5 Ways to Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters

The Enneagram. Maybe you’ve heard of it. Maybe you’ve even used the Enneagram to write better characters.

The Enneagram. Maybe you’ve heard of it. Maybe you’ve even used the Enneagram to write better characters.

Like Myers-Briggs, Socionics, and the Four Temperaments, the Enneagram is one of many systems within the study of personality theory. These systems are designed to identify the patterns found in the different ways we approach various aspects of life, so we might better study and understand ourselves and others.

In short, the Enneagram is not only a useful life tool, it’s also the perfect character-creation tool.

I’ve always been interested in personality theory. Let’s face it, I just like theories (come to me, story theory, my love). But I don’t see it as any kind of coincidence that my interest in characters and stories dovetailed so conveniently with the ever-deepening rabbit hole of personality theory.

I’m not alone. In fact, my introduction to the Enneagram, many years ago, was on romance author Laurie Campbell’s site, where she offered a brief description of the system’s nine types as, you guessed it, a character tool. Since then, I’ve pursued Myers-Briggs—another personality-typing system—in some depth, but only this year have I finally dived headlong into the Enneagram.

I’m not exaggerating when I say it has changed my life—and my writing.

What Is the Enneagram?

Unlike Myers-Briggs, which is a “neutral” system focused primarily on the differing ways people take in and use information, the Enneagram is often called an “ego-transcendence tool.” Sounds all lofty and new-agey, but it’s really just code for “this-is-gonna-hit-you-where-it-hurts.”

(Side Note: I read once, in relation to Myers-Briggs, that if you typed yourself and had nothing but excitement about your discoveries, you very likely mistyped. A true typing is going to show you stuff about yourself that maybe you’d rather not look at. In short, you can be pretty sure you’ve found your type when you end up muttering, “Ah, dang.” If that’s true of Myers-Briggs, it’s about ten times truer of the Enneagram. But I digress.)

In their book The Road Back to You (which is a great overview of the Enneagram, uncomplicated by denser aspects of the theory), Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile introduce the Enneagram like this:

In their book The Road Back to You (which is a great overview of the Enneagram, uncomplicated by denser aspects of the theory), Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile introduce the Enneagram like this:

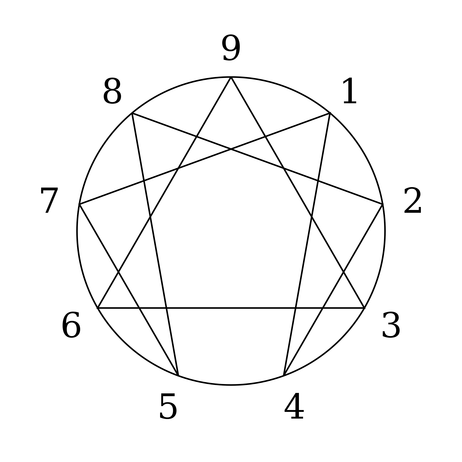

The Enneagram teaches that there are nine different personality styles in the world, one of which we naturally gravitate toward and adopt in childhood to cope and feel safe. Each type or number has a distinct way of seeing the world and an underlying motivation that powerfully influences how that type thinks, feels, and behaves….

The Enneagram takes its name from the Greek words for nine (ennea) and for a drawing or figure (gram). It is a nine-pointed geometric figure that illustrates nine different but interconnected personality types. Each numbered point on the circumference is connected to two others by arrows across the circle, indicating their dynamic interaction with each other.

The Enneagram is a vast and deep system, impossible to completely summarize in a post like this, so I won’t even try. However, perhaps the simplest way to sum it up is to say that the Enneagram is designed to call baloney on the defensive lies we have been programmed from childhood to tell ourselves about ourselves and the world.

How I Discovered the Enneagram

My experience with the Enneagram went something like this.

I’d decided long ago, after reading the brief descriptions on Laurie Campbell’s site, that I was a Five: The Investigator. Introverted, studious, quirky. Yeah, totally. Fives are awesome!

Confidently, I started reading Cron and Stabile’s book—until I hit the chapter about the Three: The Achiever. It was like the authors reached out, grabbed their own book, and smacked me between the eyes with it. It was a total oh-dang moment.

Don’t get me wrong. Threes are awesome too. Productive, adept, ambitious. But I immediately knew, without question, I was a Three simply because so much of what I read hurt.

I would have been totally cool (too cool) with the Five’s problems of hyper-independence, trust issues, and sarcasm (because, hello, that’s all my favorite characters ever). I’ve always considered myself a relatively self-aware, self-honest person, but reading about the Three’s motivations made me face things about myself I’d never been willing to admit or face, things I really didn’t like about myself, such as the driving need for the approval of others and a pervasive underlying belief in, essentially, “salvation (and love) by works.”

For me, the revelations that followed were toppling dominoes that unlocked answers to questions I’d been asking about myself and my life for a long time. It was painfully liberating. My awareness of my Three-ness has since allowed me to acknowledge and own aspects of myself I’ve long hidden from, which, of course, now means I have to deal with them. It has been and continues to be incredibly exciting.

And now I get to use these new approaches to life, people, and the self to help me (I hope) write better characters.

Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters

There is just so much to say about how you can use the Enneagram to write better characters. I’m not even going to get into the wings, triads, integration/disintegration, instinctual variants, or tritypes (the latter of which I have yet to study in any depth but which, I think, bears out I wasn’t totally wrong in my initial association with the Five).

It was in reading Don Richard Riso’s Enneagram “bible” Personality Types that I was truly blown away by both the beautiful complexity of the system and its easy applicability to writing characters. After listening to the book on audio, I immediately bought my own copy and added it to my pile of easy-reach writing-resource books. I will be referring to it regularly when I start outlining my next book.

It was in reading Don Richard Riso’s Enneagram “bible” Personality Types that I was truly blown away by both the beautiful complexity of the system and its easy applicability to writing characters. After listening to the book on audio, I immediately bought my own copy and added it to my pile of easy-reach writing-resource books. I will be referring to it regularly when I start outlining my next book.

Following are the five primary ways I plan to use the Enneagram to write better characters in the future.

1. Typing Characters, the Fast and Easy Way

Let me start with a slight digression: I’ve been studying Myers-Briggs for years. I love it. In its own way, it too completely changed my life and my writing. But I actually find the system really difficult to use in typing my characters. For whatever reason, I can type other people’s characters with reasonable confidence, but I can’t type my own to save my life. For example, I have progressively typed Chris Redston, the protagonist of Dreamlander as: ISFJ, ESFJ, INFJ, ISFP (with ponderings about ISTJ and INTJ thrown in for good measure).

Let me start with a slight digression: I’ve been studying Myers-Briggs for years. I love it. In its own way, it too completely changed my life and my writing. But I actually find the system really difficult to use in typing my characters. For whatever reason, I can type other people’s characters with reasonable confidence, but I can’t type my own to save my life. For example, I have progressively typed Chris Redston, the protagonist of Dreamlander as: ISFJ, ESFJ, INFJ, ISFP (with ponderings about ISTJ and INTJ thrown in for good measure).

(Second Side Note: I actually have serious doubts that any author is able to truly write a character with differing cognitive functions from their own. For example, as an INTJ, I might be able to fake an ESFJ character based on ESFJs I personally know, but because I share no functions with that type, can I really write about the mental process of a character who absorbs information via Introverted Sensing and makes judgments via Extroverted Feeling? Maybe, but I kinda doubt it.)

In contrast to Myers-Briggs, the deceptive simplicity of the Enneagram makes it much easier to confidently recognize a character’s likely type/number and use it as a guideline while writing. Maybe it’s just me, but I find it far less complicated to look at a character and recognize, “she’s a One,” rather than running through a litany of criteria to determine her four cognitive functions and their order in her Myers-Briggs stack.

When I do figure out a character’s Enneagram, I instantly see them a little clearer, and I instinctively know just a little bit more about them. (Chris, by the way, is a Six. In case you were wondering.)

(Third Side Note: Although there is some overlap, the Enneagram is an entirely different system from Myers-Briggs, with an entirely different focus. Typing a character according to the Enneagram doesn’t accomplish the same things as will typing that character according to Myers-Briggs. So if you feel qualified—or, like me, literally unable to resist, do both!)

2. Keeping Characters Consistent: Strengths and Weaknesses

One of the Enneagram’s primary focuses is each type’s inherent strengths and weaknesses. This is convenient, since one of a writer’s primary focuses is each character‘s inherent strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, we could argue that the pairing of strength/weakness is one of the most important aspects of character, and thus story, since it drives everything that happens in the plot and theme.

In expanding on the chart at the beginning of the post, a super-simplistic approach to each type’s strength/weakness might look like this:

One, The Reformer: Responsible and idealistic/judgmental and hyper-perfectionistic

Two, The Helper: Kind and generous/intrusive and needy

Three, The Achiever: Productive and adaptable/overly image-conscious and out of touch with emotions

Four, The Individual: Creative and idealistic/self-absorbed and unrealistic

Five, The Investigator: Perceptive and self-reliant/emotionally-detached and cynical

Six, The Loyalist: Loyal and engaging/reactive and fearful

Seven, the Enthusiast: Optimistic and fun/impulsive and undisciplined

Eight, the Challenger: Bold and decisive/domineering and combative

Nine, the Peacemaker: Calm and reliable/passive-aggressive and unmotivated

Once you really start studying the system, you realize there’s so much more to it than just this. But even just these simple starting points give you an intuitive strength/weakness pairing for your character that sets everything up right for a solid character arc.

3. Identifying the Character’s Motivation, Want, Need, and Backstory “Ghost”

Because of the Enneagram’s talent for pointing a finger at painful motivations arising from our pasts (especially our childhoods), it’s perfect for figuring out the backstory Ghost motivating your character’s goals in your main story.

The Ghost (sometimes called the Wound) is a hole in your character’s self. It’s the hole where the Lie the Character Believes first started growing, and it’s the hole she must climb out of if she’s to grow into wholeness by the end of her arc.

Again, not so coincidentally, the Enneagram offers a basic Lie for each type:

One: Mistakes are unacceptable.

Two: I am not lovable.

Three: I am what I do.

Four: No one understands me/there is something wrong with me.

Five: I am not competent to handle the demands of life.

Six: The world is not safe.

Seven: I can’t count on people to be there for me.

Eight: Only the strong survive.

Nine: I don’t matter much.

Starting with some iteration of the above for your character, you can start extrapolating consistent motivations and goals within the specific needs of your plot.

4. Charting Character Arcs

Not only is the Enneagram system helpful in setting up character arcs, it’s also helpful in double-checking that the progression of your character’s arc is consistent and realistic.

One of the main reasons I ended up buying a hardcopy of Riso’s Personality Types was that the book methodically charts nine levels of “health” for each type. It divides these nine levels into three apiece under the headings of Healthy, Average, and Unhealthy. Once you know your character’s specific story Lie and the type of arc you want him to follow, you can reference Riso’s lists to nail down how a healthy, average, or unhealthy person of this type would behave.

For example, if you’re writing a Positive Change Arc for a generally likable character, you’re probably going to to start him out in one of the Average categories and let the story’s events help him progress to Healthy. Or maybe you’re writing a Negative Change Arc, about a descent into unwellness or psychosis, which brings me to…

5. Writing Better Bad Guys

For me, bad guys have always been one of my challenges. A large part of this was a struggle to find suitable motivations for their evil deeds. “Oh, they’re just crazy” is an easy out that doesn’t give due diligence to what should be one of the strongest characters in the story.

Yet another reason I was psyched by Riso’s “health charts” was that they immediately grounded my understanding of what would motivate a deeply unhealthy person to commit deeply unhealthy acts. At the bottom level of psychosis for each type (which is almost never reached without either deep-seated childhood trauma or a physiological catalyst), Riso suggests the “ultimate end” each type is most likely to fall to:

One: Punitive Sadism

Two: Hypochondria and Martyr Complex

Three: Murder (!)

Four: Suicide

Five: Schizophrenia

Six: Masochism

Seven: Addiction and Manic-Compulsive Behavior

Eight: Megalomania

Nine: Dissociative disorders

Personally, I take these with a massive grain of salt (because how likely is it that all, or even the majority of schizophrenia sufferers, are Fives?). But it is a useful guide for following the descent of personal and mental un-health to a consistent ending point. If you read all the sections in Riso’s book, it becomes easy to provide a proper motive to a character who is undergoing a realistic personal descent.

***

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the Enneagram. I’ve been studying it for months now and have barely scratched its surface. If you’re interested in digging deeper, both for yourself and your characters, I recommend starting with the book The Road Back to You by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile and following it up with the significantly heavier and more in-depth Personality Types by Don Richard Riso with Russ Hudson.

Brace yourselves, half fun, and get ready to say: Oh, dang. :p

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever used the Enneagram to write better characters? Tell me about it in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/5-ways-to-use-the-enneagram-to-write-better-characters.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 5 Ways to Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

newest »

newest »

Gadzooks, was that interesting. So much to think about, I'm going back to bed.

Gadzooks, was that interesting. So much to think about, I'm going back to bed.

I discovered the enneagram earlier this year, and I also found it life changing personally, and great fun for thinking about characters in fiction. I've noticed that if I can type a character in a book or film, then they are a really strong, memorable character - which is a challenging thing to think about in my own character creation.

I discovered the enneagram earlier this year, and I also found it life changing personally, and great fun for thinking about characters in fiction. I've noticed that if I can type a character in a book or film, then they are a really strong, memorable character - which is a challenging thing to think about in my own character creation.