Oxford University Press's Blog, page 883

November 9, 2013

Footloose jobs, rootless machines

Five years after the onset of the global financial crisis and the recession that followed, jobless growth seems to be the buzz-phrase for describing the economic landscape today; and even that ambiguously happy phrase refers to those economies that are growing. The US economy, supposedly the one bright spot on the global economic stage has over two million fewer people employed than five years ago, and the share of adults working or looking for work is the lowest since 1978. The labor force is increasingly a mix of part-time, temporarily employed and self-employed, and the lion’s share of jobs created is in low-paying personal services and retail occupations. The emergence of emerging markets has been delayed and the rapid increase in their labor forces temporarily stalled. India is battling a serious economic crisis on many fronts, Brazil has faced popular unrest over the economy, and even China seems to be settling into a lower growth mode.

Is the job creation “machine” of a modern economy finally succumbing to those other machines? Are the footsteps of the marching army of robots getting closer and closer? Is the combination of globalization/offshoring and mechanization/computerization sounding the death knell for decent employment prospects everywhere?

For many years now, the offshore migration of jobs from developed economies to the emerging world has fueled debate over the costs and benefits of globalization. While in the developed economies there is growing concern over the footloose nature of jobs, competitiveness, and future standards of living, in the emerging economies there is increasing uncertainty and insecurity about the sustainability of their economic growth model.

Globalization has been closely intertwined with, and has conflated the impact of technological change. Nobody disputes that technological advances have been a major driver of economic growth and increasing standards of living. But machines and computers have displaced many low-paying as well as high-paying jobs. Jobs requiring repetitive, machine-replicable activities and processes in manufacturing, or involving information classification, standardized analysis and retrieval in services sectors have been pummeled by automation. On the other hand, it is difficult to machine-replicate and machine-substitute activities involving manual and physical dexterity, subtle hand-eye coordination, simultaneous deployment of a range of senses, and nuanced judgment. Many people can accomplish these tasks with a fair degree of competence. But therein lies the rub. Since potentially many humans can excel at these occupations, such as food servers, janitors, drivers and gardeners, which require relatively little training and education, they compete against each other, leading to lower wages. At the same time, it is also difficult to automate jobs involving creativity, judgment born of human trial and error, and analysis born of years of education. These jobs continue to command high wages. Unless, of course, they are offshoreable.

Many tasks that are telecommutable and can be delivered from a distance have migrated to take advantage of lower wages, thus combining both technology and globalization. Competition for a job these days comes both from a machine, as well as a fellow job seeker, sometimes half way around the world. When Keynes wrote, back in 1920, that “The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep,” he could scarcely have imagined a similar scenario for services. The occupational spectrum is therefore pockmarked with vulnerable vocations. At one end of the wage range are personal services jobs, largely unthreatened either by machines or cheap, foreign labor. At the other end of the occupational gamut, and scattered throughout, are those jobs that have a personalized or localized delivery aspect, some of which, involving specialized skills, education, and local networking are high-paying.

The economies of most countries are becoming increasingly dominated by services. This poses some additional and unprecedented challenges to their national economic policies. Many services have slow productivity growth, and in the case of some the very concept underscores the futility of applying criteria from “economics” to human activity (e.g. in the arts and other creative fields). Does this mean that economies relying primarily on services, especially those of developed countries, will become relatively costlier, condemning them to even higher cost structures in future, as well as increasing inequality? Does this mean that manufacturing, and the production of tangible goods is somehow special, and explains the relatively happier economic fortunes of, say, Germany, which has retained a sizeable high-end manufacturing niche?

While it is true that some services do not require sophisticated manufactured goods for their production and delivery, many others, such as medical care, environmental services, transportation services, software and so forth do. Manufacturing and services are therefore inseparable; it is difficult to sustain competitiveness in manufacturing-dependent services without commensurate quality in complementary tangible goods production. Both are vital to human development and welfare, although it does seem that manufacturing can no longer play the same role it did in the past in generating mass employment. Over the past few centuries, the making of manufactured products has been a fulcrum of progress and a cornerstone of nation building. It has left a deep imprint on our collective psyches and social behavioral patterns. The historian, Paul Kennedy, who grew up in a shipbuilding community describes in a beautiful passage, “There was a deep satisfaction about making things. A deep satisfaction among all of those that had supplied the services, whether it was the local bankers with credit; whether it was the local design firms. When a ship was launched at [Newcastle firm] Swan Hunter all the kids at the local school went to see the thing our fathers had put together and when we looked down from the cross-wired fence, tried to find Uncle Mick, Uncle Jim or your dad, this notion of an integrated, productive community was quite astonishing.” But if economies are adjusting to this bias toward services, then societies can do so as well, and they will — by creating a different, evolving notion of an “integrated, productive community,” making “things” and creating jobs that give meaning, fulfillment and satisfaction.

Ashok Bardhan is a Senior Research Associate at the Fisher Center for Urban Economics, Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley. He is co-editor of The Oxford Handbook of Offshoring and Global Employment with Dwight M. Jaffee and Cynthia A. Kroll.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: refinery worker, engineer, pointing at large chemical gas pipes, pipelines. © lagereek via iStockphoto.

The post Footloose jobs, rootless machines appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSeven historical facts about financial disastersCome together in Adam SmithPaul Collier on immigration

Related StoriesSeven historical facts about financial disastersCome together in Adam SmithPaul Collier on immigration

November 8, 2013

Poverty and health in the United States

We live in the richest nation on earth. Yet 15% of the US population (about 46 million people) live below the poverty line — about $23,000 for a family of four. Almost 25% of children live in poverty. The number of American households living on $2 or less grew by 130% between 1996 and 2011. Actual household median income decreased by more than 8% between 2007 and 2012. And the number of homeless children in preschools and schools recently rose 10% within one year.

If you are poor, you are more likely to develop many illnesses, more likely to become injured, more likely to become disabled, and more likely to die early. You are less likely to have access to high-quality medical care — or any medical care at all — and less likely to have access to preventive services.

If you are poor, you are less likely to have adequate knowledge about threats to your health and to the health of family members, and less likely to know how to navigate our complex health care system. You are less likely to receive medical care from providers who are sensitive to your needs, who understand your living conditions, and who comprehend your personal and cultural perspectives on health and illness.

If you are poor, you are more likely to live in communities with hazardous outdoor and indoor air pollution. Your children are more likely to have elevated lead levels and resultant problems, such as lower IQ scores and reading levels, attention deficits, and behavioral problems. You are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed, and when able to get a job, you’re more likely to work in an unhealthful or unsafe workplace with hazardous chemical or physical exposures.

If you are poor, you are less likely to be able to access healthy foods and are more likely to be obese — and develop illnesses associated with obesity. You are more likely to be addicted to cigarettes. You are more likely to be victims of domestic or community violence. As a young adult, you are more likely to join the military in the hope of getting out of poverty — despite the risk of physical or mental disability, or death.

Not only does poverty adversely affect health, but also poor health increases the probability that a person will be poor. In the absence of adequate safety nets, people who are chronically ill or disabled from an injury are likely to become poor or even poorer. Medical expenses have been the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States, even among individuals who thought they had adequate health insurance.

Why are there so many poor people in the United States today? There are many reasons: the ongoing high unemployment rate, the shredding of the social safety net, the declining power of workers and labor unions, the rising influence of market forces on social values and allocation of resources, decreased spending on the infrastructure of society, and diversion of financial and human resources to military purposes and away from programs and services that support people.

Much needs to be done.

We, as a nation, need to assure conditions in which poor people can be healthy, by promoting equal access to affordable high-quality medical care and preventive services; by addressing the societal conditions that keep poor people poor, such as by assuring that jobs provide a living wage – rather than a wage that amounts to a poverty wage; by providing access to high quality education, appropriate job training, and employment opportunities; and by providing adequate housing.

We also need to address racism, sexism, ageism, and other forms of discrimination. We need to protect the rights of everyone in society, especially those who are most vulnerable. And we need to make sure that poor people have a say in the decisions that affect them and their families and communities.

We need to communicate data that describe poverty and put a human face on these data by giving voice to the stories of poor people. We need to engage the public in these issues.

We need to educate and train health professionals to be culturally competent to address the medical needs of poor people, and also socially and politically competent to address the social context that keeps poor people poor from one generation to the next.

As public health workers and other health professionals gather for professional conferences this fall, we have a chance to focus on addressing poverty and its health consequences and on how to effectively address these problems.

Barry S, Levy, M.D., M.P.H., and Victor W. Sidel, M.D., are co-editors of the following books published by Oxford University Press: the recently published second edition of Social Injustice and Public Health, and two editions each of War and Public Health and Terrorism and Public Health. They are both past presidents of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Levy is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Sidel is Distinguished University Professor of Social Medicine Emeritus at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein Medical College and an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College. Read their previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Poverty via iStock photo

The post Poverty and health in the United States appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe case against striking SyriaSocial injustice and public health in AmericaHealth care in need of repair

Related StoriesThe case against striking SyriaSocial injustice and public health in AmericaHealth care in need of repair

The usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr.

By Caitlin Tyler-Richards

In celebration of Veterans Day, we’re pleased to share a conversation between Oral History Review managing editor Troy Reeves and Dr. Robert P. Wettemann Jr., director of the US Air Force Academy Center for Oral History. A historian at heart, Wettemann shares his thoughts on the importance of preserving veterans’ stories, using oral history to get the insider’s perspective, and turning history into a “usable past.” He discusses the Center’s on-going project to document the Air Force Academy’s role in the 2012 & 2013 Colorado Springs, CO wildfires, and previous work done to collect experiences from September 11th. Enjoy!

Or listen to the podcast on the Oral History Review Soundcloud page.

Dr. Robert P. Wettemann Jr. received his PhD in History from Texas A & M. Upon graduation, he taught American history at McMurry University, and helped launch their Public History Program. In 2007, Wettemann went to the U.S. Air Force Academy as a visiting Associate Professor in History, and in 2009 they invited him back to revitalize their defunct oral history program. Wettemann now serves as director at the U.S. Air Force Academy Center for Oral History. He is also the author of Privilege vs. Equality: Civil Military Relations in the Jacksonian Era, 1815-1845 (Praeger Security International, 2009).

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Image courtesy of Dr. Robert P. Wettemann Jr.

The post The usable past: an interview with Robert P. Wettemann Jr. appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCSI: Oral HistoryConsidering your digital resumeQ&A with author Craig L. Symonds

Related StoriesCSI: Oral HistoryConsidering your digital resumeQ&A with author Craig L. Symonds

Health care in need of repair

Sometimes I think that Click and Clack — you know, the Car Talk™ experts — could give us a lesson on repair. They are pretty good at diagnosis; have plenty of experience in knowing how to test things out; are great listeners to the concerns of people who have a problem; and they really know subtyping — the characteristics specific to certain makes and models of different cars.

This is just the sort of expertise that is required for one aspect of the new health care policies which are being implemented across the United States. This particular initiative is called comparative effectiveness research. It is being funded to test things out (head-to-head comparisons), involves listening to concerns that are important to people (patient-centered outcomes), and evaluates which therapies work best in specific types of people (subtyping).

While mechanics and others working in various industries tend to do this as a normal part of everyday business, it is remarkable why we haven’t made a renewed effort to do this better in health care years ago. It only makes sense. Who wouldn’t want to know which treatments work better than others? Who wouldn’t want to know whether specific therapies make it easier (or more difficult) for you to function day-to-day when at work or at home? Who wouldn’t want to know whether a treatment tends to work particularly well in people who are just like me — of similar age, background, and medical history? Certainly, the patients involved and their families would like this information. Such information can provide the basis for better decision making. And, besides, it’s good business practice.

As a medical researcher, I work with others to design studies to test things out, take care to include outcomes important to patients, and am currently making a renewed effort to discover which therapies work better in particular types of patients. From the perspective of a person who is working in the trenches of research, there is too much rancor over the concept of comparative effectiveness research. Perhaps, as usual, there is the concern regarding where the money will be spent. Rigorous debate is to be anticipated whenever money is involved. But the concept — well, who could argue with that?

Here again we can take a lesson from Click and Clack. They do an incredible job in educating the public. Even people without an intrinsic love of the inner workings of a car find helpful tips and direction on how to handle car issues — all interspaced with humor. They deliver information to a wide swath of America so that even people like me — who have no real love of cars per se — learn something and love learning it. If we could only tap that type of energy to help people learn about other choices in their daily lives — those involving their health. There is some good evidence already available in the medical literature that is useful when making health choices. These are published medical studies in which head-to-head comparisons of treatments have been made in a fair, unbiased manner. But the findings from such comparative effectiveness research do not belong on the back shelf. Strong evidence from well-conducted studies deserves up-front attention. Why would you want to waste your money (and time and health) on a treatment that doesn’t work? Certainly we wouldn’t want to spend our hard earned money on paying for unnecessary car repairs when there really isn’t a problem or to purchase costly repairs when a cheaper, more effective fix is available. When the outcome is your health, the stakes are even higher. There may not only be wasted dollars but detrimental impacts on your ability to function every day.

As the squabbling in the United States continues regarding changes in our network of health systems, know that a part of these new policies involves testing to find out what works better. Those of us doing this fieldwork believe that good health can be enhanced through good information. It’s important to know whether I only need a serpentine belt change rather than a whole engine overhaul.

Mary A. M. Rogers, PhD is a Research Associate Professor and Clinical Epidemiologist in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan. She is the author of the upcoming Comparative Effectiveness Research.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Male Doctor Examining Male senior Patient With Hip Pain. © monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.

The post Health care in need of repair appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTale of two laboratoriesNew tricks with old music?Why read radiology history?

Related StoriesTale of two laboratoriesNew tricks with old music?Why read radiology history?

Common Core: lesson planning with the Oxford African American Studies Center

In 2012, 45 US states, as well as the District of Columbia, adopted and began implementing the new Common Core State Standards in K-12 public schools. In history and social studies classes, the Common Core Standards emphasize critical thinking and analytical reading and writing skills. Most of the Standards require students to use information from primary source documents to complete a variety of skills-based tasks.

The guide below provides history teachers with examples of how resources from the Oxford African American Studies Center (AASC) can be used to create lessons that align with these new standards. Founded by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., AASC has been the leading online reference site in the field of African American studies since 2006. With over 10,000 reference articles—supported by hundreds of primary source documents, maps, and other tools—the site provides the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available to researchers, educators, and students.

For more information regarding the specific reading and writing Standards for each grade level, please refer to the Common Core Standards website.

SAMPLE LESSON

Following is an example of how middle and high school history teachers could use resources from AASC to plan a lesson aligned with the Common Core Standards. This lesson about the Fugitive Slave Act is designed for a unit on Sectionalism or Abolitionism within a US History course.

Which Standards should I use?

When creating lessons and units within the new Common Core framework, the first step for most history teachers is to select the reading and writing Standards that correspond to the skills and content to be taught. Before deciding which Standards to embed within the lesson, however, the teacher might want to see which of AASC’s available resources are related to the lesson’s specific content.

The primary source documents on AASC’s website relating to the Fugitive Slave Act include text from the law itself, publications from abolitionists in response to the law, and arguments in support of the law. Because students will be asked to read each text and use evidence from the source to answer central questions about, and examine arguments pertaining to, the Fugitive Slave Act, some of the relevant standards include:

Reading Standard One for history/social studies [CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.1]: “Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole.”

Reading Standard Six for history/social studies [CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.6]: “Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.”

Theoretically, each lesson should contain at least one writing Standard in addition to one or more reading Standards if teachers require students to write in the classroom on a daily basis. Standards applicable to this lesson include the following for history/social studies:

Writing Standard One for history/social studies [CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.1a]: “Introduce precise, knowledgeable claim(s), establish the significance of the claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that logically sequences the claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence.”

Writing Standard Nine for history/social studies [CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.9]: “Draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.”

Which AASC resources should I use?

Next, the teacher must consider which texts — primary and secondary source documents, images, graphs, maps, etc. — correspond to the content and will allow students to practice and master the skill(s) outlined in the selected Standard(s). Because the Common Core Standards emphasize skill over specific content, teachers can select culturally-relevant resources that correspond to their students’ needs. AASC resources give teachers the ability to include a variety of perspectives in the classroom.

As discussed above, the Oxford African-American Studies Center has a number of resources related to the Fugitive Slave Act. In order to access these resources, navigate to the Oxford AASC homepage, click on “Browse,” then “Primary Sources.” Teachers can complete a keyword search for “Fugitive Slave Act,” or simply look through the available resources. The following primary and secondary sources will be used in this lesson:

Background on Fugitive Slaves

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

Caution!! Colored People of Boston (1851)

Great Excitement! Arrest of Fugitive Slave (1854)

Speech by Samuel Ringgold Ward, in Response to the Fugitive Slave Law (1850)

Speech by Daniel Webster in Defense of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 (1850)

Teachers may want to consider adapting these sources for younger or struggling readers, particularly in the lower grade levels. Refer to the lesson Personal Narratives as Advocacy Tools: Efforts to End the Transatlantic Slave Trade for examples of adapted primary source documents that include word banks for students.

What questions should I consider?

Most history lessons revolve around one or more key historical questions, often called ‘Essential Questions.’ In order to determine which questions to ask, the teacher should thoroughly review each text the student will be working with and look for patterns, contradictions, and major themes. Consider the following: Which questions will allow students to practice the skills described in the selected Reading and Writing Standards for History/Social Studies? Which questions will engage a student’s critical thinking, and require responses that can be supported with evidence from the documents? Which questions do not necessarily have “right” or “wrong” answers? After reviewing the resources above, students will investigate the following questions in this lesson:

How did the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increase support for the abolitionist movement?

How does Ward’s argument against the Act contradict Webster’s argument in support of it? What tools do both authors use to convince their respective audiences?

How did the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increase division between the North and the South?

Was the Fugitive Slave Act a good or bad law for America?

How could I structure my lesson?

There are many different ways a teacher could effectively structure a lesson in order to accomplish the goals and tasks described above, and this guide does not purport to lay out a scripted lesson structure. However, when introducing challenging texts it is important for the teacher to explicitly model strategies for reading critically and performing the assigned task. Below is a suggested outline for how a lesson could proceed, with clear opportunities to activate students’ prior knowledge on the topic and model the desired skill(s). The outline also gives students a chance to practice the task both with support and independently.

I. Activating Prior Knowledge

As a warm-up activity, ask students to create a word map for the word “fugitive,” listing examples of other associations they have with the word, or where they might have heard the word previously.

II. Building Additional Background

The television program American Experience recently aired a special entitled The Abolitionists on PBS that includes a thorough explanation of the Fugitive Slave Act. Students can access this video clip online.

III. Teacher Modeling

A. Introduce the first document, the Speech by Samuel Ringgold Ward in Response to the Fugitive Slave Law (1850), that the teacher will use to model the specific task or reading strategy. The teacher should display a copy for modeling, and preferably each student should have an individual copy to reference during the modeling process.

B. The teacher should read through the document aloud, explaining her/his thinking process while highlighting or noting key information that could be used to answer one of the Essential Questions, such as “How did the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increase support for the abolitionist movement?” The students can do what the teacher does using their own copy of the source. The class could then discuss the matter, with teacher support, and try to formulate a response to the question using evidence from the text.

IV. Guided Practice

Place students in pairs and introduce the next document, Speech by Daniel Webster in Defense of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 (1850). In pairs, students should read through the document and follow the same process modeled by the teacher. Review as a class and incorporate additional evidence from this source in the class discussion.

V. Independent Practice

Students will work independently to re-read and compare Daniel Webster’s and Samuel Ringgold Ward’s speeches. They will follow the same strategies modeled by the teacher and practiced with a partner in order to answer the following Essential Questions: How does Ward’s argument against the Act contradict Webster’s argument in support of it? What tools do both authors use to convince their respective audiences?

VI. Closing

As an exit ticket, final class discussion, or homework assignment, students should respond to the question, “How did the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increase division between the North and the South?”

Sarah Thomson is a former North Carolina public school teacher and a current Ph.D. student in Teaching and Teacher Education at the University of Michigan.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Common Core: lesson planning with the Oxford African American Studies Center appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe African CamusJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneSeven historical facts about financial disasters

Related StoriesThe African CamusJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneSeven historical facts about financial disasters

The Battle of Thermopylae and 300

By Paul Cartledge

In 2006 the Frank Miller-Zack Snyder bluescreen epic 300 was a box office smash. The Battle of Thermopylae – fought between a massive Persian invading army and a very much smaller Greek force led by King Leonidas and his 300 Spartans in a narrow pass at the height of summer 480 BC – had never been visualised quite like that before. So affecting was its portrayal, indeed, that it prompted the Iranian delegation to the United Nations to lodge a formal complaint at the way the Persians had been depicted, or rather denigrated as subhuman monsters — as if George ‘Dubya’ Bush had any interest in that very ancient history! But on one thing the Iranian delegation — and the filmmakers — were entirely correct, historically speaking. The Battle of Thermopylae was indeed a key part of a series of battles — otherwise known as the Graeco-Persian Wars — that were a genuine struggle for civilisation, a decisive culture clash on a world-historical scale.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The forthcoming sequel to 300 is now announced for March 2014. It is called imaginatively 300: Rise of an Empire and will reawaken all those old questions and anxieties about East-West culture clash and the history of western civilization as a consequence. I can’t wait. But there’s another element to the conflict that shouldn’t be allowed to pass in silence. The ancient Greeks were a very competitive, indeed antagonistic lot. No sooner had the Spartans and Athenians and their respective allies defeated the Persians jointly, fighting shoulder to shoulder by land and on the sea, than they embarked on a bitter cultural war against each other — for priority and supremacy of commemoration. Which of the big two Greek cities deserved the credit (or a larger share of the credit) for leading the Greeks to victory and so ensuring that Greece would be free from culturally alien Persian domination?

Sparta and Athens were very different Greek cities, as different almost as they could possibly have been while still remaining distinctively ‘Greek’. Sparta was the model military state, under constant military discipline, and averse to the disorderly free-for-all of democratic politics. Athens on the other hand was the western world’s first democracy or ‘People-Power’, run by ordinary self-governing Athenian citizens. Actually it was the combination of their very different qualities on the battlefield — Spartan soldierly discipline and training, Athenian brio and dash — that were crucial to the patriotic Greeks’ eventual major victories by sea (Salamis) and on land (Plataea). But neither would give way to the other in the commemoration stakes. The Spartans enlisted the famous Greek praise-singer Simonides in their cause, to celebrate the decisive land victory at Plataea in 479 BC, but Herodotus, the Western world’s first proper historian, gave the lion’s share of the credit to Athens for its contribution to the naval battle of Salamis in 480.

Paul Cartledge is AG Leventis Professor of Greek Culture at the University of Cambridge. His most recent book is After Thermopylae. The Oath of Plataea and the End of the Graeco-Persian Wars (OUP. 2013). He is also the author of Ancient Greece: A Very Short Introduction.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook. Subscribe to Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

The post The Battle of Thermopylae and 300 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImages to remember the Battle of PlataeaFDR, Barack Obama, and the president’s war powersMeasurement doesn’t equal objectivity

Related StoriesImages to remember the Battle of PlataeaFDR, Barack Obama, and the president’s war powersMeasurement doesn’t equal objectivity

November 7, 2013

The African Camus

Albert Camus, celebrated author of those high school World Literature course staples The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus, would have been 100 years old today. While Camus is normally classified among the giants of 20th-century continental literature, I would argue that he could equally legitimately be considered a Francophone African writer. He was, after all, born in Algeria, and lived there until he was nearly 27 years old. Camus’s first collections of essays were initially published in Algeria, and most of his late novels were set in North Africa.

Camus didn’t hesitate to affirm the influence of his African years on his life’s work. Writing in 1958 in the preface to a new edition of his first collection of Algeria-centric essays, L’envers et l’endroit (sometimes translated as The Wrong Side and the Right Side), Camus states, “I know that my inspiration is in The Wrong Side and the Right Side, in this world of poverty and light where I lived for so long and whose memory still keeps me away from the two opposing dangers that menace every artist: resentment and satisfaction. […] I was placed halfway between misery and the sun. Misery kept me from believing that all is well in this world and with history; the sun taught me that history isn’t everything.” (L’envers et l’endroit, 1958, pp. 13-14. Translation mine.)

Perhaps befitting his intercultural status as a pied-noir (that is, a person of European descent living in French North Africa), Camus wholeheartedly embraced this notion of the halfway. His decision, however, often meant that he had to blaze his own trail, and consequently expose himself to strident criticism. During the Algerian War, for instance, Camus famously refused to support the cause of Algerian independence and did not condemn outright the atrocities committed by French soldiers. Though Camus vocally opposed the violence of war in all of its forms, and wrote frequently about the suffering of native-born Algerians under French colonial rule, he could not bring himself to reject the pied-noir community that had raised him. Algerian resentment over the perceived offense lingers to this day.

Camus’s decision to withdraw from the debate surrounding Algerian independence was surely a blow to revolutionaries seeking a prominent, well-regarded champion, but I have to think that the resultant Algerian rejection of Camus must have stung the writer just as sharply. His soul was Algerian, and I’ve found some of his most lyrical, emotional writing in his early nonfiction essays on life in North Africa. I’ll close this brief post with my favorite passage from his essay “Summer in Algiers,” published as a part of Noces (Nuptials) in 1938. While it may be unabashedly (and uncharacteristically) sentimental, the text also has a certain mournful quality that I find to be perfectly evocative of the complex relationship Camus had with the land of his youth:

But more than anything else, there is the silence of summer evenings.

Does the Algiers in me need any special signs or sounds to embrace these short instants where the day tips into night? When I’ve been away from this land for a while, I imagine its twilight as a promise of happiness. On the little hills that dominate the city, roads wind through the mastics and the olive trees, and it’s to them that my heart returns. I see gatherings of black birds rise above the green horizon. In the sky, suddenly emptied of its sun, something unwinds: masses of red clouds spread out until they are reabsorbed into the air. Just a moment later, you see the first star begin to form and harden in the thickness of the sky. And then, all of a sudden, the night, all-consuming.

These fleeting evenings in Algiers, what unique power do they have to unravel so much within me? This sweetness that the evenings leave on my lips, I don’t have time to tire of it before it has already disappeared into the nighttime. Is this the secret of its persistence? The tenderness of this country is devastating and stealthy, but in the instant that you find it, your heart, at least, is entirely devoted.

(Noces, 1959, pp. 39-40. Translation mine.)

Tim Allen is an Assistant Editor for the Oxford African American Studies Center. You can follow him on Twitter @timDallen.

The Oxford African American Studies Center combines the authority of carefully edited reference works with sophisticated technology to create the most comprehensive collection of scholarship available online to focus on the lives and events which have shaped African American and African history and culture.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Albert Camus in 1957 by Robert Edwards. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The African Camus appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneA Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship OnlineShakespeare in disguise

Related StoriesJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneA Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship OnlineShakespeare in disguise

New tricks with old music?

As a musician myself I have certainly received my fair share of warranted (and un-warranted) criticism over the years. There is nowhere to hide on the concert platform. Performing music necessarily requires being open to others, exposing more of the self than is demanded in most other walks of life. It is perhaps only natural, therefore, that the controversial subject of authenticity should remain so stubbornly relevant to our understanding and pleasure of (musical) performance. “Keepin’ it real” is as germane to the historically informed performance (HIP) of “old” music as it is to Hip Hop, after all.

In Richard Peterson’s (1997) research on the creation of American “country music” he draws attention to the “authenticity work” that performers and their managers construct to give the impression that they are what they say they are. Such “fabrication” deploys authenticity as a discursive device, wielded as the magician wields their wand, to achieve particular ends in a particular context, i.e. the market. This is the form of authenticity that lies behind so many branding campaigns for coffee, jeans and so on, and which vie for attention by emphasizing the “original”, “real” or “authentic” nature of their products. But is this all there is to it? Are authenticity’s critics right to assert the ontological in-authenticity of all that is man-made? A study of the British early music movement (Early Music) would suggest not.

At the heart of Early Music’s ideological commitment to authenticity has been the intention to perform music of earlier times in such a way as to recreate the sounds of the original performances, rather than according to the standard “traditional” practices generally cultivated much later on, largely in the 19th century. For its detractors, here was a misguided project, founded on an intellectually flawed ideology: ‘how could we possibly know what an orchestra sounded like in the early 18th century, or what a composer intended their music to sound like?’ they cried. Labeled “modernists”, by some, and “rule-bound” by others, early musicians and their ensembles (including the Academy of Ancient Music; The English Concert; The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; The Tallis Scholars) have continued to attract huge audiences the world over. As early musicians know only too well, accumulated knowledge of how the music should be performed is central to an authentic performance, but only if it does not prevent the performance of the musical work from enchanting both performer(s) and audience.

So instead of understanding authenticity in terms of an idealized and dogmatic goal that dictates how musicians strategically manage their craft, Early Music encourages us to re-conceptualize it as the human capacity (and for some a developed capability) to reconcile the apparently irreconcilable on an on-going everyday basis. Understood this way, authentic performance is not about the winning out of old over new, head over heart, text over act, or scholarship over performance, but rather the way in which these seemingly contradictory interests and approaches come together in and through the lived process of doing art. Furthermore, authenticity is not just about the ‘unimpeded operation of one’s true- or core-self in one’s daily enterprise’ (Kernis & Goldman 2006), since the very inevitability of being impeded is, if you like, the starting point for living and behaving with authenticity. Quite simply, authenticity is not found in the longed-for ideal, but in the everyday ebb and flow of life.

So instead of understanding authenticity in terms of an idealized and dogmatic goal that dictates how musicians strategically manage their craft, Early Music encourages us to re-conceptualize it as the human capacity (and for some a developed capability) to reconcile the apparently irreconcilable on an on-going everyday basis. Understood this way, authentic performance is not about the winning out of old over new, head over heart, text over act, or scholarship over performance, but rather the way in which these seemingly contradictory interests and approaches come together in and through the lived process of doing art. Furthermore, authenticity is not just about the ‘unimpeded operation of one’s true- or core-self in one’s daily enterprise’ (Kernis & Goldman 2006), since the very inevitability of being impeded is, if you like, the starting point for living and behaving with authenticity. Quite simply, authenticity is not found in the longed-for ideal, but in the everyday ebb and flow of life.

As Daniel Barenboim writes ‘What is, ultimately, perhaps the most difficult lesson for the human being — learning to live with discipline yet with passion, with freedom yet with order — is evident in any single phrase of music.’ ‘Real’ authenticity refers to our over-arching capacity to manage the tensions that inevitably arise on a daily basis; as in performance, so in life. Making early music work in the modern age has required putting this ‘difficult lesson’ into practice, and we have much to learn from looking more closely at just how those involved in Early Music have gone about it.

Dr Nick Wilson is Senior Lecturer in Cultural & Creative Industries at CMCI, King’s College London, and a professional early music performer. He is the author of The Art of Re-enchantment. Making Early Music in the Modern Age.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Photo taken by Nick Wilson (author) (2) Orchestra conductor by Woo Bing Siew via Dreamstime.com (royalty free)

The post New tricks with old music? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy does this baby cry when her mother sings?Why read radiology history?Amazing!

Related StoriesWhy does this baby cry when her mother sings?Why read radiology history?Amazing!

Why read radiology history?

Does history matter? Professional historians will not hesitate to answer in the affirmative for a multitude of reasons. I am sure many professionals in technical and scientific fields, however, may have asked themselves the first question in a reflective moment without necessarily the same positive responses attributed to professional historians.

But in an era where professional success in these scientific fields depends on obtaining research grants and publishing papers in high impact journals, there may be little time left to attribute to the study of the past. However, it is imperative that people are aware of their past, as without it, an understanding of the present is incomplete. Knowledge of the past will help to guide decisions about the future just as much in scientific endeavours as in human politics, administration, and other walks of life.

Why read about radiology history specifically? Knowledge of medical history helps us to understand how we have arrived at the state of knowledge of current medical practice. Knowing what has not worked in the past enables us not to repeat mistakes. Knowledge of previous literature prevents society from repeating fruitless areas of scientific enquiry or enables those with vision to approach problems from a new angle.

This is only possible with hindsight gleaned from previous literature on the subject and a thorough knowledge of history is required for this. I am always reminded of the words of Michael Crichton, the author of Jurassic Park, who said “If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that does not know it is part of a tree.”

Radiology is a relatively new branch of medicine with a history of a little more than a century. Roentgen’s discovery of x-rays in Wurzburg on November 8, 1895 revolutionised medicine in a way that could not have been foreseen. Today his discovery is celebrated during the annual international day of radiology, held on the 8th of November each year.

In the years since Roentgen’s seminal experiment, however, the science of imaging the human body has developed at an alarming pace due to advances in physics, chemistry, engineering, and more recently, computing, all of which was achieved by a cross fertilisation of ideas between people from many varied backgrounds. Today radiology plays a central role in modern medical practice. Knowledge of its history will hopefully make us more aware of how much we are all indebted to the pioneer doctors and scientists of yesteryear, the selfless radiation martyrs who paid the ultimate price so that today we have a panoply of equipment and skills in the diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium against disease.

Arpan K Banerjee qualified in medicine from St Thomas’s Hospital Medical School in London, UK and trained in Radiology at Westminster Hospital and Guys and St Thomas’s Hospital. In 2012 he was appointed Chairman of the British Society for the History of Radiology of which he is a founder member and council member. In 2011 he was appointed to the scientific programme committee of the Royal College Of Radiologists, London. He is the author/co-author of 6 books including the recent The History of Radiology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: X-ray hand, via iStockphoto.

The post Why read radiology history? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTale of two laboratoriesWhat has psychology got to do with the Internet?Will the real Alfred Russel Wallace please stand up?

Related StoriesTale of two laboratoriesWhat has psychology got to do with the Internet?Will the real Alfred Russel Wallace please stand up?

November 6, 2013

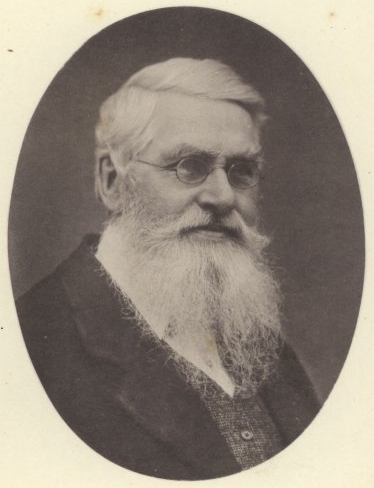

Will the real Alfred Russel Wallace please stand up?

The year 2013 is the centenary of the death of the Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, best-known as the man who formulated the theory of evolution by natural selection independently of Charles Darwin. To mark this anniversary there has been many conferences, exhibitions and publications. There has also been a considerable amount of media coverage including the BBC2 series Bill Bailey’s Jungle Hero, an episode of BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time, two episodes of The Infinite Monkey Cage, and many other reports.

It’s reminiscent of the commemorations for his famous contemporary Charles Darwin in 2009. But the Wallace year is on a vastly smaller scale. And it is this gulf between the fame of Darwin and Wallace that inspires many of Wallace’s remarkably passionate admirers. There is some connection between the belief that Wallace’s relative obscurity is an injustice that fuels the passion and often anger of his supporters. And, of course, stories of a forgotten genius appeal to the media. This is why no article or media report on Wallace just tells us who he was and what he did. No, instead a large percentage of each report on Wallace complains of how much more famous Darwin is — with the implication that Wallace really ought to be equally famous.

Over the past few decades, the story of Wallace has gradually departed further and further away from the way it was told by Wallace and his contemporaries. He has become a victim figure. This ill-treated working-class hero was cheated of his priority and fame by the privileged establishment figures surrounding the patrician Darwin. In the most extreme versions it is even claimed that historical evidence supporting these conspiracy theories was destroyed or that Darwin stole ideas from or even plagiarized Wallace. Thus gradually, and unwittingly, a new Wallace has appeared who is very, very different from the historical Wallace. We have instead a mythical Wallace who was the greatest field biologist of the 19th century, the true father of the theory of evolution, and by the end of his life, supposedly the most famous scientist in the world. And it has all been taken from him.

The vast gap between the popular view of Wallace and the Wallace revealed by the historical evidence allowed me to radically re-write the story in another book Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin. I knew that the surprising revelations in the book would not always please Wallace fans, but I have been surprised at the reactions — and accusations — in some online comments and blogs. One blog comment accused my book of having “a strong anti-Wallace agenda”. It is ironic coming from Wallace fans whose stated mission is to promote their hero. That, after all, is an agenda. It is not a search for historical accuracy or understanding.

As a historian of science, my “agenda” has long been to correct historiographical myths and legends – where accounts of Victorian science have strayed far from what really happened. I also try to add new information to an otherwise old and sometimes rather hackneyed story as Wallace’s has become.

The real Wallace can only be revealed by rigorous historical research. Unfortunately Wallace’s admirers are not historians. But this doesn’t stop them from thinking they know better.

Take the recent insistence that Wallace complained that his evolutionary Ternate essay, sent privately to Darwin in 1858, was printed without his consent and indeed against his wishes. In the face of the many instances of Wallace describing how delighted and honoured he was to have his paper published together with Darwin’s — we now hear this line from an 1869 letter from Wallace to the German naturalist A.B. Meyer: “It was printed without my knowledge, and of course without any correction of proofs. I should, of course, like this act to be stated.”

This is quoted by Wallace fans as if it were a smoking gun. “You see!” they exclaim, “he complained about his essay being printed without his consent!” They interpret the phrase “printed without my knowledge” as if it were written in the present. Of course in modern English it means ‘printed without my consent’. But in the 19th century the phrase actually meant that a piece of writing was considered so worthy that it was printed even without the author having to put it forward himself. It was an expression of modesty, not of resentment. Wallace also wanted to point out that the essay may not have been quite as polished as his other writings.

Meyer was writing an account of Wallace’s life for German speaking readers. As to the remark above Meyer added “This I did in my pamphlet of 1870”. No one has ever bothered to check what Meyer then said in his book, probably because it is in German. Meyer wrote: “Mr Wallace wishes to take this opportunity to record that this essay was printed without his knowledge and that therefore (in the English original) some mistakes remained uncorrected.” Even more ironically, the 1895 piece in Nature where Meyer cited this Wallace letter was also sent for publication without Wallace’s knowledge!

Those who have already made up their minds about what happened in the past, and applaud anything that compliments Wallace and dismiss as anti-Wallace heresy anything that does not promote a heroic picture are beyond the reach of argument and evidence. But the majority of readers can still enjoy the excitement of discovery and the surprises of new research. The real, historical Wallace, warts and all, is still out there. And it is only through contemporary sources and historically informed and contextually sensitive investigation that we can find him.

John van Wyhe is a historian of science who specializes on Darwin and Wallace and Senior Lecturer at the National University of Singapore, and the Director of Darwin Online and Wallace Online. He has, with Kees Rookmaaker, edited Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters from the Malay Archipelago, with contains a foreword by Sir David Attenborough.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Alfred Russel Wallace, 1889. Photograph courtesy of the Wallace Online collection.

The post Will the real Alfred Russel Wallace please stand up? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTen facts about Charles Darwin’s ten childrenOn (re-)discovering Alfred Russel WallaceIn the footsteps of Alfred Russel Wallace with Bill Bailey

Related StoriesTen facts about Charles Darwin’s ten childrenOn (re-)discovering Alfred Russel WallaceIn the footsteps of Alfred Russel Wallace with Bill Bailey

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers