K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 18

August 1, 2022

13 Rules to Be a Better Beta Reader

Among the greatest gifts one writer can give another is that being a beta reader. A beta reader is a volunteer who reads over a rough manuscript and offers feedback on what’s working and what’s not. This feedback can span the gamut from simply a general reaction to a full-on critique. But not all beta readers are created equal. Just as you can learn to be a better writer, you can also learn to be a better beta reader.

Among the greatest gifts one writer can give another is that being a beta reader. A beta reader is a volunteer who reads over a rough manuscript and offers feedback on what’s working and what’s not. This feedback can span the gamut from simply a general reaction to a full-on critique. But not all beta readers are created equal. Just as you can learn to be a better writer, you can also learn to be a better beta reader.

Earlier this year, I receive the following email from Archie Kregear:

I have been doing a lot of beta reading lately. I was looking for a guide/checklist to help folks like me to be a better beta reader. The critique group I’m a part of is prolific, a beta read a month. I’ve searched through your site and nothing on the details, just etiquette.

He’s right. I haven’t written much about beta reading for the same reason I don’t write a whole lot about editing in general, and this because the foundational principles of both are no different from those of good writing. If you know how to write a solid story, you’ll know how to edit one. Indeed, much of the trial and error of learning how to write solid first drafts begins in the trenches of troubleshooting our sloppy first drafts and figuring out how to fix them.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

The simplest answer to “how to edit” is “learn about story structure, character development, good prose, pacing, etc.” The same rules apply in beta reading. However, because of the extra accountability we bear in taking on a beta-reading job, it does deserve some extra forethought.

Most writers will learn some of their most valuable lessons thanks to beta readers. My own early experiences with beta readers transformed the way I approached story, as well as boosting my confidence. But most writers will also encounter a beta reader or two who, despite their best intentions, do more harm than not—either by offering faulty advice or by undercutting confidence. The entire writing community benefits when we all try to become the best beta readers possible.

To that end, here are my top thirteen tips for improving your editing game and becoming a better beta reader. Most of these tips will help you in editing your own stories as well!

Set the Ground Rules1. Get Very Clear on What Kind of Critique the Author Is Asking ForThe first and foremost rule of beta reading is that you are there to serve the story. If it’s important to put your ego in your back pocket and sit on it when you’re editing your own stories, it’s even more important to do so when editing for someone else. The first step toward that end is to make sure both you and the author are on the same page by making sure you understand exactly what kind of critique the author is asking for.

Do they want you to simply read the book over and offer a general opinion at the end: like or dislike?Do they want you to offer a detailed content edit—a commentary throughout on what works and what doesn’t?Do they want a structural edit that critiques plot, pacing, and character arc?Do they want you to get down and dirty with a full-on comprehensive line edit that offers suggestions not just about the story but about the prose?Do they want you to note typos or leave them alone?It is also incumbent upon the author to be clear (and get clear) about their wishes. Nothing is worse for a beta reader than spending weeks thoroughly editing a piece only to realize the author was hoping for something more lightweight.

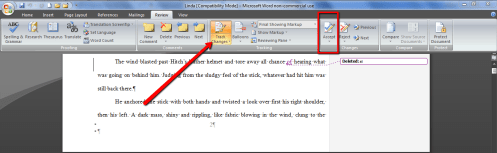

2. Communicate About How to Mark Suggested ChangesYou’ll want to discuss the best way for you to mark your suggested changes. Track Changes is still the best method I know of. As long as both parties have access to Microsoft Word, you can use this tool to easily share your deletions, edits, and comments. The author can then just as easily decide which changes to incorporate or bypass.

However, you might agree that you both prefer working in a Google Doc. You might even ask for an epub you can read (or a doc you can convert to epub) on your Kindle. You can read at your leisure, making notes as you go, then copy/paste them from Kindle Highlights on your computer for sharing with the author.

Don’t be afraid to ask for what’s best for you. At the end of the day, you’re the one doing the favor here. Within reason, it’s fine to ask for whatever setup will be most convenient for your needs.

3. Agree on a Reasonable DeadlineThis one is important for both the author and the beta reader. Depending on the length of the story and the depth of the edit, beta-reading can represent a significant time investment. You’ll want to realistically assess how much time you can put into the project every day and figure out about how long it will take you. Then do your best to honor that.

Many a writer can attest to the frustration and disappointment of trusting a beta reader who never comes through or who keeps fobbing off the deadline. Obviously, life happens, and beta-reading is probably not going to be your highest priority at any time. But once you’ve agreed to help out a fellow writer, do your best to honor that commitment. If you can’t, at least make a point to reach out and let the writer know you’re not going to be able to fulfill the agreement.

Pro Editing Tips4. Be SpecificNow we get down to the actual beta-reading. How can you respond to someone else’s story in the way that will most benefit them? Perhaps the single most important offering you can make to another writer is simply that of being specific. If you don’t like something in the story, try to figure out why you don’t like. If you feel making a big change would benefit the story, try to figure out why you feel that way.

To some degree, any level of editing will always be subjective. But try to get clear on when the suggestions you’re making are based on logical reasons and your own understanding of story—and when they’re based on nothing more than your personal preferences. Your preferences as a reader are absolutely still valid and can be usefully shared with the author, but they should be noted as your preferences, not as universal rules.

Bottom line: always try to be clear with yourself about why you’re making suggestions. Not only will doing so better serve the author, it will also help you further hone your own storytelling instincts and skills.

5. Map Out the Ideal Structural Timing Based on Page Count

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

If the author has asked for a plot edit, one of the key things you can examine for them is how well the story’s structure works.

When beta-reading for someone, one of the first things I do is find the total page count of their story. I divide that into eighths to find the ideal timing for each of the structural turning points, then scroll through the document and add a comment as a reminder to myself to check how well the story’s structure is holding up.

For example, if the book’s Word doc is 300 pages, I would make notes as follows:

Inciting Event: p. 37

First Plot Point: p. 75

First Pinch Point: p. 112

Midpoint (Second Plot Point): p. 150

Second Pinch Point: p. 187

Third Plot Point: p. 225

Climax: p. 263

These comments are just for my own purposes, and I will delete them as I go. It’s also important to note they are indicating the ideal structural timing. Very few stories will line up page-perfect. But the reminders will help you keep track of whether or not the story includes all the important structural turning points, how close they are to the ideal timing, and how much the pacing is affected one way or the other.

6. Don’t Just Point Out Problems, Offer Solutions Where AppropriateWriters don’t need (and won’t always appreciate) if you try to brainstorm solutions for every problem you point out. You want to give them clues and nudges to help them fix their story’s problems in their own unique way. But simply pointing out problems with no explanation or suggested solution can also be less than helpful. Simply saying, “The female lead’s emotional reaction doesn’t ring true here” might not always be enough. You could instead go on to suggest, “Maybe this would be a good place for her to express a little confusion and vulnerability.”

7. Point Out Scenes That Don’t Move the PlotThis one is always helpful. Particularly in first drafts, writers aren’t always aware they’ve included scenes that really don’t do much. If you find yourself bored when reading a scene or feeling you’ve already read this scene several times before, be sure to note that and note why. If you’re familiar with scene structure, you can also examine that to discover any broken or missing pieces that may be interrupting the forward movement of the story.

8. Make Note of Any “Tic” Words That PopNo need to go overboard on this one, but if you start to notice the author consistently uses one particular word, make note of that and suggest they run a search to discover how often they really do use it. However, don’t ding someone for using words that are your pet peeves or that you’re noticing only because you know you have a tendency to overuse them.

9. Create an “Edit Letter” to Address Major IssuesAt the end of editing, professional editors will send clients a document summarizing all the major issues they’ve found in the story. While in the midst of your beta-reading, you can keep a running list of issues you wish you discuss with the writer by the end.

I find it most helpful to divide the letter into broad sections with headers, particularly focusing on major areas such as “Plot Structure,” “Character Development,” “Dialogue,” etc., as well as any issues that are specific to the story.

You can also use the following list to ask yourself helpful and thorough questions about your reaction to the story. You don’t necessarily have to share every answer with the author, but scanning through the list may help you clarify your own reactions to the story.

>>Click here: 17 Questions for Critique Partners

General Guidelines10. Explain Your Reasoning Wherever NecessaryAlthough you don’t want to preach at the author, don’t assume he knows what you know and will understand why you made a particular change. For example, if you edit a sentence to make it more active, you may want to make a little note, explaining your reasoning. Beta-reading is often a mutual learning experience in which writers help each other improve their craft. Don’t necessarily assume you know more than the author, but don’t be afraid to offer helpful tips where appropriate.

11. Try to Interact With the Story Simultaneously as Reader and EditorBeta-readers wear multiple hats. Not only are you (probably) a fellow writer who is approaching the editing of this story as if it were your own, you’re also interacting with it as both an objective reader and an editor. Try to balance those last two identities. Don’t get so consumed by the fiddly work of ruthlessly editing that you don’t occasionally pull back and interact with the story as if you were a random reader who had purchased it. As a beta reader, you’ve volunteered to look under the story’s hood, but the ultimate test of whether or not a story works is whether or not it works for a reader. If you’re able to give your fellow author your perspectives as a writer, an editor, and a reader, you’ll have all the more to offer them.

12. Honor the Author’s Vision for the StoryThis one is super-important. Respect the author at all times. This is their story, not yours. They have their own vision for it, which may entirely different from the vision you would have had. What they want the story to be may also be different from what you, as that random reader, would prefer to read. As a beta reader, you’re not here to mold their story to your preferences; you’re here to help them realize their best vision for the story.

One of the surest ways to do this is to outright ask the author: What’s your intention for this story?

If they can provide a story summary in the beginning, that can often help you determine what type of story they intend this to be.

13. Don’t Forget to Point Out Things You LikeIf you’ve ever been on the receiving end of a critique, you know how brutal it can sometimes be. Even the best of critiques (and often exactly because they are really good critiques) can leave the author feeling overwhelmed. As a beta reader, your primary job is to help the author make the story better by pointing out all the things that don’t work. But pointing out the things you do like can be just as helpful in the long run. Anytime something makes you smile, laugh, cry, or experience any other strong reaction, be sure to make a note. And when it comes time to comment on the story as a whole, try the “compliment sandwich” method. Start by telling the author what you liked best about the story, then share your suggestions for improvement, then end on a final encouraging note.

***

The most important guideline for being a better beta reader is simply the old Golden Rule: Critique other authors exactly how you would like to be critiqued yourself. Respect their hard work and their passion, honor the story they’re trying to tell, be honest but also kind, keep your deadlines and commitments, and enjoy sharing with someone else your deep love of storytelling.

Wordplayers, tell me in the comments! Are there any other suggestions you would add about how to be a better beta reader? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 13 Rules to Be a Better Beta Reader appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 25, 2022

How to Structure Stories With Multiple Main Characters?

One of the most common questions I’m asked is how to structure stories with multiple main characters. If you have two (or more) characters who are equally important to the story and receive equal POV time, how should you balance them when structuring your novel?

One of the most common questions I’m asked is how to structure stories with multiple main characters. If you have two (or more) characters who are equally important to the story and receive equal POV time, how should you balance them when structuring your novel?

At its core, story structure is a simple equation: one primary actor—the protagonist—moves forward toward a goal through a series of obstacles that ultimately demand personal transformation of some kind.

Any discussion of structure reveals that plot is necessarily intertwined with character arc. Indeed, many basic explanations of plot points are in fact less about external forces working upon the characters and more about how the character is changing from the inside out. Usually, these discussions emphasize the protagonist as a singular entity within the story, and usually this is precisely because the protagonist’s character arc is so closely linked to the story’s external plot structure. The single protagonist in alignment with the plot structure produces elegantly powerful stories. If we consider the storyform as a map of psychological transformation, then it makes sense that it is often at its most thematically powerful when it is most streamlined and simple.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

And yet many stories choose to follow multiple main characters, for many different reasons. For one thing, this complexity more closely mirrors our real-life experiences. But, too, some stories are more about the panorama than the personal transformation, and they require more than one character’s perspective in order to give readers all the necessary information.

So how can you structure stories with multiple main characters? If you have more than one person acting and changing over the course of the story, how can you tie them both into one solid structural form, so that everything feels cohesive and appropriately causal?

Let’s take a look.

The Two Different Types of Stories With Multiple Main Characters

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Generally speaking, we find two different types of stories with multiple main characters. Either we see different characters walking side by side in the same structural plotline, or we see them each as the primary actors in separate plotlines which will eventually meet toward the end of the story.

In the first, the main characters will influence one another’s structural progression and personal transformations. In the second, they will probably have little to no impact upon one another’s storylines until their individual journeys finally bring them to a mutual meeting place.

How you structure a story with multiple main characters will depend on which type of plot you’re working with. (For simplicity, the rest of the article will assume we’re discussing stories that feature two main characters, but of course you can have many more than that. Aside from added complexity challenges, the same basic principles apply no matter how many main characters you’re juggling.)

Multiple Main Characters in the Same PlotlineThis is the most streamlined approach to multiple main characters. Even though you have multiple characters, you do not have multiple plotlines.

The characters either share a plot goal or are following individual goals that directly interact one with the other (e.g., one person wants to stop the other).Both are impacted by the same set of plot obstacles, which means they are equally affected by the turning points at the structural beats.They are in each other’s presence for much of the story, allowing for relational progression (whether positive or negative).

The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern (affiliate link)

This is a common choice for relational stories such as romances. Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus comes to mind. We also sometimes see it in mysteries in which partner detectives are featured equally.

We also see it in stories in which the character who would generally be considered the antagonist is elevated to equal importance with the protagonist. This might be done for many reasons, but is most notable in stories in which there isn’t a great deal of moral separation between the characters—i.e., both characters are equally sympathetic and/or equally amoral.

Structuring these stories isn’t much different from structuring a single-protagonist story, in that both characters will be equally affected by the same structural beats. This means that as per usual, you only need to plot a single storyline with a single set of plot points. The trick is making sure both characters are equally affected by each beat. If one character consistently is not an actor in the structural beats and/or is not impacted by the beats, then you may discover you’re really dealing with only a single main character after all.

Important Variation: Protagonist and Main Character as Separate PeopleSometimes we see this approach with stories in which the two characters are not structural equals but still receive equal emphasis within the story. The term “protagonist” refers to the character who is the primary actor in the plot—the character who makes things happen and moves the plot forward. The term “main character” refers to the person who is most central to the story.

Usually, the “protagonist” and the “main character” will be the same person. But occasionally, these roles may be split, with the main character acting as an important observer to the protagonist’s actions. We see this with pairings such as Sherlock Holmes/John Watson and Atticus Finch/Scout Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. In most of these instances, the main character will act as the primary narrator who observes, comments upon, and is probably impacted by the protagonist’s actions—for better or worse.

The more complex approach to stories with multiple characters is that of creating what effectively amounts to multiple plots, each with its own main character following his own structural progression—until the plotlines converge late in the story.

At the beginning of the story, each plotline will be separate from the others.Each protagonist will have a unique goal and meet unique conflict obstacles, which in turn creates relatively unique structural turning points and throughlines.The plotlines will be linked in some way that will eventually bring the characters together in either a mutual or mutually exclusive goal at the end of the story.We see this technique used in stories that require a grand scale. Although these stories can certainly focus on relational conflict as well, they tend to thematically highlight a “bigger picture,” showing one particular crisis through the eyes of different people. Epic fantasies, such as Game of Thrones, often employ this technique.

We can also see it in such stories as Cold Mountain, in which one plotline follows a Confederate deserter trekking home through the mountains, while the other plotline focuses on his sweetheart’s struggles to eke a living out of her farm back home. Other than the obvious relationship between the characters, the two plotlines have no effect upon each other. The primary purpose is that of widening the story’s thematic theater to show the wider suffering of wartime.

The structure in stories such as this is more complicated. Although certain “global” events may be significant enough to occasionally create mutual plot points, most of the time each plotline will create its own structure. This means the events in one plotline will not likely (or at least not immediately) impact the events in the other plotline. This remains true until the plotlines finally converge toward the end of the story.

The trick here is making sure readers understand why they are being asked to follow two separate plotlines. This should be clear either from a thematic standpoint and/or because it’s obvious the characters’ individual goals will inevitably bring them together at some point in the story.

Important Variation: Dual TimelinesSometimes we see this approach in stories that feature not only multiple plotlines but also multiple timelines, in which one of the plotlines takes place in an entirely different time than the other. In fact, it is possible for the same person to be the main character in both plotlines. In one she will be older and in the other she will be younger. This approach is usually chosen when using one timeline to comment upon the other offers either greater thematic depth or heightened suspense.

Timelines will (usually) not converge the way plotlines will, but at a certain point the events of the earlier timeline should provide an important catalyst for the latter timeline, driving it forward into the Climax. Usually, the earlier timeline will be subordinate to the later one, and the story’s structure will bear this out by placing more emphasis and drama on the later timeline’s structural beats.

4 Tips for Managing Stories With Multiple Main CharactersIf you’ve decided your story works best with multiple characters, you can use the following four tips to help you manage this complex approach to storytelling.

1. Identify Your Structural Throughline (Look at the Climax)The most important key for managing multiple main characters is to make sure they are contributing to rather than taking away from your story’s structural integrity. You will want to carefully assess your story’s structural beats to make sure you’re maintaining cohesion and resonance across plotlines and POVs. Look particularly to the Climactic Moment, since this is the scene that “proves” what your story’s structure is ultimately about. Then check all major structural moments leading up to the Climactic Moment, to make sure they are all arrows pointing toward the same endpoint.

2. Balance the POVsUsually, when you are writing a story with multiple main characters, this means you have decided both characters are equally important to the story. The clearest way to signal this to readers is by balancing their POVs throughout. This doesn’t mean you must strictly alternate between POVs every other chapter, but you will want to try to main regular intervals for both.

You also don’t have to be hyper-meticulous in ensuring each POV receives the same word count, but you will want to give them essentially equal weight—otherwise one character will implicitly take center stage as the “real” main character.

It should also go without saying that POVs should be equally interesting to readers. If all the good stuff and all the best supporting characters are lumped into one POV, then you should assess whether the weaker POV is really as necessary as you originally thought.

3. Consider Thematic Resonance

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Even if your story uses multiple main characters and plotlines, it should still feature one cohesive theme. This is best achieved by harmonizing all character arcs within the story. Characters can believe in vastly different Lies at the beginning of the story, but all of these Lies should be challenged by the same thematic Truth by the end. If you discover your main characters’ individual character arcs are about vastly different Truths, then you may find that they pull too hard in opposite thematic directions and end up fracturing your story’s cohesion and resonance.

In adding an extra main character, you have made your story’s structure that much more complicated. This means it is all the more important that every piece contribute thematically. Consider the context these two characters, POVs, and (perhaps) plotlines are creating for one another. What are they saying about each other that neither one would say in isolation? Consider, too, the subtext. Because readers can see the larger picture through the eyes of more than one character, the subtext in each individual POV will grow.

Finally, examine all of your story’s structural beats (and, by extension, each character’s arc) to see how thematically harmonious they are. Cold Mountain is a great example of a story in which the two main characters endure vastly different experiences—and yet both experiences are ultimately about the same thing.

Supporting characters are always important, but they can make or break a story that features multiple main characters. Especially in stories with multiple plotlines, you will want to make sure all the key supporting roles are sufficiently filled in both POVs. Ideally, each main character will be surrounded by a full complement of supporting characters: antagonist, contagonist, mentor, sidekick and/or love interest. These archetypal characters not only add color, they fill key functional roles within the storyform itself.

***

One of the most powerful guidelines for any author is to “honor simplicity.” This doesn’t mean you can’t write stories of deep complexity, but it does mean you should never confuse complex with complicated. This rule of thumb is particularly valuable when writing stories with multiple main characters. The more main characters you add, the more opportunity you have for a certain kind of complexity—but the more risk you run of complications as well.

Choose your main characters with an eye on how those choices will affect your entire story—plot, character arcs, and theme—and use these tips to keep everything balanced and resonant.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever thought about writing stories with multiple characters? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Structure Stories With Multiple Main Characters? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 18, 2022

7 Tips for Opening Your Story In Medias Res

In medias res is the useful but sometimes tricky writing technique of beginning your story “in the middle” of things. At its most basic, this is simply a solid reminder to begin your story with something happening. This might be action in the traditional sense, but it might also just be the character moving toward a scene goal. However, in medias res can cause confusion for writers who feel pushed to either manufacture action for their opening scene and/or open late in the story in a way that compromises the structural timing.

In medias res is the useful but sometimes tricky writing technique of beginning your story “in the middle” of things. At its most basic, this is simply a solid reminder to begin your story with something happening. This might be action in the traditional sense, but it might also just be the character moving toward a scene goal. However, in medias res can cause confusion for writers who feel pushed to either manufacture action for their opening scene and/or open late in the story in a way that compromises the structural timing.

Last week, we discussed some of the confusion that can surround in medias res and particularly how to balance beginning “in the middle” with the need for a solid First Act that properly sets up the rest of the story. This week, I want to take a closer look at the technical side of in medias res, so you can better use it to craft gripping opening chapters that immediately pull readers in to the most interesting parts of your story.

The Pros and Cons of Using In Medias Res

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

One of the main confusions about in medias res is that using it seems require writers to craft opening scenes stuffed with hardcore action and perhaps even with the main conflict already in full swing. Obviously, the former doesn’t work at all in certain types of story. And, as noted, the latter is extremely problematic from a structural perspective.

In medias res, however, comes in many different flavors. In fact, most stories will open with some form of in medias res, even if it isn’t the full-blown type we often think of, in which the hero is already embroiled in some theatrical crisis. As shown in some of last week’s examples, such as Pride & Prejudice, beginning in medias res is as simple as opening with the characters having just piqued their own curiosity about some new development in their lives (i.e., an eligible bachelor moving in next door).

The benefits of using even the subtlest of in medias res techniques are manifold.

1. Creates an inherent hook.

2. Offers the potential for vibrant characteristic moments for important characters.

3. Initiates the story with forward momentum.

4. Helps writers skip all throat-clearing and other unnecessary introduction.

4 (Potential) Cons of In Medias ResWhen misunderstood or misapplied, in medias res can also create the opposite of the desired effect.

1. Interrupts the natural structural progression by starting too late in the story’s timeline.

2. Interrupts the natural structural progression via an irrelevant “action” scene tacked on the front of the book, before getting back to the “real” beginning in the next scene.

3. Focuses too much on physical action to the exclusion of development that would convince readers to invest in the characters.

4. Focuses too much on “sound and fury” rather than genuinely intriguing psychological hooks.

7 Tips for Opening Your Story With In Medias ResThe first challenge in using in medias res is knowing “how much” of the technique is right for your story. Whether you use it subtly as Jane Austen does in Pride & Prejudice or go full-bore as Robert Ludlum does in The Bourne Identity will depend both on your genre and the needs of your specific story. It is vital to understand both so you get the balance just right. Because in medias res is a technique that necessarily influences your reader’s first experience of your story, it must accurately set up your story’s tone and therefore reader expectations for everything to come.

You can use the following seven tips to refine your use of in medias res in any type of story.

1. Know Why You’re Choosing to Open In Medias ResAgain, most stories will open with some form of this technique. Particularly if you’re wanting to use it in a more immersive way by starting out with your character deep in a high-stakes situation, you’ll want to analyze why you’re using this approach and why you think it is most advantageous for your story.

High-stakes stories will often merit high-stakes openings. The difficulty here is that sometimes once authors get a story ramped up in that opening scene, they don’t always know how to slow it back down enough to do the proper set-up work of the First Act.

One option is to open with a high-stakes situation that the protagonist is not yet involved with. Then you can slow back down to introduce your protagonist, now that you’ve let readers know about the suspense on the horizon. Jurassic Park does this particularly well by opening with an intense scene in which an unseen monster kills a bunch of workers, before slowing way down to focus on its characters for the entire first half of the story.

However, this is a tricky approach in itself, since it means you’re opening with a framing scene that basically entails all the usual pitfalls of a prologue.

The two main issues are that:

1. You miss out on one of your best hooks, which is your protagonist, since you’re opening with supporting (and perhaps entirely expendable) characters.

2. You essentially have to write two opening chapters, since you still have to introduce your main characters and hook readers into caring about them.

Knowing your audience and how to set up their expectations for the type of story you’re writing is key.

2. Honor Scene Structure—and Use It to Your AdvantageOne of the simplest and lowest-pressure ways to begin in medias res is simply to begin in the middle of a scene. Specifically, this means beginning with the scene’s structure already underway.

You can view the main part of a scene as being made up of three parts:

1. Goal

2. Conflict

3. Outcome

Knowing this, you can then work the scene’s structure in your favor to begin at a point when the character is fully engaged in the scene’s most interesting action.

Opening in medias res is as simple as beginning with the character already working on trying to accomplish a scene goal (vs. sitting there deciding what goal he should work on). Getting right to the scene goal in the opening scene is the single best way to cut through any unnecessary throat-clearing. You can catch readers up on the “why” as you go or as needed.

You can see how this works even in stories that open long before the main conflict is encountered, such as Jane Eyre, which opens with the protagonist’s simple goal of hiding from her cousins so she can read by herself. This goal is then promptly and dramatically obstructed in a way that perfectly characterizes the protagonist and the stakes of her situation.

You can also open a little later in the scene with the conflict portion once your character has already run into an obstacle to his scene goal. This requires a little more finesse, since it offers the same challenges as opening smack in the middle of any type of action. You want to make sure readers have enough investment in the characters to actually care that they’re poor orphans with mean cousins. (You can imagine how differently Jane Eyre‘s beginning would have felt had it immediately opened with her hitting her cousin in the head with the book, rather than with her hiding away.)

3. Identify How This Scene Opens the PlotAs we’ve seen, opening in medias res does not require opening with the protagonist immediately embroiled in (or even aware of) the main conflict she will later engage in with the antagonist. The entire first quarter of the story (the First Act) is about setting up that conflict and leading the protagonist into direct engagement with it, via first the Call to Adventure at the Inciting Event (which does not take place until halfway through the First Act) and then the irrevocable First Plot Point that leads directly into the Second Act.

Like all scenes, the opening scene must contribute to the plot. It must be the first domino in a seamless row of dominoes, each knocking into the other, to create a causal progression of story events.

You will want to consider how the action you’ve presented in your opening scene offers the first event in your character’s journey toward the main conflict. Even opening scenes that focus predominately on character still need to create situational consequences that prompt the character’s next scene goal—which prompts the next scene goal, which eventually leads to an unavoidable entanglement with the story’s main plot goal and thus the conflict.

For example, Adventures in Babysitting opens with the seemingly random event of the protagonist’s boyfriend canceling their date for the night. In addition to introducing the protagonist and setting up her relationship with her boyfriend, this turns out to be the event that directly kicks off her crazy adventure in the wilds of Chicago with the three kids she agrees to babysit for the night.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Because in medias res usually offers an inherent emphasis of plot and action, it can be easy to let the all-important ingredient of character slide to the back burner. Your characters are your single greatest opportunity to hook readers. After all, if the characters aren’t interesting, why read the book? If the characters are interesting, then readers will happily be entertained by them while you get the rest of the story’s pieces set up for the plot.

It’s always optimal if your opening scene can set up the full trifecta of plot, character, and theme. However, if you have to choose just one, character is usually your best choice. This is why Characteristic Moments are one of the single best ways to use in medias res. Begin with your characters neck-deep in some situation that is relatively normal for them or at least the result of actions and attitudes that are normal for them.

For example, Treasure Planet (one of my favorite adaptations of Treasure Island) opens with teenage protagonist Jim Hawkins getting arrested (again) for showing off his impressive solar-surfing skills in a restricted area. This scene neatly introduces the character’s recklessness, his joy of life, his skills (which will become crucial in the Climax), his flirtation with delinquency (which directly contributes to his mother’s agreement that he go off for “a few character-building months in space”), and his troubled backstory as a fatherless boy.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Sometimes choosing the right moment to open a story is difficult because so many aspects of the character’s life are dramatic and interesting. Narrow your choices by focusing on Characteristic Moments and scene dilemmas that are thematically pertinent to the story to come. Even if your opening scene doesn’t directly touch upon the story’s main conflict in any obvious way, you can still use it to thematically introduce what is to come.

One way to do this is to focus your protagonist’s Characteristic Moment on how she is currently being limited by the Lie She Believes. This limiting perspective will provide one of the main reasons for the protagonist’s engagement with the main conflict once it comes into view. We see this in the Treasure Planet example above and also in stories such as Jane Austen’s Emma, in which the titular protagonist opens by matchmaking her beloved governess (or so she thinks). This event perfectly sets up the character’s growth arc, as well as creating the circumstances that drive the main conflict (the arrival of her governess’s handsome and intriguing new stepson, Frank Churchill).

When using in medias res to begin a story, it’s easy to feel you must rush the first chapter. Using this technique needn’t make your first chapter rushed or chaotic. Even if your opening scene deals with physical action and/or high stakes, you will still want to make sure readers are oriented within your story. You can’t go so fast readers miss out on knowing the who, where, what, why, and how of your scene.

Sometimes the technique of in medias res can be accomplished in as little as a paragraph or two—or sometimes even just a sentence, if that sentence packs a wallop of intrigue. Then you can pull back a bit to set the stage. Another little trick that can help is limiting the number of characters in the first scene. You have to be careful with this, since you need the characters you need, and also because character interaction is often one of the best ways to engage readers. However, if you only introduce two or three characters in the first chapter, you will have less information to juggle in the beginning. You can then draw in other important supporting characters in subsequent scenes.

Stories such as The Great Escape, which do begin deeply in medias res, focus on setting up the initial conflict situation (arriving in a new POW camp) along with the scene’s specific conflict (immediately attempting dozens of escapes), while carefully layering in multiple Characteristic Moments from its many important characters.

Finally, you will want to be careful with backstory. This is true of any opening scene, but it is even more true in stories that begin in medias res. By definition, these stories are firmly focused on the present moment. If they’ve begun “in the middle,” then something must have come before. It can be tempting to begin with a line such as “Harry had never found himself in such a fix before”—and then immediately zoom back to fill readers in on Harry’s entire backstory leading up to this moment.

Although it is important, as per Point #6 above, to make sure readers know enough to orient themselves within the scene, you must be particularly careful about not undoing all the good of an in medias res opening by spending too much time in the characters’ pasts. If you feel the need to keep rewinding in order to catch readers up to speed, that could be a sign that you’ve started too late in the story’s events.

In general, all but the most basic backstory is best shared as late in the story as possible. Tease it out until readers absolutely need to know what’s going on. In the beginning of your story, focus only on backstory that is necessary to properly set up the character.

***

Although in medias res will be used to one degree or another in most stories, it won’t be the right choice for every story. It’s important to understand exactly what it is, how it works, and how to avoid its pitfalls—so you can make an educated decision about the best way to hook readers into your story’s first chapter.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you used any degree of in medias res in opening your latest story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 7 Tips for Opening Your Story In Medias Res appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 11, 2022

Clearing Up Some Misconceptions About In Medias Res

One of the most significant challenges for writers is crafting a beginning chapter that immediately grabs readers. Most commonly, writers are advised to accomplish this via two different methods: the hook and the technique of beginning in medias res, or “in the middle of things.” But are these really two different techniques? And if not, how exactly do they work, either in tandem or separately?

One of the most significant challenges for writers is crafting a beginning chapter that immediately grabs readers. Most commonly, writers are advised to accomplish this via two different methods: the hook and the technique of beginning in medias res, or “in the middle of things.” But are these really two different techniques? And if not, how exactly do they work, either in tandem or separately?

Most readers have limited time and are not interested in reading just anything. These days, many readers make their purchasing decisions based as much on first chapter previews as on book descriptions. This means your first chapter needs to convince potential readers of two things:

1. This is exactly the type of story they’re personally looking for.

2. Your writing is solid enough to promise a good tale throughout.

Quality of writing has much to do with both these factors. If I’m browsing books and I feel the writing style in the first chapter is solid and evocative, I will very likely try it even if it hasn’t given me a gripping hook in the first few pages. My first consideration is always whether or not I will enjoy the writer’s style (because if I don’t, I won’t enjoy putting in the time to appreciate whether the plotting is aces). But good style and a solid hook in the first chapter? That’s gold.

One commonly touted technique for accomplishing this is the use of in medias res. This is a Latin phrase roughly translating “in the middle,” which is generally meant to suggest one of two things to writers:

1. Don’t begin the story before the story’s events (i.e., skip the setup).

2. Do begin with action of some sort (i.e., yeehaw!).

Both bits of advice are solid, but taken by themselves they can also be misleading.

How Can You Use the Technique of In Medias Res in a Three-Act Structure?

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

In medias res means beginning “in the middle of the opening scene” with the character already embroiled in that scene’s action.

It does not mean opening “in the middle of the story structure.”

The only exception to this would be the gimmick of the “flashforward,” in which you open with a scene from later in the story, then return to the true beginning of things (as in, for example, It’s a Wonderful Life, which opens at the Third Plot Plot when Clarence the Angel is briefed about his mission to go save George Bailey).

So the short answer to the question of whether or not in medias res is compatible with the Three-Act Structure is that, yes, it totally is. The secret lies in understanding what is meant by the terms and particularly how the First Act functions structurally.

As regular readers of this site will know, the First Act is all about setup. The First Act sets up the main conflict, but this main conflict will not fully initiate until the Second Act. To open your story with events that should properly be in the Second Act will very possibly have the opposite of the desired effect. Readers will have no reason to care about what happens because they have not yet been given an opportunity to care about the characters.

More than that, the events will ultimately lack resonance and perhaps even realism, since the story’s pacing wasn’t constructed to allow these important story ingredients to develop naturally. This doesn’t mean you need to rewind all the way to the beginning of your character’s backstory and start there. But you do want to identify and start at the best structural beginning for your story.

Feet of Clay by Terry Pratchett (affiliate link)

All that said, we do, of course, see stories that seem to open deep within their own action—and, usually, they are action stories. The Bourne Identity and Captain America: Civil War are two examples, as are many mysteries, such as Feet of Clay from Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series.

Stories such as these get right to the point of the conflict with little to no initial character introduction or development. However, an examination of their structural pacing shows that all the parts are still there. Each story has an intact First Act setting up the main conflict, even though the main conflict is not fully engaged with until a bigger event at the First Plot Point.

For Example: The Bourne Identity plunges us (literally) into the main action right away, showing its gunshot protagonist floating in the ocean just as he is rescued by a fishing schooner. However shocking (and hooking) this may be, however, it is not the main conflict. That will not come into view until the amnesiac protagonist realizes someone is after him.

It’s also worth noting that the latter two examples—Civil War and Feet of Clay—are sequels. This means much of the hard work of introducing characters and getting readers to identify with them has already been accomplished in previous installments. Indeed, if you look at The First Avenger, the first movie in the Captain America series, you can see how, after opening with a flashforward, it then spends the rest of its First Act dutifully introducing characters and setting up its main conflict.

What’s the Difference Between the Hook and In Medias Res?I’ve posted about emotional hooks and structural Hooks many times. I’ve also written a little bit about in medias res. This new post came about after I received an email from someone wondering about the difference between the two. If you’re supposed to skip the setup and begin your story smack “in the middle” of the plot conflict, how does that square with the idea of carefully constructed structural timing?

So what’s up here? How can you use in medias res to grab readers in the beginning while still honoring the principles of story structure? For that matter, do you need to bother with in medias res at all?

What Is “the Hook” in Story Structure?First off, what’s the difference between “a hook” and “the Hook”?

Simply put, a hook is anything anywhere in the story that grabs readers’ attention. However, unless otherwise specified, the word usually refers to the first hook in a story, the one that grabs readers on the first page and convinces them to keep reading. In perhaps its simplest definition, a hook piques readers’ curiosity by asking a question, whether explicit or implicit. Something isn’t quite clear, and readers want to know what’s going on.

The Hook (always capitalized) is the term I use to specifically indicate the first beat in a story’s structure. This Hook naturally includes that first “hook,” but it is also the first beat in the story’s plot. It is the first domino in the line of dominoes that will create your story. It is not random. Via the cause and effect of good scene structure, the Hook will affect the scene to follow, setting off a chain reaction—which will create your story.

Your structural Hook will be causally related to the main conflict. However, keep in mind that the First Act is about introducing the characters and the personal dilemmas that lead to the main goal and therefore the main conflict. This means it is totally possible (and usually imperative) to hook readers in the beginning of the story without needing to directly reference the main conflict. What you will do is thematically foreshadow and setup the elements that will come together to create that conflict in the Second Act.

For Example: Iron Man opens not with the main conflict between billionaire arms dealer Tony Stark and his main antagonists—first the terrorists in Afghanistan, then his mentor Obadiah Stane who is funding those terrorists—but simply with a classic Characteristic Moment, in which he blows off the ceremony for some award he just won and goes to play at a casino instead. This doesn’t directly introduce the main plot. What it does do is set up his character—his potential for outside-the-box brilliance, his disregard for the establishment, and his determined irresponsibility. The story hooks us through character, not through plot or action.

In medias res is the hook technique of opening a story “in the middle of things.” The idea here is to hook readers by plunging them directly into an interesting circumstance. It is one way to cut through any “throat clearing” or “warming up” the author may be doing on the way to finding the best place to begin the story. Rather than starting with a bunch of setup that readers don’t care about, we instead jump right to the good bits.

In some ways, this is always a good idea. Most characters are not interesting enough for their morning routines to properly hook readers. This does not, however, mean you must open with full-on conflict or action. Somewhat counter-intuitively, conflict and action do not necessarily make for the best hook. Until readers are oriented in the story and care about the characters, full-on action or argument can often feel confusing or even (shockingly) boring.

However, it’s almost always best to begin your story with something happening. At the very least, you’ll want to try opening with movement. For example, if your story demands a slower opening with a solitary character, at least get him up and moving. A character pacing in his office is instantly more interesting than one who is sitting at his desk.

Usually, when you see a story that properly begins in medias res, it features the protagonist in the middle of an action-oriented Characteristic Moment, which thematically foreshadows the rest of the story and/or introduces the character’s experience in the First Act’s Normal World. For example, if a character is a spy, she may be introduced in the middle of a mission but not the mission that will comprise the main plot conflict. This technique is also frequently used in sequels, which may open with the character in the middle of a mess left over from the previous story, but which isn’t the structural “middle” of this new story’s conflict.

For Example:You’ll notice none of our three previous examples opens with full-on action or conflict, but they all do open in the middle of things.

Iron Man begins when the awards ceremony Tony Stark skipped is already almost over, while Tony is already collar-deep in enjoying his craps game. More than that, the deal that will send him off to face the true plot conflict in Afghanistan is already underway.

You can see from these three examples that none of them shortchanges the story’s proper structural timing or the First Act’s opportunity to set things up. This means that when the main conflict does arrive (Tony getting kidnapped, Elizabeth meeting Mr. Darcy, World War II starting), readers are already invested in the characters and ready for the importance of the events to come.

***

Full-on in medias res is not a technique you’ll want to use in every book, but when properly understood, it is an extremely valid and useful technique for hooking readers in the first chapter. That is why, next week, we’ll extend this discussion to explore “7 Tips for Opening Your Story In Medias Res.”

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you feel about using in medias res in your stories? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Clearing Up Some Misconceptions About In Medias Res appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 4, 2022

Capturing Authentic Human Reactions in Fiction

Note: I’m taking a break this week to enjoy the holiday in the U.S., so am sharing this shortie instead of the usual post and podcast. Enjoy!

Note: I’m taking a break this week to enjoy the holiday in the U.S., so am sharing this shortie instead of the usual post and podcast. Enjoy!

The goal of all memorable fiction is to capture the truth about humanity. Sometimes that truth is weighty and all-encompassing, such as the ubiquitous “good triumphs over evil.” But sometimes the important truths in fiction are found in the tiniest representations of the world around us and the people who inhabit it. When authors faithfully capture the rainbow glint of a dragonfly’s wing or the raspberry sherbet color of a sunrise, they offer us a nugget of truth about our shared existence.

This is even more applicable when these truths reflect upon human nature itself. Too often, in fiction, we feel the need to streamline our characters’ actions and dialogue. Sometimes the addition of a subtle deviation can reflect human reactions in fiction so accurately it’s worth the extra effort.

For example, William Faulkner was well known for his portrayals of flawed people living in small Southern towns. His accuracy stemmed not just from his knowledge of the geographic area or his willingness to balance the black and white of sins and virtues. His accuracy was also due to the little variations and quirks he captured in his characters’ conversation and behavior.

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (affiliate link)

In his classic As I Lay Dying, he writes about an overbearing woman telling her husband to come in out of the rain, or he’ll “catch his death.” A less experienced author might have been tempted to have the husband immediately voice a reply. But all Faulkner writes about the husband is that he “does not move.” The wife is forced to call his name a second time before he responds.

In this paragraph alone, Faulkner not only allowed readers an insight into the husband’s character, he also presented an exchange that screams with realism. As you guide your characters through your plot, take a little extra time to make sure they’re reacting as authentically as possible.

The post Capturing Authentic Human Reactions in Fiction appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 27, 2022

8 Ways to Avoid Cardboard Characters (and Plot Contrivances While You’re At It)

“The plot was contrived, and the characters were cardboard.” Ouch. That’s about as bad as it can get when it comes to negative story reviews. It’s also perhaps one of the most common complaints audiences have about stories. Certainly, it’s one that irritates me the most! Here’s the thing though: cardboard characters often cause plot contrivances—and vice versa. Once you realize this, it can become a little easier to figure out how to identify and avoid cardboard characters (and plot contrivances) in your own fiction.

“The plot was contrived, and the characters were cardboard.” Ouch. That’s about as bad as it can get when it comes to negative story reviews. It’s also perhaps one of the most common complaints audiences have about stories. Certainly, it’s one that irritates me the most! Here’s the thing though: cardboard characters often cause plot contrivances—and vice versa. Once you realize this, it can become a little easier to figure out how to identify and avoid cardboard characters (and plot contrivances) in your own fiction.

This post was inspired by two different western romance novelists I read recently. Neither was perfect, but one I really enjoyed and the other, although better than many, almost invariably compromised her stories with this dreaded tandem of cardboard characters and plot contrivances. What I recognized was that her characters weren’t cardboard until the plot grew contrived—and vice versa, the plot didn’t feel contrived until the characters stopped exhibiting dimensionality in their choices and actions.

Genre stories that follow tight conventions, such as romance and mystery, are often those I see struggling most with this equation. The authors need to hit certain beats and elicit certain emotional responses from readers, but too often they end up hitting the beats in an artificial way that hampers the overall story, killing both realism and resonance. The irony is that emotional resonance is perhaps most necessary in stories of this kind, since the desire for a very specific sort of experience is exactly why readers pick these books up.

Stories that are more varied—such as, say, an adventure story with a romantic subplot or a generational saga with many different slice-of-life aspects—can get away with less-than-perfect emotional resonance here and there due to fact they’re inherently offering audiences a wider selection of experiences. Of course, this spottiness isn’t ideal in any type of story, but those genres with a tighter focus must be all the more vigilant in evoking a genuine response from readers via a genuine presentation of characters.

Regardless what type of story you’re writing, you can always take everything up a notch by paying attention to this all-important link between cardboard characters and plot contrivances. If your story suffers from one, it probably suffers from both. The corresponding good news is that if you fix one, you will probably inevitably fix the other as well.

The Link Between Cardboard Characters and Plot ContrivancesWhat Are Cardboard Characters?As the metaphor suggests, cardboard characters are… flat. And dry. And colorless.

Remember the “blooper” at the end of A Bug’s Life, when one of the ants starts flirting with an attractive extra, only to accidentally knock him over and realize he’s just a cardboard cutout set up to fill out the necessary “cast of thousands” who populated the anthill?

That’s a cardboard character. Attractive on the surface but not much personality—and certainly not much agency.

Cardboard characters are a writer’s mindless robot minions. They do whatever they’re told, no questions asked. Dimensional characters on the other hand push back whenever you’re trying to make them to do something stupid just because it would make for a cool explosion onscreen. “You want me to slo-mo walk away from the exploding building? No way, lady! You think a real secret agent would do that?”

What Are Plot Contrivances?

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

“Contrivance” means “not genuine.” A contrived plot is one in which the events unfold in a way that simply doesn’t make sense or seems forced. Plot contrivances are the flipside of cardboard characters, so, basically: cardboard plots. These are plots that mechanically hit all the genre beats (although, frankly, not necessarily all the structural beats) as if they were doing a “dot to dot” puzzle. These cardboard plots are particularly obvious when writers try to manufacture a big or exciting scene that lacks proper cause and effect.

Because plot and character are not separate story techniques, but rather two sides of a coin, a contrived plot is almost always the result of a cardboard character who is not showing up to make authentic decisions. If characters aren’t responding to plot events authentically, this will prevent them from, in turn, being able to drive and create an authentic plot. This is most obvious when characters respond to big events without weighing the consequences. For example, someone may choose to make a big (and ultimately even unwise) sacrifice for someone he loves, but not without thoroughly weighing out reasons and options before putting his head in the lion’s mouth.

8 Ways to Avoid Cardboard Characters (and Plot Contrivances)Now that we know cardboard characters equal plot contrivances, and together they equal bad—what can we do about it? After all, the merging of plot and character is a dance. Letting our characters run “authentically” amok with no regard for plot isn’t much better than making the characters mindless servants to the plot events we’re intent on creating.

Here are eight things to keep in mind in order to avoid both cardboard characters and plot contrivances.

1. Learn the Structure of Character Arc, Then Sync It With Your Plot

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Writers sometimes worry that adhering too closely to story structure will cause their plots to become contrived, or at least formulaic. And this can be true if the writer is trying too hard to follow the form without understanding the function. One of the best ways to prevent a contrived plot while also deepening character is to study how the shape of a strong character arc syncs up with plot structure—then let the character arc drive the plot. When you do this, your authorial questions become less about “what I can make happen here?” and more about “what would my character do here?”

2. Assign Character Attributes, Then See What HappensAlthough writing a novel is almost inevitably an exercise in discovering your character, it’s usually best if you can start with a sense of at least a few strong attributes for each character. Contrasting attributes are especially juicy. For instance, maybe you choose the attributes of “generosity” and “cynicism,” or “cheerfulness” and “obstinacy.” Then just make sure those attributes are showing up in each scene. This can admittedly complicate your plotting since sometimes it would be a lot more convenient to the plot if the character were “hopeful” or “cooperative” instead of “cynical” and “obstinate.” But if you adhere to your character’s personality as authentically as possible, she will lead you to some interesting plot situations.

3. Don’t Assign Character Attributes, Then Focus on That ExclusivelyHowever, the caveat for the above section is that you must let your character’s attributes develop naturally. You don’t want your story to end up sounding like you’re beating a drum with just one stick. If you decide your character is cheerful, but that’s all he is, he will of course end up being one-dimensional.

This is one reason it’s so helpful to choose contrasting attributes. How will the character balance an easygoing cheerfulness against his own immovable nature? Although you will almost certainly want to create a likable character, make sure you’re balancing attractive qualities with challenging ones. Romance leads who are all charm and gorgeousness are just as cardboard-y as action leads who never lose a fight or never suffer long-term consequences from their injuries. Those aren’t people; they’re stereotypes. And stereotypes can’t drive a plot.

4. Watch Out for Unnecessary Naivety or IgnoranceIn order for simplistic (or just plain unrealistic) plots to work, writers sometimes resort to characters who can’t seem to see the forest for the trees. At best, they might conveniently need everything explained to them—so authors then have a chance to explain to the readers. Worse is when characters can’t seem to draw simple or obvious conclusions from the available clues—so the writer can then further draw out false suspense or inveigle the character into doing some cool plot thing that, if only he saw the writing on the wall, he would never do.

Naive female leads in romances often strain the bounds of credulity, but so do action heroes who are supposed to be legendary but who seem to lack even the most basic understanding of strategy or defense. Sometimes these attributes can be authentic characteristics, but too often they are just contrivances used to create plot dynamics that simply wouldn’t be possible if the characters were acting more realistically.

5. Avoid Emotional Outbursts With No ConsequencesEmotional outbursts are the stuff of fiction. Proclamations of love in the rain. Furious rages and barroom brawls. Great suffering and great joy. It’s all good popcorn catharsis. Audiences love larger-than-life emotions. What audiences don’t love, however, is when the author uses plot contrivances to maneuver cardboard characters into emotional outbursts just for the sake of the outburst.

First off: See Point #4 above. Most people in real life don’t burst out with their emotions in dramatic or unusual (for them) ways without true incitement. This is because, according to the degree a person is socially aware and emotionally intelligent, he will realize that an emotional display of any kind is a cause that will elicit an effect.

Which brings us to second off: Please, pack your story with emotionally dramatic scenes. They’re my favorite. But make sure those emotions don’t exist in a vacuum. Whether it’s a proclamation of love or a display of temper, your character’s expression of himself should elicit realistic responses (aka, consequences—which don’t always have to be “bad”) from other characters.

6. Focus on Motive Rather Than OutcomeStories get over-weighted onto the plot side of the balance when writers focus more on the outcome of a character’s actions rather on the character’s motive for that action. This isn’t to say the outcome isn’t important, but if you’re cramming your character into a showdown scene just because you happen to want a showdown in your story, that may end up feeling contrived. But still… you want that showdown!

So how can you weave it into your story in a way that feels authentic? The answer is to focus on the setup to the scene. What would authentically motivate this character to engage in a showdown? For that matter, ask yourself, “What would authentically motivate you?” Even if your personality is wildly different from your character’s, if you find there’s no way under the sun you would ever do that same action with so little motivation, then think about whether maybe your character’s inner development needs a little more work.

7. Never Bend Character to Fit PlotThis one can get tough. Plots are sprawling and often unwieldy things, and even the best writers can struggle to get them to run in tandem with their characters. Admittedly, sometimes exceptions must be made, in which characters do certain things that might not make 100% sense. This should be done seldom and only with a great deal of caution and sleight of hand, so hopefully readers neither notice nor mind.

Most of the time, however, a character should be respected like a real-live human being—and not forced to do something she doesn’t want to do. That is, she shouldn’t be forced by you, the author. It’s a different proposition if the story, via the other characters, are messing with her day.

And that’s the whole point: throw whatever plot events you want at your characters but make sure they are reacting to them in ways that are unique and realistic to themselves. Your characters may have no choice about what happens to them; sometimes they may not even have a choice about what they do in response; but they should always have a choice about how they feel and rationalize about what happens.

8. Choose Authentic Character Reactions Over Dramatic OnesPlot contrivances usually occur because the author is looking for drama instead of realism. The two are not incompatible. In fact, the best drama is often the kind that emerges from the most realistic situations. Let’s say your character does something heroic—like turn himself in for a crime he didn’t commit in order to protect someone else. That’s super dramatic, right?

Now, whether or not it’s also realistic and authentic will depend on how you play it out. If the character walks to his doom with chin held high, misty-eyed with his own martyrdom, unflinching in the face of a greater good—or if he insists, even in the face of reason, that this is the only choice—that’s just melodramatic. But if this same character spends sleepless nights agonizing over his decision and searching out every other possible alternative before taking the hit—not only is that much more realistic, it’s also much more dramatic. It feels real, so it has resonance. Where there’s resonance, there aren’t likely to be any cardboard characters or contrived plots.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your top trick to avoid cardboard characters and plot contrivances? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 8 Ways to Avoid Cardboard Characters (and Plot Contrivances While You’re At It) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 20, 2022

Understanding the New Normal World of a Story’s Resolution

A story’s Resolution is a tiny section of the overall story. From the perspective of structural timing, the Resolution represents 2% or even less of the story’s total running time. Some stories give it the generous portion of as much as a few chapters. But in other stories, the Resolution may be implied more than shown, given as little as a quick summarizing sentence or two. So why are we spending a whole post investigating the symbolic “world” of the Resolution? Simply, because the New Normal World of a story’s Resolution is, in many ways, what brings the entire picture into view.

A story’s Resolution is a tiny section of the overall story. From the perspective of structural timing, the Resolution represents 2% or even less of the story’s total running time. Some stories give it the generous portion of as much as a few chapters. But in other stories, the Resolution may be implied more than shown, given as little as a quick summarizing sentence or two. So why are we spending a whole post investigating the symbolic “world” of the Resolution? Simply, because the New Normal World of a story’s Resolution is, in many ways, what brings the entire picture into view.

Over the last few weeks, this series has been exploring the symbolic lens through which each of the three acts of a story can be viewed. So far we’ve talked about:

1. The Normal World of the First Act

2. The Adventure World of the Second Act

3. The Underworld of the Third Act

4. The New Normal World of the Resolution

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

I have long used the terms “Normal World” and “Adventure World” to describe the respective essences of the First and Second Acts. Although the specific terms are not found in discussions of the Hero’s Journey, both are based on the psychological principles found in the archetypal transformation of the Hero’s Journey, as originally codified by Joseph Campbell in The Hero With a Thousand Faces. He talks about the Ordinary World the Hero departs, the adventurous “Quest” that comprises the main conflict of the tale, and the “Descent” into the “Innermost Cave” that correlates with the structural Low Moment of the Third Plot Point and the Third Act.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

He also talks about “the Return.” One of the key principles of the Hero’s Journey is that a Hero who has been successful in his Quest will return to his home so the people he left behind may also benefit from what he has gained from his travels. The other important aspect of this beat is the opportunity it offers to contrast who the Hero was at the beginning of the story with who he is now. By returning him to the same, or a similar, situation as the Normal World at the beginning of the story, everything is brought full circle: plot, character, theme, setting, imagery, etc.

The Resolution itself exists to tie off loose ends, allow the pacing of the story to fade to a final resounding note, and create the final emotional effect upon the audience. Whether meant to confirm or add irony to whatever has come before, it is the final bit of trimming on the finished story. Even if the presentation of the New Normal World in a story’s Resolution is extremely brief, it is still an important beat for creating cohesion and resonance in the overall effect. (It’s also a great opportunity to practice chiastic structure!)

The Normal World of the ResolutionThe Resolution represents the final scene or scenes of the story, perhaps from 98% to 100%. It occurs at the very end of the Third Act (which began back at the 75% mark) and takes place just after the Climactic Moment. As the word suggests, the Resolution resolves the story. Even though the main conflict has ended with the previous beat of the Climactic Moment, most stories require at least a quick “sequel scene” in which to show characters’ reactions to what just happened and to provide context for the protagonist’s victory or failure in the preceding Climax.

What Does the New Normal World Symbolize?

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Although in some standalone stories, a character’s arc will be definitive, that’s not really how it works in real life. In real life, we follow one personal transformation with another and another. Change in the external world, no matter how dramatic, is never conclusive. If there’s one thing that is always the same it is that things always go on changing. Therefore, the New Normal World of a story’s Resolution exists both to cap off the change experienced by your characters in this story and also to reset the stage, if only by implication, for the next change.

The Normal World of the First Act symbolized and dramatized the Lie the Character Believed at the beginning of the story. It represented the status quo that was about to end. Now that the character has interacted with both Lie and Truth throughout this story, finally aligning with one or the other, the New Normal World now represents the new status quo. In a story in which the protagonist changed not just herself for the better but also the world around her, this new status quo will usually contrast positively with the previous one.

In some stories, the protagonist will return to basically the same world from the First Act, but with new eyes to be able to appreciate or interact with it in a more positive way, such as previously unhappy Dorothy Gale being able to say “there’s no place like home” when she awakens from her dream in The Wizard of Oz.

In other stories, the protagonist will follow Joseph Campbell’s model more closely by returning to her original Lie-ridden world and offering it the healing “Elixir” she picked up during her travels, as in The Return of the King, when the hobbits return to find the Shire gravely oppressed and deteriorated and use their newfound skills to restore it.