K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 26

February 8, 2021

Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 1: A New Series

Archetypal stories are stories that transcend themselves. Archetypes speak to something larger. They are archetypal exactly because they are too large. They are larger than life. They are impossible—but ring with probability. They utilize a seeming representation of the finite as a mirror through which to glimpse infinitude.

Archetypal stories are stories that transcend themselves. Archetypes speak to something larger. They are archetypal exactly because they are too large. They are larger than life. They are impossible—but ring with probability. They utilize a seeming representation of the finite as a mirror through which to glimpse infinitude.

Despite their almost numinous quality, archetypes are a very real force in our practical world. Think of it this way: all the things we imagine actually exist. Aliens. Vampires. Dragons. Fairies. All the memories of our actual reality also exist—in real time—in the same way. Regardless whether these things can be proven as corporeal, they still exist within the human experience and impact it. The deeper the shared belief, the deeper and more meaningful the archetype becomes.

Stories are one of our most powerful modes of exploring archetypes. This is true, as we’ve talked about elsewhere, in the very nature of story itself and more specifically in the patterns of plot and character arc structure that are revealed in the studies of story theory. But archetypes show up in a legion of increasingly smaller ways—from genres to iconic character types to symbolic imagery.

For a writer, one of the most exciting explorations of archetype can be found within specific character arcs—or journeys. These arcs have defined our literature throughout history, and they can be consciously used by any writer to strengthen plot, identify themes, explore life, and resonate with readers.

The Six Archetypal Character Arcs (or Journeys) of the Human LifeWith today’s post, I will be beginning a lengthy series that will start by exploring six particular Positive-Change character arcs. They are:

1. The Maiden

2. The Hero

3. The Queen

4. The King

5. The Crone

6. The Mage

These archetypes are not random but sequential, marking out what we might see as the Three Acts of the human life. If we think of the average human life as lasting 90 years, then we can also think of that life in terms of Three Acts made up of 30 years each.

The First Act—or the first thirty years—is represented by the youthful arcs of the Maiden and the Hero and can be thought of thematically as a time of Individuation.

The Second Act—roughly years thirty to sixty—is represented by the mature arcs of the Queen and the King and can be thought of thematically as a time of Integration.

The Third Act—roughly years sixty to ninety—is represented by the elder arcs of the Crone and the Mage and can be thought of thematically as a time of Transcendence.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estes (affiliate link)

In her book Women Who Run With the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Ph.D., alludes to how these six archetypes (although she uses different names) are foundational to the human experience:

The gardener, the king, and the magician are three mature personifications of the archetypal masculine. They correspond to the sacred trinity of the feminine personified by the maiden, mother, and crone.

For the purpose of our study, it is important to note upfront that each of these six character arcs will build upon the previous ones to create the big picture of one single “life arc.” The partner arcs within the same act are not interchangeable but distinct (i.e., the Maiden and the Hero are not simply gendered names for the same arc) and can be undertaken by any person of any gender (or age). (See point #5 at the end of the article.)

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Each of these archetypes represents a Positive Change Arc (such as I talk about in my book Creating Character Arcs). Later we will also be examining the Negative Change Arcs represented by the passive/aggressive archetypal poles for each type (e.g., the Bully and Coward as the negative aspects of the Hero), as well as the Flat Arc periods that exist between the Positive-Change Arcs (e.g., the Lover, the Parent, the Ruler, etc.).

The “Problem” With the Hero’s JourneyAlthough all of these archetypes are deeply familiar to us, only one—the Hero—is noted for having a prominently recorded archetypal journey. Most writers these days are steeped in the mythology (both ancient and modern) and the canonized beatsheets of the Hero’s Journey.

I can’t speak specifically to every writer’s relationship to the Hero’s Journey, but I can speak to mine—which I daresay may indeed be similar to many people’s. Basically, I grew up engulfed in the Hero’s Journey, and I loved it. I resonated with it, played it out in the backyard with great gusto, and recreated it in my own stories.

But then I started reading about it in writing tomes…. and somehow didn’t quite resonate with it. Even though its beats clearly lined up with classic structure, I couldn’t help but feel a little claustrophobic about the whole thing. Although many of the terms I now use in teaching story structure have been borrowed from the classic Hero’s Journey, I have never specifically taught the Hero’s Journey or even consciously tried to apply it to my own stories.

The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson (affiliate link)

I always felt like something was missing. And then a few years ago, at the suggestion of a Wordplayer, I read Kim Hudson’s The Virgin’s Promise, which posits a feminine partner arc to the Hero’s Journey. In the book, she also reaffirmed Clarissa Pinkola Estés’s point, above, about the Maiden and the Hero being the youthful journeys, which should, in a mature life, be followed by the journeys of adulthood and elderhood.

In short, the Hero’s Journey is anything but all-encompassing. It may be universal in the sense that it represents an archetypal pattern that shows up in all our lives. But it is literally only one of multiple important life arcs.

Ka-pow. Mind blown. As depth psychologist Jean Shinoda Bolen puts it:

I had a sense of experiencing something beyond ordinary reality, something numinous—which is a characteristic of an archetypal experience.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

Not long after, as I began researching this series, I read The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell’s famed master text for the Hero’s Journey, and I was delighted to realize that what he describes as the Hero’s Journey is in fact a microcosm of all six life arcs. He talks about the stages of the Journey like this, and you can see how they align with the six life arcs (as well as two bookending archetypes).

Transformations of the Hero:

1. The Primordial Hero and the Human [Child]

2. Childhood of the Human Hero [Maiden]

3. The Hero as Warrior [Hero]

4. The Hero as Lover [Queen]

5. The Hero as Emperor and as Tyrant [King]

6. The Hero as World Redeemer [Crone]

7. The Hero as Saint [Mage]

8. Departure of the Hero [Saint]

Awakening the Heroes Within by Carol S. Pearson (affiliate link)

Indeed, Carol S. Pearson notes in Awakening the Heroes Within that:

The three stages of the hero’s journey—preparation, journey, return—parallel exactly the stages of human psychological development….

Not only did these authors’ exemplary work completely change how I view and plot my own stories, it also changed the way I view my life. Recognizing and studying all of these archetypes (and identifying which journey I am personally working on in my own life) has proven to be a profound initiatory experience.

And, truly, that is the point of any good archetypal character arc.

What Is an Archetypal Character Arc?Archetype changes us; if there is no change, there has been no real contact with the archetype.–Clarissa Pinkola Estés

If you have studied character arcs with me before, then you already know the essence of any character arc is change. Archetype, as noted in the quote above, adds the element of changing the reader—or at least, by its very nature, offering the opportunity to do so.

This is because all six of the archetypal arcs we will be discussing here are initiatory arcs. By that, I specifically mean they concern themselves on both a personal and a symbolic scale with Life, Death, and Resurrection.

Walking on Water by Madeleine L’Engle (affiliate link)

In short, archetypal arcs are not just about change. They are about change taken to its ultimate endpoint: what was can no longer be. Although your story may or may not feature literal death, what is really meant here is that the arc of one archetype is fundamentally about its own death—and subsequent rebirth into the archetype that follows. In Walking on Water, Madeleine L’Engle puts it:

To be alive is to be vulnerable. To be born is to start the journey towards death…. We move—are moved—into death in order to be discovered…. But without this death, nothing is born. And if we die willingly, no matter how frightened we may be, we will be found and born anew into life, and life more abundant.

For instance, the Maiden Arc is about the death of the Maiden archetype within the protagonist—and her rebirth into the Hero. The arcs are not about becoming the central archetypes (i.e., the Hero Arc is not about becoming a Hero), but rather about reaching the apotheosis of that archetype and then transitioning out of the height of that power into Death/Rebirth (i.e., the Hero surrenders his heroism and is reborn into the Queen archetype).

The foundational reason why these six arcs are so crucially central to the human experience is because they are all initiatory arcs. Particularly in our modern era when so many initiatory experiences (for the young, much less the adult and even less the elder) have been culturally lost or abandoned, these archetypal stories offer a deep resonant truth, and even subconscious guidance, that people crave.

Joseph Campbell:

5 Things to Know About Archetypal Character ArcsThe passage of the mythological hero may be overground, incidentally; fundamentally it is inward—into the depths where obscure resistances are overcome, and long lost, forgotten powers are revivified, to be made available for the transfiguration of the world. This deed accomplished, life no longer suffers hopelessly under the terrible mutilations of ubiquitous disaster, battered by time, hideous throughout space; but with its horror visible still, its cries of anguish still tumultuous, it becomes penetrated by an all-suffusing, all-sustaining love, and a knowledge of its own unconquered power. Something of the light that blazes invisible within the abysses of its normally opaque materiality breaks forth, with an increasing uproar.

Next week, we will begin studying the structural beats and thematic significance of each of the arcs—starting with my take on the Maiden Arc. Before we dive into the specifics of each individual arc, I want to take a brief moment to discuss a few basic principles that will apply to all the arcs.

1. Not All Stories Will Feature “Life Arc” ArchetypesJust as not every story features the Hero’s Journey, not every story will necessarily feature one of these specific archetypal arcs. In my experience and study so far, most stories do in fact fit into one of these categories. But just as these arcs are specific variations on the more general premise of the Positive Change Arc (and, later, the Negative Change and Flat Arcs), there may also be many variations on these archetypes. This is especially true for the beats and structures I will be presenting for each Positive-Change archetype.

2. These Archetypal Character Arcs Are Not the Only Archetypal ArcsArchetypes are legion. Many systems exist for categorizing and naming character archetypes—everything from Jungian archetypes to the Enneagram. Almost all of them offer something of validity and are worth studying and implementing in their own right. What I am exploring via these six Positive-Change Arcs (and their related Negative and Flat archetypes) is simply one possible approach to character archetypes within your stories.

3. A Single Archetypal Character Arc Can Be Told Over the Course of Multiple Stories in a Series

The Art of Fiction by John Gardner (affiliate link)

Each of these character archetypes lends itself to a distinct and complete story structure, which can be used to plot a single book—and that is how we will be discussing them. But as all writers know, in agreement with what writing professor John Gardner says in his book The Art of Fiction

Somehow the fictional dream persuades us that it’s a clear, sharp, edited version of the dream all around us.

In reality, fiction itself isn’t always so clear and cooperative. This means none of these archetypes must be confined to a single book. A character’s journey through a single archetypal arc may, in fact, require multiple books or even an entire series to accomplish.

4. Multiple Archetypal Character Arcs Can Be Told in a Single StoryBy the same token, it’s possible (although much trickier) to combine multiple archetypes into a single larger character arc for a single character within a single book.

Campbell himself speaks to this:

5. The Arcs Can Be Undertaken by Any Person of Any AgeThe changes run on the simple scale of the monomyth defy description. Many tales isolate and greatly enlarge upon one or two of the typical elements of the full cycle (test motif, flight motif, abduction of the bride), others string a number of independent cycles into a single series (as in the Odyssey). Differing characters or episodes can become fused, or a single element can reduplicate itself and reappear under many changes.

And finally, as I mentioned earlier, these arcs can be undertaken by any person of any gender or age. Eudora Welty observed:

The events in our lives happen in a sequence in time, but in their significance to ourselves, they find their own order … the continuous thread of revelation.

For example, it is possible to see older characters undergoing a Hero’s Journey. It is even possible to see how these experiences can be repeated within a smaller spiral of experience in every chapter of a human life. Indeed, the entire span of the arcs (from Maiden through Mage) can be seen mirrored within the individual structure of any one story—something we’ll talk more about as we go.

Most importantly, don’t get hung up on the gendered titles of these arcs. I have retained these titles (Hero, Queen, etc.) precisely because they reflect the masculine and feminine aspects of the journey. But these titles do not indicate that the protagonist must correspondingly be male or female.

The Hero Within by Carol S. Pearson (affiliate link)

For example, as is often discussed these days, characters taking a Hero’s Journey need not be male. Carol Pearson notes in the preface to her book The Hero Within:

Women’s journeys often differ in style and sometimes in sequence from those of men, but the hero’s journey is essentially the same for both sexes.

More than that, every single one of these arcs is important, in its proper order, for every person, regardless of gender. Generally speaking, the feminine arcs begin in integration and move to individuation, while the masculine arcs begin in individuation and move back to integration. Both are necessary for wholeness and growth, each leading into the next.

***

I will have more overview notes to offer at the end of the series, once we’ve explored all the archetypes. For now, I hope you’re as pumped as I am to dive into this juicy subject.

Stay Tuned: Next week, we will begin our journey with the Maiden Arc.

Related Posts:

Story Theory and the Quest for MeaningAn Introduction to Archetypal StoriesWordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever studied archetypal character arcs before? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Archetypal Character Arcs, Pt. 1: A New Series appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

February 1, 2021

An Introduction to Archetypal Stories

All art is necessarily both reflective and generative of the human experience. And in that way, all art both reflects and generates archetype. Some stories do this more simply and obviously than others. Those stories that we recognize as myth or fable are most blatantly archetypal. But even hyper-realistic stories—when they are well done—offer up to us the archetypal truths of humanity. Or as chef Mario Batali says:

All art is necessarily both reflective and generative of the human experience. And in that way, all art both reflects and generates archetype. Some stories do this more simply and obviously than others. Those stories that we recognize as myth or fable are most blatantly archetypal. But even hyper-realistic stories—when they are well done—offer up to us the archetypal truths of humanity. Or as chef Mario Batali says:

If it works, it is true.

Walking on Water by Madeleine L’Engle (affiliate link)

Madeleine L’Engle in Walking on Water comments that:

…all true art has an iconic quality…. All artists reflect the time in which they live, but whether or not their work also has that universality which lives in any generation or culture is nothing we will know for many years…. If the artist reflects only his own culture, then his works will die with that culture. But if his works reflect the eternal and universal, they will revive.

What is an archetype? My dictionary offers three definitions:

1. A typical specimen.

2. An original model.

3. A universal or recurring symbol.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

As we discussed last week, the very shape of story itself is archetypal. Its structure, by whatever system you prefer to codify it, is a blueprint for life itself, both as a whole and in its many smaller integers. In future weeks, we’re going to be talking about some specific archetypal models (of which there are many) that you can use to discover, guide, and amplify the archetypes within your own stories. But today, let’s examine the intermediary ground—why it should be that story and archetype are so intertwined and what this means for you as a writer attempting to channel these deep patterns of human existence.

Story as RevelationMany writers can speak to the experience of “receiving” a story. Much as Stephen King has famously described his own process, we don’t so much create our stories as we discover them. It is as if the bones, at least, are always there, and all we have to do is figure out how to dig them up. When the creation process is at its most powerful, we are “in the zone,” writing madly away, just hoping our fingers can move fast enough to get it all down before the inspiration fades.

Dr. Friedrich Dessauer, an atomic physicist at the turn of the 20th Century, mused that:

Man is a creature who depends entirely on revelation. In all his intellectual endeavor, he should always listen, always be intent to hear and see. He should not strive to superimpose the structure of his own mind, his systems of thought upon reality.

Proust Was a Neuroscientist by Jonah Lehrer (affiliate link)

I think Dessauer would agree with Jonathan Lehrer in Proust Was a Neuroscientist when Lehrer says:

Physics is useful for describing quarks and galaxies, neuroscience is useful for describing the brain, and art is useful for describing our actual experience.

Writers can easily attest to the delicate balance of uncovering life’s patterns as recorded in our collective story theories so that we may better tap into them, but not so that we may superimpose them where our deeper wisdom and creativity knows they do not belong.

Women Who Run With the Wolves by Clarissa Pinkola Estés (affiliate link)

In her book Women Who Run With the Wolves, a poetic exploration of the feminine journey via archetypal stories, psychologist and oral storyteller Clarissa Pinkola Estés speaks passionately to the storyteller’s (and indeed the human’s) responsibility to channel this archetypal inspiration:

Our work is to interpret this Life/Death/Life cycle, to live it as gracefully as we know how, to howl like a mad dog when we cannot—and to go on…. Although some use stories as entertainment alone, tales are, in their oldest sense, a healing art. Some are called to this healing art, and the best, to my lights, are those who have lain with the story and found all its matching parts inside themselves and at depth.

When writers first begin learning about archetypal story structure, they are often astonished (as I was) to examine their own stories and discover that these archetypes they’ve heard of before are there already within their best stories—or waiting to be uncovered to help those stories find a truer voice.

How is it that even the most uneducated writers seem to have at least a glimmer of an understanding for these archetypes? Perhaps it is because these patterns are everywhere, and we necessarily absorb them by osmosis. Perhaps, as the depth psychologists would have it, it is because these archetypes reside in a collective unconscious. Or perhaps it is simply because as humans we resonate with the patterns of our existence and instinctively understand how to recreate them in our art.

Whatever the case, archetypal stories and characters have populated the greater archetypal mythologies of the human experience for as long as we can remember. As Willa Cather says in one of my favorite quotes ever:

Mythological Character ArchetypesThere are only two or three human stories, and they go on repeating themselves as fiercely as if they never happened.

Most of what we specifically think of as character archetypes are found in the stories that have been mythologized, whether from history, religion, or folk and fairy tales. What we recognize as the origins for these stories and their characters are often simplistic, fantastical, and moralistic. They often repeat over and over again throughout the millennia, varied but always foundationally similar from culture to culture and era to era. Or as Estés put it:

That is the nature of archetypes… they leave an evidence, they wend their way into the stories, dreams, and ideas of mortals. There they become a universal theme, a set of instructions, dwelling who knows where, but crossing time and space to enwisen each new generation. There is a saying that stories have wings. They can fly over the Carpathian Mountains and lodge in the Urals. They then vault over to the Sierras and follow its spine over and hop to the Rockies, and so on.

The Art of Fiction by John Gardner (affiliate link)

In The Art of Fiction, writing instructor John Gardner distinguished “fables,” “yarns,” and “tales” as layers of story that move increasingly away from non-reality (i.e., fantasy) into the more nuanced and specific realms of realism. But even the hyper-realistic fiction of post-modernism rests upon the foundations of myth and its metaphors.

Psychologist James Hillman notes:

Mythology is a psychology of antiquity, psychology is a mythology of modernity.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell

When modern writers think about archetype, we are most likely to think of the now ubiquitous Hero’s Journey, made famous by Joseph Campbell’s mythological research in The Hero With a Thousand Faces and since codified by many writers (most notably Christopher Vogler in The Writer’s Journey) as a profoundly powerful archetypal character arc. The Hero’s Journey is a deeply metaphoric structure that finds its most literal representation in fantasy—with its often black-and-white representations of good and evil, complete with dragons, resurrections, kingdoms, and wizards. But it is found over and over again in story after story, whether fantastical or realistic, proving its versatility. (However, it is not the only archetypal character arc, and not even the most important one—which is what we will be discussing in the upcoming series, featuring six primary and serial arcs, of which the Hero’s Journey is the second.)

Archetype as the Path to Powerful StoriesSo why do archetypes matter? To a writer, they matter for the most obvious reason that they are stories. But more than that, they are stories that work. The very fact that these patterns have not only stuck around over the years, but in fact have proven themselves to still be meaningful should be enough to perk up the ears of any writer. After all, that’s what we’re all hoping for in our own stories, isn’t it?

Like the structure of plot and character itself, archetypes offer writers insights into modalities of deeper and more resonant fiction. The mere pattern of an archetype is not resonance in itself (as the many cookie-cutter productions of the Hero’s Journey, ad nauseum, have proved). But the archetypes offer the storyteller a glimpse into some of the deeper insights and truths of humanity.

Gardner points out:

Fiction seeks out truth. Granted, it seeks a poetic kind of truth, universals not easily translatable into moral codes. But part of our interest as we read is in learning how the world works; how the conflicts we share with the writer and all other human beings can be resolved, if at all; what values we can affirm and, in general, what the moral risks are. The writer who can’t distinguish truth from a peanut-butter sandwich can never write good fiction. What he affirms we deny, throwing away his book in indignation; or if he affirms nothing, not even our oneness in sad or comic helplessness, and insists that he’s perfectly right to do so, we confute him by closing his book.

More than that, archetypes—particularly the specific archetypal character arcs that represent the human life—have the potential to offer writers and readers alike a subconscious road map to our own initiatory journeys through life.

That has been my own experience with these archetypal character arcs. Merely in coming to a recognition of them (and particularly that the Hero’s Journey is one of many and where it fits within the pattern—and therefore within my own life as well as my characters’), I have personally found just as many gifts as a person as I have as a writer.

Campbell says it as well as anyone:

The tribal ceremonies of birth, initiation, marriage, burial, installation, and so forth, serve to translate the individuals’ life-crises and life-deeds into classic, impersonal forms. They disclose him to himself, not as this personality or that, but as the warrior, the bride, the widow, the priest, the chieftain; at the same time rehearsing for the rest of the community the old lesson of the archetypal stages. All participate in the ceremonial according to rank and function. The whole society becomes visible to itself as an imperishable living unit. Generations of individuals pass, like anonymous cells from a living body; but the sustaining, timeless form remains. By an enlargement of vision to embrace this super-individual, each discovers himself enhanced, enriched, supported, and magnified. His role, however unimpressive, is seen to be intrinsic to the beautiful festival-image of man—the image, potential yet necessarily inhibited within himself.

Whether we are writing about falling in love in a YA novel, fighting dragons in a fantasy, making peace with adult children in contemporary fiction, ruling a corrupt dynasty in a historical novel, or conversing with the moon in magical realism—we are all writing about our own experiences of the world and, by extension if we write well and truly enough, everyone else’s experiences as well.

The Emotional Craft of Fiction by Donald Maass

In closing, here is one last quote, this one from Donald Maass’s wonderful Emotional Craft of Fiction:

You may think you are telling your characters’ stories, but actually you are telling us ours.

Stay tuned: Next week, we will officially kick off the series on archetypal character arcs with an introduction to the six primary Positive Change Arc character archetypes we will be studying.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What has been your experience reading, viewing, or writing archetypal stories? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post An Introduction to Archetypal Stories appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 25, 2021

Story Theory and the Quest for Meaning

Story has been our constant companion throughout the journey of human existence. Why is that?

Story has been our constant companion throughout the journey of human existence. Why is that?

Modern audiences are inundated and entranced by advanced storytelling. But stories have been with us from as far back as we can remember. Is it because they entertain us? Is it because they inform us? Because they distract us? Yes, of course. But the very universality of, not just story itself, but our passionate connection to story would seem to indicate the human experience finds great resonance in the act of storytelling.

I do not think it too simplistic or idealistic a statement to say that storytelling is a quest for meaning. As creators and consumers of story (and, indeed, art as a whole), we all have personal connections to this. We often interact with stories, whether intellectually or emotionally, as a search for understanding. We turn to stories for catharsis, comfort, and catalytic challenge.

Walking on Water by Madeleine L’Engle (affiliate link)

As Margaret L’Engle put it in her Walking on Water (which is really a treatise on the whole concept of story as a quest for meaning):

This questioning of the meaning of being, and dying and being, is behind the telling of stories around tribal fires at night; behind the drawing of animals on the walls of caves; the singing of melodies of love in spring, and of the death of green in autumn.

As writers, we gradually become more cognizant of this than even the average viewer or reader. As we study the craft and technique of writing, we eventually encounter humanity’s collective ideas of story theory. These theories posit that there are certain patterns—which we generally identify by such terms as story structure and character arc—that repeat themselves over and over again to create the very definition (however loose) of what we consider a story at all.

When writers begin learning story-theory principles, we often tend to identify them merely as “rules for success.” But in recognizing that story itself is archetypal, these tools and techniques of the craft emerge as a fascinating meta commentary on the deeper questions of life itself.

Chaos vs. CosmosThis post is an introduction to the introduction to the introduction (!) of a new craft series I will be sharing this year about foundational archetypal characters and character arcs (including but going far beyond the prevalent Hero’s Journey). Before diving into the nitty-gritty of this one specific set of archetypes and how you can use them to powerfully undergird the character arcs in your stories, I wanted to step back to the broader context. Next week, we’ll be talking more specifically about actual archetypes in fiction. But today, I wanted to talk about story itself as archetype.

Several years ago at a time when I was particularly needing, searching for, and redefining meaning in my own life, I read Madeleine L’Engle’s wonderful ode to the synthesis of art and spirit, Walking on Water. I resonated deeply with her notion of why it is that humans are driven to create and to tell stories. She said:

…the artist is someone who is full of questions, who cries them out in great angst, who discovers rainbow answers in the darkness and then rushes to canvas or paper. An artist is someone who cannot rest, who can never rest as long as there is one suffering creature in this world. Along with Plato’s divine madness there is also divine discontent, a longing to the find the melody in the discords of chaos, the rhyme in the cacophony, the surprised smile in the time of stress or strain.

It is not that what is is not enough, for it is; it is that what is has been disarranged and is crying out to be put in place.

She recognized art as an ordering principle by which humankind strives to understand its own existence:

The Cosmology of Story Theory[Composer] Leonard Bernstein tells me more than the dictionary when he says that for him music is cosmos in chaos…. all art is cosmos, cosmos found within chaos…. There’s some modern art, in all disciplines, which is not; some artists look at the world around them and see chaos, and instead of discovering cosmos, they reproduce chaos, on canvas, in music, in words.

The more I study story theory, the more I have come to recognize it as something of a cosmology all its own—a microcosmic commentary on existence. In short: an archetype.

As such, what we write (sometimes consciously, usually very unconsciously) is often surprisingly explicit in its ability to offer us answers and meaning in our questions about life.

For example, modern writers often tend to think of story structure as a format we apply to our stories. But, in fact, story structure is an emergent. It exists and it works—and we recognize it as such and try to apply it to our own stories—because it reflects truthful patterns about life itself.

The same is true—perhaps even more poignantly—for character arcs. For me, researching and writing my book Creating Character Arcs was a personally life-changing experience that provided insights far beyond writing. The character arcs we recognize as archetypal resonant with us as readers and viewers for the simple reason that they are patterns within our own lives.

And so it goes for even more “mythic” archetypal journeys, such as the Hero’s Journey made so famous and ubiquitous by Joseph Campbell and George Lucas. These mythic story structures are endlessly repeatable because they do endlessly repeat in every single one of our lives. (Don’t particularly identify as a Hero? Doesn’t mean you haven’t, or won’t, take the Hero’s Journey in your life, among many others.)

This is why L’Engle can say, about writing and reading, that:

Story was in no way an evasion of life, but a way of living life creatively instead of fearfully. The discipline of creation, be it to paint, compose, write, is an effort toward wholeness.

She quotes her professor Dr. Caroline Gordon as saying:

Meanings, Patterns, Symbols, and ArchetypesWe do not judge great art. It judges us.

Story theory is eminently practicable in supplying writers with techniques they can apply to improve the resonant power, and therefore success, of their stories. But this is really just a byproduct of the theory itself, which focuses on recognizing emergent patterns within our ever-growing body of stories. These patterns then contribute to our ability to recognize those particular symbols and archetypes that appear over and over again, almost universally, rising far above time, place, genre, or even thematic intention.

Laurens Va Der Post pointed out:

…without a story you have not got a nation, or a culture, or a civilization. Without a story of your own to live you haven’t got a life of your own.

At their loftiest level, the emergent patterns of human stories tell us something about all of existence. But for most of us, these patterns are most poignant when they help us tell our own stories—not just those we put on paper, but those we are living every moment of every day.

We may think of stories as something separate and apart from life itself—particularly in this day and age when stories are more accessible and abundant than ever and we most commonly interact with them with the intention of entertainment or distraction. But inevitably story is not separate. Indeed, perhaps the modern era has seen the line between story and reality grow more blurred and meta than ever.

Regardless, when we understand the symbiosis of art and life, we are able to simultaneously bring the patterns of life to the page and the patterns of the page to our lives.

L’Engle one more time:

…when the words mean even more than the writer knew they meant, then the writer has been listening. And sometimes when we listen, we are led into places we do not expect, into adventures we do not always understand…. one does not have to understand to be obedient. Instead of understanding—that intellectual understanding which we are so fond of—there is a feeling of rightness, of knowing, knowing things which we are not yet able to understand.

Humans interact with stories for many reasons, all of them valid. But deeper than the entertainment, the distraction, or the titillation—deeper than the characters, the character arcs, and the plot structure—deeper even than the themes of Willa Cather’s “two or three human stories”—there is the resonance of story itself as a foundational archetypal reflection.

I don’t know about you, but that’s a plenty good enough reason for me to make story a constant companion for the rest of my life.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Why do you think you were first drawn to stories? Has that changed over the years? Tell me in the comments!The post Story Theory and the Quest for Meaning appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 18, 2021

3 Character Arcs in the Karpman Drama Triangle

Drama presents something of an interesting conundrum. On the one hand, drama is the essence of story. Without it and its inherent dissonance, conflict, and stakes, there really isn’t much to a story. As writers and readers, we love drama.

Drama presents something of an interesting conundrum. On the one hand, drama is the essence of story. Without it and its inherent dissonance, conflict, and stakes, there really isn’t much to a story. As writers and readers, we love drama.

The irony is that, in real life, we recognize drama is often inherently destructive. “Drama queen,” “spare me the drama,” “addicted to drama”—these are all decidedly derogatory references.

Indeed, part of the reason we love drama in fiction is because of its catharsis. Clearing drama in real life is an often herculean task, so it’s a relief to watch characters tackle much bigger problems than ours and work through them (often in ways we would never dare attempt ourselves). Plus, sometimes we just love to watch a train wreck.

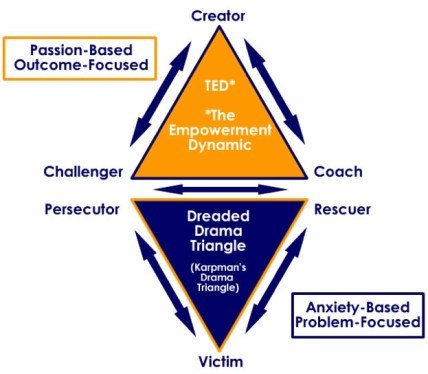

The Karpman Drama Triangle is a social model (created by Dr. Stephen Karpman, who not so coincidentally happened to be a member of the Screen Actors Guild) that shows the destructive cycle in which people unconsciously cast themselves as one of three players—Victim, Rescuer, or Persecutor. (Note: Karpman specifically distinguished the reference to the Victim as applying to someone who is “playing” the Victim, not someone who has literally been wounded by another.) Decades later, leadership coach David Emerald proposed The Empowerment Triangle as a “positive alternative to the Drama Triangle,” in which he offered the more proactive roles of Creator, Coach, and Challenger.

(From Wikimedia Commons.)

For a while now, I have been pondering the Drama Triangle and its inherent link to fiction. In real life, Drama-Triangle dynamics lend themselves to destructive cycles of disempowered passive-aggression. When we consciously or unconsciously identify with any of the three players—Victim, Rescuer, or Persecutor—we often adopt patterns of behavior that allow us to ultimately fob off responsibility for our own motives and actions.

Those who identify (or allow themselves to be identified as) Persecutors or Villains are often consumed and controlled by ineffective and crippling guilt. Those who identify as Victims wait around to be rescued from their own lives and/or try to control others with guilt. Those who identify as the Rescuer or Hero (which most of us prefer to) feel obligated and/or gain self-esteem in codependent ways by rescuing others from their own mistakes and responsibilities.

So much of fiction features this dynamic literally—with a Hero saving a Victim (even if it is just society at large) from a big bad Villain. This gives me pause. We all love a good adventure story in which the Hero swoops in to do good and save the day and destroy the icky Villain. But in repeating this archetypal story over and over, are we perhaps subconsciously perpetuating a destructive and immature cycle?

Does Fiction Perpetuate the Drama Triangle?At first glance, the answer certainly seems to be “yes.” And I think there are stories in which this is true, if only because some authors (who are themselves perhaps unconsciously enacting the Drama Triangle—as we almost all do at least from time to time) are writing stories with on-the-nose themes that specifically evoke ideas of codependency.

However, I think there is more at play here than meets the eye. It is no coincidence that the three actors in Karpman’s triangle are in fact the only three character types necessary to a working storyform. The Hero is obviously the protagonist or primary actor within the plot. The Villain is obviously the antagonist or primary opposition to the protagonist—and thus the source of conflict. And it’s not too much of a stretch to see the Victim represented in the Relationship Character (often a Love Interest) who creates the catalyst for both action and change in the protagonist.

Millennia of story theory has shown us this is simply how story works. We need these three guys if we’re to keep telling interesting, meaningful, dramatic stories.

More than that, although story is undeniably both a commentary upon and a model for social behavior, it is first and more deeply a representation of a single psyche. Like a dream, a story is the projection of the author’s mind. Every character within it is the author. And insofar as the reader relates to the story, every character becomes a recipient for the reader’s own projections.

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell& (affiliate link)

This means that on an archetypal level a story in which a Hero saves a Victim from a Villain is most primally a representation of a single person’s psychological adventures. As such it becomes less a model for our relationships with others in the world and more a map to our own inner growth. We often forget that Joseph Campbell’s revolutionary presentation of the Hero’s Journey in The Hero With a Thousand Faces was not created as a guide for writing stories, but rather as a key for using story to interpret life.

Consciously Using the Drama (and Empowerment) Triangle to Create Powerful Character ArcsAuthors cannot avoid or dismiss the Drama Triangle. In fact, it is a deeply important and archetypal presentation of the human experience. However, this is not to say it may not still be used for ill in perpetuating damaging and disempowering dynamics if the author is unconsciously presenting the triangle in a too-literal way.

David Emerald created his Empowerment Triangle as a way for people to step beyond the passive Drama-Triangle roles projected onto them and which they in turn project onto others. His Creator, Coach, Challenger model offers a perspective in which each person is invited to:

Change “Victimhood” from a passive state of helplessly receiving whatever someone else decides to give you into a proactive state of “Creating” your own perspectives and choices.Stop acting “Heroically” by taking responsibility for someone else’s life and instead acting as a self-contained but positive Coach who helps but does not solve others’ problems.See potential “Villains” as “Challengers” who may in fact be incidentally providing opportunities for growth.In examining the upshift from the Drama characters to the Empowerment characters, what I find most interesting is that the Hero essentially becomes the Mentor. This is a shift we recognize within classic stories as the one a successful Hero will inevitably take. As he grows older and becomes the gray-bearded old wizard, he evolves into a Coach for the up and coming young would-be Heroes. And so the cycle repeats.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

This makes the pairing of these two triangles a fantastic tool for creating archetypally solid character arcs of growth (or if you decide to move from Empowerment Triangle backwards to Drama Triangle—arcs of destruction). Consciously embracing these particular characters can not only give you a map to solid and resonant stories, it can also create positive psychological models—not unlike the Hero’s Journey—which can subconsciously combat the Drama Triangle’s effects in our real world.

Let’s take a quick look as the three positive arcs available through these models.

Character Arc #1: Hero to CoachA young upstart Hero often starts with what she believes are good intentions. She’s out to save the world (or whomever). She may be determined to save them whether they want to be saved or not. Or she may reluctantly agree to help and then internalize too great a sense of responsibility in which she feels that no one else will be responsible if she fails, just her.

While this belief may be true within the model of story-as-psychological-map, it is patently not true in real life. This is the lesson the Hero must learn if she is to arc into the Coach. She cannot take the burden of the world onto her shoulders. She is not God. She is one human within a vast system of humans. She is responsible for her mistakes, her knowledge. Others are responsible for the same. She must overcome her ego’s need to be heroic for the sake of heroism and be willing, as her wisdom grows, to step back and allow everyone else an equal right to their own journeys and their own personal responsibilities.

Character Arc #2: Victim to CreatorThis is perhaps the most dramatic and arguably the most powerful of the three arcs since it demands such a profound transformation. Karpman conceived of the Victim as someone with a codependent or immature mentality that enabled him to “play” the Victim, via an expectation that others are obligated to save him. However, within the symbolic form of story, the Victim often will be a true Victim in some way—someone physically trapped, wounded, or endangered. In these stories, it can still be satisfying for the Victim to actually be rescued by a Hero, since this represents a deeper psychological play. However, there is also the inherent opportunity to allow the Victim to arc out of weakness and dependence into strength and responsibility.

This arc isn’t necessarily indicating that the Victim will arc into the Hero. After all in this context the Hero is an equally problematic characterization and not necessarily a step up. (Indeed, few of us in real life identify solely with just one of the Drama Triangle characters—we cycle through all of them, sometimes within the span of minutes!) Rather, the Victim’s arc will lead him to become a powerful Creator of his own reality and destiny. Rather than allowing himself to be defined by his own weakness or the weakness of others, he rises into personal sovereignty, shaking off codependent habits and stepping into the full and awesome burden of total personal responsibility.

Character Arc #3: Villain to ChallengerComprehending the essence of this arc starts with understanding that someone who personally identifies as a Villain is not necessarily someone who is currently perpetuating wicked deeds. Those who persist in harming others rarely see themselves as Villains but instead see themselves, notoriously, as “the heroes of their own stories.” This means that in order to create a Positive-Change Arc in which a character moves from identifying as the Villain to identifying as a Challenger, this character will start out controlled by her guilt.

In real life when we see ourselves as Villains it is usually because either we’ve done something we ourselves view as unforgivable or someone else is using our guilt to manipulate us. The arc here is one of shaking off false responsibilities to others while fully claiming our own. Like the previous two arcs, the essence of this one is also about personal responsibility. The character must learn to discern rightly what amends are really hers to make, to make them, and then to refuse to be controlled by any continuing codependence from the would-be Victims or Heroes in her life. In this way, she rises to become a Challenger to these other characters, daring them to likewise rise into their own empowerment.

***

Like so many social models and personal-development tools, the Drama Triangle and the Empowerment Triangle can be mined in ways that are meaningful in both your own life and in your stories. Consciously using them to understand the true dynamics between your characters can help you master tricky stories.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you see any of the character arcs in your story represented in either the Drama Triangle or the Empowerment Triangle? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post 3 Character Arcs in the Karpman Drama Triangle appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 11, 2021

How to Start, Build, and Grow Your Email List

One of the most essential steps you’ll ever take when preparing for your book launch and starting your career as a serious author is your email subscription list. Having a good, strong, dependable email list of actively engaged subscribers is crucial to your success as a writer and your book’s success. And as daunting as it sounds, it’s really not that difficult to get one started! But before we dive into the how-to of list-building, let’s first lay the foundation on the why.

One of the most essential steps you’ll ever take when preparing for your book launch and starting your career as a serious author is your email subscription list. Having a good, strong, dependable email list of actively engaged subscribers is crucial to your success as a writer and your book’s success. And as daunting as it sounds, it’s really not that difficult to get one started! But before we dive into the how-to of list-building, let’s first lay the foundation on the why.

Yes. More so than ever. And here’s why…

Think of it in terms of where you live. Having a dependable list of subscribers is like owning your home, while relying on your social media accounts to reach readers is like renting.

Your profile and your feed on all social-media platforms are nothing more than rented space! Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, heck, each and every one of the social media platforms is owned by some huge corporate conglomerate. They only allow you to rent space on their platform. Each and every contact you’ve developed on each platform, you have borrowed from those site owners. So, if they decided tomorrow they are rich enough and don’t want to fool with social media anymore, and they decide to shut them down… guess what happens to all your content and all your contacts? That’s right… they’re gone!

However, the space you’ve created on your website and/or email account is technically your space. Once your subscribers give their permission for you to contact them, you own the right to contact them, and you own all the content you send to them every time you email them. You can say what you want and do what you want without fear of being locked in “Facebook Jail.” That alone should be reason enough for you to have your own email list.

Am I saying to get rid of social media? Absolutely not! In fact, ride that wagon until the wheels fall off! But instead of depending on social media to grow and reach your reader list, start thinking of it more as a support system rather than your go-to way of communicating.

Okay, so where do I begin?

Easy-peasy. First thing’s first, make sure you have created an author-ish email account! And by author-ish email account, I mean, not the one you created in middle school (I’m talking to you unicornsparkles@gmail!) It needs to be clear this is your professional author email account. Pick an email prefix that is clearly related to you as a writer, such as authorchristinakaye@email. Got it?

Pro Tip: If you are fine with having an extension that says “@gmail.com or @outlook.com” you can leave it at that. However, if you have or want to have your own domain extension for your website and email (i.e., mine is info@christinakayebooks.com because my Google domain for my website is christinakayebooks.com), you must first buy your domain on Google Domains, GoDaddy, etc., and set that up. All domain sellers also offer you at least one email box for free or around $5/month.

Pick Your Email Hosting ServiceThe very next step is to pick your email hosting service. Here are some of the most common email hosting services out there:

MailerLiteConstantContactConvertKitAWeberMailChimp

Pro Tip: I highly recommend MailerLite. They are more affordable, user-friendly, and they even have newsletter templates specifically for authors!

Create Your Lead MagnetNext, you’ll need to create your freebie aka Lead Magnet! This is crucial to building your subscriber list, and it’s pivotal in any author’s marketing campaign. A Lead Magnet is a downloadable resource (usually a pdf) you offer to readers for free in exchange for signing up for your email.

Some common Lead Magnets authors use are as follows:

First 1-2 chapters of your upcoming releaseFirst 1-2 chapters of a backlist bookFree entire copy of a backlist bookCharacter Interview with any of your lead charactersBehind the Scenes Sneak Peek into your upcoming releaseFor my current Author Lead Magnet, I am using the tried-and-true “first few chapters” download.

Whatever you choose to go with, simply create your lead magnet in Word (or Docs) and save it as a pdf. Quick and easy!

Pro Tip: You can also use Canva to create a beautiful and enticing Lead Magnet. Either way, make sure it’s not too long (no more than, say, 20 pages), visually pleasing (include images if you can), and relates to you, your books, and your brand.

Okay, I’ve Got My Lead Magnet, How Do I Send It to Readers?The key idea behind a lead magnet is that it’s so appealing (and free) that readers are willing to jump at the chance to give you their preciously guarded email address just so they can get their paws on what you’re offering. And here’s how that works.

Step 1: Create a Landing Page

Step 2: Attach Lead Magnet to Landing Page

Step 3: Send the Landing-Page Link to Everyone

I highly recommend you start by sending it to all your established friends and family, as they’re most likely the ones who will jump at the chance to support you! Then you can post on your social feeds. Without sounding too salesy, simply explain to folks that you’re starting your first newsletter and you’d love to give them something free in exchange for signing up.

Now, just sit back and watch your subscriber list grow daily! Your email hosting service will do all the behind-the-scenes work!

I Have 50 subscribers Already! Now What?

First off…congrats!

Once you’ve established fifty, thirty, or even just twenty subscribers, it’s time to start nourishing your growing email list. If you create a subscriber list but you never post anything fun, entertaining, or informative, you’ll quickly lose those few you’ve started with and you’ll not be able to grow your email list. Make sure you are providing regular updates to your subscriber list and make sure every broadcast is something they want to hear about.

I always recommend starting out with just once-a-month newsletters. This takes some of the pressure off authors who are just getting started and who are in the middle of all the other things required of them for a successful book launch. You can also release your newsletter every two weeks or once a week, depending on your preference and availability. Whatever frequency you choose, just be sure you are consistent and that you never leave your subscribers hanging.

Whichever email hosting service you go with, you can even schedule your newsletter drops in advance. Let’s say you wanted to send a new email out every two weeks. You can batch several of them (meaning, write them all ahead of time in one sitting), then upload the content and schedule them to go out on whatever date you want them to.

Once again, the key to growing and nurturing your subscriber list is consistency! Do not over-commit!

Pro Tip: I recommend picking a day out of each week to be your dedicated newsletter release date. For example, at Write Your Best Book, our newsletter typically goes out every Monday morning. So by Sunday night, our content is written, images pulled, and we upload it to our hosting service and schedule it for 9 AM the next day. Being consistent works miracles when it comes to engaging and nurturing your subscriber list!

I Think I Get It, But What on Earth Am I Supposed to Talk About Once a Month/Week?

Great question! I’m asked this frequently. Here are some easy to write but interesting ideas for your newsletter content:

Announce book salesAnnounce giveaways/contestsExcepts/bonus chaptersShare your writing processShare your writing milestonesShare curated content that fits your genreAnnounce book releasesAnnounce cover revealsTalk about “how I stay motivated”Share the story behind your current releasePro Tip: Be sure to brand your newsletter template and each newsletter you send out. By this, I mean, use the brand colors you have (hopefully) already chosen for your marketing campaign, and use only those colors and fonts in each newsletter.

***

Above all else, make sure your newsletter is full of you! Make sure your voice shines through. After all, you’re a writer, and your voice is what makes your work so unique. It’s why people want to hear from you in the first place. It shouldn’t take you more than thirty minutes each week to type up your content and schedule your newsletter.

For more advice, tips, and tricks on starting, growing, and nurturing your email list, or to ask me anything about writing, publishing, or selling your own books, feel free to email me at info@writeyourbestbook.com.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you started an email list? What was (or is) your biggest challenge in doing so? Tell me in the comments!The post How to Start, Build, and Grow Your Email List appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

January 4, 2021

7 Writing Lessons Learned in 2020

Happy New Year!

Happy New Year!

For me, the turning of the year is certainly a time of examining habits, renewing intentions, and creating plans. But more than setting goals for the coming year, I prefer to think about the lessons I have learned from the year that has passed.

In my experience, goals all but just happen when their required foundations are in place. When that foundation is lacking, then even a great amount of energy and application cannot achieve the desired result. And so when the New Year rolls around, I like to look back at the foundations that have been laid in the past twelve months. What has the year taught me? And how can I build on what I have been given?

This past year was a year like no other. This is clearly true on a global level, and I daresay it is true for each of us in small and subjective ways. Certainly, it has been true for me. Aside from all the big impacts to the world “out there,” my own year and particularly my year as a writer has also been a year like no other. Even in comparison to other recent years, it was a year that deeply challenged almost all the beliefs and identities I have carried around my writing.

It was not a year of deep productivity in an external sense. It was probably the year in which I wrote less fiction than I ever have since my pre-teen years. Largely due to this, it was an unsettling year for me as a writer. It has made me ask questions and face fears.

In many ways, for obvious reasons, it was one of the hardest years ever. But also in many ways, for me personally, I am surprised that it has given me some of the greatest gifts I have ever received. Most of the reason I can say that is directly related to the lessons this past year has taught me about myself as a person and as a writer.

Today, I would like to share seven of the writing lessons I feel I learned (or at least started learning) in 2020, in hopes that they will inspire, ground, and encourage you in contemplating your own foundation for moving forward into the wide new frontier of 2021.

7 Writing Lessons to Build On in the New Year

1. Don’t Be So Serious (Play More)

Don’t take life so serious…. It ain’t no how permanent.–Walt Kelly

When did writing become such super-serious business? I look back on general advice I internalized as a young writer starting out, and while I recognize that it helped me build a career, I also realize that such gems as the following also created a pretty grim outlook:

“Treat writing like a job.”

“If you don’t take your writing seriously, no one else will either.”

“If writing doesn’t pay, it’s not worth doing.”

“If you aren’t writing something readers will love, you’re not a real writer.”

I’m not saying there isn’t a measure of truth and value in those statements. But where’s the fun? Where’s the joy of creation for creation’s sake? After all, storytelling is an inherently childlike act. Entertainment is all about having fun.

Mostly, I recognize that this super-serious outlook has less to do with my writing and more to do with me as a grown-up human grappling with what admittedly seems a pretty serious world. In this year when I wrote almost no fiction, I have realized that if my writing doesn’t seem as much fun as it used to, it’s because the act of telling stories has grown separate from the simple joy of creation that prompted it when I was young.

The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron (affiliate link)

Building on the Lesson: And so I plan to play more in 2021. More “artist’s dates” with my inner child such as Julia Cameron suggests in The Artist’s Way. No more sitting at the desk and demanding I write something about which I have little enthusiasm. No more self-flagellation for not writing. Writing, as we all know deep down and as Jeff VanderMeer points out (in this wonderful article which one of you shared in the comments section of the post “What Is Dreamzoning? (7 Steps to Finding New Story Ideas)“) is far more about not writing that it is the actual writing.

2. Remember Why You’re Here (How It All Started)

That brings me back to the reason I started writing in the first place. What was yours? Do you remember?

I think I rather lost mine for a while, amidst all the very serious work of becoming a capital-letter Writer. But here’s my reason—here’s why I’m here, talking to you, writing this blog every week—here’s why I’ve spent the better part of my life typing away at the keyboard, why I’ve published five novels and why any of this matters to me at all.

I didn’t start out as a writer. I started out as a kid who loved to tell and play stories. At a certain point I decided I would write one down—because I loved it and its characters so much that I didn’t ever want to forget it. I started writing because of the way it made me feel—like there was a infinite world of possibilities out there.

In short, I don’t write because I’m a writer or even because I love writing (although I do). I write because I love my stories so much I want never to forget them.

Building on the Lesson: Maybe I will never find that same childlike passion again. Maybe adults must write for other reasons. But I don’t really believe that. At any rate, I’m committed to giving myself a chance to find that again—to find another story I love so much I must write it down if only so I will never forget it. In practicality, I think there are two steps to this.

One, I must learn to listen again. And two, I must be willing not to write, not to keep flogging the brain. I think that is perhaps the scariest thing of all. Indeed, even as I write this, there is a part of me that isn’t sure I can consciously commit to not at least trying to write for a while. But the very fact that it scares the spit out of me tells me it’s probably exactly the right step forward.

3. Find Your Inspiration (What Do You Want to Say?)

I’ve spent a lot of time in the dreamzone so far this winter, trying to see if there is a story ready to be written. What I’ve realized is that part of what I’m searching for is something new to say. I used to believe we each have one story to tell and we just go on telling it in different ways all our lives. I still think there’s truth to that, but I’m also coming to realize that perhaps I have finished telling the story I was given to tell in the First Act of my life. Now, as I enter the Second Act, I am too different a person. Much as I love the early stories, they are stories that belong to my younger self, not the Me that now is.

This is both frightening and exciting, since I don’t yet know what story I have to tell in this new chapter of my life. I know I have things to say. I can feel them all but bursting inside of me: I just don’t know what they are yet.

Building on the Lesson: This, too, goes back to listening. I often think of Jo March’s statement in the 1994 adaptation of Little Women:

I want to do something different. I don’t know what it is yet, but I’m on the watch for it.

I foretell that one of the greatest challenges of this coming year will be, for me, sitting still, keeping my mouth shut, listening, and waiting. What is it I want to say in a new story? I don’t know yet. But I have always believed that if you know the question, you know the answer. At least I have the question now.

4. Keep Perspective (Writing Was Always Hard)

Somewhere within the last few years, I got this unspoken, mostly subconscious idea that writing wasn’t supposed to be hard. Sure, it required discipline. But agony, doubt, wasted hours, writer’s block? Nah.

It just so happened 2020 was the year in which I decided to re-read all my old journals, starting from when was I was thirteen. It’s a chronicle of all my writing years. And mostly it’s a chronicle of how hard writing has always been. I started and failed on so many more stories than I remembered. I took looooong breaks in between finished novels because I had no idea what to write.

In short, none of this is new. It’s been a welcome, humbling, and slightly humorous return to perspective.

Building on the Lesson: One of the great values in writing a journal (or a blog) is that we can return to remember insights from our former selves which we may have lost track of. So this year I will continue journaling, and I will continue reading my old journals—as letters from my much wiser younger self to my sometimes short-sighted current self. :p

5. Nothing Is Ever Wasted (Unexpected Gifts)

Like so many of us in our fast-moving society, I have a tendency to judge the value of my time based on what I accomplished. To finish a year without moving the needle on a work-in-progress is frustrating. But aside from the unseen productivity of lessons learned, I can also see how true it is that nothing is ever wasted.

I didn’t break through my writer’s block this year or finish my outline. But then I remember that in wrangling with that writer’s block this year and trying to figure out how to fix my story, I spent a great deal of time learning about and working with archetypal character arcs. I may not have gotten what I wanted—a Scrivener file full of outline notes for a novel—but I did get a Scrivener file full of outline notes for a new blog series that will perhaps eventually become a book in its own right. (Stay tuned for more on that in the upcoming weeks.)

Building on the Lesson: Really, this is exactly why I rather dislike goals. They tend to fixate us (me anyway) too much on one specific outcome—and if we don’t achieve that outcome, well then, what was the point?

What is true, I think, is that when we show up at the desk and put in the work, something always happens. It may not be what we expected. It may not even be tangible. But nothing is ever wasted.

6. Being a Writer Doesn’t Always Mean Writing (Word Count, Schmurd Count)

Speaking of narrow perspectives, it has come home to me more this year than any year that I have an extremely narrow definition of what it means to be a “writer.” When I talk about “my writing” or “writing time,” I am always talking about writing fiction. Only fiction. And only writing (i.e., not organizing notes, not daydreaming, not proofreading).

Writing Your Story’s Theme (affiliate link)

This was something the pandemic helped me recognize pretty early on last year when I wrote the post “15 Productive Tasks You Can Still Do Even When You Don’t Feel Like Writing.” More than that, I’ve realized how my fiction block these last few years has rather led me to discount the fact that I have been steadily writing all along—every week on this blog and that, indeed, I did publish a book this year.

Building on the Lesson: I have been so identified as a “writer” for so long that any threat to that identity is disturbing. But even more than realizing that I can be a “writer” in many different ways, I realize I must also be willing to broaden my definition of myself. I am not “a writer”; writing is just one of many ways in which I express myself and my creativity.

7. Be Present (You Can’t Repeat the Past or Plan the Future)

If there’s one thing 2020 has taught us it is that everything can change by the time you get to the end of the toilet paper roll. 2020 was what I think of as a “shatterpoint”: the world will never go back to the way it was before. Ironically, this proof of how irrevocably we are always divided from the past makes it more obvious that we cannot ever truly rely on future plans.

This offers a great deal of significance in so many areas of life, but in regards to my own struggles as a writer this year, it offers the reminder that the only thing I can do is be present. However much I may wish it, I can never return to or truly repeat the magic of my childhood relationship to stories. Nor can I decide what my future as a writer will be and demand that my creativity follow suit. I can only be present with what is and try to be as honest as possible in my perception of it.

Building on the Lesson: Really, it is about relinquishing control. Letting go of the past and letting go of the future. I sincerely doubt am totally positive I will not master that one this year. But in between the grief of letting go of the way things used to be and the yearning that the future should be all that we wish it, there is a centerpoint of peace to be found here in the present.

…all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.—Julian of Norwich

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What lessons did you learn as a writer from the adventures of 2020? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 7 Writing Lessons Learned in 2020 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 28, 2020

My Top Books of 2020

There’s a great quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson that I love:

There’s a great quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson that I love:

I cannot remember the books I’ve read any more than the meals I have eaten; even so, they have made me.

And so each year’s tally of books read make up my year as well. I’m always excited to look back and remember what I’ve read and how it’s shaped me.

Not surprisingly, 2020 was a pretty chaotic reading year for me. Only 37 books read, which might be an all-time low. Mostly this is because I spent nearly as much of my reading time thinking as reading—which is a testament to the books.

I didn’t move the needle tremendously on any of my reading challenges. No Pulitzer Prize winners read. And the only classics were Lord of the Rings. But I did read a few books on my histories-of-all-the-countries list, including books on Iraq and (currently) Egypt.

Most of what I read this year was research for my upcoming blog series on archetypal character arcs. It’s one of those subjects that, one you get started down the rabbit hole, you don’t want to stop. But I’ve nearly finished my pile. I’ve mentioned a few of my faves below.

Following you can find my top books of 2020: 5 Fiction Books, 3 Writing Books, and 5 General Non-Fiction Books.

But, first, the stats:

Total books read: 37

Fiction to non-fiction ratio: 10:25

Male to female author ratio: 15:22

Top 5 genres: Social Science (with 16 books), History (with 6), Fantasy (with 4), Romance (with 4), and Writing (with 4).

Number of books per rating: 5 stars (5), 4 stars (24), 3 stars (5), 2 stars (2), 1 star (0).

Top 5 Fiction Books

This wasn’t my best fiction year by any means. I sought out a lot of comfort reads, which although nice weren’t particularly memorable. Those that will be remembered are as follows (all links are affiliate links):

1. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling—Read 2-13-20

Excellent, beautiful, amazing ending to an incredible series. The ending, especially, is fantastic.

2. The Yellow Admiral by Patrick O’Brian—3-13-20

Wandering, as most of the books in the series are at this point, but still utterly beguiling and wonderful.

3. The Fellowship of the Ring by J.R.R. Tolkien—8-27-20

Lacks something of the film’s multimedia majesty and some of the characters come off as less dimensional that I’d like—and, frankly, it’s a bit dull—but it’s a charmingly written and undeniably powerful entry into the trilogy.

4. The Two Towers by J.R.R. Tolkien—11-20-20

While totally bowing to the majesty of the story as a rightful and beautiful classic, I have to admit the first half about the Battle of Helms Deep did not live up to what I was expecting. The second half, however, chronicling Frodo and Sam’s quest with Gollum gripped me on every page.

5. A Darker Shade of Magic by V.E. Schwab—5-28-20

Everything about this book is delicious—the setting, the characters, the magic. That said, it did feel a bit underserved and rushed. I felt like I read the first act, rather than an entire story.

Top 3 Writing Books

Although I always try to have bookmark in a writing-craft book, this year I counted all my archetype research as “writing,” even though most of the books were about psychology or personal development rather than writing. Those books included Joseph Campbell’s Hero With a Thousand Faces and Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey. Of the books I read that were specifically about writing, I have three to recommend:

1. The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron—2-19-20

A transformative and wise book that speaks to healing and growth that goes far beyond any particular pursuit of an art form.

2. If You Want to Write by Brenda Ueland—11-12-20

Such a beautifully inspiring book on so many levels beyond just writing. The middle chapters get a little boggy with examples from Ueland’s writing students, but even they have insights to offer.

3. The Fire in Fiction by Donald Maass—10-21-20

Solid as ever from Maass and full of great advice. One thing I always appreciate from him is that he never softsoaps the truth about what makes a story engaging—or not.

Top 5 General Non-Fiction

My non-fiction interests these days—aside from the archetype research—tend toward depth psychology, philosophy, and history—all of which are reflected in my favorites from this year.

1. A Little Book on the Human Shadow by Robert Bly—10-16-20

It is indeed a little book, but packed full of interesting psychological insights from the unique viewpoint of a poet. Chock full of thought-worthy ideas.

2. The Doctor and the Soul by Victor E. Frankl—11-22-20

The book in a nutshell: Life always has meaning. As so many have over the decades, I found this book deeply inspiring, thought-provoking, and reassuring. The (translated-from-German) language is dense and the subject is often technical, but I found it extremely readable and enjoyable.

3. Awakening the Heroes Within by Carol S. Pearson—8-9-20

Excellent. Twice as good as her first book The Hero Within. Full of insight into life archetypes and arcs.

4. The Dream of Reason by Anthony Gottlieb—3-16-20

Interesting and informative overview of early philosophy. Highly enjoyable.

5. The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown—1-4-20

An incredibly exciting and charismatic story that is very well-told. It’s begging to be a movie.

My Books

And if all these goodies aren’t enough to fill your To Be Read pile this year, here’s a few more!

December 21, 2020

Merry Christmas, Wordplayers!

Dear Wordplayers,

For me, Christmas is always a time of reflection upon the year that has passed, intention for the year that is to come, and especially recognition of the gifts for which I am most grateful.

This year, perhaps more than any other year, I find myself with a deep gratitude for this community of writers. We have talked about writing, we have talked about life. And there has been a lot to talk about this year.