K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 19

May 23, 2022

Deepening Your Story’s Theme With the Thematic Square

How can you deepen your story’s theme? This is a question most writers find themselves asking at one point or another. And there are many answers.

How can you deepen your story’s theme? This is a question most writers find themselves asking at one point or another. And there are many answers.

As an inherently abstract concept, theme can be approached from many different directions—and still feel hard to get at. But as one of the most important factors in creating a story with meaning, cohesion, and resonance, theme must be approached with practical understanding at least at some point in the writing process. I’ve written extensively on this site and in my book Writing Your Story’s Theme about how writers can use a practical understanding of plot structure and character arc to consciously craft and hone integral themes.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Basically, this approach revolves around the realization that character arc reveals and proves theme, while plot structure creates and unfolds character arc. In order for any of the “big three” of plot, character, and theme to truly work, all three must be in alignment. This means that if you’ve got a plot that works or a character arc that works, it’s pretty likely you also have a theme that works. And if any of the three doesn’t work, you’ll at least have clear problems to solve on your way to strengthening all three.

But are there any other practical tools you can use in deepening your story’s theme?

First of all, what does it even mean to “deepen” theme?

It might mean simply to “improve” the theme. But often, writers who are seeking a deeper theme are, in fact, looking for ways to expand upon their thematic argument and delve deeper than simplistic good/bad explorations of moral premises. Good stories will be complex enough to generate many different thematic queries, some only tangentially related to the main premise (which is fine as long as they’re not given major screentime). This, however, can get tricky fast, since sometimes even simple themes can be difficult to execute with cohesion. There is a vast difference between a properly complex theme, in which a single simple idea is explored from multiple angles, versus a complicated theme, in which too many disparate ideas are being thrown at the wall and too few are actually sticking.

Story by Robert McKee (affiliate link)

In increasing the complexity of a story’s theme, one tool I personally use and love and about which I am frequently asked is Robert McKee’s “thematic square.” He talks about this approach in his exceptional screenwriting classic Story (a must-read for anyone passionate about story theory). Today, at the request of several of you, I will offer a quick overview of this technique, and I how I use it.

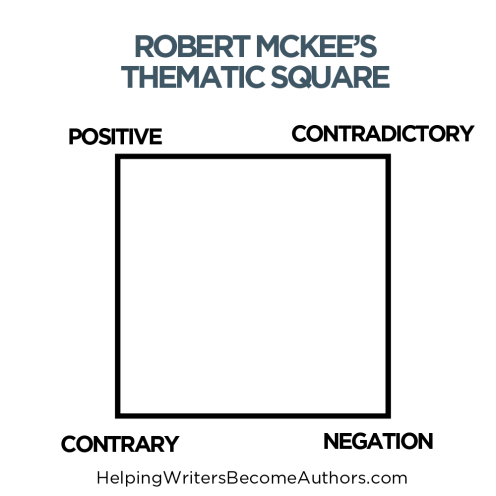

What Is the Thematic Square?The simplest way to approach theme is through the polarity of the protagonist’s view of the world (whether accurate or not) versus an opposing view of the world. In teaching character arc, I refer to this polarity as the Lie and the Truth. However, this is necessarily a very black and white description of any thematic argument. These terms are only meant to be representative of the protagonist’s relative views at the beginning and ending of the story; they are unlikely to represent moral absolutes. To the degree they do, stories can often end up feeling moralistic and on the nose. As McKee points out:

Life … is subtle and complex, rarely a case of yes/no, good/evil, right/wrong. There are degrees of negativity.

He then develops those “degrees of negativity” into three specific categories of thematic viewpoints that progressively distance themselves from a basic “positive” view (what I refer to as the thematic “Truth”). Together, the positive Truth and its three counter-views can be seen to form a thematic square:

Instead of the positive Truth being simply opposed by a negative Lie (or call it a Counter-Truth if you prefer) of equal force, it is instead challenged by many nuanced arguments. Thanks to this realistic variation, the story can explore both clearly awful alternatives to the Truth as well as subtler ideas that may, in fact, offer convincing arguments against the Truth.

Wayfarer (Amazon affiliate link)

For example, here is the thematic square I concocted when writing my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer:

Positive thematic Truth: Respect

An aspect that is outright Contradictory to the Truth: Disrespect

Another aspect that is perversely Contrary to that Truth: Rudeness

The Negation of the Negation, which is an atmosphere in which the Truth doesn’t even exist: Self-Disrespect

In his book, McKee offers several other examples, including this excellent one:

Positive: Love

Contradictory: Hate

Contrary: Indifference

Negation of the Negation: Self-hate

Four Corners of Your Story’s Thematic Truth You Can ExploreNow, let’s dive a little deeper and explore each of the corners of this thematic square.

1. PositiveIn my explorations of story, I refer to the positive value of the theme as the thematic Truth. Although it may be a relative truth that is pertinent specifically to your character and your story, it will usually be rooted in something deeper and more universal. McKee says:

Begin by identifying the primary value at stake in your story. For example, Justice. Generally, the protagonist will represent the positive charge of this value; the forces of antagonism, the negative.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

In a story in which your protagonist fulfills a Positive Change Arc, he will start out believing a Lie (probably one of the thematic “anti-values” in the below categories) and, gradually, over the course of his story come to recognize and embody the Truth. In a Flat Arc, the protagonist will embody the Truth throughout the story, using it to combat other characters’ Lies and encourage change in some of them. In a Negative Change Arc, the protagonist may or may not represent the Truth in the beginning of the story, but will eventually fall away from it by the end.

2. ContradictoryThe contradictory thematic value is the simple binary opposite of the positive thematic Truth. In a story with a clear-cut “good guy” and “bad guy,” the good guy will usually obviously represent the positive value, while the bad guy will obviously (and sometimes mindlessly) represent a contradiction to that value. McKee puts it:

….the Contradictory value [is] the direct opposite of the positive. In this case, Injustice. Laws have been broken.

Although simplistic, the contradictory value is crucial within the story since it represents the fundamental polarity found within the thematic argument. However, by its very simplicity, it can create realism issues for writers who over-rely on it. After all, in most simplistic situations, most people would easily choose the positive value over the negative. If life were always as simple as that, there would be no struggle to reject Lies in favor of Truths—and thus no stories!

3. ContraryNow things start to get more complicated—and interesting. As McKee says:

Between the Positive value and its Contradictory … is the Contrary: a situation that’s somewhat negative but not fully the opposite. The Contrary of justice is unfairness, a situation that’s negative but not necessarily illegal: nepotism, racism, bureaucratic delay, bias, inequities of all kinds. Perpetrators of unfairness may not break the law, but they’re neither just nor fair.

The contrary value of your theme is where the nuances began to appear. At first glance, some of the contraries of your positive theme may seem “less bad” than its outright contradiction. Via McKee’s example, we might initially be inclined to say that “unfairness” is not so bad as “injustice.” And yet, here we find the slow fade, the gray areas that can lead us to compromise our own basic values, sometimes without even fully realizing it.

It is in the contrary aspect of the theme that your protagonist will be most tempted to abandon the difficult high road of the positive Truth. Indeed, in not accepting or allowing some contrary aspects, the character makes it all the harder for herself to truly embody the Truth. For instance, a boxer unwilling to compromise his sense of integrity and justice in the face of pressure to throw a fight may find this causes him to become the victim of a true injustice that threatens his very life.

4. Negation of the NegationFinally, McKee finishes out his square with the “negation of the negation”:

At the end of the line waits the Negation of the Negation, a force of antagonism that’s doubly negative…. Negation of the Negation means a compound negative in which a life situation turns not just quantitatively but qualitatively worse. The Negation of the Negation is at the limit of the dark powers of human nature. In terms of justice, this state is tyranny.

In essence, the negation of the negation is an ideology or state of being in which the theme is flipped on its head: right becomes wrong, wrong becomes right. The negation of the negation is the thematic Lie taken to its furthest extreme. Disrespect of others eventually leads to disrespect of self and of all life. Hatred leads to a total moral vacuum: evil. Injustice leads to unmitigated oppression.

Obviously, this aspect of your theme offers tremendous dramatic possibilities. You may choose to fully portray the consequences your character and the story world will face (or already face) if the protagonist fails to embrace and embody the high side of the theme. Stories such as Lord of the Rings, Hunger Games, and Schindler’s List come to mind.

But you can also use simply the specter of the negation of the negation in subtler ways to symbolize what is at stake for your character. Even in “quiet” stories, the negation of the negation is usually what shows up, in some form or another, at the story’s Low Moment or Third Plot Point. For example, in a romance where the positive theme might be “love,” the protagonist may have just broken up with her love interest, believing they can never make it work. Now, at this Low Moment, she is faced, however briefly or symbolically, with a horrifying negation of the negation: loneliness as the absence of love.

One More Trick: Combining McKee’s Thematic Square with Truby’s Conflict SquareSo how do you apply McKee’s thematic square to your story? Your protagonist’s inner conflict is one aspect of the story in which you can (and should) explore all four nuanced corners of your theme. But you can also powerfully externalize your character’s inner conflict onto the outer conflict of the plot. You do this by identifying certain supporting characters in the story who can represent different corners of the thematic argument.

The Anatomy of Story by John Truby (affiliate link)

This ties in beautifully with the idea of the “four corners of opposition,” which John Truby presents in his Anatomy of Story. His proposition is that of ensuring that your protagonist is not simply opposed by the antagonist, but rather by multiple characters, who in turn oppose not just the protagonist on some level but all the others as well.

This is an excellent approach for breathing dimension into your characters and your conflict. After all, how often in real life are we perfectly aligned with our allies—or even perfectly opposed to our opponents?

Truby illustrates this idea particularly as a square representing four characters (personally, I always default their identities to the four primary character roles of protagonist, antagonist, sidekick, and love interest—or alternately the contagonist sometimes). However, you can actually apply the idea of “conflict from all sides” to every character in your story. This doesn’t mean your protagonist’s mom has to be coming after him with a butcher’s cleaver. But it does mean that even good ol’ Mom should have some goal or belief that conflicts with the protagonist’s in however small a way.

Overlaying this idea atop McKee’s thematic square gives you a guide for assigning a plethora of worldviews to your characters while still keeping them all thematically pertinent. For instance, as McKee noted in his description of the contrary aspect of theme, there may be many different contrary ideas to the main positive thematic Truth. If your story takes up McKee’s example to explore a positive theme of Justice, then you could choose to develop any or all of his contrary suggestions through individual supporting characters: nepotism, bureaucratic delay, etc.

As with any exploration of theme, you don’t want to get too obvious about this. Characters, including the antagonist, need to be fleshed out beyond serving as basic foils for your protagonist’s thematic exploration. But if you can craft characters who authentically represent differing arguments or aspects of the theme, your story’s complexity and depth will expand almost all on its own.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever explored the thematic square in your stories? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Deepening Your Story’s Theme With the Thematic Square appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 16, 2022

6 Ways to Find Your Best Ideas Before You Start Writing

For writers, ideas are the primal matter. No ideas, no stories. But sometimes trying to figure out how to find your best ideas is like catching butterflies. They flit in; they flit out. If we aren’t paying attention, sometimes we don’t even recognize that they’ve been there. Even when we do stop short in awe of their beauty, we risk damaging them if we get too excited and try to capture them too quickly or too forcefully.

For writers, ideas are the primal matter. No ideas, no stories. But sometimes trying to figure out how to find your best ideas is like catching butterflies. They flit in; they flit out. If we aren’t paying attention, sometimes we don’t even recognize that they’ve been there. Even when we do stop short in awe of their beauty, we risk damaging them if we get too excited and try to capture them too quickly or too forcefully.

Not all ideas are this fragile, of course. There are different kinds of ideas. There are solid, logical, left-brain ideas. These are the ones we feel in control of. We come up with them. We guide them. We get to decide whether our protagonists take Road A or Road B because we are the ones who have also decided what’s going to be at the end of those roads.

But other ideas—the butterfly ideas—are more ephemeral, spontaneous, right-brain ideas. These are the “inspired” ideas, the ones gifted to us from beyond our own conscious understanding. These are the ideas that happen when our subconscious takes over. The story writes us rather than us writing the story.

Wild Mind by Natalie Goldberg (affiliate link)

Although both types of ideas are crucial to the process of wrangling a story into cohesion and resonance, I’d argue the right-brain ideas are really the true substance. Inspiration, after all, is every writer’s absinthe. But inspiration cannot be forced. Indeed, inspiration can’t even really be caught. When the left brain tries to take over a new idea and tame it, the idea may either die in captivity or fade to a pale version of itself. As Natalie Goldberg laments at one point in Wild Mind:

[The] problem was that I froze the inspiration into an idea before I even began to actually write.

Subconscious ideation can only be observed, appreciated, and recorded carefully. We must each find our own balance for making sure our ideas don’t leave the preserve, while still letting them run wild on the page. But this can be easier said than done, since all creative spontaneity and no conscious control doesn’t lend itself very well to the true craftsmanship of writing.

6 Ways to Find Your Best Ideas—Before You Start Writing ThemIn the 20+ years I’ve been writing, I have noted that my best process is never one that hurries ideas. It lets the ideas come to me—as gifts, surprises. And then it waits, patiently, to see if another idea will come and perhaps yet another.

A motto that has served me well is:

One idea does not a story make.

The rationale behind this is that if I try to sit down and write an entire story based on just one idea (or perhaps even a small handful of ideas), I inevitably end up filling in most of the story with left-brain ideas. The stories can be still be pretty good this way, but in my view neither the process nor the product is the same as the stories with a higher ratio of right-brain ideas.

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

I feel this holds true whether your preferred process is to discover your story in the outline or to discover it in the first draft. Regardless, it’s about getting our conscious brains, with their know-it-all tendencies, out of the way long enough for us to tap into the zone and see what might be waiting for us in a deeper reservoir of inspiration. Goldberg went on to say:

The initial subject matter might not have anything finally to do with what we really need to say. Just keep your hand moving and let whatever is about to happen unfold. Let writing do writing. Don’t manipulate it with your ideas about what you think should happen.

Obviously, there is a time and a place for doing exactly the opposite. For example, this is not the approach you want to take when troubleshooting your plot. But it’s also true that it’s difficult to truly discover a story when your conscious brain is determined it already knows what it’s going to find.

If you’re like me—with an inordinately loud and bossy conscious brain—then you might benefit from the following six ways to find your best ideas as you cultivate, channel, and honor your deeper inspiration.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

(And if you feel your left brain is the half that most needs the gym, I recommend studying plot theory, particularly story structure, which will help you make better conscious decisions about your story. Also see this post: “Writing as the Art of Thinking Clearly: 6 Steps.”)

1. Treat Ideas Like Butterflies—Just Watch at FirstI still believe the best part of the writing process is the daydreaming. That’s how it all started for me, as I imagine it did for many of you, just lazily watching the “movies” in my head—random images, characters, and scenarios that would present themselves to my mind’s eye. It’s the adult(-ish) version of playacting in the backyard. There’s no forcing, no pursuing—just watching and appreciating.

2. Capture With Care—Don’t TouchWhen I was young, I would catch butterflies—Monarchs and Yellow Swallowtails. I’d pinch their wings between my fingers for a moment, just to get a better look. But then I noticed the colors of their wings flaking off in my hand and learned that my gentle inspection might just have crippled those delicate butterflies. I let the butterflies alone now.

And in their early iterations, I treat my ideas the same way. I don’t let my conscious brain anywhere near them. In the very beginning, I won’t even scribble down notes. I relate strongly to what Goldberg reported about “freezing” inspiration before it even has a chance to fully emerge from the cocoon and reveal to me its true (and often surprising) potential.

3. Keep Watching—Add More Ideas to Your CollectionThe longer I’m able to wait and watch my growing collection of ideas for any particular story, the richer the trove I end up with. Some stories have matured, undisturbed, for years. Those are almost always my favorite ones to write. When I sit down to outline, the plot is usually all but complete. All I have to do is tweak a few things and add a few scenes. Other stories, with far fewer organic ideas to draw from, are still rewarding to write, but they’re almost always a lot more work—and, interestingly, not always as logical.

Of course, you don’t have to wait years for ideas to mature. Indeed, if your best writing process is to use writing itself to ideate, then just letting rip in the first draft, as Goldberg suggests, can afford you a deep, almost meditative brainstorming safari. Regardless your process, your right brain is usually a better judge of a story’s readiness to be written than is your left brain. I often gut-check myself with Margaret Atwood’s pithy notation:

4. Seek Them Out—Purposefully Dreamzone…you know when you’re not ready; you may be wrong about being ready, but you’re rarely wrong about being not ready.

Even when you’re trying to get quiet and let your right brain speak to you, nobody says you have to wait for ideas to come to you. Jungle expeditions are always valuable. Discovery writing, as noted above, is one way of doing this. Just… write. Put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard and see what you find.

One of my favorite exercises is one I’ve discussed before. I call it “dreamzoning.” Basically, it’s daydreaming on steroids. Make a date with yourself to sit down, zone out, and intensely focus on imagining your story. You’re not logically creating a plot or solving problems. Rather, you’re visiting that same place in your brain where you go to daydream—where pictures and ideas arise spontaneously. For me, semi-darkness and music is helpful for tapping into that place.

5. Let Your Subconscious Write More of the Story Than Your ConsciousEven if you’re a heavy-duty outliner who plans all the big-picture twists and turns of the plot before writing the first draft, you will still want to approach the actual writing of the story from a place of curiosity and surrender. One of the chief pitfalls of writing with an outline can be the loss of spontaneity and inspiration in the actual writing. Instead of methodically plodding from known plot point to known plot point, seek to access that same “dreamzone” when in the throes of hammering out the words of your story’s first draft. Even if you need to stop and check your map every now and then, focus on the lived experience of dreaming the story onto the page.

6. Brainstorm to Fill in the Gaps—Carefully

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

None of this is to discount the importance of consciousness and logic in crafting your story. Story is both art and craft. At a certain point (probably many points) in the process, you will need to step back from the heady rush of writing from the zone and examine your story logically. Everything from spelling and sentence structure on up to plot structure and character arc will benefit from a conscious organization.

The trick is to do this carefully, to use your knowledge and understanding of story technique to help you fill in blanks and guide the story on its most resonant path—without disturbing your connection to your deeper creativity. We’re unlikely to find all the ideas or guidance we need in the dreamzone. We have to surface for air and orientation every now and then. But we should be seeking a balance between the raw flow and the careful course-correction. To the degree we over-correct, we often end up feeling, as Gail Carson Levine put it, that:

Ideas are ideas, and words on paper are words on paper; they’re not the same thing, no matter how much we try to convince ourselves.

***

The amount of time you need to spend in the wilds will be different for any given story. But returning again and again to this primal inspiration will keep your compass straight and help ensure you’re writing the stories you really want to tell. In relation to all this, I also found the following quote from Goldberg to be resonant and inspiring:

[I realized] I wouldn’t be so afraid to die because I would have been busy dying in each book I wrote, learning to get out of the way and letting my characters live their own lives.

To me, this speaks of tapping that deep, raw creativity and letting the stories write us as much as we write the stories.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Where do find your best writing ideas? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 6 Ways to Find Your Best Ideas Before You Start Writing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 9, 2022

The Role of the Antagonist in Story Structure, Pt. 2 of 2

One way to think about plot is as a “push-pull between protagonist and antagonist.” Although the protagonist is the character who frames and, indeed, decides the story’s structure, the role of the antagonist in story structure is equally important.

One way to think about plot is as a “push-pull between protagonist and antagonist.” Although the protagonist is the character who frames and, indeed, decides the story’s structure, the role of the antagonist in story structure is equally important.

Last week, I shared an overview of the antagonist’s role in the first five major structural beats within a story. I originally intended it to be one post, but it turned out to be nearly twice as long as usual, so I split it in two. Today, we’ll be rounding out the subject by examining the role of the antagonist in the second half of a story’s structure—the Second Pinch Point through the Resolution.

Once again, it is important to remember the distinction between the antagonistic force that impacts storyform in a general sense and the antagonist who is a specific character representing this force within the story.

1. The antagonistic force will function in fixed (and therefore relatively universal) ways within story structure, in order to evoke the most resonant responses from the protagonist.

2. The antagonist, as a human character, however, will be much more dynamic and even unpredictable within the story. What I’ve shared in this series is focused more on the antagonistic force’s impact upon the structure, and is therefore very general. Within your specific story, the antagonist as a character may function in ways much more nuanced than what is presented here.

The Antagonist’s Role in the Second Half of a Story’s Structure6. The Role of the Antagonist in the Second Pinch PointFor the protagonist, the Second Pinch Point mirrors the First Pinch Point in emphasizing the stakes and the potential threat of the antagonist. Specifically, it will foreshadow the “Low Moment” of the Third Plot Point to follow. Whatever the antagonist threatens here will be significantly endangered or destroyed later in the Third Plot Point. However, the very threat itself is what prompts the protagonist into the (possibly hubristic) gambit of the False Victory that precedes the Low Moment.

For the antagonist, the Second Pinch Point also mirrors the First Pinch Point in representing a moment of significant aggression (to whatever degree) against the protagonist. Here, the antagonist flexes his muscles, acting from his place of strength after the Midpoint. His strength is real, but because he has not gained any new insights (either practically or thematically), his ability to adapt to the forward momentum of the plot is beginning to stall out. In short, the protagonist is evolving faster than the antagonist—and this will be the deciding factor in the end.

Antagonist’s Role in the Second Pinch Point: The antagonist will initiate the events of the Second Pinch Point based on his advancements at the Midpoint. From his perspective, what he enacts here may seem like the beginning of the endgame. He may push back at the protagonist in the belief that one more shove will be enough to topple his foe and remove the protagonist as an obstacle. However, he will likely overestimate his own position and underestimate the protagonist’s. As a result, he may not even fully realize that the effort he expends here does not have its desired effect. The protagonist may seem to retreat, but unbeknownst to the antagonist, this retreat is only so the protagonist can gather her forces for what the protagonist deems as the beginning of the endgame.

7. The Role of the Antagonist in the Third Plot PointAt the Third Plot Point, everything changes for both characters. The protagonist initiates this major beat with a calculated pushback against the antagonist (or, alternatively, toward the protagonist’s own plot goal). In many ways, the protagonist’s gambit will succeed. She will use what she has learned in the previous beats to overcome the obstacles that once stymied her. She may well strike a significant and damaging blow against the antagonist. But because of her own ongoing and incomplete inner conflict between Lie and Truth, she will also pay a huge price for this attack. For the protagonist, the two sides of the Third Plot Point can be termed False Victory and Low Moment.

For the antagonist, this beat is similarly complicated. On the one hand, the protagonist just hit him where it hurts. Prior to this, the antagonist believed himself in a good position from which to triumph. Now, his weaknesses and blind spots have been exposed. But on the other hand, as we’ve already seen, this was a Pyrrhic victory for the protagonist—meaning the antagonist may still be able to win, if only by default. Both parties will retreat to lick their wounds. From here on, a final confrontation is not only necessary but inevitable. Their next meeting will decide who will reach their ultimate plot goals and who will not.

The Role of the Antagonist in the Third Plot Point: The antagonist will be consolidating his own resources and preparing for a major pushback against the protagonist as well. He may receive the protagonist’s efforts with some sort of ambush, which turns the tables on the protagonist at the last minute. The antagonist will not be defeated here and may even gain some significant ground in the overall conflict. However, for the antagonist too, the Third Plot Point will usually represent a comparatively desperate moment. Time is running out; both parties will recognize that the conflict will soon have to be decided. Although the antagonist may well still hold at least a slight advantage over the protagonist, the playing field will have leveled some since the beginning of the conflict. Even if the antagonist’s goal is within reach, he is still likely to be feeling the tremendous pressure of the stakes.

8. The Role of the Antagonist in the ClimaxThe Climax properly begins halfway through the Third Act and will ramp up to varying degrees until the Climactic Moment at the end of the entire story. This turning point is what moves the protagonist and antagonist out of their respective reactions to the Third Plot Point and into their final confrontation.

This confrontation may be directly between these two characters and may even be the entire point of the story. One character will defeat the other. This defeat is either the goal of the story or the single remaining obstacle to enabling the goal.

However, the “confrontation” may also be indirect or even incidental. It’s possible the protagonist’s final pursuit of her goal may not require that she directly move against or overcome the antagonist; rather, just in doing whatever she must to triumph in her own goal, she may incidentally defeat the antagonistic force. The latter is particularly likely in stories that focus on inner or relational conflict.

The Antagonist’s Role in the Climax: At this point in the story, it is more important than ever to keep in mind that the antagonist is a character with personal desires and goals of his own. Although his primary goal at this point may indeed be to destroy the protagonist, he must still be pursuing that end for a reason—and now that the conflict has reached its final deciding stroke, that reason will be more important to the antagonist than ever. What he has been working toward throughout the story is about to be decided in a definitive way. Even if the stakes seemed higher for the protagonist throughout most of the story, now the playing field has been leveled. The antagonist has every bit as much at stake as does the protagonist.

9. The Role of the Antagonist in the Climactic MomentThe Climactic Moment ends the Climax—and the plot conflict. It is the moment that decides who “wins” and who “loses.” In a positive story, the winner is almost always the protagonist. However, the concept of “defeating” the antagonistic force should be understood in the context of the obstacles having been removed from between the protagonist and her ultimate plot goal. This is what brings the conflict to an end. (Thus, it is not so much that there is no conflict without an antagonist, but more so that there is no antagonist without the need for conflict.)

In a story in which the predominate aspect of the antagonistic force is found within the protagonist, the external antagonist’s ultimate positioning within the finale will not be as important. For instance, returning to last week’s example of a story about competitors, the protagonist’s victory may be moral than literal. Even if it is a literal victory within the competition, the emphasis will be less on the protagonist’s having overcome at the antagonist’s expense and more on the protagonist’s own inner transformation into strength.

In fact, in some stories the conflict will end with the protagonist and antagonist resolving their differences and perhaps even mutually claiming the plot goal.

The Antagonist’s Role in the Climactic Moment: The Climactic Moment functions similarly for both characters. It is the beat in which the conflict ends. The relationship of both protagonist and antagonist to their plot goals will be definitively decided, via their actions, in some way. There will be no forward progression toward this particular goal any longer.

10. The Role of the Antagonist in the ResolutionThe Resolution is the beat after the Climactic Moment. In most stories, it will be given at least a scene, maybe more. In other stories, it is literally nothing more than a beat. It is the closing note in the story, the “fade out.” Functionally, it exists to provide closure to the cause and effect of the entire story and the Climactic Moment in particular. It shows the reactions of the protagonist and antagonist to what just happened.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

The Antagonist’s Role in the Resolution: In many stories, the antagonist will not be present for the Resolution. Either he will have been functionally eliminated from the story world (killed off, banished, etc.), or he will have become irrelevant to the protagonist now that he is no longer an obstacle. In other stories, particularly those in which the antagonist is an important relationship character, the Resolution may offer a conciliation between the characters. This may range from a full-on partnership agreement between them to merely a shaking of hands and a nod of respect before they go their separate ways. It is also possible that one party (probably the protagonist if she’s following Positive-Change Arc) may be willing to reconcile but the other is not and simply walks away, effectively banishing himself.

***

Too often, we synonymize “antagonist” with “bad guy.” From a structural perspective, the antagonist is merely a force opposing the protagonist’s forward progress and therefore prompting the protagonist’s growth. Understood in this way, the role of the antagonist in structure can be strengthened to create a more rounded and convincing story at every beat.

Related Posts:

The Role of the Antagonist in Story Structure, Pt. 1Wordplayers tell me your opinions! What sort of character is the antagonist in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Role of the Antagonist in Story Structure, Pt. 2 of 2 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 2, 2022

The Role of the Antagonist in Story Structure, Pt. 1 of 2

If you’re a student of story structure, then you probably have a pretty good idea how each of the major plot beats affects your protagonist—and, indeed, how the protagonist in turn drives the plot beats. But what about the antagonist? What is the role of the antagonist in story structure?

If you’re a student of story structure, then you probably have a pretty good idea how each of the major plot beats affects your protagonist—and, indeed, how the protagonist in turn drives the plot beats. But what about the antagonist? What is the role of the antagonist in story structure?

Plot can be described in many ways, but one of the simplest and most useful is that of plot as conflict. And what creates that conflict? Although we often hear the word “conflict” and think of confrontations and altercations, what “conflict” really points to within story is simply the complications that arise when a character’s goal is met by obstacles. The character must re-calibrate—sometimes in a minor way, sometimes in a drastic way—and form a new plan to try to either maintain equilibrium or keep moving forward toward a specific goal.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

The beats of classic story structure present a roadmap of sorts through the rising and falling repeat cycles of a character’s intention, action, and reaction. That character is the protagonist, and we often speak of this character as “driving the plot.” It is the protagonist’s intention and subsequent ability to act upon that intention that frame the plot.

But what about the antagonist?

First, it’s important to remember not all stories will feature human antagonists or even specific antagonists. For example, a story’s main conflict might arise from the protagonist encountering multiple antagonistic proxies who represent the larger antagonistic force of a corrupt societal system, such as we find in stories like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street. That said, the antagonist’s function within the plot is usually most obvious in stories that feature a specific human antagonist whose personal intentions, actions, and reactions oppose the protagonist’s in such a way that they create obstacles for one another.

Especially in a tightly plotted story, the antagonist is every bit as important a driver of the story structure as is the protagonist. Therefore, there’s little wonder I’ve been receiving quite a few requests for a post that focuses on the antagonist’s role at each of the ten major plot beats.

Before diving into an overview of the antagonist’s impact upon each of the structural beats, I want offer a few clarifications:

1. There’s a difference between the antagonist’s structural role and the antagonist’s POV (point of view). Even if the antagonist does not have a POV within the story, he will still be an active force upon the structural beats (even if sometimes just implicitly).

2. The antagonist’s most important structural role is that of impacting the protagonist. From a characterization perspective, it is always important to create the antagonist as a person who is as fully dimensional as the protagonist. However from the perspective of plot dynamics, the antagonist functions primarily as a catalyst for the protagonist’s choices, actions, and development. Therefore, in most stories the best approach will be to view the antagonist less as an equal player within the story’s structure and more as a force that moves the protagonist through the structural arc. This a zoomed-out, mechanical perspective that can help you prevent the problem of an antagonist “taking over” the story. But if it feels too confining, just keep it in the back of your mind and don’t worry about it too much.

3. What follow are generalizations for the antagonist’s function at the major plot beats. Particularly in a story that is focused on a less personal version of the antagonist (more of an antagonistic force instead), the antagonistic effect upon the protagonist will often be less precise. Indeed the catalyst that complicates the protagonist’s desires and moves her forward to seek new solutions may well arise primarily from within the protagonist herself.

4. What I am referencing below is based on a story structure in which the protagonist follows a Positive-Change Arc—which I view as the foundational character arc, upon which all others are adapted. With an understanding of the other arcs (Flat and Negative), you can adjust the following to your needs.

The Antagonist’s Role in the First Half of a Story’s StructureBecause this turned into quite a lengthy discussion, I’ve split it into two posts. Today we will examine the antagonist’s role in the first half of a story’s structure, from the Hook through the Midpoint.

1. The Role of the Antagonist at the HookIn some stories, the antagonist will be present from the very beginning of the story. His goal will almost always predate the protagonist’s in some way, although he may or may not be aware of the protagonist’s potential threat to that goal. For that matter, the antagonist may not even be aware of the protagonist’s existence as yet. However, this does not necessarily mean the antagonist will personally show up in the story’s Hook or even in the First Act for that matter.

In a protagonist-centric story (and especially one that does not feature the antagonist’s POV), the Hook will usually focus on the protagonist. If the antagonist is not personally present, the force of antagonism within the story will be represented symbolically via the protagonist’s current state of existence. Thematically, the true antagonistic force in any story is the Lie the Protagonist Believes. One way or another, this Lie will come to be represented by the story’s specific antagonist. However, at the very beginning, it is often enough to simply dramatize the protagonist’s inner conflict, which will prepare a place for the antagonist’s role in her life later on.

Antagonist’s Plot Role in Hook: As a character at this stage in the story, the antagonist will be at work on his own plot goal, probably with no correlation to protagonist. If the goal does directly involve the protagonist, the antagonist may approach or initiate contact with the protagonist in this scene. Since the protagonist has not yet formed her own specific plot goal, she is unlikely to cause or suffer from direct conflict with the antagonist. Their contact, insofar as the protagonist (and perhaps the antagonist as well) knows, is so far incidental.

2. The Role of the Antagonist at the Inciting EventI like to describe the Inciting Event (or Call to Adventure) as the moment when the protagonist first “brushes” against the story’s main conflict. In some stories, this will mean the protagonist has now become aware of the antagonist as either a person or as someone with the potential to affect the protagonist’s life in ways the protagonist isn’t completely aligned with. In other stories, the protagonist’s Call to Adventure will have more to do with some sort of “invitation” into what will be the Adventure World of the Second Act. Although there can be direct opposition or threat from the antagonist at this point, the conflict is just as likely to arise more symbolically through the personal situations that are challenging the protagonist to accept this invitation.

Again, from a thematic perspective, the antagonistic force may be represented solely through the protagonist’s relationship to the Lie and the Truth. The protagonist’s Normal World is now becoming less functional (although this can be a sign of evolution rather than devolution, as in the case of a protagonist rising to a generally positive life challenge, such as getting a new job). The antagonist may be directly responsible for this growing dysfunction or may simply be symbolically fitted to step into a representation of that dysfunction when he does show up in the Second Act.

Antagonist’s Plot Role in Inciting Event: The antagonist character will also be facing an Inciting Event of sorts, although he may not realize it if he is, in fact, deep into his own plans. He, too, is “brushing” against this story’s main conflict, since the character who will become his primary opponent (i.e., the protagonist) is now on the brink of becoming an obstacle.

In some stories, the antagonist will be aware of the protagonist as a potential problem and will react in some way—which will probably lead to his “meeting his destiny on the road he takes to avoid it” by precipitating the events of the First Plot Point and causing the protagonist to become fully involved with him in the main conflict.

In other stories, the antagonist will remain mutually unaware of the protagonist as a threat (or perhaps even a person) and will interact with any conflict at the Inciting Event in the same thematic way as the protagonist.

3. The Role of the Antagonist at the First Plot PointIn most stories, if the protagonist and antagonist have not physically met each other yet, they will do so at the First Plot Point. At the very least, the events of the First Plot Point will directly propel them into opposing each other’s goals. In stories with “big bads,” the protagonist and antagonist may not physically meet until the Climax, but the protagonist will at least begin encountering significant antagonistic “proxies” who represent the main antagonist’s interests and work against the protagonist to achieve them. In a more personal story, this can signify the beginning of some sort of relationship between protagonist and antagonist—or at least an intensifying of their interaction.

As the turning point into the Adventure World of the Second Act’s main conflict, the First Plot Point signifies the moment at which the protagonist and antagonist become fully engaged with each other in pursuit of their mutually exclusive goals. In fact, one or the other of them may have the specific goal of stopping the other person in order to prevent a catastrophic obstacle to their overarching goal. A story in which the protagonist’s main goal is that of stopping the antagonist will be a story in which the protagonist is in a more reactive role. But it might also be that either the protagonist or the antagonist does not directly oppose the other’s goals until later in the story. For example, in a story about competitors, the bulk of the characters’ obstacles may be personal (learning to master the necessary skills, gaining confidence, etc.) until they finally end up in a direct confrontation at the end of the story.

Antagonist’s Plot Role in First Plot Point: The antagonist character will almost certainly make an appearance, by proxy if nothing else, at this point in the story. He will have become aware of the protagonist in some capacity. Even if he is not yet directly concerned with the protagonist’s ability to obstruct his goals, he will at least recognize the threat and move to protect himself from the protagonist in some way. The connection between the protagonist and the antagonist at this point will be definitive in that it causes a specific domino effect for both characters. Their encounter with each other at this point creates consequences—and their successive attempts to grapple with those consequences will engineer the entirety of the plot conflict to follow.

4. The Role of the Antagonist in the First Pinch PointEven in a heavily protagonist-centric story, the Pinch Points are designed to put the focus on the antagonistic force. This does not necessarily mean that the antagonist’s POV must be utilized here (especially if it wasn’t used previously). Nor does it mean that the antagonist must necessarily be present in the scene. What is most important at the Pinch Points is that the protagonist feels the “pinch” of the antagonist’s power and presence in the story. Specifically, the First Pinch Point should be a significant reminder to the protagonist of the antagonist’s ability to prevent her from reaching her goals. It is an emphasis of what the protagonist stands to lose and of the antagonist’s potential ability to take that thing away from the protagonist.

For the protagonist, the First Half of the Second Act (which the First Pinch Point splits in half) is a period of relative “reaction.” The protagonist does not yet fully understand the conflict or himself in it. Although this does not always directly correlate to the First Half of the Second Act being a period of “action” for the antagonist, it is an indication that the antagonist is usually at least a little farther ahead of the game than is the protagonist. He might not have much more figured out than the protagonist, but he is one step ahead of the game.

Antagonist’s Plot Role in First Pinch Point: The antagonist will probably make some sort of move against the protagonist here. At the very least, the antagonist will achieve an incidental victory at the protagonist’s expense. The antagonist, too, will have things at stake, and those may be referenced here but specifically in the context of the antagonist’s seemingly being able to protect them better than the protagonist is able to protect hers.

However, in achieving this minor victory, whether physical or psychological, the antagonist will also have sacrificed a little something. Specifically, he will have showed his hand to the protagonist, at least a little bit. The protagonist will gain information or insight about the antagonist. These new clues could be specifically about the antagonist’s plans within the conflict and/or they could be about the thematic context in which both characters are operating. Either way, the protagonist’s growing understanding of the antagonist will lead directly into the Moment of the Truth at the Midpoint.

5. The Role of the Antagonist in the MidpointThe Midpoint signals a major shift in the conflict. Up to this point, the protagonist will have been operating in a relative state of “reaction,” in which she did not fully grasp the thematic or practical nature of the conflict. But thanks in part to the insights she gained about the antagonist (and thus the conflict) at the previous beat of the First Pinch Point, she will encounter a full-blown revelation or Moment of Truth at the Midpoint. Although this revelation is not enough to yet allow the protagonist to fully overcome the antagonist and reach her goals, it does allow her to shift from a primarily reactive and defensive role into an increasingly active and offensive role.

By extension, this means the antagonist’s fortunes are shifting too. Not all stories will demand that the protagonist’s victory at the end of the story must come by way of the antagonist’s defeat. It’s always possible that the conflict resolves, instead, in a mutually satisfactory way with both characters more or less achieving their goals. In that case, the “antagonistic force” driving the conflict will be less a specific person and more a problematic mindset or mode of being for one or both characters.

However, in classic conflict, the protagonist’s shift into action at the Midpoint will indicate the antagonist’s shift in the opposite direction. Particularly if the antagonist is following a tragic arc, his experience will begin to devolve from here. In contrast to the protagonist’s Moment of Truth, the antagonist is more likely to double down on dysfunctional mindsets and tactics that will eventually prove themselves ineffective in the final outcome.

Antagonist’s Plot Role in the Midpoint: Usually, the protagonist and the antagonist will come together in a significant confrontation of some sort at the Midpoint. Often, the antagonist will be the one who seems to emerge victorious. However, because the Midpoint and its Moment of Truth function as a major wake-up call for the protagonist, the antagonist’s seeming victory is often the result of the antagonist’s making a big move that ends up showing the protagonist the holes in her approach. The antagonist may “win” the Midpoint as a result, but because he fails to walk away with the same insights as the protagonist, he will not subsequently have the capacity to grow and adapt in the second half of the story. He will likely leave the Midpoint from a place of power, but however potent it may still be, it will prove to be a dwindling reserve throughout the rest of the story.

***

And that takes care of the antagonist’s role in the first half of a story’s structure.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we will study the second half, starting with the Second Pinch Point all the way through the Resolution.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your antagonist’s role in your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Role of the Antagonist in Story Structure, Pt. 1 of 2 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 25, 2022

Do You Have to Write Every Day? 10 Pros and Cons

Should writers make it a habit to write every day? Is that the secret to success? Is that what distinguishes “real” writers?

Should writers make it a habit to write every day? Is that the secret to success? Is that what distinguishes “real” writers?

I used to think so. Often, when someone would ask me for my single recommendation for other writers, my go-to response was to reiterate some form of the advice from Peter de Vries that I’d had tacked above my desk for almost as long as I’d been writing:

I write when I’m inspired, and I see to it that I’m inspired at nine o’clock every morning.

I’ve dabbled in writing ever since I was a kid, but as soon as I got serious, around the time I finished high school, I started making writing a rock-solid part of my daily schedule. For many years, my writing time was firmly 4–6PM every afternoon, and Lord help anyone who interrupted that sacrosanct time. Usually, it was my favorite time of the day; other times, it was the worst, hardest, most agonizing time of the day. But thanks to that commitment to writing for two hours a day for at least five days a week, every week, I outlined, researched, wrote, edited, and published books that otherwise might never have seen the light of day.

Why You Should Write Every Day—And Why Maybe You Shouldn’tWhen I say “writing every day,” I don’t necessarily mean every day. What I do mean is creating and sticking with a specific and regular schedule that has you writing more days than not. I still absolutely believe this practice is a secret to success. Certainly, I feel it was instrumental for myself as a young writer building discipline, skill, and experience.

Writing at its best is fun and glorious and an incredible high. But writing is also hard—mind-numbingly, soul-killingly hard sometimes. This is so for many reasons, some of them mental and practical, others personal and emotional. Regardless, it ain’t for the faint of heart. And so sometimes our motivation to keep going through the hard patches needs a little practical support. Solid writing schedules are one of the best methods of support I’ve personally found. The more entrenched the habit becomes, the less resistance the writer finds to showing up at the page.

Plus, how else do you rack up the words? As NaNoWriMo-ers can attest, one of the single best ways to turn a few scribbled sentences into a solid mass of scenes and chapters is to write, write, write. Show up every day, sit there for a designated amount of time, and just go. And keep going. Hours turn into days turn into weeks turn into months—turn into completed first drafts.

In short, writing every day or thereabouts is an amazing practice for any writer to cultivate. This is because writing, just like anything else, is a practice that requires discipline and commitment.

That said, “writing every day” is not a hard and fast rule. In some cases, it won’t even be the best rule. In recent years, my creative journey has taken me into my own uncharted waters. I’ve spent more days not writing than writing, as I’ve explored the world on the other side of discipline and learned that creativity is not always something that can or should show up according to my or anyone else’s schedule.

Today, let’s take a look at what I see as five pros of writing every day, as well as five potential cons.

5 Pros of Making It a Habit to Write Every Day1. Consistency Promotes DisciplineWe sometimes refer to writing as a “discipline,” and for good reason. Although it may be borne on the wings of inspiration and powered by the fuel of enthusiasm, writing of any stripe and especially storytelling is a craft of incredible complexity. Learning, growing, and studying to understand how it all works requires enough discipline on its own. Actually putting that into experiential practice is an often herculean effort.

In short, if you intend to stick with writing past the first adrenaline rush of first love, it will require discipline. Consistency promotes that discipline. Making a commitment to show up at the desk every day is what allows writers to ground into the tenacity and focus required not just to keep going with a story but to turn it into something great.

2. Discipline Can Help Create FlowThe word “discipline” sounds harsh. But the cool thing is that the more disciplined we are in maintaining a consistent practice, the easier it actually becomes. My favorite thing about schedules and routines is that they have the potential, when approached mindfully, to transform the hardest parts of life into ritual and flow.

Now, you can’t force this. Just because your almighty willpower determines you’re going to hammer writing into your schedule at a certain time and make it work, does not necessarily mean it will. Early on in my commitment to my writing, I kept reading about how all these admirable writers did their best writing first thing in the morning. I decided to give it a try—even though I am not a morning person. It did not go well. In dread of having to bounce out of bed and immediately rocket my brain into the stratosphere of high-concept thinking, I hit the snooze button more than I ever had in my life. I didn’t get much writing done during those weeks. For my body and my life at that time, the flow just wasn’t there—and as a result, neither was the discipline.

As I’ve gotten older and better at heeding my own daily rhythms, I’ve also gotten better and better at hacking my daily schedule to optimize different tasks to different times of the day. These days, I do like writing in the mornings, but not first thing. Breakfast, yoga, and coffee have to happen first.

3. “Trains” Your Brain to Be Regularly CreativeIn correlation with the Peter de Vries quote at the beginning of the post, there’s a school of thought that suggests you can “train” your brain to be regularly creative at a certain time of the day. Basically, you can enhance your own natural flow by training yourself to take full advantage of it.

Whether or not this is actually true, my own personal experience has been that I feel far less inner resistance to work of any kind when I consistently show up for it at the same time every day. Certain other familiar “cues” can also help. For me, turning on background music and having a cup of coffee at hand help me ground my brain into focusing on “writing time.” Over the years, I’ve also played with different “warm-up” routines to help ease my mind and my energy into the right state. These days, I usually just do a quick grounding meditation/visualization to get out of my “chatter brain” and into my body.

4. Promises Steady ProductivityThe fastest way I know to rack up a word count is to work on it every day. In general, I’ve always preferred daily time goals (i.e., write two hours) rather than word count goals. I use word-count goals on the occasions when I’m feeling a lot of resistance (aka, spending most of my writing time daydreaming or checking email). But if I’m showing up at the desk regularly and really writing for my allotted time, that’s when I’m most likely to outstrip even the word-count goals. Day after day after day, that adds up fast—and before you know it, you’ve finished the book.

5. Cuts Through Both Excuses and RegretNo matter how much resistance we can sometimes feel toward doing the actual writing, we still tend to feel greater regret and even guilt when we don’t write on a regular basis. Setting up a schedule and sticking to it is one of the best ways to cut straight through the regret of not-writing.

The biggest hurdle to setting up a writing schedule is often our own excuses:

Oh, I just don’t have the time.

Or, My writing isn’t as important as this other thing.

Or, I keep getting interrupted whenever I want to write.

Sometimes we think other people are the ones who don’t respect our writing schedules, but something I learned early on was that others would only respect my writing schedules insofar as I respected them myself. Once that schedule is in place and you’re committed to upholding it, it becomes a shield against both the excuses and the resultant regret that can dog us when we feel unproductive.

5 Cons of Forcing Yourself to Write Every DaySo what about the dark side of writing every day? If it’s as great as the above makes it sound (and it is), then why is there even another side to the conversation?

1. Interrupts Natural Spontaneity—and Sometimes CreativityAs per the de Vries quote, you can train your brain to be creative on demand—to a certain extent. But at the end of the day, creativity and inspiration are linked to spontaneity. If discipline is Order, then I equate creativity with a certain amount of Chaos. Too much order, and you may succeed in eliminating all that scary chaos from your life—but the creativity goes with it.

The creation of and adherence to writing schedules will not, in themselves, unbalance order and creativity. But relying on them mindlessly will. The key is to use discipline as a tool to promote productivity while still keeping your finger on the pulse of your creativity’s needs.

It needs the day off? Honor that.

It wants to write on the weekends this time? Honor that.

It doesn’t like what you’re writing even though you’re determined to finish it? Maybe take a good hard look at that too.

2. Overrides Intuition and Instinct Regarding Personal Patterns and NeedsProbably no surprise that I like Order and err toward it, so it’s also probably no surprise that one of the greatest learning experiences of my adult years has been the discovery that life and its processes cannot be treated like an automated machine. This is directly true of writing, creativity, and art, but more deeply so because all of those things are rooted in the catalysts of life itself—such as intuition and instinct, out of which inspiration and creativity are birthed.

When the practice of writing every day is in flow with our natural rhythms, those rhythms are only enhanced. But if we’re superimposing discipline or willpower over the needs of those natural rhythms, we risk not just cutting ourselves off from them but damaging them.

3. Ignores the Need for Other Types of CreativityIf you’re a one-track-minded writer like me (and bless you if you’re not), it can be easy to forget that you are capable of many types of creativity. Indeed, your writing is just but one face of the creative force innate within you. As I realized during a long hiatus from writing, “I am not a Writer. I am someone who writes.”

Writing cannot happen in a vacuum. Sometimes the most responsible thing we can do for our writing is to not write. Take that scheduled writing time and do something else. Go out and experience life. Learn how to paint, take pictures, dance, decorate, sing. It’s all fodder for the muse. As Henry David Thoreau says in a quote I appreciate more with every passing year of my life:

4. Creates Cycles of Failure and GuiltHow vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live.

As mentioned above, writing schedules can be a wonderful tool for overcoming excuses and their resultant regret. But when they’re out of balance, they can also create cycles of failure and guilt. You were supposed to write today, but didn’t? Oops, now the inner critic gets to have a field day.

Examine your relationship to your writing schedules (or lack thereof). They should function as solid support systems to help you ease resistance and lack of motivation. They won’t always make these easy, and sticking with them will sometimes feel like a major inner battle. But you should feel good about them more times than not. If you’re using those schedules and structures to batter yourself into productivity and berate yourself when you fail, it’s time to reexamine what’s really going on.

5. Can Cause (and Intensify) BurnoutYou are the master of your schedules, your goals, and your commitments—not the other way around. You are the one choosing to write on a regular basis and enacting a schedule that will help you do so. If, however, you begin to feel that the schedule is becoming the master of you, something is awry. If you refuse to make adjustments and just keep plowing ahead, the result can be burnout. If you still keep going, the burnout gets worse. And as so many people in the last decade or so have discovered, burnout is not something that goes away overnight. It is a real phenomenon of mental, emotional, and physical depletion. Just as with poor nutrition, you can’t build back overnight what you’ve lost over a long period of time.

This doesn’t mean schedules are bad or dangerous. But writing is, first and foremost, a creative emergent. You can’t output and output and output without also scheduling time to refill the well.

***

So… should you write every day? Ultimately, that is a question only you can answer for yourself—based on a deep knowing of your own rhythms, needs, and goals. My shorthand answer would be: Sometimes you should write every day. Scheduling that kind of commitment into your life is a powerful tool, but as with any type of commitment, it comes with costs that must be carefully counted and paid.

The real metric at play here is simply that of balance. Are you balancing a conscious nurturing and care of your creativity against the level of exertion and output you are putting into writing? As long as the levels are commensurate, you’re unlikely to find that writing too much is ever a problem.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you write every day? Why or why not? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Do You Have to Write Every Day? 10 Pros and Cons appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 18, 2022

The 6 Challenges of Writing a Second Novel

Writing your first story is a special experience. It brings many difficulties and challenges, but it also tends to carry itself (and you) along with a sense of passion, fun, and discovery. When we finish it, we may think, Well, it can only get easier from here, right? But as many sophomore writers can attest, writing a second novel is often an entirely different experience. It may be easier in some ways than the first, but in others, it is often surprisingly and even bewilderingly more difficult.

Writing your first story is a special experience. It brings many difficulties and challenges, but it also tends to carry itself (and you) along with a sense of passion, fun, and discovery. When we finish it, we may think, Well, it can only get easier from here, right? But as many sophomore writers can attest, writing a second novel is often an entirely different experience. It may be easier in some ways than the first, but in others, it is often surprisingly and even bewilderingly more difficult.

In my own experience, it wasn’t so much my chronological second novel that was a different experience but my second published novel. Third and fourth novels are also their own unique experiences, but that second novel can be a significant hump for writers to get over, not merely in the terms of actually writing it and making sure it is as good or better than the first one, but perhaps even more particularly in the psychological aspects of the process.

6 Unique Challenges of Writing a Second NovelA while back, reader Eratta Sibetta wrote to me about this problem:

I am … an author (Soft in Flowers) and am now working on my second novel. My problem is that the Second Novel seems more daunting and much harder to write. I don’t get why this is? I have outlined all the chapters but it seems like the writing experience for my first novel is just so overwhelming and overpowering. I hardly think I will manage to achieve the same level of sharpness with this second book. Any advice would be appreciated. Thank you so much.

Behold the Dawn (Amazon affiliate link)

I don’t believe Eratta is anywhere close to being alone in finding the sophomore novel to be more difficult. I know this was certainly true for me in writing Behold the Dawn back in 2005 (and may I just say holy mackerel, I can’t believe it’s been that long!). Part of the struggle is, I think, what Eratta termed the “overwhelming and overpowering” experience of the first novel, in all the best ways. We tend to have lived a bit longer with the first novel—because, at that point, it’s the only one. We pour all the parts of ourselves into it. By the time we get to the second book, we don’t always feel as if we have as much to say. Plus, we’re usually more educated about the process at that point and, thus, sometimes find it more complicated (and perhaps even less fun).

For some of us, we may find one book was really all we wanted to write. But for most of us, the fact that we’re trying to write a second book at all is a sign this is a path upon which we must learn how to soldier on. Here are six of the challenges I see writers routinely facing when writing a second novel.

1. Your Audience Is No Longer TheoreticalThis was one of the “shockers” for me in moving from being an unpublished author to a published one. I had written four novels before publishing my first, so technically my “second” published book was in fact my sixth. But the sophomore blues still hit me pretty hard, and one of the biggest shifts was that, suddenly, I was no longer writing into the ether. I was writing for people who would respond, have opinions, leave reviews, and take personal possession of my characters. My writing would be weighed and measured, and I would be accountable for what I said to far more people than just myself. However much we may long for just that, it’s still a lot of pressure and a totally different environment into which to be pouring our hearts onto the page.

2. You Gave “Everything” to the First BookWhen write the first book, it’s the only one—and we give it everything we’ve got. It gets our best ideas (maybe even all of our ideas at the time), our rawest emotional power, and the first rush of all our artistic enthusiasm. We leave it all on the field. What does that leave for Book #2 that won’t feel second-best or rehashed?

Last Night (affiliate link)

I have always been struck by the perspective of Keira Knightley’s author character in the movie Last Night, in which she discusses with an old boyfriend her writer’s block with her second book:

Alex: So why aren’t you writing?

Joanna: I am writing.

Alex: No. Why aren’t you writing? … Your book, Joanna.

Joanna: My editor says that I just need to get over my doubts.

Alex: What do you doubt?

Joanna: Everything, Alex. I go to write and every word, every thought, every choice that I make leads to another and I doubt every single one I make. It wasn’t like this last time. You live with your first book all your life. It’s sort of—it comes out on its own. After that, though, it’s different. You can suddenly write anything, and you second-guess everything.

3. Your Relationship to the Inspiration May Be DifferentWhy did you decide to write the first book? Every writer has a different reason. But for many of us it was because some burst of inspiration struck us—perhaps something that had been building inside of us for a long time. Sometimes lightning strikes twice, and we get that same experience with the second book. But often we finish the first book, and even if we have an inkling of what we want to write about next, we don’t necessarily feel it in the same way. Certainly, the incubation period may be shortened. My early story ideas were ones I lived with for years before writing them; later ones inevitably got (and, frankly, needed) much less time.

4. You Know More Now (aka, You May Now “Know You Don’t Know”)Another major hang-up for many people in writing a second novel is that suddenly they know way more about writing than they did before. One of the reasons I think I didn’t have “sophomore novel syndrome” until writing what was, in fact, my sixth book was that I wrote most of those books when I was too young and unaware to realize there was a technique to writing. Once I started learning about “how to write,” everything changed. My writing got a lot better, but it also got a lot harder. The irony is that, in the early days of your writing education, the first thing you know is often that you don’t know. In short, you’re now responsible for a greater deal of knowledge than you were before.

5. You Feel Pressured to “Live Up” to Being an Author NowWhen you wrote your first book you had absolutely nothing to live up to. After writing it, a lot changes. Particularly if you published that book, you now have an audience to a please, a story already out there that you need to equal or perhaps surpass, perhaps contracts to fulfill, perhaps even bills to pay. At its simplest, the biggest different between you as a writer of your first book and you as a writer of your second book is that now you “have written.” From this point on, you will always be someone who “wrote a book.” In some ways, that brings the confidence of experience. But especially in the second go-round, it can also feel like a lot to live up to.

6. You’re Tired, Maybe Even Burned OutWriting a book is no mean feat. Particularly if you were under any kind of deadline on your first book, you may well have spent months or even years hammering your passion onto the page. Much of that will have been exhilarating, but it can also be exhausting. If you pushed hard, you may even be feeling some burnout. If you dive straight into Book #2, part of the struggle may simply be that you’re tired. A little break to refurbish your energy and inspiration can do wonders for resetting.

7 Ideas for How to Make Writing a Second Novel EasierChallenges or not, you’re probably here reading this because you are going to finish this second book and that’s that. Sometimes just recognizing why something is hard can go to surprising lengths in easing some of the pressure. But if you find you are struggling with your second story (or any story, really), the following seven tips may prove helpful.

1. Tell Yourself No One Ever Has to Read ItThis was the magic pill for me when I was writing what would be my second published novel. Although, of course, my desire was to publish the book eventually, I knew the most important thing was just to finish it—for my own sake—whether or not I ever published it. I also knew I’d have an easier time writing the story I wanted to write, with honesty and vulnerability, if that small scared part of my writing brain felt safe. So I promised myself (and meant it) that no one would read this book if I didn’t want them to. I wrote it, it turned out better than my first published book, and of course I did publish it. But in cutting myself some slack early on, I was able to recapture some of the freedom I’d experienced in writing the earlier books that had been just for me.

2. Consciously List and Address Fears

Conquering Writer’s Block and Summoning Inspiration (affiliate link)

Writer’s block is often fear-driven. Especially if you’re now swimming in the brave new waters of being a published author, you may find there is a lot out there to overwhelm you. Write a list of anything that is causing you anxiety. Give the scared or shaming voice in your head a chance to have its say.

Maybe you’re afraid that you just got lucky with that first book and that you’ve “lost” whatever talent you had. Or maybe you’re afraid readers will dislike certain characters or find your research wanting. Maybe you’re afraid you won’t make your deadline or fulfill your publishing contract. Maybe you’re afraid you’re wasting your time and that no one will ever buy this book. Whatever it is, write it down.

Sometimes just the act of consciously acknowledging the buzzy cloud of anxiety in the backs of our brains is enough. But you can also go the extra step and burn or bury the paper as a symbol to your subconscious that these thoughts no longer have power in your life.

3. Consciously List and Address Actual ProblemsAnxiety is one thing; actual problems are another. As part of the previous list or as a new one altogether, write down anything and everything that is bothering you about the actual writing and story of this book. Are your worries about readers disliking a certain character valid? Listen to your gut, not your fears (the most trustworthy intuition is neutral, without emotion). Then put on your writer’s cap and brainstorm ways to actually address the issues in your story.

It’s important not to flail away at a story, editing and editing it, simply because you having a nagging feeling that something might be wrong with it. Rather, use what you learned in writing the first book, and drill down to name your own true feelings and instincts about any problems—and how you can constructively fix them.