K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 20

March 14, 2022

How to Know When You’re a Successful Author?

How to know when you’re a successful author? I suppose almost every writer asks this at some point—and very likely at frequent points. There are multiple ways to define and measure the answer. For many of us, the answer seems come down to commercial success. And yet because commercial success is sometimes elusive, this metric often seems at least vaguely unsatisfactory.

How to know when you’re a successful author? I suppose almost every writer asks this at some point—and very likely at frequent points. There are multiple ways to define and measure the answer. For many of us, the answer seems come down to commercial success. And yet because commercial success is sometimes elusive, this metric often seems at least vaguely unsatisfactory.

Recently, Wordplayer Rhonda Denise Johnson emailed me the following thoughts on the topic:

If you haven’t already, would you be interested in doing an article on how to know when you’re a successful author? What is the sine qua non of a professional success? When you land a deal with a big publishing house? So, should indie authors count themselves out? When your aunt Harriet stops asking you when you’re going to get a job? To paraphrase a writer is not without honor except in his own house.

I sometimes feel discouraged because I’ve been disappointed by the quality of writing in one too many so-called best sellers. It leaves me feeling like excellence doesn’t matter in this industry as long as your books sell. What we do when we craft a novel seems too precious to be measured in dollars and cents like merchandise, vacuum cleaners, and cheeseburgers. How then should an author measure herself, and how does he know when he’s “made it” as an author?

Rhonda’s email reminded me that I did, in fact, write a post on this topic: How to Tell if Your Book Is a Success. I wrote it at a time when my own career was relatively young and when I was earnestly asking the same questions of myself. My personal take on the subject remains pretty much the same as when I wrote that post, but since it’s been ten years (!), I decided it might be worth revisiting the topic, for myself as much as anyone.

Why Do We Feel It’s So Important to Be a Successful Author?Taken at face value, the question of “how to know when you’re a successful author?” offers some pretty basic and obvious answers:

When you’re published.When you’re a bestseller.When you make at least a comfortable amount of money.When you’re famous.When you achieve critical acclaim.However, as soon as we drill down to any depth, what is also obvious is that all these answers speak to entirely different experiences within the publishing journey. For instance, just because you’re published does not mean your book will sell, provide you a living, or be widely read. And as Rhonda pointed out, just because you’re a widely-read millionaire does not mean you will necessarily achieve universal critical acclaim.

Right away, we can see that perhaps one of the reasons “how to know if you’re a successful author” is such an unceasing question for writers is that there really isn’t a solid answer. That said, the one thing that all these answers have in common is that they are pointing to the experience of writing something that finds external validation. At first glance, we might think this simply points to the need for ego gratification, but I think if we go down yet another layer, we find that what writers are really seeking from these forms of external validation is simply a sense that what we’re doing has meaning.

We all write for many different reasons. But mostly I’d venture that, under it all, we write for two reasons:

1. To share ourselves.

2. To impact others.

Both of these objectives, however unconsciously measured, are foundational to the human’s need to feel that who we are and what we do has meaning—that our time in this life matters in some way. But both of these are highly abstract and thus difficult to measure. You may write something that changes my entire life, but you’ll probably never know it. In fact, I may not even know it. I may read your words, internalize them unconsciously, and never realize they were the fulcrum on which my future just turned. But it doesn’t matter if either one of us fully realizes what just happened. What you wrote—who you are—just mattered. I’d say that makes you a successful author. And yet… you may never know it. Certainly, you can’t measure it.

And so, we usually turn to more concrete measures of success, as defined by whether others are willing to read our work, publish our work, pay us for our work, and praise us for our work.

These are all entirely legit metrics of success, particularly if our abstract motivations are also driving eminently practical goals such as making or supplementing a living. But if we focus our definitions of what it means to be a successful author entirely on practical metrics, it can be easy to discount our true and deeply personal definitions of success.

My Evolving Definitions of What It Means to Me to Be a Successful Author

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

When I wrote my original article, pondering what it meant to be a successful author, I was about four years into the biz of being an indie author. I’d published two novels, neither of which had gone gangbusters, and my first writing-craft book, Outlining Your Novel, which had done well. It was a time when I was beginning to find the culmination of some of the more practical definitions of success, while also coming to terms with areas in which my career was not looking like the poster version. I was just starting to make enough money to be able to write full-time, and yet indie authors were still largely viewed as “less than.” Particularly since I wanted to be a full-time novelist, not a full-time non-fic writer, I sometimes felt conflicted.

Time went on, and the website continued to grow. I published more novels that met with only moderate sales and more writing guides that continued to sell solidly and allow me to launch into being a full-time writer. By most practical metrics, I could view myself, at least as an entrepreneur and non-fiction writer, as successful. I had accomplished many my goals, and yet the “success” finish line always seemed out of reach. I began to realize that continuing to measure my success by outside metrics was a never-ending treadmill. There were always better sales rankings to achieve, a higher income to chase, more awards to seek. Wherever “there” was, I’d never reach it. There was always more external validation to seek.

In short, my experience has been that defining success is a slippery thing. Even if you reach the baseline of what popular consensus agrees is “successful,” this doesn’t automatically mean you will have found either personal or perpetual success.

So how do I define a successful author—both for myself and others?

Certainly I factor in external metrics. By most commonly agreed-upon definitions, success does entail publication and decent sales. If I see an author who checks those boxes, there’s a little “success” light that goes on in the back of my brain. But the light also goes on when I read a little-known indie work or an unpublished novel and it’s awesome. And that light also goes on when I hear from writers who by their own definition have reached success, whether this means finishing a first draft, self-publishing, or even simply writing something for themselves that helped them find personal healing or happiness.

In short, I believe the single most important metric in knowing whether or not you’re a successful author is first and foremost getting super-clear on your definition of “success.”

How to Define Your Own Success as an AuthorWhy are you writing? It’s a question with a multiplicity of answers. But if you can dig down to the root, you’ll probably discover the essence of your own definition of success.

Most of us write primarily because it scratches a deep-down itch. But you are also likely writing because you want external validation.

For you, maybe it’s enough just hearing that a reader had fun reading your story or was moved by it. Or maybe, for any number of reasons, you want writing to be a lifestyle—and you need it to pay for itself. Or maybe you just want to feel your own joy and excitement about your story mirrored back to you in excited reviews.

Whatever the case, try to get as specific about your reasons as possible. Then create a personal metric that can act as both your mission statement and your measuring rod as you journey forth to seek success. Most likely, you will find that you have many layers of metrics, some of which will evolve with you as time passes. Examine not just your own goals (i.e., finish the first draft, get published, get 10 reviews, sell 1,000 copies), but also how you define other writers as successful. In your view, are only the super-famous such as Stephen King successful? Are only books about serious topics successful? Are only traditionally-published authors successful?

There are no wrong answers. There are only your answers. For instance, if you realize you need the stamp of a traditional publisher in order to feel successful, that’s probably a sign that, at least at this point, you should steer clear of publishing your book independently. If you realize you feel a certain dollar sign is your definition of success, then you can distill your goals to help you leverage your marketing. If your primary reason for writing is simply self-expression, this may help you feel successful even if external validation is lacking.

For me, two realizations are paramount in helping me define my own success.

One is that success is a moving target. At one point, selling 1,000 books seems like success, but after you’ve reached that, the definition may change into selling 10,000 books, 100,000, even 1,000,0000 or more.

Second, “success” is only the point insofar as it offers a reward. That reward may be simply the sheer practicality of keeping the electricity turned on. Or it may be the need to prove something to yourself—that you can write a book, publish a book, sell a book, share a book that matters to people. When whatever it is ceases to offer personal validation, it can no longer be used as a benchmark.

The pitfall to be avoided is identifying ourselves with any one definition of success—and especially if that definition comes from someone other than ourselves. Success, in the end, doesn’t matter. It comes and it goes. Only a few of the authors you now see ranking on Amazon will be remembered past their own lifetimes. To use metrics such as sales, reviews, etc., to calibrate our goals is one thing, but to define our identities as “successful” or “unsuccessful” based on these things misses the true heart of what it means to live a meaningful life as an author.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your metric for how to know when you’re a successful author? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Know When You’re a Successful Author? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 7, 2022

How to Write a Book When You Have No Idea What You’re Doing

I want to write a book.

I want to write a book.

You remember when this big idea first hit, right? Maybe you were browsing for books, waiting for an author’s autograph, or sitting in stupefied awe after finishing a great novel. The idea took root and then, bam, you’re rushing to a stationary store to gear up, buying all the notebooks, pens, sticky notes, and highlighters you can carry. You browse online for writerly things—a cute laptop sticker or a mug that says, “Writer at Work.” The moment that mug arrives, you’re filling it with something or other, setting it next to your stack of notebooks, and pulling the keyboard closer, because IT’S TIME.

You open a new document. Your hands flutter to the keyboard. This is it—the magic is about to happen.

Onscreen, the cursor blinks. And blinks.

Boy, the page is so white. How did you not notice before? And that infernal flickering cursor… is it just you, or does it seem kind of judge-y?

And that’s when you realize your big idea has a second part to it:

I want to write a book…but I have no idea where to start.

Thankfully, this truth, while inconvenient, doesn’t have to stop any of us from writing. It may seem daunting at first, and doubts might try to sway us (What was I thinking? I can’t do this!), but I’m here to tell you that, yes, you can write a book.

7 Tips for How to Write a Book When You Have No Idea What You’re DoingNot knowing where to start is a problem countless writers before us have faced and figured out, so if you are feeling a bit lost when it comes to your big dream, these seven things can help you move forward and better yet, jumpstart your writing career.

1. WriteSure, this seems obvious, but starting can be paralyzing. We worry about committing our ideas to the page because what if they resemble some four-year-old’s Cheerios-and-glue “masterpiece”? Well, guess what? They might, and that’s okay. Great storytelling takes time, and if that didn’t put off Stephen King, Susanne Collins, or Nora Roberts, it shouldn’t stop us, either.

Outlining Your Novel Workbook software

To begin, try dreamzoning. Jot down your ideas, or try outlining the story you envision using one of these methods or this outlining software. Or start with something small, like a short story or scene. At the start, our goal should be getting comfortable with putting words on the page and have fun, not pressuring ourselves into penning the next Game of Thrones.

2. Read and RereadReading is so enjoyable we tend to forget how each story is a treasure trove of education on what makes a book good, bad, or off-the-charts great. So read widely, thinking about what makes each story compelling. Look for characters that stand out, story worlds that seem so real you feel part of them, and plots that keep you flipping pages long into the night. Ask yourself questions:

What made certain characters larger than life?Did their personalities, complex motives, or a truth they live by pull you to them?What scenes and situations seemed the most real to you?Studying where you fell under the storyteller’s spell can help you see how you can do the same for your readers.

3. Join a Writing GroupOne of the best things you can do at the start of this journey is find others on the writer’s path. A community of writers puts you in touch with those who have the same goal, meaning you can learn from and support one another. Plus, having creatives in your circle helps to keep you accountable, meaning your butt stays in the chair and words get written.

4. Collect a War Chest of KnowledgeWe all start with some talent and skill, but to write well we need to train up. Visit Amazon to find writing books with high reviews so you can judge which might be most helpful for your development. Make note of the title or ISBN and order them at your favorite bookstore.

Another way to build your knowledge is by subscribing to helpful writing blogs. Bite-sized learning can be perfect for a time-crunched writer. I recommend exploring Katie’s sidebars because Helping Writers Become Authors is full of storyteller gold. Visit this page on outlining, and this one on story structure because understanding how a story works will help you get your first ideas off the ground so much easier. And the Story Structure Database is a great way to see all this plot and structure information in action.

You should also make learning about characters a priority because they drive the story. Getting to know who the people in our stories are and what makes them tick helps us understand what’s motivating them, and that makes writing their actions and behavior easier. Once you have a better handle on plot and character, turn to other storytelling elements and techniques. There’s so much great stuff to learn!

5. Take a Course or WorkshopInvesting in guided or self-guided learning can also kickstart your progress. The community is packed with great teachers. Below are some good options, but first, if you belong to a writing organization, check to see if they offer members classes for free or at a discount.

Reedsy Learning CenterBang2Write CoursesLawson Writer’s AcademyJami Gold WorkshopsJerry JenkinsWriting for Life WorkshopsMichael Hauge (Hero’s Two Journeys)6. Look For Step-by-Step HelpAs any writer will tell you, the road from an idea to a publish-ready novel is a long one, and it’s easy to get lost along the way. It’s no fun when we don’t know what to write next, or we don’t know how to solve a problem in the story. And, if we get too frustrated or our writing stalls for too long, we might end up quitting. Having an expert offer guidance as you write can keep you on track.

Some writers like to partner with a writing coach so they get personal feedback and support as they go. If this is something you might like, here’s a list to start with. A benefit is that you’ll learn a lot about writing as you go, but depending on how long you need coaching for it can get a bit costly. So another option might be the Storyteller’s Roadmap at One Stop for Writers. This roadmap breaks the novel-writing process into three parts: planning, writing, and revising. It has step-by-step instructions on what to do as you go, and points you to tools, resources, and articles that will make the job easier.

The Storyteller’s Roadmap also has built-in solutions for the most common writing problems, so whether you need to overcome Writer’s Block, Impostor’s Syndrome, or stop new ideas from derailing your story, the Code Red section keeps you on track.

7. Above All Else, Be FearlessStarting a book can seem like a monumental undertaking, and sometimes with big dreams, we have the tendency to try and talk ourselves out of them. We fear failing, because we think that’s worse than never trying at all. If you feel the passion to write, don’t let fear stop you. The world needs great stories!

Wordplayers, tell us your opinions! Have you started writing a book, or are you still in the “thinking about it” stage? Tell us in the comments!The post How to Write a Book When You Have No Idea What You’re Doing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 28, 2022

Should You Take a Break From Writing? 5 Red Flags

Writers are supposed to write. That’s just how it works. But should you ever take a break from writing? Is that just code for quitting? Is it a sign you’re copping to your own laziness or fear? Or that you’re really not a disciplined, “serious” writer?

Writers are supposed to write. That’s just how it works. But should you ever take a break from writing? Is that just code for quitting? Is it a sign you’re copping to your own laziness or fear? Or that you’re really not a disciplined, “serious” writer?

The short answer: Who knows? Only you know.

The more general answer is that, at some point for almost all writers, taking a break from your writing becomes valuable and perhaps even necessary. At the date of my writing this post, I daresay more writers than usual have been asking this question. When the pandemic hit in 2020, I heard from many writers who just couldn’t quite find it in themselves to write. And in the months that followed, all the way through 2021, I started seeing more and more writers publicly talking about how taking a break from writing was something they were focusing on—perhaps even for the first time in their careers.

I was among those writers. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, for me the challenges of 2020 came on the heels of what was already a difficult writing period in my life. By the time 2021 rolled around, I made the decision to give myself a year-long “conscious sabbatical” from writing my fiction. It was one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever made. But I believe it was also one of the best decisions.

Toward the end of last year, I received an email from Labrava Altonia, which echoed the difficulties and concerns that I feel are quite prevalent write now. Labrava wrote eloquently of struggling with narrative fiction, including the guilt that so often (if so senselessly) dogs us when we’re experiencing writer’s block:

Recently, I’ve been taking a writing break which is ironic because when I look in my notebooks, I’ve doodled almost ten pages of words every day. It’s more so a break from writing narrative-driven fiction and writing towards dedicated WIPs because I’ve been having anxiety attacks in front of a computer. I’m returning to writing towards dedicated projects, with all the outlining and word count goals and exciting revisions, and I’m excited but I also have a sense of dread. I know it’s good to write scared but there’s SCARED and then there’s SCARED where you’re having panic attacks because you’re associating the natural difficulties of writing with your value as a person, a toxic self-doubt.

So mainly I wanted to ask how do you know when to take breaks and when to push forward? I’m trying to go slow but the line’s even fuzzier for me because my anxiety blurs the difference between a natural break vs. procrastination, and my pushing forward during a difficult passage can also lead to burnout, but if I don’t push forward it can lead to a lack of forward momentum.

As I’m writing this, I’m starting to realize a lot of my questions will be cleared as I go back to writing and naturally feel out my limits without anxiety clouding my mind. But I’m still interested in how you approach discipline vs. the spontaneity of just taking a break from writing one day because you feel like it. Basically, self-trust.

I responded with my own experience:

It’s interesting you should ask me this right now, because I am nearing the end of taking a year-long break from my fiction writing. I’ve called it a “conscious sabbatical,” but really it was a step back from writing due to writer’s block. It’s the first time I’ve ever had writer’s block, and the first time I’ve consciously taken a break from writing in almost two decades.

It’s been interesting. And scary.

I am hoping/planning to stick my toe back in the water next year at some point (I know I will be having some more big life changes to deal with, so also trying to work around that). And I don’t know quite what to expect.

I don’t have any profound answers for you, other than to perhaps normalize your experience some. I’ve heard from many writers in the past two years who are struggling with their writing in relationship to the more stressful world we’re all living in post-COVID.

For me, finally letting myself take a conscious break was something I did as an act of compassion and kindness for myself. It was a recognition that I am not what I do, even writing, and my worth is not defined by how many words I write every day. It was a recognition that my body and my nervous system are trying to talk to me, trying to tell me there are reasons writing has become so difficult, and that if I want to return to writing, I first need to acknowledge and address those reasons.

Humans—perhaps especially writers—are so hard on themselves. We expect ourselves to perform like machines. But I have come to believe, in the past year, that sometimes taking a break from the creating is one of the most creative things we can do.

So I would say this: Go with the flow. Look into your own fears. Hold yourself with compassion as your explore them. And trust life. Don’t resist what is here for you in this moment even if it is adamantly not writing. If you are meant to write again, you will. If not, you will find what you are meant to do next.

That is what I keep telling myself.

Because this is a topic that has been on my mind for so long and because it is one I feel so many other writers are working through in one way or another, today I’d like to take a specific look at this question. When should you take a break from writing? And once you’ve taken that step, what in heaven’s name are you going to do with yourself? Here are my thoughts.

5 Signs You Should Take a Break From Writing1. You (Really) Don’t Want to WriteI’m not talking about that feeling you get every day when you sit down at the keyboard and suddenly experience the desperate urge to go fold laundry or something. I’m not talking about the resistance we all feel to the undeniably hard work of writing. I’m not even talking about those periods where you hate your story, hate your words, hate your characters—and just want to flush the whole thing down the toilet.

What I’m talking about here is a deep true knowing within you that writing is not what you want to be doing with your time right now. It could be that this feeling does indeed grow out of the those daily-grind type of resistances mentioned above. If you keep hammering away at a story you don’t like or that isn’t working long enough, you will need a break sooner or later if only to regroup. There is certainly a fine line sometimes between the kind of resistance you need to work through and the kind of resistance you need to listen to.

But deep down, you know. For me, there finally came a point when I knew that to keep trying would only be self-defeating. Instead of writing my way back into writing, I was more likely to force myself to a point from which I would never be able to return to writing with the same joy and passion I once had. So I listened to that, and I took a (long) break.

2. You Feel Exhausted, Drained, or Burned OutThe really-don’t-want-to-write feeling can come on for many reasons. Perhaps one of the most prevalent is simply that you’re tired. This exhaustion might be induced partly or wholly by life factors unrelated to writing (like, um, a pandemic). But it might also simply emerge because you’ve been writing for a really long time—years and years, decades even. Or maybe it’s more to do with a concerted amount of effort over a comparatively shorter amount of time, as when you’re pushing for a deadline. Just finishing a big project is usually reason enough to give yourself at least a short break.

Burnout is not something to be taken lightly. It’s not just a word for “really-tired-but-if-I-just-take-a-nap-I’ll-get-over-it.” Burnout is a physiological fact that, when serious, creates depletion on any number of levels including the physical (which needless to say affects everything else). You can think of serious burnout for a writer as if it were a major injury for a pro athlete. You might be able to come back from it, but it takes a lot of rehab. Even if you do come back, you may not be able to function at the same (probably impossibly high) level you used to demand from yourself.

The best solution is to catch burnout before it starts or its very early stages, which are usually precipitated not just by physical exhaustion but that very real inner resistance telling you, “I don’t want to do this; please stop.” If you can heed that early enough, take a break, and regroup, you can stave off the worst of the damage before it happens. And let me tell you: it is worth it.

3. You’re Experiencing Fear or Other “Life-Based” BlocksI believe there are two different types of writer’s block: “plot blocks,” which have to do with story-specific issues in which something just isn’t working or making sense, and “life blocks.” Plot blocks are relatively easy to work through with time, patience, discipline, and continuing education. Life blocks, on the other hand, are often largely unrelated to the writing itself and require deeper work while they follow a timeline all their own.

If you find yourself resisting your writing out of a deep sense of fear, dread, anger, or another similar emotion, what you’re experiencing may well have less to do with the story and more to do with a larger issue in your life. This might be anything from trauma, grief, illness, stress, or even that burnout mentioned above. In some cases like this, continuing with the writing might be the single best thing you can do for yourself in helping you work through your issues and find catharsis. But in other cases, the added pressure of forcing yourself to meet a certain word-count goal every day only adds to the problem.

Only you can determine which is true for you, and just because staying with the writing may feel like the scarier or harder choice does not mean it’s not the right one. But it’s important not to beat yourself up for being a “bad writer” if what you’re dealing with is really something much bigger and perhaps even something entirely out of your control.

4. You Don’t Know What to WriteI used to think I’d never run out of stories to tell. And I haven’t. I have several ideas I love stored away in my files right now. And yet, for the past few years, none of them have seemed the right ones to tell. They seem out of sync with my current self, my evolving perspectives, and even my interests. In short, they’re just not the stories I want to tell right now.

And sometimes it be like that.

Sometimes we can sit down at the page, freewrite, and end up with something that at least makes us curious enough to keep pulling the thread. Other times, we absolutely know what we want to write. We have an idea in our heads that is bursting with our own passion to tell it. And sometimes the reason we don’t feel like writing is because we don’t currently have something to write.

If you’re dealing with any level of burnout or stress, this could simply be because your creative well is empty. If so, taking a break from the actual writing in order to refill the well is the single most responsible thing you can do as a writer. More than that, sometimes we do just have to wait for the inspiration to find us. In this era of “fast fiction,” when writers are expected to always be churning out a new story, it can be easy to forget that the inspiration doesn’t always follow the writing—but the writing does always follows the inspiration.

5. You Need to Prioritize Other Commitments Right NowPut simply, sometimes writing is the most important thing we can possibly be doing. And sometimes it’s not. For people who claim an identity as writers or who have a great dream of making writing their life, it can be difficult to realize that sometimes other parts of life are just as important—if not more so.

This realization may be as simple as accepting that you’re pushing yourself too hard and you need to take a break for your own health. But it could also be thrust upon you through no choice of your own. It might be something big, like the illness or death of a loved one. It might be a global situation, like the pandemic. It might be a positive but still energy-consumptive life transition like graduating, moving, getting married, having a baby. It might be that writing isn’t your money-making job, and you need to concentrate more time on whatever does keep the lights on and the cupboards filled.

Or it could just be that you want to focus on another passion for a while—travelling, painting, going back to school, farming, whatever it may be. Writing is so important. I believe this with all my heart. But it is not the only important thing in life, even for writers. Not even close. Without doubt, there will be times when it is the least important thing in your life.

4 Beneficial Things to Do During a Writing BreakSo you’ve decided to take a break from writing. Maybe it’s a month-long break. Maybe it’s a year-long break, like mine. Maybe it’s indeterminate. Now what? What do you do with yourself during that time, and how can you take full advantage of your break to come back to the writing even stronger?

1. Write… Other StuffJust because you feel the need to take the break from one kind of writing doesn’t mean you have to ditch the words altogether. For me, my “conscious sabbatical” was specifically from writing fiction. But in that same year, I wrote the rough draft for a book about archetypal character arcs, over forty blog posts, and hundreds of journal entries. Although you may decide that a cold-turkey break from your writing is best, you may also find that nurturing your word-brain in other ways is most restorative while you rest the burned-out part.

2. Take Care of YourselfRegardless the reason behind taking a writing break, the whole point is that you’re doing this for yourself. You’re doing this because you realize that being “on push” with your writing right now is not helping. So take that even further. Ditch any guilt and decide to offer yourself all the support, compassion, and healthy decisions you can during this time. This is even more crucial if your reason for taking a break from writing has to do with other stresses or pressures in your life.

3. Fill Your WellTo the best of your ability, try to consciously use your break to refill your creative and energetic well in whatever way you most need.

Maybe you just need some chill time in front of a cozy fire.

Or maybe you need to focus on your physical well-being.

Or maybe you need to read and watch whatever most inspires you.

Or maybe you need to branch out and explore new subjects or mediums of art.

This isn’t about self-indulgence (per se); rather, it’s about finding your sweet spot and absolutely bathing in it for at least a short period of every day.

4. Examine Your Resistance to WritingYou may know exactly why you’re taking a break (e.g., you’re in between projects and want some proactive me time). But if you’re facing serious resistance, burnout, or life blocks, you may be uncertain exactly what’s going on. Don’t ignore that. Take it as slow as you need, but discipline yourself to consistently examine why you’re feeling this overwhelming resistance to your writing. Why is something you presumably love so much filling you with so many difficult feelings? What you find may be easy enough to recognize and correct. But it may also turn into a long and twisting quest into the underground of your own soul. Stay with it. At the very least, you’ll come back out with some great fodder for your writing when you decide to return to it.

***

The kind of writing break I’m discussing in this post is the kind you don’t take lightly. It’s the kind you resist, probably for a long while, for many deeper reasons. If making the decision to take a serious break from your writing were easy, there would be no need for this discussion. I can attest, from my own lived experience and from the many conversations I’ve had with other writers, that confronting this aspect of the writing life is often filled with deep angst.

And so I would close simply with the reminder that if you’re facing this angst, it is almost certainly pointing to something deep and ultimately valuable within your life. You’re being challenged to try different tactics, to take care of yourself, and perhaps to take a deep look at yourself, your motivations, your habits, and your priorities. This is a good thing. If you can do all that as faithfully as you’ve pursued your writing, you will emerge from your “conscious sabbatical” with some amazing treasures.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever felt the need to take a break from writing? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Should You Take a Break From Writing? 5 Red Flags appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 21, 2022

9 Ways to Approach Relationship Dynamics in Fiction

Creating an amazing supporting cast that can offer important relationship dynamics in fiction will also help develop your protagonist. This isn’t just because great supporting characters will add color, drama, and nuance to your story in their own right. It’s also because every supporting character in your story has the ability to bring out new dimensions and complexities within your exploration of your protagonist.

Creating an amazing supporting cast that can offer important relationship dynamics in fiction will also help develop your protagonist. This isn’t just because great supporting characters will add color, drama, and nuance to your story in their own right. It’s also because every supporting character in your story has the ability to bring out new dimensions and complexities within your exploration of your protagonist.

The primary way this is done is simply through the relationship dynamics between your protagonist and other characters. Mary Carolyn Davies’ famous wedding poem “Love” suggests:

I love you,

Not only for what you are,

But for what I am

When I am with you.

Arguability of the notion’s simplicity aside, this does offer a perspective on how a person tends to be at least slightly different in every different relationship. Different people bring out different facets of our personalities. This should hold true for our protagonists as well.

I was pondering this recently after experiencing a random memory of The Andy Griffith Show. My family watched this classic sit-com over and over and over again when I was young, so I kinda tend to see the world through a Mayberry-tinted haze. (My sister and I slay at the game Taboo when we’re on the same side; all we need is an Andy Griffith reference to communicate telepathically: “You remember when Barney tried to invite Thelma Lou on a date but Opie answered the phone?” “Duck pond!”)

Anyway, not to digress, but my random musing was about how hapless deputy Barney Fife’s every relationship in this show served to bring out a different dynamic within his personality, always to comedic effect. His relatively healthy friendship with his boss Andy showed him as a (mostly) respectful subordinate. But whenever he’d deputize the even more hapless Gomer, he’d turn into a mini-tyrant. More conscious characters like Andy would rarely bump Barney’s fragile ego or antagonize him, but others like town drunk Otis refused to play along with Barney’s delusions of grandeur and would unhesitatingly initiate schoolyard-esque squabbles. Even Barney’s sweet relationship with his official girlfriend Thelma Lou was different from the pseudo-suave persona he used with his “telephone” girlfriend Juanita.

Part of why this example is so fun—and obvious—is that Barney was an extremely unstable personality who switched personas frequently in order to try to boost or cover up his own raging insecurity. But even with a more mature character, the opportunities are just as rich for dramatizing different facets within different relationships.

A Few Different Approaches to Character DynamicsOther than just trying to make “every relationship different,” there are also a few more strategic approaches for diversifying your protagonist’s personality via his interactions with other characters.

The Three Primary Characters—and Their ProxiesOne of my favorite lenses for examining the roles of characters within plot and theme is to remember there are really only three types of character in any story.

1. Protagonist

2. Antagonist

3. Relationship Character

The protagonist is the central character, whose actions drive the forward progression of the plot. The resolution of this character’s goal (in the story or, on a smaller scale, in any given scene) determines the shape of the story.

The antagonist is the character (or characters or entity) who opposes the protagonist’s forward momentum in the story or in any scene.

And the relationship character is the character who in some way inspires or impacts the protagonist’s motives, actions, and growth.

Obviously, most stories contain far more than just three characters. But if you view your cast through this lens, you will begin to discover the core purpose of any character’s role in your story. Theoretically, every character in a tight story will be one of these three—or represent one of the main three by acting as a proxy in some way. The relationship character, especially, may be “divided” into different characters who can thematically represent different motivating or driving factors to the protagonist (e.g., parent, love interest, child, etc.).

Truby’s 4-Sided Conflict In his book The Anatomy of Story, John Truby speaks of “four-sided conflict,” which he illustrates as a rectangle, with a different character at each corner and arrows connecting them all. His idea of story’s relational conflict is that it should not be isolated to simply the protagonist and the antagonist. Rather, every character in the story should be in conflict (whether large or small) with every other character.

In his book The Anatomy of Story, John Truby speaks of “four-sided conflict,” which he illustrates as a rectangle, with a different character at each corner and arrows connecting them all. His idea of story’s relational conflict is that it should not be isolated to simply the protagonist and the antagonist. Rather, every character in the story should be in conflict (whether large or small) with every other character.

This doesn’t mean everyone needs to hate each other and be in open war. But even within friendships and loving families, power dynamics (and sometimes outright struggles) are always at play. Even when we are on the best of terms with someone else, we still want something from that person and that person wants something from us. But what you want from your mother is not the same thing you want from your boss, and what you want from your boss is not the same thing you want from the gas-station attendant. The dynamic is different in every case.

By keeping this in mind and remembering that all supporting characters are a universe unto themselves—with their own burning needs, desires, and weaknesses, same as your protagonist—you can keep tabs on how each unique character might in turn bring out something unique in your protagonist.

Parallel CharactersScreenwriter Matt Bird uses the phrase “parallel characters” to describe how each supporting character should mirror something in the protagonist You can also zoom this out a bit and examine how each supporting character can represent the thematic premise in a different way. This gives the protagonist the opportunity to interact with many different moral, philosophical, and practical facets of the central dilemma, which can be dramatized via his or her own strong reactions to these other characters.

6 Different Polarities to Explore in Relationship Dynamics in FictionHere are six simple but powerful dynamics you can explore by creating unique relationship dynamics in fiction between your protagonist and the supporting cast. Each is a polarity, a set of opposites. If you can figure out a way to realistically create competing relationships in which your protagonist alternately plays either role, you might find out some things even you didn’t know about your characters!

1. Friend/EnemyWe all need friends, but most protagonists will find at least a few enemies as well. This is usually the most obvious relational polarity in fiction, since we tend to think of conflict in terms of enemies and allies. Regardless what type of story you’re writing and which category is emphasized, be sure you offer a contrast. More than that, consider how your protagonist will interact with each category. He’ll be comfortable with a friend character, but uncomfortable or even aggressive with an enemy character. One gets his love and devotion (or not?); the other gets his resistance or worse. However high or low the stakes, the protagonist’s mode of interaction between these two types of supporting character will be wildly different.

2. Superior/SubordinateLike our friend Barney Fife, it’s probable your protagonist will encounter some supporting characters who are her superiors and others over whom she herself wields authority. How is she different in these different relationships? Is she respectful to both her superiors and her subordinates? Is she more responsible to one or the other? Does one or the other bring out her insecurities and her ego-defense tactics? The point isn’t that she needs to response well to one person and badly to the other. But if you can emphasize a difference of some kind, you’ll find the hidden complexity.

3. Attack/Defend/WithdrawThese are three common relational reactions. Examine which is your protagonist’s favored mode when under pressure. But also examine your supporting characters. If they’re all reacting with the same mechanism, that’s a missed opportunity for depth. Moreover, there may be reasons why your protagonist (or other characters) choose different tactics in different scenarios. You don’t want to be too random here, but it can be powerfully revealing when a character whose default mode is to “attack,” suddenly chooses to instead “withdraw.”

4. Passive/AggressiveAs we explored earlier this year in our lengthy series about the shadow polarities of various archetypes, most unbalanced responses fall into one of two categories: passive or aggressive. Which does your protagonist favor? And which do your supporting characters prefer? Obviously, the passive/aggressive polarity falls into line with the above categorization of “withdraw/attack.” I would tend to put the classic designation of passive-aggressive (as a third category) in line with “defend” (not in the sense of defending healthy boundaries, but rather in the sense of being “defensive” in a reactionary way).

5. Positive/NegativeIs your protagonist the type whose initial response is more likely to be “yes” or “no”? Does he see his interactions with other people as if the world were half full or half empty? (And, note, that the two questions don’t necessarily align.) We can add “realist” as a third option, although in this context I would differentiate it as simply someone who is centered and does not use a determinedly negative or positive mindset in a reactionary or defensive way. Characters who favor either positivity or negativity can be used to exaggerated and comedic effect, but played with more subtlety they can simply be used to challenge your protagonist’s moods and views in different relationship dynamics.

6. Confident/InsecureCan’t use Barney Fife as an example without bringing up this one. We all have insecurities, although some of us mask them (even from ourselves) better than others, but we can depend on its being a sliding scale. Examine your protagonist and the characters surrounding her. The interesting question isn’t so much “Who is more insecure than the others?” but rather “How do they each exhibit, cover up, or compensate for their individual insecurities?” And how might their insecurities—or lack thereof—interact with other characters’ insecurities?

***

Because all characters in a book ultimately arise from one personality—the author’s—it can be easy to miss opportunities for adding complexity to your cast. Simply in noticing whether or not every character interacts with the protagonist a little differently, you can begin to observe where your characters may be a little too homogeneous and how you can increase both complexity and realism.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do some of your supporting characters bring out different relationship dynamics in fiction? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 9 Ways to Approach Relationship Dynamics in Fiction appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 14, 2022

Archetypes and Story Structure: How They’re Connected

By its very nature, story structure is archetypal. It is a pattern we recognize emerging from story. It is a pattern as big as life itself, and therefore one about which we are always learning more, but it is also a pattern we have been able to distill into specific systems that help us consistently recreate these deeply resonant archetypes in story after story. In studying story structure and character arcs, one of the coolest things I’ve recognized is that these archetypal patterns show up in surprising ways.

By its very nature, story structure is archetypal. It is a pattern we recognize emerging from story. It is a pattern as big as life itself, and therefore one about which we are always learning more, but it is also a pattern we have been able to distill into specific systems that help us consistently recreate these deeply resonant archetypes in story after story. In studying story structure and character arcs, one of the coolest things I’ve recognized is that these archetypal patterns show up in surprising ways.

We spent a good part of last year studying what I called the “life arcs,” consisting of six primary transformative character archetypes (and eighteen supporting archetypes). These archetypal character arcs can be seen to make up the overall arc of a human life—beginning with the coming-of-age arc of youth and travelling all the way to the final challenges of confronting and embracing the mysteries of Life and Death. Not only do these innate journeys expand the options for archetypal journeys far beyond the beloved Hero’s Journey, they also offer an amazing zoomed-out view of the common pattern of story structure itself.

I referenced this in the original series about archetypal character arcs, but as I’m now working on a book version of the subject, I realized this phenomenon deserves to be examined more specifically. So today I want to highlight two different angles of this:

1. The cycle of the six archetypal character arcs shows us, as humans, how life itself is structured like a story.

2. The cycle also shows us, as writers, how the story structure in any individual book can be strengthened by recognizing that each of the classic structural beats mirrors specific archetypal chapters in life itself.

The Microcosm and the Macrocosm of Story StructureI like patterns. I particularly like the spiral—a pattern that repeats in infinite expansion. It’s a pattern we find everywhere in life. So why should story theory be any different?

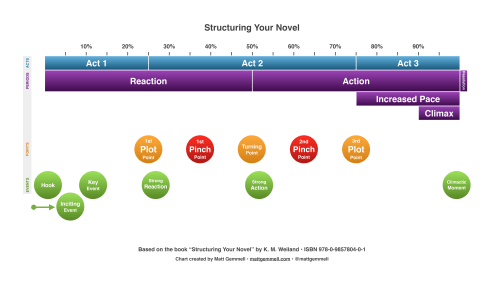

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

We already recognize that the arc of a story can be found reflected in smaller pieces of the whole. We see it on the level of scene structure, in which each scene creates a mini-story arc, complete with Inciting Event and Climax. We also certainly see it within the structure and arc of each individual act within an overall story. Indeed, each structural section, chapter, and beat ideally mirrors this pattern to some degree.

But we can also see this pattern projected out from story structure itself onto a larger domain. First, we may see the arc reflected from within a larger series (anything from the obvious three acts of a trilogy to a much longer series). But also, eventually, we can see it in life itself.

The perspective of the archetypal “life arcs” is certainly not the only archetypal system through which to view story or life. But it is an amazingly resonant tool for linking story structure to life and and life to structure. As we’ll explore more intricately below (and as I’ve covered in considerable depth in my series on the subject), each of the six archetypal character arcs directly corresponds to one of the major structural beats in classic story structure.

Graphic created by Matt Gemmell. Click to enlarge.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

Most people have heard of the Hero’s Journey, made famous by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. What not everyone realizes is that the microcosm of the Hero’s Journey in fact itself represents the macrocosm of the entire life cycle of arcs. Campbell alludes to this in his original breakdown of the journey, and then dives into more depth in the book’s final section, which goes beyond just the Hero’s Journey as most of us have come to understand it.

He uses different titles from those I found most resonant for the life arcs, so I’ve included the terms I use (with links) in brackets:

Transformations of the Hero:

1. The Primordial Hero and the Human [Child—initial Flat archetype]

2. Childhood of the Human Hero [Maiden Arc]

3. The Hero as Warrior [Hero Arc]

4. The Hero as Lover [Queen Arc]

5. The Hero as Emperor and as Tyrant [King Arc]

6. The Hero as World Redeemer [Crone Arc]

7. The Hero as Saint [Mage Arc]

8. Departure of the Hero [usually signified by Death]

Students of story have long been able to apply structure to their own lives and use it as a surprising metric for recognizing archetypal moments and cycles. Once you understand the terms, it’s hard not to see Inciting Events, First Plot Points, Moments of Truth, and Third Plot Points popping all over the place.

But more than that, once you factor in the archetypal arcs, you can reverse engineer these life beats into the structure of any individual story and use it to deepen the truly archetypal resonance of any particular beat. For example, when you begin to study the parallels between the Inciting Event in general and the Maiden Arc in the life cycle, both begin to take on deeper meaning.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Today, let’s take a quick overview of how story structure lines up with the archetypal character arcs.

For the purpose of our study, it is important to remember that each of these six character arcs will build upon the previous ones to create the big picture of one single “life arc.” The partner arcs within the same act are not interchangeable but distinct (i.e., the Maiden and the Hero are not simply gendered names for the same arc) and can be undertaken by any person of any gender. The arcs are alternately characterized as feminine and masculine primarily as an indication of the ebb and flow between integration and individuation. Together, all six life arcs create a progression that can be found in any human life (provided we complete our early arcs in order to reach the later arcs with a proper foundation).

>>Click here to read more about story structure.

>>Click here to read more about character arc fundamentals.

>Click here to read more about the six “life arcs” and other character archetypes.

First ActIn story structure, the First Act represents the first quarter of the story or roughly the first 25%. It takes place in a familiar “Normal World” that, however great (or not), is constricted by certain limiting beliefs. It is the place from which the character departs. It is the status quo to be changed.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the First Act can be seen to represent the first 20–30 years of the human life—youth, in short. It is comprised of the sequential Maiden Arc and Hero Arc, both of which are focused specifically on the character’s learning how to individuate from the Normal World in which he or she grew up.

Inciting Event | Maiden ArcIn story structure, the Inciting Event is the first important structural beat with the story. It is the turning point, halfway through the First Act, taking place around the 12% mark. It is synonymous with what Campbell called the Call to Adventure, in which the protagonist first “brushes” against the story’s main conflict. The character will not yet leave the Normal World at this point, but she will, for the first time, glimpse the Normal World’s limitations and see an opportunity for growing beyond it.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Inciting Event equates with the Maiden Arc. This is the first of life’s transformative archetypal character arcs, signifying the character’s coming of age. Represented by puberty and the fraught years that follow, it is a “waking up” from the dream of dependent childhood into the realization that the world is much bigger. The Maiden Arc protagonist will not necessarily leave the physical Normal World within her story, but she will begin to individuate from her authority figures and caretakers, so that she can leave on her subsequent quest.

In the Maiden Arc story Bend It Like Beckham, Jess lives at home with her parents, whom she loves but who do not understand or support her to desire to play soccer (football).

First Plot Point | Hero ArcIn story structure, the First Plot Point is the first of three major turning points. As the threshold or “Door of No Return” between the Normal World of the First Act and the Adventure World of the Second Act, it takes place around the 25% mark. This is where the protagonist fully engages with the main conflict. He leaves the comparative safety and familiarity of the Normal World in a way that, either literally or symbolically, means he can never return to the way things were. Everything has changed; the story is now fully underway.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the First Plot Point equates with the well-known Hero Arc. Also an inherently “youthful” arc, this one follows sequentially on the heels of the Maiden’s individuation and focuses on questions not just of independence but, eventually, of re-integration with a larger community. As he leaves behind all he has known and enters a strange and dangerous new world, the Hero focuses on questions of self-reliance, personal autonomy, and eventually responsibility. Although still operating mostly from the limited perspectives of his childhood, he begins now to confront the increasingly complex “real world” and its demands for him to balance his own needs with those of the greater good.

In the Hero Arc story Spider-Man (2002), Peter’s life is radically changed when he witnesses (and is partially responsible for) his beloved uncle’s murder.

Second ActIn story structure, the Second Act represents the middle two quarters of the story, roughly from 25% to 75%. It takes place within the main conflict of the “Adventure World” and is focused entirely on moving the protagonist forward through a series of obstacles toward a final plot goal. These outer challenges will prompt the character’s inner growth and transformation, increasingly broadening the character’s perspective of life even to the point of altering her relationship to the plot goal itself.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Second Act can be seen to represent roughly years 30–60 of the human life—or, adulthood. It is comprised of the Queen Arc and the King Arc, both of which are focused on the character’s relationship to others and to power. Between the two arcs, the Midpoint and its Moment of Truth changes everything, signaling a shift in focus from “acquiring” in the first half of life to “letting go” in the second half.

First Half of Second Act | Queen ArcIn story structure, the First Half of the Second Act is traditionally a period of comparative “reaction.” Having passed out of the Normal World through the Doorway of No Return in the First Plot Point, the protagonist has already taken a significant step into claiming her personal power. But she is also overwhelmed by the new challenges that face her, particularly since the worldview she brought with her out of the First Act limits her ability to understand and thus succeed in this new environment. Over the course of the First Half of the Second Act, the character will gather tools, resources, and allies that help her expand her understanding and move into a place of competence.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the First Half of the Second Act equates with the Queen Arc. Having returned successfully from the questing of the Hero Arc, the character is now represented by the Queen—a person of significant power and responsibility but one who is focused more on providing and nurturing than actually wielding that power. Her challenge is that of transitioning into true stewardship and leadership of her family/people. She summits in a powerful victory and takes the throne.

In Queen Arc story A League of Their Own, when the players learn their league is struggling, Dottie leads the charge with theatrical stunts that bring in crowds, inspiring the other players to do the same.

Midpoint | Moment of TruthIn story structure, the Midpoint and its all-important Moment of Truth takes place halfway through the story at the 50% mark, acting as a fulcrum for both plot and character arc. Here, the character glimpses the great Truth at the heart of his arc and begins to understand the conflict’s bigger picture and therefore how to respond to it in a new and more effective way.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Midpoint technically occurs between the Queen Arc and the King Arc. I see the Queen Arc as being more properly representative of the Midpoint’s “Plot Revelation,” which allows the character to upgrade her external efficacy in the plot. This can be seen in the Queen’s rise to the throne. Meanwhile, I see the subsequent King Arc as being more representative of the Moment of Truth, when the character’s relationship to the thematic principle alters through the understanding of a deeper Truth previously unavailable to him. This Truth evolves his tactics in the external plot, but more importantly it changes his understanding of the conflict’s overall context and his own role within it.

Second Half of Second Act | King Arc

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

In story structure, the Second Half of the Second Act is traditionally a period of “action.” Having benefited from the lessons of the First Half of the Second Act and particularly its Midpoint, the protagonist now understands what to do better than he ever has before. Although still unable to fully relinquish limiting beliefs, he is now able to move through the conflict with much greater efficacy and empowerment. However, this ever-deepening understanding of the thematic Truth challenges almost everything the character thought he knew about himself, his plot goal, and the conflict itself. By the end of the Second Act, he will have to confront his darkest demons and discover whether or not he is honest enough to truly embrace his Truth.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Second Half of the Second Act equates with the King Arc. The King Arc represents both the height of the character’s temporal power and also the beginning of the end of that power. Confronted with deeper truths about the nature of Life and Death, the King must struggle between his desire for immortality and the practical need to begin releasing his power and passing the torch to the next generation. Now that he has seemingly gained it all, he must begin to let it all go.

In King Arc story Black Panther, T’Challa accepts Erik’s challenge to fight for the throne, willing to sacrifice his body to the mortal antagonist but not yet ready to face the true Cataclysm of the deeper spiritual truth about what brought Erik to Wakanda.

Third ActIn story structure, the Third Act represents the final quarter of the story, roughly from 75% through the end. It moves the protagonist into a final confrontation, both inner and outer, to determine whether or not the plot goal will be gained. Sometimes it will be gained; other times, the protagonist will choose to sacrifice the outer goal in order to maintain inner coherence with her newly learned thematic Truth. Although the story may end with the character’s triumph, the Third Act is traditionally a period of darkness, temptation, and sacrifice, as the character struggles to choose between a Want and a Need.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Third Act can be seen to represent the final or elder years of the human life—from 70 years and on. It is comprised of the Crone Arc and the Mage Arc, both of which are focused on the final challenges of life, specifically the character’s relationship to old age and death.

Third Plot Point | Crone ArcIn story structure, the Third Plot Point signals another threshold (another “Doorway of No Return” that mirrors that of the First Plot Point) between Acts. It takes place around the 75% mark and is referred to by such dire terms as the “Low Moment,” the “Dark Night of the Soul,” and “Death/Rebirth.” The events of the Third Plot Point emphasize what is at stake for the character now that she is this deep into her journey. So far, she has risked much and gained much in the outer conflict, mostly thanks to the broadening of her perspective into an alignment with the thematic Truth. But now, if she is to succeed in her goals, she must finally and fully reject every last bit of the limiting Lie she has been carrying with her ever since leaving the Normal World in the First Act. The person she was at the beginning of the story must die, and she must now be reborn into someone new. If she can make that sacrifice, she can move on.

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Third Plot Point equates with the Crone Arc. More than any other of the life arcs, the Crone Arc is focused on the struggle against Death. It is the arc of old age as the character confronts the loss of her temporal power and the looming approach of her mortality. Whether or not she can utilize a lifetime of growth in order to make peace with the nature of Life itself will determine much. She will journey to the Underworld and back to discover whether she can come into alignment with the Truths of her life or whether she will give up on herself—and everyone else—in despair.

In Howl’s Moving Castle (which is a brilliant Crone-Arc-within-a-Maiden-Arc), Grandma Sophie treks into the Waste to try to regain her youth, enters Howl’s Moving Castle, and ends up involved in freeing the Kingdom from a malignant war.

Climax| Mage ArcIn story structure, the Climax begins halfway through the Third Act, around the 88% mark. It usually offers a series of scenes in which the protagonist confronts his final challenges. It ends with the Climactic Moment, which decides the story’s conflict one way or another. In many stories, it is a segment of great excitement and tension. But most foundationally it is a period in which the character puts to use all he has learned in the previous sections of the story. Is all that he has learned truly true—or not? Has he truly changed—or not?

From the perspective of the life arcs, the Climax equates with the Mage Arc. Having overcome the terror and loneliness of the previous arc’s Dark Night of the Soul, the Mage has transcended himself into great and often surprising spiritual power. Having successfully learned the lessons of all the previous archetypal arcs, he benefits from a truly broad and wise perspective of life. He moves through his final challenges and faces his final temptations as much for love of others as for himself.

In Mage Arc story The Legend of Bagger Vance, the title character steps back on the last hole of golf to let his student make his own decision about whether he will win the game by cheating.

***

Now, isn’t that cool? I hope this comparison of how story structure aligns with the archetypal character arcs will help you deepen both plot structure itself and any of the archetypal journeys on which you decide to take your characters (or yourself). Happy writing!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever thought of your life in terms of archetypes and story structure? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypes and Story Structure: How They’re Connected appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 7, 2022

Making Story Structure Your Own

Over the past decade, the term “story structure” has largely come to refer to plot points and beat sheets. When writers start talking about structure, many of us assume they’re talking about the specific and even archetypal shape of story—the rise and fall of plot, the causal balance of action and reaction, the transformational journey of the character.

Over the past decade, the term “story structure” has largely come to refer to plot points and beat sheets. When writers start talking about structure, many of us assume they’re talking about the specific and even archetypal shape of story—the rise and fall of plot, the causal balance of action and reaction, the transformational journey of the character.

Certainly, this is how I think of story structure. Indeed, as regular readers know, much of what I discuss on this site is focused on examining, breaking down, and positing the working parts and patterns found within stories. By this definition, story structure (and its related studies such as character arc) can be wildly exciting since it seems to reveal hidden codes and secrets from out of the body of human storytelling. As writers, this exploration gives us the opportunity to translate our gut understandings of what makes a “good story” into specific and relatable theories. It allows us to look beneath the trappings of stories to the deeper stories underneath, and, more practically, it allows writers to problem-solve our own stories more logically and rationally.

What I talk about on this site and in my books is just my interpretation of story structure. It’s based both on my own experience as a reader and writer, and also on the resonance I’ve felt in response to the insights of many writers and teachers who have come before and who walk beside me. But, again, their insights are also just their interpretations of story structure.

Wild Mind by Natalie Goldberg (affiliate link)

“Structure,” in fact, need not (and didn’t always) explicitly apply to meta discussions of plot mechanics and timing. I was reminded of this in reading Natalie Goldberg’s quirky and wonderful diary of the writing life, Wild Mind (published in 1990). At one point, she offers sound advice on “structure”:

If you want to write a novel, read lots of novels. See what structure the writers have set up for themselves. Look at the length of chapters, who tells the story, what the writers zoom in on, what they leave out. But then you have to tell your own story. What works for you? The structure Mark Twain used to write in is not necessarily the one for you. You are alive now. You can be affirmed and learn from some of Twain’s moves, but you are a different person with your own story to tell.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

When I hear her use the word “structure,” my brain naturally fills in my own personal definition of the word. To me, “structure” means three acts, eight major plot points, and the possible variations of about five different primary character arcs. But however useful that application of the word, it is in itself tremendously limited.

Of course structure is more than just plot beats and timing. By its dictionary definition, structure is a “system of parts” on which something is “built or erected.” So even beyond the varied approaches to structure itself, of course structure may also refer to what I tend to consider the more aesthetic, but equally important, decisions that Goldberg references regarding pacing, POV, and framing, among others.

I don’t bring this up to confuse the issue. Whenever I talk about “structure,” it’s always probably going to be about plot shape and timing. But Goldberg’s musings were first and foremost a reminder to me of how personal my interpretation of story structure is—and, by extension, how personal every writer’s interpretation is.

What It Means to Make Story Structure Your OwnGoldberg prefaced the previous quote by musing:

We should use a structure but make it our own. In other words, each time we write something, we reinvent that structure to fit ourselves and what we want to say. This is not arrogance. We honor structure, but we don’t become frozen by an old one. [An interior designer] couldn’t take down all the walls. The roof would have fallen in on him. But if he was working on a house with a baby room, and the new owners didn’t have a baby, he could reshape that room into another space.

Now, I will note that Goldberg wrote this while she was still working through her first novel. Later on, she acknowledges the primary problem with the book’s first draft was that it was “plotless.” So I daresay she had not yet explored the more technical understandings of story structure, which writers of thirty years later now eat for breakfast. And perhaps this was why she used “structure” as a looser term. She does not seem to be talking about “reinventing that structure” in the sense of coming up with a system that completely replaces the Three-Act structure or its equivalents.

But I think her point is still worth pondering.

It’s true that story structure is one of the cornerstones of story theory. And when approached logically, story structure can seem pretty scientific, objective, and inarguable. But even though the essence of story theory is based on the search for universal (or at least prevalent) patterns within storytelling, every writer’s interpretation and application of these patterns will be subjective, personal, and unique.

This is true when it comes to the type of structure writers identify with, how they interpret it, and even how they define the word “structure” itself.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Certainly, it is true of my own approach to structure. What I teach here on this site and in books such as Structuring Your Novel and Creating Character Arcs is ultimately just my approach. It is the understanding of structure “made my own … to fit [myself] and what [I] want to say.” It is what I have gathered from the story structures of others, pieces that have resonated with me and that have fit within my own personal cosmology of story theory.

When I was younger and stupider, I may have thought, “this is the way to do it.” But now I just think, “this is the way I do it.”

So the real question here is: what’s the way you do it?

5 Questions to Help You in Making Story Structure Your OwnYour story structure might look a lot like mine, or John Truby’s, or Michael Vogler’s. Or not.

Regardless, it is yours. Or should be.

However much we harp on form and style in writing, there is only one metric that matters and that is whatever works. Story theory is nothing more than the examination of what works in an attempt to explain and perhaps replicate it. No one writing teacher or writer has the corner on those explanations or replications. We’re all learning from each other in an endless spiral of growth.

The only right way for you to write a story is your way. Naturally, that way is a process of finding what we resonate with and throwing away what we do not—and perhaps most crucially, learning to listen to ourselves enough to know the true difference. Whatever results is your contribution to the larger revealed study of story theory and structure.

So here are a few questions you can ask yourself to help you in making story structure your own.

1. What Do You Think Works?If the only rule of writing that actually matters is “whatever works,” then what do you think works? What do you feel, deep in your bones, is the essence of story? What is the foundation of a successful plot? What makes characters and their journeys interesting? Which bits of writing advice and structural theories resonate with you? What is the secret sauce that makes your favorite stories work for you?

2. What Patterns Keep Popping Out to You in Other People’s Stories?When we talk about “writing rules,” we’re pretty much always talking about emergent patterns. If somebody suddenly realizes that every great story ever uses the word “be-bop-a-Lula” (that’s a word, right?), then that would be the recognition of a pattern. Next thing you know we’re all telling our spellcheckers to allow “be-bop-a-Lula” and writing excited posts to share the news with our fellow scribes. So what do you see? What patterns can you see emerging from successful story to successful story?

3. What Patterns Keep Popping Out in Your Stories?How about we get even more personal and just take the fast train straight to your own unconscious. If you’ve written (or imagined) more than one story, what patterns can you see there? What are the scenes, characters, or moments that give your heart a little zing? What are the pieces that are making this story work? Right here you’ll find your most personal understanding of structure.

4. What Do You Think Doesn’t Work?Sometimes even more telling than identifying what works is identifying what doesn’t—both in your own stories and in those of other people. It can help to start with a basic theory about what you think does work, then examine any jarring notes to see if they’re jarring because they’ve strayed from your posited pattern of perfection. Ultimately, the whole purpose of story theory as a writing tool is to help us identify what doesn’t work and eliminate it from the process.

5. Why? Why? Why?Every time you ask one of the previous questions, ask this one as least three times. Why does something work? Why does something not work? Why does it seem like certain patterns are emerging? Why might you (or others) be imagining a pattern where it really doesn’t exist? Underneath the why is where you’ll find not just your own take on story structure, but the deeper understanding that will allow you to build upon it (and perhaps share it with the rest of us).

***

At another point in Wild Mind, Goldberg shared that one of the reasons she wanted to move on from poetry to try writing her first novel was that novel-writing was more of a practice and a process. She said:

Poetry is about the divine; a novel is about work and learning to behave.