K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 2

July 28, 2025

7 Ways to Watch and Read More Intentionally

In a world flooded with stories—books, shows, films, and endless social content—it’s easy to fall into passive consumption. But as writers and creatives, what we take in matters just as much as what we put out. To write with depth, clarity, and resonance, we must first learn to read more intentionally and watch with greater awareness. Intentional consumption isn’t about being rigid or “highbrow.” Rather, it’s about choosing stories that challenge us, feed us, and reflect the kind of storytelling we want, in turn, to create.

In a world flooded with stories—books, shows, films, and endless social content—it’s easy to fall into passive consumption. But as writers and creatives, what we take in matters just as much as what we put out. To write with depth, clarity, and resonance, we must first learn to read more intentionally and watch with greater awareness. Intentional consumption isn’t about being rigid or “highbrow.” Rather, it’s about choosing stories that challenge us, feed us, and reflect the kind of storytelling we want, in turn, to create.

Earlier this month, I offered a post about “Why Intentional Storytelling Matters in an Era of AI and Algorithm-Driven Content.” It was an exploration of all the reasons intentional storytelling has always mattered and perhaps matters more than ever in our modern era of ultra-speed and convenient shortcuts. The first comment on that post (amongst many in a wonderfully rich discussion) was from Heather J. Bennett who wrote:

It’s also a problem with lazy readers who aren’t taking the time to slow down and read the story as it’s written. … Their attention spans for reading for the nuance of the storytelling is shorter with understandable life priorities and needing to get things done.

This immediately spoke to something I was already thinking about, which is that intentional consumption—reading and watching—is just as important, if not more so, than intentional creation. However, this isn’t to separate writers from consumers or suggest “others” should bear the blame for “bad” stories being all too acceptable to the market. After all, we as writers are first and foremost members of that same audience. To the degree we seek to create intentional art—art that that is “on purpose” and for a reason—then this is a reminder that our reading/watching choices not only inform the general market, but also the quality of what we’re inputting into our own experiences and how that that affects the output in our writing.

In This Article:How Does What You Read and Watch Shape Your Writing?How Reading and Watching Low-Quality Content Affects Your WritingDo Stories With Agendas Harm Good Storytelling?What Does It Mean to Read More Intentionally as a Writer? (7 Tips)How Does What You Read and Watch Shape Your Writing?Which is more important: writing intentionally or reading intentionally?

It’s kind of a chicken-and-egg question, but ultimately I believe intentional media consumption is more important. Why? Because the personalized landscape of our individual media consumption is the fertile ground out of which grows everything we might hope to create. Someone who chooses media with the utmost intention is unlikely to then create without intention. Even if they did, I have to believe the careful attention to input would still favorably impact the output.

In short, we are what we read (and watch).

No doubt, you’re familiar with the suggestion that you are the average of the five people you’re around the most. Your media consumption impacts you just as greatly. It’s worth examining five of the shows you watch most often and five of the series you most like to read (or perhaps for simplicity’s sake, the type of shows and books you most enjoy) and considering how they have “made” you—for better or worse.

You can also think of it like this: your writing is unlikely to rise above the average quality or thematic messaging of what you read and watch. More crucially, consuming low-quality media risks the dulling of yourself. And if nothing else, even if the effect is neutral, you must contend with the fact that in not asking more of your media, and therefore of yourself, you are missing potential opportunities to raise yourself.

How Reading and Watching Low-Quality Content Affects Your WritingIntentional media consumption affects everyone, but as writers, our interaction with media has the potential to create a greater ripple effect. Not only do our media choices affect us personally (which, of course, necessarily affects our writing), they also directly shape our own works of fiction.

The single greatest rule of thumb when it comes to questioning whether you’re reading and watching critically is to consider whether or not you are reading or watching with your soul.

Fundamentally, what I mean by this is that engagement should bring a certain spark of aliveness. What you read or watch should make you feel alive.

Media is nourishment for our minds and souls. Just as with the physical nourishment of food, we have to consider whether we’re getting enough quality nutrients. Are we consuming junk content or “real” content? Just as with junk food, it’s true enough we all tend toward a soft spot for junk entertainment.

What is junk entertainment?

Empty calories that are satisfying-but-not-satisfying.Adds nothing of real value.Possibly leaches valuable nutrients (i.e., time, happiness, contentment, positivity).Strangely but inarguably addictive.This isn’t to say the occasional cheat day isn’t a worthy part of our lives, but a steady diet of anything that isn’t actively adding value is, at best, a waste and, at worst, actively harmful to both ourselves, our potential readers, and inevitably the collective.

Do Stories With Agendas Harm Good Storytelling?We tend to blame much of our current dissatisfaction with modern media on the fact that storytelling has become ever more polarizing and political. It is not uncommon for the release of even the most popcorn-y of all entertainment—the summer blockbuster—to be bulldozed by political rants of all persuasions. It can be difficult to engage with modern media without guarding against intrusive messaging (and that may even be before we know what the messaging may be).

Many people cry out that stories should not be vehicles for political and social agendas and should get back to being “just for fun” or “just entertainment.” (But maybe you already know what I think about the “just” word in front of stories…)

I do not believe this is the problem. Stories have always been political. By their very nature as an inherently transformational experience, they can’t be anything else. (Never mind that the simple act of reporting on the human condition is also inherently—and often dangerously—political.)

Neither is the problem that “real” stories and “important” stories shouldn’t be fun. Indeed, I can’t help but think that the most wildly entertaining genre stories are those with the most potential for impacting humanity—not only through their sheer accessibility but also through their natural tendency toward the simple depth of the archetypal experience.

No, in my opinion, what we are ultimately reacting against—and, out of sheer exhaustion, increasingly putting up with—are specific trends that have taken us away from the true heart—the true soul—of what story really is.

Problematic storytelling devices we should be conscious of when consuming (and should not excuse) include:

Plot-driven stories that neglect character arcs (i.e., characters made to serve plots rather than plots made to serve characters).Entertainment-first storytelling vs. artistic integrity (i.e., seeking stories that will supposedly sell vs. writing stories of originality and personal intensity).Flat stereotypes vs. rich archetypes (i.e., writing tropes and plot formulae vs. meeting, understanding, and mining the deeper archetypal wisdom of story transformation).Storytelling instead of story channelling (i.e., creating stories primarily or entirely from our left brain’s logic vs. listening to what wants to come through the right brain).What Does It Mean to Read More Intentionally as a Writer? (7 Tips)In many ways, I think reading and watching critically is actually more difficult than mindful storytelling. Partly, this is because we often feel we have less control over what media is placed before us to consume versus what we can consciously choose to create. Mostly, however, it is because consumption is a relatively passive action—we simply sit and accept what we are given, even if we don’t necessarily like it—whilst creation necessarily demands our entire active participation and therefore choice.

As such, and because watching and reading as a writer is such an intrinsic part of the larger storytelling process, upping the ante on media literacy for writers becomes a deeply important topic. To that end, here are several suggestions for nourishing your creative mind, all of them straight from my own practices in intentional media consumption.

1. Stop Consuming Content That Doesn’t Spark CuriositySo, yes, the first step is to just: stop watching and reading.

If there’s no spark, turn it off. Don’t consume mindlessly just because it’s there. Just say no.

Although I have always had the habit of watching a hour or two of TV or movies in the evenings, recently I decided to take an indefinite break, for the simple reason that I was spending upward of two hours every day watching stuff that, for the most part, I didn’t even like. Part of this reaction is due to my own moods and tastes at the moment, but part of it is the very real scroll of doom on Netflix and other streaming services.

By stepping away from habitual viewing, not only can I spare myself from increasingly unintentional media choices, I can also devote those two hours to more productive pursuits—like reading a (good) book or working on my own writing. If a movie or show comes along that I’m actually excited about (Stranger Things 5, looking at you!), I’ll watch it.

Until then, impress me. I’ll wait.

2. Make Space for SilenceI have always felt (with no small amount of satisfaction) that watching movies and reading books was just part of my job. But amidst the ever-increasing cacophony that is my (almost) 40-year-old brain in the year of 2025, the need to step back and hear myself has become perhaps an even more important part of that job. As writers, we are (and, I think, should be) influenced by the media collective. But our stories ultimately come from us, and the only way to truly find them is to make sure we can hear our own inner whisperings louder than whatever junk-food TV might be playing in the background.

3. Practice Reflective Watching and ReadingWhen you do read or watch, take the time to think critically about what you consume.

For a writer, this may begin by critically analyzing technique.

As a 21st-century human, this demands noticing where we might be copping to habitual and ingrained responses (either for or against).

Perhaps most important, it should mean noticing how you feel.

Questions to ask about intentional reading and watching:

How are the feelings that are coming up (whether big or small, for or against, happy or angry) a mirror for you?What do you think the author wanted you to experience>How did your actual experience line up with this?These are first and foremost soulwork questions, but inevitably also questions about honing writing technique.

4. Challenge Yourself With Unfamiliar StoriesReading with intention often means going off the beaten track. Instead of simply choosing the latest show available on streaming or the newest bestseller in your favorite genre, take your autonomy in your hands and make the commitment to be bold. Read things that are edgy.

Edgy stories are those that push you because:

They require skillful comprehension,They ask you to step beyond what it is triggering, confronting, or uncomfortable.They beckon from outside your current comfort zone or personal interests.They represent something strange, frightening, or “other.”They scare you (just a little bit).5. Revisit Books and Films That Moved YouReturn to some of your old favorites—those that spoke to your mind, heart, and soul. Sometimes I have to go back to the books and movies that made me want to be a writer in the first place—just to see if the old magic is still there. And it is. And it always gives me hope, because it means story is still there. It’s still alive—on the page, on the screen, and in me. Story is just as vibrant and moving and exciting as it ever was, as long as we’re looking in the right places.

6. Create Intentional Reading ChallengesA good reading (or watching ) challenge is always a good way to mix things up, to make sure your choices are intentional, and to explore story terrain you may otherwise have missed entirely.

Three of my ongoing challenges are:

Reading the classics (which I define as any famous book written prior to 1980).Reading the Pulitzer winners for fiction.Watching all the movies in my collection in reverse order starting in the 1930s.Here are a few ideas for reading or watching challenges:

An author who challenges you.A genre you’ve never read.A book you know sits across from your current ideological fence rail.A movie from each decade.A foreign film.Something you used to love and something you used to hate—just to see if anything has changed.The point is to detour from comfortable ruts and to rouse curiosity for the unknown. You never know what you’ll find—probably your next story idea!

7. Read for True Fun, Not Passive DistractionFinally, it’s worth saying that intentional media consumption is not about forcing yourself to become a highbrow literary elitist (unless you want to be). Rather, I believe the single greatest sign we’re on track with our reading and watching is that we are having fun.

Not mindless semi-satisfaction.

But true heart-pounding, gut-clenching, laughing-out-loud, squealing-in-the-theater, delighted, ignited, enlivened fun.

Yes, story is indeed entertainment, but it is never just entertainment. It is engagement. True fun is never mindless because it shows us the core of our own passions and truths.

So perhaps the best rule of all for reading and watching with intention is to ask: “Am I having fun?” And if you’re not: don’t.

***

If stories are nourishment, then writers are the cooks who must taste every ingredient before serving it up. What we take in becomes the flavor of what we offer the world. Choosing to read more intentionally is more than a personal practice—it’s a creative responsibility. When we consume with care, curiosity, and courage, we elevate our own craft and influence the stories being told around us. The world doesn’t need more noise. It needs storytellers who are listening first.

If writers don’t read/watch with intention, who will?

In Summary:Intentional media consumption isn’t just about watching “better” shows or reading “smarter” books. It’s about aligning your media choices with your creative purpose. When you engage with stories that challenge, inspire, or even unsettle you, you’re nurturing the very soil from which your own stories grow.

Key Takeaways:You are what you consume. Your media habits shape your inner creative landscape.Junk content dulls creative potential. Just like food, low-quality stories leave you hungry for meaning.Reflective consumption enhances storytelling. Asking why something moved you (or didn’t) sharpens your writing instincts.Challenging content helps you grow. Step beyond your comfort zone to discover new perspectives and storytelling techniques.Fun is a compass. True fun—joyful, engaged, soul-stirring fun—is the best indicator of intentional story alignment.Want More?

Next Level Plot Structure (Amazon affiliate link)

If you’re feeling inspired to not just consume stories more intentionally but to write them more intentionally too, check out my most recent book Next Level Plot Structure. This one’s for writers who are ready to move beyond just hitting plot points to really exploring the deeper architecture of story—including plot structure’s mirror-like symmetry, the four symbolic “worlds” found within every story, the pacing beneath the beats, and the powerful emotional logic that makes a plot resonate. It builds on what I taught in Structuring Your Novel, but goes further into the soul of structure itself. If you’ve ever sensed there’s something deeper going on in great stories—even if you couldn’t quite put your finger on it—this book will help you tap into that, shape it, and use it with purpose. It’s available in paperback, e-book, and audiobook.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you think writers have a responsibility to read more intentionally—and if so, what’s one story that changed the way you think about your own writing? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 7 Ways to Watch and Read More Intentionally appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 21, 2025

What Makes a Story “Bad”? A Guide to Why Your Narrative Isn’t Working

We’ve all experienced it: a story that looks good on paper, features big-name characters, or starts with an intriguing premise—but somehow falls flat. Maybe the characters feel hollow, the plot drifts without purpose, or the ending lands with a thud. But what actually makes a story “bad”? Are there pitfalls you can look out for that can save your story? More importantly, how can you avoid these mistakes when writing or editing?

We’ve all experienced it: a story that looks good on paper, features big-name characters, or starts with an intriguing premise—but somehow falls flat. Maybe the characters feel hollow, the plot drifts without purpose, or the ending lands with a thud. But what actually makes a story “bad”? Are there pitfalls you can look out for that can save your story? More importantly, how can you avoid these mistakes when writing or editing?

Bad storytelling is one of those things where you “know it when you see it.” Or, rather, you feel it. Sometimes when you read or watch something that isn’t working, it can be hard to put a finger on what’s gone wrong. And yet your gut knows. Your visceral reaction to the story may range from a mild sense of dissonance, confusion, or even boredom all the way up to outright irritation or even anger.

The good news is that, as writers, the moments when you start feeling the ick are the best teaching moments possible. They give you the opportunity to look deeper into your own experience and examine why the story prompts this reaction. Although the reasons can span the gamut and are often quite subjective and personal, today I want to look at five of the most common mistakes that can create an objectively bad story. I’ve included examples of stories in which the topic in question was well-executed as well as stories in which mistakes turned what might otherwise have been good stories into bad stories.

In this Article:Characters Who Don’t Accurately Reflect HumanityCharacters Who Don’t Adapt/Learn/ChangePlots That Are Constructed Around Actions Rather Than MotivesPlots That Don’t Ultimately Mean AnythingThemes That Are “On the Nose”What Makes a Bad Story? The Top 5 Reasons Stories Fail1. Characters Who Don’t Accurately Reflect HumanityIt’s not who you are underneath. It’s what you do that defines you.

When it comes to characters, truer words were never spoken than these from Batman Begins. This also goes back to that all-important adage, “Show, don’t tell.” Basically: audiences will always judge your characters based on their actions before they look to any other cues. Even if you’ve created a character who is archetypally coded as a good person, that isn’t enough by itself to prevent audiences from judging and disliking this character if the character is acting out not-so-good behavior.

Worse, if you suggest to audiences that a character is good, only to have that character’s actions fail to accurately reflect how such goodness plays out in real life, the character will likely seem hypocritical or worse. In real life, this is how we interpret such inconsistent behavior from other people. Why should we expect audiences to see our characters any differently?

But make no mistake, this is tricky, since authors too often fail to see their characters with the same objectivity as readers will. Not only do we tend to see characters how we intend to portray them, we also tend toward blindness where our skills aren’t pulling it off.

Bad Example: In the BBC series Land Girls, the character Joyce is presented as brave, plucky, humble, and hard-working. She courageously volunteers as a Land Girl to serve her country during World War II, soldiering on in the face of her fear for her beloved husband, who is a rear gunner in the RAF. The problem (amongst many in this beleaguered series) is that Joyce was written to consistently perform actions that showed her to be selfish and controlling—not least in abandoning her wounded husband for mistakes he made when he had amnesia in France.

Land Girls (2009-11), BBC One.

Good Example: The secret to remedying this problem is to write dimensional characters. Of course, no character is good all the time. In fact, such characters tend to be boring. But writing a character with layers and complexities is different from inconsistently presenting virtues and vices. Any truly good story does this one well, but a recent example that comes to mind is Wicked, which creates a complex dynamic between frenemies Elphaba and Galinda. Both characters present internal ironies: Elphaba is not as bad as she lets others think, and Galinda is not as good as she lets others think. Instead of glossing over these complexities, the story explores them honestly, not least in authentically representing the consequences of both characters’ decisions. The most obvious example is that Elphaba must eventually take on the role of the renegade everyone has always thought her, not least because it is difficult for others to believe the truth beyond the roles she has always played.

Wicked (2004), Universal Pictures

2. Characters Who Don’t Adapt/Learn/Change

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

When characters don’t learn from their mistakes, and instead keep doing the same foolish nonsense over and over throughout the story, the intention on the author’s part is usually to milk a certain trope for all it’s worth. Comedy is an obvious example—and when the character in question is a supporting character this can sometimes work. However, although audiences will willingly accept vast shortcomings from a character, they will not long suffer a fool who refuses to learn and grow from the consequences of personal actions.

Stories are change. If everything is the same at the end as it was at the beginning, you don’t have a story. Even in Flat Arc stories, in which the protagonist does not change, the story world does change. Stories are ultimately studies in evolution—whether deeply personal and moral or just practical. If characters fail to grow over the course of the story, this not only lends itself to repetitive action, it also fails to accurately portray an intriguing individual who is worth following around for the entirety of a movie or book.

Bad Example: Let’s go back to some millennial rom-coms here. The Wedding Planner showcases the major problems of the genre in that the characters learn little to nothing from the conflict. In particular, Jennifer Lopez’s female lead shows as little grasp of self-worth at the end of the story as she did at the beginning. She changes her mind about potential love interest Matthew McConaughey, even though he has done nothing to erase the fact that he is a proven cheater—having compromised his relationship with his fiancée (who is not Lopez) repeatedly over the course of the story.

The Wedding Planner (2001), Sony Pictures.

Good Example: Both lead characters in the classic You’ve Got Mail learn from their mistakes and limiting perspectives (their Lies) over the course of the story. Both behave abominably at times, but their coming together in a relationship at the end of the story feels satisfying rather than frustrating because both have also proven their capacity to change. (Indeed, perhaps the most beloved romance of all time, Pride & Prejudice, follows a similar pattern and works precisely because the main characters change so dramatically in the end—particularly with Darcy’s benevolent rescue of Lizzie’s disgraced sister.)

You’ve Got Mail (1998), Warner Bros.

3. Plots That Are Constructed Around Actions Rather Than MotivesMost of the problems in this list come down to the central issue of characters that exist to serve the plot, rather than plots generated by the characters. The simplest way to check your story is to ask whether you’re inventing actions for your characters and then tacking on the motives afterward—or whether you are allowing actions to arise naturally out of deep motivations. We see this often in stories of all genres, but perhaps nowhere more obviously than in action-oriented stories, in which scene dynamics are constructed to take advantage of, exemplify, and hammer home certain character traits.

This is done to create what is intended to be the pleasurable experience of watching characters act out certain dynamics. Ironically, the result often fails for the basic reason that the character’s actions, however interesting in themselves, are not arising from or creating causal or consequential growth.

Bad Example: The recent BBC adaptation of Winston Graham’s historical drama Poldark diverged from its source material in its fifth and final season. The result was a noticeable shift in the quality of writing for the very reason that the writing became more about making the characters do things for the sake of the plot, rather than allowing the plot to rise realistically from the characters’ actions (something the series had done very well up until this point). The final season harps endlessly on the protagonist Ross Poldark’s “recklessness,” plunging him into increasingly foolish and absurd situations—no doubt in the belief that the audience has always enjoyed this personality trait. The difference in this season is that the character’s motivations are retrofitted onto his recklessness, rather than the recklessness arising as a natural personality response to his deeper motives.

Poldark (2015-19), BBC One.

Good Example: Although there are a few moments in the series that push this line, Yellowstone‘s presentation of Beth Dutton generally offers a strong example of a larger-than-life character who creates dynamic and interesting plot events that arise naturally from her own personality and motivation. There is rarely a sense that Beth is being forced to behave in certain ways just to create these plot events or to allow for potentially shocking or intriguing scenes. Rather, the force of Beth’s own passionate character creates the plot events as she goes. She is a particularly obvious example, since her personality is so aggressive and over-the-top, but she shows how writers can get the best plots simply by asking, “What would this character do in this situation?” instead of “How can I get this character to realistically do this thing?”

Yellowstone (2018-2024), Paramount Network.

4. Plots That Don’t Ultimately Mean Anything

Next Level Plot Structure (Amazon affiliate link)

Stories have to mean something. Otherwise, why bother? Life is about meaning. The act of living is about finding that meaning, and stories are meant to reflect that. If they don’t offer meaning—a point—then not only do they almost always fail to entertain, they also miss out on a much greater potential.

How do you inject meaning into a story? It doesn’t have to be anything grand or sweeping or even deep. It just has to offer an ending in cohesion with the story that preceded it.

The meaning of a story is always found in the ending. The ending proves what the story was about. This means that, no matter how great the first 90% of your story, if the ending doesn’t offer a suitable commentary on everything that has come before, the plot won’t ultimately mean anything. Every scene in a story’s plot must drive the story’s conflict toward an endpoint that is cohesive and appropriately tense with all that came before.

Bad Example: I’m going to pick on the final season of Poldark one more time. It’s worth noting that, in the books, this season is not the end of the characters’ stories. However, for the purposes of this adaptation, the fifth season is the end and therefore the only opportunity for audiences to pull a final sense of meaning from the saga. Unfortunately, the comparatively poor writing in this finale not only weakened the overall characterization, particularly of Ross, but also failed to hone in on what had always been the throughline and point of the story: the conflict between Ross and his nemesis George Warleggan, [SPOILER] who is here relegated to the background with a bizarre portrayal of delusional madness in the aftermath of his wife’s death [/SPOILER].

Poldark (2015-19), BBC One.

Good Example: The contrived “ending” of Poldark‘s Season 5 aside, the overall presentation of the story in the previous four seasons were exemplary—not least because the plot naturally returned again and again to core themes: Ross’s tempestuous relationship with his wife Demelza, his obsessive feud with George Warleggan, and his passionate championing of his mine workers’ rights. Every ending of every season leading up to the final one felt satisfying exactly because the tightly focused plots allowed for outcomes that not only felt cohesive but that carried the weight of a deeper resonance.

Poldark (2015-19), BBC One.

5. Themes That Are On the Nose

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Good themes arise naturally from plots that are driven by strong characters. Although you can study theme (and in my opinion should—check out my book Writing Your Story’s Theme), you really don’t have to for the simple reason that if your plot and character are working well, so is your theme. In short, if you avoid all of the previous pitfalls, you’re probably already writing a story with innately chewy themes. On the flipside, however, is the problem of writing themes that feel too obvious or on the nose.

These are usually stories in which the theme is either explicitly harped upon (as a sort of “moral of the story”) or stories in which the thematic metaphor is blatant (i.e., the story’s external conflict is too obviously contrived as a mirror of the theme). There’s nothing wrong with an explicit thematic metaphor (such as the communism of Animal Farm or the underworld of grief in What Dreams May Come). But a good rule of thumb is that the more explicit the thematic metaphor, the more emotional complexity the story requires in portraying its moral quandaries.

Bad Example: Thunderbolts* was a much better film than much of what Marvel has been putting out in the last six years. Unfortunately, it suffered from a lack of thematic depth for the very reason that it leaned all of its thematic weight into the explicit metaphor of mental health and depression. [SPOILER]The bad guy is literally depression—a sentient and all-consuming void that has become disassociated from its human originator.[/SPOILER] On the surface, this is an excellent thematic metaphor, especially since it ties into the protagonist Yelena Romanov’s own existential struggles. And yet the film felt decidedly shallow in the face of such a tremendous thematic exploration, simply because its plot and character dynamics did not catalyze the theme. The characters and their involvement with this antagonist were largely incidental, thematically pertinent only tangentially through their personal histories with PTSD and guilt.

Thunderbolts* (2025), Marvel Studios.

Good Example: A much better example of cohesive themes is another Marvel entry, The Winter Soldier. Although structurally much the same as Thunderbolts*, this film is able to deepen itself beyond simple action-genre tropes into an earnest exploration of the complex intersection between moral values and relational loyalty. The reason its themes feel far more organic, and as a result more thought-provoking, is because those themes arise naturally from the protagonist, Steve Rogers, and his interactions with every other character, particularly his long-lost best friend Bucky Barnes, aka the Winter Soldier. One notable difference between these two films is that every character in Winter Soldier plays an important thematic role in interacting with the protagonist and prompting his own journey. In contrast, characters in Thunderbolts*, including the nominal protagonist Yelena, are little more than spectators to the main action, which is driven by the seeming bystander “Bob.” They could easily be changed out for an entirely different team of heroes, whereas Steve Rogers is specifically inherent to the plot and theme in Winter Soldier.

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), Marvel Studios.

***

In the end, bad storytelling is usually the result of misalignment between character and action, plot and meaning, theme and execution. The most common narrative failures happen when writers try to force stories rather than uncover them. The silver lining is this: if you can recognize what doesn’t work in other stories (and your own), you’re already halfway to crafting something better. Great storytelling is simply honest storytelling driven by real characters, deep motivations, and resonant consequences.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s a story you wanted to love—but just couldn’t? What made it fall apart for you? Tell me in the comments!In Summary:Stories that fall flat often share the same core problems: characters that lack dimensionality or growth, plots that prioritize spectacle over motivation, and themes that are either nonexistent or overly literal. Understanding these pitfalls can help writers tell stories that are more emotionally honest, structurally coherent, and ultimately more impactful.

Key Takeaways:Characters must reflect human complexity. Viewers judge characters by their actions, not the author’s intentions.Change is the heartbeat of story. If characters (or the world) don’t evolve, the story stalls.Plot must arise from character motivation. Don’t reverse-engineer actions just to create drama.Your ending is your meaning. A satisfying conclusion echoes and elevates everything before it.Themes work best when organic. On-the-nose metaphors often feel shallow without strong emotional grounding.Want More?If you’re ready to dive deeper into what makes characters truly work—and how to build meaningful arcs that drive everything from plot to theme—check out my book Creating Character Arcs. It breaks down exactly how to construct transformative journeys that resonate with readers and anchor your entire story—both plot and theme. You can find it here in my store or anywhere books are sold. It’s available as an e-book, paperback, and audiobook.

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post What Makes a Story “Bad”? A Guide to Why Your Narrative Isn’t Working appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 7, 2025

Why Intentional Storytelling Matters in an Era of AI and Algorithm-Driven Content

These days, it’s easier than ever to write stories that look like stories. I’m talking about stories follow beat sheets, mimic bestselling formulas, and say all the “right” things. But more and more, I see authors tempted to make creative choices based on convenience rather than imagination or integrity. When that happens, we have to ask: are we saying anything real?

These days, it’s easier than ever to write stories that look like stories. I’m talking about stories follow beat sheets, mimic bestselling formulas, and say all the “right” things. But more and more, I see authors tempted to make creative choices based on convenience rather than imagination or integrity. When that happens, we have to ask: are we saying anything real?

Intentional storytelling—the kind that grows from a writer’s unique vision and voice—is at risk of being quietly drowned out by franchise formulas, AI-generated content, and the pressure to produce faster than ever. If you’ve ever felt like you’re just going through the motions instead of creating something that truly matters, you’re not alone. Let’s explore what’s being lost, and what we can reclaim.

In This Article:What Intentional Storytelling Is Not: Avoiding Formula and Empty ContentHow Modern Media Incentivizes Unintentional ChoicesWhy “Just Following the Formula” Falls ShortTools vs. Crutches: Knowing the DifferenceWhat Is Intentional Storytelling? Defining Purposeful, Authentic Narrative CraftWhat Makes Details Matter: Cohesion and ResonanceHow Subtext Reflects the Integrity of a StoryWhat AI Can’t Do for You (Unless You Know Yourself First)Why Intentional Storytelling Matters More Than Ever in an AI-Driven Content WorldHow the Creative Landscape Is ChangingWhy the Story Still Starts With YouTwo Questions to Guide Every Writing DecisionWhat Intentional Storytelling Is Not: Avoiding Formula and Empty ContentHow Modern Media Incentivizes Unintentional ChoicesThese days, I think most people are at least somewhat dissatisfied with the general scope of popular media, particularly movies and TV. Of course, there are stellar exceptions and of course older generations (of which I am suddenly shocked to find I am one!) tend to look back on previous eras of entertainment with no small gloss of nostalgia. But for the past decade, I have looked out onto the entertainment landscape and been increasingly dissatisfied, on a personal level, with what I’m seeing. Although multiple factors play into this (including nothing more than my own evolving perspectives and tastes), I feel the growing trend and temptation away from intentionality is one of the prime culprits.

This is a trend that affects far more than just storytelling. Despite its many benefits—and perhaps its inevitability—the rise of automation, driven by the ever-accelerating pace of life, presents storytellers with ever-growing temptations to take shortcuts. We’ve now reached the point where the most obvious example is the ability to simply have AI write a whole book for you based on nothing more than a premise. But, really, this is just an extreme example at the end of a long line of such shortcuts.

In the interest of identifying what intentional storytelling is, let’s first examine what it is not.

Why “Just Following the Formula” Falls ShortIntentional Storytelling Is Not:Copy/Paste Beat Sheets – Using structure as a paint-by-numbers formula rather than a flexible framework guided by theme and character. (This is not to say such beat sheets can’t be used for inspiration or troubleshooting, but by themselves, they’re dead forms.)

Formulaic Structures – Plugging characters into a pre-set pattern that forces them to act according to the plot rather than allowing plot to emerge organically from character development.

Soulless On-Demand Content – Prioritizing speed and quantity over resonance, originality, or emotional depth.

Writing to “What Sells” – Chasing trends instead of exploring your unique and authentic voice, interests, and truths.

Fan Service-Driven Plotting – Shaping stories purely to provoke views, applause, or box office returns, at the cost of coherence or meaning.

AI-Generated Brainstorming Replacements – Outsourcing vision, subtext, and originality, especially early in the creative process.

Template-Tweaked Tropes – Recycling familiar stereotypes or plot devices without interrogating their deeper archetypal relevance and resonance.

Focus-Grouped Characters or Themes – Designing stories to appeal broadly instead of deeply.

Although I hope the examples in this list are self-evident, they are also quite general. There will always be instances when some or even all of these things add desirable aspects to a story or offer an author guidance or assistance. However, taken by themselves or without calibration, they all point to the two deepest markers of unintentional writing.

Quite simply, unintentional storytelling is either lazy or fearful.

In the one case, the writer is “filling in the story’s blanks” in some way that fobs off the responsibility of making choices or discovering originality, thus eliminating the need to dig into the depths of one’s own truths. In the other, the writer may be fearful that not following certain trends or using certain tools may endanger relevance and, in some cases, livelihood.

Tools vs. Crutches: Knowing the DifferenceThis is not to say most of these tools can’t be used to simplify the storytelling process or to help the professional author keep up with the demands of the market. For example, structural beat sheets can be a tremendous learning tool. Producing content and writing “what sells” is, at least to some degree, just part of the devil’s bargain of profitable art. Writing tropes is, to some extent, unavoidable.

It’s less important that examples such as these be avoided altogether and much more important that they be used with intention. To the degree any tool or opportunity is used without intention, it risks weakening the whole. This has always been true for writers, even of something so small as unintentional word choices. But as the ability to craft whole stories with much greater speed and ease becomes more accessible and, frankly, more tempting, it is vital for authors to maintain artistic integrity in every choice they make for their stories—from the words to the tools to the characters to the plot.

What Is Intentional Storytelling? Defining Purposeful, Authentic Narrative CraftAt its simplest, intentional storytelling is paying attention to everything. It is about becoming aware of every choice you are making for your story—from plot, theme, and characters to the color of your protagonist’s dress or the name of her dog. It’s about choosing narrators on purpose and for a reason. It’s about vetting settings. It’s about honing word choice to perfection.

Why? Some of those things—like plot and theme—obviously matter, since they are your story. But why does something as inconsequential as a color or a random setting really matter?

What Makes Details Matter: Cohesion and ResonanceThey matter for two reasons: cohesion and resonance.

Cohesion is about ensuring every piece of a story is part of a greater unified whole.Resonance is about the effect of that whole: how every small piece sings together to create an effect bigger than itself—a note of magic that resonates to the audience as a feeling, a sense, something supra-linguistic communicated beyond words or images.How Subtext Reflects the Integrity of a StoryUltimately, what we’re talking about is the creation of subtext. Stories are subtext. The stories that truly work—the stories that stay with you long after you finish them—are stories in which the subtext worked. And the subtext only works when the context is contrived of intentional choices.

It’s important not to confuse “intentional” with “conscious.” Although consciousness always brings intention, intention exists beyond consciousness. Although we often speak of brainstorming stories, stories are always first and foremost an act of dreaming—an act of the subconscious, the imaginal self, the symbolic mind.

What AI Can’t Do for You (Unless You Know Yourself First)When it comes to AI, the subject is certainly complex. As someone who makes a living from creative work, I understand firsthand why AI feels threatening. The landscape of my own livelihood has been impacted significantly these past few years, raising many anxieties about an unknown future. In the spirit of learning about something before forming opinions about it, this year I’ve been experimenting with it in many different ways, particularly looking into how it can help me on the business end of things (i.e., left-brain pursuits such as SEO, research, business brainstorming, and marketing copy) and have often found it helpful. However, my chief concern with its advent is that in relying on it for right-brain activities, it may easily interrupt our dreaming selves and, indeed, do too much of our dreaming for us.

To know the difference requires, first, a keen attention to one’s own imaginal workings and, second, a perhaps even keener attention on the intention of the choices we make for our stories, the origins of those choices, and above all their resonance with ourselves—or what I have always called our “story sense.” This is that deep and true part of ourselves—intuition, sixth sense, gut feeling, subconscious—that knows when something is ours or not—when something is true for us or not.

As you seek intentional storytelling, you can move beyond vigilance and awareness to a deeper intimacy with your own personal truths and symbols. Although left-brained, logic-based brainstorming remains a helpful process for most of us, it cannot replace the right-brained raw creativity of simply imagining. I use a process called dreamzoning to intentionally shut off my logical brain and go deep into my imagination. I’ve rather come to feel that this act of dreamzoning is one of the most subversive approaches an author can take in these times. (Although I offer guided meditations to help with this process, you need nothing more than a little time alone to stare into space.)

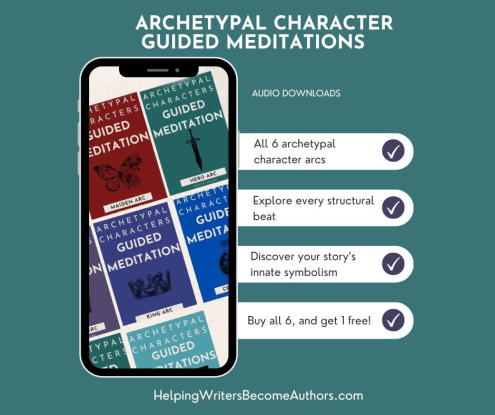

Archetypal Character Guided Meditations

Ultimately, storytelling with intention is nothing more than storytelling with honesty, integrity, discipline, and bravery. It begins when we first look deeply into ourselves and write with honesty what is there—no matter how unformed, ill-formed, frighteningly personal, vulnerable, or imperfect—rather than simply mirroring back what we see in others’ stories.

We follow that with the integrity—the wholeness, the cohesion—of making choices that align with those depths, with what feels right for us, with what serves to produce a story that has its own integrity, its own wholeness.

Then comes the discipline of staying with it, even when it’s hard, even when it seems there must be an easier way, a more fun way, a more profitable way, a less scary way. Staying in service to our own integrity is the surest path to any of these things. But even when it seems anything but, we must keep asking the questions that tell if we are indeed staying true to ourselves, our visions, and our stories—not our egos’ stories, but our deepest stories.

And then we face it all with courage—because there is no other way. Storytelling—real, true storytelling (okay, honestly some fake storytelling too) is the most frightening thing in the world. To write with truth requires the incredible vulnerability of feeling deeply into our most primordial selves. To then write well requires the supreme and often painful effort of teaching our brains new pathways, organizing our unruly and chthonic dreams into the straight line of language and communication.

If we fail from time to time in our intentionality with every piece and moment of our stories, it is little wonder. In the end, the only thing that matters is that we keep coming back to the deepest and most honest parts of what we are trying to create and share.

Why Intentional Storytelling Matters More Than Ever in an AI-Driven Content WorldIntentional storytelling has always mattered. But I write this post now because I feel it is more important than ever. Storytelling is the soul of culture, and perhaps as writers some of us have lost our souls a bit lately. The demands of content creation can make it easy to lose touch with the inner muse. Tools like AI can make this slide even more tempting. However, any assistance automated tools render us (in any aspect of life) can rob us of intentionality only insofar as we are out of touch with our own deep knowing and imagining.

How the Creative Landscape Is ChangingMany authors these days are asking themselves the hard questions. As the landscape of the artistic world—to say nothing of the world at large—changes so dizzyingly around us, it becomes ever more important for us to ask these questions. All humans are innately storytellers. But those of us who purport to shape and share our stories through the life-changing portals that are books and movies—perhaps bear a somewhat greater responsibility.

This is not a challenge to step away from the workings of modern life, but rather a challenge to experiment with every moment, to test and try and see and respond—to evolve when evolution is the truest and to stand fast when standing is truest—to allow ourselves the spontenaiety of each moment rather than the dogma of easy answers or quick fixes.

Why the Story Still Starts With YouIntentionality is not, nor ever will be, the easiest path for writers to take. But, truly, storytelling was never meant to be easy. As writers, it is our special sleight of hand that allows us to open portals into the depths of life under the guise of adventure and romance and mystery. There’s no such thing as “just” a story. That’s the trick. That’s the magic. But it only works when we, as storytellers and magicians, are in deep service to the integrity of the story itself.

Two Questions to Guide Every Writing DecisionAll you have to do is keep asking yourself these two questions:

Why? Why did I make this choice? Why did I put this in my story? Is it the easiest answer—or is it deep and true?How can I go deeper? How can I write something that is more honest, more real, more of my dreaming self?However you answer those questions—whether with certainty or with more questions—they are the beginning of a deeper relationship with your craft. Intentional storytelling isn’t a destination; it’s a continual practice of listening inward, trusting your creative instincts, and honoring the story that wants to be told through you. The path may not always be easy, but it is always worth walking one meaningful, intentional choice at a time.

In SummaryIntentional storytelling isn’t about rejecting tools or structure. It’s about using them with awareness, discernment, and, above all, honesty. In a time when it’s never been easier to churn out content that looks like a story, the real work of writing lies in remembering why we create in the first place. Every story worth telling begins not with trends or formulae, but with the deep, sometimes uncomfortable truths we carry inside ourselves.

To write with intention is to choose meaning over ease, depth over noise, and wholeness over quick results. It’s an act of quiet rebellion in a culture of speed and automation. We honor the sacred nature of story by treating it, not as a product to be packaged, but as a portal to something true, resonant, and lasting.

Key Takeaways on Intentional Storytelling:Intentional storytelling means making every creative choice with honesty, integrity, discipline, and courage.Tools like beat sheets and AI must be used with discernment and integrity.The rise of algorithm-driven content makes it more important than ever to return to the source: your own imagination, values, and story sense.Asking “Why?” and “How can I go deeper?” can reconnect you to authentic, resonant storytelling.Want More?If you’re feeling the pull to reconnect with your deeper creative self—to get out of your head and back into your story’s heart—my Archetypal Character Guided Meditations can help. I designed these immersive sessions to support you in finding the “dreamzone”: that quiet, intentional space where imagination flows freely, unshaped by algorithms or outside noise. In these times when technology offers us faster answers, my idea is for these meditations offer a return to deep, slow creativity. You can find them in my shop!

Go on the journey with your characters! Check out the Archetypal Character Guided Meditations.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What does intentional storytelling mean to you—and where in your own writing process do you sometimes feel most tempted to trade depth for ease? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Why Intentional Storytelling Matters in an Era of AI and Algorithm-Driven Content appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 30, 2025

The Secret to Writing Witty Characters (Without Trying So Hard)

There’s nothing like a sharp-tongued, quick-witted character to light up a scene—especially when the stakes are high or the tone is dark. From sarcastic sidekicks to roguish heroes, witty characters often steal the show. But when the humor feels forced or out of character, it can suck the life right out of a story. So why does some wit dazzle while other attempts fall painfully flat?

There’s nothing like a sharp-tongued, quick-witted character to light up a scene—especially when the stakes are high or the tone is dark. From sarcastic sidekicks to roguish heroes, witty characters often steal the show. But when the humor feels forced or out of character, it can suck the life right out of a story. So why does some wit dazzle while other attempts fall painfully flat?

In the last few years, there have been a rash of movies (mostly summer blockbusters) that try really hard to live up to the witty legacies of films such as Indiana Jones and the original Star Wars, only to fall sadly short.

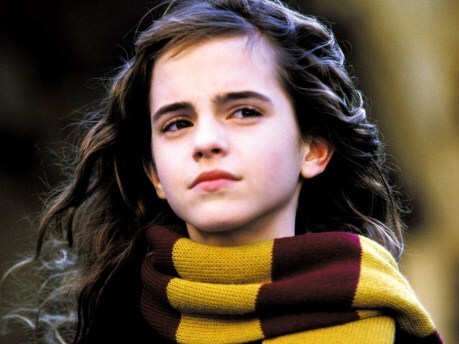

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

Why is this?

Often, it isn’t the jokes that are to blame. Words that might have been hilarious coming out of the mouth of Han Solo fall flat on their faces coming out of the mouths of other characters.

So what’s the difference?

In a nutshell: character.

The secret to pulling off a witty character is putting the emphasis not on the wit itself, but on the character.

As we’re planning or writing our stories, it’s easy to say, “You know, it would be fun to have a witty character. A wisecracking hero or a bumbling sidekick.” So we stick ‘em in. But our immediate problem with this decision is that we may be trying to force the humor, instead of allowing it to emerge organically from the character.

Humor grows all the more funny in context. And when that context is a fully developed personality, the humor is then able to offer not just a bigger laugh, but a deeper understanding of both the character and the plot.

If your characters are nothing more than smart mouths, readers will instantly perceive they’re cardboard cutouts, stuck in to garner a quick laugh. Some readers will forgive you for this, particularly if you do indeed happen to be able to write hilarious dialogue. But others may resent it as a gimmick and go looking for something that manages to combine both entertainment and depth.

When you craft characters who are fully realized—whose humor springs from their worldviews, flaws, and relationships—that’s when the wit lands with authenticity and impact. Humor can become more than a joke; it can be an insight. So next time you write a snappy one-liner, ask yourself: is it something this character would say, or something you wish someone would say? Instead of just sticking witty words in characters’ mouths, create complete personalities from whom the wit can flow realistically, organically, and engagingly

For more on writing authentic humor, see these posts:

How to Write Funny6 (More) Ways to Improve Your Book by Writing HumorThe Hilarious 2-Step Plan for Writing Humor in FictionHow to Write Funny Dialogue4 Ways to Write Meaningful ComedyWordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s your best advice for writing witty characters? Who is a favorite example of one done right in fiction? Tell me in the comments!The post The Secret to Writing Witty Characters (Without Trying So Hard) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 23, 2025

Need a Good Book Editor? Top Up-to-Date Recommendations

Where do I find a good book editor?

Where do I find a good book editor?

This is without doubt the question I receive most frequently from fellow writers. It’s a hard question to answer because, while finding an editor is easy, finding a good book editor is something else again.

I originally published this resource many years ago after reaching out to trusted writing experts for their recommendations of freelance book editors. I also encouraged readers to share their own suggestions in the comments. Today’s is the latest in a series of updates I’ve made to keep the post current—and I plan to continue revisiting it regularly to ensure the information stays helpful and relevant.

The following editors are in alphabetical order, with their names linked to their websites, so you can do further research to discover which is best suited to your needs. I’ll continue adding to the list whenever an appropriate new name comes to my attention (you can always find the list on the Start Here! page—accessible from the site’s top toolbar).

If you’ve personally worked with a good book editor, please feel free to add his or her name and URL in the comments. (If you’re an editor yourself and would like to be included, please ask one of your satisfied clients to nominate you.) The goal is to make this as useful a resource for everyone as possible. New names will be included in the list when I update it again in the future, so in the meantime be sure to check the comment section for more resources!

The Top Recommended Freelance Book EditorsMarlene AdelsteinServices: Developmental Editing, Publishing Consultations, Screenplay Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Commercial Fiction, Thriller, Mystery, Women’s Fiction, Literary Fiction, Historical Fiction, Memoir, and Screenplay.

Affordable EditorsServices: Line editing, proofreading, developmental editing, comic book editing.

Rates: 1¢–1.5¢ per word

Specialities: Science fiction, fantasy, slice of life, historical fiction, memoir, non-fiction.

Services: Developmental edit, editorial assessment, line editing, copyediting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Fiction, memoir, flash fiction, academic articles.

Services: Editing, consulting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Sally ApokedakServices: Editing, consulting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Augustine EditorialServices: Developmental editing, copyediting, proofreading, sensitivity reading, beta reading.

Rates: 1.3¢–2¢ per word.

Specialities: Tales set in immersive worlds, stories inspired by S.E. Asian folklore, and slow-burn romantic subplots.

Black Wolf Editorial ServicesServices: Content editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Bookaholics Author ServicesServices: Line editing and copyediting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: PG-13 material.

Breakout EditingServices: Content editing, copyediting, proofreading.

Rates: 1¢–4¢ per word.

Specialities: Fiction, non-fiction, children’s books, memoir, short stories.

Vicki BrewsterServices: Developmental editing, copyediting, content editing, manuscript evaluation, academic editing, indexing.

Rates: $.50–$1.20 per 100 words.

Specialities: Long-form fiction.

Grace BridgesServices: Line Editing, Developmental Editing, Proofreading.

Rates: $3–$30 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy.

Averill BuchananServices: Development Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Indexing.

Rates: £10–£45 per 1,000 words or £1,00–£2,000 per 100,000-word book.

Specialties: Fiction, especially for independent/self-publishing writers.

Burgeon Design and EditorialServices: Coaching.

Rates: $1,200–$6,500.

Specialities: Diversity.

Kelly ByrdServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Crime and Mystery, Thriller, Romance, Literary Fiction, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Memoir.

Sandra ByrdServices: Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Fiction, creative and narrative non-fiction, memoir, devotionals.

Dario CirielloServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: 1¢–4¢ per word.

Specialties: Science Fiction and Fantasy, Mystery and Crime, Romance, Literary Fiction.

Miranda DarrowServices: Developmental editing, coaching, book mapping, line editing, ghostwriting.

Rates: $.0175–$.0375 per word.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Rochelle DeansServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Query Editing, Academic Editing, Non-Fiction Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Plot structure.

Christy DistlerServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Critique.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified, but seems to lean toward Christian Fiction.

The Engaged EditorServices: Developmental editing, line editing, proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Joshua EssoeServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Genre Fiction, Fantasy, Science Fiction, Horror.

Elizabeth EvansServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Assessment, Proposal Crafting and Editing, Ghostwriting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Lorna FergussonServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Appraisals.

Rates: £275–£800+, depending on service and length of project.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Free ExpressionsServices: Comprehensive editing.

Rates: $425–$3,875 per 1,000–100,000 words.

Specialities: Fiction, picture books.

Annette M. IrbyServices: Critiquing, copyediting, proofreading, substantive editing.

Rates: $7–$9.50 per page.

Specialities: Christian fiction.

Don JanalServices: Coaching, developmental editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Non-fiction.

Jessi’s Profressional Book EditingServices: Developmental editing, line editing, copyediting, manuscript evaluation, coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Non-fiction, memoir, biography, historical fiction, literary fiction, thriller, mystery, science fiction, fantasy, Christian, young adult, children’s fiction, women’s fiction.

Caroline KaiserServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Line Editing, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Mystery, Thriller, Historical Fiction, Children’s Fiction, Young Adult, Fantasy, Science Fiction.

Nicole KlungleServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $2–$3 per standard page.

Specialties: History, Humor, Writing Instruction, Memoir, Literary Fiction, Paranormal Romance.

Mary KoleServices: Developmental Editing, Coaching, Outline Evaluation, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $249–$3,999.

Specialties: Children’s Literature.

Ann KroekerServices: Coaching.

Rates: $125–$1,025.

Specialties: Unspecified.

C.S. LakinServices: Developmental Editing, Proofreading, Coaching.

Rates: $8-$10 per page.

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction.

Dana LeeServices: Proofreading, Copy Editing, In-Depth Editing, Developmental Editing

Rates: 1.4¢–4¢ per word

Specialties: Romance, Mystery, Memoir, Non-Fiction, Spanish to English books

Kurt LipschutzServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Poetry

Katie McCoachServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy, Dystopian, Romance.

Leslie McKeeServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Romance.

Andrea MerrellServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Mentoring.

Rates: $30–$40 per hour.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Christian Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Victoria MixonServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Synopsis Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Novel, Short Story, Narrative Non-Fiction, Memoir.

Ginger MoranServices: Developmental Editing, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction.

Roz MorrisServices: Developmental Editing.

Rates: £70 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Fiction, Memoir, Non-Fiction

Robin PatchenServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $2–$7 per page.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Christian Fiction.

Lisa PoissoServices: Developmental editing, manuscript evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Arlene PrunklServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Indexing, Fact Checking.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Lori PumaServices: Coaching, manuscript evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Fiction.

Revision DivisionServices: Manuscript evaluation, beta reading, line editing, copyediting, proofreading, coaching, outline evaluation, blurb revision.

Rates: 1.5¢–3¢ per word.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Bryan Thomas SchmidtServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Ghostwriting, Short Story Review.

Rates: 1¢–5¢ per word.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Jessica SnellServices: Proofreading, copyediting, developmental editing, ghostwriting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Romy SommerServices: Manuscript, appraisal, developmental editing, copy editing, query assistance.

Rates: 1.2¢–1.8¢ per word.

Specialities: Romance, women’s fiction, historical, cosy mysteries.

Jim ThomsenServices: Line editing, copyediting, proofreading, developmental editing, coverage editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Crystal WatanabeServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Whisler EditsServices: 1:1 Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Lara WillardServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Graphic Novels, Comics, Children’s Fiction, Picture Books, Young Adult.

Ben WolfServices: Developmental Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Word Haven EditorialServices: Manuscript evaluation, developmental editing, line editing, copy editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

The Write ProofreaderServices: Proofreading.

Rates: 2¢ per word.

Specialities: Unspecified.

The Writer’s HighServices: Development editing, line editing, manuscript evaluation, manuscript review, coaching.

Rates: 2.4¢–1.2¢ per word.

Specialities: Speculative fiction, historical fiction, mystery, literary, flash fiction, southern themes.

Linda YezakServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $3–$4 per page.

Specialties: Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Ginny YtrrupServices: Developmental Editing, Coaching.

Rates: 2.5¢–3.5¢ per word.

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Web Content, Devotional, Query or Cover Letter, Book Proposal, Fiction Synopsis.

***

In today’s market, getting feedback from a skilled editor is crucial—especially if you’re planning to publish independently. If you’ve yet to find a good book editor, start with the names here and get ready to transform your story!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever worked with a good book editor? Can you add to the recommendations here? Tell me in the comments!The post Need a Good Book Editor? Top Up-to-Date Recommendations appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 16, 2025

How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character (Part 2 of 2)

One of the most exciting challenges in storytelling is writing characters who grow over time—not just within a single story, but across several. Whether you’re working on a series or revisiting a familiar protagonist in a new standalone, the question inevitably arises: How do you create different character arcs for the same character without repeating yourself? How do you honor what’s come before while still offering readers something new? In many ways, this is where character development becomes the most rewarding—when you’re not just building a compelling arc, but an evolving journey.

One of the most exciting challenges in storytelling is writing characters who grow over time—not just within a single story, but across several. Whether you’re working on a series or revisiting a familiar protagonist in a new standalone, the question inevitably arises: How do you create different character arcs for the same character without repeating yourself? How do you honor what’s come before while still offering readers something new? In many ways, this is where character development becomes the most rewarding—when you’re not just building a compelling arc, but an evolving journey.

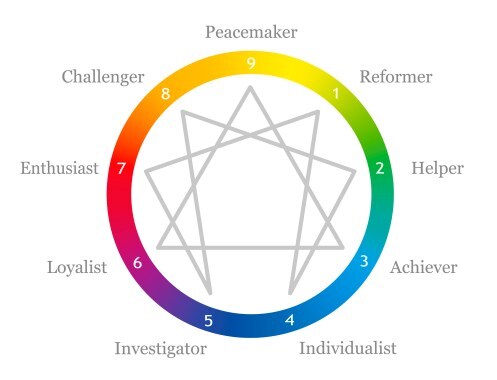

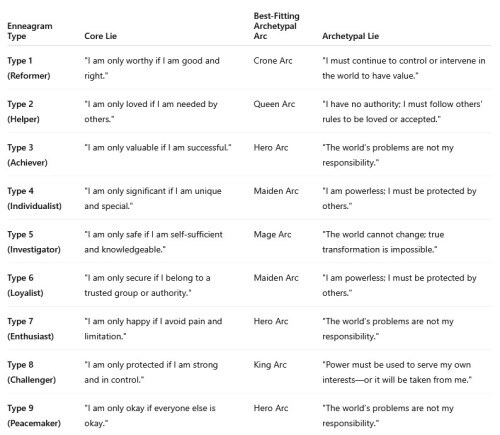

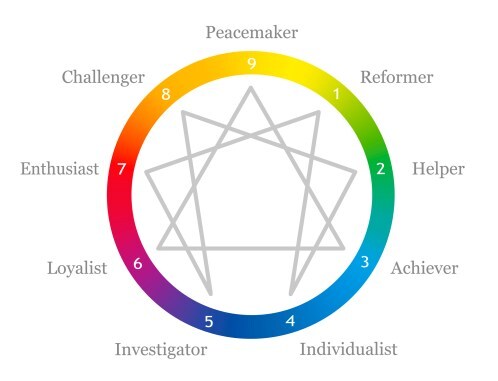

Last month, we did a bit of exploring about how to vary your character arcs by using the Enneagram system to identify different internal conflicts for characters with different personality types. We also talked about how pairing Enneagram insights with the archetypal Life Cycle can generate arcs that are not only distinct but also deeply resonant. However, as I mentioned last week in the first installment in this two-part series, the more I sat with that discussion, the more I realized there was another layer we hadn’t fully uncovered: what happens when you’re writing different character arcs for the same character?

The reader question that originally inspired these discussions (about how to use the Enneagram’s nine types to avoid repetitive Lies the Character Believes) sparked a larger reflection, not just on personality theory, but on long-term character development. If you’re writing a series or revisiting a character across multiple stories, you’ve likely asked yourself: How do I keep this arc feeling fresh? What else can this character learn, face, or become? The challenge isn’t just variety for its own sake. Rather, it’s about honoring the integrity of your characters while continuing to push their evolution in meaningful ways.

Last week, I offered six progressive systems you can use to help you chart long-term serial character arcs. This week, I want to dig into some general principles for approaching a character’s journey as an unfolding process that stretches beyond a single arc.

In This Article:How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character: Write Different ThemesUsing Robert McKee’s Thematic SquareExploring Different Archetypal Roles (Beyond the Life Cycle)Exploring Different Backstory GhostsHow to Deeply Develop a Single Theme: Listen to Your CharactersExploring Different Inner FacetsChanging Up the Supporting CastExploring Consequences From Previous BooksEmphasizing Different EmotionsHow to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character: Write Different ThemesLet’s start by exploring the two different approaches you might find yourself in when writing multiple books. The first is the possibility that you are writing totally different character arcs for each new story. This might be because you’re writing an entirely new cast of characters and don’t want to repeat yourself; or it could be because you’re writing an episodic series in which you want to explore new plots and arcs in each installment.

In either case, the simplest rule of thumb when wanting to write different character arcs for the same character is to focus on exploring different external aspects. Basically: write a different plot. A relatively good example of this is the MCU, which featured dozens of stories set in the same story world. The series often succeeded in creating varied character arcs by offering varied or unexpected plots.

>>Click here to read The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

For Example:

Tony Stark’s themes of escapist irresponsibility created very different themes from Peter Parker’s mistakes of teenage naivety.

Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Sony Pictures, Marvel Studios.

Here are a few more tools you can use to help you accomplish this variation.

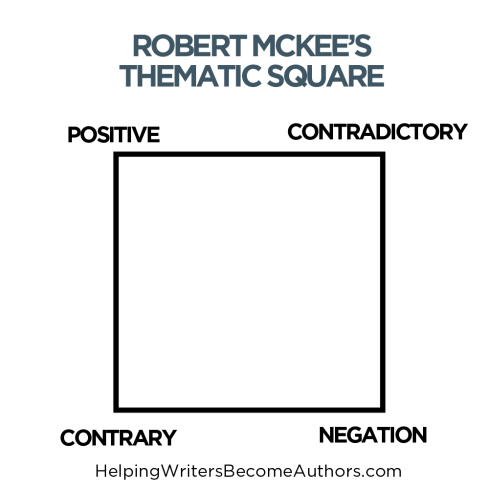

1. Robert McKee’s Thematic Square

Story by Robert McKee (affiliate link)

Plot is tied to character arc which is tied to theme. The Thematic Square is a storytelling tool created by Robert McKee in his book Story that helps writers explore theme from multiple angles by identifying not only the central value (e.g., love) and its opposite (e.g., hate), but also a contrary value (e.g., indifference) and its negation (e.g., self-hatred). In a single story, this can help you create layered moral complexity and richer character conflict. However, by exploring a different quadrant of the square in different stories, you can visit various thematic neighborhoods within the same world from story to story.

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

In addition to the continuity of the archetypal Life Cycle (which I mentioned last week and which you can read more about in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs), you can also focus on other ancillary archetypes. For example, exploring how your protagonist manifests the Trickster aspects of persoanlity in one story, the Rebel in another, and the Caregiver in still another can create opportunities for wildly different character arcs. Here’s a quick list of possibilities:

The Trickster – Brings chaos, humor, and unexpected change, often disrupting the status quo.The Ally – Supports others through trials as a loyal companion.The Shapeshifter – Changes form or allegiance, often creating doubt and intrigue.The Innocent – Seeks happiness and safety, often symbolizing purity or naiveté.The Orphan – Craves belonging and connection after experiencing loss or abandonment.The Rebel – Challenges norms and fights against injustice or oppression.The Sage – Pursues truth and knowledge, often as a detached observer.The Creator – Builds, innovates, or brings visions into reality.The Caregiver – Protects and nurtures others, often sacrificing personal needs.3. Explore Different Backstory GhostsFinally, as you seek to generate new and different character arcs throughout your series, remember that the catalyst for any character arc is the character’s backstory Ghost (sometimes called the wound). To explore different character arcs for the same character, look at different catalyzing events in your character’s past. This is a common (although often overdone) approach for TV series. When they finish one story arc and need to pursue a fresh angle, they will often reveal new and unexpected events in the characters’ pasts that link them to new conflicts.

For Example:

After wrapping up its initial storyline and associated character arcs in Season 5, Supernatural extended its run by introducing new backstory elements, notably the main characters’ reaction to secrets in their family’s past, including the fact that their mother had been a Hunter before meeting their father.

Supernatural (2005-2020), The CW.

How to Deeply Develop a Single Theme: Listen to Your CharactersWhat if you’re writing a series with an overarching plot that goes deep with a thematically cohesive character arc for your protagonist? In that case, how can you keep each story’s exploration of this overarching theme fresh and interesting, while also advancing the bigger arc?

The first thing to remember is that, in any story or series of stories, the thematic Truth a character learns (and therefore the successive Lies the Character Believes that must be overcome) exists along an ever-evolving spectrum. Therefore, even though the character may learn some version of an “ultimate” Truth by the story’s end, that Truth will be built of many smaller realizations and epiphanies along the way.

To progress that thematic throughline in a way that feels both realistic and also deep and nuanced, the most important trick is simply to listen to your characters. Really, this means listen to yourself. Listen to your own deep, innate knowing of how personal change occurs and what questions, roadblocks, sacrifices, and triumphs are likely to feel resonant along the way.

Here are a few tips and tricks for deepening your theme from book to book in a series.

1. Explore Different Inner FacetsIn any dramatic personal change (and therefore in any dramatic character arc) many different facets of the person will be affected. Depending on the length of your series, you have the opportunity to go deep with many different ways your characters are affected by the changes they are undergoing. For example, in one story you might explore how the change impacts the protagonist’s relationships, while in another you might explore how it impacts the protagonist’s experience of hope versus despair, while still another might delve into issues of ongoing personal integrity in the face of the changes the character is confronting.