Oxford University Press's Blog, page 880

November 14, 2013

Jazz, the original cool

Jazz is a genre of music that is rich in history and cultural influences. When you think of jazz music, a massive list of other phenomenal artists may come to mind including Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Billie Holiday. In the nineteenth century, the music was birthed from ragtime and evolved into the blues, followed by swing Music and jazz, creating genres of music influenced by a myriad of styles and sounds. Today jazz is a musical phenomenon enjoyed by a legion of fans worldwide. Test your knowledge of the history of jazz with these questions compiled from Mervyn Cooke’s The Chronicle of Jazz.

Jazz is a genre of music that is rich in history and cultural influences. When you think of jazz music, a massive list of other phenomenal artists may come to mind including Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Billie Holiday. In the nineteenth century, the music was birthed from ragtime and evolved into the blues, followed by swing Music and jazz, creating genres of music influenced by a myriad of styles and sounds. Today jazz is a musical phenomenon enjoyed by a legion of fans worldwide. Test your knowledge of the history of jazz with these questions compiled from Mervyn Cooke’s The Chronicle of Jazz.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Dr. Mervyn Cooke is Professor of Music at the University of Nottingham and has published extensively on the history of jazz, film music, and the music of Benjamin Britten. His most recent books include The Chronicle of Jazz, The Cambridge Companion to Jazz, The Hollywood Film Music Reader, The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera and Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters of Benjamin Britten.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post Jazz, the original cool appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImages of jazz through the twentieth centuryJohann van Beethoven’s last hurrah“God Bless America” in war and peace

Related StoriesImages of jazz through the twentieth centuryJohann van Beethoven’s last hurrah“God Bless America” in war and peace

Picturing printing

No visit to the Sheldonian Theatre would be complete without craning your neck to admire Robert Streater’s painted ceiling. Entitled Truth Descending upon the Arts and Sciences and comprising thirty-two panels, the painting was completed in Whitehall in 1668-9 and shipped to Oxford by barge. We don’t know the terms of the commission but Streater’s personification of Truth triumphing over Envy, Rapine, and Ignorance fitted well with a University looking to reassert its cultural ambitions in the aftermath of the Civil Wars and Interregnum. Not surprisingly, the ceiling became a spectacle in its own right from the moment that the Theatre was completed. The Oxford poet Robert Whitehall used verse to explain its iconography in Urania, or a Description of the Painting of the Top of the Theater at Oxon, as the Artist lay’d his Design, published in London in 1669. A broadside, A Discription of the Painting of the Theater in Oxford (1673), may well have been sold to visitors. The ceiling was also described in Robert Plot’s The Natural History of Oxford-shire, published by the University in 1677, and regularly featured in tourist guides in the eighteenth century and beyond.

Sheldonian Theatre ceiling shows Truth descending upon the Arts and Sciences to expel ignorance from the University

Streater evidently knew that the Theatre was to house the University’s printing presses as he included the figure of ‘Printing’ in among the personifications of various virtues and vices. Locating ‘Printing’ on the ceiling, however, is far from straightforward, which perhaps explains why so few people know of its existence, and why it has never been mentioned, let alone reproduced, in any previous history of university printing at Oxford. In the north-north-west corner of the ceiling is a bare-breasted woman holding a series of curious-looking objects. Whitehall’s verse explains:

Printing is with a Box of letters, and

A Form that’s ready set ‘ith’ other hand:

Where lest the Printing-presse should vacant lie

Are several damp sheets hanging up to dry.

That Streater included printing at all amid a whirl of mythical personifications was a powerful statement about the role that university printing was expected to play in the cultural life of the nation. But what is also striking is how he chose to represent printing. He evidently knew the basic elements of the printing process — the ‘Box of letters’ is a case of printing type; set type has to be locked into a forme ready for printing; and the sheets of paper have to be dampened before the formes are printed — but even an experienced printer would have been hard-pressed to identify these objects as they are painted. To be fair, Streater had few if any precedents when it came to visually personifying printing: the only earlier example I know of Cesare Ripa’s influential Iconologia (1593) which shows ‘Stampa’ (printing) as a woman ‘in a white chequer’d Habit with the Letters of the Alphabet on it…to signifie the little Boxes for the Letters’, sitting next to a binders’ press. Even so, it is surprising to see no printed books.

Streater’s decision to represent the process of printing rather than its products may be in keeping with his own career as a painter, treading a fine line between artist and artisan. Nonetheless the mechanical nature of printing sits uneasily in a painting that is otherwise wholly allegorical, which perhaps explains why ‘Printing’ is tucked away behind the figures of Law and Rhetoric, why her face is turned away from the viewer, and why she holds both case and forme rather awkwardly. It is not too much of a leap to see here the enduring tension between learning and commerce, between intellectual aspiration and the pragmatics of publishing, that had been characteristic of scholarly publishing long before Streater painted that ceiling — and one that continues to this day.

Ian Gadd is Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University. He is editor of The History of Oxford University Press–Volume 1: From its beginnings to 1780.

To celebrate the publication of the first three volumes of The History of Oxford University Press on Thursday and University Press Week, we’re sharing various materials from our Archive and brief scholarly highlights from the work’s editors and contributors. With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Watch the silent film or learn about arguments over the first printing press in Oxford or when the Press began in our previous posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of the University of Oxford.

The post Picturing printing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen did Oxford University Press begin?Before Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing cityOxford University Press and the Making of a Book

Related StoriesWhen did Oxford University Press begin?Before Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing cityOxford University Press and the Making of a Book

Israel’s strategic nuclear doctrine: ambiguity versus openness

Israel’s nuclear posture is always closely held. This cautious stance would appear to make perfect sense. But is such secrecy actually in the long-term survival interests of the Jewish State? The answer should be based upon a very carefully reasoned assessment of all available options. Any useful loosening of Israeli nuclear ambiguity would need to be subtle, nuanced, more-or-less indirect, and codified in suitable military doctrine.

Strategic doctrine represents the indispensable framework from which any pragmatic Israeli nuclear policy of ambiguity or disclosure should be extrapolated. The vital importance of military doctrine lies not only in the way it can animate, unify, and optimize Israel’s military forces, but also in the efficient manner it can transmit desired “messages” to an enemy state or sub-state proxy. Understood in terms of Israel’s strategic nuclear policy, any indiscriminate, across-the-board ambiguity could undermine the country’s national security. This is because effective deterrence and defense could sometimes call for a military doctrine that is at least partially recognizable by certain adversary states, or even by particular insurgent/terrorist groups.

For Israel, ultimate military success must lie in credible deterrence, not in actual war-fighting. Understood in terms of ancient Chinese military thought offered by Sun-Tzu, in The Art of War, “Supreme excellence consists of breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.” There are occasions when too much secrecy can effectively degrade a country’s security.

Israel’s nuclear weapons must be oriented to deterrence ex ante, not to war fighting or revenge, ex post. Nuclear weapons can succeed only in their non-use. Once they have been used for battle, deterrence, by definition, will have failed. Once actually used, any traditional meanings of “victory,” especially if both sides are nuclear, are apt to become moot.

The Cold War is over, and Israel’s deterrence relationship to a potentially nuclear Iran is not really comparable to what had existed between the United States and the USSR. Still, there are Cold War deterrence lessons to be learned in the Jewish State. In essence, any unmodified continuance of total nuclear ambiguity could sometime cause a nuclearizing enemy state like Iran to underestimate Israel’s retaliatory capacity, or resolve.

Similar uncertainties surrounding components of Israel’s nuclear arsenal could lead enemy states to reach the same conclusion. In part, this is because Israel’s willingness to make good on threatened nuclear retaliation could be seen, widely perhaps, as inversely related to weapon system destructiveness. Ironically, therefore, if Israel’s nuclear weapons were believed to be too destructive, they might not deter.

A continuing policy of ambiguity could also cause an enemy state such as Iran to overestimate the first-strike vulnerability of Israel’s nuclear forces. In part, this could be the result of a too-complete silence concerning measures of protection deployed to safeguard Israeli nuclear weapons.

Or it could be the product of Israeli doctrinal opacity on the country’s defense potential, an absence of transparency that could be mistakenly understood, again, by certain enemy states, as an indication of inadequate Israeli Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD). Optimally, therefore, certain relevant strengths and capabilities of Arrow3 could soon need to be revealed.

Israel’s Chief of Staff Visits Paratrooper Exercise 2011. Photo by Israel Defense Forces. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

To deter (1) an enemy attack; or (2) a post-preemption retaliation against Israel, Jerusalem/Tel-Aviv must always prevent a rational aggressor, by threat of an unacceptably damaging retaliation or counter-retaliation, from deciding to strike. Here, national security would be sought by convincing the potential rational attacker that the costs of any considered attack will always exceed the expected benefits. Assuming that Israel’s state enemies value self-preservation most highly, and choose rationally between alternative options, they will always refrain from any attack on an Israel that is believed both willing and able to deliver an adequately destructive response.

Two factors must communicate such a belief. First, in terms of capability, there are two essential components: payload and delivery system. It must be clear to any prospective attacker that Israel’s firepower, and its means of delivering that firepower, are capable of inflicting unacceptable levels of destruction. This means that Israel’s retaliatory or counter-retaliatory forces must always appear sufficiently invulnerable to enemy first-strikes, and also aptly elusive to penetrate the prospective attacker’s active and civil defenses.

With Israel’s strategic nuclear forces and doctrine kept locked in the “basement,” enemy states could conclude, rightly or wrongly, that a first-strike attack or post-preemption reprisal would be cost-effective. But, were relevant Israeli doctrine made more plainly obvious to enemy states contemplating an attack — that Israel’s nuclear assets met both payload and delivery system objectives – Israel’s nuclear forces could then better serve their critically existential security functions.

The second factor of nuclear doctrine for Israel concerns willingness. How may Israel convince potential nuclear attackers that it possesses the resolve to deliver an appropriately destructive retaliation, and/or counter retaliation? Again, the answer to this question lies largely in doctrine, in Israel’s demonstrated strength of commitment to carry out such an attack, and in the nuclear ordnance that would presumably be available.

Here, too, continued ambiguity over nuclear doctrine could wrongfully create the impression of an unwilling Israel. Conversely, any doctrinal movement toward some as-yet-undetermined level of disclosure could heighten the impression that Israel is, in fact, willing to follow-through on its now explicit nuclear threats.

There are determinedly persuasive connections between an incrementally more “open” or disclosed strategic nuclear doctrine, and certain enemy state perceptions of Israeli nuclear deterrence. One such connection centers on the expected relation between greater openness, and the perceived vulnerability of Israeli strategic nuclear forces from preemptive destruction. Another such connection concerns the relation between greater openness, and the perceived capacity of Israel’s nuclear forces to reliably penetrate the offending state’s active defenses.

To be deterred by Israel, a newly-nuclear Iran would need to believe that (a critical number of) Israel’s retaliatory forces would survive any Iranian first-strike, and that these forces could not subsequently be stopped from hitting their pre-designated targets in Iran. Regarding the “presumed survivability” component of Iranian belief, possible sea-basing (submarines) by Israel could be an especially relevant case in point.

Carefully articulated, expanding doctrinal openness, or partial nuclear disclosure, could represent a distinctly rational option for Israel, at least to the extent that pertinent enemy states were made appropriately aware of Israel’s relevant nuclear capabilities. The operational benefits of any such expanding doctrinal openness would accrue from deliberate flows of information about more-or-less tangible matters of dispersion, multiplication, and hardening of its strategic nuclear weapon systems, and also about certain other technical features of these systems. Most importantly, doctrinally controlled and orderly flows of information could serve to remove any lingering enemy state doubts about Israel’s strategic nuclear force capabilities and intentions. Left unchallenged, however, such doubts could lethally undermine Israeli nuclear deterrence.

Louis René Beres was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971). He is the author of many major books and monographs dealing with nuclear strategy and nuclear war, including Terrorism and Global Security: The Nuclear Threat (Westview,1979); Apocalypse: Nuclear Catastrophe in World Politics (The University of Chicago Press,1980); Mimicking Sisyphus: America’s Countervailing Nuclear Strategy (D.C. Heath/Lexington, 1983); and Security or Armageddon: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy (D.C. Heath/Lexington, 1986). His most recent articles have appeared in US News & World Report; The Atlantic; The Jerusalem Post; The Washington Times; Harvard National Security Journal (Harvard Law School); International Security (Harvard University); The Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs; Parameters: Journal of the US Army War College; and International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. He has lectured widely on law and strategy issues at both United States and Israeli military/intelligence institutions. In Israel, his specially-prepared monographs have been published for many years as selected Working Papers of the annual strategy conference at Herzliya. Professor Beres is a regular contributor to OUPblog.

If you are interested in learning more about nuclear politics in the Middle East, The Nuclear Question in the Middle East, edited by Mehran Kamrava, combines thematic and theoretical discussions regarding nuclear weapons and nuclear energy with case studies from across the region. The nuclear age is coming to the Middle East. Understanding the scope and motivations for this development and its implications for global security is essential.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Israel’s strategic nuclear doctrine: ambiguity versus openness appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesForeign direct investment, aid, and terrorismThe “brave” old etymologyQ&A on Saint Augustine with Miles Hollingworth

Related StoriesForeign direct investment, aid, and terrorismThe “brave” old etymologyQ&A on Saint Augustine with Miles Hollingworth

November 13, 2013

Seamus Heaney: The last word

Noli temere, Seamus Heaney texted to his wife in his last hours of life, ‘Have no fear’. It was his son who revealed this message when he spoke at the funeral service. This was a private communication, but his son must have known how much in character it was, that his father believed so much of the best in life is drained away by fear. Living fearlessly may have been a human ideal that came to him as he observed families and neighbours and a whole population living in terror for years on end during the Troubles. Fear was, perhaps, something he had to confront in himself, for even as he moved away from the battlefield in Belfast to Glanmore in the Wicklow mountains south of Dublin, the daily atrocities went on, their reverberations still echoing in his poems. Perhaps, indeed, he felt that the creative act itself, at the centre of his life, had to conquer fear, and that the imagination could not be free to create if fear overwhelmed it: ‘walk on air,’ he counseled himself, ‘against your better judgement’.

But this private message to his wife and family was not his last word as poet, for in his final collection, Human Chain, he placed at the end a poem called ‘A Kite for Aibhín’ and its last word is ‘windfall’. He recalls a moment in childhood: ‘I take my stand again, halt opposite /Anahorish Hill to scan the blue’. He is back in his birthplace with friends attempting to launch a kite. It ‘goes with the wind . . . / climbing and carrying, carrying farther, higher’ until the string breaks and ‘the kite takes off, itself alone, a windfall’. Since the first collection, Death of a Naturalist, mapping the place around Anahorish, he was taking off. Concrete, physical, his language could always break free into the marvelous. The energy of the wind carried him upwards and the poems set free might land at our feet, windfalls from the blue.

Seamus Heaney

It may be that he truly had last words in mind when he chose to end the previous collection, District and Circle, with a poem called ‘The Blackbird of Glanmore’, the final words of which are ‘when I leave’. He had been seriously ill during the writing of the poems in that collection. For decades Glanmore was a haven, his ‘house of life’, and a place of inspiration rivaling the first home place. Now as he returns and sees a blackbird, he recalls lines he has translated ‘I want away / To the house of death, to my father / Under the low clay roof.’ He recalls also his young brother who died, referred to in his first collection. It is as if the blackbird, presiding spirit in the background, has brought him full circle, to the last word, ‘when I leave’.I would not have considered these closing poems had I not been mesmerized by ‘Postscript’, the final lines of The Spirit Level, which he also kept as the final poem in Opened Ground: Poems 1965-1995. When I read that poem, after being an intermittent reader through the decades, I was caught off guard: this last poem, an afterthought, allowed a glimpse through the back door, as it were, into the workings of his imagination. Somehow, when I came upon this ‘windfall’ poem, I felt that it would allow me to discover all the creative energies, the registers of a voice, the themes and variations woven into a symphony, all the colours and reflections inside a major ‘monument of unaging intellect’.

It may be that I felt a personal connection to ‘Postscript’ because of its location. It was, I understand from Stepping Stones, written as a ‘postcard’ for Brian and Ann Friel who had driven along the southern shores of Galway Bay with him. The poem follows the Atlantic coast of Clare as they drive, ‘the wind / and the light are working off each other’, the ocean is wild, there is a Yeatsian lake with swans, and they might have stopped to take in the spectacular view. But this is a moment of energetic intensity culminating in ‘big soft buffetings come at the car sideways / And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’ I gasped the first time I read it, for I had often driven that road, not far from where I grew up, and then this poem of openness to the wind and the light and the literary promptings seemed to open a way into Heaney’s creative energy. The poem was less a postscript than a manifesto.

It was the larger excitement of discovery that moved me. It felt like another Heaney had come to life, one more fully alive than the dazzling wordsmith I had encountered in all my years of admiring and appreciating. Those last words felt like a beginning of a new kind of confidence and trust in the supreme poet, trust also in my ability to read him and find the life-blood of the whole endeavour: the fearless heart.

After studying literature in University College, Dublin, Denis Sampson moved to Montreal, where he earned a Ph.D. at McGill University. He has lived and worked in Montreal since the 1970s but returns to spend part of each year in Ireland. He is the author of Young John McGahern: Becoming a Novelist. He also writes personal essays (memoir and travel), book reviews, and literary features, broadcasts on the radio, and gives talks and public lectures.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Seamus Heaney. By Sean O’Connor, cropped by Sabahrat [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Seamus Heaney: The last word appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe playing placeHeaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everydayQ&A on Saint Augustine with Miles Hollingworth

Related StoriesThe playing placeHeaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everydayQ&A on Saint Augustine with Miles Hollingworth

The “brave” old etymology

One of the minor questions addressed in my latest “gleanings” concerned the origin of the adjective brave. My comment brought forward a counter-comment by Peter Maher and resulted in an exchange of many letters between us, so that this post owes its appearance to him. Today I am returning to brave, a better-informed and more cautious man. Romance etymology is not my turf, though from time to time I discuss English words of French origin. Whenever I do it, I feel out of my element and indulge in a goodly amount of hedging. My most successful inroad on this area was probably an essay on bigot, but only because I discovered a review of which no one seems to be aware.

The problems facing Romance etymologists are, in principle, not different from those familiar to students of Germanic, except that the Romance languages go back to Latin, while Proto-Germanic is a reconstructed language. Yet hundreds of words in French, Spanish, Portuguese, and other Romance languages, including even Italian, either do not have indisputable Latin sources or are not traceable to any Latin roots, so that their early history is as hard to find out as the history of many English, Dutch, German, and Scandinavian words. Bravus is one of them. It turned up in Medieval Latin, and no one knows for sure where it came from.

Those interested in etymology should also be interested in how specialists discover word origins. Even if we agree that with a few exceptions our concern for the history of etymology need not go beyond the nineteenth century, the number of guesses about the sources of Greek, Latin, Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, and Romance words is huge. Modern explorers never begin from scratch and naturally want to know the hypotheses of their predecessors. No matter that many conjectures are naïve or even silly. Panning for gold involves a lot of sifting. That is why, when I embarked on writing a new etymological dictionary of English, I first put together a huge database. Thousands of pages were screened for everything said in any language at any time about the origin of English words. But I had to limit myself. For example, nectar is an English word, but its origin should be discovered by students of Greek, and, although I am aware of numerous works on nectar, I passed over most of them and allowed the Greeks to bury their dead. The same holds for Romance. Brave is a fine English word, but Romance, not English, scholars should tell us where and how it arose. That is why I skipped without interest an article on brave that Peter Maher wrote more than forty years ago. I even forgot that it existed. If I had been aware of it when I was writing my gleanings, my comment would have looked different. Anyway, by now I have familiarized myself with multiple publications on the descent of brave. The literature on this word is not vast: the dictionaries and a dozen or so articles.

So where did brave come from? The best-known putative etymon of Medieval Latin bravus is Classical Latin barbarus. These are the glosses of barbarus given in Oxford Latin Dictionary: “of or belonging to a foreign country or region (“non-Greek”); ignorant, uncivilized, unpolished, uncouth; (of natural objects) wild, uncultivated, rough, cruel, fierce.” The glosses from three modern dictionaries run as follows. Spanish: bravio (of animals) “ferocious, wild, untamed”; (of plants) “wild”; (of people) “rustic, unpolished.” Italian: bravo “clever; skillful; good; worthy; honest; brave.” French: brave “brave, bold; good, honest.” French faire le brave means “to bluster; brag”; brag will haunt us some time later. Portuguese bravo and bravio add no new senses. The French adjective is a borrowing of Provençal brau ~ bravo. German brav and Engl. brave are loanwords from French. Scots braw is a variant of brave. The straight path from Latin barbarus to Spanish and Portuguese bravio would be through “wild, uncultivated, fierce, savage.” “Bold” presupposes an amelioration of “fierce,” while “honest, worthy” and “good” are still farther away from Latin.

The main handicap in connecting brave and barbarus is phonetics. Barbarus had to become brabarus by metathesis (ar to ra) and lose part of its middle or to turn some other somersaults in order to produce the form bravus (b to v after a vowel is “regular,” lautgesetzlich, to use the German term). For that reason, many researchers rejected this etymology, though similar changes have often been recorded. Another suggestion traces bravus to Latin rabidus “raving, mad; rabid” (it is the oldest etymology of bravus on record). But here we are missing b-! The unattested adjective brabidus has been invoked as the etymon of Old Italian braido “sprightly, nimble; good”; yet it is unclear whether braido has anything to do with rabidus. Initial b in bravus might have come from some words denoting animal cries and all kinds of noises (compare French bruit “noise” and Engl. bray, from French, and remember that bravio was especially often used about untamed animals), but there is no way to prove that this reconstruction is right.

When a blend is known to be a blend, everything is fine (consider motel, smog, and their likes). In other cases, we cannot go beyond intelligent guessing. Perhaps squirm is a blend of squirt and worm, but perhaps it is not. All the analogs that have been cited for br from r are dubious. Several variations on this etymology (for instance, the sought-for source was said to be not Latin rabidus but some Germanic adjective like German rauh ~ Engl. raw) do not improve matters. A few other conjectures, though offered by respectable scholars, have so little credence that the authors of serious dictionaries and learned articles do not even find them worthy of discussion (and say so).

The strongest competitor of the barbarus—brave etymology is the one that derives bravus from Latin pravus “wrong, bad, deformed.” If we agree that the Spanish and Portuguese senses are especially close to those of the unattested etymon, then the word must have originated in the Iberian Peninsula, spread to Italy and France and from France to several countries of Europe. The story apparently began with “wild, untamed, uncultivated.” In the language of chivalry, “wild” acquired noble overtones and “courageous, gallant; worthy, good” arose. Among the glosses of Latin pravus we don’t find “uncultivated.” Maher has offered a strong defense of the pravus—brave etymology. He showed that in some contexts pravus could be understood as meaning “uncivilized, wild.” Another problem is pr- versus br-. Between vowels, Latin -pr- regularly became Spanish -br-, as in capra to cabra “nanny-goat,” but in pravus the group pr- stands at the beginning of the word. Here again Maher pointed to the possibility of pravus or its Romance reflexes often occurring after a word ending in a vowel. Although some cases of initial p to b have also been recorded, this etymology depends on the semantic and phonetic context rather than on the evidence of isolated words (and this idea was the main point in Maher’s contribution). It is not for me to decide whether its probability is considerably higher than that of some others.

In my gleanings, I suggested that, if being made to choose between barbarus and pravus as the etymon of brave, I might prefer the first. Today I should say more clearly that neither strikes me as particularly convincing. Nor is, to my mind, (b)rabidus quite fanciful! If it were, such different etymologists as the rather conservative Norwegian Johan Strom and the passionately nonconformist Swiss researcher Hugo Schuchardt would not have supported it. The bad thing about etymological dictionaries (and here I find myself in full agreement with Maher) is that most of them offer too little discussion. Tentative opinions solidify into dogmas and are offered to the public as truths. Popular books copy them unthinkingly, and untested ideas become common knowledge. In the first edition of his dictionary, Friedrich Kluge (every historical linguist’s role model) put a question mark at the etymology of German brav from barbarus. Later he found this derivation solid, and the question mark disappeared. The French dictionary of Ernst Gamillscheg (an extremely knowledgeable author) also does without a question mark (brave from barbarus). In Italy, Prati said “unclear, but not from barbarus, rather from pravus.” By contrast, Devoto believed that the ways of barbarus and pravus crossed and produced bravo. Much sorrow and little wisdom come from reading even the best dictionaries.

The great seventeenth-century lexicographer Charles Du Cange, a marvel of diligence and perspicacity, whom one is tempted to call a genius, observed that the Medieval Latin noun branas means the same as brava. In 1950, George G. Nicholson took up this idea and suggested that brav- is indeed a learned misreading (note: a misreading, not a mispronunciation) of bran-, influenced by pravus. Strangely, such “catastrophes” are possible. Engl. gravy, from late Middle English graué, seems to be a misreading of Old French grané, because u and n were easily confused in manuscripts. In printed texts, grané often appeared as gravé. Nicholson’s article, lost in a three-volume Festschrift, does not seem to have attracted anyone’s attention (a common case in etymological studies). I ran into it while looking through every Festschrift I could lay hands on. It will be a great joke if such was the history of bravus: a tame ghost, the result of a linguistic miscarriage, conquering the world. Once again, I reserve judgment.

Bravissimo, Oxford Etymologist!

It now remains for me to say that at the time when English lexicographers gave the initial meaning of brave as “finely arrayed, showy” or simply “capital, excellent” (as in the brave new world), this word was derived from Celtic and paired with Engl. brag, allegedly also from Celtic. Skeat thought so for a short while, Wedgwood never changed his opinion that brave and brag are related, and even Weekley considered Celtic as a possible lending language of brave. Some time ago, I devoted a post to brag (which I dissociated from brave) and need not go into the question again. To conclude: today it takes a brave man (or woman) to have a strong opinion on the origin of brave. I am, unfortunately, timid.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: pplause GIF Avia imagine OW-DIRECTION Tumblr.

The post The “brave” old etymology appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAmazing!Etymological gleanings for October 2013“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2

Related StoriesAmazing!Etymological gleanings for October 2013“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2

Q&A on Saint Augustine with Miles Hollingworth

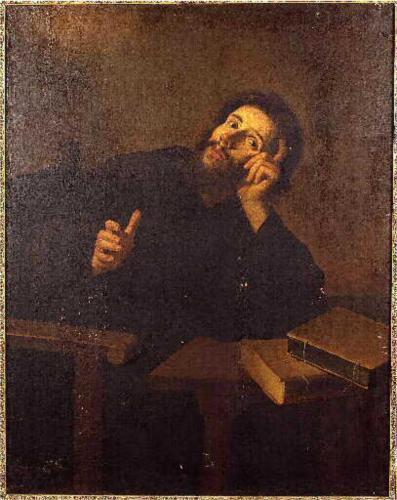

After meeting this summer, the OUPblog suggested Miles Hollingworth, author of Saint Augustine of Hippo: An Intellectual Biography, catch up with fellow Augustinian scholar Todd Breyfogle about the timeliness and relevance of Augustine in order to celebrate the saint’s birthday, 1,659 years to the day later.

Saint Augustine in meditation. Painting by Bartolome Esteban Murillo. Public domain via WikiPaintings.

Todd Breyfogle: Why Augustine? Why now?

Miles Hollingworth: I have simply felt for some time now that we are the age who can do most for him. I suppose this is a statement about how history treats genius figures like Augustine. The usual way has been to investigate what they have done of right and wrong to get us to this pass – i.e. their impressive contributions to histories of various things like Christianity, literature and sexuality. But I felt compelled to go in the other direction: to try to summon up every bit of empathy and humanity that we have collectively learnt in the intervening 1600 years (and should be proud of, by the way): and then to use that to reach a friendly hand back to him. Remember: geniuses make history, but they are also ahead of their times. So I wanted to see what kind of middle he and I might meet in if I did that. Because I feel we owe that to sensitive souls like Augustine, who might have felt alienated by their own ages, and who can be helped by us now.

Todd Breyfogle: One of the most compelling aspects of your summoning up “every bit of empathy and humanity” is to ask us to think of Augustine as “a novelist”, as an artist striving to integrate a personal, cultural and existential narrative against the backdrop of the stories of Genesis. What makes Augustine “a novelist”?

Miles Hollingworth: For me, it is because all of his leading ideas function, and are described, like human characters. Like Adam and Eve. This made a giant impression on me against how, nowadays, we can be encouraged to feel we should be reaching instead for neutral, sanitized language in human studies. You know – ‘the agent’, ‘the actor’. I accept that doing this holds out the tantalizing prospect of stumbling onto the same kinds of patterns we already get in, say, mathematics. Yet when we read a great novel, we don’t look for or enjoy this. We take for granted that there is a ready-written storyline (predestination); and therefore what we look for and enjoy is the relationship of truthfulness that strikes up between that storyline and the characters we follow through it as we read. Augustine got the ready-written storyline given to him by his acceptance of the Christian Scriptures and God’s omniscience; but what he did with it next made me think of his achievement as like, yes, a great novelist. He wants you – his reader – to rate what he is saying according to that same inner gyro you use when you enjoy good fiction; and enjoy it by recognizing its human element to be true. And for him, of course, that true human element is what he means by talking of love all the time. We don’t just rationalize like automatons: we don’t have the advantage of seeing it all from on high like the gods and devils: our feet are on the ground and we love (and hope)! It is responsible for the best and the worst of us. I believe this is why his writing on the Two Cities remains such an evocative motif today – and by the same token, why it was so quickly able to become the Middle Ages’ very own 19th-century novel. Their Crime and Punishment, if you like!

Todd Breyfogle: In your exploration of Augustine’s multiple narratives of “that true element” of humanity, what about Augustine the person did you come to find most compelling?

Miles Hollingworth: His determination never to get over the woman, the great love of his life, who was torn from his side at his mother’s instigation after 15 years of happiness – all so that he should be free to make a ‘better’ society marriage into an upper class Christian family. This played out shortly after his conversion, when he was actually in deep ennui about what to do next with his life. Everyone knows that as his tribute to her he would choose celibacy ever after and his famous and epic silence about her unto death. He never gave up any further details about their love together, other than that it was a great love; or even her name. But silence in a passionate man is sound everywhere else: and as I became gripped by this, I started to see her beautiful shape in motion behind more and more of his soaring, stand-alone depictions of beauty, loss and regret. Yes: he was remembering her, and making fluency out of that heartbreak! The fact of the matter is that Augustine should never have let her go. But good for him that he chose to suffer under this knowledge to his dying day. Good for him that he let her haunt the rest of his life. Another kind of man would have closed ranks and ironed her out of his heart. So to me he became most compelling as the man who just wouldn’t – who just couldn’t – do that.

Todd Breyfogle: In that same vein, Augustine—perhaps not unlike Montaigne—has always seemed to me as someone who both thinks and feels deeply. How have you come to see Augustine’s integration of how we know and how we feel—how we love?

Miles Hollingworth: That’s right. Except for Augustine, thinking is parasitic upon feeling, parasitic upon love. He would therefore have approved of the argument for the (traditional) lights of conscience that C. S. Lewis made in The Abolition of Man. Actually, if I remember correctly, Lewis did actually enlist Augustine’s help in that essay. Augustine deals with this important question of thought and feeling best when he is looking forwards to eternity. It is the essence of his contribution to mysticism. Think of his ‘vision at Ostia’, or his countless epigrams concerning the inexpressibility of God. Pure thought can document its own processes as science; and some excellent treatises on logic and language already existed in Augustine’s day. Pure thought can also predicate and classify; and this descriptive power has given us the wonder of science and human knowledge. But pure thought cannot live for itself: I mean, it cannot create things ex nihilo. Adam and Eve were not made rational in order to thrill at their own capabilities – that came afterwards, as their fall. The actual, tactile content of life is encountered as that which we feel. So Augustine says that we feel God; but then in thinking through that feeling and trying to describe it, we lose something and step back. Worse follows if we try actually to prove God. Much better if our feelings and thoughts were somehow able to be the exact counterparts of each other… Actually, didn’t Montaigne once say something like, ‘truth and art don’t – can’t – live for themselves, but for something else outside of them which draws them on’? If he did say that, then you would certainly have to rank him alongside Augustine on this question.

Todd Breyfogle: Our world of digital media is arguably transforming how we think and feel. If Augustine were to offer us today a Tweet of salutary advice, what would he say?

Miles Hollingworth: I am smiling because Augustine would have loved Twitter, I’m sure. Just imagine him tweeting furiously against the Manichaeans, and Donatists and Pelagians… (#contra)! Actually, for someone who could write to extraordinary lengths in books like City of God, some of his most piercing wisdom was issued in the ‘tweet’ form of

If the air is withdrawn, the body dies; there can be no question of that. And if God is withdrawn, the soul dies; and there can be even less of a question of that [In Io. Ev. tr., CI, 6].

Miles Hollingworth is a philosopher, writing on the Western tradition – its key texts and figures. For the last number of years his work has focused on St. Augustine of Hippo. His latest book is Saint Augustine of Hippo: An Intellectual Biography. Todd Breyfogle is Director of Seminars for the Aspen Institute, including the Aspen Executive Seminar on leadership, values and the good society, since 1950 the heart of the Aspen Institute’s neutral forum for enlightened dialogue. His writings range from classical to modern political philosophy, as well as art, music, and literature.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Q&A on Saint Augustine with Miles Hollingworth appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe playing placeThe many “-cides” of DostoevskyWhen did Oxford University Press begin?

Related StoriesThe playing placeThe many “-cides” of DostoevskyWhen did Oxford University Press begin?

When did Oxford University Press begin?

Determining the precise beginning of Oxford University Press is not as easy a question as it may seem. It’s not enough to brandish triumphantly the first book printed in Oxford, Expositio in symbolum apostolorum, as all that proves is that there was a printing press in Oxford in 1478…

Part of the difficulty is that it’s all too easy to project back our modern concept of a ‘university press’: that is, an institution, under the direct financial and administrative control of a university, dedicated to publishing scholarly works. Using that definition, there was no true ‘university press’ anywhere in Europe prior to the mid-seventeenth century, despite the fact that there were dozens of universities that were printing and publishing. Universities instead preferred to employ printers to do their printing and publishing for them.

Identifying these ‘university printers’ is not always easy. It was not enough simply to be a printer in a university town: for example the Lichfield family remained printers in Oxford well into the eighteenth century, even though they were no longer formally associated with the University. A more problematic case concerns the earliest printers at Oxford. Books were printed at Oxford in the 1470s and 1480s, and again in 1518–19, and a number of the imprints make tantalizing references to being printed at the University rather than just Oxford but it is not until Joseph Barnes in the 1580s that there is a record of a formal appointment. Nor is it until we get to Barnes and his successor that we see unequivocal references to the ‘printer to the university’ in imprints.

When did the ‘university printer’ yield to the ‘university press’? Well, for most of Europe, this doesn’t seem to have happened until the nineteenth century or even later. In Oxford’s case, however, it is tempting to identify that moment of transition much earlier. A case could be made for 1619, when the University first took ownership of some printing equipment (a series of type-matrices). Or for the 1630s when, thanks almost entirely to William Laud, Chancellor of the University, the management of printing was enshrined in revised university statutes and a series of charters. A ‘Delegacy’ was established specifically to oversee university printing while the statutes created a new post, an Architypographus to act as an academic overseer of the press. Laud made provision for a salary and for a source of income to underwrite publications. In this decade, the University increased its holding of type and struck a lucrative deal with the London book trade to forbear from encroaching on their printing privileges. Laud also began exploring the possibility of premises for the press and of training suitably scholarly compositors and correctors.

Alternatively, one might date the foundation of a ‘university press’ to the 1660s, with the provision of specially-designed premises (the Sheldonian Theatre) and new equipment: presses, frames, type-cases, and so on. This decade also saw a newly constituted group of Delegates, who initially at least met regularly. But, even then, there seems to have been shortcomings in terms of institutional management which led John Fell (Dean of Christ Church, Vice-Chancellor, and later Bishop of Oxford) to go so far as to create his own partnership in the 1670s which then leased the whole printing operation from the University.

Instead one could cite the 1690s as the decisive moment as oversight of printing was returned to the Delegates. Or for that matter the 1710s, when the press moved into its own specially built printing house (the Clarendon building). Or the 1750s, when William Blackstone radically reformed the management and economics of the press. Or perhaps even the 1780s, when the University resumed control over the printing of Oxford Bibles which had been leased out to a variety of London printers and booksellers since the late 17th century and thus, for the first time, was in economic and administrative control of all printing and publishing done in its name.

Ian Gadd is Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University. He is editor of The History of Oxford University Press–Volume 1: From its beginnings to 1780.

To celebrate the publication of the first three volumes of The History of Oxford University Press on Thursday and University Press Week, we’re sharing various materials from our Archive and brief scholarly highlights from the work’s editors and contributors. With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Watch the silent film or learn about arguments over the first printing press in Oxford in our previous posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Oxford from above at sunset. © Andrea Zanchi via iStockphoto.

The post When did Oxford University Press begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBefore Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing cityOxford University Press and the Making of a BookA gentleman’s tour of Regency London prisons

Related StoriesBefore Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing cityOxford University Press and the Making of a BookA gentleman’s tour of Regency London prisons

Foreign direct investment, aid, and terrorism

In recent years, developing nations have been major venues of terrorism. One significant problem caused by terrorism in developing nations is the reduction of foreign direct investment (FDI) into these nations as potential investors seek safer locations. Terrorism raises political instability, destroys infrastructure, and puts the lives and property of workers (foreign and domestic) at greater risk. The ex ante effect of these risks is akin to a reduction of output produced from a given level of inputs, effectively lowering the rate of return of FDI. Thus, the greater the terrorism risk in a particular developing nation, the greater the diversion (and outflow) of FDI from that potential destination nation to a competing lower-risk destination.

The literature on the economics of terrorism has helped to quantify the adverse effects of terrorism on FDI. For example, Abadie and Gardeazabal (2008) find that a significant increase in terrorism risk can reduce net FDI position by approximately 5 percent of a nation’s GDP. However, this literature does not tell us whether the two components of terrorism, domestic and transnational, have similar effects on FDI. A terrorism incident is “domestic” when it is entirely homegrown and home-directed, where the perpetrators, victims, supporters, and targets are all from the venue nation. In contrast, terrorism is “transnational” where at least two nations’ citizens or properties are involved. While both forms of terrorism enhance investment risk, we anticipate a greater marginal impact of transnational terrorism on FDI in the venue nation for at least two reasons.

First, it is possible that foreign assets and personnel may be directly targeted by the terrorists to achieve greater international attention. Second, in the case of transnational terrorism, terrorists’ assets may be partly based abroad, making it harder for the venue nation to succeed in its counterterrorism efforts. Ultimately, comparisons of the effects of the two types of terrorism on FDI require careful empirical analysis. Using data from 78 developing nations between 1984-2008, we find that a one standard deviation increase in domestic terrorist incidents per 100,000 persons reduces net FDI between 323.6 to 512.94 million US dollars for an average developing country. Turning to transnational terrorism, a one standard deviation increase in incidents per 100,000 persons reduces net FDI between 296.49 to 735.65 million US dollars for an average developing country. It should be noted that the decline in FDI is larger for domestic terrorism because in terms of absolute numbers, domestic terrorism incidents far outweigh transnational terrorism incidents in developing nations. Indeed, along the lines of our expectation above, we find that, at the margin, an incident of transnational terrorism causes a greater adverse effect on FDI than an incident of domestic terrorism.

Foreign aid provided by developed nations can provide scarce resources that developing nations can use to fund their counterterrorism activities. To the extent that foreign aid is fungible, aid given for other purposes may still help in relaxing the counterterrorism resource demands of a developing nation, thereby mitigating FDI losses from terrorism. Our analysis reveals that this is precisely the case – the lower estimates of FDI losses due to domestic terrorism are reduced to US$113.44 million or by just under two-thirds. The reduction of losses due to transnational terrorism is also dramatic with the lower estimate being reduced to US$45.24 million or by about five-sixths. The mitigating influence of aid on terrorism-induced losses in FDI has not been recognized nor quantified in the literature.

Finally, we distinguish between multilateral and bilateral aid, and find that bilateral aid is more effective in reducing the adverse FDI effects of transnational terrorism, while multilateral aid is more effective in limiting FDI losses due to domestic terrorism. Due to data limitations, we cannot explicitly investigate what causes this difference. One possible explanation is that donors provide bilateral aid to nations where they have FDI interests, thus closely tying such aid to specific counterterrorism measures that safeguard donors’ interests. In contrast, multilateral aid may help the recipient nations improve their overall economic performance, thereby curbing grievances and the ensuing domestic terrorism. Improved economic performance and more harmonious citizens can then enhance FDI inflows.

Subhayu Bandyopadhyay, Todd Sandler, and Javed Younas are authors of ‘Foreign direct investment, aid, and terrorism’, published in Oxford Economic Papers. Subhayu Bandyopadhyay is a Research Officer at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. His research interests include international trade and the economics of terrorism. Todd Sandler is the Vibhooti Shukla Professor of Economics and Political Economy at the University of Texas at Dallas. He has contributed articles on terrorism to top journals in economics and political science since 1983. Javed Younas is an Associate Professor of Economics in American University of Sharjah. His research is in the areas of international economics, development economics and economics of terrorism.

Oxford Economic Papers is a general economics journal, publishing refereed papers in economic theory, applied economics, econometrics, economic development, economic history, and the history of economic thought.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Stock market. By JordiDelgado, via iStockphoto.

The post Foreign direct investment, aid, and terrorism appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of JusticeWhite versus black justiceIs big data a big deal in political science?

Related StoriesThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of JusticeWhite versus black justiceIs big data a big deal in political science?

The playing place

In Cornish towns and villages you may find a street or a district called Plain-an-Gwarry. The name (in the old tongue plân-an-guare), means ‘a playing place’, and it commemorates the former existence of a round, or small amphitheatre, in which entertainments of one sort and another – including the miracle plays – were staged and public meetings held. And lately, thinking about poetry, and especially about its vital importance in public life, I’ve been remembering the recreation ground we used to go to as children, the Rec, the public space set aside for fun and games, for exercise, a place you went to, it cost you nothing and being there did you good.

Poetry is the Rec, the playing place, in which the mind and the imagination are free to exercise and enjoy themselves. This healthful zone is not a memory of the good old days nor a hoped-for amenity in Never-Never Land, it survives still in the here and now as a dedicated public space, bang in the middle of ordinary civic life. And it is ours inalienably, it can’t be sold off, developed, privatised.

In October 2011 Occupy London had intended to picket the London Stock Exchange and the big banks in Paternoster Square, but they were prevented from doing so by the square’s owners (Mitsubishi Estate Co.) who took out an injunction against them which the police enforced and prevented them from entering that unpublic space. Instead they camped nearby outside St Paul’s, a public monument it costs you £16 per adult head admission.

Poetry starts in the experiences and in the abilities of one individual, who is, however, a member of the human race and the citizen of a particular country under one political dispensation or another. Poetry, most often written and read in solitude, is a thoroughly social activity. Insisting, as I do in my volume of The Literary Agenda, that poetry matters, I mean that in manifold and important ways it matters not just for the individual writer and reader but also, and even more necessarily, for the society in which those readers and writers live. Poetry addresses the condition of being human in a particular time and place. But even composed many centuries ago, in circumstances quite unlike our own, still it touches us in our humanity now; and doing so it will very often, perhaps always, address the social condition in which we thrive or suffer. Poetry addresses the state we are in – unsettlingly, exciting in us the desire and the demand for a life we should be glad to call our own.

The plân-an-guare was a place for both instruction and entertainment. So is poetry. Many great poets and thinkers about poetry have rooted its chief value and effect in pleasure. Coleridge, for one. Poetry, he says, gives a “pleasurable excitement”; it brings the mind into “pleasurable activity”. And it is in that pleasure, more than in any overt instruction, that the chief good, the usefulness, of poetry resides. The excitement and activity Coleridge speaks of are beneficial. The pleasure we feel is that of a quickening through the imagination into ways of being human which are freer, more connected, more humane, than those we mostly have to make do with in the state we are in. This excitement and enlargement, pleasurable and good in itself, has, of course, a social dimension and important social implications. Poetry helps us to imagine and to participate sympathetically in other lives. It is a force against atomisation, against any reduction of the citizen to statistic and commodity.

In the sixth form we were told by our English teacher that the purpose of teaching English was to increase sales resistance. Dwelled on, developed, variously applied, that dictum will do nicely. He helped me into the love and enjoyment of literature, and of poetry in particular. In the playing place of poetry, exercising there, getting better at the game, reading and meeting other readers and writers, enjoying ourselves, learning for the fun of it, we can be helped into a critical alertness, and ask more, demand more of our politics and politicians. A quickened electorate will elect better representatives, out of its own better educated, livelier and more demanding mass.

Poetry nowadays has become what by its very nature it always aspires to be: a lively democracy. Look at the lists of the best publishers of poetry in the United Kingdom: men and women equally represented; all manner of vernaculars given their say; the Queen’s English now the dialect of perhaps only Her Majesty; RP sent to Rest in Peace; much translation. Poetry in Britain today springs from and speaks for the real mix of our nation. And it is freely – or cheaply – available. Hurry to our surviving public libraries; assemble your own canon from Oxfam; add new works to it from your friendly local independent bookshop. It’s all there, all yours. And from this safeguarded public playing place, sallying forth, sharing the pleasure and the profit of it, who knows what other zones of life you might reclaim for your own and for the public good.

David Constantine is a poet, novelist, and short-story writer who taught German language and literature at Durham and then Queen’s College, Oxford. He is the author of Poetry, which is part of a new series The Literary Agenda. He has translated Goethe’s Elective Affinities for Oxford World’s Classics. In 2010 he won the BBC National Short Story Award, and in 2013 he won the Frank O’Connor Award for short fiction.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Coloured chalks on the playground. By Ivan Jekic, via iStockphoto.

The post The playing place appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe many “-cides” of DostoevskyA gentleman’s tour of Regency London prisonsBefore Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing city

Related StoriesThe many “-cides” of DostoevskyA gentleman’s tour of Regency London prisonsBefore Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing city

November 12, 2013

Shanghai rising

The port city of Shanghai is poised to become another major center of the global art world, possibly even displacing Beijing as China’s artistic capital. Since founding a biennial and art fair in 1996 and 1997, respectively, major institutions supporting the visual arts have sprung up or expanded. Despite the closure of studios and galleries at 696 Weihai Road in the spring of 2011, Shanghai’s gallery scene is flourishing, and the Chinese government is encouraging the development of a commercial art market in Shanghai. The State Council recently created a commercial-friendly and eventually tax and duty free zone in the city, allowing international auction house Christie’s to hold its first-ever sale on mainland China in September. Among the works included in the sale were Bicycle by Zeng Fanzhi, which sold for $1.5 million and Cai Guo-Qiang’s Homeland, which brought in $3.4 million.

Shanghai view from Peace Hotel. Photo by Michel R. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The national government is also investing in major public museums in Shanghai, announcing in late 2011 an initiative to open 16 new museums by 2015. The city, China’s most populous and its economic capital, now boasts an impressive number of modern and contemporary art museums, including the Museum of Contemporary Art (founded 2005). In addition, both the Power Station of Art and the China Art Museum (formerly the Shanghai Art Museum) opened in October of last year. The China Art Museum is huge in its size (nearly 1.8 million square feet, reportedly the biggest museum in Asia) and in the scope of its collection and exhibitions, garnering comparisons with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

China Art Museum, Shanghai. Photo by DavidXiaoDaShan. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

But while the state is able to deploy such resources to construct and manage the institutions, the nature of the art they will house and exhibit has been called into question. Not only does the government target artists who make politically challenging statements or art works, but it also promotes what some would characterize as a sanitized version of Chinese cultural history. A current exhibition at the Power Station of Art, a retrospective covering the last 30 years of Chinese art (including works by Zeng Fanzhi, Yue Minjun, and Liu Ye), has been criticized for omitting the work of one of China’s best-known living artists, Ai Weiwei. Ai and other Chinese artists who openly criticize Communist Party policy in their works exhibit successfully abroad, however. An example is Zhang Huan, who according to the Benezit Dictionary of Artists explores “the communal fate of migrant workers; population control, including the one-child policy and abortion; and poverty in rural China.” A recent show of his work in Florence, Italy drew record crowds. Curators of the Armory Show in New York have recently announced that next year’s show will focus on contemporary Chinese art.

In the meantime, scholars and connoisseurs of Asian art will no doubt be watching Shanghai’s rise, and how members of the art world work within the city’s commercial, political, and cultural climate.

Kandice Rawlings is the Associate Editor of the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, now with new and revised articles on contemporary Asian artists. Each Benezit entry consists of a brief biography and overview of an artist’s work, and many entries also list exhibition histories, bibliography, and auction records, offering both general information for casual users and avenues for further research for students and scholars.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Shanghai rising appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPhantoms and frauds: the history of spirit photographyA medieval saint in modern timesBack to (art) school

Related StoriesPhantoms and frauds: the history of spirit photographyA medieval saint in modern timesBack to (art) school

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers