Oxford University Press's Blog, page 882

November 10, 2013

Alcohol marketing, football, and self-regulation

When we work at home, my partner and I share a workspace (or kitchen table as it is also known). This is generally friendly and allows for moments of mutually constructive musing and problem-solving. A recent exchange went like this:

Me: “Who is Everton’s shirt sponsor again?”

Him: “Emmm…is it Chang with the elephants?”

Me: “Yeah, right, thanks.”

Pause

Him: “Sorry, what are you doing? I thought you were working?”

Me: “I’m doing my talk on alcohol marketing in sport.”

Him: “What’s Everton’s shirt sponsor got to do with that?”

Me: “Well…duh…Everton’s a football team and Chang’s a beer.”

Him: “Chang’s a beer? That’s outrageous! What are they doing on Everton’s shirts?” (he’s a public health researcher too)

Everton player Louis Saha sports a Chang branded training top

My partner is a not a football fanatic, but he knows a bit about football. Certainly enough to be able to easily remember Everton’s shirt sponsor; and Everton is not his team. Chang is definitely not his beer. So the only place he must know the brand from is Everton’s shirts.

When we set out to quantify the volume of alcohol marketing in televised English football, I knew there would be some, but I was caught off guard by quite how much there was. We found an average of almost two visual references to alcohol per minute of broadcast. But what was much more interesting was how embedded these references were. Less than 1% of the broadcasts were devoted to formal alcohol advertising during commercial breaks. Instead, almost all of the alcohol marketing we found was on or alongside the football pitch, or part of the graphics added by broadcasters. It was simple logos, frequently repeated.

We know that alcohol marketing affects children, in particular. When children are exposed to alcohol marketing, those who do not yet drink are more likely to start drinking, and those who already drink are more likely to drink more. Children are also very aware of alcohol marketing. More than three-quarters of Scottish 12-14 year olds are aware of some sort of alcohol marketing, and two-thirds of them are aware of alcohol marketing in sport.

In the UK, alcohol marketing is governed by an industry sponsored self-regulatory code of conduct. When commercial industry is charged with regulating its own marketing, the potential for conflict of interest is obvious. In the sphere of food marketing to children, there seems to be numerous examples of industry involvement in regulation leading to watering down of who and what is covered by the regulations. Indeed, in the USA, industry backlash led to the White House abandoning efforts to even introduce standardised self-regulation. There is now clear evidence that the UK alcohol industry is breaking its own code of conduct by making specific efforts to target products at under-age drinkers.

In addition to the inherent problems of self-regulation of marketing and the growing failure of such self-regulation, the frequency and nature of alcohol marketing we found in televised football highlights a mismatch between what the code of conduct is designed to restrict and what is actually shown. The alcohol marketing we found in English football was almost entirely frequently repeated exposure to simple branding and logos. In contrast, the code of conduct focuses on what alcohol should not be associated with.

According to the code, alcohol marketing should not “in any direct or indirect way…suggest any association with bravado, or with violent, aggressive, dangerous or anti-social behaviours…illicit drugs…sexual activity or sexual success…[or] that consumption of the drink can lead to social success or popularity”.

The impact of marketing is related to both exposure and power. Power refers to the creative content of marketing — how memorable a single exposure is and how well it appeals to particular individuals. Power can be difficult to quantify, but is why Don Draper gets paid so well. Exposure is simply about how often you see the marketing. There is no simple formula linking impact, exposure and marketing. But clearly if you can’t have one, you would be well advised to go all out for the other.

The UK’s alcohol marketing code of conduct seems to focus entirely on marketing power. It restricts the creative content of the sort of narrative advertisements shown in the commercial breaks between programming. It has absolutely no impact on exposure.

It is difficult to say if restrictions on alcohol marketing power triggered increases in exposure, or if industry lobbied for restrictions on power rather than exposure because they know something about the relative influence of each on impact. Or perhaps there is no simple either:or. But what we are left with is a code of conduct that appears to have little bearing to the nature of the huge volume of alcohol marketing seen in televised football (and, I would wager, elsewhere).

Stronger restrictions on alcohol marketing in sport, and elsewhere, are never going to be a magic bullet that will solve the problem the UK currently seems to have with alcohol. But as part of a suite of approaches limiting advertising, affordability, and accessibility it would make an important contribution.

Jean Adams is a Senior Lecturer in Public Health at Newcastle University, UK. She edits the Fuse Open Science Blog and can be found on Twitter at @jeanmadams. She is one of the authors of the paper ‘Alcohol Marketing in Televised English Professional Football: A Frequency Analysis’, published in the journal Alcohol and Alcoholism.

Alcohol and Alcoholism publishes papers on biomedical, psychological and sociological aspects of alcoholism and alcohol research, provided that they make a new and significant contribution to knowledge in the field. Papers include new results obtained experimentally, descriptions of new experimental (including clinical) methods of importance to the field of alcohol research and treatment, or new interpretations of existing results. Theoretical contributions are considered equally with papers dealing with experimental work provided that such theoretical contribution are not of a largely speculative or philosophical nature. Alcohol and Alcoholism is the official journal of the Medical Council on Alcohol.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Louis Saha, Everton. By nicksarebi [CC-BY-SA 2.0], via Flickr.

The post Alcohol marketing, football, and self-regulation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHope and healthThe ups and downs of weight lossThe world of the wounded

Related StoriesHope and healthThe ups and downs of weight lossThe world of the wounded

Léger’s The City and neuroaesthetics

Facing The City painted by Léger in 1919 can be an overwhelming experience. Geometry of bright colors, bits of human figures, mechanical structures, columns, stairs, lettering all crowd the painting and beyond into an immersive experience. The large canvas (7 feet 7 inches by 9 feet 9½ inches) is the focal point of the Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibit currently on view till 5 January 2014. The painting conveys the sense of being in the center of the cultural and intellectual maelstrom that was Paris after World War I. The exhibit places Léger’s art alongside the work of Delaunay-Turk, Mondrian, Duchamp, Picabia, van Doesburg, Le Corbusier, Ozenfant, Exter, and many others. Curiously, the painting also serves as metaphor for issues very much alive today in neuroaesthetics.

The City painted by Léger. Fair use via http://www.philamuseum.org.

One is struck by the painting’s reduction of forms. Humans are simple shapes, anonymous and colorless. They wend their way through streets and stairways. The industrial age rises as gray ovals of billowing smoke. The mechanical age is constructed with lines that hint at the Eiffel Tower. Advertisements are stylized as letters and angular frames that assault our senses.

Another striking feature of the painting is its fragmentation. Partial depictions, teeming, and overlapping, each piece vies for our attention. The image lacks a gravitational center that can anchor our gaze. Our eye is released to wander across the scene distracted by a bold color here, a disc there, and a partially obscured figure beyond. A third striking feature of the painting is the way Léger gives coherence to what could easily be visual chaos. He provides a compositional structure that organizes these reduced fragments into dynamic balance.

Reduction is the life-blood of any science. Take a complex system, break it down into component parts, and study those parts. The challenge for scientists is to reduce the complex system without losing sight of the whole. Knowing the properties of individual neuronal firing may be inherently interesting, but an individual neuron will not tell us much about aesthetics. By contrast, investigating whether a beautiful face activates part of visual cortex that is specialized for identifying faces as distinct from other objects like buildings might tell us whether the neural machinery that evolved to classify information is also used to evaluate that information. Alternatively, these functions of classification and evaluation might be neurally segregated.

Neuroaesthetics, like any experimental science, is also fragmentary. It moves forward by constructing experiments to test hypotheses that are confirmed or rejected. Advances are tentative and incremental. Each experiment, each publication, each claim is but a fragment. Discovering that people like curved architectural interiors and that this preference is etched into the general reward circuitry of the brain is a fragment of information. The fragment begs to be completed by further study. Is the preference for curved spaces accompanied by a desire to live in those spaces? Do people like curves in general or does this preference vary depending on the object of our interest?

Finding coherence within crowded data is a struggle for every scientist. One’s focus is typically narrow, trained on the details of specific experiments. How to frame those experiments, the way in which results might generalize and help give the field coherence, is not always obvious in adolescent fields like neuroaesthetics. This lack of coherence is also what makes the field exciting. Anticipating the compositional structure of neuroaesthetics might reveal where fragments need to be added, modified, or even deleted. One tentative framework for neuroaesthetics is to consider aesthetic experiences within the triad of sensations/movements, emotions, and meaning. Empirical aesthetics has traditionally focused on sensations and their relation to emotions in a simple way. Do you like this object or not? We need much more.

For me, The City evokes excitement. The vibrant energy and pulse of the image conveys optimism and an open sense of possibilities. I adore cities and this painting taps into that adoration. However, the very same painting might alienate someone else. The reduced and fragmented forms could feel soulless and evoke the anomie of being another cog in an indifferent mechanical world. One of the most pressing areas of neuroaesthetics is to understand how knowledge and experience modulate our emotional responses to artworks.

The name of the Philadelphia Museum of Art show is: “Léger: Modern Art and the Metropolis.” The City, more than metropolitan turns out to be cosmopolitan. Anna Vallye, the curator of the show, offers an appealingly broad view of the man and his art. Léger disregarded traditional boundaries. He moved fluidly through painting, theater, film, advertising, and architecture. Furthermore, he immersed himself in the intellectual and cultural fervor of the time. The exhibit displays his work in the context of his contemporaries many of whom were friends and collaborators. As pointed out by Roberta Smith in the New York Times, Léger through his art exemplifies the fact that culture is a collective project.

We in neuroscience could benefit from Léger’s example. There are too few of us working in domains like neuroaesthetics that cross traditional disciplinary boundaries. We need more scientists working in this field to make substantial progress and fill in the many fragments awaiting study. It also behooves us to think of neuroaesthetics as a collective project. We need to be in conversation, consultation, and collaboration with artists, philosophers, art historians, architects, critics, and cultural theorists. Neuroaesthetics can be a cosmopolitan science.

Anjan Chatterjee, MD, is a Professor of Neurology, and a member of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience and the Center for Neuroscience and Society at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art. In 2002, he was awarded the Norman Geschwind Prize in Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology by the American Academy of Neurology. He is the President of the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics and the President of the Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology Society.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Léger’s The City and neuroaesthetics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCajal´s butterflies of the soul“God Bless America” in war and peaceWhy does this baby cry when her mother sings?

Related StoriesCajal´s butterflies of the soul“God Bless America” in war and peaceWhy does this baby cry when her mother sings?

Mapping world history

Porcelain, sealskin, powder-horn, buckskin, silk, and parchment: these are what history is made of. Celestial histories — subway, radio, or Internet histories. Histories found in stick charts and ordnance surveys. From the Paleolithic Period to digital age, maps have illustrated and recorded history and culture: detailing everything from wars and colonization, to religious and jingoistic worldviews, to the textures of the heavens and the earth. Illustrated in the slideshow below are just a few maps from The Oxford Map Companion by Patricia Seed, which present some of the diversity of cartography and map-making across the centuries and across the globe.

MAP 88

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Soviet Georgia, from the first Russian Atlas, 1937-1939. Part of the first atlas created in either Russia or the Soviet Union, this economic map is characterized by its unique design in which industrial production is indicated by circles, and energy use is noted by stars.

MAP 33

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Jain World Map. At the center of this map is Mount Meru, which Jains, Hindus, and Buddhists believe to be the center of the world.

MAP 69

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Gyoki Map on a Porcelain Plate, c. 1830. Gyoki maps, such as the one depicted here, are named after the map Gyoki (668-748 CE) who is popularly associated with Japan’s conversion to Buddhism.

MAP 41

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Waldseemüller ‘s Map of the World, 1507. Best known for a famous mistake—incorrectly naming the Western Hemisphere “America”—this map displays ignorance of many features that had been well known and correctly drawn by nautical map makers for decades, and in some cases, centuries.

MAP 67

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Vale of Kashmir, 1836. Though it does not include measurement or scale, as a cultural portrait of Kashmir, this map is extraordinary.

MAP 58

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Cedid Atlas, 1803. From the first printed Ottoman atlas, showing Asia.

MAP 74

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Geological Map of Southwestern England, 1815. William Smith’s portrayal of Britain is the first ever geological map of an entire country (shown here is detail of Southwest England and part of Wales).

MAP 68

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Eight Provinces of Korea, c. 1850. Employing hanja-- Korean writing with Chinese characters—this map blends traditional Chinese styles with ones that are uniquely Korean.

MAP 63

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Dutch Polder Map, 1750. The peat mounds visible on this map are still maintained by the Delfland Water Board.

MAP 46

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Europe, from the first atlas, published by Abraham Ortelius in 1570.

MAP 26

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Medieval Islamic Map of the World, ca. 1300 CE. South lies at the top in this medieval Islamic world map.

MAP 75

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

1851 Whale Chart. More than just a whale chart, this map graphically shows the global search for new energy sources in the 19th century.

MAP 27

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Turkish Map of Central Asia, c. 1072 CE. Earliest known map drawn by a Turk.

MAP 26

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Medieval Islamic Map of the World, ca. 1300 CE. South lies at the top in this medieval Islamic world map.

MAP 25

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

World Climate Map. Earliest known sketch of the world according to climate zones.

MAP 22

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Gough Map of Britain, c. 1360 CE. This is Britain’s first transport map.

MAP 20

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Map of the Mediterranean, c. 1065 CE. An early example of a nautical chart, the circles represent islands in the eastern and central Mediterranean. The two rectangles on the right are Sicily (top) and Cyprus (bottom).

MAP 19

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Indus River, c. 1065 CE. The backwards S-shaped green line is a mirror image of the actual course of the Indus River.

MAP 7

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

First Maps of the Greek Constellations, Persia, 964 CE. The Library of Congress. The best known and most widely imitated star map of the Greek constellations came from a Persian scholar and Sufi, Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi.

MAP 6

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Arabic Star Lists, c. 1065 CE. The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. The earliest compilation of Ptolemy’s constellations became codified only in the 9th century CE, after it was published in Arabic.

Patricia Seed is Professor of History at the University of California, Irvine. She is the author of several books including The Oxford Map Companion, American Pentimento: The Pursuit of Riches and the Invention of “Indians” (2001) and Ceremonies of Possession in Europe’s Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640 (1995). In recent years, Seed has been intensively involved in research on old and new questions in cartography. She bring her skills in the use of digital imaging technologies (GIS and graphic design software) to the study–not only to reformulate the questions of the history of map making–but to offer historical and comparative scholarship new tools of analysis and new ways of representing the knowledge that it produces.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Mapping world history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe world of the woundedPlace of the Year: History of the AtlasA call to the goddess

Related StoriesThe world of the woundedPlace of the Year: History of the AtlasA call to the goddess

“God Bless America” in war and peace

If you watched the World Series this year, you may have noticed a trend in the nightly renditions of “God Bless America” during the seventh inning stretch: all five performances were by soldiers in uniform. (The only civilian performer, the singer James Taylor, opted to sing “America the Beautiful” instead of “God Bless America” in his tribute to the Boston marathon victims.)

Given the song’s strong associations with war, it seems fitting that the anniversary of its radio premiere falls on the eve of Veterans Day—this year, the 10th of November marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of “God Bless America.” But it may come as a surprise that when the song debuted in November 1938, it was originally positioned as a “peace song.”

The master songwriter Irving Berlin had first sketched the tune during World War I, as the finale for an all-soldier revue, but he ultimately decided not to include it. He later said that he felt it was “like gilding the lily” to have men in uniform performing such an overtly patriotic tune. Of course, this is in stark contrast to our contemporary experience of the song, where a performance by a uniformed soldier is used to underscore the song’s connection to support for the troops.

But back in 1918, Irving Berlin scrapped “God Bless America” from his soldier show. He filed it away in his trunk of rejected songs, where it lay forgotten until the fall of 1938, when the radio star Kate Smith and her manager Ted Collins asked Berlin for a new patriotic song for Smith to sing for a special Armistice Day radio show. As the story goes, Berlin rediscovered his old song, made changes to it, and gave it to Smith to premiere on her show, which aired on the eve of Armistice Day, 10 November 1938.

Click here to view the embedded video.

It is important to note that when Berlin recovered “God Bless America” from his trunk in 1938, much had changed since he had first sketched his song twenty years earlier. A wartime marked by the zeal of George M. Cohan’s “Over There” in 1918 had given way to an increasing mood of isolationism during the 1930s.

According to one public opinion poll given in 1936, 95% of Americans were opposed to US participation in another European war. In the fall of 1938, Irving Berlin told a reporter, “I’d like to write a great peace song […], a great marching song that would make people march toward peace.” Kate Smith expressed similar sentiments on her daytime talk show on the day of the song’s premiere, saying: “As I stand before the microphone and sing it with all my heart, I’ll be thinking of our veterans and I’ll be praying with every breath I draw that we shall never have another war.” Before its name was changed to Veterans Day in 1954, Armistice Day itself had obvious connections to peace; in May 1938, Congress declared the holiday “a day to be dedicated to the cause of world peace.”

Irving Berlin. Billy Rose Theatre Collection photograph file. New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery.

Some of the song’s original lyrics reflect its early status as a peace song. In October 1938, Berlin wrote an introductory verse, with lyrics that included a direct reference to anti-interventionism:

While the storm clouds gather far across the sea

Let us swear allegiance to a land that’s free

Let us all be grateful that we’re far from there

As we raise our voices in a solemn prayer

The storm clouds in the first line are an obvious reference to the growing strife in Europe, and follow Tin Pan Alley conventions linking bad weather to troubled times. But most importantly, the line “let us all be grateful that we’re far from there” strongly points to a non-interventionist position, one that may have been sympathetic to the suffering in Europe but that did not urge action to bring Americans into the fray. Kate Smith sang this verse in her weekly radio performances of “God Bless America” from the fall of 1938 into the early months of 1939. But when Irving Berlin copyrighted the printed sheet music in February 1939, he had changed “grateful that we’re far from there” to “grateful for a land so fair,” and this is how it has appeared ever since (though the song’s verse is rarely performed today).

So just four months after its debut in the fall of 1938, “God Bless America” was no longer a peace song. In fact, later articles and interviews about the song made no mention of the peace message that was present at the song’s origins.

There are a few reasons behind this shift. One important factor is that the premiere of “God Bless America” happened to occur the day after Kristallnacht, the Nazi Party’s calculated attacks on Jewish communities in Germany and its annexed territories. According to many scholars of World War II, the brutality of these attacks signaled a turning point for a growing American condemnation of Nazi Germany, and a consequent move away from staunch isolationism.

Irving Berlin’s removal of the line “grateful that we’re far from there” was a reflection of his own changing views as much as to shifts in public opinion. As a Jewish immigrant, Berlin showed growing concern about the Nazi Party’s rise in Europe and began to give large donations to Jewish relief work during this period. In her memoir, Berlin’s daughter Mary Ellin Barrett wrote that by 1940, “isolationists in our interventionist family became the enemy, or at best, if close friends, the misguided ones.” A “peace song” was no longer called for, and Irving Berlin himself began to lead the song at rallies in support of American involvement in the escalating conflict in Europe.

So as we celebrate the anniversary of the song’s radio debut, we can reflect on how dramatically its connection to war has shifted. “God Bless America” was rejected as inappropriate for soldiers to sing during World War I, yet performances by uniformed servicemen and -women have now become standard. It was originally written as a peace song for Armistice Day in 1938, but by 1940 had become an anthem for intervention, and it has retained its power as a symbol of support for war in the twenty-first century.

Sheryl Kaskowitz is the author of God Bless America: The Surprising History of an Iconic Song. She is a scholar of American music who has most recently served as a lecturer in American Studies at Brandeis University. Read her previous blog post.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post “God Bless America” in war and peace appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSix surprising facts about “God Bless America”The world of the woundedThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wetteman Jr.

Related StoriesSix surprising facts about “God Bless America”The world of the woundedThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wetteman Jr.

The ups and downs of weight loss

On 15 October 2013, the New York Times carried an article on President Taft’s struggle with his corpulence many decades ago. This “massively obese” man pursued weight loss into his old age. But long-term shedding of pounds eluded him. Instead, his ceaseless efforts produced frustration and repeated cycles of loss and regain. Writer Gina Kolata suggests that there are many similarities between Taft’s battles with his obesity and the challenges of weight loss in contemporary societies. A point well made.

The statistics available regarding obese individuals and their battles to lose weight are sobering. Of those who can shed pounds something like 95% gain back the weight that has been lost (and sometimes even more) within five years. Yet countless numbers of individuals are caught up in such doomed struggles. Why?

First, the censure visited upon fat people by society. Many surveys document that the vast majority of obese people have been subjected to humiliating comments and treatments not only by strangers but also by friends and family.

Second, the real but exaggerated physical consequences of obesity. There is some relationship of weight to such aliments as heart disease, cancer, joint problems, and so forth. Yet such concerns are often overblown or insufficiently evidence-based. Take mortality rates: it has long been thought that any excess weight places a person at risk for dying prematurely. Yet research now indicates that moderately overweight individuals have the lowest mortality rates; thin people have higher ones. When people are very obese there is an elevated risk of mortality; the exact extent of it remains in dispute.

Third, the relentless marketing of a welter of products and programs by the diet and equipment industries. For example, the Himalayan Diet Breakthrough pills promise significant and rapid weight loss without diet or exercise.

There is no easy and straightforward way to surrender our collective obsession with fat, but some strategies may point the way. Regulation, when used properly, has a role in such efforts.

First, the prejudice against fat people needs to end. We need to accept individuals of many shapes and sizes; judging them by their qualifications and not their weight. To achieve such acceptance we may need to amend human rights legislation to protect the obese from discrimination.

Second, there should be more curiosity about the causes of obesity than just “calories in/calories out”. For example, we should follow the lead of the White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity in urging more examination of the impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) on the health of individuals and their weight.

Third, we need to shift the emphasis from weight loss (and even prevention of weight gain) to health. That change would prompt us to tax junk food and beverages (while assessing the actual effects of such measures) but also push us to subsidize healthier alternatives. That underwriting would specifically focus on the diets of the poor but go on to question the regulatory measures in place for the entire food system (a huge challenge). That change would encourage not just talk about physical activity but also concrete measures, through the tax system and otherwise, to promote a variety of exercises.

Fourth, we should discuss issues relating to weight in the larger context of “health equity”: the fair distribution of determinants of well being regardless of social or economic standing. Lower income children often eat fewer fruits and vegetables and are frequently less active. But, critically, ask why the lives of such kids are that way. Examine the distribution of supermarkets, the availability of transportation, the safety of neighborhoods, access to parks, and opportunities for recreation and other factors that bound the day to day existence of deprived children.

The foregoing make up a tall order. Progress is unlikely to be quick or easy. A great deal of effort, debate, and just plain trial and error will be necessary. Whatever the outcome, embracing these and related strategies is better than obsessing about calories, invoking extreme measures in the name of weight loss, and beating up on the “fatties”.

W.A. Bogart is the author of several books including Permit But Discourage: Regulating Excessive Consumption and Regulating Obesity?: Government, Society, and Questions of Health.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Weight Scale and Stethoscope. © JerryB7 via iStockphoto.

The post The ups and downs of weight loss appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHope and healthPoverty and health in the United StatesIs obesity truly a public health crisis?

Related StoriesHope and healthPoverty and health in the United StatesIs obesity truly a public health crisis?

Hope and health

Socioeconomic disparities in health are among the most troublesome and refractory problems in medicine. Health disparities begin before birth and are lifelong. Babies born to poor, disadvantaged, or marginalized parents have an increased incidence of prematurity and low birth weight, a greater burden of disease and disability throughout life, and a shorter life expectancy than people of higher socioeconomic status. Health disparities are not simply a division along the poverty line: those below with bad health and those above with good health. There is a gradient in health, measured either in terms of the burden of disease and disability or in terms of life expectancy, that runs throughout the socioeconomic scale. Health disparities result in a tragic waste of human lives, talents, and opportunities.

Previous analyses of health disparities have focused on what biologists call proximate causes, causes that operate during the lifetime of an individual. People who have poor health may be unable to work, or unable to work at skilled or higher paying jobs, and so poor health may sometimes lead to poverty, but this accounts for only a small fraction of the association between poverty and health. Poor people may be forced to live in unhealthy neighborhoods where they are exposed to environmental toxins and violence. They may have to work in hazardous occupations where again they are exposed to toxins and suffer a high risk of injury. Disparities in access to health care also contribute to disparities in health. Nonetheless, disparities persist in countries such as the United Kingdom, which has a national health service and in which there are minimal barriers to access health services. Disparities in health education may also play a role but they are probably not a major factor. Disadvantaged people have a greater tendency to engage in risky or unhealthy behaviors, have unhealthy diets and lifestyles, and are less likely to utilize preventive health services, but these behaviors are not due primarily to lack of knowledge. Educational interventions to reduce unhealthy behaviors generally have not been successful.

Evolutionary life history theory provides valuable new insights into health disparities. Natural selection has shaped life histories to optimize reproductive fitness. We, like other animals, have evolved mechanisms that alter our life history trajectories in response to our assessment of the safety and security of our environment. Our life histories are modulated by hope—not conscious hope but environmental signals that our bodies interpret as hope of a long, active life. Signals of hope lead us to invest energy into growth and bodily maintenance, and to postpone reproductive maturity. Signals which indicate that our environment is uncertain, stressful, or dangerous lead to the diversion of resources away from bodily repair into early reproduction and to coping with acute stresses. From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense. We have evolved to balance the benefits of growing larger and repairing somatic damage against the need to mature fast enough to be able to reproduce and raise our children while we still have a reasonable chance of remaining alive.

Signals of a hostile or dangerous environment, which lead us to divert resources from somatic repair to early reproduction, include poor nutrition, psychosocial stresses such as social isolation, lack of material resources, and fear of violence, as well as prematurity or low birthweight and exposure to toxins, all of which are more prevalent among poor and disadvantaged groups than in higher socioeconomic classes. Environmental signals affect our life history strategies by modulating the activity of neuroendocrine regulatory pathways. Hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline suppress the immune system and reduce tissue repair. They enhance our responses to stress at the cost of reducing somatic maintenance. Socioeconomic gradients in the levels of these hormones or in the reactivity of these neuroendocrine systems may contribute to gradients in life histories and in health.

We appear to have evolved psychological biases as well as physiological mechanisms that are sensitive to our assessment the quality of our environment. Our psychological biases make us more likely to engage in healthy behaviors if our bodies believe that we will live long enough to benefit from these behaviors and lead us to discount our future health when we perceive our environment as hostile or dangerous.

The root causes of health disparities are disparities in wealth, status, and power, and the ways we have evolved to respond both physiologically and psychologically to the levels of stress and insecurity we experience in hierarchical, socioeconomically stratified societies. To reduce disparities in health we must reduce socioeconomic disparities, so that everyone develops under conditions that signify hope. Hope is a key to health and to ameliorating the tragedy of health disparities.

Robert Perlman is Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago and the author of Evolution and Medicine. His interests in social justice and in evolutionary medicine have fueled his concern about the evolutionary origins of health disparities.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Poverty via iStock photo

The post Hope and health appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe world of the woundedPoverty and health in the United StatesHealth care in need of repair

Related StoriesThe world of the woundedPoverty and health in the United StatesHealth care in need of repair

November 9, 2013

ADHD: time to change course

In March 2013, we learned that 11% of US children and teens have received an ADHD diagnosis, an increase of 41% in 10 years. Diagnoses among adults have sharply increased as well. Some ADHD experts welcome this change. They interpret these high rates as signs that much-needed attention is finally being given to people whose biology has been a disadvantage in work, school, and relationships. Other professionals have been taken aback by the current diagnostic rate and its purported repercussions, citing risks such as overprescription of drugs, medicalization of normal behaviors, and drug diversion to street use.

No general uproar has materialized, however. On the contrary, it’s looking like the upward trend will continue. Recent publications explain how to increase screening rates via computerized assessments, and how to hone diagnosis with a new EEG test. Most important, the new diagnostic guidelines in the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 relax the diagnostic criteria, pulling more people, especially adolescents and adults, under the “ADHD” umbrella. The ADHD therapeutics market has responded enthusiastically, predicting high profits from increased diagnostic rates.

Children and their teacher in a classroom

One reason for the lack of outcry might be that people see this as the continuation of a steady trend: same old, same old. Diagnostic rates have been increasing for decades. Another might be the continued sway of the pharmaceutical business. It has effectively hyped the diagnosis for 40 years through targeted medical education; advertising to physicians, patients, and parents; and a smorgasbord of perks for “opinion leaders” and clinicians.

I think, though, that the reason for accepting this status quo involves much more than the drug industry. Basically, a lot of people—and a lot of the social systems in which they participate—like the diagnosis.

Teachers and education administrators like it: Within the strained education system, it addresses needs of overworked teachers and overcrowded classrooms.

Physicians and medical insurers like it: It’s a win-win in the medical system because the diagnosis (in the predominant interpretation as a biological dysfunction in individuals) falls in physicians’ purview; current care is quick and easy, often consisting only of a prescription.

Clinical scientists like it: Research dollars flow toward it because the diagnosis—hence the fruits of research—promises to solve problems.

And of course parents and adult diagnosees, who typically self-refer, like it: The short-term effects of medication help with behavior issues they deal with, and the promise of long-term effectiveness gives them hope. (Never mind that long-term effectiveness has not yet been demonstrated.)

If so many people like the diagnosis, what’s the problem? The much-discussed worry that we are overusing psychotropics, especially in children, is worth reconsidering. But two other issues also need to be aired

The first is that the continued reliance on ADHD as a research category puts clinical science in a rut—repeatedly studying ADHD and non-ADHD groups assumes that ADHD is a relevant and important category. More research should question that assumption. Investigating other hypotheses opens avenues of research that might better address clinical needs, as well as leading to more knowledge about mental health and illness.

The second issue is the stigmatization of those who are diagnosed as having ADHD. Years of research has shown that ADHD diagnosis correlates with multiple life choices and outcomes generally considered negative, such as increased rates of accidents, substance abuse, poor relationships, low educational and work achievement, and higher medical and education expenses. Drawing attention to “ADHD” as a contributor to these life tracks puts the blame on supposed biological facts about the individuals. Then, despite efforts to spin attitudes toward compassion for these (putatively) inborn circumstances, the opposite often occurs. The correlation between ADHD diagnosis and negatively perceived life tracks instead provides a medically and scientifically justified target for social disapproval—that is, ADHD-diagnosed people are stereotyped and stigmatized. Alternatives suggest that the biological claims are at best incomplete, and that social circumstances require investigation and intervention as well.

For these reasons, I think that it is time for new directions. More specifically, it is time to reassess clinical and research needs, and to find new ways to address both without relying on the “ADHD” catch-all. However, arguments pointing to evidence of progress via the current direction and arguments favoring the vested interests in the status quo—economic, educational, medical, scientific, and personal—weigh in the opposite direction.

Should we change course? I welcome your ideas.

Susan C. Hawthorne, author of Accidental Intolerance: How We Stigmatize ADHD and How We Can Stop, is Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, St. Catherine University.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Children in a classroom by Michael Anderson, National Cancer Institute. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post ADHD: time to change course appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHope and healthThe world of the woundedPoverty and health in the United States

Related StoriesHope and healthThe world of the woundedPoverty and health in the United States

Cajal´s butterflies of the soul

Most scientific figures presented in the nineteenth century and first third of the twentieth century were the drawings of early neuroanatomists, such as Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) whose studies and theories had a profound impact on the researchers of his era and represent the true beginnings of the detailed analysis of the nervous system. Such illustrative work provided a valuable “pretext” for these scientists to express and develop their artistic talent.

Top left photograph, from left to right, (pictured standing): Giulio Bizzozero (1846-1901) and Camillo Golgi (1843-1926); (pictured sitting): Edoardo Perroncito (1847-1936), Rudolf Albert von Kölliker (1817-1905) and Romeo Fusari (1857-1919). Courtesy of Paolo Mazzarello, Pavia University. Top right photograph, Magnus Gustaf Retzius (1842-1919) (Legado Cajal). Drawings, from left to right, (middle row): taken from Retzius (1891), Golgi (1882) and Fusari (1887); (bottom row): taken from Kölliker (1893), Retzius (1894) and Retzius (1891).

Many of the illustrations of Cajal and other scientists can be considered to belong to different artistic movements, such as modernism, surrealism, cubism, abstraction, or impressionism. Cajal beautifully explained the combination of art and science in his book Recuerdos de mi vida-Historia de mi labor científica (“Recollections of my life-The story of my scientific work”, 1917), referring to the intellectual pleasure he felt when observing and drawing from his histological preparations:

My work began at nine o’clock in the morning and usually lasted until around midnight. Most curiously, my work caused me pleasure, a delightful intoxication, an irresistible enchantment. Indeed, leaving aside the egocentric flattery, the garden of neurology offers the investigator captivating spectacles and incomparable artistic emotions. In it, my aesthetic instincts were at last fully satisfied.

One of Cajal’s favorite topics was the study of the human cerebral cortex and he beautifully referred to the most common neurons in this brain region (the pyramidal cells) as the butterflies of the soul. He wrote at the beginning of his study of this region:

I felt at that time the most lively curiosity — somehow romantic — for the enigmatic organization of the organ of the soul. Humans — I said to myself — reign over Nature through the architectural perfection of their brains… To know the brain — we said to ourselves in our idealistic enthusiasm — is equivalent to discover the material course of thought and will… Like the entomologist hunting for brightly coloured butterflies, my attention was drawn to the flower garden of the grey matter, which contained cells with delicate and elegant forms, the mysterious butterflies of the soul, the beating of whose wings may some day (who knows?) clarify the secret of mental life … Even from the aesthetic point of view, the nervous tissue contains the most charming attractions. In our parks are there any trees more elegant and luxurious than the Purkinje cells from the cerebellum or the psychic cell that is the famous cerebral pyramid?

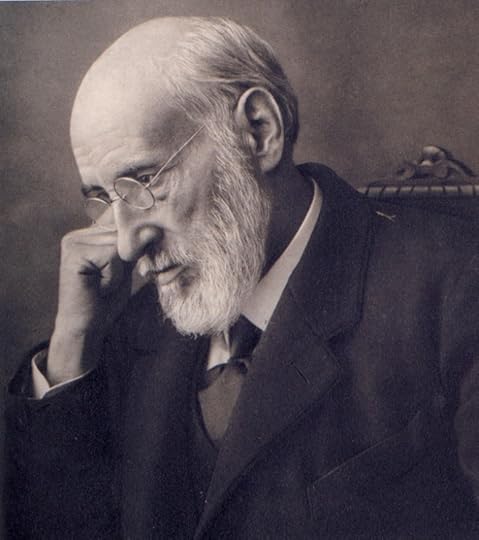

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, 1920.

While looking at the captivating old illustrations it is exciting to think about the nature of our brain in romantic prose terms, a way of thinking that unfortunately we have lost in modern scientific writing. These illustrations represent the basis of our current understanding of the nervous system and their study represents a fascinating journey through the history of neuroscience since, by their very nature, they were an “interpretation” of the microscopic world rather than a reflection of absolute accuracy. Any scientist, who has used hand drawings for scientific illustrations (as I did during my early days at the Instituto Cajal), would no doubt agree that this is the case. Like a painter of natural scenery, the scientists of the past did not reproduce the entire field of the histological preparations they observed through the microscope. They only illustrated those elements they thought to be important for what they wanted to describe. Therefore, it was not necessarily free of technical errors, making this early period of neuroscience an interesting page of history where the exchange of information between scientists was hindered by inevitable skepticism concerning findings. However, there can be little doubt that this era was also a golden period of art in neuroscience.

Javier DeFelipe, PhD is a Research Professor at the Instituto Cajal (CSIC) located in his hometown, Madrid, Spain. He is the author of Cajal’s Butterflies of the Soul: Science and Art.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: Both images courtesy of Javier DeFelipe.

The post Cajal´s butterflies of the soul appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMatching our cognitive brain span to our extended lifespanThe world of the woundedHealth care in need of repair

Related StoriesMatching our cognitive brain span to our extended lifespanThe world of the woundedHealth care in need of repair

A call to the goddess

In the first book of The Iliad, Homer calls for a muse to help him recount the story of Achilles, the epic Greek hero of the Trojan War. The poet begins his account nine years after the start of Trojan war, with the capture of two maidens, Chryseis by Agamemnon, the commander of the Achaean Army, and Briseis by the hero Achilles. We present a brief extract of the opening below, interspersed with audio recordings of it in Greek and English. Our poet here is classicist and author of a new free verse translation of the Iliad, Barry B. Powell.

The rage sing, O goddess, of Achilles, the son of Peleus,

the destructive anger that brought ten-thousand pains to the

Achaeans and sent many brave souls of fighting men to the house

of Hades and made their bodies a feast for dogs

and all kinds of birds. For such was the will of Zeus.

Sing the story from the time when Agamemnon, the son

of Atreus, and godlike Achilles first stood apart in contention.

Which god was it who set them to quarrel? Apollo, the son

of Leto and Zeus. Enraged at the king, Apollo sent an

evil plague through the camp, and the people died.

For the son of Atreus had not respected Chryses, a praying

man. Chryses had come to the swift ships of the Achaeans

to free his daughter. He brought boundless ransom, holding

in his hands wreaths of Apollo, who shoots from afar,

on a golden staff. He begged all the Achaeans, but above all

he begged the two sons of Atreus, the marshals of the people:

“O you sons of Atreus, and all the other Achaeans,

whose shins are protected in bronze, may the gods who

have houses on Olympos let you sack the city of Priam!

May you also come again safely to your homes. But set free

my beloved daughter. Accept this ransom. Respect

the far-shooting son of Zeus, Apollo.”

The First 100 lines of The Iliad in Greek:

All the Achaeans

shouted out that, yes, they should respect the priest

and take the shining ransom. But the proposal was not

to the liking of Agamemnon, the son of Atreus.

Brusquely he sent the man away with a powerful word:

“Let me not find you near the hollow ships, either

hanging around or coming back later. Then your scepter

and wreath of the god will do you no good! I shall not

let her go! Old age will come upon her first in my

house in Argos, far from her homeland. She shall

scurry back and forth before my loom and she will

come every night to my bed. So don’t rub me

the wrong way, if you hope to survive!”

So he spoke.

The old man was afraid and he obeyed Agamemnon’s

command. He walked in silence along the resounding

sea. Going apart, the old man prayed to his lord

Apollo, whom Leto, whose hair is beautiful, bore:

“Hear me, you of the silver bow, who hover over

Chrysê and holy Killa, who rule with power

the island of Tenedos—lord of plague! If I ever

roofed a house of yours so that you were pleased

or burned the fat thigh bones of bulls and goats,

then fulfill for me this desire: May the Danaänsº pay

for my tears with your arrows!”

So he spoke in prayer.

Phoibos Apollo heard him, and he came from the top

of Olympos with anger in his heart. He had on his back a bow

and a closed quiver. The arrows clanged on his shoulder

as he sped along in his anger. He went like the night.

He sat then apart from the ships. He let fly an

arrow. Terrible was the twang of the silver bow. At first

he attacked the mules and the fleet hounds. Then he

let his swift arrows fall on the men, striking them

with piercing shafts. Ever burned thickly the pyres

of the dead.

For nine days he strafed the camp with his

arrows, but on the tenth Achilles called the people to assembly.

The goddess with white arms, Hera, had put the thought

in his mind, because she pitied the Danaäns, when she saw

them dying.

When they were all together and assembled,

Achilles, the fast runner, stood up and spoke: “Sons of Atreus,

I think we are going back home, beaten again, if we

escape death at all and war and disease do not together

destroy the Achaeans. So let us ask some seer or

holy man, a dream-explainer—dreams are from Zeus!—

who can tell us why Phoibos Apollo is angry.

Is it for some vow, or sacrifice? Maybe the god

can accept the scent of lambs, of goats that we kill,

perhaps he will come out to ward off this plague.” So speaking

he took his seat.

The First 218 lines of The Iliad in English (from Barry B. Powell’s new free verse translation):

Kalchas arose, the son of

Thestor, by far the best of the bird-seers, who knows

what’s what, what will happen, what has happened.

He had led the ships of the Achaeans to Ilion by his seership,

which Phoibos Apollo had given him. He spoke to the troops,

wishing them well: “Achilles, you urge me, you whom Zeus

loves, to speak of the anger of Apollo, the king who strikes

from afar. Well, then I will tell you. But first you must

consider carefully. You must swear to me that you will

defend me in the assembly and with might of hand. For I’m

afraid of enraging the Argive who has the power here, whom

all the Achaeans obey. For a chief has more power against

someone who causes him anger, a man of lower rank.

Maybe he swallows his anger for a day, but ever

after he nourishes resentment in his heart, until he

brings it to fulfillment. Swear then, Achilles, that you will

protect me.”

The fast runner Achilles answered him:

“Have courage! Tell your prophecy, whatever you know.

By Apollo, dear to Zeus, to whom you yourself

pray when you reveal prophecies to the Danaäns—not so

long as I am alive, and look upon this earth, shall anyone

of all the Danaäns lay heavy hands upon you

beside the hollow ships, not even if you mean

Agamemnon, who claims to be best of the Achaeans.”

The seeing-man, who had no fault, was encouraged,

and he spoke: “The god is not angry for a vow, or sacrifice,

but because of the priest whom Agamemnon dishonored

when he would not release the man’s daughter. He would not take

the ransom. For this reason the far-shooter has caused these pains,

and he will go on doing so. He won’t withdraw the hateful disease

from the Danaäns until Agamemnon gives up the girl with

the flashing eyes, without pay, without ransom, and until he leads

a holy sacrifice to Chrysê. Only then might we succeed in

persuading the god to stop.”

Barry B. Powell is Halls-Bascom Professor of Classics Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He is the author of a new free verse translation of The Iliad by Homer.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A call to the goddess appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaps of The IliadThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wetteman Jr.Health care in need of repair

Related StoriesMaps of The IliadThe usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wetteman Jr.Health care in need of repair

The world of the wounded

I work regularly with wounded veterans and medics from Britain’s wars of the 21st century. Their stories have extraordinary resonance with those from a century earlier. Casualties feel the same fear and dread, whether in a freezing shell hole on the Western Front during an artillery barrage or trapped behind a dry mud wall in Afghanistan during a firefight, when rescue looks impossible. Time, whether in 1917 or 2012, slows to a crawl as they try to find their wound, to see how much they are bleeding and then remember that their comrade may have fallen too and that they should try to save others as well as themselves. The sobs of relief are the same when finally a medic makes their way to them, as is the dreadful incomprehension when the medic whispers for them to be quiet, that it is not quite safe enough for them to move, that they should stay low and keep calm. In the minutes or hours that pass while they wait, all the casualty knows is pain but also the small steady comfort of the medic’s hand in theirs, that they are not abandoned and that they will somehow get home.

A wounded soldier boarding a train.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Nurses and patients.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A medical kit.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A Great War medic and patient.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Stretcher-bearers carry a wounded soldier.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Great War ambulances, pulled by teams of horses, may seem a world away from the technologically advanced vehicles of today, but the journey taken by the men inside them has not changed a great deal. Stretchers are still stacked one on top of the other in frames with very little room in between. The casualties they carry can hear one another’s cries and, when those cries suddenly stop, are close enough to reach across to another body on a stretcher and feel that it is cold to their touch. The ambulance brings them to safety but it also takes them on a journey from which there is often no return. As the vehicle speeds along the broken roads common to all war zones and their stretchers bump and shake, soldiers realize they are leaving behind their comrades and their way of life as a serving soldier. They are suddenly dependent entirely on the skill and courage of others: from the stretcher bearer or combat medical technician who has got them as far as the ambulance, to the surgeon and operating staff who wait for them at the field hospital. What lies ahead is unknown — bright lights, the organized chaos of triage, tired but kind faces behind surgical masks — and then a whole different future from the one they envisaged in their battalion that morning. They have left behind one world and have begun the journey through another, going from soldier to patient with one shot from a rifle or blast from an artillery shell.

Emily Mayhew is a Research Associate at Imperial College and an examiner at the Imperial College School of Medicine. She is the author of Wounded: A New History of the Western Front in World War I. She is a consultant and lecturer to museums including the Wellcome Collection, the Imperial War Museum, and the Royal College of Surgeons.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images courtesy of the author.

The post The world of the wounded appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHealth care in need of repairPoverty and health in the United StatesWhy read radiology history?

Related StoriesHealth care in need of repairPoverty and health in the United StatesWhy read radiology history?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers