Oxford University Press's Blog, page 881

November 12, 2013

A gentleman’s tour of Regency London prisons

In eighteenth and early nineteenth-century England, prisons were popular tourist sites for wealthy visitors. They were also effectively run as private businesses by the Wardens, who charged the inmates for the privilege of being incarcerated there. Indeed prisoners from the higher ranks of society, who had the means to pay for better accommodation, routinely expected to be treated better than lower class or “common” criminals. Between 1810 and 1814, William Collins Burke Jackson, the son of a wealthy East India Company merchant, had the great misfortune of being able to sample the amenities offered to young gentlemen within five different penal institutions. Here is a brief tour of three of them.

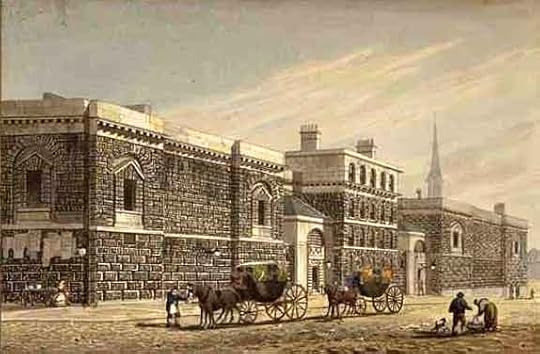

The Fleet Debtors’ Prison

At just nineteen William was arrested by his creditors for debt and conveyed to Number 9 Fleet Market – a deceptively innocuous address that debtors’ used to conceal the fact they were actually residing within the Fleet prison. Visitors to the prison were so numerous that the guards memorised the faces of new inmates on arrival, so they could not walk out with the crowds. The range of accommodation a prisoner was offered depended on an assessment of “his rank and condition”. Rooms could be had on the Common side for poorer men or on the Master’s side for the wealthier, but there was a vibrant trade amongst officers and longer-term inmates eager to rent out rooms, or sub-let beds in them to new “chums” (so called because they had to pay “chummage” to the Warden). William’s accommodation tended to reflect the state of his finances. His father paid him a guinea a week which could provide lodging in a private room on the Master’s side, but when his funds ran low he was reduced to sharing a room without furniture on the Common side, or sleeping on a table in the taproom. He wanted to live outside the prison in an area known as “the Rules”. But it was an expensive privilege that required payment of securities to prevent prisoners crossing the invisible (and elastic) boundaries that ran down the middle of streets and buildings around the Fleet. An additional £5 would procure day release, ostensibly to sort out financial business, but it was more commonly known as “showing you my horse”, a phrase which reflected the more sociable activities made possible by such day trips.

Fleet Prison in 1808.

Newgate PrisonNewgate prison was “of all places the most horrid”, but also highly recommended to tourists by London guide books. Its massive stone walls were built to hold around five hundred prisoners, but it frequently contained nearly double that number. In addition to tourists, there was a large daily influx of visitors: friends and family bringing food, prostitutes (pretending to be wives and paying “bad money” to the turnkeys to stay overnight), attorneys and gangs of thieves. The turnkeys insisted that leg irons were essential to distinguish inmates from visitors; but they also “loaded” prisoners with heavier irons so they could charge to change them for lighter shackles or to remove them for appearances in court. Despite this turnkeys had little control over the prisoners, who made their own rules and conducted mock trials of those that broke them. In 1811 the Warden admitted to Parliament there was “no discipline of any kind in Newgate.” William was at first confined to the Common Side with the “lowest and vilest” wretches who stole most of his clothing, but he eventually persuaded his father to pay for better lodging. Newgate had a Master’s Side where “more decent and better behaved” prisoners could share a proper bed, but the best rooms were on the State Side. Here, those “whose manners and conduct” proved they had received a good education could rent one of twelve rooms, and pay extra for a single bed and better food. Suspected felons were not supposed to be able to take advantage of this privilege, but despite the fact that his client had been charged with the capital crime of forgery, William’s solicitor discovered that payment of an extra guinea removed this obstacle.

”’West View of Newgate”’ by George Shepherd.

“Retribution” Hulk

This aptly named prison hulk was moored on the Thames, close to the Woolwich Arsenal where its inmates were forced to labour while they waited to be transported to Australia. In spring and summer Retribution was a popular destination for tourists, who were curious to view its awful bulk and infamously depraved inmates from the safety of a small boat. From there they could also observe “the multitude of convicts in chains” working on the Warren. Retribution was one of the largest and longest-serving hulks with up to 450 men kept shackled below deck. Of all the hated hulks, this was the one prisoners dreaded most. The death rate on board was more than double that on the other hulks, and the number of attempted escapes was correspondingly high. There was no special accommodation available on board for gentlemen to rent, and William shared the “barley and putrid meat” the other convicts ate, which gave him such serious bowel problems he was sure it would soon “terminate [his] miserable existence”. He slept on straw with the other convicts, and no officers dared descend among them after dark, despite numerous reports of robbery, murder, suicide and “unnatural crimes”. Several attempts to seal off each of the three lower decks to reduce the incidence of crime and disease had failed because the convicts tore down the carpenters’ work every night. Efforts to erect a chapel on board were equally unsuccessful. William’s higher social status did, however, earn him kinder treatment from the ship’s officers. As a gentleman, he could and did seek help from influential friends in high places to gain a royal pardon, or permission to be transported on an earlier ship to Australia, but he was unsuccessful on both counts.

[image error]

The ship “Discovery” beached at Deptford. Like “Retribution”, “Discovery” served as a convict hulk.

Nicola Phillips is an expert in gender history and a lecturer in the department of History and Politics at Kingston University. She is the author of The Profligate Son: Or, a True Story of Family Conflict, Fashionable Vice, and Financial Ruin in Regency England. Her research focuses on eighteenth-century gender, work, family conflict, and criminal and civil law. Nicola is also an advocate of public history, and has contributed to radio and TV programmes on gender history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Aquatint of Fleet Prison from The Microcosm of London or London in Miniature. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Newgate prison. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Discovery” at Deptford. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A gentleman’s tour of Regency London prisons appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford University Press and the Making of a BookBefore Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing cityThe Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Related StoriesOxford University Press and the Making of a BookBefore Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing cityThe Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Before Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing city

‘This Lane is commonly called Pie Lane, but I will call it Winking Lane’. So noted the Christ Church canon, Leonard Hutten, in his perambulatory Antiquities of Oxford, written at some point in the early seventeenth century. He was referring to Magpie Lane, which squeezes past Oriel College’s eastern flank on its way towards Oxford’s High Street. For Hutten, this lane deserved renaming ‘because the first Printing Presse, that ever came into England, was sett on worke in this Lane by Widdy kind, alias Winkin, de Ward [i.e. Wynkyn de Worde] a Dutchman.’

‘This Lane is commonly called Pie Lane, but I will call it Winking Lane’. So noted the Christ Church canon, Leonard Hutten, in his perambulatory Antiquities of Oxford, written at some point in the early seventeenth century. He was referring to Magpie Lane, which squeezes past Oriel College’s eastern flank on its way towards Oxford’s High Street. For Hutten, this lane deserved renaming ‘because the first Printing Presse, that ever came into England, was sett on worke in this Lane by Widdy kind, alias Winkin, de Ward [i.e. Wynkyn de Worde] a Dutchman.’

Hutten was not alone in seeking to claim Oxford as the first printing city of England. Brian Twyne, in Antiquitatis academiae Oxoniensis apologia (1608), makes a similar assertion although he identifies John Scolar rather than de Worde as the city’s first printer. However, the story took on new impetus in the 1660s when Richard Atkyns published an account of how Henry VI and Thomas Bourchier, Archbishop of Canterbury, had conspired to import the new technology of printing in England. In an audacious and expensive plot, a royal official and William Caxton, ‘a Citizen of good Abilities’, travelled abroad to kidnap one of Gutenberg’s workmen, one Frederick Corsells or Corsellis:

’Twas not thought so prudent, to set him on Work at London, (but by the Arch-Bishops means, who had been Vice-Chancellor, and afterwards Chancellor of the University of Oxford) Corsellis was carryed with a Guard to Oxford… So that at Oxford Printing was first set up in England, which was before there was any Printing-Press, or Printer, in France, Spain, Italy, or Germany, (except the City of Mentz)…

As evidence, Atkyns cited a hitherto unknown manuscript in Lambeth Palace as well as Expositio in Symbolum Apostolorum with its famous ‘1468’ Oxford imprint which, if accurate, would have predated Caxton’s first printed books by several years.

Atkyns was far from the disinterested scholar: the story formed part of a rhetorical and legal campaign to assert the primacy of the royal prerogative over the craft of printing in order to shore up Atkyns’s own claim to the patent for the printing of law books. Nonetheless, the Oxford myth proved proved enduring. Anthony Wood’s survey of printing in Oxford in his history of the University (1674) follows Atkyns’s account closely. Joseph Moxon includes the Corsellis story in his account of the origins of printing in Europe which prefaced his famous printing manual, Mechanick Exercises (1683–4). John Bagford’s early eighteenth-century account of Oxford printing also began with Corsellis, as did Samuel Palmer’s General History of Printing (1732). By the mid-century, Shakespeare was even being quoted as evidence: ‘thou hast caused printing to be us’d’ (Henry VI, part 2).

The Corsellis story was not just of scholarly interest. In 1671 Thomas Yate, the Principal of Brasenose College and one of the four ‘partners’ who managed the university printing and published in the 1670s, cited Corsellis, the ‘1468’ imprint, and the 1481 Oxford edition of Expositio super tres libros Aristotelis de anima in a legal defense of the university’s right to printing. In a court case a decade later, the King’s Printer Henry Hills used the same account to argue that his position trumped any printing rights claimed by the University. In a 1691 account of the recent conflict with the London book trade, the Keeper of the University Archives, John Wallis, declared that ‘the Art of printing was first brought into England by the University, and at their Charges; and here practiced many years before there was any printing in London…’ The Oxford story retained sufficient credibility to be cited in the court cases regarding copyright in the 1770s.

It was, though, a complete fabrication. The Lambeth Palace manuscript did not exist and the ‘1468’ imprint was almost certainly a misprint for 1478. Nor, for that matter, did de Worde, Caxton’s successor in London, ever print at Oxford. Nonetheless it would wrong to mock those who made these claims as charmingly naïve or as poor scholars. The Corsellis myth appealed as much to the hard-nosed pragmatist seeking to establish the University’s right to print whatever it liked as to the scholarly idealist who felt that printing’s beginnings in England ought to be found in the universities rather than elsewhere. Moreover, the potency of such beliefs reminds us that there may be other ‘myths’ about scholarly publishing at Oxford that, although not wholly false, deserve to be considered sceptically–whether it’s focusing on the three ‘great men’ of Oxford University Press’s early history (William Laud, John Fell, William Blackstone) at the expense of other important figures; whether it’s mischaracterizing the relationship between the London book trade and the university press as one in which a plucky Oxford repeatedly struggled for its rights against a gang of hostile and avaricious London booksellers; whether it’s forgetting that non-learned books have always been a crucial part of the university press’s output; or whether it’s assuming that the University’s scholarly aspirations as a publisher were repeatedly undercut by commercial imperatives. The history of Oxford University Press is much more complex than the mythology might have us believe.

Ian Gadd is Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University. He is editor of The History of Oxford University Press–Volume 1: From its beginnings to 1780.

To celebrate the publication of the first three volumes of The History of Oxford University Press on Thursday and University Press Week, we’re sharing various materials from our Archive and brief scholarly highlights from the work’s editors and contributors. With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Watch the silent film in our previous post.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of Magpie Lane, Oxford. Photo by Wikipedia user Newton2, 2005. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Before Caxton? Claiming Oxford as England’s first printing city appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOxford University Press and the Making of a BookThe Vietnam Veterans MemorialThe many “-cides” of Dostoevsky

Related StoriesOxford University Press and the Making of a BookThe Vietnam Veterans MemorialThe many “-cides” of Dostoevsky

November 11, 2013

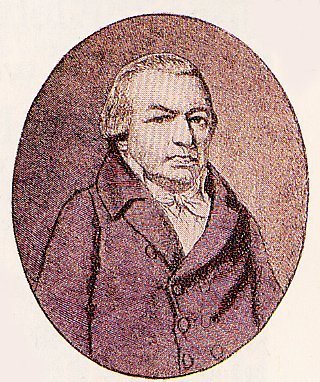

Johann van Beethoven’s last hurrah

Fathers do not always receive the kindest press, but any man who unwittingly produces an icon of western culture will find his parental techniques under an especially harsh spotlight. Such was the fate of Johann van Beethoven, a singer of modest achievements, who ended up dividing his time unequally between the Bonn Hofkapelle and the local taverns. With the exception of Leopold Mozart, no eighteenth-century parent has undergone such scrutiny, and none has emerged from the examination with so little credit. Not to put too fine a point on it, the conclusion was reached early that Johann was a drunken sot whose loutish behaviour had profoundly damaged the young composer.

Marion M. Scott, early champion of women in British musical life, reported in a manner suitable for polite society, an epitaph more generally known in cruder versions: ‘Johann van Beethoven’s sole achievement in life was to have provided a biological link between his father and his son’. It is hard to pour such scorn on a blank canvas, and a candidate image of Johann soon emerged from the ranks of unattributed Bonn portraits. While acknowledging that the sitter remained unidentified, Scott felt able to discern in his image ‘that indefinable coarsening and slackening of the features that follows upon drinking or fast living’. We have been duly warned!

Marion M. Scott, early champion of women in British musical life, reported in a manner suitable for polite society, an epitaph more generally known in cruder versions: ‘Johann van Beethoven’s sole achievement in life was to have provided a biological link between his father and his son’. It is hard to pour such scorn on a blank canvas, and a candidate image of Johann soon emerged from the ranks of unattributed Bonn portraits. While acknowledging that the sitter remained unidentified, Scott felt able to discern in his image ‘that indefinable coarsening and slackening of the features that follows upon drinking or fast living’. We have been duly warned!

Stories of Beethoven’s upbringing were lurid in the extreme. Scott again: ‘One gets the impression of the child prisoned within himself, chained-dog-like, savage with captivity, glowering out from his kennel upon a world that seemed to him infested with fools whom he never learned to suffer gladly.’ It is hard to see this feral wolf-child in the personable young man depicted in 1803 at the start of his career as a society keyboard virtuoso, even though the image captures something of his force of personality and inner reserve.

The mythology was eventually revealed for what it was. Tales of abuse at the hands of drunken Flemings or brutish Saxons, of the weeping child forced to receive his tuition in the early hours, were expunged from the record. Yet there remained the question of the family’s economic circumstances. Maynard Solomon demonstrated that Johann’s alcoholism did not reduce him to outright penury; the picture was rather one of uncertainty, of a family living on the edge, never quite knowing what was going to happen next. When he finally died, the Elector of Bonn acidly observed that his revenues from liquor excise duty were about to take a big hit.

A recently uncovered letter throws additional light on Johann late in life. Its author describes a public opera rehearsal, rating the performers on a scale from good to so-so. He apparently had second thoughts about ‘Bithoven’ whom he first ranked as ‘gut’ (good), but subsequently qualified this with ‘zimlich’ (quite) in the margin. This word can have a negative connotation: only ‘rather’ good, as opposed to simply good. Yet a more positive slant is also possible as in the English ‘actually rather good’ or ‘really rather good’. If the implied thought was that he sang ‘better than might have been expected’, the reason is not hard to imagine.

The opera in which Beethoven’s father appeared was Monsigny’s Le déserteur. The plot revolves around a soldier unjustly imprisoned for desertion whose freedom is obtained only at the last moment. Johann played the father-figure, although in view of his well-known drink problem, one wonders whether consideration was given to type-casting him as the inebriated dragoon Montauciel who imbibes copious amounts, acts in a tipsy fashion, and sings volubly in praise of wine.

The role was not vocally demanding. The character’s only moment in the limelight as a singer comes in the fugal trio at the climax of Act II when the nature of the impending tragedy becomes apparent to all three: the soldier Alexis, Louise his betrothed, and Jean-Louis her father. It was not perhaps Sedaine’s finest moment as a librettist. Louise begins: ‘Heavens above! You’re going to die’. Jean-Louis responds: ‘Heavens above!: he’s going to die!’ Alexis is more sanguine: ‘Oh no! I’m not going to die!’ Monsigny set this as a baroque-style fugue with a regular countersubject. Horrified by what he has done, Jean-Louis insists upon taking the blame; no one but he the father is responsible for the trauma being inflicted upon his family, a reference that can hardly have been lost on Johann’s fellow performers or the audience.

A question that cannot yet be answered is whether the young Beethoven was present to witness his father’s performance. It would be helpful to establish his whereabouts during this period with certainty, but the evidence falls tantalisingly short of allowing a definitive conclusion. That Johann van Beethoven was able to appear on-stage in a public rehearsal with some success seems to confirm the view that the period of his serious decline dates from the death of his wife later that year.

Ian Woodfield is the author of “Christian Gottlob Neefe and the Bonn National Theatre, with New Light on the Beethoven Family” (available free for a limited time) in the most recent issue of Music and Letters. He teaches music at Queen’s University Belfast and has research interests in eighteenth-century opera. His most recent monograph Performing Operas for Mozart (CUP, 2012) was a study of the Prague Italian opera company which gave the première of Don Giovanni. His current project is an investigation into the political and military background to Mozart’s operas in Josephinian Vienna.

Music & Letters is a leading international journal of musical scholarship, publishing articles on topics ranging from antiquity to the present day and embracing musics from classical, popular, and world traditions. Since its foundation in the 1920s, Music & Letters has especially encouraged fruitful dialogue between musicology and other disciplines. It is renowned for its long and lively reviews section, the most comprehensive and thought-provoking in any musicological journal.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Johann van Beethoven/ Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Johann van Beethoven’s last hurrah appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice“God Bless America” in war and peace

Related StoriesAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice“God Bless America” in war and peace

Depression in older adults: a q&a with Dr. Brad Karlin

On Veterans Day, the Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences published “Comparison of the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression among Older Versus Younger Veterans: Results of a National Evaluation” co-author Bradley E. Karlin joins us to discuss the evaluation’s promising results.

Why do older adults utilize mental health services at very low rates?

Research over the past several decades has consistently found older adults to utilize mental health services at rates substantially lower than those for their younger counterparts. In fact, a national study we completed several years ago found that older adults (those 65 and older) were three times less likely than younger adults to receive mental health care. Research has identified factors at individual, system, and policy levels that have contributed to enduring under-use of mental health services by older adults. One barrier has been stigma on the part of older adults and health care providers alike that symptoms of depression and other mental health conditions are natural byproducts of aging, which we know is not the case. As a result, many primary care physicians fail to detect mental health symptoms in older adults. For example, one study found that physicians assessed for depression in only 14% of older patient visits. Compounding the problem is recent research that suggests that older individuals often fail to identify mental health symptoms as symptoms of a mental health problem, and when they do they often do not know where to go for help. When older adults do seek help for these symptoms, they often present to their primary care physician who may mistakenly attribute these symptoms to a medical condition or to aging. So, it’s a vicious cycle.

Furthermore, older adults have often been viewed by some professionals as less treatable clients, which has further limited referral for mental health treatment. Older individuals, particularly those born around or before 1940, often hold negative views toward mental illness and mental health treatment, due to differences in how mental illness was conceptualized and treated in the first half of the 20th century when they grew up. Many older adults also grew up in a time when self-resilience and getting through difficult circumstances on one’s own was important and emphasized.

Restrictive Medicare reimbursement policies related to psychological services and lack of affordability have also contributed to limited access to mental health services among older adults, particularly for those without supplemental Medicare (“Medigap”) insurance. For decades, Medicare only reimbursed outpatient psychological services at the rate of 50 percent, whereas general outpatient medical services are reimbursed at the rate of 80 percent. Having to pay 50% of a $100-$150 psychotherapy session is certainly prohibitive for many older adults. We have also identified in our work a number of additional regulatory barriers that have further limited Medicare coverage of mental health services for older adults. Fortunately, there are some very positive regulatory and policy changes on the horizon that portend greater financial access to mental health services for older adults. Thus, it is imperative that effective mental health treatments be available for older individuals.

Depression among older adults is a major concern for both the individual suffering from it and society at-large. What are some of the consequences of untreated depression in older adults?

Untreated depression in older adults has profound consequences, including mental health and physical health consequences, as well as family, social and economic, and societal costs. Some specific examples include increased risk of heart disease, reduced motivation, increased disability, exacerbation of and/or delay in recovery from medical illness, greater use of medical services, increased mortality, reduced treatment compliance, and increased suicide and mortality, as well as lower quality of life. In light of these major consequences, untreated depression among older adults is a significant public health concern and is on track to become an even greater public health concern due to large increases in the older adult population projected in the years ahead.

What is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for depression? What are its most significant

differences from other forms of therapy?

Cognitive behavioral therapy is a structured, short-term approach to psychotherapy that helps clients learn and apply specific strategies to modify rigid or extreme thoughts and behaviors that are associated with depression. CBT has been shown to be effective for mild, moderate, and severe depression symptoms, though most of the research examining CBT has been conducted on younger populations and conducted in research settings with approved research subjects, as opposed to routine clinical settings where “real-world” older and younger individuals present for care.

While several other forms of psychotherapy are effective, cognitive behavioral therapy is the most widely-researched and differs from other forms of psychotherapy in several ways. In CBT, the client takes an active role in treatment by learning new skills to change certain patterns (ways of thinking and interpreting situations, as well as behaviors) that contribute to and maintain depression. Specifically, CBT involves developing new ways of interpreting aspects about oneself, the world, and the future that allow for more flexible, realistic, and balanced appraisals that generally evoke different types of responses than do more extreme or inflexible ways of thinking. Individuals with depression (young and old) generally look through “distorted lenses” that color their perception of their lives and things around them. CBT provides skills for evaluating one’s self and day-to-day experiences that are more balanced and complete. The second main focus of CBT is on increasing pleasant and self-promoting behaviors. Decades of research has shown that individuals with depression engage in very few pleasurable and rewarding activities. In CBT, the therapist helps the client to identify and increase their involvement in such activities through a structured, therapeutic process. The process of changing unhelpful or extreme thoughts that contribute to depression and increasing self-promoting behaviors is tied to the specific understanding of the client and to specific behavioral goals that are developed between the therapist and client at the outset of therapy. Thus, CBT focuses more on active, change-oriented process and skills than some other forms of psychotherapy that are passive in nature. Other, more “supportive” psychotherapies, for example, may involve just talking about one’s life without the development of new skills and actions. CBT is also present-focused and does not involve extensive discussion about one’s past as some other forms of therapy may emphasize. CBT is also brief in nature, with a typical course of CBT lasting approximately 12-16 sessions. Other forms of psychotherapy can last significantly longer.

Your evaluation looks at 874 veterans treated for depression with cognitive behavioral therapy. What were the results? What is particularly noteworthy?

The results of the evaluation reveal that cognitive behavioral therapy resulted in significant reductions in depression and improvements in quality of life among both older and younger Veterans. Furthermore, the outcomes and rate of treatment completion were virtually identical for the two age groups. What is also particularly noteworthy is that these improvements were the experiences of real-world older and younger veterans, often with complicated presentations, treated in routine settings by clinicians completing training in CBT. This naturalistic evaluation design differs from research conducted in controlled settings. Moreover, the level of effectiveness observed in this evaluation is comparable to that reported in randomized controlled trials of CBT.

What implications do the results have for mental health policy?

The results suggest that cognitive behavioral therapy is an effective and acceptable treatment for older adults and that CBT can be disseminated to real-world settings with very favorable outcomes. These findings are timely given important changes in the Medicare Program that will significantly increase older adults’ financial access to psychological services. Beginning in January 2014, the rate of Medicare reimbursement for outpatient psychotherapy and other psychological services will increase to 80%. Consequently, the results of this evaluation suggest important opportunities for effectively treating older adults with depression who may present for care in greater numbers than in the past. The results also point to the need for qualified mental health professionals to treat older adults. We are closer than we have ever been to bridging wide and enduring gaps in mental health treatment for older adults.

Dr. Karlin is the co-author of “Comparison of the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression among Older Versus Younger Veterans: Results of a National Evaluation,” published in The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences. He is National Mental Health Director for Psychotherapy and Psychogeriatrics for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). He has national responsibility for developing, implementing, and evaluating mental health programs in evidence-based psychotherapy and psychogeriatrics in the VA health care system. Dr. Karlin is also Adjunct Associate Professor in the Department of Mental Health of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University.

The Journals of Gerontology® were the first journals on aging published in the United States. The tradition of excellence in these peer-reviewed scientific journals, established in 1946, continues today. The Journals of Gerontology Series B® publishes within its covers the Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and the Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dramatic close up portrait of a middle aged army veteran. © nstanev via iStockphoto.

The post Depression in older adults: a q&a with Dr. Brad Karlin appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationMatching our cognitive brain span to our extended lifespanThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice

Related StoriesAlcohol marketing, football, and self-regulationMatching our cognitive brain span to our extended lifespanThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice

The many “-cides” of Dostoevsky

By Michael R. Katz

In his classic study Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics (1929), the literary theorist, scholar, and philosopher of language, Mikhail Bakhtin included a brilliant “exercise” in literary “what-ifs.” In the chapter entitled “The Hero in Dostoevsky’s Art,” Bakhtin analyzes as a characteristic example of the Leo Tolstoy’s “monologic manner” and poses the following question: “How would [Tolstoy’s] ‘Three Deaths’ look if… Dostoevsky had written them, that is, if they had been structured in a polyphonic manner?”

The critic goes on to make a more general point:

Of course, Dostoevsky would never have depicted three deaths: in his world, where self-consciousness is the dominant of a person’s image and where the interaction of full and autonomous consciousness is the fundamental event, death cannot function as something that finalizes and elucidates life. Death in the Tolstoyan interpretation of it is totally absent from Dostoevsky’s world.

Bakhtin’s 1963 edition contains further provocations:

In Dostoevsky there are considerably fewer deaths than in Tolstoy – and in most cases Dostoevsky’s deaths are murders and suicides. In Tolstoy there are a great many deaths…. Dostoevsky never depicts death from within. Final agony and death are observed by others. Death cannot be a fact of consciousness itself…. In Dostoevsky’s world death finalizes nothing, because death does not affect the most important thing in this world – consciousness for its own sake…. In Dostoevsky’s world there are only murders, suicides, and insanity, that is, there are only death-acts, responsively conscious….

There are indeed, as Bakhtin states, “a great many deaths in Tolstoy,” and they have attracted a considerable amount of attention from literary critics. The list covers Tolstoy’s entire career, from beginning to end, from his early work Childhood (1852) to his short story “Alyosha-the-Pot” (1904), published posthumously.

On the other hand, only a small number of “natural deaths” ever occur in Dostoevsky’s fiction. The author’s real interests and talents are revealed in the assortment of murders, both literal and metaphorical, committed in every one of his novels. There are numerous murders and suicides, responsively conscious “death acts” that span his literary career as a novelist from his first novel, Crime and Punishment (1866), to his last, The Brothers Karamazov (1880).

For example, in Dostoevsky’s Devils, there are two contrasting deaths in quick succession. Stepan Verkhovensky dies nearing the end of his bizarre pilgrimage to the monastery at Spasov, accompanied at first by the gospel seller, Sofiya Ulitina, then joined by Varvara Stavrogina. Languishing in a large hut, a doctor is summoned who announces that one should expect “even the very worst.” A priest is sent for and Stepan undergoes a sort of conversion. The narrator explains:

Whether he really had converted or whether the majestic ceremony attendant on the administration of the sacrament had impressed him deeply and aroused his artistic sensibility, still, firmly and, it’s said, with great emotion, he uttered several things in direct contradiction to his former convictions.

Stepan dies “three days” later (the number three marking the death of a person who is “saved”). He is buried in hallowed ground, the churchyard in Skvoreshniki, and his grave is covered over with a marble slab.

Stepan’s death is followed immediately by the discovery of Nikolai Stavrogin’s suicide in his mother’s house in Skvoreshniki. She rushes up the stairs to the attic in “his part of the house,” and discovers her son’s body hanging by a strong silk cord amply smeared with soap, behind the door. A note declares: “No one is to blame, I did myself.” The narrator concludes: “Everything indicated premeditation and consciousness up to the very last minute.” The final line of the novel confirms both the medical diagnosis and the hero’s spiritual desolation: “At the postmortem our medical experts absolutely and emphatically rejected the possibility of insanity.”

Stepan’s demise contains clear echoes of two deaths in Tolstoy’s novels: Prince Andrei in War and Peace and Ivan Ilych in The Death of Ivan Ilych. In a curious way, the description of Stepan’s strange pilgrimage and departure foreshadows Tolstoy’s own real-life pilgrimage and departure forty years after the novel was written. An article in the recent Dostoevsky Encyclopedia published in Moscow in 2008 even suggests that Dostoevsky

…as it were exactly described exactly forty years (!) before it happened, the last days of L. N. Tolstoy: his ‘departure,’ feverish illness en route, and his death in a stranger’s bed, in an accidental house….

Dostoevsky contrasts the death of Stepan Verkhovensky with the “murder” (suicide) of Nikolai Stavrogin, thus juxtaposing two primary forms of “death-departure.” Bakhtin argued that “righteous men,” earn “a special place occupied by their death-departures” in Dostoevsky’s novels. Stepan Verkhovensky’s end represents the epitome of the “death-departure” of a righteous man, one who was not always righteous, but who became so at the end. Nikolai Stavrogin’s strange and pitiful suicide is much more typical of the death-acts described in Dostoevsky’s novels than is Stepan Verkhovensky’s “Tolstoyan” “conversion.”

Michael R. Katz is C.V. Starr Professor Emeritus of Russian and East Eur. Studies at Middlebury College. He is the editor and translator of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Devils.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image Credit: Portrait of Fedor Dostoyevsky. By Vasily Perov. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The many “-cides” of Dostoevsky appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAsbo, Jago, and chavismo: What party hat for Arthur Morrison?Reading close to midnight in a leather armchairA Hallowe’en reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesAsbo, Jago, and chavismo: What party hat for Arthur Morrison?Reading close to midnight in a leather armchairA Hallowe’en reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Reflections on Disko Bay

Miniature icebergs that would fit in the palm of my hand float along the water’s edge, but the air is cold enough to resist the impulse to crouch down and remove my gloves to pick them up. Looking up across the glass-like surface, I spot hundreds of similar chunks like pieces of frozen vanilla popsicle that have fallen just out of reach. Yet these extraordinary white chunks are the famous icebergs of Disko Bay, the birthplace of the object that sank the Titanic over a hundred years ago. Yet from the shore, no hint of that danger appears from this place natives call “Illulisat,” or the “place of the icebergs.”

Standing still, the icebergs float by peacefully and quietly like clouds. Then suddenly a flash of snow appears like powder kicked up by a skier and an instant later a slab of snow tumbles from the side of the iceberg and lands in a single splash. This splintering of an iceberg called “calving,” echoes the image of a cow giving birth in the stable as the newborn plops onto the straw. Only once the snow “calf” has splashed into the water, ripples of its birth rapidly spread out in a circle. A few moments, the ripples disappear and the water surrounding the bergs resumes its former smooth and seemingly motionless surface. Moments pass, then minutes, then perhaps an hour, before another flash of snow and another iceberg calves into the water.

Out on a boat moving among the icebergs the sense of safety melts away. The birth of smaller icebergs, so stunning from land, takes on a more menacing aspect. The popsicle pieces are giants, towering hundreds of feet above the small but sturdy ship that maneuvers cautiously around them. Several hundred feet away, a small amount of powder flashes out just near the bottom of a berg, followed by the distinctive single plop. While the slow moving concentric circles that seemed as harmless as a pebble landing in a brook, once in the water, they rocked the entire boat from side to side as if a giant ship has just passed us by. The chatter on board ceased and the boat was suddenly silent. The ice that has just hit the water a quarter of a mile away was only fifteen feet long and tumbled from merely one-tenth the way up the side of the iceberg. It has dawned upon each one of us, just how deadly this place of icebergs is, and just how exposed we are to danger standing on a small wooden platform among nature’s slow moving giants.

Map of the Crown Prince Islands, Disco Bay, Greenland. Created by Silas Sandgreen. Public Domain via Library of Congress. Appears in the Oxford Map Companion.

Yet as quiet as it appears from the shore, moving among the bergs, the landscape rarely remains silent. From the small outboards to small factory size trawlers every fishing vessel must push the ice aside in order to move across the bay. The ice hisses, growls, groans, snaps, and cracks smartly as dozens of boats strike those palm size pieces that appeared so tempting from the bay’s edge. With a sound grinding like the wheels of a train screeching to a halt, each boat jerks forward to the next piece of ice. Two-thirds of an iceberg (on average) lies beneath that hand-sized sliver. Looking straight down at the blue-green water surrounding the tip of a slim iceberg that barely rises above the surface, an inverted giant white mushroom blooms.

I wanted to find a map of the waters of this incredible place, but had trouble making myself understood. I had gone down the steep hill to the working harbor and dodged in and out of stores selling marine equipment, replacement parts for engines, ropes, and everything else that commercial fishermen would need. No one seemed to know what I was talking about. My Danish was very basic, my Greenlandic non-existent. But one man, dressed in fisherman’s clothes like so many others, understood. Like everyone else in this tiny place, he had many jobs, he said; he was also a cab driver, and the high school science teacher. As he whipped out his iPhone a map appeared, and as he skimmed his fingers across the screen, the depths of the bay, the map that I had been searching for days suddenly appeared in vivid color with the familiar depth lines and numbers. I was the old fashioned one, looking for a map drawn on paper, while the Inuit fishermen had turned to modern cell phones and electronics years before. Aware of the irony, I asked where I could find the paper versions of iPhone charts. My befriender said that halfway up the hill from the harbor was a marine store, where the owner was still stuck with the paper that no one had used in years.

I trudged back up the hill, and into another marine store like so many others. Only this time I asked for the paper version of what everyone used to navigate and now the store owner understood me. He was delighted to get rid of them; no one in Illulisat had needed anyone of these in years, just the foreigner who wanted something for that similarly old-fashioned object, a history book.

As the noisy turboprop revved its engines for take-off I looked one last time at the bay below. Icebergs resemble clouds; look up at the sky and you see one pattern, look away for an instant, and they are gone. Like winds in the sky, the currents of Disko Bay tug the towering mountains of snow and ice away, so that even watching the same chunk of ice, a different shape or angle appears the next time you glance up. The shapes, angles, and even sizes shift in a continually scrolling landscape where nature never repeats the same forms. And then in a minute, even the bay disappeared.

Patricia Seed is Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine. She is the author of several books including The Oxford Map Companion: One Hundred Sources in World History, American Pentimento: The Pursuit of Riches and the Invention of “Indians” (2001) and Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640 (1995). In recent years, Seed has been intensively involved in research on old and new questions in cartography.

Greenland is a finalist for our Place of the Year 2013 competition. Vote for your choice in the poll below:

What should be Place of the Year 2013?

SyriaTahrir Square, EgyptRio de Janeiro, BrazilThe NSA Data Center, United States of AmericaGrand Canyon, Greenland

View Result

Total votes: 153Syria (41 votes, 27%)Tahrir Square, Egypt (13 votes, 8%)Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (38 votes, 25%)The NSA Data Center, United States of America (26 votes, 17%)Grand Canyon, Greenland (35 votes, 23%)

Vote

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reflections on Disko Bay appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMapping world historyAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2013: Behind the longlist

Related StoriesMapping world historyAnnouncing the Place of the Year 2013 Shortlist: Vote for your pickPlace of the Year 2013: Behind the longlist

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Just over forty years ago, President Richard M. Nixon ran a successful reelection campaign based partly on a simple insight. Americans, he believed, were not opposed to the Vietnam War as such; they were simply opposed to their boys dying in Vietnam.

In 1969 when Nixon came to office, US weekly death tolls had hovered around 300, sometimes even topping 450. Nixon’s response had been to turn the bulk of the ground fighting over to the South Vietnamese. The ultimate result, in terms of US losses, had been stunning. On 21 September 1972, just weeks before Americans voted in the presidential election, Nixon’s government could happily announce that the past week had seen no combat deaths—the first time this had happened in seven years.

For Nixon, this dramatic reduction in the weekly death toll proved a major short-term political success, helping him to an electoral landslide against George McGovern, the Vietnam era’s only out-and-out antiwar candidate.

For American society as a whole, however, the prospect of an end to current casualties could scarcely erase the massive trauma that the war had engendered. Yes, Americans were thankful that very few of their boys would now die in Vietnam. But they could not easily forget that so many of them had already paid the ultimate sacrifice in a war whose aims were murky and whose outcome became America’s first defeat, with South Vietnam’s dismal collapse two-and-a-half years after Nixon’s reelection.

In the aftermath of defeat, Vietnam remained a deep, festering wound in the American national psyche. Cold War hawks were particularly concerned. They worried that the memory of war was paralyzing the nation, precluding public support for the use of force in future battlegrounds with the Soviet Union. Ronald Reagan was their cheerleader. “For too long,” Reagan declared during his successful presidential campaign in 1980, “we have lived with the ‘Vietnam syndrome.’ . . . We dishonor the memory of fifty thousand young Americans who died in that cause,” he added, “when we give way to feelings of guilt as if we were doing something shameful.”

As Reagan spoke, the Vietnam Memorial was being built in the capital’s Mall. In a war so plagued by controversy, it was bound to become yet another battleground. Hawks preferred something grand, something that summed up their view that the war had been a “noble crusade,” not a shameful indiscretion. Many did not take kindly to the understated simplicity of the actual design. The Memorial’s purpose, jeered one, was merely to impress on visitors “the sheer human waste, the utter meaningless of it all.”

A joint services color guard displays state flags during the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 13 November 1982. From US Department of Defense. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the thirty years since it was unveiled, a sense of waste and meaningless has certainly remained at the heart of America’s continued memory of the war, dominating popular culture and casting a profound shadow over debates about war and peace. But this has not been the fault of the Memorial. Nor was it the Memorial’s purpose.

Indeed, although the Vietnam Memorial has become important in the continued political debate about the war, it has also transcended the narrowly conceived way that politicians have dealt with both Vietnam’s memory and the human sacrifices that are the most tragic consequence of this, and other, conflicts.

Too often, political debates about war revolve around current casualty totals. This was Nixon’s insight, and it obscured a much more fundamental truth. Casualties are never merely nameless numbers: behind each one lays a tragic story. Nor do casualties simply exert a short-term impact over the public debate: these losses linger, and not just in shaping political views. Rather, they create a painful void, as well as a need to grieve and remember the person.

The great strength of the Vietnam War Memorial is that it provides a place to mourn these individual deaths. The design is simple: the black stone, the leafy surroundings, and above all the long list of names, which rise and fall in an echo of the escalating and declining rhythm of America’s war.

In the thirty years since it opened, the Vietnam Memorial has become a important marker with families, veterans, and tourists alike, and one of Washington DC’s most visited sites. In a war in which so much was, and remains, contested, the Memorial is a fitting and moving tribute to those who never returned.

Steven Casey is Professor of International History at the London School of Economics. His books include Cautious Crusade and Selling the Korean War, which won the Harry S. Truman Book Award. His new book, When Soldiers Fall: How Americans Have Confronted Combat Losses from World War I to Afghanistan will be published January 2014.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Vietnam Veterans Memorial appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“God Bless America” in war and peaceThe science of consciousness must escape the religious dark agesOxford University Press and the Making of a Book

Related Stories“God Bless America” in war and peaceThe science of consciousness must escape the religious dark agesOxford University Press and the Making of a Book

The science of consciousness must escape the religious dark ages

Each one of us has an inner feeling, an experience that is private. Consciousness, awareness, qualia, mind, call it what you will, it is the subtle distinction between merely computing information and feeling. The science of consciousness, a relatively new and growing area of research, asks how this non-physical feeling relates to the brain. How can circuits made of neurons do more than compute information—color, sound, location, and so on? How can they also create an awareness of those things? The answer to that question, if an answer is possible, would be the ultimate in human scientific understanding. That, at least, is the typical assumption.

To me, however, this typical way to frame a question has derailed all scientific progress. It is effectively religion in disguise, and perhaps also a bit of the worship of mystery. The objective phenomenon that we have in front of us, that we know exists, is not a semi-magical inner feeling. The phenomenon is that brains attribute that semi-magical property to themselves. Brains attach a high degree of certainty to that attribution. Attribution is not semi-magical. It’s in the domain of computation and information processing. It can be understood, it can be studied scientifically, and it can even be engineered.

To better explain this ideological divide between the most common (closet religion) approach to consciousness, and the more rationalist and scientific approach, I’ll use the analogy to the belief in God. God is a construct of the human brain. The reason why so many people believe in it intuitively and implicitly is because of a host of social factors, psychological factors, even evolutionary factors. The details aren’t fully understood, but the basic outlines of the theory are in place.

This brain-based theory of God is pretty close to how most atheistic scientists view the matter. A theologian might argue that the theory doesn’t explain God. It merely explains how so many people come to believe in it. But from a scientific perspective, the objective phenomenon before us isn’t the presence of a deity. The phenomenon is that so many people believe in it with such fervor. The theory explains the observable facts of the case. To postulate that there actually is a magical deity would be redundant and would add no further explanatory power.

In the same way, it’s nonsensical to try to understand how a brain might produce that ethereal, non-physical property of awareness. But it’s not that difficult to understand, at least in principle, how a brain might attribute that property of awareness to itself.

Brains are information processing devices and commonly attribute properties to things. That’s how brains understand the world, both the external and internal world. Those attributed properties are never entirely accurate or even physically coherent. Color, for example, is a construct of the brain, only roughly based on wavelength, and attributed to surfaces in the real world. In the same way, specific systems in the brain must compute the construct of awareness, of an inner feeling, of a subjective experience, and attribute that subtle set of properties to oneself.

One of the more interesting, commonly overlooked properties of awareness is that we not only attribute it to ourselves, but we also attribute it to other people. When I’m in the room with another person, I have an immediate, gut intuition that the person is aware, aware of me, aware of the topic of conversation, aware of the other items in the room. I don’t need to figure it out cleverly. I don’t need to think it through. I can do that too, but prior to any higher order cognition, I have an immediate intuition, one might call it a social perception. My brain has attributed awareness to the other person much like it attributes the color blue to that person’s shirt. My brain attributes awareness and attaches a high degree of certainty to that attribution. Could it be that awareness is an attribution, and that the specific systems in the brain that compute it and project it onto other people are the same as the ones that attribute it to ourselves?

As long as the science of consciousness clings to the belief in magic, in an actual ethereal property of awareness somehow generated by the brain, then no progress is possible. Scientists who study consciousness need to look closely and see where their hidden spiritual assumptions lie.

Michael Graziano is a professor of Neuroscience and Psychology at Princeton University. His recent book, Consciousness and the Social Brain, explores this possible account of consciousness. He lays out a theory, explores in detail how it might explain the known phenomena in their full complexity, and describes how the theory relates to many previously proposed theories. In his view, once the spiritualist or semi-magical view of consciousness is banished, the answers begin to fall into place. The outlines of the theory become clear and a host of experimental findings begin to fit. He is also a novelist and composer. His contributions on the functioning of the brain regularly appear in scientific journals such as Science, Nature and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. His novels include The Divine Farce and The Love Song of Monkey. More information can be obtained on his web site:

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image via iStockphoto.

The post The science of consciousness must escape the religious dark ages appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLéger’s The City and neuroaestheticsCajal´s butterflies of the soulMatching our cognitive brain span to our extended lifespan

Related StoriesLéger’s The City and neuroaestheticsCajal´s butterflies of the soulMatching our cognitive brain span to our extended lifespan

Oxford University Press and the Making of a Book

To celebrate the publication of the first three volumes of The History of Oxford University Press on Thursday and University Press Week, we’re sharing various materials from our Archive and brief scholarly highlights from the work’s editors and contributors. To begin, we’d like to introduce a silent film made in 1925 by the Federation of British Industry. The Oxford University Press and the Making of a Book was one of a series illustrating industrial life and it highlighted the Press’s work to audiences around the world. It also provides great insight into each step of the printing process from casting type and composition, to casting plates and stereotyping, to binding and shipping.

Click here to view the embedded video.

With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. It also considers the effects of wider trends in education, reading, and scholarship, in international trade and the spreading influence of the English language, and in cultural and social history — both in Oxford and through its presence around the world.

Video: Copyright Confederation of British Industry. Used with permission by Oxford University Press. Courtesy of the Oxford University Press Archive.

Music credits: Golden Age Skit (1773/6) by Paul Mottram (PRS) via US Audio Network. Capriccio (1545/1) by Paul Mottram (PRS) via US Audio Network. Stationmaster’s Whiskers (1769/1) by Paul Michael Harris (PRS) via US Audio Network.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oxford University Press and the Making of a Book appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“God Bless America” in war and peaceMapping world historyA call to the goddess

Related Stories“God Bless America” in war and peaceMapping world historyA call to the goddess

The concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice

Despite its constant invocation in doctrine, rhetoric and countless international documents, international lawyers still struggle with arriving at a well-defined understanding of the concept of an ‘international community’, whether in identifying the members that compose it, the values and norms that it represents, or the processes which underlie its functioning. The term could be reduced merely to ‘constructive abstraction’, or rhetorical flourish; yet a concept of international community that would be legally operative (create enforceable legal rights and obligations) would require reflection as to the nature of international law and whether it serves the interests of a constituted community.

There are two primary understandings of the concept of ‘international community’. The first that the concept is purely relational: a fully inter-State order, with only a law of co-existence that demands only such rules and norms such as to ensure the survival of members of that society. According to such a view, the members of international society are primarily, if not exclusively, sovereign States. No common interest can be distilled from such a form. The second understanding is not formal, but substantive: the international community would be said to share a number of common interests and fundamental values that the legal order would exist to safeguard. Made legally operative, and embracing a distinct extra-legal element, the claimed ‘promise of justice’ embodied therein would lead to actors and institutions within the system claiming the obligation to protect the community interest.

The International Court of Justice. Photo by Minister-president Rutte. Creative Commons License via Flickr.

I sought first to distil the essential differences between the two terms, as the latter understanding especially would empower international actors and institutions to enforce the community’s interest or ‘will’. In many respects, the very identification of the community’s interest is controversial, and as such has not always been specified or made clear in multilateral treaties. Hence, it has been left to judicial institutions, and primarily the principal judicial organ of the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, to elucidate these difficult concepts and to uphold or reject claims based on community interest. What transpired from my research was very interesting. In most cases, the Court was very cautious not to defend an international common interest, instead reading such obligations through a prism of multilateral or bilateral treaty relations: in short, through the prism of consent.I would like the highlight four cases in which the Court refused to recognise the substantive character of norms claimed to be fundamental to the international community, which we international lawyers call jus cogens (peremptory norms of general international law), and obligations erga omnes (obligations ‘owed to all’). The Court has rejected claims that States sought with respect to indirect injuries (ie not injuries to their territory or to their nationals) against other States in the name of the international community. It rejected, for example, the claims of Ethiopia and Liberia in South West Africa (1966) where they claimed against South Africa for its imposition of apartheid over Namibia in purported violation of the League Covenant and the United Nations Charter. The erga omnes claim was rejected, where the applicants were denied standing on the basis that they could not bring forward an actio popularis (an action brought by a member of the public in the name of public order).

It rejected those of Portugal in East Timor (1995), where that State claimed, on behalf of the people of East Timor, against Australia for treaties that it had signed with Indonesia on the maritime delimitation in the area. Although the Court did not formally declare that Portugal had no standing, it concluded that Indonesia was an indispensable third party to the dispute, and that without Indonesia’s consent, it could not possibly proceed to hear the merits.

The jus cogens or peremptory, non-derogable character of various human rights obligations has fared little better before the Court. In Armed Activities in the Congo (2006), the Democratic Republic of the Congo claimed against Rwanda for various serious human rights violations, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and even genocide. The Court, for the first time, actually recognised the concept. Yet even though it was willing to concede that the human rights violations could, if proven, constitute violations of jus cogens, it considered that it did not have consent over the dispute. Rwanda’s lack of consent was clear from its ‘reservations’ (unilateral statements tagged on to its ratification of treaties), through which it refused to consent to the Court’s jurisdiction. The Court upheld Rwanda’s lack of consent and declined to proceed to the merits.

Finally, in Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (2012), Germany claimed against Italy’s inaction against the Italian domestic courts, which were not recognising Germany’s immunity in respect of Nazi actions committed in Italy and against Italian nationals. Italy claimed that the jus cogens nature of the violations allowed its courts to ignore Germany’s immunity. However, the Court concluded that, whatever the jus cogens character of the violations committed by Nazi Germany, Germany’s immunity served as a procedural bar in the Italian courts, and Italy had thus violated Germany’s immunity by allowing the claims to go forward.

Taken as a whole, these cases demonstrate that the International Court continues to adhere to a restrictive vision of the international community. Without commenting on whether this is a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ development, it is an important point to make in the light of claims in scholarship that we ought to be assigning greater law-making power to judicial institutions, in particular with respect to the safeguarding of fundamental human rights. The Court’s reluctance may be due to institutional self-preservation, as its jurisdiction remains dependent on the consent of States; but equally so, the Court’s caution may be due to the difficulties and lack of agreement as to the consequences entailed by an embrace of a nebulous community interest that remains yet to be elucidated. In a decentralised, highly indeterminate legal order like international law, perhaps the unwillingness to assume a centralised interpretative role for itself is a statement more on the nature of international law than any value judgment on the concept of ‘community’.

Dr Gleider I Hernández is Lecturer in Law at the University of Durham, where is he is also Deputy Director of the new Institute for Global Policy. Previously, he served as law clerk to Judges Bruno Simma and Peter Tomka at the International Court of Justice; he holds law degrees from McGill, Leiden, and Oxford universities. His research interests extend to all areas of public international law, and he is especially interested in the nature and function of the international legal system. His first monograph, The International Court of Justice and the Judicial Function, will be published by the Oxford University Press in early 2014. He is the author of “A Reluctant Guardian: The International Court of Justice and the Concept of ‘International Community’” in the British Yearbook of International Law, available to read for free for a limited time.

Through a mixture of articles and extended book reviews it continues to provide up-to-date analysis on important developments in modern international law. It has established a reputation as showcase for the best in international legal scholarship and its articles continue to be cited for many years after publication. In addition, through its thorough coverage of decisions in UK courts and official government statements, The British Yearbook of International Law offers unique insight into the development of state practice in the United Kingdom.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Radar with red target blip and green sweeping arm. © axstokes via iStockphoto.

The post The concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of Justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhite versus black justiceIs big data a big deal in political science?Argentina’s elections: A Q&A

Related StoriesWhite versus black justiceIs big data a big deal in political science?Argentina’s elections: A Q&A

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers