K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 33

November 11, 2019

How to Write Your Memoir Like a Novel

A few years ago, I went to a workshop in New York City for writers. There I was surrounded by a group of novelists. As someone who loves to write fiction, I was interested, but at the time, I wasn’t working on a novel. I was working on a memoir, a book about a series of adventures I had in Paris called Crowdsourcing Paris that was published just a few weeks ago.

“Is this a waste of time?” I thought. “Can the techniques they’re teaching at this workshop actually help me write a better memoir?”

And for you, if you’re working on a book about your life, what can you learn from novelists? Are there any fiction techniques that you can apply to your memoir writing?

In this post, I want to share what I learned both from the workshop and since then about writing a memoir. If you’re writing memoir, I think these techniques will change your writing process and result in a much better book.

And if you’re working on a novel right now, pay attention too, because these same techniques will help you with your writing.

Can Memoir Writers Learn from Novelists?

As I was sitting in that workshop in NYC, it began to dawn on me, slowly and then all at once, how similar memoirs and novels are.

Before we talk about what memoirists can learn from novelists, let’s talk about what makes a good memoir in the first place.

Here are some things people love about memoir:

Tells an entertaining, engaging story

Life lessons you can apply to your own life

Getting a different perspective on life and the world

Funny and/or emotionally moving

When you look at those four criteria readers want in a memoir, you can see that three of them are exactly what many readers want in a novel. Which is to say this:

Novelists and memoir writers are trying to accomplish many of the same goals! The only difference is that memoir writers are writing their personal life stories.

I’ve been told again and again that my memoir, Crowdsourcing Paris, is a fast read. One person even read it in two days. A major reason that people have so much fun reading my book is because I wrote it like a novel, using the techniques we’re going to talk about below.

I’ve been told again and again that my memoir, Crowdsourcing Paris, is a fast read. One person even read it in two days. A major reason that people have so much fun reading my book is because I wrote it like a novel, using the techniques we’re going to talk about below.

And if you’re writing a memoir, so should you!

How to Write Your Memoir Like a Novel: 4 Fiction Techniques for Memoir Writers

What can memoir writers learn from novelists? There are five literary techniques that I drew from my novel writing experience to write my memoir:

1. Limited Scope

When most people approach writing a memoir, they just start writing. They start with the day they were born, and if they can keep up with the writing process, they go all the way to the present moment.

But think of your favorite novels. There are certainly stories that span a character’s entire life, but what is much more common is the stories that have a limited scope, encompassing a specific situation. For example:

A quest

An adventure

A crime that must be solved

A new romantic relationship (or the unraveling of one)

Betrayal and revenge

A coming of age experience

Great stories, in other words, are rarely about an entire life. Instead, they’re usually about one intense period in a character’s life.

The same is true for your memoir. Instead of trying to write a historical autobiography, which is not the purpose of memoir, choose one very intense period of your life and write about that.

The best way I’ve found to choose that period is to write a premise. A premise is a single-sentence summary of your story. For memoir writers, your premise should contain three things:

A character (i.e. you)

A situation (the intense life event you experienced)

A lesson

And you should combine those things into just one sentence.

Why one sentence? Because you can’t summarize your entire life in one sentence, but you can write about one specific situation.

Then, anything that doesn’t fit into your premise should be cut and put into another book.

Don’t try to write an autobiography. Instead, choose a limited scope for your memoir and write the best story you can.

2. Story Structure

Novelists think a lot about plot and structure. We have jargon we use, like three acts, turning points, climaxes, inciting incidents, falling action, and resolutions. We spend time outlining, mapping our story, and even creating spreadsheets to track the rise and fall between each scene.

Memoir writers, though? They don’t think much about plot and structure. And it’s a shame, because this is the best fiction technique you can apply to your memoir.

When I wrote Crowdsourcing Paris, I wrote the entire first draft just based on how I remembered things happened. But then I went back and read my book and thought, “There’s something missing here.” I didn’t know what it was, but I knew it wasn’t accomplishing the things I wanted it to. There were a lot of good sections and a few bad sections, but it didn’t feel like a book yet.

When I wrote the second draft, I intentionally spent time outlining the plot and structure that I wanted to bring to the story. I rearranged the timing of events slightly to build tension and drama. I cut backstory and added flashbacks to increase the pace of the story and get the reader into the action faster. I rewrote scenes to heighten the suspense.

By the time I finished the second draft, it was a great story, not just a bunch of great scenes.

We don’t have time to get into everything you should know about plot and structure, but here are a few resources you can use to learn more about this for your memoir.

First is K.M. Weiland’s own series on the Secrets of Story Structure, which is thorough and so helpful.

For a quick guide, Matt Heron has a great Writer’s Cheat Sheet to Plot and Structure here.

I also love Story Grid’s approach. You can find an article on how to use Story Grid for your memoir here.

3. Show Decisions

Most writers are familiar with the advice, “Show, Don’t Tell.” The idea is that you should always show the important moments in a story, writing a full scene with description, dialogue, action, and narrative, not just tell the reader about it in summary.

But the question is what do you show? What’s the most important thing to show?

When trying to “show,” most memoir writers write about the bad things that happened to them, and that’s smart because you can’t show change and character arc without diving into the hard parts of your story.

But often, memoir writers leave out the most important part of those experiences: the decision.

Good stories are about characters who make decisions. That’s why every scene in your memoir should be centered on a decision, a choice that you made, usually between two bad things or two good things.

I get that this is hard. When you’re writing a story about your own life, it can be hard to find the decisions you made in a situation. After all, much of the time, the events in our lives are outside of our control, especially the negative experiences.

But these decisions are actually what drive all the action in your story, and if you are the main character in your memoir, you have to be the one driving the action, you have to be the protagonist, and you have to show your decisions.

This was one of the hardest parts of writing my memoir. But showing my decisions, more than any other technique I learned from fiction writers, was the thing that most impacted my memoir.

4. Kill Your Darlings

“Kill your darlings,” said Stephn King. “Kill your darlings, even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.”

I wrote over 100,000 words in my memoir. However, by the time the book was finally published it was only 52,000 words long.

That means I had to cut almost 50 percent of the book. Some of those scenes and paragraphs and sentences were amazing. I had labored over many of them for hours, even days.

And yet, they didn’t fit the story I was trying to tell.

You have to kill your darlings. You have to cut the sections of your book that don’t fit.

Doesn’t fit the premise? Cut the scene.

Outside of the limited scope of the story? Cut the scene.

No decision? Cut the scene.

Doesn’t fit the story structure? Cut the scene or rewrite it until it does.

This is one of the hardest parts of writing a memoir, but it can also be some of the most fun. I had several experiences where I cut a chapter and all of a sudden the flow of the story was so much better.

I use Scrivener to write my memoir, so when I cut things, I always put them into a folder of saved sections. Someday, I may be able to incorporate those sections into another book. Some, I even put back into the story after realizing the book really did need that section.

The point is you have to be willing to be ruthless. If you don’t, your story can easily get bogged down by the weight of a lot of good sections that don’t serve the purpose of your book as a whole.

This Is How to Write a Great Memoir

If you want to write a memoir that’s fun to read, not just something that passes on your life experience and legacy, learn the fiction techniques novelists know.

There are certainly great reasons to write an autobiography sharing your entire life experience, but unless you’re famous or a historical figure, don’t expect anyone beyond your family to read it.

But if you want to write a memoir that’s actually fun to read, then use the fiction techniques above to make your memoir good.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever thought about writing a book about your life? Which of these techniques do you think would be most helpful for your story? Tell us in the comments!

The post How to Write Your Memoir Like a Novel appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 4, 2019

23 Tips for a Zero Waste Home Office

A little over a year ago, I decided to create a more sustainable, zero waste lifestyle. As a writer, time at the desk is a huge part of my life, so figuring out how to create a zero waste home office was a top priority from the beginning—and, honestly, one of the easiest parts of my life to hack.

A little over a year ago, I decided to create a more sustainable, zero waste lifestyle. As a writer, time at the desk is a huge part of my life, so figuring out how to create a zero waste home office was a top priority from the beginning—and, honestly, one of the easiest parts of my life to hack.

Although for quite some time I have been slowly sliding into a more responsible awareness, I didn’t fully understand the importance of my shopping choices and waste contributions until I started trying to find more routine household products that could be reused instead of tossed (e.g., handkerchiefs instead of tissues). About a year ago, I made a personal commitment to produce as little trash as possible—especially plastic trash (which basically sticks around forever and forever). Since then, I’ve eliminated as much of my trash as possible (via some of the tips I’ll talk about in a minute) and tried to be as responsible as possible in disposing of unavoidable waste (via composting and recycling).

When I made these commitments, I expected to feel good about myself, maybe live a healthier life, and hopefully “make the world a better place” (as my sister is always telling her kids). What I didn’t expect was that I would love the zero waste lifestyle. Seriously, I am a total addict.

I love the simplicity and the beauty that have come to the forefront of my life as I’ve become more mindful of my lifestyle choices. I love that I’ve eliminated ugly plastic “essentials” (like shampoo bottles and dish brushes) from my life. I love that I have an easy metric that helps me decide not to buy junk I don’t need. It’s weird, but I even love washing out bottles and cans before putting them in the recycling bins.

There are still challenges I’m working on. I’m not zero waste (if there really is such a thing). Particularly, I’m still trying to figure out how to buy food with (way) less packaging. Although I recycle most of my “non-recyclable” kitchen waste through TerraCycle, I realize it’s still not as sustainable as avoiding the packaging in the first place. Still, I’m pleased that so far I’ve reduced my actual send-it-to-the-landfill trash to, on average, one tiny bag a month.

Which is all to say: there are a lot of heavy-duty reasons why it’s important for all of us to be more mindful of the waste we’re creating, but for me the top reason is joy. I love this lifestyle. For me, it’s a move toward health. Making conscious waste choices is no different from making conscious eating choices. They both require discipline and some self-growth. But they’re both deeply rewarding.

Anyway, enough preaching. For those interested, I promised last winter that I’d share a post about my top suggestions for creating a zero waste home office. For me, the office was one of the easiest transitions to make, since I was already creating very little waste in that area of my life. Below are my tips for making sustainable choices in your writing life.

Buy (or Bum) Tools That Are Eco-Friendly Choices

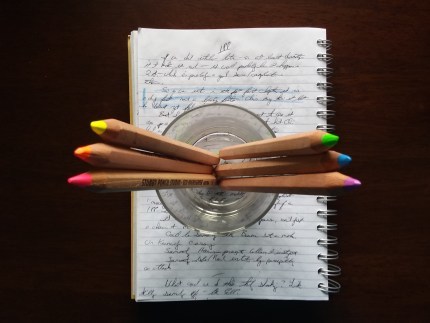

1. Highlighter Pencils

I outline longhand in a notebook and use a color-coded highlighting system to organize my notes. But highlighters, of course, are plastic (and toxic). Fortunately, a super-easy switch to make is to highlighter pencils. These are basically just giant colored pencils, but they work just as well as the markers.

2. Aluminum Pencil Sharpener

I bummed mine off my mom (who might have gotten it from my granddad). Instead of buying a big plastic sharpener, I keep this one handy for topping off my pencils. (I also have a wooden sharpener that came with my highlighter pencils, which was great since they’re too fat for the standard-sized sharpener.)

3. Stainless Steel Scissors

Ditch the plastic handles for an all-steel version. I haven’t actually made this switch myself because somehow I already own a bazillion scissors—which in itself is a good reminder to use what you have, even if it is plastic, instead of buying something new just because it’s “zero waste.”

4. Paper Tape

Most tape is plastic. Whether you’re mailing review copies of your books or just taping the flap on an envelope that just won’t stick, opt for a paper alternative for packing or wrapping. I haven’t made this switch yet either, but will as soon as I use up my current supplies.

5. Compostable Phone Case

When I finally got a smart phone last year (yes, I was the last person on the planet to get one), I bought a wooden case off Etsy. I thought it was a better alternative, but half of it ended up being plastic. When next I need a case (which will be a bummer, because I love this one), I’ll be looking into compostable options made from eco-friendly materials.

6. E-Books

Although digital downloads aren’t without their own footprint, it’s clear that e-books don’t require the same output of physical resources as do paperbacks and hardcovers. I’m not a solid e-book user (I also use Paperback Swap and, of course, the library), but when I’m buying new, I generally opt for the digital version.

7. Wooden Coasters

Gotta have my coffee (or kombucha) handy when writing! There are lots of good options available for coasters (including odds and ends found around the house, if you’re so inclined). If you’re buying new, opt for a natural material such as wood, instead of plastic.

8. Beeswax Candles

I use a big three-wick candle for “dreamzoning” when it’s too cold or windy for an outside fire, and I like to have a small candle in the corner of my vision when writing in the evenings (or reading in the mornings). My research tells me beeswax candles far and away the healthiest choice—for both myself and the planet. In regards to health, soy wax is a decent runner-up (although its footprint is often problematic, depending on how it was sourced). If the candle doesn’t tell you what it’s made from, then it’s probably made from paraffin (a petroleum byproduct) or other chemicals. (Also, look for cotton wicks, as some others contain lead.)

9. Wooden/Natural Fiber Decor

In decorating your office, opt for furniture and decor made from natural materials, especially if you’re buying new. Look for hardwood furniture (not MDF or laminate—which are constructed with chemicals such as formaldehyde). If you need a rug, avoid polypropylene and nylon (read: plastic) choices and opt instead for wool, cotton, or jute. For decor, shop used (such as antique typewriters!) or find non-plastic alternatives (books!).

Buy Recycled

10. Recycled Pencils

Pencils in general aren’t so bad, since they’re made primarily from wood, but if you need to stock up, why not choose pencils made from recycled newspaper? Recycling your own trash is great, but the process only works if we’re also purchasing recycled materials.

11. Recycled Notebooks

You could, of course, opt out of using notebooks altogether in favor of no-paper options like your computer and phone. But, c’mon, we writers love our notebooks. Instead of kicking the habit (although it’s a good idea to only buy notebooks when you actually need them), make a conscious choice to find recycled alternatives. Avoid plastic covers—which include faux leather versions. I got these big fat beauties for outlining and this slim version for my monthly budgeting. And I’m currently considering this lovely for collecting sayings.

12. Recycled Address Book

Technically, you could use one of the above notebooks if you need it for something like addresses. But you could also opt for a sweet little recycled version made specifically for the purpose.

Choose Tools You Can Reuse/Refill

13. Fountain Pen

When writing those longhand outlines, I’ve always used an ergonomic pen. I love it, but it goes through ink cartridges like nobody’s business. When I mentioned in my New Year’s goals post that I was thinking about trying a refillable fountain pen, awesome reader Glenn Cox sent me a pen and a bottle of ink (woot!). I haven’t completely made the transition but am committed to getting there.

14. Staple-less Stapler

Staples aren’t plastic, but they do interfere with recycling (so be sure to remove them before putting paper in the bin). Plus, if you can staple your papers without a staple, why not? I got my staple-less stapler used off eBay (since all the newer options are made of plastic). Never have to buy or reload staples again…

Shop Your Home (and Your Trash)

15. Use Junk Mail for Scratch Paper

Although I try to reduce unnecessary mail as much as possible, I still get the inevitable credit card offers, etc. After cutting out and throwing away the plastic address windows, I recycle what paper I can’t use and save the smaller scraps for scratch paper. Sometimes I’ll even cut up the bigger pieces to create little scene cards for outlines.

16. Save Rubber Bands

Occasionally, the mail carrier will strap all my mail together with a rubber band. I always save them against that rainy day when I really need a rubber band.

17. Use Old Devices

I still have a 2nd Gen iPad, the first one I ever bought. The hardware is too old to play nice with the latest iOS updates, and I’ve been thinking about replacing it for years. But the truth is I only use it to run the Scrivener app when outlining away from my computer. And that still runs fine. So why replace it?

E-waste is a huge problem. Resist all those commercials telling you to buy a new phone/tablet/computer just because there is a new one. Instead, use every last drop of juice in the ones you have. (And then dispose of them responsibly.)

Cultivate Good Habits

18. Buy Used

I have several rules of thumb I use when deciding what and how to purchase.

The first rule is to wait. I don’t have an official time limit, but unless it’s an item I really need, I try not to buy things the minute I put them on my list. I think about it for a while, until I’m sure I really do need it and that I’m making the best choice for what to buy and how to buy it.

The second rule is to avoid plastic—both in the product itself and (often, more sneakily) in the packaging. As mentioned above, I look for non-plastic alternatives. As one example, when I needed a laptop stand, I bought a wooden alternative from Etsy.

The third rule is, when I can’t find a non-plastic alternative (and sometimes even then) I, buy used. I shop garage sales in the summer, buy clothes secondhand (mostly from ThredUp), and look to eBay before Amazon.

19. Request No-Plastic Shipping

Although I try to buy locally whenever possible, the fact that I’m super-picky about what I buy and how it’s packaged means I often end up looking online. There are several problems with purchasing from the Internet. One is the carbon footprint created by the package’s need to be transported to my door.

The other problem is that one of my biggest remaining sources of trash comes from plastic mailers and packaging. Whenever possible, I shop from responsible sources that don’t use plastic packaging (such as Package Free Shop, Wild Minimalist, Refill Revolution, Fat and the Moon, The Good Fill, Tiny Yellow Bungalow, and Life Without Plastic). When this isn’t possible (such as when I’m shopping on eBay or Etsy), I always try to remember to add a note to the seller, requesting they ship without plastic if at all possible. More often than not, sellers are happy to oblige.

20. Use Power Strips You Can Turn Off When Not in Use

“Phantom energy” refers to the energy some devices pull just from being plugged in. Anything that runs on a remote, features a light, or uses a big “wall wart” plug may be pulling power even when not in use. A good way to combat this (for your pocketbook as much as anything) is to either unplug unused devices (think: your toaster) or plug into a power strip you can turn off (this is great for big devices such as your computer and TV). My TV’s strip is on only when I’m watching something in the evenings, and my computer’s strip is on only during the work day. (While you’re at it, get strips that will protect your devices against power surges.)

21. Borrow Equipment When Possible

I don’t own a printer or a scanner. In part this is because I ruddy hate the things (and they hate me back). But it’s also because I use them only a few times a year. On the rare occasion when I need to print a contract or something that’s just a page or two, I use a relative’s. If I have a big printing job, I’ll take it to Staples.

22. Don’t Print Unless Absolutely Necessary

The big postscript to the above tip is to simply avoid printing whenever possible. As noted, I hate printing anyway, so this isn’t a big sacrifice. About once per book, I find I do need to see my words on the page in order to properly edit them, but mostly I edit on the computer or on my Kindle.

When I do need to print, I use an “eco” font like Spranq Eco Sans, which uses less ink than normal fonts. I also downsize the font as much as practical to reduce both ink and paper usage.

23. Play Downloaded Music Instead of Streaming

Everything that happens on our devices and/or the Internet often seems “zero waste.” But it’s important to remember that even when we play something off the cloud, that data is still being stored on a physical hard drive powered by electricity. In short: everything we do on the computer requires physical resources of some kind.

It’s so easy to play music on Pandora, YouTube, or Spotify instead of off the hard drive. But it requires less resources all around to play music you downloaded once rather than music (or video) you’re constantly streaming. I try to purchase music I like (either a digital download or a used CD), put them on my devices, and play off the hard drive instead of streaming. This isn’t a hard and fast rule for me, by any means, but it’s something I try to be aware of.

***

This list is, of course, far from complete. It’s just an inventory of the things I do or try to be aware of in making the lifestyle choices that are best for me and everyone else on the planet. I hope these ideas will inspire you to create or refine your home office into a waste-free paradise!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you tried a zero waste home office? Do you have any tips to add? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/zero-waste-home-office.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post 23 Tips for a Zero Waste Home Office appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 28, 2019

How to Know Which Parts of Your Story Readers Will Like Best (It Isn’t Always What You Think)

You want readers to like your story. You want to give them something to love on every single page. But it’s so much easier said than done. How can you know—really know—which parts of your story readers will like and which will have them yawning and skipping ahead?

You want readers to like your story. You want to give them something to love on every single page. But it’s so much easier said than done. How can you know—really know—which parts of your story readers will like and which will have them yawning and skipping ahead?

So many stories, in all mediums, hit the market with blazing optimism from their creators. Audiences are going to love this! We’ve checked all the boxes!! We’re so excited to share something we’re so sure is going to make you so happy!!!

The optimism isn’t always well-founded. Just watch behind-the-scenes interviews on would-be blockbusters, which were intended as the first in a series only to fall flat at the box office and never be heard from again. Beforehand, directors, producers, and actors might have gushed about how certain they were audiences would geek out over their choices for the film—only to have their enthusiasm met with a big green splat on Rotten Tomatoes. Clearly, they misjudged those parts of the story they thought audiences would particularly like.

Novels don’t usually dive-bomb so obviously or spectacularly, but I can certainly think of a few sequels that failed to live up to their glorious predecessors. Mostly, this is because the authors made clunker decisions that, pretty obviously, were intended to be just the opposite.

So what are you to do? Maybe throw a bunch of stuff at the wall and hope enough sticks to keep readers happy? Or maybe just write the blithering book to the best of your ability and hope it all works out for the best?

Naturally, the latter option is the way to go. But it doesn’t have to be a blind path into the unknown. There are ways to figure out which parts of a story are mostly likely to entertain readers and which are not. And the key words here are “most likely,” because if there’s one thing you can be sure of in this business, it’s that art is subjective.

6 Ways to Figure Out Which Parts of Your Story Readers Will Like Best

Subconsciously, readers are going to judge every single one of your scenes and file each in one of three categories:

Entertaining

Tolerable

Boring

Very few stories manage the brilliance necessary to land every single scene in the Entertaining Category. The good news is that you can still create a story readers like even with a handful of Tolerable scenes and maybe even a (very) small percentage of Boring scenes.

The bad news is that the higher your Tolerable count rises, the more the book as a whole will lean toward Boring. Even if readers finish it, they’re not likely to remember it. And, of course, if the count on the Boring scenes crosses a certain invisible threshold (which is a little different for every reader or viewer), the story is bye-bye.

You can perform a rather sobering exercise by listing all your scenes and ruthlessly judging which falls into which category. Every scene that ends up in the Tolerable or Boring Categories needs some help.

And how do you help them? Here are six ways to judge whether a scene contains the stuff readers love—or the stuff they actually don’t.

1. The Best Part of Your Story Is… Your Characters

So I admit this post is kinda inspired by Maleficent: Mistress of Evil, which left me pretty meh. It’s not totally a fair example, since the film is exactly what it’s intended to be. But for my money it could have been a lot better. It just needed more of its characters—especially its most interesting characters.

Elle was fine, Pfeiffer showed admirable dental work in chewing through the scenery. But is this Maleficent’s show or not? Like so many stories these days, the protagonist appeared in a scant percentage of the actual running time. (I find it a little ironic that in a film supposed to be about the original villain of the Sleeping Beauty story, most of the story and screentime went to the new villain.) The only scenes in the movie I would chuck squarely into the Entertaining bucket were the few moments early on when Maleficent’s sidekick coached her in smiling and then later when Maleficent grudgingly tried to charm the future in-laws. After that… not too much interesting character work going on.

The movie falls into one of the most common pitfalls I see in stories that try really hard to be Entertaining without quite making it: it splits up it’s most interesting characters. For roughly 60% of the story, Maleficent doesn’t interact with any characters except the Dark Fey—whom she mostly just observes. When [SPOILER] the guy she did talk to dies, however crucially, the relationship feels barely developed, almost meaningless, especially in comparison to the preexisting characters back home with whom she could have interacted with so much more entertainment value. [END SPOILER]

This is the single most important trick for genuinely entertaining readers.

1. You have to write great characters—people with whom the audience will emotionally invest and who will then act with genuine spontaneity and organic energy.

2. You’ve got to put all your best characters in the same room. One awesome character monologuing to a bunch of redshirts (or, worse, musing in solitude) is never going to deliver the same amount of goods as two (or more!) awesome characters impacting each other’s plot progressions.

3. Don’t skimp on the character interaction just to squeeze in other stuff. Other stuff is important. But it is not—it is never—as important as character development.

2. The Best Part of Your Story Isn’t (Necessarily) Genre Beats

Usually, the stories that try really hard to please readers only to fail are those that place too much faith in the importance of genre beats.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Genre beats are important and can be wildly entertaining. Romance readers want the kiss. Superhero fans want the Big Boss battle in the end. Paying nothing but lip service to important genre tropes can make it seem as if you’re phoning in the entire story. But overdoing them, especially at the expense of developing other aspects of the story (*cough*characters*cough*), can create an ironically flat experience even for die-hard fans of the genre.

To my eye, there seems to be a lot of confusion about exactly what to do with genre beats these days. Writers know readers have seen certain beats so often, they’ve become clichéd. So they go meta on the clichés by pointing them out (but, don’t miss, still including them). A super-obvious example is calling out the villain monologue. The subversion of the trope felt fresh and funny when Syndrome did it back in 2004, but not so much anymore.

Truly, the only way to hit genre beats in a deeply satisfying and entertaining way is to go old-fashioned—do it how it was done in the very beginning, back before a particular beat ever became something so obvious as a beat, much less a trope. And what is this old-fashioned way? Write it organically into your story. Make it a crucial and emotionally-important part of the plot-character-theme trifecta. If you can’t be fresh (and, please, be fresh), then at least be so honest with your story that it hurts.

3. The Best Part of Your Story Is That Sweet Spot Between What Readers Have Seen Before and What They Haven’t

What are genre beats? For that matter, what’s plot structure and character arc? Although many writers initially see these beats as something to be arbitrarily added to a story (the “secret sauce,” if you will), these beats are instead an emergent of time-tested archetypal patterns. “Genre beats” are a thing not because readers “like” them, but because readers resonate with them.

Understanding story theory and studying the archetypal patterns in narrative will give you a foundation for writing a type of story that will reliably grab people’s hearts. But as any reader or viewer will immediately tell you, this does not mean they want to see the same thing over and over.

Genre fatigue happens when the same storyform is being told too often in the same way. In a romance, we want to see the leads end up together. But that doesn’t mean we want the 100th rendition of Marry Christmas: A Holiday Happily Ever After. People fall in love every day. It’s the same archetypal story. But to those involved in it, each story is brand new and deeply important—and deserves to be told with honesty and freshness. Hit your genre beats, but do it in a way that is integral to the story you’re trying to tell (a story no one’s ever told before, right?) and with the truth of your own unique experience.

4. The Best Part of Your Story Is (and Isn’t) What You Like Best

Until your story is out there for readers to irrevocably judge (aka, until it’s too late), the only person who can give you a line on whether your story has enough of the “good stuff” is… you.

You know you’re on the right track with any scene you emotionally or viscerally respond to. You know you’re on the right track if you’re writing the kind of scene you would get on your knees and beg your favorite author or director to make for you. (And, note, this doesn’t just mean ripping off the scenes you went nuts over in somebody else’s story.) What’s your favorite scene in your story so far? That scene might well be the most entertaining scene in your whole book (and if it’s not, it should be).

Be careful, however, to distinguish between the scenes you love because they hit you in the gut and the scenes you love just because you think they’re really, really, clever. If you’re realistically acknowledging that you skillfully executed a scene, that’s one thing. But if you’re geeking out because you’re just sure readers will bow to your genius, you might want to double-check your objectivity.

5. The Best Part of Your Story Isn’t the Part That Doesn’t Work

Spoiler alert: if the writing’s bad in any given scene, that’s probably not going to be the scene your readers fall in love with.

In short, as G.R.R. Martin has told us (in a way that seems kinda prescient now):

Ideas are cheap. I have more ideas now than I could ever write up. To my mind, it’s the execution that is all-important.

Funny characters, shiny plot beats, and original ideas won’t save a story that doesn’t come together holistically. Here’s a very short, very incomplete list of the mistakes that can blind readers to even your most entertaining scenes:

Plot holes (“It was fun, but… it made. no. sense.”)

Authorial condescension (“Yes, yes, the overdone symbolism and on-the-nose dialogue made the thematic message so much more powerful.”)

Authorial self-indulgence (“Ten chapters of worldbuilding. There must be a test at the end of the book. There’s a test, isn’t there?”)

Wasted time (“We get it. She’s training. Again.”)

Boring info (“Ah, my old friend—backstory info dump. What would we ever do without you?”)

6. The Best Part of Your Story Is the Foreshadowing

This one almost is a secret sauce. This is because foreshadowing is one of the most powerful tools in a writer’s bag for evoking emotion.

Yep, you heard right.

Foreshadowing, done right, can knock your book out of the park. And I guarantee you’ve got some missed opportunities waiting for you in your story right now. I say this because I see these missed opportunities all the time in published stories.

The key is to remember there are two halves to proper foreshadowing: the setup and the payoff.

It goes without saying that if you pique reader curiosity by setting up a big juicy clue early on, then you must pay that off later in the story. Otherwise, it’s one of those plot holes we took issue with in the previous section.

Most writers know this and are careful to payoff early clues. What is easier to overlook is the opportunity presented by any big event in your story’s second half—especially the Climax. And I do mean anything. Even the smallest reveal or plot turn deep in the story can be transformed into an emotionally resonant moment by planting a little foreshadowing early on (don’t believe me? go watch Endgame again).

Examine every scene in the second half of your story and make a list of any and all revelations and plot turns. Can you create foreshadowing opportunities for at least some of these early on? Callbacks such as these create the effect of depth, meaning, and thematic resonance (plus, it makes it look like you really know what you’re doing). Skillful foreshadowing has the ability to take a Tolerable scene (even a Boring one, in a few cases) and transform it into an Entertaining and even unforgettable moment in your story.

***

Ultimately, the parts of your story readers will like best are probably the parts that made you want to write the story in the first place. Look for those scenes, figure out why they are so personally powerful to you, then leverage them for all they’re worth. Readers won’t be able to look away, and they’ll close your book happily wishing you’d given them more of everything rather than grumpily wishing you’d just given them more of the good stuff.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think are the parts of your story readers will like best? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/best-parts-of-your-story.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Know Which Parts of Your Story Readers Will Like Best (It Isn’t Always What You Think) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 21, 2019

A Writer’s Guide to Understanding People

“Write three-dimensional characters.” “Bring your characters to life.” “Create realistic human experiences.” These ditties of writing advice are so common they’re almost clichés. But how can you fulfill these dictums to write “real characters” without first mastering the even more foundational principle of understanding people?

“Write three-dimensional characters.” “Bring your characters to life.” “Create realistic human experiences.” These ditties of writing advice are so common they’re almost clichés. But how can you fulfill these dictums to write “real characters” without first mastering the even more foundational principle of understanding people?

Recently, I received an email from a reader, which raised a question so pertinent, so obvious, and yet so overlooked that I felt it worthwhile to answer it in a blog post. He wrote:

After searching though your archives, I have been unable to find an article on the subject of people. Chief among the advice given to fiction writers is to have well-developed characters, and often included is the suggestion that one should listen to people, learn how they speak, act, and react.

I do not understand people. Why they react the way they do, why they say what they say—these are not things that I have been able to measure or bottle. Oh, I have listened to plenty of strangers speak in quiet coffee shops, true enough. Psychology offers interesting material to sift through, but I have found that it is only helpful to a point.

My question then, after the less than concise outpouring of words above, is this:

How did you learn about people and their behavior thoroughly enough to craft believable characters? Is there advice you would give to any of us struggling in this area?

The theories and techniques of writing fiction offer many refined ideas about how to convey realistic and charismatic characters on the page. All of these approaches necessarily reflect certain understandings of how people “work.” Because all stories, even the most fantastic, seek to provide a simulacrum of reality, every technique is at least nominally founded on the idea of, first, understanding people and, second, conveying that understanding with accuracy.

But as the email points out, it’s easy (maybe even inevitable) for us to get the cart confused with the horse. In part, this is because as humans ourselves, most of us take for granted that we understand people far more than we actually do. In even larger part, I think it is because most of us are using our writing, whether consciously or unconsciously, not so much as a way to reveal what we understand about people, but rather as a way to figure out ourselves, our fellows, and our existence as a whole.

Today, let’s take a more conscious approach to investigating how we can enhance our ability to understand people on our way to writing better and more realistic characters.

Writer, Know Thyself

That person in the mirror is your best shot at understanding a human being. She’s seductively mysterious, deeply complex, scarily dark, miraculously replete, and ridiculously dimensional. Start there. Actually, I think you’ll find there’s so much there, you may never need to stop.

There are many ways to get to know yourself better, both as a human and as an individual. Exploring psychology and personality-typing theories is a great way to start peeling back the layers on your onion (I recommend Jung’s cognitive-function model and the Enneagram for starters). Largely, these will be exercises in growing your own awareness and honesty.

Get to Know Yourself Physically, Mentally, Emotionally, and Spiritually

Learn to get in touch with all four corners of yourself—physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual. Most of us tend to neglect one or more of these areas. Not only does this cause the health of the other areas to suffer, but it blocks us from a fuller understanding of even those areas we believe we already understand.

For me, learning how to listen to my emotions and my body (and realizing I previously couldn’t even hear what they were saying) has been astonishing. I thought I knew myself pretty well; turns out there are whole vast areas into which I’ve never yet gone spelunking.

I talked a few posts back about the idea of repressed aspects of the self weighing us down and eating up our creative energy through inner resistance. That “shadow” part of ourselves holds (often initially painful) aspects of the human experience that we’ve relegated to the darkness of an almost willful ignorance. Shining light into our own dark places offers a wealth of insights into the human experience as a whole.

Figure Out What Your Own Writing Tells You About Yourself

More than that, don’t forget that as a writer, you already have an immensity of illuminating research at your fingertips. Look closely at everything you’ve ever written. Often, the fiction is even more revealing than the shadow-blind soul-searching found in journal entries or personal essays. In revisiting some of my own work from the last ten years, I’ve been fascinated to realize the “dishonesty” of some of my journal entries, especially in comparison with what has turned out to be the symbolic accuracy, and even prescience, of many elements in my fiction.

Even in your early clumsy attempts to sketch rounded characters and events, you were telling yourself truths about yourself—and thus about people in general. Every character you write (even those based on existing or historical people) inevitably become avatars of yourself. They are avatars of the aspects you claim, the aspects you reject, and the aspects of which you are not even yet consciously aware. Take another look at your own stuff, from an older vantage-point, and see if you can figure out what you knew all along but maybe didn’t know that you knew.

The Art of Observing Others

Although seeking to understand yourself will provide your deepest and richest insights into the human experience, the inherent subjectivity of your own experiences won’t give you a complete view of your subject.

Study Psychology and Personality

This sounds (and was) stupid, but it wasn’t until my mid-teens that it hit me like a thunderbolt that not everybody was like me. Prior to that, I literally thought everybody was wired pretty much the way I was… which meant I lived in a perpetual state of frustration because if they were all like me, then why didn’t they do things my way?!

Studying psychology and personality typology has led me not just to a better understanding of myself, but also a better understanding of the panoply of differences found in others. I appreciate and advocate systematized approaches because I find them so useful as a starting point in breaking down the vastness (and yet surprising simplicity) of the human experience.

Observe Human Interactions Through 3 Different Lenses

People watching—the writer’s stock-in-trade hobby—remains one of the single best ways to deepen your understanding of characterization. Although there’s much to be gleaned from casually watching random interactions in the mall or airport, the true opportunities come from your actual interactions.

One particularly helpful rule of thumb to keep in mind in observing the interplay between yourself and others is the Chinese proverb:

There are three truths. My truth, your truth, and the truth.

There are always going to be three perspectives: two subjective viewpoints and one objective viewpoint.

After an exchange when another person (especially if it was heated), take a moment to step back and observe. Note your experience and opinions about what just happened. Then, try to honestly assess how you think the other person experienced and judged the same moment. Finally, take a further step back and try to see things objectively. Don’t make value judgments (e.g., “they were wrong and I was right”); just note what actually happened, what each of you did and said—the context, not the subtext.

In the cracks between all three perspectives, there are usually insightful nuggets to be found if you’re honest enough to recognize them (which, frankly, can be grueling sometimes).

We will only ever understand others—and therefore “people” as a collective—via our own viewpoints. But the more we can practice noticing how others see things and how both our and their viewpoints stack up against the objective facts, the better we can become at recreating realism in our stories. (Plus, getting in the habit of separating objective happenings from their subjective slants will give you leg up on understanding how to show rather than tell.)

The Key to Understanding People Is to Do Your Homework—Literally

As children of the 20th and 21st Centuries, we have access to an unprecedented view of the human experience. Never mind the easy accessibly of the Internet, we are blessed (if often overwhelmed) by just the sheer accumulation of questioning, discovering, understanding, and recording left to us by our ancestors.

While understanding yourself and understanding those around you may be the deepest trove for studying characters, there is a still broader treasure chest to draw from. Some of it can look a little like the drudgery of homework, but most of it is so much fun, it requires only a little extra oomph of discipline for us to take full advantage of our opportunities.

Here are four assignments to get you started (although I’ll bet you’re already elbow-deep in almost all of them):

1. Pursue Literature

You’ve heard it before, but it’s a drum that’s always worth banging:

If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.–Stephen King

Commit yourself to reading voraciously. Always have a bookmark in a book and that book within easy reach. More than that, read widely.

Read those lists of “100 books to read before you die.”

Read the classics.

Read all the Pulitzer and Nobel winners.

Read any book so famous you recognize its title and/or author when browsing.

Fifteen years ago, I committed myself to reading all the classics (so far, I’ve made it through most of the authors up to “R”). It’s been a lot of work (a lot of work), but it has also been one of the most valuable and broadening exercises I’ve ever undertaken. Reading classics dating as far back as The Iliad has given me not just a fuller appreciation for the history of literature but also a wider view of humanity—who we have been and how we have thought, century by century.

2. Pursue Drama

Don’t stop at reading. Do the same with other art forms, particularly the dramatic arts. Movies and TV are so easily accessible these days that visual storytelling has arguably become our culture’s most prevalent form of communication.

Watching film (or plays or operas) offers us many of the same opportunities as written fiction—a story communicated from the mind of one person to another, as well as insightful sketches of the characters. More than that, however, visual mediums allow us to watch actual human beings. Although actors rarely portray themselves, they share with writers the inevitability of revealing true things about themselves as well as their characters.

To the person who watches with attention, visual stories can teach us many, many things (subjective and objective) about what it means to be human.

3. Pursue History

Literature (and to a more limited extent film) offers us glimpses into the vastness of our accumulated human experience. But why stop there? History is valuable to every writer, not just those writing historical fiction. Understanding the evolution of society, of politics, of religion, of technology, of fashion, of food—all these subjects are crucial to helping us understand ourselves and others.

Spanish philosopher George Santayana famously observed:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

I’ve always been a history buff, but I widened my scope after the 2018 Winter Olympics when I realized how little I knew about so many of the represented countries. My latest reading challenge is to try to read a book of history about every country.

4. Pursue Philosophy and Science

The philosophies and the sciences offer us the current and accepted compendium of human understanding thus far. I’m not likely to figure out Newtonian physics by myself (much less Quantum physics), but I can get an overview on subjects that my ancestors would never have dreamed of. I can view the progression of human thought—the ideologies that have come and gone and those that have under-girded my own modern beliefs in ways I would otherwise be totally ignorant of.

These subjects are largely the study of life itself. Like our own pursuit of understanding ourselves, the current amount of known information is dwarfed by the magnitude of the subjects. But taken in combination with every other method available to bring awareness, insight, and honesty to our human experience, they offer profound tools for any writer seeking to understand people as a route to writing better characters.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What has been your best help for understanding people and writing better characters? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/understanding-people.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post A Writer’s Guide to Understanding People appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 14, 2019

This Is How to Transform Info Dumps Into Exciting Plot Reveals

Clues, mysteries, plot reveals, and plot twists—these are some of a writer’s stock tricks for hooking readers page after page. But as important as these tricks are, when they’re asked to bear the load of being the main attraction for readers, they too often turn into boring info dumps.

Clues, mysteries, plot reveals, and plot twists—these are some of a writer’s stock tricks for hooking readers page after page. But as important as these tricks are, when they’re asked to bear the load of being the main attraction for readers, they too often turn into boring info dumps.

Imagine you’re reading a story in which the author has skillfully created some kind of mystery.

This mystery might be:

The murder in a whodunit.

A straightforward strategic puzzle focused on figuring out how to defeat the bad guys.

Something more domestic, such as an ongoing question of a character’s parentage.

Something simple and amusing, such as a character obsessively (and perhaps symbolically) trying to prove that a neighbor’s dog is digging holes in his yard.

Less about proving a proposed solution and more about figuring out whether or not something mysterious is happening at all—e.g., is the new neighbor’s strange night activity a sign of something sinister?

The mystery could be the main focus of the story, with the protagonist’s main plot goal being the solution to the mystery (as in Chamber of Secrets). Or the mystery might just be a clever way to avoid info dumps while slowly trickling important information throughout the story (as in Half-Blood Prince).

Whatever the case, adding a mystery can greatly enhance your story’s readability. If you’re able to consistently present questions (whether implicit or explicit), you’re giving readers more reasons to keep reading. In addition to wanting to watch what happens to your characters, they now also want to know the answer to the questions you’re proposing.

But don’t miss the order of that last sentence. Readers are there first and foremost to see what happens to your characters. And this is where we encounter some of the problems you can run into if you’re relying too heavily on plot reveals to provide the entertainment factor.

Ask Yourself: Is Your Story About Clues or Consequences?

Mysteries are fun. They’re fun to create and fun to solve. But in themselves they are not stories and certainly not the best part of stories (even in the mystery genre). This is why it’s important for writers not to fall into the trap of relying on clues to carry the story.

In the myopia of early plotting, it can be easy to feel you’re writing something deeply gripping just because a new clue is being unveiled in every scene. In these instances, the plot progression may look like this: Clue>Clue>Clue>Clue. The progression grows obviously monotonous, no matter how interesting the mystery itself.

E.M. Forster famously distinguished story from plot by emphasizing the causality of events.

The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then queen died of grief is a plot.

In dramatic fiction, things don’t just happen. They happen because other things happened first. This certainly holds true for the unraveling of mystery. If the revelation of clues are just revelations, the story will stagnate. Instead, any and every clue your plot reveals should be the result of a character’s choice, with the discovery itself turning the plot by creating consequences.

You want the progression of your story to look like this: Choice>Consequence>Choice>Consequence. (Which is, of course, just a variation on how to view classic scene structure of Goal>Dilemma.)

Even just glancing at the two equations shows the difference. For me, the latter progression, of choice and consequence, immediately blips my writer radar. The reminder that my character’s choices have causal consequences always functions for me almost like a writing prompt. So many juicy possibilities.

Focusing a story’s progression on choice and consequence creates forward momentum—a line of causes and effects. Even better, it creates a much more interesting framework in which to leverage a story’s mysteries, questions, and revelations.

5 Ways to Turn Info Dumps Into Plot Turns

Maybe you can relate to this: A writer hands beta readers a story that the writer feels is jam-packed with exciting action.

But the beta readers are all bored. “Nothing happens,” they complain.

The writer is bewildered. “All sorts of things happen! The heroes learn all this stuff about the bad guys’ plans and what they have to do to defeat them!”

It may take several more drafts and much confused agony before the writer realizes the reason it feels like nothing happens in this “jam-packed” novel is… because nothing does happen.

The characters may be learning lots of exciting and revelatory stuff. But that’s all they’re doing. They’re sitting around in a boardroom while their spies bring in horrifying reports. Or they’re taking lesson after lesson in order to gain the knowledge and skill necessary to finally defeat the bad guy (lookin’ at you, YA fantasy). Or maybe the two love interests spend more time thinking about each other or small-talking than they do actually getting out there and falling in love.

With the best intentions, the writer accidentally left most of the story’s best stuff on the cutting-room floor. The problem isn’t that the story’s reveals of information are necessarily uninteresting. Rather, the problem is that the information is the story. And that’s boring.

Fortunately, you can have your cake and eat it too. Mysteries and plot reveals are wonderful. They just need to be sown into the causal fabric of your characters’ deep and primal plot struggles.

To that end, here are five principles to keep in mind.

1. The Character Explicitly Wants/Needs/or Doesn’t Want This Info—or Some Combo Thereof

Identify a motive for why your character will have more than a casual relationship with this information.

We all learn bits and pieces of things every day—someone was born, someone died, somebody did something good, somebody else did something bad. Some of these bits may interest us, but most are incidental. We have no life-changing motive to seek them out and no subsequent reason to interact with them.

For us, that’s okay. But the information you introduce in your story is information that matters to your protagonist. It’s info that’s going to change his life, which means he absolutely has a reason to interact with it.

The one big exception to this principle is that your story’s mystery may begin with a bit of info the character initially didn’t know he needed—but which very quickly becomes important for some reason (even if it’s just a burning need to know what the nocturnal new neighbor is up to over there).

That aside, you will instantly gain so much more story power by looking for ways to instill your story’s revelations with meaning and stakes.

What is of particular note here is the possibility of having your character choose to learn this information. This is just one of many ways to keep your character from being a bystander in his own story. It also means that when consequences ensue, the protagonist will not be a victim, but will have to shoulder the full load of responsibility for what he has learned (see #4 below).

2. Information Is Never Free

Your character’s choice to seek out information should ultimately be more weighty than her simply deciding to tap her finger on random click-bait on her phone. It should be a choice she has to think twice about—because it, unlike the click-bait, isn’t free.

Except in instances where it would unnecessarily bloat a story, your character’s choice to seek important information should come with complications (and this is before we even get to the consequences). She might have to give up some of her hard-earned babysitting money to bribe info from the school stooge. Or she might have to risk detention by skipping class. Or she might have to face her own fears to talk to somebody dangerous.

It’s possible she may not immediately understand the full cost of what she’s paying to gain this info, but the sooner readers understand the stakes, the more currency you’ll generate for character development. Naturally, not all your characters’ dilemmas will be life-shattering, but you should try to wring a little blood whenever you can by creating situations in which characters must either choose between two equally bad options or two mutually-exclusively good options.

When a character “pays” for info, readers know the info is going to be worth their time.

3. Knowledge Is Power—And With Power Comes With Great Responsibility

Welcome to Pandora’s box. Your character really, really wanted/needed/tried to avoid knowing something. But now that he does know, he can never return to ignorance. (This is true of massively life-changing reveals, but it should also echo down to the relatively small clues leading up to the big reveals.)

It’s much better for your character to learn bad news than good news. There are, of course, exceptions (and you’ll want to vary the intensity of your character’s discoveries either way), but bad news is what builds a story’s conflict and the protagonist’s increasingly pressing need to push through to the resolution of the plot goal.

Although stories can certainly reveal objectively good information, that’s not the stuff of mystery. Mystery is all about tension. Whether rightly or not, the character suspects something bad behind the closed door. If he thought it was something good, the stakes wouldn’t feel as high—and readers wouldn’t be as interested in discovering the truth.

When your character chooses to ask a question, only to receive a disturbing answer, the stakes rise. Because he chose to seek out or interact with this information, he is now responsible for his own knowledge. Whether or not he wants to do something with that knowledge (even if, for now, it’s just seeking the next clue), he increasingly feels the weight of obligation. He’s going to have to make a move (hello, plot turn!), and that is where his choices become consequences.

4. Clues Should Be Visual Whenever Possible

One of the big problems with the progression of Clue>Clue>Clue is that it’s boring. It turns what might indeed be exciting info into a dry recital of facts.

When a private slogs up to the general, salutes wearily, and says, “Sorry, sir, we lost the whole battalion”—that’s nothing but words. But when the general drives out to visit the battlefield and readers get to visualize the carnage through his eyes, the information becomes more than just information.

In a nutshell, this is simply a decision to convey the information through showing, rather than telling. Stories should be pictures on the page. Information, whenever possible, should be visceral. It should be sensory. Smelling a fire, hearing a siren, or seeing a roof collapsing under a blaze—all of these things convey information that might just as easily be learned from a newspaper article. But the visuals not only pack more punch, they also force characters to get out in the story world and do something.

5. Even Better, Clues Should Be Dramatized

If it’s better to convey information via word-pictures, it’s often one more step up from that if you can sow the revelation into the very heart of a scene’s dramatic action.

Maybe your character is hunting for proof that a legendary monster exists. He could discover that information in a dusty old book. He could hear about it from the lips of a creaky old grandmother who swears she saw the monster as a girl. He could even see the monster through his binoculars.

Or he could just about be eaten by the thing.

When your character is given the opportunity to learn on the job by personally and physically interacting with new information, the possibilities for plot-turning consequences pop up all over the place. Maybe the character’s guide (the old granny?) is eaten. Or maybe he loses an arm. Or maybe he accidentally herds the monster into an unsuspecting village, where it wreaks havoc.

As fast as that, this is no longer a story in which “nothing happens.” It’s a story in which information becomes more than a recital of facts, but rather an actual force for your protagonist to contend with.

***

Now it’s time for you to take a look at your story and ask yourself the following questions:

1. What bits of information are crucial to your plot?

2. Can you rework that information’s delivery so it isn’t presented straight up, but rather doled artfully with a bit of mystery and flair?

3. From there, can you go yourself one better and figure out ways to create a fraught relationship between your characters’ need to learn the information and the consequences when they do?

4. And, finally, can you brainstorm ways in which to show the information in visually dramatic ways that progress the plot?

You can use all four of these techniques to create mystery and character development in any type of story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you think of a scene in which your protagonist has acquired new information in a visually dramatic way rather than learning about it in an info dump? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/plot-reveals-and-info-dumps.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post This Is How to Transform Info Dumps Into Exciting Plot Reveals appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

October 7, 2019

A Challenge to Write Life-Changing Fiction (+Giveaway)

Stories have intentions.

That wonderful idea was just one of many nuggets I found myself highlighting in what has so far turned out to be my surprise read of the year—noted literary agent Donald Maass’s The Emotional Craft of Fiction.

Like many of you, I cut my teeth on Maass’s now-classic Writing the Breakout Novel, but for whatever reason never followed up with any of his other many writing guides, even though they’re all on my TBR list. Fast-forward sixteen years to when I caught Emotional Craft of Fiction as part of a Kindle sale. I started reading it about a month ago, fully expecting a smart but conventional tome of tips for drawing dimension into characters. I got that, but what I wasn’t expecting was that, non-fiction though it is, this would be one of those books with “intentions.”

The Emotional Craft of Fiction by Donald Maass

Just as the best of all writing advice should, the wisdom found in this book applies to so much more than just writing. If storytelling is about exploring life, then good writing advice should inevitably evoke solid life advice as well. (Which, on a side note, is what I’m excited to learn Wesley Baines, a familiar name on this site, is exploring in a forthcoming book about the importance of writers developing traits such as empathy and wisdom.) I find it no coincidence that the two great interests of my life—storytelling and personal growth—continually converge. They are, in so many ways, the same interest.

Many people have taken the time to tell me they enjoyed my book Creating Character Arcs more for its insights into their own life changes than for that of their characters. My response is always an eager, “Right?!” Because that was totally my own experience in discovering character arcs. For me, understanding how to convincingly portray human change on the page was ultimately a journey in understanding how I change and grow.

That, in itself, should be reason enough to go out and read Maass’s book right now—because its great insights into character crafting are really just an emergent of its insights into life itself. The book (intentionally?) came to me at exactly the proper moment in my own life, as I am neck deep in working on emotional fluency.

More than that, however, I found Maass’s book and his comment about “intentional stories” to be a rallying call to writing not just authentic fiction, but the kind of fiction that both invites and encourages readers to follow the characters on Positive-Change Arcs.

I’m not even going to try to do justice to the vastness and depth of the topics Maass covers, but after finishing the book, there are two things I want to do.

1. I want to share a few of my own thoughts on why and how to take up Maass’s challenge to start (or continue) writing not just fiction, but life-changing fiction.

2. Because I want everybody everywhere to read this book, I’m giving away 10 paperbacks to random winners. Scroll to the bottom of the post to enter using the Rafflecopter widget. Winners will be selected at the end of the week. If you don’t win, please find a copy somewhere else and read it! You gotta pinky promise.

5 Starters for Writing Life-Changing Fiction

There are so many different kinds of stories—everything from heroes’ journeys to stream-of-conscious mirrors of prosaic days, from fantasies to exposés, from comedies to tragedies, from genre mashups to literary tomes. There’s something for every one of us at every moment of our lives. Every single type of story has within it the potential seed to absolutely transform at least one of its readers.

Those are the stories I want to read and watch. They don’t come along very often, but when they do, they are nuclear.

I would like to write these stories as well. (Even if the only reader who is changed is me, I’d still be pretty happy with that.) To that end, here are some ideas I’ve mulling on, some of which coincide with those presented in Maass’s book, others which were catalyzed for me by the book.

1. Write With Honesty and Self-Awareness

It’s not stories that change people’s lives; it’s the truth. When stories speak truth, it’s like they’re puzzle pieces fitting into inner holes the audience didn’t even realize were there. There’s a line in Jonathan Latham’s essay in Light the Dark that talks about how when you encounter something true, it doesn’t feel like you just learned something new. Rather, it feels like you suddenly remembered something you knew all along.

The only way to write truth so powerful it gives readers that dichotomous sense of coming home to a place they’ve never before visited is by daily doing your utmost to clear away your own inner fuzziness. Cognitive dissonance, defensive egos, and repressed emotions are things we all deal with that inevitably muddy our thinking. As human beings, we bear the responsibility to try daily to do a little housecleaning. As writers, that responsibility is doubled. When asking readers to suspend disbelief, we are implicitly asking them to believe we will share with them something true. That’s a contract of trust.

2. Write With Humility and Humor

But let’s not be pompous, shall we? Every day for me is a discovery of some life-truth that astounds and excites me. I want to share every one of those truths with every single person I can. But even in the midst of my own enthusiasm (and, sometimes, overweening pride at my unprecedented cleverness), there’s a part of me that knows full well not all my truths are going to be interesting to others. Indeed, not all of my truths are really true. Today’s certainty may turn out to be tomorrow’s mirage.

If, in writing, we accept the terrible responsibility of speaking truths to our neighbors, then we also do well to acknowledge our own unsuitability for that role with more than a little self-deprecation. I want to tell the truth; I want to change your life. But, c’mon, I’m just a struggling schmo too. Very likely, that’s the greatest truth I’ll ever know or share.

3. Write Actionable Fiction

As a reader and especially a viewer, I spend an inordinate amount of time preemptively bypassing stories that seem hellbent on sending me to bed with a downer. I love incisive, hard-hitting, even dark fiction—but not if it gives me dog-breath from the bad taste in my mouth.

Maass nailed it when he wrote:

Some people may read fiction to be frightened, but they never read it to be brought down. They may wish to be challenged, but they don’t want to be crushed. They may read for amusement, but they still have heart. They do seek an emotional experience, as I’ve said, but they also want to come away feeling positive.

I think of some of my favorite stories—The Great Escape, The Book Thief, Gladiator, Wuthering Heights, Black Hawk Down, True Grit—and I’m rather surprised to realize how dark they all are, how most of them end in quantifiable tragedy. And yet… and yet. What these stories have to say about the world is anything but tragic. They tell hard truths, but in the end those truths feel triumphant.

The insight I find most poignant in Maass’s quote is that we should be striving to write actionable fiction. In the same way copywriters are taught to end with a call to action (something people can immediately respond to after hearing about the benefits of the advertised product), fiction writers should also consider what the end of a story may be encouraging readers to do in their own lives.

This does not mean ending with some blatant moral that tells readers to go out and make the world a better place. But we all know the feeling of inspiration found at the conclusion of the kind of story that very well just changed our lives.

This call to action is most important in stories that tell dark truths. Otherwise, the message is “roll over and die.” Stories of injustice, stories of horror, stories of death—they should be about more than just injustice, horror, and death. They should be about what we can do about these tragedies in our own lives after closing the back cover of the book.

4. Write to the Find the Best of Yourself

When you read your own stories, who do you see? It can be hard to identify the person peeking out from between the lines. But take a hard look. If the person you see has been honestly represented, then very likely she’s not a perfect person. She may be full of rage, pain, and fear. She may be downright scary. That’s okay.

But don’t leave it at that. Don’t let your fiction be nothing more than a place to vent all the hard parts of being you. See if you can’t also find the best of yourself looking back at you.

Maass again:

This may sound like I’m in favor of pandering to readers, but I’m actually appealing to the good, positive, and inspiring person called you. Don’t give me easy reading; give me the best of you. When you do, it becomes the best of me, too. Do you believe that it cheapens fiction to make it humane, heart grabbing, filled with goodness? You are not alone in that belief, but I disagree.

The best of you is not some fake version of fairy-tale perfection. The best of you is that enraged, hurting, fearful person who rose above herself and found change. That’s the person I want to know when I read your stories, because that’s the person who is going to inspire me to rise as well.

5. Write Fiction That Hopes

Sometimes it’s hard to even know for sure which stories have changed your life. Sometimes they don’t obviously change us until long after we’ve read them. But sometimes you know.

This summer, I had the opportunity to watch the extended versions of the Lord of the Rings movies on the big screen as part of a “flashback cinema” program at my local theater. Over the course of three weeks, I sat through all 11 hours and 22 minutes. As a kid, I remember the news gushing about how “life-changing” the films were. For me, this time, they were. It felt like an incredible to gift to get to experience this particular story in this particular medium at this particular time in my life. Samwise Gamgee tells us “there’s some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for”—and, just like that, my life is changed.

You can change the world with stories of of truthful darkness or even despair. But I can’t help but believe, in agreement with Maass (and Sam), that it is much better instead to choose a different catalyst of change—the catalyst of hope:

You are writing to show us how things are, but aren’t you also writing to show us how things can be? Your current novel is not just a report, right? It’s a vision. It’s a gleeful celebration of what is hard, important, hopeful, and beautiful about life.

***

There are so many reasons to love stories. And as humans, we do—we truly do—love stories. Speaking at least for myself, I think the single greatest reason I first fell in love with stories, and continue to follow them even to this day as the guiding stars of my life, is their power to change me. If a story creates no impact in my life, then I find I am invariably disappointed on some level. I want to be changed. I want every day to be a transformation. That is why I read, and that is why I write.

And that is why I want you to read Donald Maas’s inspiring challenge to write stories of depth and meaning. Be sure to enter the giveaway below. I leave you with a final quote:

Novels that are truly grand, generous, and confident do not come along very often, but why can’t such novels be yours every time?

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s a story that changed your life? How has it inspired you to want to write life-changing fiction? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/write-life-changing-fiction.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post A Challenge to Write Life-Changing Fiction (+Giveaway) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 30, 2019