Oxford University Press's Blog, page 893

October 15, 2013

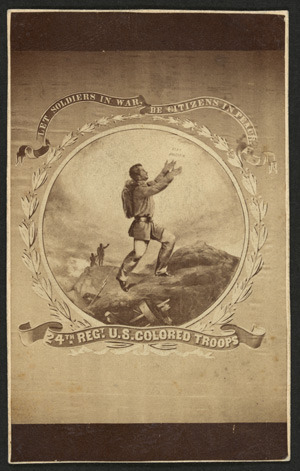

Appomattox and black freedom

This year’s Civil War sesquicentennial commemorations have highlighted the theme of emancipation, and appropriately so: Lincoln’s promulgation of his Emancipation Proclamation in January of 1863 was a watershed event. But if we cast our eyes back to African American freedom commemorations in the wake of the war, we are reminded that emancipation was a process, not an event — and that its fulfillment hinged on Confederate military defeat.

Over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, African Americans celebrated a series of “freedom days” — milestones in the emancipation process — including the anniversaries of the end of the slave trade; the abolition of slavery in the British West Indies; the date of Lincoln’s preliminary emancipation proclamation; the fall of the Confederate capital; the announcement of emancipation in Texas; and the passage of the 13th and 15th Amendments. Prominent among these freedom days was the ninth of April, the date of Robert E. Lee’s 1865 surrender to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. The enshrinement of Appomattox as an emancipation milestone rested on three interconnected claims: that the Union army’s victory over Lee dramatized black agency and heroism; that the Virginia setting of the surrender gave it special meaning for African Americans; and that the magnanimous terms of surrender which Grant offered Lee symbolized the promise of black citizenship and of interracial reconciliation.

From the end of Civil War end until the early 20th century, African American commentators, including veterans, ministers, politicians, reformers, editors and historians, celebrated Appomattox as the apogee of black military heroism. They were keenly aware of, and eager to call the nation’s attention to, the fact that seven different regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) participated in the Appomattox campaign and were present at the surrender.

In that last battle of his fabled Army of Northern Virginia, Lee found that the last road south, the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road, was blocked, by the “bristling bayonets, and glistening musket barrels” of black soldiers in blue: the 8th, 29th, 31st, 41st, 45th, and 116th regiments of the USCT (the 127th waited in the wings). His escape route closed off, Lee was left no choice but to surrender. These regiments were a microcosm of black life in America. They included ex-slaves trained at Kentucky’s Camp Nelson and free blacks trained at Philadelphia’s Camp William Penn. They included men who would become race leaders in the postwar era, such as the renowned historian George Washington Williams, the influential A.M.E. minister William Yeocum, South Carolina judge and legislator William J. Whipper, and Baptist editor William J. Simmons, who was the journalistic mentor to Ida B. Wells.

In that last battle of his fabled Army of Northern Virginia, Lee found that the last road south, the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road, was blocked, by the “bristling bayonets, and glistening musket barrels” of black soldiers in blue: the 8th, 29th, 31st, 41st, 45th, and 116th regiments of the USCT (the 127th waited in the wings). His escape route closed off, Lee was left no choice but to surrender. These regiments were a microcosm of black life in America. They included ex-slaves trained at Kentucky’s Camp Nelson and free blacks trained at Philadelphia’s Camp William Penn. They included men who would become race leaders in the postwar era, such as the renowned historian George Washington Williams, the influential A.M.E. minister William Yeocum, South Carolina judge and legislator William J. Whipper, and Baptist editor William J. Simmons, who was the journalistic mentor to Ida B. Wells.

Not surprisingly, African American soldiers and those civilians who had championed their enlistment quickly seized on the USCT’s critical role in the surrender as a point of pride and a vindication. For example, Thomas Morris Chester, a correspondent embedded with the Army of the James, reveled in the fact that black regiments had participated in the “vigorous campaign” that gave “Lee’s forces as trophies to the Union army.” The Confederate capitulation at Appomattox was especially sweet because it was a rebuke to the haughty elite of the Old Dominion, the self styled “F.F.V.’s” or “first families of Virginia,” whom Chester, after the surrender, wryly dubbed the “Fleet-Footed Virginians.”

USCT troops, according to postwar black discourse, had not only defeated Lee but hammered the final nail into the coffin of slavery itself. Emancipation was contingent: Confederate victories kept freedom at bay and Union ones brought freedom into view. Thus countless reminiscences, memoirs and oral histories testify that slaves first learned of and experienced emancipation at the moment of the Union’s triumph at Appomattox. As James H. Johnson of South Carolina explained, after Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation, “the status quo of slavery kept right on as it had.” It was only when “Gen. Lee surrendered,” he observed, that “we learned we were free.”

Black remembrance of Appomattox as a freedom day incorporated not only the themes of black heroism and liberation, but also of clemency; African Americans inscribed a civil rights message into the magnanimous terms of the surrender. George Washington Williams praised USCT soldiers for treating the vanquished Confederates with “quiet dignity and Christian humility.” In his view, African American magnanimity at Appomattox was an exercise of moral authority — a conscious effort, as purposeful as Grant’s own clemency to Lee — to break the cycle of violence slaveholders had perpetrated; to refute the white supremacist prophecy that emancipation would open a pandora’s box of racial strife; and to prove that the freedpeople had earned full citizenship.

These themes would animate black commemorations of Appomattox, which persisted into the 20th century, in the North as well as the South. On the 9 April 1914, for example, the congregation of Philadelphia’s Miller Memorial Baptist Church gathered to celebrate “the Emancipation of the Ethiopians from American slavery, by the surrender of Robert E. Lee to General U.S. Grant at Appomattox.” Ten years later, in 1924, Roscoe Simmons, a columnist for the Chicago Defender, reminded his readers that “slavery began in Virginia” and that, fittingly, “it ended in Virginia” with Lee’s capitulation. This made Appomattox, in his view, African Americans’ “place of salvation.” Such discourse reminds us that 9 April 1865 was a touchstone for the politics of race and reunion.

Elizabeth R. Varon is Langbourne M. Williams Professor of American History at the University of Virginia. A noted Civil War historian, she is the author of Appomattox: Victory, Defeat, and Freedom at the End of the Civil War; Disunion!: The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859; We Mean to be Counted: White Women and Politics in Antebellum Virginia; and Southern Lady, Yankee Spy: The True Story of Elizabeth Van Lew, A Union Agent in the Heart of the Confederacy, which was named one of the “Five Best” books on the “Civil War away from the battlefield” by the Wall Street Journal.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Appomattox and black freedom appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe end of Nez PerceInterview with Charles Hiroshi GarrettIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Related StoriesThe end of Nez PerceInterview with Charles Hiroshi GarrettIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Celebrating World Anaesthesia Day

World Anaesthesia Day commemorates the first successful demonstration of ether anaesthesia on 16 October 1846, which took place at the Massachusetts General Hospital, home of the Harvard School of Medicine. This ranks as one of the most significant events in the history of medicine and the discovery made it possible for patients to obtain the benefits of surgical treatment without the pain associated with an operation. To celebrate, we’re highlighting a selection of British Journal of Anaesthesia podcasts to learn more about anaesthesia practices today.

Failed tracheal intubation in Obstetrics

Dr A. Quinn, from Leeds General Infirmary in the UK, lead author of a recent BJA paper on failed tracheal intubation in obstetric anaesthesia talks us through this important UK national prospective survey. Using the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) of data collection, Dr Quinn and colleagues confirm the expected incidence of failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics at one in 224, and that the incidence of failed intubations hasn’t decreased in the last 20 years, despite advances in airway techniques. Age, BMI, and a recorded Mallampati score were significant independent predictors of failed tracheal intubation. (January 2013 || Volume 110 – Issue 1 || 20 Minutes)

Long-term quality of sleep after remifentanil-based anaesthesia: a randomized controlled trial

Dr Rik Thomas talks with Dr Manuel Wenk (lead author) about the inspiration and background behind this unusual randomised controlled trial. Dr Wenk summarises what we already know about the effects of opioids on sleep, and why remifentanil may differ in this respect. Dr Wenk goes on to explain his unexpected findings and the potential long-term effects remifentanil may have on sleep quality after surgery. (February 2013 || Volume 110 – Issue 2 || 16 Minutes)

Human factors and patient safety in anaesthesia

The majority of morbidity and mortality due to anaesthesia is unfortunately caused by human error. In this podcast, Professors Alan Merry and Jennifer Weller gives us an introduction to human factors in anaesthesia, the types of errors that occur and strategies to prevent them. We explore communication failure within the operating theatre environment, the differences between a blame-free and just culture, and the anaesthetist’s role in promoting patient safety. (May 2013 || Volume 110 – Issue 5 || 32 Minutes)

Sound Asleep

NAP5 and the recent controversial guidance from NICE are putting commercial depth of anaesthesia monitors under intense scrutiny. How do they work? Does their use correlate with a reduced incidence of awareness? What is the neurobiological basis for the relationship between EEG activity and depth of anaesthesia? A group from Glasgow have developed a new type of DOA monitor that is a radical departure from the conventional number generation box. Dr John Glenn and Dr Bernd Porr explain how their electroencephalophone (EEP) harnesses the power of the human ear as the system’s signal processing unit. By transducing the EEG signal into a real time audible sound wave, the EEP produces a sound that can be used to distinguish between the anaesthetised and the awake patient. Drs Glenn and Porr discuss the potential advantages the EEP holds over traditional DOA monitors, future testing and research, and their open approach to development of this exciting new technology. (September 2013 || Volume 111 – Issue 3 || 32 Minutes)

Propofol use by non-anaesthetists in the Emergency Department

Opinions on the use of propofol by non-anaesthetists remain controversial and divided. In this podcast Dr Gavin Lloyd, an emergency physician from The Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, gives his point of view and describes his experience developing a training program and governance framework for propofol use in the resus room. Dr Lloyd and Dr Thomas explore the relative risks and potential benefits of propofol use in the ED, discuss the results from the accompanying paper and look at the recently published College guidance for the sedation of adults in the ED. (October 2013 || Volume 111 – Issue 4 || 25 Minutes)

For more information, visit the dedicated BJA World Anaesthesia Day webpage for a selection of free articles.

Founded in 1923, one year after the first anaesthetic journal was published by the International Anaesthesia Research Society, British Journal of Anaesthesia (BJA) remains the oldest and largest independent journal of anaesthesia. Enjoy the podcasts? Subscribe to the BJA podcast series now!

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating World Anaesthesia Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWorld Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseasesFine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patientThe demographic landscape, part II: The bad news

Related StoriesWorld Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseasesFine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patientThe demographic landscape, part II: The bad news

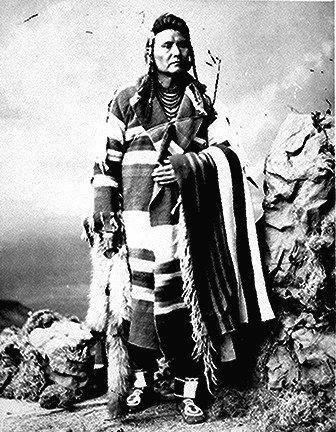

The end of Nez Perce

In early October of 1877, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce surrendered to the United States military after a harrowing five month war to reclaim their ancestral homeland from gold rushing Americans. The following excerpt from Elliot West’s The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story describes the settlement made and the challenging move north the displaced Nez Perce faced as a result of it.

In the end, according to Yellow Wolf, honor tipped the decision. Some Nez Perces had chafed at their impression that when Joseph had met with Miles, Joseph had asked to end the fight. On one of Captain John’s and Old George’s visits, they brought this message:

“Those generals said to tell you: ‘We will have no more fighting. Your chiefs and some of your warriors are not seeing the truth. We sent our officer [Jerome] to appear before your Indians—sent all our messengers to say to them, ‘We will have no more war!’

“Then our man, Chief Joseph spoke, ‘You see, it is true. I did not say ‘Let’s quit!’

“General Miles said, ‘Let’s quit.’

“And now General Howard says, ‘Let’s quit’

“When the warriors heard those words from Chief Joseph, they answered, ‘Yes, we believe you now.’

“So when General Miles’s messengers reported back to him, the answer was, ‘Yes.’”

That yes was not a collective yes, just one man’s assent, albeit a man many would choose to follow. A sizeable minority in the camp, most of them from the bands of White Bird and the late Looking Glass and Toohoolhoolzote, chose to make a try for Canada. White Bird deeply distrusted white leaders, apparently never considered surrendering, and as one who had always pushed for Canada instead of Crow country, would not miss his chance now. After dark, he and others so inclined slipped through the cordon of soldiers, who apparently played it loose, caught up in the mood of release and assuming it was finished. These escapees joined others who had broken away during the first fighting but had stayed, watching from the fringes, to see how things turned out. The refugees felt their way in strings and clusters across the blustery flatlands toward the international boundary. While Miles and Howard left the impression that only a handful had slipped through their hands, the Nez Perce Black Eagle compiled a list of 233 or 234 who broke free between the attack on September 30 and October 6. If he was close to accurate, more than a third of those who were at Snake Creek when Miles ordered the first charge eventually got away.

Soon after Joseph’s message, a final parlay was held at a grassy spot between two lines. Apparently, it deepened Joseph’s impression that Miles was in charge and would send them home to Idaho. Yellow Wolf has Miles brimming with goodwill: “No more battles and blood! From this sun, we will have good time on both sides… plenty time for sleep, for good rest.” Howard, he said, was the same: “It is plenty of food we have left from this war…. All is yours.” The understanding sealed, the two groups returned to their camps, and a couple of hours later, between two and three o’clock in the afternoon on October 5, came the formal surrender. Joseph rode slowly up a steep rise at the west end of the bluff. Walking beside him were five other men, their hands on his horse’s flanks or on his leg. The six spoke softly among themselves. Joseph’s chin was on his chest and his hands crossed across the saddle’s pommel. His Winchester carbine lay across his lap. A gray shawl was around his shoulders, and his hair was in two braids and tied up with otter skin. It was obvious that, if not the bands’ war leader, he had put his life repeatedly on the line. He had grazing wounds on his forehead, his wrist, and the small of his back, and the sleeves and body of his shirt were peppered with bullet holes. Miles later “begged the shirt as a curiosity.”

Standing and waiting for Joseph were Howard, Miles, Lieutenant Wood, and two other officers. Ad Chapman, the civilian who had been present since the fighting at White Bird, was there as interpreter. As Joseph dismounted and approached, his companions stepped back. Facing Howard, Joseph offered his rifle, but Howard, following his promise to let Miles finish the business, stepped away and gestured toward Miles. He took the carbine. All shook hands. Joseph, with Chapman translating, seems to have said something like “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more.” With that, it was over.

Joseph (Hinmaton-Yalatkit), Nez Perce’chief; full- length, standing. Photographed by William H. Jackson, before 1877. From National Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Elliott West is Professor of American History at the University of Arkansas and author of The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The end of Nez Perce appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive things you may not know about Chester ArthurInterview with Charles Hiroshi GarrettIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Related StoriesFive things you may not know about Chester ArthurInterview with Charles Hiroshi GarrettIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Interview with Charles Hiroshi Garrett

After nearly a decade of work, the second edition of The Grove Dictionary of American Music—often called AmeriGrove—is finished. In September 2013, shortly before publication, I talked with Editor in Chief Charles Hiroshi Garrett about the project.

Tell us how you got involved with the second edition of AmeriGrove.

Charles Hiroshi Garrett in the University of Michigan library with 1986′s The New Grove Dictionary of American Music.

In 2004, I first learned about the possibility of updating AmeriGrove. The initial plan was for me to serve as an assistant editor to Editor in Chief Richard Crawford, one of the most esteemed scholars in the field of American music. After Professor Crawford decided to concentrate his energy on other projects, including a biography of George Gershwin, I was approached by Grove/OUP and invited to take on the role as Editor in Chief. By 2005, organizational and administrative planning was underway; by the following year, much of the project had begun to take shape. I was especially happy to accept the challenge in part because I enjoyed a personal connection to this project: I am a former student of H. Wiley Hitchcock, a pioneer of American music studies, who co-edited the original AmeriGrove dictionary with Stanley Sadie.How did you go about creating the list of articles that were included in the dictionary? What role did the first edition play in the development of content for the second edition?

The shape of the updated AmeriGrove reflects a remarkable effort of teamwork and scholarly cooperation. Nearly seventy editors and advisors—specialists in American music representing top universities and research institutes from across the United States and around the world—devoted substantial time to the project. Each of these participants, each assigned to key subject areas, helped design the coverage, scope, and content of the dictionary. The editorial team also received and reviewed suggestions from Grove readers and many scholars of American music. Over the course of the project, the contents of the dictionary continued to expand as editors and contributors recognized potential areas of growth and commissioned new articles.

The original dictionary (1986) was extremely significant to our initial planning for the updated AmeriGrove in terms of design, content, and philosophy. It gave us a general blueprint, which transformed as the updated dictionary grew to twice its size, and we retained its inclusive approach to defining American music. Every article from the original dictionary was reviewed, and nearly all of them were retained and updated for the updated dictionary. Because the original dictionary was never digitized, we were especially keen on making the fruits of the original publication available to today’s online researchers. We also drew on American-related content of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2001): many of these articles were updated by their original authors for inclusion in the updated dictionary.

Together, our editorial team decided which entries should be reprinted, which should be altered, which should be replaced, and which new topics should be considered for inclusion. As much as we consulted earlier Grove dictionary sources for guidance, the new AmeriGrove also contains thousands of originally conceived articles written by new contributors.

The first edition of the dictionary in many ways established a foundation for the field of American music study that has flourished in the years since its publication. How did you use it in your own work?

The first edition of the dictionary in many ways established a foundation for the field of American music study that has flourished in the years since its publication. How did you use it in your own work?

Even though it is nearing its 30-year anniversary, the first edition of the dictionary has continued to prove essential for readers because its coverage and depth in certain areas has remained unmatched until the new AmeriGrove. I have long consulted the first edition in the same ways I hope that readers will come to value the new dictionary—as a trusted source founded on scholarly expertise, as a first stop for bibliographical advice, and, through its many long and detailed articles on broad subjects, as a fascinating and fun way to expand my musical knowledge.

You can read more about this interview later this month at Grove Music Online.

Charles Hiroshi Garrett is Associate Professor of Musicology at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater and Dance, as well as a faculty associate of the university’s American Culture Program. He has served as review editor and assistant editor of American Music, the journal of the Society for American Music. His book Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century, which was awarded the Irving Lowens Memorial Book Award by the Society for American Music, was published by University of California Press in 2008. He is co-editor ofJazz/Not Jazz: The Music and Its Boundaries (University of California Press, 2012) and author of numerous articles, including “Shooting the Keys: Musical Horseplay and High Culture” in The Oxford Handbook to the New Cultural History of Music, ed. Jane F. Fulcher (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Anna-Lise Santella is the Editor of Grove Music/Oxford Music Online. Her article, “Modeling Music: Early Organizational Structures of American Women’s Orchestras” was recently published in American Orchestras in the Nineteenth Century, edited by John Spitzer (U. Chicago, 2012) and you can also read her recent article on the American women’s orchestra movement on University Press Scholarship Online. When she’s not reading Grove articles or writing about women’s orchestras, you can find her on twitter as @annalisep.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Interview with Charles Hiroshi Garrett appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe golden wings of the bicentennial: Giuseppe Verdi at 200Judging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneBreaking Bad’s Faustian Cast

Related StoriesThe golden wings of the bicentennial: Giuseppe Verdi at 200Judging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneBreaking Bad’s Faustian Cast

October 14, 2013

In the wake of the uprisings

In early 2011, a series of revolutionary chain reactions against uncompromising and authoritarian regimes set the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) in motion. The popular uprisings spread quickly across the Arab world and their effects continue today. While the world’s attention today is on the latest security developments in Egypt and Syria, this blog post will focus on multilateral approaches to foreign policy and trade. As is well known, the civil protests have affected existing geopolitical balances. Prominent international actors are being challenged to strategically rethink their policies towards the region.

In its own attempt to address the rapid changes, the European Union (‘EU’ of ‘Union’) has been making structural efforts to engage bilaterally with Arab States. In addition, the EU has also enforced multilateral processes by embracing the expertise of regional multilateral organizations, including the League of Arab States (Arab League), and to a lesser extent the African Union (AU), the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Union representatives met regularly with their regional counterparts and have been active participants in informal gatherings (Friends of Syria, Friends of Yemen). At least partly driven by its own experiences in achieving peace and economic prosperity through integration, the Union has proposed tools that would facilitate the active engagement of Arab countries with each other.

This approach – enhancing regional cooperation through multilateral processes – is not entirely new to European foreign policy thinking. In fact, the Arab uprisings have accelerated existing processes more than they have redefined them. The EU, with its close historical, geographical, and cultural links with the region, has been moulding its policies vis-à-vis the Arab world for decades. Two key examples demonstrate this.

Flag of the Arab League

The first concerns the noteworthy rapprochement between the EU and the Arab League. Led by Secretary-General Amr Moussa, the League reinvented itself as an advocate of the protesters’ claims throughout the Arab world. This is remarkable for an organization that for a long time had been primarily occupied with safeguarding the independence and sovereignty of its Member States. Moreover, until recently, it operated in a climate of weak democratic practice. Even so, the enhanced EU-Arab League cooperation did not come out of thin air. The Arab League had been included in all meetings of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (the central multilateral instrument to govern EuroMed relations, EMP) since 2008. In March 2010, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs had visited the headquarters of the Arab League in Cairo, where she indicated her appreciation for the ‘growing co-operation with the Arab League, with programmes that are aimed at bringing us closer together’.

The Arab uprisings clearly created momentum for the EU and the Arab League to continue those cooperative efforts. The Union and the Arab League established a Situation Room, permanent focal points and an EU-Arab League Liaison Office in Malta to implement joint projects. The Union also trains Arab League officials and shares good practices. In addition to the immediate political and operational support, the EU and the Arab League have engaged in exploratory talks regarding how the EU can support cooperation between Arab League Member States in the economic, social, educational, cultural and legal fields. The structural redefinition of the EU-Arab League relationship therefore bears strong potential and can potentially contribute to regional security, stability, and prosperity.

A second example concerns the EU’s trade policy. In trade relations, the Union has been struggling to encourage Arab partners to cooperate among each other. Ever since it proclaimed its ambitious 1995 Barcelona Declaration, the EU aims at gradually establishing a free trade area covering its Member States and the Southern Mediterranean. By 2010, the EU had largely fulfilled its part of the arrangement by concluding bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). The key issue, however, is that for the multi-State area to be completed, FTAs also need to be concluded among the Southern Mediterranean partners themselves. Yet, the only partners that have engaged in such projects so far are Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia. These countries concluded the Agadir Agreement, which entered into force in 2006, in accordance with the provisions of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade of 1994 (GATT) and the EU rules of origin. Despite the difficulties faced, the EU has assumed a role in enhancing intra-Arab trade facilitation. Through its neighbourhood policy, it has been financially supporting the consolidation of the Agadir Agreement. Two-and-a-half years since the outbreak of the Arab Spring, the EU continues its multilateral efforts. First, in its May 2012 Resolution on Trade for Change, the European Parliament recalled that it encourages the Treaty signatories to widen the membership of their trade relationship. Meanwhile, the European Commission has supported the Palestinian Authority’s request to accession. The request was accepted by the current signatory partners, who have started preparatory talks. Second, the Commission Implementing Decision on the Regional South Annual Action Programme of 2013 reaffirms the EU’s position as an important donor for the Agadir Technical Unit (ATU). The ATU was set up under the Agreement as an international body with the objective to facilitate regional economic integration. This being said, a recurring challenge for the EU is the development of comprehensive, multilateral policies while at the same time effectively differentiating its bilateral relations. Since 2011, bilateral approaches have (again) gained prominence in the EU’s trade relations with the MENA. The Commission started to conduct negotiations to establish deep and comprehensive free trade agreements (DCFTAs) with Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia that may lead to giving these countries a stake in the internal market.

The Arab uprisings have shaken up a large region and still continue to do so. But they have also brought about opportunities for the countries in North Africa and the Middle East to expand cooperation among each other, both politically and economically. At the same time, it becomes clear that the multilateral regional processes between States in transition still require follow-up. The EU is well-placed to offer its support. First, now seems to be the time to revitalise the promotion of economic integration between countries in the region. In particular, the EU should grasp the opportunity to push forward the inclusion of a larger number of Arab States in the Agadir Agreement. Second, it can be judged positively that the EU deepened its relations with the Arab League and envisions further cooperation. At least partly, this was the result of the Arab League being able to profile itself in the many difficult dossiers of the MENA. The EU may want to study how the League’s expertise may be further wielded in other important unlocked geopolitical situations – think of the Middle East Peace Process and Iran.

Jan Wouters is Jean Monnet Chair ad personam EU and Global Governance, full Professor of International Law and International Organizations, and Director, Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies – Institute for International Law, University of Leuven. Sanderijn Duquet is Research Fellow and PhD Candidate, Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies – Institute for International Law, University of Leuven. They are the authors of the paper ‘The Arab Uprisings and the European Union: In Search of a Comprehensive Strategy’, which is published in the Yearbook of European Law.

The Yearbook of European Law seeks to promote the dissemination of ideas and provide a forum for legal discourse in the wider area of European law. It is committed to the highest academic standards and to providing informative and critical analysis of topical issues accessible to all those interested in legal studies. It reflects diverse theoretical approaches towards the study of law. The Yearbook published contributions in the following broad areas: the law of the European Union, the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights, related aspects of international law, and comparative laws of Europe.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Flag of the Arab League [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In the wake of the uprisings appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishmentMiddle East food security after the Arab SpringGive peace a chance in Syria

Related StoriesAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishmentMiddle East food security after the Arab SpringGive peace a chance in Syria

Announcing the Place of the Year 2013 Longlist: Vote for your pick

Here at OUP, at the end of each year, we look back at the places around the globe (and beyond) which have been at the center of historic events. In conjunction with the publication of the Oxford Atlas of the World, 20th Edition, today we launch the Place Of The Year (POTY) 2013. Over the next two months, we’ll be highlighting the sites of this year’s important discoveries, conflicts, challenges and successes.

In honor of this 20th year of the Atlas, we’ve put together a longlist of 20 places around the world. You can vote for your picks using the voting buttons below – or, if we’ve missed your favorite place, you can nominate alternatives in the comments section (please include a brief description of the reasoning behind your pick). Think freely – nominees can be anything from your favorite brunch spot to a distant galaxy.

With your input, we’ll narrow the list down to a shortlist to be released on November 4th. Following another round of voting from the public, and input from our committee of geographers and experts, the Place of the Year will be announced on December 2nd. In the meantime, we’ll be posting here regularly with insights and explorations on geography, cartography, and the POTY contenders.

What should be Place of the Year 2013?

Moscow, RussiaSyriaTahrir Square, EgyptPyongyang, North KoreaCanada’s Tar SandsLake BaikalA Citibike StandRio de Janeiro, BrazilDemocratic Republic of the CongoColorado, USAThe NSA Data Center in UtahBoston, MABrooklyn, NYGreenland’s Grand CanyonDelhi, IndiaNorthern IrelandVenezuelaGrand Central TerminalThe United States Supreme CourtBenghazi, Libya

View Result

Total voters: 14Total votes: 16Moscow, Russia (0 votes, 0%)Syria (0 votes, 0%)Tahrir Square, Egypt (3 votes, 19%)Pyongyang, North Korea (0 votes, 0%)Canada’s Tar Sands (0 votes, 0%)Lake Baikal (0 votes, 0%)A Citibike Stand (1 votes, 6%)Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (0 votes, 0%)Democratic Republic of the Congo (0 votes, 0%)Colorado, USA (2 votes, 13%)The NSA Data Center in Utah (3 votes, 19%)Boston, MA (1 votes, 6%)Brooklyn, NY (1 votes, 6%)Greenland’s Grand Canyon (1 votes, 6%)Delhi, India (2 votes, 13%)Northern Ireland (2 votes, 13%)Venezuela (0 votes, 0%)Grand Central Terminal (0 votes, 0%)The United States Supreme Court (0 votes, 0%)Benghazi, Libya (0 votes, -1%)

Vote

The only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information, Oxford’s Atlas of the World is the most authoritative atlas on the market and the benchmark by which other atlases are measured. The milestone 20th edition includes new satellite images, new thematic maps, and a host of other features.

The post Announcing the Place of the Year 2013 Longlist: Vote for your pick appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPlace of the Year: Through the yearsAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishmentIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Related StoriesPlace of the Year: Through the yearsAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishmentIvor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

Dealing with digital death

Through the use of email, social media, and other online accounts, our lives and social interactions are increasingly mediated by digital service providers. As the volume of these interactions increases and displaces traditional forms of communication and commerce the question of what happens to those accounts, following the death of the user, takes on greater significance.

Should the relatives or heirs of a deceased Facebook user have the ‘right’ to access, take control of, or even delete the account? Some of you reading this will recoil in dread at such a thought, quickly remembering all of those digital indiscretions and private messages you would prefer to assign to oblivion but never got around to deleting. Other readers may remember a friend, no longer alive today, and will possibly turn to social media later to seek out a picture and recall a shared memory.

Of course while such personal and emotional interests play an important role in the emerging debate on how to handle the digital remains of deceased persons, other considerations, such as the possible economic value stored in accounts that ‘trade’ virtual property and currency or facilitate real world transactions, cannot be ignored. Neither should it be forgotten that, in time, access to these digital accounts will also be sought after by historians and researchers. Will these digital materials of history be locked behind passwords with access dependent on the goodwill of internet-based service providers?

Part of the answer to these questions is to be found in the terms of service (a legally binding contract) which most of us click ‘I agree to’, without ever reading. Many service providers have specific clauses or policies relating to the death of an account holder. For example, Google’s Inactive Account Manager permits subscribers of their services to make arrangements for the transfer, or deletion, of the data stored in their Google accounts following death. Unlike Google, no other major service provider gives users an in-service option of nominating heirs who can subsequently claim data from accounts. By signing up with Yahoo! you agree: “that your Yahoo! account is non-transferable and any rights to your Yahoo! ID or contents within your account terminate upon your death”.

Facebook ‘memorialize’ a deceased user’s account, which means the Facebook profile is frozen, limiting those who can see or locate it to confirmed ‘Facebook friends’ who can continue to share memories on the ‘memorialized’ timeline. Should a surviving family member wish to access the content in a Facebook account they must follow what Facebook describe as ‘a lengthy process’ which ultimately requires a court order.

You’re Dead, Your Data Isn’t: What Happens Now? Image by Ryan Robinson, ImageThink.net.

However, common to all service providers is a policy not to hand-over a password for a decedent’s account. To overcome these blunt contractual and technical defaults, digital estate planning services have emerged. Despite the grand title, these are often no more than password sharing schemes. LegacyLocker.com and SecureSafe offer further services but ultimately depend on a user maintaining a list of accounts and associated passwords. API based services such as Perpetu are also emerging.

Of course a user may plan ahead and share their password with family and friends, while alive, or leave passwords in a will. Unfortunately sharing passwords and permitting others to use your account is very often prohibited by the terms of service agreement. Furthermore, accessing or modifying content in a deceased person’s account without the knowledge of the service provider may constitute a criminal offence in some jurisdictions.

Surviving families have also turned to the courts, but with mixed results. The Ellsworth family, whose son Justin was killed in Iraq in 2004, won a probate order against Yahoo! to obtain copies of the contents of an e-mail account. However, a UK family was refused an order, by a California court, to compel Facebook to provide the contents of their deceased daughter’s account, due to a US federal law enacted to protect privacy in electronic communications.

A number of US states (Connecticut, Idaho, Indiana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and Virginia) have laws incorporating certain online accounts or information into the probate process. However, little consistency exists in the scope of these laws or the powers they create. Furthermore, these state laws may be in conflict with US federal laws. In an attempt to address these matters, the Uniform Law Commission in the US are currently drafting a Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act.

Empowering users to make active choices in relation to their digital remains should be a fundamental element of any solution. However, the creation by legislators of a default position where digital remains are automatically transmissible at death, unless a valid will provides otherwise, may not be the best solution. Does each new account require an amendment to a will? Are children, who in many jurisdictions cannot create a valid will, to be denied post-mortem privacy in relation to their accounts?

A creative solution is required that provides for individual choice on whether these accounts and contents are to re-used, deleted or distributed, following death. However, reconciling the business needs of service providers with the sentimental and economic interests of surviving family and friends, and the public interests involved in future access to these materials of history, for heritage institutions and researchers, will not be easy.

The policy debate in relation to your digital legacy is only beginning.

Damien McCallig is a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Law, National University of Ireland, Galway and an Irish Research Council postgraduate scholar. This blog post introduces the topic of digital legacy. A deeper analysis of the legal and policy issues related to this topic can be found in Damien’s article ‘Facebook after death: an evolving policy in a social network’ in the International Journal of Law and Information Technology and available to read for free for a limited time. Follow Damien on Twitter.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Dealing with digital death appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe wondrous world of the UW Digital CollectionsWorld Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseasesAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

Related StoriesThe wondrous world of the UW Digital CollectionsWorld Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseasesAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

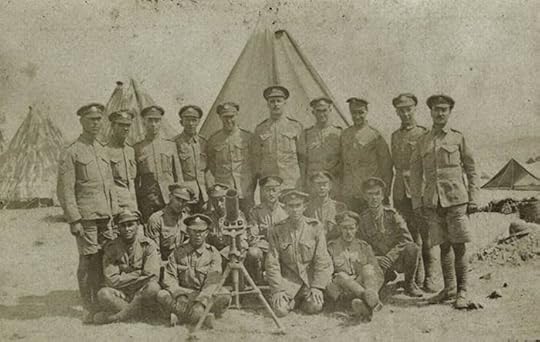

Ivor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War

One of the anthologist’s greatest pleasures comes from discovering previously unknown pieces to jostle with the familiar classics. Editing The Poetry of the First World War, I knew that I should need to accommodate ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, ‘The Soldier’, and ‘For the Fallen’. Whatever their qualities, these have become so inextricably part of our understanding that to omit them would be perverse. Yet I wanted to believe that other poems, no less worthy, have been unfairly neglected, either because they tell the kinds of truths which we are unwilling to hear (such as that war can occasionally be enjoyable or exhilarating), or because they have endured the simple bad luck of never having been brought to public attention. This was, after all, a literary War, and poetry was produced in such quantities that the good sometimes sank with the mediocre and the inept.

No war poet better illustrates this fact than Ivor Gurney (1890-1937). Gurney fought in the War with the Gloucesters. He was shot, he was gassed, he was invalidated out, and he spent the last fifteen years of his life from 1922 in the City of London asylum at Dartford, suffering from acute schizophrenia. Gurney was an accomplished composer before he was ever a poet, and his music is regularly performed. He started writing poetry during the War, publishing Severn & Somme in 1917 and War’s Embers in 1919. These were perfectly good books, but with few exceptions they demonstrated no unusual talent. Only after the War, and particularly in the early asylum years, did Gurney become a great poet. Writing with unprecedented intensity—sometimes producing the equivalent of four books of poetry in a single month—Gurney returned to war experiences as a way of escaping the misery of his incarceration. Idiosyncratic and often gauche, these poems were nevertheless stamped with the peculiarity of genius. But publishers showed no interest. Gurney wrote over a thousand poems between 1922 and 1927, the vast majority of which remain unpublished to this day.

Stokes trench mortar with team. Group of soldiers posing with a trench mortar, Salonika, taken by Capt Philip Rolls Asprey, whilst serving with 2nd Bn The Buffs (East Kent Regiment), nd, 1916 © National Army Museum.

I have included several new poems by Gurney in the anthology. One of my favourites, which he wrote in 1925, has languished amongst his papers at the Gloucestershire Archives until now:

The Stokes Gunners

When Fritz and we were nearly on friendly terms—

Of mornings, furtively, (O moral insects, O worms!)

A group of khaki people would saunter into

Our sector and plant a stove-pipe directed on to

Fritz trenches, insert black things, shaped like Ticklers jams—

The stove pipe hissed a hundred times and one might count to

A hundred damned unexpected explosions,

Which was all very well, but the group having finished performance

And hissed and whistled, would take their contrivance down to

Head quarters to report damage, and hand in forms

While the Gloucesters who desired peace or desired battle

Were left to pay the piper—Cursing Stokes to Hell, Montreal and Seattle.

The Stokes Mortar was the latest thing in military technology. Introduced during the second half of the War, it had the great virtue of being portable—a modestly-sized artillery gun which could fire more than twenty rounds per minute. Gurney’s hostility to its arrival in his part of the line can best be explained by his fellow poet Charles Sorley’s comment several years earlier: ‘For either side to bomb the other would be a useless violation of the unwritten laws that govern the relations of combatants permanently within a hundred yards of distance of each other, who have found out that to provide discomfort for the other is but a roundabout way of providing it for themselves’. Small wonder that Gurney should denounce as ‘moral insects’ those form-filling jobsworths who bring down the enemy’s wrath onto the Gloucesters’ heads.

In war anthologies, we have heard little of this humour. Gurney’s is not the voice of heroic derring-do, nor of the officer pleading the sufferings of his men or denouncing High Command as incompetent or callous. Gurney offers us the common private who wants to be no more courageous than strictly necessary in achieving his ambition to survive the War. The poem befits a remark which Gurney made of his fellow Gloucesters when he reported that they sang ‘I Want to Go Home’ while under heavy artillery bombardment. ‘It is not a brave song’, he acknowledged, ‘but brave men sing it’.

Tim Kendall has taught at the universities of Oxford, Newcastle, and Bristol before becoming Professor and Head of English at the University of Exeter. His new book is Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology. His other publications include Modern English War Poetry (OUP, 2006), and The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry (ed.) (OUP, 2007), and he is writing the VSI on War Poetry (forthcoming, 2014). He is also co-editor of the Complete Literary Works of Ivor Gurney, (forthcoming, OUP).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Stokes trench mortar with team. Group of soldiers posing with a trench mortar, Salonika, taken by Capt Philip Rolls Asprey, whilst serving with 2nd Bn The Buffs (East Kent Regiment), nd, 1916 © National Army Museum.

The post Ivor Gurney and the poetry of the First World War appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesShakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remainsMary Hays and the “triumph of affection”Edmund Gosse: nonconformist?

Related StoriesShakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remainsMary Hays and the “triumph of affection”Edmund Gosse: nonconformist?

October 13, 2013

On shutdown politics: why it is not the Constitution’s fault

It has become a routine recourse, when examining American politics, for modern commentators to blame the Constitution for the failures of government. We are told that the separation of powers encourages gridlock, and parties pull together what the Constitution pulls asunder. When considering the mess we are in today that is the government shutdown, the truth is closer to the other way round. Parties are the problem, not the solution.

Let’s get down to the nitty gritty, and see if it really is the Constitution that is at fault. Why exactly is Speaker John Boehner refusing to bring a vote to the floor of the House to re-open the federal government? We are told, it is the Hestert Rule, named after Dennis Hastert, which instruct Speakers not to bring a bill to the floor unless it commands the approval of a majority of the majority party in the House.

Well and good, until we consider this indisputable fact: nowhere in the Constitution do we have anything remotely close to codifying the Hestert Rule. The Hestert rule is a creature of modern partisanship; it is named after one man, indeed, it has been denounced by the same man whose name identifies the eponymous rule. Even if the idea that the Speaker should defer to the “majority of the majority” makes sense, it is not to be found in the Constitution.

US Constitution. Public domain.

More importantly, the Tea Party caucus is not a majority of the majority. It is a faction, the vilest enemy to republicanism according to the framers of the Constitution. Or, put another way, the Constitution was expressly created to control faction (by creating a republic so large that no one faction would be able to, at least before the invention of the political party, dominate). Madison could not have been clearer in his opprobrium of faction:

“Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction … By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” (Federalist 10)

So when President Barack Obama proclaimed that “one faction of one party in one house of Congress in one branch of government doesn’t get to shut down the entire government just to refight the results of an election,” he was on very firm constitutional ground, and pointedly — I think also consciously — using “faction” exactly as the framers intended it in the eighteenth-century sense. Today’s self-proclaimed “originalists” are picking and choosing what part of history to affirm. “Faction” and “partisanship” were foul words to the framers, for precisely the reasons we are experiencing today. President Obama has no obligation, under the original meaning and intent of the Constitution, to negotiate with a faction; indeed he in on good ground to try to rein it in.

Looking ahead, as Washington veers toward another self-inflicted crisis, raising the debt ceiling, it is useful again, to return to original principles. We are told that the framers of the Constitution created a limited government, and perhaps Senator Ted Cruz et al are right to use Congress’s power of the purse to limit the excesses of government spending. Wrong again. The Constitution was written to provide a more muscular government to pay off the revolutionary war debt. In fact, paying back what the nation owed was at the heart of Alexander Hamilton’s case for the Constitution:

“I believe it may be regarded as a position warranted by the history of mankind, that, in the usual progress of things, the necessities of a nation, in every stage of its existence, will be found at least equal to its resources … A country so little opulent as ours must feel this necessity in a much stronger degree. But who would lend to a government that prefaced its overtures for borrowing by an act which demonstrated that no reliance could be placed on the steadiness of its measures for paying?” (Federalist 30)

There is no way that one can read these words and conclude that the Founders would have been ok with a US government default or any tactic that suggested it as a possibility.

So it is not the Constitution that is at fault. It is faction, injected like a toxin into the Constitution, that has caused the separation of powers to go awry. And if so, the short-term solution for shutdown politics is to call faction what it is. Errant and arrogant members of Congress need to be reminded or educated that while they represent their constituents, some of whom no doubt want a stay on Obamacare, each member of Congress also belongs to a chamber of the United States and it is always the national majority (across the nation) that counts more than a factional majority (in a district). The long-term solution is as simple as it is admittedly inconceivable: if we want to kill faction, we must kill its grandfather and father — the political party and the system of primaries that sprung up in the middle of the twentieth century that has created two generations of extreme ideologues and the era of gridlock. To do that requires neither a dismissal nor a cynical revision of original meaning, but an affirmation of its deepest philosophy — the hope of “a more perfect Union,” sans faction, sans party.

Elvin Lim is Associate Professor of Government at Wesleyan University and author of The Anti-Intellectual Presidency, which draws on interviews with more than 40 presidential speechwriters to investigate this relentless qualitative decline, over the course of 200 years, in our presidents’ ability to communicate with the public. He also blogs at www.elvinlim.com and his column on politics appears on the OUPblog regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post On shutdown politics: why it is not the Constitution’s fault appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesAnother kind of government shutdownAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishmentRiding the tails of the pink ribbon

Related StoriesAnother kind of government shutdownAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishmentRiding the tails of the pink ribbon

Mary Hays and the “triumph of affection”

By Eleanor Ty

Pain of Unrequited Love is a blog dedicated to “probably the worst feeling in the world.” It contains short posts in the form of text and image, poetry, prose, drawings, cartoons, photos, animated GIFS, and links to pop song videos, all describing feelings of rejection, hurt, and loneliness. Posts relate stories of falling in love, intense passion, and then loss. To date, the blog boasts of visitors from 156 countries.

One might think that this desire for self-exhibition is the product of the selfie, Facebook, and Instagram age of today. The “I” generation, which grew up with pods, pads, and cellphones, seems to have little or no sense of privacy, and happily proclaim and update their “relationship status” to all their five hundred and ten friends (the average number of friends on Facebook for 18-24 year-olds). But in the late eighteenth-century, novelist, essayist and Dissenter, Mary Hays, born on 13th October 1760, also broke the boundaries between the personal the public by gathering the love letters she had written to a man she adored but who apparently did not reciprocate her feelings, and publishing them as an epistolary novel. In doing so, she caught the attention and aroused the ire of minor British poet Charles Lloyd (friend of Samuel Coleridge), novelist Elizabeth Hamilton (Scottish novelist and educator), and Robert Southey.

In the early 1790s, Mary Hays was a rising writer who had published an Oriental tale, an essay on the usefulness of public worship, and, with her sister, produced a collection of essays on miscellaneous topics: romances, friendships, and improvements to female education. She admired and had befriended radicals Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, and was introduced to the circle of London intellectuals in the 1790s. William Frend, a social reformer, writer, and Unitarian minister, had corresponded with her because he had read her works, but he did not return her passionate feelings for him. Believing that what she felt for him was based on reason and affection, Hays pursued Frend with letters, repeatedly presenting justifications for her love:

“An attachment sanctioned by nature, reason, and virtue, ennobles the mind capable of conceiving and cherishing it: of such an attachment a corrupt heart is utterly incapable” (Emma Courtney, 81-82).

She cannot understand how he cannot return her feelings, offering good examples of their compatibility:

“Our principles are in unison, our tastes and habits not dissimilar, our knowledge of, and confidence in, each other’s virtues is reciprocal, tried and established – our ages, personal accomplishments, and mental acquirements do not materially differ…. How, then, can I believe it compatible with the nature of mind, that so many strong efforts, and reiterated impressions, can have produced no effect upon yours: Is your heart constituted differently from every other human heart?” (Emma Courtney 121-122).

Title page from Mary Hays’s Memoirs of Emma Courtney, 1796

Unsuccessful in her quest, she was advised by Godwin to turn her unhappy story into fiction, resulting in her first novel, Memoirs of Emma Courtney (1796). Like the bloggers and contributors to “Unrequited Love” on Tumblir who post to share their pain with a community of friends, Hays believed that her feelings would not only be understood, but that they would teach others a lesson in what not to do. Her audacious Emma was to “operate as a warning, rather than as an example” to her readers (Preface to Emma Courtney). For Hays, the emphasis on self-examination and individual agency was grounded in her Dissenting religious beliefs and the Enlightenment conviction in the power of rational thought to create social change. She shared a vision of moral reform with other popular writers of the age, such as Amelia Opie and Maria Edgeworth.However, her directness was perceived as an act of impropriety by her contemporaries who satirized the candour of Emma, and by association, Hays herself. In her novel, Memoirs of Modern Philosophers (1800), Elizabeth Hamilton created a character, humorously called “Bridgetina Botherim,” who is associated with the dangerous “new” philosophy imported from revolutionary France. As Claire Grogan notes, this new philosophy encourages “selfish, romantically self-indulgent, and obsessive behaviour” (Eighteenth-Century Fiction 2006). Emma’s attempts at rationalizing her affections were caricatured and ridiculed by Hamilton. Bridgetina Botherim thinks, “Why should he not love me? What reason can he give? Do you think I have not investigated the subject?” (Modern Philosophers 179). Hays’s ideas about the power of feelings, about the noble link between reason and affection were too advanced for her contemporaries. Memoirs of Emma Courtney remains a fascinating blend of feminist philosophy, melodrama, depicting a very un-Austen-like heroine who challenges reader’s expectations of how a proper lady should behave and what she should say.

Eleanor Ty is a Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University. She works in two areas: on Asian North American Literature and Film and on Eighteenth Century British Literature. For Oxford World’s Classics, she has edited Memoirs of Emma Courtney by Mary Hays.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Title page from Mary Hays’s Memoirs of Emma Courtney, 1796 [public domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Mary Hays and the “triumph of affection” appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesÉmile Zola and the integrity of representationEdmund Gosse: nonconformist?Why is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

Related StoriesÉmile Zola and the integrity of representationEdmund Gosse: nonconformist?Why is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers