Oxford University Press's Blog, page 879

November 16, 2013

Five most influential economic philosophers

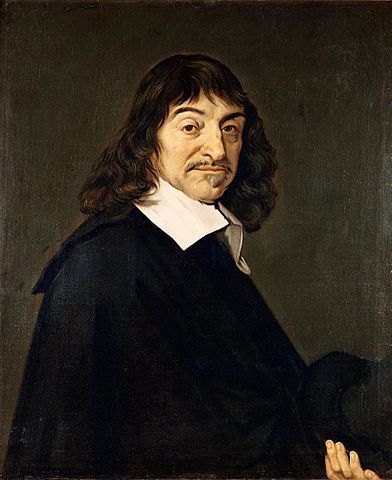

René Descartes

René Descartes

Descartes’s scientific approach to perceiving the world unquestionably represented a huge breakthrough, and this is doubly true for economists. We have seen that the notion of the invisible hand of the market existed long before Smith. Homo economicus has gained his (a)moral side from Epicurus, but he acquired his mathematical and mechanical part from René Descartes. Descartes’s ideas, of course, became absolutely key, if not determining, for the methodology of economic science. Economics started to develop at the time when his legacy received widespread recognition. The first economists widely discussed theories of knowledge, and all have proven to be successors to Descartes. His ideas were brought to England by John Locke and David Hume. Through them, Descartes’s teachings penetrated economics as well—and they have remained firmly built into it to this day. In no other social science were the Cartesian ideas accepted with as much enthusiasm as in economics.

Image of the title page of the 1705 edition of Bernard de Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees.

Bernard Mandeville

Bernard Mandeville is the true father of the idea of the invisible hand of the market as we know it today. The theory of the market’s invisible hand, which today is erroneously attributed to Adam Smith, left a deep mark on the morality of economics. It postulated that private ethics do not matter; anything that happens, be it moral or amoral, contributes to the general welfare. It’s not difficult to suspect that just at the moment when the principle of the invisible hand is trivialized, ethics becomes seemingly irrelevant. The originally universal notion of the relationship between ethics and economics, which we have already encountered in the Old Testament, was turned on its head. Together with Mandeville, the argument began that the more vices there were, the more material well-being there could be. It’s a certain historical irony that Adam Smith sharply and completely clearly distanced himself from the idea of the market’s invisible hand as Bernard Mandeville presented it.

John Locke

John Locke, a well-known defender of (almost absolute) property rights and one of the fathers of the Euro-Atlantic economic tradition, put forth a notion that private ownership has a beneficial influence on social calm, proper order, and positive motivational impulses. Locke argues this using both reason and faith: “Whether we consider natural reason, which tells us that men, being once born, have a right to their preservation, and consequently to meat and drink and such other things as nature affords for their subsistence, or ‘revelation,’ which gives us an account of those grants God made of the world to Adam, and to Noah and his sons, it is very clear that God, as King David says (Psalm 115:16), ‘has given the earth to the children of men,’ given it to mankind in common.” Human law must never infringe on the eternal laws of God. Not even private property laws can be placed above man as a member of human society. In other words, the institution of private property falls at the moment human life is at stake.

David Hume

David Hume contributed in great measure to the understanding of economic anthropology overall. He commented on key topics of economic interest such as the origin of social order, the theory of utility and self-love, and also the relationship between rationality and extrarationality. Hume was made famous by the passage that sets rationalistic anthropology on its head: “Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.” The passage more or less summarizes his philosophy—reason and feelings do not fight against each other and one is not set against the other. They are not lying on the same level so as to compete with each other. Human actions are led by feelings, passions, and affects, and reason plays its role only on a secondary level, in the process of rationalization.

Adam Smith

Adam Smith, an exceptional English thinker from the eighteenth century, is universally considered the father of modern economics. Adam Smith talks of a basic social principle of sympathy, which holds society together. The popular reading of Smith makes economics lopsided. For an understanding of the current state of economics it is therefore necessary to read both Smiths. Because if one focuses only on the popular side of Smith’s Wealth of Nations without having the broader context of The Theory of Moral Sentiments, one can easily reach conclusions that were not of Smith’s intentions. Smith did understand the crucial importance of ethics and gave it a major role and place in society, although his legacy is a bit confusing.

Tomas Sedlacek lectures at Charles University and is a member of the National Economic Council in Prague, where the original version of this book was a national bestseller and was also adapted as a popular theater-piece. He worked as an advisor of Vaclav Havel, the first Czech president after the fall of communism, and is a regular columnist and popular radio and TV commentator. He is the author of Economics of Good and Evil: The Quest for Economic Meaning from Gilgamesh to Wall Street.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images source: Public domain via Wikimedia

The post Five most influential economic philosophers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCorrelation is not causationCome together in Adam SmithInternational Day for Tolerance: A Q&A with Amos N. Guiora

Related StoriesCorrelation is not causationCome together in Adam SmithInternational Day for Tolerance: A Q&A with Amos N. Guiora

International Day for Tolerance: A Q&A with Amos N. Guiora

The United Nations International Day for Tolerance is observed every year on the 16th of November in order to raise awareness of the need for tolerance in today’s society and to promote understanding of the negative effects of intolerance. In 1996 (following The UN Year for Tolerance in 1995), the UN General Assembly (by resolution 51/95) invited UN Member States to observe the International Day for Tolerance, “Stressing that one of the purposes of the United Nations, as set forth in the Charter, is the achievement of international cooperation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural or humanitarian character and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.” In honor of the International Day for Tolerance we sat down with seasoned author Professor Amos N. Guiora, to talk about tolerance, extremism, international law, and his new book Tolerating Intolerance: The Price of Protecting Extremism.

What is the most pressing issue for the role of tolerance in international law right now?

One of the most important issues is recognizing extremism, understanding the dangers it poses, and determining what measures can and should be implemented to minimize its harmful impact on individuals and society alike. Based on my extensive travels and interviews conducted with a wide-range of experts in different countries, I believe we need to undertake a comprehensive comparative analysis of extremism. Recently, I focused on extremism is six different countries — Israel, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany — and how each address both domestic and international law with a particular emphasis on (the limits of) free speech.

How has thinking on addressing extremism evolved?

Over the course of my interviews with scholars, national security experts, policy experts, decision makers, people of faith, extremists and members of the media, I have found an increased understanding that society must address the question of “what are the limits that intolerance should be tolerated.” While there is, clearly and understandably, a lack of unanimity regarding the answer, the conversation needs to be frankly and candidly conducted.

How do you see the issue developing over the next few months/years?

My hope is that we engender discussion among different fields of study. In speaking with a broad cross-section of people, it became very clear that the core question — the limits of tolerating intolerance — cuts across many areas of study: in the academy, amongst decision makers, and for national security and law enforcement officials.

What are you reading about international law at the moment?

I’m reading a broad cross section of material related to my next writing project regarding the bystander in the death marches of the Holocaust. One of the issues I will be examining is whether the bystander fosters extremism. The project will examine the bystander through multiple perspectives including the law, morality, cultural-social realities of Germany and history.

What do you hope to see in the coming years from both the field and your academic work?

A direct contribution to addressing complex issues based on a sophisticated interdisciplinary approach.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to specialize in international law?

Try to understand the interaction between law and international relations/policy, and to understand the confluence of the two with a clear grasp of geopolitics.

If you weren’t a law academic what your alternative career be?

I always wanted to be a college football coach!

Amos Guiora is Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Center for Global Justice at the S.J. Quinney College of Law, the University of Utah, where he teaches Criminal Procedure, International Law, Global Perspectives on Counterterrorism and Religion and Terrorism. He is the author of Tolerating Intolerance: The Price of Protecting Extremism, Legitimate Target: Criteria-Based Approach to Targeted Killing, Freedom from Religion: Rights and National Security, and Constitutional Limits on Coercive Interrogation.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Old Greek columns in Athens – Passing Time Concept. © gregsi via iStockphoto.

The post International Day for Tolerance: A Q&A with Amos N. Guiora appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of JusticeRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!Is it a dog’s world?

Related StoriesThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of JusticeRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!Is it a dog’s world?

Is it a dog’s world?

Like a number of other traditional East Asian cultural phenomenon, such as kabuki, kimono, kimchee, and kung fu—just sticking to terms that start with the letter “k”—the koan as the main form of literature in Zen Buddhist monastic training has been widely disseminated and popularized in modern American society. Originally pithy and perplexing queries and anecdotes that are aimed at triggering a spiritual awakening beyond ordinary thought and discourse, including “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” and “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?,” koan cases are now practiced and discussed in diverse contemporary venues ranging from Zen centers to the popular media. Recently, a student showed me a koan app, although I soon found that the daily sayings it dispenses are rarely examples of actual Zen writings. This and other factors make me wonder how much, despite signs of fascination, is really known or understood today about the classic Chinese style of composition.

One of the features of traditional koan literature that needs to be assessed is the way many of the most famous cases incorporate imagery related to various animals as allegory. For example, in a case known as the Fox Koan, a monk appears in the form of a magical shape-shifting vulpine to symbolize a basic delusion about karma and moral causality; another example, the Cat Koan features monks quarreling over possession of a prized kitty, which is cut in half by the temple abbot to represent the pitfalls of attachment. In another instance an unwieldy water buffalo ironically has its whole body shoved through the window except for the tail. Also, a series of illustrations referred to as the Ten Ox-herding Pictures portrays a young boy taming the generally wayward and stubborn creature to signify the quest for mastering self-discipline.

Looking for the Ox

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

This is one of a series of ten images, generally known in English as the Ox-herding (or Bull-herding) pictures, by the 15th century Japanese Rinzai Zen monk Shubun. They are said to be copies of originals, now lost, traditionally attributed to Kakuan, a 12th century Chinese Zen Master.

Noticing the Footprints

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Catching Sight of the Ox

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Getting Hold of the Ox

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Taming the Ox

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Riding Home

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Ox Vanished, Herdsman Remaining

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Ox and Herdsman Vanished

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Returning to the Source

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Entering the Marketplace

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

This is the final one of a series of ten images, generally known in English as the Ox-herding (or "Ten Bulls") pictures, created by the 15th century Japanese Rinzai Zen monk Shubun. They are said to be copies of originals, now lost, traditionally attributed to Kakuan, a 12th century Chinese Zen Master.

What do these examples indicate about the traditional Chinese worldview and its message for the present day? The case about whether a dog can be considered to possess Buddha-nature suggests that the question concerning a dog’s spiritual quality is grounded in an admiration for what canines contributed to temple life by guarding and protecting the compound. Cats and dogs were both prized by Zen monks for their loyalty and efficiency in chasing noxious pests, such as rats or other rodents, or by scaring off intruders. Furthermore, it was sometimes said that the sound of a cat purring or a dog barking, like that of a donkey braying or other mundane natural sound like a pebble striking a stick, could help spark the enlightenment experience for someone needing one more seemingly trivial stimulus—like putting just a drop into a cup full of liquid so that it spills over.

Yet, Zen records, while appreciative of the positive qualities and occasionally allowing for the wise and loving canine, recalling the statue of the loyal Hachiko that commemorates an exceptionally faithful pet at Shibuya Station in downtown Tokyo, do not reflect a simplistic praising of animals, which also exhibit the seemingly inferior behavior of growling and prowling unproductively or not knowing how to control their own actions. In fact, Zen texts often treat the dog as representative of foolishness and folly, as in the comment, “Once a dog sees its shadow and starts barking, a thousand dogs are quickly barking, too,” reminding us of Biblical admonitions evoking canine that eat their own vomit or are not worthy of being offered the sacred.

Photo by Steven Heine, 2013.

In a sensational 1960s film called Mondo Cane (It’s a Dog’s World), an expose of decadent societies worldwide, scenes of Americans mourning the death of their dog are juxtaposed with those of Taiwanese butchering and skinning the animals to sell as meat. Probably, for better or worse, the Chinese worldview was closer to the latter stance. In fact, in an example of canine-based sarcasm, a Zen text comments, “[Buddha] hangs up the head of a sheep but sells the meat of a dog.” Note the irony that dog meat is sometimes euphemistically called “fragrant meat” or “mutton of the earth,” although there may be instances in which it is highly valued. Also, bewildered pilgrims are compared to dogs seen as scavengers chasing after clods or bricks tossed randomly rather than real prey, while foolish or demonic clerics are supposed to be thrown to the dogs or hunted down in the way a dog bites into a pig, reminiscent of a Biblical passage in I Kings concerning the punishment of Jezebel. In that vein, a master says of an errant monk, “If I had seen what he did at that time, I would have killed him with a single blow and handed him to the dogs to eat.”

The story of a famous monk’s enlightenment experienced under the watchful eye of his mentor is highlighted by a comment that a dog cannot help but try to lick hot oil while knowing better. An additional critique of squabbling monks indicates, “Noisily, they get caught up in disputes.” According to a comment on this line that uses onomatopoeia for the sound that growling dogs make, “Fighting over and gnawing at rotting bones – crunch! snap! howl! roar!” Disciples who remain attached to selfhood, rather than attaining freedom from this delusion, are likened to the sorry behavior of “a mad dog that is always trying to get more and more to eat.”

“In the East,” it was said by a nineteenth-century traveler, “the dog is cruel and blood-thirsty—a gloomy egotist, cut off from all human intercourse.” Yet, it seems that the sometimes lovable creatures sometimes get the last laugh in koan literature when a poetic comment on the case suggests that monks, “Had to endure being mocked by howling dogs / Who, in the dead of night, started barking in the vacant hall.” When it comes to the matter of having Buddha-nature or not having it, one master claims that a dog “has a hundred thousand times more than a cat!”

Steven Heine is an authority on East Asian religion and society, especially the history of Zen Buddhism and its relation to culture in China and Japan. He has published two dozen books, including Like Cats and Dogs: Contesting the Mu Koan in Zen Buddhism, Dogen: Textual and Historical Studies, Did Dōgen Go to China?: What He Wrote and When He Wrote It, and White Collar Zen: Using Zen Principles to Overcome Obstacles and Achieve Your Career Goals.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: The Ox-herding pictures. In the tradition of Zen Buddhism, this series of ten images is used as an analogy for the stages of a practitioner’s progression towards, and of, Enlightenment. Inked by the 15th century Japanese Rinzai Zen monk Shubun. From Museum of Shokoku-ji Temple. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is it a dog’s world? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesPicturing printingClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years ago

Related StoriesA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesPicturing printingClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years ago

November 15, 2013

Catching up with Marcela Maxfield

The publishing industry can be a little mysterious for those of us who don’t work inside it. I sat down with Religion & Theology Editorial Assistant Marcela Maxfield to discover the daily grind of one of the many people at Oxford University Press (OUP) who shepherd books from idea to crisp bound paper.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

One of my professors in college was published by OUP and he suggested that I email his editor to ask about internship possibilities. Now when I look back I think that if I had known more about the company, or that the internship might turn into a full-time job, I would have been way more stressed out about applying for it.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

I think everything was surprising at first: the amount of detail at each stage of the process; the number of people responsible for one book; the number of books one person is responsible for (see what I did there?). This is my first experience in publishing and the first year has been a huge learning curve. Actually, that might be the most surprising thing I’ve found: how much I didn’t know about the industry.

What’s the least surprising?

The least surprising thing I’ve found about working at OUP… the books, I guess? I was pretty sure those would be a part of the deal.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first year on the job?

Write everything down! We’re working on so many different things simultaneously that unless it goes on the to-do list, it will be immediately erased from my brain.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Check my email.

If you could change one thing about working for OUP, what would you change and why?

The cubicles. One day I got a headache from staring at my computer screen. When I tried to look around to give my eyes a rest, I realized that almost every surface around me is less than four feet away from my face. I might be slightly claustrophobic, though.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

Paper from a fortune cookie that says “You love Chinese Food”.

What are you reading right now?

What are you reading right now?

I just finished Bossypants by Tina Fey.

Open the book you’re currently reading and turn to page 75. Tell us the title of the book, and the third sentence on that page.

In Between Days. “The girl in the pool.”

What’s your favorite book?

I don’t think I have one favorite book, but the one that inspired me to study literature in a serious way was Life of Pi by Yann Martel.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

Sunscreen (that’s just practical)

Tarp (because every survival story involves someone’s life getting saved by collecting rainwater or building a fort with it)

Sawyer from Lost (#teamsawyer)

Who inspires you most in the publishing industry and why?

I’m inspired by many of the people I work with—a lot of intelligent, ambitious, and kind people.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

According to my to-do list it looks like I will be updating some of my review projects. Part of my job is sending out proposals or manuscripts we are considering for publication. This involves sending invitations to scholars in the field and, if they agree, mailing them the material for review.

Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

There have been two times this last year when I’ve been able to suggest ideas for books, one for a series called What Everyone Needs to Know, and another for a group trying to come up with books that use popular online content. The feeling that I am contributing creatively to this company is very gratifying.

Marcela Maxfield is an Editorial Assistant on the Religion and Theology list. She started working at OUP at the end of September 2012. She previously interned briefly on the Economics list.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Life at Oxford articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Catching up with Marcela Maxfield appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesLife as an OUP internClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years agoRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!

Related StoriesLife as an OUP internClimbing Pikes Peak 200 years agoRihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!

Climbing Pikes Peak 200 years ago

Today marks the anniversary of an event little remembered but well worth noting.

On 15 November 1806, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike paused on the high plains in what is now Colorado, peered through his spyglass, and saw the mountain that would later bear his name, Pikes Peak.

A contemporary of Lewis and Clark, Pike commanded a US military expedition that was exploring the southwestern reaches of the Louisiana Purchase. Believing a view from the summit would disclose the geography of the surrounding region, he decided to climb it.

On the 17th, Pike wrote that the party “pushed with an idea of arriving at the mountains, but found at night, no visible difference in their appearance.” The men marched for a week, and then on the 24th, he departed with three men “with an idea of arriving at the foot of the mountain.” They camped that night on the prairie, still miles from its base.

Distance had fooled him. American geographers had never seen the Rocky Mountains but most believed them to be about the size of more familiar eastern ranges. On first seeing them rise over the horizon, Pike compared them to the Alleghenies.

Supposing them to be much smaller than they were, he also assumed they were closer. The possibility of seeing a mountain more than a hundred miles away was not something he could wrap his eastern mind around.

On the 26th, once again expecting to ascend the peak that day, he cached his food and blankets. For all of the ten hours of daylight the sun gave them, he and his comrades labored.

They hiked up drainages and contoured hillsides. Sometimes, Pike wrote, the rocks were “almost perpendicular.” By late afternoon, as the last rays of sun melted behind the mountains, the party came to a steep incline.

The peak had remained hidden from view all day, blocked by intervening lesser summits. Perhaps to get a look at the terrain that separated them from their objective, they started up the slope, toward a pinnacle that appeared to be the highest in the vicinity.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Pike's view of Pikes Peak from Mt. Rosa.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Pike's view of Mount Rosa on the afternoon of November 26th.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Looking west near the spot where Pike first sighted Pikes Peak, more than a hundred miles from the summit.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Cave Pike and his three companions slept in on the slope of Mt. Rosa. The sign was erected by John Murphy.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Pikes Peak as Pike would have seen it.

For thirty or forty minutes they battled the mountain, clawing up a sheer face by grasping with weary limbs the jagged edges of boulders and the branches of fallen trees.

Finally, they found a cave, a crevice really, just big enough for four tired, hungry men without blankets. With daylight waning and the temperature falling, they crowded into this rocky hostel and shared body heat while they tossed and wriggled all night, seeking a comfortable surface to permit sleep.

They awoke the next morning, Thanksgiving Day, to a sublime view. Clouds overhung the endless prairies stretching out to the east, while the sky above was clear and blue.

They hiked more easily at first, reaching the shoulder of the mountain in a few minutes and then walking a half-hour along the ridgeline toward the cone of the peak. Then it was back to boulder scrambling and hoisting themselves by crags and branches, soon in waist-deep snow.

Another half hour brought them to the top and a 360-degree view that revealed a sight both awesome and dispiriting.

“The Grand Peak,” Pike recorded, “now appeared at the distance of 15 or 16 miles from us, and as high again as what we had ascended, and would have taken a whole day’s march to have arrived at its base, when I believe no human being could have ascended to its pinical.”

Coloradans delight in claiming that Pike thought the peak would never be climbed. Well-fed modern hikers enjoying the benefits of plastic, nylon, Thinsulate, and Gortex have had little difficulty accomplishing what Pike could not.

But Pike meant only that the summit could not be reached under the circumstances. That is, men who had not eaten in thirty-some hours and who lacked the provisions to bear another day in the wilderness could not climb it.

He made this context clear by adding, “The condition of my soldiers who had only light overalls on, and no stockings…, the bad prospect of killing any thing to subsist on, with the further detention of two or three days, which it must occasion, determined us to return.”

Although the Grand Peak defeated him, he and his expedition continued. Pike’s maps and journals would one day guide Santa Fe Trail traders and Rocky Mountain fur trappers. First, however, he regathered his men and led them into the mountains by another route. It was “snowing very fast.” “The hardships…had now began.”

Jared Orsi is Associate Professor of History at Colorado State University. He is the author of Citizen Explorer: The Life of Zebulon Pike and the prizing-winning Hazardous Metropolis: Flooding and Urban Ecology in Los Angeles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: All images courtesy of the author Jared Orsi

The post Climbing Pikes Peak 200 years ago appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesIlluminating the Mediterranean’s pre-historyPicturing printing

Related StoriesA brief history of Oxford University Press in picturesIlluminating the Mediterranean’s pre-historyPicturing printing

Rihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt!

Robyn Fenty — Rihanna to most of us — enjoyed victory in the English High Court earlier this year when she succeeded in stopping High Street fashion retailer Topshop from selling an unauthorised t-shirt bearing her image. 12,000 units of this t-shirt were sold, most at £22 each.

Some retailers sell clothing and accessory ranges endorsed by celebrities in carefully choreographed commercial partnerships, such as LK Bennett’s link-up with Rosamund Pike and Dorothy Perkins’ Kardashian Kollection. Some of that gear will bear the name or image of the celebrity. On other occasions, products bearing the likeness of a celebrity, such as the t-shirt in this case, will be created and marketed without the involvement or consent of the celebrity. Here, the t-shirt was entirely unauthorised. The image itself was acquired legitimately from the photographer who took it during a photoshoot for the video to Rihanna’s single “We Found Love”. Rihanna thus had no claim for infringement of copyright. Nor did she attempt to rely on any privacy laws.

Instead Rihanna relied on trade mark and “passing off” law. She claimed that the sale of the t-shirt gave the false impression to the public that she had endorsed or authorised it. The sale damaged the goodwill she enjoyed in her image and robbed her of the royalties and other income she would have commanded had she agreed to the t-shirt’s production.

In considering her claim, the judge in the High Court, Mr Justice Birss, was cautious. There is no distinct “image right” in English law which allows celebrities and other high-profile figures to control the use of their name and likeness. Instead, those with valuable personalities have had to rely on one or more of trade mark, passing off, copyright, and privacy laws. So far as passing off is concerned, the celebrity has to prove they enjoy “goodwill” in their image — essentially public recognition linking it to them; that the public is deceived by the t-shirt into thinking that the celebrity authorised it — so the t-shirt involves a “misrepresentation” — and that such misrepresentation causes the celebrity damage. The judge decided that the burden was on Rihanna to prove the key requirement; that there was a misrepresentation. He noted that it was “certainly not” the law that “the presence of an image of a well known person on a product like a t-shirt can be assumed to make a representation that the product has been authorised.”

However, having considered all the facts in this case, he found in favour of Rihanna and agreed there was a misrepresentation.

Topshop didn’t just put Rihanna’s image on a t-shirt. They had made a considerable effort to emphasise a connection between them and Rihanna. They ran a competition for a personal shopping appointment with Rihanna. They tweeted when Rihanna visited its flagship store. They made other statements on social media. Topshop sought “to take advantage of Rihanna’s public position as a style icon.” Coming from the video photoshoot, Rihanna fans and Topshop customers might think the image used on the t-shirt was part of the marketing campaign for the track and associated album. So taking everything into account, the judge felt that a substantial portion of those considering buying the product — namely, Rihanna fans — would think that the garment was authorised. As fans, they regarded Rihanna’s endorsement as important. “She is their style icon,” the judge remarked.

As a “cool” celebrity and style icon, Rihanna clearly enjoyed goodwill in her image, having worked with H&M, Gucci, Armani, and River Island to collaborate on and/or design clothing. Damage was obvious as noted above. The judge therefore held that Topshop was committing passing off, and Rihanna was successful. The judge’s concluding paragraph begins “The mere sale by a trader of a t-shirt bearing an image of a famous person is not, without more, an act of passing off.” So although celebrities may see the decision as supporting their attempts to control their image, the judge was sure to establish that the general rule — or perhaps the starting point — was against them.

Nevertheless, fashion and a number of other types of retailers (such as the card shops which sell celebrity face masks or greetings cards with celebrities on them) should pay close attention to this judgment. It might be acceptable in principle to apply celebrity images to one’s products, but one should not do it without giving careful consideration to the impact that application will have to a customer’s impression of the manufacturer’s relationship with that celebrity. This is particularly important if a business already has some association, however limited, with the individual in question.

It is interesting to consider on what basis the judge reached his decision that Rihanna fans would be deceived. Trade mark infringement and passing off cases often consider direct evidence from members of the public, so the judge can see first hand whether people are confused. In recent months, the English courts have become resistant to this kind of evidence; or rather the manner in which it is collated – by “witness collection exercises”. Lawyers have been left scratching their heads to how to prove to the judge whether or not people are confused. Perhaps as a result of this judicial attitude, there was no evidence from confused consumers in this case. Instead, the judge had to put himself into the mind-set of a 13- to 30-year-old female and decide what they would think. Sensible and appropriate as Mr Justice Birss’s judgment was, one might think there must be benefit in judges hearing something from the very public which passing off law is designed to protect (along with traders’ goodwill) before coming to their decisions.

Darren Meale is a senior associate solicitor specialising in intellectual property litigation. He was previously at Dentons in London and will soon join Simmons & Simmons. He also sits as a Deputy District Judge in the County Court. He is the author of “Rihanna’s face on a T-shirt without a licence? No, this time it’s passing off” in Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, available to read for free for a limited time.

Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (JIPLP) is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to intellectual property law and practice. Published monthly, coverage includes the full range of substantive IP topics, practice-related matters such as litigation, enforcement, drafting and transactions, plus relevant aspects of related subjects such as competition and world trade law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image courtesy of the author.

The post Rihanna takes on Topshop: Get my face off that t-shirt! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of JusticeWhite versus black justiceForeign direct investment, aid, and terrorism

Related StoriesThe concept of ‘international community’ and the International Court of JusticeWhite versus black justiceForeign direct investment, aid, and terrorism

A brief history of Oxford University Press in pictures

Oxford University has been involved with the printing trade since the 15th century and our Archive holds the records of the University’s printing and publishing activities from the 17th century to date. This week our archivists have generously unearthed some pictures to share with you. From the printing activities at Clarendon Street and the Wolvercote Mill, to our New York office and Melbourne trams, we hope they provide some insight into how our Press has grown and evolved over the years.

Wolvercote Mill exterior.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Watercolour, 1826, by J. Buckler, showing the mill when it was owned by the Swan brothers. Oxford bought the mill in 1855. The original of this image hangs in the stairwell outside Nigel Portwood’s office. From Volume 2 of The History of the Oxford University Press.

The Press Band

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Established by the Printer, Thomas Combe, in the mid-19th century. This shot is from 1874. From Volume 2 of The History of the Oxford University Press.

The printing house, Walton Street

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

General shot, c. 1930. From Volume 3 of The History of the Oxford University Press

Paper at Wolvercote

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Designated for the New English Bible. The NEB was a huge project for the Press. The New Testament was published first, in 1961. From Volume 3 of The History of the Oxford University Press

OUP New York, West Thirty-Second Street.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

New York was Oxford’s first non-UK office, opened in 1896. From Volume 3 of The History of the Oxford University Press

Melbourne tram advertising OUP Dictionaries, c. 1970.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

We have no other information on this – but it does show the ingenuity of Oxford’s sales’ team! From Volume 3 of The History of the Oxford University Press.

To celebrate the publication of the first three volumes of The History of Oxford University Press on Thursday and University Press Week, we’re sharing various materials from our Archive and brief scholarly highlights from the work’s editors and contributors. With access to extensive archives, The History of Oxford University Press is the first complete scholarly history of the Press, detailing its organization, publications, trade, and international development. Watch a silent film, learn about arguments over the first printing press in Oxford and when the Press began, or discover printing in the Sheldonian Theatre in our previous posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Oxford from above at sunset. © Andrea Zanchi via iStockphoto.

The post A brief history of Oxford University Press in pictures appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPicturing printingWhen did Oxford University Press begin?Oxford University Press and the Making of a Book

Related StoriesPicturing printingWhen did Oxford University Press begin?Oxford University Press and the Making of a Book

The uncanny Stephen Crane

By Fiona Robertson and Anthony Mellors

Stephen Crane’s birthday, 1 November 1871, falls on All Saints Day, the morning after the ghouls of the night before. Much of Crane’s writing, from the social critique of his first novel Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893) to his last-published, Active Service (1899), deals with the hard realities of urban-class American life in the last decade of the nineteenth century, a reaction against what he called the ‘velveteen romanticism’ of Robert Louis Stevenson and the cultural prestige of historical, high-society, and international fictions (claimed by writers such as Henry James and Edith Wharton). Closely associated with a group of writers dedicated to refashioning American fictional style, and with his roots in journalism and popular entertainment, Crane produced in his Civil-War tale The Red Badge of Courage (published in serial form in 1894 and, revised, as a single volume in 1895) an uncompromisingly spare modern account of the first-hand experience of battle. Early reviewers of The Red Badge tend to praise its realism as a successor to, and an improvement on, the accounts of battle given in Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) and Zola’s La Debacle (1892). According to George Wyndham, writing in 1896, Zola’s novel ‘is his own catalogue of facts made in cold blood, and not the procession of flashing images shot through the senses into one brain and fluctuating there with its rhythm of exaltation and fatigue.’ Crane’s impressionism is recognized, too, if sometimes negatively; for Nancy Huston Banks, the novella is

a study in morbid emotions and distorted external impressions…The few scattered bits of description are like stereopticon views, insecurely put on the canvas. And yet there is on the reader’s part a distinct recognition of power - misspent perhaps - but still power of an unusual kind. As if to further confuse this intense work, Mr. Crane has given it a double meaning - always a dangerous and usually a fatal method in literature. (Bookman, November 1895)

Stephen Crane in military uniform in 1888, aged 17

Yet there is little sense that this doubling is the effect of irony, which later readers and critics come to see as essential to Crane’s art. Doubling is a constituent of the uncanny, which Tzvetan Todorov defines as textual undecidability, so that readers cannot say whether meaning is located in the supernatural or the psychological. If The Red Badge of Courage is phantasmatic, its hallucinatory aspects are closer to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) than to James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898). While its undecidability seems fundamentally to do with questions of context and interpretation – are we dealing with a veiled account of a real Civil War battle or being invited to see martial strivings as mythology? Are we being offered a bildungsroman leading to an epiphany of individuation or a caustic narrative of ironies based on the self-deception of the protagonist? – there are strong uncanny elements, for example in the uncertain moments between life and death, where the beard of a corpse moves in the wind ‘as if a hand were stroking it’, and in the ‘green chapel’ episode the ‘liquid-looking’ eyes of a dead soldier exchange a ‘long look’ with Henry Fleming, the living observer. And, from the very beginning, Crane blurs the distinctions between human agency and animism, the natural and the monstrous, subjecting the martial spin on ‘manliness’ to intense irony.The most compelling moments in Crane’s fictions come from experiences of an uncanny facelessness. In the disturbing novella The Monster (1897), Henry Johnson, his face burned away, meets — or seems to meet — the eye of Judge Hagenthorpe from behind his bandages, so that the judge falls silent, kept from further speech ‘by the scrutiny of the unwinking eye, at which he furtively glanced from time to time’. These are multiply-haunted passages, moments in which a host of literary and cultural memories, from the boat-stealing episode of William Wordsworth’s The Prelude to the open eye of Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’, creep across readers’ encounters with Crane’s text. The Monster as a whole powerfully evokes, and scrutinises, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, giving readers on the cusp of literary modernism an even ‘newer’ Prometheus, and a pressingly updated scene of racial injustice and exclusion. Crane himself occupied worlds in which dead eyes and blanked-out faces both haunted and goaded him. He died, aged 28, in the middle of the first year of the new century, 1900, his body brought back from Badenweiler in the Black Forest for burial in Hillside Cemetery, New Jersey. His last settled home was the Elizabethan manor-house of Brede Place in East Sussex, a house reportedly among Britain’s ‘most-haunted’, and where he and his friends performed a play about one house-spectre, Sir Goddard Oxenbridge, at Christmas 1899. Crane’s uncanniness, a restless ‘unhomeliness’, sees him always between traditions, literary and national; part of the experimental line in nineteenth-century American writing, from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville to Emily Dickinson and Henry James, while also shaping the expression of European experience, an ironic spectre in the war-poetry of 1914-18 and in the post-war fictions of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf.

Fiona Robertson, Horace Walpole Professor of English Literature at St Mary’s University College, and Anthony Mellors, Reader in Poetry and Poetics at Birmingham City University, co-edited the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Red Badge of Courage and Other Stories.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog. Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Stephen Crane in military uniform [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The uncanny Stephen Crane appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe many “-cides” of DostoevskyAsbo, Jago, and chavismo: What party hat for Arthur Morrison?Reading close to midnight in a leather armchair

Related StoriesThe many “-cides” of DostoevskyAsbo, Jago, and chavismo: What party hat for Arthur Morrison?Reading close to midnight in a leather armchair

Correlation is not causation

By Stephen Mumford and Rani Lill Anjum

Causation as correlation

A famous slogan in statistics is that correlation does not imply causation. We know that there is a statistical correlation between eating ice cream and drowning incidents, for instance, but ice cream consumption does not cause drowning. Where any two factors – A and B – are correlated, there are four possibilities: 1. A is a cause of B, 2. B is a cause of A, 3. the correlation is pure coincidence and 4., as in the ice cream case, A and B are connected by a common cause. Increased ice cream consumption and drowning rates both have a common cause in warm summer weather.

Nevertheless, there is a prominent philosophical view in which correlation and causation are brought very close together. David Hume (1711-1776), in A Treatise of Human Nature, argued that causation is little more than correlation. All we know is that the cause and effect regularly and constantly occur together, that the cause happens before the effect, and that they occur next to each other in space. It seems, then, that to Hume correlation is sufficient to infer causation, as long as the other two conditions are met.

Why correlations?

Why assume that causation is linked to correlations at all? No correlation discovered in science is a perfect one, after all. There is no ‘constant conjunction’, as Hume called it.

We know that smoking causes cancer. But we also know that many people who smoke don’t get cancer. Causal claims are not falsified by counterexamples, not even by a whole bunch of them. Contraceptive pills have been shown to cause thrombosis, but only in 1 of 1000 women. Following Popper, we could say that for every case where the cause is followed by the effect there are 999 counterexamples. Instead of falsifying the hypothesis that the pill causes thrombosis, however, we list thrombosis as a known side-effect. Causation is still very much assumed even though it occurs only in rare cases.

We know that smoking causes cancer. But we also know that many people who smoke don’t get cancer. Causal claims are not falsified by counterexamples, not even by a whole bunch of them. Contraceptive pills have been shown to cause thrombosis, but only in 1 of 1000 women. Following Popper, we could say that for every case where the cause is followed by the effect there are 999 counterexamples. Instead of falsifying the hypothesis that the pill causes thrombosis, however, we list thrombosis as a known side-effect. Causation is still very much assumed even though it occurs only in rare cases.

Correlations are usually now thought of as coming in various strengths. If one changes one variable x, and another, y, regularly changes with it, we take it to indicate some kind of causal connection. But do even these, sometimes weak, correlations constitute causation? Or are they mere signs of it?

Causes as tendencies

Perhaps we need to look for what would be behind such correlations. One could understand a cause, for instance, as a tendency towards its effect. Smoking has a tendency towards cancer, but it doesn’t guarantee it.. Contraception pills have a tendency towards thrombosis but a relatively small one. However, being hit by a train strongly tends towards death. We see that tendencies come in degrees, as do causes, some strongly tending towards their effect and some only weakly.

An essential feature of causation seems to be that an effect can be counteracted additively: by adding something to the situation that tends away from the outcome. We use seat belts, fire alarms, motorcycle helmets, and a number of other security systems, all in the hope of preventing or at least minimizing the effect should the cause happen.

If we believed that a cause was always and necessarily correlated with its effect, there would be no point in trying to interfere additively. All we could then do to prevent an outcome is to make sure that the cause never happens. Let’s say we wanted to avoid high blood pressure. Instead of taking medication, we could remove one or more of the causal factors tending towards high blood pressure: salt, stress, smoking, fat, and so on. We could call this subtractive interference.

Causation in science

Does it matter to science whether we link causation to correlations or tendencies? Arguably so. If we look for causation through correlation data, there might be some tendencies that are too weak to count as scientifically significant. Does this mean that causation is not established?

There are two ideas of causation that seem to go in opposite direction. One is that causation requires robust correlations. The other is that all causal laws are true only ceteris paribus: under ideal conditions. So while most laws of physics are concerned with what happens in vacua, free from any disturbing factors, the world we live in is admittedly not like this.

The first idea, of robust correlation, suggests that if the cause occurs in a variety of contexts, the effect should still occur. This is important when we use statistics to look for causes. The second idea, however, suggests that contextual variation would affect causation. In experiments, for instance, we observe the cause under different conditions to see how it changes the outcome.

Correlation is not causation

If causes are tendencies that can be counteracted by other tendencies, this should change the way we think of causation, away from Hume’s idea of causation as constant conjunction.

Rather than thinking that robust correlations are indicative of causation, they should be taken as evidence for something other than causation. Identity, classification and essence are typical candidates for robust correlations. All water is H2O, all whales are mammals and all humans are mortal. Such truths are not subject to interference and the first thing is always correlated with the second. They do not need ceteris paribus qualifying. In contrast, causal truths share none of these features.

Correlation does not imply causation. At best it might be taken as indicative or symptomatic of it. And perfect correlation, if this is understood along the lines of Hume’s constant conjunction, does not indicate causation at all but probably something quite different.

Stephen Mumford is Professor of Metaphysics at the Department of Philosophy, University of Nottingham, and Dean of the Faculty of Arts. He has written several books on this topic, including Dispositions (OUP, 1998), Laws in Nature (Routledge, 2004), Getting Causes from Powers (with Rani Lill Anjum, OUP, 2011), and Metaphysics: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2012). You can see the latest from him on Twitter –

@SDMumford

Rani Lill Anjum is Research Fellow at the Norwegian University of Life Science where she leads the Causation in Science research project (CauSci). CauSci is a global network for those interested in a scientifically informed philosophy of causation. She has written many popular articles in magazines and newspapers and delivered numerous talks for non-specialist audiences. She is the co-author of Getting Causes from Powers (OUP, 2011). She is also on Twitter –

@ranilillanjum

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook. Subscribe to on Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: 1) Contraceptive pill, by Bryancalabro (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons 2) David Hume, by Allan Ramsay [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Correlation is not causation appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMeasurement doesn’t equal objectivityThe Battle of Thermopylae and 300Astrobiology: pouring cold asteroid water on Aristotle

Related StoriesMeasurement doesn’t equal objectivityThe Battle of Thermopylae and 300Astrobiology: pouring cold asteroid water on Aristotle

November 14, 2013

Illuminating the Mediterranean’s pre-history

It’s no wonder that the Mediterranean basin—centered on the world’s largest inland sea, blessed by a subtropical climate, and host to nurturing rivers—gave birth to several ancient civilizations. What many don’t realize, however, is that the Mediterranean’s pre-classical history was just as rich as its geography, and just as instrumental in priming the region for success.

In The Making of the Middle Sea, Cyprian Broodbank tells the epic story of the early Mediterranean, from pre-human prehistory to the threshold of the classical era. Drawing on archaeological evidence, he sheds light on the previously overshadowed pluck and progress of the earliest humans of the region. Below are a few of the images of historical findings in early Mediterranean history.

Vesuvius

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

An eruption of Vesuvius, one of the youngest but most violent volcanoes in the Mediterranean, as witnessed by William Hamilton and the artist Pietro Fabris from across the Bay of Naples on the lit-up night of 8th August 1779. Illustration by Pietro Fabris. From Hamilton, W., 1776-79, Campi Phlegraei, Naples

Cyrene

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Cyrene, set amidst the fully Mediterranean environment of the uplands of the Jebel Akhdar (‘green mountain’), between Benghazi and Tobruk in present-day northeast coastal Libya. The Classical ruins largely obscure the remains of the first, late 7th-century BC southern Aegean foundation. Photo Susan Kane.

Sardinian Engraving

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

An 18th-century AD engraving, easily recognizable as a record of an early 1st- millennium BC Sardinian bronze figurine, from the Caylus collection. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

Roundhouses

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The loose collection of roundhouses constituting the early Cypriot village of Shillourokambos, set in this reconstruction within a savannah-like landscape with semi-free-ranging yet carefully managed herds. Excavations of Jean Guilaine. Computer graphics. © Simple Past/ Marc Azéma

Rock engraving

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Early rock engraving of cattle being milked at Tiksatin, Libyan Sahara © David Mattingly

Iceman

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

A reconstruction of the Iceman on the move, including cold-weather grass cape, knapsack, bow and other equipment. Drazen Tomic (after Tracy Wellman)

Reed Boat

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Experimental travel in a hypothetical reed boat. Photograph Catherine Perles. Courtesy Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Nautical Traditions.

Rock of Gibraltar

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The rock of Gibraltar, as it looks today and as it might have appeared during phases of lower sea level to the Neanderthals occupying large caverns along its base © Gibraltar Museum 2006

Cyprian Broodbank is Professor of Mediterranean Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. He is the author of The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World and An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades (winner of the 2002 AIA James R. Wiseman award).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Illuminating the Mediterranean’s pre-history appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesMaps of The IliadBowersock and OUP from 1965 to 2013Picturing printing

Related StoriesMaps of The IliadBowersock and OUP from 1965 to 2013Picturing printing

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers