K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 29

July 27, 2020

7 Misconceptions About Being a Writer

Like any good story, the writing life is a tale of deceptive depth. At first glance, it offers up a shiny, artsy, fun cover. Become a Writer! its title beckons, and its first chapters lure us in by fulfilling all these initial promises. But the deeper we get, the further we go, the more we realize there’s more to this story than meets the eye. There’s more adventure, more conflict, more drama, and more comedy than we could ever have realized. In short, there are many different misconceptions about being a writer.

Like any good story, the writing life is a tale of deceptive depth. At first glance, it offers up a shiny, artsy, fun cover. Become a Writer! its title beckons, and its first chapters lure us in by fulfilling all these initial promises. But the deeper we get, the further we go, the more we realize there’s more to this story than meets the eye. There’s more adventure, more conflict, more drama, and more comedy than we could ever have realized. In short, there are many different misconceptions about being a writer.

At the beginning of the year, I started re-reading my old journals, starting from when I was fourteen (because at some point I got embarrassed and burnt everything prior to that). It’s been fascinating to revisit my young self for many reasons, but one of the most interesting is remembering what it was like to be that young writer just starting out—the one who didn’t even know they made books that taught you how to write. I’d all but forgotten what it was like at the beginning of the journey—to be on the very first page of my own personalized version of Become a Writer!

Certainly for me so far, the adventure has been full of surprises, and since I’m now twenty years into this journey and long since complacent with many of the challenges that initially seemed insurmountable, it’s both startling and delightful to realize the story of being a writer is far from formulaic.

7 Misconceptions About Being a Writer

Today, I thought it might be fun to take a look at seven of the misconceptions about being a writer that I used to believe (some of them for many, many years). Some of them were useful in their time and place, if only because they narrowed my options in the beginning and kept me from being overwhelmed by too many options. But each was also a joy to conquer on the way to seeing a much bigger vista on the other side.

1. Writing Doesn’t Count Until You’re a “Real” Writer

This has got to be the most prevalent of all misconceptions about being a writer. (And, in all fairness, the title of this site certainly hasn’t done anything to help!) It begins with the reality that we start as beginners with a long road before us if we are ever to be published, prolific, or even simply professional. But the idea that our writing doesn’t count until we are published, prolific, and professional is simply untrue.

People often ask me what qualifies them as a “real” writer. Publication is the clearest metric. But as my young self learned, that’s not always so clear either. I started out right on the cusp of the indie boom, back when no one had anything good to say about self-publishing (and not without good reason). So I walked a long and winding road on the way to figuring out what qualified me as a “real” writer. Was it my first self-published novel? Was it when I gained a certain number of sales/followers/hits/rankings? I’m honestly not sure where I crossed the line and decided I was a “real” writer. Looking back, I rather think there was no line. There was just the passage of time and the gaining of experience.

I have always disliked the phrase “aspiring writer” or, worse, “wannabe writer.” Rather, “pre-published writer” is one of my favorite ways to talk about the launchpad phase. If you write, you are a writer. And if you are a writer, then you are already a “real” writer. Don’t discount what you write in the early days (and please don’t burn it like I did). You’re no less a “real” writer in the beginning than you were a “real” person in childhood.

2. There’s a Magic Daily Word Count That Proves You’re Disciplined

It’s kind of funny, actually. The writing life is deeply non-normative. It’s different for each of us. And yet writers suffer from comparativitis. Largely, I think this is because the sheer vastness of the creative life puts us all at sea and we look to our fellows to help us understand what might be “normal” and what might not.

Write Away by Elizabeth George

Certainly, there is value in this. Long ago, I remember reading Elizabeth George’s Write Away and finding great comfort in her approach to planning a story—because it grounded my own instinctive approach. But I’m quite sure other young writers read the same book and found it horrifying because it didn’t fit their own instinctive approaches at all.

So it goes with daily word count, among many other things. We’re always sneaking looks over our peers’ shoulders, wondering just how many words they write every day. Do our own habits measure up? Or are we about to discover how woefully undisciplined we really are?

But there’s no secret sauce. There’s no magic daily word count. J. Guenther commented insightfully on last week’s post:

…words per day can be a deceptive measure of progress. I believe that every story has its own natural pace of development. Faster is not always better; in fact, it can be dangerous.

The writer’s mind is not a microwave; it’s more like an imu, the pit used to slow cook an entire pig. It takes time for the conscious mind and the unconscious mind to work together to cook up a fully-balanced, consistent story. Many writers underestimate the importance of mulling scenes over and brainstorming alternatives before putting words on paper.

Some writers write in great swathes of eight or more hours a day, pounding out tens of thousands of words in a sitting. Others poke out bare sentences at a time. Most of us fall somewhere in between. The proof of our discipline as writers is found far less in how fast the words flow from us and much more in the fact that we keep showing up and inviting them to flow.

3. The Rest of Your Life Must Never Take a Backseat to Your Writing

This is one I believed for a long time. My mantras were “treat writing like a job” and “if you don’t take your writing time seriously, no one else will either.”

They were good mantras as far as they went. Certainly, they helped me hone daily discipline. But if we believe these ideas too stringently, we risk either never looking up from our desks or feeling constantly guilty because other parts of our lives do in fact push their way to the front of the line.

During this time of global unease, I have heard from writer after writer struggling with compounded stress because they simply can’t find it in themselves to write like normal right now. But if this pandemic and its myriad tentacles is teaching us nothing else, I think it’s safe to say it’s proving that life follows its own cycles. Some days/weeks/months/years are for writing; some are not.

One of the most joyous lessons I have learned so far as a writer is that the non-writing days/weeks/months/years do not mean I’m any less of a writer. They just mean it’s time to learn something new, to explore, to refill the tank. Indeed, I’d have to say writing only truly works when the “rest of your life” is in the front seat.

4. The Writing Life Follows a Set Roadmap

Maybe it’s just because I’m so linear-minded, but I entered the writing life with this conception that it was a neatly mapped and well-traveled road. As writers advance down this road, they pass a steady progression of milestones—rather like successive grades in school.

Again, to a certain degree this is true. If nothing else, you start out as a beginner, move on to the intermediate phase, and perhaps someday become “advanced.” But beyond that progression, which is affected by little more than time, the writing ride is wild and uncharted.

My journey so far looks nothing like how I thought it would. I also daresay my journey looks like nothing yours, and yours looks nothing like anyone else’s. We come to writing at all ages. We write for all kinds of different reasons. Our journeys to publication (or not) follow many different paths. And even the ebb and flow of our creative interests and motivations are ever-shifting.

If there’s one thing I would say about the writing life at this point, it’s that it’s full of plot twists.

5. Writers Are Wiser Than Everyone Else

In a vague sort of way, I used to think of writers as some kind of transcendent version of humanity. How wise they must be. How different from common mortals. I mean, they have their names on book covers in the grocery store for heaven’s sake.

Certainly those writers whose names are noticed, much less recognized, did have the talent and smarts to get their names on those covers. But at some point, when you realize you are an author, you also realize you haven’t somehow become bigger in order to fit the role. Rather, your idea of “author” becomes quite a bit smaller. You realize that, if anything, being an author is a challenge to learn more—because you don’t know anywhere near enough.

6. Either Writing Is Glamorous or Writing Is for Lazy Bums

Nothing stops dinner conversation faster than telling people you’re a writer. No one ever seems to know quite what to make of it (very possibly because they’ve never before gotten that answer to the “so what do you do?” question). Should the conversation happen to progress past polite grunting, you’re likely to get one of two responses. Either people geek out and think you must be rich and famous with multiple movie adaptations under your belt, or they inconspicuously break eye contact in the suspicion that you’re just covering for the fact that you’re too lazy to have a “real job.”

For most of us, writing is neither glamorous nor a breeze. Very few of us live in a mansion or walk the red carpet. It’s true we often do spend long hours lying around in the hammock or on the couch—but usually in some sort of agonized struggle to break through our story woes.

On the whole, writers are incredibly disciplined people. They’re like body-builders of the imagination—always working, always honing, always subjecting themselves to rigorous self-improvement plans. In fact, writers are some of the least lazy people I know. And we do all this even though we have long since been disillusioned in the notions of glamour. Money, fame, and movie adaptation sound fun, but they’re not why the majority of us do what we do, day in and day out. This quote from Ryan Reudell nails it:

Maybe it won’t be famous. Maybe it won’t be a movie. But that’s not why I started it. And that’s not why I’ll finish.

7. Writing Is Very Serious Stuff

After my first novel came out, I went to the post office to mail review copies. I told the postal worker it was my first book, and he drawled, “What is it—a cheap romance?” Mortified, I rattled off something about how “no, it was a historical novel about duty and justice.”

It took me a long time after that to admit that what I write is genre pulpiness full of swash and, yes, a good dose of romance. But it wasn’t just the deprecating sexism of the postal worker’s comment that made me reluctant to name what I write as “fun” stories. It was also the belief that writing, if it’s to be any good, should be very serious stuff.

Certainly, writing is serious. It shapes our world. Even if no one reads it but ourselves, it still shapes our lives. But writing our stories is a great responsibility, it is no greater a responsibility than is every other word we put into the world. And a lot of those words are just good fun. Indeed, I adamantly believe some of the most powerful stories (for both good and evil) are those that are most entertaining.

These days, if someone asks me about one of my books, I usually jump to the most fun part first.

***

Truthfully, I begin to realize misconceptions about being a writer are never-ending. But I’m also realizing that the more lightly we camp on certain ideas as “gospel,” the more easily we’re able to discard them when they’re no longer of use to us. Twenty years from now, I look forward to reading my current journal—and smiling back at the things I used to believe but have long since outgrown.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What are some misconceptions about being a writer that you used to hold but have grown past? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 7 Misconceptions About Being a Writer appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 20, 2020

4 Questions to Prevent Plot Holes

How peachy would the writing life be if we didn’t have to prevent plot holes. Just imagine—you could write anything you wanted to, and every single thing would make sense. No need to worry about the fact that your two awesome scenes actually don’t make sense side by side. They get to be in the book simply because they’re awesome and fun and you had a blast writing them.

How peachy would the writing life be if we didn’t have to prevent plot holes. Just imagine—you could write anything you wanted to, and every single thing would make sense. No need to worry about the fact that your two awesome scenes actually don’t make sense side by side. They get to be in the book simply because they’re awesome and fun and you had a blast writing them.

Alas, this is not the way of things. Unless you’re writing what George Eliot rather wistfully referred to as “home-made books,” with no readers to please other than yourself, you will eventually have to confront problems of logic that at times seem positively algebraic. As in the famous quote attributed to Tom Clancy:

The difference between reality and fiction? Fiction has to make sense.

And here we thought we were writing fiction to escape reality….

Plot holes, in a nutshell, are those lapses in a story world’s logic when authors either bend their own rules or invent convenient new rules at the last minute in an attempt to explain away seeming incongruities. In a medium as complex as fiction (especially long-form fiction such as novels), it’s little wonder plot holes are relatively common (Jack dying in the Atlantic, anyone?). Sometimes stories are good enough in all other respects for audiences to forgive the lapses—even using them to spawn elaborate fan theories. Other times, plot holes are so problematic or even obviously contrived that emotionally invested audiences respond with downright anger.

At any rate, we all recognize that a master storyteller is one who is capable of telling a complex story that sustains its own logic throughout, avoiding plot holes. This challenge, perhaps more than any other difficulty of writing fiction, is why we turn to tools such as story structure and theory to help us create cohesive and resonant storyforms. But even when our story structure and character arcs are solid, we can still end up struggling with the particular logic of our own stories. This is true of stories set within—and therefore confined by–the real world, and ironically perhaps even truer of speculative stories that offer the fun of creating their own rules of reality—and the often strenuous logic of sticking to those rules.

The longer and more complex a story—especially if it branches into a series—the more difficult this can become. This is why TV shows often end up jumping the shark; if they’re to sustain the characters and story world for multiple seasons, they may have to rewrite their own rules to (try to) keep the conflict fresh and the stakes high.

The other significant difficulty of lengthy fiction (as I’m discovering in writing my first trilogy) is that when you don’t know how the story will end, or even simply if you don’t know some of the major events that will happen before the ending, you will not know how to properly set up your story’s logical parameters in the beginning. And that, right there, is the recipe for plot holes.

4 Questions to Prevent Plot Holes

Whether you find yourself at the beginning of a new story or trying to figure out why your current fictional effort seems to have gone off the rails, here are four questions you can ask to help identify, rectify, or prevent plot holes.

1. Do You Know Your Story’s Ending?

The ending is in the beginning. This is the essence of narrative fiction. Exceptions inevitably end up feeling like my five-year-old niece’s idea of a hilarious joke:

Niece: Knock-knock.

Me: Who’s there?

Niece: Banana.

Me: Banana who?

Niece: Banana… nose! [dissolves into hysterical laughter]

There is a certain joy (and realism) to the “and then!” type of episodic storytelling that throws one event after another onto the stage, but the effect eventually ends up feeling pointless and/or ludicrous (which, granted, can be the point in some types of story). My niece’s jokes are funny enough on their first outing just because she thinks they’re so amusing, but by the time she gets to the fifth one… not so much.

Storyform in general is designed to make a point—to present a cohesive picture of life that, whether explicitly or implicitly, says something meaningful.

This only works when the story’s beginning and ending are part of a whole. The beginning asks a question which the ending answers. The beginning sets up the pieces which will play out in the end. Indeed, entertainment aside, we could argue that the entire point of everything that happens in a story is to set up the pieces necessary for the Climax to play out.

In turn, this means the Climax must play out in a way honoring to everything that has come before it. If the Climax is about noses, then the chapters leading up to this end had better be about noses, mouths, and eyebrows—not bananas. Too many stories meander through their first two acts, only to do a sharp right-angle turn into a Climax that, at best, seems patched on. There is nothing more powerful for readers than the experience of a Climax that flows inevitably and sometimes inexorably from the cause-and-effect of solid setup.

When we do not know how a story may end, we too often end up writing ourselves into corners via our own story logic. For example, by the time you reach the story’s Climax, you may realize you need a character you killed off at the Midpoint. Or you may realize the story’s most resonant ending is going to be tragic rather than happy—which can be problematic if not properly foreshadowed. Or if you’re writing speculative fiction, you may realize your established story physics make it impossible for your fleet of spaceships to reach the climactic battle in time. Whoops.

Sometimes this is unavoidable. As authors, we are not omniscient, even (especially?) about our own stories. Revisions will almost always be necessary at some point in order to make sure every piece of the story works in unison. But the more we understand about how the story will end, the more likely we will be able to avoid writing ourselves into tricky corners.

2. Do You Have a Purpose for Every Character, Setting, POV, Relationship, Scene, Etc.?

No story avoids loose ends altogether. Indeed, those that do, or that try too obviously to do so, often lack verisimilitude because they feel too manufactured. It used to be the fashion to include an epilogue that spelled out the remainder of the characters’ lives, but this robs the story of a sense of continuance. At the very least, it’s often beneficial when a few minor subplots are not completely resolved, so readers get a sense of the characters living on even after the story’s ending.

However, in order to create a story that leads solidly, inevitably, and even profoundly into its Climax, every major piece within the story should be there because it contributes in some crucial way. This is true primarily in the sense that you want every piece to act as a catalyst, propelling the plot to its final end. But it is just as true on the deeper level of theme and symbol. If any particular story “piece”—whether a character, setting, POV, relationship, or scene—exists within the story without expanding upon the theme in some way, it is probably extraneous and perhaps even deadweight.

This becomes more important the more emphasis you put on any particular piece. For example, if early chapters spend a lot of time detailing your protagonist’s relationship with her mother, readers will anticipate this relationship is important to the story. If, however, the relationship does not figure in creating the Climax or, worse, is never returned to at all, then the loose end becomes a plot hole. Readers were led to believe, even if just subconsciously, that the mother was important—and then… she wasn’t.

This, too, can be very tricky, since we sometimes follow rabbit trails in early drafts without fully understanding where they will lead. When they end up leading nowhere, they can already be so deeply woven into the fabric of early chapters that removing them creates other lapses of logic or linearity. This is why it is so valuable to see characters and other story pieces as not just individual pieces but as parts of a whole.

Ask yourself:

What archetypal role is this person, place, or thing playing within the overall storyform?

If it is a role already being filled by someone or something else, can this piece be deleted or combined?

Is it a necessary catalyst and/or symbol?

The tighter your understanding of your story in the beginning, the less likely you will create unnecessary “pieces” that end up going nowhere and creating plot holes.

3. What Is Your Antagonist’s Throughline?

We often forget about the antagonist. He’s a plot device—the stereotypical “bad guy” whose primary story role is to get in the protagonist’s way and create some fireworks in the final showdown. But if we don’t understand the antagonist’s motivations from the very beginning, we cannot set him up properly in the Climax. And if we can’t set up the antagonist in the Climax, it won’t matter how well we’ve set up the protagonist.

This can be particularly challenging when you’re dealing with an off-screen antagonist or with a “Big Boss” antagonist operating from a national or global level. If the antagonist is not the primary relationship character (and this often isn’t the case), then the archetypal dynamic of the conflict can become tricky to represent in a cohesive and resonant way.

Some of the worst plot holes arise because the antagonist is neglected until the Climax when he’s suddenly supposed to show up and counter-balance the protagonist’s thematic argument in a grand finale. Even more obviously, if the antagonist’s motives or methods are phoned in, the story logic almost always suffers. In some ways, the antagonist is the most important factor in creating a coherent storyform. If what the protagonist is resisting and why she is resisting it doesn’t hold water on both a practical and thematic level, the story as a whole will weaken.

When examining the role you envision the antagonist playing in the Climax, it is important to step back and ensure you’ve set this up throughout the story. The stronger the antagonist’s motivations and the more realistic his methods, the more powerful your story’s final meaning. Just as with the protagonist’s actions, the antagonist’s should form a solid line of dominoes, interacting with the protagonist’s throughout the story, until they finally and fully interact—in a logical way—in the end.

4. What Is the Simplest Way to Set Up Your Characters’ Backstories and Motivations?

One of the final problems with not knowing how your story will end is that you may find yourself making up your characters’ backstories—and thus their motivations—on the fly. You know you want your protagonist to be and do certain things because you’ve already envisioned him being and doing those things in specific scenes. So you write the scenes and make up the backstory as you go.

So far, so good. But sometimes, as the story keeps on trucking, you find your character being and doing other things—which require new backstory explanations. Before you know it, you may end up with an extremely complicated story.

The problem of on-the-fly explanations can become even more obvious when you find yourself making up reasons for events, whether it’s the effects of your fantasy’s magic system or just the political ramifications of spycraft.

The best stories may be complex, but they are never complicated. What your characters are doing and why they are doing it should always be simple; you should be able to explain both in a single sentence or phrase. If you find yourself using multiple “and’s,” reconsider whether your story’s background explanations may not have outgrown themselves.

Aside from causing undue complications, this “explanation train” and its multiple cars risks running away from you. If there comes a point when even you can’t keep track of all the whys and wherefores you blithely created along the way, you will almost inevitably end up creating lapses in logic and other thinly veiled (or even gaping) plot holes.

***

Ultimately, all of these questions point to the same solution: creating a storyform that is cohesive from beginning to end and building it with the fewest pieces necessary. When we can do that, we’re not only less likely to create plot holes in the beginning, we’ll also have a much easier time spotting and then figuring out how to prevent plot holes in the long run.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you find it difficult to prevent plot holes? What challenges are you dealing with right now? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post 4 Questions to Prevent Plot Holes appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 13, 2020

An Intuitive 4-Step Process for Creating Vibrant Scene Structure

Creating scene structure is a key writing skill. Great scenes go a long way toward great storytelling; weak scenes result in weak storytelling. Unfortunately, many writers often struggle with vague, sometimes contradictory approaches to writing scenes.

Creating scene structure is a key writing skill. Great scenes go a long way toward great storytelling; weak scenes result in weak storytelling. Unfortunately, many writers often struggle with vague, sometimes contradictory approaches to writing scenes.

A scene should be a complete narrative unit. It should involve a relatively small number of primary characters—except when it doesn’t—in some action that happens in a specific location during a continuous period of time—again, except when it doesn’t. It should include conflict, dilemmas, decisions, and more—but perhaps it doesn’t. As I said… vague and sometimes contradictory.

Over the years, I’ve struggled with applying all this information to actually writing scenes. Trying to explain it to creative writing students is even more difficult. It was only when I began to study the structure of comic books and graphic novels that I began to get a picture—both literally and figuratively—of how to construct scenes. My first efforts were done in a graphic-novel style, but I soon figured out the approach also works well for text-based stories.

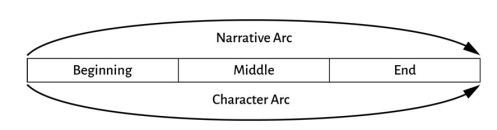

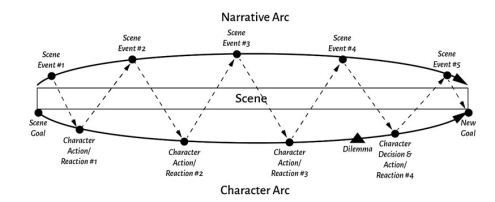

Narrative Arcs vs. Character Arcs

When writing scenes, understanding a narrative arc versus character arc is important. They are not the same thing. The narrative arc—a term I prefer over “story arc”—emerges from a series of events that occur over the course of a story (or in our case, a scene). A character arc, on the other hand, is the result of changes that occur in a character over the course of the story or scene. The best stories have both arcs.

Figure 1: Narrative and character arcs (Image by Peter von Stackelberg)

Scenes should also have both arcs—the narrative arc’s scene events (aka, “actions”) and the character arc’s goals, dilemmas, actions/reactions, and decisions. The interplay of these elements across the two arcs drives the narrative, whether it is a scene, sequence, act, or entire story.

Figure 2: Interaction between the narrative and character arcs (Image by Peter von Stackelberg)

I’ve found that building a scene often involves identifying the main character’s scene goal and then setting up the narrative arc, basically writing “This happened…then this happened…then this happened…” until I reach the end of the arc.

The main character’s arc across the scene can then be developed by elaborating on the scene events. For example, “This happened… causing the character to do… then this happened… and the character did… then this happened, creating a dilemma for the character, who then did… causing this to happen and creating a new goal.”

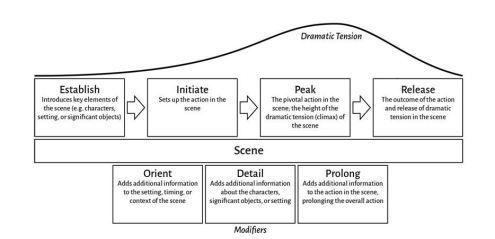

Scene Structure & Visual Language

A framework for creating scene events that drive the narrative arc can help the writing process. I found that framework in research being done into visual language—how information in the form of pictures is structured. Neil Cohn has identified four key components that make visual scenes understandable. Cohn also identified a number of components that he calls “modifiers,” which provide additional information in visual scenes.

Figure 3: Core and secondary elements for visual and text-based scenes (Image by Peter von Stackelberg)

I’ve adapted these components into a framework that can be used by writers to create narrative arcs for both visual and text-based scenes. The four core elements are:

1. Establish

The first element in a scene introduces key aspects of the scene’s setting, characters, and significant objects. Its purpose is to introduce readers to the scene and help them understand the who, where, and when before the action begins. In visual terms, this could be considered an establishing shot that shows the environment and the characters’ place in it. In text-based stories, this element is often called the set-up.

For Example: A description of the bar, its clientele, the time of day; some reference to the key character, although the primary focus is on the environment.

2. Initiate

The second element is often preparatory activity setting up action that will occur in later in the scene. It ratchets up the dramatic tension and provides readers with information needed to understand what is about to happen.

For Example: Our protagonist goes through the swinging doors, moseys up to the bar, and orders a drink, somehow offending another character in the process. The characters interact and words are exchanged. Tension rises.

3. Peak

This is the climax of the scene, where dramatic tension is highest. The Peak is when the scene’s pivotal action happens.

For Example: Suddenly guns are pulled and blam, blam, blam… the pivotal action happens. A brief dramatic pause leaves readers wondering who caught the bullet.

4. Release

The final element is the Release, which wraps up the scene and shows the aftermath of the pivotal action. At this point, the dramatic tension is released, and the scene ends.

For Example: The bad guy slumps to the floor in a pool of blood, and the scene closes.

3 Additional “Modifiers” for Your Scene Structure

The Peak is the most important element in helping readers understand what is happening. Release is the second most important. The Initiate and Establish elements, while still providing important information, do not have as significant an impact on the readers’ ability to understand the scene if eliminated from the story.

The order of these elements—Establish>Initiate>Peak>Release—is important. Scrambling them reduces the ability of readers to follow the sequence of events and understand the scene.

Most sequential art and written scenes have more than just the basics outlined in these four elements. Cohn identified several “modifiers,” which I’ve condensed into three secondary elements:

1. Orient

Additional information about the setting, timing, or context of the scene that helps readers better understand the where, when, and who of the scene. It helps orient them to what is going on. This information usually follows the Establish element and elaborates in some way on what we have already presented to the audience.

2. Detail

Additional details about characters, settings, or significant objects. These details are usually part of an Initiate sequence but may also be used sparingly during the Release to provide necessary information.

3. Prolong

Additional actions in the scene that prolong the overall action. A Prolong can be used to create suspense, which heightens the scene’s dramatic tension. Prolong will typically be part of an Initiate. If you use Prolongs in a Peak, do so sparingly. You don’t want to drag things out too long. Do not use Prolongs in a Release sequence. Once you’ve hit the Peak, the outcome should be presented without delay.

Scene Structure as a Writing Template

Writers can use these elements as a template to guide scene creation. When working with students who are struggling to write a scene, I have them begin by focusing on the Peak while temporarily ignoring all other elements in the scene. Once the Peak is drafted, then the images and/or text for the Initiate, Release, and Establish elements can be dropped into place.

The thought process I have them walk through is:

What is the Peak action?

What set into motion the Peak action? What is the Initiate element?

What is the result of the Peak action? What is the Release?

Where did this all happen? When? Who was involved? This is the Establish element.

When a draft based on the Establish>Initiate>Peak>Release framework is done, a preliminary character arc is easier to develop by then responding to the scene events. More details can be added to both the narrative and character arcs to flesh out the framework and add more depth to the scene.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your favorite way to think about scene structure? Tell us in the comments!

The post An Intuitive 4-Step Process for Creating Vibrant Scene Structure appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 6, 2020

How to Get Stuff Done as a Writer (or How This INTJ Leverages Her Te)

Most days as a writer, I wake up excited to tackle everything on my to-do list. My big plans always include ROCKING my daily writing session. I’m always like, “Today is the day I’m going to write 5,000 words in one sitting! Rawr!”

Most days as a writer, I wake up excited to tackle everything on my to-do list. My big plans always include ROCKING my daily writing session. I’m always like, “Today is the day I’m going to write 5,000 words in one sitting! Rawr!”

Then writing time rolls around. And… I’m still futzing around the house, weeding the garden, finishing my shower, getting my snack ready. So I’m usually about fifteen minutes late. Then I sit there. And I fiddle with that one button on my keyboard that’s always falling off. Or I decide I need I need to go clip that hangnail on my thumb. Or I pop open a research file to check something—and get sucked in to reading it for thirty minutes.

In short, figuring out how to get stuff done as a writer is sometimes the single hardest part of the job. We all have personal weaknesses that sucker us into wasting time over and over again. As an INTJ in the Myers-Briggs personality typing system, I’m aware that my type is notorious for getting sucked into “analysis paralysis.”

Two weeks ago, I talked about how writers of any personality type can optimize all four of the primary cognitive functions (Intuition, Sensing, Thinking, and Feeling) to enhance our writing capabilities. In the post, I quoted a question I’d received long ago on Twitter from Victoria Nelson (@ledinvictory), who wrote:

Hi! I believe that you’ve mentioned that you’re an INTJ (as am I). Do you ever find yourself caught in a perpetual Ni [Introverted Intuition] phase—the joy of planning/outlining? (I can build bigger and bigger plots & fantasy worlds forever!) And if so, how do you force yourself out and into a Te [Extroverted Thinking] space? This might make an interesting article if you think it would be widely interesting enough for others… Otherwise, I’m always trying to balance the two, not so successfully.

Some of you expressed interest in a full-blown Extroverted Thinking (Te) post. So here it is! For those who aren’t INTJs (and for those who have no idea or care what that is), don’t worry—all the tips I’m going to talk about later in the post can be used by writers of any type to get stuff done. But for those who are INTJs or otherwise interested, here’s the technical intro…

Why INTJ Writers Must Leverage Te to Get Stuff Done

C.G. Jung’s theory on cognitive functions assigns all people four functions—two introverted and two extroverted. These functions are then “stacked” in an alternating order.

If your top function is introverted, then you are considered an Introvert in this system, and vice versa.

If your Judging function (Thinking or Feeling) is extroverted, you are designated a Judger. If your Judging function is introverted, you are designated a Perceiver.

Hence, an INTJ’s functional stack looks like this:

Introverted Intuition (Ni)

Extroverted Thinking (Te)

Introverted Feeling (Fi)

Extroverted Sensing (Se)

All types feel most at home in the “attitude” (Extroversion or Introversion) of their dominant function. This means that even though our secondary function is more cognitively developed than the tertiary function, we sometimes find it more comfortable to drop down into the less mature tertiary function—since it always operates from the same attitude as our dominant function. (You’ll note the secondary and tertiary functions are always part of the same polarity—making them both either Judging or Perceiving functions.)

This isn’t always problematic, since all the functions are important and offer important capabilities. However, when we consistently bypass our secondary function and its opposite attitude, we end up in what is called a “loop”—endlessly chasing our own tails, stuck in either our Introversion or our Extroversion (depending on which is dominant). This loop inevitably creates problems. For Introverted types, such as the INTJ, the problem is that we get trapped inside our own heads—looping endlessly between Ni and Fi.

This is the “perpetual Ni phase—the joy of planning/outlining” that Victoria was talking about. This is where analysis paralysis can get all too real because however great our ideas, we never get anything done.

For INTJs, part of the difficulty is that we tend to view life and all its problems as a giant chess game—and we don’t like to make even the first move until we’ve played the game out in our heads and know how it’s going to end. As writers, this can lend itself to powerful planning and outlining skills, which in turn (sometimes) help us avoid major rewrites and revisions. But when dealing with something as monumentally complex as a novel, this proclivity to endless planning can also mean we’re never satisfied enough with our planning to actually start writing.

I doubt it surprises anyone who frequents this blog to know I’m an avid outliner, spending roughly a year on the planning process and ending up with completed outlines that can be almost half the word count of the first draft itself. And it works—most of the time. Most of the time, this is a process that allows me to fully leverage my planning proclivity as my greatest strength. It allows me to create solid outlines that, when everything’s truly humming, mean I can write first drafts that require very little editing. It’s also an approach that has saved me from pouring time and energy into stories that were never going to work because I was able to play out the mental chess game all way through to the end without actually having to put in the time and effort of writing a first draft.

However, there are times when the planning gets out of hand. I’ve been at work on my current outline for over a year now, continually circling some major plot difficulties, trying to plan my way out of them so I can finish my fantasy trilogy. At this moment, I still believe I’m going to find the solution, but I also know I may just be stuck in analysis paralysis and that a writer of a different personality type might have pulled the plug long ago.

4 Ways Writers Can Leverage Their Extroverted Thinking

So now you may be wondering, how do you get out of this “loop”? The answer is learning how to consciously strengthen and leverage your secondary function—Extroverted Thinking, in this particular case.

Whatever your type, the loop stops the moment you bring your secondary function back online. However, depending on how comfy you’ve been in your loop and how deep a habitual rut you’ve created, this can take some doing. Developing your secondary function often requires doing some serious self-work, examining your own resistance (e.g., INTJs often have a lot of resistance to moving out of the planning phase, even when they really do want to finish the book), and even acting in certain ways that may feel uncomfortable or scary (e.g., Introverts often find it scary to “extrovert” enough to put a book out there in the world, just as Extroverts can initially find it uncomfortable to practice deep introspection).

But it’s worth it. When your secondary function is operating at full strength, your full skill set really comes online. Your work becomes more dimensional. And if you’re an INTJ—you get stuff done.

Here are some simple strategies that have made a huge different in my ability to develop my Te, use it to balance my need for analysis and planning, and access it to move the needle on my goals.

1. Trust Your Intuition to Know When It’s Time to Move Forward

People often ask me, “How do you know when to stop outlining and start writing?” The simple answer is, “When the outline is done.”

But knowing when that is requires the ability to accurately judge yourself, your motivations, your resistances, and your work. Turn that gift of analysis back onto yourself. Why are you resistant to moving on to the first draft? The reason could legitimately be that there is more work to be done in the outline. But it could also be that outlining is more fun, so you’d just rather stay right there.

To know when you’ve reached the end of an outline’s usefulness, focus on specific questions you have about your story. For me, the early brainstorming part of outlining is essentially a game of filling in the blanks. I start out with a few known points about a story and start asking questions about the dark spaces in between—until there are no quantifiable dark spaces left. When there are no more legitimate questions standing between me and a functional plot, then I know it’s time to move on.

An understanding of story structure can also prove helpful in knowing when the story is “finished.” The major structural beats can function as a checklist. Once you’ve created a solid structural spine, then you know you have your story. Structure is always specific, not vague, which is a massively helpful tool for INTJs to leverage in moving past their tendency for abstract thought.

2. Focus More on Short-Term Goals

INTJs like to play the long game. We don’t live in the present; we’re always minutes, days, weeks, even years into the future. And once we imagine what will be, it often already feels like it’s done. This means we sometimes lose incentive to actually do the thing. (Ah, the irony of being an amazing planner and a so-so doer.)

For this reason, it is often more helpful to put our focus into short-term goals rather than long-term goals. If you know your long-term goal is to “finish the book,” just hold that loosely in your mind. Use your planning skills to envision the steps necessary to get there, then focus all your energy on the one right in front of you.

3. Move Into Your Fear—Every Day

Much of the reason INTJs get stuck in the analysis paralysis of their introverted loop is because, as folks who prefer the Introverted attitude, its much easier to think about things than to enact the much more difficult and sometimes scary business of impacting the external world. This is especially true if we feel we haven’t properly thought things through (aka, considered every systemic and causal possibility that might occur from now to the day the sun explodes).

By its very nature, Te is about pulling the trigger and acting. INTJs who learn to develop this powerful function will find a wealth of resources right at their fingertips. But first you gotta get into the habit of actually pulling that trigger. Take risks. Trust that your intuition actually improves when you let your Te test your theories.

To this end, it can be helpful to make it a goal to do one small thing every day that moves you into your resistances and fears. This might be as simple as letting someone else read your story for the first time. One of the biggest first steps I took as a young writer was joining a writing forum and offering up my story for critique.

4. Fill Your Think Tank Daily, But Don’t Go Down the Brain Drain

INTJs are information connoisseurs. We can’t get enough. Our dominant function, Introverted Intuition, is a perceiving function, which means we’re most at home just sucking in information. But this, too, is part of analysis paralysis. It’s super-easy to bury ourselves in the “work” of research, always believing we need just a little more information before we’re ready to write the book or share the idea.

It’s important for INTJs to feed their Intuition on a regular basis. But I find it’s best to limit the time I spend reading and learning. I put it on my daily to-do list like everything else so I get a little of what I need every day, and then I move on to the tasks where I can put that information to use (or, rather, where I can eventually put it to use—because, let’s be honest, it takes INTJs a looooong time to process information).

Intuition is a deep well, but it must be regularly topped off if it’s to provide the necessary resources for Te to get stuff done in the outer world. This may sound obvious, but I can attest that if you get too enthusiastic about using Te, you can run the well dry. The key is finding the balance between feeding your brain on a daily basis without letting it glut.

***

Sooner or later, procrastination is a stumbling block for most of us. Each of us must figure out how to get stuff done as a writer. Whatever your type, the fact that you’re drawn to storytelling means you may have a tendency to prefer living in your head to actually doing the writing. Learning how to activate all your skills and harmonize them into a powerful team of opposites can help you create a holistic writing process that takes advantage of all your gifts.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What are your top tricks to get stuff done as a writer? What have been some of the major challenges you’ve overcome? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post How to Get Stuff Done as a Writer (or How This INTJ Leverages Her Te) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 29, 2020

The 3 Acts of a Writer’s Life–Or How Your Age Affects Your Writing

I’ve been writing consistently since I was twelve, which means I’ve now been writing for the (amazingly long very short?) period of twenty-two years. In that time, almost as much about my writing has changed as has remained the same.

This is something I’ve been casually pondering for a while now. Then, last week, I received the following email from David Hall:

Down the street I can see 70 years coming toward me. A few more months and it will be impossible to avoid. Have you ever discussed age and how it affects the material we write?

For starters, let me say that this one of my favorite types of email to receive—those sent to me by older writers who are either just starting out or are still going strong. With this year’s birthday, I will reach the moment in my life where fifty is as near to me in the future as twenty is in the past (and since I still feel like I’m a seventeen-year-old who was somehow given a fake ID, I’m experiencing a mild case of shock over the realization). It is deeply inspiring to me to realize how much can yet be accomplished in the years still before me.

I’m also beginning to realize that whatever those years bring, I will almost certainly be surprised by their offerings. Certainly, the effects on my experiences as a writer are vastly different to me as an adult than they were when I was a child. Indeed, since I never expected things to change at all in that regard, the differences I’ve encountered have all been tremendous surprises, sometimes disturbing, sometimes delightful.

Although at present, I can offer only a limited amount of personal insight into the how your age affects your writing (no doubt David could offer a good deal more himself), since I was asked I thought it might be a fun topic to explore. This is especially so in light of the fact that the readers who frequent this site present a vast variance in age—and also because this is, inevitably, a topic that touches us all.

The Three Acts of the Writing Life

Interestingly enough, this idea of life evolution and how age affects our perspective of and impact on life is one I’ve lately been exploring from the lens of story theory. As I’ve teased a few times on the podcast, I’m currently wrapping up research for a new blog series that will explore successive archetypal character arcs, which are representative of the seasons—or acts—of life.

As a sneak peak, since it ties in with today’s subject, I believe we see the pattern of story structure’s Three Acts played out in the typical human lifetime—in which approximately thirty years comprises each act.

The First Act—roughly, our first thirty years—is largely about defining our relationships with ourselves and our own personal identities. When the archetypal arcs of those years are properly completed, they lay the foundation for healthy arcs in the following acts.

The Second Act, made up of roughly the next thirty years, is focused on our relationships with others—friends, mates, children, community.

Finally, the Third Act—what for most of us will be the last thirty or so years in this life—then becomes the climactic act, which focuses on our relationship to Life and Death itself, in all its transcendent mystery.

Even though I began studying these “life arcs” as a way to further develop my understanding of how to structure my characters’ arcs in the most resonant way, the reason these arcs are archetypal is because they necessarily first apply to our own lives. Because I can already see the First and now the Second Acts playing out in my life, I believe the archetypal principles of the Third will ring true as well.

The Writing of Youth: Writing to Ourselves

Why We Write: In both my young self and in the many young writers with whom I regularly interact, I see the ebullient joy of creation simply for creation’s sake and a sort of desperation—as represented in Jo March’s statement (from the 1994 film adaptation of Little Women):

Late at night my mind would come alive with voices and stories and friends as dear to me as any in the real world. I gave myself up to it, longing for transformation.

We start writing for the pure joy of it, whether it is the joy of fantasizing ourselves into the midst of miraculous adventures or the cathartic joy of our angst poured out in characters who are deeply intimate projections of ourselves.

What We Write: When we are young, writing is an exploration. I daresay the young dislike the stricture that we should “write what we know” more than any of us. After all, the only things we know at that age are what we write.

And we write all kinds of things—fantasy, romance, adventure, even serious social dramas. We are perhaps never more derivative than in the beginning, as we begin inhabiting and owning the stories of others which have first carried us away with ourselves. But we are also perhaps never more original than at this age—when everything is new. When I look back at the stories I wrote in my First Act, there is a special freshness and passion within their rawness and clumsy technique. For all that my adult novels are technically “better,” they are not stories I inhabit in the same way I did those early ones.

How We Write: We write like Jo March, scribbling madly away into the night. However much we may desire the approval and enjoyment of early readers, we write these stories for ourselves. We write, not because it’s a job, not because we’ve made it a goal to show up at the desk everyday, but because we want to. We write ourselves bleary into the night and think it the greatest fun of all.

We write with varying degrees of control and technique. If we pursue our writing diligently as time rolls on, we begin to discover that writing is not simply the breathing of one’s soul upon the page. It is, indeed, the art of communication, and that however innately talented or imaginative we believes ourselves, we aren’t actually that good at it. The angsty teenage years begin in earnest, affecting our writing as much as anything else, and we begin to take it all very seriously.

The Writing of Adulthood: Writing to Others

Why We Write: Well into my twenties, I insisted I wrote for myself and that I would continue to write even if I knew no one would ever read what I wrote. Although I still (mostly) stand by that, I have witnessed a distinct change in myself here in my mid-thirties. My Second Act has seen me grieve for and grapple with the fallen expectation that my relationship to my writing would always be as ecstatic as it was in my First Act. More than that, I’ve surprised myself by realizing that not only do I now write as much for others as for myself, but that it is important to me to do so.

If writing in the First Act was all about my joy in expressing and exploring myself, writing in my Second Act has brought with it the increasing awareness of my responsibility in relating with others and, indeed, my great desire to use writing to have a positive impact on my world. “There’s no such thing as just a story”—this statement began in my twenties as a passionate defense of the idea that my stories were an important part of my life, but has since transmogrified into an even more passionate belief that every word we write—fictional or not—is a catalyst either for good or for ill.

What We Write: The blaring passion of our early stories gives way to a more deliberate pursuit of meaningful resonance and purposeful originality. Although we may well “have just one story to tell and go on telling it over and over again in different ways,” we grow significantly more refined in our execution. The type of stories we tell may change entirely. The more ground we cover the more we may branch out, experimenting with how to share our enduringly passionate truths in original ways that avoid treading the same ground.

We become more conscious of the symbolism and themes that populate our stories. We understand what we are writing more clearly, to the point that ideas we would have blithely written about in the First Act are now rejected or perhaps just honed.

If we’re writing professionally, we’re also writing for others not just as a communal whole, but as customers. We’re constantly trying to find that balance between the old youthful enthusiasm, the demands and desires of the market, and our own purposeful convictions about the nature of art. In my experience of the Second Act so far, that is the hardest balance to perfect.

How We Write: For those of us who began writing in our First Act, we have the blessing of years of experience and learning behind us at this point. We’ve made mistakes and learned from them—both in style and in process. We’re perhaps at the stage of “knowing what we know.”

But that same experience that allows us to easily avoid the beginner’s mistakes can also lead us to burnout and repetitive fatigue. Some of the methods that served us well in the first blush of youthful passion no longer come as easily. We have to reconnect with the inner child, with the deep motivations that brought us to writing in the first place. We have to learn how to harmonize the child and the adult into a new synthesis that is built upon the past but also completely different from what we may have taken for granted would always be our own particular creative experience.

The Writing of Age: Writing to the Universe

Why We Write: As we enter the Third Act, I imagine we may well find ourselves having proven—to ourselves and to others—many of the challenges that seemed so vital in our early acts. There is a return of sorts to the old stomping ground of the First Act, when we wrote purely for ourselves because we wanted to and because it brought us joy. But now we write from the vantage of long years of experience and knowledge.

The passionate stories we wrote as children were questions we asked of the life that lay before us. Many of those questions have now found their answers. Now it is something else that lies before us and new questions that our stories ask. So I imagine we write both for ourselves—to ask these larger questions—but also for others—to leave to them some of the answers we have found.

What We Write: I think there is a period late in the First Act and throughout most of the Second when we care zealously about how our writing will be received and what sort of impact it may make on our readers. But I also think that at a certain point we don’t care as much. Authors in their Third Act aren’t as rigorous with their form anymore. They begin experimenting more. They are asking questions again rather than just filling in the expected answers, and these questions show up in how they treat the actual process of writing as much as anything else. There is a playfulness that may not have been fully present previously.

Too, I see in many older authors a deeper passion than ever before. Their time is limited. Their own life stories are coming to a close. They have only so much longer to share the stories that are important and to give to the following generations—of both readers and writers—the truths they have won in their own hard-fought battles. If our Third Act sees us sometimes more playful than we have allowed ourselves to be before, it may also see us more intense than ever.

How We Write: After a lifetime of writing (or even just a lifetime of living come to that), there is a good deal of instinct that naturally flows through us. Techniques we struggled with in the First and Second Acts are long since mastered. If story itself remains an affectionately unruly beast, it is perhaps one we no longer view with the same frustrated suspicion we sometimes did in our earlier life. Perfection may both come more easily and, in some measure, be less important. We’re now writing less because we have something to prove to the world and more because we have something to share.

***

In closing this post, I realize even more than when I began it that I’m massively unqualified to have written it, since more than half of my ideas about it are total conjecture. Still, it has been a thought-provoking exercise and roused a hopefully not-too-idealistic anticipation of what the rest of my Second Act and all of my Third Act will bring for me as a writer. Since we are all at different points in our life stories, I hope you will share you own insights into how age affects your writing—both in its challenges and its opportunities.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How does age affect your writing? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)

The post The 3 Acts of a Writer’s Life–Or How Your Age Affects Your Writing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 22, 2020

Using All Four Cognitive Functions as a Writer

My heart is so full as I write this. So many things going on in the world right now—both good and bad. It makes me reflect, not for the first time, on the tremendous gift given to writers in the simple fact that we have a place to put not just our feelings, but every other aspect of our cognitive experiences as humans.

My heart is so full as I write this. So many things going on in the world right now—both good and bad. It makes me reflect, not for the first time, on the tremendous gift given to writers in the simple fact that we have a place to put not just our feelings, but every other aspect of our cognitive experiences as humans.

(Right after I write this opening paragraph, a doe and her fawn gallop across my front yard, right out my office window, and my heart grows a little fuller with the good stuff.

June 15, 2020

Does Your Story Really Need That Extra POV Character?

[I’m taking a quick break this week to deal with some personal stuff (no worries—everything’s good!), so decided to share a short post some of you may remember from the e-letter years ago.]

Sooner or later, most authors find the constraints of POV frustrating. It can be difficult to observe the strictures of a tight POV while still showing readers all of a scene’s necessary information. Seemingly, one of the easiest ways around this problem is to simply add a new POV from a character who is able to share the information you want to convey.

However, it’s always wise to think twice before adding another POV character.

Let me share an example.

A fantasy I recently read featured two 3rd-person POVs from its two major characters. But as the story neared the Climax, the author inserted several POVs from minor characters who never again appeared on stage once their brief moments in the POV limelight were complete. By adding these viewpoints, the author was able to give readers some inside information that his main characters couldn’t have shared. But he also lost the sense of cohesion that had carried his story so well up to this point.

Inserting one-time-wonder POVs, especially late in a story, and especially those that highlight a character readers are meeting for the first—and perhaps only—time isn’t a sin most readers will want to shoot you for. But writers need to be aware that POV is the glue that holds their stories together. If you dilute it, even to impart what may seem like vital information, you’re going to be distancing readers from your characters. You’re may also confuse readers, while loosening the tight weave of your narrative.

When you find yourself late in your story and tempted to add a heretofore unnecessary POV, ask yourself if the information this POV imparts is really as vital as you think. In many cases, you may discover the information might be more powerful and memorable if the readers learn the information at the same time as the main characters.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you decide when to add a new POV character to your story? Tell me in the comments!

The post Does Your Story Really Need That Extra POV Character? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 8, 2020

6 Writing Excuses Busted (Or How an 11-Year-Old Published Her First Novel)

Writing excuses are easy to come up with. Easy to justify.

Writing excuses are easy to come up with. Easy to justify.

But to publish, you’ll need to learn how to avoid using at least six of them—maybe more. My goal is to help you avoid using these six writing excuses by showing you how I overcame them to publish my first novel shortly after my eleventh birthday.

Writing Excuse 1: I Don’t Have Time

Deadline time. I knew to finish on time I’d need to wring every ounce of writing time I could out of life. I quickly washed a potato, threw it in the microwave, and hurried back to the computer to type until the microwave timer beeped. I flipped my potato, rushed back to the computer, and typed until the next beep. Butter and salt for flavor (and inspiration), then back to the computer, taking bites of food in between bursts of thought.

If you want time to write your book, you’ll need to take it wherever you can. Lack of time is probably the biggest issue authors face, which is why I mention it here first. So how can you fit writing into your schedule?

Wake up early

Like, really early. If I wanted to get any writing done in the mornings before school started, I had to get up at six AM and write until seven when the house started to stir.

Work late

Time and again my parents let me stay up until nearly midnight frantically typing. They mostly forgave my grumpiness the next morning.

Cut distractions

While my siblings watched TV or read books, I learned to keep working to bring my story to life. This eventually became a habit, and to this day I often create worlds while my siblings watch someone else’s. What little things take away your free time? Social media? Gaming? Sacrifice these and you’ll find you have more time than you realize for writing—and you won’t even miss those other things.

Writing Excuse 2: I Can Wait Until Later

I started Phoenix Feathers because my dad challenged me to NaNoWriMo—National Novel Writing Month—on October 25th. It would have been easy to wait until November to start. But I was like, “Why wait five days for no reason? Can I start now?”

In those first five days, I finished about a chapter a day. Thanks to un-procrastination, I finished the rough draft of my 30,000-word book five days before the end of November.

Not saying I’m scot-free from procrastination. I had about three weeks to complete this post. I kept putting it off in favor of other projects, thinking, “I have plenty of time.”

I finally started two days before deadline. I’m confident saying it’s a lot better being ahead of schedule. At least you’ve started that way.

Writing Excuse 3: I Don’t Know How to End My Story

You know the feeling. You start with a promising setting. Great characters. An intriguing storyline. Then the story dries up because you don’t know where you’re going.

I learned this through sad experience. My brother’s metal modeling sets inspired me to write a book (Metal Earth) about a planet made of metal. Great setting, but I didn’t know where my story was going. I had no outline, no plot, and no destination. Just vague ideas.

Disaster. I floundered after a few chapters. It was like writing with my eyes shut.

I also started Phoenix Feathers without an outline, but my dad knew about my first novel attempt and told me an outline would help.

After I wrote my outline, I had guidelines and a destination while leaving plenty of room to surprise myself with plot twists. It became a lot more fun after laying the right foundation.

Same thing happened with this blog post. No outline, no progress. Full intimidation. With an outline, it became easy and fun.

Moral: Learn to outline, dude.

Writing Excuse 4: I Lose the Flow of My Own Story and Forget Things

Losing the flow happens to everyone. For me, it’s usually when I’m inactive on a book for even a few days. With poor Metal Earth, it became hard to drop back into the story after weeks away. The story flow went kaput.

However, it’s hard to write every day. Maybe you just don’t feel like it. You’re bored of your own story. I get that feeling a lot.

Consistency is the only thing that breaks this down, and that’s the reason NaNoWriMo is so powerful. I wrote probably three and a half hours per day every writing day of that month, and I never lost my place or forgot what I was writing about.

How can you develop your own habit of writing consistently?

Writing Excuse 5: I Have No Motivation to Write

You can break this feeling down with persistence and a little bit of … self-motivation. Let’s just call it a bribe.

With NaNoWriMo, I probably couldn’t have finished in time without “THE BRIBE.”

I alluded to the bribe in my dedication of Phoenix Feathers. My dad offered to buy me and my brother a $20 Lego set each if we completed our books before the end of National Novel Writing Month.

Now, a $20 Lego set for writing a book in a month seemed pretty good to me. But here’s the reality: Sometimes I dogsit a really cute Golden Doodle for $10 an hour. Two hours of that and I could buy my own Legos. We estimate I worked at least 100 hours on my rough draft. If I dog-sat for as long as I worked on my book, I would have made $1,000 dollars last November.

I got a $20 prize and a shiny new novel. It was a way better reward.

The novel was the thing I needed, but the Lego set is the thing I wanted. It’s just tricking your mind by providing the right motivation.

It doesn’t need to be big, but reward yourself with something at big milestones and keep envisioning holding a printed copy in your hands. When I finally got my first author’s copy in the mail, I ran downstairs giggling and hugging my book to my chest. That’s reward enough if you stick with it.

But it could be as simple as promising yourself a favorite snack between chapters or as big as taking a vacation when you type “The End.”

You can also find more subtle means of convincing yourself to write every day.

I’m competitive. Since my big brother was also doing NaNoWriMo, we turned it into a race. Who could type longer? Who could finish a chapter faster? If you know anyone else writing a book, challenge them to a contest. Awaken the fierce desire to win.

Don’t know another author? Challenge yourself by setting goals. Daily word count. Typing speed per chapter. Making your fingers fall off from typing so fast (okay, maybe don’t challenge yourself that much).

Small goals and rewards will push you through doldrums days until you have a good habit that carries you far beyond.

Writing Excuse 6: I’m Not Good Enough

When I started writing Phoenix Feathers, I didn’t know how to type. I wanted to write it by hand, but my dad wouldn’t let me. Most authors don’t have this problem, but I had never really touched a computer. Typing Metal Earth was eight pages of painfully slow pecking, and that was my first real experience with typing.

I complained to my dad while writing Phoenix Feathers: “I have so many ideas and I just can’t type them out fast enough!”

Slowly, though, I sped up. This post went much faster than any page of Phoenix Feathers did. My dad, a professional speed-writer, now calls me “competent.”

With any writing difficulty, work at it until it crumbles.

You might wonder why I saved the “not good enough” excuse for last—especially when established writers still have a hard time valuing their own work when they’ve read so many good books.

I have a natural gift for speed-reading. When I’m in the right mood, I’ll read about thirty full-length novels per month. One of my earliest memories is peering over my dad’s shoulder as he read a Hardy Boys book and wondering why he read so slow. And my dad is a pretty fast reader.

With all the good books I’ve read, I could’ve been intimidated by other authors. Instead I realized I’ve learned grammar, story structure, and creativity from other people’s work. No need to compare my work to theirs.

I actually thought, “I’ll never create something like Lord of the Rings, so why compare?” (I read the trilogy probably three times a year.)

Don’t ignore thoughts of not being good enough, but don’t let them hold you back. Imperfections and all, your writing will be yours. And if you have the occasional cliché, it’ll be your cliché.

***

You’re more ready to write your book than you think. If I can do it, anyone can. You’ll love holding that first book in your hands. End of story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What are the biggest writing excuses you find yourself battling? Tell us in the comments!

The post 6 Writing Excuses Busted (Or How an 11-Year-Old Published Her First Novel) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 1, 2020

11 Exercises to Enhance Your Visual Thinking

Which comes first for you—images or words? For storytellers, both are important. We craft words on paper to communicate our visions to readers. We want them to see what we see, hear what we hear, experience what we experience. Concentrating on visual thinking is an exercise many of us can use to access our creativity and write better stories.

Which comes first for you—images or words? For storytellers, both are important. We craft words on paper to communicate our visions to readers. We want them to see what we see, hear what we hear, experience what we experience. Concentrating on visual thinking is an exercise many of us can use to access our creativity and write better stories.

I think in pictures. I think in words too, but even then I usually see the words floating through my head (in a serif font…). Like C.S. Lewis and his photographic flash of a faun with an umbrella carrying parcels in the snow, almost all my story ideas come to me as images. When I was young, I overlay everything in my daily world with pictures from my innerscape—wild horses ran alongside the highway on car trips, moonlit nights turned my backyard into a secret labyrinth, automatic doors at the grocery store proved my Jedi mind powers (okay, so everyone does that one…).

It was glorious.

However, I find that my adult brain is less visual than it used to be. I haven’t lost the ability to see druids in the woods or outlaws in a storm, but what used to be the constant daydreaming of childhood has been largely relegated to the dusty attic along with the other nostalgic playthings.

But as a writer of fiction, my life remains fervently in need of these dreams, these visions, these specters out the corner of my eye. And so, even as I dedicate myself to waging war against Internet brain and the inherent distractions that pull me away from my visual thinking, I also become more intent than ever on once again consciously accessing this amazing realm of creativity.

When I mentioned this a few weeks ago in my post on combating Internet brain, one of you asked that I further develop the idea of reclaiming visual thinking. This post largely chronicles my own practices for working with my visual thinking.

I recognize these thoughts may not be useful to some of you, since studies approximate that only around 60-65% of people think in pictures (although I wouldn’t be surprised to learn this percentage rises among storytellers). If you are not someone who can, or normally does, think in pictures, I’d love to hear your take on all this. Does the idea of visual thinking resonate at all? Have you ever attempted any of the following exercises, and if so did you have to modify them? Particularly, I’d love to know how you interact with stories if you don’t see them.

For now, here are my thoughts on how those of us who use visual thinking can hone our mind pictures, so we may reap their creative benefits, both personally and creatively.

11 Exercises to Practice Visual Thinking in Your Writing Life

Our truest life is when we are in dreams awake.–Henry David Thoreau

No doubt, Thoreau’s idea was that we manifest our dreams for how we’d like our lives to look in our outer worlds. But as writers, I think most of us can see the other side of this blessing as well—when the beautiful and exciting visions of our unconscious minds join us in our mundane lives. Sometimes these visions grow so rich and vibrant we are able to stitch them together into the full and meaningful tapestry of a complete story. And what are stories if not dreams we share with one another?

To help us all become better dream-sharers, here are eleven exercises I use to consciously access my visual thinking and creativity.

1. Dreamzoning

From Where You Dream by Robert Olen Butler

I harp on this one all the time, mostly because it has been my creative sweet spot for the last ten years. For those who don’t know, “dreamzoning” is Robert Olen Butler’s term for a practice not too far afield from Carl Jung’s “active imagination.” It is an intentional period (anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours) of focused daydreaming, in which you zone out and zone in on your story.

Although you may actively create and guide a narrative during this time, you can also use it to more directly tap your unconscious by simply allowing images of your stories (or whatever) to surface and following “whatever moves.” Much like any meditation practice, you may find it helpful to create a distraction-free environment with background music and a focal point like a candle.

2. Taking Story Walks

Turn your daydreaming into a “walking meditation.” I used to do this naturally as a kid—take my stories with me. Nowadays, it requires more concerted effort for me to remember to let my own inner visuals rise up and join me in the world.