K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 27

December 7, 2020

10 Best Books to Buy a Writer For Christmas

All the lists of Christmas gifts for writers are good at highlighting unique and fun (and sometimes useless) gift ideas. But the truth is: writers are easy to buy for. Just wrap up a bunch of books. Almost any book will do, but if you’re wanting to get specific (for yourself or a writer on your list), here are what I currently consider the 10 best books to buy a writer for Christmas.

All the lists of Christmas gifts for writers are good at highlighting unique and fun (and sometimes useless) gift ideas. But the truth is: writers are easy to buy for. Just wrap up a bunch of books. Almost any book will do, but if you’re wanting to get specific (for yourself or a writer on your list), here are what I currently consider the 10 best books to buy a writer for Christmas.

Over the years, I have read more writing-craft books than I can count, which means I’m undoubtedly leaving a few gems off the following list. But these 10 are the ones I remember. They’re ones that were formative in my own understanding of the craft and/or deeply inspiring. They all get an unabashed five stars from me. If you or another writer you know hasn’t read them yet, now’s the time to pop them onto your last-minute Christmas list.

10 Best Books Books to Buy a Writer for Christmas

They follow in alphabetical order. (Please note these are affiliate links.)

1. The Anatomy of Story by John Truby

This book was one of the first that truly shaped my understanding of story theory. It is complex and deep with insight. Although it is intended for screenwriters, it offers just as much to novelists. I suppose it’s been around long enough now to almost be considered a classic—and I do.

2. The Emotional Craft of Fiction by Donald Maass

After reading this last year, every time I see the cover somewhere I want to stand up and cheer. It is full of practical, hands-on advice (as Maass’s books always are) for crafting deep and emotionally resonant fiction. More than that, it is a rousing rallying cry to substantial fiction. (I talked about my gleanings from it in this post.)

3. Light the Dark edited by Joe Fassler

This is an anthology of essays from a number of notable writers, all of whom specifically address their own writing inspirations. As you would think, it is inspirational. To hear so many great writers discoursing on the power and meaning (and sometimes difficulty) of writing fiction feels both exciting and encouraging. (After reading it, I posted about this book quite a bit here and here and here and here and here and here.)

4. The Moral Premise by Stanley D. Williams

This book was formative for me in seeing the connection between plot, character, and theme. Williams does a beautiful job of tying theme in with the engine that makes it run: character arc. He further builds that into the foundation of structure to create the complete package. His writing can be a little academic at times, but any complexities are well worth the time and brainpower required to work through the information.

5. The Secrets of Story by Matt Bird

Bird has X-ray vision when it comes to the mechanics of story (mostly because he’s systematically analyzed hundreds of movies and TV shows on his website). His book cuts through the fog and gets to the pointy ends of all things story. Readable, insightful, and in many ways a breath of fresh air, this has been my favorite writing craft book of late.

6. Story by Robert McKee

This book is a titan. It too is aimed at screenwriters, but it too is ultimately more about the theory that underlies story itself rather than the mechanics of a specific medium. This book deserves its tremendously broad title, because that’s exactly what this book is: a discussion of story. It offers theory and practicality all wrapped up into one module.

7. Techniques of the Selling Writer by Dwight V. Swain

Although dated in some of its presentation, this book is a gold mine of practical tips. Swain’s advice on scenes and sequels and motivation-reaction units have long since entered the writing canon, and his thoughts on structure, character, and the writing life in general are invaluable.

8. The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson

Obsessed with archetypal character arcs? Want more than just the (rightly beloved) Hero’s Journey? Me too! In this book, Hudson offers a deeply wrought discussion of the feminine partner arc to the Hero’s Journey—what she calls the Virgin’s Promise. This book has transformed the way I look at archetypal arcs—something I’ll be addressing in a series of posts next year.

9. Walking on Water by Madeleine L’Engle

This book is a beautiful and moving treatise on the creative life and the importance of art. I have read it over and over since first encountering it a few years ago, and it is always a light in the darkness, no matter what is going on in my life or in the world.

10. Write Away by Elizabeth George

This was one of the earliest craft books I read about writing, but it has stayed with me all these years. For the most part, it is a detailed description of mystery writer Elizabeth George’s personal writing routine and particularly her outlining routines. In many ways it was the book that helped me make the first step from writer to author.

***

For more ideas, you can check out my list of Recommended Reading for Writers, as well as my own series of writing books below. Merry Christmas, everyone!

For more Christmas gifts for writers:

17 Eco-Friendly Gifts for Writers This Christmas

20 Unique Gifts for Writers This Christmas

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What do you think are the best books to buy for writers? Tell me in the comments!

The post 10 Best Books to Buy a Writer For Christmas appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 30, 2020

What Is Dreamzoning? (7 Steps to Finding New Story Ideas)

Every writer knows a thing or two about daydreaming. But what about dreamzoning? What’s that—and how can it help you cultivate inspiration for your storytelling?

Every writer knows a thing or two about daydreaming. But what about dreamzoning? What’s that—and how can it help you cultivate inspiration for your storytelling?

Put simplistically, dreamzoning is basically just daydreaming on steroids. It’s purposeful, focused daydreaming. It’s intense. It’s fun. And if you’re a writer, it’s the mother lode of all story ideas.

I’ve named-dropped “dreamzoning” a lot in recent years, but after an exchange on Patreon with Susan Geiger, I realized some readers may not fully understand what I’m talking about. Susan said:

I look forward to trying out “dreamzoning” (I’ve heard you talk about it on your podcast before but never fully understood it….).

Because dreamzoning is such an amazing tool and experience, I figured it was time to do a core post about it.

What Is Dreamzoning?

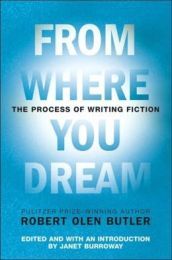

From Where You Dream by Robert Olen Butler (affiliate link)

The word “dreamzone” came into my consciousness years ago when I read From Where You Dream, a transcript of Pulitzer winner Robert Olen Butler’s lectures about “the process of writing fiction.”

In the book, he talked about how he would take the time to find his story inspiration by sitting back at his desk and “zoning out.” He’d watch the pictures in his head, following them, not guiding them but just watching to see what would unfold. Later, he would record the snippets of his imaginings on index cards and use them to formulate an outline. If he ran into a plot problem or question, he would revert to dreamzoning to find the solution.

Like many writers, I immediately resonated with his description of this deeply intuitive mental space. I’d naturally gone there for years, even calling my imaginings my “movies” when I was young. The dreamzone was the space I lived in between waking and sleep every night, as well as the space I physically played in as a child when acting out my stories (a practice that only petered out in my twenties). It’s where I went mentally when doing the “creative lollygagging” chores of dishes or weeding. It’s the space we all go when we’re in the throws of writing—particularly when we’ve hit that sweet spot of “the zone.”

That said, the act of “dreamzoning” itself is, as Butler indicates, always intentional. It is a purposeful quest into the land of stories in order to excavate needed inspiration. Dreamzoning is a way to fill the well so our creative output doesn’t drain it.

Dreamzoning can be done in any number of ways. It can involve sitting at one’s desk with a handful of note cards, like Butler. Or it can happen on commutes with the scenery blurring past outside. Or it can happen every night before sleep. Or it can become a scheduled daily practice.

Over the years, my own preferred setup for dreamzoning has come to revolve around two key ingredients: fire and music.

It started years ago when my brother staged elaborate “fire nights.” Outside under the full moon, he’d create themed “sets” around a campfire, using a playlist for inspiration. There was a safari theme one night, a Dracula theme another. One year for Christmas, he created a winter wonderland complete with fairy lights, which my two-year-old niece went wide-eyed over, but which unfortunately had to be called due to a blizzard. Later on, he’d just curate playlists (my favorite musical discovery from those nights was Van Canto).

For me, the experiences naturally lent themselves to, you guessed it, zoning out and dropping in on my stories. I loved the experience so much and found it so conducive to inspiration that I eventually adopted it for myself. My fire nights, however, were significantly less elaborate—featuring a three-wick candle instead of a full-on set.

As I’ve struggled with burnout in the last few years (which, now that I think about it, coincided rather suspiciously with my brother’s moving away and the end of the fire nights), I’ve returned to this form of dreamzoning more consciously, incorporating it as a fifteen-minute practice at least three nights a week. Although I’m occasionally reluctant to make time, as soon as I drop in, I’m always reminded, Oh yes, this is why I love stories!

Why Should Writers Dreamzone?

First and foremost, dreamzoning is fun. Unless you happen to be that one brilliant adult who is still swordfighting and dragon-riding out in the backyard on a regular basis, you’ve perhaps noticed the intense creativity of childhood doesn’t always seem so available. Dreamzoning is a way to access that regularly (without throwing your back out or alarming the neighbors).

The dreamzone is a meditative state where your logical brain isn’t allowed. Like any form of meditation, logical thoughts may knock at the door, but you keep returning to the intuitive center from which the stories spontaneously arise. If you use music, as I do, it can be an aid and a cue to guide the dreaming. Sometimes, I see a full scene acted out, but often what I get is more like a music video—flashes of dramatic and symbolic imagery syncing up with the music.

Sometimes I get lots of good stuff, sometimes just one nugget, sometimes nothing. But the experience is always renewing and regenerative. It takes me back to the stories of my childhood, which were about nothing but play.

Finally, like any meditative state, dreamzoning can be calming and grounding in its own right within the mental buzziness of the normal day. Fun, useful, and healthy all at once–how about that!

7 Steps to Start Dreamzoning

Ultimately, dreamzoning is a highly personalized experience. You can do it randomly, or you can turn it into a daily practice—either right before writing or at another convenient time during the day. You can do it simply by leaning back and closing your eyes or by staring into the corner. You can do it for ten minutes—or you can do it for two hours (in the right circumstances, the latter is amazing). You can do it with props, or without. You can create an elaborate set around a campfire with high-def speakers and woofer—or you can opt for a candle and headphones.

The only thing that really matters is that you create for yourself a situation in which you can tune out the world and really drop in to your imaginative center.

The followings steps outline my own current process, which I’ve found highly effective.

1. Turn Out the Lights

You might also add “shut the door.” The point is to create an environment in which you can tune out the rest of the world—and your own chattering thoughts along with it. I do my dreamzoning practice in the early evenings, which means it’s not actually dark for half the year. But when it is—it’s even better. (And if you’ve opted for a fire pit under a full moon, better still!)

There’s just something immersive about being wrapped in darkness when going deep into the story realm. It’s like being in a huge dark theater while a gorgeous movie plays on the big screen. If nothing else, the darkness usually helps with concentration.

2. Light a Candle/Fire

The second concentration aid I’ve found transformative is fire. This started with my brother’s campfires, but for simplicity’s sake has now devolved into a three-wick candle on top of a trunk in my spare room (Spare Oom—the portal to all fantasy realms!). Especially when it’s dark, the fire helps focus attention. The flame’s undulating is enough to keep your eye’s attention without distracting you. (Plus, it’s led me to a lot of great fireside scene ideas.)

3. Set a Playlist

The final magic ingredient is music. I set a playlist for the amount of time I want to dreamzone (usually about fifteen minutes—or three songs). Sometimes I’ll specifically choose songs for a particular story I’m working on. Other times, I’ll just randomly select stuff and see where it takes me.

4. Get Comfy

Find a position you can comfortably hold for the duration of your playlist. I generally sit cross-legged on a floor chair across from my candle. If I were dreamzoning for a longer period of time, I would probably opt for a chair with a back. If you’re outside at the fire pit, bundle up against the cold and/or the mosquitoes. As ever, the point is to minimize distractions.

5. Drop In

The whole point of dreamzoning is to get out of our logical, “talky” brains and into our deep imaginative, intuitive cores. For me, as a visual thinker, this looks like mini-movies playing in my head. Back in childhood, this zone was my preferred mental state. These days, the talky brain sometimes has a hard time keeping quiet (it’s kind of like a kid squirming in church). Particularly since my dreamzone practice is only fifteen minutes, it’s important for me to drop in as quickly as possible and stay there. The music helps a ton, and, honestly, so does the urgency. (If I had an hour or two, I’d probably be a lot more lazy about disciplining my thoughts.)

6. Find the Zone

Usually, my brain will pick up a story thread right away, but sometimes it can take me a bit to find a dream that really resonates and interests me enough to follow it down the rabbit hole. If I’m struggling, I’ll consciously bring up a specific story or a scene from the previous day’s dreamzoning and use it to kick-start my imagination. If I’m trying to work through a specific story question or problem, I will gently pose that to my brain—being careful not to start rationalizing answers but just using the question as a prompt to see what my subconscious has in response.

7. Make Notes

Finally—and this is super-important—I make notes as soon as the dreamzone practice is over. Otherwise, like my night dreams, my gleanings from the dreamzone tend to slip away. I keep a running document of notes for all my story ideas, and at the end of a dreamzone session, I’ll just take a quick minute to type some one-sentence descriptions of ideas, answers, or images that I can use to trigger my memory later on when I start writing or plotting in a more logical way. When I look through my notes, I’m often surprised by all the good stuff I’ve recorded but have forgotten about in the interim. It always reignites my excitement about a story!

***

When people ask me to name my favorite part of the writing process, my answer is always “conception”—or, more to the point, daydreaming. Dreamzoning has become my main go-to tool for retaining the playfulness of my childhood creativity in conceiving and nurturing my favorite ideas. It’s good fun in its own right and an incredibly powerful tool for nurturing inspiration on a regular basis. Give it a try!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever tried any version of dreamzoning? What was your experience? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post What Is Dreamzoning? (7 Steps to Finding New Story Ideas) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 27, 2020

Black Friday Deals for Writers

This Black Friday weekend, you can use the code OUTLINE to grab my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software at a special holiday discount of 25% its normal price of $40. (And scroll down for a list of deals from all around the online writing community.)

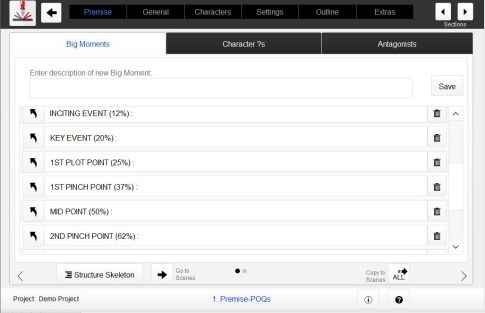

Start Outlining Your Best Book Today

As a reader of my blog, you can access a special 25% discount code for my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software. Just enter the code OUTLINE at checkout. This deal will only be available Black Friday through Cyber Monday. Enjoy!

How Can the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software Help You?

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook computer program is a brainstorming tool for writers. It is designed to guide you in discovering the brilliant possibilities in your ideas, so you can identify those best suited to creating a solid story that will both entertain and move your readers.

The software provides an easy fill-in-the-blanks format that will guide you through every step of the process. Creating your own outline is as simple as starting on the first screen, using the prompts and lessons to work through your story in the most intuitive way, and clicking through the tabs at the top to access important sections.

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook program makes outlining a fun and empowering process that will help you write your best story.

Features:

• Outline – Create a story with a solid Three-Act plot structure and perfect scene structure.

• Premise – Easy fill-in-the-blanks give you a perfect elevator pitch every time.

• General Sketches – Brainstorm the big picture of your scene list, character arcs, and theme.

• Character – Get to know your characters with an extensive character interview, featuring 100+ questions.

• Settings – Keep track of your settings, explore your best options, and answer helpful world-building questions.

• Fun Extras – Import your mind maps and world maps, keep track of your story’s timeline, cast your characters, and create story-specific musical playlists.

Here’s Your Coupon Code:

Don’t forget to use the code below to get 25% off your order of the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software:

OUTLINE

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

More Black Friday Deals:

This year, I’m participating in a joint promotion for deals on writing programs, courses, and more from around the Web. Following, you can find dozens more Black Friday and/or Cyber Monday deals for writers. (Some of the following are affiliate links.)

Note: If you have questions about any of the below offerings, it is best to directly query the particular site for further information.

Storiad: 50% off with Code BLACKFRIDAY2020

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

At Storiad, we know there is a market for every book and every author. Our full-suite book marketing platform ensures you’re able to find it.

The Write Shop: Save 30%

Dates: Nov. 23-Nov. 30

The Write Shop is the online store for writers. Get craft books, writing prompts, apparel and planners, all 30% off for Black Friday.

Well-Storied: Save 50% with the Code BLACKFRIDAY50

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

Looking for guidance as you develop your next sensational novel? Well-Storied’s writing workbooks offer insights and guided activities designed to help you craft your story’s plot, characters, and storyworld with ease. All workbooks come in PDF format and can be printed or filled digitally per your personal preference and writing process.

Freelance Writer’s Den: 60% Off

Dates: Nov. 24–Nov. 30

The Freelance Writers Den is the online community where freelance writers learn how to grow their income—fast.

Master Writer Inc.: Save 50%

Dates: Nov. 23-Nov. 30

MasterWriter is the most powerful suite of writing tools ever assembled in one program. It gives you Word Families, Phrases, Synonyms, Pop Culture, Rhymes, Definitions, a searchable Bible, and Figures of Speech (Metaphors, Similes, Onomatopoeia, Idioms, Oxymorons, Allusions, and Intensifiers).

Novlr: 30% off with code BLACKFRIDAY20

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

Online novel writing software. A beautiful, secure writing interface with everything you need to organize, write, and edit your novel—wherever you are. Novlr is online and can be accessed from any device.

ProWritingAid: Up to 50% Off

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

ProWritingAid is a grammar guru, style editor, and writing mentor in one package. It’s the only platform that offers world-class grammar and style checking combined with more in-depth reports to help you strengthen your writing. Their unique combination of suggestions, articles, videos, and quizzes makes writing fun and interactive.

One Stop for Writers: 50% off with Code BLACKFRIDAY2020

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

One Stop for Writers is a portal to creative tools that will help you master character-building and character arc, plot and structure, world-building, and more. Powered by the largest description database available anywhere, One Stop puts non-stop ideas at your keyboard, enabling you to write stronger fiction, faster. Give the Free Trial a spin or use the one-time code BLACKFRIDAY2020 and get 50% off a 6-month subscription. Writing can be so much easier!

Write|Publish|Sell: Save 50% with code WPSFRIDAY20

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

Instagram for Authors is a power-packed course providing authors with all the tools they need to successfully use Instagram to market and sell their books.

Women in Publishing Summit: 66% off full conference ticket

The Women in Publishing Summit is a week-long conference that provides resources and training to authors across all facets of writing, publishing, marketing, and author development. Made by women, for women, the conference not only delivers incredible content, we celebrate the achievements of women in the industry. Our sponsors provide incredible discounts and opportunities as well to our participants, to help them in the process.

The Novel Factory: 50% Off

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

The Novel Factory Online is the ultimate online novel writing software for writers. It includes tons of useful novel-writing tools, including: • How to write a novel step by step guide • Novel writing templates • Character profile development questions • Character bio templates • and so much more. Also, we’re pledging 20% of all sales in November to Room to Read, a charity that supports literacy for the world’s most vulnerable children. The Novel Factory software can help you achieve your dream of writing a novel—it teaches you the craft of writing, while you complete your manuscript.

BookBaby: $100 Off 100+ Printed Books with code 100OFFBOOK

Dates: Nov. 1–Dec. 31

Why print your book with BookBaby? Our formula for great custom book printing is very simple: BookBaby is a book printing company staffed by professionals utilizing the world’s best book printing and binding equipment. While every individual book project is different, the results are always the same: eye-popping colors, crisp and even ink coverage, quality paper stocks, sturdy, tight book binding, all carefully packaged and delivered to your door. With over 50,000 projects successfully delivered last year, we know what authors require and expect from their book printer.

SelfPubCon: Half-price access with code INDIE50

Dates: Nov. 9–Nov. 30

SelfPubCon, the Self-Publishing Advice Conference, is run in association with the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi) and runs twice a year in March and October, featuring the cream of self-publishing authors and advisors. The access passes give six-month or lifetime access to an extensive conference archive featuring self-publishing advisors like Michael Anderlé, Mark Dawson, Ricardo Fayet, Joanna Penn, Orna Ross, and 100+ more.

First Editing: 20% Off with Code: BLACK20

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

First Editing’s professional editors have assisted over 50,000 authors this past decade. If you’re looking for an editor, you’ll be in safe hands here.

First Editing guarantees your satisfaction and delivers your editing on-time. You’ll get useful, actionable advice that will help you to improve your manuscript ready for submission to a publisher—or self-publication! Plus, you can get a free editing sample of your writing so you can try before you buy.

The Writing Cooperative: 50% Off

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

Writing Cooperative co-founder Justin Cox converted his wildly popular Medium primer into a seven-day guide to Medium mastery. Learn all the tips and tricks Justin acquired growing his Medium following to over 10,000 people and became a top writer in multiple categories, including writing, creativity, life, and books

Grammar Lion: 40% Off

Dates: Nov. 27–Nov. 29

Join the 43K+ students who have elevated their writing and editing skills with this comprehensive course. In this online classroom, when you have grammar questions, you’ll get grammar answers!

Fictionary: 50% off with Code BLACKFRIDAY2020

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

Fictionary StoryTeller makes editing easier by applying universal storytelling structures to each and every scene. Evaluate and revise your manuscript against thirty-eight Fictionary Story Elements to tell a powerful story readers will naturally connect with.

Campfire Technology: Up to 55% off with code BLAZEFRIDAY20

Dates: Nov. 23–Nov. 30

Campfire Blaze helps you write better stories faster with an integrated Word Processor, Character sheets, Timelines, Locations, Maps, Relationships, Character Arcs, Encyclopedia, Magic, Languages, Items, and more on the way! Build your own subscription for as little as fifty cents or as much as a few dollars! You can also purchase lifetime modules for a one-time fee and own it forever. Try out all the features in our free version and rest easy with our 30-day money-back guarantee.

Ghostwriter School: 60% Off

Dates: Nov. 28–Nov. 30

Ghostwriter School is an extensive curriculum designed for current and future ghostwriters to learn how to become more profitable ghostwriters. In Ghostwriter School, you’ll learn how to write amazing content fast, how to create your ghostwriting business plan, how to market yourself, how to develop your plan for recurring revenue, and more.

The DIY Publishing Course Unlimited: 93% Off

Dates: Nov. 27–Nov. 30

The DIY Publishing Course Unlimited is a comprehensive course devoted to self-publishing books and building an author brand. Developed by award-winning and bestselling author, Dale L. Roberts, the DIY Publishing Course has over 14 different course offerings, 4 instructors, and dozens of downloads. Finally discover how to self-publish all in one spot without the worry of missing any one thing about the business.

Note: If you have any questions about any of the offerings, it is best to directly query the particular site for further information.

The post Black Friday Deals for Writers appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 23, 2020

7 Steps to Stop Overthinking Your Writing

It’s a question I’ve received countless times from readers over the years—and one I’ve found myself asking of late as well: How do you stop overthinking your writing?

It’s a question I’ve received countless times from readers over the years—and one I’ve found myself asking of late as well: How do you stop overthinking your writing?

Writers are often known as thinkers. Indeed, we’re often proud of the connotation. We spend a lot of time in our heads. We love to read. We research like we love it (because we do). And we know a lot (though usually not quite as much as we think we do).

However, thinking and writing—especially creative writing such as storytelling—can sometimes seem strangely out of balance. As much as writers may identify as thinkers, we usually prefer the actual act of writing to be less about thinking and more about flowing.

What we’re talking about is “thinking” in the sense of active and logical thinking. Naturally, we are thinking when the words are flowing, but in those moments it often seems less that we are thinking the thoughts and more that the thoughts are thinking us. When we take too much control, it ceases to work that way.

And that’s a problem—because the more a writer learns about how to write and how stories work, the more conscious our thinking becomes. Sometimes this reaches the crisis where writing becomes a lot of work simply because we are doing all the work. We’re the ones doing all the thinking, rather than just being the conduit and letting the thoughts think us.

Susan Geiger recently messaged me on Patreon about this all-too-common conundrum:

I have a problem, a serious one: I am too serious. I love writing and stories in general. However, I have thought so much about plot development, character arcs, theme, story structure, etc., that I’m a bit uptight when I write. I have effectively zapped the joy out of it. I am so tense when I write and put so much pressure on myself that my serious attitude has leaked into the writing itself, leaving the story utterly humorless. If you have any advice on how to relax and lighten up in writing again, I would greatly appreciate it.

Not long after, I received a similar email from David Fraser:

Have noticed my tendency to over-complicate. Overthink. Maybe you would consider writing a post…

I figured I better write the post! If nothing else, maybe I’ll learn a thing or two myself.

November 16, 2020

5 Questions About Scene Sequences

In many ways story structure is a fractal pattern. The same patterns we find on the macro level of the entire story arc also repeat themselves, within an ever-tightening spiral, from scene structure all the way down to sentence structure. Somewhere in between story and scene, we find scene sequences.

In many ways story structure is a fractal pattern. The same patterns we find on the macro level of the entire story arc also repeat themselves, within an ever-tightening spiral, from scene structure all the way down to sentence structure. Somewhere in between story and scene, we find scene sequences.

Within the story’s larger narrative, scene sequences bring a series of individual scenes together into a distinct narrative section, united by focus, location, and/or theme. Most writers instinctively and effortlessly employ the sequence as a way to execute character goals that require more than a simple one-shot solution. The result is both the opportunity for big set-piece scenes (such as we would usually hope to find at the three major plot points) and/or complex thematic discussions and character evolution.

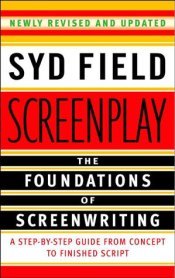

Screenplay by Syd Field (affiliate link)

Not too long ago, Wordplayer Eric Troyer emailed me about scene sequences:

I just finished Syd Field’s book Screenplay. [H]e wrote about something I haven’t seen before in quite the same way: sequences…. I don’t believe you’ve explored this before. If not, it’s something that might interest you. If so, I would love to read about it in your blog some time.

This made me realize the only material I’ve shared on scene sequences was in an interview on someone else’s podcast years ago when my book Structuring Your Novel first came out. Since I couldn’t find that interview anywhere, I decided now would be a good opportunity to talk about this important (and very fun) structural technique.

In his book (which is just as great for novelists as for screenwriters), Field introduces scene sequences by saying:

A sequence is a series of scenes connected by one single idea, usually expressed in a word or two: a wedding; a funeral; a chase; a race; an election; a reunion; an arrival or departure; a coronation; a bank holdup. The context of the sequence is the specific idea that can be expressed in a few words or less.

5 Questions (and Answers) About Scene Sequences

Let’s take a closer look at scene sequences by examining them in light of the following five questions (which were originally asked me in that interview I can’t find).

1. How Does Scene Structure Fit Into the Overall Idea of Story Structure?

Because scene sequences are built upon scenes, let’s first take a quick look at how individual scenes can be structured within the story’s larger narrative.

Techniques of the Selling Writer by Dwight V. Swain (affiliate link)

Although scene structure is an aspect of story structure that is sometimes overlooked, it’s a deeply intuitive concept to grasp. Classic scene structure, as encoded by Dwight V. Swain in his book Techniques of the Selling Writer, breaks scenes down into two parts: scene and sequel.

The “scene” section focuses on the protagonist taking action, while the “sequel” section focuses on the protagonist’s reaction to the outcome of his or her previous actions. The balance between action and reaction is a chief tool for maintaining a story’s credibility and the readers’ suspension of disbelief. For every action, there must be a reaction. For every scene, there must be a sequel.

From there, we can further break scenes and sequels down into three parts apiece.

We break the scene down into:

1. Goal.

2. Conflict.

3. Outcome (or, as I like to specify, Disaster).

And we break the sequel down into:

1. Reaction.

2. Dilemma.

3. Decision.

Structuring Your Novel (affiliate link)

The scene/action half begins with the character enacting a goal. He wants something. This desire is what drives the scene. Without a character goal, the scene will end up meandering and purposeless.

That goal must then be met with conflict. In this sense, conflict is nothing more or less than an obstacle. It’s something preventing the character from reaching the scene goal.

The outcome will be the resolution of that conflict, one way or another. Either the character reaches her goal or she doesn’t. I like to put the emphasis on disaster in the outcome because we don’t want characters to achieve their goals too quickly or too easily. If characters achieve too many scene goals in a row, they will inevitably achieve their ultimate story goal—and the story ends. You don’t want to give characters a straight road to their end goal. You want to push them sideways with scenes that end in disasters or “yes, but…” half-disasters.

Once you’ve hit your character with this scene-ending disaster, you will enter the sequel/reaction phase, in which you must then give the character enough space to react to whatever just happened. How does he feel about what just occurred? What is he thinking?

From there, the character progresses to dilemma. Whatever just happened, whether it seemed good or bad, will create a new problem—a new wrinkle in the character’s plan to reach her overall story goal. She must analyze her new dilemma.

Based on that, she will then make her decision. The decision will translate directly into the next scene’s goal.

If you get the basic structure of your scenes set up just right, every moment in your story is like a train on a track. Every moment perfectly influences the next.

2. What About Scene Sequences? How Do You Take Your Individual Scenes and Build Them One Upon Another to Create an Entire Story?

The scene sequence offers an important progression from the simple idea of scene. When focusing on the microscopic level of individual scene structure, it can be easy to start viewing each scene as a complete unit unto itself. This isn’t necessarily problematic, since the smallest integers of story are what slowly build up to a solid overall story. However, you can get hung up on the small stuff and start feeling like each scene is living in its own little vacuum.

This, of course, isn’t the case at all. Every scene must be integral to the story as a whole. Every scene must matter to every other scene. Sometimes, you can take this principle a little further to start creating scene sequences.

A scene sequence can be thought of as a little story within the story. A scene sequence will have a unified focus, usually one we can sum up simply. As Field described in the quote at the beginning of the post, your sequence could be about a rescue, a wedding, a trial, or a battle.

Scene sequences should be given a defined beginning, middle, and end. They should have a mini-plot arc of their own.

As an example, think about the sequence in the original Toy Story movie in which the toys Buzz and Woody initially attempt to return to their owner Andy. The sequence begins when they’ve jumped out of Andy’s mom’s van and gotten themselves stranded at the gas station.

From there, we can see a linked chain of several different scenes in which they’re attempting various gambits to catch up with Andy at the restaurant Pizza Planet: they bum a ride on the Pizza Planet truck, they sneak into the restaurant, they spot Andy—and then the sequence ends when they get stuck in the claw machine with the Little Green Men and are “won” by the evil neighbor kid Sid.

Each segment of this sequence is a scene in its own right. The characters are faced with a series of dilemmas, which prompts a series of new goals, which are then met with conflict. First, they have to find a way to get to Pizza Planet, then they have to get into Pizza Planet, then they have to locate Andy, etc.

These multiple related scenes combine into a distinct episode within the story—unified by the overall goal of trying to catch up with Andy while he’s still in town. In essence, the little scenes have become a bigger scene, which when combined with other “bigger scenes” becomes the entire story.

3. How Do Scene Sequences Affect the Major Plot Points?

More often than not, the First Plot Point (25%), Midpoint (50%), and Third Plot Point (75%) will be sequences rather than just standalone scenes. This is because major plot points are major moments within the story. They’re the set-pieces. They’re the big, juicy, interesting moments that readers wait the whole book to get to. You’re rarely going to want to buzz on by those major plot points in a single scene. The plot points will comprise big and involved events. As such, they’re likely to take place over the course of several scenes—a scene sequence.

This is always worth thinking about as you’re planning your major plot points. If an event comes to mind for one of these beats, but it’s something comparatively small that you can execute in a single scene, you might want to dig deeper. See if you can find something a little more involved, a little more complicated, a little more dramatic.

This is not to say plot points must be part of a sequence. Not all stories will require every plot point to be that in-depth. Study how other authors utilize scene sequences around their plot points, and listen to your instincts in your own writing.

One other thing to realize about the relation between scene sequences and plot points is that the very length involved in sequences—which can span as much as a hundred pages—allows for a little more flexibility in the timing of the plot points. Ideal story structure places the plot points at the 25%, 50%, and 75% marks within the story. This leads some writers to obsess about landing each plot point smack on the money.

However, in longer works of fiction, such as a novel, the pacing and thus the timing is more flexible. If any part of your major plot point sequence lands at its pertinent quarter mark in the story, you’re probably safe. This is because the scenes in that sequence are all connected. They roll their momentum one into another, which allows readers to still get the sense of the structural beat’s impact, even if the timing isn’t perfect.

4. Should There Be a Specific Number of Sequences Per Story?

No, there absolutely doesn’t have to be a specific number of sequences. Aside from the fact that every novel varies in length and pacing, how authors sequence their stories is very much a personal choice. The story must dictate where its going and what needs to happen.

Intended for Harm by C. S. Lakin (affiliate link)

For example, C.S. Lakin’s family saga Intended for Harm is told in the unique format of fifteen-minute segments of a family’s life over the course of thirty years. In this case, even though each scene is integrally related to the others, the unique format means there aren’t many sequences.

At the other end of the spectrum, you have the massive fantasies, such as those by Brandon Sanderson or Patrick Rothfuss. These books are packed with tremendous sequences in which plans are being enacted or battles are taking place. Big books like this might include upwards of forty or more sequences.

5. Do Sequences Have to Be Any Specific Length?

The Black Prism by Brent Weeks (affiliate link)

Nope to this too. Sequences don’t ever have to be any specific length. Technically, a sequence is simply more than one scene linked into its own little mini-narrative. A sequence could be formed of as few as two scenes. Or as in the above-mentioned big fantasy books, certain sequences might encompass a hundred pages and contain dozens of scenes. The final battle in Brent Weeks’s The Black Prism spans the entire Third Act and is comprised of a plethora of little scenes.

The length of your scene sequences will depend on the story you’re writing, how fast or slow you want to pace it, and how many big set-piece scenes you’re trying to work with.

***

Scene sequences can be one of the most delightful integers of story structure to work with, since they offer both the same tight control of an individual scene’s structure, as well as the vast creative possibilities of developing larger memorable units within the overall story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of some scene sequences you’ve included in your latest story? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 5 Questions About Scene Sequences appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 9, 2020

Are You Growing as a Writer? (Here’s the Only Way to Tell)

Do you want to grow as a writer?

Do you want to grow as a writer?

I know you do, simply because you are a writer. I know because you are here reading this post, either because you subscribe to this blog and others like it as a way to mainline writing knowledge on a regular basis, or because you stumbled onto this post in a search through the jungles of the Internet for the answer to one of the many, many writing questions that press down upon us all.

Many of those questions (and the available answers) are craft-based. How to write a story? How to write a good story? How to craft convincing plots, characters, theme, dialogue, narrative, action, romance, mystery, you name it? We seek to further our growth as writers in part to abate the misery of our own inadequacies in the face of such a complex art form, and in part because we are as fascinated by the patterns and techniques of story as we are the stories themselves.

I don’t believe this type of craft-focused growth ever finds an end, but it does, after a time, create a relative mastery. So what then? Where does the true and deep growth come from then?

Storytelling as an Exploration of the “Shadow”

A few years ago, I wrote a post in which I talked about four levels in our climb up the writing mountain. In it, I talked about how I felt I had reached the stage, in my own journey, where “I knew what I knew.” I wrote the post with a certain amount of satisfaction, of course. But deep in my heart, I also wrote it with more than a little fear and trembling—because what came next? Was writing just going to be easy and fun and a total breeze from that point on? Was it all downhill from there?

Of course not. My storytelling instincts were honed well enough for me to feel the foreshadowing. Hello, False Victory. Hello, Third Plot Point. (And if you know story structure, you know what that means.)

What I found beyond that plateau was a total paradigm shift in my relationship to my creativity. It is still ongoing, and even now I do not yet have a clear view of the next mountain. I have always believed mastery is the unconscious made conscious—to the point where the conscious understanding eventually reintegrates with the unconscious as “knowing instinct.” I now believe that is what lies beyond the stage of “knowing what you know.”

Basically, it feels like unlearning everything you learned. For me, I sense it means moving into a creative process that is less obsessively ordered. (I’m still not sure where I’m going next, so I hesitate to speak of it in concrete terms, but I have this sneaking feeling that I, who have identified all my life as an obsessive outliner, might be headed into the terrifying wilderness of pantsing.) More to the point, this is all bringing home to me more clearly than ever that any growth that occurs in the creative process is not merely about mastering skill, but also, and more pertinently, about our growth as human beings.

A Little Book on the Human Shadow by Robert Bly (affiliate link)

In these last few years, it has become less and less of a serendipitous surprise to me to realize that most of my greatest creative insights are arising not from books about writing, but from books about humans. One standout example is a tiny volume I picked up about the psychological theory of the “shadow” (basically, everything we store in the unconscious). The book turned out to be written by (who else?) a poet. In A Little Book on the Human Shadow, poet Robert Bly referenced a quote from medieval philosopher Jakob Böhme, which although speaking about people reading books is, I think, even more aptly put to people writing books:

Böhme has a note before one of his books, in which he asks the reader not to go farther and read the book unless he is willing to make practical changes as a result of the reading. Otherwise, Böhme says, reading the book will be bad for him, dangerous.

This brings me back to my original question. How do we know if we are growing as writers—if we are really growing? I daresay it is far less about how well we are crafting our plot structures and our sentences, and much more about whether what we are writing is true enough and powerful enough to affect our own perceptions of life and our approaches to living it.

Bly pointed out:

The European artists—at least Yeats, Tolstoy, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Rilke—seem to understand better that the shadow has to be lived too, as well as accepted in the work of art. The implication of all their art is that each time a man or woman succeeds in making a line so rich and alive with the senses, as full of darkness as [Wallace Stevens’s]:

quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries

he must from then on live differently. A change in his life has to come as a response to the change in his language…. [Rilke] was always ready to change his way of living at a moment’s notice if the art told him to.

Beware Your Own Ruts, Formulae, and “Knowledge”

The willingness to be impacted by our own art will manifest differently for each writer (and for each thing written). Sometimes it will mean enacting tremendous personal paradigm shifts. Sometimes it will require lifestyle changes. Sometimes the changes are smaller: just the willingness to see beauty in details we have previously overlooked. Sometimes the changes are ineffable, more a prayer than a crusade. And sometimes the changes have to do with the art itself.

For me, I’m finding it means I cannot create in the ways I used to. I mean, I can. To a certain degree, I have mastered my art. But I begin to realize that in becoming master, I now risk becoming tyrant. Nineteenth-century French literary critic Charles Sainte-Beuve cautions us:

There exists in most men a poet who died young, whom the man survived.

I don’t wish to outlive my inner poet. But that is what I risk if I am unwilling to learn the lesson my creativity would teach me and to keep growing. I have worked so hard to consciously understand my craft—to mitigate those miserable moments when the story isn’t working and I have no idea why. And yet the next step seems to be putting back on the blindfold, trusting my Muse to take my hand and lead me straight back into the misty realms of unconscious creativity.

If this sounds a little hazy and unformed, it is! None of this discounts all the learning and growth that has come before. The formulae, patterns, techniques, practices, guidelines, and structure of the craft are vital. Consciousness and understanding are important in art as in life. I am not saying writers shouldn’t be learning all this stuff. If you feel you don’t yet understand plot structure, for the love of anyone who will read your story, please learn it. But the moment structuring gets to be a rut, realize it’s time to keep growing.

The Fire in Fiction by Donald Maass (affiliate link)

Every single day at the page should be a gut-check. But don’t worry. If you don’t check in, your gut will eventually tell you what’s going on anyway. As literary agent Donald Maass shares in the closing of The Fire in Fiction:

How do the events of your story make your point? Do you even have a point? I believe that you do. How do I know? Because I know that you are not a person lacking principles and void of passion. That isn’t possible. You are, after all, writing fiction. That is not an activity taken up by those without a heart.

If you start to feel you are writing the same story over and over, it’s likely because you didn’t allow the story you just finished to change you. Maass goes on with the challenge:

Some bemoan the decline of reading and lament the sad state of contemporary fiction. Are they right? Sometimes I wonder…. [A trend of contemporary novels] is to make characters of Jane Austen, Edgar Allan Poe, and Arthur Conan Doyle or to borrow their creations. What has happened to us? Have we lost confidence in our own imaginations? Are we afraid of portraying grand characters and big events? Do we identify only with victims? Is the story of our age no more than a tale of survival?

Perhaps. Contemporary fiction reflects who we are. And who are you? How do you see our human condition? Where have you been that the rest of us should go? … Having something to say, or something you wish us to experience, is what gives your novel power. Identify it. Make it loud. Do not be afraid of what’s in your burning heart. When it comes through on the page, you will be a true storyteller.

Storytelling as the Art of Changing the World Yourself

More than any other form of writing, storytelling is dreaming out loud. It is an exploration of our inner selves, our true selves, conscious and unconscious, sun and shadow. It tells us things we do not know (or at least that we do not know that we know). In so many ways, true creativity—true art—is an act of revelation. This is true of great masterpieces, but it is just as true of small scribblings that never see the light of day.

If You Want to Write by Brenda Ueland (affiliate link)

Last year, I shared some of my ponderings about the ego-driven nature of most fiction. I recognize that a great part of the struggle in my own soul over this new direction I feel my creativity taking is that I’m going to have to return to writing things with no thought for publication. I’m going to have to release the ego’s need for confirmation and remember the inherent worth in the act of creation for creation’s sake. In her fantastically inspiring classic If You Want to Write, Brenda Ueland reminds us:

If I wrote something true and good that nobody cared to read, it would do me a great deal of good.

I think we forget that sometimes. To a large extent, we write either because we want to do it well enough to be published (for any variety of reasons), or we do it because we have this seemingly admirable desire to have a positive effect on our world. But if we create something and it does neither of those things—is that creation somehow worthless?

Perhaps. The answer depends entirely on what and why and how we have created it. If, however, we ourselves are changed by act of creating something, anything, even something sloppy and silly—then by that act we have changed the world. And if we have not been changed by our own creation, then have we really done anything after all, no matter how popular the story is?

Ueland also says:

…writing is not a performance but a generosity.

I do not believe she was speaking of the “generosity” of giving people one more story to read or watch. She was speaking of the generosity of writing something with deep honesty, passion, and personal truth just for the sake of writing it.

So once again, we return to my original question: How can you know if you are growing as a writer?

There are many ways. There is the ability to compare your most recent story with the previous story and to know the recent one is more technically sound. Then there is the ability to know what you know—to truly and consciously understand what is required to create a solid story and to fix its problems.

But there is also the growth of you as an individual. There is the growth that comes simply because you wrote a story and now, in any number of possible ways, you are a different person.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How has being a writer changed you as a person? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post Are You Growing as a Writer? (Here’s the Only Way to Tell) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 2, 2020

The Power of Chiastic Story Structure (Especially in a Series)

When writers put on their story theorist caps, nothing is more exciting than those moments when you get to recognize consistent patterns emerging within obvious story forms. This is the basis of all of our understanding (and musing) about story, including the chiastic story structure we’ve been studying these past few months.

When writers put on their story theorist caps, nothing is more exciting than those moments when you get to recognize consistent patterns emerging within obvious story forms. This is the basis of all of our understanding (and musing) about story, including the chiastic story structure we’ve been studying these past few months.

Although writers sometimes think of story structure as something external (and therefore rather arbitrary) that we impose on a story in order to make it look a certain accepted way, it is actually just the opposite. Story structure, in all its many posited forms, is simply a record of the long-recognized patterns that have emerged from humankind’s millennia of stories.

Structuring Your Novel (affiliate link)

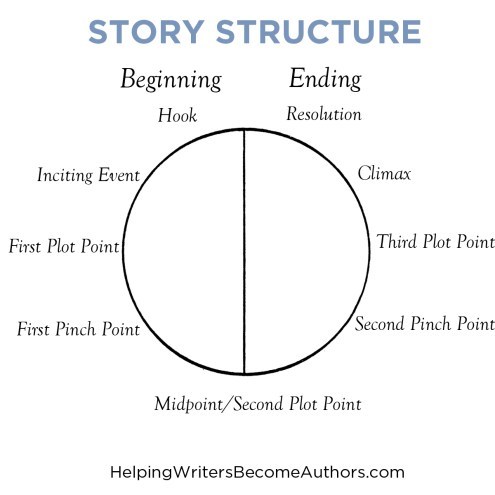

By a certain point in the pursuit of story, most writers become familiar with what is now considered the “standard” Three-Act Structure. But as we’ve been exploring in this little series, another lesser-known pattern that emerges from this foundation is that of chiastic story structure. Sometimes called “ring structure,” a chiastic structure is one in which the two halves mirror each other in reverse order—in essence coming full circle.

In the last five posts, we’ve explored how all the major beats recognized in the Three-Act Structure are in fact inherently chiastic. We find important structural and symbolic links between all the following:

The Hook and Resolution

The Inciting Event and Climactic Moment

The First and Third Plot Points

The First and Second Pinch Points

And we also find a linked or mirrored structure inherent within itself at the story’s central pivot:

The Midpoint

Now that we have examined the chiastic links between all the major structural beats, I want to close out the discussion with an overview of chiastic story structure itself, along with a look at how you can employ this technique over the longer work of an entire series.

What Is Chiastic Story Structure?

As stated, chiastic structure is a literary technique of repetitive symmetry, designed to create insight and resonance through both comparison and contrast. We can witness chiasmus as a common technique in poetry, employing the pattern of “A, B, B, A” (and so on). It can also be used most simply on the sentence level, as we see in such famous sentences as:

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.“–John F. Kennedy

“We shape our buildings, and afterward our buildings shape us.”–Winston Churchill

“All for one and one for all!”–Alexandre Dumas

“Man can be destroyed but not defeated. Man can be defeated but not destroyed.”–Ernest Hemingway

Chiastic structure is perhaps most famously recognized from ancient religious texts, including the Bible. Wikipedia shows the Genesis account of the flood to be structured like this:

Other ancient texts such as Beowulf and The Iliad can also be seen to demonstrate chiasmus, both structurally and narratively. More recently, many analyses have shown that the great cohesion and resonance of the Harry Potter series is thanks largely to its chiastic structure. Of course, as we’ve been exploring throughout this series, any story that adheres to classic structure is, in fact, offering at least a nominal chiastic structure.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (affiliate link)

Why is chiastic story structure so prevalent and, clearly, so powerful? There are many reasons, not least the fact that it provides plentiful opportunities to use the potent tools of comparison and contrast to deepen thematic weft, sometimes overtly and sometimes subconsciously. Moreover, chiastic story structure all but ensures a story will emerge cohesive and resonant. If all its major pieces are connected, then necessarily they will be all of a whole. They come together, even in their variation, to create a unified big picture.

Perhaps most importantly, but also most simply, chiastic structure demands a story fulfill the sometimes mystifying directive that the “ending is in the beginning.” In chiastic structure, this is almost literally true since the beginning not only foreshadows the ending, but in fact ensures the beginning and ending are reverse images of one another, however subtly.

Like any storytelling technique, chiastic structure can be applied too overtly and become on the nose. You don’t want the links between your story’s halves to feel repetitious, nor do you want them to be obviously “matchy-matchy.”

You can see how wonderfully successful and resonant (and yet not “matchy” or on the nose) chiasmus is in the Harry Potter series simply in recognizing the link between the series’ beginning and ending.

In the beginning, Voldemort casts a killing curse on Harry and does not die; in the end, he casts a killing curse and does die.

This is chiasmus at its absolute most basic within this series. The series utilizes a linked structure almost perfectly scene by scene in every book, as well as over the course of the entire series. Many people have written about this extensively, including in this graphic.

4 Tips for Implementing Chiastic Structure in a Series

In past posts, we’ve already talked about how you can employ a chiastic structure in standalone books simply by ensuring they are classically structured. Understanding how the story comes full circle in this way allows you to strengthen the mirroring elements throughout both halves of the book. But as we’ve already seen in the reference to the Harry Potter series, you can also utilize chiastic structure to powerful effect by applying it to the overarching structure of a longer series of books. Although the same basic principles apply to series structure as to standalone structure, here are a few particular tips to keep in mind when creating chiastic story structure for a series of books.

1. Know the Ending in the Beginning

Outlining Your Novel (affiliate link)

Whether or not you outline your story before the first draft, at some point you must know how your story will end. And when you know how it will end, you must go back to make sure this ending is reflected in the beginning. (You can see more about the specifics of how to do this in the previous posts on the link between the Hook and the Resolution and particularly the link between the Inciting Event and the Climactic Moment.)

This is especially important in writing a series of cohesion and resonance. Unfortunately, foreseeing the ending is much harder to do in a series than in a standalone book. Most of us write the first book with little or no true understanding of precisely how the series will end. So what can you do?

The most obvious solution is to outline the entire series before you start writing the first book.

You can also try to implement the chiastic effect as you go by mirroring the second half to the first (rather than the other way around). This can work, but it can also be difficult to pull off soundly since the most important moment in the story is the ending. It’s usually easier to create a resonant plot from a beginning that mirrors the ending, rather than an ending that mirrors the beginning (although the MCU did it rather handily).

Regardless your approach, try at least to gain a firm sense of how many books will be in the series. An odd number, such as the classic three books of a trilogy or the seven books of Harry Potter, offers the most ease for constructing a chiastic structure, since there will already be an inherent symmetry to the books, with one book (the second or the fourth in these examples) standing out as the obvious Midpoint of the series. If you don’t know which book will be your story’s centerpiece, you’ll have difficulty consciously structuring the series in a chiastic way.

2. Make Use of the Series’ Innate Structural Chiastic Offerings

Any overarching series is essentially a single story. As such, this overarching story will offer an inherent story arc of its own, following all of same foundational beats that are found in each individual book:

Hook

Inciting Event

First Plot Point

First Pinch Point

Midpoint (Second Plot Point)

Second Pinch Point

Third Plot Point

Climax

Resolution

The timing may be slightly different in the series than in the standalone books, but the basic structure holds true. This means that just as an individual book’s structure is inherently chiastic, so too is the overarching story of any series. In the same way as you can mine this inherency to magnify the chiastic effect in a standalone, you can also mine it from the series as a whole with just a little careful conscious attention to the natural links between structural beats.

3. Choose Chiastic Symbols, Settings, and “Easter Eggs”

There may be times when a series won’t allow you to perfectly execute chiastic scenes at every single structural beat. (This isn’t “ideal,” of course, but let’s be realistic…) Although chiasmus is most powerful on the plot level—when the events of linked scenes pay each other off in important ways that move the story forward—you can still communicate the concept of symmetry to readers on subtler level.

In fact, even when your chiastic plot structure is perfect, underlining it with additional symbolic symmetry will only strengthen the effect. Think about the visuals you have chosen for each of your linked structural beats. How can they mirror each other? Pay special attention to symbols, colors, settings, characters who are present, even invisible “Easter eggs”—hidden symbolism that only the most perceptive readers will even notice at all.

4. Remember Chiasmus Is “Comparative Symmetry”

Finally, remember that chiasmus evokes meaning not simply through creating obvious links or “sameness” between structural beats, but most importantly by contrasting them. Chiasmus creates the effect of “mirror images” between the halves of a story—which means the images are reversed from one side of the story to the next.

Creating Character Arcs (affiliate link)

This is reflected most obviously in the protagonist’s character arc: perhaps in the beginning he believed a Lie, but in the end he believes the Truth. You can utilize this “reversal” in many ways, not just to avoid repetition but to emphasize the progression and the dynamic change that is happening from one half of the story to the next. In considering how you can create resonant links between the beats in the first and second halves of your story, look not just to comparisons but to blatant contrasts.

***

Thanks so much to all of you for your enthusiasm in joining me on this journey through this beautiful layer of story theory—chiastic story structure. I started this series as what I thought would be a standalone post, in response to a question from one of you about this mysterious link I’m always talking about between the Inciting Event and the Climactic Moment. But your passionate interest in the subject led me to expand it into this six-part series, and I’m so glad you did because I’ve learned an incredible amount along the way myself.

All the best with your chiastic structures in your own stories!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you think you’ll ever attempt chiastic story structure in a series? Tell me in the comments!

The post The Power of Chiastic Story Structure (Especially in a Series) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 26, 2020

The Midpoint as the Swivel Point of Your Story’s Linked Structure

The “saggy middle” of a story is one of the biggest challenges writers face. The Second Act is twice as long as the other two acts and yet is often less clearly defined. What’s a writer to do to keep the pacing just as tight and the events just as interesting over the long haul of the Second Act? The simplest answer is: Mind the Midpoint.

The “saggy middle” of a story is one of the biggest challenges writers face. The Second Act is twice as long as the other two acts and yet is often less clearly defined. What’s a writer to do to keep the pacing just as tight and the events just as interesting over the long haul of the Second Act? The simplest answer is: Mind the Midpoint.

Writing instruction is often more prolific for the First Act and the Third Act, since their functions and responsibilities are more clearly defined. The First Act must hook readers and set up the conflict. The Third Act must ramp up into a satisfying Climax that concludes the conflict. Both of these acts are comparatively short, only a quarter each of the story, and so they are often very busy in their need to check all the necessary boxes.

The Second Act, by comparison, can seem a long desert trek. We understand something must happen between the setup and resolution, and we recognize this something is the conflict itself. But beyond that, we can sometimes struggle to keep this heart of our story pumping in a way that also keeps readers turning pages. Cue the saggy middle.

Structuring Your Novel (affiliate link)

Fortunately, there is an obvious and simple solution, and it’s the same solution writers use to compose the First and Third Acts: story structure. The heart of that structure in the Second Act—and, indeed, the heart of the entire story’s structure—is the Midpoint. If you have the Midpoint in place and working well (along with its fellow Second-Act beats the Pinch Points), your Second Act will be on its way to pulling its own weight.

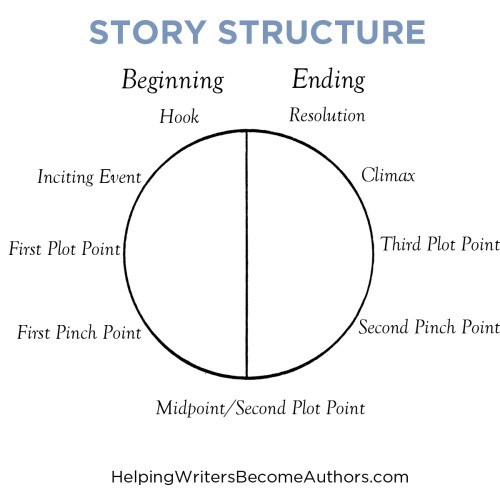

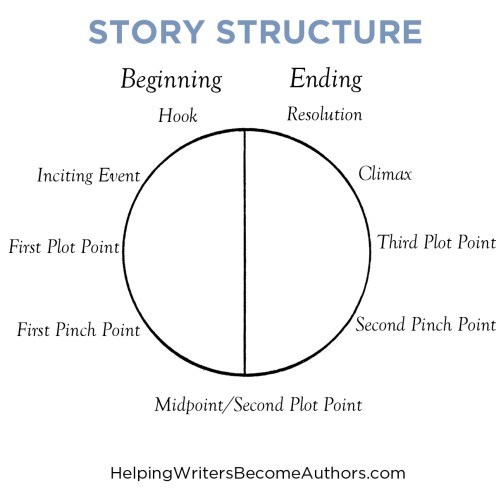

Over the last month or so, we’ve been exploring the idea that story structure is inherently chiastic—a pattern in which we recognize that the beats in the second half mirror, in reverse order, those in the first half. We can see this most plainly if we view story structure less as an arc and more as a circle.

So far, we’ve discussed the link between the Hook and Resolution, the link between the Inciting Event and Climactic Moment, the link between the First and Third Plot Points, and the link between the First and Second Pinch Points. Today, it’s time to discuss the final structural beat, the lone ranger of the bunch—the Midpoint.

As you can see in the graphic, the Midpoint reigns alone at the base of the circle. It has no paired beat but is rather the pivot point around which all the beats in the first and second halves swivel. As such, the Midpoint does not specifically mirror any other beat (although, as James Scott Bell discusses, it is often the representative Mirror Moment for the entire story). Rather, it acts to resolve certain elements in the first half, with this resolution then become the catalyst for all the mirroring elements in the second half.

Structurally Speaking: What Is the Midpoint?

Within the structural nomenclature I use, the Midpoint is technically the Second Plot Point. Other instructors and systems sometimes give the Midpoint no other name and refer to the Third Plot Point as the Second Plot Point. Don’t get confused, since although the names may sometimes differ, the structural beats at the 50% and 75% marks still perform the same functions in all the varied instructional systems.

The Midpoint occurs at the 50% mark, halfway through the Second Act and (obviously) halfway through the book itself. Although many writers neglect the Midpoint in comparison to more noted moments such as the First Plot Point or Climax, the Midpoint is arguably the most significant beat within the story. It is what director Sam Peckinpah called the “centerpiece” of the entire story. Everything hangs upon it. In many ways, it is the moment that decides the ultimate fate of the story. What happens here—what the characters realize and decide—will determine whether or not they arc positively and triumph in the Climax’s final confrontation.

As such, the Midpoint will often be one of your biggest and most visual scenes. In a more adventurous story, this might mean you stage a big set-piece battle scene here. In a more relational story, it may be only one single significant visual or conversation. Regardless, it must be electric. It must dynamically move the characters and the plot.

Creating Character Arcs (affiliate link)

The Midpoint will feature at least one, possibly more, momentous revelations. Within the primary character arc and thematic exploration, the protagonist will encounter a Moment of Truth that forever changes his or her view of the story’s central philosophy. This revelation, perhaps in partnership with a further external revelation about the nature of the conflict itself, will forever evolve how the protagonist approaches the conflict—on both a personal and practical level. It signals a thematic shift from Lie to Truth (or vice versa) and an external shift from ineffective “reaction” to increasingly effective “action.” Not to put too fine a point on it, the lessons the protagonist has learned in the first half will now crystallize into an actionable plan in the second half.

(This article doesn’t discuss the First and Third Acts, but here’s the link to the corresponding First Act Timeline and Third Act Timeline graphics if you’re interested.)

Recognizing the Central Importance of the Midpoint

You can think of the pivot created by your story’s Midpoint in a few different ways:

Centerpiece: Set-Piece Scene

One of the primary reasons structural turning points are important within a story is because they regulate the pacing, which in turn regulates the entertainment value a reader or viewer is receiving. The three main Plot Points in particular should be big moments within the story. Arguably, there is none bigger than the Midpoint.

This is your opportunity to create a stellar set-piece scene or sequence—one that not only performs its structural duties, but that wows your audience. If you imagine your story as a big dinner party, then the Midpoint is the jaw-dropping centerpiece in the middle of the table. Take this opportunity pull out all the stops and give your readers something they won’t easily forget.

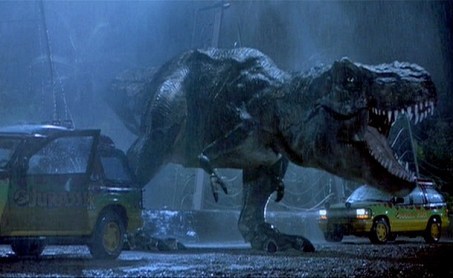

For Example: In one of my all-time favorite examples of a viscerally unforgettable Midpoint shift, Jurassic Park revs out of a totally character-driven first half with a (literal) lightning storm of a Midpoint. During a tropical storm, the power goes out and the electric fences fail. The dinosaurs—most notably the T-Rex—escape, and the characters will spend the rest of the movie very actively trying to find a way off the island.

Thematic Moment of Truth

Writing Your Story’s Theme (affiliate link)

The Midpoint’s primary thematic job is that of pivoting the protagonist’s character arc with a Moment of Truth. The protagonist will have spent the first half of the story engulfed in an inner battle between the Lie She Believes and the thematic Truth. Whether or not she will learn to move forward and embrace the Truth will be decided at the Midpoint, when she will be confronted with a powerful manifestation of the Truth.

In a Positive-Change Arc, the protagonist will see the Truth as true and begin accepting it over the second half the story—although she will not yet fully reject her Lie. In a Negative-Change Arc, she will reject the offered Truth and begin plunging even more deeply and irrevocably into the Lie. In a Flat Arc, she will make a stand for the Truth and offer it to supporting characters around her.

For Example: In the classic Bette Davis film Now, Voyager, the protagonist Charlotte returns home to confront her tyrannical mother. This is a wonderful Midpoint on so many levels. Fundamentally, it is all about Charlotte’s Moment of Truth: will she or won’t she revert to the person she used to be and submit to her mother’s unreasonable demands? There is true doubt about which direction she will take, but ultimately she chooses to reject the Lie her mother has always told her: that she can’t survive on her own. She does it beautifully and realistically, in a real attempt to maintain good relations with her horrible mother.

Mirror Moment

Write Your Novel From the Middle by James Scott Bell (affiliate link)

It is apt that the Midpoint should be thought of as the “Mirror Moment.” Whereas all the other beats in the story’s first and second half mirror each other, the Midpoint stands alone in mirroring itself. In his book Write Your Novel From the Middle, James Scott Bell suggests the Midpoint’s MirrorMmoment is where “the main character has to figuratively look at himself… and be confronted with a disturbing truth: change or die.”

Wayfarer (affiliate link)

In short, this is the Moment of Truth, mentioned above. However, it is more than that, since it offers the opportunity for a particularly powerful bit of symbolism: the mirror itself. Bell notes with interest how frequently we will see a protagonist either literally look into a mirror at the Midpoint, or at least be present in the same room with a reflective surface. You can also symbolize your protagonist “facing himself” in other ways, such as having him face a character who is like him. (In my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer, I had the opportunity to force my protagonist to witness the callous deeds committed by someone who had taken on his own appearance.)

For Example: In the classic musical Singin’ in the Rain, Gene Kelly’s actor protagonist literally faces himself when forced to watch his own dismal performance onscreen during a public movie preview. What he witnesses brings home the brutal truth about his own and the studio’s arrogance in thinking they could blithely transition from silent films to talkies. This truth pivots both the plot and his character arc.

Major Revelation That Turns the Plot

Depending on the nature of your story, how prominent your protagonist’s character arc is, and what set-piece action you have chosen for the Midpoint, the revelation offered by the thematic Moment of Truth may be enough to turn the plot as well. However, it’s possible you may need a second (but hopefully related) revelation, which provides the protagonist with an important insight into the nature of the conflict.

Secrets of Story by Matt Bird (affiliate link)

Whether or not the Midpoint proves to be an outright success within the conflict for the protagonist, it will show him where his methods have so far been ineffective. It will inform him as to the true nature of the antagonistic force he is facing, and it will provide him with information about how he can move more effectively toward his plot goal in the second half of the story. As such, it signals the protagonist’s ability to shift from comparatively ineffective “reaction” in the first half (or Matt Bird’s “doing things the easy way”) to increasingly effective “action” in the second half (“doing things the hard way”).