Oxford University Press's Blog, page 890

October 24, 2013

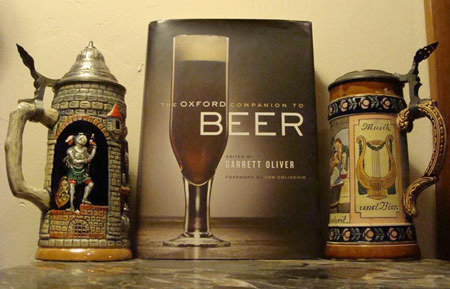

Oktoberfest Library

“Beer does not resemble wine so much as it resembles music.”

– Garrett Oliver

October’s upon us once more!

But before you head out to the bar

To assuage your Fall thirst,

Hit the library first

So you won’t imbibe brew that’s subpar.

O Lolita may trip down the tongue,

But fine beer takes a path more far-flung.

From the bite of the hops

To the back-finish drops

Of the malt, beer’s delights must be sung!

A poetics of beer I’ll intone.

For our civilization has grown

From Egyptians’ first zythos (1)

And ancient beer mythos

To hops from American zones.

In The Oxford Companion to Beer (2)

You’ll find gleanings from all hemispheres.

From the A&BVs

To the E&SBs,

You’ll parse beers from the dark to the clear.

The Companion will greatly enhance

Readers’ hoppy historical sense.

You’ll find Grossman (3) and Guinness,(4)

Gambrinus (5) and Ramses,(6)

And Luitpold, Bavarian Prince.(7)

And if you would brew it yourself,

Bamforth’s Beer (8) should belong on your shelf.

For economists, Marxists,

And others who hark its

World market, see Swinnen himself.(9)

Conversation goes better with beers.

Tis the talk in the pubs that endears

Them to drinkers of bitter

Who turn from their Twitter

To thoughts laid too deeply for tears.

While you relish your pints topped with foam,

Your beer talk could enrich bar and home.

With this Oxford tome trio,

You’ll parse brews with brio–

A bona fide beer gastronome.

Notes

(1) Classical Greek writers’ term for Egyptian barley beer, derived from “to foam.”

(2) The Oxford Companion to Beer, ed. Garrett Oliver. Foreword by Tom Colicchio. Oxford, 2012.

(3) Ken Grossman, founder, Sierra Nevada Brewing Company.

(4) Arthur Guinness, founder, Arthur Guinness & Sons.

(5) Jan Gambrinus, legendary King of Beer and Patron Saint of Brewers.

(6) Ramses II (19th Dynasty), Pharaoh and brewer.

(7) Luitpold, Prince of Bavaria and CEO of König Ludwig GmbH & Co.

(8) Charles Bamforth, Beer: Tap Into the Art and Science of Brewing. 3rd. ed., Oxford, 2009.

(9) Johan F. M. Swinnen, ed. The Economics of Beer. Oxford, 2011.

This poem originally appeared on the Massachusetts Review blog.

Garrett Oliver, editor of The Oxford Companion to Beer, is the Brewmaster of the Brooklyn Brewery and author of The Brewmaster’s Table: Discovering the Pleasures of Real Beer with Real Food. He has won many awards for his beers, is a frequent judge for international beer competitions, and has made numerous radio and television appearances as a spokesperson for craft brewing.

The Oxford Companion to Beer is the first major reference work to investigate the history and vast scope of beer, featuring more than 1,100 A-Z entries written by 166 of the world’s most prominent beer experts. It is first place winner of the 2012 Gourmand Award for Best in the World in the Beer category, winner of the 2011 André Simon Book Award in the Drinks Category, and shortlisted in Food and Travel for Book of the Year in the Drinks Category. View previous Oxford Companion to Beer blog posts and videos.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only food and drink articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Oktoberfest Library appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEp. 1 – BOOZE!Ep. 1 – BOOZE! - EnclosurePut THIS in your iPod. (Or Zune…whatever.)

Related StoriesEp. 1 – BOOZE!Ep. 1 – BOOZE! - EnclosurePut THIS in your iPod. (Or Zune…whatever.)

Vernon Scannell: War poetry and PTSD

Sometimes you can be well into writing a book before it tells you exactly what it’s about. I started work on Walking Wounded: The Life and Poetry of Vernon Scannell thinking that I was writing a simple biography of an unjustly neglected poet – which of course I was. Scannell, a serial deserter in World War II who was on the beach at D Day and seriously wounded in Normandy, had the life a biographer dreams of, full of incident and controversy – but none of that would mean anything without the poetry.

But the more I read about his life after the war – the monumental drinking binges, the black-outs, the terrifying, sweating nightmares, and most of all the raging, unreasonable jealousies and the sickening violence that he meted out to his wife and, later, his lovers – the more I began to wonder whether this was not also the story of a man seriously damaged by his wartime experiences.

A lengthy interview with Dr Felicity de Zulueta, a leading consultant psychiatrist who specialises in the treatment and effects of stress, confirmed my suspicions. No one is going to make a firm diagnosis of a man who has been dead for several years, but to her, Scannell’s life story represented a familiar account of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “It is almost a textbook example,” she said. “I certainly wouldn’t have been surprised by Scannell’s story if he had walked into my office.”

Vernon Scannell during his time in the Army

Before the war, his childhood had been a miserable combination of brutality from a bullying father and cold rejection from his mother, who stood aside as his father beat him up – another classic contributory factor leading to PTSD. It is a condition that can lead to violence, fear, sudden flashes of uncontrollable jealousy, difficulties in forming lasting relationships, and an overwhelming sense of shame. As they try to cope, sufferers often turn to drink or drugs, with disastrous results.

It sounded like a description of the man I had been writing about and getting to understand, even though Scannell, a man of his time, was predictably dismissive of such diagnoses. In one of his later poems, he mused on accounts of soldiers returning from Iraq with post traumatic stress disorder, and scoffed that, on the way to D Day sixty years before, what he had shared with the other soldiers

“Was pre-traumatic stress disorder, or

As specialists might say, we were shit-scared.”

But for all his assumed scepticism, his poetry leaves no doubt that he understood the condition and what it means to its sufferers. Gunpowder Plot tells of the terrifying memories stirred by Bonfire Night fireworks; the dramatic monologue Casualty – Mental Ward presents with chilling simplicity a wounded soldier who knows that “something has gone wrong inside my head”; A Binyon Opinion confronts the soft-focus sentimentality of “They shall not grow old” with the poet’s own more stark memories of his dead friends. And then there is Walking Wounded:

“And when heroic corpses

Turn slowly in their decorated sleep

And every ambulance has disappeared,

The walking wounded still trudge down that lane

And when recalled they must bear arms again.”

There is much more to Scannell’s poetry than the War, of course. It is the poetry of common people – his view of the Resurrection, for instance, focuses on an elderly bag-lady in canvas shoes, a sleeping drunk, and a little mongrel lifting its leg against a gravestone. When he writes poems for children, he sees the world through the child’s eyes – the corniest teenage crush, for Scannell, is as significant as the grandest of grandes passions. When he faces death – as he does, bravely – he finds himself sustained by the simplest of comforts – “Schubert and chilled Guinness”.

But, particularly as we approach Remembrance Day, it is the war poems that seem most relevant. It’s hard to think of another poet who wrote so movingly and so consistently about the plight of the victims of war who didn’t die, and who went on to live a life in which both they and those they loved were terrorised by the past. His words will resonate for hundreds of young men and women home from Iraq and Afghanistan, and for their families as well.

Combat Stress is a charity that supports some 5,400 ex-servicemen and women who are victims of PTSD, depression, and anxiety. Its Communications Manager, Stephen Clark, says that many more are reluctant to come forward. “We are seeing a gradual change in society’s attitudes towards mental ill-health, but there still exists a great deal of stigma that results in many veterans suffering in silence, too ashamed to seek help,” he says.

When stories about my biography appeared online, comments reflected this lack of understanding of PTSD. “Revolting coward” is one that sticks in the memory – a harsh judgment on a man who fought in North Africa and at D Day, who saw his friend disemboweled by a shell, and who was shot in both legs.

Still, at least they demonstrate how desperately Scannell’s poetry is needed today.

James Andrew Taylor is the author of Walking Wounded: The Life and Poetry of Vernon Scannell. He has written ten other books, including biographies of the Arabian traveller Charles Doughty, and the 16th century cartographer Gerard Mercator.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photograph of Vernon Scannell from Scannell family collection.

The post Vernon Scannell: War poetry and PTSD appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World WarShakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remainsBloody but unbowed

Related StoriesIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World WarShakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remainsBloody but unbowed

October 23, 2013

“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2

It is hard to hide something (anything) from Stephen Goranson (see his comment to Part 1), who will find a needle in a haystack, and The Canterville Ghost is a rather visible needle. Yet Oscar Wilde is no longer as popular as one could wish for. The scandal that ruined his life is remembered better than his works. Only his three or four society dramas and perhaps The Happy Prince are recognized by many. The Canterville Ghost is one of the most delightful tales written in English, and my goal was to encourage the world (doesn’t the whole world follow this blog?) to read or reread it.

The cautious findings of last week can be summarized as follows. The English word deuce is, rather certainly, a borrowing of Low (that is, northern) German duus (Standard German Daus). In German it surfaced about five centuries ago but reached England considerably later. Deus is not an alteration of Latin deus “God” or of Latin diabolus “devil,” and, though it sounds like Dutch droes “devil” (with which it rhymes), we have no way of showing “beyond reasonable doubt” that this similarity is more than a coincidence. The name of the merciless Roman general Claudius Drusus has hardly anything to do with droes. Gallo-Roman dusius “demon” looks like a perfect etymon of German duus, but dusius was recorded a millennium before duus and never again, so that one wonders what underground existence it could have led for such a long time.

Soon after the previous post appeared I was asked about the term Gallo-Roman. In this context it can be translated loosely as “a Latinized Celtic form.” Last time I mentioned Elmar Seebold, who considers a connection between dusius and German Daus probable. Joshua Whatmough (1897-1964), an expert in the dialects of Ancient Gaul, also thought that duus (he seems to have known only Westphalian dus) might have been of Celtic origin. With all due respect to such eminent authorities, I would prefer to leave the putative Celtic etymon of the German word in limbo. The Scandinavian origin of deuce, defended by Wedgwood (but proposed long before him), should, in my opinion, be disregarded.

At present, the widely recognized etymology of deuce stems from the OED. I will quote a version of it from The Century Dictionary, with the abbreviations expanded:

“As ‘the deuce’ was the lowest throw [at dice], the phrase, uttered in vexation, seems to have come to be accepted as an equivalent to ‘the plague,’ ‘the mischief’, and with a little more emphasis, to ‘the devil’, with which the alliteration would readily associate it. Like other words used in colloquial imprecation, deuce has lost definite meaning, and has been subjected (in Low German, German, and Scandinavian) to more or less wilful [sic] variation with other words. Cf. Low German de duks!, equivalent to Engl. the dickens!, Low German dücker, deuker, deiker, ‘the deuce’.”

I quoted Charles P. G. Scott of The Century Dictionary because etymological devilry was one of his favorite subjects and, unlike so many others, he never repeated Murray’s opinions unthinkingly. At the beginning of the entry, he mentioned Dutch droes and Low German droos. Apparently, he considered them to be alterations of duus. Scott’s passing reference to the Scandinavian forms has not been developed, and it is unclear what he meant. Tuss ~ tusse ~ tosse seem to belong to a different group of words. Skeat eventually subscribed to Murray’s etymology, but Seebold (under German Daus) did not. (For the record: deuce “two at dice or cards” is from Old French deus, now spelled deux, from Latin duos “two.”)

Murray never had bad ideas, and his derivation of deuce is excellent. However, it can hardly be called final, even considering the fact that not too many etymologies are ever “final.” For example, the earliest form may have been druus, with duus going back to druus that had lost its r, rather than duus picking up r along the way (but to my mind, this is an unlikely scenario). While leafing through English dictionaries, one encounters dowse “to strike in the face,” dowse “to immerse; use as the divining rod,” dowse “to extinguish,” doze, as in bulldoze/bulldozer, in which it meant “to strike, whack, whip” (a doublet of dowse), and doze “sleep lightly.” Dizzy is also close by. The vocabulary is full of d-s/z words belonging to the “low register” of speech. Transplanted to English, duus found itself in good company.

Low German, Dutch, and Frisian have as many d-s/z verbs as does English, but there, in addition to the rarer meaning “strike,” we find references to madness (“dizziness”). The earliest recorded English quote in the OED has the phrase a deuce on you (with the indefinite article!), while the Germans, at least today, say ei Daus! (with the interjections preceding Daus). Those “curses” sound like fie upon you. Could it be that duus originated as an almost meaningless word with negative connotations? Something called duus was bad, and passing it on to a neighbor might have grave consequences (compare the plague on both your houses), in English perhaps not quite the same as in German.

Next on our agenda is doozy, a vague denomination of something extraordinary (“awesome”?). The word has been around since the beginning of the twentieth century. There is hardly any literature on it, and two of the three conjectures on its origin I have been able to find sound like a joke: doozy as an alteration of daisy or of the name of the great Italian actress Eleonora Duse (1858-1924). A third conjecture derives doozy from deuce. But though deuce has been attested with several spelling variants (deuse, duce, dewce, dewse, dooce, and doose), it does not seem to have ever had -z- in it. Probably doozy is not from deuce.

I have only a general idea of how doozy might come about. The syllable do, perhaps under the influence of do-do, is an ideal component of slang words (compare dude). The syllable -zy, regardless of how it is spelled, often carries humorous or slightly negative connotations: compare dizzy, tizzy, fuzzy-wuzzy, hussy ~ huzzy, crazy, sleazy, and so forth. Monosyllables like jizz, fizz, and whizz, to say nothing of jazz, belong here too. In some British dialects, the diminutive of boy is boysie (no connection with the cricketing term bosie), and, since I have already mentioned Oscar Wilde today, I may say that Lord Alfred Douglas, his disreputable boon companion and lover, was universally known as Bosie, for this is what his mother once called him (“boysie, little boy”), and it is to “Dear Bosie” that De Profundis was addressed. I would like to venture the hypothesis that doozy is made up of dooo! followed by the pseudo-suffix -zy—an expression of amazement (almost an interjection).

Floozy is contemporaneous with doozy. There are periods in the history of languages when nonsensical rhyming words suddenly begin to proliferate. Even if, as the OED suggests, floozy goes back to flossy (Victorian slang for “shining, ostentatious”), its final shape, with the vowel -oo- in the middle and -zy at the end, makes one think that the word as we today know it, owes something to sound symbolism. All this is guesswork. Alas, it is so easy (ee-zi) to foozle an etymology and bamboozle the readership. You say to yourself: “My post on floozy is a doozy,” only to realize that after two weeks of profound meditation you are almost exactly where you were on Day One. There is only one comfort: “Lots of people act well, but very few people talk well, which shows that talking is much the more difficult thing of the two, and much the finer thing also.” I concur. Anyone can now find the source of this maxim.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Dice players. Roman fresco from the Osteria della Via di Mercurio (VI 10,1.19, room b) in Pompeii. Filippo Coarelli (ed.): Pompeji. Hirmer, München 2002, ISBN 3-7774-9530-1, p. 146. Photo by WolfgangRieger, 15 March 2009. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1Ostentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poeticaAre you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and folly

Related Stories“Deuce,” “doozy,” and “floozy.” Part 1Ostentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poeticaAre you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and folly

Participating in the OAPEN program

I was recently invited by Oxford University Press (OUP) to have my book, The Republic in Danger, published on the online open access library OAPEN. After a few general questions, I happily accepted. Why?

OAPEN is an online platform on which books from major academic publishers are freely available to download in as PDFs. Unlike some eBook formats, the PDF is printable and the text can be copied and pasted. Add to these benefits the fact that OAPEN is fully searchable, and it is clear that OAPEN editions have the potential to greatly increase a reader’s ability to interact with a text. OAPEN’s major feature, however, is that the books are free! Users do not need to sign-up to anything, log into anything, or agree to anything — they merely visit the site and download the content of their choice.

As this seems, from the point of view of the author, to be economically irrational, some justification for my decision to participate in OAPEN seems warranted. So, to return to my original question: Why? The answer is related to my desire to publish in the first place.

As a PhD thesis The Republic in Danger did the job. Original, provocative, and most importantly, worthy of the degree for which it was written. Mr Pettinger became Dr Pettinger, my wife was relieved, and I could move on to other things, i.e., paid work. So why publish? Wealth and glory? No. Roman history has its popular appeal, but academic history is a gateway neither to Hollywood nor, generally, a Nobel Prize (Theodore Mommson being the, now ancient, exception). Furthermore, I am not a paid academic, or aspiring academic, with a quota to meet. I am a civil servant who remains passionately interested in history and committed to the progress of historical knowledge, but without an obvious need to publish. I published because, as I sat in my study and watched the navy blue covered thesis turn dusty grey, the thought of five years of research standing silent and ignored seemed shocking and wrong. No doubt pride was involved, but I believed, and still believe, that The Republic in Danger has important things to say.

Roman Emperor Tiberius

The Republic in Danger covers politics in Rome between 6 BC and AD 16, a period marking the final stages of Augustus’ rule and the transition to Tiberius, a man who had won nothing and depended, for his power, on succession. Most historians treat the political processes of these years as being, for the most part, settled and predictable. They also treat them as being exclusively related to court politics. By reconsidering the prosecution in AD 16 of a young Roman noble, M. Scribonius Drusus Libo, I am able to show that those years were in fact both unstable and unpredictable. It was not obvious to anybody living at the time that Augustus’ authoritarian structure would last or that Tiberius would succeed him.This analysis provides evidence for the inherent instability of authoritarian regimes, especially in cultures with a democratic past or aspiration. Augustan Rome is therefore one example of a political system about which we have lately become more aware: Iran, Egypt, and Pakistan are all modern examples, and they are by no means alone. In addition to shedding light on the fragility of Augustan authoritarianism, I also account for its success. Augustus and Tiberius ruled via a delicate combination of violent coercion, dressed always in the garb of constitutional propriety, and a sense that their removal would cause utter ruin. The threat of civil war, famine, and economic turmoil was always made to seem real – and perhaps it was. They were also able to co-opt sections of society and make their satisfaction dependent on the success of the regime. This allowed the regime to rest assured that a great part of the community would rise up to protect it; again, Iran and Egypt are apposite modern examples.

The obligation to share findings with as many people as possible is fundamental to scholarship. Physical books will remain important, but their reach is limited by price and storage. In Australia, and no doubt many other places, libraries are slowly rationalising their collections, whilst the sheer number of books published each year in a given topic, such as Ancient History, makes it impossible for the majority to maintain a private library. OAPEN offers a solution, and in the process offers some advantages. Obviously my giving the book freely away gave me reason to pause, but, in the end, I could not justify my exclusion on the basis of potentially lost profits (I should point out that the effect on profit is not yet known, either way). OAPEN’s audience is global and, importantly, unrestrained by anything save their ability to access the internet. I could not ignore such massive potential. To do so would undermine my reason for publishing in the first place. Ultimately, societies which are truly free are built on nothing more secure than ideas freely exchanged, and in that formulation, scholars are duty bound to disseminate their work as widely and efficiently as possible.

Andrew Pettinger is currently an Associate of the Classics and Ancient History Department at the University of Sydney and works as a federal public servant. He is the author of The Republic in Danger: Drusus Libo and the Succession of Tiberius; an open access version of this publication is made available by OUP as part of the OAPEN-UK project.

Oxford University Press (OUP) is participating in OAPEN-UK, a pilot funded by JISC Collections and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) to gather evidence on the viability of open access monographs in the humanities and social sciences. Our participation is running for the duration of the final year of the trial, from September 2013 – September 2014.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only media articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Roman Emperor Tiberius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Participating in the OAPEN program appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe changing face of war [infographic]Urban warfare around the globe [interactive map]Why study economics?

Related StoriesThe changing face of war [infographic]Urban warfare around the globe [interactive map]Why study economics?

Why study economics?

As you begin your university course in economics, you’re probably wondering just how your studies will intersect with the world outside the classroom. In the following adapted excerpt from Foundations of Economics, author Andrew Gillespie highlights the importance of studying economics and provides visual walk-throughs of the some of the core concepts you’ll need to grasp to excel in your studies and to develop a full understanding of the economic landscape in which we live and work.

If you have ever wondered why the cost of a ticket to your favourite band’s last concert was so expensive, why you are paid so little in your part-time job, why your petrol is taxed so heavily, or why it is more expensive to get into a nightclub at weekends than during the week, or if you have ever wondered what influences the rate at which you change your currency into another when you go on holiday, why some people seem to be so much richer than others, or why some firms make more profits than others, then studying economics will be of interest to you! In fact, whether you know it or not, you are already an important part of the economic system. You are a consumer of products: every day, you are out there buying and consuming goods and services, and influencing the demand for them. You may also have a job, and so help to generate goods and services. If you are working, you are also paying taxes that are used to finance the provision of other products. However, simply being part of an economy is one thing; studying it is another.

By studying economics, you can develop an analytical approach that helps you to understand a wide range of issues from what determines the price of different products, to the causes, and consequences of unemployment, to the benefits of different forms of competition. By the end of this book, you should understand a whole range of economic issues, such as why some people earn more than others, why some economies grow faster than others, and why, if you set up in business, you might want to dominate a market.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The study of economics provides a number of models and frameworks that can be applied to a range of situations. The impact of an ageing population, price increases by your local supermarket, the returns on your investment by choosing to go to university, and the costs to society of smoking are all issues that you can analyse as part of economics once you have the necessary tools.

Click here to view the embedded video.

And at the heart of economics is human behaviour: what influences it and what happens when it changes? What makes people choose one course of action rather than another? If we want to change behaviour, what is the best way of doing this? If we want people to be more environmentally friendly, is this best achieved by taxing environmentally unfriendly behaviour? Or by subsidizing ‘good behaviour’ or by legislating? Economics affects people’s standard of living and how they live. The tax and benefits system will affect your incentive to work, your willingness to marry, to have children, to save money, and to have a pension. An understanding of economics therefore provides an insight into the factors that shape society and influence the success of your business or career.

Of course, you are not the only one wanting to understand the economy and the economic impact of policy decisions. Governments would also like to be able to influence the economy to achieve their objectives, such as faster economic growth and lower unemployment; most recently, there have been major debates on the best way to help governments to cope with major borrowings without causing another recession. Firms are interested in economic change because it will influence their ability to compete (for example, interest rates can affect their costs and demand for their products) and determine their future strategy (for example, what markets they should be targeting).

Click here to view the embedded video.

Employees are interested in economic conditions because these affect their earnings. Consumers want to know what is likely to happen to the prices of the things that they buy. Many different groups in society will therefore be interested in what influences the economy and how economies might change in the future. This probably explains why economic stories receive such media attention and why the subject has been studied so intensely over the years by economists.

Andrew Gillespie is Head of Business Studies and Accounts at d’Overbroek’s College, Oxford, and a visiting lecturer at Oxford Brookes University, Oxford. He is the author of Foundations of Economics and Business Economics. To see more economics concepts explained, visit the Foundations of Economics Online Resource Centre.

Economics students, are you interested in reviewing books, participating in surveys, giving feedback on cover designs, and more? The Oxford University Press Economics Student Panel is made up of select students from across the UK and Europe currently studying for Economics degrees. As a member of the panel, you’ll help us make sure our books continue to be relevant for real students. If you’d like to earn great rewards and have a fantastic addition to your CV, visit our website and apply now.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why study economics? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUrban warfare around the globe [interactive map]The changing face of war [infographic]‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance pay

Related StoriesUrban warfare around the globe [interactive map]The changing face of war [infographic]‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance pay

Dizzying new perspectives of vertigo research

In the last three decades vertigo science has been revolutionized by new examination techniques and improving understanding of physiological principles. It used to be the case that a great percentage of patients with vertigo and dizziness did not receive any definite diagnosis; today not only has this ratio improved dramatically but in the majority of cases an effective therapy may be started. This changed neurotology, a speciality bordering between ENT and neurology, from a field of frustrations to a source of success. This is valid even in general practice because many of the bedside tests and simple treatments are easy to learn and do not require any sophisticated, expensive apparatus.

When dealing with vertigo or dizziness, there may be acute cases and chronic recurrent complaints. In vertigo as emergency, the most urgent task is to identify the most dangerous, perhaps life threatening causes. In chronically recurrent vertigo, the patient may not have complained about it when seeing their doctor, which makes it difficult to find the cause and apply effective treatment.

Ten highlights from recent developments

1. Acute vestibular syndrome (acute dizziness lasting more than 24 hours) is most frequently caused by peripheral, viral vestibular neuritis or central ischaemic stroke in the brainstem or cerebellum. Superficially, they may present themselves in very similar ways. The differential diagnosis between the two is easy: a simple bedside examination consisting of the head impulse test – searching for direction changing nystagmus and/or vertical misalignment of the eyes – reliably identifies stroke in acute vestibular syndrome.

2. According to the latest literature, the quality of vestibular complaints (e.g. rotating vertigo, unspecific dizziness or imbalance) does not seem to be helpful in making the diagnosis, because in a clinical setting the descriptions of the quality of dizziness are unclear or inconsistent and therefore unreliable.

3. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, which is caused by dislocated otoconia, may be even more frequent than previously thought, because it may occur in many cases without the characteristic, repetitive eye movements (nystagmus) which are otherwise provoked by head position changes.

4. If, in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), otoconia are not glued to the cupula but instead move freely in the posterior canal then they can be flushed out by a special sequence of movements (equivalent to a backward somersault in two phases). This is also possible when the horizontal canal is involved. Then a horizontal sideways roll, the ‘barbecue roll’, seems to be the most effective treatment.

Cartoon drawn by B. Büki showing the semicircular canals and the utricle with the otoconia (white) on the utricular macula. Dislodgment of these crystals causes the most frequent vertigo syndrome, the paroxysmal positional vertigo.

5. Recently it has been suggested that vitamin D deficiency may be connected to repetitive exacerbations of BPPV and that vitamin D supplementation may possibly decrease the frequency of recurrences.

6. There is a new treatment for Menière´s disease, which has been proven to be more effective than placebo: a single intratympanic gentamicin injection, which stops the attacks by a mild inhibition of the responsible vestibular organ. This is especially good news, since otherwise the frequent, severe attacks may make normal life impossible.

7. With the new quantitative video-based head-impulse testing now available, the function of individual semicircular canals can be assessed reliably in an everyday clinical setting. This, together with vestibular evoked potentials, provides a powerful tool to assess all parts of the peripheral vestibular organs with a high resolution.

8. In the last few years, vestibular migraine, the “chameleon” of vertigo disorders emerged as a possible cause of, sometimes severe, vertigo and headache when no other central pathology can be found.

9. In the relatively recently discovered ‘labyrinth dehiscence syndrome’, a third window opens on the labyrinth in the direction of the intracranial space. This explains several, sometimes bizarre complaints, such as pressure-induced vertigo or when patients hear noises from their own body: ‘Doctor, I hear the movements of my eyes!’ Since the condition causes an apparent middle-ear hearing loss but without any pathology in the middle ear, otologists now better understand cases with pseudoconductive hearing loss, when ear operations cannot improve hearing.

10. Idiopathic chronic bilateral vestibular hypofunction (chronic vestibular insufficiency) may frequently cause constant dizziness in the elderly or after ototoxic antibiotic/cytostatic therapy. The diagnosis is easy, because the head impulse test is highly pathological, standing on foam with the eyes closed triggers falls, and the patients´ ability to read during head shaking decreases.

In conclusion, with all these new developments, it is certainly worthwhile to take time with vertigo patients. New syndromes explain mysterious complaints better; new, effective therapies bring relief more often than before. As G. Michael Halmágyi put it: “with some understanding of basic vestibular physiology, it is now possible, in my view, to make a reasonable diagnosis on history and examination in about 80% of dizzy patients … and to be able to treat successfully about 80% of them.”

Together with Alexander A. Tarnutzer, Béla Büki is the author of the Vertigo and Dizziness, a title in the Oxford Neurology Library. He is working as an otolaryngologist and neurotologist in Krems an der Donau, Austria. His special areas of scientific interest are fluid pressure increase inside the labyrinth and in the intracranial spaces and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo together with its variants without nystagmus.

Oxford Neurology Library is an exciting series of pocketbooks aimed at neurologists, trainees, neurology specialist nurses and other health care professionals covering the diagnosis and management of specific neurological conditions (e.g. Parkinson’s disease) as well as other topics of recent interest (e.g. deep brain stimulation in movement disorders). Each practical, evidence-based volume includes chapters covering clinical features, pathophysiology, and management, and brings the reader up to date on current developments.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cartoon drawn by B. Büki. All rights reserved.

The post Dizzying new perspectives of vertigo research appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance payMedical research ethics: more than abuse prevention?Urban warfare around the globe [interactive map]

Related Stories‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance payMedical research ethics: more than abuse prevention?Urban warfare around the globe [interactive map]

October 22, 2013

Urban warfare around the globe [interactive map]

What is the future of warfare? Counterinsurgency expert David Kilcullen’s fieldwork in supporting aid agencies, non-government organizations, and local communities in conflict and disaster-affected regions, has taken him from the mountains of Afghanistan to the cities of Syria. His experience in the last few years has led to new ways of thinking about the face of global conflict.

In Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla, he examines the rise of complex conflicts in highly networked urban environments through both scholarly research and first-hand experience. Gone are the skirmishes with terrorists and insurgents in isolated environments. Conflict is increasingly likely to occur in the slum settlements of sprawling coastal cities, where everyone has a mobile phone with an Internet connection to coordinate attacks — or resistance.

Click the pins on the map below to see images of urban warfare in action today.

View Out of the Mountains in a larger map

David Kilcullen is the author of the highly acclaimed Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla, The Accidental Guerrilla, and Counterinsurgency. A former soldier and diplomat, he served as a senior advisor to both General David H. Petraeus and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In recent years he has focused on fieldwork to support aid agencies, non-government organizations and local communities in conflict and disaster-affected regions, and on developing new ways to think about complex conflicts in highly networked urban environments.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Urban warfare around the globe [interactive map] appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe changing face of war [infographic]Place of the Year: History of the AtlasAnother kind of government shutdown

Related StoriesThe changing face of war [infographic]Place of the Year: History of the AtlasAnother kind of government shutdown

Five reasons to stay sober after October

Macmillan Cancer Support have raised over £1 million with their #gosober for October campaign. But is this a lifestyle that more of us should adopt permanently? Here are five great reasons to stay sober after October:

(1) Binge drinking in Britain is costing the NHS just under £3 billion a year, with over 1 million annual alcohol-related admittances to hospital. These figures have almost doubled in the last ten years.

(2) The consumption of alcoholic drinks may be a personal act, but personal behaviour in humans is heavily influenced by social and cultural factors. British ‘pub culture’ as described by Robin Room in Alcohol, where the pressure to ‘drink up’ has become a social norm, may be having a serious impact on the way in which we Brits perceive drinking.

(3) The health benefits of alcohol consumption are very limited. According to Lionel Opie, author of Living Longer, Living Better, alcohol is a two-faced friend — a little helps, but more than that harms substantially. The ‘red wine’ hypothesis, which states that the beverage has benefits extending beyond its alcohol content, may also have some truth in it; deep red grape juice has the same effect of inhibiting blood clots, but only in higher doses. A fine Pinot Noir — the author’s favourite — may therefore be safely considered part of a healthy diet, but only in small doses.

(4) In contrast, the negative effects of alcohol on the drinker can be enormous. In Alcoholism: The Facts the four stages of intoxication are described thus: the drinker becomes jocose, bellicose, then lachrymose, and finally comatose. These symptoms of jollity, aggression, depression, and then lack of consciousness might seem harmless enough the short term, but in the long term they can lead to cycles of dependency, particularly in social situations, that in turn can become addiction; and with addiction comes more serious health and social problems.

(5) An alcoholic can be defined as someone who drinks, has problems from drinking, but goes on drinking anyway. What sort of problems are we talking about? If we include issues such as poor health, memory loss, and embarrassment, as well as the negative impact that alcohol consumption can have on our relationships and bank balances, then could more of us have problems from drinking than we would like to admit?

If you think you or a loved one is engaging in problem drinking, it might be time to take action.

Alcohol and Alcoholism publishes papers on biomedical, psychological and sociological aspects of alcoholism and alcohol research, provided that they make a new and significant contribution to knowledge in the field. Papers include new results obtained experimentally, descriptions of new experimental (including clinical) methods of importance to the field of alcohol research and treatment, or new interpretations of existing results.

Alcohol has always been an issue in public health but it is currently assuming increasing importance as a cause of disease and premature death worldwide. Alcohol: Science, Policy and Public Health provides an interdisciplinary source of information that links together the usually separate fields of science, policy, and public health.

Living Longer: The heart-mind connection is written for all those who strive for optimal long-term health and the maximal functioning of their hearts and minds. Professor Lionel H. Opie sifts through the available information on the vast number of possible health promotion changes, varying from increased exercise to aspirin to green tea, and diets from Atkins to the vegetarian, with the aim of grading the validity of the evidence, asking questions such as, “Just how true are the studies” and “Just how compelling are the facts they claim”?

The fourth edition of Alcoholism, written by a group of Dr Goodwin’s former colleagues, whilst retaining much of Dr Goodwin’s original material, offering his unique perspective on alcoholism. The new edition includes updated information about the effects of alcohol consumption on the body, a new section on the particular sensitivity of women to the effects of drinking, and information and advice relating to the consequences of alcohol abuse for the abusers, their families and society.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Drunk young woman shallow DOF. © SylvieBouchard via iStockphoto.

The post Five reasons to stay sober after October appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance payMedical research ethics: more than abuse prevention?The economics of cancer care

Related Stories‘And he laid down his hammer and he died’: Health and performance payMedical research ethics: more than abuse prevention?The economics of cancer care

Getting and keeping the vote

Organizing for the women’s suffrage parade planned for 23 October 1915 in New York had taken months. By this time leaders of the New York movement were practiced at arranging such popular spectacles in a state that would be a significant prize, with parades its most effective, opinion-changing tactic. Finally, nearly seventy years after the Seneca Falls Convention and its call for women’s suffrage, the momentum seemed to be shifting. After years of ridiculing the notion of women as voters, Tammany Hall, the city’s enduring political machine, had declared its neutrality on the forthcoming referendum. By 1915 thirteen states, all west of the Mississippi, had enfranchised women; surely progressive New York might lead the way in the east. Meanwhile in the two-pronged strategy of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the federal amendment named for Susan B. Anthony had been voted out of the Senate Judiciary committee.

Pre-election parade for suffrage in NYC, Oct. 23, 1915, in which 20,000 women marched. Courtesy of the Bain Collection. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

On that warm sunny day nearly a century ago some 20,000 women, 2,500 men, 74 women on horseback, 143 automobiles with six suffragists in each, four floats with females representing Victory, Liberty, Freedom and Democracy, along with 57 bands numbering over a thousand musicians marched up Fifth Avenue. They passed the reviewing stand in front of the New York Public Library where a new convert Mayor John Mitchell waved. They moved on, up to 59th Street, greeted along the way by mostly appreciative crowds. The New York Times declared it “the latest, biggest and most successful of all suffrage parades.”

The intention was to impress upon men the justice of their cause and to rally their own supporters in the collective effort that the suffrage movement had become. As a cautionary note, paraders were instructed to keep their eyes to the front, refrain from talking and never respond to hecklers. “Remember you are marching for a principle.” In 1915 there was no better way to publicize the cause. Americans had always cherished their parades: the stirring drumbeat of the band, the eye-catching costumes of the marchers, the picturesque thematic floats, whether for independence on the Fourth of July or the celebration of a new president. As women sought civic equality, they adopted this familiar spectacle, their parades presenting a physical embodiment of their purpose.

Photograph shows four women carrying ballot boxes on a stretcher during a suffrage parade in New York City, New York. Suffrage parade, NYC, Oct. 23, 1915. Courtesy of the Bain Collection. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

Women arranged in orderly lines rebutted the argument that the fairer sex did not want the vote. Women in public spaces testified to the disruption of the ancient folklore that women should remain in the home. To march visually undermined the longstanding tenet that women were destined to home and domesticity, there to preside with piety and chastity, while men dealt with public affairs. Indeed it was the claim of some suffragists that women could clean up dirty politics — hence their white dresses. By carrying heavy banners embossed with their slogans, women negated the claim that they were too fragile to participate in manly politics.

For all its immediate success this parade on 23 October 1915 failed. Ten days later on 2 November 1915 the suffrage referendum lost; male voters in every borough in the city voted no to enfranchising women. But with tenacity their hallmark, the New York suffrage women began again; soon they were organizing another parade. In 1917 on the eve of another referendum 50,000 women marched carrying a petition signed by over a million supporters. This time the referendum passed, and New York became the fourteenth state to enfranchise women. By 1919 even the recalcitrant Woodrow Wilson supported a federal amendment, and in June 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment prohibiting the denial of the right to vote “on account of sex” was ratified by three-quarters of the states.

Today some of the predictions of women who never had the vote have been enacted by those who do. More women than men go to the polls in presidential elections and women reveal statistically different partisan voting patterns than men. Currently it is impossible to deny the vote on the basis of categories of race, gender, and ethnicity. Yet until the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s giving the executive branch the power of enforcement, white southerners prevented black men and women from voting through violence and intimidation.

Today our challenges involve efforts by those who would restrict voting for partisan advantage. Before 1920 men opposed expanding the suffrage because enfranchising women overturned their control not just in public arenas where exclusion from the electoral process testified to female inferiority. The vote, an act of personal sovereignty, also undermined male authority at home. Today now that the Supreme Court has overturned Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Republicans chip away at access to the polls under the fiction that widespread fraudulent voting exists. Currently we disenfranchise by preventing same day registration, by limiting voting hours and days, by demanding identifications, and by judicial weakening of necessary protections.

There are no parades to rally those who would prevent this erosion. Instead we need to remember the essential lesson taught by those suffrage marchers of the early 20th century. Only through persistence and diligence intended to rally public opinion can we protect the vote. Only by understanding and persuading others, as the suffrage women of New York did, that the vote is the fundamental transaction within a democratic society are we able to empower all citizens and enact the natural right ensured to all Americans.

Jean H. Baker is Professor of History at Goucher College. In addition to editing Votes for Women: The Struggle for Suffrage Revisited, she is the author of Mary Todd Lincoln: A Biography and The Stevensons: Biography of an American Family, among other books.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Getting and keeping the vote appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe wait is now overWomen’s Equality DayImages of jazz through the twentieth century

Related StoriesThe wait is now overWomen’s Equality DayImages of jazz through the twentieth century

Images of jazz through the twentieth century

From the Harlem Rag to grand pianos to the Grammy awards to the international stage… Jazz has had many different incarnations since its origins 120 years ago. This brief slideshow with images from Mervyn Cooke’s The Chronicle of Jazz conveys the diversity of change in jazz performers throughout the years. Innovation, experimentation, controversy, and emotion — all found in the most imaginative and enduring music.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Harlem Rag. Private collection.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Jelly Roll Blues. The Frank Driggs Collection.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fate Marable's band. The Frank Driggs Collection.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Sydney Bechet. © Redferns-William P. Gottlieb/Library of Congress.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Mamie Smith. The Frank Driggs Collection.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Louis Armstrong. The Frank Driggs Collection.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Dorothy Dandridge. BFI Stills, Posters and Designs, London.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Fats Waller. Redferns/Michael Ochs Archives.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Billie Holiday & Louis Armstrong. BFI Stills, Posters and Designs, London.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Ella Fitzgerald. Photo Max Jones Files/Redferns.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Dinah Washington. © William Claxton/The Special Photographers Library.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Wynton Marsalis. © Redferns, London (Photo David Redfern).

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Mary Lou Williams. © Getty Images/Time & Life Pictures/Gjon Mili.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Japanese keyboard player. © Muga Miyahara.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Jamie Cullum. © Getty Images/AFP/Rafa Rivas.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Diana Krall. © Getty Images/Jakubaszek.

Dr. Mervyn Cooke is Professor of Music at the University of Nottingham and has published extensively on the history of jazz, film music, and the music of Benjamin Britten. His most recent books include The Chronicle of Jazz, The Cambridge Companion to Jazz, The Hollywood Film Music Reader, The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera and Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters of Benjamin Britten.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Images of jazz through the twentieth century appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGravity: developmental themes in the Alfonso Cuarón filmPlace of the Year: History of the AtlasFive quirky facts about Harry Nilsson

Related StoriesGravity: developmental themes in the Alfonso Cuarón filmPlace of the Year: History of the AtlasFive quirky facts about Harry Nilsson

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers