K.M. Weiland's Blog

October 13, 2025

Structuring Your Novel Workbook: Second Edition Launch + Freewrite Wordrunner Giveaway

When I first wrote Structuring Your Novel over a decade ago, I didn’t know it would become one of my most beloved books—helping almost 100,000 writers find clarity and confidence in their storytelling. Hearing from writers who finished their manuscripts or published their books because of it has been one of the greatest joys of my career.

Last year, I released a revised and expanded second edition of Structuring Your Novel to celebrate its 10-year anniversary. I added new chapters, refined explanations, and updated the material with everything I’ve learned in the past decade about story structure. But I knew that wasn’t quite enough.

The workbook that accompanied the first edition needed an upgrade too! Writers have been asking me for years to expand it and make it even more practical and comprehensive. So I rolled up my sleeves and did just that.

This new second edition of the Structuring Your Novel Workbook is filled with 80 brand-new exercises, updated terminology, and refined guidance that matches the new edition of the main book. My goal was to create a hands-on tool that doesn’t just explain structure but helps you apply it—step by step—to your own stories.

So today, I’m thrilled to share the Revised & Expanded Second Edition of the Structuring Your Novel Workbook—a hands-on guide to help you apply story structure directly to your own projects.

Celebrate the release of K.M. Weiland’s Structuring Your Novel Workbook, Revised & Expanded Second Edition. Packed with new exercises and prompts, this hands-on guide helps writers master story structure and craft powerful novels.

Where Can You Buy the Workbook?You can purchase the Structuring Your Novel Workbook (Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition) at the following links:Amazon USA e-book (affiliate link)Amazon USA paperback (affiliate link)Amazon UKAmazon CanadaAmazon AustraliaAmazon JapanKoboBarnes & NobleApple BooksEpub Direct From My SiteAnd check out the special edition!Special Edition Fillable PDF Version (which means you can fill it out directly on your computer!)If you have already read the first edition, I would totally appreciate it, if you’d consider leaving a review on the new one! Creating a new edition meant losing the over six hundred reviews the book collected over the past decade. I would totally appreciate it if you’d help me rebuild the review section!

More About the Structuring Your Novel Workbook (Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition)Make Story Structure Your Superpower!

If you’ve ever felt stuck halfway through your draft—or realized something’s off after typing “The End”—you’re not alone. Structure is the secret weapon behind every unforgettable story.

In her acclaimed writing guide Structuring Your Novel, award-winning author K.M. Weiland laid out the blueprint for powerful, cohesive storytelling. Now, with this newly expanded 10-year anniversary edition of the Structuring Your Novel Workbook, it’s time to put plot structure to use in your own stories.

Packed with hundreds of insightful questions and creativity-sparking exercises—including 80 brand-new prompts and an in-depth chapter on the Inciting Event—this workbook will help you:

Build a rock-solid plot structurePerfectly time your plot points for maximum impactTurn structural weaknesses into storytelling strengthsPinpoint and fix a sagging middle with a powerful “centerpiece” sceneForeshadow key events with subtlety and skillAnd much more!Whether you’re plotting a new project or revising a rough draft, this hands-on guide will give you the tools to craft compelling stories—every time.

Every great novel starts with a strong foundation. Lay yours today.

Giveaway: Celebrate With Me!

Enter to win a Freewrite WordRunner (or Freewrite Alpha) in celebration of the launch of K.M. Weiland’s Structuring Your Novel Workbook, Revised & Expanded Second Edition. Giveaway open now – don’t miss your chance!

To mark this release, I want to celebrate with all of you. As a thank-you, I’m running a special giveaway!

One lucky winner will receive the brand-new Freewrite WordRunner keyboard—a sleek, mechanical writer’s dream that tracks word counts and helps you sprint distraction-free. (Because the WordRunner is currently on pre-order and will be shipping early next year, the winner can also choose to receive the Freewrite Alpha instead—a fantastic distraction-free writing device.)

Description of the Freewrite WordRunner:

The Freewrite Wordrunner is a futuristic, writer-first mechanical keyboard crafted for focus and productivity. Built on a durable die-cast aluminum chassis, it features an innovative “Wordometer” (a real-world, electromechanical word counter), a customizable sprint timer with LED indicators, and a refined function row with keys like Undo, Find, Paragraph Up/Down, plus three macro keys labeled Zap, Pow, Bam. Its red joystick controls media playback and volume, and you can pair it with up to four devices, wired or via Bluetooth. It’s sleek, writer-centric, and instantly distraction-proof.

To EnterWinners will be announced Monday, October 20th (via email and on Instagram). Enter below! (Note: no purchase is necessary to enter.)

If you’ve ever struggled with sagging middles, confusing plot points, or stories that don’t quite land, this workbook is designed to guide you through step by step. I hope it will help you build stronger stories, faster drafts, and more satisfying writing journeys.

Every great novel starts with a strong foundation. Lay yours today!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What part of structuring your stories do you find most challenging—timing your plot points, building momentum through the middle, or tying everything together in the ending? Tell me in the comments!The post Structuring Your Novel Workbook: Second Edition Launch + Freewrite Wordrunner Giveaway appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 29, 2025

Single vs. Multiple Narrators: Pros and Cons for Novelists

Note from KMW: I’m taking a short break this week to hang out with my brand-new niece! While I’m off getting cuddles, here’s a quick post you can read in just a couple of minutes. No podcast today, just a bite-sized look at an important storytelling choice.

Note from KMW: I’m taking a short break this week to hang out with my brand-new niece! While I’m off getting cuddles, here’s a quick post you can read in just a couple of minutes. No podcast today, just a bite-sized look at an important storytelling choice.

One of the biggest questions novelists face is whether to use a single narrator or multiple narrators. Multiple POVs can broaden perspective and heighten tension, while a single POV offers intimacy and focus. Today, I’m breaking down the pros and cons of each approach and sharing my own surprising realization about the books I tend to love most.

And don’t forget! To help you dig even deeper into the building blocks of strong stories, you can now pre-order the e-book version of the revised and expanded second edition of the Structuring Your Novel Workbook on Amazon. (The paperback and a deluxe fillable PDF version will become available next week on the official launch day, October 6th—along with an epic giveaway. See you then!)

***

A lively debate among writers and readers often centers on the number of narrators in a novel. Should a story be told through a single narrator’s voice or unfold through the perspectives of multiple narrators? A few years ago, I hosted a discussion on Facebook and Twitter/X where most authors favored two or more narrators. Yet several readers argued their favorite books were those written from the perspective of just one character.

Today, let’s take a quick look at this question: what are the advantages and disadvantages of single-narrator vs. multiple-narrator novels?

The Benefits of Multiple NarratorsAt first glance, the benefits of multiple POV characters are obvious. Telling a story through several narrators allows us to give readers a broader perspective. Not only can we share first-hand accounts of different events, but we can also layer contrasting perspectives—such as when characters observe one another and offer commentary we wouldn’t get inside the head of any one character alone.

This approach can also increase tension and suspense, since readers often know more than the characters do. For example, one narrator may walk blindly into a trap that another narrator has already warned us about.

The Benefits of a Single Narrator

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

The advantages of a single POV novel aren’t always as obvious, but they’re powerful. A one-narrator structure tightens the plot focus, prevents unnecessary rambling, and reduces extraneous subplots. More importantly, it provides space to deeply develop the protagonist’s character arc.

A single narrator also creates intimacy. Readers are invited to experience the story through one lens, fostering a strong bond with the main character. That said, the limitations are real: single POV books can feel narrow, and readers may become frustrated if they’re locked out of crucial events happening offstage.

Which POV Is Right for Your Novel?Ultimately, neither approach is wrong. Writers must analyze the needs of their story structure to decide which technique best serves it. Before making a decision, reflect on your own reading experiences.

For example, although I’ve used multiple POVs in all my novels, I realized most of my favorite books rely on the precision and intimacy of a single narrator (which was one of the reasons I decided to go with a single POV in my most recent novel Wayfarer).

That insight may help you decide which POV strategy best supports your story’s goals.

In SummaryYour choice of POV, whether single or multiple, will completely change the way your story unfolds. By weighing the pros and cons of each narration style, you’ll be better equipped to craft a novel that delivers the exact reading experience you want.

Key Takeaways:Multiple narrators broaden perspective, layer tension, and offer contrasting viewpoints.Single narrators tighten focus, streamline the plot, and strengthen the protagonist’s development.The “right” choice depends on the story you’re telling and the experience you want your readers to have.Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you prefer reading (or writing) novels with a single narrator or multiple narrators? Why? Tell me in the comments!The post Single vs. Multiple Narrators: Pros and Cons for Novelists appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 22, 2025

Big vs. Small Character Arcs: Understanding the Degrees of Change in Storytelling

Not every story needs a protagonist who undergoes a sweeping, life-altering transformation. Many memorable tales hinge on smaller, quieter shifts in perspective—or even on characters who stay true to themselves from beginning to end. Writers often hear that character arcs must be dramatic to be meaningful, but the truth is arcs exist on a spectrum. Big character arcs can redefine a protagonist’s entire worldview, while small character arcs can reveal subtle but powerful growth that shapes the story in more understated ways. Understanding when to use a big arc, a small arc, or even a Flat Arc can help you choose the right level of change for your characters and keep readers invested from page one.

Not every story needs a protagonist who undergoes a sweeping, life-altering transformation. Many memorable tales hinge on smaller, quieter shifts in perspective—or even on characters who stay true to themselves from beginning to end. Writers often hear that character arcs must be dramatic to be meaningful, but the truth is arcs exist on a spectrum. Big character arcs can redefine a protagonist’s entire worldview, while small character arcs can reveal subtle but powerful growth that shapes the story in more understated ways. Understanding when to use a big arc, a small arc, or even a Flat Arc can help you choose the right level of change for your characters and keep readers invested from page one.

When I write about character arcs, I use sweeping terms about overcoming the Lie the Character Believes in pursuit of the thematic Truth. We talk about your character encountering Doorways of No Return, Moments of Truth, and Dark Nights of the Soul. All of these terms sound epic because they are symbolic. This means they can be applied in different stories to varying degrees of intensity. Just as in our own lives, some character arcs will rock the very foundations of the earth, while others may only offer a comparatively tiny realignment of perspective (perhaps as a building block toward one of those earth-shattering changes later on, but perhaps not too).

A while back, Tom Dell’Aringa emailed me with the following observation and query:

I’ve been following your stuff for a while. I was watching one of your videos on beginnings because I write a series, where the main character and his sidekick don’t change (like Jack Reacher or Jack Ryan, etc., although SF). While I always try to have some issue the main character is working through, he can’t go through some amazing transformation each book. Part of the joy of a series is sticking with a character you like, with all their pros/cons…. I wonder if you had thoughts on how to approach a series while living into the structure you have set out….

First of all, it’s important to recognize not every story will feature a Change Arc. Particularly in series, many characters demonstrate Flat Arc characteristics in each episode. This allows the story’s primary structures to remain unchanging, which allows steadfast characters to represent the story’s Truth to other characters—and therefore to be the one who prompts change rather than the one who changes. (If you’d like a hands-on tool for identifying and planning these different types of arcs, take a look at my Character Arc Worksheets.)

Character Arc Quick Guide (Bundle of 5 Worksheets)

It’s also possible to write stories that really don’t present much of an arc at all, although this is trickier since if the characters do not change, then it is difficult to create any true sense of movement or meaning within the plot itself. Most of the time, if you really look for it, even in tricky stories, you can still identify the underlying symbolic landmarks of some kind of arc, either in the protagonist or the supporting characters.

With all of that in mind, it’s important to remember you can feature a Change Arc without it necessarily having to offer tremendous transformation. When we speak of a Change Arc (whether Positive or Negative), we are simply referring to the fact that the character changes perspective in some way. Sometimes this can be a life-changing paradigm shift, but sometimes the change can be quite small (although it must still be consequential to the story). Particularly in plot-forward stories, the thematic Truth a character learns might even be something practical about the plot mechanics (e.g,. whodunit) rather than a deep personal or social insight. (For my money, however, stories are easily upleveled when the two go hand in hand.)

In short, character arcs in different stories won’t all look alike or carry the same weight. From here, we’ll break down the difference between big arcs, small arcs, and Flat Arcs, and explore how you can choose the right degree of change to best serve your story.

In This Article:Big Character Arcs and How Transformation Redefines the ProtagonistSmall Character Arcs and How Quiet Shifts Can Still Grip AudiencesFlat Arcs and How Characters Stay True While Still Driving the PlotBig Character Arcs and How Transformation Redefines the ProtagonistWhen we think of “thematic” stories, they are usually ones in which the character arcs are so big they completely redefine the characters’ worldviews and perhaps even the world itself. Like all character arcs, these changes are founded upon the central polarity between a Lie the Character Believes and the opposing Truth. At its simplest, this Lie is a limited perspective, while the Truth acts as a corrective by providing at least a slightly more expanded and functional advancement on that perspective.

In big Change Arcs, this conflict between Lie and Truth tends to be dramatic. This raises the stakes because the transition into the new perspective will all but demolish the character’s previous perspective. This inevitably involves a personal ego death and a transformation of personal identity (i.e., how characters view themselves). Likely, it will also play out in dramatic fashion in the external plot. Characters will have much to gain or much to lose depending on which perspective they end up embracing.

For Example:

A clear example of a dramatic Positive Change Arc can be seen in Schindler’s List. At the beginning, Oskar Schindler believes the Lie that his worth and power come from wealth, status, and self-interest. His identity is bound up in being a profiteer who exploits the war for personal gain. Over the course of the story, he is confronted with the Truth that real value lies in human life and moral responsibility.

Embracing this Truth demolishes his former worldview and forces him through a profound ego death, reshaping how he sees himself and his place in the world. Importantly, this transformation is not just personally dramatic: it also plays out against the larger system of Nazi Germany, where Schindler’s new Truth is in direct conflict with a regime fighting to assert its own destructive “truth” as socially preeminent. His decision to resist this system is not only perilous to him personally, it also highlights how a big Change Arc reverberates outward. The character’s internal shift becomes a force of external opposition in a dangerous world, raising both personal and thematic stakes to their highest pitch.

Oskar Schindler’s transformation in Schindler’s List is a powerful example of a big character arc. (Schindler’s List (1993), Universal Pictures.)

These dramatic personal and social stakes are true whether the character ends up in a Positive Arc from Lie to Truth or in a Negative Arc from Truth to Lie.

For Example:

The Banshees of Inisherin shows a powerful example of how a Negative Change Arc demolishes identity and spirals outward into destruction. At the start, both Pádraic and Colm have perspectives that, while limited, still allow for human connection: Pádraic clings to the Lie that being “nice” and “happy” will guarantee him love and belonging, while Colm seeks significance by isolating himself to pursue art, believing the Lie that human relationships are expendable in the quest for legacy.

As the story progresses, each man is drawn deeper into his respective Lie. Pádraic’s desperation to hold on to friendship corrodes his innocence, while Colm’s rejection of the relationship becomes increasingly violent and self-mutilating. These internal disintegrations don’t remain private. Just as in big Positive Arcs, in which the Truth collides with the larger world, here the embrace of the Lie clashes with the community, escalating conflict and despair. By the end, both characters have been transformed by the loss of whatever humanity and hope they once held. Their Negative Arcs show how a shift from Truth to Lie can unravel not only personal identity but also the fragile social bonds of an entire world.

In The Banshees of Inisherin, Colm and Pádraic’s relationship shows how Negative Change Arcs can unravel both identity and community. The (Banshees of Inisherin (2022), Searchlight Pictures.)

Small Character Arcs and How Quiet Shifts Can Still Grip AudiencesMany stories feature smaller character arcs with lower stakes. In these stories, the Lie/Truth will be less obviously mind-bending and ego-threatening. The thematic premise might span the gamut from “learning a moral lesson” (e.g., “be more loving”) to simply “seeing something in a new light” (e.g., “maybe my life is more interesting than I thought”) to even just “learning a practical lesson” (e.g., “mad scientists shouldn’t play god” or “the dangerous monster can be defeated if we work together” or even “karate makes me powerful”).

In smaller arcs, characters will not necessarily need to experience a dramatic ego death or shift in personal paradigm or identity. They may end the story simply feeling slightly more whole or affirmed. Bigger arcs tend to speak more obviously to our deeper psyches and to the audience’s own inner experience of symbolic life. This is because their scope allows them to draw down bigger and more powerful symbolism, since they often deal with high-stakes situations that are relatively rare in day-to-day life, allowing them to offer important cathartic experiences.

Meanwhile, smaller arcs can be extremely satisfying for audiences in their ability to recreate the sort of relatable situations we all regularly encounter and work through. Major ego deaths are threshold experiences that only happen a few times throughout our lives; smaller perspective shifts, however, happen on a daily basis. The best small arcs are those that intentionally lean into the verisimilitude and reliability of daily evolution.

For Example:

The show Gilmore Girls thrives on micro arcs that bring satisfying movement to each episode without fundamentally altering the characters. Mother and daughter protagonists Lorelai and Rory are defined by strong personalities and consistent worldviews, and the series’ charm lies in watching those traits play out in different circumstances. Most episodes introduce a conflict rooted in family dynamics, town politics, or personal relationships, such as Lorelai needing to smooth things over with her parents or Rory stumbling in balancing academics with friendships. By the end of the episode, the tension is usually resolved with a small shift in outlook: someone apologizes, admits fault, or simply sees a situation from a slightly different angle.

These micro arcs don’t reinvent the characters. Lorelai doesn’t stop being witty and independent, Rory doesn’t stop being studious, their mother/grandmother Emily doesn’t stop being controlling. But the little tweaks in understanding provide the story’s sense of movement while keeping the characters familiar and dependable, which is exactly what makes viewers want to return to the town of Stars Hollow week after week.

In Gilmore Girls, Lorelai and Rory show how small character arcs—tiny shifts in perspective or relationships—can carry a story’s emotional heart. (Gilmore Girls (2000-2007), The CW.)

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Often, however, small arcs are less advantageous in bigger stories. In neglecting to pair meaty character arcs with the high stakes of plot-driven spectacles, stories often gut their very soul—theme. Theme arises directly from the interplay of external events challenging characters to change—not just on an external, practical level, but on a deep, personal level. When episodic high-tension stories fail to match their plot events with commensurate character evolution, they are not only missing out on their best potential, but also presenting an ultimately dissatisfyingly out-of-sync presentation of reality. They often ring hollow and become all-too-forgettable for the simple reason that their bluff and bluster isn’t allowed to mean anything.

For Example:

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom heightened its spectacle even further than its predecessors, escalating the stakes to include not just an island of dinosaurs but the potential weaponization and global spread of these creatures. Yet despite the apocalyptic implications, the characters’ arcs remain small and underdeveloped. Claire softens slightly from her corporate-minded pragmatism into a more openly compassionate activist, but this shift is incremental compared to the world-shattering events around her. Owen, meanwhile, remains essentially unchanged—an action hero stereotype who doesn’t evolve in any significant way.

The mismatch between the immense external conflict and the modest internal growth means the film struggles to generate any thematic depth whatsoever. Its bluff and bluster never quite land because the story neglects the deeper resonance that comes when characters’ internal journeys rise to meet extraordinary stakes.

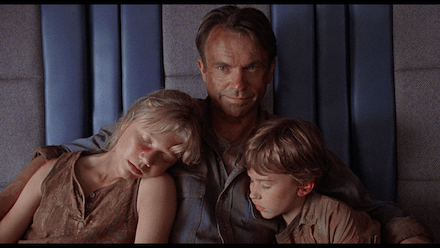

By contrast, the original Jurassic Park paired its high-stakes dinosaur spectacle with a heartfelt internal arc: Alan Grant’s begrudging discomfort with children gradually transforms into protectiveness and affection as the high stakes demand he bond with the two children in his care, giving the story an emotional anchor that elevates its thrills into resonance.

Alan Grant’s quiet transformation in Jurassic Park shows how small arcs can give big stories their emotional heart. (Jurassic Park (1993), Universal Pictures.)

Flat Arcs and How Characters Stay True While Driving the StoryA final consideration for your story is the Flat Arc. The Flat Arc represents, basically, the next level a character may reach after a Change Arc. The Flat Arc is a story about a character who already “gets” the Truth. However, because stories still require the engine of internal change in order to generate meaning, these stories will still feature characters who change. The difference is that here, the Flat Arc protagonist acts as an Impact Character who represents the thematic Truth and inspires Change Arcs in the supporting characters—whether those arcs are large or small.

So much can be done with a Flat Arc character. Not only can they be used to create a stable axis for an ongoing series, in which potentially everything changes except the protagonist—they can also develop tremendous complexities in their own right. The most important thing to remember about Flat Arc characters is that just because they’ve figured out the thematic Truth at the center of the story, this doesn’t mean they understand all truths—or even any other truth. In short, they can be wonderfully limited and flawed characters while still acting as catalysts for the changes that need to happen in the external story world.

For Example:

Sherlock Holmes remains firmly grounded in the series’ central Truth that rational observation and logic can uncover reality. He doesn’t need to undergo a sweeping personal transformation from story to story; instead, he acts as the stable axis around which the mystery turns. This doesn’t mean Holmes is perfect or even well-balanced. His arrogance, addiction, and emotional blind spots remind us that a Flat Arc character can be deeply limited.

What makes him fascinating is precisely this tension: he embodies the thematic Truth that reason exposes deception, but he does not grasp (or refuses to engage with) many other truths, such as those of empathy, humility, or human connection. His steadfastness allows him to be a catalyst for the story’s external resolution, while his flaws keep him vivid and complex, preventing him from collapsing into a lifeless stereotype.

Sherlock Holmes demonstrates a Flat Arc: he already embodies the thematic Truth of reason and logic, shaping the story world without undergoing major change himself. (Sherlock Holmes (2009), Warner Bros.)

This makes Flat Arc characters excellent choices for many types of series, especially episodic series, in which the central premise remains the same (e.g., a detective solving a mystery) while the plot details change (e.g., new murderer and new suspects in each installment). Flat Arc characters tend to be particularly archetypal. In their unchangingness, they represent a single symbolic catalyst. While this can create striking depth, it can also become stereotypical and, yes, flat very quickly.

Used with discretion and awareness, Flat Arc characters stand as extremely powerful and inspirational (or cautionary) figures. Fundamentally, they represent characters who are a step ahead on the path. They are characters who have emerged from the comparative ignorance of a previous Positive Change Arc (even if it is never referenced) in order to embody a particular Truth (i.e., a slightly more expanded perspective than that of the surrounding story world). Their seeming simplicity can actually make them quite tricky to write well, but when executed skillfully, they provide all kinds of versatility for the author.

For Example:

Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird is a quintessential example of a Flat Arc character used with tremendous discretion and power. He has already moved beyond the ignorance of believing society’s Lie—that prejudice and inequality are acceptable—and now lives firmly in the Truth of justice, empathy, and human dignity. Because he stands a step ahead of the rest of Maycomb, his role is not to transform internally but to act as a moral catalyst, challenging the community and inspiring his daughter Scout.

His apparent simplicity (i.e., he is calm, principled, unwavering) makes him seem almost mythological, which is precisely what gives him his symbolic force. He embodies a Truth others must grapple with, and the drama arises from how his world reacts to his steadfastness rather than from any change within him. Written well, such Flat Arc characters can serve as luminous figures, offering readers a vision of what it looks like to live by a deeper Truth even when it comes at great personal cost.

Atticus Finch shows how Flat Arc characters embody moral truth and inspire growth in others without needing to transform themselves. (To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Universal Pictures.)

Whether you’re writing a sweeping epic or a cozy slice-of-life, remember: the heartbeat of your story lives in the character arcs. Big arcs grip us because they reflect the rare, seismic changes of real life, while small arcs and Flat Arcs resonate because they reflect the daily steps of growth, resistance, and steadfastness we all experience day to day. When writers understand the spectrum of arcs available to them, they gain the power to craft stories that feel meaningful and true while also choosing the approach that makes the most sense for any particular story.

In SummaryCharacter arcs exist on a spectrum—from dramatic transformations that shatter identity to small but satisfying shifts in perspective,to Flat Arcs that anchor the story’s thematic Truth. Each option brings different opportunities and challenges, and the best choice depends on the kind of story you’re telling.

Key TakeawaysBig Arcs: Redefine a character’s worldview through dramatic conflict between Lie and Truth.Small Arcs: Mirror everyday perspective shifts that create relatability and subtle growth.Flat Arcs: Provide a stable axis through embodied experience that inspires change in others.Balance matters: The scale of the arc should align with the scale of the story’s stakes to create resonance and theme.Want More?Need a fast, reliable roadmap for mapping out your characters’ journeys?

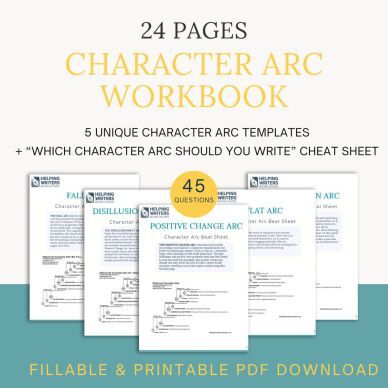

Check out my Character Arc Quick Guide Pack, featuring five fillable worksheets that break down the essential beats of every major arc type (Positive, Flat, Disillusionment, Fall, and Corruption). Whether you’re outlining a brand-new protagonist, testing alternate possibilities for a supporting cast, or just looking for a quick-reference checklist during revisions, I designed these worksheets to give you a streamlined way to develop arcs that work. Instantly downloadable, printable, and reusable, they’re designed to save you time while making sure your characters’ inner journeys stay just as compelling as your plot twists.  Grab the Character Arc Quick Guide Worksheets here.

Grab the Character Arc Quick Guide Worksheets here.

Plan your story with the Character Arc Workbook Quick Guide—5 templates, 45 questions, and a cheat sheet to help you choose the right arc.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What kind of character arcs do you most enjoy writing—or reading? Do you prefer the catharsis of big transformations, the relatability of small shifts, or the steadfast power of Flat Arcs? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Big vs. Small Character Arcs: Understanding the Degrees of Change in Storytelling appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 15, 2025

How a Character’s Personality Shapes Arc, Voice, and Goals

When it comes to creating memorable, emotionally resonant characters, your character’s personality may seem like it’s just a “flavor,” but in many ways it’s actually the foundation of the story itself. Your character’s personality influences everything: the character arc, the voice in both dialogue and the narrative (if the character has a POV), and the goals that shape your entire plot.

When it comes to creating memorable, emotionally resonant characters, your character’s personality may seem like it’s just a “flavor,” but in many ways it’s actually the foundation of the story itself. Your character’s personality influences everything: the character arc, the voice in both dialogue and the narrative (if the character has a POV), and the goals that shape your entire plot.

In many ways, your characters’ personalities can determine whether or not the story works. This is most obviously true when it comes that special “it” factor that creates unforgettably quirky or nuanced characters, but it’s even more true when it comes to the cohesion of your story’s deeper workings—where character, plot, and theme all come together.

In short, understanding personality might just be one of the most powerful tools in a writer’s toolbox.

In This Article:3 Reasons Why Personality Is the Secret Ingredient to Strong Characters4 Ways a Character’s Personality Drives Your Storytelling10 Practical Tips for Weaving Personality Into Character Arc, Plot, Dialogue, and MoreFAQs About Character Personality3 Reasons Why Personality Is the Secret Ingredient to Strong CharactersThe concept of personality brings a number of different connotations.

1. Personality Is a Consistent Set of TraitsFor starters, we recognize the technical definition of personality as a consistent set of traits, behaviors, emotional patterns, and motivations that shape how someone perceives the world, makes decisions, and interacts with others. Personality influences not just what people do, but why they do it, how they react under pressure, form relationships, pursue goals, and confront internal or external conflict.

2. Personality Is CharismaThere is also a certain sense of je ne sais quoi—that special sauce that makes an individual unique and interesting. When the word “personality” is brought up in a fictional context, we generally tend to think of characters with big, interesting (read: complex), and memorable personalities. They’re not beige; they’re intriguing in their relatability but also because of their unique ways of viewing and responding to the world.

3. Personality Is the Ego or False SelfHowever, personality can also be understood as the “false” or “egoic self”—a persona honed throughout our lives to allow us to move functionally through society and relationships, but which is ultimately limiting to the bigness of our true selves.

Writers can make good use of all three of these definitions. Thinking intentionally about a character’s personality allows us to craft a container in which we can sift through potential traits, reactions, and goals to find those that offer the most cohesion for the entire story. From there, we can explore ways to create characters with inherently entertaining or intriguing personalities—ones with the potential to join iconic classics such as Michael Corleone, Jo March, Tony Stark, Sarah Connor, Gandalf the Gray, and Hermione Granger (their names are as famous, if not more, than the stories they play in).

4 Ways Personality Drives Storytelling

4 Ways Personality Drives StorytellingMost of the time, when writers consider a character’s personality, they focus primarily on outward traits. However, in so many ways, a character’s personality is the story. Here are four key considerations.

1. Personality Shapes the Character Arc

Although some personality systems offer static descriptions of traits, others like the Enneagram go deeper to point out specific transformational paths that can help people break past the ego-based facades and personas that limit us and create dysfunction. From this perspective, personality is all about the character arc!

Although most personality systems worth their salt (including MBTI, Human Design, Socionics, love languages, attachment styles, even astrology, and more) ultimately offer pathways of growth, the Enneagram is somewhat unique in its focus on specific paths of evolution (or devolution as the case may be) for each type. As I’ve explored before, this makes the Enneagram perhaps the most useful personality system for not just identifying and fleshing out a character’s personality, but for using that personality to create a cohesive character arc and, from that, plot and theme as well.

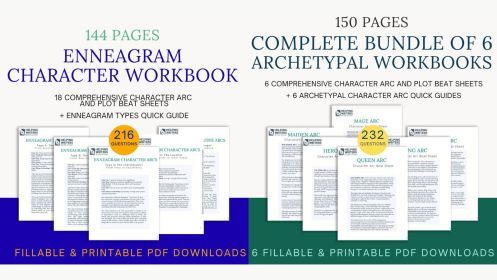

If you’d like more guidance, I’ve talked here about the Positive Change Arcs inherent in each of the nine Enneagram types and here about the Negative Change Arcs inherent in each type. I’ve also just released a full set of worksheets for each of the nine types. Each bundle includes questions to guide you in planning either a Positive or Negative Arc for each of the types, which will help you ensure your character’s arc, Lie vs. Truth, and Want vs. Need are aligned with the character’s personality, while also helping you brainstorm ways to make your character’s personalized arc consistent with the overall plot and theme.

Enneagram Character Arc Cheat Sheet Bundle – Square for Etsy

2. Personality Informs Voice and DialoguePerhaps nothing in your story is more obviously influenced by personality than character voice. When we think of personality on the page, we think about voice more than anything else. How a character communicates—whether in dialogue or directly through the narrative in a tight POV—directly communicates personality. In my own experience, I’ve found that if my narrative is struggling, it’s often because I’m trying to write in the POV of a character whose voice just doesn’t have enough personality.

Personality will also directly influence your character’s dialogue style. This isn’t just about word choice. It’s also about the character’s preferred “style” of arguing or engaging in conflict. For example, a more aggressive personality type like an Enneagram 8 or an MBTI ENTJ will have an entirely different style of attack and defense (aka, initiating desires or responding to others’ desires) than will an Enneagram 9 or a Human Design Reflector.

Writing is all about the words, and nothing influences word choice, tone, emotional reactions, dialogue style, conflict resolution, or argument styles more than personality.

(You can find questions to help you uncover all of this is another of my hot-off-the-presses worksheets—the Character Interview, featuring 113 questions, many of them about personality.)

Character Interview Digital Worksheet for Writers

3. Personality Determines Shadow and Subconscious Goals“Personality” literally refers to what we see on the surface, and yet personality is formed by what is unseen—by what has been banished to the “shadow” or the unconscious. What we see in a personality is really just what’s left after certain traits, energies, beliefs, and identities have been deemed dysfunctional (usually unconsciously early in childhood) and “cut off” from the conscious personality.

This is important for storytellers because uncovering your character’s shadow will likely be an intrinsic part of the character arc. Character arc, at its simplest, is about expanding a limited perspective. Ultimately, this perspective is always about one’s self. Even if it seems to be a change in perspective regarding others or the world at large, ultimately this new “Truth” reflects upon the self’s place in relationship to others. This means the “limited perspective” (or Lie the Character Believes) is a product of the necessarily always limited personality, while the “expanded perspective” (or thematic Truth) is, at least in part, a restoration of some piece of the self previously lost to the shadow.

From here, we can see how character goals are almost always driven by this deeper subconscious motivation. A character’s personality isn’t just traits. More deeply, personality is what the character fears, represses, and unconsciously chases. Right there, you already have an entire story!

4. Personality Reveals Core Strengths and WeaknessesOnce we recognize personality as not just someone’s (presumably functional) persona, we can see the deeper truth that personality is, in fact, as much about inherent weaknesses as inherent strengths. Understanding this about your character’s personality gives you a fast track to the central internal conflict.

Stories run on the tension points between polarities—between strengths and weaknesses, between Lies and Truths, between delusions and epiphanies, between cowardice and courage, between mistakes and successes. All of these are inherent to your character’s personality. What is a stressful internal dissonance for one personality (e.g., balancing an Enneagram Five’s need for connection against the fear of overwhelm) is already a natural integration for another type (such as a Two, who struggles with different tension points).

A firm understanding of a useful personality type system can help you double-check your character’s development arcs for consistency and realism. When you’re in the early throes of writing, it can be easy to scribble things onto the page that, in the big view, don’t actually create the necessary and realistic tension points that arise from a consistent portrayal of human nature. An understanding of personality can guide you to which arcs are most natural to your characters.

10 Practical Tips for Weaving Personality Into Plot, Dialogue, and ArcAll right, enough theory! Let’s get practical. How can you use personality more intentionally to develop not just a better character, but a more cohesive and resonant plot and theme as well?

Let Personality Shape the Story1. Choose a Personality Framework Early in Your Planning Process— Use a system like the Enneagram or MBTI to explore internal motivations and potential arcs.

— I recommend focusing on one primary personality system to avoid overcomplication.

— Once you know your character’s personality, examine the system as a guide to help you find the most resonant growth path.

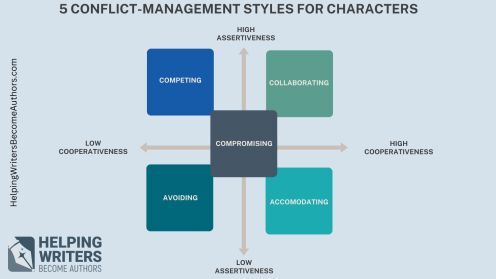

2. Use Personality to Predict Conflict Style— Start working on your plot by considering what conflict style (e.g., competing, avoiding, collaborating, etc.) best fits your character’s personality.

— Think about how your character argues, avoids, or escalates conflict based on type.

— This adds nuance to both dialogue and plot tension, while showing you what types of scenes are most likely to emerge when your character’s goals are met with obstacles (i.e., conflict).

— Your character’s conflict style is one of the richest places to mine for entertainment opportunities.

— For example, consider Han Solo’s classically sarcastic but often off-point retorts: “We’re all fine here now… how are you?”

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

–Ask: How can your character’s conflict style create dynamic, unusual, or larger-than-life scenes?

3. Let the Shadow Reveal the Theme

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

— Use the subconscious fear or flaw inherent in your character’s personality to point toward the story’s deeper thematic question.

— For example, a character with an avoidant attachment style might prompt thematic explorations of self-isolation or self-sabolage, such as Elsa in Frozen.

Frozen (2013), Walt Disney Pictures.

— If you’re unsure what might be in your character’s personality shadow, remember shadow theory’s simple guideline: “Whatever is visible in a person’s external personality is an indication that the exact opposite resides in the shadow.”

— For example, an MBTI INTP character—who relies most heavily on mental functions—may resonantly create a story about exploring the underworld of grief or the bewilderment of falling in love, such as R in Warm Bodies.

Warm Bodies (2013), Lionsgate.

4. Design Key Plot Beats Around Transformation Points

Personality Types by Don Richard Riso and Russ Hudson (affiliate link)

— Personality systems like the Enneagram particularly lend themselves to narrative arcs, since they suggest specific steps on a path to growth (in addition to my worksheets, you can check out Personality Types by Russ Hudson and Don Richard Riso for in-depth studies on this).

— For example, if you know your Enneagram Type Three character’s Lie is “I’m only worthy if I succeed,” you can shape the Midpoint or Third Plot Point to directly challenge that belief.

Let Story Reveal Personality5. Reverse-Engineer Personality From Your Plot— If your story idea came to you as a plot instead of a character, you can use what you know about the story’s external events to create the most resonant personality for your character.

— Ask: Based on the choices the plot indicates the character will need to make, what traits or fears will be likely to emerge in the character arc?

— From there, you can identify the most resonant personality type. +However, be sure to use the story events to discover (not dictate) who the character is.

— Character and plot should influence each other, but character should be the more dynamic force. This is to ensure that the plot feels organic and natural rather than contrived.

6. Analyze Plot Points to Discover Your Character’s Internal Values— Take a look at what your character sacrifices or clings to when the stakes are high. That alone can reveal your character’s personality type or predominant internal struggle.

— For example, as an Enneagram One, Jane Eyre always returns to the central question of right and wrong (as she sees it). When confronted by Rochester’s pre-existing marriage at the Third Plot Point, she decides to leave him less because she feels betrayed and more because she believes it would be morally wrong for her to illegally marry him.

Jane Eyre (2006), WGBH/BBC.

7. Refine Your Character’s Type After Writing the First Draft— Sometimes, you won’t really know who your character is until after you’ve written the story.

— After finishing the first draft, you can go back to revise voice and dialogue to more clearly reflect a unified personality for your character.

Bonus Implementation Tips8. Create a Quick-Reference “Personality Snapshot”— Character personality—like most things in storytelling—can get complicated fast. Not only can relying on a personality system provide shortcuts to identifying and remembering character traits, but so can keeping a sort of “personality outline.”

— You can include your character’s personality type, dominant traits, shadow fear, core desire, communication style, and more.

— When writing, I always try to review at least a small portion of my notes every day before I begin to keep them fresh in my mind.

9. Use a Worksheet or Interview to Stress-Test Alignment— Although beat sheets and character interviews should only be used to create a flexible guide, they can be helpful for nailing down the big picture of your character’s personality and arc.

— You can find the free version of my character interview here, and you can grab the updated fillable pdf of the worksheet here.

Character Interview Digital Worksheet for Writers

— If you’ve chosen to use the Enneagram as your primary personality typing system, you may also find some help in my brand new Enneagram Character Arc Cheat Sheets to check whether the story beats align with the character’s internal journey. (Each bundle contains both Positive and Negative Change Arcs for each type.)

Enneagram Character Arc Cheat Sheet Full Bundle

10. Treat Personality as Dynamic, Not Fixed— I’m a big fan of the aphorism (usually attributed to George Box),

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

— This is true of so much in storytelling, and it is certainly true when it comes to personality systems.

— Although incredibly useful in helping writers distil the eminently complex topic that is the human personality, systems such as the Enneagram, MBTI, and more, are ultimately still limited and should only be used insofar as they are useful.

— Growth (or regression) in your character’s arc should always reflect believable changes in personality expression, and you should always listen to your own deep and instinctive understanding of the human ego, shadow, and persona above and beyond any fixed model.

Why Knowing Personality Unlocks Your Whole StoryYour character’s personalities aren’t just one layer of who they are. Personality is the central lens through which characters interpret the world, make decisions, and pursue goals. Personality is also the bridge between plot, theme, and character. Or perhaps we might think of it as the container that holds all three.

Personality shapes not only what your characters want, but why they want it, what’s standing in their way, and how they express that tension through action, voice, and internal conflict. That’s everything you need for your plot right there. When you understand your character’s personality, you gain access to the deeper psychological and thematic forces driving your story forward.

It’s important to remember there is no one “right” framework to use. Whether you gravitate toward the Enneagram, MBTI, Human Design, or something else, the most important step is simply choosing a system that resonates with you and then using it to stress-test your characters and their arcs.

FAQs About Character PersonalityWhat is the best personality system for writers to use?There’s no single best system, since each offers a different perspective. For instance, the Enneagram is ideal for exploring inner conflict and transformation, while MBTI is great for understanding cognitive wiring and behavior. The only thing that matters is choosing one that complements your writing style.

Can a character’s personality change throughout the story?Characters won’t change to a different personality, but how they relate from within the containers of their current personalities can dramatically evolve. A well-crafted character arc doesn’t usually change the core personality, but does change how the character expresses it. For example, withdrawn characters might learn to stay connected under pressure, without losing their introspective natures.

How does the Enneagram help with writing character arcs?The Enneagram maps core fears, desires, and defense mechanisms—all of which tie neatly into a character’s Lie, Want, Need, and Truth. Each Enneagram type also suggests likely growth paths and shadow pitfalls, which makes the system especially useful for writers when building Positive and Negative Change Arcs.

How do I figure out my character’s personality type?You can start by asking what your characters fear most, how they handle conflict, and what motivates their choices. Consider how they act under stress and in growth. Then compare those traits to personality types in your chosen system and adjust based on what best supports the arc you want to tell.

Want More?If you’re ready to dive deeper into using personality to guide your character arcs, check out my Enneagram Character Arc Cheat Sheets. Each worksheet bundle walks you through both Positive and Negative Change Arcs for all nine Enneagram types to help you align your character’s internal journey with your story’s external plot beats. You can use these digital worksheets when you’re outlining or revising to create arcs that are psychologically authentic and thematically resonant. Available now in my Etsy shop or via the Store tab above!

Enneagram Character Arc Worksheets

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What role does personality play in how you approach your characters? Do you start with a personality type, or does it emerge from the story? Do you use a system like the Enneagram or MBTI in your process? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How a Character’s Personality Shapes Arc, Voice, and Goals appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 8, 2025

Why All Stories Are Myth—and How They Transform Us

Stories are more than just entertainment. They’re also more than just reflections of real life. This is because, at its core, narrative is myth. Whether you’re crafting epic fantasy, gritty crime drama, or cozy rom-coms, deep archetypal patterns always echo through your characters, plots, and themes. Story is the theater of the psyche. It is a dream we collectively dream, in which each character and conflict embodies a part of ourselves. When we recognize this hidden foundation, we can tap this archetypal power to access the kind of storytelling that not only captivates readers but also transforms both their inner lives and our own.

Stories are more than just entertainment. They’re also more than just reflections of real life. This is because, at its core, narrative is myth. Whether you’re crafting epic fantasy, gritty crime drama, or cozy rom-coms, deep archetypal patterns always echo through your characters, plots, and themes. Story is the theater of the psyche. It is a dream we collectively dream, in which each character and conflict embodies a part of ourselves. When we recognize this hidden foundation, we can tap this archetypal power to access the kind of storytelling that not only captivates readers but also transforms both their inner lives and our own.

A few weeks ago, I shared a post that struck a chord with many of you—about my deep desire to witness the return of “soulful storytelling.” Specifically, I wrote about my personal dissatisfaction and even boredom with contemporary filmmaking. In that post, I talked about wanting to return to stories of subtextual depth, emotional earnestness, and goodheartedness (among other qualities). In pondering on this further via the many thoughtful exchanges I got to have with all of you in the comments section on that post, I realized there are more layers to the shifts we have seen in modern storytelling—and the next shift I believe we will soon see.

One of those layers is the tension we often feel, but perhaps do not always recognize, between hyper-realism in fiction and storytelling’s inherently mythic foundation. I’m talking about the differences between stories that dutifully mimic or even exaggerate the causality of everyday life and those that draw upon the timeless archetypal patterns of the psyche.

When asked to define “story,” we may reach for the convenient answer that story is a replication of real life. But this, I will posit, is not actually true. Throughout history, we have increasingly dressed our stories in the verisimilitude of realistic details and the self-consciousness of our minds’ inner workings. But underneath all the hyper-realism, the true and archetypal shape of story itself remains something quite mythic. It is much less a product of our conscious minds—our conscious and scientific understanding of the world’s workings and our place in it—and much more a product of our unconscious minds—our symbolic and dreaming selves.

Recognizing storytelling (no matter the genre) as inherently mythic allows us, as storytellers, to walk onto a much bigger stage. We exit the relatively small stage of the self we know—the conscious self—and enter the vastness of the self that lives beyond consciousness and therefore beyond the restricted understanding allowed by the ego.

When we approach story as something inherently mythic—an archetype that exists outside and beyond humanity’s “creation” of it as an artform—we regain the capacity to create stories that touch the deepest parts of ourselves to create not just transformation, but initiation.

In This Article:Story as a Primordial Force: The Mythic Foundation of NarrativeThe Theater of the Psyche: Every Character Is YouArchetypes as Living Forces in StorytellingStory as a Living Dream: Why All Stories Are MythStory as a Primordial Force: The Mythic Foundation of NarrativeFrom the far depths of human memory, story comes to us as a primordial force. Indeed, human memory itself is a story. Before we packaged stories for $20 mass consumption—before movies, before novels—story came to us as oral myths, ritual dramas, stone etchings, and catalysts of initiation.

Nowadays, storytelling is a highly specialized skill set. We come to sites like this one to study beat sheets and timing. We divide stories into highly specialized genres and check tropes off a list. We come to story as if it is something we can master. But in approaching story like this, we risk missing not just the deeper initiation story wants to offer each of us. We also risk missing out on the best possible stories we could be sharing with our own audiences.

I want to talk about one trend in particular that I see in modern storytelling. In itself, this trend is not problematic. But when too much emphasis is placed on it, it can create a polarized experience of story that can weaken its deeper impact. This trend, as I hinted previously, is hyper-realism. It is the trend—all but ubiquitous now—of faithfully recreating modern life on the page or the screen. In some ways, we might say it is “showing” rather than “telling.”

Again, I’m not saying this approach is wrong. I love detailed fiction that shows me the story world with such dimensionality that I’m there. I love deep POVs that faithfully mine and recreate the complexities of human interiority—everything from memory to motive.

But my feeling is that when this hyper-realism is not founded upon the deeper mythology of story itself, we often risk losing the forest for the trees. I will even go so far as to say this approach is a driving force behind the type of modern storytelling that carries characters and audiences to destinations awash with sophisticated despair or, at best, ambiguous apathy.

This is not to say mythic stories do not confront their fair portion of darkness and despair. But as I continue to study story as an archetype, it is my belief that these old stories (everything from the creation stories to The Odyssey to old folk tales like Little Red Riding Hood) speak to us, first and always, in metaphor and symbol. Certainly, as we explore the continuity with which the shape of story comes to us over the eons, I believe we can see that story itself is much more than simply a mirror of life. It is an initiatory force.

Becoming Supernatural by Dr. Joe Dispenza (affiliate link)

At the end of his book Becoming Supernatural, Dr. Joe Dispenza defined initiation:

I believe we are on the verge of a great evolutionary jump. Another way to say it is that we are going through an initiation. After all, isn’t an initiation a rite of passage from one level of consciousness to another, and isn’t it designed to challenge the fabric of who we are so we can grow to a greater potential?

Story is a symbolic map of transformation. It is a blueprint for growth and change. I wrote in the previous post about how I will never be satisfied with even one single story that does not challenge me in some way—because, for me, that is what I look for in a story experience. I look for that frisson of electricity, that tinge of awe, as I sense however faintly that I am entering an uncanny space—a wyrd space.

In the old Norse, the concept of “wyrd”—from which we get our word “weird”—indicated not just the uncanny, but the fated. In story, what I seek for myself are fated encounters. I seek shatterpoints of destiny that fracture, however slightly, reality as I know it.

The Theater of the Psyche: Every Character Is YouEvery story holds the seed of this transformational power. It doesn’t matter the medium or the genre. This potential is latent in all stories—whether about hellbent mobsters or romantic HEAs or comedic farces or historical reproductions or fantastical allegories. However, whether and how well this potential is realized depends on the author. To some extent, it depends on the author’s conscious awareness of and ability to empower the story’s mythic sub-structure. But I would say, even more perhaps, it depends on the author’s personal touchstone with the mythic subconsciousness that lives within them.

If we think of story as being like a dream, we are not too far from the truth. Story—true, deep, initiatory story—is something that arises from an inner depth existing beneath and beyond egoic consciousness. We are more likely to find these stories by “channeling” them than by trying to brainstorm them.

Like dreams, stories are innately symbolic—even, and perhaps especially, when we do not realize it. As authors, we cannot always explain where our best work comes from. Often, it may seem it does not come from us. It was given to us. We are the first to be changed by it. Indeed, we may spend the rest of our lives not quite understanding it.

Also like dreams, I believe it is useful to take one more step back from the hyper-detailed and hyper-realistic showing of fiction. Until we do so, we are likely to think our stories are peopled by a varied and dimensional cast, perhaps purposefully created by us to showcase a vast number of perspectives and lifestyles. When we go deeper, we may see instead that the deepest and most mythic stories represent a single psyche—perhaps the author’s, perhaps a bit more specifically the protagonist’s, but ultimately the collective psyche.

Some schools of dream interpretation remind the dreamer to consider that everything that shows up in a dream is you. That is, it is not your father in the dream; it is some aspect of your own psyche wearing the face of your father. The same can be said of a story. Every character in the story—indeed, everything in the story—is an aspect of one psyche. The hero, the antagonist, the love interest, the mentor—all are representations of a unified psychological perspective and experience.

The deep resonance of stories that work—stories that initiate us—is the result of this inner unity. Audiences resonate because they’re watching externalized inner conflicts of the self. If you start examining stories from this perspective, you may be amazed at what you discover.

A quite obvious example is The Lord of the Rings. I particularly remember the first time I saw the scene in Fellowship of the Ring, in which the characters flee underground into the Mines of Moria, where they awaken goblins and trolls in the darkness. In so many ways, this can be seen as a descent into the unconscious and a confrontation with the shadow monsters who reside forgotten there.

The Balrog confrontation symbolizes the psyche’s descent into shadow.” (The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), New Line Cinema.)

Another vivid example of this inner-psyche theater can be found in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. Nearly every character in Chihiro’s journey can be read as an aspect of the self.

Her parents’ careless greed is the egoic appetite that abandons her to the unconscious.The enormous baby, Boh, is the unruly inner child who must be reparented before growth can occur.Yubaba, the domineering mistress of the bathhouse, embodies the controlling authority of the superego.Haku functions as the animus—an inner guide and companion who helps Chihiro navigate transformation.No-Face represents the shadow self: a ravenous, distorted self that can only be healed through compassion and reintegration.In this light, Spirited Away becomes not simply a fantastical coming-of-age tale, but a symbolic map of psychological wholeness.

Miyazaki’s Spirited Away shows how every story is myth: each character symbolizes an aspect of the self, from the shadow in No-Face to the inner child in Boh. (Spirited Away (2001), Studio Ghibli.)

And in a more realistic example, we can see how the various characters in Pride & Prejudice represent facets of a single psyche:

Elizabeth and Darcy embody the central tension between pride and humility, shame and love.Jane reflects openness and generosity.Lydia personifies unchecked impulse.Mr. Collins plays the part of obsequious conformity.Lady Catherine stands as rigid authority.Read this way, Austen’s novel becomes not just a social comedy but an archetypal drama of the self learning to reconcile its contradictions and move toward wholeness.

Lizzie and Darcy reflect the psyche’s struggle with pride, shame, and connection. (Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.)

Archetypes as Living Forces in Storytelling

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

For writers, one of the most useful tools for enlivening the power of mythic storytelling is to access the innate power of character archetypes.

With all things archetypal, it is crucial to interact with archetypes not as simplistic stereotypes but as living forces. Put simply: we don’t get to dictate what archetypes do. When we have truly accessed them, they tell us what they will do. When we have truly understood them, we feel it all the way down to our bones. Archetypes are dynamic energies peopling initiatory arcs. They surface in different guises but always point to universal human epochs.

As writers, we can access these forces consciously to deepen our character arcs, themes, and story arcs. The most obvious way we can work with these archetypes is to learn about them through the old stories. But they are found everywhere. I would go so far as to say they are found in every story that works. More than that, they are inherent—if perhaps latent—within each of us.

As human beings (and especially as human beings with active imaginations), we already have a deep understanding and recognition of these archetypal forces—if we are brave enough to face them. This cannot be taken for granted. It can often feel much easier to ignore the call of initiation and transformation. Cutting the journey short before we finish the Dark Night of the Soul can often seem wiser. Ironically, remaining cozy and cynical in the affirming arms of despair can feel much safer than daring to keep walking into the unknown of transformation.

What archetypal storytelling—mythic storytelling—demands of us as storytellers is that we face the archetypes themselves with authenticity and with humility. Mythic storytelling demands that we listen to the deepest, loudest, softest truths within us. We know when what we are writing is mythic and archetypal—whether we call it that or not. We know when what we are writing is the truest thing it is possible for us to write. We know in our hearts. And I do not say “hearts” lightly. The heart is a much better storyteller than the head.

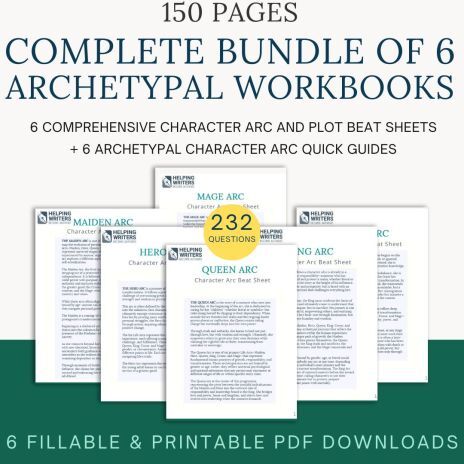

The head, however, remains a worthy ally on this journey. It is not, as it so often thinks, the protagonist. But it is a helpful sidekick. To that end, studying the mythic journeys in literature can be extremely helpful—whether the Hero’s Journey or the five further archetypal journeys I discuss in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs. (Writers can apply these insights practically through my Archetypal Character Arc Worksheets. This worksheet bundle is, in essence, a companion workbook to Writing Archetypal Character Arcs. If you’d like help charting any of the six archetypal character arcs—Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, and Mage—you can check out the worksheets I just released. If you want them all, be sure to check out the discounted bundle.)

Story is not just “about life.” It’s a dream we dream together. It is a map for transformation. If we look into the past, history tells us our storytellers were our seers, our shamans, our wayshowers, our most respected elders.

Now, we are all storytellers. We all bear this great burden to look beyond what everyone else can see and to hone the transformative truths that are meant to initiate not just us but every member of our tribe.

To do that, we must start by remembering what story really is. It is not just entertainment. It is not just escapism. It is not just pleasure. It is not just a source of income.

What is story? I believe the archetypal shape of story is, fundamentally, a truth. Perhaps even the Truth. It is the power to change the world—over and over and over and over again. It is the power to change us. It is the power to bypass our limited egoic perceptions of ourselves, others, and our world and to show us into the wyrdest depths of what it means to be human. It is a dream we dream that also dreams us. It is initiation. It is transformation. It is change. It is myth.

Frequently Asked QuestionsWhat does it mean to say all stories are myth?It means that beneath every plot and genre lies a universal archetypal pattern. From epic fantasies to contemporary romances, all stories echo mythic structures that reflect the psyche’s journey of transformation.Can hyper-realistic stories still be mythic?

Yes. Even the most realistic fiction carries symbolic depth if the writer taps into archetypal storytelling. A courtroom drama or slice-of-life novel can still follow the mythic blueprint of initiation, transformation, and return.Why do archetypes resonate so deeply with readers?

Because archetypes are not stereotypes. They are living psychological forces. When writers use archetypal character arcs, readers feel as though they are watching their own inner conflicts dramatized on the page.How can writers use archetypal character arcs in their stories?

Writers can use arcs like the Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, or Mage as blueprints for character development. These journeys help ensure stories resonate with mythic power and emotional authenticity.In Summary

At their core, all stories are myth. No matter the genre or style, narrative always springs from the archetypal blueprint of the psyche. Story is not simply a mirror of everyday life but a symbolic map of transformation—a dream we dream together. When writers embrace this mythic foundation, they create stories that not only entertain but initiate both writer and reader into deeper self-awareness and lasting change.

Key TakeawaysAll stories are myth. Beneath plot and genre lies the archetypal blueprint of transformation.Story is psyche. Every character and force reflects a facet of the self.Archetypes are alive. They are not tropes but dynamic psychological energies.Hyper-realism needs myth. Realism alone risks losing depth; archetypal foundation restores resonance.Story transforms. Writers and readers alike undergo initiation through narrative.Want More?

Archetypal Character Workbook (Full Bundle of 6)

If you’d like to put these insights into practice, explore my Archetypal Character Arc Worksheets—a series of six fillable, downloadable guides designed to help you chart mythic journeys for your characters. Each worksheet breaks down one of the six archetypal arcs—Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, and Mage–into structural beat sheets, reflective questions, and story prompts. Whether you’re writing epic fantasy or modern literary fiction, these tools will help you harness archetypal storytelling, deepen your characters, and unlock the mythic power within your narrative. Find the full set (including the discounted bundle) in my Etsy store.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you see your own stories as mythic at their core? How do you think recognizing the archetypal foundation of storytelling might change the way you write? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Why All Stories Are Myth—and How They Transform Us appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 30, 2025

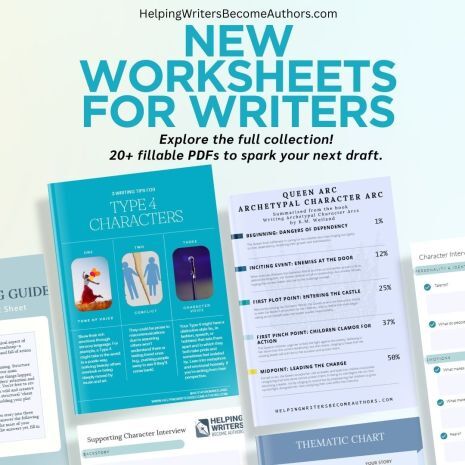

New Worksheets for Writers: Fillable PDFs to Spark Your Story

Sometimes the “quick little projects” are the ones that surprise me the most! Back in the spring, I thought it might be fun to put together a few simple printable writing worksheets—something light and easy, just a side project before the second edition of my Structuring Your Novel Workbook comes out this October.

Of course, you know how that goes.  One idea led to another, and before long my “tiny project” turned into a whole collection of 20+ digital writing resources. And honestly? I had a blast making them. (Seriously. I had to make myself stop!)

One idea led to another, and before long my “tiny project” turned into a whole collection of 20+ digital writing resources. And honestly? I had a blast making them. (Seriously. I had to make myself stop!)

Now, after months of work, I’m excited to share them with you!

Why I Created These Worksheets for WritersWhen I was in grade school, I had a “Write Your Novel” kit that came with worksheets. I can still remember how excited I felt sitting down with those pages—answering questions, filling in blanks, and dreaming up characters and stories. Secretly, that early love of worksheets has never left me. To this day, I still find them ridiculously fun.

Of course, worksheets should never be about ticking off boxes or forcing your story to fit into rigid rules. Writing begins and ends as discovery. But sometimes we all hit blind spots:

An arc that feels flatA theme that won’t come togetherA character who just isn’t coming aliveThis is where worksheets shine. Worksheets are tools to help you spark fresh insight, troubleshoot weak spots, and unlock ideas you didn’t know you had.

My goal was to design practical, easy-to-use tools that:

Give you direct access to the writing techniques I teachSpark new insights into your characters, themes, and plotsOffer flexible, fun ways to brainstorm and outline your storiesWhether you’re working on a novel, screenplay, or even an RPG campaign, these fillable PDF worksheets for writers are designed as creative companions for your storytelling journey.

Browse the entire collection of 20+ worksheets here: [Grab the Worksheets!]

Browse the entire collection of 20+ worksheets here: [Grab the Worksheets!]

If you’re not sure where to start, I’d recommend checking out two special bundles:

The Archetypal Character Arc Cheat Sheets – Provides quick-glance guides to all six of the major archetypes in the Archetypal Life Cycle. For those of you have been asking, this is really a companion workbook for Writing Archetypal Character Arcs . (And, who knows, if you love the digital worksheets, my next project may be collecting them into a paperback!) The Enneagram Character Arc Cheat Sheets – An 18-worksheet collection for creating powerful arcs (both Positive and Negative) for all nine personality types.Both bundles are steeply discounted so you can grab them at the best value, rather than purchasing each worksheet individually.

After that, here are a few standouts I think you’ll love:

Character Interview Worksheet – 100+ questions to dig deep into your protagonist’s psychology, habits, and quirks. Perfect if you want to truly know your character inside and out. Supporting Character Interview Worksheet – 30 targeted questions for side characters, because your story world comes alive only when all the characters feel real. Character Arc Quick Guide – Beat sheets for all five major arc types (Positive, Flat, Disillusionment, Fall, and Corruption). A handy way to clarify your character’s journey at a glance. Story Structure Beat Sheet – A step-by-step breakdown of the classic seven-beat structure. Use it to tighten pacing or map out missing beats. Theme Worksheet – A 12-page guided exploration of your story’s thematic heart, with resources on character arcs, core elements, and dozens of bonus links.What’s Inside the Worksheets for Writers (The Bonuses!)These aren’t just worksheets—they’re mini writing toolkits. Each one comes with an extensive PDF resource guide packed with links to my most helpful blog posts, podcast episodes, and free tools. That way you can dig deeper into the craft while putting ideas directly into practice.

You’ll also find extras like:

Quick-reference infographics to keep story structure principles at your fingertipsExpanded guidance for flexible worksheet useTips and curated examples to inspire your processSince this is a brand-new launch, your support means so much! You can purchase the worksheets directly from my store, but I’d especially appreciate if you order through my Etsy shop. Every purchase there helps me build credibility and visibility on the platform.

And if you find the worksheets helpful, leaving a quick review on Etsy would be an enormous help in boosting the shop’s ranking!

I made these worksheets with you in mind, and I hope they give you the same spark of excitement I felt while creating them. I can’t wait to see what stories they help you bring to life!

Explore the new worksheets here: [Worksheets Here!]

Explore the new worksheets here: [Worksheets Here!]

The post New Worksheets for Writers: Fillable PDFs to Spark Your Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 25, 2025

What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling? (+ 6 Ways Storytelling Can Find Its Soul Again)

I’ve been feeling it for a while now—that dull, uninspired thud when the credits roll on modern storytelling. More and more, movies in particular leave me feeling unmoved and oddly detached. Bored, really. Once upon a time, I’d walk out of the theater buzzing. I’d carry that story around with me for days, sometimes weeks. I called it a “story high.”