the point of cartoonish-ness on occasion. Particularly in his first movie, he was a short-sighted, arrogant, brawn-over-brains lummox. As Loki emphatically stated, “My brother is an idiot.”

One of the main reasons for the character’s struggles in previous appearances was that the movies tried to play him, in all his Asgardian glory, too straight. Humor was his only saving grace—which Hemsworth seemed to realize, even if no one else did. Wisely, he never took the character, or himself, too seriously and always played the Mighty Thor with a little twinkle in his eye.

Waititi recognized that and finally gave us a version of Thor that takes full advantage of the character’s undeniable silliness—which, ironically, also gives us what is, in my opinion, the most epic version yet. By using humor to acknowledge and lovingly joke about Thor’s extreme personality traits, the character becomes more realistic, relatable, and endearing. His pomposity becomes a joke on himself. His careless (and usually lucky) mistakes become a useful plot device. His oblivious destructiveness transforms him from an unbeatable immortal into a relatable klutz.

This is the Thor who’s always been there, but finally Waititi has pulled him out from under all the unnecessary baggage, dusted him off, and given him a proper chance to … sparkle.

***

Don’t be afraid of learning how to write funny. It is a teachable technique arising from the strong foundation of well-realized characters and story beats. Immerse yourself in your characters, look beyond plot cliches, and be honest about the story you’re telling. That’s all you have to do discover the kind of humor that will raise any story to the next level.

Stay Tuned: In February, we’ll visit the Black Panther in Wakanda for the first time.

Previous Posts in This Series:

Iron Man: Grab Readers With a Multi-Faceted Characteristic Moment

The Incredible Hulk: How (Not) to Write Satisfying Action Scenes

Iron Man II: Use Minor Characters to Flesh Out Your Protagonist

Thor: How to Transform Your Story With a Moment of Truth

Captain America: The First Avenger: How to Write Subtext in Dialogue

The Avengers: 4 Places to Find Your Best Story Conflict

Iron Man III: Don’t Make This Mistake With Your Story Structure

Thor: The Dark World: How to Get the Most Out of Your Sequel Scenes

Captain America: The Winter Soldier: Is This the Single Best Way to Write Powerful Themes?

Guardians of the Galaxy: The #1 Key to Relatable Characters: Backstory

The Avengers: Age of Ultron: The Right Way and the Wrong Way to Foreshadow a Story

Ant-Man: How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Your Story

Captain America: Civil War: How to Be a Gutsy Writer: Stay True to Your Characters

Doctor Strange: 3 Ways to Test Your Story’s Emotional Stakes

Guardians of the Galaxy, Vol. 2: How to Ace the First Act in Your Sequel

Spider-Man: Homecoming: 4 Ways to Write a Thought-Provoking Mentor Character

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Are you learning how to write funny in your work-in-progress? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/how-to-write-funny.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Write Funny appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 20, 2017

Tips for How to Choose the Right Sentences

What is writing but choosing the right words in the right sentences in the right paragraphs in the right pages in the right chapters? But even though words and sentences are the smallest of integers within our storytelling, they’re actually one of the most complex. How do you choose the right sentences? Is it a process with a rhyme and reason? How can something so small and instinctive be guided by conscious decisions? How do you learn to choose the right sentences in a way that makes you a better writer with every book you write?

What is writing but choosing the right words in the right sentences in the right paragraphs in the right pages in the right chapters? But even though words and sentences are the smallest of integers within our storytelling, they’re actually one of the most complex. How do you choose the right sentences? Is it a process with a rhyme and reason? How can something so small and instinctive be guided by conscious decisions? How do you learn to choose the right sentences in a way that makes you a better writer with every book you write?

It’s a common axiom among writers that “every sentence has to count.” Sounds good in theory. But how do you actually make sure each sentence counts? How do you judge a sentence’s worth and decide whether it’s so meaningful that the entire story couldn’t exist without it? I mean, that’s a lot of pressure for one dinky little sentence.

The best way to study this is to look at real-time examples. That’s why, today, I want to share with you part of a chapter from my portal fantasy work-in-progress Dreambreaker and show you how and why I’ve chosen each of the sentences.

Getting Ready to Choose the Right Sentences for Your Story

But, first, housekeeping…

Caveat: Now, of course, this is a work-in-progress, which means the sentences you see here may not be the ones I end up with in the final draft. But I’m not as interested in showing you how to edit your way to the perfect sentence, but rather how to recognize what your narrative needs, sentence by sentence, as you’re writing the first draft.

Choice of Chapter: I’ve chosen a chapter from the middle of the book (the First Pinch Point at the 37% mark), because I wanted to highlight an “ordinary” chapter. Chapters that open the book or introduce new POV characters are unique in their responsibilities (which we’ll talk about another day).

As a result, on the one hand, you won’t understand everything that’s going on, and, on the other, there may be some spoilers. Dreambreaker is the sequel to my portal fantasy Dreamlander (which you can grab for free). To help orient you a little bit, here’s the premise:

As the veil between our world and the world of dreams begins to rupture, the former “Gifted” Chris Redston, now shorn of his abilities, must struggle back to his lost love, the fierce and conflicted Queen Allara, and help her overcome dangerous international intrigue and discover the impossible truth about their still intertwined destinies—before a mysterious heretic can commit the ultimate abomination of permanently fusing the worlds.

Context: The setup for this chapter is that the Cherazii (a reclusive warrior race) have requested Chris investigate one of the rifts (portals that lead between worlds and from place to place within the same world) through which their people keep disappearing.

Cast:

Chris–protagonist, a “Gifted,” the only one of his generation who can consciously travel between worlds.

Allara–Queen of Lael and Chris’s love interest.

Worick–Chris’s dream-world dad.

Axion–Cherazim surgeon who requested Chris’s help.

Quinnon–Allara’s bodyguard, captain in the Green Guard.

Rordin Soller–the dream-world counterpart of Chris’s real-world best friend, Mike.

Green Guard–the Queen’s soldiers.

Yellow Guard–the Royal Council’s soldiers.

Key: The original text from the book will be bold and indented. My commentary is in regular text beneath each pertinent section. You can read the full except, without my commentary, here.

Real-Time Examples of How to Choose the Right Sentences While Writing

Dreambreaker

Chapter 22

As it turned out, nothing about this new rift was so simple after all.

This first sentence ties in directly with the last sentence of the previous chapter (She smiled, wanly. “Sometimes things aren’t that simple.” / “But sometimes they are.”). With this book, I’m trying a new little challenge of trying to incorporate a word from the last sentence of the previous chapter into the first sentence of the next chapter. It’s just a subtle way to transition between chapters, tie things together, and keep the flow going.

I also like to open chapters with a hook that creates some kind of juxtaposition or dichotomy—some sense that something is amiss. I want readers to be curious about why this new rift isn’t simple.

Note, also, how I begin in medias res. The characters are already at the rift and recognizing its issues. After planting this brief hook, I can then jump backwards and expound on the context in the sentences immediately following.

The closer Axion assured them they were getting, the deeper Chris’s sense of uneasiness.

I immediately need to start establishing the setting and the supporting characters. I want to indicate Axion is present, but because I don’t want to just say “Axion was there,” I have to reference him in a way that advances the story, expounds upon the previous sentence, and deepens reader interest. Here, I do that by tying in Axion’s presence to Chris’s state of mind.

But not until their horses rounded a bend in the road and startled a small herd of shaggy zajele into scrambling up the black rocky hillside did he realize where he was.

Now comes the setting. Instead of simply saying, “Chris was riding in the hills,” I want to describe via action. This also allows me to help readers envision the scene by indicating the characters are mounted. Since Chris has been in this place before, I use the word cues “black rocky hillside” to hark back to previous descriptions and help readers recall their previous mental image of this setting.

“No way.”

The earlier you can incorporate dialogue into a scene, the better. Dialogue is one of the easiest and best ways to enliven a scene. I also need to communicate Chris’s recognition of and uneasiness with this place, so other characters can respond to it—which, in turn, gives me the opportunity to indicate their presence and orientation in the scene.

Riding just behind him, his dad urged his borrowed horse into a trot. “What is it?”

Chris’s dad is a minor character in this story and hasn’t been present in many scenes up to this point. Therefore, I needed to indicate his presence as early as possible to keep from jarring readers. Choosing him to be the one to respond to Chris lets me do that while also further sketching the placement of all the characters in the scene.

Worick had showed up at the palace this morning just as Chris, Allara, and a Guardsmen squad were boarding the skycar that would take them the six hours to Virere Ford. One look at the sword on Chris’s hip and the Glock strapped across his chest, and Worick had paled beneath his swarthy tan. Grimly, he’d refused to be left behind.

Now that I’ve introduced Worick’s presence in the scene, via a little action, I have the opportunity to stick in a little exposition, indicating what happened in between chapters and why Worick is unexpectedly present. I make this paragraph pull extra weight by also explaining who else is present in this scene, how they got here from the setting in the previous chapter, how much time has passed, what Chris is wearing, and what Worick’s mindset and scene goals may be.

Now, he frowned. “What’s wrong?”

After the paragraph of exposition, I need to reorient readers in the present-time dialogue. I do this via Worick’s action beat and reiteration of his question.

Chris shook his head. “I’ve come through this rift before.”

Chris’s action beat reestablishes him as the second speaker. His dialogue reminds readers how he happened to be in this place before.

On his other side, Allara reined in a prancing Rihawn, and looked at him questioningly. “You had bones here?”

Allara enters the conversation at her earliest opportunity. She is introduced by an action beat that orients her position in relation to the overall setting and Chris in particular.

“No, I followed a friend from my world. His shadow lives here.”

This is necessary information for the other characters to know, but also for the readers to be reminded of, since the previous scene was relatively minor and happened some time back. It catches readers up to speed with what Chris has realized about this place.

Riding at the head of the column with a sullen Quinnon, Axion stiffened. He cocked his head, listening. “There is a gathering.”

Again, an action beat fulfills multiple duties by identifying the new speaker, orienting him within the setting, indicating the presence and position of yet another character (Quinnon), and advancing the plot by hinting something is about to happen.

Since there is no visual or auditory cue for Chris to access (Cherazii have better hearing than humans), the second sentence indicates how Axion realizes something is happening. His dialogue then sets up reader expectations for what is about to happen.

“Cherazii?” Allara asked.

Due to conversations in the previous chapter, readers might initially expect the gathering to be of Cherazii. Allara asks this question for them…

“I think not.”

…and Axion immediately dispels the misconception. This subtly sets readers up for what to expect by avoiding any unnecessary jarring or confusion when it turns out there will be no more Cherazii in this scene.

Chris strained his ears, but caught only the wind whistling amidst the crags. It took a full quarter of a mile more before he heard it too: an ominous murmur.

Readers may not remember that Cherazii have superior hearing and therefore may wonder why Axion is the only one to hear anything. Without blatantly telling readers this is so, I at least acknowledge that Chris can’t hear what Axion hears and hint at the range of Axion’s hearing by mentioning how long it takes until Chris picks up on the interesting sound.

The road took another curve around the hillside. To the left, farther down the slope, the rift’s metallic opacity glinted amongst the black boulders. As before, it hovered several feet above the ground. But now, it was three times larger.

Since the characters are moving, the setting needs to be advanced. The central interest in this setting is the rift, so I mention it immediately, with a few descriptors, to orient readers and give the rest of the description a central point around which to revolve. I also contrast the rift’s current appearance with how it looked the last time readers saw it—thus, advancing the plot in the subtlest of ways and foreshadowing events to come later in the chapter.

A hundred yards distant, where a few farmsteads came together to create a commune, two dozen villagers crowded the road. Mattocks and shepherd’s crooks over their shoulders, they shouted at the Yellow Guard platoon herding a line of chained outlanders through their midst.

Now that the characters are technically in a new setting, I need to take a moment to reorient everyone and describe the new features. The second sentence expounds on the first by including descriptors that work double time to indicate the villagers’ unsettled mood. I also indicate the presence of the Yellow Guard and why they’re there: because of their prisoners.

“Return them home!” a villager shouted.

Now that the orienting details are out of the way, it’s time to bring in the dialogue once again. By sharing snippets from the villagers, I’m able to do all of the following: hint at the raucous sounds of a shouting crowd, give the villagers some general characterization, and provide context for their altercation with the Yellow Guard—setting things up for Chris’s interaction with both groups later on.

“’Tisn’t right for them to be here at all, I tell you!”

This lets me indicate the villagers dislike the outlanders’ presence.

“Lord Virere may tax the food from our mouths, and that’s one thing. But forcing us to provide for outlanders who should not even be here?”

This establishes their discontent with the nobility. Chris and the readers already know this, but Allara still needed to hear it.

A man’s deep voice boomed above them all: “I’ll be no man’s jailer, I won’t.”

Now, it’s time to characterize one villager in particular. Chris doesn’t see him yet, just hears him. He’s a country shepherd, with a slight dialect, which I want to be subtly evident right away—“showing” why Chris recognizes his voice, rather than simply telling.

Chris flinched.

An action beat from Chris immediately indicates his discomfiting recognition of the voice.

The voice was Mike’s. Or, rather, Rordin Soller’s.

To catch readers up to speed with Chris’s realization, I simply tell them what he hears. Since Rordin was a minor character introduced way back in the First Act, I reiterate his full name and tie him back in to Mike, to help readers remember Chris’s encounter with him.

“I will not,” Rordin continued. “No matter what Virere says. Tax us how he may.”

One more line of dialogue lets me cement Rordin’s characterization in this scene, now that readers know who he is.

Chris’s gut tightened. At least, Allara was getting a show made to order.

An action beat indicates how Chris feels about this information. The brief internal narrative reminds readers this is new information to Allara.

She looked straight ahead, her face tight. “Quinnon.”

An action beat from Allara hints at her internal reaction without needing any explanation from Chris. She moves the plot through purposefully ambiguous dialogue.

With a nod, he moved the column forward at a canter.

Quinnon’s action beat does double duty by moving both himself and the entire main body of characters in response to Allara.

As they reached the rear of the quickstepping prisoners, two Yellow Guardsmen reined up to salute Quinnon. Then, recognizing Allara, they dismounted to bow.

Again, the setting is changing slightly, as Chris’s group moves forward to meet the new characters. This means the new characters need to be referenced in spatial relation to Chris’s group. Quick actions on the part of the new characters briefly characterize them, separate them from the larger group, and indicate they will be the new actors.

“Let’s see your commander,” Quinnon said.

Logic within the scene requires the queen speak only to the commanding officer—who would not be in the rear. Therefore, a quick exchange is necessary to bring the right character to the right place at the right time.

The senior Guardsman, a sergeant, looked Quinnon over with an almost insubordinate smirk on his scarred face. “Aye, Captain.” He vaulted into his saddle and galloped up the line of prisoners, which was being hurried toward the next curve around the hill.

Because this Guardsman will be an important character later in the chapter, he needed to be introduced more fully, with both a physical characteristic (“scarred face”) and a little bit of personality (“insubordinate smirk”). The second sentence indicates his necessary response to Quinnon’s command, as well as showing that the prisoners are moving out of the immediate scene.

4 Ways to Know How to Choose the Right Sentences

And… we could go on and on with the above commentary. Every sentence has its own unique role to play, depending on the needs of the scene. But hopefully, you can see from these examples how each sentence:

1. Bridges into the next sentence with cause and effect.

2. Does double and even triple duty, where possible, to indicate multiple aspects of the story.

3. Juggles the dissemination of information in the most linear way possible to smooth readers’ understanding and visualization of the scene.

4. Provides a balance of setting, dialogue, action, and internal reaction.