Oxford University Press's Blog, page 887

October 31, 2013

A spooky Halloween playlist

No other holiday has mood swings quite like Halloween. Running the gamut from horror to kitsch to comedy, the holiday is as variable as the types of costumes donned by schoolchildren on the day itself. This Halloween, we have put together a collection of songs collected from the staff at Oxford University Press that reflects that intrinsic variability. If there is one thread to follow through these 11 songs, it is films that we associate with Halloween, where horror and humor can live side by side (and occasionally collide). From a trio of hilarious, old-fashioned witches to a ballet-dancing coven of scary ones, from the Antichrist to a very famous cartoon dog, we’ve provided you with not only a Halloween playlist, but a list of movies to watch while tossing back candy corn.

The Ramones’ “You Should Never Have Opened That Door”

“Pretty self-explanatory. The Ramones and Halloween go together like a teenage road trip and a Native American burial ground.”

–Owen Keiter, Associate Publicist

Click here to view the embedded video.

Nine Inch Nails’ “Came Back Haunted”

“All Nine Inch Nails songs sound foreboding but this one is new and even has ‘haunted’ in the title. This is Trent Reznor’s first NIN single since winning an Oscar for The Social Network score.”

– Jeremy Wang-Iverson, Senior Publicist

Click here to view the embedded video.

Oingo Boingo’s “Dead Man’s Party”

“Not only is this a song about a zombie party, but the lead singer of Oingo Boingo is Danny Elfman, who writes the soundtracks for Tim Burton’s films – most famously The Nightmare Before Christmas, where Danny Elfman also plays the singing voice for Jack Skellington. It doesn’t get much more Halloween-related than that!”

– Lauren Hill, Publicity Assistant

Click here to view the embedded video.

Vince Guaraldi’s “The Great Pumpkin Waltz”

“Halloween always brings Vince Guaraldi’s ‘The Great Pumpkin Waltz’ to mind for me, underscore to ‘It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown’ (1966). It’s tremendous fun to return to as an adult. You can almost hear the leaves falling (and see Snoopy flying along as a World War I Flying Ace!).”

– Norm Hirschy, Editor, Academic Editorial

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sun Ra’s “Demon’s Lullaby”

“Sun Ra used his solar sonic exploration to travel to worlds above and below. ‘Demon’s Lullaby’ provides the eerie atmospherics perfect for any late night Halloween haunt.”

– Stuart Roberts, Editorial Assistant

Click here to view the embedded video.

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell On You”

“This song is a central figure in major plot point in one of the greatest Halloween movies ever made, Hocus Pocus. I chose the original version instead of the Bette Midler version, however, because of the ridiculous noises that Jay Hawkins makes at the end which reminds me of a tape of horrifying screams and torture noises my parents had and would play from a hidden boombox in our yard on Halloween to scare small children.”

– Erin McAuliffe, Marketing Coordinator, Digital

Click here to view the embedded video.

Bette Midler’s “I Put a Spell On You”

“I love ‘I Put a Spell on You’ because without fail, it always makes me think of Hocus Pocus when Bette Midler gets up to sing it and casts a spell on the crowd. I still absolutely adore that movie, even though it’s not scary and it’s totally for kids. Really enchanting.”

– Melanie Mitzman, Assistant Marketing Manager, Academic/Trade

Click here to view the embedded video.

Jerry Goldsmith’s The Omen Soundtrack

“With lyrics in Latin and a full orchestra, this creeps me out and sends chills down my spine every time I hear it or watch the movie. I have goose pimples now just thinking about this music.”

– Christian Purdy, Publicity Director

Click here to view the embedded video.

Michael Jackson’s “Thriller”

“The quintessential Halloween song with a ‘horror movie’ video to back it up. ‘Thriller’ gets the crowd going no matter what the occasion and never fails to have everyone doing their best MJ inspired zombie impressions, poses and dance moves!”

– Ayana Young, Online Marketing Temp

Click here to view the embedded video.

Ray Parker Jr.’s “Ghostbusters Theme”

“Everyone has shouted, ‘GHOSTBUSTERS’ too emphatically at some point in time. The movie was great, and the song is just as good. You can’t hear this song and not bob your head.”

– Kate Pais, Marketing Assistant, Academic/Trade

Click here to view the embedded video.

Goblin’s “Suspiria Theme”

“This song sounds like a very sinister music box, made creepier with a discorded lute accompaniment and menacing vocals. The immersive, atmospheric score contributes perfectly to the film’s setting: a German ballet school secretly run by an ancient coven of witches.”

– Megan McPherson, Administrative Assistant, Sales

Click here to view the embedded video.

Your Oxford Halloween Playlist:

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A spooky Halloween playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSongs of summer, OUP styleHalloween with the Ghost ClubHalloween witches: ladies not for burning

Related StoriesSongs of summer, OUP styleHalloween with the Ghost ClubHalloween witches: ladies not for burning

Halloween with the Ghost Club

As Lisa Morton notes in her excellent Trick or Treat? A History of Halloween (2013), our annual festival of spooks is a typical result of messy history and cultural confusion. It entered modern English culture as a misunderstanding of the three-day Celtic new year celebration in Ireland, which started at sunset on the 31st of October, to mark summer’s end. British colonizers thought it a worship of blood-thirsty pagan gods. It was managed by fusing it with a network of Christian saints’ days. All Hallows Eve, the night before one of the holiest days in the Christian calendar, is meant to be the time when the barrier between this world and the next is at its thinnest and communications between the most likely. The sequence ends on 2nd of November, All Souls’ Day, the Commemoration of the Faithful Departed. This also happens to be the Mexican Day of the Dead.

Since the 1970s, Halloween has been coloured by American urban myths and the iconography of the modern Gothic. Children are menaced by demented psychos spiking drinks or putting razor blades in the candy. In terms of profit ratios, John Carpenter’s film Halloween (1978) remains one of the most successful films of all time, launching the career of the seemingly unkillable serial slasher Michael Myers, a permanent threat to transgressive teens everywhere. It became obligatory in my suburban childhood in the 70s to have local newspaper reports in early November about traces of witch sabbats found in the nearby woods, our very own Essex version of the Blair Witch Project. In the era of Black Sabbath and The Omen these urban myths were surely repeated everywhere.

The current commercialisation of Halloween — swathes of pumpkin-orange stuff for kids in the supermarket — feels like another stage of domestication. Western cultures are supposed to be increasingly secular, yet beliefs in a world of spirit remain consistently high. The sociologists who spoke of the ‘disenchantment of the world’ never quite understood the kinds of magical thinking that mark out the everyday human grasp of the world. Festival days are temporary moments that allow for these rituals of re-enchantment.

This seems very different from the Victorian fascination with ghost stories — something we tend to associate more with Christmas story-telling than their somewhat cutesy rendition of the Halloween festival. In my research for The Mummy’s Curse, I delved into the history of The Ghost Club, a group of Victorian gentlemen who met to tell each other, in perfect confidence, ‘real’ ghost stories and discuss them as evidential proof of life after death. A Ghost Club had been established in Cambridge in 1855 amongst Trinity scholars, but the London grouping was established on 1 November 1882 by the occultist Alfred Alaric Watts and the respected Spiritualist medium Reverend Stainton Moses, a man who spent decades receiving ‘automatic writing’ from the dearly departed. The Club met for fifty-four years, and although the dates shifted around, it was in the rules that they had to meet on All Souls’ Day, the first day of November.

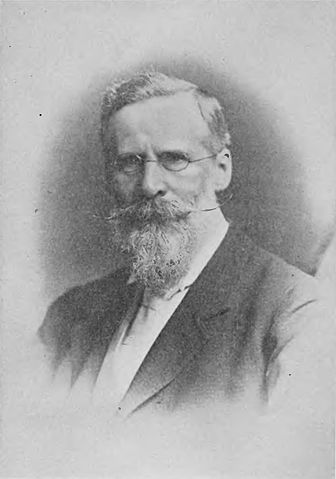

The Ghost Club was a typical earnest enterprise of concerned and educated men. (They eventually had a Ladies’ Night, but only forty years after starting out.) The ghosts of which they spoke were ephemeral, fugitive things, and the recounting of them was top secret. Nevertheless, the Club bureaucracy took minutes of every single meeting, leaving behind 16 volumes of closely hand-written notes that now reside in the British Museum. Their golden years were dominated by Sir William Crookes, the eminent Victorian chemist who also happened to be a Spiritualist and used his laboratory to measure the ‘psychic force’ of Spiritualist mediums. He insisted on privacy to protect his public reputation. Their members included lawyers, doctors, vice-admirals, prominent colonial officials, and aristocrats: it was a very exclusive club of ‘Brother Ghosts’. Their famous guests included Arthur Conan Doyle, Ernest Wallis Budge (the famous Keeper of the Egyptian Rooms in the British Museum), and painters like Sir William Richmond. They circulated ghost stories, experiences at séances, and rumours that even Queen Victoria had seen a ghost but that the story had been covered up by the Royal household. The tone of the minutes remains steadfastly serious and never remotely jaunty, very unlike the supernatural ‘club tales’ being written at the same time by Robert Louis Stevenson or Henry James.

The Ghost Club was a typical earnest enterprise of concerned and educated men. (They eventually had a Ladies’ Night, but only forty years after starting out.) The ghosts of which they spoke were ephemeral, fugitive things, and the recounting of them was top secret. Nevertheless, the Club bureaucracy took minutes of every single meeting, leaving behind 16 volumes of closely hand-written notes that now reside in the British Museum. Their golden years were dominated by Sir William Crookes, the eminent Victorian chemist who also happened to be a Spiritualist and used his laboratory to measure the ‘psychic force’ of Spiritualist mediums. He insisted on privacy to protect his public reputation. Their members included lawyers, doctors, vice-admirals, prominent colonial officials, and aristocrats: it was a very exclusive club of ‘Brother Ghosts’. Their famous guests included Arthur Conan Doyle, Ernest Wallis Budge (the famous Keeper of the Egyptian Rooms in the British Museum), and painters like Sir William Richmond. They circulated ghost stories, experiences at séances, and rumours that even Queen Victoria had seen a ghost but that the story had been covered up by the Royal household. The tone of the minutes remains steadfastly serious and never remotely jaunty, very unlike the supernatural ‘club tales’ being written at the same time by Robert Louis Stevenson or Henry James.

The most intriguing member for me remains Thomas Douglas Murray, the society gentleman who was known to have been cursed by a mummy when he purchased a coffin lid of a malignant priestess of Amen-Ra in his youth. He had purchased the lid in Luxor, then promptly shot his own arm off in a hunting accident. The mummy case in London scared the bejeesus out of Madame Blavatsky, the Theosophist, who begged it be given away. Once installed in the British Museum as catalogue number 22542 it allegedly began a career of malicious revenge on spectators who gawped too hard. Murray told his story to the Ghost Club several times in the 1890s.

When Murray died, his place in the Ghost Club was taken by none other than William Butler Yeats. I often think that Yeats’ poem ‘All Souls’ Night’, in which he calls up the ghosts of dead friends one by one, is a secret homage to the Ghost Club and to Douglas Murray. It ends, after all, ‘Wound in mind’s wandering/As mummies in the mummy-cloth are wound.’

Happy Halloween.

Roger Luckhurst is author of The Mummy’s Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy (2012) and the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics editions of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Dracula, and the Classic Horror Stories of H. P. Lovecraft.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: William Crookes. The Popular science monthly, Volume 84, p100. New York, Popular Science Pub. Co., January 1914. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Halloween with the Ghost Club appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGhosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!Halloween witches: ladies not for burningA Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship Online

Related StoriesGhosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!Halloween witches: ladies not for burningA Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship Online

Engineering has an image problem that needs fixing

Engineering is at the very heart of our society. Unfortunately many people don’t see it that way because engineering has an image problem. But why does that matter?

One reason is the projected serious shortfall in qualified engineers. Another reason is that science, technology, and engineering are often conflated in the media, therefore confusing career pathways.

First, let’s check the idea that engineering is at the heart of our society. Engineering is, in its most general sense, turning an idea into a reality – creating and using tools to accomplish a task or fulfil a purpose. Man’s ability to make tools is remarkable. But it is his ingenious ability to make sense of the world and use his tools to make even more sense and even more ingenious tools, that makes him exceptional. To paraphrase Winston Churchill ‘we shape our tools and thereafter they shape us’.

One only has to think of the railways, the telephone or the computer to realise that technical change profoundly affects social change. Engineering is a value laden social activity – our tools have evolved with us and are totally embedded in their historical, social and cultural context. Our way of life, the objects we use, the understanding and knowledge we gain, go hand-in-hand. For example the railways changed the places people chose to live and to take seaside holidays. Different kinds of fresh food, newspapers and mail were distributed quicker than ever before.

Like most of us, engineers will grumble about work, but in my experience, most of my fellow engineers find the innovative problem solving challenges of their work stimulating and engaging. The engineer entrepreneur James Dyson agrees; his foundation works to inspire and support future Edisons and Brunels.

Like most of us, engineers will grumble about work, but in my experience, most of my fellow engineers find the innovative problem solving challenges of their work stimulating and engaging. The engineer entrepreneur James Dyson agrees; his foundation works to inspire and support future Edisons and Brunels.

If engineering is important and interesting then why does it have such a poor image?

Of course there are no simple answers. But there are three that, I think, are important. First, collectively we engineers are not as good as we need to be at explaining to others what we do. Second; science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) are intertwined in a way that needs disentangling. Third, the media talk mainly of science and technology. If engineering makes the headline news then it rarely gets reported as engineering but rather as science or technology. Perversely quite a lot of reported science is actually engineering (e.g. genetic engineering).

The dictionary definitions are clear enough. Science is a branch of knowledge which is systematic, testable and objective. Technology is the application of science for practical purposes. Engineering is the art and science of making things such as engines, bridges, aeroplanes etc. Mathematics is the logical systematic study of relationships between numbers, shapes and processes expressed symbolically. So I think we have to conclude that the cloud around the use of these terms derives from the history of their development.

Philosophers of science have largely dismissed engineering and technology as ‘merely’ applied science. An exception is Carl Mitcham who examined technology from four perspectives – as objects, knowledge, activity, and interestingly as an expression of human will. Clearly technical objects are artefacts. Technical knowledge is specialised and it works. Technological activity includes crafting, inventing, designing etc. Technology as expressing human will is less obvious perhaps – but, in my opinion, here lies the key to disentangling STEM – human will defines purpose. When methods seem indistinguishable, individual purposes are usually quite distinct.

Different things motivate different people. The purpose of science is to know by producing ‘objects’ of theory or ‘knowledge’. The purpose of mathematics is clear, unambiguous and precise reasoning. The purpose of engineering and of technology is to produce ‘objects’ that are useful physical tools with other qualities such as being safe, affordable and sustainable. Science is motivated by curiosity whereas engineering and technology is motivated by wanting to make something to improve the human condition. Of course the two are not independent but the differences are important when considering a career.

Technicians and technologists are important and valued members of any project team but in the UK and in many parts of the world their scope of work is less than that of chartered engineers. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduates engineers not technologists. The equivalent body to the Royal Society for science is the Royal Academy of Engineering. There is a mismatch between how people outside science, engineering and technology talk and report STEM and how people within engineering and technology become qualified and the responsibilities they undertake.

The media influence how we think and what we value and so they influence career choices. There do not appear to be media outlets with an engineering correspondent. Technology correspondents report on digital systems. Engineering is reported variously by industry, science, environment, and transport correspondents so engineering issues are either squeezed out or reported from an inappropriate perspective. Does the BBC see engineering at the heart of society? Since 1942 influential and interesting guests have been choosing Desert Island Discs. Of the 2950 guests most (1232) have understandably been stage, screen and radio personalities. Just 82 were scientists with 28 medics and 11 engineers. But 6 of the 11 were architects and not professionally qualified as engineers. So in over 60 years the BBC thinks that just 5 engineers are interesting enough to be on the programme – hardly an endorsement of the pivotal importance of engineering.

If we want to recruit more young people into engineering we need to fix its image. How? C’mon you engineers – we need to tell our stories and we need to campaign for some changes by those who run our TV, radio and newspapers.

Professor David Blockley is an engineer and an academic scientist. He has been Head of the Department of Civil Engineering and Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Bristol. He is a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Institution of Structural Engineers, and the Royal Society of Arts. He has written four books including Engineering: A Very Short Introduction and Bridges: The science and art of the world’s most inspiring structures.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only technology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: By Michiel Hendryckx (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Engineering has an image problem that needs fixing appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhen are bridges public art?The many strengths of battered womenAstrobiology: pouring cold asteroid water on Aristotle

Related StoriesWhen are bridges public art?The many strengths of battered womenAstrobiology: pouring cold asteroid water on Aristotle

October 30, 2013

Etymological gleanings for October 2013

Touch and go.

I asked our correspondents whether anyone could confirm or disprove the nautical origin of the idiom touch and go. This is the answer I received from Mr. Jonathan H. Saunders: “As a Merchant Mariner I have used and heard this term for over thirty years. We use this term… to describe a quick port call, whether to take or discharge cargo or personal provisions, fuel, etc.” This comment sounds very much like the much earlier one I quoted in my post. However, we still do not know whether the idiom was coined by sailors or appropriated by them.

Capsize again.

Our correspondent (he will remain anonymous because he has given only his first name) wonders whether, considering the popularity of Dutch nautical terms, capuzar could have come to Spain by way of Dutch, which has kapseizen. Is it Dutch into English or English into Dutch? Nothing is known about the history of this verb, which suddenly became popular in the eighteenth century, but Dutch etymologists are certain that its source is English, though in English it may be of Romance origin.

Italian aregna and Engl. ring (in boxing, etc.).

Is this meaning of the English word of Italian origin? I don’t think so. In Italian, gn signifies palatalized n, so that the real comparison is between Latin arena (from harena) and Engl. ring (from hrengaz). But the question was about Dante’s phrase entrare nell’ aringo rimaso, which (I am quoting the letter of our correspondent) “can be translated as ‘re-enter the ring.’ I am guessing that aringo rimaso is from Latin harena remensa, i.e. newly laid out sand. That suggests to me that the ring in boxing ring, circus ring, etc. has its origins in Italian and not the Germanic hringr.” This derivation seems unlikely for two reasons. First, the earliest citation in the OED of ring with reference to boxing does not antedate the beginning of the nineteenth century. Second, despite Dante’s spelling aringo, this word could never be pronounced with the g-sound, while the Germanic word always had g in ring. Also, it is hard to imagine why such a word should have been borrowed by English boxers from Italian. The coincidence is curious, but this is as far as it goes.

Scots bra, Engl. brave, and Latin pravus “ferocious.”

Scots bra is certainly related to Engl. brave. It is even believed to represent a local pronunciation of brave. The closest analog would then be Swedish bra “good.” The Romance etymon was bravus. The rest is less clear. All the authoritative dictionaries trace bravus to Latin barbarus (“foreign, barbarous,” hence “wild,” with more or less predictable shifts of meaning). Pravus “ferocious” has been mentioned more than once in discussion of brave. However, no one could explain away the change from b to p, so that the comparison has been abandoned. The existing etymology is far from perfect (it presupposes the reduction from barbarus to brabrus, brabus, and finally to bravus) but may be more realistic than the shorter leap from pravus to bravus.

Unicorn.

Why is not unihorn? Because its etymon is Latin unicornis. The Latin for horn is cornu (as in cornucopia), with cornu being not only a gloss for but a cognate of horn.

Dragon.

Why dragon, if the Latin form is draco? Old English borrowed the Latin word with the predictable consonant in the middle, and drake (not related to drake “the male of the duck”) had a long history in English. Dutch draak and German Drache are easily recognizable cognates. In several Romance languages, k in this word became g, and Middle English took over this later form from Old French. Dragon supplanted drake, so that a rift appeared between it and the Latin (and Greek) etymon, but, by way of compensation, it aligned itself with its Romance siblings. Those interested in further ramifications are welcome to trace the history of Engl. dragoon. (I have also been asked about the origin of centaur. The word is from Latin, but its distant origin remains a matter of dispute.)

Ludic in English.

This word, borrowed from Modern French and meaning “of undirected or spontaneous playful activity,” was, according to the OED, coined by or at least had its earlier currency among psychologists, and in English it does not predate the late thirties. Unlike rare ludicrous, it is still rare (the root is the same; Latin ludus means “play, game, joke”). Specialists in the humanities know the term thanks to Homo Ludens, Johan Huizinga’s much-read and often-quoted 1938 book on the play element of culture.

Culottes, sans culottes, and related matters.

See the comment by J. Peter Maher on the first October post in this blog. You will learn that being “sans culottes” did not mean being without trousers. The picture accompanying the present post will dispel all doubts on this score.

Painting of a typical sans-culotte by Louis-Léopold Boilly. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ratten Cloughs.

I once wrote a post on Rotten Row. In the middle of August, I received a letter dealing with place names beginning with Rotten, Ratten, Rooten, and Rowton. They occur in locations where vaccaries (cattle farms) occupied the hillside and where the presence of great quantities of rats was unlikely. In my post, I cited the opinion that Rotten ~ Ratten Row was originally a place infested with rats. Our correspondent, Mr. John Davis, suggested that the place names had something to do with raising cattle or oxen (the business of the vaccaries). He also wrote: “…there are three places in Fife with Routine Rows. I don’t know if there were vacccaries in Fife, but cattle were big business for the Scots from medieval times onwards.”

My attempts to shed light on this question were of no avail (and I suspected this result from the start, but at least I tried). Those who will take the trouble to read or reread the post on Rotten Row will see that I knew about the existence of many Rotten Rows (and not only of the famous one in Hyde Park) but refrained from any conclusions. The origin of place names is a branch of etymology in which I am not a specialist. The easily available dictionaries supply no information. I can only say that quite often similar, almost identical place names go back to different etymons. There is no absolute certainty that all the names mentioned in Mr. Davis’s letter have the same origin. Rotten can of course be the product of folk etymology. The same holds for Ratten, with its reference to rats. If someone among our readers has hypotheses on this score, they will be most welcome.

Herring and sieve in the Scandinavian languages.

This is another echo of an old post. Norwegian has sil “sieve,” sil “lesser sand eel,” or “sand lance” (this is the fish the Germans call Tobiasfisch), and sild “herring.” In sil, the vowel is long and l is short. By contrast, in sild, in which d is mute, the vowel is short but l is long. In Old Icelandic, “herring” was sild (with both consonants pronounced), while the “sand lance” was síl (long i, short l). Even the relationship between the two fish names is disputable (though one of the best dictionaries says that they are undoubtedly akin, but the adverb undoubtedly occurs in etymological works only when there is serious doubt). Although the origin of sild “herring” poses problems, it cannot be a congener of sil “sieve,” which is related to German Seihe (the same meaning) and goes back to some form like sihila-. The verb related to it meant “to sift, strain.” And since I keep referring to my old posts (not a big surprise: there have been more than four hundred of them), I can mention my discussion of the idiom it is raining cats and dogs. The first component of Norwegian silregn (sil) “violent shower,” most probably, is cognate with sil “sieve” (and to the verb sile, one of whose senses is “to pour down with rain”; in Swedish and Danish, its cognates refer to straining and drizzling!).

Finally, I was very pleased to see both quotations from Oscar Wilde identified, and considering that the first one was from The Canterville Ghost and that the time is apt, I wish our readers a spooky and joyful Halloween.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Etymological gleanings for October 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEtymology gleanings for September 2013“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1

Related StoriesEtymology gleanings for September 2013“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1

The many strengths of battered women

One woman, to save money to prepare for leaving her abusive husband, sewed $20 bills into the hemlines of old clothes in the back of her closet. Another woman started volunteering at her school so she could keep close watch over her children and earned Volunteer of the Year at her school. Another woman reached out to her family, who provided her and her son with food and shelter and helped her retain a high-quality lawyer which enabled her to resolve custody issues in a way that protected her children as well as herself.

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month and it is the perfect opportunity to take a moment to appreciate the amazing strength and resilience that battered women show when coping with the problem of domestic violence. Battered women protect themselves and their loved ones in many, many ways. By stereotyping battered women as passive and in denial, we are missing the chance to help them build on their strengths and their own coping efforts. We are shortchanging ourselves, too, because we are missing the opportunity to learn some of the truly inspirational and heroic acts that all part of the daily existence of many battered women.

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month and it is the perfect opportunity to take a moment to appreciate the amazing strength and resilience that battered women show when coping with the problem of domestic violence. Battered women protect themselves and their loved ones in many, many ways. By stereotyping battered women as passive and in denial, we are missing the chance to help them build on their strengths and their own coping efforts. We are shortchanging ourselves, too, because we are missing the opportunity to learn some of the truly inspirational and heroic acts that all part of the daily existence of many battered women.

Battered women often make choices to protect their children and other loved ones. Sometimes this means leaving, but other times this can mean staying if the batterer has threatened to kidnap the children or wage a nasty custody battle in court. More than one in four battered women are worried about losing custody of their kids. Like most mothers, they would gladly risk their own personal harm if they thought it would help protect their children. Sometimes battered women are protecting dogs or cats from murder and abuse.

Many social service and health care providers do women a grave injustice by ignoring or dismissing the importance of faith — another place where many battered women turn. When access to many public social services is only getting harder and harder, with more forms, more waiting lists, and higher co-pays, churches are some of the most easily accessed and most generous social institutions in the country. Most agencies serving domestic violence victims (police, hospitals, shelters) emphasize short-term emergency services. Women can easily run into maximum stays in shelters (often 30 days, sometimes even less). Research by Cattaneo and colleagues has shown that months after reaching out for formal professional help, women are more likely to still be in touch with their churches than with either shelters or the police.

Contrary to the myths about secrecy and denial, research shows that about 90% of battered women have disclosed the abuse to at least one person, most often family or friends. Extensive data also show that many women turn to professional help, ranging from calling the police to going to shelter to joining a support. Additionally, battered women seek help at rates that are similar to other crime victims and to people experiencing psychological problems.

Finally, there are all sorts of invisible and understudied strategies: saving money, following standard recommendations in safety plans, protecting oneself from digital harassment and identity theft, or seeking couples counseling. Multiple studies suggest that counseling can help some couples, especially those where only more minor violence has occurred.

Step back and consider all of these protective strategies together, and the result couldn’t be more different than the unfair and damaging stereotypes about denial and passivity. We recognize that some soldiers struggle with what they have seen during war without painting all soldiers as helpless. We manage to acknowledge the enormous losses that follow hurricanes or other natural disasters without concluding that the victims are weak when it takes time to reconstruct their lives. We know how to give help and respect at the same time. Battered women also need help and respect as they cope with the complex problem of domestic violence. This Domestic Violence Awareness Month, let’s honor all of the victims of domestic violence by letting go of harmful stereotypes and building on strengths.

Sherry Hamby, Ph.D. is author of Battered Women’s Protective Strategies: Stronger Than You Know, which will be released this month by Oxford University Press. She is Research Professor of Psychology at Sewanee, the University of the South and founding editor of the APA journal Psychology of Violence. Battered Women’s Protective Strategies: Stronger Than You Know provides a new strengths-based framework for understanding coping with domestic violence. The book also presents a new safety planning tool, the Victim Inventory of Goals, Options, and Risks (the VIGOR) to help put this strengths-based approach to practice.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Crying woman sitting in the corner of the room, with phone in front of her to call for help. © legenda via iStockphoto.

The post The many strengths of battered women appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Woo woo versus doo doo”Halloween witches: ladies not for burningCome together in Adam Smith

Related Stories“Woo woo versus doo doo”Halloween witches: ladies not for burningCome together in Adam Smith

Halloween witches: ladies not for burning

Why is Halloween associated with witches? Look back beyond the twentieth century and you will find few connections. The 31st of October has long been a day of great religious significance of course. It is All Hallows’ Eve, the build-up to the Catholic All Saints’ Day, and then All Souls’ Day on 2 November. This was a time when the worlds of the living and the dead were at their closest. Protestant authorities dismissed this ritual period as Catholic superstition, and some states re-designated 31 October as Reformation Day in commemoration of Martin Luther’s momentous initial challenge to the Papacy. So nothing to do with witchcraft or suspected witches, who were very much alive and thought to be wreaking misery for their neighbours. Look at the witch trial records from across Europe and Colonial America and we find little association with Halloween. So if there is no venerable historic link between witchcraft and Halloween, we must look for more recent developments and we must look to America — for it was here that the Halloween tradition the world knows today was forged.

It is no surprise, perhaps, that part of the answer lies with the rise of modern marketing and branding. How does one dress up as a witch for Halloween, as many thousands will be doing this 31 October? Basically you stick a black pointy hat on your head. Depictions of witches with pointy hats began to appear in children’s books in eighteenth-century England, probably inspired by earlier black steeple hats worn in stereotypic depictions of seventeenth-century Puritans. By the end of the nineteenth century the pointy-hatted witch had become a widespread image in print. It was at this moment that Salem, Massachusetts, comes into the picture. It was there that a jeweller named Daniel Low began to produce souvenir spoons depicting a witch with a pointy hat and broom. Their success kick-started the transformation of Salem into the marketing creation ‘Witch City’, and the pointy-hatted witch was replicated on numerous ‘Witch City’ products.

Hallowe’en. Holiday postcards. Raphael Tuck & Sons, ca. 1910. Courtesy of NYPL Digital Gallery.

At the same time as this witch image was proliferating in marketing and the mass media, the nature of American Halloween custom was changing. With its roots in Irish mischief night, American youths had traditionally marked Halloween by performing such malicious acts as greasing railway tracks, smashing windows, and overturning outdoor toilets. But from the 1950s onwards the sanitised American trick-or-treat and costume bonanza we know today was beginning to spread. The remarketing of Witch City into Halloween City by local entrepreneurs from the 1980s onwards was a significant element in this transformation. “It’s America’s biggest Halloween party and you’re invited!” one promotional site proclaims today. The now inseparable link between witchcraft and Halloween was forged.

There is another link in the story though. One of the most active players in creating Halloween City was a Wiccan named Laurie Cabot. In 1971 she set up a ‘Witch Shop’ in Salem selling witchcraft paraphernalia. The Wiccan religion, founded by the retired British civil servant Gerald Gardner in the 1950s, adopted the ancient seasonal calendar of the pagan Irish Celts, where 31 October was celebrated as Samhain, one of four key calendar celebrations. This festival marked the beginning of winter, a time of feasting but also when the spirits were most likely to intrude on the world of humans. So for modern pagan witches like Cabot the link between witchcraft (as a re-invented modern religion) and Halloween was perfectly obvious. But how did knowledge of this association reach the wider American public?

Modern pagan witchcraft was first impressed on America’s consciousness by a larger-than-life English Wiccan named Sybil Leek, who was, in the words of one US newspaper in 1968, “America’s most famous resident witch.” From her first visit to the United States four years earlier the vivacious Leek became a popular television and newspaper figure, promoting her life as a witch and explaining the ways of her coven. It became something of a press tradition to ask Sybil Leek what she had prepared for Halloween. Asked in a syndicated piece in 1969 what she was up to on 31 October, she replied: “Halloween is our major religious holiday … It is our New Year’s. I never heard of trick-or-treat until I came to this country.” A year later another feature running with the headline, “Modern Halloween Myths Join Centuries-Old History,” ended with the punch-line, “The new look in witches is being promoted by British self-styled witch Sybil Leek in New York, surely ‘a lady not for burning.’”

Owen Davies is Professor of Social History at the University of Hertfordshire and has written extensively on the subject of magic. His new book America Bewitched: The Story of Witchcraft after Salem is the first full history of witchcraft in modern America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Halloween witches: ladies not for burning appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGhosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!New York City goes undergroundGridlock and The Federalist

Related StoriesGhosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!New York City goes undergroundGridlock and The Federalist

A Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship Online

The nights darken, the wind howls, and branches (or ghostly fingers?) tap against your windowpane. This can only mean one thing – Halloween approaches! To celebrate the day of ghouls, ghosts and other creatures which go bump in the night, we’ve compiled a list of University Press Scholarship Online’s most spine-chilling chapters (available free for a limited time). Join us as we take a frightful tour around the darker parts of UPSO.

‘ The Zoophagous Maniac: Madness and Degeneracy in Dracula ’ in The Most Dreadful Visitation: Male Madness in Victorian Fiction by Valerie Pedlar (Liverpool)

The infamous Prince of Darkness was first introduced to us in Bram Stoker’s classic Dracula, apparently inspired by a hideous nightmare the author had had. Its heady interplay between realism and fantasy, and its overt fin-de-siècle fears about gender and sexuality, caused great sensation on its first publication. Here, Pedlar examines how the notion of insanity relates to the novel’s conception of masculinity, and focuses on the horror which comes as the text consistently breaks down the fragile demarcation between sanity and madness.

‘Yōkai Culture: Past, Present, Future’ in Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai by Michael Dylan Foster (California)

The Japanese folkloric tradition is littered with strange creatures, ghosts, and monsters known as yōkai. These supernatural beings can be traced back to some of the oldest of Japanese literatures, but this chapter examines the renaissance they began to undergo during the 80s and 90s, and continue to do so to this day. It begins with a section on the J-horror genre; Japanese horror films that entered the global market during the late 1990s and reworked yōkai into contemporary settings with terrifying results. It also goes on to examine the yōkai behind the massively-popular cultural phenomenon, Pokémon (pocket monsters).

‘ Hell in Our Time ’ in Hell in Contemporary Literature: Western Descent Narratives since 1945 by Rachel Falconer (Edinburgh)

Since its very conception, Hell has both fascinated and horrified Western writers, philosophers, and artists alike. In this introductory chapter of her monograph, Rachel Falconer examines modern imaginings of Hell. Beginning by asking “is Hell a fable?” she quotes an exchange in Marlowe’s Dr Faustus. After selling his soul, Faustus tells Mephistophilis “I think Hell’s a fable”, to which the demon replies “Ay, Faustus, think so still, ‘till experience change thy mind.” Shudder.

‘ Touched by a Vampire Named Angel ’ in From Angels to Aliens: Teenagers, the Media, and the Supernatural by Lynn Schofield Clark (Oxford)

The stake-wielding vampire-hunter and wise-cracking school girl Buffy the Vampire Slayer burst onto television screens in 1999, and has since gone on to become a much-beloved cult-classic. Joss Whedon’s series, as well as later spin-off Angel, draws draw heavily on the myths and narratives of organised religion and vampire lore. Clark investigates this further, positioning the religious themes within the context of mainstream popular entertainment. The chapter ends with the show’s embracing of the individual’s need for community, and her capacity for transformation.

‘ Zombie Movies and the “Milennial Generation ” ’ by Peter Dendle in Better off Dead: The Evolution of the Zombie as Post-Human, ed. Debroah Christie and Sarah Juliet Lauro (Fordham)

The image of the B-movie Hollywood zombie — a slow and shuffling corpse with dubious designs on your cranial cavity — is one that still exists today. This chapter, however, charts the rise of a new and arguably more terrifying breed of undead: the fast zombie. Made famous by indie hits such as Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later, this zombie disrupts all the expected conventions laid by its older ancestors, and is… well… fast. Dendle seeks to explain the speed of this new breed in a world of instant downloads and immediate gratification, and our own sped-up expectations.

Barney Cox is Marketing Executive for University Press Scholarship Online and Oxford Scholarship Online.

University Press Scholarship Online (UPSO) brings together the best scholarly publishing from around the world. Aggregating monograph content from leading university presses, UPSO offers an unparalleled research tool, making disparately published scholarship easily accessible, highly discoverable, and fully cross-searchable via a single online platform. Research that previously would have required a user to jump between a variety of books and disconnected websites can now be concentrated through the UPSO search engine.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Halloween party balloons. © Matt Chalwell via iStockphoto.

The post A Halloween reading list from University Press Scholarship Online appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Hallowe’en reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsGhosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!Shakespeare in disguise

Related StoriesA Hallowe’en reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsGhosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!Shakespeare in disguise

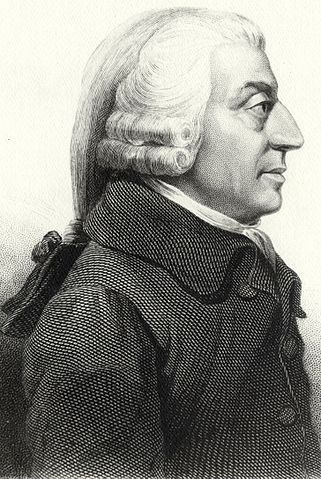

Come together in Adam Smith

I support a classical liberal worldview. I call to social democrats and conservatives alike: Be fair. Let us treat one another like fellow Smithians and come together in Adam Smith.

Adam Smith said we judge under the guidance of exemplars. That is a central principle of The Theory of Moral Sentiments. All moral sentiment, that is, all approval or approbation of human conduct, is enshrouded in sympathy. Sympathy with whom? Most of all, with moral exemplars as taken into our breast.

Adam Smith said we judge under the guidance of exemplars. That is a central principle of The Theory of Moral Sentiments. All moral sentiment, that is, all approval or approbation of human conduct, is enshrouded in sympathy. Sympathy with whom? Most of all, with moral exemplars as taken into our breast.

Exemplars exemplify virtue in particular instances. Smith gave us particular instances in abundance, by writing and rewriting two of humankind’s greatest works, as well as a few essays—about 1600 pages worth. We work with Smith’s sentences in developing and reforming our sensibilities about what our duties are and how we best fulfill them. Smith generously gave us a moral exemplar.

Smith is our best exemplar, better than any of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We need to work our way back to Adam Smith. He propositioned that every case of moral approval be subject to a query.

For example, Hank approves of Jim’s action. Samantha asks: Hank, wherein do you find sympathy for your approval of Jim’s action? Hank must be ready to lead Samantha to his exemplar, Jean-Jacques (an exemplar with whom Hank finds sympathy). The procedure prompts Hank and Samantha to talk about how Jean-Jacques sees matters like that of Jim’s action.

When Hank and Samantha come together in Jean-Jacques, Samantha may then say, “Sorry, I think Jean-Jacques is all wet on the matter.” “Well, Samantha,” Hank replies, “wherein do you find sympathy for that disapproval of Jean-Jacques?” Samantha answers: “In Ludwig” (Samantha’s exemplar). Now the conversation grows to the matter of Ludwig’s view of Jean-Jacques’s view of matters like that of Jim’s action. By layers, the procedure opens us up to different views of things.

Hank may then take issue with Ludwig’s view. “Oh, Samantha, you cannot slavishly follow Ludwig, your Master and Exemplar!” And Hank is right, of course.

In referring to Ludwig, Samantha does not so much identify the one with whom she finds sympathy, but characterizes that one in a way that Hank will find meaningful. The one with whom Samantha finds sympathy is the man in the breast, a figurative being she has developed during her life. By referring to Ludwig, she gives Hank a flavor of her man in the breast, as concerns matters like Jim’s action.

“Well, Samantha,” Hank might say, “even though your man in the breast resembles Ludwig in matters like Jim’s action, my man in the breast does not. Mine resembles Jean-Jacques, so where does that leave us?”

Adam Smith urges them on. He would say to Hank:

Hank, your man in the breast is the representative of an impartial, super-knowledgeable, benevolent spectator. And Samantha’s man in the breast, too, is a representative of the same spectator. (In fact, that goes for everyone, so the spectator is universal.) Now, as you and Samantha have not found sympathy in the matter of Jim’s action, there must be a problem in the representations developed in your breasts. We all know that none of us has full or direct access to the impartial spectator, that each of our man-in-the-breasts is merely human. Talk with Samantha about how you think the impartial spectator would look at your man in the breast vis-à-vis her man in the breast.

Smith’s proposition is to knowingly buy into two procedures. First, we see all moral approval as enshrouded in sympathy. Second, we mutually seek a common standpoint to address our moral differences. The procedures prompt us to come together to enter into each other’s ways of seeing, to tolerate our differences, to consider that maybe our man in the breast should change somewhat. In embracing Smith’s proposition we better accommodate our differences, maybe even resolve them to some extent.

One of the most remarkable things about Smith is how universally he is beloved. Economists, political scientists, sociologists, psychologists, historians, philosophers, and humanities scholars love him. Believers and skeptics love him. Social democrats, conservatives, and classical liberals love him.

Smith accommodates such diversity by bypassing some of the pitfalls that divide us. His proposition bypasses, for instance, the absolutism-relativism dichotomy: The impartial spectator is universal, but that which she surveys is rich and variegated, the historical tree of particularistic human contexts; she approves of “steal the bread” at one branch and not at another. The survey is universal, and it condemns many social customs—Smith condemned many. But rules are formulated in relation to situations to which they pertain. By narrowing the set of situations we make the rule more “absolute.” By widening the set so as to take in situations in which we approve of exceptions to the rule, we make the rule only presumptive, or “relative” to the situation within the set.

By being good Smithians and receiving others as good Smithians, we overcome stereotypes and come together to improve judgment and conduct in matters of common concern.

Daniel Klein is professor of economics at George Mason University, where he leads a program in Adam Smith. He is also associate fellow at the Ratio Institute in Stockholm. He is the author of Knowledge and Coordination: A Liberal Interpretation.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Profile of Adam Smith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Come together in Adam Smith appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPaul Collier on immigrationDear Russell Brand; on the politics of comedy and disengagement´Operation: Last Chance´, dilemmas of justice, and lessons for international criminal tribunals

Related StoriesPaul Collier on immigrationDear Russell Brand; on the politics of comedy and disengagement´Operation: Last Chance´, dilemmas of justice, and lessons for international criminal tribunals

Dear Russell Brand; on the politics of comedy and disengagement

Out Paxo’ing Paxman might be one thing but it is quite another to make the leap from comedian to serious political commentator. Russell Brand claims to derive his authority to speak out on the state of democratic politics from a source beyond ‘this pre-existing paradigm’ which can only really relate to his position as an (in)famous comedian. The problem with this claim is that – as many comedians have themselves admitted – in recent years the nature of political comedy and satire has derived great pleasure and huge profits from promoting corrosive cynicism rather than healthy skepticism.

Russ,

I’m writing to let you know that when people talk about you I usually feel a dull thud in my stomach and my eyes involuntarily glaze over. Your relationship with a shallow, generally brash and often abusive contribution to the cult of modern celebrity represents a lot of what is wrong with the world. Therefore, I was expecting your guest editorship of the New Statesman and your interview with Jeremy Paxman to be similarly inane and egotistical affairs. And yet – and I really hate to admit this – your arguments possessed a certain depth and intensity that left me strangely impressed. Have you really just been playing the fool for all this time?

To be honest poor Jeremy was not on good form. (I wonder if there is some reverse Samson-like spell at play that weakens his powers as he gets increasingly hirsute). However, your opening position about not deriving your authority from ‘some pre-existing paradigm’ but from an alternative source of legitimacy made me wince as I reflected on the broader contemporary role of comedians and satirists vis-à-vis political disengagement and apathy. In recent months there has been a groundswell of opinion against political comedy and satire as evidence grows of its social impact and generally negative social influence (especially over the young). ‘The whole comic-entertainment species is under-attack’ John Walsh recently argued in The Independent ‘there’s a groundswell of opinion that too many stand-ups are smug, over-paid, potty-mouthed enemies of the common people’. Janice Turner recently observed in The Times that there was ‘a tang of the school bully in the satirists barbs’ and highlighted Sandy Toksvig’s recent description of Michael Gove on the BBC’s The News Quiz as a ‘foetus in a jar’ before Toksvig added that Gove ‘had a face that makes even the most pacifist of people reach for the shovel’ [cue laughter and wild applause].

You might think this is all just good fun and that politicians deserve everything they get. But isn’t there a deeper tension at play here that makes your recent contribution somewhat at odds with the general direction of your profession? John Morreal, a leading international authority on the social impact and role of humour has written that ‘satirists have justified their trade by saying that satire corrects the shortcomings being laughed at’ but what if political comedy and satire actually contributes to and reinforces the shortcomings that are being laughed at? Mick Billig, author of Laughter and Ridicule, also questions whether political comedy and satire are always a ‘good’ thing, especially when ‘the message more readily spread is skepticism’. It is at exactly this point that comedians and writers scoff at the suggestion that anything has changed and without fail remind me of the historical contribution of writers such as Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift or caricaturists such as James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. Yet such nostalgic reflections overlook the simple fact that the world has changed and so has political comedy and satire. The rise of the 24/7 media machine with ever more pressure on ratings combined with the rich pickings offered by mass market DVDs and large-scale arena tours has fuelled a transition best captured in David Denby’s notion of the change ‘from satire to snark’. The latter being snide, aggressive, personalized: ‘it seizes on any vulnerability or weakness it can find – a slip of the tongue, a sentence not quite up-to-date, a bit of flab, a flash of boob, a blotch, a wrinkle, an open fly, an open mouth, a closed mouth ‘ but all designed to reinforce the general view that politics is failing and politicians are bastards. In a recent piece in the Financial Times (a paper not known for fun and jokes) John Lloyd felt forced to ask ‘Has political satire gone too far?’

“Satirists often say that their trade is necessary to excoriate the decisions or prick the egos of the powerful: that they are necessary to the functioning of a democratic society; that by wit they can say what commentary and news and even polemic cannot… [and yet] Satire that is polemic can turn ugly and authoritarian when it has powerful media behind it.”

Just think of the changing nature of political comedy and satire in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1950 the then Chairman of the BBC, Lord Simon, blocked the broadcasting of a light comedy about a fictional Labour minister and nuclear secrets on the basis that ‘this is not the moment in world history to weaken respect for democracy by jokes of this kind’. The BBC, he claimed, had a duty ‘to do what we can to maintain and strengthen democracy and the belief in democratic values’. Fast forward through the path-breaking satire of That Was The Week That Was in the 1960s, through to the slightly sharper Not The Nine O’Clock News and Yes, Minister in the 1970s and 1980s; through to Spitting Image in the late 1980s and 1990s and the weekly politician-bashing of Have I Got News For You from the 1990s into the noughties and finally to programmes like The Thick Of It and In The Loop with their docu-entertainment style and non-stop expletives. In thinking that political comedy and satire is heading in the wrong direction, I am by no means alone. Jon Stewart, presenter of The Daily Show and arguably the leading American satirist has argued ‘if satire’s purpose was social change then we are not picking a very effective avenue’. Stewart’s Rally To Restore Sanity on the 30 October 2010 attracted around a quarter of a million people and was designed to provide a venue for members of the public to be heard above what Stewart described as the more vocal and extreme 15-20 per cent of the American population. Debates continue to rage as to whether this was a spoof event or an attempt to make a serious point about the state of the American media – ‘the country’s 24-hour politico–pundit perpetual panic ‘conflict-inator’’ – but at the very least Stewart recognized the power of political comedy and satire to frame political debate and public attitudes.

On this side of the Atlantic, concerns have been raised by Rory Bremner, Armando Ianucci, Eddie Izzard, and David Baddiel about the increasingly aggressive and destructive nature of modern humour – and this brings me back to your recent entry to the political fray. I believe in change. I want genuine alternatives. But I want to know what role political comedy and satire might play in producing this new way of organizing our society and facing the common challenges we face. How can political comedy and satire help us engage with that widespread feeling of disconnection and then channel it into a new beginning? I ask these questions because – like you – I am angry because for me politics is real. There was no Eton or Oxbridge in my life and I have an acute grasp that politics is not just some peripheral thing that I turn up to, as you put it, ‘once in a while to a church fete for’. Politics defined me and it defined you. It matters. My question is really whether satire continues to play a positive social role that helps explain just why politics matters? If, as I think, your profession is generally destructive – politically concerned with ‘joking apart’ rather than pulling together – surely this undermines your claim to an ‘alternative’ source of authority beyond the ‘pre-existing paradigm’?

One last thing, the way you stuffed Paxo was exquisite – the line about the ‘lachrymose sentimentality’ of his ‘emotional porn’ was, if anything, a little too good – and yet there was just one moment when you let your mask slip. Do you remember? Right at the beginning when Paxman jabbed you about your right to edit a political magazine? The jump between your feigned ignorance of ‘the typical criteria’ for an editorial invitation and your leap to a comparison with Boris Johnson seemed just a touch too quick, too pre-prepared: ‘he has crazy hair, quite a good sense of humor, doesn’t know much about politics’. The problem with this comparison with the King Clown of British politics is that everyone knows that Boris may be foolish but he is no fool. He is, in fact, a deceptively polished über-politician who uses buffoonery and comedy as a political self-preservation mechanism. You also seem to have pushed buffoonery and comedy to new limits but (unlike Boris) you have never actually dared to step into the political arena. I just wonder if it’s a little too easy to heckle from the sidelines, to carp at the weaknesses and failings of others, to suggest that there are simple solutions to complex problems and to enjoy power and influence within society but without ever shouldering any direct responsibility. Apologies if I am being just a tad too serious and boring about these issues!

All the best,

Matt

Professor Matthew Flinders is Director of the Sir Bernard Crick Centre for the Public Understanding of Politics at the University of Sheffield. He is currently working on a new project for BBC Radio 4 called (funnily enough) Joking Apart that examines the changing nature and impact of political comedy and satire and will be broadcast on 21 December 2013. Author of Defending Politics (2012), you can follow Matthew Flinders on Twitter @PoliticalSpike and read more of his blog posts on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Russell Brand by Kafuffle. [CC-BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Dear Russell Brand; on the politics of comedy and disengagement appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGridlock and The FederalistPaul Collier on immigrationUrban warfare around the globe [interactive map]

Related StoriesGridlock and The FederalistPaul Collier on immigrationUrban warfare around the globe [interactive map]

October 29, 2013

Ghosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my!

With the 31st of October quickly approaching, scores of costumes and vast amounts of candy are disappearing from stores as we prepare for Halloween. But, with all the time and money put into the decorations and celebration, how much do we really know about this widely celebrated tradition? How many of us can even define the term, Halloween?

For centuries, there has been a fascination with all things supernatural. What began as a pagan ritual to welcome the dead amongst the living has evolved into an other-worldly realm complete with vampires, witches, and monsters. What better time than October to explore the strong literary tradition devoted to the darker creatures of our imagination? If you dare, see just how much you know about Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Salem witches while learning about the origins of Halloween.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

This Halloween season, Oxford puts together a spectacularly spooky list of supernatural titles. Rife with classics like Frankenstein, Dracula, and the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde, it also includes modern day explanations of our superstitions and fears associated with the unknown: On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition, and America Bewitched: Witchcraft After Salem.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Spooky halloween candles in dark on Public Domain Images.

The post Ghosts, goblins, and ghouls, oh my! appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesA Hallowe’en reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsShakespeare in disguise“Woo woo versus doo doo”

Related StoriesA Hallowe’en reading list from Oxford World’s ClassicsShakespeare in disguise“Woo woo versus doo doo”

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers