K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 45

September 18, 2017

5 Tips for Organizing Subplots

Imagine you walk into a candy shop, but what you discover inside, instead of candy, is display after display of subplots. Enough to make any writer’s mouth water, right? Writers love the idea of subplots. They’re rich, juicy, complex, and full of opportunities for taking your story to the next level. But organizing subplots, or even just figuring out what your subplots are? That can sometimes be trickier.

I’m often asked about subplots, but it’s one of those subjects (like POV) that is bigger than just a simple answer. This is because subplots, when done right, are all but camouflaged within the larger story. Good subplots integrate with the main plot to the point they’re inextricable from the story’s bigger picture.

In short: you can’t master the art of organizing subplots without mastering the art of plotting itself.

For that, of course, you need story structure, character arc, theme, and all that fun junk. But today, let’s assume you’ve already packed your cart with your nourishing vegetables, which leaves you free to fulfill your sweet tooth by raiding Ye Olde Subplot Shoppe.

The Great Myth of Subplots

Confession time.

I actually don’t even like talking about subplots. Whenever someone asks me “how do I write subplots?”, it makes me incredibly squirmy. I don’t have a good simple answer (which is why it’s taken me ten years to write a full-blown post on the subject), for the simple reason that subplots are not a good way to think about story.

In fact, I recommend you stop thinking about subplots altogether. Instead, just think about plot.

If your subplot doesn’t work within the larger plot to the point that it’s inextricable from it, then it simply doesn’t work. If you find yourself thumbing through your manuscript and going, “Subplot, subplot, subplot!,” it may well be because the subplots are sticking out like speed bumps on the highway.

When I sit down to plot a novel, I never think in terms of subplots. My stories are usually huge, sprawling, complex, and peopled with big casts. Do they have subplots? Of course. But I don’t think of them that way. I don’t want subplots in my stories. I don’t want to hand readers a jumbled box full of really cool odds and ends. Instead, I want to give them one big cohesive plot that sparkles like a multi-faceted diamond.

Which is all to say: yes, today, we’re talking subplots, and, yes, I’m about to break this all down for you to show you what subplots are and how you can manage them. But the most important thing you can take away is that if it looks like a subplot, cut it.

The 3 Central Plotlines

Before we can talk about what a subplot is, we first have to talk about what it isn’t. By definition, a subplot is not the main plot, which means we first need to understand what constitutes the main plot.

In most fully-formed stories, there are three aspects to the main plot.

1. The External Conflict

When we talk about “plot,” this is probably the first thing to spring to mind. The external conflict is the physical aspect of the conflict. It revolves around a specific plot goal based on the Thing the Character Wants. The character is trying to do something or gain something—but an antagonistic force keeps putting obstacles in his way. The act of the protagonist overcoming those obstacles creates the forward momentum that drives the plot, all the way from his conception of the goal at the First Plot Point to the Climactic Moment, where he either definitively gains or loses his objective.

For example, in my portal fantasy sequel work-in-progress Dreambreaker, the protagonist Chris Redston (who previously, in Dreamlander—which you can grab for free right now—visited a parallel “dream” world as the only Gifted of his generation) has the main plot goal of stopping the cataclysms that are once again threatening to destroy the balance between worlds.

2. The Main Relationship

External conflict is great: it powers the story. But it’s rarely enough to truly engage readers on a deeper level. For that, you need the emotional stakes of a relationship. This could be a romance, a friendship, a business partnership, or a parent/child relationship. Whatever it is, it is directly connected to the main conflict. Either:

the relationship’s positive outcome hinges upon a positive outcome in the external conflict

the relationship creates the conflict

the conflict creates the relationship

Whatever the case, the protagonist must have a goal in this relationship, even if it is largely unspoken. Usually, it is simply for “the relationship to work out.”

For example, although Dreambreaker is about Chris saving the worlds, what it’s really about is Chris’s ongoing and uncertain relationship with Allara Katadin, Queen of Lael. Yes, he wants to end the danger to everyone, but on a more personal level, what he really wants is just to be with her in a healthy and permanent relationship.

3. The Internal Conflict

Both of the above are external manifestations of the story’s theme, which plays out within the protagonist’s internal conflict. His character arc will be linked to his actions in the external conflict. The conflict between the Lie He Believes and the Truth that can set him free, between the Thing He Wants and the Thing He Needs—this is the true heart of your story.

Both of the above are external manifestations of the story’s theme, which plays out within the protagonist’s internal conflict. His character arc will be linked to his actions in the external conflict. The conflict between the Lie He Believes and the Truth that can set him free, between the Thing He Wants and the Thing He Needs—this is the true heart of your story.

Although the character arc can play a background role within a noisy story, it is never ancillary. The more integral it is to the external plot, the more powerful the story.

For example, in Dreambreaker, Chris has to deal with misconceptions about the nature of total sacrifice and what we’re “owed” by life—which directly feed into his actions in the external plot.

4 Types of Subplot

Now that you can see what subplots are not… what are they?

There are four primary categories of conflicts, which although integral to the story are still subordinate to the main conflicts mentioned above. Think of them in terms of supporting the main conflict. If they aren’t an integral beam within your structural house, they don’t belong.

1. Minor Character Relationships

Most of the complexity of subplots arises from the supporting cast. Technically, to create a solid storyform, you need only three types of character (protagonist, antagonist, relationship character), but most stories offer up much larger casts—and, along with them, more complexity in the plot—and, thus, subplots.

Your protagonist may be working through conflicts with more than one relationship character. Each of these relationship characters will, in turn, have their own goals within the external plot, and, optimally, their own internal conflicts as well.

For example, in Dreambreaker, Chris also has to interact with his doppelganger family in the dream world, all of whom have expectations for him, some of which conflict with his own goals.

2. Minor POV Characters

Your story may take these minor character relationships to the next level by giving any number of these characters POVs of their own. The moment you do this, you elevate these characters to the level of “mini-protagonists,” which means you will explore their external, internal, and relationship goals in almost as much depth as you do the protagonist’s.

The most important thing to keep in mind here is that, despite the popular mantra, these supporting characters are not the heroes of their stories—not really. Their narratives, however cursory or complete, must contribute to the protagonist’s in a foundational way.

For example, Dreambreaker introduces the POV of a new minor character, a street-wise Cherazim named Thorne, who is a relationship character for Chris while also pursuing his own goals in the plot and his own problems in the theme. His storyline runs largely outside of Chris’s—until the Climax, where the two directly impact each other.

3. Lower Levels of Antagonists

We’ve talked before about the varying levels of antagonism you can feature in your story. Every story will have a primary antagonistic force—the one directly opposing your protagonist’s main plot goal. But you can also feature smaller antagonists who interfere with your protagonist on his way up the mountain to face the Big Boss.

But, again, these antagonists can’t create detours for the protagonist. Instead, they must ultimately be stepping stones in that journey up the mountain.

For example, as epic fantasy, Dreambreaker is giving me the opportunity to explore just about every level of antagonism, all the way from world-ending stakes down to political rivals and personal betrayals.

4. Minor Antagonist Goals

Finally, in direct relation to the above, you can also focus on sidelong antagonists and their goals. These are characters who are not necessarily affiliated with the main antagonistic force, but who have their own agenda, which at some point is at cross-purposes to your protagonist’s. These characters don’t even have to be “bad”; they could just be frustrated allies who decide to take matters into their hands at the wrong moment.

For example, one of my favorite new characters in Dreambreaker is Allara’s uncle, Prince Justus Katadin, who has been imprisoned for treason for twenty years—and has some very definite ideas about payback.

5 Tips for Organizing Subplots

Now you know what subplots are and aren’t. So what do you do with them? How do you weave them into your story in a way that enhances rather than detracts? And if you’re writing a story as complex as, say, epic fantasy, how do you keep track of all those little devils?

Here are five ways.

1. Create Your Subplots, Pt. 1: What Are Your Minor Characters’ Goals?

Did you notice how every single one of the sections we talked about above revolved around somebody’s goal? Goal is the engine that drives conflict. Without it, there is nothing for the antagonistic force to oppose—and no story.

Just like plot itself, your subplots need to originate from someone’s overpowering desire.

Examine your supporting characters. Make a list of their names, and beside each name, write down what this character wants in this story. Some of the wants will be evident, some won’t. But don’t stop until you’ve brainstormed a goal for each character. Whether or not these goals become prominent in the main story, you will have instantly fleshed out your entire cast.

And if any of the characters’ goals turn out to have little to nothing to do with the main plot? Well then, you may just have found a character you can safely cut.

2. Create Your Subplots, Pt. 2: What Are Your Protagonist’s Minor Goals?

Even though your protagonist’s primary focus will be on gaining his main goal and defeating the main antagonistic force, he can also be the catalyst for subplots. Complex characters want more than one thing—or at least more than one facet of the same thing.

But be wary. The protagonist’s minor goals must ultimately tie into the execution of his main goal. It’s fine for Jane Eyre to want take care of Adele and want to figure out what creepiness is going on in Thornfield’s attic—while also wanting to figure out her relationship to Mr. Rochester. But it would not be fine if another subplot had her wanting to earn enough money to erect a mausoleum for her dead childhood friend Helen Burns.

But be wary. The protagonist’s minor goals must ultimately tie into the execution of his main goal. It’s fine for Jane Eyre to want take care of Adele and want to figure out what creepiness is going on in Thornfield’s attic—while also wanting to figure out her relationship to Mr. Rochester. But it would not be fine if another subplot had her wanting to earn enough money to erect a mausoleum for her dead childhood friend Helen Burns.

3. Evaluate Your Subplot’s Necessity: What’s Its Role in the Climax?

Not sure if a subplot is really necessary to your story? Just take a look at the Climax. The subplot must be one of the following:

1. Concluded in the Climax.

2. Important to creating the Climax.

3. Directly impacted by the Climax.

If not, it’s going to (at best) require a climax of its own, which (at best) detracts from your story’s structural integrity.

But it gets more complicated. It’s not enough for your subplots to be directly related to your external conflict. They must also tie into your story’s theme. Every subplot in your story should reflect upon your story’s main Lie/Truth in some way. If the main theme asks “what is sacrifice?,” then your subplots must either directly comment on this question, or at least explore related ideas, such as “conviction,” “selfishness,” or “treachery.”

4. List and Color Code Subplots

Again, I don’t necessarily recommend brainstorming subplots outside of brainstorming your plot. But as you learn more and more about your story’s big picture, you will be able to identify the smaller integers that have created it. You can break this down into a handy list, so you can identify all the different threads in your plot.

You may then want to take this one step further and create a color code for each item on your list. You can then use this color-coding system through your outline or manuscript to help you easily identify where each of these subplots shows up, how prevalent it is, and when and how it will be resolved.

5. Combine Subplots Into Main Plot Scenes

What’s our rule of thumb for the day?

That’s right: There are no subplots, just plots.

As such, your goal is to integrate your subplot ideas into your main plot so seamlessly they’re inextricable. Although you will probably need to create certain scenes that revolve entirely around subplot ideas, it’s best if you can weave them into your main plotline’s concerns as much as possible.

Let’s say your scene is focused on your protagonist pursuing his main plot goal in the external conflict. But present in the scene are several minor characters—and every one of them has goals of their own. These goals power subplots, which interact in this scene with the main plot. Suddenly, the subplots can’t exist without the main plot, and the main plot can’t exist without the subplots.

And just like magic: there are no subplots.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How are you organizing subplots in your work-in-progress? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/organizing-subplots.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 5 Tips for Organizing Subplots appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 8, 2017

5 Things You Can Read While I’m On Vacation

Whoops! I’m not here today. I’m off partying someplace exotic. Or… actually not. But I am enjoying a ten-day vacation while visiting family! While I’m gone, I hope you get lots of writing done. But if you want to take a break and read something, check out the following five links for inspiration and fun.

Whoops! I’m not here today. I’m off partying someplace exotic. Or… actually not. But I am enjoying a ten-day vacation while visiting family! While I’m gone, I hope you get lots of writing done. But if you want to take a break and read something, check out the following five links for inspiration and fun.

1. Read the Post I Link to More than Any Other

Find Out if Your Prologue Is Destroying Your Story’s Subtext

Take a look at how poor prologues sap stories, how no prologue can strengthen stories, and how to determine if your story is one of the exceptions.

2. Buy the Books I Recommend More Than Any Other (They’re Not What You Think)

Why these books? Because I get asked about POV probably more than any other topic. (You can find all my recommended writing books here.)

3. Listen to My New Favorite Writing Music

4. Read This Post I Wish I’d Written

Authentic Female Characters vs Gender-Swaps by Jo Eberhardt on Writer Unboxed

I’ve been mulling a post on this topic after watching Marvel’s Jennifer Jones (which, in my opinion, gets this very right for the most part). I may yet do a post on authentic female characters, but for now, just read this.

5. Read These Story Structure Database Analyses

Don’t forget, I usually update the Story Structure Database weekly. You can sign up for updates in the sidebar on the Database page.

I’ll be back on Monday the 18th with a new post. See you then!

The post 5 Things You Can Read While I’m On Vacation appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 4, 2017

Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 62: Head-Hopping POV

You know you’ve moved beyond recreational storytelling to serious writing the moment you discover you’re hopelessly confused about POV. Other than perhaps show vs. tell, no fundamental principle of fiction dogs writers more than creating a solid narrative—which often begins by understanding how to avoid head-hopping.

You know you’ve moved beyond recreational storytelling to serious writing the moment you discover you’re hopelessly confused about POV. Other than perhaps show vs. tell, no fundamental principle of fiction dogs writers more than creating a solid narrative—which often begins by understanding how to avoid head-hopping.

It happens to all of us: we energetically send our story out for early critiques, only to have it returned to us covered in terse notes about “head-hopping,” “inconsistent point of view,” and “out of POV.”

In the beginning, these just seem like some more of those weird writer codes that make no sense to the uninitiated (and which we have a Glossary for, BTW). So to get us started today, let’s take a look at what these terms mean, why they’re such bad mojo, and how you can correct them to create a stronger story.

What Is POV?

Actually, first, let’s talk about “what is POV?”

This, of course, refers to the point of view in which your story is told. Through whose eyes will readers view the story?

Usually, it will be the protagonist’s. Sometimes, it will be multiple characters’. Sometimes, it will even be an omniscient narrator who doesn’t actually feature in the story.

The issue is further complicated, in that you can also tell your story in a first-person POV (using the pronouns “I” and “me”) or a third-person POV (using the pronouns “he/she” and “him/her”).

I’ve discussed all of these options in more details in the following posts:

3rd-Person POV

1st-Person POV

Omniscient POV

Multiple POVs

For now, suffice it that POV must not be a random choice: indeed, it will be the “driver” that guides the entire journey of your story. As such, it must be consistent. And that’s where head-hopping becomes a problem.

What Is Head-Hopping?

This colorful term refers to uncontrolled narratives, in which the POV skips randomly from one character’s “head” to another.

For example:

Charlie gripped his leather-wrapped steering wheel as he evaluated the racetrack stretched out in front of him. He would have to overcome his horrible starting position. Lucy, at the head of the pack, chuckled to herself: she was poised to win! Meanwhile, Linus could feel the thump-thump-thump of his right rear tire starting to blow.

Whose POV are we in? Everyone’s and no one’s, right? The narrative jumps all over the place to peek into every available character’s head. The result is expansive, but also cluttered and perhaps even confusing.

Almost all authors start out defaulting to head-hopping. There are couple reasons for this.

One is that the author is all his characters. We see into everyone’s heads. We empathize with all of them—and, quite naturally, we want to share all our characters with all our readers all the time.

The second reason is that it seems so drastically limiting to keep a story in just one character’s POV. How can readers possibly understand what’s going on if they can’t see that the bad guy is thinking about betraying the hero right now in this moment?

Is it limiting? Yep.

Is it challenging to make sure readers get all the info they need when maybe the protagonist doesn’t know everything himself? Oh, yeah.

But that’s the whole point. The limitations of a good POV are what create its structure and streamline it into an experience that makes sense for readers.

The Problem With Head-Hopping

One of the reasons head-hopping is so difficult for authors to overcome is that it’s not always immediately obvious why it’s such a bad deal. When you’re reading a book with a well-done POV, the technique will be so smooth, you almost don’t realize what’s going on.

But an alert reader will always feel the effects of a poorly-executed POV. Not only is head-hopping often confusing in the moment (wait, whose head are we in now?), it’s also a sign the entire narrative—all the way down to the structural foundation of the plot—lacks focus.

A strong POV is all about narrowing the story’s focus to a red-hot point that tells readers this is what this story is about.

This is just as true in a story with an omniscient POV or multiple POVs. Even though both of these approaches widen their viewpoint beyond traditional single-POV narratives, they are still focused and purposeful. The POV has been carefully chosen to create a specific effect that brings the story to life in the most efficient way.

Head-hopping doesn’t do this. Head-hopping creates an undisciplined scattergun effect that whiplashes readers back and forth between characters—usually by means of very choppy transitions.

How to Avoid Head-Hopping in Your Story

Ultimately, learning how to overcome head-hopping isn’t actually about avoiding head-hopping at all. Rather, it’s about learning how to create and manage properly-constructed POVs. And POV is a vast topic (as you can see from the many posts I linked up above). There are many different approaches to POV, and which you choose to master depends on both your own preferences and the needs of your story. The requirements of a good deep third-person POV are very different from those of a well-done omniscient POV.

Your first step in learning to overcome head-hopping is to study the various types of POV and what makes them work when they’re well done.

Fundamentally, however, what you need to know is that avoiding head-hopping means you have to do two things:

1. Stay in one narrator’s head/POV per scene.

2. Keep the perspective and voice of each POV consistent.

For example:

Charlie gripped his leather-wrapped steering wheel as he evaluated the racetrack stretched out in front of him. He would have to overcome his horrible starting position. Lucy, at the head of the pack, would be difficult to beat, especially with those evil-looking spikes she’d somehow gotten away with putting on her wheel rims. Just in front of him, he heard the familiar thump-thump-thump of a tire about to blow. He scanned the cars and saw Linus’s green Chevy swerve. Good grief.

4 Ways to Optimize the Limitations of POV—Without Head-Hopping

I know, I know: If you aren’t allowed to head-hop, how can you possibly show readers what the other characters are doing and thinking? Fortunately, there are several great workarounds.

1. Don’t Worry About the Other Characters’ Thoughts

Yeah, I know that sounds hard at first, but staying out of certain characters’ heads is actually a tremendous opportunity for creating that magic ingredient of all good fiction: subtext. Plus, you might be surprised with how much you don’t have to tell readers for them to still get the point.

2. Include Multiple POVs

Remember, a multiple-POV narrative is not the same thing as head-hopping. In a multiple-POV narrative, you view the story through the eyes of several different characters—but only one at a time, one per scene. Instead of randomly switching from character to character in the same scene (or, worse, the same paragraph, as in our original example above), you consciously control the perspective from scene to scene, indicating the switch with a scene break or chapter break, so readers remain oriented in each POV.

3. Let the POV Character Infer the Other Characters’ Thoughts and Actions

You will also learn to rely on the inductive reasoning of your POV characters. Because you have limited the narrative to the powerful experience of allowing readers to discover the story alongside your narrator, that means readers get to learn things with this character. When he starts getting suspicious clues about another character, that’s when the story’s big picture unfolds for readers as well.

This is also true on the smaller level of character-on-character interplay. For example, if your POV character is engaged in a conversation with a non-POV character, you don’t have to jump to the other character’s POV in order to indicate what she is thinking or feeling. The POV character can read her body language—just as we read other people’s body language in real life–to infer the subtext beyond her words.

4. Utilize Eye-Witnesses to Inform POV Characters of Unseen Events

But what if there are important events your POV character wasn’t around to witness? No problem. You can utilize any number of tricks to keep readers informed. This might range from having another character who was present come visit your protagonist and tell him all about it. Or the protagonist might read about it in a letter, a newspaper article, or see it on TV. In certain stories, perhaps he might even have premonitions or dreams about it.

***

Although writing a story without head-hopping can initially feel limiting, it is actually an incredibly exciting challenge. Writing a cohesive, tight, focused narrative will create the foundation for an amazing story—one readers can trust to carry them securely and sensibly through your marvelous fictional world.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Have you ever struggled with head-hopping? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/mistake-62.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Most Common Writing Mistakes, Pt. 62: Head-Hopping POV appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 1, 2017

Why Doubt Is the Key to Flat Character Arcs

Flat Character Arcs create some of the most exciting and powerful stories. Most of the time, when people think of “character arc,” they’re likely to think of Positive Change Arcs, in which the protagonist himself undergoes an empowering personal change. Flat Arcs, by contrast, are about a protagonist who does not personally change, but who changes the world around him.

Flat Character Arcs create some of the most exciting and powerful stories. Most of the time, when people think of “character arc,” they’re likely to think of Positive Change Arcs, in which the protagonist himself undergoes an empowering personal change. Flat Arcs, by contrast, are about a protagonist who does not personally change, but who changes the world around him.

Remember, the fundamental principle of character arc is Lie vs. Truth.

In any type of positive story (i.e., Positive Change or Flat Arc—in contrast to Negative Change Arcs), the Lie will be dominant in the beginning, only to slowly and inexorably be overcome by the Truth. In a Positive-Change Arc, the protagonist himself will start out believing that Lie until he is taught by the events of the story to embrace the Truth.

Flat Arcs, however, are different. In a Flat Arc, the character starts out already in possession of the Truth—and then uses that Truth to bring positive change to the world around him.

As such, the Flat-Arc protagonist is a person who, on the specific level of the Truth, has things figured out. He’s the most with-it person in the story—and in danger of becoming one-dimensional and obnoxiously goody-goody.

The challenge of the Flat Arc is to tell a story about a protagonist who understands and claims a Truth, but who is still flawed, fluid, and interesting. The Flat-Arc character, unlike the Positive-Change Arc character, does not believe a damaging Lie. But he does have a Doubt.

How “the Doubt” Keeps Flat Character Arcs Vibrant and Relatable

Just because your Flat-Arc protagonist understands the story’s fundamental Truth doesn’t mean she will be 100% sure of that Truth or her own ability to live it. This fluidity in recognizing her own fallibility is what makes Flat-Arc protagonists endlessly compelling.

Like us, they believe in something. But also like us, they recognize they could be wrong. They could have been blinded by another Lie. They could have chosen the wrong Truth. And even if they did choose the right Truth, then maybe they won’t have the wisdom, strength, or conviction to live it.

In short, they have a Doubt—and it keeps them seeking throughout the story, even as the undeniable power of their conviction in the Truth transforms other characters around them.

For example, Wonder Woman‘s Diana Prince is a solid Flat-Arc character. From the beginning, she understands and embraces the Truth that “only love will truly save the world.” She uses that Truth to change the lives of soldier Steve Trevor and, ultimately, to end World War I.

And she’s pretty unshakable in that Truth—to the point that her blind faith allows for some of the story’s more humorous moments.

But if that’s all Diana Prince was, she would have been a dreadful character: one-dimensional good-goody at best, psychotically single-focused at worst.

That’s where Doubt comes in. For most of the story, Diana does not doubt her Truth, but does doubt her own ability to carry it out. And in the Third Act, when faced with the true enormity of the Lie, she is also given cause to doubt the Truth itself and waver in her devotion to it before reclaiming it and acting on it with even greater conviction in destroying Ares.

(Note, however, that her moment of Doubt after the Third Plot Point could have been better developed had that same Doubt been set up in the First Act, in addition to her Doubt about her own unworthiness. Because the story’s most important Doubt was not introduced until late the story, her comparatively brief moment of despair wasn’t undergirded or developed strongly enough to be as powerful as it might have been.)

>>Click here to read the Story Structure Database analysis of Wonder Woman.

How to Discover the Right Doubt for Your Flat Character Arcs

You must choose a thematically-pertinent Doubt for your Flat-Arc protagonist. Diana’s arc could have been stronger had it introduced earlier the Doubt that was most pertinent to her final confrontation with the Lie. Although your character can harbor multiple Doubts, the primary one should be directly related to the Truth: Is it really the Truth? Is it really worth fighting for?

Your character’s Doubt can range from being a niggling question to a full-on existential crisis. However, remember this is a Flat Arc. The character will not fundamentally change. He will believe the Truth in the beginning, and he will reaffirm that belief even more strongly in the end.

His possession of the Truth must be strong enough throughout the story to effectively impact the supporting characters and inspire them to recognize and reject the Lie. The protagonist’s Doubt can occasionally get in the supporting characters’ way, but it cannot become an insuperable obstacle.

Flat-Arc characters can be tricky to execute well, since they are often perceived as static. However, nothing could be father from the truth. Handled skillfully, Flat-Arc characters are amazingly vibrant and powerful personalities, not least because they are able to confront and conquer their own demons right alongside those the Lie has inflicted on the world around them.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Are you writing a Flat Character Arc? What Doubt will your protagonist experience in regard to the story’s Truth? Tell me in the comments!

The post Why Doubt Is the Key to Flat Character Arcs appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 28, 2017

7 Ways to Write Thematically-Pertinent Antagonists

Thematically-pertinent antagonists are the lynchpin that holds together any successful story. You can write delicious protagonists, snappy dialogue, riveting conflict, and deep themes—and still, your story can fail simply because the antagonist was taken for granted as a leering, two-dimensional bad guy.

Thematically-pertinent antagonists are the lynchpin that holds together any successful story. You can write delicious protagonists, snappy dialogue, riveting conflict, and deep themes—and still, your story can fail simply because the antagonist was taken for granted as a leering, two-dimensional bad guy.

We’ve talked before about how (somewhat non-intuitively) the character who provides the entire foundation for a successful story is not the protagonist, but rather the antagonist. Why is that? Because the antagonist is the only one capable of connecting the conflict to the theme.

Stories rise and fall on the cohesion of their thematic premises. If the theme doesn’t arc properly over the course of the story, if it doesn’t resonate deeply within the final confrontation in the Climax, if it doesn’t tie together the protagonist’s inner and outer journeys—then the story will, at best, be better as a sum of parts rather than a whole.

If you’re uncertain whether your theme and your plot are proper partners for each other—dancing in symmetry through every important structural moment, all the way to the grand burst of fireworks in the finale—then the first question to ask yourself is: What is the relationship between my protagonist and my antagonist?

Why Your Antagonist Must Be Connected to Your Protagonist

What happens in a story is always personal. Because the exterior conflict exists to help dramatize what the story is really about (aka, the protagonist’s personal character arc), it’s never random. (Indeed, even when the point of the story is that bad things sometimes happen randomly, for no obvious reason, that’s how the story begins, not how it ends—which means the antagonist’s intrusion into the protagonist’s life is very personal for the subsequent duration of the story’s conflict.)

Whether your antagonistic force is a faceless corporation, a serial killer, a bully, a family member, or just a nice little old lady who can’t remember to chain up her destructive dog—there must be a reason this force is throwing negative obstacles into the protagonist’s life.

If there is no reason—no obvious connection—then the story’s realism fades. Worst case scenario: the antagonistic force’s lack of connection (and thus the main conflict’s lack of connection) to the theme creates an utterly fragmented and emotionally-unconvincing final confrontation in the Climax.

I see this quite a bit in romances. The main part of the story is solid: it’s about a relationship, which means the two figures in the relationship are, in fact, one another’s antagonists—creating and resolving each other’s obstacles within the mutual goal of a successful relationship. So far, so good. In fact, this fundamental aspect of romances is an excellent example of how to inextricably unite the antagonist, the conflict, and the theme.

But, often, the author will feel the need to up the ante by throwing in a suspenseful subplot, in which a minor antagonist threatens one of the main characters. This antagonist is usually off-screen for 90% of the book, rarely if ever interacts with the protagonists, and has little to no connection to the thematic premise. Rather, he exists solely to provide an exciting final obstacle for the characters to overcome. No problem there, either, except this final obstacle—which should be the most pertinent and personal of the entire story—ends up being the most distanced from the underlying thematic story.

7 Categories of Thematically-Pertinent Antagonists

Today, we’re going to explore seven possible ways you can connect your antagonist to your protagonist—and thus, your main conflict—in a thematically-pertinent way. This list probably isn’t exhaustive: I collected it after researching some of my favorite stories and studying what made the antagonist-protagonist relationship so compelling.

After reading through the list, think about some of your favorite stories. Do the antagonists fit into the following categories? If not, drill down deeper to figure out what connects protagonist/antagonist/theme in a watertight triangle of emotionally-compelling logic.

1. Protagonist and Antagonist “Positively” Connected

When you think of a “meaningful connection” between protagonist and antagonist, the first thing to come to mind might well be the heartrending premise of friend vs. friend. This is one of my favorite types of antagonist-driven themes, thanks to its inherent emotional quality.

Great conflicts are based around hard choices—preferably leading to obvious lose-lose situations. These are rife in stories in which both the protagonist and the antagonist are forced to choose between someone they love and their own goals and/or principles. These stories prompt excellent moral questions, along the lines of: What makes it okay to betray a friend?

This category can also include relationships that aren’t necessarily “positive” on a personal level, but which still bind the protagonist and antagonist in a way generally looked upon as a positive alliance. This applies particularly to family members, even when they dislike each other. Cinderella and her stepmother are a good example. They never like each other, but because of their forced familial bond, Cinderella, at least, feels bound to respect the traditional nature of their relationship—which neatly complicates the thematic argument.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

Friends Steve Rogers and Bucky Barnes (Captain America: The Winter Soldier), friends Steve Rogers and Tony Stark (Captain America: Civil War), adopted son/father Matthew Garth and Tom Dunson (Red River), brothers Brendan Conlon and Tommy Conlon (Warrior).

2. Protagonist Negatively Connected to Antagonist

Many stories open with the protagonist and antagonist oblivious to each other until the moment their goals bring them into conflict. In these moments (either the Inciting Event or the First Plot Point), something will happen that will be so dramatic and life-changing (even if on a comparatively small level in some stories) that these characters cannot walk away from each other after this.

Because the antagonist is traditionally the “bad” guy, it’s common for him to be responsible for negatively impacting the protagonist in a way that binds the protagonist to him. In short, the antagonist does the protagonist wrong.

This action can span the gamut from the antagonist’s lying about the protagonist, winning a job away from him, betraying him on a personal level (as in Warrior, in which younger brother Tommy feels his older brother chose their alcoholic father over him and their mother), all the way to something truly tragic, such as an assault upon the protagonist (as when psychotic bandit Liberty Valance robs, beats, and leaves for dead Jimmy Stewart’s idealistic lawyer) or an assault upon a loved one (hello, Death Wish and every revenge story ever after).

The point is that the protagonist cannot walk away. The antagonist has changed his life in a negative way. The protagonist may start out the Second Act just wanting to try to put things back to rights, but eventually the story will force him to face down the antagonist in what has now become a very personal fight—even if it’s actually about something bigger. The awesome thing about this approach is that it forces the interior goal to extrovert into an exterior goal—neatly tying everything together.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

William Tavington murders Benjamin Martin’s son in the midst of the greater conflict of the American Revolution (The Patriot), Liberty Valance leaves Rafe Stoddard for dead in the midst of the greater conflict for western statehood (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), wrongful King Vortigen kills off rightful King Arthur’s parents and friends in the midst of the greater conflict for peace in Camelot (King Arthur: Legend of the Sword).

3. Antagonist Negatively Connected to the Protagonist

This can also work the other way around: instead of the protagonist being wounded and furious with the antagonist, it’s the antagonist who sees himself as the damaged party and pursues the protagonist singlemindedly.

The key difference is that the protagonist is often (although not always) oblivious to the antagonist’s obsession with him. He is either unaware of what he did to upset the antagonist, or he views it as a positive thing, or he is unwittingly the key player in a larger conflict of which he is as yet unaware (as is often the case when the conflict is generational, as in King Arthur).

This can also work both ways, since any and all of the categories listed here can overlap. Almost always, there will be a chain of cause and effect. Maybe the antagonist gets hurt first, but he will quickly lash out and make it personal for the protagonist as well.

This antagonistic category lends itself well to mystery and suspense, since the protagonist will sometimes have to discover whatever it is he did to upset the antagonist and make himself central to this particular conflict. “Chosen ones” often qualify.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

Tony Stark vs. [pretty much all of his opponents], as a result of his general oblivion about the damage he leaves in his wake; Rafe Stoddard vs. Liberty Valance, as a result of Rafe’s trying to lawfully oppose Liberty’s reign of terror in the territory; Arthur vs. Vortigen, as a result of Arthur’s bloodline as “born king” threatening Vortigen’s reign; Po vs. Tai-Lung, as the result of Tai-Lung’s envy of Po’s status as Dragon Warrior (Kung-Fu Panda).

4. Antagonist Is a Mirror for the Protagonist

Not all stories will feature protagonist-antagonist relationships in which the characters actually know each other. This obviously creates a huge emotional vacuum within the story. How can the conflict be personal when the relationship isn’t? How can the Climax still have deep thematic meaning?

In many stories with “Big Bads,” it is logistically impossible to even put the protagonist and the antagonist in the same room with other for most of the story. But you can still keep their relationship front and center by allowing the antagonist to be a “mirror” for the protagonist. When the protagonist is able to see herself even in this faraway bad guy, it prompts the opportunity for the deep thematic grist of existential questions.

The protagonist gets to ask herself: Why am fighting this person? How am I any different or any better? If this person is so much like me, then mightn’t we even be friends instead of enemies?

The more similarities you can draw between protagonist and antagonist—personality, methods, goals, backstory, interests, etc.—the more opportunities you will create to explore the exterior conflict from within subtext of the protagonist’s own interior journey.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

Tony Stark and Ivan Vanko share similar backstories regarding their inventor fathers and similar abilities, among other things (Iron Man 2); Steve Rogers and Johann Schmidt share similar experiences with taking the Super-Soldier Serum (Captain America: The First Avenger); Jason Bourne shares an identical past with all the Treadstone agents sent after him (the Bourne trilogy); Captain Jack Aubrey duels it out with a French captain, who “fights like you, Jack” (Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World); Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy share many personality traits (Pride & Prejudice); George Bailey and Old Man Potter share business savvy, ambition, and a disdain for Bedford Falls (It’s a Wonderful Life); Arthur and Vortigen share a bloodline and similarly ruthless ambition.

5. Protagonist and Antagonist Oppose Each Other Ideologically

The protagonist and the antagonist won’t always be opposing each other due to personal goals or injuries. Sometimes, the battle will be about something greater: ideological ideas. The good guy believes in what’s “right,” and the bad guy believes in what’s “wrong”—and never the twain shall meet.

Most stories come down to this at one point or another in the conflict, even if the theme is just about school kids standing up for themselves against bullies. Stories about even larger issues, such as war and social injustice, are often based entirely around this.

It’s important to note, however, that ideological opposition isn’t enough to float a conflict. As you may have noted, ideological opposition implies no sort of connection between characters whatsoever. For the final conflict between these ideologies to carry emotional weight in the finale, the antagonistic force needs to be bound to the protagonist in an additional way, via one of the previous categories.

This is where Wonder Woman faltered: Diana’s final confrontation with arch-enemy Ares is the weakest section of the story, due primarily to the fact that it is entirely ideological. Diana has no personal connection to Ares. Were it not for her commitment to her beliefs, she would be able to simply walk away from him and the war, with no personal consequences. At best, this contributes to simplistic plots and themes.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

Chris Adams’s “That’s just the kind of promise you’ve got to keep” vs. Calvera’s “Why did you come back? A man like you, a place like this” (The Magnificent Seven); Rafe Stoddard’s law and order vs. Liberty Valance’s rule by violence; Lady Eboshi’s disregard for the balance of nature vs. Ashitaki’s respect for it (Princess Mononoke).

6. Antagonist Is Non-Human Obstacle to Protagonist’s Goal

Most stories will be better off putting a human face to even a larger impersonal antagonist—which is why most war movies present a specific soldier as the “enemy” rather than just the entire opposing army. However, it’s true not all stories will offer a human antagonist.

In these instances, how can you “connect” the protagonist to the antagonistic force in a meaningful way?

By nature, these stories simply are more emotionally distant. However, remember the antagonistic force is, ultimately, nothing more or less than an obstacle between the protagonist and his goal. As such, anything standing in the way of the protagonist’s goal becomes, by its very nature, personal. Bottom line: the only conflict that matters is that which directly impacts the character’s main throughline in pursuing that personal goal.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

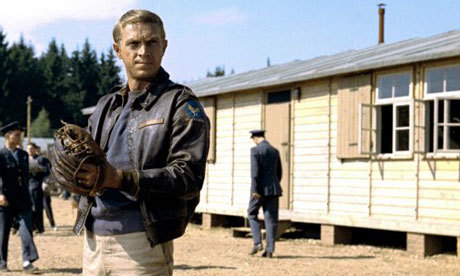

The British and American POWs vs. the multitude of obstacles between them and their goal of escaping Germany and returning home (The Great Escape), the Jaeger pilots vs. the animalistic alien kaiju monsters intent on destroying humanity (Pacific Rim), Captain Jack Aubrey vs. any number of French (et al.) naval and army officers opposing England in the Napoleonic wars (Aubrey/Maturin series), the snow-less winter keeping skiers away from the failing Vermont lodge owned by the protagonists’ beloved former commanding officer (White Christmas), the dinosaurs out to eat everyone (Jurassic Park).

7. Protagonist As Own Antagonist

Even in stories that feature all six of the above types of thematically-pertinent antagonists, there is no antagonist more personal than oneself. Every thematically-deep story is a story of the protagonist’s inner conflict: who is he? what does he believe? how will he survive? what will he do?

By all means, start plotting your story with the antagonist—but start with that inner antagonist first. Once you know what inner demons your protagonist is battling, you can look for the right exterior antagonist to symbolize, dramatize, and catalyze that all-important interior battle.

This is the heart of great climactic encounters—when the protagonist’s conflict against himself aligns with his conflict against an exterior opponent. One way or another, he will come to the realization that defeating the exterior antagonist is easy in comparison to the inner foe he’s been battling. In realizing that, he harmonizes the two conflicts, and in ending one is essentially ending both. And just like that: powerful thematic resonance within the conflict.

Examples (Click on the Links for Structural Breakdowns):

George Bailey (It’s a Wonderful Life), Russ Duritz in (The Kid), Walter in (Secondhand Lions), Roger Maris in 61.

***

Don’t create a story about a protagonist. Instead, create a story about a protagonist and an antagonist—and the connection between them. The result will be a realistic conflict that flows, and a plot and theme that are bound integrally and powerfully at every important point in your story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How have you created thematically-pertinent antagonists in your story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/thematically-pertinent-antagonists.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 7 Ways to Write Thematically-Pertinent Antagonists appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 25, 2017

How to Create Meaningful Obstacles Via Conflict

Conflict is one of those terms frequently used as a catch-all for compelling storytelling, when it’s really just one aspect of what makes a strong story. We use it even though we really mean the scene needs a clearer goal, or more tension, or a better character arc, but saying “this scene needs more conflict” sums it up in a convenient—if confusing—way.

Conflict is one of those terms frequently used as a catch-all for compelling storytelling, when it’s really just one aspect of what makes a strong story. We use it even though we really mean the scene needs a clearer goal, or more tension, or a better character arc, but saying “this scene needs more conflict” sums it up in a convenient—if confusing—way.

It doesn’t help that so much advice out there (mine included) describes conflict as “the obstacle preventing the protagonist from achieving the goal.” This is technically true, but also false. The obstacles in the way of the protagonist’s goal are the challenges that need to be faced, and usually, there is conflict associated with overcoming or circumventing those obstacles, but an obstacle in the way isn’t all conflict is.

3 Examples of Why “Stuff Happening” Doesn’t Equal Meaningful Conflict

This misconception can lead to stories that look conflict-packed, but actually bore readers.

To be fair, there’s nothing inherently wrong with random obstacles, and they can make for some fun storytelling. Overcoming a random obstacle can show an aspect of the character or reveal a skill. Sometimes a scene just needs “something in the way” to achieve the author’s goal for that scene, and that’s okay.

The problem occurs when the majority of the conflict in a story is a series of random obstacles that do nothing but delay the time it takes for the protagonist to reach and resolve the problem of the novel. They serve no purpose and could be swapped out or deleted, and the story would unfold pretty much the same.

For Example:

Imagine the fantasy protagonist who must navigate the desolate wasteland to reach an oracle with answers she needs. While the wasteland could contain conflicts, if nothing has changed for the protagonist between entering the wasteland and leaving the wasteland, she likely faced no conflicts.

Picture the romance protagonists who always have “something come up” to keep them from kissing or getting together. While this might work once, or even twice if done with skill, the “near miss” is a contrived obstacle that doesn’t create actual conflict, because nothing is truly keeping the two lovers apart.

Consider the mystery protagonist who speaks with multiple witnesses and no one has any information to move the plot along. While speaking to people of interest is a critical part of a mystery, if nothing is ever gleaned, suggested, or learned from those conversations, they were only a delaying tactic and did nothing to create or affect the conflict. Speaking to one witness or twelve doesn’t change anything about the story or character.

It all sounds like conflict—overcoming the thing keeping the protagonist from achieving the goal—but it’s not.

What Meaningful Conflict Does Not Look Like

Let’s explore this further with the fantasy wasteland example:

Getting through dangerous terrain is a common trope for the genre. The protagonist’s goal (to reach the oracle) is on the other side of a set of trials and obstacles, and odds are getting through that wasteland will be quite the adventure for the protagonist.

Say the protagonist’s first obstacle is that she must find water or she’ll die. It’s not easy, but she figures out how to get water.

She travels on until wasteland monsters attack. Again, it’s tough, but she prepared for this and fights them off and keeps going.

Then there’s a storm of some type, forcing her to face off against the elements. She hunkers down, waits it out, and emerges when it’s over.

Finally, she reaches a chasm she must cross. It takes effort, and she nearly falls and dies several times, but she gets across.

At long last, she reaches the end and consults the oracle to get her answers.

At first glance, this sounds like a story with tons of conflict, and it’s possible to give all of these obstacles real conflict, but look closer…

2 Questions to Ask About Your Conflict

1. Do Any of These Challenges Intentionally Try to Stop the Protagonist From Reaching the Goal?

Nothing about the obstacles in the above example shows anyone actively trying to prevent the protagonist from reaching the oracle. Any random person entering the wasteland would have encountered the same issues she did.

And even though these obstacles seemed hard to overcome, were they really? Was the reader ever in doubt the protagonist would overcome them? A good conflict would have come from an obstacle that created a personal challenge to overcome, one that mattered to the protagonist.

2. Does the Protagonist Make Choices That Change Her View or Force Her to Struggle to Find the Right Path?

Nothing about the obstacles in our example challenges the protagonist mentally or emotionally. No hard choices were made to find water or beat a monster. There was nothing really at stake and no soul searching to choose the right path to the oracle. She just dealt with whatever appeared in front of her.

The segment would have been stronger if overcoming these obstacles required internal struggles, or caused a change in viewpoint or belief that made facing them matter to the protagonist’s character or growth.

From a larger story standpoint, the external challenges (physical problems) didn’t do anything to affect the plot or character. Similarly, the internal challenges (mental or emotional problems) didn’t exist. This series of obstacles were just things in the way. They provided no conflict to the goal, even if they did provide obstacles to the goal. Reaching the oracle wasn’t hard, because no matter how difficult those obstacles might have seemed, they caused no struggle or challenge to the protagonist on either a physical or emotional level.

And that’s the difference between conflicts and “something in the way” obstacles.

Remove any of these obstacles and the scene of the protagonist consulting the oracle unfolds exactly the same, because the obstacles did nothing but kill time until the scene could occur.

Conflicts involve struggle. They’re about facing a challenge and having to decide what to do about it—and there are consequences to making the wrong choice and losing (and, remember, death isn’t a real consequence, as protagonists rarely die). If nothing about the challenge is physically, mentally, or emotionally challenging, it’s merely an obstacle and not a conflict.

Conflict encompasses such a wide range that it’s easy to misunderstand. To avoid the common conflict pitfalls, all you have to do is remember it’s how both the external and internal aspects of the plot work together to challenge the protagonist.

Looking for more tips on creating conflict? Check out my latest book

Understanding Conflict (And What It

Really

Means

), an in-depth guide to how to use conflict in your fiction.

Looking for more tips on creating conflict? Check out my latest book

Understanding Conflict (And What It

Really

Means

), an in-depth guide to how to use conflict in your fiction.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How do you feel about conflicts that don’t provide meaningful obstacles to the protagonist? Tell me in the comments!

The post How to Create Meaningful Obstacles Via Conflict appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 21, 2017

4 Questions You Should Never Ask About Your Book

“No such thing as a stupid question.”

“No such thing as a stupid question.”

Sounds good, right? Sounds like, “Yay! Let’s be inquisitive and creative and learn stuff!” But here’s the problem: there is such a thing as a stupid question, and the bigger problem is that stupid questions are not just missed opportunities, they are actually counter-productive to curiosity, creativity, and learning.

As any writer can tell you, the writing life is full of questions:

“Why doesn’t anybody like my protagonist?”

“How can I ever find time to write?”

“Why is this so hard???”

These are all good questions. They’re specific, and they’re focused on the problem—which means they’re ultimately focused on the solution. But not all questions are created equal, and if you’re not disciplining yourself to ask good questions, your best-case outcome is a long, circuitous bout of flailing before, if you’re lucky, you finally find a suitable answer.

Why Asking Good Questions Is a Crucial Skill for Writers

Writing, perhaps more than any other art form, is about harnessing creativity with logic. As historian David McCullough says:

Writing is thinking clearly. To write well is to think clearly. That’s why it’s so hard.

This starts and ends with the ability to identify challenges and frame appropriate questions about them. Mystery author Sue Grafton once said something that has become the paradigm for my entire approach to writing:

If you know the question, you know the answer.

In short, good writing is not about finding the right answer. It’s about finding the right question.

Mind-blowing, right?

But it’s not as easy as it sounds. Finding the right question is first and foremost about developing the logical skills to strip away all the wrong questions.

The Difference Between a Good Question and a Bad Question

So what’s the difference? What makes one question “good” and another “bad” to the point of uselessness?

I receive a lot of questions from writers. Most are pretty simple; most are the same questions I see and answer over and over again. Some are so brilliant, they help me see answers I hadn’t previously realized I was looking for. Others, however, demonstrate that the writer’s primary obstacle is not whatever it is they’re asking me about, but rather a failure to look deeper into themselves and do the hard logical work of figuring out what they’re really asking. Because if they did that, half the time, they wouldn’t even need to ask.

The common pattern in good vs. bad questions is simple:

Good questions: specific.

Bad questions: vague.

This goes for just about anything in the writing life, whether it’s plot-specific questions (“Why isn’t my story working?”) or personal questions (“Why am I blocked?”). If you’re struggling to find an answer, it’s probably because you haven’t yet made the question specific enough.

Instead of knowing your story isn’t working and just leaving it that, you have to drill down to find the question at the crux of the issue: “Why is my Second Pinch Point missing?” or “Why is the Big Bad acting like this for no reason?”

Suddenly, boom. The answer (or at least, the road to the answer) is staring you right in the face.

4 Questions You Definitely Shouldn’t Be Asking

Today, I want to go over four of the most common “bad” questions I receive. I can’t give you the answer to any of them. But I can show you how to ask better questions that will help you find your own answers.

1. Don’t Ask: Will You Help Me Write a Book?

My Reaction:

Well, yes. I mean, no. I mean, of course, I’ll help you write a book: here’s the link to my website!

The Problem:

Here’s the thing. You don’t need help to write a book.

*cue panic*

No, really. Writing is a solitary endeavor. Writing is nothing but hard work down in the trenches of your soul. I can’t follow you there. You don’t need me holding your hand down there. Will I cheer you on? You bet. But I can’t help you write a book. No one can. Only you can do the hard work of reading, writing, learning, and thinking. Frankly, I can give you all the answers there are, but they won’t mean a thing until you’re ready to start asking the right leading questions.

Questions to Ask Yourself Instead:

What is my specific roadblock? Why am I not yet writing a book? What knowledge and/or tools do I need to make that first step forward? What is the best entry point for writing that first word? What am I afraid of? What is holding me back? How did other writers before me learn how to write a book?

Questions It’s Okay to Ask Other Authors:

At this point, after asking yourself all the above questions, you should have plenty of stuff to work on for the time being before you require feedback from others. Although it can sometimes be worthwhile to ask other authors how they started writing their first book, be real about whether you’re just chatting things up as a procrastination technique from the load of work now in front of you.

You won’t have a legitimate question for other writers until you’ve dug down so deep into the process you’re getting to questions like: “Which is better for my story: omniscient or third-person POV?”

2. Don’t Ask: How Do I Write a Book?

My Reaction:

Uhhh, sure, but… where to start…? You just, you know, start typing. Oh, wait, but then there’s, like, story structure and outlining, and theme and character building. You could maybe take a workshop or two. Or, you know what, here: [link to website]

The Problem:

This question wins the award for Most Vague. Basically, all this question does is establish that you want to write a book. That’s totally awesomesauce. But it’s not a good entry point to the actual process. Honestly, I’m still learning how to write a book. Basically, you just jump in and start swimming. Start typing, start studying, start thinking.

Questions to Ask Yourself Instead:

What do I already know about writing a book? What holes does that yet leave, leading me to specific areas in which I know I can start studying? How do my favorite authors put words together in a way that makes magic on the page? How can I mimic that?

Questions It’s Okay to Ask Other Authors:

What was your first breakthrough insight as an author? What was the biggest mistake you made in writing your first book? What resources have you found most helpful in improving your writing?

Your goal should not be to get another author to lay out the entire path for you (they can’t, if only because their path is going to be totally different from yours), but rather to gain insights from the specific steps they took to get that first book written.

3. Don’t Ask: Where Do I Start?

My Reaction:

[image error]

Why, you begin at the beginning, of course.

The Problem:

Although similar to the above question, this is the better question since it’s ever so slightly less vague. At least it’s acknowledging the need for an obvious starting point! However, it still demonstrates the disadvantage authors are at when they fail to dig down for specifics.

As already acknowledged, this question has a very obvious answer. But if “start at the beginning” is not the answer you’re looking for (and no one ever is), then you already have a leg up on knowing you need to ask a better question to find the answer you’re really needing.

Questions to Ask Yourself Instead:

Am I ready to just start typing this novel? Do I feel I’m lacking some crucial understanding about either writing or storytelling? What information do I need to find before I can move forward? Do I need to do some research? Do I need to understand more about the story itself before I start writing? Should I outline before writing the first draft? What’s the best way to outline a story?

Questions It’s Okay to Ask Other Authors:

Remember, you’re not looking for other authors to tell you how to write (because, really, when you’re asking that, you’re mostly just wanting them to hold your hand through the process—or maybe even do all the hardest work for you). Instead, you’re looking for insights you can learn from their own way of doing things.

To that end, ask questions such as: What is your first step in your writing process when you start a new book? Do you outline? Why or why not? What are some key elements for a good opening chapter? What are some pitfalls to be aware of in beginning a new story?

4. Don’t Ask: What Should I Write About?

My Reaction:

*opens mouth* [confused face] *closes mouth* Why, would you even…? *clears throat* Dear Person, I am about to save you a life of misery and wrist pain: If you can not be a writer, then don’t.

The Problem:

Okay, for starters, I really, really don’t get this one. If you don’t have something to write about, why do you want to write? Writing, like all of art, needs to come bursting out of you like a volcano. We write because, first and foremost, we have something to say—or even, perhaps, to discover what it is we have to say.

If you don’t know what to write about, then wait until you do. Or, if what you’re really asking is, “What should I write about that will sell a million copies?”—then stop right there and gut-check yourself. First of all, I cannot tell you what story will sell a million copies (after all, if I knew that, I’d write it myself), and second, you’re not writing for the numbers, remember, you’re writing for the words and your own love of them.

Questions to Ask Yourself Instead:

What kind of story do I want to write? Do I really, really, really want to write it? Can I not write it? Why do I want to be a writer anyway? How can I take this little kernel of a good idea and make it better? What kind of story do I wish my favorite author would write for me?

Questions It’s Okay to Ask Other Authors:

Honestly, on this one I have to say: just don’t. You could maybe ask for feedback on whether someone thinks an idea is a good one. But, personally, I wouldn’t go there. If an idea is good, you just know it. You love it. You can’t stay away from it. Your own passion is what will drive the project forward and turn it into something great. You don’t need another writer’s permission to do that—and why risk their cold water if, in their own subjective opinion, it doesn’t do it for them?

***

Asking worthwhile questions about your writing is ultimately about taking responsibility for your writing. Vague questions are very often lazy questions. Lazy writers do not succeed. Successful writers do the hard work of learning how to think clearly, logically, and specifically, so they can immediately zero in on the questions most likely to help them find the right answers.

This does not mean you can’t or shouldn’t seek advice or feedback from your peers. We all need objective opinions to help us see ourselves and our work clearly. We can all benefit from the knowledge of those who have traveled the path ahead of or beside us. But neither should we rely on them. It’s not their job to find answers to our questions. Writing is, after all, a solitary journey. You have to make your own way. And the best way forward is always via informed, purposeful questioning.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What is your process for finding the best answers to your pressing writing questions? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/questions-not-to-ask.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 4 Questions You Should Never Ask About Your Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 18, 2017

Multiple Narrators? How to Choose the Right POV

If you’re writing a multiple point of view novel—whether you’ve got two POV characters or an ensemble cast of POVs—it’s critical you know how to choose the right POV character’s perspective for each scene in your story.

If you’re writing a multiple point of view novel—whether you’ve got two POV characters or an ensemble cast of POVs—it’s critical you know how to choose the right POV character’s perspective for each scene in your story.

This may seem like a no-brainer, something that happens instinctively as you write, but I often see stories in which the wrong perspective is used in a scene. The results can be ugly, ranging from decreased tension to reduced reader engagement. If you just gasped and placed your hand over your mouth, you understand how serious a matter using the right POV is for every scene.

The Pitfalls of Multiple POVs

The problem with pits is that they’re easy to fall into and hard to climb out of.

There are several mistakes writers make with multiple-POV stories. The more POV characters you have, the easier it is to make these mistakes. I’ll list them here, but if you’d like more detail, they’re thoroughly covered in my book The Story Works Guide to Writing Point of View.

There are several mistakes writers make with multiple-POV stories. The more POV characters you have, the easier it is to make these mistakes. I’ll list them here, but if you’d like more detail, they’re thoroughly covered in my book The Story Works Guide to Writing Point of View.

Attachment Issues: with many POV characters, it can be difficult for the reader to bond with any one character.

Head Hopping: when transitions between characters’ perspectives lack clarity, it can create confusion as the writer hops, frog-like, through the various POVs.

Underdeveloped Characters: with so many POV characters to write, it can be difficult to make them all fully realized beings with unique perspectives.

Spoiler Alert: an unearned POV, especially the antagonist’s, often does little more than broadcast what’s to come, spoiling tension as the story moves forward.

The simplest solution is to write in a single point of view. Barring that, limit the number of POV characters in your story to two or three. Less really is more.

When Your Story Demands Multiple POVs

Some stories are best told with multiple POV characters. Even with a small head count, it’s easy to trip. Besides tying your shoelaces before you go out, how can you avoid falling?

Always remember your story should have a clear protagonist at the center of the action. Of course, if you are writing a romance with a dual point of view, you may have two protagonists. If you are writing an epic fantasy with multiple worlds, you may have a protagonist per world.

However, for the sake of our discussion, we’ll assume a single protagonist at the center of an ensemble of three or more primary supporting characters with POVs. Even in a dual point of view story, you’ll be faced with having to choose the best perspective on any scene they’re both in, so read on!

Assess every scene you write in which there is a choice between POV characters by asking yourself these questions.

Is this scene, in this character’s perspective, telling the reader something she already knows or can easily infer? If so, the scene may be redundant or explaining something better left to subtext.

Is the scene broadcasting something about to happen? If so, the scene may be creating a spoiler and reducing tension.

Is the scene emotionally flat, doing nothing much to enhance the reader’s experience of the action or character? If so, the POV character may not be the one with the most to gain or lose in this scene.

Would the story be tighter, better paced, and have more dramatic tension without this scene? If so, it’s creating drag in your story’s forward momentum.

If you answered any of these questions with a yes, you need to revise or cut the scene. Or cut the character’s perspective.

When Your Story Demands an Ensemble Cast of POV Characters

Some stories need an ensemble cast to create an epic narrative. Organizing your ensemble before you write can save multiple revision headaches later, keeping you out of the pits altogether.

1. Create a Casting Hierarchy

Even if you haven’t written a word of your book, you should have enough prewriting under your belt to know who your team players are and what roles they’ll fulfill in the story. Line them up in order of importance.

You might decide rank based on:

How long the character lasts in the story

How crucial a role he fulfills

How much readers like, or are expected to like, him

How necessary he is to the forward movement of the plot

This hierarchy is your first guideline for how to choose the right POV. Look at the characters in the scene and use the highest-ranking character’s perspective.

Sometimes choosing the right POV is that simple, but often it’s not. That’s where other guidelines come into play.

2. Narrow Down the Heirarchy

For any scene in which the hierarchy isn’t enough to choose the right POV, ask yourself these three questions.

1. What is the purpose of this scene? The readers’ takeaway?

2. Which character is the stakes highest for right now?

3. Who will readers be most emotionally engaged with?

These guidelines take the guesswork out of how to choose the right POV. They help you base your decision on both how to best advance your story and how you want your scene to affect your reader.

Get Writing!

By applying these guidelines for how to choose the right POV, you can ensure every scene has the forward momentum to keep readers turning pages.

By applying these guidelines for how to choose the right POV, you can ensure every scene has the forward momentum to keep readers turning pages.

Get a Choose the Right POV PDF booklet, perfect for avoiding POV pitfalls. It will guide you through both character and scene assessment with an example and printable worksheets.

By choosing the right POV, you’ll be able to create the most compelling, dynamic, unforgettable scenes possible!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! How do you choose the right POV for your story’s scenes? Tell me in the comments!

The post Multiple Narrators? How to Choose the Right POV appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 14, 2017

4 Ways to Write a Thought-Provoking Mentor Character

Part 16 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Part 16 of The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

Good stories rise and fall based on their minor characters. You can write an amazing protagonist, but if he isn’t supported by an equally amazing cast, the story will fail to fully develop the protagonist himself, fail to flesh out the thematic premise, and, bottom line, fail to be entertaining.

But it’s not enough to just run through a checklist of must-have characters (which we’ve already discussed in posts on Iron Man 2 and Doctor Strange). You’ve also got to make sure your take on the archetypal roles—such as the mentor character—is fresh, interesting, and not stereotypical.

Character archetypes exist within a story form to fulfill necessary angles of the thematic argument. With even one missing archetype, the overall story arc will be weakened. But authors who are committed to a rounded cast must be wary of letting their archetypes become stereotypes. You must balance the challenge of presenting characters who fulfill concrete roles in the story with the equally great challenge of presenting those characters as fully-rounded, interesting, dichotomous, surprising human beings.

Marvel’s Spider-Man: Homecoming performed this balancing act admirably with many of its characters (including its family-man antagonist the Vulture). Today, I want to focus particularly on what you can learn from this film about creating a mentor character who is more than just a font of good advice.

>>To read the Story Structure Database analysis of Spider-Man: Homecoming, click here.

Look Out! Here Comes the Spider-Man! (And the Iron Man!)

Welcome to Part 16 in our ongoing exploration of the good and the bad in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Marvel’s deal with Sony to get their flagship character into the mix was big news for me. My love of superhero fiction began with Sam Raimi’s excellent Spider-Man 2 back in 2004. For me, Spider-Man has always been the superhero. So even though we’ve only had a gazillion Spidey movies in the last fifteen years, I was cautiously optimistic about what Marvel could “officially” do in rebooting the character one more time.