K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 25

April 19, 2021

Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 11: The Queen’s Shadow Archetypes

A character who makes it through the Hero Arc is a character who has graduated into a brave new world—the Second Act of the life cycle of archetypal character arcs. This section of life, which deals with questions of relationship and power, begins with the first of the “mature” arcs—that of the Queen. But like all positive archetypes, the Queen’s potential for further transformation is “shadowed” by the possibility of her slipping instead into either of two counter-archetypes—the Snow Queen and the Sorceress. The Snow Queen represents the passive polarity within the Queen’s shadow; the Sorceress represents the aggressive polarity.

A character who makes it through the Hero Arc is a character who has graduated into a brave new world—the Second Act of the life cycle of archetypal character arcs. This section of life, which deals with questions of relationship and power, begins with the first of the “mature” arcs—that of the Queen. But like all positive archetypes, the Queen’s potential for further transformation is “shadowed” by the possibility of her slipping instead into either of two counter-archetypes—the Snow Queen and the Sorceress. The Snow Queen represents the passive polarity within the Queen’s shadow; the Sorceress represents the aggressive polarity.

As with all of the positive archetypes, the Queen’s journey is characterized not just by the external antagonists she faces in bringing order to her Kingdom, but just as much by her personal inner struggle against the lure of her own shadow archetypes.

Instead of rising up to protect her family (whether literal or symbolic), she may “freeze” into the selfish and numb passivity of the Snow Queen—someone who cannot muster the courage and strength to protect those she loves, largely because she has not properly learned the lessons of the First Act in gaining the ability to protect and care for herself.

It is also possible the Queen may instead succumb to the alluring but false power of her aggressive form—the Sorceress. In so doing, she forfeits her true responsibility to become a selfless leader of those she loves, instead even vampirically manipulating those in her charge in order to meet her own needs.

The Heroine’s Journey by Gail Carringer (affiliate link)

By the time we reach the archetypal character arcs of the Second Act, we often start seeing some familiar faces from the previous arcs showing up in supporting roles. Here, it’s the Maiden and the Hero. And not surprisingly, the negative forms of the Queen (and all later archetypes) are almost inevitably the villains in the younger arcs. The Snow Queen and (particularly) the Sorceress most frequently turn up in the Maiden Arc—symbolically representing the Too-Good Mother or Devouring Mother or Evil Step-Mother from which the young person must individuate. In delineating “villainous” Queens, Gail Carringer makes special note, in her book The Heroine’s Journey, about the Queen archetype’s inherent relationship to “network-building”:

If she builds networks, only to sever them at the tiniest hint of betrayal, she’s a great villain. If she sees her power in ruling over others and telling them what to do, or manipulating them into it, rather than asking them because she understands their strengths and delegates accordingly—she’s a villain.

The Hero Within by Carol S. Pearson (affiliate link)

These negative counter-archetypes stand in stark contrast to the nurturing and growth-encouraging potential of a true Queen—who overcomes her own insecurities in order to foster the growth arcs of her young wards. Part of the Queen’s struggle is simply to understand the negative potential within her own arc, by recognizing the signs of the Snow Queen and Sorceress. In The Hero Within, Carol S. Pearson notes:

Understanding archetypes and their positive manifestations operates as a kind of psychological inoculation against their sides (which are often called shadow sides); by being exposed to archetypes and becoming aware of how they operate in us, we can learn to balance, and sometimes even supplant, their more negative aspects. Anything we repress, including archetypes, forms a shadow that can possess us in its negative or even demonic form. Freedom comes with consciousness.

Once again with our series-wide reminder: The arcs and their related archetypes are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. This is primarily indicating the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together all six primary life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I will use feminine pronouns in relation to the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns in relation to the masculine arcs, archetypal representations within these journeys can be of any gender.

The Snow Queen: A Passive Refusal to Fight for What She Loves

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

The Snow Queen is one of the saddest archetypes. She is still relatively young, still in the first half of her life. But life itself seems to already have left her. She moves through life as if through a fog. Caroline Myss, in Sacred Contracts, notes that the Snow Queen is not the only one who suffers as a result:

The Ice Queen rules with a cold indifference to the genuine needs of others—whether material or emotional.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

The chronology of her life has inevitably pushed her along life’s path to some practical degree. She’s not a Damsel any longer, living with her parents. She has perhaps even sketched what looks, on the outside, to be a Hero Arc. The difference here between someone who has truly completed the Hero Arc by individuating into a mature adult versus someone who is “only acting the part” may be largely internal. Usually, it has to do almost entirely with whether or not the character took the true Quest her heart called her to take—or whether she simply took the passive road—the Coward‘s road—by sleepwalking down the path laid out before her by others. Or as Clarissa Pinkola Estés says in Women Who Run With the Wolves:

Some women … give up their life’s dream [and] surrender their true calling in order to lead what they hope will be a more acceptable, fulfilling, and more sanitary life.

She is now at the stage of her life when she expected to be “grown up.” As an adult, she is responsible to other people and specifically to the younger people who are rising up behind her. But she not only has little to give, since she has not properly completed her own initiations, but in her heart of hearts she is still that fair Damsel desiring to be taken care of.

As with all the passive polarities, she is governed by Fear. What she is most afraid of is Love. However much she may crave it, she can never let it fully in because it demands too much—too much maturity, too much responsibility, too much reality.

And so when the threat comes to her Kingdom and her family, she is unequipped to rise to its challenges. At best, she categorizes herself with her children, begging that she too should be saved and taken care of by someone else. At worst, she simply lets the Invaders steal away her children in the hope that at least she might be left in peace.

The Snow Queen’s Potential Arcs: Positive and NegativeThe Snow (or Ice) Queen of fairy and folk tale is often portrayed as a beautiful woman living alone in a palace of ice—who must be rescued (often by children or a young Hero) who warm her frozen heart with the revelation of Love. Estés speaks of forgiveness:

Forgiveness…. does not mean giving up one’s protection, but one’s coldness. One deep form of forgiveness is to cease excluding the other, which includes ceasing to stiff-arm, ignore, act coldly toward, patronizing and phony. It is better for the soul-psyche to closely limit time with people who are difficult for you than to act like an unfeeling manikin.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Right there, we can see the deep and beautiful potential within the Snow Queen for a positive arc into a true Queen. The lesson she missed in failing to complete the previous Hero Arc was, in a word, Love. Before she can go on to claim the ruling principle of the true Queen—i.e, Order—she must first be thawed by that Love.

As indicated in the old tales, she may be saved from herself by her own children, who she then will save from the larger threats against the Kingdom. Or she may be saved by the Love of a questing Hero who, within his own arc, submits his power to her as the thing in his life he is finally willing to fight and die for.

But, of course, the Snow Queen may also remain inured within her passivity, and her story may spiral into deep tragedy as her children, or whoever she is responsible for, are plunged into their own tragedies (or at least difficulties) through her lack of responsibility. Whether through the depredations of Invaders or because her family grows up enough to “move on,” the end of her story will find her all alone.

Worse still, she may summon the energy to rise out of her passivity only to hurtle into the full-on destructive manipulation of her aggressive polarity—the Sorceress.

The Sorceress: An Aggressive Refusal to Do What Is Best for What She LovesIn the Snow Queen, we find the shadow archetype of someone who, even in mid-life, has not yet found a true and nourishing flow of Love. We see this same core problem in the Sorceress, but unlike her passive partner, the Sorceress is at least trying to take control of her situation and get her needs met—however misguidedly.

In the article “How Not to Fall in Love with the Anima/Animus,” Sinéad Donohoe makes an interesting note that can be seen to apply to this particular shadow archetype:

As she appears in myth, the temptress is the damsel whose cries for rescue went unheeded, and who has been allowed to perish.

The Sorceress is the Vixen who wasn’t given the support and resources she needed to healthily individuate from her birth family, just as she is also the Bully who used whatever power was available to meet personal needs. Now, in the Second Act of her life cycle, she finally has some freedom from and power over others. But because of her fundamental feeling of lack and her distrust of true Love, she uses any and all means at her disposal to meet her needs by securing resources from others. By this point, many of the people she manipulates are those who are more vulnerable than she is and for whom she herself is now responsible in some way.

In reference to the shadow form of what she calls “the Altruist,” Pearson offers some examples of how this Sorceress energy can manifest in recognizable modern situations:

[People in the shadow form of] the Altruist … will be unable—no matter how hard they work at it—to sacrifice truly out of love and care for others, and their sacrifice will not be transformative. If they sacrifice for their children, the children must then pay and pay and pay—by being appropriately grateful, by living the life the parents wish they had lived, in short, by sacrificing their own lives in return. It is this pseudo-sacrifice, which really is a form of manipulation, that has given sacrifice a bad name.

Virtually everyone these days seems to understand how manipulative the sacrificing mother can be, but another, equally pernicious version is the man who works at a job he hates, says he does it for his wife and children, and then makes them pay by deferring to him, protecting him from criticism or anger, and making him feel safe and secure in his castle. Such a man nearly always requires his wife to sacrifice her own journey in his drama of martyrdom. In these two cases and in others, the underlying message is: “I’ve sacrificed for you, so don’t leave me; stay with me, feed my illusions, help me feel safe and secure.

However unconsciously, the Sorceress preys upon her dependents while they are young and then tries to trap them in a perpetual dependence on her by preventing them from taking their own individuating arcs of Maiden and Hero.

The Sorceress’s Potential Arcs: Positive and NegativeThe deeper a character gets into the life arcs’ shadow archetypes, the harder it can be to pull free. But redemption is always possible (although it can mean reverting to previous positive arcs that were never properly completed).

Like all the aggressive polarities, the Sorceress’s deep pit of problems offers the opportunity for huge positive arcs. If she can somehow find the courage to recognize, acknowledge, and address her own deeply entrenched negative patterns, she may yet find the strength to rise into the true Queen Arc of responsible leadership. This can be the powerful midlife story of someone who has followed the company line all her life, to her own detriment, only to realize she’s living someone else’s life. She chucks it all out the window and finally takes off on the Hero’s Quest she should have taken many years ago.

But she may also fail to break her own destructive patterns. She may remain a Sorceress—an antagonist to other people’s own growth arcs—or she may devolve further into a full-blown despot. By “upping” her power from mere manipulation to full-on oppression, she can take a shadow version of the Queen Arc and end up, not a responsible and loving King, but a hideous and death-dealing Tyrant.

Key Points of the Queen’s Shadow ArchetypesFor easy reference and comparison, I will be sharing some scannable summations of each arc’s key points:

Passive Shadow Archetype: Snow Queen is Defensive (to protect from consequences of Love)

Aggressive Shadow Archetype: Sorceress is Manipulative/Vampiric (aggressive use of Love)

Positive Queen Arc: Protector to Leader (moves from Domestic World to Monarchic World)

Queen’s Story: A Battle.

Queen’s Symbolic Setting: Kingdom

Queen’s Lie vs. Truth: Control vs. Leadership

“Only my loving control can protect those I love.” versus “Only wise leadership and trust in those I love can protect them and allow us all to grow.”

Queen’s Initial Motto: “We, the True Believers.”

Queen’s Archetypal Antagonist: Invader

Queen ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Snow Queen finally acts in Love for her children by accepting Responsibility.

Or Sorceress learns to submit her selfish Love to the greater love of Responsibility.

Examples of Snow Queen and Sorceress ArchetypesExamples of the Snow Queen and Sorceress archetypes include the following. Click on the links for structural analyses.

Snow Queen

Lady Dedlock in Bleak HouseMary Crawley in Downton Abbey (she also displays Bully qualities, as noted last week, but she exhibits more of the Snow Queen as she gets older)Jon Snow in Game of Thrones (he eventually overcomes his Snow Queen tendencies to become a true leader)Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named DesireMr. Darcy in Pride & PrejudiceSorceress

Tai-Lung in Kung-Fu Panda Loki in Thor Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind Joan Crawford in Mommie DearestCommodus in Gladiator Mrs. Elton in EmmaCersei Lannister in Game of ThronesRodmilla de Ghent (Evil Step-Mother) in Ever AfterStay Tuned: Next week, we will study the shadow archetypes of the King: the Puppet and the Tyrant.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcThe Mage ArcIntroduction to the 12 Negative ArchetypesThe Maiden’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Hero’s Shadow ArchetypesWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any further examples of stories that feature either the Snow Queen or the Sorceress? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 11: The Queen’s Shadow Archetypes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 12, 2021

Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 10: The Hero’s Shadow Archetypes

Here in the 21st Century, we often have a confused relationship with the Hero archetype. On the one hand, he is everywhere and we love him and resonate with him. On the other hand, his sheer omnipresence has inevitably highlighted his negative counter-archetypes in almost equal force. This is because wherever we find a would-be Hero, we also find the potential for his regression into the Coward and the Bully.

Here in the 21st Century, we often have a confused relationship with the Hero archetype. On the one hand, he is everywhere and we love him and resonate with him. On the other hand, his sheer omnipresence has inevitably highlighted his negative counter-archetypes in almost equal force. This is because wherever we find a would-be Hero, we also find the potential for his regression into the Coward and the Bully.

This is not because the Hero is any more flawed than any of the other primary archetypal character arcs. As we’ve seen, every positive archetype is partnered with a polarity of passive/aggressive shadow archetypes. But the Hero’s negative archetypes are particularly interesting (and cautionary) simply because of the profound and implicit pervasiveness of the Hero’s Journey in the literature and film of the last century. We are perhaps more apt to recognize the problems inherent within the Hero Arc simply because those problems are often the very ones that stymie us personally and culturally.

King, Warrior, Magician, Lover by Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette (affiliate link)

In their classic examination of masculine archetypes, King, Warrior, Magician, Lover, Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette point out the inherent, if comparative, immaturity found within the Hero Arc:

There is much confusion about the archetype of the Hero. It is generally assumed that the heroic approach to life, or to a task, is the noblest, but this is only partly true. The Hero is, in fact, only an advanced form of Boy psychology—the most advanced form, the peak, actually, of the masculine energies of the boy, the archetype that characterizes the best in the adolescent stage of development. Yet it is immature, and when it is carried over into adulthood as the governing archetype, it blocks men from full maturity.

As we’ve already explored in the post on the Hero Arc, this archetype is only the second in a cycle of six. It is the final journey of the “youthful” stage of life, which may be thought of as life’s First Act. The arc itself is fundamentally about growing up in the fullest sense—not just individuating (which should be accomplished within the preceding Maiden Arc), but responsibly reintegrating into society as a full-fledged adult.

The Hero Within by Carol S. Pearson (affiliate link)

It is an arc that comes for us all at some point—but one that, despite its prevalence, is misunderstood by modern society simply because we do not understand what comes next (i.e., the mature “adult” arcs of Queen and King). As Carol S. Pearson notes in The Hero Within, this is important beyond just character arcs and literature:

When the heroic journey was thought to be for special people only, the rest of us just found a secure niche and stayed there. Now we have no secure places in which to hide and be safe. In the contemporary world, if we do not choose to step out on our quest, it will come to get us. We are being thrust on the journey. That is why we all must learn its requirements.

If, however, the Hero fails to complete his transformation into the mature arcs of life’s Second Act, he is very likely to instead transition sideways into his negative shadow archetypes—the Coward and the Bully. The Coward represents the passive polarity within the Hero’s shadow, the Bully the aggressive polarity.

Once again with our series-wide reminder: The arcs and their related archetypes are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. This is primarily indicating the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together all six primary life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I use feminine pronouns in relation to the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns in relation to the masculine arcs, archetypal representations within these journeys can be of any gender.

The Coward: A Passive Refusal to Take ResponsibilityAs with all of the passive counter-archetypes, we find the presence of the Coward implicit within the beginning of the Hero Arc. However much the Hero may long for adventure in “the great wide somewhere,” he is not about to unequivocally volunteer. In the very beginning of his journey, he will display his immaturity in his laziness, complacency, or even outright cowardice.

Like Luke Skywalker at the beginning of his journey, he may whine and gripe a bit about his meaningless life in the middle of nowhere, but he won’t summon the courage to leave it until the Call to Adventure arrives (and even then he starts out at least symbolically refusing it).

There are good reasons for this. However much humans may need to grow and mature, our entire concept of survival is built around maintaining a status quo. This is why the Inciting Event and First Plot Point in a story, which force the Hero out of his Normal World, are inevitably “bolts from the blue”—signifying the arrival of conflict from outside the Hero’s safe world. Pearson says:

…although some people take off on the quest with a high sense of adventure, many experience it as thrust upon them by their feeling of alienation or claustrophobia, by the death of a loved one, or by abandonment or betrayal.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

This is normal—indeed, archetypal. Part of the Hero Arc lies within the Hero’s own inner struggle against the Coward. But the Coward begins to prevail if the Hero’s initial Refusal of the Call is not quickly overcome. In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell notes, rather dourly:

Often in actual life, and not infrequently in the myths and popular tales, we encounter the dull case of the call [to adventure] unanswered; for it is always possible to turn the ear to other interests. Walled in by boredom, hard work, or “culture,” the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved…. The myths and folk tales of the whole world make clear that the refusal is essentially a refusal to give up what one takes to be one’s own interest. The future is regarded not in terms of an unremitting series of deaths and births, but as though one’s present system of ideals, virtues, goals, and advantages were to be fixed and made secure.

Like the Damsel before him, the Coward often hides behind a guise of seeming wisdom and maturity. Why take risks? Why not let others endanger themselves for the good of all? After all, somebody has to stay behind and take care of things. But this is false maturity. Once the Call arrives (whatever its form—mythic or modern), it is not the Hero’s role to hold the fort. That task belongs to others—the Queen and the King. If he chooses to ignore this, he is doing it for selfish reasons and not for the good of his community—and, ironically, as Pearson points out, he will eventually suffer for it just as much as if he had risked all:

The Coward’s Potential Arcs: Positive and NegativeMany people subscribe to the false idea that being heroic means you have to suffer and struggle to prevail. The fact is, most of us will experience difficulty whether or not we claim the heroic potential within us. Moreover, if we avoid our journeys, we also may feel bored and empty.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

As noted, the Coward is already a kernel waiting to sprout within the Hero Arc. In many ways the beliefs of the Coward comprise the Lie the Hero Believes—and which the Hero will overcome within a Positive-Change Arc.

It should be noted his cowardice may also be projected outward and represented by supporting characters. Allowing supporting characters to “act out” parts of the protagonist’s inner self is also a deeply powerful thematic presentation. We can see this in such stories as Harry Potter, in which Harry’s lovable best friend Ron Weasley usually represents the Coward—even though he inevitably redeems himself at the end of every installment within the series.

In Star Wars, the Coward can be seen to be represented by Threepio, who is always the “voice of caution.” Often, but not always, this iteration of the Coward aligns with what, in the Dramatica system, is termed the Reason character.

If the Coward does not summon enough courage to embrace his journey (whether at the very beginning of the story or later after he has been thrust upon it against his will), he will fall prey to one of two possible fates.

He might cling ever tighter to his fear and immaturity, which will cause him to stultify his growth. Even if life’s chronology pushes him ahead into later forms of adulthood and elderhood, he will remain frozen in the passive archetypes—Snow Queen, Puppet, Hermit, and Miser.

The second possibility is that he will pluck up his resolve enough to face his challenges head-on. In so doing, he will discover that he does, in fact, possess more personal power than he realized. But, again, his forward progression stalls. Instead of using this power to arc into the love and social responsibility of a full-blown Hero, he will instead use this power selfishly (and ultimately still from a place of fear) by turning into the Bully.

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

In The Virgin’s Promise, Kim Hudson talks about the underlying truths that join both of the potentially negative archetypal polarities of the Hero:

The Bully: An Aggressive Refusal to Take ResponsibilityThe choice of Coward emphasizes the unspoken quality of courage in the term Hero, and points out a deep and consistent truth about Villains and Shadow figures—they are cowards, choosing a selfish and greedy path rather than the heroic path of self-sacrifice for the greater good.

At first glance, the Bully can seem powerful—more powerful even than the true Hero. But like all aggressive polarities within the shadow archetypes, his power contains an inherent weakness. It is “stuck”—brittle—instead of free-flowing and transformative like the Hero’s.

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

In many ways, the Bully is the true shadow form of the Hero, as called out by Caroline Myss in Sacred Contracts:

From a shadow perspective, the Hero can become empowered through the disempowerment of others.

Unlike the Coward, the Bully may well have at least gotten a “passing grade” on individuating from his authority figures, in the previous arc. But he has not only stalled out in re-integrating into society in a healthy and responsible way, he has in fact blocked himself (and/or been obstructed by equally regressive social influences) from doing so. If the Hero is about arcing into Love, the Bully is ultimately an archetype stuck in hatred. Deep down, he has embraced a societal wound in a way that not only prevents his healing and growth, but also causes him to fear and resent the idea of reintegrating into a larger community.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

And so, even if he surrounds himself with “minions,” he stands apart from the cycle of life. Like all aggressive archetypes, he avoids the painful challenges of true growth and instead tries to control reality. As so often happens in cycles of abuse, he becomes the very thing he himself fears and hates. In Women Who Run With the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés speaks a familiar truth:

The Bully’s Potential Arcs: Positive and NegativeMost often we wound others where, or very close to where, we have been wounded ourselves.

But there is always hope. As with all of the shadow archetypes, the Bully is not inevitably lost. Indeed, his retained flicker of inherent personal power—and his refusal to completely surrender it—signals the potential for positive transformation, as Myss (who is always quick to examine the “positive” side of the negative archetypes and vice versa) points out:

The archetype of the Bully manifests the core truth that the spirit is always stronger than the body.

Indeed, any ultimately positive Hero Arc may start out emphasizing the Bully side of the character’s polarity. Although this can present challenges for the author (and the readers), since the Bully is often unlikable as a character, it does offer the opportunity for a deep arc, along the lines of what Moore and Gillette eulogize:

The “death” of the Hero is the “death” of boyhood, of Boy psychology. And it is the birth of manhood and Man psychology. The “death” of the Hero in the life of a boy (or a man) really means that he has finally encountered his limitations. He has met the enemy, and the enemy is himself. He has met his own dark side, his very unheroic side. He has fought the dragon and been burned by it; he has fought the revolution and drunk the dregs of his own inhumanity. He has overcome the Mother and then realized his incapacity to love the Princess. The “death” of the Hero signifies a boy’s or man’s encounter with true humility. It is the end of his heroic consciousness.

The Wounded Woman by Linda Schierse Leonard (affiliate link)

But, of course, the fight for his better self may not end triumphantly, and the Bully may instead arc more deeply into aggression by rejecting the assimilation of “Love” found at the end of a true Hero Arc. In The Wounded Woman, Linda Schierse Leonard speaks of the Bully archetype in terms of a woman’s psyche and inner destructive animus, but her words hold equally true for anyone:

It is then that the masculine becomes brute-like and sacrifices not only the outer woman but also its inner feminine side.

If the Bully is deeply wounded and defeated in the outer conflict, it is also possible he may lose his willpower and resolve, instead reverting to the passive Coward. Indeed, because the Coward’s fear (of life, love, and power) lie at the heart of the Bully, the Coward is always with him. But only if his aggressive actions in the exterior conflict prove personally destructive will he abandon them.

Key Points of the Hero’s Shadow ArchetypesFor easy reference and comparison, I will be sharing some scannable summations of each arc’s key points:

Passive Shadow Archetype: Coward is Ineffectual (to protect from consequences of Courage)

Aggressive Shadow Archetype: Bully is Destructive (aggressive use of Courage)

Positive Hero Arc: Individual to Protector

Hero’s Story: A Quest.

Hero’s Symbolic Setting: Village

Hero’s Lie vs. Truth: Complacency and/or Recklessness vs. Courage

“My actions are insignificant in the overall scope of the world.” versus “All my actions affect those I love.”

Hero’s Initial Motto: “I, the powerful.”

Hero’s Archetypal Antagonist: Dragon

Hero ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Coward finally uses his Strength because he learns to Love and wants to defend what he loves.

Or Bully learns to submit his Strength to the service of Love.

Examples of the Coward and Bully ArchetypesExamples of the Coward and Bully archetypes include the following. Click on the links for available structural analyses.

Coward

Ron Weasley in Harry Potter The Narrator in Fight Club Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of OzThreepio in Star Wars Paris in Troy Edmund Sparkler in Little Dorrit Richard Carstone in Bleak HouseLambert in AlienBully

Thor Odinson in Thor John Bender in The Breakfast ClubEdmund Pevensie in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe Draco Malfoy in Harry Potter Tyler Durden in Fight Club Regina George in Mean GirlsBill Sikes in Oliver TwistFannie in Little Dorrit Herbert Sobel in Band of BrothersGaston in Beauty & the BeastSid Phillips in Toy Story Emily in The Devil Wears PradaMary Crawley in Downton AbbeyStay Tuned: Next week, we will study the shadow archetypes of the Queen: the Snow Queen and the Sorceress.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcThe Mage ArcIntroduction to the 12 Negative ArchetypesThe Maiden’s Shadow ArchetypesWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any further examples of stories that feature either the Coward or the Bully? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 10: The Hero’s Shadow Archetypes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 5, 2021

Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 9: The Maiden’s Shadow Archetypes

In so many ways, we view life as a story. Within the lifelong journey of this story, the first challenge is that of becoming an autonomous individual—an independent and responsible adult. However obvious that may be, the journey itself cannot be taken for granted. Indeed, although we may all grow up chronologically, the struggle to truly leave childhood behind is one that is often prolonged and even aborted for a great many of us.

In so many ways, we view life as a story. Within the lifelong journey of this story, the first challenge is that of becoming an autonomous individual—an independent and responsible adult. However obvious that may be, the journey itself cannot be taken for granted. Indeed, although we may all grow up chronologically, the struggle to truly leave childhood behind is one that is often prolonged and even aborted for a great many of us.

Within the model of the six archetypal character arcs, this first initiatory journey is represented by the Maiden. She faces external antagonists, metaphorically (and often literally) represented by the Too-Good Mother, the Naive Father, and the Predator-Groom who would devour her youth and innocence. But she also faces internal danger from the shadowy counter-archetypes that, out of fear and egoism, would prevent her from embracing a new perspective and completing her journey.

For the Maiden, these shadow archetypes are represented by the Damsel and the Vixen. The Damsel represents the passive polarity within the Maiden’s shadow, the Vixen the aggressive polarity.

Before we dig into these important archetypes, I will say a quick word about both of their titles, since both archetypes are currently fraught with controversy in modern portrayals.

The Damsel, of course, represents the much despised damsel in distress—usually objectified within the Hero’s Journey (although not without cause, as we discussed in the Hero’s post, since rescuing the Damsel—as played by any character—is an important moment within the Hero Arc, especially since the Damsel can be seen to represent not just an individual character, but a part of the Hero’s own psyche—as do all characters within any particular journey).

The Heroine’s Journey by Gail Carringer (affiliate link)

Recognizing how the Damsel has often been reduced to a stereotype is important, but it is also important not to discredit the psychological reality of the archetype itself. In The Heroine’s Journey (which mostly speaks to the Queen Arc), paranormal romance author Gail Carringer points out:

The damsel trope is a profoundly powerful representation of weakness. We authors must be wary of who appears weak or victimized in our books, as the message this sends can detrimentally impact an audience’s sense of self-worth.

An equally troublesome archetype/stereotype in today’s media is what I have (after long deliberation) chosen to term the Vixen. Kim Hudson, author of The Virgin’s Promise, and others use the name Whore for this archetype, but to me this seems a bit much for such a young archetype. Similar to the Damsel, the Whore is a viable archetype—and yet it has been used so often to stereotype female sexuality that it requires the same caution as Carringer gives the Damsel.

It is important to recognize that the comparatively powerless Maiden has fewer resources at her disposal when in her aggressive shadow archetype than do any of the successive archetypes. Indeed, instead of “aggressively” controlling others as she would be able to do in the aggressive forms of later arcs (such as the King/Tyrant), she is only able to use what skills her childhood has so far given her. This often takes the form less of actual aggression with others and more of attempts at manipulation. Inevitably, this shadow archetype is one of the most tragic, since it represents a vulnerable character who is ultimately selling off far more of herself than she is able to get in return from others.

That said, I have chosen not to use the term Whore (although you’ll see it in some of the sources I quote), in case it might be a stumbling block, and have instead chosen the (admittedly also not entirely problem-free) title of Vixen.

Once again with our series-wide reminder: The arcs and their related archetypes are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. This is primarily indicating the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together all six primary life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I will use feminine pronouns in relation to the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns in relation to the masculine arcs, archetypal representations within these journeys can be of any gender.

The Damsel: A Passive Refusal to Initiate Into AdulthoodLike all the passive archetypes, the Damsel carries a frozen shard of fear in her heart. As the youngest of the negative archetypes, her fear is largely unformed and unnamed. There is a deep innocence to it. She has depended on others all her life to take care of her, and (unlike the Vixen) she has probably been comparatively lucky in that there were people to do so.

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

But via her very innocent cared-for-ness, she has never been challenged to rise up. Even if the fear is implicit and unnamed, she is afraid of having to fend for herself—because not only has she never done it, she has also probably been discouraged from doing so. In Sacred Contracts, Caroline Myss notes:

The shadow side of this archetype mistakenly teaches old patriarchal views that women are weak and teaches them to be helpless and in need of protection. It leads a woman to expect to have someone else who will fight her battles for her while she remains devoted and physically attractive and concealed in a castle.

Like Rapunzel in Tangled, the Damsel has been told “Mother Knows Best” and “kept safe” through fearsome stories of the wicked adult world.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

But as Clarissa Pinkola Estés points out in Women Who Run With the Wolves (which is basically a guide to overcoming the Damsel):

…the reward for being nice in oppressive circumstances is to be mistreated more.

Or as Zora Neale Hurston says in one of my all-time favorite quotes:

If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.

Most of the passive archetypes represent a sort of faux “goodness”—or at least an attempt on the character’s part to avoid being bad. But this avoidance is not active; it is passive. Because it is rooted in fear, it ultimately leads the character to avoid doing the wrong thing by simply… doing nothing. Estés says:

An incompletely initiated woman in this depleted state erroneously thinks she is deriving more spiritual credit by staying than she thinks she will gain by going. Others are caught up in, as they say in Mexico, dar a algo un tirón fuerte, always tugging at the sleeve of the Virgin, meaning they are working hard and ever harder to prove that they are acceptable, that they are good people.

The Damsel is often represented by another familiar archetype—that of the Good Girl, or sometimes Daddy’s Little Girl. Estés again:

It is interesting to note that daughters who have naive fathers often take far longer to awaken…. It can be said that the father, who symbolizes the function of the psyche that is supposed to guide us in the outer world, is, in fact [in this representation], very ignorant about how the outer world and the inner world work in tandem. When the fathering function of the psyche fails to have knowing about issues of soul, we are easily betrayed.

In the beginning, while still a Child, the Damsel’s apparent goodness may seem like maturity. She may be praised for being too “wise” and “mature” to make the seemingly reckless mistakes of the Maiden—which she herself confuses with the unhealthy aggression of the Vixen.

But as time goes on, and life demands she grow up whether she’s ready or not, her true lack of maturity begins to show through. She is not prepared to take care of herself. She lacks both the wisdom and the experience—and, contrary to what she always believed, there will come a day when no one rides in to save her. At the moment when she is truly confronted with the challenges of autonomy, her supposed maturity will leave her defenseless.

The Damsel’s Potential Arcs: Positive and Negative

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Within most Maiden Arcs, the protagonist will almost always start out in a very Damsel-like space. This means that, inherent within the Damsel, is all of the Maiden’s potential. Even if she gets stuck in the Damsel space far beyond what would be chronologically preferable, she is like a seed in the winter ground—all the necessary energy for transformation and growth is still latent within her. Particularly since the Child/Damsel marks the beginning of the entire cycle of life arcs, there resides within her great potential for a Positive-Change Arc.

Equally, however, there is the potential for a Negative-Change Arc. If she stays too long a Damsel, she may devolve into her aggressive polarity—the Vixen. But she may also simply regress deeper into a determinedly “innocent” and “helpless” state, refusing to face life head on and instead relying on Blanche DuBois’s “kindness of strangers” to get through life. But as with Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire, this determined refusal to grow will only nudge her down the line of passive, stunted archetypes as she grows older.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell writes:

The Vixen: A Manipulative/Aggressive Attempt to Avoid the Initiation Into AdulthoodThe literature of psychoanalysis abounds in examples of … desperate fixations. What they represent is an impotence to put off the infantile ego, with its sphere of emotional relationships and ideals. One is bound in by the walls of childhood; the father and mother stand as threshold guardians, and the timorous soul, fearful of some punishment, fails to make the passage through the door and come to birth in the world without.

Like all the aggressive polarities, the Vixen possesses at least a little more consciousness than the Damsel. She sees enough to recognize her antagonists, to resent restraint upon her existence, and to take advantage of what power is immediately available.

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

Unlike the Damsel, her courage extends beyond “doing nothing out of fear of doing the wrong thing.” But this is not to say that she, too, isn’t terrified of growing up and totally claiming her own power—along with its responsibility. What courage she has is not enough to let her brave the soul-changing difficulties of a true Maiden Arc—which would end with her individuating from her authority figures. The result is that, despite whatever power she believes she wields through her rebellion and manipulation, she is just as helpless as the Damsel. Or as Kim Hudson puts it in The Virgin’s Promise:

The Whore believes she must appease or please people and is thereby a victim.

Just as the Damsel is often represented as the Good Girl, the Vixen is inevitably the Bad Girl. She’s mouthy and defiant in the face of authority—but only to a point. Her seeming power and independence, in comparison to the Damsel (and even the Maiden in the beginning), is a facade. As soon as anyone stronger leans on her, she collapses—sometimes out of fear, but usually simply because she isn’t strong enough to fight back.

And so she resorts to sneaky and manipulative methods for getting what she wants. She “sells” herself by devaluing her worthiness and right to mature into a full-fledged Maiden Arc. Instead, she hides behind the seeming power of her rage. Estés observes:

When a woman has trouble letting go of anger or rage, it’s often because she’s using rage to empower herself.

The Wounded Woman by Linda Schierse Leonard (affiliate link)

The Vixen is in a hard place. She refuses to fully accept the authority of those who govern her world (and who probably do protect and provide for her in at least some measure), but she also finds herself unable to entirely accept responsibility for herself by fully claiming her personal sovereignty. In The Wounded Woman, Linda Schierse Leonard points out:

The Vixen’s Potential Arcs: Positive and Negative…those daughters who have reacted against the too authoritarian father are likely to have problems accepting their own authority.

The Vixen offers the inherent potential for a dramatic Positive-Change Arc. Like all the shadow archetypes, she too will probably show her face to at least some degree in any Maiden Arc.

Caroline Myss discusses what she calls the Prostitute as one of four “Archetypes of Survival” within everyone (along with the Child, the Victim, and the Saboteur). She outlines the surprising power of this archetype and the deep potential for growth within it:

The Prostitute archetype engages lessons in integrity and the sale or negotiation of one’s integrity or spirit due to fears of physical and financial survival or for financial gain. This archetype activates the aspects of the unconscious that are related to seduction and control, whereby you are as capable of buying a controlling interest in another person as you are in selling your own power. Prostitution should also be understood as the selling of your talents, ideas, and any other expression of the self—or the selling-out of them. This archetype is universal and its core learning relates to the need to birth and refine self-esteem and self-respect.

Of course, the Vixen also holds the potential for stagnation and even deeper devolution into the shadow archetypes. Instead of using her inherent strength to reorient herself into a powerful Maiden Arc, she might instead follow a tragic Negative Arc in which she becomes even more victimized by the depredations and neglect of her authority figures. One more quote from Estés:

Women who try to make their deeper feelings invisible are deadening themselves. The light goes out. It is a painful form of suspended animation.

Or the Vixen might summon the strength to grow—not into the following positive archetype of the Hero, but rather into the subsequent aggressive counter-archetype of the Bully (to be discussed next week). Leonard speaks of this in an interesting way:

Key Points of the Maiden’s Shadow Archetypes…too often in order to break out of the puella [eternal girl] dependency, they imitate the masculine model and so perpetuate the devaluation of the feminine.

For easy reference and comparison, I will be sharing some scannable summations of each arc’s key points:

Passive Shadow Archetype: Damsel is Submissive (to protect from consequences of Dependence)

Aggressive Shadow Archetype: Vixen is Deceptive (aggressive use of Dependence)

Positive Maiden Arc: Innocent to Individual (moves from Protected World to Real World)

Maiden’s Story: An Initiation.

Maiden’s Symbolic Setting: Home

Maiden’s Lie vs. Truth: Submission vs. Sovereignty.

“Submission to authority figures is necessary for survival.” versus “Personal sovereignty is necessary for growth and survival.

Maiden’s Initial Motto: “We, the clan.”

Maiden’s Archetypal Antagonist: Authority/Predator

Maiden ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Damsel finally owns her Potential by embracing her Strength.

Or Vixen learns to wield her true Potential with true Strength.

Examples of the Damsel and Vixen ArchetypesExamples of the Damsel and Vixen archetypes include the following. Click on the links for structural analyses.

Damsel

Paula Alquist in GaslightMrs. de Winter in RebeccaNeil Perry in Dead Poets SocietyBeth in Little Women Celie Johnson in The Color PurpleDora Copperfield in David CopperfieldRapunzel in TangledVixen

Gwendolen Harleth in Daniel DerondaPip in Great ExpectationsCharlotte Flax in MermaidsCathy Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights Antonio Salieri in Amadeus (among other aggressive counter-archetypes)Lydia Bennet in Pride & Prejudice Abigail in The FavouriteStay Tuned: Next week, we will study the shadow archetypes of the Hero: the Coward and the Bully.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcThe Mage ArcIntroduction to the 12 Negative ArchetypesWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any further examples of stories that feature either the Damsel or the Vixen? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 9: The Maiden’s Shadow Archetypes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 29, 2021

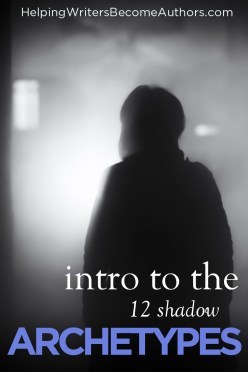

Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 8: Introduction to the 12 Shadow Archetypes

Where there is light, there is shadow. Where is there is a right way to do things, there are usually several ways to do it wrong. So it goes with archetypal character arcs and their potential shadow archetypes—of which there are two for every positive archetype.

Where there is light, there is shadow. Where is there is a right way to do things, there are usually several ways to do it wrong. So it goes with archetypal character arcs and their potential shadow archetypes—of which there are two for every positive archetype.

Over the last few months, we have explored six successive “life arcs,” represented by the Positive-Change Arcs of six primary archetypes—the Maiden, the Hero, the Queen, the King, the Crone, and the Mage. Each of these positive archetypes represents a rising above the limitations of the previous archetype in the cycle. But they also inherently represent a struggle with related “shadow” or negative archetypes.

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

Specifically, there are twelve negative archetypes—two for each positive archetype. Each positive archetype sits at the top of a triangle that is completed by a potential negative polarity between the two negative archetypes—one representing an aggressive version of the shadow archetype and the other representing a passive version. In Sacred Contracts, Caroline Myss speaks of the inherent power dynamic within this archetypal triangle:

The shadow aspects of our archetypes are fed by our paradoxical relationship to power. We are as intimidated by being empowered as we are by being disempowered.

This is why one of the primary challenges within any of the six positive archetypal arcs is that of grappling with one’s conflicting desire for and fear of autonomy. Only in integrating and accepting the responsibility for this growing power is a character able to escape the beckoning shadow archetypes and instead level up into the next “life arc.”

12 Shadow or Negative Archetypes

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

More or less classically (and with a big nod to Kim Hudson’s The Virgin Promise and Douglas Gillette and Robert L. Moore’s King, Warrior, Magician, Lover), the corresponding archetypes can be viewed like this:

1. Positive: Maiden

Passive: Damsel

Aggressive: Vixen

2. Positive: Hero

Passive: Coward

Aggressive: Bully

3. Positive: Queen

Passive: Snow Queen

Aggressive: Sorceress

4. Positive: King

Passive: Puppet

Aggressive: Tyrant

5. Positive: Crone

Passive: Hermit

Aggressive: Wicked Witch

6. Positive: Mage

Passive: Miser

Aggressive: Sorcerer

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Just as the temptation and struggle against the shadow archetypes’ corruption is inherent within all of the archetypal Positive-Change Arcs, so too are the two negative archetypes inherent within each other. Although a character representing a negative archetype will usually manifest most obviously as one or the other—passive or aggressive—they are really just two sides of the same coin. For example, inherent within any Coward, there is usually a latent Bully, just as the Bully is often a Coward at heart.

There are many ways negative archetypes can arc:

From negative to positive (a Positive-Change Arc)From positive to negative (a Corruption Arc)From passive to aggressive (a Fall Arc)From aggressive to passive (which is not exclusive to but can be seen in a Disillusionment Arc).Not at all (a negative Flat Arc, in which the character is less likely to be the protagonist and more likely to be the antagonist in someone else’s Positive-Change Arc or a negative Impact Character in someone else’s Negative-Change Arc).The Passive Counter-ArchetypesThe passive archetypes represent a fatal immaturity. No matter at what stage characters find themselves within the life arcs, their first challenge will be to resist their own sense of complacency and safety—which would keep them where they’re at. But, in fact, they have little choice about whether or not they will be called into the journey of a subsequent archetype. They can only decide whether they will grow, or whether they will resist.

The passive shadow archetypes are the result of a refusal to grow into the next arc and instead an attempt to maintain power in its former guise. For example, someone who has successfully completed the Hero Arc and is now being challenged to grow into the Queen Arc may resist the call of leadership and responsibility—and hide away within the selfish passivity of the Snow Queen. Life is demanding this character change, but the character resists, cannot overcome fear, and fails to complete proper growth—ending emotionally stunted and unfit to take on the responsibilities that life has now given.

Art and Artist by Otto Rank (affiliate link)

In Art and Artist, Otto Rank discusses the passive archetype as the “neurotic”:

If we compare the neurotic with the productive type, it is evident that the former suffers from an excessive check on his impulsive life…. Both are distinguished fundamentally from the average type, who accepts himself as he is, by their tendency to exercise their volition in reshaping themselves. There is, however, this difference: that the neurotic, in this voluntary remaking of his ego, does not get beyond the destructive preliminary work and is therefore unable to detach the whole creative process from his own person and transfer it to an ideological abstraction. The productive artist also begins … with that re-creation of himself which results in the ideologically constructed ego; [but in his case] this ego is then in a position to shift the creative will-power from his own person to ideological representations of that person and thus render it objective. It must be admitted that this process is in a measure limited to within the individual himself, and that not only in its constructive but also in its destructive aspects. This explains why hardly any productive work gets through without morbid crises of a “neurotic” nature.

In short, facing the passive archetype is one of the earliest steps in any positive archetype’s forward struggle. This fearful shadow aspect of one’s self represents what we often hear spoken of within the Hero’s Journey as the Hero’s “Refusal of the Call to Adventure.” Put simply: he’s scared. And considering the immensity of the journey before him, we all commiserate with exactly why that should be.

But if the Hero—or any other positive archetype—should succumb to this fearful part of himself, he will abort not just the journey but his own ability to grow and mature. He will get stuck as the Coward, and his own progress forward in life will become immeasurably more difficult.

The Aggressive Counter-Archetypes

The Heroine’s Journey by Maureen Murdock (affiliate link)

By contrast, the aggressive polarity of the negative archetypes represents not so much the fear of reality but the desire to control it. Although the aggressive archetypes are literally the polar opposite of the passive archetypes, the passive archetypes are still often at the root of a character’s aggression. In many ways, the aggressive archetypes represent an overcompensation in response to the character’s inner fear of change and growth. In The Heroine’s Journey, Maureen Murdock quotes Edward Whitman:

Whether creative possibilities or regressive destruction shall prevail depends not upon the nature of the archetype or myth, but upon the attitude and degree of consciousness.

Even though the aggressive archetypes appear much more proactive and productive than do the passive archetypes, they too represent a stagnation. They may be “getting things done” within their realm of activity, but they are not moving forward.

For example, a Crone who has refused to take her journey into the Mage may get stuck in the aggressive polarity of the Wicked Witch—using the not-inconsiderable power she has gleaned throughout her long life to control others and manipulate outcomes. She looks powerful, but unlike the Crone, the Witch is not expanding. She represents not just a stillness within the character’s maturation, but a stagnation—she has gotten stuck through her own passivity and fear, has refused (however unconsciously) to continue growing, and has instead turned her energy outwards upon a world she resents.

How Archetypes Relate to the Thematic Truth/LieAs we’ve already discussed, the six archetypal Positive-Change Arcs represent the character’s ability to transition away from a limiting life belief and into an acceptance of an inherent archetypal Truth.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

These same archetypal Lies/Truths are also inherent within the related negative shadow archetypes. The difference, of course, is that these negative archetypes resist the Truth. Through fear of change or desire for control, they cling to a broken version of reality. Depending on the specific type of Negative-Change Arc they are undergoing (Disillusionment, Corruption, Fall), they will encounter various opportunities to acknowledge and accept the Truth. In a legitimate Negative-Change Arc, they will fail to do so—and the metaphorical Kingdom will always suffer as a result.

How the Negative Archetypes Relate to the Positive ArcsWithin all types of archetypal stories—whether they feature protagonists with Positive or Negative Arcs—we always have the opportunity for a full cast. Just as the negative polarities are inherently present to some degree within the struggling protagonist of a Positive-Change Arc, so too is the positive archetype within the struggles of a protagonist in a Negative-Change Arc.

More than that though, we have the opportunity to externalize these struggles into the supporting cast. We can see this clearly—and have already touched on it in earlier posts—in the fact that the Hero’s Journey prominently features more advanced archetypal characters in supporting roles—-most notably the King and the Mage/Mentor.

Likewise, negative archetypes frequently show up in villain roles. I haven’t observed a hard-and-fast pattern, but it resonates that one of the powerful uses of negative archetypes within a positive-archetype story is that of presenting the protagonist with a version (usually aggressive) of the subsequent archetype. For example, a Queen almost always has to confront and overcome a Tyrant (the aggressive version of the subsequent arc of King).

Not only does this approach provide opportunities for a solid plot-theme connection, it also offers the always-brilliant chance to symbolically represent the antagonist as a shadow version of the protagonist’s potential self. As such, the antagonist can offer both temptation to the growing protagonist of the power she might wield, as well as a caution of what kind of monster she might turn into should she succumb to that temptation.

Same goes for the characters in a Negative-Change Arc story: if the protagonist is representing a negative archetype such as the Sorceress, then the rest of the cast can be used to represent supporting archetypes that deepen the thematic and symbolic narrative.

***

As you can already see—and as is always the case with negative character arcs—there are many possible variations that can arise when a character falls away from the health of the positive archetypes and into the unhealth of the negative archetypes.

This means there are many possible narratives for representing them in the protagonist of a Negative-Change Arc. As such, I won’t be offering a “mythic beat sheet” for each of the negative archetypes in the same way I have done for the positive archetypes.

Over the course of the next six posts, we will be diving a little more deeply into the partnership of each passive/aggressive polarity and talking about how you can recreate these important archetypes within your own stories.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we will study the shadow archetypes of the Maiden.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcThe Mage ArcWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Are you more drawn to writing about Positive or Negative Arcs? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 8: Introduction to the 12 Shadow Archetypes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 22, 2021

Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 7: The Mage Arc

The final two archetypal character arcs in the life cycle deal primarily with questions of Mortality—and thus inevitably with the ultimate questions about the meaning of life.

The final two archetypal character arcs in the life cycle deal primarily with questions of Mortality—and thus inevitably with the ultimate questions about the meaning of life.

Throughout this series, we’ve viewed the six “life arcs” as part of a unified story structure, or Three Acts. The First Act—featuring the Maiden and the Hero—focused on overcoming challenges of Fear in integrating the parts of oneself and individuating. The Second Act—the Queen and the King—focused on challenges of Power and on integration within relationship to others. Finally, the Third Act—the Crone and the Mage—turns its attention to Mortality and to the integration of soul and spirit.

As we discussed in last week’s post, the Crone Arc represented the complete transition of the character from the “outer” world struggles with one’s self and other people into the “inner” world struggles with more existential and spiritual crises. Although anyone who lives long enough will reach the Crone Arc at least chronologically, not everyone will accept her challenge and fulfill her difficult arc of embracing her own mortality. Therefore, even fewer among us will even get the opportunity to truly take on the deep mysteries of the powerful Mage Arc.

In part because of that fact itself, the Mage Arc is mysterious. We see it most plainly in the metaphor of fantasy stories that offer up a supernatural Mentor to a world in need. But rarely is this character the protagonist (perhaps because almost all of us relate more obviously to the younger archetypes who mirror our own positions in the cycle). Even more rarely is the Mage fully embodied in a “realistic” story (although to my mind Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird seems a possible example from a symbolic viewpoint).

Even when the Mage shows up in a real-world story, his deep, almost otherworldly wisdom inevitably brings with it a touch of the magical—as, for example, with Will Smith’s wise and mysterious caddy in the golf movie The Legend of Bagger Vance.

Sacred Contracts by Caroline Myss (affiliate link)

In Sacred Contracts, Caroline Myss notes:

The … Magician produce[s] results outside the ordinary rules of life….

This doesn’t necessarily mean the character is magical in any way. But it does mean the character has not only glimpsed but assimilated truths about life that most people don’t even know exist. By accepting his own mortality back in the Crone Arc, he has now reached a new level of transformation, objectivity, and wisdom.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

In Women Who Run With the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés speaks to this archetypal wisdom:

The mage, or magician [is] whom the king brings with him to interpret what he sees…. Such things as the split-second recall, the thousand-league vision, the hearing over miles, the empathic ability to see from behind anyone’s eyes—human or animal— … the magician … shares in these and also, traditionally, helps to maintain them and enact them in the outer world. Though the mage can be of either gender, here it is a powerful male figure similar in fairy tales to the stalwart brother who so loves his sister that he will do all to help her. The mage always has crossover potential. In dreams and in tales, he appears as a man as often as he shows up as a woman. He can be male, female, animal, or mineral, just as the crone, his female counterpart, can also affect her guises with ease.

For the Mage, who has already accepted Death, what is there left to transform? What is left, of course, is the final threshold to cross in earnest. But there is also the final temptation—to use his great power and wisdom, the riches of his entire well-spent life, not to guide those he loves but to control them in ways he has no right to. Will he surrender—or become Sorcerer?

Reminders: Once again, before we officially get started, I want to emphasize two important reminders that hold true for all of the arcs we’ve studied.

1. The arcs are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine. Primarily, this indicates the ebb and flow between integration and individuation, among other qualities. Together, all six life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation). In short, although I will use feminine pronouns for the feminine arcs and masculine pronouns for the masculine arcs, the protagonist of these stories can be of any gender.

2. Because these archetypes represent Positive-Change Arcs, they are therefore primarily about change. The archetype in which the protagonist begins the story will not be the archetype in which he ends the story. He will have arced into the subsequent archetype. The Mage Arc, therefore, is not about becoming the Mage archetype, but rather arcing out of it into the beginnings of what I’m calling “the Saint” archetype—but basically just indicating his final ascension into a “good death.”

The Mage Arc: Joining GodAlthough the Mage can be played by a younger character, the arc itself is representative of the final chapter of one’s life. The Mage represents a person who has successively and positively completed all six life arcs. This is, in fact, an unusual and extraordinary achievement. Merely reaching the end of our lives doesn’t mean we’ll get to go out as Mages. The Mage, then, is someone who put in an unfailing amount of work throughout his life, someone who has consistently sought light and truth—and been rewarded in that search.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

And now he has almost reached the end. Not only is the end of his life on earth incumbent because of his great age, but he has transcended many of the challenges that weigh us down in our earlier acts. In The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell speaks of this stage:

The ego is burnt out. Like a dead leaf in the breeze, the body continues to move about the earth, but the soul has dissolved already in the ocean of bliss.

But however wise the Mage may be, he is still a body on this earth, and he has not yet surrendered everything. There remain things he cares about, causes in which he passionately believes. And however burnt out the ego may be, there is still a flickering spark. He has the ability and the insight to not just guide those who come behind him, but to shape and even control certain outcomes. How he uses his power and how ready he is to truly shed the things of this world and step willingly into death will be the mark of his final successful arc.

Stakes: Leaving Behind Good World for Those to FollowAs with all good stories, life has a tendency to come full circle. Grandparents often become increasingly focused on the “legacy” they will leave to their beloved descendants. Physically, they sometimes even return to the very same hearth at which they themselves leaned on their own grandparents’ knees, hearing stories of adventures long past.

It is no wonder we most prominently find the Mage in his Flat-Arc form of Mentor. The deeper we get into the life arcs, the more frequently we see previous archetypes showing up in some version of their own stories. And so the Mage Arc inevitably runs concurrently with the younger arcs, particularly those of Hero and King. The Mage is the wise voice in their ear, initiating them and guiding them to see what they have not yet the maturity or the experience to see for themselves.

The Mage cares deeply about whether these younger characters will fulfill their arcs. Will they be able to face the same challenges he did? Will they overcome? How will they be able to resist the temptations of sloth and power present in their counter-archetypes if the Mage does not take care to protect them from themselves?

The Mage’s challenge is very much represented in the anecdote about the boy who waited and waited for his caterpillar to emerge from its cocoon. When the time came and he witnessed how terribly the butterfly struggled to free itself, he “helped” by clipping open the cocoon. He did not realize the butterfly’s struggle out of the tight cocoon was what forced the blood into its beautiful wings. This butterfly emerged with its wings impossibly swollen and limp—and, to the boy’s chagrin, it died.

The Mage, who holds so much power to shape the lives of those he loves, faces the primary challenge of letting them go. He must let them face their own struggles and make their own mistakes. Not only is this crucial to the continuance of healthy life-arc cycles after him, it is also his final challenge in shedding his remaining burdens of this world—and stepping freely into the next.

Antagonist: Understanding the Nature of EvilWithin the Mage’s story, the external conflict may be represented by relatively mundane threats. This is because what now threatens the Kingdom is necessarily a threat “of this world” and rightly pertaining, in fact, to the conflicts of earlier arcs. The Kingdom is under dire threat—perhaps by the Hero’s Dragon, the Queen’s Invaders, or the King’s Cataclysm—but that threat will ultimately be faced by the younger archetypes. The Mage is there to help them understand their duties, but more than that, he is there to combat an even more archetypal antagonist the others cannot yet see.

Campbell puts it:

They fight the demons so that others can hunt the prey and in general fight reality.

This can be seen in the beautiful fantasy stories of The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter, both of which feature Mentor/Mage characters—Gandalf the White and Dumbledore, respectively—who use their power against a much greater evil, while also guiding the younger archetypes as they take on more corporeal antagonists.

However epic the stakes may (or may not) be in the story’s external conflict, the Mage’s story is ultimately one of tying off loose ends and ending the tale. It is about ending one’s life well and dying a good death. Campbell references this finale in a quote from Dante Alighieri’s spiritually metaphoric poem The Inferno:

So it is that when Dante had taken the last step in his spiritual adventure, and came before the ultimate symbolic vision of the Triune God in the Celestial Rose, he had still one more illumination to experience, even beyond the forms of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. “Bernard,” he writes, “made a sign to me, and smiled, that I should look upward; but I was already, of myself, such as he wished; for my sight, becoming pure, was entering more and more, through the radiance of the lofty Light which in Itself is true. Thenceforward my vision was greater than our speech, which yields to such a sight, and the memory yields to such excess.”

The Mage need not literally die in your story (especially if he is represented by a younger character). But he will almost certainly journey on in some respect, even if it is just walking off into the sunset like Bagger Vance (or, in a more symbolic version, Galadriel’s “diminishing into the West” after resisting the final temptation of the Ring’s power).

If he does die, the death may either be a voluntary choice in some sense (such as Obi-Wan Kenobi’s sacrificing himself to Darth Vader in A New Hope or Dumbledore’s plot with Snape in The Half-Blood Prince) or at least a death to which he goes without regret or reluctance (as does Yoda in Return of the Jedi and Garth and Hub McCann in Secondhand Lions). He represents someone “who has fought the good fight and finished his race.”

For easy reference and comparison, here are some scannable summations of the arc’s key points:

Mage’s Story: A Mission.

Mage Arc: Sage to Saint (Liminal World to Yonder World)

Mage’s Symbolic Setting: Cosmos

Mage’s Lie vs. Truth: Attachment vs. Transcendence

“My love must protect others from the difficult journey of life.” versus “True love is transcendent and allows life to unfold.”

Spiral Dynamics by Don Edward Beck and Christopher C. Cowan (affiliate link)

Mage’s Initial Motto: “I, the knowing.”

(This is via Spiral Dynamics’ “Yellow” Meme. If you’re not familiar with Spiral Dynamics, this probably won’t mean anything, but I was fascinated to realize that the six positive archetypal arcs line up perfectly with the “memes” of human development as found in the theory of Spiral Dynamics.)

Mage’s Archetypal Antagonist: Evil

Mage ’ s Relationship to Own Negative Shadow Archetypes:

Either Miser finally opens himself up through his Wisdom to gain Transcendence.

Or Sorcerer learns to surrender his worldly wisdom in exchange for true Transcendence.

The Beats of the Mage Character ArcFollowing are the structural beats of the Mage Arc. Even more than ever for this arc, I am using allegorical language (in keeping with the tradition of the Hero’s Journey). However, it is important to remember the language is merely symbolic. None of the archetypes or settings need to be interpreted literally.

This is merely a general structure that can be used to recognize and strengthen Mage Arcs in any type of story. Although I have interpreted the Mage Arc through the beats of classic story structure, it doesn’t necessarily have to line up this perfectly. A story can be a Mage Arc without presenting all of these beats in exactly this order.

1st ACT: Liminal WorldBeginning: Powerful But Limited

The Mage is an enlightened person—-someone who has understood and accepted the vast and paradoxical partnership of Life and Death. He walks the Liminal World—an existence that is neither Life nor Death but between them. He has no particular home, but roves the land, moving from problem spot to problem spot, helping resolve magical hang-ups or simply solve disputes via his otherworldly wisdom.

He is greatly revered and loved, seen by some as an avuncular friend and by others as a fearsome mystical force. He loves others, but really he loves all—living in a calm neutrality that sees the greater purposes at work in Life’s systems.

He is a friend of Death—but not of Evil, which he has learned to distinguish as not Death itself but the death urge or the addiction to power (being the power over Life and Death). As such, he is careful of his own power, recognizing himself not as a master but as a servant. In overcoming his fear of Death, he has also largely transcended his ego.

In The Legend of Bagger Vance, the mysterious caddy and golf expert shows up, seemingly out of nowhere, seemingly in need of a job—from the one person who most needs his help.

Inciting Event: Revelation/Rise of Evil