K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 21

January 3, 2022

Top 10 Writing Posts of 2021

It is hard to believe we have just bid goodbye to 2021. For me, as for most of you I’m sure, it was a crazy year—crazier than 2020 in some respects.

It is hard to believe we have just bid goodbye to 2021. For me, as for most of you I’m sure, it was a crazy year—crazier than 2020 in some respects.

On a personal level, it was a year that seemed to bring one crisis after another, culminating with a big move in late summer. On a writing level, it was year I started by making the huge commitment to not write–specifically, to take a year-long sabbatical from writing fiction. I’ll be sharing more about this in next week’s post, including why I did it and what I learned from it.

Most of my focus this year was on the huge series I did here on the blog about Archetypal Character Arcs. It was a passion project, and I loved every minute of researching, writing, editing, and sharing it. I am currently at work on a book version, which I hope to publish next year. Other fun stuff that happened this year included:

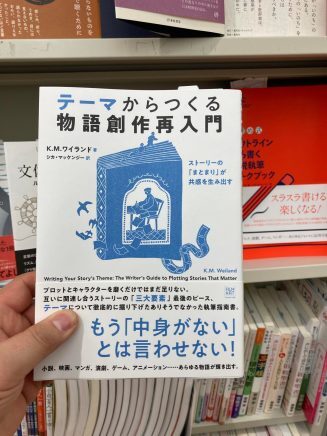

Production of a full-cast audio dramatization of my gaslamp fantasy novel Wayfarer.8th mention of Helping Writers Become Authors in Writer’s Digest’s 101 Best Websites for Writers.

(Thanks to Satoru Omura for the photo!)

For me, next year looks to be another year of big transitions. I hope to start writing fiction again but still haven’t quite decided what to start working on next. In short, I see more adventures on the horizon. I’ll be very interested to fast-forward twelve months and see what I write in this round-up post next year!

For now, I wish you a wonderful New Year, full of goodness, guidance, and protection!

And now, just in case you missed them or want to review, here are my top 10 writing posts from 2021, according to your page views.

My Top 10 Posts of 2021This year’s list is a little different, since it reflects the fact that the vast majority of my posts this year were part of a mammoth series on archetypal character arcs. Nine out of ten of the posts, below, are from that series (only #7 is not). If you’re interested in any of the archetypal posts, you may find it more helpful to visit the series’ master page and read the posts in chronological order: How to Write Archetypal Character Arcs.

1. Introduction to the 12 Shadow Archetypes

3. Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 1

4. The Hero Arc

6. An Introduction to Archetypal Stories

7. Story Theory and the Quest for Meaning

8. 7 Writing Lessons Learned in 2020

9. Archetypal Antagonists for Each of the Six Archetypal Character Arcs

10. The King Arc

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What was the most memorable writing event in your 2021? Tell me in the comments!___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Top 10 Writing Posts of 2021 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 27, 2021

My Top Books of 2021

Every year is a new reading adventure. This year, happily, was one of the best fiction-reading years I’ve had in a long time. I followed my heart a bit more than my head in choosing titles and ended up with some new favorites, as well as re-reading an old favorite that makes the list again as an honorable mention.

Every year is a new reading adventure. This year, happily, was one of the best fiction-reading years I’ve had in a long time. I followed my heart a bit more than my head in choosing titles and ended up with some new favorites, as well as re-reading an old favorite that makes the list again as an honorable mention.

As always, my list is divided into fiction and non-fiction, with a special focus on writing books I enjoyed. I hope you’ll have fun with the list and perhaps pick up a few new favorites of your own!

Total books read: 48

Fiction to non-fiction ratio: 23:25

Top 5 genres: Romance (with 16 books), Personal Growth (with 10), Western (with 10), Fantasy (with 7), and History (with 4).

Number of books per rating: 5 stars (5), 4 stars (31), 3 stars (11), 2 stars (1), 1 star (0).

Writing Books1. Rereading by Patricia Meyer Spacks (read 5-7-21)

I may have to go really meta and re-read this book someday—it’s that good and thought-provoking. In what is really a literary memoir of sorts, Spacks reflects back on the 70+ years of her reading life with thoughtfulness, whimsy, and delightful jaunts into some of my own favorite classics. She inspired me to do a little rereading of my own this year.

2. Wild Mind by Natalie Goldberg (read 7-11-21)

Lots of inspiration in beautiful, bite-sized chapters. An insightful and honest look at the down and dirty of the daily writing life and all its many paradoxical challenges.

3. Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg (read 12-23-21)

Classic that it is, I didn’t like this one quite as much as Goldberg’s second book Wild Mind (above), perhaps because I read the other first. Still, Writing Down the Bones offers up its fair share of authorial soul-bearing and pithy snippets of advice for the loosing of the creative spirit.

4. The Artisan Soul by Erwin Raphael McManus (read 4-2-21)

Think of this as kind of a “lite” version of Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. A quick, inspiring read from a faith-based perspective.

Fiction1. A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin (read 4-10-21)

Beyond wonderful. Where has this book been all my life? Such wonderful and effortless worldbuilding. Gorgeous prose. And the nuanced and symbolic depth of the narrative is fantasy as its best.

2. Piranesi by Susannah Clarke (read 10-29-21)

In this much-anticipated outing, Clarke does not disappoint. This is an extremely unique book, not quite like anything else I have ever read, and yet it is admirably solid, beautifully written, and poignantly thematic. Helmed by an eminently likable narrator, it is a book that is deeply memorable and full of food for thought.

3. Eyes of Silver, Eyes of Gold by Ellen O’Connell (read 11-6-21)

Hit all the buttons for both romance and western. The characters felt effortlessly real and dimensional, the plot always forward-moving without being contrived, and the Colorado setting drawn with a deft and familiar touch.

4. The Return of the King by J.R.R. Tolkien (read 2-4-21)

Predictably, this trilogy was an incredibly special experience. Such a powerful, archetypal, truthful story, told with such elegance and empathy. Truly a masterpiece in its complexity. It is easy to understand why it has many imitators but few if any equals.

5. The Midnight Library by Matt Haig (read 4-25-21)

It’s a Wonderful Life meets Groundhog Day. This is one of those books that does what books are supposed to do—pull you in again and again with the need to know “what’s gonna happen?” I started this book after abruptly quitting on a previous one that triggered my anxiety out of the blue. I almost quit this one too after realizing it was about yet another depressed millennial. But it grabbed me, and even if it’s a little on the nose here and there, it offered a pitch-perfect plot and character arc. It spoke encouraging truths to me, and I loved it.

Honorable Mention: The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern (re-read 5-14-21)

This is an honorable mention only because this is the second time I read it (inspired by Patricia Meyer Spacks’s Rereading). I always say there’s no such thing as a perfect novel, but this one comes awfully close. If anything, I enjoyed it more on this second read. It is possibly the most visually evocative book I’ve ever read. Lush, gorgeous, colorful prose brings to life the titular circus as a phenomenally creative and unique story setting. So often I’m disappointed when stories claim “unique and magical” settings that awe their characters, when really, as a reader, they’re places I’ve already seen a hundred times. No so here. Morgenstern has created a spectacle of wonder and imagination that leaps right off the page. The mystery of the plot and the charming characters end up taking a bit of a backseat to the overall splendor of the descriptive prose, but they provide more than enough steam to power the story forward.

General Non-Fiction1. Romancing the Shadow by Connie Zweig and Steve Wolf (read 7-5-21)

A well-rounded look at many different aspects of shadow work (relationships, work, etc.), bolstered by many examples from the authors’ personal practices.

2. The Road Less Traveled by M. Scott Peck (read 12-2-21)

Rightfully a classic. Moving, eye-opening, challenging, and inspiring. Full of lots of seminal ideas about self-growth that are simultaneously demanding and benevolent.

3. Egypt: A Short History by Robert L. Tignor (read 2-15-21)

A brisk, articulate, and engrossing overview of the mammoth subject of Egyptian history.

4. The Wives of Henry VIII by Antonia Fraser (read 11-16-21)

Excellent, in-depth, entertaining exploration of a perennial topic. Fraser puts the focus not on Henry but on the women who made him (in)famous.

My BooksAnd if all these goodies aren’t enough to fill your To Be Read pile this year, here’s a few more!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What were your top books of 2021? How many books did you read? Tell me in the comments!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What were your top books of 2021? How many books did you read? Tell me in the comments!The post My Top Books of 2021 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 20, 2021

Merry Christmas, Wordplayers!

Dear Wordplayers!

As we close out another momentous year, I am happy to wish you a merry Christmas and happy holidays!

For me, this time of the year is always one of reflection and gratitude. It has been quite a year—on all fronts. For me, personally, it was another year of significant changes in my personal life, in which I walked a road of challenges, but also, ultimately, of blessing. It was a different year, a year in which, for the first time in my life, I consciously took a break from fiction writing. It was a year of transition and, I hope, transformation. From what I have heard from all of you through these past twelve months, I hardly think I was alone in this.

As I close out this particular year, I am struck even more than usual by my tremendous gratitude for all of you. In a time of such uncertainty for all of us on so many levels, the significance of the perseverance, love, kindness, generosity, discipline, humor, and goodness that you all show every day, in ways large and small, is not unnoticed.

Thank you for the time you took this year in stopping by this site to browse, to chat, to wave, to discuss.

Thank you for your passion for storytelling, for learning, for growing. You help me grow, you teach me every day, and you share your passion with me as from one torch to another.

I love you all!

Merry Christmas and Happy 2022!

The post Merry Christmas, Wordplayers! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 13, 2021

The Two Halves of the Climactic Moment

The Climactic Moment is the story in microcosm.

The Climactic Moment is the story in microcosm.

The Climactic Moment is where the protagonist’s final relationship to the plot goal is determined by definitive success or failure, as is the character’s relationship to the thematic Lie and Truth. Although the events of the Climactic Moment might not be the “biggest” of the story, they will always be the most important, in that they decide the story. The Climactic Moment not only brings the story’s conflict to a close, but also determines whether or not the preceding structural elements satisfactorily come together to create a cohesive and resonant whole.

In our series about the two-sided structural beats, the Climactic Moment marks the final one. As we’ve seen in the posts over the course of the past month, this two-sidedness is always about providing a stark division between what comes before and what comes after. For the Climactic Moment, what comes before is the entire story; what comes after is “what will be” in this new paradigm the protagonist has now created.

Specifically unto itself, the Climactic Moment requires the pacing of the story and the climactic sequence to offer two very specific halves of its own, which we will call Sacrifice and Victory/Failure.

But first, a final look at the all of the two-sided beats we’ve discussed in this series:

Inciting EventFirst Plot PointMidpoint (or Second Plot Point)Third Plot PointClimactic MomentWhat Is the Climactic Moment?Ideal structural timing sees the Third Act begin (via the turning point of the Third Plot Point) at the 75% mark. Halfway through this act, at the 88% mark, we then encounter the turning point into the Climax proper. The Climax is a sequence of scenes comprising roughly the final 10-12% of the story, in which the protagonist directly confronts the antagonistic force to finally determine whether or not the plot goal will be fruitfully achieved.

The reason the Climax is given fully half (if not more) of the Third Act is due to this sequence’s obvious importance within the story. This is what everything has been leading up to or foreshadowing throughout the entire story so far.

However, even the Climax itself must rise to a high point and come to a climax of its own. That climax-within-a-Climax is the Climactic Moment. The Climactic Moment is the definitive end of the plot conflict (if not yet necessarily the story itself, which may continue for a few scenes more to tie off loose ends in a Resolution).

The Climactic Moment is the moment in which either the protagonist or the antagonist claims a victory (or perhaps the plot goal is definitively removed from both of their reaches). This is the moment when the bad guy dies or the romantic leads get engaged or the protagonist gets her promotion—or gets her promotion and turns it down because it no longer aligns with her new values.

As I’ve discussed elsewhere in noting the important links between certain structural beats, the Inciting Event in the beginning can be seen to ask a question: will the protagonist triumph in the external conflict? The Climactic Moment, then, is the definitive answer to that question: yes or no.

In many ways, the appropriateness of your Climactic Moment will determine whether or not the entire story works. If the Climactic Moment is a faithful emergent of the Inciting Event’s question—and every subsequent structural beat’s exploration of that question—then the story will hold together to create a big picture.

If, however, the Climactic Moment is not intrinsically related to and emergent from all the previous structural beats, it will prove that the story as a whole does not work—that, in fact, the Climactic Moment is providing an answer to a question that is different from the one posed in the story’s beginning.

One of the easiest ways for this to happen is when the author confuses subplots. For example, if the Inciting Event presents a romantic story with the question of “will they or won’t they fall in love?” then the Climactic Moment must answer that question. If instead the Climactic Moment focuses on a suspense subplot, in which it provides the answer “the bad guy is defeated,” then the story may at best feel fragmented. And, of course, this holds true in reverse as well. If the story begins as a suspense story but puts its main structural focus on the romance in the end (e.g., the bad guy is defeated by the Third Plot Point or some such, leaving the relationship issues to be spotlighted in the Climax), then the Climactic Moment will flounder.

Recognizing the Arc Created by the Two Halves of the Climactic MomentLike any good structural beat, or scene, the Climactic Moment presents a transition. The protagonist may have fully aligned with the thematic Truth just prior to entering the final fray, the outcome of the fray itself should never be taken for granted. Even in genre stories in which readers expect and desire a certain outcome (e.g., the good guys win, the lovers end happily ever after, etc.), the story should not treat this outcome as a given.

This is best accomplished by observing the arc of the Climactic Moment, as revealed by its two halves: Sacrifice and Victory/Failure.

In this modern age of movie spectacle, we often think of the Climax as needing to be the “biggest” scene. Although this is often a good course, it is not inherently necessary, especially as witnessed in quieter relational stories. Even if a romance closes with the comparatively “big” action of one of the leads racing through an airport (or whatever the equivalent in the 21st Century), the Climactic Moment may in fact be a relatively quiet moment of confession and vulnerability—consummated by a symbolic kiss.

It is not always important for your Climax to be the loudest, biggest, flashiest thing in the story. The Climactic Moment’s only true deciding factors are that a) it decides the conflict and b) it provides readers a psychic catharsis after the character’s previous physical and emotional travails.

This is why the Climactic Moment cannot be just a “one and done” beat. There must be an emotional arc. That arc is provided by the protagonist’s willingness to “Sacrifice” and the resultant “Victory” or “Failure” (depending on the character’s relationship to the thematic premise).

SacrificeAs we’ve already seen, the Third Plot Point’s Low Moment created the final crucible for the protagonist’s inner conflict. Whether or not the character chose to fully release the Lie and align with the Truth was, in many ways, an even more important climax than the Climax itself—if only because that choice was the major factor in determining the actual outcome of the external conflict.

If the protagonist did indeed choose to release the Lie and align with the Truth, this decision will have been hard-fought. It was not an easy choice for the very reason that it demanded a sacrifice. The character gave up both the Lie itself and any remaining “protection” provided by its paradigm. The eventual and inevitable progression is that the protagonist’s decision after the Third Plot Point additionally represented total commitment to some great sacrifice that will come due in the final beat of the external conflict.

In stories with life and death stakes, this sacrifice could be the character’s very life. Simply by choosing to enter into the final fray, the character recognizes he is risking his life.In stories with professional stakes, such as legal thrillers, the protagonist may risk losing credibility or even being disbarred in order to align with her own integrity and finish out the trial.In stories with relational stakes, at least one of the leads will confront fears about commitment and union and be willing to make personal sacrifices in order to unite with the other person in a meaningful relationship.In short, the Climax is where the story’s stakes finally demand payoff. Even if the protagonist has already suffered greater losses than what he is facing now, this sacrifice is the one that has been looming all story long. (And, indeed, part of the reason the character is now able to make this sacrifice may be because of the losses he has already lived through.)

Of course, it may eventuate that the character does not, in fact, have to surrender and suffer to the degree she has prepared herself to do. What is most important in this beat is that she is aware of the stakes and is willing to face them without stinting. Only this will allow the external conflict to finally be resolved.

Victory/FailureThe protagonist enters the Climax resolved. He is willing to sacrifice to the last measure (as defined by the story’s context). And he may indeed have to. He may give his life, his career, his health, his relationships, or any other number of difficult surrenders.

He may do this to achieve an ultimate spiritual and moral victory—and indeed perhaps a great physical victory as well, if it turns out the things he’s giving up weren’t really serving him (as in, for example, the case of giving up a toxic or broken relationship).

But it may also be that simply in proving his pureheartedness via his willingness to sacrifice, he will find the ability to achieve his victory without giving up much at all. This usually only happens in stories with comparatively low stakes. If the stakes are life and death, as in action stories, most audiences will not be satisfied with anything less than a true sacrifice of some kind.

However, victory is never assured—particularly if the character chose wrongly between Lie and Truth at the Third Plot Point. She may enter the Climactic Moment willing to sacrifice something (perhaps the right thing, or perhaps the wrong thing). She may lose both what she was willing to risk and the ultimate plot goal. Or she may lose only one, but then discover that the one is no good without the other.

Regardless, this is where we find the true Climactic Moment, the true end to the story. Not only do we see the external conflict resolved and the plot question answered, we also see the results of the characters’ choices. We see whether the characters are made happy or sad, whether they are better off for all their trials or worse. What happens in the Climactic Moment is the story’s final statement about human reality, whether it is explicit or more likely simply implicit in the characters’ comparative state at the end of the story.

***

This concludes our little series about the two halves of each of the major structural beats. I hope this has helped you see the inherent emotional arc within each beat and therefore what each beat is intended to achieve within the overall structure of the story!

Previous Posts in This Series:

The Two Halves of the Inciting EventThe Two Halves of the First Plot PointThe MidpointThe Third Plot PointWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify both the Sacrifice and the Victory/Failure in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Two Halves of the Climactic Moment appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 8, 2021

Announcing the Full-Cast Audio Production of Wayfarer!

Today, I get to do something I’ve never done before! I get to announce that my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer is now available not just as an audio book but as a full-cast immersive audio production complete with original music and sound effects!

I cannot begin to tell you how excited I am about this one. Unabridged and produced by Sargent Family Productions, it’s almost like seeing it as a movie!  I’m not much of an audiobook listener myself and normally I can barely stand to read my own stuff aloud, much less listen to someone else read it. But this experience is such an utter delight. For me, it’s almost like listening to a story written by someone else!

I’m not much of an audiobook listener myself and normally I can barely stand to read my own stuff aloud, much less listen to someone else read it. But this experience is such an utter delight. For me, it’s almost like listening to a story written by someone else!

So if you’re into gaslamp fantasy*, or if you’ve already read and enjoyed Wayfarer, or if you want to experience a full-on audio dramatization, or if you just prefer the audio experience in general, I hope you’ll check it out! It is available for streaming or download via the Awesound platform, which was specifically chosen for the rich, immersive experience it provides to listeners. For best results, listen with quality headphones or speakers.

(*What’s gaslamp fantasy, you ask? It’s a subgenre of fantasy and a spinoff of steampunk, in which the setting is historical—1820 England in this case—but with more of a focus on magic or mad science rather than tech.)

About WayfarerIn this heroic gaslamp fantasy, superhuman abilities bring an adventurous new dimension to 1820 London, where an outlaw speedster and a master of illusion do battle to decide who will own the city.

Think being a superhero is hard? Try being the first one.

Will’s life is a proper muddle—and all because he was “accidentally” inflicted with the ability to run faster and leap higher than any human ever. One minute he’s a blacksmith’s apprentice trying to save his master from debtor’s prison. The next he’s accused of murder and hunted as a black-hearted highwayman.

A vengeful politician with dark secrets and powers even more magical than Will’s has duped all of London into blaming Will for the chilling imprisonments of the city’s poor. The harder Will tries to use his abilities to fight crime, the deeper he is entangled in a dark underworld belonging to some of Georgian England’s most colorful characters.

Only Will stands a chance of stopping this powerful madman bent on “reforming” London by any means necessary. Unfortunately, Will is beginning to realize becoming a legend might mean sacrificing everything that matters.

Read Listen to this new adrenaline-fueled historical superhero adventure today!

You can listen to a short trailer below and order here.

https://www.generationsthestory.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/WF_Trailer_A_Smaller.mp3The post Announcing the Full-Cast Audio Production of Wayfarer! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 6, 2021

The Two Halves of the Third Plot Point

Like all the major structural turning points, the Third Plot Point is made up of two halves—which work together to create a scene arc (even though, technically, the entire arc of the beat might be told over the course of a scene sequence made up of many scenes). The halves that create this arc are important because only together can they create the realistic resonance of cause and effect. If the Third Plot Point is where the character sinks into a reverie on mortality (or at least the potential failure of his plot goal), there must first be a “high place” from which he falls. The higher this place, the more striking the plight of the Third Plot Point will be.

Like all the major structural turning points, the Third Plot Point is made up of two halves—which work together to create a scene arc (even though, technically, the entire arc of the beat might be told over the course of a scene sequence made up of many scenes). The halves that create this arc are important because only together can they create the realistic resonance of cause and effect. If the Third Plot Point is where the character sinks into a reverie on mortality (or at least the potential failure of his plot goal), there must first be a “high place” from which he falls. The higher this place, the more striking the plight of the Third Plot Point will be.

The Third Plot Point also signifies the “descent” into the following Climax. Regardless the character’s travails up to this point, everything is about to get much worse, at least in the sense that the conflict is finally coming to an irrevocable head. At the Third Plot Point, the protagonist descends into the abyss of the Third Act. This symbolic underworld could be as “heavy” as imprisonment and torture by the enemy or as “light” as nerves before a school dance recital. Whether or not the protagonist makes it out depends largely on how she copes with the two halves of the Third Plot Point.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Once again, here’s a big-picture look at the beats we’re exploring:

Inciting EventFirst Plot PointMidpoint (or Second Plot Point)Third Plot PointClimactic MomentWhat Is the Third Plot Point?In many systems dealing with the Three-Act Structure, the Third Plot Point may also be called the Second Plot Point (in which case, the Midpoint is not considered a “major” plot point in its own right). Really, though, it’s just semantics; in both cases what is being referenced is the threshold between the Second and Third Acts, which takes place roughly 75% of the way into the story.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

This beat is a crucial transition point and should not be confused with the beginning of the Climax which takes place later on, halfway through the Third Act (at approximately the 88% mark). You may notice that in many stories—especially action-oriented movies—the Third Plot Point may be either skipped or its functional death/rebirth role is moved up to the preceding Second Pinch Point (taking place at approximately the 67% mark). This is usually done to create more story space for big set-piece climactic action scenes. But from a structural—and particularly a character-arc—perspective, it risks weakening one of the most important thematic beats in the entire story.

As we discussed last week, the Midpoint and its Moment of Truth is when the protagonist will accept the thematic Truth as true and begin trying to adopt it as a guide for his actions within the plot. However, the protagonist did not yet reject the Lie. For the remainder of the Second Half of the Second Act, the character will try to straddle both thematic paradigms or mindsets. And this is ultimately what brings him to the disaster of the Third Plot Point—and his final decision of whether he will fully “die” to the old Lie and be “reborn” in the new Truth. Depending on the nature of the story, this is a battle that may be waged down to the very depths of the character’s soul. It may even, literally, be a life and death decision.

The Third Plot Point will prove that the consequences for retaining the Lie are costly. But the beat itself will also force the protagonist to confront the reality that rejecting the Lie will also be costly. This is important. The temptation to keep the Lie instead of the Truth should be formidable. (Otherwise, why did it take the character 75% of the book to figure out that the Truth will clearly serve her much better?)

The Third Plot Point is also an important beat simply within the external conflict, since it sets up the Climax to come. In essence, the defeat at the Third Plot Point creates the final big obstacle between the protagonist and his plot goal. It is what creates the ultimate conflict between the protagonist and the antagonistic force in the Climax. Part of the “dark night of the soul” in the Third Plot Point is the question to the protagonist of whether or not he really wants the plot goal enough to tackle this final and most fearsome obstacle.

The answer, to one degree or another, will always be yes, since otherwise the story ends right there. This is true even if the character fails to choose properly between the Lie and the Truth. If she fails to utterly reject the Lie and be “reborn” into the Truth, she will proceed into the final conflict but with the wrong motives and/or tactics. She will either fail in her plot goal for lack of the Truth, or she will prevail but discover it is a hollow victory (or at least the audience will witness the harm it engenders for the rest of the story world).

>>Click here to read about the Negative Change Character Arc.

Recognizing the Arc Created by the Two Halves of the Third Plot PointThe Plot Revelation at the Midpoint gave the protagonist the ability to see the conflict more clearly and “take it to” the antagonist in a more proactive way. Even if the stakes are higher than ever in the Second Half, the protagonist at least now has a plan for reaching the plot goal. This section of the story will last from the Midpoint at the 50% mark all the way to the Third Plot Point at the 75% mark.

And then, all within the span of the two halves of the Third Plot Point, this course of action reaches what seems a dramatic victory—only to then plummet the protagonist into the worst fix yet (existentially if not physically).

The two halves of the Third Plot Point are the False Victory and the Low Moment.

The False VictoryThe False Victory is somewhat misnamed in that it very likely will be a true victory of some sort. Perhaps the protagonist attacks the enemy stronghold and gets what he wants, only to discover it was a trap or that his own army’s base was destroyed in his absence. It is a Pyrrhic victory.

For example, in Star Wars: A New Hope, Luke and his friends escape the Death Star—but with a tracking beacon aboard their ship that will lead the bad guys to the Alliance’s base.

In Jane Eyre, Jane is about to be married to her one true love—only to have the ceremony interrupted with news that he is already married.

What is important is that the protagonist either gains or seems to gain what she is trying for. The problem is that she is trying to push through to the end from a place that lacks total integrity. This lack of integrity doesn’t have to be strictly moral. It could simply be the result of not fully understanding what she’s doing, why, and what the ramifications will be.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

From a thematic perspective, the victory turns out to be incomplete simply because the character is trying to “push it through” while being compromised in some way because she hasn’t fully rejected the Lie—and therefore can’t fully utilize the necessary Truth. It’s like trying to cheat to win a game of cards instead of doing it honestly through true skill.

Even if the False Victory is just a single moment in which the protagonist thinks he has triumphed, this emotional beat is important for setting up the fall into the subsequent Low Moment.

The Low MomentWhen we contemplate the Third Plot Point, the Low Moment is usually the part that comes to mind. Within the overall psychological arc of the story, the Third Plot Point always represents death. Intrinsically, this death is that of the Lie—and thus of the protagonist’s Lie-based paradigm and ability to identify with it.

However, externally within the plot, this death can be portrayed in many ways. This is very often where an important supporting character literally dies (such as Obi-Wan Kenobi in A New Hope).

But the death can also be that of an occupation or relationship (as in Jane Eyre).

It can also be represented simply via the threat of death to the protagonist herself. Or it might be glimpsed in a larger way via a world at war or even just careful symbolism in the background (e.g., ravens or black umbrellas).

It’s valuable to think of this beat as representing “death” both because of the thematic significance and also because “death” emphasizes the severity of this moment within the story. Even if what happens to the character here is not the “worst thing that could happen” (i.e., actual death), it is the worst thing that can happen in the context of the story up to this point.

It is a common misconception and source of confusion that the Third Plot Point must be the worst thing that happens in the entire story. What happens in the Climax may indeed be much worse: the protagonist may indeed die at that point. But whatever happens in the Climax will happen within the context of the protagonist’s new Truth-based perspective. So, for example, even if the character must sacrifice himself in the end, he will do so in the belief that his death is important and meaningful. In a Positive-Change (or Flat) Arc, he may die for the Truth. Symbolically, his soul will be at peace even if his body must be destroyed.

Of course, in many stories, this is portrayed much less dramatically. Actual death may not be part of the equation at all. Back to our dance-recital example, a young student may grapple at the Third Plot Point with fear of humiliation—aka ego death. If she rises from this struggle and carries on into the Climax with her dance routine, she will be thematically and existentially victorious whether or not she “wins” or “dies.”

But what if the character fails in his thematic grappling and refuses to “die” to the Lie? This failure at the Third Plot Point may well prove fatal in the final confrontation with the antagonistic force in the Climactic Moment. Or it may be that the character pushes through to his plot goal, only to find it an empty victory because he “gained the world but lost his soul.”

The external conflict will not be fully decided until the Climactic Moment. But the internal conflict will be largely resolved during the Third Plot Point and its subsequent scenes. The protagonist may not fully make up her mind (or realize she’s made up her mind) until the Climactic Moment. But whatever happens at the Third Plot Point determines whether or not the character “wins” her character arc and its internal thematic battle. The outcome of this beat is what provides context for the ultimate success or failure in reaching the plot goal in the following the Climax.

When both halves are utilized, the Third Plot Point has the potential to be one of the most moving and thought-provoking moments in any story. The key is creating the necessary emotional (and rational) shift from the high of the False Victory down into the depths of the Low Moment—and then, hopefully, back up again into a victory of true personal integrity.

***

Stay tuned: Next week, we’ll conclude our series by taking a look at the two halves of the Climax: Sacrifice and Victory/Failure.

Previous Posts in This Series:

The Two Halves of the Inciting EventThe Two Halves of the First Plot PointThe MidpointWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify both the False Victory and the Low Moment in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Two Halves of the Third Plot Point appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 29, 2021

The Two Halves of the Midpoint

The Midpoint is unique among the major structural turning points. Not only is it made up of its own two individual halves—working together to create a scene arc—but the Midpoint also marks the dividing line between the two halves of the entire story arc.

The Midpoint is unique among the major structural turning points. Not only is it made up of its own two individual halves—working together to create a scene arc—but the Midpoint also marks the dividing line between the two halves of the entire story arc.

As we explored last year in our series on chiastic structure (or how the structural beats in the two halves of the story mirror one another—e.g., the link between Inciting Event and Climactic Moment), the Midpoint is also unique in that it stands alone at the “top of the circle” with no partner or mirroring beat. Rather, the Midpoint notably offers what James Scott Bell so brilliantly calls “the Mirror Moment.” This is a moment within the story, usually inherent within the thematically all-important Moment of Truth, in which the characters are given the opportunity to see truths about themselves “as if in a mirror.”

What the Midpoint (or Second Plot Point) does have in common with all the other major structural beats is that it, too, is comprised of two halves. This is, of course, because the Midpoint is a scene (or sequence of scenes) in its own right, offering a complete scene structure and emotional arc.

In the previous two posts, we started talking about how each of the major structural turning points is made up of two intrinsic parts which together serve to “reverse the value” of the scene by moving the character through some progression of Goal to Disaster. In all the beats, both halves are important for properly turning the plot.

The beats we’re exploring are:

Inciting EventFirst Plot PointMidpoint (or Second Plot Point)Third Plot PointClimactic MomentWhat Is the Midpoint?

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

As the centerpiece of the story, the Midpoint in many ways encapsulates the entire point of the story. Plot, character arc, and theme all coincide here (more obviously even than usual) to provide the protagonist with at least the opportunity to see the world in a different and potentially more functional way than previously. Depending on what the character realizes and accepts at the Midpoint, he should be able to use this new knowledge to move onward more effectively toward the plot goal.

This is why the Midpoint structurally marks the transition from the “reaction” of the First Half of the Second Act (in which the character lacked sufficient understanding to combat the obstacles of the antagonistic force) to the “action” of the Second Half of the Second Act (in which the character uses the Midpoint’s revelations to aid in a more proactive approach to avoiding/defeating the antagonistic force and gaining the plot goal).

Although the story goes on and the conflict will not be definitively decided until the Climactic Moment, the Midpoint is really the moment that determines the protagonist’s fate. Whether or not the character “gets it” in the Midpoint will determine whether or not the resources for a climactic victory will be available come the end.

Recognizing the Arc Created by the Two Halves of the MidpointIf your story is a mountain, then the Midpoint is the peak. When your protagonist reaches the Midpoint, she will stand with one foot on either side of the peak. In other words, the first half of the Midpoint takes place in the first half of the story and the second half of the Midpoint in the second half of the story. Like the First Plot Point, it can be viewed as a doorway through which the character must step.

As such, since we know the first half of the story features the protagonist in a “reactive” mode and the second half features an “active” mode, we can know these two halves must also define the Midpoint itself.

The Midpoint is usually a major set-piece scene in some way. In an action story, it will probably be a battle or some such. In a more relational story, it may be a dramatic confrontation. The protagonist will enter this set-piece scene lacking some crucial bit of information, which currently renders him “reactive.” He is trying in some way to score a major victory here, but because he lacks all the necessary information, even his greatest display of initiative ultimately remains reactive.

But the Midpoint itself will change all that by offering crucial new insights and information. Even though the Midpoint itself may be a categorical defeat for the protagonist, the information gained here means she can now sally forth into the second half of the story much better equipped to score victories in the future.

Intrinsically, the two halves of the Midpoint represent a coming together of the external and internal conflicts—and how each influences the success or failure of the other. The first half is that of a Plot Revelation (or reversal); the second half is that of the thematic Moment of Truth. In short, the first half offers paradigm-shifting new information, while the second half is about the new internal understandings that arise from this information. The character not only learns something in the outer world, but also discovers new knowledge within himself.

Let’s take a closer look.

The Plot RevelationIn “plot-driven” stories, the Plot Revelation will take center stage at the Midpoint. Sometimes it will even appear that the Plot Revelation is the Moment of Truth. Indeed, this may sometimes be the case, although only in stories that feature little to no character development or arc. It is also true that because the subsequent Moment of Truth is caused by the Plot Revelation, the two are intrinsically linked, sometimes to the point they seem one and the same.

However, from a structural and technical point of view, it is valuable to see their separate cause/effect, push/pull relationship.

Specifically, the Plot Revelation is information the protagonist learns about the external plot. This information may be told through dialogue, but due to the dramatic nature of the Midpoint, it is just as often information that is dramatized (e.g., a wife walks in on her husband having an affair).

Because of the “internal truth” nature of the linked Moment of Truth, the most effective approach is often to communicate the Plot Revelation to the protagonist “in a flash.” It lands in a way that is less about “teaching” the protagonist something new (although it certainly can) and more about “uncovering” the inner Truth that has been slowly consolidating for the protagonist over the course of her character arc so far.

Put another way, even if the events of the Midpoint are utterly unexpected and shocking, they still feel like a sensible progression. (From a craft point of view, foreshadowing in the first half of the story is, of course, the vital ingredient to conveying this feeling to readers.)

Basically, the Plot Revelation’s main job is providing the protagonist with the single most important bit of information about why his attempts to gain the plot goal have so far been less than effective. After all, he’s been trying all this time—why doesn’t he have it by now?

The Plot Revelation shows him what is holding him back. If he’s a scientist, this may be a mistake in his calculations. If he’s trying to make a relationship work, it may be his own (and his love interest’s) intrinsic fears of vulnerability, intimacy, and commitment. If he’s trying to catch the bad guy, the revelation may be about the bad guy’s true identity or motivation. Or if he’s simply trying to survive in a wilderness situation, the revelation may be about why he’s sure to die if he doesn’t change tactics and somehow escape.

The possibilities are vast and varied. Although the new information must be dramatic enough to turn the plot, the revelation itself can be conveyed with relative subtlety. In some movies, the Midpoint is as subtle as a shift of the protagonist’s expression while watching the sunset (although usually this only happens in “character-driven” stories in which the conflict is mainly internal and the emphasis is almost entirely on the Moment of Truth rather than the Plot Revelation).

The other important aspect of the Plot Revelation is a plot reversal. It is not enough for the protagonist to simply learn something new and experience a revelation. If the Midpoint is to properly move the plot, she must act upon it—she must change the story.

The Moment of TruthIf the Plot Revelation is something that essentially happens to or is given to the protagonist, the subsequent Moment of Truth is about the protagonist then taking ownership of that information and using it to manifest a significant change of perspective.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

In contrast to the Plot Revelation, which is about the external conflict, the Moment of Truth is specifically about the inner conflict—and therefore is more representative of progressive change in the character arc and theme.

Up to this point, the protagonist will have been operating from a less and less effective Lie-based mindset, in which he holds to some fundamental and increasingly dysfunctional misinformation about reality. Practically, this Lie is what has ultimately caused him to be less than successful in the outer plot (even though the Lie itself is not the specific information from the Plot Revelation about “how to defeat the antagonist”). His semi-failures up to this point have been teaching him a new and counteractive Truth.

It is the Moment of Truth, spurred by the events and information of the Plot Revelation, that suddenly brings this seed of Truth into full bloom. The character not only learns something important about where she is going wrong in the outer conflict, but she also recognizes, at least implicitly, the limited personal perspective that has ultimately led her to make these external mistakes.

If the character accepts this new perspective (as she will in a Positive-Change Arc), she will be able to move forward into more and more successful interactions with the external world.

However, don’t forget this is only the Midpoint of the story. Plenty of plot and character arc remains to happen. So although the character here realizes the essential Truth of his story, he does not yet realize or find himself capable of completely rejecting his previous misconception or Lie. And so his evolution will continue in the second half of the story, until the Third Act when he finally realizes that the Truth cannot be fully effective unless he is also willing to entirely reject the Lie—in short to die to the Lie and be reborn in the Truth (a painful process that should never be taken for granted even with comparatively “small” perspective shifts).

Together, the Plot Revelation and the Moment of Truth provide the necessary cause and effect to create massive change within the Midpoint. They also work in tandem to beautifully unify plot, character, and theme into a cohesive whole.

If you can make sure the Midpoint of your story features both of its important halves, you can be sure you’re taking full advantage of its deep potential for elevating your entire story.

***

Stay tuned: Next week, we will take a look at the two halves of the Third Plot Point: the False Victory and the Low Moment.

Previous Posts in This Series:

The Two Halves of the Inciting EventThe Two Halves of the First Plot PointWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify both the Plot Revelation and the Moment of Truth in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Two Halves of the Midpoint appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 26, 2021

Black Friday Deals for Writers

This Black Friday weekend, you can use the code OUTLINE to grab my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software at a special holiday discount of 25% its normal price of $40. (And scroll down for a list of deals from all around the online writing community.)

Start Outlining Your Best Book Today

As a reader of my blog, you can access a special 25% discount code for my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software. Just enter the code OUTLINE at checkout. This deal will only be available Black Friday through Cyber Monday. Enjoy!

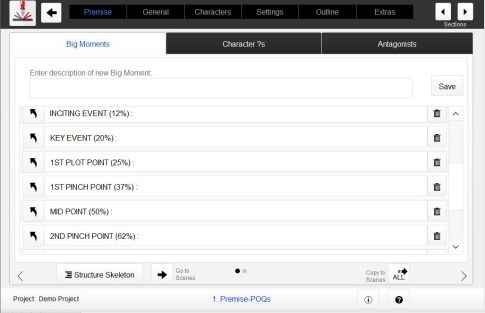

How Can the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software Help You?The Outlining Your Novel Workbook computer program is a brainstorming tool for writers. It is designed to guide you in discovering the brilliant possibilities in your ideas, so you can identify those best suited to creating a solid story that will both entertain and move your readers.

The software provides an easy fill-in-the-blanks format that will guide you through every step of the process. Creating your own outline is as simple as starting on the first screen, using the prompts and lessons to work through your story in the most intuitive way, and clicking through the tabs at the top to access important sections.

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook program makes outlining a fun and empowering process that will help you write your best story.

Features:• Outline – Create a story with a solid Three-Act plot structure and perfect scene structure.

• Premise – Easy fill-in-the-blanks give you a perfect elevator pitch every time.

• General Sketches – Brainstorm the big picture of your scene list, character arcs, and theme.

• Character – Get to know your characters with an extensive character interview, featuring 100+ questions.

• Settings – Keep track of your settings, explore your best options, and answer helpful world-building questions.

• Fun Extras – Import your mind maps and world maps, keep track of your story’s timeline, cast your characters, and create story-specific musical playlists.

Don’t forget to use the code below to get 25% off your order of the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software:

OUTLINEHappy Thanksgiving, everyone!

More Black Friday Deals:I’m participating in a joint promotion for deals on writing programs, courses, and more from around the Web. Following, you can find dozens more Black Friday and/or Cyber Monday deals for writers.

Note: These are not personal recommendations, and I do not have personal experience with all of these products and companies. If you have questions about any of the below offerings, it is best to directly query the particular site for further information.

ProWritingAid: Up to 50% offDates: Nov. 15–30

ProWritingAid gives you clear, easy steps to improve your writing so you can share your stories and ideas with confidence. What sets ProWritingAid apart from other writing software is that it offers world-class grammar and style checking combined with more in-depth reports to help you strengthen your writing. Their unique combination of suggestions, articles, videos, and quizzes makes writing fun and interactive. If you are serious about writing, then this is the grammar and style checker for you.

Fictionary: 40% off with code BLACKFRIDAY21Dates: Nov. 15–30

Fictionary StoryTeller is a creative editing software for fiction writers and editors that makes editing easier by applying universal storytelling structures to each and every scene. Evaluate and revise your manuscript against thirty-eight Fictionary Story Elements to tell a powerful story, that readers will naturally connect with.

The Novel Factory: 30% off with code BLACKFRIDAY2021Dates: Nov. 15–Nov. 30

Novel Factory 3.0 offers dedicated sections to develop and keep track of your characters, a step-by-step novel writing guide, and loads of useful resources for writers, such as plot templates and character questionnaires.

Campfire Technology: 30% off with code BLAZEFRIDAYDates: Nov. 15–Nov. 30

More than 100,000 writers use Campfire to write better stories faster. With Campfire Write’s full suite of organizational tools, you can create character sheets, full timelines, relationship webs, and a manuscript with built-in reference tools that allow you to double-check yourself while you write. When you’re done, publish your project in Campfire Explore where you can show off your work, garner a following, and eventually monetize your writing.

The Writing Cooperative: 20% off with code BLACKFRIDAYDates: Nov. 25–Nov. 30

Are you craving accountability and feedback on your work? Do you want to write but don’t know where to start? Do you want a team that supports and encourages you? Introducing the Writing Cooperative Community Cohort! Our small-group-based, five-week coaching program combines accountability, support, and encouragement to help you write better and achieve your goals.

World Anvil: 50% off with code BLACKFRIDAYDates: Nov. 25–27

Join over 1.5 million writers and worldbuilders, and build the world of your dreams with World Anvil! Develop your setting, plots and characters with flexible worldbuiding templates, and a host of vital tools like interactive maps and family trees. Plan and write your novel—like so many Amazon bestsellers already have—in our integrated novel writing software. Then market your work to the world, building a community of readers and superfans around your work, who can’t wait for your next release! We even give World Anvil members additional publicity, opportunities and challenges!

The Anatomy of Prose and Villains Masterclasses: 30% off with code BLACKFRIDAYDates: Nov. 26–Dec. 2

Do you want to improve your prose, characters or storytelling? Join rebel author, podcaster, and bestselling author Sacha Black for her writing classes.

Instagram for Authors Self-Publishing 101 Course: Save 40%Dates: Nov. 15–30

Use Instagram to help you grow your author community and sell more books!

Women in Publishing Summit: 100% off full conference ticket, no code neededDates: Nov. 1–30

Join the Women in Publishing Summit for our annual conference providing tips, tools, and resources to authors, celebrating the accomplishments of women in the publiishing industry

One Stop for Writers: 40% off with Code BLACKFRIDAY2021Dates: Nov. 15–30

Ready for a game-changer? One Stop for Writers is the creativity partner you’ve dreamed of, containing an arsenal of ground-breaking tools that can help you level up your fiction. Whether you want to build memorable characters, stunning worlds, or fresh, engaging plots, One Stop has resources that demystify storytelling so you can write stronger stories much more easily. And if you need step-by-step guidance, our new Storyteller’s Roadmap is your GPS for planning, writing, and revising your way to a best-selling novel. Expert help without the high costs of story coaching… it’s time to get your book to the finish line. Writing can be easier…and with One Stop, it will be!

Grammar Lion: $40 OffDates: Nov. 24–Nov. 27

Learn the grammar you need to know, whatever kind of writing or editing you do!

Nrdly—Website Platform for Authors: 25% off with code GET25Dates: Nov. 24–30

No more generic websites. With Nrdly you get a site designed by business experts to give you exactly what you need. Save 20% off your first order with Nrdly.

BookBaby: $50 off off Social Ad for Authors with code FACEBOOK50Dates: Nov. 1–30

Save $50 on a custom-built ad campaign that reaches your readers on the world’s most popular place to hang out.

Conquer Writer’s Block Online Course: 50% off with code BLACKFRIDAY11Dates: Nov. 26–30

This course that will help you become a prolific writer. This online course will give you the skills you need to turn up in front of the blank page full of ideas and with a clear plan about which one to focus on. The self-paced course will help you build a personal writing system that works so you can find the success you deserve today.

Publisher Rocket: Get Keywords and Categories Course free with purchaseDates: Nov. 24–30

Publisher Rocket is a book marketing software that helps authors with finding profitable keywords and categories and even helps them build Amazon books ads effectively and efficiently. The course that comes with this deal, which is normally $50, will show you each step of the way and give you inside information on how to best select your keywords and categories.

First Editing: 21% Off with Code: BLACK20Dates: Nov. 25–Dec. 5

FirstEditing’s professional editors manually correct and perfect your every word so you can publish confidently and successfully. FirstEditing is unique because it vets, trains, and certifies expert editors with publishing experience to coach you. Over 50,000 authors since 1994 have entrusted FirstEditing with their manuscripts. After completing your self-edit, be sure you are ready to distribute publicly. Get an expert editor in your genre to personally edit your writing, revise your syntax, and advise you how to structurally strengthen your English presentation.

Note: If you have any questions about any of the offerings, it is best to directly query the particular site for further information.

The post Black Friday Deals for Writers appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 22, 2021

Happy Thanksgiving, Wordplayers!

Happy Thanksgiving, Wordplayers!

I’m taking this week off to focus on the things I’m grateful for in my life. Mostly just for fun, I thought I’d share a random list of some them:

Wordplayers!This site, which keeps me learning and writing and thinking week after week, month after month, year after year.Beautiful, beautiful words—black on white, long and short, rolling in my brain, curling on my tongue.Stories—of courage, truth, hope, pain, love, curiosity, and beauty.Clickety-clacketedy typing keys.Other writers howling into the void, so I may catch the echo and howl back.Patterns and logic and creativity and theory.Those perfect witty comebacks that fall out of other peoples’ character mouths—and just so perfectly suit in real-life conversation after conversation.Shiny book jackets and stately hardcovers and well-lined paperback spines.My illegible inky scrawl in notebook after notebook.Dreams and visions out the corner of my eye all day long.Markus Zuzak and Kristen Heitzmann and Louisa May Alcott and Frances Hodgson Burnett and Charles Dickens and Charles Frazier and Zora Neale Hurston and Brent Weeks and Audrey Niffenegger and C.S. Lewis and Charlotte Brontë and Jane Austen and L.M. Montgomery and Timothy Zahn and Brian Jacques and Ursula Le Guin and Edward Rutherfurd and J.R.R. Tolkien and Anthony Ryan and Susanna Kearsley and Terry Pratchett.Awwww-wooooooo! (that was me howling into the void).Happy thanksgiving, all! I hope you’re celebrating a life full of gratitude—and not least for all those little writerly joys with which we get to fill our moments.

The post Happy Thanksgiving, Wordplayers! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 15, 2021

The Two Halves of the First Plot Point

The First Plot Point is one of the most important turning points within the entire structure of story. As with all of the major structural beats, the idea of a “turning point” offers the inherent concept of two halves: turning away from one thing/state into another thing/state. The First Plot Point is often referred to as a threshold or “Door of No Return,” which offers another type of visual metaphor to represent the native two-sidedness of all the major structural beats.

The First Plot Point is one of the most important turning points within the entire structure of story. As with all of the major structural beats, the idea of a “turning point” offers the inherent concept of two halves: turning away from one thing/state into another thing/state. The First Plot Point is often referred to as a threshold or “Door of No Return,” which offers another type of visual metaphor to represent the native two-sidedness of all the major structural beats.

Last week, with a post about the Two Halves of the Inciting Event, we kicked off a little informal series in which we are breaking down the major structural beats into the halves that create their crucial scene arcs.

The beats we’re exploring are:

Inciting EventFirst Plot PointMidpoint (or Second Plot Point)Third Plot PointClimactic MomentAs the transition between the First Act and the Second Act, the First Plot Point creates a tremendous arc—out of the protagonist’s Normal World and into the symbolic Adventure World of the plot’s main conflict. It is one of the most crucial beats not just for getting a story off to a good start, but for ensuring that the following plot mechanics can operate at full capacity. A weak (or missing) First Plot Point can irreversibly damage the entire story. I would argue weak First Plot Points are one of the main reasons readers put down a book and never finish it.

In writing a story with a strong First Plot Point, it is important not just that it is there at approximately the correct timing (around the 25% mark), but that it includes the two crucial and important halves that will ensure it creates the necessary arc into the Second Act.

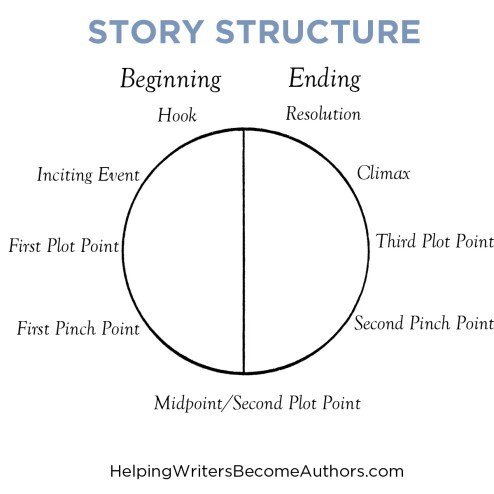

Once again, here is a quick overview of all the major structural beats and their recommended timing:

The First Act (1%–25%)

The Hook – 1%

The Inciting Event – 12%

The First Plot Point – 25%

The Second Act (25%–75%)

The First Pinch Point – 37%

The Midpoint (Second Plot Point) – 50%

The Second Pinch Point – 62%

The Third Plot Point – 75%

The Third Act (75%–100%)

The Climax – 88%

The Resolution – 99%

This series is discussing the intrinsic structural halves of the italicized beats.

What Is the First Plot Point?Although all of the “main” structural beats (those listed above) are necessary for a strong and complete story structure, only three of these beats are classified as “major plot points.” These are the beats that divide the story into fourths (taking placing at the 25%, 50%, and 75% marks). The First and Third Plot Points mark the transition between acts (the Midpoint, or Second Plot Point can be seen to do this too, if you prefer thinking of the model as Four Acts instead of Three).

In short, plot points are a big deal. In some respects, they can be thought to be the entire story in microcosm. This is because the plot points, more than any of the other beats, signify not just a turning point or a “movement” of the plot—but a total paradigm shift or reversal of the protagonist’s current course of action.

We can recognize this in the terminology that often refers to the First Plot Point as the Door of No Return. What happens at this plot point, and indeed all of them, cannot be reversed. Particularly in the case of the First Plot Point, even if the protagonist could return to the Normal World, he could not return to it as it was (or as he was). In short: the First Plot Point has consequences.

Within the customs of the Hero’s Journey, this is the moment when the protagonist leaves behind the Village and embarks into the unknown wilds on a dangerous Quest.

The First Plot Point signifies the end of the First Act’s setup and the beginning of the conflict proper. From here on the protagonist is totally absorbed in seeking a goal—and in struggling against an antagonistic force that is creating conflict by throwing up obstacles to that goal.

Screenplay by Syd Field (affiliate link)

So what are the two halves of this important beat? Customarily (and hopefully not too confusingly), I have always referred to these halves by the names I first learned in Syd Field’s book Screenplay: the Key Event and the First Plot Point.

Over the years, people have often been confused by this distinction, since it quite obviously separates the Key Event from the First Plot Point as a beat of its own. But in harking back to the doorway metaphor, I believe the best way to distill the symbiotic relationship of the two is to view them as existing immediately on either side of the same doorway.

If you visualize your entire First Plot Point as a doorway between the First Act and the Second Act, then you can see your Key Event as the moment when the protagonist steps into the doorway, and the First Plot Point as the moment when the protagonist steps out of the doorway.

This concept will of course be dramatized in a either a single scene or a sequence of scenes. In fact, the Key Event can take place much nearer the Inciting Event (at the 12% mark) than to the First Plot Point proper (at the 25% mark), depending on how your First Act requires you to set up the entry into the Second Act.

Regardless of timing, what is important is that the Key Event and the First Plot Point function as two halves of the same whole, acting together to create an arc that, just like any good arc, reverses the “value” of the scene or sequence (from happy to sad, passive to aggressive, ignorant to curious, etc.).

Now, let’s take a look at each of these two important halves.

The Key EventPut simply, the Key Event is where the protagonist actively engages with the conflict for the first time. It is a choice of some sort.

The previous Inciting Event introduced the protagonist to what will be the main conflict. I like to think of the Inciting Event as the moment when the protagonist “brushes against” the conflict. Up until the Inciting Event, even if the protagonist was aware of a desire for the story goal and/or the problems created by the antagonistic force, the protagonist was not yet asked to face, confront, or perhaps even acknowledge its presence in or impact upon her life.

A good example of this can be seen in romance stories. As mentioned last week, the Inciting Event in a romance is almost always the first (or at least the first “true”) meeting of the love interests. They may have been completely unaware of each other’s existence prior to this moment. But thanks to the Inciting Event, they “brush against” the main story goal and conflict, which will be, of course, their relationship.

But they are not yet “connected.” Either or both can walk away (and indeed, in fulfillment of the Refusal of the Call, probably will do so). Not until the Key Event/First Plot Point will one or both initiate an active choice to engage with one another in a way that neither can subsequently walk away from unchanged. Continuing with the romance example, this “engaging with the conflict” might be as simple as the two leads deciding to go on a first date and begin their relationship. On the other hand, in an adventure story or the like, the protagonist will make a choice to pursue the plot goal that later (in the second half of the beat) will pit him against the antagonistic force in some way.

Regardless of genre, the Key Event is the protagonist’s response to the Inciting Event. It is a further reversal from the Refusal of the Call. Whether or not the character really wants to or is yet committed to fully engaging with the conflict and leaving the Normal World for the Adventure World, she is at least making a choice to do something about the situation. Therefore, the Key Event is when the protagonist engages with the conflict.

The First Plot Point (Door of No Return)So then, if the Key Event is where the protagonist chooses to do something to respond to the Call to Adventure and engage with the main story goal in some way, what then is the First Plot Point?

As ever, the point of there being two halves to the major structural beats is that these halves create an “arc” or a reversal of value. This value will be inherently emotional, but particularly in the case of the First Plot Point it should be dramatized through physical value as well.

If the Key Event is about the protagonist’s choice to respond to the Call to Adventure, the First Plot Point proper is then about the consequences of that choice.

You can also think of it like this: the Key Event is something the protagonist causes to happen; the First Plot Point is something that happens to the protagonist.

But, of course, the link between the two is not random. As with all good story developments, what the character suffers should always be a direct result of his own choices (if not necessarily his culpability). The most interesting character development almost inevitably arises from consequential situations for which the character must, in some way, take personal responsibility.

Back to our metaphor of the doorway, the protagonist’s decision to engage with the Key Event allowed her to step into the Doorway of No Return. Now, in the second half of the beat, we get to discover just what that choice entails and why it is one from which there is “no return.”

In adventurous or dramatic stories, this principle of “no return” is often created by literally destroying the protagonist’s Normal World or in some way barring him from it. For example, in The Terminator, Sarah Connor’s friends are murdered and she herself is attacked and must leave her Normal World to go on the run from her would-be assassin.

In a romance, the consequences are usually much less violent and perhaps even implicit, in that the now-dating (or whatever) characters must begin to grapple with the incompatibilities, great and small, of their new relationship.

You can also see less dramatic but still absolutely consequential First Plot Points in stories such The Great Escape in which the First Plot Point signals the departure from the Normal World of the prison camp simply by having the characters begin digging their escape tunnels. These tunnels both represent the new Adventure World of the Second Act and also represent a course of action from which the characters cannot turn back, since the evidence of their escape attempt is now writ permanently within physical reality.

In this instance, the true consequences are delayed (in fact, until the Midpoint when one of the tunnels is discovered by the German guards), but what is important is that the characters’ choices in the Key Event and their actions/reactions in the First Plot Point cannot be reversed. The characters have committed to the main conflict—and the Second Act can now roar out of the station.

Within the nomenclature of classic scene structure, the Key Event can be seen to be the character’s Goal (and therefore decision to act), with the First Plot Point functioning as the concluding Disaster—which, in this case, will prompt the need for the entire subsequent plot.

Together, the Key Event and the First Plot Point create that all-important threshold of the Door of No Return between the First and Second Acts. If you can get your protagonist through that door, then you can be sure you’ve also gotten your story off to a good start.

***

Stay tuned: Next week, we will take a look at the two halves of the Midpoint: the Plot Reversal and the Moment of Truth.

Previous Posts in This Series:

The Two Halves of the Inciting EventWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify both the Key Event and the First Plot Point in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Two Halves of the First Plot Point appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.