The Two Halves of the Midpoint

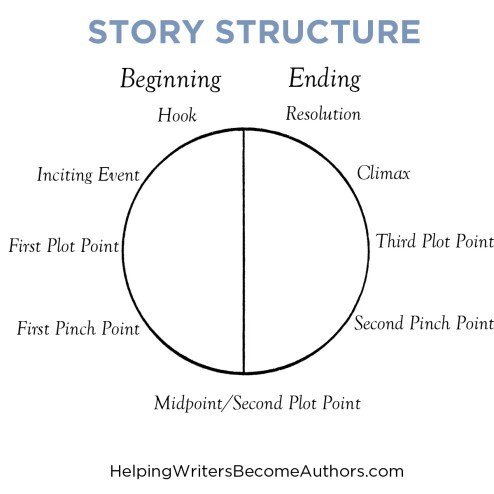

The Midpoint is unique among the major structural turning points. Not only is it made up of its own two individual halves—working together to create a scene arc—but the Midpoint also marks the dividing line between the two halves of the entire story arc.

The Midpoint is unique among the major structural turning points. Not only is it made up of its own two individual halves—working together to create a scene arc—but the Midpoint also marks the dividing line between the two halves of the entire story arc.

As we explored last year in our series on chiastic structure (or how the structural beats in the two halves of the story mirror one another—e.g., the link between Inciting Event and Climactic Moment), the Midpoint is also unique in that it stands alone at the “top of the circle” with no partner or mirroring beat. Rather, the Midpoint notably offers what James Scott Bell so brilliantly calls “the Mirror Moment.” This is a moment within the story, usually inherent within the thematically all-important Moment of Truth, in which the characters are given the opportunity to see truths about themselves “as if in a mirror.”

What the Midpoint (or Second Plot Point) does have in common with all the other major structural beats is that it, too, is comprised of two halves. This is, of course, because the Midpoint is a scene (or sequence of scenes) in its own right, offering a complete scene structure and emotional arc.

In the previous two posts, we started talking about how each of the major structural turning points is made up of two intrinsic parts which together serve to “reverse the value” of the scene by moving the character through some progression of Goal to Disaster. In all the beats, both halves are important for properly turning the plot.

The beats we’re exploring are:

Inciting EventFirst Plot PointMidpoint (or Second Plot Point)Third Plot PointClimactic MomentWhat Is the Midpoint?

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

As the centerpiece of the story, the Midpoint in many ways encapsulates the entire point of the story. Plot, character arc, and theme all coincide here (more obviously even than usual) to provide the protagonist with at least the opportunity to see the world in a different and potentially more functional way than previously. Depending on what the character realizes and accepts at the Midpoint, he should be able to use this new knowledge to move onward more effectively toward the plot goal.

This is why the Midpoint structurally marks the transition from the “reaction” of the First Half of the Second Act (in which the character lacked sufficient understanding to combat the obstacles of the antagonistic force) to the “action” of the Second Half of the Second Act (in which the character uses the Midpoint’s revelations to aid in a more proactive approach to avoiding/defeating the antagonistic force and gaining the plot goal).

Although the story goes on and the conflict will not be definitively decided until the Climactic Moment, the Midpoint is really the moment that determines the protagonist’s fate. Whether or not the character “gets it” in the Midpoint will determine whether or not the resources for a climactic victory will be available come the end.

Recognizing the Arc Created by the Two Halves of the MidpointIf your story is a mountain, then the Midpoint is the peak. When your protagonist reaches the Midpoint, she will stand with one foot on either side of the peak. In other words, the first half of the Midpoint takes place in the first half of the story and the second half of the Midpoint in the second half of the story. Like the First Plot Point, it can be viewed as a doorway through which the character must step.

As such, since we know the first half of the story features the protagonist in a “reactive” mode and the second half features an “active” mode, we can know these two halves must also define the Midpoint itself.

The Midpoint is usually a major set-piece scene in some way. In an action story, it will probably be a battle or some such. In a more relational story, it may be a dramatic confrontation. The protagonist will enter this set-piece scene lacking some crucial bit of information, which currently renders him “reactive.” He is trying in some way to score a major victory here, but because he lacks all the necessary information, even his greatest display of initiative ultimately remains reactive.

But the Midpoint itself will change all that by offering crucial new insights and information. Even though the Midpoint itself may be a categorical defeat for the protagonist, the information gained here means she can now sally forth into the second half of the story much better equipped to score victories in the future.

Intrinsically, the two halves of the Midpoint represent a coming together of the external and internal conflicts—and how each influences the success or failure of the other. The first half is that of a Plot Revelation (or reversal); the second half is that of the thematic Moment of Truth. In short, the first half offers paradigm-shifting new information, while the second half is about the new internal understandings that arise from this information. The character not only learns something in the outer world, but also discovers new knowledge within himself.

Let’s take a closer look.

The Plot RevelationIn “plot-driven” stories, the Plot Revelation will take center stage at the Midpoint. Sometimes it will even appear that the Plot Revelation is the Moment of Truth. Indeed, this may sometimes be the case, although only in stories that feature little to no character development or arc. It is also true that because the subsequent Moment of Truth is caused by the Plot Revelation, the two are intrinsically linked, sometimes to the point they seem one and the same.

However, from a structural and technical point of view, it is valuable to see their separate cause/effect, push/pull relationship.

Specifically, the Plot Revelation is information the protagonist learns about the external plot. This information may be told through dialogue, but due to the dramatic nature of the Midpoint, it is just as often information that is dramatized (e.g., a wife walks in on her husband having an affair).

Because of the “internal truth” nature of the linked Moment of Truth, the most effective approach is often to communicate the Plot Revelation to the protagonist “in a flash.” It lands in a way that is less about “teaching” the protagonist something new (although it certainly can) and more about “uncovering” the inner Truth that has been slowly consolidating for the protagonist over the course of her character arc so far.

Put another way, even if the events of the Midpoint are utterly unexpected and shocking, they still feel like a sensible progression. (From a craft point of view, foreshadowing in the first half of the story is, of course, the vital ingredient to conveying this feeling to readers.)

Basically, the Plot Revelation’s main job is providing the protagonist with the single most important bit of information about why his attempts to gain the plot goal have so far been less than effective. After all, he’s been trying all this time—why doesn’t he have it by now?

The Plot Revelation shows him what is holding him back. If he’s a scientist, this may be a mistake in his calculations. If he’s trying to make a relationship work, it may be his own (and his love interest’s) intrinsic fears of vulnerability, intimacy, and commitment. If he’s trying to catch the bad guy, the revelation may be about the bad guy’s true identity or motivation. Or if he’s simply trying to survive in a wilderness situation, the revelation may be about why he’s sure to die if he doesn’t change tactics and somehow escape.

The possibilities are vast and varied. Although the new information must be dramatic enough to turn the plot, the revelation itself can be conveyed with relative subtlety. In some movies, the Midpoint is as subtle as a shift of the protagonist’s expression while watching the sunset (although usually this only happens in “character-driven” stories in which the conflict is mainly internal and the emphasis is almost entirely on the Moment of Truth rather than the Plot Revelation).

The other important aspect of the Plot Revelation is a plot reversal. It is not enough for the protagonist to simply learn something new and experience a revelation. If the Midpoint is to properly move the plot, she must act upon it—she must change the story.

The Moment of TruthIf the Plot Revelation is something that essentially happens to or is given to the protagonist, the subsequent Moment of Truth is about the protagonist then taking ownership of that information and using it to manifest a significant change of perspective.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

In contrast to the Plot Revelation, which is about the external conflict, the Moment of Truth is specifically about the inner conflict—and therefore is more representative of progressive change in the character arc and theme.

Up to this point, the protagonist will have been operating from a less and less effective Lie-based mindset, in which he holds to some fundamental and increasingly dysfunctional misinformation about reality. Practically, this Lie is what has ultimately caused him to be less than successful in the outer plot (even though the Lie itself is not the specific information from the Plot Revelation about “how to defeat the antagonist”). His semi-failures up to this point have been teaching him a new and counteractive Truth.

It is the Moment of Truth, spurred by the events and information of the Plot Revelation, that suddenly brings this seed of Truth into full bloom. The character not only learns something important about where she is going wrong in the outer conflict, but she also recognizes, at least implicitly, the limited personal perspective that has ultimately led her to make these external mistakes.

If the character accepts this new perspective (as she will in a Positive-Change Arc), she will be able to move forward into more and more successful interactions with the external world.

However, don’t forget this is only the Midpoint of the story. Plenty of plot and character arc remains to happen. So although the character here realizes the essential Truth of his story, he does not yet realize or find himself capable of completely rejecting his previous misconception or Lie. And so his evolution will continue in the second half of the story, until the Third Act when he finally realizes that the Truth cannot be fully effective unless he is also willing to entirely reject the Lie—in short to die to the Lie and be reborn in the Truth (a painful process that should never be taken for granted even with comparatively “small” perspective shifts).

Together, the Plot Revelation and the Moment of Truth provide the necessary cause and effect to create massive change within the Midpoint. They also work in tandem to beautifully unify plot, character, and theme into a cohesive whole.

If you can make sure the Midpoint of your story features both of its important halves, you can be sure you’re taking full advantage of its deep potential for elevating your entire story.

***

Stay tuned: Next week, we will take a look at the two halves of the Third Plot Point: the False Victory and the Low Moment.

Previous Posts in This Series:

The Two Halves of the Inciting EventThe Two Halves of the First Plot PointWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify both the Plot Revelation and the Moment of Truth in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Two Halves of the Midpoint appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.