K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 17

October 10, 2022

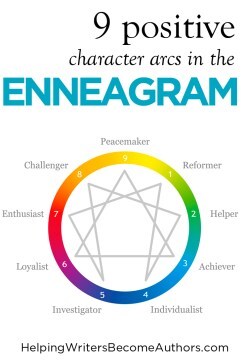

9 Positive Character Arcs in the Enneagram

Character arcs aren’t just the stuff of good fiction. They’re also the essence of all personal growth and transformation. Little wonder, then, that some of the best shortcuts writers can find for identifying the most powerful character-arc options are those found in personal development tools such as the Enneagram.

Character arcs aren’t just the stuff of good fiction. They’re also the essence of all personal growth and transformation. Little wonder, then, that some of the best shortcuts writers can find for identifying the most powerful character-arc options are those found in personal development tools such as the Enneagram.

These days, most of us are familiar with the Enneagram as a popular personality theory, which focuses on an interconnected circle of nine possible types.

The Road Back to You by Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile (affiliate link)

I like the way Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile describe the Enneagram in their excellent beginners’ book The Road Back to You:

The Enneagram teaches that there are nine different personality styles in the world, one of which we naturally gravitate toward and adopt in childhood to cope and feel safe. Each type or number has a distinct way of seeing the world and an underlying motivation that powerfully influences how that type thinks, feels, and behaves….

For some people, just being able to recognize themselves in one of the nine types is fun, interesting, and enough to satisfy their curiosity. But the Enneagram also offers a deep rabbit hole for those interested in its many complex layers of theory. An age-old tradition, it comes down to us as not just a personality-typing system but as an “ego-transcendence tool.”

In short, it’s all about transformation. I’ve been studying the Enneagram and using it as a cornerstone of my own personal growth for almost five years now, and I’m not exaggerating when I say its insights have been a major role player in turning my life inside-out and upside-down, in all the best ways. If you’re interested in doing the hard and sometimes scary work of looking deep into your own shadows and rediscovering all the good stuff you’ve lost down there, the Enneagram is an incomparable roadmap for the journey. It is simple on the surface, but grows in profundity the deeper you go. You can take it at your own pace and reap rewards at any level.

And the other thing the Enneagram is great at?

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Helping those of us who are writers understand the mechanics of amazing character arcs. Thanks to the polarities and dichotomies revealed in every one of the nine types, the Enneagram also offers solid shortcuts for finding the Lies and Truths that are driving your characters through your stories.

What Is the Enneagram?Experts will tell you that your Enneagram number is not who you are; it’s who you’re not.

At its simplest, the Enneagram is a map of nine possible ways in which a child’s psyche learns to interact with the external world. These nine methods of survival are highly sophisticated and effective. However, they are limited. In “choosing” to be one type, we necessarily cut off the eight other parts of ourselves. To one degree or another, this creates imbalances in each type, which in turn can lead to dysfunction, confusion, and even suffering.

The Enneagram, then, helps us see which number we’ve identified with, so we can learn how to grow past this shallow ego identity and into a fuller realization of our whole selves. Sounds like a character arc to me!

9 Positive Character Arcs in the Enneagram

The Wisdom of the Enneagram by Don Richard Riso and Russ Hudson (affiliate link)

Today, I want to quickly explore nine positive character arcs in the Enneagram personality system. The information I’m sharing here is drawn from my own experience and study, but most specifically from the work of Don Richard Riso and Russ Hudson. Although I appreciate the incredible depth and complexity they bring to their teachings on the Enneagram, I also like the simplicity of the words they choose when comparing certain aspects of the various types. The suggested Lie the Character Believes as shown for each type and some of the other phrasings are quoted from their book The Wisdom of the Enneagram.

Both this book and their earlier work Personality Types (which I mentioned in my post: “5 Ways to Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters“) are filled with charts, graphs, and scannable type comparisons that are rich fodder for any novelist or character-arc enthusiast. A brief perusal of either book makes it easy to start picking out possible Lies, Truths, Needs, Wants, and backstory Ghosts for your characters—which you can then personalize for your story.

If you’re interested in further study of the Enneagram, I also recommend The Complete Enneagram by Beatrice Chestnut and the podcasts “Enneagram 2.0” by Beatrice Chestnut and Uranio Paes and “The Enneagram Journey” by Suzanne Stabile.

1. The Reformer’s Arc: Resentment to IntegrityCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to make mistakes.”

Also sometimes called the Perfectionist, Type Ones at their best represent responsibility and idealism. At their worst, they come across as judgmental and obsessive. Their core vice (or “passion“) is an under-the-surface resentment, born out of their frustration that their attempts to make a better world are stymied and/or unappreciated.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by an unconscious fear of their own badness or defectiveness. Their arc challenges them to come into true integrity by claiming all parts of themselves, recognizing the good not just in themselves but in the world around them. They offer the gift of being able to improve the world for themselves and others. When done from a place of love, this enables them to find a higher purpose.

Type One: Mr. Darcy in Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice (all character examples typed by Charity Bishop of the great personality Tumblr Funky MBTI Fiction)

2. The Helper’s Arc: Pride to Unconditional LoveCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to have your own needs.”

Also sometimes called the Caretaker, Type Twos at their best represent kindness and generosity. At their worst, they come across as intrusive and needy. Their core vice is a sense of pride that particularly focuses on their need to believe in their own virtue, usually demonstrated by showing compassion or aid to others at the expense of their own needs.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by a probably unconscious fear that they are not worthy of being loved—and therefore must earn it through their good deeds to others. Their arc challenges them to grow beyond just a pretense of love and into a truly unconditional love that, by also encompassing their own needs, allows them to more fully and authentically serve others. When healthy, they offer the gift of nurturing and caring for the world around them.

Type Two: Isobel Crawley from Downton Abbey

3. The Achiever’s Arc: Vanity to AuthenticityCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to have your own feelings and identity.”

Also sometimes called the Role Model, Type Threes at their best represent productivity and adaptability. At their worse, they come across as image-conscious and emotionally out of touch. Their core vice is a misdirected vanity, which they try to hide behind the mask of their accomplishments—a sort of self-deceit designed to cover up their inner sense of inadequacy.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by an unconscious fear that their only value lies in their external achievements. Their arc challenges them to grow beyond their over-identification with how they are viewed by others and into a deeply realized authenticity. When healthy, they offer the true gift of bearing witness to the intrinsic value in themselves and others.

Type Three: Philip Carlisle in The Greatest Showman

4. The Individualist’s Arc: Envy to EquanimityCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to be too functional or too happy.”

Also sometimes called the Romantic, Type Fours at their best represent creativity and idealism. At their worst, they come across as self-absorbed and unrealistic. Their core vice is a painful envy, born out of their sense that they are somehow more deficient than other people or that something essential is missing from their lives.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by an unconscious fear that they somehow lack personal identity or significance. Their arc challenges them to accept the beauty and perfection inherent within themselves, so they can recognize their own worth and move into a genuine sense of self-esteem. When healthy, they offer the gift of being able to release the past and live fully in the present.

Type Four: Luna Lovegood in the Harry Potter series

5. The Investigator’s Arc: Avarice to Non-AttachmentCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to be comfortable in the world.”

Also sometimes called the Observer, Type Fives at their best represent perceptiveness and self-reliance. At their worst, they come across as cynical and emotionally unavailable. Arguably the most introverted of the types, Fives’ core vice of “avarice” refers to a “lack mentality” that urges them to conserve their inner resources against a world that seems inclined to demand too much from them.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by an unconscious fear that, at their core, they are incompetent or incapable of meeting the demands of others. Their arc challenges them to grow into the surrender and serenity of non-attachment—an acceptance that each moment offers enough to meet their needs. When healthy, they offer the gift of being able to observe both themselves and others without judgment or expectations.

Type Five: Alan Grant in Jurassic Park

6. The Loyalist’s Arc: Anxiety to Inner PeaceCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to trust yourself.”

Also sometimes called the Traditionalist, Type Sixes at their best represent loyalty and responsibility. At their worst, they come across as reactive and fearful. Their core vice is often talked about as fear, but is really more of a never-ending simmer of often nameless anxiety.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by the (actually pretty conscious) fear of being without support or guidance in a dangerous and untrustworthy world. Their arc challenges them to grow into, first, a powerful trust in their own reliability and, second, into a surrendered belief in the inherent goodness of life. When healthy, they offer the gift of true courage and capability in handling life’s challenges.

Type Six: Rapunzel in Tangled

7. The Enthusiast’s Arc: Gluttony to JoyCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to depend on anyone for anything.”

Also sometimes called the Energizer, Type Sevens at their best represent optimism and fun. At their worst, they come across as impulsive and undisciplined. Their core vice of “gluttony” refers to an insatiable desire to immerse themselves in experience after experience as a way of distracting themselves from inner fears and pain.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by unconscious fears of being deprived, abandoned, or trapped. Their arc challenges them to grow beyond a pursuit of shallow distraction into an embodied joy. When healthy, they offer the gift of sharing this joyful celebration of existence with everyone around them.

Type Seven: Jonathan Strange in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell

8. The Challenger’s Arc: Intensity to InnocenceCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to be vulnerable or trust anyone.”

Also sometimes called the Leader, Type Eights at their best represent boldness and decisiveness. At their worst, they come across as domineering and combative. Their core vice is a lust to experience intensity in every moment of their lives, as a way to escape their own fears and deny their own weaknesses.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by the unconscious fear that they might experience helplessness under the the control or betrayal of someone else. Their arc challenges them to return to the trusting innocence of their lost childhoods. When healthy, they offer the gift of being able to stand up for not just themselves but for all those who need a protector.

Type Eight: Leia Organa in Star Wars

9. The Peacemaker’s Arc: Resignation to Right ActionCore Lie the Character Believes: “It’s not okay to assert yourself.”

Also sometimes called the Healer, Type Nines at their best represent tranquility and reliability. At their worst, they come across as passive-aggressive and apathetic. Their core vice is a resignation to their lot, a desire to remove themselves from the struggle of life, out of a belief that they cannot truly impact it for the good of themselves or others.

The deep-seated Lie of their personality is fueled by the unconscious fear that in taking certain stands (both internally and externally), they risk feeling disconnected and adrift from others. Their arc challenges them to rise into a discernment of and ability to take “right action” on behalf of themselves and others. When healthy, they offer the gift of bringing peace and healing to the world around them.

Type Nine: Edward Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility

***

There you have it! Nine Positive Change Arcs for your characters (or yourself)! What I’ve shared here barely scratches the surface of Enneagram wisdom and teachings about the nine types. If you’re interested in pursuing the journey further, I highly recommend checking out some of the resources mentioned above.

And what if your character is (sadly) on a downward spiral? Glad you asked, because next week, we’ll be taking a look at nine possible negative character arcs you can find in the Enneagram.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever explored character arcs in the Enneagram (or any other personal-development tool)? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 9 Positive Character Arcs in the Enneagram appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 3, 2022

How to Pull Off a Plot Twist

Note: This is the last week in my vacation from the usual post and podcast. Today, I am sharing another fast tip that I hope you will enjoy and find useful! I will be back next week with a brand new two-part series about how you can use the Enneagram to strengthen your story’s character arcs.

Note: This is the last week in my vacation from the usual post and podcast. Today, I am sharing another fast tip that I hope you will enjoy and find useful! I will be back next week with a brand new two-part series about how you can use the Enneagram to strengthen your story’s character arcs.

Readers love a well done plot twist. They like to have the rug skillfully pulled out from under their feet at the last minute in a way that changes everything they understood about the story, while simultaneously making them see everything with perfect clarity. One of my favorite romance authors, Kristen Heitzmann, gives us some clues in her romantic suspense novel Indivisible about how to successfully misdirect readers. (If you haven’t read the book, be warned: Spoilers ahead!)

Indivisible by Kristen Heitzmann (affiliate link)

In this book, her plot twist revolves around the revelation that the apparently alive twin sister of a POV character has, in fact, been dead for many years and only exists in the narrator’s delusions. Heitzmann does a particularly good job of building up to this revelation. How does she do this?

To begin with, she doesn’t add details to make readers believe what she wants, so much as she leaves out details. She never lies to readers or overtly twists the truth to make them believe the character is alive.

Rather, she allows the narration of the deluded character herself to give the impression that the sister is still alive—and then never does anything to contradict readers’ belief. When the trap is sprung in the ending, readers immediately see how all the puzzle pieces fall into place—without feeling as if the author lied to them or manipulated them.

When considering whether a plot twist is right for your story, keep two caveats in mind.

1. You can’t fool all the people all the time.No matter how skillful your plot twist, some readers will see through it and possibly be annoyed that the book was built on a twist they realized too early.

2. Poorly constructed plot twists or those inserted just for cheap thrills are gimmicks that will turn readers off instead of endearing them.The plot twist must be organic to your story, but it shouldn’t be the point of your story. Make sure your tale has some enduring value beyond the twist itself. The goal should to be getting readers to revisit the story even after they know how it ends.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think is the key to writing a plot twist that satisfies readers? Tell me in the comments!___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Pull Off a Plot Twist appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 26, 2022

How to Use Chapter Cliffhangers in Your Fiction

Note: I’m taking a two-week break from the usual post and podcast, so am sharing this shortie instead. Enjoy!

Note: I’m taking a two-week break from the usual post and podcast, so am sharing this shortie instead. Enjoy!

We all want to write stories that keep readers turning pages into the wee hours of the morning. We want readers to reach the end of a chapter and be gripped with an undeniable need to keep reading. We want to them take a look at the clock and promise themselves, Just one more chapter—and then have that “one more” morph into half the book.

We’ve all read books like this. So what’s the secret to writing one?

In a word: chapter cliffhangers.

How you craft the closing paragraph of your chapters has a huge effect on whether or not readers will decide to read “one more chapter”—or stick their bookmarks between the pages and leave your characters in limbo until tomorrow night. You must give them a reason to keep reading: a question that must be answered, a character that must be saved from a dire predicament, or a surge of forward motion in the plot progression.

The Well of Ascension by Brandon Sanderson (affiliate link)

Fantasy powerhouse Brandon Sanderson did this admirably in The Well of Ascension, the second book in his beloved Mistborn series (and, really, all his books). This heavyweight 800-page novel reads more like a fast 350 pages thanks, in large part, to chapter breaks that don’t feel like breaks at all… they’re more like accelerators.

Sanderson ends every one of his chapters with a hook that draws readers directly into the next chapter. He never ties off all the loose ends, and he always gives a hint of something exciting, intriguing, or unexpected around the corner in the subsequent scene.

Although some of his chapters do indeed end with the characters in mortal danger (in essence, hanging off a cliff), he understands this extremism isn’t always necessary and that, indeed, it would grow monotonous and begin to feel gimmicky to readers if overused.

For example, the first chapter ends with this in medias res action beat:

At that moment, a burst of coins shot through the mists, spraying toward Vin.

But Chapter 4 teases readers with a subtler hook:

“Come,” Sazed said, turning toward the village. “There are other things—more practical things—that I can teach you.”

To achieve the same effect in your own fiction, follow his example of masterfully varying the intensity of the hooks, while always promising readers something worthwhile in the next chapter—and then fulfilling that promise.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How have you used chapter cliffhangers on your fiction? Tell me in the comments!___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Use Chapter Cliffhangers in Your Fiction appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 19, 2022

What Do You Want Me to Write About?

Hey, everybody!

Hey, everybody!

I can’t believe we’re almost into the final quarter of 2022. As I’m starting to think about what I want to share on the blog next year, I thought I’d take the opportunity to ask you—since many of my best post ideas come from questions here in the Wordplayer community.

So…

What would you like me to write about?

Is there a writing subject that’s really got your interest right now?

How about a gnawing question you just can’t figure out?

In short, as I start gearing up for a new round of posts and podcast episodes, I’d like to make sure I’m serving your needs as best I can.

Leave me a comment and tell me what post you’d most like me to write for you. (If you phrase your request as a question, I may be able to quote you if I end up using it as inspiration, unless of course you specify that you’d rather I not do so.)

As always, thank you all so much for your engagement here with me and your passion for telling stories to a world that needs them!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What writing topic or question would you like me to talk about in future posts? Tell me in the comments!The post What Do You Want Me to Write About? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 12, 2022

Conflict + Choices = Character Agency

Note From KMW: Character agency is a hot topic these days, but truly it was always an important topic for writers. Why? Because a character (particularly a protagonist) with no agency is a character who isn’t likely to be very interesting. More than that, a character with little to no agency won’t be able to generate and/or respond to conflict. The result? The plot grinds to a halt.

Note From KMW: Character agency is a hot topic these days, but truly it was always an important topic for writers. Why? Because a character (particularly a protagonist) with no agency is a character who isn’t likely to be very interesting. More than that, a character with little to no agency won’t be able to generate and/or respond to conflict. The result? The plot grinds to a halt.

So how do you create characters and plots in which agency is baked right into the mix?

I’m glad you asked, because today I am happy to once again be hosting the lovely Becca Puglisi (of Writers Helping Writers) with a quick and easy formula for adding character agency to your story’s recipe. Keep reading: she offers four specific tips for adding, enhancing, and troubleshooting this vital element in your fiction.

***

Consider, if you will, a story about a woman who wants to gain esteem by winning an important legal case. Things are going along fine until she gets fired from the firm for her unusual fact-finding practices. She ends up being forgiven and rehired, but her babysitter bails, leaving her with no one to watch her kids. Then, at a critical point in the case, she gets so sick, she’s unable to keep working.

It could be an interesting plotline. Obstacles are blocking her from her goal, which is a good thing. But it falls flat because the character isn’t driving the story; the events are. Instead of making things happen, she’s just reacting to what’s thrown at her. She has no control over her destiny.

But look what happens when we rewrite the story with her in charge:

To make ends meet, Erin pesters her lawyer to hire her as a secretary. In the scope of her work, she discovers information in a seemingly innocuous file that doesn’t make sense. She secures permission to do a little digging, but there’s a miscommunication with the boss, who doesn’t expect her to spend a full week off-site doing research. He fires her before realizing that her fact-gathering revealed a huge human-rights violation—something Erin discovered when she took the initiative to investigate. So she’s reinstated. But then she loses her babysitter. This doesn’t set her back for long because she quickly finds a replacement in the guy next door (taking a step toward an important romantic relationship in her story). The case progresses to a critical point, at which time she falls deathly ill. But she soldiers on and goes to the office anyway, where she learns that decisions about her case have been made expressly behind her back…

The movie Erin Brockovich shows how powerful character agency can be given even to characters who don’t start out with much power.

Both summaries tell Erin Brockovich’s story, but the second one puts her behind the wheel. Each time she’s hit with a problem or roadblock, she makes a choice or acts in a way that pushes the story forward and inches her closer to her goal. This is the essence of character agency.

4 Ways to Enhance Character Agency in Your FictionCharacter agency isn’t a simple element to define, but at its most basic, it is the character driving story events through choices. When conflict happens, she doesn’t just sit there; she takes action. She chooses, and by doing so, determines what comes next.

Agency is important because, without it, it’s not really the character’s story. She may be in it, but if she’s not making things happen, accelerating events, and actively working toward her goal, what’s the point? If nothing the character does changes the outcome of the story, why is she in it?

The fact is that you don’t see many successful tales about protagonists with no agency. Most of the time, they just don’t resonate with readers because the character is a bystander in their own life. To write a compelling story and inspirational protagonist, put the hero in the driver’s seat so they can navigate the roadblocks and reach the finish line in their own unique way.

How do we do that, exactly?

1. Use Choices

The Conflict Thesaurus, Vol. 1 by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi (affiliate link)

One of the things we discuss in the first volume of The Conflict Thesaurus is the 3C cycle of:

ConflictChoicesConsequencesIn a nutshell, when conflict is introduced for a character, a choice must be made, and consequences will follow. This cycle is repeated many times throughout a story. Sometimes characters make choices that propel them toward their goals. Other times, their decisions pull them in the wrong direction. Either way, they have a say in what’s happening to them.

The conflict scenarios you introduce, and the choices that stem from them, are key to giving your characters agency in their story. Plan with this in mind and use conflict with purpose to encourage (or discourage) decisions that will get the character where they need to go.

2. Include a Goal in Every SceneChange doesn’t happen overnight. Success for your protagonist consists of many baby steps that get them to that final objective. This is why a story has scenes, and every scene needs a goal of its own.

Let’s say your protagonist is a cop with questionable methods whose overall objective is to rescue someone from a captor. At the start, he won’t know much, but every scene will include a goal that will get him closer to finding the captive. The objective of one scene might be to speak to the neighbor who last saw the victim. Another goal could be to interview a key suspect. He might need to win over a supervisor who doesn’t think he can handle the case.

If your character lacks agency, it could be because your scene-level goals aren’t defined enough. If he doesn’t know what he’s working toward, then his choices won’t matter. He might make decisions, but they’re going to be all over the map because he lacks direction. A protagonist who wanders aimlessly doesn’t have agency. Know your character’s goal in each scene.

3. Add Conflict to Every SceneOnce you know your character’s scene goal and you’re sure it belongs on the roadmap to the overall objective, add conflict that makes it harder to get there. Conflict makes things interesting, yes, but it also requires a response.

In our scene where the cop needs to interview a suspect, maybe the guy asks for a lawyer, which will make it difficult to get answers. How does the protagonist react—does he try to convince the suspect he doesn’t need legal representation? Use force to coerce him? Bug the guy’s briefcase so he can get the information (illegally) without an interview?

Every scene needs conflict because it provides opportunities for the character to go one direction or another. The decision to use physical force or blackmail could get the cop his answers, but if he’s trying to turn over a new leaf and act ethically, it could push him farther from that internal objective—something he’ll have to address in later scenes. However he responds to the conflicts that arise, he’s choosing, and those choices will help determine his fate.

4. Make Sure Your Character Does the ChoosingConflict alone won’t give your character agency. If the events in their life don’t give them a choice—if they are forced to adopt a certain way of thinking or comply to a course of action—then someone else is running the show. If our cop is essentially a puppet who was given the case because it’s political and his supervisors want things to go a certain way, they will be dictating his actions. Whatever conflict comes along will already be decided because he’s going to do what his boss says. “Yes” men and followers don’t typically make the best protagonists, so create a way for a pinned-down character to resist and go rogue.

You can get the same problem in stories with supernatural elements. Monsters, magic-wielders, demigods, and the like will have an edge over mere mortals. Or consider Mother Nature—how can characters overpower an earthquake or tsunami? They can’t.

Basically, any antagonist with an inordinate amount of power or leverage has the potential to steal your character’s agency. Keep that in mind and find ways to make your protagonist the decision-maker.

A good example of this is found in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. On their trip to destroy Sauron’s ring, the fellowship has to get over a mountain. But Saruman sends a supernatural storm that makes it impossible for them to cross. Instead of shrugging their shoulders and plodding back down to safe ground, they call a meeting in the middle of the blizzard. Caradhras is a no-go, so what route will they take next? Only after Frodo has made the decision to go through Moria do they leave the mountain.

Even in story situations where the character’s choices are limited, such as the Fellowship of the Ring getting trapped on a mountain in a blizzard, can be enhanced with a thoughtful use of character agency.

This could easily have been a situation where the characters allowed story events to displace them and move them around. But Tolkien didn’t let that happen. He gave them the opportunity to choose. That choice had consequences, as we see in later chapters, but it also allowed the characters to set their own course.

This is how you build character agency: by making authorial choices that provide choices for the protagonist—the results of which will impact the story. Simple? Yes. Easy? No, sadly. But if you plan and/or revise with this in mind, it will become second nature. And you’re sure to start your character on a path that puts them in charge of their own destiny and story.

Want to Take Your Conflict Further?The Conflict Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Obstacles, Adversaries, and Inner Struggles (Volume 1 & Volume 2) explores a whopping 225 conflict scenarios that force your character to navigate relationship issues, power struggles, lost advantages, dangers and threats, moral dilemmas, failures and mistakes, and much more!

The post Conflict + Choices = Character Agency appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 5, 2022

Do You Need Personal Experience to Write About Something?

We writers like think of ourselves as metaphoric magicians—sitting at our desks, spinning worlds out of nothing but words and imagination. Pour a little research into the recipe, and our alchemy is complete. Yet an ongoing question among writers is the evergreen quandary about whether or not we must “write what we know.” In short, do you need personal experience to write about something?

We writers like think of ourselves as metaphoric magicians—sitting at our desks, spinning worlds out of nothing but words and imagination. Pour a little research into the recipe, and our alchemy is complete. Yet an ongoing question among writers is the evergreen quandary about whether or not we must “write what we know.” In short, do you need personal experience to write about something?

In sorting through my email archives last week, I came upon an email I’d forgotten I’d saved, from a young writer asking this very question. He pointed to such classical giants as Hemingway, Steinbeck, and Orwell, who all experienced firsthand what they famously fictionalized—hefty topics such as war, migrant workers, and communism. The email asked, with plainspoken authenticity:

How does someone like me write something that has substance when I haven’t experienced much of the real world?

The standard answer to “must you write what you know?” is a qualified “no.” Sooner or later, we all must write what we don’t know. Hemingway, Steinbeck, and Orwell did it, and so must you and I. We are writing fiction after all. By definition, we’re making it up.

Depending on the story, we may end up writing about things we can’t experience. For instance, if you’re writing about a character who is dying, that isn’t something you can experience yourself and live to the tell the tale. For that matter, any time you write a character who is anything other than a carbon copy of your genetic and psychological makeup (so, pretty much every character you write), you’re going be writing something outside your experience—something you don’t know.

There is, however, another side to the argument. After all, could Hemingway, Steinbeck, Orwell, and so many others have written with such memorable power and authenticity with no personal experience to back them up? Of course we will never know. But I doubt it. We feel an undeniable edge—a truth—to stories that are written out of an author’s own lived experience.

As a young writer, I always squirmed under the harsh light of Henry David Thoreau’s declaration:

How vain it is to sit down to write when you have not stood up to live.

Mostly, I squirmed because I wasn’t yet ready to admit how sheltered and inexperienced I was, how little of the world I had seen, how much I had yet to learn. Stories were my window to the world; they were my experience. From that place of inexperience, I wrote stories I’m still proud of, but as I’ve gotten older, Thoreau’s words have come into focus for me. The stories I may write in the future have the potential to be so much more powerful than those I wrote when I was younger, thanks to the widening vista of life experiences.

In short, even though we can (and will) write stories based more on imagination and empathy than lived experience, this hardly negates the tremendous validity of, in fact, writing what we know. This doesn’t mean any one of us should discount the importance of whatever life experiences we’ve already lived or hold back on writing the stories that are ready to be written right now. What it does mean is that, particularly as writers, we should be willing to fling ourselves wide open to the banquet life sets before us.

Does this mean you have to go to war if you’re going to write about it? Visit every story setting in person? Test-drive all your characters’ bad habits? Exemplify all of their virtues?

Of course not. Especially if you write speculative fiction such as fantasy or sci-fi, that whole line of questioning grows quickly ridiculous.

What “write what you know” does mean, in my view, is that we need to cultivate awareness around whatever experiences we do have and to take them seriously in translating them into fiction that rings with authenticity.

4 Different Ways to Write What You KnowThe advice to “write what you know” always seems to receive a fair amount of pushback. I think this is for the simple reason that its phrasing is too generic. What does it even mean? After all, I know all about Mary, Queen of Scots. That doesn’t mean I know her. I know lots of things about Hogwarts. Doesn’t mean I’ve been there.

These days so much of what we experience is vicarious, thanks to other people’s stories on the news, social media, and of course in books and movies. As a result, we can find a great deal of gray area between our “knowledge” of things and our “experience” of things. For instance, we can experience something viscerally by watching it in a movie or on the news (even to the point of traumatizing ourselves). However, even though this is a legitimate experience, it is not the same as a lived experience.

Both can be fodder for strong and authentic stories, but I believe it is important to recognize the different flavors brought to our stories through different varieties of experience. In mulling on this, I realized there are four possible ways to “know” something, each one aligning with a different intelligence center.

1. Write What You Experience (Embodied Knowledge)One way or another, there is simply no substitute for our own lived experiences. My lived experience tells me this is so because we experience these real-life moments not just in our heads and our imaginations, but in our bodies. Empathically feeling someone else’s pain, fear, or joy is powerful, but it is rarely a full-body, full-sensory experience. However, what you experience in your own body, even if it as simple as licking salt off your fast-food fries, changes you. If what you’ve experienced is profound, it can alter the very way you look at life itself.

First-hand research of riding a horse or visiting the beach will provide you with the truth of the experience in ways you can’t access simply by observing or reading about the experience. Amp that up, and you realize that when you personally experience life-changing moments, you are the one who just lived through a story. Of course, that then has the potential to become a powerful force within your writing, even if you translate your experience into story events that are far removed from the trappings of your own life moment.

In short, don’t stint on life experiences. I realize this advice will be preaching to the choir for many. Some of you are out there having so much fun that your challenge is slowing down long enough to come in and write about it. However, many writers (*raises hand*) choose writing for the very reason that it seems to be a nice, quiet, introverted way to engage with the powerful moments in life. It lets us be astronomers instead of astronauts, to experience the vastness of space from a safe seat, complete with sun-proof goggles. If that sounds like you, then my words to you are: Don’t forget to go live your own stories to the best of your capabilities.

2. Write What You Feel (Emotional Knowledge)Basically, the above point is all about not using the amazing capabilities of our imaginations as excuses for avoiding the first-hand experiences that will make us more powerful writers. It is not to say, however, that first-hand experience is the only way to write authentic stories. You don’t have to climb Mt. Everest to be able to write about powerful experiences. All you have to do is be willing to look deeply into your own interior.

Don’t think that’s copping out either. Spelunking into the depths of one’s own shadow can be every bit as daring as climbing to 30,000 feet. The trick is a) going there and b) being honest about what you experience. Then bring that back and use it to inform your fiction.

You don’t have to experience war in order to write authentically about fear. You don’t have to crash a plane in the wilderness to write about loneliness. And you don’t have to give birth to write about a parent’s love. But you do have to be willing to go into those places inside yourself that know fear, loneliness, love, joy, hate, ecstasy, bitterness, peace, etc. (And if you find you don’t really know any one of those feelings, then perhaps you’ve found a little bit of homework for point #1, above, or point #3, below.)

3. Write What You Dream (Intuitive Knowledge)By “dream” here, I don’t just mean nighttime dreams, although of course they are always good fodder for fiction. What I’m talking about here is using the actual writing of your fiction as a sort of “dreaming out loud” to access your own inner truths and experiences. Basically, that is what written stories are—“out-loud dreams.” Particularly if you haven’t over-engineered a story with with your left brain, but just let it unfold (whether in an outline or in the first draft), what ends up between the covers of your book will be a deeply disguised but still startlingly accurate map of yourself.

In many ways, the very act of writing fiction is an exploration of knowing one’s self. By that logic, it is impossible for us to do anything other than “write what you know.” Mostly, we do this instinctively, and that’s enough, especially if we’re also engaging in the other practices in this article. But consciously examining our stories (in the same way we might try to interpret a dream) can help us better know ourselves and therefore what it is we’re really drawing on from our own experiences to create the various fantasies (and not just the genre) we’re choosing to put on the page, many of which are archetypal without our even realizing it.

4. Write What You Research (Head Knowledge)Paradoxically, head knowledge can be both the strongest and the weakest of our intelligence centers. It is weak if we overvalue it at the expense of our own lived experiences. But it is undeniably powerful in granting us the ability to write with realism and verisimilitude about just about any topic that interests us.

With a little applied research or a little vicarious experience, we can bring verisimilitude to far-distant historical eras, to politics and power games happening behind closed doors, to fantastical creatures of nonexistent realities, to places in our own world we haven’t the time or money to visit, or to dangerous situations we aren’t trained to handle.

All the research in the world won’t substitute for emotional authenticity and honesty in your story’s scenes, but it can breathe stunning life into the details of those scenes. Dedicated head knowledge can help you fill in a myriad of gaps, while the lived experiences of your life unfold in their own good time.

***

So do you need personal experience in order to write about something?

Yes, you do. You need every scrap of experience from every moment of your life.

But those experiences are are ever-growing. I would say to the young man who emailed me that the stories you write at eighteen are not the stories you will write at thirty-eight, and the stories you write at thirty-eight are not, I daresay, the stories you will write at sixty-eight or eighty-eight. But they are all valid.

A person who has not yet lived through certain life experiences will not write about those subjects in the same way as someone who has, but that doesn’t mean the stories shared by the less-experienced person are inherently less valuable. The value in either boils down to accuracy and authenticity. Write the stories you have to tell right now, and let life’s experiences teach you what you will write next.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think—do you need personal experience to write about something? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Do You Need Personal Experience to Write About Something? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 29, 2022

7 Tips for How to Add Complexity to Your Story

So you want to add complexity to your story. Most authors do. Complexity just sounds so… sophisticated. It sounds like one of those novels or films that are taken apart and analyzed by really smart critics and professors. It sounds like taking your story to the next level.

So you want to add complexity to your story. Most authors do. Complexity just sounds so… sophisticated. It sounds like one of those novels or films that are taken apart and analyzed by really smart critics and professors. It sounds like taking your story to the next level.

And in some ways, it is. Complex stories are things of beauty. These are the stories that entertain audiences beyond just the moment. These are the stories we come back to over and over again, gaining some new insight or appreciation with every re-reading or re-watching.

There is, however, a difference between a story that is successfully complex and one that is just complicated. I talked about this in last week’s post “Is Your Story Too Complicated? Here Are 9 Signs,” which I shared in answer to reader Lila Diller’s request:

Could you define more clearly what you mean about the difference between complex & complicated?

In that post, I pointed out nine different ways stories may be unintentionally and deleteriously complicating themselves. Most of these examples had to do with too many random pieces that just aren’t coming together into a cohesive whole.

In this week’s post, I want to look at the other side of the coin. What is complexity in a story? And what are some tools you can use for how to add complexity to a story without crossing the line into complications?

What Is a Complex Story?Both complexity and complication arise out of “many parts.” The difference is that, perhaps surprisingly, complexity actually keeps things quite simple. “Complicated” stories offer many different elements, most of which stay on the surface. “Complex,” by contrast, puts most of its focus on a few elements, but goes deep.

“Complicated” is clutter; “complexity” is layers.

As you can see, the irony here is that to achieve complexity via depth, you must keep things comparatively simple. Simplicity and complexity walk hand in hand.

Secrets of Story by Matt Bird (affiliate link)

I love how Matt Bird explains this. In his book Secrets of Story, he talks about a realization he had while troubleshooting the plot in one of his scripts:

I suddenly realized my characters spent all their time talking about the plot, explaining it to themselves and explaining it to the audience. This is inevitable when the plot is too complicated. But a good plot should be simple enough that both the characters and the audience understand it just by looking at it.

Sometimes writers write themselves into this conundrum somewhat on purpose, believing readers will be impressed by what is, in reality, just a confusing plot. Often, however, we write ourselves into complications because, when story problems start cropping up, we write one ad hoc solution to this problem and another ad hoc solution to that problem—until, suddenly, as per Blake Snyder, we’ve got “dumble mumbo jumbo” all over the place (and you can add in “toil and trouble,” for my money). The result, as Bird points out, is that we double our word count trying to explain how all these disparate elements somehow really do belong together.

7 Tips for How to Add Complexity to Your StoryOn occasion, excellent writers will be able to explain their way out of their own messes. Usually, not so much. The much better solution is to recognize which tools will help you create a story of cohesive complexity right from the start. Here are seven tips for how to add complexity to your story, without the complications.

1. Adhere to a Clear Structural and Thematic Throughline or Unifying Idea

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Start with the bones. Even the most complex stories (scratch that—especially the most complex stories) should be based upon solid structural and thematic throughlines that are so simple and obvious they can be summed up in a short sentence. If you find yourself wanting to add a lot of “and’s” to this sentence, you know you’re probably straying off the straight and narrow.

This doesn’t mean your official premise sentence necessarily has to be that simple, but the explanation of the plot should be. For instance, consider Game of Thrones. The premise is extremely complicated. But the plot? An all-out battle for the throne before the apocalypse hits. That throughline guides every disparate element and scene in the story.

The first step here is, obviously, to identify your structural throughline (what are characters trying to accomplish and/or stop each other from accomplishing?) and your thematic premise (what thematic element informs the overall story and every character’s role within it?). From there, make sure all of your story’s major structural beats and all of your major character arcs are synced to these guiding lights.

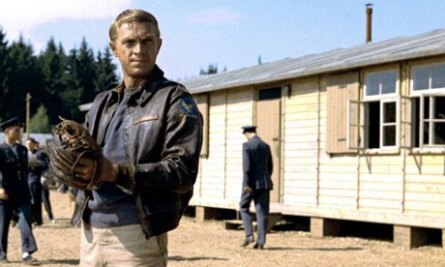

The Great Escape offers one of my favorite examples of how to use cohesive structural beats (in this case adding in a structural focus on the subplot of Steve McQueen’s character) to anchor even a story with a huge cast of characters. Read a structural breakdown of The Great Escape here.

2. Utilize Dramatic Irony Via Both Contrast and ComparisonIrony almost always brings complexity on board. Wherever there is subtext—wherever what isn’t obvious on the surface is just as important as what is obvious—there will be depth. Where there is depth, there is complexity. Irony at its simplest is a sarcastic character saying the opposite of what he means. At perhaps its most complicated, dramatic irony is a satire that you aren’t quite sure is satire—an entire story built as a subtle critique of the very thing it proposes to be (such as, famously, Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey).

On a more practical level, irony arises when contrast emerges from a homogeneous sea of comparisons. One of my favorite ways to create this is through the comparison of the protagonist to an antagonist who is really not so different and the contrast of a protagonist to an ally who is really quite different.

Most specifically, look for ways you can surprise readers by subverting their expectations. Maybe they expect your child character to be adorable, but really she’s heinous. Maybe they expect the antagonist to be heinous but really he’s the adorable one. Maybe they expect the hero to do the right thing, but she doesn’t. Surprises, by themselves, will not necessarily create depth or complexity, but when this added dimension allows your audience to see deeper into characters and situations, you will likely have just added complexity.

One of the reasons Gollum, from The Lord of the Rings, has become such an enduringly iconic character is because he surprises us. For all his grotesqueries and even downright evil, he is also the earnest and heart-wrenching Smeagol whom Gandalf encourages Frodo to pity.

3. Create Thematic Squares

Story by Robert McKee (affiliate link)

A straightforward thematic expression based on a solid character arc is enough to create a good story. But if you really want to up your game into complexity, while still keeping everything streamlined, consider the thematic square. This wonderful tool, originating in Robert McKee’s book Story, is something I’ve discussed in depth in this post.

Basically, it allows you to fill out all four “corners” of your story’s theme, exploring not just a proposed positive Truth, but all its many angles and oppositions. Because you’re focusing on one theme, you will maintain simplicity, but by drilling deep on that one theme, you can suss out all its potential complexities (and give those really smart critics and professors something to talk about).

The western True Grit explores themes of justice and injustice, with every character representing some varying face of one of these polarities.

4. Make Use of the Four Corners of Opposition

The Anatomy of Story by John Truby (affiliate link)

Similarly (and something I also talk about in the above linked post, as well as this one), you can use John Truby’s tool, from his book The Anatomy of Story, to develop a robust and fleshed-out plot. Conflict between your protagonist and antagonist is simple; conflict between your protagonist and the antagonist, the protagonist and the sidekick, the antagonist and the sidekick, the sidekick and the love interest, the protagonist and the love interest, the antagonist and the love interest (you get the idea), that’s complex.

You don’t have to limit yourself to just four characters. Basically, this tool is simply a reminder that conflict (aka, obstacles) should not exist merely in a straight line between your protagonist and your antagonistic force, but potentially between every character in a wide array of possible relationships. This doesn’t mean everybody has to be at everybody’s else throat full bore all the time. The complexity only gets juicier when there are nuanced degrees of opposition in each varied relationship.

Guardians of the Galaxy is one of many films in the Marvel Cinematic Universe that successfully adds complexity to its characters’ relationships by bringing out not just conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist, but also within the group dynamics of an allied team.

5. Focus on Rich Archetypal or Metaphoric IntentSpot-on symbolism is one of the most powerful ways to add complexity to a story. Why? Because symbolism is inherently both simple and complex.

Symbolism is simple because it elicits a universal response from audiences. Even if different people have different opinions about a symbol, they all respond to it on some level. It is complex because it offers depth. Depending on the symbolism, it has the ability to tell a whole story all its own just through its own connotations.

Allegories are the most obvious example of this. Genre stories (such as romance and mystery) are also symbolic unto themselves. Archetypal stories, such as the Hero’s Journey (and so much more), bring a deep mythic underpinning to any type of story that understands and respects their symbolism. Even simply creating and maintaining a consistent metaphor for your story can bring a whole new layer of resonance and complexity.

Everything about Dirty Dancing is set up around the unifying metaphor of dancing as a representation of the protagonist’s burgeoning into adulthood.

6. Remember: Simple Backstory>Complex Main Story or Complex Backstory>Simple Main StoryOne area in which writers sometimes go wrong in accidentally transforming their story’s potential for complexity into unfortunate complications is in weighing down an already complicated plot with an equally complicated backstory. A good rule of thumb is that if your main story is super complex, keep the backstory simple or if your backstory is super complex, keep the main story simple.

A complicated backstory will usually function as a sort of mystery within the main plot, with the characters either actively or incidentally learning new clues as they go along. In turn, these clues influence the characters’ ability to solve the main plot, either directly or through the transformation the revelations create in their personal growth. This is great—but if the backstory revelations are crucial to the main story, this means the characters will spend a significant amount of time tracking down those clues. If they also have to spend time solving complications in the main plot (which are not directly tied in with the backstory revelations), this can lend itself, at best, to a very scattered story.

By the same token, if the main story is twisty-turny and full of mysteries and revelations (whether personal or global), a complex backstory often feels overdone and in the way.

The backstory in the Harry Potter series is deeply complex. Much of the story in the main plot hinges on the discoveries Harry makes about the events surrounding his parents’ deaths. The main plot of the series itself, however, is relatively simple, pivoting around the discovery and confrontation with an obvious villain.

7. Remember: Simple Motivation>Complex Goal or Complex Motivation>Simple GoalA similar rule of thumb is that if your characters’ goals are complex, their motivations should be simple or if their motivations are complex, the goals should be simple.

Motives are not always simplistic. A character’s reasons for wanting to marry someone, kill someone, oust someone, or meet someone can be extremely complex, veiled even to the character. The exploration of the why behind the character’s actions may consume a fair amount of space and explanation within the story. If you then burden the story with a similarly complicated goal, this can easily make the whole thing seem far too convoluted.

Vice versa, if the character’s goal is quite complex (e.g., she wants multiple things and/or her plan for getting them is deviously tricky), then you will need to allot more time to explanations of that. In this case, a complicated motive can just muddy things up.

The plot in Ocean’s 11 is purposefully complex, revolving around a difficult heist with many moving parts. Therefore, the film rightfully keeps the protagonist’s motives super simple and relatable: he wants revenge and redemption.

***

A complex story is a story that knows exactly what it is on every single page. This is true even of extremely tricky stories full of surprises. A complex story is one that is grounded in its own identity. It doesn’t need to explain what it is to readers or distract them with lengthy explanations intended to cover up its own insecurities and identity crises. Rather, it can spend its time looking deeper into its abstractions and gray areas.

Complex stories rest upon a firm foundation of structure and theme; the bones are all there. This is what allows them to stand up straight and shine out from beneath any and all exotic garb in which its writer may want to clothe it.

In short, a complex story is a good story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How to add complexity to your story—what are your favorite ways? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 7 Tips for How to Add Complexity to Your Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 22, 2022

Is Your Story Too Complicated? Here Are 9 Signs

Calling a story “complex” is a high compliment. But what is complexity? How can we learn how to write stories that are complex—without skidding across that narrow dividing line into complicated? What’s the difference between a complex story and a complicated story? And is your story too complicated?

Calling a story “complex” is a high compliment. But what is complexity? How can we learn how to write stories that are complex—without skidding across that narrow dividing line into complicated? What’s the difference between a complex story and a complicated story? And is your story too complicated?

This a topic I’ve spent quite some time contemplating in recent years (not least because one of the major reasons my fantasy WIP went off the rails was my realization in revisions that it was just too complicated). A few weeks ago, in the post entitled “How to Structure Stories With Multiple Characters,” I mentioned in passing that:

One of the most powerful guidelines for any author is to “honor simplicity.” This doesn’t mean you can’t write stories of deep complexity, but it does mean you should never confuse complex with complicated.

This comment sparked a conversation in the comments of that post, in which Lila Diller asked:

Could you define more clearly what you mean about the difference between complex & complicated?

And so a post (or two posts, actually) was born. Today, I want to talk about several of the most common culprits for complicated stories. Next week, we’ll talk about how you can bring desired complexity into your work-in-progress.

What Is a Complicated Story?What’s the difference between “complex” and “complicated”? As I mentioned in my original response to Lila’s question, I like to think of “complex” as “many streams all leading to the sea.” Meanwhile, “complicated” is more akin to “many streams leading to many different seas.” Both are the result of “many parts,” but complexity brings unity to the overall whole by connecting more of those parts, while a complicated story is one in which those many parts don’t quite come together to create a single effect.

9 Examples of Complicated StoriesThere are many different ways, we can complicate our stories. Here are nine that come to my mind.

1. A Plot in Which the Structural Beats Are All About Different Things

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Ideally, your story’s structural throughline (as revealed by its major structural beats) will show continuity. Even if your story is vast and sprawling with a large cast, the structural throughline should be cohesive and focused. You don’t want to see the First Plot Point focusing on the conflict with the antagonist, the Midpoint focusing on a relationship subplot, and the Third Plot Point veering away to put the spotlight on a supporting character.

Iron Man 3 offers an example of a story that over-complicates itself because its structural beats aren’t all focusing on the main plot. (Read more about that here.)

2. A Story Featuring Varied Themes That Don’t Support Each Other

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Theme is often one of the most complex aspects of a story. It offers the opportunity to add layers of depth and interest to an exploration of any single topic. However, to create a unified effect, all the sub-themes should support a single overarching thematic principle.

The easiest way to identify your story’s primary thematic principle is to examine your protagonist’s character arc. Look at the thematic Lie and Truth he will be interacting with throughout the story and especially in the Climactic Moment.

You don’t want your supporting characters’ arcs to focus on unrelated themes. For example, complications are likely to arise if your protagonist’s story is about seeking justice, while your antagonist’s story is about dealing with a midlife crisis and the love interest’s focus is on getting out of debt.

The Last Jedi was scattered in its structural throughline and, as a result, lacked any cohesive thematic emergence from amongst its many subplots. (Read more about that here.)

3. A Setting That Is Scattered or UnfocusedAlthough not the most egregious offender, a scattered sense of setting can exacerbate the feeling that a story is complicated. A tight control of setting (with an eye on thematic intent) will benefit any story. Even in stories that intentionally cover a lot of ground, you’ll want a unifying factor—a pertinent reason why the characters are in these settings.

For example, setting-hopping stories such as those in the James Bond and Mission: Impossible franchises are, in fact, built around the idea of an international setting, which makes it all seem much less random than if, say, Elizabeth Bennett decided to take a quick vacation to Lisbon.

Martin Chuzzlewit offers a notorious example of a random and unnecessary setting, thanks to a lengthy section in which author Charles Dickens shoehorned his title character into a grueling tour of the United States.

4. A Story Featuring Too Many Characters Filling the Same Type of RoleOne of the easiest ways to complicate a story is by adding unnecessary characters. This is especially true when you have multiple characters performing essentially the same role in the story.

For instance, ask yourself how many friends does your protagonist have? If there are several, do they really all play a fundamentally different role within the story? Or are Friends #2 and #3 just adding noise (aka, complications)?

Particularly examine how many antagonists your story offers. Although multiple antagonists can, in fact, add complexity (as we’ll talk about next week), they can also unnecessarily complicate a story. Look at your Climax. The characters who are important in the Climax are the characters who are important to the story. This doesn’t mean you have to axe everyone else, but this understanding will give you an idea of which characters may, in fact, be extraneous.

Spider-Man 3 notoriously sunk itself under the complicating deadweight of three major antagonists, when it would have done much better to have given due diligence to just one.

5. A Character Who Is Trying to Form Goals Based on Too Many MotivationsWe want to write complex characters whose motivations are equally multifaceted. But when the protagonist’s reasons for wanting to kill the antagonist are based on the fact that the bad guy killed her boyfriend and on the fact that she had a bad experience with a serial killer when she was nine and on the fact that the antagonist reminds her the bully she hated in high school, it can all start feeling a bit convoluted and overdone.

I found the motivations of characters in the adaptation of The Witcher to be scattered and unconvincing. Yennefer in particular went from a motivation based on a tight and convincing backstory to having more motivations than I could count—all of which were primary motivations at different times.

6. A Magic System Influenced by Multiple MetaphorsThis one is, obviously, going to be pertinent only to speculative fiction such as sci-fi and fantasy, but it’s an important one. One thing most of the best fantasy stories have in common is a cohesive magic system. This doesn’t necessarily mean it has to be as high concept as, say, Brandon Sanderson’s Allomancy in Mistborn (in which different types of metal grant different types of magical powers). But particularly since you will have to explain the details of a magic system to readers, you don’t want to over-complicate its basic physics.

The Magic System Blueprint by C.R. Rowenson (affiliate link)

The late Blake Snyder called this “double mumbo jumbo.” Basically: if the main metaphor for your magic system is “weather,” you don’t want magic users also drawing power from runes or ghosts or some such. (C.R. Rowenson offers an excellent system for creating cohesive magic systems of all types in his book The Magic Blueprint System.)

7. A Story With “Tonal Whiplash”A story’s tone will set up much of your readers’ experience. If that tone jerks all over the place, it can quickly give them whiplash. This is a problem in its own right, but it can also make an already problematic story feel even more complicated. This isn’t to say a dark story can’t offer moments of tenderness or humor, or that a light story can’t occasionally break your heart. But the tone itself should remain consistent in telling readers what this story is about.

Baz Luhrman’s Australia opens as if it is a lighthearted romantic comedy, gets viewers settled into that, then takes several ninety degree turns into totally new tonal directions—which is not so much a cause as a symptom of its complicated plot. (Read more about that here.)

8. A Story With Disorganized POVsCommon sense tells us that the fewer POVs a story features, the less complicated it will be. And yet common sense also tells us that adding POVs (and even plotlines) can be a good way to add complexity.

So which is it?

It all depends on how the author manages those POVs. Random POVs (which can be caused by narratives that head-hop, narrators introduced late in the story, or narrators who are utilized for only a single scene) will often contribute to a more “ragged” feel for the overall narrative.

On the other hand, a controlled use of POV, in which narrators are carefully chosen not just for their viewpoint but for their thematic importance, and in which transitions are thoughtfully timed with respect to the overall structure and “shape” of the story, can create an organized feel in even the most complex stories.

9. A Story Featuring Plotlines or Characters Who Don’t Come Together in the EndFinally, we have what is probably the worst offender to the charge of a “complicated story.” Many of the above mentioned complications won’t necessarily sink a story all on their own. And audiences will often hold their patience until the end and forgive any loose ends if the finale satisfies them.

If, however, your story’s multiple plotlines and/or many characters do not all come together in the end in a way that feels satisfying, that’s a clear sign you were trying to juggle too many balls and couldn’t catch them all in the end. If you find that either you can’t tie off all your loose ends by the Climax and/or that the only way to do so is to cop to coincidences and contrivances, you’ll want to pull back and examine some of the previous points in this list to see where maybe you can trim out elements that aren’t contributing to the bottom line.

Jupiter Ascending was full of lots of interesting plotlines and teasers—almost none of which were pertinent to the ending or, in some cases. even explained. (Read more about that here.)

***

There are, of course, many other ways a story can complicate itself, but this list is a good place to start. The main difference between a story that is “complicated” and one that is “complex” is simply that the complicated story doesn’t work and the complex one does because it is able to bring all its pieces together into a seamless finale that makes sense.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we will look at how to successfully deepen your story with desirable complexity.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any more ways in which a story may complicate itself unnecessarily? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Is Your Story Too Complicated? Here Are 9 Signs appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 15, 2022

How to Write Emotional Scenes (Without Making Them Cringey)

Learning how to write emotional scenes is one of the single most important feats any writer must rise to. We want fiction to make us feel something. I’m not talking just a little twinge of satisfaction here or there. I’m talking full-on emotional experiences: tears, laughter, cheers, even rage on occasion.

Learning how to write emotional scenes is one of the single most important feats any writer must rise to. We want fiction to make us feel something. I’m not talking just a little twinge of satisfaction here or there. I’m talking full-on emotional experiences: tears, laughter, cheers, even rage on occasion.

Scenes in which characters feel these powerful emotions should usually inspire the same feelings from readers. When done well, these powerhouse scenes become the cornerstones of the entire story. They are the moments audiences are likely to remember long after they may have forgotten beautiful prose or the specifics of the plot.

However, there are emotions you don’t want readers to feel. You don’t want them feeling… icky. Or awkward. When they start reading what should be your story’s most powerful emotional moments, you don’t want them to cringe in response.

You know what I’m talking about. These emotional missteps happen in scenes that are obviously intended to make you feel a certain way about the characters and their actions, but you… don’t.

We’ve all read or watched:

The proclamation of love, complete with singing violins, that was supposed to turn us into sighing mush-puddles, but instead had us wringing out our T-shirts to try to escape the soppiness.The religious conversion scene that was intended to offer us the feeling of redemptive catharsis, but instead had us stonily resenting the thinly disguised sermon.The backstory reveal that was designed to get us sniffling when the emotionally-repressed protagonist put it all out there and shared a vulnerable secret, but instead had us responding with skepticism and irritation because his quick turnabout made the confession feel phony.And the list goes on.

In a recent email, reader Jessica commented to me about how, when deeply emotional scenes are executed poorly, the audience “just wants to run and hide.” She goes on:

And yet, some storytellers can pull this off, and not only don’t you want to cringe, it’s your favorite part of the story. So I was wondering if you had any tips around the difference between achieving that heart-melting thrill versus falling into the cringe, cover your eyes for a moment kind of scene.

I completely relate to the sheer difficulty of creating emotional scenes that don’t feel cringey. When I first started writing, these scenes were my least favorite to write. I cringed my own way through all of them. I had to do a lot of soul-searching and work to figure out how to write emotional scenes. What I’ve learned over the many years since is that the single most important key to writing emotional scenes that truly pull their weight is verisimilitude.

Basically: keep it real. Be vulnerable, be honest—and then learn a few tricks to make sure you’re conveying that personal vulnerability and honesty in a way that really comes across on the page.

Today, I want to dig into this a little deeper.

The Main Two Reasons Emotional Scenes Can Come Off as “Cringey”If you look at our short list of “cringey” emotional scenes, above, you’ll notice all of them could just as easily be found in a list of anyone’s favorite scenes. Love scenes, redemption scenes, personal revelation scenes. That’s the stuff of great fiction. In many types of stories, these scenes are the exact reason we’re investing ourselves in them. These scenes are the salt that brings out the story’s flavor.

So where do authors go wrong? Why can two different authors take the same sort of scene, with one of them producing something deeply moving, while the other just makes audiences want to throw up?

To my mind, there are two main reasons why emotional scenes go off the rails. Both have to do, simply, with bad writing.

1. The Writing Is “On the Nose”The first reason is simply that the emotion in the scene is being portrayed in a way that is too straightforward and “on the nose.” Put simply, this means the author has eliminated all subtext and nuance by stating the facts of the scene too plainly. Not only does this rob realism, but it can also make readers feel as if the author is trying to force them to feel a certain way.

Poorly done conversion scenes are great example of this. Usually, they are very heavy on words (sermons, confessions, prayers, etc.) that are intended to convert not just the characters but the readers. The problem is that if readers remain unconvinced for their own sakes, they are likely to feel unconvinced on the character’s behalf as well. When the character then rises up a changed person, we cringe… because, in fact, we aren’t feeling it.

2. The Writing Is ClichedQuite often, the reason an emotional scene is on the nose in the first place is because the author has failed to look past the obvious choices for the scene. We might write that profession of love as a scene out in the rain because… where else would a dramatic proclamation take place? Since we ourselves have seen a hundred such scenes, we can take the details for granted and assume they will carry the emotional weight of the story all by themselves. However, because readers are so familiar with this type of scene, they are that much less likely to resonate with its emotionalism.

This isn’t to say familiar scenes are always the wrong choice, but you must realize you’re walking familiar ground and work that much harder to bring the emotion to life in a way that is both unique and authentic to your story and your characters.

How to Write Emotional Scenes: 6 Key IngredientsBottom line: readers cringe when they know the author is trying to make them feel a certain way… and failing. It’s like watching a stand-up comedian who is missing the mark so badly that you’re embarrassed. Cringe.

All we have to do to write emotionally successful scenes is engineer them so readers can successfully access the intended emotions. Usually, you will want readers to share your POV character’s emotions. Other times, you may want them to feel a certain way about the character (as, for example, when the character has done something heinous).

Regardless, your starting point is getting clear about what you want readers to feel. From there, you can use the following six ingredients to mix up a perfect recipe of emotionally powerful scenes.

1. HonestyThe first step is to get super honest with yourself. Don’t phone it in… ever actually, but especially in scenes meant to be the emotional cornerstones of your entire story.

If your characters are out there in the rain about to share an epic kiss, don’t try to just paste the requisite emotions on top. Dig deep and be honest. What would you be feeling in a scene like this?