K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 31

March 9, 2020

Critique: 6 Tips for Introducing Characters

Most of the time, I hate real-life introductions. For one thing, I almost always forget the person’s name in the rush of shaking hands, smiling, and saying something charmingly banal. Then there’s the small talk, important but often tedious. Squirm. But that’s most of the time—because occasionally I run into one of those special people who is just brilliant at introductions. You know the ones. Just like a good hook in a story, these people immediately grab your attention. You go from being interested in getting to the point to being interested in them.

Most of the time, I hate real-life introductions. For one thing, I almost always forget the person’s name in the rush of shaking hands, smiling, and saying something charmingly banal. Then there’s the small talk, important but often tedious. Squirm. But that’s most of the time—because occasionally I run into one of those special people who is just brilliant at introductions. You know the ones. Just like a good hook in a story, these people immediately grab your attention. You go from being interested in getting to the point to being interested in them.

That, right there, is the main secret in introducing characters in your story, especially in the first chapter when you’re using these characters to hook readers into sticking around past the small talk.

Successfully introducing characters in a way that highlights all their fantastic potential is one of the trickiest parts of writing a strong first chapter. Part of this challenge is that these characters must indeed offer potential. Experienced readers are quick to intuit that flat character introductions signal characters who lack staying power to support an entire story.

Then there’s the technical challenges of choosing the right descriptive details to show who these characters are, without bogging down the story in too much early information. When introducing multiple characters at once (as you almost always will be), the challenge increases, since you also have to juggle dialogue attributions, multiple descriptions, motivations, subtext, and more.

Learning From Each Other: WIP Excerpt Analysis

Today’s post is the seventh in an ongoing series in which I am analyzing the excerpts you have shared with me. My approach to these critiques is a little different from those you normally see on writing blogs. Instead of editing each piece, I’m focusing on one particular lesson that can be drawn from each excerpt, so we can deep-dive into the logic and process of various useful techniques.

Today, my thanks to Kelly Cliff for sharing from her urban fantasy Urban Warriors. She noted:

I guess my main concerns are if I’m handling dialogue well and making things interesting, as well as making sure my characters’ personalities feel different from each other while not straight-up telling everything about them. This is a first draft so it needs work.

Let’s take a look! The bolded entries and subscript numbers will correspond with the tips I’ll talk about in subsequent sections.

“Eva, nice to see you. Come in.”1

She2 couldn’t help tugging at her hoodie as she entered. Her torn black jeans and old checkered shirt contrasted sharply with Greg’s suit and the beautiful entryway.3

“Blitz!”

A large green blanket hit him in the face.4 With a grunt he pulled it off of his head. Carissa5 rushed down the stairs after it, today clad in an octopus-themed sweatshirt and rainbow jeans.

“Oh, hi Eva. Blitz, you lost and now you need to wear that.”

A frown formed on his brow. “A blanket?”

“No, silly!” She grabbed the fabric and shook it out to reveal a dinosaur suit. “It took a long time to find that. All day, remember?”

This time real panic etched his face. “Today?”

Eva covered her mouth with her hand. Only a suspicion of a laugh escaped. She coughed.

“Rogue6, I have to go to court today!”

The girl6 shrugged. “Rules are rules. Sorry, gotta run!” She hurried out the door.

6 Tips for Introducing Characters Without Confusing Readers

Speaking generally, you have two basic goals to accomplish when you introduce characters.

Get Readers Interested in the Characters

This involves injecting your characters’ unique personalities into their introductory descriptions, actions, and dialogue—so readers will get a sense of these people as quickly as possible and be intrigued by their personalities, dichotomies, and humanity (or lack thereof). Basically, this is the essence of a well-drawn Characteristic Moment.

Keep Readers Oriented

In trying to introduce all the most interesting aspects of a character(s), we end up juggling a lot of information. Most of the time, the true trick is to distill all that info into tiny cues that don’t slow down the story’s forward progression. Regardless the actual amount of info you’re sharing, you must share it in an organized way that allows readers to assimilate it without confusion, so they can move on with a clear idea of the new characters.

In short, your ultimate goal in introducing characters should be to bring them onstage with the least amount of information possible but in a such a way that even small walk-on characters are easily memorable when they re-enter the story later on.

Readers should never have to ask, “Who?”

That said, let’s take a look at a few ways Kelly can tighten up her characters’ introductory scene to achieve these two goals.

1. Establish Unique Character Voices Right Away

Some of the most important words a character will ever speak are his first words. Ideally, the first words out of a character’s mouth should immediately give readers a sense of who this person is. You can accomplish this via a number of nuances, including:

What the character says.

Why the character says what he says.

The specific word choices that indicate background, personality, mood, and intention.

The accompanying body language and action beats that further clarify (or perhaps contrast) the actual dialogue.

This is doubly important when an opening line of dialogue not only introduces the character but also the story itself, as in Kelly’s excerpt: “Eva, nice to see you. Come in.” This is a reasonable way for just about any person to acknowledge another person. But by that very credibility, it doesn’t offer much in the way of personality. It would be better to introduce the speaker with a line of dialogue that only he would say.

2. Name Characters When Necessary to Avoid Confusion

It’s almost always preferable to name characters as soon as you introduce them. Even when a character’s name is made clear in the dialogue, it’s still usually best to anchor her identity by repeating it in the text rather than opting for the greater narrative intimacy but also greater potential for confusion offered by a pronoun.

In the excerpt, the speaking character names the POV character—“Eva.” But because we don’t yet know the speaker, we can’t be certain the “she” that opens the next paragraph isn’t the speaker, rather than Eva. Even if readers orient quickly, there’s still the risk of that initial blip of confusion—which is definitely not something to take a chance on in the opening paragraphs. Fortunately, it’s an easy fix. All you have to do is name the character.

3. Deftly Weave in Personal Descriptors

Descriptions are tricky, especially in openings, since they can easily careen into info-dump territory. But they’re also extremely important, since they not only ground the scene, but also allow you to add further introductory details. Describing a character’s appearance, clothing, and personal environment can offer a great deal of information in as little as a sentence.

Kelly does a perfect job with this, via a quick contrast of the characters’ clothing. She doesn’t overdo it, and it feels unobtrusive since the description is both quick and pertinent—it hints at the protagonists’s inner feelings about herself, the other character, and the setting.

4. Ground Characters in the Setting

Just as important as introducing the characters themselves is introducing the setting in which they’re acting. Not only will the setting help you define them (i.e., how comfortable they are in this place), it also gives readers something to visualize. However, this only works if readers feel grounded enough within the setting to understand where the various characters are positioned.

This becomes even more important when additional characters enter the scene. Readers need to understand from where the new characters are entering and where they are positioned in relation to the already introduced characters.

Kelly introduces a third character onto the scene by describing the protagonist’s first awareness of her: a blanket flying through the air out of nowhere. Although this is an accurate description of the protagonist’s experience, it’s potentially disorienting for readers who currently lack enough information to visualize the scene. Also, unlike the protagonist, readers have no idea what the blanket may signify, since they don’t yet know of Carissa’s existence and aren’t able to quickly recognize that a flying blanket probably originated with a lively friend.

The flying blanket does seem a good Characteristic Moment of Carissa. But it would be better to at least indicate from where the blanket came flying (the stairs), or perhaps even to immediately indicate that the blanket was thrown (instead of materializing). Even giving Carissa’s initial bit of dialogue (“Blitz!”) a speaker tag would help, since readers don’t yet have any reason to think that line is spoken by someone other than the two already-introduced characters.

5. Separate New Actors/Speakers With New Paragraphs

Especially in scenes in which you will be introducing a number of characters in a short amount of time, you will want to do everything possible to streamline the experience and avoid confusion. One of the simplest ways to do this is to make sure you’re correctly using paragraph breaks to guide your readers’ experience (something we’ve talked about in a previous critique post).

Just as we separate multiple speakers’ dialogue onto separate paragraphs, we should also separate multiple actors’ actions. When Carissa arrives on the scene, her initial action (throwing the blanket) should be separated from Greg’s reaction, then separated again from her running down the stairs. Her first line of dialogue could then be attached to her action paragraph.

Behind Greg, Carissa rushed down the stairs. “Blitz!” When he turned, she hurled a blanket into his face.

With a grunt, he pulled it off his head.

Carissa ran down the rest of the stairs. Today, she wore an octopus-themed sweatshirt and rainbow jeans.“Oh, hi, Eva. Blitz, you lost and now you need to wear that.”

6. Use Nicknames and Titles With Care

When naming characters, consistency is almost always best. Nicknames and titles (e.g., “the lawyer” or “the girl”) should be used with consciousness and care. Especially within the narrative itself, it’s best to stick to one naming convention for each character.

When you do use a nickname in dialogue make sure readers know who is being referenced. This is especially important in introductory scenes when readers are just learning the characters’ proper names—and often learning them via dialogue as well. Introducing multiple characters at once is tricky enough; it gets confusing fast when readers must learn not just the characters’ actual names but also their nicknames.

Most of the characters in Kelly’s excerpt (which I didn’t include in its entirety due to space) have nicknames, which I’m guessing are “alter-ego” names referencing some special skill or superpower. My recommendation would be to introduce these nicknames more gradually. Especially in these opening paragraphs, the identities of “Rogue” and “Blitz” aren’t immediately clear (I initially thought Blitz was some kind of tag game, having to do with the thrown blanket).

***

Introducing characters is one of the joys of writing—since it means bringing characters on stage and letting them do their thing. It is also one of the most meticulous procedures in all fiction. If you can master it, you will give readers the great pleasure of an immediate immersion into the exciting world of your characters.

My thanks to Kelly for sharing her excerpt, and my best wishes for her story’s success. Stay tuned for more analysis posts in the future!

You can find previous excerpt analyses linked below:

5 Ways to Successfully Start a Book With a Dream

How to Use Paragraph Breaks to Guide the Reader’s Experience

8 Quick Tips for Show, Don’t Tell

4 Ways to Write Gripping Internal Narrative

10 Ways to Write Excellent Dialogue

10 Ways to Write a Better First Chapter Using Specific Word Choices

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your biggest challenge right now in figuring out how to write a better first chapter? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post Critique: 6 Tips for Introducing Characters appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 2, 2020

Creativity vs. the Ego (Or, the Value of Unpublishable Stories)

Why are you writing?

Why are you writing?

It’s a question almost as vast and confusing as the dreaded, “What are you writing?”

Why we write… We write for ourselves. We write for others. We write to have fun. We write to pay the bills. We write for fame and glory. We write in search of hope and justice and meaning.

So many reasons, each as valid as the next. It can get confusing to try to sort through the variety to find a central motivation. For many of us, the reasons we started writing or making up stories—perhaps as far back as our childhoods—have become enmeshed within our life practices. We write now because that is how we have learned to express ourselves, to share the insights and symbols we believe have value, to scratch a creative itch we don’t always contemplate so long as it stays scratched.

That creative itch goes very deep indeed. It represents life’s ineffable questions and our driving compulsion to find answers however abstract. As my new favorite quote from Cynthia Ozick says:

[Writing is] a kind of hallucinatory madness. You will do it no matter what. You can’t not do it.

That truth is almost inescapable for most of us. Even when we’d very much rather not write—or even not be a writer—something keeps bringing us back to the page and the words. Still, the purity of that compulsion can get muddied by the many other motives and goals to which it gives birth.

Often, these other goals—publication, for example—can seem so worthy in their own right they take over. We forget the reason we’re writing really isn’t “to be published.” We forget that’s another thing entirely. When we forget that, we’re also inclined to forget that the worth of what we write and the time we spend writing it cannot be judged by anything so neat as “publication.”

Creativity vs. the Ego

The ego has staked out a big plantation in the land of our creativity. From childhood onward, so much of our creativity is related to our identity and therefore our self-worth. Whether Mom and Dad liked our finger paintings may give us a huge boost of confidence—or not—in the art we make later in life.

The ego, however vital and useful, has a way of taking over the show. It’s so easy for our art to become a servant of our ego, rather than the other way around. We want the world to tell us our writing is clever, brilliant, life-changing, un-put-down-able. When we receive the praise, we purr. When we don’t, we sometimes go so far as to give up altogether.

Either way, when creativity serves the ego, we often get confused about what we’re doing, why we’re doing it, and what we are really getting out of it.

The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron

I’ve been blessed to spend the last three months reading Julia Cameron’s incredibly elegant and poignant classic The Artist’s Way. The entire book is about creating for ourselves. She writes:

…if I have a poem to write, I need to write that poem—whether it will sell or not.

That’s a hard pill to swallow—especially if you’re a professional writer with obligations to fulfill. But even if your initial response is resistance, I’ll bet you can also find at least a spark of begrudging relief too.

As I’ve occasionally written about throughout the past year, writing has been really hard for me lately. Partly, that’s been due to some personal crises and growth. But largely, it’s been due to the fact that I had this genius idea to turn my standalone portal fantasy Dreamlander into a trilogy. Never mind that writing sequels and series is uncharted territory for me, there’s also the little fact that this story was never intended to be more what it was. [Insert appropriate *what was I thinking?!* meme.]

I’m not yet giving up on the project, but I am having to contemplate the fact that I may not, at this time, be able to finish the series in a way that’s worthy of publication. If that turns out to be true, there’s a part of me that is tremendously disappointed at having “wasted” four years.

I think, however, that Cameron would want me to ask if those years were really wasted after all. In a morning journaling session after reading her book, I found myself having to recognize how much of a driving force my ego is in my creativity:

As I struggle to turn my Dreamlander sequels into stories of true form and depth—stories that are good enough to publish and share—and as a great part of me doubts that this may be possible—I find myself realizing the surprising weight of my ego pressuring me to calculate the worth of the work based solely on the accuracy of its storyform and the potential for its impact to not just touch a reader’s life but to receive his or her acclaim.

I say routinely that I write for myself and that the process of these stories, even if that’s all there is, is worth it. But at some level I don’t really believe that. The time and the lessons may not have been strictly wasted; but how much better to have gained the lessons through time spent on a fruitful project that could have been brought full-term with grace and control?

But that—I see suddenly with shocking clarity—is ego talk.

The story is for me. The creation is for me. If it is a misshapen child, I need love it no less. If I have poured my passion and my fury and my desperate hope into it—and they have burned so hot that they have melted straight through all my current grasp of the craft that tries to contain them—surely, that is a sign of something greater rather than something weaker.

Do I judge the worth of my work on whether it is shapely, whether it is pleasing to others, whether it earns the lofty distinction of “making a difference”?

The work is the worth—because I am the work. My whole life is the work. To judge the worth of that on the satisfaction of others, who are not me, or the craving for the power and control that would allow me some hand in shaping the world—that is the cry of the ego. That is not the heart of the work. The ego is not my judge.

6 Beliefs to Foster Creativity and Growth

I write this post with something of a bitter taste in my mouth. As I acknowledged in the journal entry, I don’t really like the idea that I should see an unpublishable story as worthwhile in its own right. (My ego is currently sitting in the corner of my brain, arms crossed, looking very huffy.) Honestly, I don’t think many of us really do.

For almost all writers, the goal is to publish. It is a worthwhile goal. We see it as a way to fulfill our dreams, to earn a living doing something we love, to live an impactful life (and also, let’s be honest, to be rich and famous, beloved and acclaimed). It’s hard to refute this in a global writing community that is predominantly focused on commercial appeal. It would seem everyone judges creativity by its net worth.

But as individuals, we don’t have to. Nothing is ever wasted. I believe that even if I decide not to publish these sequels to Dreamlander, the lessons I have learned as a writer and a person (and they have been manifold) have been life-changing.

My encouragement to you (and me) is to remember that the true worth of creativity—as a mirror of life itself—is in the journey much more than the destination. Joseph Chilton Pearce writes:

To live a creative life, we must lose our fear of being wrong.

Sometimes that wrongness can be as simple as writing something magnificent… that we can’t publish.

Some of you reading this are writing projects right now that you fear (perhaps rightly, perhaps wrongly) will never go farther than your desk. Some of you are writing projects you already know, deep down, aren’t going to fly free in the world. Some of you are writing projects that were always and ever intended only for yourself. And some of you are writing projects that are going to make it off the launch pad, maybe even all the way up to rattle the stars.

Whichever story is yours, the distinction doesn’t matter right now. Right now, as you’re writing, this story is yours. Here are six affirmations to keep in mind whenever you find yourself judging your writing and yourself too harshly.

1. Believe the Act of Writing Has Worth in Itself

The struggle is the glory. Or as Brenda Ueland says:

Why should we use our creative power…? Because there is nothing that makes people so generous, joyful, lively, bold and compassionate, so indifferent to fighting and the accumulation of objects and money.

2. Believe Every Story You Write (Even the Unpublishable Ones) Teaches You About Yourself and Your Life

Picasso said (I’m shamelessly stealing quotes from those Cameron curated):

Painting is just another way of keeping a diary.

3. Believe Every Story You Write Teaches You How to Write Something Better Next Time

I’ve written before about the value of “lost” novels. Failures are only failures when we give them that distinction.

4. Believe Your “Failures” Are Less About Your Lack of Skill and More About Your Great and Ambitious Potential

We always intend to write something better than what actually shows up on the page. Always. With some stories, the gap between our vision and our current level of skill is more noticeable than with other stories. But the fact that we can dream up something so tremendous—even if we don’t yet know how to get it out of our minds and into reality—doesn’t signify failure.

5. Believe That if You Love Your Story, It Doesn’t Matter if Anyone Else Does

This one is so hard—but so important, I believe. If I write something that helps me—in any measure—that thing has worth. I’ve been compelled to set stories aside before, but they are still my children just as much as the published novels—perhaps even more so, since they are mine alone, to be cherished with a fondness unadulterated by anyone else’s opinion or experience.

6. Believe You Are Writing What You’re Supposed to Be Writing—Where It Goes From Here Is Not the Most Important Thing

Not every story deserves publication. Being able to acknowledge when a story doesn’t measure up to a reading audience’s standards is an important instinct for writers to develop. But just because a story doesn’t deserve to be published does not mean it doesn’t deserve to be written. Write what you love. Write what you’re passionate about. Write what makes you curious, what gives you hope, what helps you seek justice. Write to the ragged limit of your skills. Or as Andre Gide says, in one final quote:

One does not discover new lands without consenting to lose sight of the shore for a very long time.

***

So here’s to stories that are amazing and perfect, well-formed and publishable. We all like those. But here, too, is to stories that are the precious, malformed byproducts of our growing pains. May we know the difference, and may we see the worth in each, so that we may count our hours at the desk in the light of our triumphs rather than our failures.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you feel about the stories you’ve decided aren’t “good enough” to publish? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post Creativity vs. the Ego (Or, the Value of Unpublishable Stories) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 24, 2020

The Professional Writing Resources I Use for All Parts of the Writing and Publishing Processes

These days, most authors identify with the title “authorpreneur.” In order to sell books, we have learned to wear multiple hats. We aren’t just writers, we’re marketers, bloggers, graphic designers, and more. As such, we are always in search of professional writing resources that can help us make the best use of our time and show off our stories in the best possible light.

These days, most authors identify with the title “authorpreneur.” In order to sell books, we have learned to wear multiple hats. We aren’t just writers, we’re marketers, bloggers, graphic designers, and more. As such, we are always in search of professional writing resources that can help us make the best use of our time and show off our stories in the best possible light.

About a week ago, I answered my own Writing Question of the Day (posted on Facebook and Twitter), which in turn prompted a request that I discuss some of my experiences with professional writing resources.

In the earlier years of my career as a full-time writer, I tried just about any service or product that came down the line. On some of my books, I went the full-blown, try-everything route. But these days, I’ve gotten better at knowing what is most useful, time-effective, and cost-effective for me.

Below, I’ve listed all the product-production categories that pertain to me (although I’ve probably forgotten a few). I’ll talk about a few of the things I’ve tried and no longer use, for whatever reason, but for the most part I’m going to be sharing only the things I currently use as part of my routines for writing, publishing, and promoting my work and my website.

Although I agree it’s valuable to see what others are doing, it’s also important to keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to successful authorpreneurship. One of the reasons I rarely write on marketing and publishing topics is that I don’t feel what works for me is necessarily the approach everyone should use. I also don’t consider myself a publishing/marketing expert or guru. Some of the authors whom I follow and am continually learning from on these subjects include:

Joanna Penn of The Creative Penn

Dave Chesson of Kindlepreneur

David Gaughran

Penny Sansevieri of Author Marketing Experts

Rob Eager of WildFire Marketing

Most of what’s below probably originated with them. :p

My Top 15 Professional Writing Resources

Below, you’ll find a list of the various aspects of product production I engage in on a regular basis. You’ll find a handful of affiliate links because it is my policy to share affiliate links only for products or services I use and love myself—and these are those products!

1. Writing Software and Tools

My writing process itself doesn’t rely on anything too gimmicky or fancy. For outlining, I use plain ol’ (recycled) notebooks, as well as Perry Elisabeth’s wonderful WriteMind Planner—which I reviewed here when I first started using it.

For drafting, I use the writer-specific word-processing software Scrivener. For years, I used and loved the free program yWriter. But since diving into Scrivener when writing my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer, I’ve never looked back. It’s an incredible program that offers an amazing capacity for organizing notes, scenes, chapters, and more. I’ve talked about my process for outlining, writing, and editing with Scrivener in these posts:

How I Use Scrivener to Outline My Novels

How I Use Scrivener to Write My First Drafts

How I Use Scrivener to Edit My Novels

I also offer a free Scrivener template, which approximates the one I’ve created for myself, as well as incorporating information from my approach to outlining, story structure, and character arcs.

You can also access my full outlining process via my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software, which is a digital version of my brainstorming guide by the same name.

2. Editors

I have hired various editors over the years, none of whom are currently taking new clients. These days, I don’t hire an editor, mostly because my beta readers are so awesome. One of those beta readers, Linda Yezak, is a professional editor in her own right. You can read about her services here.

You can also find a group-curated list of editors here (be sure to check the comments, as they contain many further suggestions).

3. Proofreader

My absolute top recommendation for proofreading—aka, typo-hunting—is to find software that will read your manuscript aloud while you read along. The old Kindle Keyboard will read aloud, as will Adobe Reader. I estimate I’m able to catch 95% of typos in my books using this method.

If you’re wanting to also hire a professional, I’ve often used the services of Wordplayer Steve Mathisen’s OddSock Proofreading & Copywriting.

4. Paperback Formatting

Through the years, I’ve personally formatted most of my books, using the typesetting software InDesign. At one point when I was experiencing severe repetitive stress injuries in my wrists, I used the paperback formatting service from Damonza (more on them below in the cover design section) for the publication of Structuring Your Novel.

These days, I’m back to formatting most of my books myself. I understand and enjoy typesetting, and I like the extra degree of control it gives me over the product’s appearance. Plus, it’s cheaper on the whole.

However, I recommend authors take on any kind of design work only if they truly understand the principles of the job.

If you can’t afford a professional service such as Damonza’s, you might check out Joel Friedlander’s Book Design Templates. These pre-formatted templates can be used in Microsoft Word and will produce files that can be successfully uploaded to KDP and other publishing nodes. I haven’t used the templates personally, but they look great and the idea is clever and helpful.

5. E-Book Formatting

I have hired a couple e-book formatting specialists over the years (including Damonza), and although I was always happy with the end product, what I didn’t like was that I wasn’t able to revisit the finished files and make changes as necessary. Since I frequently need to tweak something (such as updating links), I need the autonomy of being able to access and change the files at will.

For this, I use Scrivener to format and convert my books into e-book formats. Scrivener does the job admirably, but it’s definitely not the single best e-book design and conversion option. It’s also not the easiest conversion system to master, although once you get the presets configured, you shouldn’t have to figure it out again.

While Scrivener works just fine for publishing to Amazon and most other sales platforms, Smashwords is notoriously more finicky about the files it will accept. For Smashwords versions of my e-books, I usually purchase a Fiverr gig. Most recently, I’ve used Kimolisa.

6. Cover Design

Among the many jobs most authors should not do themselves, cover design tops the list. Although there certainly are authors who are also skilled and educated in visual design, most of us are not. I myself know just enough to be dangerous (which I proved with some early book-cover designs). These days, I rely on the pros at Damonza to design all my covers. If you’re interested, they offer a 5% discount when you order through my affiliate link using the code HWBA5.

7. Illustrations, Infographics, and Maps

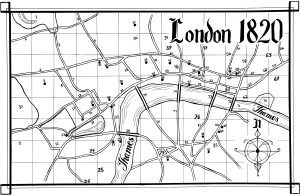

Whenever I need an image—whether it’s an illustration (such as those in Storming) or a map or an infographic (such as those the Creating Character Arcs Workbook), I turn to Joanna Marie Art. I’ve dabbled with other creators, most via Fiverr, but I like the consistency of Joanna’s work.

8. Website Design

Like most blogs these days, mine runs off WordPress. Both Helping Writers Become Authors and my author site KMWeiland.com were professionally designed by Varick Design, for whom I can’t express enough appreciation as an amazing company. In addition to their great design work, they’ve also helped me through many a technical question.

9. Website and Domain Hosting

I’ve hosted the sites at a number of places over the years. Due to the current size and volume of traffic, they’re now parked with Siteground. I use Start Logic for domain registration. I don’t remember why I started using Start Logic; pricing probably. Siteground came recommended by Varick Design.

10. Image Sourcing, Editing, and Design

I source most of the images I use for the blog and social media from Pixabay, which offers free stock photos. On the occasions when I need something I can’t find on Pixabay, I purchase photos from iStockphoto.

I do most of the editing myself in Photoshop Elements. Occasionally, if I need something out of the ordinary, I will use the free template service Canva.

11. Podcast Recording, Editing, and Hosting

I record my podcast using a Blue Yeti mic (which I’m probably going to be updating sometime soon) and the free recording software Audacity. I’ve just recently started hosting it on Libsyn, both to take the stress of traffic off my own site and to distribute the episodes on more platforms.

If you’re a longtime listener, you may have noticed an improvement in audio quality within the last few months. This is thanks to PodTone, with whom I consult on how to improve the sound while recording (hence, the coming mic upgrade). They then master the finished podcast for professional-level sound quality.

They’re just starting up business, but are currently taking on some testers at reduced rates. They don’t yet have a website up and running, but if you’re interested in their services, you can email them at info [at] podtone [dot] com. Be sure to mention my name or Helping Writers Become Authors in the email body.

12. Social Media Scheduling

For scheduling routine daily tweets and Facebook posts, I use HootSuite.

13. Email Campaign Manager

My mailing list is hosted by Campaign Monitor. I was fortunate to land with them from the very beginning, and I’ve never looked back. They offer lots of templates and other easy-to-use tools for managing mailing lists on a professional level.

I use OptinMonster for popup subscription boxes that offer e-books as a thank-you when people join the mailing list.

14. Onsite Selling Platform

In addition to publishing my books via KDP, Nookpress, Smashwords, and Kobo Writing Life, I also sell my books and software directly off my site. For this, I use the e-commerce platform Selz, which processes all payments.

15. Marketing

Marketing is probably the most interesting topic amongst writers looking for resources. Over the years, I’ve tried this and I’ve tried that—more things than I can even remember. For the most part, I feel my platform has been built on the time and sweat of weekly content creation and social media interaction. I’ve yet to discover a magic pill.

I have yet to tackle (much less conquer) advertising (although I did watch and appreciate Dave Chesson’s free Amazon ads course). The only marketing service I’ve returned to repeatedly is Penny Sansevieri’s Author Marketing Experts, which I’ve used primarily for updating keywords on Amazon and promoting freebies or discounts.

***

So there you have it—all the professional writing resources I currently use. With any luck, you’ve find something here you didn’t know about that will prove helpful producing and marketing your work. If you have any questions, feel free to ask in the comments.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What professional writing resources do you use and recommend? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post The Professional Writing Resources I Use for All Parts of the Writing and Publishing Processes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 17, 2020

Thoughts on How to Be Critical of Stories in a Way That Makes a Difference

Some stories make me so mad.

Some stories make me so mad.

It’s not just that these stories are all technically “bad” in some way. Indeed, there are plenty of deeply bad stories I pass on by with hardly a second thought. There are even plenty of “bad” stories I find amusing, or even some I adamantly like for any number of personal reasons.

But then there are the memorable few that stick in my craw. In these instances, I go from being able to offer a thoughtful, logical, unemotional critique of why the story didn’t work objectively, or perhaps why it didn’t work for me subjectively, to looking frantically for my flamethrower and machete.

I’ve been pondering this phenomenon for a few months, ever since experiencing yet another movie that submarined yet another of my favorite franchises. I wasn’t just disappointed; I was really upset. And yet, as an author myself, I also know what it feels like to be on the other side—a hapless creator facing down the emotional firestorm of a reader who gave (maybe) ten hours of their time to a story it took years of careful labor to create. If you’ve ever been the creator in that scenario, you’ve no doubt felt the sting of unfairness that someone should react with such strong emotions of ownership to something that is, after all and always, yours.

And yet they—readers and viewers—do react strongly. As readers and viewers ourselves, we all understand exactly what they’re feeling. In these instances of extreme criticism, the response isn’t simply to technical problems within the story; it’s also fueled by a deep sense of disappointment, betrayal even.

Recently, one of my favorite podcasts, Personality Hacker, offered a discussion on “How to Be a Good Critic,” which started out referencing movie reviews and ended up delving into the broader “criticism culture” in which we all swim these days when we brave the waters of the Internet. Listening to the hosts’ thoughts helped congeal some of my own maunderings.

What is it about some stories that unleash our inner critics’ wrath so strongly? Is that a bad thing or a good thing?

Where does this reality put those of us who are creators ourselves? Does our emotional criticism of others’ stories make us hypocrites when we know how much it can hurt? Or does the fact we are writers give us more right to be critical?

Whatever the case, can we possibly take what is, by its very nature, a negative act and turn it into a positive force for driving our own creativity?

4 Types of Stories That May Trigger Your Inner Critic

First, we have to recognize the different reasons a story may trigger our inner critics.

1. Stories That Are Technically Unsound

For starters, there are stories that are just plain bad—objectively, obviously, undeniably bad. Whatever their good points, they simply don’t work. The story structure is off or nonexistent. The plot is full of logic gaps. The characters are stereotypes who lack dimension and sound motivations. Or maybe the finer technique of presentation is lacking: the grammar or punctuation, the flow of the sentences, etc.

Stories that are really messed up on a technical level are rarely stories that trigger a massive critical response. We see at a glance these writers have no idea what they’re doing (and presumably don’t even know they don’t know). We pass on by without a second thought, much less an emotional response—in much the same way we would disregard a child’s scribbles.

Ironically, stories that are almost good are much more likely to trigger the emotional response. A story that aced everything except a major plot hole or that gripped us all the way through until it failed to stick the landing—that’s the story that will have us tearing our hair out.

2. Stories That Are Psychologically Unsound

Sometimes the problem with a story is harder to put your finger on. The structure, character arcs, theme, writing, et al., all seem skillfully rendered. And yet we’re irritated. Often, this is because the story fails to ring true on a deeper psychological level. Put simply, it fails archetypally.

Even if we can’t articulate exactly what’s wrong with these stories, we are still instincively bothered. We know in our gut something doesn’t ring true. The general idea of the story may not even be at fault. Rather, the execution of believable cause and effect or character development may fail to bear out proper archetypal beats that resonate in our deeper, often unconscious understanding of life. As Julia Cameron quotes Adrienne Rich in The Artist’s Way:

The unconscious wants truth. It ceases to speak to those who want something else more than truth.

Stories are a symbolic representation of life. As such, they must work on a level deeper than conscious logic. This is one of the basic reasons recent reboots (of just about any popular series you can think of) fail so badly in comparison to their legendary and beloved ancestors.

3. Stories That Offend Your Worldview

Another obvious reason our inner critics sometimes come raging out of their caves is that our worldviews have been offended. This is the most subjective of all the reasons. Especially in these polarized times, stories are often judged less on their native worth and more on whether or not they fall in line with any given viewer/reader’s beliefs about what is socially and morally right.

Stories that speak honestly will always offend someone. As Studs Terkel famously said:

Just about every book contains something that someone objects to.

However, I believe any story that triggers outrage on this level is ultimately (and probably most potently) an offender in one of the other categories. The best stories resonate so deeply they sneak past our defenses and change our hearts before they change our minds. This is only possible with stories that ring true on every level—technically, logically, and archetypally.

4. Stories That Hinder You Rather Than Help You

Finally, there’s the category of frustrating story that may, in fact, be technically perfect. It strikes notes of universal truth. It may either agree with your worldview or prompt you to thoughtfulness about an opposing view. And yet, it still doesn’t work for you on a deeper, more insidious level.

These are the stories that offer you either nothing of value in your life—or offer you something of negative value. I’m not just talking about stories that are depressing, but stories that—subtly or not—offer messages of despair rather than messages of hope. These are stories of destruction, not stories of construction.

We all know what these look and feel like—because they’re everywhere right now. Even if we don’t immediately understand why we’re upset about a story (and so end up groping around for a more technical reason), our response may be a lashing out against messaging that make us feel disempowered, hopeless, and cynical.

Finding the Gifts “Bad” Stories Have to Offer You (or, What You Can Do About Them)

I don’t like getting mad about stories. Beyond the simple fact that I would have preferred to have been glad about the story rather than mad, the negativity of über-criticism is a pretty icky feeling. Verbally blasting a creator for trying to put something out in the world (even if that something was objectively malformed) neither remedies the existing story’s problems nor counters them with positive solutions.

As writers (and humans), it behooves us to offer as much grace as we can to our fellows (because try as we might, we may write something just as “bad” on our next outing). However, it’s also incumbent upon us to evaluate both our responses to the bad stories and the stories themselves. Any time we experience an emotional response to something, we can think of it as our guardian muse tapping us on the shoulder and telling us there’s something here for us to learn. To writers, lessons are always gifts.

The next time you get mad about a story, consider why and what you can take away from it. There are two aspects to this: your logical response and your emotional response. Both are important to bettering your own writing.

Learn to Articulate: Why Is This Story Logically Bad?

Everybody’s a critic, as they say. But very few people—even amongst the creative community—understand what they’re criticizing well enough to be a good critic. Everyone is qualified to say whether or not they liked something. But writers must strive to understand why we disliked a story.

What about it didn’t work?

Where did the story craft fall apart?

Why was suspension of disbelief endangered?

Why did the thematic message seem so on the nose?

The more you understand about story theory and technique—and the more you practice them in your own stories—the more equipped you will be to recognize, analyze, and learn from the mistakes of other writers.

>>Click here to read: How to Grow as a Writer: 5 Logical Steps

Emotion As a Different Kind of Logic: Why Are You Emotionally Upset?

A story may elicit an emotional reaction—whether positive or negative—without the reason being immediately obvious. The story may initially seem excellent on a technical level, and yet you feel violently disconnected from it.

Emotion, in itself, isn’t logic. In fact, emotion can drive us to all kinds of wildly illogical reasons for why something is supposedly bad or good. That said, emotion always points to something. Never ignore an emotional response. But always seek to understand the truth of what it is. Most of the time when something triggers our harshest criticism, it is rooted in one of the following feelings:

1. Disappointment: The story let you down. You invested more of yourself in it than just your time and money; you trusted the author enough to enter their shared dreamspace. And that author let you down in some way—whether objectively or subjectively.

2. Disempowerment: You can’t change the story because you didn’t write it. And you can’t change the message the story is asking you to accept. The story left you impotent to respond, save through criticism.

3. Defensiveness: The story tried (and perhaps partially succeeded) to change you and your world—but not in a way you appreciated. It might have triggered deep-seated identity issues, either through its content or because you too are a creator (e.g., the emotion is rooted in fear that you may produce something just as suspect) or because you are part of a fanbase with certain expectations.

So You’ve Figured Out Why the Story Was Bad—Now What?

Analyzing the how and why of your negative reaction to a story may or may not help you calm down and return to a more rational and less attached mindset. Regardless, what’s your next step?

At this point, you should have gleaned the insights you need to at least offer a worthwhile critique of the story. You aren’t simply basing your criticism in your own emotional response, but in the reasons behind it. Depending on the medium, it’s possible publishing this critique may offer worthwhile insight into correcting the problems and moving forward. Or not. It might just add to the noise. The Dalai Lama is quoted as saying:

Being aware of a single shortcoming within yourself is far more useful than being aware of a thousand in someone else.

Take what you’ve learned about your reactions to this story and apply it to your own writing. Identifying why a story offended you on a such a deep level tells you more about yourself than it does about the offending story.

Its technical missteps become guideposts for helping you write a more technically sound story of your own.

Its psychological inaccuracies give you the opportunity for both personal growth and a more conscious approach to the deeper underpinnings of your own writing.

Its shallow approach to sharing a worldview (whether you agree with it or not) gives you insight into the deep necessity for passion, truth, cohesion, and resonance if you’re to share truths of any worth with others.

Its deeper message—whether of negativity and destruction or positivity and construction—helps you refine what you believe about the world and what you want your stories to say about it.

***

Addicting as criticism can be—especially when driven by authentic and powerful emotions—it is only truly useful when we move past its inherent negativity to build upon what lessons it offers. When a story lets us down, it is so easy to get lost in the victimizing mentalities of disappointment, disempowerment, and defensiveness. But as long as we’re willing to do the work of following the signs, these emotions point the way uphill to a future of better stories.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What positive takeaways have you gleaned from being critical of stories that made you mad? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post Thoughts on How to Be Critical of Stories in a Way That Makes a Difference appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 10, 2020

Writing Legal Fiction: 4 Research Tips

On television crime dramas, DNA comes back in three minutes, crimes are solved in less than forty-two minutes, and defendants always confess to everything right there on the stand in front of judge and jury. While I can see the entertainment value in this type of show, I often want to hurl my remote at the television. Why? Because none of it is an accurate portrayal of the judicial system and how it works. As someone who’s worked in the legal field for over two decades, it’s beyond frustrating.

On television crime dramas, DNA comes back in three minutes, crimes are solved in less than forty-two minutes, and defendants always confess to everything right there on the stand in front of judge and jury. While I can see the entertainment value in this type of show, I often want to hurl my remote at the television. Why? Because none of it is an accurate portrayal of the judicial system and how it works. As someone who’s worked in the legal field for over two decades, it’s beyond frustrating.

What Is Legal Fiction?

Before we talk about the how-tos of writing legal fiction, let’s first define the genre.

Like Father, Like Daughter by Christina Kaye

Legal fiction is a genre that revolves around the legal system in one way or another. While protagonists don’t necessarily have to be lawyers, they should somehow be involved in the justice system. For example, they could be judges, bailiffs, court reporters, or paralegals.

In my award-winning novel Like Father, Like Daughter the protagonist is a paralegal. Working in the legal field for many years gave me all the tools and information needed to write a compelling and realistic legal suspense. Likewise, it gave my protagonist all the information and tools needed to investigate and solve the crime in question.

Legal novels are typically set (at least in part) in a courthouse or other peripheral locations central to the justice system, such as jails, lawyers’ offices, etc.

The most popular type of legal fiction comes in the form of mysteries, suspense, and thrillers.

If you’re wondering if there’s a market for legal fiction, I have a prime case study which proves legal fiction can make a killing (pun intended): John Grisham has sold over 250 million books, makes an average of $50 million per year, and his net worth is a whopping $350 million.

We can also find plenty more literary works set in the legal world. In her post “Beyond John Grisham, a Guide to Legal Fiction,” Terri Frank writes:

Presently, legal fiction is evolving into so much more than it was when John Grisham’s The Firm hit bestseller lists twenty-five years ago…. Readers are gravitating to books with more diversity among attorneys and clients, smart humor and dialogue, and plots that enlighten them about contemporary legal issues.”

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Remember To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee? Atticus Finch, the protagonist in this classic, is often cited by many attorneys as their inspiration for becoming a legal professional.

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens

More recently, one of my favorite legal reads is Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens. The courtroom drama doesn’t play out until the second half of the book, but the way Owens portrayed the courthouse in the Deep South, as well as the myriad of interesting, well-developed, even quirky characters, was so accurate, I could envision the entire trial in my mind.

So, while thrillers are more commonplace than other subgenres, any book can have a central theme surrounding the justice system.

4 Tips for Writing Legal Fiction Readers Will Love

Let’s talk about ways you can make your legal fiction interesting.

1. Use Trials as the Compelling Plot Devices They Are

Courtrooms offer great plot devices because protagonists must win/save the day/succeed before trial ends. Why? Because criminal defendants who are acquitted cannot be retried, due to the double jeopardy rule.

The outcome of a trial, whether it results in acquittal or conviction, can also be used as a beginning point for a legal novel. Stephen King’s Shawshank Redemption begins with protagonist Andy Dufresne being convicted of his wife’s murder.

2. Pull Your Cast of Interesting, Unique Characters From a Courthouse

Every work of great fiction includes a cast of colorful and compelling characters. Legal thrillers are no different. A great place to find and mimic unique characters is the courthouse building. There you can find judges, lawyers, jurors, bailiffs, sheriffs, reporters, courtroom observers, and of course paralegals. For example, the movie Erin Brockovich centered around an unwitting, unlikely heroine who stumbled into the paralegal profession and wound up solving the case and saving the day.

3. Ensure You’re Accurately Portraying the Justice System

When writing legal fiction, you must get the facts right. The legal community will know when you’ve got it all wrong. Even lay readers will be able to tell when you aren’t clear about your character’s chosen profession.

Research the facts about how the legal system works. When I say research, I don’t just mean perusing the Internet and reading Wikipedia (although there is a wealth of information out there in cyberspace). I’m referring to actual, hands-on, in-person research. Find an attorney willing to answer questions and tell you exactly what you need to know to pull off a convincing legal thriller.

Further, ask the attorney for a copy of a deposition transcript (redacted, of course). You will learn a lot from a deposition, including how objections really work, as well as legal terminology and attorney lingo.

Even better, call your local court clerk and ask when the next civil or criminal trial will be held. Trials are open to the public, so you can sit in the gallery and take extensive notes on everything you hear and observe. I truly believe this is the best way to learn how the legal system works.

4. Accurately Portray Your Legal Professional

You must also be clear on what it’s really like to be an attorney (or other legal professional). Write up a list of questions to help you get to know the profession and the professional in a way that will help you create a more compelling and believable legal protagonist. Ask your helpful attorney questions like:

What is a typical day for you in the office?

How often do you really go to trial?

How do you prepare for a trial?

What are some of the biggest stressors of being an attorney?

More specifically, when you have questions about the technicalities of the law, ask your attorney those questions. Keeping in mind laws vary from state to state unless they fall under federal codes, ask you attorney things like:

What is the statute of limitation on robbery?

What are the potential sentences for murder in X state?

What are the rules on discovery?

How would you file an appeal?

How are criminal charges brought after arrest?

There’s no better way to research your protagonist’s chosen profession than to actually get to know someone with the same job.

***

Whether you choose to write a legal mystery, suspense, thriller, or even a more literary novel, it’s imperative you understand how the justice system works, what settings you’re going to be using, and how your characters would conduct themselves in real life. This will help you in writing legal fiction that is all the more compelling and convincing.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions? Have you ever tried writing legal fiction? Have you ever written a lawyer or a trial into a story of a different genre? Tell us in the comments!

The post Writing Legal Fiction: 4 Research Tips appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 3, 2020

6 Steps to Create Realistic (and Powerful) Scene Dilemmas

Scenes are the building blocks of your story. As go your scenes, so goes your story. If the scenes present a solid chain of deliberate structure, that’s what your story will be. But if too many scenes lack focus or dramatic impetus, so will the story. Every aspect of scene structure is important. Any aspect that is accidentally overlooked can throw off the balance of the entire narrative. But of all the many aspects of scene structure, those that are among the most powerful are also the easiest to overlook: scene dilemmas.

Scenes are the building blocks of your story. As go your scenes, so goes your story. If the scenes present a solid chain of deliberate structure, that’s what your story will be. But if too many scenes lack focus or dramatic impetus, so will the story. Every aspect of scene structure is important. Any aspect that is accidentally overlooked can throw off the balance of the entire narrative. But of all the many aspects of scene structure, those that are among the most powerful are also the easiest to overlook: scene dilemmas.

First, a quick refresher on classic scene structure (which I discuss in much more depth in my book Structuring Your Novel):

Part 1: Scene (Action)

a. Goal (character wants and tries to get something that will aid in reaching the overall plot goal)

b. Conflict (character is met with an obstacle to obtaining the scene goal)

c. Outcome/Disaster (character’s attempt to reach the goal meets some end, which is usually “disastrous” in the sense that the character either fails to achieve the goal or achieves only part of it)

Part 2: Sequel (Reaction)

a. Reaction (character reacts to the outcome)

b. Dilemma (character must now figure out how to overcome the new complications that resulted from the last attempt while still moving forward toward the main plot goal)

c. Decision (character decides upon a new scene goal as a more effective response to the new complications)

>>For a complete discussion of scene structure, see my series How to Structure Scenes in Your Story.

Take note of our little friend the dilemma in section 2.b. At first glance, scene dilemmas can seem either extraneous (how, after all, is the dilemma different from the disaster?) or too straightforward to offer much interesting drama (readers just read about the disaster after all, so do they really need to see characters rehashing it in a dilemma segment?).

There’s truth to both these reactions. But another truth is that within the dilemma part of any scene resides the opportunity to find the true realism and drama that mimics our own real-life processes.

Let’s take a look!

Scene Dilemmas Are About… Emotion

We face many dilemmas in our daily lives. Some are so small and easily resolved we barely notice they are dilemmas.

For example, there’s currently a big pothole in the dirt road in front of my house. Every time, I drive down that road to reach the highway, I am confronted with the dilemma of this huge bump in the road. So what do I do? Do I spend the mental equivalent of pages upon pages recognizing the noxious jolt this hole could give my car? Do I go over my options for confronting the hole? Do I then finally decide upon my course of action in a deeply dramatic way?

Not really. I see the pothole. I turn the steering wheel to avoid the pothole. Dilemma solved.

But other dilemmas aren’t so easily solved. They require a bit of thought—or even a good deal of anguish.

One Question a Day: Five-Year Journal

For the last seven years I’ve enjoyed keeping a “Question a Day” journal. It’s a five-year journal (I’m on my second one), which allows me to answer the same question on the same day for five years. As time goes on, it’s interesting to look back at how I’ve answered the question differently from year to year.

Questions such as “what are you most worried about?” are particularly enlightening. Almost inevitably, I find that the thing I was most worried about last year or the year before that or five years ago is something I’d since forgotten. It’s a moment of Oh yeah, I was really fussed about that, wasn’t I?

Not only has seeing this provided me perspective on how useless and unnecessary worrying usually is, it has also given me perspective on how big dilemmas often seem when we’re in the midst of them.

As writers, we can take note of this in crafting scene dilemmas. Too often, we’re in such a hurry to get our character to the big scenes that we forget the character doesn’t know he’s not already in the big scene. He’s immersed in the present moment. As he’s taking a breather to process what just happened and what he gained and/or lost in his most recent effort, he’s experiencing emotions. Maybe there’s major adrenaline or endorphins still pumping. Or maybe it’s just a twist of anxiety in his stomach—-which he doesn’t want to acknowledge but can’t quite escape (you know the feeling).

The point is that whatever he’s feeling, he’s feeling it. Think about the scene from the classic western The Magnificent Seven, in which the heroes begin to understand the current concerns of their antagonist, the bandit chieftain Calvera:

Calvera isn’t worried about food for winter. He’s worried about the food his men haven’t eaten for the last three days. The price of corn is going up. They’re starving.

Calvera’s plot goal started out (and continues to be) about feeding his men for the winter. But at this point, now that his back has been put against the wall, that’s the last thing on his mind. Now he’s just worried about the present situation—his hungry, mutinous men.

A 6-Step Checklist for Getting the Most From Your Scene Dilemmas

In a year (or even a day), your character may no longer be feeling the urgency of any given scene dilemma. But within the scene itself, the dilemma matters. (If it doesn’t matter, it isn’t important enough to be a scene dilemma—a realization that should take you back to reconsider your previous scene outcome/disaster. If it does matter, then you have to make sure you’re really inhabiting that emotional space as a writer.)

Here are six steps you can use to evaluate scene dilemmas. This approach will help you take full advantage of important scene dilemmas—and, just as notably, it will help you determine which scene dilemmas are important.

1. Own the Scene’s Emotional Space

Don’t let yourself brush over scene dilemmas. Realism in fiction is the result of solid cause and effect, and solid cause and effect is grounded by your character’s reactions to events. Don’t rush through any reaction scene just to get back to “the good stuff” (because it’s all supposed to be good stuff, right?). Whenever anything happens that complicates your character’s journey toward the plot goal, there must be an emotional response.

Depending on the severity of events, the character may be experiencing emotions that range from annoyance to delight to terror. But he’s feeling something (the essence of the “reaction” part of the sequel, which walks hand in hand with the dilemma). More than that, the feeling will exacerbate or be exacerbated by the fact that what just happened isn’t a closed incident. The story’s not over. A dilemma, after all, means the character now inhabits that emotionally vulnerable place of knowing she’s about to have to make another choice.

2. Put Yourself in the Character’s Skin

Don’t write the first emotional response that comes to mind. It’s important to vary your character’s emotional reactions throughout the story. After all, if he’s angry all the time, that’s just going to get boring. But it’s even more important to make sure the emotional response is true.

Use that writer’s imagination of yours to project yourself into the character’s skin. What would you be feeling in this situation? And don’t just think about the emotions themselves. What would you be feeling physically if you were confronted with this dilemma? Think particularly about your stomach and solar plexus. Emotions manifest strongly there, even when we’re not consciously acknowledging them.

3. Rate the Intensity of Your Character’s Emotional Response

As noted in the example about my pothole, not all scene dilemmas are created equal. Just as in life, the progression of your story will include dilemmas that span the gamut from trivial to life-changing. Your character’s reactions must also span that gamut.

Usually, the character’s reaction will be in direct proportion to whatever is at stake in the scene’s dilemma. But the character’s personality will also be a factor. Dangerous circumstances that might tie up most of us in nervous knots will be the very situations where other characters are most comfortable.

4. Determine How Best to Dramatize the Character’s Response

Remember the (general) rule: . This is a challenge to show, not tell, what your character is feeling. Saying she’s nervous or even that “her stomach is in knots” is the easiest but often least effective way to convey a character’s emotional reaction.

Rather, take a page from the movies and try to visually represent the scene’s emotional weight—preferably in ways that advance the plot by either adding information or contributing to the character’s subsequent scene goal. You can also make use of subtext in dialogue: have characters react to what’s happened by deliberately not commenting on it.

5. Avoid Melodrama

In your quest to take full responsibility for the emotional weight of all your scene dilemmas, be careful not to go overboard in the opposite direction. Turning every scene dilemma into an existential crisis will strain your readers’ suspension of disbelief. Not only will this fever pitch of emotion eventually grow boring thanks to a sheer lack of variation, it will inevitably make your characters and your story appear ludicrous.

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

Note the difference between downplaying the drama of emotion versus just downplaying the emotion altogether. Look to master works of subtext such as All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr for how scenes of tremendous emotional weight can be portrayed all the more powerfully by writing around the emotion.

6. Summarize Small Dilemmas

At the beginning of the post, I mentioned that some scene dilemmas will seem either too extraneous or too straightforward to bother dramatizing. You will have to use your writer’s instinct to determine which scenes fit these categories and then downplay them appropriately.

Proper scene structure—in which all six parts of the scene are in place—is important for creating dramatic flow and narrative momentum. But this does not mean every part of the scene must be fully fleshed out. Sometimes parts of the structure can be implied or summarized without losing any dramatic power. Recognizing when this is appropriate largely comes down to developing a good sense for pacing. If you’re concerned you may be summarizing too much or summarizing the wrong scene, consider whether the character is expressing an emotion that qualifies as one of the following:

a) different from what might be expected.

b) different from that expressed in the last scene.

c) directly contributive to a change in mindset or motive for the following scene.

d) an emotion readers will enjoy experiencing alongside the character.

If any of these jump out at you in relation to a scene dilemma, you’ve probably found emotional heft that’s worth fully dramatizing.

***

Scene dilemmas (and reactions and decisions) can often be the meatiest and and most fulfilling parts of a story. Although the more action- and plot-oriented scenes are just as important, don’t forget that much of the character development will happen in the reaction phase of the scene sequel. Have fun with them!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s your favorite thing about writing scene dilemmas? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/scene-dilemmas.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 6 Steps to Create Realistic (and Powerful) Scene Dilemmas appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 27, 2020

Unboxing Review: Writer’s Medic Bag From Galen Leather Co.

Two things I love: taking my writing on the go (whether outside or to a coffee shop) and beautiful writing accessories. So I’m excited for this opportunity to review a handcrafted carrying case made just for writers, from the family-run company Galen Leather in Turkey.

Two things I love: taking my writing on the go (whether outside or to a coffee shop) and beautiful writing accessories. So I’m excited for this opportunity to review a handcrafted carrying case made just for writers, from the family-run company Galen Leather in Turkey.

The company offered me my choice of products to review—which was a super-hard choice since everything on their site is gorgeous. They handcraft a wide array of leather accessories, everything from notebook covers, pen cases, phone and tablet cases, wallets, mousepads, and more. I was immediately grabbed by their premier product, the clever and lovely Writer’s Medic Bag.

From their site:

The Writer’s Medic Bag is the best bag for writers. Its unique design, inspired from a traditional medic messenger bag, allows you to carry all your writing essentials with you wherever you go. For loyal fans of Galen Leather who have amassed quite the leather collection, you will fall in love with this leather writer’s bag. It’s the perfect way to keep everything together and take them with you on your next adventures. There’s enough room for your leather journals, pens, ink, pen cases, notebooks, brass stationery and more. The Writer’s Medic Bag is available in Crazy Horse Forest Green and Crazy Horse Tan.

Particularly because the product was packaged so beautifully, I wanted to share an unofficial unboxing video (unofficial because I’d already opened it and filled it with my own writing utensils).

A few of my favorite features…

The bag stands upright when both open or shut.

The front area offers small loops to hold pencils and pens, as well as some larger loops to accommodate other items, including one that should be big enough for a small notebook or your phone. (I’m currently using it to hold my ergonomic pen.)

The front flap features a multitude of pouches, including one with a zipper. I’ve used this section to hold my earphones, as well as blank note cards, and sticky notes. This would also be a great place for credit cards or library cards, if you want to consolidate bags when writing in public.

The back pocket is large enough to hold my iPad (or perhaps a small laptop) as well one big notebook or several smaller ones.

There’s also handy place to clip a key chain.

And there’s an optional strap you can attach/remove from the back.

The bag comes elegantly packaged in a sturdy lidded cardboard box, with a protective drawstring bag.

The craftsmanship is wonderful. The leather is butter soft and smells amazing. I can see this lasting me the rest of my life.

Beyond just being lovely and fun, the medic’s bag is perfect for me, since I write longhand quite often, like to be able to take my writing on the go, and deeply appreciate having a tidy place to store everything I need.

The bag gets five stars out five from me, along with my thanks to Galen Leather for giving me the chance to review it and add it to my writing routine!

If you’re interested in the bag or any of the other products from Galen Leather, you can check out their website here.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you like to take your writing on the go? What writing tools (notebook, pen, etc.) do you generally take with you? Tell me in the comments!

The post Unboxing Review: Writer’s Medic Bag From Galen Leather Co. appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 20, 2020

2 Different Types of the Lie Your Character Believes

The Lie Your Character Believes. It’s the atom waiting to be split, the bomb waiting to go off, the change waiting to happen in your character’s life. Even when hidden beneath layers of plot and theme, the Lie Your Character Believes is your story. You know this, of course. But did you know that sometimes there are two types of the Lie Your Character Believes?

The Lie Your Character Believes. It’s the atom waiting to be split, the bomb waiting to go off, the change waiting to happen in your character’s life. Even when hidden beneath layers of plot and theme, the Lie Your Character Believes is your story. You know this, of course. But did you know that sometimes there are two types of the Lie Your Character Believes?

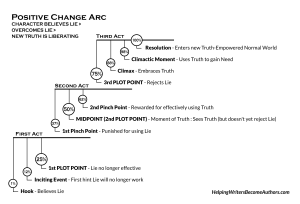

The Lie Your Character Believes is the central cog in your character’s arc. This is so simply because the Lie is the reason change needs to happen—and therefore the reason there’s a story to tell in the first place. The Lie will inherently be opposed by a related Truth, and together they create the foundation for a cohesive and resonant plot and theme. (Note that in some stories, the protagonist is the one who believes the Lie; in others, the protagonist believes the Truth but is surrounded by supporting characters whose actions are informed by opposing Lies.)

Truly, there are as many different kinds of Lies as there are, well… lies. If it ain’t true, it has the possibility of driving character change in some way. The Lie might be something as trivial as Aunt Bea’s belief that her homemade pickles can win a blue ribbon when really they taste like kerosene, or it might be something as monumental as Javert’s belief that mercy and justice are mutually exclusive.

The shorthand for this is that there’s no limit on what kind of Lie Your Character Believes—as long as it drives the plot and engineers the theme. However, I feel it’s helpful to examine two particular categories into which your characters’ Lies might fit. Seeing the difference can help you know which is right for your story—or whether you might get extra mileage by dramatizing a related Lie for each category.

2 Types of the Lie Your Character Believes: Inner and Outer Lies

If you start examining Lies in popular stories—or your own stories—you’ll notice two different manifestations. Sometimes the Lie is one that exists mainly within the character’s inner self, driving the inner conflict. Other times, the Lie exists mainly within the character’s outer world, driving the outer conflict. This can be a tricky distinction, since the inner Lie will often affect the outer conflict and vice versa (after all, this is the essence of character driving plot).

We can think of this distinction, in very general terms, as the difference between a character-driven Lie and a plot-driven Lie. Again, this is a fine line, since the best stories are always strong in both plot and character. But you can easily spot the differences by examining stories that fall at opposite ends of the spectrum. Plot-driven stories often focus primarily on an outer-world Lie such as Hunger Games‘ Lie that “oppressive government is necessary” or Jurassic Park‘s Lie that “science should always be advanced.” Character-driven stories usually focus on an inner Lie, such as “men and women can’t be friends” in When Harry Met Sally or “money is the measure of worth” in A Christmas Carol.

An inner-world Lie will affect the character’s outer world, sometimes even to the point of becoming the outer world’s Lie. And vice versa, an outer-world Lie will likely become crucial to the character’s inner conflict and self-estimation.

The distinction is important not so much because of how the Lie manifests in the story as it is because of where the Lie originated. Where did this Lie come from? Who (or what) gave this Lie to the character? And what do the answers mean for the character’s motivations and ultimate arc within this story?

Let’s take a look.