K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 32

December 30, 2019

Top 10 Writing Posts of 2019

Goodbye, 2019. Hello, 2020.

Goodbye, 2019. Hello, 2020.

As you look back on 2019 (and the whole decade really), I hope you’re able to remember all the challenges you’ve conquered, the goals you’ve met, and the ways in which you’ve grown—as both a writer and a human.

For me, 2019 was a year of deep growth, mostly on an internal level. It was a year in which I struggled with things I never thought I’d struggle with (including writer’s block), but it was also a year that brought me deep insights and perspective shifts. Largely because of this, I see 2020 as a new chapter, and I look forward to what the turn in the road may bring.

I was super-kind to myself (mostly) when it came to writing this year. I kept plugging along on my outline for Book 3 in my Dreamlander trilogy, but it’s admittedly been slow going. I have plans for next year that I hope will help me return to the creative flow in a strong way.

Looking back on 2019, I’m actually pleasantly surprised to realize how much I did accomplish:

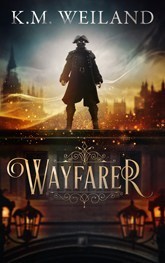

Publication of my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer .

Release of audio versions of 5 Secrets of Story Structure and Dreamlander .

Deals for Russian and French translations of Structuring Your Novel .

6th mention of Helping Writers Become Authors in Writer’s Digest’s 101 Best Websites for Writers

Finished rough draft of a new writing-craft book Writing Your Story’s Theme.

Next year, my modest (but exciting) plans include publishing the aforesaid Writing Your Story’s Theme, possibly producing a paperback version of Conquering Writer’s Block and Summoning Inspiration (at your request), finally migrating my podcast over to a new platform that’s more friendly to those who use platforms other than Apple, finishing that outline for Book 3 in my fantasy trilogy, and hopefully getting a good start on edits for Book 2 aka Dreambreaker.

As always, I’d also like to stick in some traveling, although I’m not sure where yet (ideas?).

Thanks so much for joining me throughout 2019, and I hope to see a lot of you in the coming year! Just in case you missed or would like to revisit them, here are my top 10 posts from 2019, according to page views.

My Top 10 Posts of 2019

1. How to Use a “Truth Chart” to Figure Out Your Character’s Arc

2. Learn 5 Types of Character Arc at a Glance

3. 8 Quick Tips for Show, Don’t Tell

4. 6 Requirements for Writing Better Character Goals

5. Plot, Character, and Theme: The Greatest Love Triangle in Fiction

6. How to Write Interesting Scenes

7. 7 Things to Try When Writing Is Hard

8. 4 Pacing Tricks to Keep Readers’ Attention

9. What Is the Relationship Between Plot and Theme?

10. 5 Ways to Use Theme to Create Character Arc (and Vice Versa)

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What was the most memorable writing event in your 2019? Tell me in the comments!

The post Top 10 Writing Posts of 2019 appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 23, 2019

Merry Christmas, Wordplayers!

Merry Christmas, everyone!

Merry Christmas, everyone!

As we close out this decade, I find my heart is full of gratitude—for so many things, but especially for you.

I’m thankful for your time and attention, that I get to share some of my journey with you, as you also share your journeys with me. I’m thankful for every one of you who reads this blog or listens to the podcast, and I am thankful for those of you who take even more of your time to leave a comment, start a conversation, or send me an email with a joke, a comment, a question, or sometimes simply the gift of encouragement. I’m just a voice and a face out here in Internet land; it is amazing and deeply humbling to me that so many of you take precious time and effort from your own lives to brighten my day with a kind word or a report on how this site helped you reach a milestone or success in your writing.

I’m thankful to so many of you who have shared your own knowledge and experience with me, this year and always. Not only would I be unable to do what I do without you, but my life would be dull and drained indeed. Thank you for the work you do to make the world a better place.

And thank you to those of you (most of you!) who write. I thank you for your stories, your courage, your vulnerability, your honesty, and your struggle. I don’t think there has been a moment in my entire life when I have not known in my heart that telling a story was vital, but the older I get, the more I consciously believe that telling a story—and telling it well—is one of the most tremendous contributions any human can make to the world.

Some of your stories have changed my life. Some of your stories have changed my life because they changed your life. Some of your stories have changed me because they’ve changed other people. And some of your stories may yet prove themselves to be touchstones of Truth in our future.

Thank you for your passion, for walking beside me on this path, and letting me walk beside you.

Merry Christmas and Happy 2020!

The post Merry Christmas, Wordplayers! appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 16, 2019

Supporting Characters and Theme: 6 Important Questions to Ask About Your Story

Raise your hand if you’ve ever written in a new supporting character just because, hey, somebody had to start that tavern brawl. Creating delightfully colorful, unexpected, and sometimes just plain convenient minor characters is half the fun of writing. That said, we might all want to now sit on those hands we raised. However random our supporting cast may sometimes seem, writers mustn’t overlook the crucial correlation between supporting characters and theme.

Raise your hand if you’ve ever written in a new supporting character just because, hey, somebody had to start that tavern brawl. Creating delightfully colorful, unexpected, and sometimes just plain convenient minor characters is half the fun of writing. That said, we might all want to now sit on those hands we raised. However random our supporting cast may sometimes seem, writers mustn’t overlook the crucial correlation between supporting characters and theme.

In short, the more important your supporting characters, the greater your responsibility to ensure they contribute more than just that first punch to get the conflict going. Once you’ve properly set up the foundations of your story’s thematic presentation (via your protagonist’s arc and your antagonist’s generation of the plot conflict), your supporting characters are going to provide your greatest opportunity for deepening the complexity, maturity, and subliminal power of your story’s thematic premise.

I’m going to repeat an analogy I’ve used before because it’s one of my favorite ways to view theme:

Think of your overall theme as a big mirror smashed on the floor. The biggest chunk of glass is your protagonist. The second biggest is your antagonist. And every other shard represents every other character. They all reflect the theme. They all show a different piece of the big picture.

Naturally, the bigger the piece of glass—the bigger the character’s role—the more explicit its relationship to theme should be. But ideally even the walk-on character with no lines can present symbolic opportunities. Think about it: the character who starts that tavern brawl could be a drunken miner, a bartender, a little girl, a fancy gambler, or the landlady. Even if that’s all that character contributes to the story, each choice is going to say something a little different within the context.

If dreaming up thematic significance for each and every supporting character sounds like a lot of work, don’t worry. With a little practice, using thematic criteria to choose or groom supporting characters will become second nature. More than that, it’s a fun and effective way to create a surprising and dimensional cast.

6 Questions to Refine Your Supporting Characters and Theme

To help you get a sense of how your supporting characters can play a defining role in strengthening and deepening your story’s theme, here are six questions. Eventually, these questions should become instinctive, but until then you can use them as a reminder of ways in which you can spot and take advantage of missed opportunities.

1. How Does Each Supporting Character Represent the Theme?

Take a moment to scan your cast. If every character is pertinent to the forward progression of your story’s plot, then there’s already a strong probability these characters have a strong thematic impact as well. Still, it’s easy to miss the forest for the trees. For that matter, thematically vetting supporting characters can be a great way to spot weak spots in their relation to the plot as well.

Refer to the question inherent within your story’s thematic premise. Is each prominent character asking (or answering) some version of this question?

For example, if your story is about duty, your characters may ask any range of questions from “What is duty?” to “Do I owe duty to a tyrant?” to “Can doing your duty go against your conscience?” to “Am I hiding behind my duty?” to “Am I hiding from my duty?”

The more varied the questions, the more opportunities you will have to explore your thematic premise from every angle.

2. Which Supporting Characters Reflect Positively on the Theme and Which Reflect Negatively?

To create a well-rounded exploration of theme, you will want to look at it from as many angles as possible. Some characters should argue for the thematic Truth; others should argue just as passionately and logically against it. (If you at least occasionally find yourself almost convinced by your antagonist’s arguments, you know you’re doing a good job.)

There’s little point to having multiple characters represent the same thematic position within the story. Look for as much variety as possible. See if you can create a character who will represent at least each of the following:

A stalwart, unchanging relationship with the Truth.

A stalwart, unchanging relationship with the Lie.

A change arc from Lie to Truth.

A change arc from Truth to Lie.

3. Which Characters Will Influence Your Protagonist’s Relationship to the Theme and Which Will Be Influenced By the Protagonist?

Your protagonist’s relationship to the plot and the theme is your story. It’s the structural and symbolic backbone that proves whether the whole thing works or not. When it comes right down to it, your supporting characters only matter to the story insofar as they move the needle on the protagonist’s relation to the plot and/or the theme (preferably both, of course).

If for the moment we simplify the idea of theme to a question, then the supporting characters will reflect that theme by positing various answers. Some of those answers may help the protagonist find the ultimate thematic Truth he needs to win or transcend the plot’s physical conflict. Other answers may be convincing in their ability to tempt him away from that Truth but ultimately negative in their impact upon the ending.

It may also be that a supporting character is impacted by the protagonist as much or more than the protagonist is impacted by the supporting character. Especially when the protagonist is demonstrating a Flat Arc (in which he is largely unchanging in representing the story’s thematic Truth throughout), the supporting characters may be the ones most changed by the theme.

4. How Does Each Minor Character’s Personal Goal/Conflict Comment Upon the Theme?

Now that you’ve examined your supporting characters’ contribution to your story’s thematic big picture, it’s time to get a little grittier. It’s not enough simply to identify the personal beliefs that align a supporting character with either the Truth or the Lie. You must make sure those personal mindsets are demonstrated (aka, shown not told) on the scene level in ways that actually move the needle on the plot.

The easiest way to gauge this is to consciously choose your supporting characters’ personal goals, first within the plot as a whole, then within each scene. In the busyness of making sure your protagonist’s goal and conflict are happening in each scene, it can often be easy to overlook the causal and thematic importance of each and every supporting character’s scene goal. Paying attention to supporting characters’ scene motivations and desires will not only amp their credibility as whole human beings, it will also provide incredible opportunities for deepening the holistic complexity of your plot conflict and your thematic argument.

5. How Does Each Supporting Character’s Climactic Moment Reflect Your Protagonist’s Thematic Climax?

Your protagonist provides both the structural and thematic throughline for your story. It’s her Climatic Moment that will end the conflict and “prove” the thematic premise. Your supporting characters are there to support that outcome. They should not overshadow the importance of the protagonist in these finale moments. (If any character other than the protagonist takes center stage in the Climax, you have to ask if you’ve chosen the right protagonist.)

Some of your supporting characters may be present in the actual Climax, but many others will offer their final impact on the plot in earlier scenes. Either way, look for opportunities to end these characters’ thematic conversations in ways that snowball into the protagonist’s finale.

This might look like any of the following:

The supporting character actively influences the protagonist in moving toward the thematic end.

The supporting character is directly influenced by the protagonist’s thematic choices in the Climax.

The supporting character symbolically foreshadows or reflects the protagonist’s end, either supportively or ironically.

6. What if a Supporting Character Doesn’t Provide a Thematic Reflection?

Now we come to the final important question you can ask about your supporting characters. What if they don’t have any relationship with or reflection upon the theme?

First of all, don’t panic. Not every character has to comment upon the theme. That character who started our tavern brawl may not need to offer anything more than the first punch to get the scene rolling. But here are two rules of thumb for judging whether you’re missing an opportunity for thematic depth or, in some cases, risking a huge theme hole:

1. The smaller your cast, the tighter your thematic representation must be.

If your story is Death of a Salesman with only a dozen characters, then every character matters. The specificity of every character, within both the plot and the theme, must be drawn sharply. If, however, your story presents the proverbial cast of thousands, you’ll have much more room for error.

2. The more important the character, the bigger the thematic footprint must be.

Although there may be occasional characters whose impact far outweighs their actual screen time, usually their importance within the story can be judged on the size of their roles. Walk-on characters with no lines clearly land at the bottom of the pecking order, while archetypal allies and enemies command the most influence upon plot and theme. You can get away with colorless and meaningless walk-ons, but the more scenes in which certain characters appear and the more dialogue they have, the greater their thematic importance.

Basically, if a character is moving the plot, that character should be vetted for thematic integrity.

***

Although not always immediately apparent, supporting characters and theme are made to serve one another. If your supporting cast is solid, that’s a good indication you’re executing your theme solidly as well. And if your theme is progressing nicely, it’s probably a good sign you’ve created a memorable and pertinent cast of supporting characters. Using theme to vet supporting characters (and vice versa) is one of your best tools for pulling off a solid and holistic story. Try it out!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How have you consciously paired your supporting characters and theme in your story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/supporting-characters-and-theme.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Supporting Characters and Theme: 6 Important Questions to Ask About Your Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 13, 2019

It’s Here! Dreamlander Audio Book

It’s my pleasure to announce, to all of you who have been waiting for it (for a really long time), that the audio book version of my portal fantasy Dreamlander is now available, narrated by C. J. McAllister.

It’s my pleasure to announce, to all of you who have been waiting for it (for a really long time), that the audio book version of my portal fantasy Dreamlander is now available, narrated by C. J. McAllister.

To date, I’ve produced audio versions of all my non-fiction writing-craft books, but this is my first foray into audio for my fiction. It’s something a lot of readers have been asking for over the years, so I’m excited to finally be able to offer it!

You can grab it off Amazon, and if you’re not an Audible member yet you can even grab it for free by signing up!

About the Audio Book

What if dreams came true?

What if it were possible to live two very different lives in two separate worlds? What if the dreams we awaken from are the fading memories of that second life? What if one day we woke up in the wrong world?

In this fantasy thriller, a woman on a black warhorse gallops through the mist in Chris Redston’s dreams every night. Every night, she begs him not to come to her. Every night, she aims her rifle at his head and fires. The last thing Chris expects—or wants—is for this nightmare to be real. But when he wakes up in the world of his dreams, he has to choose between the likelihood that he’s gone spectacularly insane or the possibility that he’s just been let in on the secret of the ages.

Only one person in a generation may cross the worlds. These chosen few are the Gifted, called from Earth into Lael to shape the epochs of history—and Chris is one of them. But before he figures that out, he accidentally endangers both worlds by resurrecting a vengeful prince intent on claiming the powers of the Gifted for himself. Together with a suspicious princess and a guilt-ridden Cherazii warrior, Chris must hurl himself into an action-adventure battle to save a country from war, two worlds from annihilation, and himself from a dream come way too true.

The post It’s Here! Dreamlander Audio Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 9, 2019

Critique: 10 Ways to Write a Better First Chapter Using Specific Word Choices

The one thing all writers are trying to do is write a better first chapter. First chapters are do-or-die territory. We know this as writers because we know this as readers. Most of us make our reading choices after scanning the first few paragraphs of a story. Sometimes we know if we want to go on after as little as a few sentences.

The one thing all writers are trying to do is write a better first chapter. First chapters are do-or-die territory. We know this as writers because we know this as readers. Most of us make our reading choices after scanning the first few paragraphs of a story. Sometimes we know if we want to go on after as little as a few sentences.

As writers who have put hundreds, even thousands of hours into writing the entirety of a book, we often feel this swift judgment is a little unfair. After all, first impressions aren’t always right. Several of my all-time favorite books weren’t ones that grabbed me off the bat; it was only my compulsive perseverance that allowed me to open up these stories’ true gifts. But 75-90% of the time, readers are going to make the correct decision about a book after reading just the first chapter or so.

Why is this? How can readers make an accurate decision about a book with so little information? What little signals are writers giving readers that let them quickly make up their minds?

Ultimately, what readers are looking for are signs that the writer has skill enough to be trusted with their time. Readers can’t know from the first chapter whether or not the writer can spin a good yarn all the way to a satisfying conclusion. But readers will always recognize whether or not the writer knows how to write. A skillful writer can hook readers through prose alone. The reader thinks, Ahh, this is good—and suddenly that all-important trust in the writer’s skills begins to percolate.

Learning From Each Other: WIP Excerpt Analysis

Today’s post is the sixth in an ongoing series in which I am analyzing the excerpts you have shared with me. My approach to these critiques is a little different from those you normally see on writing blogs. Instead of editing each piece, I’m focusing on one particular lesson that can be drawn from each excerpt, so we can deep-dive into the logic and process of various useful techniques.

Today, my thanks to Dawna J. Wightman for sharing from her dark fantasy FARR. Her excerpt immediately hooked me. If I were scanning this book on Amazon, I would want to read on. That’s why I want to break down what, specifically (and that’s the key word), grabbed me and made me believe she is an author I can trust to tell me a ripping good tale.

Let’s take a look! The bolded entries and subscript numbers will correspond with the tips I’ll talk about in subsequent sections.

Before the bad thing happened,1 we were just us five Raessen kids running around the farm.2 Sure, we took sides: the Peter Liam Bob team against me and Shone. Odin wasn’t born yet. When everybody was getting along we’d play chase or tag or hide-and-seek, but just me and Shone, just the two of us, was the best. Queen Shone and Queener Campanula.3 We’d spin bits of fleece from the farmer’s sheep, play dress up and pretend we were trying to escape the evil fairy king by reading messages written in blood across egg yolks that we tossed back in triumph.4 When it was just me and Shone, we always won. Me and Shone were closer than quarter to nine.5

Us kids fished in the creek and it didn’t matter that nobody knew how to swim. The nearest farm was miles away, so it was just us to hang around with—us and Ma and Dad in the rented farm house. Cozy.6

They danced sometimes before he went off to work, and we all laughed because he didn’t have far to go. The new strip mall was digging in at the back of our property. Dad worked construction. We even ate at restaurants sometimes and my favorite was Miss Chinatown. Ming May, the owner, even gave me a free egg roll once.

But then the bad thing happened; Shone went missing.7 One minute she’d been sitting next to Crinkle Creek, plucking daisy petals, next minute I came back with our poles, she was gone. White petals on black water.8

Her body was never found. I hate the sound of that, “her body”—she was so much more than “her body”—she was a person, a girl, a bright light with skin on it and taming my fuzzy braids with rubber bands and boy secrets under her blankets and letting me borrow her clothes and saving the best cupcake for me because she was my sister.9

After Shone, our family cracked. Ma started with those red pills and her sweeping ceilings all the time and she snipped off every button from every coat.10 The house was always too noisy… the sad making it quiet, all of us always moving and making a mess. My head felt like it was going to explode.

10 Ways You Can Write a Better First Chapter

First chapters are notoriously complex in the multiple jobs they must execute seamlessly—introducing characters, settings, and conflict all in a way that seduces readers deep into the dream world you wish to share.

>>Click here to read The Ultimate First Chapter Checklist

A good story is created from the combination of so many important factors. As we talk about so often on this site, solid story structure, character arcs, and themes are a huge part of what makes a story work. If any of these things are broken, readers are unlikely to find deep satisfaction by the time they finish your story. But it won’t matter how great your execution of story theory may be if you can’t first hook readers with your first chapter. You’ve got to convince them to read the doggone thing first.

To that end, let’s break down how Dawna convinced me.

1. Hook Readers With a Specific Question

First, you gotta land that right hook. There are many ways to do this, some flashier than others, but the common factor in all hooks is that they pique readers’ curiosity. In essence, a hook is a question—either explicit or implicit. A hook is an indication that something is, or shortly will be, off-kilter in the story world. Something doesn’t quite make sense. There is a mystery afoot. Even before readers meet the protagonist and make that all-important bond of empathy, they can be hooked with the promise that something is amiss.

Dawna does this seamlessly with her opening line promising a “bad thing” will happen. This is not an uncommon approach, but the technique is subtly strengthened here by opening not with “a bad thing happened,” but with “before the bad thing happened.” It’s a little different from what we normally see, it allows the story background to be sketched in (giving us characters to care about before we get to the punchline), and it immediately raises dramatic tension.

2. Hook Readers With a Specific Character Voice

For me, the single biggest test for whether or not I’ll read on is the story’s voice. I want a story that sounds either interesting and/or beautiful. I don’t want a story that sounds like an automaton (an effect often symptomatic of too much telling) or like every other story I may have already browsed today.

Voice is one of the most crucial, but also often one of the most elusive elements of story. A solid voice is a composite emergent of multiple factors—all of which come down to word choice and point to authorial competence. Dawna shows competence with her narrator’s voice throughout the excerpt, something she signals from the very first line with the grammatically idiosyncratic “just us five Raessen kids.”

Note that it’s not enough to give your narrator idiosyncratic or slangy grammar. The more unique the syntax, the more convincing the entire weft of the text must be in order to convince readers it is authentic and not just an authorial affectation.

3. Hook Readers With Specific Names and Language

Every word choice offers you an opportunity to breathe life into your story. Make your word choices as specific as possible. Don’t say the kids played “games” when you can specify they played “chase or tag or hide-and-seek.”

Perhaps more overlooked is the opportunity your character names have to bring your story to life. The first tip is to name your characters, as early as possible, within the narrative. The second tip is to choose names that say something.

The sisters in this story could have been named Sarah and Anne; nobody would have thought twice about it. But how much more interesting are these characters because their names are Shone and Campanula? (Not to mention the delightful childishness of one sister outdoing the other by choosing the title “Queener.”)

4. Hook Readers With Specific But Subtle Symbolism and Foreshadowing

This early in the first chapter, readers are still trying to figure out what the story is about. Inserting subtle symbolism can work to both characterize the opening scene and hint at what will come.

Knowing Dawna’s story is dark fantasy adds portentous overtones to the children’s game of escaping “the evil fairy king by reading messages written in blood across egg yolks.” Whether this game is directly related to the subsequent conflict or not, it sets the stage for dark magic to come, and it does so in a way that is so pertinent to the introduction that the symbolism alone acts as foreshadowing—without drawing undue attention to itself. In the busyness of a first chapter, this kind of subtlety goes a long way.

5. Hook Readers With Specific Prose Techniques

When examining a first chapter to determine whether or not an author knows her stuff, the wordcraft itself is always one of the greatest indicators. There are many techniques that contribute to a solid prose style—everything from description, to word tricks like alliteration, to proper rhythm from sentence to sentence.

Dawna shows solid wordcraft throughout this excerpt. One particularly nice example that pulled me in deeper with the rhythmic promise inherent in good writing is the subtle repetition of names throughout the first paragraph:

…the Peter Liam Bob team against me and Shone. Odin wasn’t born yet. When everybody was getting along we’d play chase or tag or hide-and-seek, but just me and Shone, just the two of us, was the best. Queen Shone and Queener Campanula. We’d spin bits of fleece from the farmer’s sheep, play dress up and pretend we were trying to escape the evil fairy king by reading messages written in blood across egg yolks that we tossed back in triumph. When it was just me and Shone, we always won. Me and Shone were closer than quarter to nine.

This kind of repetition doesn’t always work, but when it does it creates a poetic solidity readers can lean into.

6. Hook Readers With Specific Setting Details

Setting is an important character in its own right—especially in the first chapter. As a reader, I want to be given details that help me see the story. I don’t want to be visualizing characters running around in a void. But this is tricky. Too often, writers info dump settings that—however beautifully written or sharply detailed—distract from the momentum of the hook.

The key to grounding setting in the beginning is to choose a few specific details that can be evoked seamlessly from the story’s existent action. Dawna does this throughout the excerpt in many subtle ways (starting with the narrator’s country accent, which hints at where she’s from). She waits until the second paragraph to offer a swift but specific setting description, then moves on.

7. Hook Readers With Specific Follow-Up Hooks

The hook question that opens your story may remain unanswered until the very end of the story. But it may also be answered or partially answered just a few paragraphs later. In either case, the initial hook won’t be able to sustain reader interest indefinitely. It will need to be followed up by many more small hook questions throughout the entire story.

Here, Dawna doesn’t stretch readers’ patience past the fourth paragraph before both answering the initial question—and then deepening the mystery. We find out that the “bad thing” teased in the first line is the narrator’s beloved sister going missing. But the mystery around her disappearance only raises more questions—as well as signaling to readers what this story’s conflict will likely be about.

8. Hook Readers With Specific Descriptive Details

There are whole books that are entrancing not so much for their tight plots or deep characters, but for their beautiful prose. Appropriate beautiful prose never goes amiss is upping your story’s value. But the word choices, timing, and frequency must be apt for your specific story.

When Dawna ended the paragraph about Shone’s disappearance with the quietly and darkly beautiful phrase “white petals on black water,” she really grabbed me. Interesting characters—check. Mysterious hook—check. Appropriately beautiful word choices—check.

9. Hook Readers With Specific Characterization

One of the most difficult challenges for any first chapter is evoking a character readers can care about, but doing it quickly enough that it doesn’t slow down the momentum or feel like an info dump.

Dawna does this beautifully in characterizing a character who isn’t even present onstage—the missing Shone. In less than a sentence, she creates in readers an ache of the tragedy the narrator feels over her lost sister. She does this entirely through specific word choices such as describing Shone as a “bright light with skin on it.”

10. Hook Readers With Specific Showing Details

Specificity is the essence of proper showing (versus the inevitable generality of telling). Dawna could easily have explained the aftermath of Shone’s disappearance by saying her mother “went crazy.” Instead, she shows readers what happened by describing the mother’s specific actions. (This is in contrast with what is, in my opinion, one of the weaker phrases in the excerpt, when the narrator tells readers “my head felt like it was going to explode.”)

***

Learning how to choose the most specific and appropriate words for your story can make all the difference in helping you write a better first chapter. My thanks to Dawna for sharing her wonderful excerpt, and my best wishes for her story’s success. Stay tuned for more analysis posts in the future!

You can find previous excerpt analyses linked below:

5 Ways to Successfully Start a Book With a Dream

How to Use Paragraph Breaks to Guide the Reader’s Experience

8 Quick Tips for Show, Don’t Tell

4 Ways to Write Gripping Internal Narrative

10 Ways to Write Excellent Dialogue

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is your biggest challenge right now in figuring out how to write a better first chapter? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/write-a-better-first-chapter.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post Critique: 10 Ways to Write a Better First Chapter Using Specific Word Choices appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

December 2, 2019

17 Eco-Friendly Gifts for Writers This Christmas

If you’re like me, you may have already spent a lot of time this year searching “eco-friendly gifts for writers” or “eco-friendly gifts for book lovers.” If you found the available suggestions a little wanting, never fear. This year, I have a roundup of fun suggestions for writing- and book-themed gifts that are also mindful and eco-friendly.

If you’re like me, you may have already spent a lot of time this year searching “eco-friendly gifts for writers” or “eco-friendly gifts for book lovers.” If you found the available suggestions a little wanting, never fear. This year, I have a roundup of fun suggestions for writing- and book-themed gifts that are also mindful and eco-friendly.

One of my favorite parts of Christmas is buying meaningful gifts for the loved ones in my life. But one of the most challenging parts of Christmas shopping is keeping it in line with my personal desire to make low-waste and eco-friendly choices.

Before we get down to the good stuff of the actual gift ideas, here are my top tips for responsible shopping and gifting over the holidays:

1. Buy Secondhand

These days, you can find all kinds of top-quality stuff without needing to buy new. Not only can you save a few bucks by shopping Goodwill, eBay, ThredUp, thrift stores, and vintage stores, you can also give new life to resources that are already in play. Almost half the gifts I chose for others this year were purchased secondhand. If you plan ahead, you can shop garage sales all year long to find unique items.

2. Shop Upcycled, Handmade, and DIY

Upcycled items are repurposed from already existing resources—so you get the best of both the new and used worlds. Mindfully-created handmade items from shops on Etsy and Amazon Handmade are usually more eco-friendly (but not always, so read the specs). Of course, if you make something yourself, you have total control over the materials you use and where you source them.

3. Choose Experiences Instead of Items

Experiences are hard to wrap but often some of the best gifts you can give. Paying someone’s way to a writer’s retreat, class, group, or conference can be a huge gift—no wrapping required.

4. Buy Digital

Although digital resources aren’t without their own footprint, they are usually a greener alternative. Consider buying e-books, audio books, courses, or digital software (like my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software).

Get the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software.

5. Search for Eco-Friendly Materials and Ethical Companies

When buying new, try to find natural materials that are ethically sourced. Linen and wool are better than synthetic fibers and bamboo and cork are better than plastic.

6. Buy Things People Will Actually Use

Avoid gags and throwaway gifts that only last the day (I admit I’ve been terrible about this in the past). Try to be realistic about whether or not the recipient will actually use what you’re giving them. Buy the best quality possible so they can reuse the gift for years to come rather than needing to replace it shortly down the line. Most of the gifts I’m going to suggest are intended to be fun and useful but only for the right person. Not everyone will need or want these things. (It’s worthwhile to apply this criteria to your own wish lists as well. Sure, a new mug or tote is always fun. But if you already own useful editions of these things, why not stick with them until they’ve worn out their usefulness?)

7. Watch the Wrapping

I love wrapping paper. It’s one of the prettiest parts of Christmas decoration. I have rolls of it left in my own closet that I’m trying to use up. But it’s worth thinking about more sustainable ways to package gifts than in paper that will be admired for a month (at most) and then trashed.

Last month, I shared my thoughts on creating a zero-waste office. Pretty much all the products I suggested in that post would make great gifts or stocking stuffers for the fellow writers in your life. (These highlighter pencils were a particularly popular suggestion.)

17 Eco-Friendly Gifts for Writers

1. Plantable Graphite Pencils With Inspirational Quotes

2. Organic Cotton Book Tote (Featuring The Little Prince)

Green Gifter Tip: The average plastic shopping bag is used for something like 15 minutes before spending the rest of its (very long) life in the landfill. Give your writer friends (or yourself) the gift of an endlessly reusable shopping bag or book tote that shows off a unique literary style!

3. Organic Cotton Canvas Tote Bag,”Write (Blank), Edit (Blank)”

4. Walnut Wood Book Page Holder

5. Upcycled Book Letter Art

6. Cotton Tea Towel – “Write Your Own Story”

Eco-Gifter Tip: Most kitchen clean-up can be executed just as easily with a reusable towel as with a trashable paper towel. Plus, it can double as statement-making decor.

7. Edgar Allan Poe Lunchbox

Green Gifter Tip: Replace paper lunch bags with a sassy retro lunchbox. (Or find a stainless steel tiffin that can double as a take-out container.)

8. Upcycled Unicorn Anatomy Poster

9. Books Travel Mug

Green Gifter Tip: Bring Your Own Cup (BYOC—it’s a thing!) to the coffee shop instead of drinking from a throwaway cup. Check with your local coffee shop; some, like Starbucks, offer discounts when you BYOC.

10. Book Lover Ceramic Travel Mug

11. Recycled Decomposition Notebook

Green Gifter Tip: Buying recycled paper when possible is an easy way to one-up your personal sustainability game.

12. Upcycled Spoon Bookmark – “Fell Asleep Here”

13. Upcycled Typewriter Key Earrings

14. Cotton Typing Gloves – “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou

15. Cotton Typewriter Napkins

Green Gifter Tip: Cotton napkins do the job just as well as paper napkins—and they can be reused endlessly.

16. Stainless Steel Water Bottle – The Great Gatsby

Green Gifter Tip: If you’re wanting to switch over to a more sustainable lifestyle, this is probably the top (and easiest) step. Instead of drinking bottled water, bring your own. You can filter it easily by dropping in a few charcoal filters.

17. Upcycled Movie Reel Clock

Bonus Christmas Gifts for Writers: Writing Books

Don’t forget about books! Secondhand books and e-books are always eco-friendly choices, and even brand-new books have the advantage of being made from good ol’ biodegradable and recyclable paper.

For ideas, you can check out my full list of Recommended Reading for Writers, as well as my own series of writing books below. Merry Christmas, everyone!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What eco-friendly gifts for writers have you added to your Christmas list? Tell me in the comments!

The post 17 Eco-Friendly Gifts for Writers This Christmas appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 29, 2019

Black Friday Special: 25% off the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software

This Black Friday weekend, you can use the code OUTLINE to grab my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software at a special holiday discount of 25% its normal price of $40.

Start Outlining Your Best Book Today

As a reader of my blog, you can access a special 25% discount code for my Outlining Your Novel Workbook software. Just enter the code OUTLINE at checkout. This deal will only be available Black Friday through Cyber Monday. Enjoy!

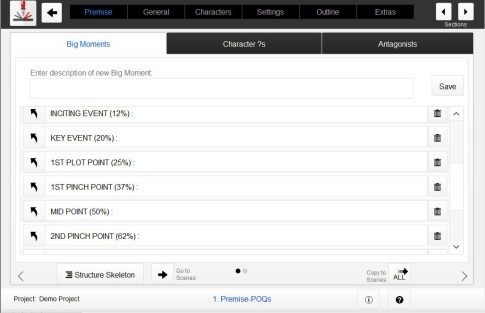

How Can the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software Help You?

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook computer program is a brainstorming tool for writers. It is designed to guide you in discovering the brilliant possibilities in your ideas, so you can identify those best suited to creating a solid story that will both entertain and move your readers.

The software provides an easy fill-in-the-blanks format that will guide you through every step of the process. Creating your own outline is as simple as starting on the first screen, using the prompts and lessons to work through your story in the most intuitive way, and clicking through the tabs at the top to access important sections.

The Outlining Your Novel Workbook program makes outlining a fun and empowering process that will help you write your best story.

Features:

• Outline – Create a story with a solid Three-Act plot structure and perfect scene structure.

• Premise – Easy fill-in-the-blanks give you a perfect elevator pitch every time.

• General Sketches – Brainstorm the big picture of your scene list, character arcs, and theme.

• Character – Get to know your characters with an extensive character interview, featuring 100+ questions.

• Settings – Keep track of your settings, explore your best options, and answer helpful world-building questions.

• Fun Extras – Import your mind maps and world maps, keep track of your story’s timeline, cast your characters, and create story-specific musical playlists.

Here’s Your Coupon Code:

Don’t forget to use the code below to get 25% off your order of the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software:

OUTLINE

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

More Black Friday Deals:

You can find dozens more Black Friday deals for writers, including discounts off ProWritingAid and One Stop for Writers, by checking out this post: Favorite Black Friday Offers for Writers.

The post Black Friday Special: 25% off the Outlining Your Novel Workbook Software appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 25, 2019

How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Any Type of Story

Here’s how to choose the right antagonist for your story. You know “If I Didn’t Have You”—that song John Goodman and Billy Crystal belt out at the end of Monsters, Inc.? It’s this total bromance duet about the undying friendship of our two favorite monsters. But pretty much every lyric in there could also be crooned in gratitude by any good protagonist to any good antagonist:

Here’s how to choose the right antagonist for your story. You know “If I Didn’t Have You”—that song John Goodman and Billy Crystal belt out at the end of Monsters, Inc.? It’s this total bromance duet about the undying friendship of our two favorite monsters. But pretty much every lyric in there could also be crooned in gratitude by any good protagonist to any good antagonist:

I wouldn’t be nothing

If I didn’t have you

I wouldn’t know where to go

Wouldn’t know what to do

The antagonist may not be the big-money reason readers pick up a book or audiences flock to a theater. But he is ultimately the reason the protagonist either a) has a reason to stop wasting her life eating potato chips on the couch or b) doesn’t just coast through every obstacle with boring ease.

So we gotta give our antagonists some love. For starters, this means crafting them with as much nuance and care as what we lavish on our protagonists. If you stand up an amazingly dimensional protagonist against a cardboard antagonist, it’s always going to show.

The antagonist is the flint to the protagonist’s steel, the immovable object to the protagonist’s unstoppable force, the destiny to the protagonist’s free choice. Apart, they may not even be that interesting. Together—whammo! Can anyone say Inciting Event?

But it’s not enough to throw a bad guy and a good guy in the ring together. It’s not even enough to dream up an antagonist who just happens to be opposed to your protagonist’s every move (although that’s way better). It’s also worth noting that giving the devil his due doesn’t mean giving him the spotlight. I feel like there’s an unfortunate trend these days toward overemphasizing the antagonist at the expense of the protagonist. Enemies-turned-antiheroes and redemptive arcs are all fine and well, but not at the expense of narrative integrity or, for that matter, proper use of character-audience identification.

The only way to get your protagonist and antagonist to sing in harmony is to craft them that way from the beginning. The harmonics in any story arise out of theme. Just as your protagonist must be carefully chosen/crafted to suit your theme (or vice versa), so too your antagonist.

There are many ways to approach this union of protagonist-antagonist-theme (which, ultimately, is just another representation of that trifecta of character-plot-theme). One of the best ways is to take cues from your protagonist’s character arc. If you know how your most important character will be thematically impacted by the events of the plot, then you will be able to holistically figure out how to choose the right antagonist, one who both impacts and is impacted by your protagonist’s changes.

5 Different Types of Antagonists

Usually, I prefer the more inclusive term “antagonistic force” since it doesn’t assume the antagonist is human. Today, we’ll be talking mostly about antagonists who are characters in their own right so I’m mostly using the term “antagonist,” but don’t forget the same principles apply, if only symbolically, even in stories that don’t offer a personified antagonist. Before we start exploring how your protagonist’s and antagonist’s character arcs might thematically influence each other, let’s first take a look at some broad categories of antagonistic forces.

1. Protagonist vs. Society

Here we have a protagonist facing off against not just an individual, but an entire society—usually one that is corrupt in some way. Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (not to be confused with H.G. Wells’s book of the same title) and Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games represent this genre. However, even in stories of this epic scope, it’s usually best to personify the society in either a specific antagonist (Collins’s President Snow) or at least a series of symbolic characters (as in Invisible Man).

2. Protagonist vs. Nature

This would be any story in which the protagonist is trying to accomplish something (usually survival) in the face of weather (e.g., a hurricane), an unforgiving setting (e.g., a desert), an animal (e.g., predators), illness (e.g., epidemics—or, technically, zombies), etc. These stories may also introduce a human foe, but usually in the role of contagonist rather than antagonist. More often, the protagonist’s personal and thematic arc will interact with the faceless antagonistic force in a more symbolic manner—with the force of nature offering an externalization of the character’s inner battle.

3. Protagonist vs. Self

Very few plots are literally about the Protagonist vs. Self. Even in stories in which the character’s internal conflict is the central focus, the conflict will also be externalized in some symbolic way. It could be the protagonist literally gets in his own way by self-destructively throwing up obstacles to his plot goal. But it could also be the struggle against self is represented on a grander scale by having it mirror a larger, faceless conflict (as in Protagonist vs. Nature or even Society) and/or that the protagonist’s inner demons are metaphorically represented by the various people he meets throughout the narrative.

4. Protagonist vs. Protagonist

Most of the time when we hear “protagonist” and “antagonist,” we think “good guy” and “bad guy.” But this isn’t actually accurate, since these terms are meant to indicate narrative function rather than moral alignment (it’s totally possible to have your protagonist be the most evil person in the story and your antagonist be the most angelic). This is most obvious in stories in which the antagonist is more of a co-protagonist. What this really means is that each protagonist is going to be creating the obstacles to the other’s plot goals. These stories are often great for exploring morally complicated themes. They’re also customary in romances, in which the central conflict is relational with both characters being equally important in the climactic decision to be (or not to be) together.

5. Protagonist vs. Antagonist

Finally, we have the classic setup of protagonist vs. antagonist. In this type of narrative, the protagonist represents the structural throughline—and, as such, the character with whom audiences are intended to identify. The antagonist is the person who stands in opposition to the protagonist after their goals turn out to be mutually exclusive. Almost always, the antagonist’s goals will predate the protagonist’s. The protagonist is the one who, for whatever reason, decides she must react to the antagonist, either to stop the antagonist from doing something or because the antagonist is the one trying to stop her.

The 3 Main Types of Story—and How to Choose the Right Antagonist Arc for Each

I’ve talked before about how you can view your entire plot as essentially one big thematic metaphor. But this only works if the antagonist is properly aligned within the theme as well as the plot. On a really abstract and zoomed-out level, you can think of your antagonist as the plot. Because he creates the obstacles to the protagonist’s plot goals, he is what creates the conflict—and the conflict is the plot.

What this means when we zoom back in is that your antagonist’s motives and actions must not just directly impact your protagonist in the plot, they must also impact your protagonist in the theme. Specifically, you want the antagonist to present a direct challenge to your protagonist’s thematic orientation. If your protagonist represents or will come to represent the thematic Truth, then your antagonist should be the thematic avatar of the Lie—and vice versa.

No one in the story should have a greater impact on your protagonist’s evolution from Lie to Truth (or Truth to Lie) than does your antagonist. This doesn’t mean the antagonist needs to sit down with the protag for an ideological or existential debate. It doesn’t even mean the two need to ever be physically present in the same room. But it does mean the protagonist’s character arc is catalyzed by the obstacles presented by the antagonist in the external plot.

Although there are myriad variations of character arc your protagonist might undertake in your story, we can group those variations within three broad categories. These categories, in turn, will offer guidance about what role your antagonist should play in both your story’s plot and, particularly, its theme.

1. If Your Protagonist Is Following a Positive-Change Arc…

In a Positive-Change Arc story, the protagonist will start out in a negative relationship to the thematic Truth. This means he will begin the story by resisting or outright rejecting the Truth in favor of an opposing Lie. As a direct result of the events created by the main conflict, the protagonist will be forced to confront the limitations of this Lie and start moving into an understanding and embrace of the Truth.

In response, the antagonist may take one of two thematic stances.

The first possibility will begin with an antagonist who also believes and represents the Lie. It may be exactly the same Lie the protagonist starts out with. Or it may be a “bigger” version of the Lie, to which the protagonist is initially attracted. Because of their similar alignment with the Lie, it may be the protagonist and antagonist start out on the same side of the conflict. Even if they represent differing goals, the protagonist will still be attracted to and feel an affinity to the antagonist—since, at least in their belief in the Lie, they are alike.

However, unlike the protagonist, who begins to see through the Lie in favor of the Truth, the antagonist will not change. By the story’s end, he will come to represent the full consequences of following the Lie and will probably be overcome by the protagonist’s new Truth.

The second possibility offers an antagonist who aligns with the Truth, opposes the protagonist’s Lie from the beginning, and eventually “breaks” the protagonist with the Truth as a way of helping her recognize that the Lie is unsustainable. This type of antagonist is less likely to be morally evil or ambiguous. Often, this type of antagonist is an important relationship character, such as the love interest in a romance. In order for the protagonist to be with the antagonist, the protagonist must overcome her destructive Lie-based mindset.

2. If Your Protagonist Is Following a Flat Arc…

In a Flat-Arc story, the protagonist does not change his primary thematic viewpoint. Thematically, he represents the Truth (or, less often and always tragically, the Lie). Because of his own powerful alignment to the theme, he will inspire change in other important characters by the end of the story. He will use his alignment with the theme to advance his plot goals.

Stories such as this, in which the protagonist does not personally change, usually present the thematic argument via opposing ideologies. As such, the antagonist will usually be equally resilient in representing the opposite side of the argument—the Lie if the protagonist represents the Truth, or vice versa.

In these stories, it is possible for the antagonist to undergo a change arc (either Positive or Negative) as a result of interacting with the protagonist. However, this can sometimes put the antagonist is a role of comparative weakness next to an immovable protagonist. A more powerful thematic argument (and thus story) usually arises when the antagonist is designed to represent the opposite, and equally forceful, side of the theme.

3. If Your Protagonist is Following a Negative-Change Arc…

Negative-Change Arcs offer more variation. The protagonist may start out in either a positive or negative relationship with the thematic Truth. As in a Positive-Arc story, she may start out already believing the Lie—in which case she will either arc into believing a disillusioning Truth or devolve into an even darker version of the Lie. She may also start out believing in the Truth, only to fall away into a Lie.

In these types of story, the antagonist may steadfastly represent the Truth, which will be futilely pitted against the protagonist’s Lie in a battle of ideologies. Or he will represent the Lie and serve to seduce the protagonist to her ultimate demise.

***

Both in creating plot and in creating theme, your two most important characters will always be your protagonist and antagonist. By figuring out how to choose the right antagonist, one whose plot actions are motivated by a thematically-appropriate relationship to the story’s posited Truth and Lie, you will all but guarantee a solid narrative. More than that, if you’re willing to deepen your understanding of your antagonist’s relationship to the theme, you can add even more nuance by mirroring your protagonist’s character arc with an equally powerful arc from a different perspective.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you choose the right antagonist for your story? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/choosing-the-right-antagonist.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Any Type of Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 18, 2019

How to Overcome Fear as a Writer and Embrace Your Profound Courage

Long ago, someone gave me a birthday card that said “Fearless.” For many years, I tacked it on my bulletin board above my desk. Even now, it’s one of the few cards I’ve ever saved. I kept it because while a part of me resonated with the idea that I might be fearless, the rest of me just yearned to be—because I knew I wasn’t. I knew I had to learn to overcome fear as a writer or a person.

Long ago, someone gave me a birthday card that said “Fearless.” For many years, I tacked it on my bulletin board above my desk. Even now, it’s one of the few cards I’ve ever saved. I kept it because while a part of me resonated with the idea that I might be fearless, the rest of me just yearned to be—because I knew I wasn’t. I knew I had to learn to overcome fear as a writer or a person.

I look back on my life and realize that my fears, although often suppressed, were always present. Someone once asked me in an interview what I thought made me productive and focused, and I knew the answer was that I was running, always running, from the fears that I wouldn’t measure up.

So in some ways, it’s a humorous irony that I became a writer. Being a writer means putting yourself constantly into the storming heart of the most frightening parts of existence.

Writers can’t hide. If we try to avoid authenticity and vulnerability, our writing inevitably fails—and that is a devastation in itself. To choose this life is to choose to stand naked—before ourselves and, sooner or later, before the whole world.

Eventually, we must put everything out there be judged—from our punctuation skills to our very sanity. The ego is constantly battered, because of course we never measure up. The best thing we’ve ever written isn’t perfect. It’s full of holes for someone to point out. Even more poignant, if we’re really honest, is the truth that we don’t even need someone to point out the holes. We know them all. We know some scenes are boring. We know our characters are occasionally representatives of ourselves at our most whiny and unlikable. We know our logic and even our philosophy is sometimes without defense.

If we publish, we know we may lose more than money. We may lose face. Even if we’re lucky, we know we’ll get negative reviews—sometimes evisceratingly bad reviews. We know people are likely to ignore us as the utterly ignorable little people we are. And if they do notice, we know some of them will take it upon themselves to call into question our very humanity.

The stories and the characters that are so precious to us—and so symbolic of the precious inside parts of our own experiences—will be logically and sometimes brutally torn apart by others. And more often than not, when we read their words, the part of us that bleeds the worst is the part that knows there’s truth in what is being said.

Sometimes we want to give up. Sometimes we do. Sometimes publishing one more book, even one more post—putting one more piece of ourselves out there to be judged—seems too hard. Sometimes just the writing itself is too hard—the discipline of putting one word after another, the rawness of facing our own inadequacies on every page.

But we keep writing.

The fact that we often cannot help but keep writing does not lessen the truth that in continuing to write, we are engaging in a tremendous act of courage. Do not underestimate this. Ever.

Writing as Both Fearsome Compulsion and Courageous Choice

Cynthia Ozick gives us this beautiful statement:

If we had to say what writing is, we would have to define it essentially as an act of courage.

She’s also quoted as saying:

[Writing is] a kind of hallucinatory madness. You will do it no matter what. You can’t not do it.

As writers everywhere can attest, there’s much truth in that. Why else would we throw ourselves into the breach time and time again?

But I daresay the words we continue to brandish in the face of our fears do not always come so compulsively. It’s true that sometimes we are brave without thinking about it. We write, we publish, we wait for a response—without overthinking it. But sometimes it’s not so easy. Sometimes creation is John Hammond’s “act of sheer will.” Sometimes it is a deliberate howl into the darkness of our own fears.

Perhaps that’s the point. Putting the vulnerable and untested parts ourselves into the exposed irrevocability of print may be one of the most frightening things a human being can do, but it is also one of most fundamental and powerful ways in we which we fight to overcome our fright.

In truth, I’m thinking about all this today because I’ve been pondering my own reaction to a negative review. It’s a review of a story I wrote long, long ago, when I was barely an adult, when I was another person entirely, back when I was still learning so many basics of the craft. I wouldn’t write the book again, not in the same way. The person I am now would write it so that many of the things the reviewer disliked would have been corrected. And probably that is why the review made an impact on me at all; it is always the bad reviews I agree with that hurt the most.

As is always the case when a negative review hits home, there is a part of me that is scared to try again. It’s not a wholly reasonable part of me. It’s that sensitive, ego-driven part that feels as if this judgment of old, old words is somehow a judgment of my worth as a person. It’s also the part of me that loves that old story, in all its comparative shabbiness and naïvety, and that now feels as if that precious part of my life should have been kept shielded and private where it could not be scorned by others to whom I wasn’t skilled enough to communicate clearly.

I hear the words of that review—and others before it—and I am afraid. I know I haven’t yet understood how to remedy all the flaws I know about (never mind those I don’t). I know that when I come to my desk tonight, what I write won’t be perfect. I know that despite all efforts, I’m going to do it again—going to put myself right back in the crossfire. Ultimately it isn’t the criticism of others I fear, but the echo of agreement from within myself.

And yet, when it does come time tonight for me to write, I will. There will be a part of me that’s afraid—afraid of making the same mistakes, afraid both that I might shame myself with an exposure of my inner truths and also that I will betray those truths because my skill isn’t—and never will be—capable of conveying to others my own depth of experience. But I will write.

I will write, not just because of Ozick’s “hallucinatory madness,” but because I choose to write. I choose to keep going. I cannot choose to be fearless. But I can choose to be brave. And so can you.

5 Ways to Overcome Fear as a Writer

Sooner or later, fear (and it’s evil twin doubt) are feelings all writers experience. When you discover yourself feeling fear, take it as a sign that you’re doing something right. I used to tell myself to “write scared.” If I wasn’t pushing myself just slightly to the brink of discomfort, then I knew I was probably just settling, on one level or another.

So write scared. And as those fears arise—sometimes just little niggles and sometimes life-threatening monsters—try the following five ideas to help you use, live with, and perhaps overcome fear as a writer.

1. Feel the Hurt of What Scares You

For some people, this first step may not only be a no-brainer, but part of the problem. Some people have no difficulty accessing, feeling, and identifying their emotions. In fact, for some people the biggest problem is indulging too much in those emotions. But for me, as someone who has struggled with emotional repression, my first step is to make sure I am feeling the hurt or the fear.

Instead of immediately stuffing it or rationalizing it when it comes up, I try to notice it, look it square in the face, and literally feel whatever sensations are showing up in my body. My go-to defense is usually rationalizing my way around an unpleasant feeling (e.g., “I shouldn’t be upset; I agree with that person after all” or “who cares if one person didn’t like the book when I know lots of others do like it?”). Rationalizations are all fine and well in their place, but they don’t substitute for emotional honesty.

2. Choose Humility Over Defensiveness

Fear is a response that occurs either because something hurt us or because experience tells us something could hurt us in the future. When we are hurt because a critique partner or family member criticizes a raw story, the experience is often compounded by our fears of what it means both about us as a person (“I’m a terrible writer!”) or the future of our dreams (“this story is doomed!”). In these situations, it’s incredibly easy (and often somewhat gratifying) to become defensive—sometimes to the point of turning the criticism right back on the other person.

More often than not, defensiveness is counter-productive. Unless we’re masters of self-delusion, our retorts aren’t likely to make us feel any better and they may indeed block us from making necessary corrections. Although humility should never become an excuse to let others dictate your view of yourself, your work, and your world, it is an invaluable tool for refining not just your understanding of story, but your understanding of life and yourself in it.

After you’ve given yourself some time to feel your hurt without getting defensive, take another moment to ask if there’s a core of truth to what the other person is suggesting. They may be dead wrong. But they may also be offering the key to your next great discovery—if only you have the courage to not just face your ego’s fear but walk on through it.

3. Embrace Your Own Wonderful Bravery

For many years, I have kept handy a quote from journalist Bill Stout:

Whether or not you write well, write bravely.

I do not always write well. That I write better today than I did yesterday, that perhaps my most recent novel is better than my first is in no way a guarantee that what I write now will be good enough to matter to anyone but me.

But I do write with all the bravery and honesty I can muster. This is a truth I can claim—and be proud of.

Last night, I took a walk under the November moon to process the hurt feelings and inevitable flash of fear that resulted from that negative review. There was, at first, the familiar threat from the wounded and scared part of myself: You don’t ever have to share your writing with anyone ever again!

From that comes a little flicker of false security, but it is quickly followed by the more mature and wise voice that says, No, of course, you will write again. And how brave you are to do so, my darling. How brave you are.

And with that, I am at peace again—because I know I’d rather be brave and get hurt than be a coward in safety.

When you find yourself most afraid—when your insecurities are roaring their loudest—don’t forget that you are brave. Your writing may say truths about you that you don’t always like to face. But the one truth it always says is that you are a lionheart. Roar that back into the face of whatever scares you most.

4. Follow the Fear

Take your bravery in your hand and turn back around to face your fears full on. Claim “write scared” as your mantra. The very fact that you are afraid of what your writing says about you—and what others, in their turn, say about that, is something you can write about. They are opportunities to learn and to grow. More than likely, your fears are red arrows pointing straight at the thing you most need to work on.

Fear exists to protect us. So look at what you’re afraid of and why. You may have to dig past the surface, but what you find may well be something that is causing you real pain or holding you back in some vital way. Learn to hear what your fear is telling you.

Whenever you start feeling too safe or complacent, look around for something that scares you—whether it’s giving your story back to a critique partner whose honest feedback hurt you, or writing a scene that hits too close to home, or being honest about something that’s hard for you to admit even to yourself. Lean into the fear. Conquer it, and it can no longer threaten you. There are still so many things I’m afraid of—in both life and writing—but there are also so many things that used to scare me but that now I have all but forgotten.

5. Turn Your Fears Into Truths

Finally, remember that everything you feel deeply in your own life is grist for the mill. Humans have this innate hubristic idea that we know so much about life–and I daresay writers are the worst offenders! But there’s knowing things and there’s knowing things. The more we know, gleaned from the depths of our own growing awareness of our lives, the more we can write with authenticity.

The person who left me that negative-but-ultimately-inspiring review didn’t know it, but much of what they criticized in that old book was due as much to my inexperience in life as any inexperience as a writer. They couldn’t know that, but I know it. I know my former self wrote with all the honesty and understanding she had. My current self tries to do that too but with the benefit of a decade’s worth of added experience—part of which includes the reflection brought about by a book review that hurt mostly because it was unwittingly a critique of that former self.

The only way writers can share words and stories of awareness and honesty is if we are doing our best to be aware and honest with ourselves. As our perspectives simultaneously refine and broaden, our stories inevitably become better. There’s no fear in that idea—just delightful hope.

***

That writing is often scary is actually one of the most exciting things about it. Some people jump off cliffs, some people ride bulls, and some people write. After all, as the T-shirt says,

If you’re not living on the edge, then you’re taking up too much room.

By that logic, I don’t think there’s a writer alive who’s taking up too much room. Put your hand over your heart, feel that fear in your chest, breathe deep, and jump. Perhaps at the end of the day, it’s the thrill of conquering our fears that makes the words worth writing and life worth living.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How have you overcome fear as a writer? Tell me in the comments!

http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/kmweiland.com/podcast/overcome-fear-as-a-writer.mp3

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in iTunes).

The post How to Overcome Fear as a Writer and Embrace Your Profound Courage appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

November 15, 2019

5 Secrets of Story Structure Audio Book

I wanted to take a quick minute to let you know that there is now an audio book version of 5 Secrets of Story Structure, narrated once again by the lovely Sonja Field.

I wanted to take a quick minute to let you know that there is now an audio book version of 5 Secrets of Story Structure, narrated once again by the lovely Sonja Field.

I wrote 5 Secrets as kind of an unofficial sequel to Structuring Your Novel. You can think of 5 Secrets as a slightly more advanced look at story structure (although I definitely recommend starting with Structuring Your Novel to get the big picture first).

It’s a short book, just a little over an hour on audio. You can grab it off Amazon for just $6.95, and if you’re not an Audible member yet you can even grab it for free by signing up!

About the Audio Book

If you’ve read all the books on story structure and concluded there has to be more to it than just three acts and a couple of plot points, then you’re absolutely right! It’s time to notch up your writing education from “basic” to “black belt.” Learn five “secret” techniques of advanced story structure.

Structuring Your Novel showed writers how to use a strong three-act structure to build a story with the greatest possible impact on readers. Now it’s time to take that knowledge to the next level.

In this supplemental book, you’ll learn:

Why the Inciting Event isn’t what you’ve always thought it is

What your Key Event is and how to stop putting it in the wrong scene

How to identify your Pinch Points—and why they can make the middle of your book easier to write

How to create the perfect Moment of Truth to move your protagonist from reaction to action

How to ace your story’s Climactic Moment every single time

And much more!

By the time you’ve finished this quick read, you’ll know more about story structure than the vast majority of aspiring authors will ever know—and you’ll be ready to write an amazing novel that stands above the crowd.

The post 5 Secrets of Story Structure Audio Book appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.