Oxford University Press's Blog, page 878

November 18, 2013

Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’

It’s that time of the year again. With a fanfare and a drum roll, it’s time to announce the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year. The votes have been counted and verified, and I can exclusively reveal that the winner is….

Selfie

Illustrations © Barry Hall, cube fish media.

A picture can paint a thousand words

The decision was unanimous this year, with little if any argument. This is a little unusual. Normally there will be some good-natured debate as one person might champion their particular choice over someone else’s. But this time, everyone seemed to be in agreement almost from the start. Other words were considered, as you will see from our shortlist, but selfie was the runaway winner. It’s not a new word. For starters, it has already been included in Oxford Dictionaries Online (although not yet in the Oxford English Dictionary), and we wrote about it as part of our occasional Words on the Radar series back in June 2012. But our Word of the Year need not be a new word. However, it does need to demonstrate some kind of prominence over the preceding year or so and selfie certainly fits the bill. It seems like everyone who is anyone has posted a selfie somewhere on the Internet. If it is good enough for the Obamas or The Pope, then it is good enough for Word of the Year.

When it started

But what of the word itself? While it is safe to say that selfie’s star has risen over the last 12 months, it is actually much older than that. Evidence on the Oxford English Corpus shows the word selfie in use by 2003, but further research shows the earliest usage (so far anyway) as far back as 2002. Its use was, fittingly enough, in an online source – an Australian internet forum.

“Um, drunk at a mates 21st, I tripped ofer [sic] and landed lip first (with front teeth coming a very close second) on a set of steps. I had a hole about 1cm long right through my bottom lip. And sorry about the focus, it was a selfie.” (2002 ABC Online (forum posting) 13 Sept.)

The term’s early origins seem to lie in social media and photosharing sites like Flickr and MySpace. But usage of it didn’t become widespread until the second decade of this century and it has only entered really common use in the past year or so. Self-portraits are nothing new — people have been producing them for centuries, with the medium and publication format changing. Oil on canvas gave way to celluloid, which in turn gave way to photographic film and digital media. As the process became snappier (pun intended) so has the name. And now as smartphones have become de rigueur for most, rather than just for techies, the technology has ensured that selfies are both easier to produce and to share, not least by the inclusion of a button which means you don’t need a nearby mirror. It seems likely that this will have contributed at least in part to its increased usage. By 2012, selfie was commonly being used in mainstream media sources and this has been rising ever since.

Early evidence for the term show a variant spelling with a –y ending, but the –ie form is vastly more common today and has become the accepted spelling of the word. It could be argued that the use of the -ie suffix helps to turn an essentially narcissistic enterprise into something rather more endearing. It also provides a tie-in with the word’s seemingly Australian origins, as Australian English has something of a penchant for -ie words — barbie for barbecue, firie for firefighter, tinnie for a can of beer, to name just three.

Other body parts are available

Its linguistic productivity is already being seen by the creation of a number of related terms, showcasing particular parts of the body like helfie (a picture of one’s hair) and belfie (a picture of one’s posterior); a particular activity — welfie (workout selfie) and drelfie (drunken selfie), and even items of furniture — shelfie and bookshelfie. In fact, it seems that the words knows no bounds, although some do seem rather forced, with multiple interpretations, like the apparent delfie (where the d could stand for dad, dog, double, or rather inexplicably dead) or melfie, with the m being explained as Monday, moustache, male, or mum. Whether any of these catch on in the same way is debatable. The multiple meanings may prove a difficult obstacle to overcome. One of the more popular offshoots is legsie, where the photograph is of a person’s outstretched legs, often with a suitably glamorous background visible, although this shows the productivity of the concept, rather than of the word.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013 is ‘selfie’. The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a word, or expression, that has attracted a great deal of interest during the year to date and judged to reflect the ethos, mood, or preoccupations of that particular year and to have lasting potential as a word of cultural significance. Learn more about Word of the Year in our FAQ, on the OUPblog, and on the OxfordWords blog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2013: ‘selfie’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe “brave” old etymologyCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artAmazing!

Related StoriesThe “brave” old etymologyCharacters from The Iliad in ancient artAmazing!

Helping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness Month

Smoking causes the majority of lung cancers — both in smokers and in people exposed to secondhand smoke. To mark Lung Cancer Awareness Month, Nicotine & Tobacco Research Editor David J. K. Balfour, D.Sc., has selected a few related articles, which can be read in full and for free on the journal’s website. He also invited Elyse R. Park, PhD, MPH, to share what really helps smokers quit.

Every year over 220,000 Americans are diagnosed with lung cancer, and unfortunately most of these cases are found when the cancer is in later stages. A promising advance in lung cancer detection is a new screening test, the low-dose computed tomography, which provides a high-resolution 3D picture and so picks up lung cancer earlier. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) funded the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) to compare this new screening to chest x-rays among people who had heavy smoking histories. The NCI found that it showed promising results in detecting lung cancer earlier and in significantly decreasing lung cancer deaths.

Since this NCI trial, there has been a lot of talk about lung screening. Many cancer organizations are recommending lung screening, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force drafted recommendations that people with a heavy smoking history get annual lung screens. Many researchers and cancer advocates are also talking about the importance of pairing smoking cessation with lung screening, so that smokers who are getting lung screening are also getting support and encouragement to quit smoking. If smokers quit smoking after getting screening, this would increase the benefit of lung screening.

However, I have studied some smokers who participated in the NLST and found, despite the fact that many of them understood that continuing to smoke put them at high risk for lung cancer and smoking related diseases, and that many of them intended to quit smoking when they started the trial, most did not quit (Annals of Behavioral Medicine 37:268-79). At one year after their first screen most of these participants hadn’t quit smoking, although some tried to do so (Cancer 119:1306-13). Unfortunately, having a lung screening test didn’t really change the way that they felt or thought about smoking. I describe participants’ answers in qualitative interviews, which were recently published in Nicotine & Tobacco Research. So what could help these smokers quit?

I have also studied what happened when smokers saw their primary care doctors after getting lung screening, and these results were recently presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society for Clinical Oncology. If physicians just ask these smokers about smoking and advise them to quit, they are not likely to quit. What helps smokers quit is if physicians actually assist patients to quit – by giving them a counseling referral, a stop smoking medication prescription, or following-up to see how they are doing.

So if you have or know someone with a history of heavy smoking and want to find out more about lung screening, consult the American Lung Association guidelines and the American Cancer Society guidelines. Please also remember to talk to your doctor about getting help to quit.

Elyse R. Park, PhD, MPH, is Director of Behavioral Science Research for the Tobacco Treatment Center at the Massachusetts General Hospital and an Associate Professor of Psychology at Harvard Medical School.

November is officially Lung Cancer Awareness Month. To mark this, Nicotine & Tobacco Research joins the lung cancer community in highlighting the health risks associated with tobacco use. The Editor-in-Chief, David J. K. Balfour, has selected a collection of recent, topical articles which have been made free until the end of 2013.

Nicotine & Tobacco Research is one of the world’s few peer-reviewed journals devoted exclusively to the study of nicotine and tobacco. It aims to provide a forum for empirical findings, critical reviews, and conceptual papers on the many aspects of nicotine and tobacco, including research from the biobehavioral, neurobiological, molecular biologic, epidemiological, prevention, and treatment arenas. It is published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Anti smoking image. © ansar80 via iStockphoto.

The post Helping smokers quit during Lung Cancer Awareness Month appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorn out wonder drugsAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationDoes Mexican immigration lead to more crime in US cities?

Related StoriesWorn out wonder drugsAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationDoes Mexican immigration lead to more crime in US cities?

Place of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria

As we continue to tally the votes for Place of the Year 2013, Joshua Hagen, co-author of Borders: A Very Short Introduction, shares some background information on the history of Syria. After you’ve read the reasons surrounding why Syria made the shortlist, cast your vote below. We’ll announce the winner on Monday, 2 December 2013.

By Joshua Hagen

Syria has made the OUP Place of the Year shortlist for the second year in a row for its seemingly intractable civil war. Given this, it seemed an appropriate time to revisit the topic from last year.

The immediate cause of the conflict was broad-based protests in early 2011 demanding the ouster of President Bashar al-Assad, who had ruled the country since the death of his father and previous president in 2000. The government quickly resorted to brute military force to quash the protests, but significant portions of the military deserted their units and/or joined the protesters, which soon morphed into various insurgent groups. Estimates vary, but most sources agree that over 100,000 people had been killed in the fighting by late 2013. A significant number of the causalities are civilians, although the exact percentage is impossible to ascertain at this point. Additionally, over two million people have been forced out of the country as refugees and another four million have been displaced within Syria.

The conflict has become increasingly sectarian in nature along ethnic-religious lines. The government and its military/security forces are dominated by members of Syria’s Alawite minority group, who make up around 12% of the country’s population. The bulk of the rebel fighters are drawn from the country’s Sunni Arabs, who represent about 60% of the population. This relatively straightforward dynamic has grown increasingly complicated over the last year. It is now clear that Iranian Special Forces and Hezbollah fighters from neighboring Lebanon are directly engaged in the fighting on behalf of the government, instead of merely providing training and assistance. The rebel groups remain diverse and inchoate, but some sorting out has occurred since late 2012. Ominously, a substantial number of opposition fighters appear to have coalesced under the leadership of hard line Islamist factions. These factions also attract a small but steady stream of foreign jihadist fighters. Most news reports from the frontlines portray these Islamist groups as the most effective and brutal units opposing the government.

Military situation in Damascus region as of 15th of September

Partly in reaction, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar have stepped up efforts to supply more moderate rebel groups, although there is no indication either country will become directly engaged in the fighting. As if this situation is not complicated enough, Sunni Kurds, who comprise up to 10% of the country’s population, have basically established a proto-state across much of north central and northeastern Syria along the Turkish border, even forcibly ejecting some Islamist groups from the area. It is hardly surprising that reports indicate many members of Syria’s smallest minority groups, such as the Druze and Christians, have left the country. The occasional Israeli air strike falls into the mix as well.

A year ago, it seemed highly improbable that government forces would fully suppress the revolt. That assessment seems equally valid today, although it is something of a surprise that the government managed to re-take substantial rebel-held territories, especially around Damascus and the corridor connecting the capital with the Alawite-dominated areas along the Mediterranean coast. There are various reasons for this reversal of fortune, such as the continued factional nature of the opposition and the government’s advantages in military equipment, but the key factor seems to have been the intervention of Iran and Hezbollah.

Yet it seems unlikely government forces will be able to reclaim the entire country. The resulting stalemate has effectively partitioned Syria into an archipelago of enclaves controlled by the government or one of the competing rebel groups. The population also seems to be sorting itself out, with great violence, into a patchwork of ethnic-religious enclaves. Indeed, a recent column in the New York Times caused considerable debate when it speculated that Syria would devolve into three ethnic-based states: Alawitestan, Kurdistan, and Sunnistan. A formal partition of the country is a long way off though, given the apparent determination of all sides to continue the fight and the international community’s general reluctance to get more involved.

This scenario was readily apparent last year, as was a sudden collapse of the regime if a significant segment of the Alawite plutocracy abandoned their allegiance to al-Assad. President Obama had previously declared that the use of chemical weapons by government forces would be a ‘red line’ triggering a robust US response. After several small chemical gas attacks, al-Assad’s troops finally launched a substantial chemical attack on rebel-held neighborhoods on the outskirts of Damascus. It seemed that red line had been thoroughly breached, but it was soon apparent that Obama did not really want to follow through with his threat. He also faced majority opposition both in Congress and among the general public. Russian President Putin unexpectedly provided a face saving compromise whereby the United States agreed not to enforce its red line in return for the Syrian government promising to give up its chemical weapons. In what is surely one of the oddest turns of events in diplomatic history, the United States managed to look indecisive, Russia managed to capture some of its superpower glory, and al-Assad won de facto international sanction to continue his murderous ways so long as his butchery is carried out with conventional instead of chemical weapons.

Syria is an excellent candidate for Place of the Year, because in a deeply visceral and tragic way, it continues to illustrate several basic characteristics of our early twenty-first century world: an increasingly multipolar international system, societies assuming a more inward focus in response to a global economic downturn, and the persistence of ethno-nationalist antagonisms often simmering beneath the veneer of nation-state sovereignty. The so-called Arab Spring revolutions were initially accompanied by great excitement that the region was on the verge of momentous change as freedom would sweep across the regime. Several years later, it appears that the greater Middle East is more likely to be embroiled by years of conflict and upheaval. Perhaps the greatest question facing the region is whether Syria will continue to implode, or whether the violence devastating the country will eventually explode beyond its borders?

Joshua Hagen is Professor of Geography at Marshall University. He is the co-editor of Borderlines and Borderlands: Political Oddities at the Edge of the National State (with Alexander C. Diener), author of Preservation, Tourism and Nationalism: The Jewel of the German Past, and co-author of Borders: A Very Short Introduction.

What should be Place of the Year 2013?

SyriaTahrir Square, EgyptRio de Janeiro, BrazilThe NSA Data Center, United States of AmericaGrand Canyon, Greenland

View Result

Total votes: 176Syria (49 votes, 28%)Tahrir Square, Egypt (19 votes, 11%)Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (39 votes, 22%)The NSA Data Center, United States of America (30 votes, 17%)Grand Canyon, Greenland (39 votes, 22%)

Vote

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The milestone Twentieth Edition is full of crisp, clear cartography of urban areas and virtually uninhabited landscapes around the globe, maps of cities and regions at carefully selected scales that give a striking view of the Earth’s surface, and the most up-to-date census information. The acclaimed resource is not only the best-selling volume of its size and price, but also the benchmark by which all other atlases are measured.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Military situation in Damascus region as of 15th of September by Sergey Kondrashov via Wikimedia Commons. Made available through Creative Commons.

The post Place of the year 2013: Spotlight on Syria appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2013: Behind the longlistPlace of the Year: History of the Atlas

Related StoriesAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2013: Behind the longlistPlace of the Year: History of the Atlas

Does Mexican immigration lead to more crime in US cities?

Since 1980, the share of the US population that is foreign born has doubled, rising from just over 6% in 1980 to over 12% in 2010. Compounding this demographic shift, the share of the foreign born population of Mexican origin also doubled, leading to a quadrupling of the fraction of US residents who are immigrants from Mexico. The vast majority of recent migrants of Mexican origin living in the United States are thought to be undocumented leading to a contentious policy debate concerning the collateral consequences of this particular type of immigration.

Over the same time period, crime rates in cities across the United States have declined considerably, in many cases, reaching historic lows. While the aggregate time series suggests that increases in immigration from Mexico has had a protective effect on crime, public opinion has generally reached the opposite conclusion, with a majority of US natives indicating a belief that immigration is associated with increases in criminal activity.

Theory offers little guidance in sorting out the effect of either immigration generally or Mexican immigration specifically on crime. On the one hand, immigrants possess demographic characteristics which, in the general population, appear to be positively associated with crime. In particular, they are more likely to be young and male and have lower earnings than other US residents. Likewise, immigrants may have less attachment to the communities in which they live and have different risk profiles than natives. On the other hand, there is a multitude of evidence that immigrants are positively selected on the basis of ability, face higher costs of punishment and bring with them abundant social capital that is protective of participation in crime.

From an empirical standpoint, the relationship between immigration and crime is difficult to identify because just as immigrants may affect US crime rates, the presence or absence of criminal networks may have a corresponding pull on the level of immigration. Essentially immigration to US cities is hardly random. If we could transform the United States into a research laboratory, what we would like to be able to do is assign each US city a different number of migrants in each year and then observe what happens to that city’s crime rate. Such a research design is motivated by the concept of the randomized controlled trial in medicine – the idea that we can draw inferences about the efficacy of a treatment or a drug by randomly assigning patients to either take the drug or take a placebo pill. Since such an exercise is not feasible with respect to immigration, the next best thing is to find natural variation that closely approximates such an experiment.

In order to identify the effect of immigration on crime, my research leverages two empirical regularities with respect to Mexican immigration to the United States. First, migrants from a given Mexican state tend to settle in US cities that have longstanding cultural ties to that state. For example, migrants from states in eastern Mexico have tended to settle in cities in Texas and the Midwest. On the other hand, migrants from western Mexico have tended to settle in California. Second, migrants tend to be drawn disproportionately from regions of Mexico that are heavily reliant on agriculture. As a result, they are more likely to migrate to the United States in the aftermath of sufficiently extreme weather variation – in particular, extreme rainfall.

As it turns out, weather variation in different Mexican regions has implications for the magnitude of historical flows of migrants to US cities. In particular, US cities experience increases in Mexican migration when Mexican states to which they are culturally linked experience highly variable rainfall. Accordingly Mexican rainfall acts like a random assignment mechanism that assigns a different number of annual migrants to each US city.

When I examine the relationship between rainfall-induced Mexican migration and crime in US cities, I find little evidence of any relationship between the two variables. While these findings do not rule out the possibility that certain US cities experience crime that is disproportionately perpetrated by immigrants, any such effects would appear to be highly localized. This research contributes to a growing literature that finds little evidence of negative collateral consequences of immigration to the United States.

Aaron Chalfin is an Assistant Professor in the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati. His current research examines the effect of police on crime and the extent to which there is a relationship between crime and unauthorized immigration. His past research has considered both the cost and deterrent effect of capital punishment, the relationship between unemployment and crime and the degree to which DNA evidence can be used to solve residential burglaries. He is the author of “What is the Contribution of Mexican Immigration to U.S. Crime Rates? Evidence from Rainfall Shocks in Mexico” (available to read for free for a limited time) in American Law and Economics Review.

The American Law and Economics Review is a refereed journal which maintains the highest scholarly standards and that is accessible to the full range of membership of the American Law and Economics Association, which includes practising lawyers, consultants, and academic lawyers and economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A photograph of the May 1st, “Day without an Immigrant” demonstration in Los Angeles, California. © elizparodi via iStockphoto.

The post Does Mexican immigration lead to more crime in US cities? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!Foreign direct investment, aid, and terrorismThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice

Related StoriesRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!Foreign direct investment, aid, and terrorismThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice

Top five buildings of Empire

All around the world the British built the urban infrastructure that still dominates towns and cities, as well as developing complex transport networks and the ports and railway stations that gave access to them. The Empire’s creation of cityscapes and lines of communication is easy to overlook, so much has it become part of the fabric of the world in which we live that it has been rendered unremarkable. So, too, is the impact of colonization on the natural world, the manner in which settlers and colonial states could alter land use, crop and livestock landscapes, and introduce entirely new species of flora and fauna through their botanical gardens and experimental stations. I thought it would be interesting to explore definitive themes in the history of British imperialism, using each building as a means of doing so.

Fort St Angelo, Grand Harbour, Malta

A squat medieval fort built by the Knights of St John, jutting out into Malta’s spectacular Grand Harbour, this ancient structure was taken over by the British when Malta became their main naval station in the Mediterranean. For the first century of British rule in Malta St Angelo served as an armoured redoubt in anticipation of an enemy attack on the prime naval facilities of Grand Harbour. Shortly before the First World War it was taken over by the navy and became the headquarters of the Mediterranean Fleet, rechristened HMS St Angelo, sprouting wireless masts, the tower of a new desalination plant, Bofors guns, and accommodation and office facilities for hundreds of clerks, officers, and naval ratings. Through an exploration of Fort St Angelo, the role of naval power and sea lines of communication in the history of the British Empire is explored.

Fort St Angelo as seen from the Grand Harbour.

Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation headquarters, Statue Square, Hong KongAt the time of its construction in the early 1980s, Sir Norman Foster’s gleaming glass and steel skyscraper was the most expensive building in the world. Employing innovative construction techniques, such as prefabrication of key components overseas before assembly in Hong Kong, and featuring giant pods hung from steel girders, it dominates Statue Square, Hong Kong’s central space looking out across Victoria Harbour towards Kowloon and the Chinese mainland. It contrasts strikingly with earlier colonial architecture and forms a central feature in the dramatic skyscraper shoreline of Hong Kong island, set against the mountainous Victoria Peak. By examining the history of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC), one can discover the role of commerce and finance in the expansion of British interests in East Asia.

Sir Norman Foster’s gleaming glass and steel skyscraper contrasts strikingly with earlier colonial architecture in Statue Square, Hong Kong.

The Raffles Hotel, Singapore

A colonial era classic and modern day landmark, a visit to the Raffles Hotel transports us to the world of the itinerant Europeans who traversed the Empire’s sea lanes and the lavish lifestyle of the colonials, and charts the fascinating history of this island colony-cum-nation. Despite being so redolent of the colonial period, Raffles was never a British establishment, founded by Armenians and only once in its history managed by a Briton. The Raffles story, from beachside bungalow to national icon, spans a century and a half of mixed fortunes for the entrepôt colony and latter day city-state. From its interwar peak as a world-renowned hotel and “roaring twenties” social centre for Singapore society and upcountry planters, Raffles went into decline and insolvency. Plans to knock it down and erect a skyscraper hotel in its place were developed in the 1970s, before an inspired plan to redevelop the hotel and trade on its iconic status, blending tradition, nostalgia, and modernity, was put into place.

Raffles Hotel, Singapore.

Wembley Stadium, LondonThe famous twin-towers of the Wembley Stadium demolished in 2002-03 echo the architecture of Lutyen and Baker’s New Delhi. Known until the 1970s as the Empire Stadium, it was built as the centrepiece of the 264-acre British Empire Exhibition of 1924. Erected in time to host the 1923 FA Cup Final, it gradually became the national stadium, the scene of countless cup finals and other sporting and ceremonial events. The story of Wembley encompasses the expansion of suburban London and extension of the underground railway system along the Metropolitan Line, and is linked to the development of ceremonial spaces in the city for the performance of imperial and royal events and the hosting of exhibitions. These exhibitions, dating from the Great Exhibition of 1851, became a regular feature in London, and Wembley Stadium was the centrepiece for the biggest of them all.

Wembley Stadium’s distinctive twin towers, as seen in 2008.

The Gordon Memorial College, Khartoum, SudanThe British propagated educational institutions all over the world in the form of universities and schools modelled on Oxbridge and the English public school. Shortly after defeating the Mahdi’s army in 1898 and conquering the Sudan for the Empire, General Kitchener launched an appeal to raise £100,000 to found a college in memory of General Charles Gordon and in order to “civilize” the people. What emerged was a handsome building on the banks of the Blue Nile, as the British created an entirely new city, Khartoum. Running the school as a breeding ground for a British-leaning Sudanese elite proved to be more difficult, however, and the Gordon Memorial College became an incubus of nationalism. Today it is at the heart of the University of Khartoum.

Gordon Memorial College in 1906.

Ashley Jackson is Professor of Imperial and Military History at King’s College London, and a Visiting Fellow of Kellogg College, Oxford. He is the author of numerous books and articles on the history of the British Empire, including Buildings of Empire and The British Empire: A Very Short Introduction.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1) Fort S. Angelo (Birgu, Malta) seen from the Grand Harbour, by Sudika, via Wikimedia Commons 2) Statue Square, Central, Hong Kong, by Choangsoui, via Wikimedia Commons 3) Raffles Hotel, by Mat Honan, via Wikimedia Commons 4) Wembley Twin Towers, retouched by Hic et nunc, original photograph by Nick, via Wikimedia Commons 5) A view from across a street of Gordon Memorial College in 1906, copyright Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA), Identifier: 20979, via Wikimedia Commons

The post Top five buildings of Empire appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesPicturing printingWhen did Oxford University Press begin?

Related StoriesA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesPicturing printingWhen did Oxford University Press begin?

November 17, 2013

Looking forward to AAR/SBL 2013

With a little under one week until American Academy of Religion/Society for Biblical Literature 2013, a lot of us at the Oxford University Press office are getting excited to head to Baltimore. As to what we’re all looking forward to, that varies, from new products, to meeting authors, to food we can’t wait to try. Personally, I can’t wait to find out what the official conference hashtag will actually end up being (#AARSBL? #SBLAAR? #AAR2013? #WOOBALTIMORE??). Read on for what we’re most looking forward to at AAR/SBL 2013, and let us know what you’re looking forward to in the comments.

Oxford’s booth from American Academy of Religion/Society for Biblical Literature 2012. Photo courtesy of Theo Calderara.

Robert Miller, Higher Education:

“I’m excited about the meeting because our Higher Education Group has two major first edition textbooks for some of the core courses in the college Religious Studies curriculum. For the World Religions course we have published Brodd’s Invitation to World Religions. The book is off to a super reception, with people especially praising the way the parallel chapter structure helps students compare religious traditions as well as its emphasis on the lived religious experience. Also, we’re delighted to finally have a new Introduction to the Bible (both the Old Testament and New Testament) by the New York Times best-selling author Bart Ehrman.”

Marcela Maxfield, Academic/Trade:

“This year’s AAR will be my first time going to a conference for work, and I’m excited to experience it. I’m especially looking forward to Baltimore crab cakes.”

Trish Thomas, Journals:

“A visit to the Visionary Art Museum is a must do!”

A superb Assistant Editor, Academic/Trade:

“I’m really looking forward to meeting the authors I work with in person and matching faces to names. Also, it’s always fun to hear about what new projects people are working on, and to talk to new authors about their book proposals. And of course I always enjoy spending twenty minutes helping a grad student track down a monograph that turns out to have been published by Cambridge.”

Alyssa Bender, Academic/Trade and Bibles:

“I love going to conferences—meeting our authors face to face is such a rare occurrence, and as I’ve only met about three of my religion authors in person before, I’m really looking forward to it. This will also be my first conference I’ve attended where we had more than one or two booths (holla, ICMS/AAS/MESA/ASEEES/LSA!) and I’m sure it’ll be crazy at times, but I can’t wait.”

We hope to see you at Oxford University Press booth 829! We’ll be offering the chance to:

Check out which books we’re featuring.

Browse and buy our new and bestselling titles on display at a 20% conference discount

Get free trial access to our suite of online products for a month.

Pick up sample copies of our latest religion journals.

Enter giveaways for free OUP books.

Meet all of us cool people.

See you there!

Alyssa Bender is a marketing associate in the Academic/Trade and Bibles divisions and can’t wait to go to her first AAR.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Looking forward to AAR/SBL 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIs it a dog’s world?Stan Lee on what is a superheroElinor Ostrom and institutional diversity

Related StoriesIs it a dog’s world?Stan Lee on what is a superheroElinor Ostrom and institutional diversity

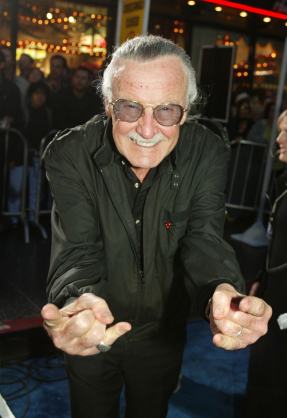

Stan Lee on what is a superhero

What is a superhero? What is a supervillain? What are the traits that define and separate these two? What cultural contexts do we find them in? And why we need them? Editors Robin S. Rosenberg, PhD and Peter Coogan, PhD collected a series of essays examining these questions from both major comic book writers and editors, such as Stan Lee and Danny Fingeroth, and leading academics in psychology and cultural studies, such as Will Brooker and John Jennings. The following essay by legendary comic book writer, editor, publisher, and producer Stan Lee is extracted from What is a Superhero? and entitled “More Than Normal, But Believable”.

A superhero is a person who does heroic deeds and has the ability to do them in a way that a normal person couldn’t. So in order to be a superhero, you need a power that is more exceptional than any power a normal human being could possess, and you need to use that power to accomplish good deeds. Otherwise, a policeman or a fireman could be considered a superhero. For instance, a good guy fighting a bad guy could be just a regular police story or detective story or human-interest story. But if it’s a good guy with a superpower who is fighting a bad guy, it becomes a superhero story. If the good guy is doing something that a normal human being couldn’t do, couldn’t accomplish, then I assume he becomes a superhero.

Not surprisingly, then, the first thing I would think of when trying to create a character is, what superpower will I give him or her? I’ll make somebody who can throw fireballs and fl y in the air. I’ll have somebody who can crawl on walls and shoot webs like a spider. So, automatically, those characters become superheroes. Of course, if they were evil, they would be supervillains, because the same rule applies: to be a supervillain, you have to be a villain, but you also have to have a superpower, just like a superhero has to. The word super is really the key.

But there’s no formula for creating characters. With Iron Man, I knew I wanted someone in an iron suit, and so his powers came from that. With Spider-Man, I knew I wanted someone with spider powers, so the name and costume came with that. It doesn’t matter whether you start with the character’s code name, his powers, or his costume; none of these conventions of the genre works better than the others as a starting place for creating a superhero. It just depends on whether you get lucky and what sells.

But there’s no formula for creating characters. With Iron Man, I knew I wanted someone in an iron suit, and so his powers came from that. With Spider-Man, I knew I wanted someone with spider powers, so the name and costume came with that. It doesn’t matter whether you start with the character’s code name, his powers, or his costume; none of these conventions of the genre works better than the others as a starting place for creating a superhero. It just depends on whether you get lucky and what sells.

There doesn’t necessarily have to be a connection between the personality of the alter ego and the powers of the superhero. When we created the Fantastic Four, I knew that I wanted each of them to have distinct powers. Even though Reed is mentally bright and flexible, Johnny is a bit of a hothead, Sue is a shrinking violet, and Ben is a big lug—which fi ts with their powers—I could have made Sue go on and on and speak with big words, or made Johnny the intellectual, or given Reed a temper. The powers of the characters don’t necessarily have to reflect the personalities of the characters, and the Fantastic Four would have been just as successful if there had been no link between their personalities and their powers. It just depends on how it works out. That’s the way things were back then.

The problem with telling superhero stories is that it naturally follows that you need a supervillain. You need a foe who can make the story interesting, someone who’s at least as powerful as—and hopefully even more powerful than—the hero, because that makes the story fun. The viewer or the reader has to think to himself or herself, how is our hero ever going to get out of this? How is he ever going to beat the villain? We have to keep the reader on the edge of his or her seat. So the most important thing is to have a supervillain who is equally as colorful as and even more powerful than the hero apparently is.

I try to make the characters seem as believable and realistic as possible. In order to do that, I have to place them in the real world, or, if the story is set in an imaginary world, I have to try to make that imaginary world as realistic-seeming as possible, so the character doesn’t exist in a vacuum. He has to have friends, enemies, people he’s in love with, people he doesn’t love—just like any human being. I try to take the superhero and put him in as normal a world as possible, and the contrast between him and his power and the normal world is one of the things that make the stories colorful and believable and interesting.

Superman was the start of the whole superhero thing. He had the superpowers and wore that costume with the bright colors and silly cape. It’s the costume that was different. Zorro didn’t have superpowers, Doc Savage * didn’t have superpowers; they could just do things a little better than the rest of us. The Shadow † could be a superhero because he could make himself unseen, and if he appeared in a comic book today, he might be a superhero, though he doesn’t really wear a costume. I’m not an expert on the Shadow, but I think he just had a dark business suit and a sort of raincoat and a slouch hat. Superman’s costume was different because of the bright colors, that silly cape, those red boots, his belt, and his chest symbol. I mean, it’s ridiculous, because you really don’t need a costume to fly or fight bad guys. If I had superpowers, I wouldn’t wear a costume.

But it does serve as a way of colorfully identifying the superhero, and it also announces him. When he gets into a fight with a bad guy, the costume sort of explains that he’s the good guy.

Although a costume isn’t required of superheroes, the fans love costumes. The characters are more popular if they wear costumes. (Don’t ask me why.) In the first issue of the Fantastic Four, I didn’t have them wear costumes. I received a ton of mail from fans saying that they loved the book, but they wouldn’t buy another issue unless we gave the characters costumes. I didn’t need a house to fall on me to realize that—for whatever reason—fans love costumed heroes.

I think people are fascinated by superheroes because when we were young we all liked fairy tales, and fairy tales are stories of people with superpowers, people who are super in some way—giants, witches, magicians, always people who are bigger than life. Well, as we got older, we outgrew fairy tales. Most people don’t read fairy tales when they’re grown-ups, but I don’t think we ever outgrow our love for those kinds of stories, stories of people who are bigger and more powerful and more colorful than we are. So superhero stories, to me, are like fairy tales for grown-ups. I don’t know why, but the human condition is such that we love reading about people who can do things that we can’t do and who have powers that we wish we had.

* * * * *

* Editors’ note: Doc Savage is Clark Savage, Jr., a pulp adventurer whose adventures were published by Street and Smith from 1933 to 1949 and who has seen numerous paperback and comic book revivals. He is also the subject of a campy 1975 feature film, Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze, starring Ron Ely.

† The Shadow is a dark pulp vigilante who debuted in 1931 and went on to be the subject of a radio series, movie serials, paperbacks, comics, and a feature film. On radio he was voiced by Orson Welles and other actors, and he was played by Alec Baldwin in the 1994 film. He is often depicted as having the power to “cloud men’s minds” in order to be invisible. Writer Bill Finger was influenced by the depiction of the Shadow when he co-created Batman.

Stan Lee’s name is practically synonymous with the word “superhero.” He co-created many famous superheroes during his time at Marvel Comics: the Incredible Hulk, the Fantastic Four, Thor, Spider-Man, Iron Man, and the X-Men, among many others. Stan imbued his characters and stories with an element of psychological realism, making it easy for fans to relate to the characters and their plights. Stan became an editor at Marvel when he was 19 years old and went on to become its publisher. Stan continues to create new superheroes under the banner of his POW! Entertainment company.

Robin S. Rosenberg, PhD and Peter Coogan, PhD are the editors of What is a Superhero? Robin S. Rosenberg is a clinical psychologist. In addition to running a private practice, she writes about superheroes and the psychological phenomena their stories reveal. Peter Coogan is director of the Institute for Comics Studies, co-founder and co-chair of the Comics Arts Conference, and an instructor at Washington University in St. Louis.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only arts and leisure articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Stan Lee on what is a superhero appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesInternational Day for Tolerance: A Q&A with Amos N. GuioraWorn out wonder drugsCharacters from The Iliad in ancient art

Related StoriesInternational Day for Tolerance: A Q&A with Amos N. GuioraWorn out wonder drugsCharacters from The Iliad in ancient art

Elinor Ostrom and institutional diversity

The issue of institutional diversity, a key theme in the work of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics co-recipient, Elinor Ostrom, is one of the major challenges confronting national states and global governance in our time. How can viable governance structures accommodate the persisting diversity of communities and societies? There is an intensifying heterogeneity of beliefs, values, identities, preferences and endowments clashing in a world transformed by globalization and an ongoing technological revolution. From global resources management and the “clash of civilizations” to municipal governance and community development, the social fact of “heterogeneity” is a constant source of social dilemmas, public choice, and collective action problems. Diverse values, identities, principles, and cultures clash in the global arena. Migration, increasing diverse populations inside nation-states, demographical and cultural trends: all challenge current governance systems not only at the global level but also, increasingly, at the local level. Technology itself generates new cleavages and communities, subcultures and identities. All these push to the forefront the problem of the possible institutional solutions, with an unprecedented intensity.

Elinor Ostrom. © Holger Motzkau 2010, Wikipedia/Wikimedia Commons (cc-by-sa-3.0)

In order to confront the problem of heterogeneity, social theorists have usually advanced a strategy of “homogenization” by assumption. Yes, the argument says, heterogeneity — the diversity of human preferences, values, beliefs perceptions and endowments — is a problem but fortunately, hidden within diversity is a really deeper focal point or functional principle that all social actors share. By focusing on their common focal point (rationality, human nature, empathy, moral sentiments etc.) diversity may be in the end circumvented, neutralized, normalized. In our theories, they say, we should base our approach on that focal point and progressively shift our main focus away from the issue of diversity.Yet, this strategy is ultimately deeply unsatisfactory, especially when it comes to its applied implications. The presence of resilient and widespread heterogeneity-related problems at each turn in practical affairs, reminds us that this strategy has — for practical purposes — a rather limited feasibility domain. What happens when we move from ideal-theory to real life situations; when “normalization” and “homogenization” are not viable alternatives? What happens when “consensus” does not exist? Is good or decent governance still possible between individuals sharing less and less beliefs, values, identities, and objectives? How far could a society or social system go in the direction of heterogeneity, still hope to achieve social coordination and cooperation, and be able to solve basic collective action and public administration problems?

Elinor Ostrom and her collaborators have opened up important lines of inquiry that have the potential to address these and related problems. They have explored the multiple ways how viable institutional arrangements are created and recreated by various communities in various circumstances all over the world. They analyzed how institutional diversity, organized in polycentric systems of multiple decision centers and overlapping jurisdictions, may offer possible solutions to the huge governance challenges created by heterogeneity. They pointed out that social heterogeneity and institutional diversity are two facets of the same phenomenon and governance formulas should acknowledge that reality. We need to go beyond the “one form, one size fits all” approach, beyond the institutional design views based on two and only two models: the state and the market.

Elinor Ostrom’s explorations into the domain of institutional diversity are addressing in a concrete and practice-relevant manner the measure in which it is possible to have an institutional order defined by freedom, justice, and peace. In an increasing interdependent world of diverse and conflicting beliefs, values and objectives, how is institutional diversity a possible solution? This is a discussion about the fundamental nature of governance (both domestic and international) in the new era; we are at the core of the major political and economic challenges of our age. At the same time, we are at the cutting edge of contemporary social science and political philosophy. The empirically grounded, applied institutional analysis of the possibility of governance in extreme conditions seems to be indeed defining a new intellectual and policy frontier. The pioneering work of Elinor Ostrom and her collaborators has made this possible.

Paul Dragos Aligica is a Senior Research Fellow in the F. A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, where he teaches in the graduate program of the Economics Department. He received his PhD in Political Science at Indiana University-Bloomington, where he was a student of Vincent and Elinor Ostrom at the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. He is the author of five books, including Institutional Diversity and Political Economy: The Ostroms and Beyond, and numerous academic articles on institutional theory, public affairs, and political economy themes.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Elinor Ostrom and institutional diversity appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive most influential economic philosophersUrban warfare around the globe [interactive map]Seven historical facts about financial disasters

Related StoriesFive most influential economic philosophersUrban warfare around the globe [interactive map]Seven historical facts about financial disasters

Worn out wonder drugs

It is undeniable that the discovery of antibiotics changed modern medicine. However, from their mass production in 1943, antibiotics have gone from being dubbed the wonder drug to being an issue of serious global concern. Microbial resistance to antibiotics was first documented just four years after they were mass-produced. Seventy years later the picture looks bleak. Bacteria have developed resistance to all known antibiotics. Today we have bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics and we are fast approaching a time when antibiotics just won’t work on some bacterial infections. The economic burden associated with these multidrug-resistant bacteria is high, estimated to cause an economic loss of more than €1.5 billion each year in the EU alone.

There are lots of different and complex reasons for the increase in antibiotic resistance but one thing is clear: antibiotic use is associated with resistance. Antibiotics have been so effective at treating infections that we overuse and misuse this medication, resulting in bacterial resistance. You could say that antibiotics are suffering from their own success!

But if we’ve caused the problem, can we fix it? We can slow the process down by using the antibiotics we have more responsibly, buying us time to develop more antibiotics. The public play an important role in this process, but recent studies show that there is still public misunderstanding about the activity of antibiotics against microbes and their responsible use. The 2010 Eurobarometer survey found that 83% of respondents across Europe were aware that taking too many antibiotics makes them ineffective, yet the main reason given by respondents for taking antibiotics is to treat flu or a cold — regardless of the fact that antibiotics do not kill viruses.

The burden of antibiotic resistance is of global importance, so the United States, Europe, Canada, and Australia address the issue of public misunderstanding through international collaboration. Each run an annual public health initiative in November. The united aim of each of these campaigns is to encourage health professionals and the wider community to learn more about antibiotic resistance and the importance of taking these life-saving medicines appropriately. England, for example, has undertaken numerous campaigns to encourage the public to ask for fewer antibiotics and make GPs more aware of their prescribing behaviour, but the total number of antibiotics prescribed has still gone up by 12% in the past five years.

Antibiotics are the most common medication prescribed, and most public awareness campaigns tend to focus on adults, who are the gatekeepers to antibiotic use, yet antibiotic prescription rates are high in children. Few initiatives have targeted children and young people, who are our future generation of gatekeepers and prescribers. Teaching children and young people about the different types of microbes (bacteria and viruses) and the increasing problems of antibiotic resistance associated with unnecessary antibiotic use may not only raise awareness of the issue and influence their future prescribing habits, but may also raise the issue of resistance in the family environment as these children take the messages home to their parents. Various school hygiene campaigns have been shown to reduce rates of infection in schoolchildren, staff, and families, and this in turn may reduce antibiotic use.

That being said, school education on antibiotics and antibiotic resistance is poor and varies across Europe from country to country. The information provided to schoolchildren on antibiotics is limited at junior schools, but taught in more detail at the senior level. Education on antibiotic resistance is sparse, with few countries teaching that antibiotic resistance is a serious problem. Eurobarometer findings showed that 15-24-year-olds were the least informed but highest users of antimicrobials. On a positive side, it also showed that they were the most likely age group to change their minds on antibiotic use after receiving information about it. Young people in this age group are also establishing their independence and starting to visit their GP without parental support. Combine this with the fact that antibiotic resistance has been deemed a greater threat than terrorism, it’s fair to surmise that school education on antibiotics and resistance should be viewed as essential. The prudent use of antibiotics can help stop resistant bacteria from developing and keep antibiotics effective for future generations, so we really need to teach our future generation about responsible antibiotic use with educational initiatives, such as e-Bug.

Donna M. Lecky is the co-author of ‘Current initiatives to improve prudent antibiotic use amongst school-aged children’ with Cliodna A. M. McNulty is published in Volume 68, Issue 11 of Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. The paper is freely available as part of a special collection of Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy articles to mark European Antibiotic Awareness Day on 18 November 2013. Dr Lecky is Project Manager, Primary Care Unit, Public Health England. She has managed and developed resources for the European e-Bug project and currently acts as the e-Bug international relations officer as well as leading on other research projects. She has also worked on various public health campaigns and primary care initiatives involving hygiene, infection prevention and antimicrobial stewardship and acts as an external expert on Hygiene Education in Schools for the International Federation of Home Hygiene.

The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy is among the foremost international journals in antimicrobial research. Readership includes representatives of academia, industry and health services, and includes those who are influential in formulary decisions.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bacteria growing in a blood plate petri dish on white background. © hisartwork via iStockphoto.

The post Worn out wonder drugs appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!Depression in older adults: a q&a with Dr. Brad Karlin

Related StoriesAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!Depression in older adults: a q&a with Dr. Brad Karlin

November 16, 2013

Characters from The Iliad in ancient art

The ancient Greeks were enormously innovative in many respects, including art and architecture. They produced elaborate illustrations on everything from the glorious Parthenon to a simple wine cup. Given its epic nature and crucial role in Greek education, many of the characters in the Iliad can be found in ancient art. From the hero Achilles to Hector’s charioteer, these depictions provide great insight into Greek culture and art. Here’s a brief slideshow of images from Barry B Powell’s new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer which depict many of the prominent characters.

Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 20.1 - The beardless youthful warrior is labeled ACHILL EUS. Dressed in a diaphanous shirt beneath a breastplate decorated with a Gorgon’s head, he stands looking off pensively to his left. In his left hand he holds a long spear over his shoulder, his right hand propped on his hip. A cloak is draped over his left arm and a sword in a scabbard hangs from a strap that crosses his chest and rests at his side. He has no helmet, shield, or shinguards. On the other side (not visible) a female, probably Briseïs, holds the vessels for a drink-offering. Athenian red-figure water jar by the

Achilles Painter, c. 450 bc.

Briseïs

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 19.2 - Briseïs is dressed in an elegant gown and smells a flower. Two sides of an Athenan red-figure water jug by Oltos, c. 510 bc.

Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 19.2 - Achilles stands armed with a spear, sword, helmet, shinguards, and breastplate. Two sides of an Athenan red-figure water jug by Oltos, c. 510 bc.

Kebriones

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 16.3 - Hector’s charioteer mounts his chariot before being killed by Patroklos. Hector, holding a spear and wearing a robe, and an armed companion stand to the left of the chariot; Glaukos, holding a spear and wearing a similar robe, and an armed companion stand to the right. Kebriones is in the chariot. The figures are labeled. It is a four-horse chariot, which never appears in Homer, unless the outside horses are trace-horses. Athenian black-figure wine-jug, c. 575–550 bc.

Patroklos and Achilles

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 16.1 - The younger, beardless Achilles wraps a bandage around the arm of his older, bearded friend. Achilles is in full armor, but without shinguards.

Patroklos, who looks away in pain and squats on a shield decorated with a tripod (?), carries a quiver and bow on his back. He wears a felt cap. An arrow lies parallel to his calf. There is no such scene in the Iliad, but the painting was inspired by the intimacy of the two men and modeled on the scene where Patroklos binds the wounds of Eurypylos. Athenian red-figure wine-cup (kylix) by Sosias found in Vulci, Italy, c. 500 bc.

Kastor and Polydeukes

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 9.2 - The brothers of Helen (probably) attack the Kalydonian Boar. The fish beneath the ground-line indicates a lake or stream. Spartan black-figure

wine-cup, c. 555 bc.

Hector and Andromachê

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 6.2 - Hector bids farewell to Andromachê and Astyanax. Andromachê, seated in a fancy chair unlike in Homer, wears earrings, a bracelet in the form of a serpent, and a necklace. The boy, wearing an ankle bracelet in the form of a serpent and a headband, stretches to touch his father’s helmet. A beardless Hector, naked from the waist up, holds in his left hand a spear and shield. From a south Italian red-figure wine-mixing bowl, c. 370–360 bc.

Helen and Priam

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 3.1 - The scene is not from the Iliad but inspired by it. Helen is inside—note the column on the left—and pours out wine into a special dish, from which Priam will pour a drink offering. The buxom Helen wears a gown covered by a fine cloak. She pulls the veil away from her face, perhaps to speak. Priam is an old man with a white beard who holds a staff in his other hand. Above him a shield hangs from the wall with a lion blazon, and a sword. Interior of an Athenian red-figure wine cup, c. 460 bc.

Nestor

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fig 2.1 – Gray-haired, he had already seen three generations of men. He wears no armor and holds a staff of authority, appropriate to his role as advice-giver. On an Athenian red-figure vase, c. 450 bc.

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is the author of a new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Characters from The Iliad in ancient art appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaps of The IliadA call to the goddessIs it a dog’s world?

Related StoriesMaps of The IliadA call to the goddessIs it a dog’s world?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers