K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 23

September 6, 2021

Archetypal Antagonists for the Maiden Arc: Authority and Predator

As the first transformational archetype within the “life arcs” cycle, the Maiden Arc is the quintessential “coming-of-age” story. It is the story of teenage angst, the joys and heartbreaks of growing up, and the struggle to individuate into a fully autonomous and mature human being.

As the first transformational archetype within the “life arcs” cycle, the Maiden Arc is the quintessential “coming-of-age” story. It is the story of teenage angst, the joys and heartbreaks of growing up, and the struggle to individuate into a fully autonomous and mature human being.

Like all arcs, the Maiden’s doesn’t just happen. Nor (for all her eagerness to turn sixteen and get her first car) does she necessarily choose it. Although humans can prepare themselves for transformation arcs, we don’t get to initiate them for ourselves. The outer circumstances of our social environment and our own chronological progression through life are major factors in eventually creating the necessary forces to prompt a change arc. These circumstances can be viewed, in many ways, as the antagonistic force that defines both plot and theme in a life arc.

For the Maiden Arc, this antagonistic force can be seen archetypally as the Authority Figures who initiate her transition out of Childhood into the beginnings of a Hero Arc. But within her inner conflict (and sometimes externalized into the outer plot), we can see too that she also faces a frightening Predator—a fearsome guardian that seems to prevent her from passing through the gates of adulthood.

The Maiden’s Antagonists: Practical and Thematic

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

As mentioned in last week’s introduction, there are actually multiple symbolic antagonists that can be seen as important within archetypal character arcs. Particularly, we can usually identify two—one that represents the protagonist’s outer conflict and another that primarily symbolizes the inner conflict. Which is which will largely depend on the unique factors of your particular story.

For the Maiden, these two antagonists are the Authority Figures and the Predator.

Authority as an Archetypal AntagonistSuccessfully initiating into adulthood is not merely a matter of passing through puberty or turning sixteen or twenty-one. On a deeper level, it is an initiation of the soul—a deep transition from the innocence and dependence of childhood into the complexity and responsibility of adulthood. This initiation is, somewhat paradoxically, driven by the Authority Figures in the Maiden’s life.

The paradox lies in the fact that these Authority Figures want the Maiden to undergo her arc and grow up. The Authority Figures are inevitably those who encourage and even demand this transition. And yet, the Authority Figures are also those against whom the Maiden must struggle to “escape.”

It is always possible to represent these two facets of the Authority in different characters—representing the encouraging and initiatory Authority in a wise Parent or Elder, while representing the negative aspect of the selfish or smothering Authority in a shadow archetype such as the Sorceress or Tyrant.

However, I think most of us can recognize how both of these aspects usually reside within the same person. Parents who love their children wish to see them grow into responsible adults, even as there is a part of them that wants to maintain the Child in their care and control.

And so it is important to recognize that although Authority is the archetypal antagonist within a Maiden Arc, the Authority isn’t necessarily opposing her for evil or even purely selfish reasons.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

In the Maiden Arc post, I mentioned that this Authority could potentially be characterized as either the Naïve Father or what Clarissa Pinkola Estés calls the “Too-Good Mother.” What is meant by these titles is that the parents have come to represent within the Maiden’s maturation a stagnation and/or completion of their ability to teach her. Even the best parents in the world will eventually run the course of what they can pass on to their children; at a certain point the Maiden must always strike out to learn for herself.

Of course, this Authority can also be represented by other facets of society, such as teachers, religious leaders, or political figures. It can be represented abstractly by an “institution” or the “system.” And it can even be merely internalized into the Maiden’s own evolving conscience. The loudest authoritarian voice, trying to convince her to remain in ignorance and irresponsibility, may be the voice inside her own head—telling her she doesn’t know what she’s doing, telling her she should just trust in those who know better, telling her she’s better off doing what she’s told. Indeed, this mindset can be the most formidable antagonist any Maiden faces and, if not overcome, can cause a person to remain unindividuated from Authority long into their lives.

The Predator as an Archetypal AntagonistAuthority is the more obvious archetypal antagonist whom every Maiden must face. But there is another important opposing force in her arc: the Predator.

Classically, the Predator is best represented in such tales as “The Seven Wives of Bluebeard” and “The Girl Without Hands.” Both of these stories feature a predatory masculine force that wishes to wed the Maiden. In the former, it is the title character Bluebeard, who notoriously murdered all of his previous wives and kept their bodies locked in a secret room. In the latter, it is the Devil, who chops off the Maiden’s hands when she refuses him.

Symbolically, the Predator represents a seductive but toxic masculine presence. The Maiden, on the cusp of sexual awakening and a whole new world that she does not yet understand, starts out lacking the wisdom to discern between this toxic Predator and the worthy masculine as represented in the Protector.

Although often characterized by a love interest, the Predator’s involvement with the Maiden need not be romantic or sexual. He represents foundationally the alluring dangers of the strange and exciting world “out there.” But in the beginning, the Maiden will not recognize that the Predator is, essentially, an extension of the dark side of that same Authority against whom she struggles to individuate. Should she fall prey to this controlling aspect of the masculine, she will not gain the independence she sought by “marrying” him, but instead will find herself entrenched deeper than ever within the very authoritarian structures she sought to evolve beyond.

It is possible that wise Authority Figures (from whom the Maiden nevertheless still needs to individuate) may recognize the Predator’s threat and offer counsel (at least partially unheeded) against the Maiden’s involvement with him. But as in the above-mentioned folk tales, it is customary that the Authority Figures collude with the Predator’s plan to take the Maiden as wife. This could arise from a selfish desire to bind the Maiden further into their control or to their advantage (such as with Rose’s mother in Titanic, a woman who explicitly opposed her daughter’s individuation by demanding she marry a rich but brutal man), or it could be that the “Naïve Father” and “Too-Good Mother” (such as seen in the story of “The Girl Without Hands” and so many other fairy tales about cursed babies) are simply too foolish or enslaved themselves to recognize or oppose the Predator’s proposal to their daughter.

However, it is also important to recognize that the Predator is ultimately representative of a psychic aspect within the Maiden herself as she undertakes this journey. The Predator is the “inner critic”—the voice inside her young head telling her she is not good enough, smart enough, brave enough to see through the Devil’s tricks and make it through the Wilderness on her own.

In many stories, the Predator may be most representative of the protagonist’s inner struggle against her own insecurities and fears. Growing up, after all, is scary business—and often the dark and dominating parts of ourselves are our most formidable antagonists.

How the Maiden’s Archetypal Antagonists Operate in the Conflict and the Climactic MomentThe antagonist’s most basic role is to generate the plot conflict. The antagonist does this by consistently creating opposition, or obstacles, to the protagonist’s progress toward the plot goal. Via these obstacles, the protagonist is forced to reconsider her mode of being, her belief structures, and her tactics. The antagonist’s opposition forces her to evolve—thus allowing for an externalized story that also creates personal transformation within the protagonist.

In the Maiden Arc, the protagonist’s plot goal may be any number of things (graduating from high school, getting a job, running away from home, staying at home, attracting a love interest’s attention, learning a new skill, surviving a disaster, etc.). But the thematic goal will always be that of growing up, of gaining a certain measure of independence, autonomy, and personal responsibility.

This means the archetypal antagonists within a Maiden Arc are always fundamentally opposed, in some way, to her growing up. It is possible they are aligned ultimately with her maturation (what parent doesn’t want their child to graduate from high school, after all?), but just not the way in which the Maiden is going about it (e.g., maybe she wants to go to a different college than the parent’s alma mater).

What is important is that the protagonist will want something that represents or enables her eventual individuation and initiation into adulthood—and the Authority antagonist is creating obstacles, even if they are well-intentioned (such as Jess’s traditional parents in Bend It Like Beckham, who just want her to be happy and successful in the usual ways for their culture).

The Predator’s presence may be more complicated. Usually, he will act more as a Contagonist—a seemingly wiser Impact Character who appears to offer the protagonist what she’s looking for—a way out of her childhood into a new mode of being. But a true Predator will eventually prove himself also an obstacle to the protagonist’s individuation. She may realize that in order to individuate from the Authority, she may have to individuate from the Predator as well. (Although, as with Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre, it is always possible that the Predator may be redeemed after he recognizes his controlling ways and instead blesses the protagonist’s growth.)

Which of your archetypal antagonistic forces is the true antagonist in your story will depend on which is finally overcome in the Climactic Moment. Usually, the “subplot” antagonist will be overcome previously, but it is also possible that the true showdown in the Climactic Moment will allow for an easy resolution of the secondary conflict afterwards.

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

Unless the Authority in your story is truly malignant (as represented by older shadow archetypes), it is likely the Maiden’s transformation will (in Kim Hudson’s lovely phrase) “renew the Kingdom.” Parents and other Authority Figures will themselves grow through the Maiden’s initiation. They will recognize her as a burgeoning adult and an equal, they will step out of her way, and they will probably bless her future life by wishing her only the best.

In many ways, the Maiden Arc is the most inherently relational of all the life arcs, since its archetypal antagonist is one that, in most humans’ lives, is not corrupted, just restrictive. Authority only becomes the “bad guy” when it is selfishly opposed to necessary growth. Perhaps more than any of the other inherent antagonistic forces, the Maiden’s antagonists offer the opportunity for the strongest growth arcs of their own—as the Maiden’s transformation inspires them to take their own arcs. Indeed, the transformational arc that follows the static archetype of Parent is that of Queen, which is all about growing into a true leadership that allows for and encourages the independence and responsibility of those in one’s charge.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we will study the Hero’s archetypal antagonists of Dragon and Sick King.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcThe Mage ArcIntroduction to the 12 Negative ArchetypesThe Maiden’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Hero’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Queen’s Shadow ArchetypesThe King’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Crone’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Mage’s Shadow ArchetypesIntroduction the 6 Flat ArchetypesThe ChildThe LoverThe ParentThe RulerThe ElderThe MentorHow to Use Archetypal Character Arcs in Your StoriesSummary of the Archetypal Character ArcsArchetypal Antagonists for Each of the Six Archetypal Character ArcsWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of any more examples of the Authority Figure or the Predator as archetypal antagonists? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Antagonists for the Maiden Arc: Authority and Predator appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 30, 2021

Archetypal Antagonists for Each of the Six Archetypal Character Arcs

Antagonists are an interesting consideration for any writer. So often, when we conceive or plot a story, the antagonist may be an afterthought—especially in genre or “plot-driven” fiction in which the antagonist is less likely to be in a relationship with the protagonist and more likely to be a “Big Bad” of some sort.

Antagonists are an interesting consideration for any writer. So often, when we conceive or plot a story, the antagonist may be an afterthought—especially in genre or “plot-driven” fiction in which the antagonist is less likely to be in a relationship with the protagonist and more likely to be a “Big Bad” of some sort.

But in many ways, the antagonist in any type of story is the point. The antagonist is the reason there is a story at all. Without the antagonist—without something to oppose the protagonist’s forward progress or to prompt the protagonist’s growth through the necessity for evolving personal and social paradigms—we don’t have much of a story, do we? At the least, we don’t have much of a transformation.

And so it is just as worthwhile to examine archetypal antagonists as it is archetypal protagonists.

Earlier this year, I shared a lengthy series about archetypal character arcs. This series discussed certain archetypes of positive change, negative regression or stagnation, and “resting” or flat archetypes that intersperse the major transformational cycles of the human life.

Many of these archetypes interact with each other as one another’s antagonists. Particularly, the negative shadow archetypes can often be seen as both the inner and outer antagonists that positive archetypes (such as the Hero or the Queen) may have to overcome in order to complete their own character arcs. Within the series, I also recognized and mentioned, but did not discuss in depth, certain archetypal antagonists that are more abstract and not always characterized as specific human antagonists in the same way as the “negative archetypes.” Early on in that series’ publication, one of you asked that I explore these archetypal antagonistic forces in greater depth—a request for which I am very grateful, as it has prompted me to further exploration and thought on this evergreen topic of archetypal characters and arcs.

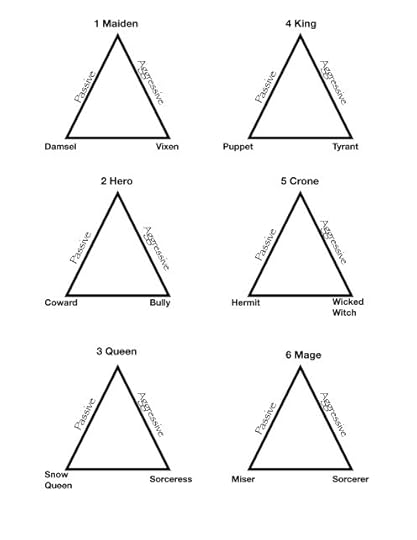

So today, I’m going to kick off a comparatively short (just [!] seven-part) series looking at the archetypal antagonists inherent within each of the six main archetypal “life arcs.” Following is an overview reminder of each of those arcs, as well as the adjoining archetypal antagonists we will be discussing in this new series:

Archetypal Antagonists: Authority and Predator

2. The Hero Arc

Archetypal Antagonists: Dragon and Sick King

Archetypal Antagonists: Invader and Empty Throne

4. The King Arc

Archetypal Antagonists: Cataclysm and Rebel

Archetypal Antagonists: Death Blight and Tempter

6. The Mage Arc

Archetypal Antagonists: Evil and the Weakness of Humankind

In future posts, we will examine each of these more closely in relationship to the specific arcs. For today, I want to start with a quick overview of what these archetypal antagonists represent globally throughout the arcs.

What Is the Difference Between an Antagonist and an Antagonistic Force?One of the reasons I didn’t thoroughly expand upon the archetypal antagonists in the original series was because the overarching thematic antagonists within each arc or journey are clearly abstract forces: Dragon, Cataclysm, Death, Evil, etc. Although they can be personified or anthropomorphized in certain types of stories (e.g., Smaug in The Hobbit or Death in Harry Potter‘s “The Tale of the Three Brothers”), in any “realistic” story, these forces will be symbolically represented by either a mere human, or a human system, or simply an abstraction that is never even named beyond the protagonist’s inner struggle (e.g., the “Evil” faced by Will Smith’s Mage character in The Legend of Bagger Vance is “merely” one man’s loss of meaning and purpose after suffering in World War I).

And this is where it becomes important to distinguish between an “antagonist” and an “antagonistic force.” Defined simply, the antagonist in a story is whoever or whatever consistently creates obstacles between the protagonist and his or her ultimate plot goal. Although the archetypal antagonists we will be discussing in this series are recognized as representing a moral corruption of some sort, the word “antagonist” in itself never indicates any kind of moral alignment. It is possible for the antagonist to be the most moral person in the story and the protagonist the least moral—which is often the case in stories with a Negative-Change Arc protagonist.

Therefore, the antagonist need not be human or even specifically conscious. Generally, the term “antagonist” can be used to distinguish a human (or humanized) antagonist, while the broader term “antagonistic force” can be used to indicate a more abstract form of obstacle to the protagonist’s forward progression.

More than that, it is both possible and prevalent to see a specific human antagonist “representing” a greater and more abstract antagonistic force. For example, in The Lord of the Rings, the Sorcerer Saruman is a proxy both directly (at times) for the greater antagonistic force of Sauron (a barely anthropomorphized representation of Evil) and as a human antagonist against whom the protagonists must do battle.

Antagonistic “forces,” even more than antagonists, have a tendency to be deeply thematic. They may even be nothing more within the story than a representation of the Lie the Protagonist Believes—and which the protagonist must overcome into order to continue down a growthful path. Even if a protagonist must physically defeat a human antagonist in the end, that final outward battle is really only a representation (an externalized metaphor) of the defeat of the greater thematic antagonist. Therefore, it is often useful and even desirable to create a story that offers both an antagonistic force and a specific antagonist to represent that abstract force within the actual plot conflict.

Inner and Outer AntagonistsAs I began thinking about expanding on the archetypal antagonists, I realized all of the six main Positive-Change life arcs offered up inherently archetypal examples of both the thematic antagonistic force (e.g., the King’s Cataclysm) and a more practical plot-based antagonist represented by another character or characters (e.g., the King’s Rebels).

Whether or not you choose to characterize these separately, they offer the opportunity to more thoroughly examine your protagonist’s inner and outer conflicts—and how you can bring them together with cohesion and resonance. As you may have noticed in my above list of archetypal antagonists, I’ve added a few that weren’t directly specified as such in the original series. This is because I’ve put equal emphasis on both types of antagonist for each archetypal arc.

However, which antagonist is represented in the outer conflict and which is primarily a concern of the inner conflict will depend on how you choose to dramatize your story’s theme. For example, in a Maiden Arc, her inner conflict may concentrate on her own internalized sense of Authority while the Predator is externalized (as in Jane Eyre). Equally valid, however, would be the presentation of a disempowering and devouring Predator as her own inner critic, while she faces abusive or restrictive Authority in the external plot (as in Little Dorrit).

Really, they are two sides of the same coin—one representing the other but ultimately both representing the same thematic struggle. The emphasis of one over the other often depends on whether the story itself is more internal and relationship-driven or more external and action-driven. Regardless, your protagonist will confront both, in some guise, in the end. If the external antagonist is to be defeated, it is usually because the protagonist has already conquered the internal antagonist. Or, if the inner conflict isn’t much addressed within the story, then the destruction of the external antagonist can be seen as a metaphor for the character’s internal triumph over the greater antagonistic force.

Antagonists and Contagonists

Dramatica by Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley (affiliate link)

Within the Dramatica system of story theory, Chris Huntley and Melanie Anne Phillips coined the term “Contagonist” to indicate an opposing force within the story who was not as directly opposed to the protagonist as the actual antagonist. Although sometimes the contagonist might be a direct proxy for the antagonist or what John Truby calls a “false ally,” the contagonist is just as likely to be a character who, at least on a plot level (if not a thematic one), is totally separate from the main antagonistic force.

The contagonist is a sort of “subplot antagonist,” one who may be closer to the protagonist than the actual “Big Bad” antagonist and who therefore has more influence over the protagonist’s internal conflict. The Dramatica system contrasts the contagonist with the mentor (in a supporting-character role). Together they act as the competing “devil” and “angel” on the protagonist’s shoulders, each seeking to be the Impact Character who influences the protagonist’s thematic choices and determine whether the protagonist will remain in the Lie or evolve into the Truth.

Although the archetypal-antagonist pairings we will be discussing will not always fall neatly into antagonist/contagonist roles, it is useful to keep this dynamic in mind as another way to examine the greater and more abstract thematic antagonistic force and the nearer and more intimate human antagonists that people your story.

Again, Saruman in Lord of the Rings presents a good example, in that he offers a specific human antagonist who can be seen to fill that role across archetypes, depending on which characters are opposing him: Heroes, Queens, Crones, Mages, etc. For example, he can be seen variously as the Sick King whose realm is dying because of his neglect and whom the “Hero” Frodo must heal, the Tyrant whom the “Queen” Aragorn must replace, and the Tempter whom the “Crone” Gandalf of the Gray must resist.

Saruman is the proxy of the overarching antagonistic force represented by Sauron, but he is also operating on his own account, sometimes even (secretly) in opposition to Sauron. His presence within the story allows the characters to confront different facets and embodiments of the overarching thematic antagonistic force—which would not have been available if they merely faced the Big Bad Sauron.

***

In many ways, understanding your story’s antagonist and/or antagonistic force is the key not just to the plot but to understanding your story’s true thematic significance—whether it is specifically following an archetypal plot or not.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we will examine the Maiden’s archetypal antagonists, Authority and the Predator.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesArchetypal Character Arcs: A New SeriesThe Maiden ArcThe Hero ArcThe Queen ArcThe King ArcThe Crone ArcThe Mage ArcIntroduction to the 12 Negative ArchetypesThe Maiden’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Hero’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Queen’s Shadow ArchetypesThe King’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Crone’s Shadow ArchetypesThe Mage’s Shadow ArchetypesIntroduction the 6 Flat ArchetypesThe ChildThe LoverThe ParentThe RulerThe ElderThe MentorHow to Use Archetypal Character Arcs in Your StoriesSummary of the Archetypal Character ArcsWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you identify any archetypal antagonists or antagonistic forces you have portrayed in your own stories? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Antagonists for Each of the Six Archetypal Character Arcs appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 23, 2021

The Main Reason Your Story’s Premise Is Important

Your story’s premise is the foundation of your work. This is true for the shaping of the story itself, and it is also true from a marketing perspective. For both writers and readers, the premise is the reason we become interested in a story.

Your story’s premise is the foundation of your work. This is true for the shaping of the story itself, and it is also true from a marketing perspective. For both writers and readers, the premise is the reason we become interested in a story.

Even when you don’t know your premise until late in the discovery process (whether that’s outlining or drafting), the premise is still the heart of it all, beating in the background, waiting for you to follow the sound and discover what it’s all about.

Writers often put a lot of pressure on themselves to identify and polish their premises. This is both because stripping a story down to the bare bones of a one- or two-sentence premise is valuable for crafting a cohesive and resonant structure—and also because the premise sentence is often considered one of the key ways of advertising a story and getting people to buy it and read it.

Secrets of Story by Matt Bird (affiliate link)

As a result it can be rather easy to put too much emphasis on the premise itself. After all, it’s just one (or two) sentences. A brilliant premise is no guarantee of a good story. As Matt Bird points out in The Secrets of Story:

Audiences purchase your work because of your concept, but they embrace it because of your characters.

As a matter of fact, I’ve personally found myself increasingly jaded about “good” premises—and by this I particularly mean flashy and high-concept premises. When browsing for new reading or viewing material, I often find myself thinking, Yeah, yeah, that sounds awesome, but is there any substance? (Spoiler: as often as not, the answer is “no.”)

And yet it remains that the premise is a crucial tool in any storyteller’s kit—as long as you understand its purpose and don’t overemphasize its importance in the larger experience you’re trying to craft for readers.

What Is Premise?A story’s premise is simply a brief description of what the story is about. There are different formulae for crafting a premise sentence and different criteria for what should be mentioned (e.g., protagonist, antagonist, plot goal, setting, etc.). I’ve talked elsewhere about how to advance your initial concept idea to a full-blown premise, as well as how to create a one- or two-sentence premise that includes all the necessary information (for both yourself and for potential readers).

Wayfarer (Amazon affiliate link)

Just an example for the post, here is a premise sentence I wrote for my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer:

In Georgian London, a superpowered blacksmith’s apprentice must rescue his master from debtor’s prison before his former mentor, a vengeful politician with a dark secret, can enact his plan to destroy the city’s poor.

Now, aside from the nitty-gritty of what a premise might look like, today I want to answer the question of “what is premise?” by zooming back a bit and looking at why premise is important and how it can function to offer both you and your readers important information about your story.

1. Your Story’s Premise Is a Plot ToolThe premise is first and foremost a tool that can be used either in brainstorming or revising your story. By distilling a story into just one or two sentences, you are forced to identify the bits that actually matter. Any writer who attempts this brain-twister of an exercise will quickly realize most of the story doesn’t strictly matter. Most of the characters won’t be mentioned in the premise; most of the cool flashy bits won’t be mentioned; most of the writer’s favorite scenes won’t even be hinted at.

This doesn’t automatically mean that these bits aren’t important to the story, but it does offer a sobering opportunity to examine what the story is really about underneath all its fuss and bother.

What main conflict provides the structural throughline?Who are the two or three characters who create the main story developments?What is the protagonist really pursuing throughout the story?Whether you’re in the process of outlining, writing, or editing, this exercise can help you gain clarity on a runaway story. It can help you identify and strengthen your main structural and thematic throughline. And it can help you excise empty filler scenes.

2. Your Story’s Premise Is a Marketing Tool

Finding the Core of Your Story by Jordan Smith (affiliate link)

If you’ve done the work of crafting a solid premise sentence during outlining or revising, then you probably already have a handy-dandy log line ready to present to agents and editors, or to include in your marketing blurbs on Amazon and your book’s back cover.

The importance of a solid premise becomes ever more clear when it’s time to use it to convince readers to buy. Especially these days, readers aren’t always going to read lengthy book descriptions before deciding to buy. They may look at your cover, scan a few reviews, and read over the first few lines of description on Amazon (which should be your premise sentence in some guise). Only if they like what they read in the premise will they click “Read More” to get the rest of the blurb.

I see so many blurbs, even on Big-Five books, that fail to present a solidly constructed premise sentence. Although this is no indication that the book itself isn’t solidly constructed, it is unfortunate because so many buyers will blur out during the long and boring sales description and move on to the next flashy cover.

3. Your Story’s Premise Signals to Readers Their Favored Scenes and CharactersLargely, this is why “premise” is such a hot topic among writers. The idea is that you simply must have a unique premise (even though, actually, the emphasis is usually on the concept: It’s Jaws meets Forrest Gump!). But however important a solid premise is to the actual story, the premise itself as a marketing tool is there primarily to indicate to readers that, “Hey, I’m a book full of the stuff you like!”

Most of the time when readers are browsing for new stories, they’re looking for what fits their particular tastes, or even their specific mood at the time. Although a flashy high-concept premise may catch their eye, what they’re really wanting is a premise that indicates it will give them the kind of story they’re looking for.

This is also why genre is such a powerful marketing tool. If readers are wanting romance or for action, they can shortcut the search by looking within a specific genre. But even then, most people are hoping to scratch their own particular itches. Your premise will (or at least should) indicate whether your book is going to do that.

Indeed, a good premise, even in the abstract, provides exactly the same service to the writer—what kind of story do you most like to write?

4 Questions to Discover What Your Premise Says About Your StorySo once you’ve mastered the (not inconsiderable) skill of distilling your story into one or two tight little sentences, how can you tell what your newly-crafted premise is saying about your story? Is it suggesting the right things to the right readers—i.e., is it promising them not just a cool concept but the kind of characters that will make the whole trip worth the time, money, and effort?

Here are four questions you can ask about your story’s premise (or the premise of a book you’re deciding whether or not to read yourself!) to determine whether it’s likely to deliver the goods.

1. What types of characters and interactions are offered by this premise?Remember Matt Bird’s quote at the beginning of the post? Readers don’t care as much about concept as they think they do. In the end, it’s the characters and more specifically their interactions that keep them coming back. Game of Thrones may have gotten optioned because of its premise, but people (mostly) loved it because of its characters.

This is one of the first things I look at when considering a new read. Does the blurb indicate there will be interesting characters? And more importantly will those characters be put into situations where they spark against each other? If the blurb tells me the main character is off on a lonely quest for most of the book, that’s not what I’m looking for. (Although, of course, that may be exactly what some readers are looking for.)

Some readers want power struggles, others want romantic tension, still others want loving family relationships. If your book features any of these, be sure to craft a premise that says so. And if you intended to write a story about such a dynamic only to discover it isn’t showing in your premise sentence, that may be a sign your story got off track somewhere along the line.

2. What themes are implicit in your premise?

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Your premise sentence may or may not explicitly mention the theme. But even if it does not, the themes will still be present implicitly simply through your description of your protagonist’s desires and struggles. Indeed, genre itself is, again, its own shortcut indicator of certain types of themes.

Most readers don’t explicitly pre-judge a book based on what they think the theme is. But they do decide whether or not to read based on their presumptions about a book’s tone—and this is closely tied to theme. If readers want a life-affirming happy ending, or a bittersweet moral victory, or a scathing and tragic social comedy—they’ll instinctively look for that in your premise.

Perhaps even more importantly, they will instinctively reject tones/themes they don’t want to read about. This is a tremendously important factor in hooking up with a satisfied readership. Writers sometimes try to hide the “pointy” bits that some readers may wish to avoid. But, in fact, blatantly indicating those bits in your premise will not only more strongly magnetize readers who are attracted to your subject matter, it will also signal to others that this is a book they’ll probably hate (and that you probably don’t want them buying, reading, and reviewing anyway). In marketing, expectation is everything.

3. What actions and scenes are implicit in your premise?In my experience, high-concept plots are less important than high-concept scenes. I’m far less interested in a hero fighting off giant mutant sharks (although that might get me into the theater… or not) than I am in the entertainment value found in the story’s specific scenes.

We’ve all watched or read stories that sounded as if they should be incredibly entertaining and rewarding—only to have them fall flat from a lack of that substance I mentioned earlier. In fact, high-concept stories can so easily bank all their bets on the concept itself that they fail to properly flesh out a story worthy of it.

When readers read your story’s premise, they’re not just looking for a cool idea, they’re also (at least subconsciously) considering whether this story might offer them the kind of scenes they’re hoping for.

Read your premise sentence as objectively as you can. What kind of scenes and action (whether shoot-em-ups or Regency dancing) does this premise seem to indicate? Do you actually take advantage of those scenes in the story? If your premise promises an awesome hero with unique abilities, does your story not only show those abilities but also use those abilities in the absolutely most entertaining way possible?

4. Are you taking full advantage of all your story’s premise’s implicit promises?Like all of your story’s marketing, including its cover, your story’s premise is, in fact, foreshadowing. It offers promises to your readers. Some of those promises are explicit. Some are implicit. But like any good foreshadowing, whatever you plant must be paid off.

One of the chief reasons for negative reviews is the disconnect between what readers were led to believe in the marketing and the story experience they actually had. Now, granted, some of that disconnect may merely be that the reader felt promised quality storycrafting and was not given it. But often the most disappointing story experiences are those in which the writing was great, but the story itself didn’t fulfill its premise.

Sometimes this is because the premise sentence was poorly crafted and did not properly represent the true story. But sometimes it is because the writer thought the premise was being fulfilled within the book itself—but it was not.

***

The importance of your story’s premise should not be overestimated. But neither should it be underestimated. You can use your story’s premise to help you outline, draft, and revise a better story—and then to guide the right readers into fully enjoying everything you have created for them.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is the first thing you look for in a story’s premise—whether your own or someone else’s? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The Main Reason Your Story’s Premise Is Important appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 16, 2021

Why You Should Always Identify Characters Pronto

Note: I’m taking a break this week, so am posting this shortie instead of the usual post and podcast. Enjoy!

Note: I’m taking a break this week, so am posting this shortie instead of the usual post and podcast. Enjoy!

As the author of your story, you not only understand everything that’s going on, you’re also able to see behind the curtains. You understand even those intimate and intricate gears and switches that readers will never see. Possessing this inside knowledge is essential for crafting a deep and dimensional story. However, don’t lose sight of the gap between your own implicit knowledge and that of readers. Otherwise, you risk confusing them by assuming they know things they do not. This will destroy their suspension of disbelief and eventually risk the loss of their attention altogether.

For example, in a generational saga I once read, the author opened almost every scene with a pronoun. He apparently expected readers to instantly comprehend which character the pronoun referred to, so they could orientate themselves in the POV and the setting. But that isn’t quite the way it worked. Since the story featured half a dozen main characters and skipped through large chunks of time and space, readers were left grasping, skimming, and skipping ahead to figure out what was going and which character was being referenced

In your own story, you, as the author, may know exactly to which character each pronoun refers. But don’t make things unnecessarily difficult for readers for no good reason. Introducing characters by name—and even a brief description by way of reminder if necessary—is a simple courtesy that will ensure readers are never yanked from your narrative by the need to hunt down antecedents.

The post Why You Should Always Identify Characters Pronto appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 9, 2021

3 Things to Know About the Ending of a Story

There are three parts of a story that are difficult to write: the beginning, the middle, and the ending. (I was going to start the article by referencing the ending of a story as one of the hardest parts, but then I realized… it’s all hard. Ahem.) Each has its own special set of challenges, but today I want to talk specifically about the function of a story’s ending and a few points that sometimes cause confusion and/or are taken for granted.

There are three parts of a story that are difficult to write: the beginning, the middle, and the ending. (I was going to start the article by referencing the ending of a story as one of the hardest parts, but then I realized… it’s all hard. Ahem.) Each has its own special set of challenges, but today I want to talk specifically about the function of a story’s ending and a few points that sometimes cause confusion and/or are taken for granted.

Whether or not a story works is dependent on how well its beginning, middle, and ending hang together. Are they all of a piece? Does the beginning ask a question that the middle develops and the ending resolves? When viewed in this manner, it is quite clear that all three parts are equally important. And yet it is difficult not to be inclined to give the ending special status. After all, the ending is what “proves” the story, right?

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Indeed, the ending—and particularly the Climactic Moment that decides the plot conflict—can function as a confused writer’s guiding light in figuring out just what the story is about and how to wrangle its unwieldy earlier sections. For instance, I often talk about how the Climactic Moment can be used to determine:

What your story is about.Who your story’s protagonist is.Whether your story offers a cohesive plot.Whether your story offers a resonant theme.This is because we never really know what a story is about until we reach the ending. Regardless what has come before, the ending provides the final commentary. The ending is what indicates whether the author finds this story’s series of events to be tragic, comedic, triumphant, ironic, or even unclear.

This is, of course, one of the reasons it can be so helpful for writers to have a good idea of their endings before they start writing. If you know what you’re building toward, it’s much easier to construct a resonant path toward that ending. (Although it is, of course, an equally valid approach to use your first draft as an exploration of what you want your ending to say.)

However, it is important to keep in mind that this view of the ending or the Climactic Moment is the writer’s view. It is a meta, zoomed-out, big-picture, Creator view of the unfolding drama. This is not the view of the readers or the characters. For them, the ending is less a destination they are moving toward and more properly an emergent of the story’s many adventures and travails.

This is an important distinction. Recognizing it not only facilitates an avoidance of the kind of formulaic stories that produce formulaic endings, it also presents a more accurate reflection of how life actually works. Although all of our lives—and indeed perhaps Life itself—will reach an ending, none of us know what that ending will be or what it will “say” about the story that has come before. Even if we, like our characters, are working toward a specific end (HEA, of course), that ending is less the final triumph (or failure) of a goal and more the inevitable emergent of all the many scenes and events that have unfolded leading up to it.

The Tremendous (But Sometimes Misunderstood) Significance of the Climactic Moment in a Story’s Ending

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Because I am an outliner who finds value in knowing the ending of my own novels before I write them, and because I so often discuss the entire shape of story here on the blog, I always emphasize the importance of the Climactic Moment (for the reasons mentioned above). But today, I want to step back a little and look at the Climactic Moment as it truly is—less as the final effect in a causal progression of plot and more as the inevitable emergent from a systemic progression.

1. The Climax Proves the Story’s Change, But Does Not Create ItIt’s easy to view the Climax—where the story’s plot conflict is decided in or against the protagonist’s favor—as being the moment when everything changes for the protagonist. Before the Climax, he was a loser; afterwards, he’s a hero. Before the Climax, she didn’t have a job; afterwards, she does. Before, the Climax, he hadn’t rid the world of the bad guy; afterwards, he has.

However, although the Climax enacts a final causal change, it is itself the result of the story’s systemic change.

Causal change is that of a single factor (the cause) creating a single new outcome (the effect). This is a useful understanding of a story’s events, as far as it goes. But of course, like life, things are actually a bit more complex.

On the other hand, systemic change is that which is created by multiple causes. You can think of the difference between casual change and systemic change like this:

Causal change is like a single row of dominoes, in which one domino knocks into the next, creating a long row of causes and effects.

Systemic change is like an elaborate pattern of dominoes set up so that a single domino may knock into multiple dominoes and end up setting off a chain reaction that knocks over a multiplicity of dominoes.

Your story’s Climax is a causal domino—a single event that creates a single change (the protagonist becomes a hero, gets a job, offs the bad guy). But it is also an emergent from the larger systemic pattern of falling dominoes, which was triggered by earlier events in the story.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

In short, if your protagonist is going to end the story as a hero who is capable of defeating the antagonist, that is not a change that is suddenly enabled in the Climax. If it is, then you’re asking your Climax to carry far too much weight, and your character’s transformation is likely to feel flimsy and unconvincing.

Rather, the outcome of the Climax is in many ways the inevitable emergent of all the “mini” changes created by your protagonist’s choices throughout the story.

2. The Destination Is Not the Point, the Journey Is the PointHere’s an interesting question to ask yourself: At the beginning of your story is your protagonist capable of performing the story’s climactic action?

The answer is probably yes.

For example, is Elizabeth Bennet physically capable of telling Mr. Darcy she’ll marry him?

Is Frodo physically capable of throwing away the Ring?

Is Sam Spade physically capable of solving the mystery and calling the police with the truth?

Resource and setting challenges aside, the answer, of course, is yes. So why bother to tell a 300-, 400-, 500-page novel? Why not save time by simply mentioning (in the style of the 2003 adaptation of Peter Pan) that there was “slashing and killing and it all ended happily ever after”?

The answer, of course, is that the ending is not the point. Even when readers are uncertain how a story will end, even when they are hoping to be surprised, they are not reading for the ending. If the ending defines the story, the story also defines the ending.

This is because skipping to the end, without the journey in between, is deeply unsatisfactory based on the fact that this is not how life works. More particularly, this is not how change and transformation work.

The hero is not a hero just because he reaches the end, but because of everything he did to get there. It is the difference between a visual culmination of a goal and an embodied one.

This is why, when we seek change in our own lives, just “doing the thing” doesn’t always get us the results we may want. Getting a new job, getting married, having children, moving to a big house—sometimes these goals fall flat because we put too much emphasis on the ending instead of arriving there in an organically emergent way. It’s like yoga: you and I both could probably look up some crazy pose on the Internet right now and force our bodies into it. Hooray, we’re yoga masters! Except, of course, we’re not. Potential injuries aside, we haven’t done the work to truly embody that pose. Therefore, not only do we fail to gain its true benefits, we also fail to learn what it has to teach us along the way.

It is important to remember that although a story must reach an ending, that ending is only important in the context of the protagonist having earned it through the journey. Lizzie Bennet could have accepted Mr. Darcy on his first proposal, but would they have been happy together—would they have become the epic lovers we now see them as? Frodo could have had the eagles fly to him to Mt. Doom in the first book and plopped the Ring in the fires before it properly had a hold on him, but would that ending have been anywhere near as powerful without the long pages of suffering he and Sam went through to get there? (For that matter, would the ending’s surprise of who actually destroys the Ring have been as resonant?)

In short, don’t rely simply on the events of your Climax to prove that your protagonist has changed. The Climax is merely there to give the protagonist a final stage on which to fully embody the change he or she has already earned.

3. The Ending Both Is and Is Not the Most Important Part of the StoryWe often hear that the ending of a story is the most important part. In some ways, obviously, it is.

The first chapter sells the book; the last chapter sells the next book.–Mickey Spillane

Implicit in this idea is not so much the notion that your ending must be slam-bang, but more that the ending is what proves whether or not the story as a whole works. After all, I daresay we’ve all thrown a book or the TV remote across the room in disgust when a malapropos ending made us feel we’d wasted time on a story that, up to that point, we quite liked.

Somewhat counter-intuitively (or at least counter to lots of writing advice), the importance of an ending is not its ability to surprise us, but rather its ability to satisfy us. This is why we can and will return again and again to experience old stories whose endings we already know. Indeed, sometimes once we have initially experienced the ending and realized what a satisfying story it has produced, we will enjoy subsequent experiences of that story even more than the first time.

No less than the beginning or the middle, the ending is a crucial part of your story to get right. But part of that “rightness” is in seeing it as an emergent of everything that has come before, rather than as the final change in the characters’ world.

This mirrors another truth back to our readers, and that is that simply knowing how a story should end, or what the goal is, or the steps to “being a hero” is not enough to get there in a truly embodied way. Just doing the thing is not the same as living the journey. Lizzie and Frodo and Sam all know this.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you know what will happen in the ending of a story you’re currently writing? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 3 Things to Know About the Ending of a Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 2, 2021

How the Antagonist Functions in Different Types of Character Arcs

Most of the time when we think about a story’s antagonist, we simply think of the “bad guy.” The antagonist is the character (or force) that opposes the protagonist’s forward progression in pursuit of the main plot goal. This is fundamental plot theory, linked to the old saw about “no conflict, no plot.” The antagonist creates that conflict by presenting obstacles to the protagonist’s easy forward momentum. When the protagonist finally overcomes those obstacles, the conflict ends and so does the plot.

Most of the time when we think about a story’s antagonist, we simply think of the “bad guy.” The antagonist is the character (or force) that opposes the protagonist’s forward progression in pursuit of the main plot goal. This is fundamental plot theory, linked to the old saw about “no conflict, no plot.” The antagonist creates that conflict by presenting obstacles to the protagonist’s easy forward momentum. When the protagonist finally overcomes those obstacles, the conflict ends and so does the plot.

But the antagonist is not merely a static force of opposition. Because every story is defined by the protagonist’s character arc, the antagonist’s role will vary depending on the nature of the protagonist’s own journey. If the protagonist’s personal character arc, as linked to the plot progression, is a Positive-Change Arc, then we generally recognize that the story itself is positive, even if it ends otherwise tragically. If the protagonist presents a Negative-Change Arc, we recognize the story as tragic, usually in the external conflict as well as the internal. And if the protagonist demonstrates a Flat Arc—which essentially inspires the (usually) Positive-Change Arcs of supporting characters—we also generally experience the story as positive.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Depending on which of these general arcs your protagonist “proves” by the end of the story, the antagonist will play a corresponding role. To create a fully functioning storyform, in which the external and internal stories (essentially, the plot and the theme) pull together, it is necessary to recognize that the antagonist’s orientation to the protagonist and to the thematic Truth at the heart of the protagonist’s arc will not be arbitrary.

Although an antagonist can follow a character arc of his or her own, the antagonist’s role within the story must function in direct correspondence to the protagonist. In short, the antagonist must function to oppose the protagonist, thus creating the necessary conflict in the plot and the forthcoming inner friction within the protagonist’s own evolution.

Many writers believe the antagonist’s arc should simply be opposite to the protagonist’s. For example, if the protagonist demonstrates a Positive-Change Arc, the antagonist should demonstrate a Negative-Change Arc. Although a sound principle underlies this idea, it does not, in itself, get at the true function of the antagonist or, for that matter, the protagonist.

Put simply, a story is always about two opposing forces—an element that seeks change and an element that resists it.

Almost always, the element of change is heroic, while the element resisting it is adversarial. This is why character arcs (and stories in general for that matter) are always about change. This is what defines character arcs and makes them work.

However, it is important to note that the change represented in Negative-Change Arcs is always regressive. It does not represent a heroic willingness and courage in moving forward into necessary evolution, as do the Positive-Change and (in a different way) the Flat Arcs. Rather, the Negative-Change Arc represents not only a refusal to enact necessary and heroic change (either personally or socially) but instead either a stubborn resistance to such change or an attempt to reverse previous changes and revert to a former way of being.

For all its simplicity, this is a complex understanding of story. It is predicated upon the idea that change is always necessary, but it is complicated by the reality that change is not always effective. Therefore, a person who resists change can simultaneously represent an antagonistic obstacle to heroic change and a voice of wisdom.

Right away, we can see opportunities for not just fleshing out antagonists (and protagonists) but also for exploring the central conflict of story as a deeply transformative question that always reflects upon life itself, no matter the story’s actual scope or events.

Today, let’s take a brief look at how you can use this simple equation (enactor of change vs. resistor of change) to strengthen your protagonist and antagonist’s relationship in any type of story.

Positive-Change Character Arc: The Antagonist as AdversaryHere we have the classic story set-up of a heroic protagonist against a villainous antagonist. The protagonist represents the good guy, if only in the sense that the protagonist is willing to confront a problematic reality and attempt to change it. Likewise, the antagonist represents the bad guy, if only in the sense that the antagonist is unwilling to confront this same evolving reality by changing accordingly—and as a result he either acts as an obstacle himself or purposefully creates obstacles for the protagonist.

This is an obviously simplistic approach that in no way accounts for or precludes the individual nuances of the characters. Just because the protagonist is predisposed to accepting the need for change, this does not mean she is instantly heroic. Indeed, the entire point of a Positive-Change Arc is that the protagonist only slowly accepts the need to release an old view of reality (the Lie the Character Believes) and embrace a new and more effective one (the thematic Truth).

By the same token, the antagonist in a Positive-Change Arc story need not be blindly and absolutely opposed to change. What is important within the scope of the story is that the antagonist represents an adversarial obstacle to the protagonist’s story-specific change.

We see this represented in all sorts of stories, everything from blatantly symbolic clashes of good and evil, right down to Bildungsroman stories about up-and-coming young protagonists who may or may not succeed in overthrowing existing establishments (which, indeed, may or may not need overthrowing, as in the case of, say, an established newspaper adapting to the Internet age).

In these stories, the protagonist may or may not be obviously heroic, just as the antagonist may or may not be obviously adversarial. What is important is simply the recognition that any character following a Positive-Change Arc represents humanity’s heroic potential simply through the willingness to embrace change—even in the face of resistance from another.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

The antagonist may represent Joseph Campbell’s tyrant “Holdfast”—keeper of the status quo who refuses to allow the protagonist or society in general to adapt to inevitable and necessary change. But the specific character will not necessarily be blind, stupid, stubborn, or tyrannical. Indeed, the character may represent an aspect of reality that needs to be currently preserved in general but not specifically for the protagonist.

We can see this in many coming-of-age stories in which parents or other authority figures represent the adversary to a “heroic” protagonist who is in the process of growing up and individuating. With a few obvious exceptions, we recognize that these older characters are not villainous in any way but simply enacting prescribed and necessarily limiting social boundaries—which the protagonist is now outgrowing.

Indeed, people need other people against whom to push and struggle and grow. Even if the other person is not quantifiably “wrong,” he or she represents to us an opportunity to grow.

Just as suggested by David Emerald’s Empowerment Triangle (which offers several implicit character-arc opportunities), an Adversary is very often a Challenger, and therefore one’s greatest teacher.

The Negative-Change Character Arc: The Antagonist as HeroNegative-Change Arcs are always interesting in that they subvert the ideal of protagonist as hero. Instead, these arcs explore a story in which the protagonist is a character who blocks healthy change and growth and instead either clings to the status quo or reverts to an outmoded belief.

The Negative-Change Arc features a protagonist who fails to courageously embrace a necessary new view of reality (the thematic Truth) and instead stubbornly clings to or even reverts deeper into a now-outdated view (the Lie).

As a result of this heroic failure (and in some cases outright cowardice), the protagonist will experience tragic personal consequences and will likely inflict similar tragedies upon the story world around him.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, the antagonist in these stories is the one who represents the heroic proposition. As in any story, the antagonist is the character who opposes, resists, and creates obstacles for the protagonist. When the protagonist is the one resisting forward change, the antagonist will be the one challenging this approach.

Very often, this means the antagonist in a Negative-Change Arc will be the “good guy”—the detective trying to take down the corrupt mob boss or the concerned family member trying to save a loved one from an addiction.

Whether the antagonist will be able to overcome the protagonist’s resistance to necessary growth will depend on the specific story. The author may wish to underline the true tragedy of the protagonist’s negative choices, in which case the antagonist’s heroic efforts will fail. Or the author may choose to emphasize the importance of transformative courage to contrast the story’s in-depth exploration of the protagonist’s destructive refusal to embrace a truer and broader reality. In this case, the antagonist may “win” in the end, while the protagonist ends tragically on a personal level by suffering the consequences of her actions.

The Flat Character Arc: The Antagonist as Either Adversary or StudentIn a Flat Arc, the protagonist is, in fact, at his most heroic. Unlike the Positive Change-Arc protagonist, the protagonist in a Flat Arc is not waging a personal internal war between Lie and Truth. Remember, the Positive-Change protagonist is trapped between her own potential for either courage or cowardice. She chooses courage (and therefore change), but not until the end. By contrast, the Flat-Arc character is essentially the sequel to the Positive-Change Arc.

This is a character who has already come to peace with and now represents a brave new viewpoint, which is needed in order to positively transform the story’s external reality. The Flat-Arc protagonist does not personally change over the course of the story (at least not in relation to the central thematic Truth). Rather, the Flat-Arc protagonist is a catalyst for change, representing a call to transformation for the supporting characters.

In these stories, some of the supporting characters will answer this call and be positively transformed into heroically facing the new paradigm represented by the protagonist. Others from among the supporting characters will resist this change, choosing to cling to the thematic Lie and falling into regressive negative patterns.

Your antagonist in a Flat-Arc story can potentially fall into either category. It depends on what type of story you are telling and specifically what type of Truth the Flat-Arc protagonist represents.

If the thematic Truth will require broad social change (on the scale of the community on up), then the antagonist is likely to be an adversary—a person or force who outright resists the need for and the enacting of a new paradigm.

If, however, the story is “smaller” and more relationship-focused, it is possible that the antagonist may instead be a character who is in fact on a Positive-Change Arc. This character will initially resist the protagonist’s Truth, but will eventually overcome her own personal Lie and embrace the change. This is very often the paradigm for romance stories, in which one lead character follows a Flat Arc that constructively impacts the other lead’s Positive-Change Arc. By “meeting” each other within the story’s thematic Truth, they are then able to create a mutually beneficial relationship.

Particularly in some stories with unchanging Flat-Arc protagonists, it is possible to see antagonists who initially seem to be more progressive in their desire to embrace change than is the protagonist. At first glance, this would seem to indicate these antagonists are more heroic than the static protagonists. However, a closer look shows that the change these antagonists are trying to enact is, in fact, not progressive but regressive.

A good example is Thanos is the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Unlike many, he possesses the ability to recognize the untenability of the universe’s overpopulation and therefore the need for a new “Truth” that would accept, adapt to, and address the problem. At first glance, this perspective seems more forward-thinking and progressive than that of the story’s heroes (who aren’t even thinking about these problems). But Thanos proves himself an adversary in that his solution is to regress to a previous “Truth” by massacring half the population.

***

Stories work best when their underlying pieces are placed in direct relationship with one another. Fortunately, these fundamental pieces are very few in number: really, there is only the protagonist and the antagonist. Once you understand their relationship to each other within various types of story, you can successfully build compellingly dimensional characters upon their foundations.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your antagonist’s role in your protagonist’s character arc? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How the Antagonist Functions in Different Types of Character Arcs appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 26, 2021

Should You Edit As You Go?

Should you edit as you go? This is a question just about every writer asks at one point or another. Part of the reason for the prevalence of the question is that the question is in fact complex and contextual. In short, the answer to “should you edit as you go?” isn’t always a simple yes or no.

Should you edit as you go? This is a question just about every writer asks at one point or another. Part of the reason for the prevalence of the question is that the question is in fact complex and contextual. In short, the answer to “should you edit as you go?” isn’t always a simple yes or no.

Popular advice usually insists, “Never edit as you go.” Sometimes this is the most advantageous approach. Other times, however, refusing to edit as you go can lead to a hot mess of a first draft that lands somewhere between “this will take me the rest of my life to fix” and “this is unsalvageable.”

But if you choose the other fork in the road and do allow yourself to edit as you go, you may equally find yourself forever stuck in a morass of perfectionism, in which you never get to have the fun of actually writing and moving your story forward.

Personally, I do edit as I go. I’ve taken this approach on every novel I’ve ever written, and it has served me well. Not only does it lead to cleaner first drafts that require fewer edits at the end, it also helps me course-correct stories as quickly as possible. The alternative, often, would be to knowingly write a broken first draft. For some that might work; for me, it seems like pointless torture.

But I’ve come to recognize that whether or not editing as you go is really the best choice has much to do with each writer’s personal process—which is based on that individual’s personality, strengths, weaknesses, and even unique lifestyle demands.

Should You Edit As You Go? Three AnswersAlthough the decision of whether or not you should edit as you go is certainly not as black and white as I’m about to present, I do think that if you can identify what kind of writer you are, you will be able to make a more informed decision about what kind of editor you are.

In general, the question of editing as you go has to do with whether you most enjoy being a “plotter,” a “pantser,” or a “plantser.”

Answer #1: Yes, You Should Edit as You Go (or, the Structured Approach)

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Are you an outliner, a plotter, and a planner? Are you someone who prefers to know the story before you sit down to write the first draft? If so, editing as you go is very likely your best choice.

For an outliner, an extensive and thorough outline can in many ways be considered the first draft. It is the part of the story where the brainstorming and discovery happens. It’s the raw, sloppy, vulnerable bit where the story is revealing itself to you.

It is also, of course, a time of organization, when you rationally examine the emerging plot to make sure it works. You’re taking time upfront to do your best to ensure all the important story pieces are in place. Ideally, this means that when you start writing the first draft, you will have an accurate road map to lead you through the story, scene by scene.

Of course, there will still always be detours. What Dwight D. Eisenhower said about battle is equally true of writing fiction:

In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.

Depending on how successfully you constructed your outline, you should ideally have very few major changes to make by the time you start writing the first draft. Those changes that do need to be made are often less about major plot or character alterations and more about minor tweaks—such as setting changes or the like.

As such, editing as you go when you’re an outliner means you’re less likely to be tempted into derailing your forward progress. Rather, editing as you go becomes more about systematically straightening up after yourself.

Personally, I edit every previous day’s writing before moving on to the next bit. I also consciously take a break after every major structural beat and read over the entire manuscript so far. I call this the “50-page edit,” but that number really depends on how long the book is. If you write lengthy fiction, as I do, stopping every eighth of the book (aka, after every major structural beat) is helpful for re-orienting yourself in the details of your story. But if you’re writing something shorter, you may only need to stop once or twice throughout the process—or not at all.

Unless an outline proves to be fatally flawed, this approach usually leads to solid first drafts that require little major structural editing by the end.

Answer #2: No, You Shouldn’t Edit as You Go (or, the Discovery Approach)Are you someone who “writes by the seat of your pants,” spontaneously reacting to your inspiration by exploring it through your own prose? Do you prefer to do your brainstorming in the first draft itself, rather than in an outline ahead of time? If so, editing as you go may not be your best option.

“Discovery writers,” or “pantsers” as they are sometimes called, often feel stifled by outlines. The idea of logically planning your way through the entire story before you write it can seem both daunting and disheartening. If your favorite part of the process is the writing—the wild whirl of creativity as you wait to see what happens next—then imposing order and organization onto your story too soon can rob you of both inspiration and motivation. You will almost certainly still need to impose logic and order on your story at some point, but you may be better off waiting until the revision stage instead of doing it ahead of time in an outline.

Because the flow of inspiration is so important to this type of process (and because it is accepted that the first draft will be comparatively messy), it can be counter-productive to stop and edit as you go. Indeed, stopping to review all of the manuscript’s current problems can not only derail you into making corrections before you’re ready but can also discourage you from finishing at all.

The more logic-based parts of storytelling—i.e, outlining and editing—use different brain functions than do the more creativity-based parts—i.e., brainstorming and immersive dramatic writing. Although we can and do switch back and forth between these functions all the time, often we’ll get the best results by isolating our efforts. Indeed, this is exactly why outlining works best for me. It lets my logical brain put to rest as many of the logical problems as possible, so I don’t get distracted while bringing the first draft to life during the creative phases. It just depends on how your brain works and what you enjoy most.

If you know you write best in a creative flow and that this creative flow needs to be protected from your more rational, perfectionistic urges, then you may be wary of falling down the rabbit hole of editing as you go. After all, when there’s a sign that says “Here Be Dragons,” it’s probably best to heed that.

Answer #3: Maybe You Should Edit As You Go (or, The Figure-It-Out-As-You-Go Approach)Honestly, I rather think this is the answer that applies to all of us because no matter how inveterately we identify with one side or the other of the plotter/panster polarity, we all have to employ all the skills of a writer at some point or another. Those who do this most naturally sometimes call themselves “plansters”—a mix between plotters and pantsers.

If this is you, then you may want to plan some things about your story upfront, but not necessarily every scene. Or you may outline a few scenes, write them, then outline a few more. Regardless your specific preferences, you are probably a generally more flexible person. You’re likely comfortable with both structure and unleashed creativity. This means your best relationship to editing as you go will also likely be pretty flexible. Sometimes editing as you go will be the best fit; other times, not so much.

Again, this is really true of all of us. There have been times in my own writing history when stopping to edit has admittedly been just a procrastination technique so I didn’t have to do the hard work of actually writing another chapter. Similarly, for discovery writers there can sometimes come a moment when they know the story is such a wild mess they simply can’t bear to keep going without first cleaning up after themselves.

This points to how there really is no one size fits all answer to the question of whether or not it’s best to edit as you go. We can listen to the common bits of advice floating around out there, but each of us must decide our own best course based on personal experience and self-knowledge.

Finding Your Own Process (or, Know Thyself)When we ask “Should I edit as I go?” what we’re really asking is “Is this going to trip me up—one way or another?” As you can see, that answer varies wildly. Editing as you go can be either a great boon or a tremendous stumbling block. Whichever is true for you depends largely on where your own personal strengths and weaknesses fall within the writing process.

Ask yourself:

In what part of the writing process (plotting, drafting, or revising), do you naturally have the most enjoyment and discipline?In what part of the process do you naturally have the least enjoyment and discipline?Which do you feel is more likely to discourage you from finishing your first draft: stopping your forward momentum to edit for a while, or plowing ahead when you know there are problems behind you?How judgmental of yourself and prone to perfectionism are you? If you go back to identify problems, will it rob you of the necessary motivation to finish the first draft?How capable do you currently feel of fixing your first draft’s problems? Can you fix them quickly, or will you get sidetracked by trying to figure out what the problems are?How much discipline and enjoyment do you have in the revision phase? Do intense revisions overwhelm or excite you?There is no perfect process. If you’re going to write a book, you’re going to have to do the bits you dislike just the same as the bits you love. You’re also, inevitably, going to run afoul of discouragement, inertia, and confusion at some point (probably many points). That’s just part of the wilderness adventure that is fiction writing.

You may well need to experiment a bit before you discover your best relationship with editing as you go. Get familiar with the warning signs that your motivation and discipline are flagging and use that as a gauge for when stopping to edit will help you and when it will hinder you.

At the end of the day, there is no right answer, even just for one person. There will be times when you’ll edit as you go and times when you won’t—and times when you should or should not and miss the signs. Whatever your decision, it’s always reversible. Pay attention to what writing environments create your best work, and listen to you own creative signals to help you find the answer to this question on a daily basis.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you usually edit as you go? Why or why not? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___