Oxford University Press's Blog, page 894

October 12, 2013

Another kind of government shutdown

Since the US government shutdown last week, lawmakers and public commenters have been worrying about the massive costs to American taxpayers and the US economy. Previous government shutdowns in 1995 and 1996 cost us an estimated $2.1 billion in 2013 dollars.

But what people aren’t talking about is the other kind of shutdown that the government impasse reveals. This other kind started long before the government shutdown, and it comes with far greater costs than just money. It’s a shutdown of diverse views, intelligent discussion, and constructive debate. It’s a shutdown of democratic political communication. Politics isn’t about communication anymore. It’s about branding.

Last week, the Adorable Care Act got underway. That’s right, Adorable Care. According to Politico, a former Obama staff member created a Tumblr page featuring photos of cute cats, headlined with pro-Obamacare messages and tagged with the dot gov healthcare URL. It quickly gained traction among the young adult crowd. Rachel Maddow and Stephen Colbert gave the Adorable Care Act campaign a shout-out on their shows. As of Sunday 6 October 2013, the Adorable Care Twitter account had 2,648 followers. Although the White House denied direct involvement in the Obamacare rebranding campaign, White House press secretary Jay Carney told Politico that he got the point: “Everybody loves cute animals.”

Everybody loves cute animals. Source: Adorable Care Act Tumblr.

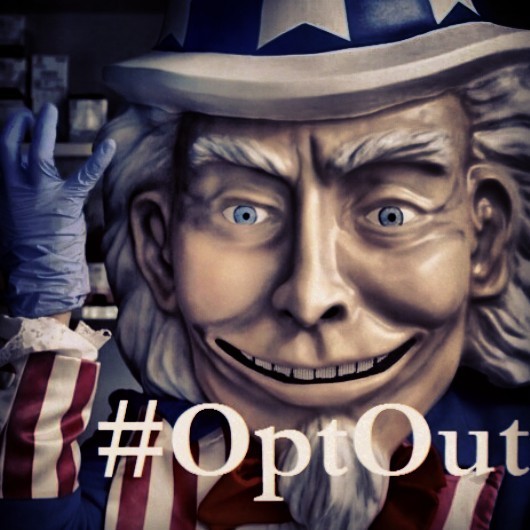

Another branding campaign made headlines last week. Generation Opportunity promotes itself as a youth advocacy group whose mission is to persuade young adults to opt out of Obamacare. Armed with $5 million dollars from the Freedom Partners Chamber of Commerce (associated with the billionaire Koch brothers), the Generation Opportunity campaign includes social media signups, college campus events, and crass Internet commercials (one of them depicts a ghoulish Uncle Sam character popping up between a woman’s legs during a gynecological exam). It didn’t take long for journalists to discover that Generation Opportunity’s core message — that it’s cheaper for young people to opt out of Obamacare — was baseless.

“Creepy Uncle Sam” wants you to opt out of Obamacare. Source: Generation Opportunity Press Release.

But the lack of factual evidence is clearly not the point. What political branding campaigns reveal all too clearly is that it’s not about the message. It’s about narrowing the available channels for communication into two starkly opposing sides — left and right, liberal and conservative. There’s no middle ground, no attempt at reaching consensus or even starting a conversation. Branding is about claiming a meme, creating a mindset, and controlling the media.

Advertising and politics have long been intertwined in the national conversation. Back in 2001, former ad executive Charlotte Beers was appointed by George W. Bush as US Under-Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. To many, the appointment represented a doomed attempt to reassert America’s values of freedom and democracy through a fundamentally incompatible means of mass communication: advertising. New York Times columnist Frank Rich was despondent, writing that Beers was chosen “not for her expertise in policy or politics but for her salesmanship on behalf of domestic products like Head & Shoulders shampoo. If we can’t effectively fight anthrax, I guess it’s reassuring to know we can always win the war on dandruff.” Historians like T.J. Jackson Lears have documented the marriage of advertising and politics much earlier, linking it to America’s propaganda needs in World War I.

Branding and advertising were invented to tell stories. Promotional industries exist to create emotional connections between the things we buy and the values we hold. When politics gets on the “brandwagon,” what we get are stories designed to make us buy into ideas without understanding the political consequences. Political deliberation is poorly served by these simplistic fables. We don’t need more distraction in the form of self-interested rebranding campaigns. We need informed debate to help us make smart decisions about the consequences of politics and policy.

Melissa Aronczyk is Assistant Professor in the Department of Journalism and Media Studies at Rutgers University. She is the author of Branding the Nation: The Global Business of National Identity.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Another kind of government shutdown appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRiding the tails of the pink ribbonFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

Related StoriesRiding the tails of the pink ribbonFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldAccelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

World Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseases

World Arthritis Day is celebrated each year on the 12th of October. It was first established in 1996 by Arthritis and Rheumatism International with the aim to raise awareness of issues affecting people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases within the medical community, as well as the general population. Over 120 million people in Europe are affected by rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (EULAR), a huge number of people, with one in five Europeans under long-term treatment for rheumatism or arthritis (European Opinion Research Group EEIG).

A recent analysis of a US registry investigated patient improvement after hip replacement, when a hip joint is replaced surgically with a prosthetic implant. It is most commonly used for patients with osteoarthritis where their joints have failed and the patient suffers high levels of pain and low mobility. As with all surgery, there are a number of potential risks associated, including infection and pain, and there is a wide variation in patient satisfaction after the procedure. This treatment has come a long way from when it was first performed in 1960. Now, most people can resume normal activity six to eight weeks after surgery, but there are limitations, which are not often understood by patients when they choose to have the procedure. As younger patients are increasingly having this surgery, the management of their expectations is becoming more important. In terms of surgery, the bottom line a patient may want to know is how the surgery will affect their quality of life and the pain involved. Will the benefits outweigh the limitations?

This study had an additional aim to provide the data in a format that can be easily interpreted by both patients and policymakers, which was directly relevant to their concerns. The researchers recorded patient improvements in a number of daily activities, such as climbing stairs and getting in and out of cars, and followed up patients at two and five years after surgery. This data will hopefully be a good source of information for doctors, helping them better inform patients before they have the elective surgery. This should enable the patient to better understand the benefits and limitations of the procedure, so they can make a more informed decision with realistic expectations of the outcomes and long-term prognosis.

Scientific journals are crucial in expanding knowledge and improving treatments. However, the highly technical and scientific language used in these publications can be impenetrable to the layperson, who may just want to understand how the research relates directly to their disease. Science is primarily written for other scientific experts and only rarely directed at patients. Paradoxically, expert scientists and doctors are not often the best at communicating research to lay people — yet at the same time, they are the most trusted source of information for patients. At Rheumatology we would like to help address the gap between patient and expert understanding to aid patients in setting realistic goals for improvement.

Professor Robert J Moots is the Editor of the international peer review journal Rheumatology that publishes papers on range of rheumatological conditions, musculoskeletal medicine, surgery and translational research. He is a professor of rheumatology at the University of Liverpool, UK, and consultant rheumatologist at University Hospital, Aintree, Liverpool. His research interests lie in clinical and basic science aspects of inflammatory rheumatic diseases, from laboratory to bedside.

To mark World Arthritis day Rheumatology is highlighting “Patient-level clinically meaningful improvements in activities of daily living and pain after total hip arthroplasty: data from a large US institutional registry” by Jasvinder A. Singh and David G. Lewallen (available to read for free for a limited time). The paper evaluated the reduction of pain after a total hip arthroplasty (THA) operation (hip replacement), as well as the impact on improving patients’ activities of daily living.

Rheumatology is an international peer review journal publishing the highest quality scientific and clinical papers. The scope of Rheumatology includes a range of rheumatological conditions, musculoskeletal medicine, surgery and translational research. Rheumatology is the official journal of the British Society for Rheumatology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Male Doctor Examining Male senior Patient With Hip Pain. © monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.

The post World Arthritis Day – promoting awareness of rheumatic diseases appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patientThe demographic landscape, part II: The bad newsThe demographic landscape, part I: the good news

Related StoriesFine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patientThe demographic landscape, part II: The bad newsThe demographic landscape, part I: the good news

October 11, 2013

The wondrous world of the UW Digital Collections

A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure of attending a presentation on archiving commemorative African fabrics, through the course of which I learned about the University of Wisconsin’s Digital Collections Center. As a historian-in-training and digital archive enthusiast, I became immediately intrigued by all the resources and projects described by Melissa McLimans, a digital librarian who works with the Center and helped digitally archive the fabric. After the talk, I decided to reach out to Melissa via e-mail to learn more about the UW Digital Collections Center. I also spoke with the Center’s resident audio expert, Steven Dast. I do work for the Oral History Review, after all.

First thing first, how did the UW Digital Collections begin?

Steven: I started working at Memorial Library some 24 years ago as a student camera operator in the microfilm lab. After graduation, I continued working there in a combination of Library Services Assistant and Microfilm Technician positions. When the Library acquired its first digital camera in 1995, it was housed in the microfilm lab and we used it for a variety of early experimental digital projects. Then, in the run up to the ‘98 Wisconsin sesquicentennial celebration, the library was awarded a grant to create a significant online collection of readings and images from Wisconsin history, using material from the Library, the UW Archives and Wisconsin Historical Society. I was hired to manage that project, other projects followed, and the Digital Collections Center kind of grew up around me.

And what does Digital Collections look like now?

Melissa: Since its official founding in early 2000, the UW Digital Collections Center has continued to work collaboratively with UW System faculty, staff, and librarians to create and provide access to digital resources that support the teaching and research needs of the UW community, uniquely document the university and State of Wisconsin, and provide access to rare or fragile items of broad research value. The Center has also partnered with cultural heritage institutions and public libraries throughout Wisconsin to create digital resources.

Resources within the collections are free and publicly accessible online. They are loosely organized into collections that span a range of subjects including art, ecology, literature, history, music, natural resources, science, social sciences, the State of Wisconsin, and the University of Wisconsin. Digital resources include text-based materials such as books, journal series, and manuscript collections, photographic images, slides, maps, prints, posters, audio, and video.

In working with all the sources you describe, our managing editor and the UW’s Oral Historian Troy Reeves told me you handle a number of oral histories. Could you talk a bit about that? Are there any collections our readers might enjoy?

In working with all the sources you describe, our managing editor and the UW’s Oral Historian Troy Reeves told me you handle a number of oral histories. Could you talk a bit about that? Are there any collections our readers might enjoy?

Melissa: The UW Digital Collections has several collections that are exclusively or include significant numbers of oral histories. We do work with Troy and the UW Archives team to make available online interviews with campus administrators, staff, and students as well as faculty in the UW-Madison Campus Voices collection. The interviews have been submitted thematically to highlight important eras, events and people on the UW-Madison campus. Another particularly compelling oral history collection can be found in the World War II Veterans of Mount Horeb collection. Public librarian (and past UWDCC staff member) Jessica Williams sought out the World War II veterans in her community and interviewed them about their time spent in and out of service.

Steven: Actually, my first direct work with audio came when we worked with the Area Research Center (ARC) in Green Bay in about 2001 to digitize a series of interviews that had been done in the mid-1970′s to document the history of Belgian immigrants to that area. And the following year we embarked on a major project to digitize Professor Harold Scheub’s field recordings of South African storytellers, about 1700 hours of audio recorded from 1967 to 1976. The Scheub project is large enough that, while we’ve digitized all of the recordings, we’ve only added about a third of it to the online collection.

So, the Center is clearly comfortable handling oral histories. Are there any difficulties unique to audio sources that you face when working with these and other audio-heavy collections?

Melissa: Well, the two examples I referred to earlier have different levels of description, which is one of the great difficulties for digital libraries and I would imagine oral historians. In some cases there are full transcripts, and in others, only time codes. Either of these scenarios can be dealt with, but it is extremely helpful when the descriptions or metadata have been applied consistently to the oral history recordings. Consistency means we can automate some of the work, making it quicker, easier and ultimately more cost effective to add to the digital collections.

Steven: The biggest difficulty I face with audio, and oral histories in particular, has to do with providing useful interfaces. It’s rarely a matter of simply providing an audio file to download or play online. Oral histories come with topical indexes or full transcripts or both, and ideally you want to be able to display those alongside the audio and have there be a fluid mechanism for moving between them. We don’t generally have the technology resources to custom build a system just for delivering oral histories, so we have to try and fit the content into systems that were designed for things more like image collections and scanned books.

Steven, as audio expert, do you have any advice for those working with audio files?

Steven: Academics who have audio in analog formats should be thinking seriously about getting it converted to digital. When converting, it’s best to stick with uncompressed formats, so .wav rather than .mp3. Compression introduces a small amount of distortion which, although it may not be audible, may become a problem for future uses. Fortunately, storage space is much more available and inexpensive than just a few years ago, so storing uncompressed audio is not a great burden.

Beyond that, good archiving practices for audio are largely the same as good archiving practices for any other digital file. Keep good backups. Record good metadata and save it with your files. Keep your final versions in a separate directory or otherwise isolated from intermediate versions, excerpts, and other temporary files. If you do store or access your files through some kind of indexing or content management software, make sure there’s a way to extract the files and the metadata. Ideally, these will be stored as plain files on your hard drive somewhere, so you can always get to them even if the management software fails.

***

So, there you have it, folks. While I know most of you are busy running around the 2013 OHA Annual Meeting, consider taking a break to check out the UW Digital Collections Center. Not only does it house a number of fantastic sources (many more in addition to the ones Melissa and Steve mentioned) it’s also an excellent example of a large, well-organized multimedia digital archive. See, it can be done!

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/ media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, add them to your circles on Google Plus, follow them on Tumblr, listen to them on Soundcloud, or follow the latest OUPblog posts via email or RSS to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: dictaphone isolated on white background, selective focus on nearest part. © Kuzma via iStockphoto.

The post The wondrous world of the UW Digital Collections appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories2013 OHA will be much more than OKCSI: Oral HistoryFall cleaning with OHR

Related Stories2013 OHA will be much more than OKCSI: Oral HistoryFall cleaning with OHR

Accelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment

For more than a decade, 10 October has been the World Day Against the Death Penalty. It is an important activity of the global movement against capital punishment. Amnesty International has been campaigning on the issue since the 1970s. But since the beginning of the century, the movement has grown. There have been regular world congresses of abolitionists. A prestigious commission of international personalities intervenes regularly through statements and declarations. In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution calling for a global moratorium on executions. Since then, similar resolutions have been adopted at two-year intervals, with increased majorities each time.

Almost forty years ago, in his first periodic reports on the death penalty, the United Nations Secretary-General said it was not possible to identify trends with respect to capital punishment. At the time, a very substantial majority of states imposed the death penalty. Less than ten had done away with capital punishment completely. So as to boost the numbers of abolitionist states, the Secretary-General included those that no longer executed for ‘ordinary crimes’, recognising the fact that many countries insisted on retaining the practice in wartime and emergency situations. Even the Council of Europe, in 1983, had to satisfy itself with a protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights that proclaimed abolition of capital punishment but only in peacetime.

Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. CC-BY-SA. Photo by Trounce/Wikimedia Commons.

How things have changed. Even those states that still retain the death penalty would not dare to deny that they are bucking a powerful global trend. Indeed, since about 1980, an average of three countries every single year has joined the abolitionist camp. From fewer than 30 abolitionist states in 1973, the number now exceeds 150.

Many states abolish capital punishment through legislative reform, sometimes even accompanied by constitutional amendment. But a significant number simply stop carrying out executions either quietly or through an officially-proclaimed moratorium. When they go ten years without a hanging, the United Nations deems them to be abolitionist in practice. The 2009 report of the Secretary-General showed that this is methodologically very solid as a measure of abolitionist commitment. States that have not executed convicts for a decade almost never return to the practice. The same can be said of abolition in law, which has only been reversed once in recent decades in the Philippines, and then only temporarily. Abolition is essentially a one-way street.

The perhaps inevitable focus on tallies of countries that are abolitionist or retentionist only provides a partial insight into the dynamics of this process. Just as significant is the fact that most states in the increasingly small category of those that continue to execute actually do so less and less. Of the forty-odd death penalty countries that still remain, only about twenty conduct an execution in any given year. The United States and China are among the small group that conduct executions every year. Both of these countries have seen the number of persons executed each year drop to about one-third of the number only a decade ago. Whether measurements focus on the number of abolitionist states or the number of executions in retentionist states, the statistics tell the same story. Not only does the trend continue unabated, it actually seems to be accelerating.

Several regions of the world are now essentially free of capital punishment. In recent years, the only executions in the western hemisphere have been conducted in the United States, mostly in former slave states with justice systems that still reflect their brutal and racist ancestry. Belarus is the only European nation to carry out executions but it conducts barely two or three each year. Only a few African states, essentially concentrated in the northeast corner of the continent, regularly execute people. None of the states of the ‘Arab spring’ — Egypt, Libya and Tunisia — reports an execution since 2011, according to Amnesty International’s annual booklet on the subject.

Thus, the death penalty is today mainly an Asian phenomenon. But Asia is far from homogeneous. Much of Southeast and Southern Asia, including Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Nepal and Sri Lanka, has stopped executions. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh have a very small number of executions. In China, the numbers are still appallingly huge, but they are surely declining at a rapid rate. Chinese scholars and legal practitioners insist that the country’s goal is abolition.

The darkest spots on the Asian continent are Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and a few of their smaller neighbours. They remain profoundly attached to capital punishment, offering unconvincing references to scripture as a justification. But in those countries, capital punishment is mainly used for drug traffickers, a matter on which the religious texts do not take a position. Capital punishment continues not because the political leaders are pious and devout but rather because they are autocratic and repressive.

In his influential book The Better Angels of our Nature, Stephen Pinker situates the decline in the use of capital punishment within the broader theme of a general reduction of institutionalized violence. Pinker’s compelling thesis is that the world is increasingly less violent, as trends in everything from judicial punishment to armed conflict and ordinary crime demonstrate. His argument provokes another observation. The abolition of capital punishment has been central to the modern human rights movement. Simple statistics tell us that there is a great deal less capital punishment than in the past. The human rights movement is entitled to some of the credit for this. Unlike many other issues, such as racial or gender discrimination or the practice of torture, capital punishment easily lends itself to quantitative analysis. But is this also a useful metric that signals a broader and more general trend to improvement in human rights? The declining numbers of executions in the modern world are thus an indicator of profound improvements in other areas too, whose measurement is less straightforward. In other words, 10 October is an important date for more reasons than one.

William Schabas is Professor of international law at Middlesex University in London and Professor of international criminal law and human rights at Leiden University. He is the author of the major academic study on the death penalty and international law. In 2009, Professor Schabas prepared the United Nations Secretary-General’s five-year report on capital punishment. His latest book with Oxford University Press is entitled Unimaginable Atrocities.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Accelerating world trend to abolish capital punishment appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRiding the tails of the pink ribbonAn interludeFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the world

Related StoriesRiding the tails of the pink ribbonAn interludeFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the world

Management for humans

By John Hendry

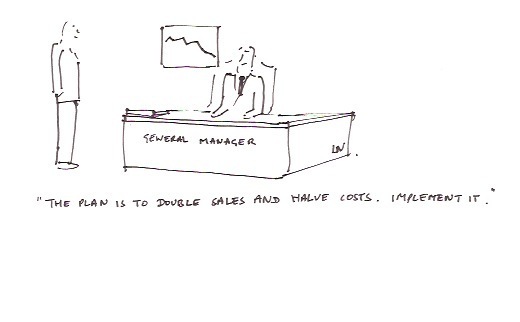

The word ‘management’ derives from the sixteenth century Italian maneggiare, to handle or control a horse. The application has been extended over the centuries from horses to weapons, boats, sportspeople and nowadays to people and affairs quite generally, but the connotation of control remains. Indeed, in management theory, as we teach it in business schools, control is a central preoccupation. Theories differ in the assumptions they make about human motivation and behaviour, and in the organizational structures, incentives, reward systems and managerial techniques they prescribe. Some treat working people as willing or unwilling cogs in a machine, to be disciplined so as to maximize the efficiency of the machine. Others treat them as enterprising but self-interested individuals, to be manipulated through incentives to do what is required. Still others see them as cooperative problem-solvers, to be harnessed to an organization’s culture and goals. But all seek to control them in one way or another so as to maximize their output or efficiency. The words discipline, manipulate and harness could all be applied equally well to that sixteenth century horse.

In real life, of course, people are not horses, and while most managers would like to be in control they rarely are. Most large organizations employ structures and techniques based on management theories, and use these to exert some kind of control. Many small organizations still operate by more traditional methods of control: do as you’re told or else. But for most managers, in whatever kind of organization, management is as much about coping, and helping others to cope, as it is about controlling: “How are you doing? I’m managing.”

We wouldn’t give somebody the job title of “coper”. it doesn’t sound nearly authoritative enough. But we don’t generally give them the title of ‘controller’ either. We know that managers often aren’t in control, and to describe them as controllers would only invite sarcasm. (Sir Topham Hatt, the benign “fat controller” of the Thomas the Tank Engine stories, acquired his job title on the nationalization of the railways in 1948, when obesity was not considered a problem and war-time notions of what could be achieved by centralized planning and direction still prevailed!) But as any parent will tell you, coping is very important. The central challenge for managers, as for parents, is less about controlling and more about coping when, through no fault of one’s own, things begin to get out of control.

We wouldn’t give somebody the job title of “coper”. it doesn’t sound nearly authoritative enough. But we don’t generally give them the title of ‘controller’ either. We know that managers often aren’t in control, and to describe them as controllers would only invite sarcasm. (Sir Topham Hatt, the benign “fat controller” of the Thomas the Tank Engine stories, acquired his job title on the nationalization of the railways in 1948, when obesity was not considered a problem and war-time notions of what could be achieved by centralized planning and direction still prevailed!) But as any parent will tell you, coping is very important. The central challenge for managers, as for parents, is less about controlling and more about coping when, through no fault of one’s own, things begin to get out of control.

Whatever kind of business or service you are engaged in, the most challenging aspect of management is trouble-shooting, or responding to what the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan famously termed “events”. Unplanned, unexpected and often unwanted events happen. Things go wrong. Machines break down. Supplies get delayed. Workers strike. Competitors steal a march. Customers get upset, with or without good reason. Projects go over budget. Deadlines get missed. Tasks get forgotten, or fall through the cracks. People get ill or have accidents at critical moments. People make mistakes. People get convinced that other people have made mistakes. Colleagues fall out. Rumours spread. The best laid plans go awry and things don’t work out as intended.

This is life. It has to be dealt with, and the only way it can be dealt with is through the very human process of talking to people and working things out. Situations need to be explained and understood. Conflicts need to be resolved and tensions eased. Mistakes, including the manager’s own mistakes, need to be recognized and rectified. People need to be admonished or forgiven, and helped to do better.

Theories of management control are of little help here. You have to work with individual human beings and their actual motivations and behaviours, not with what theories might assume. You have to work, too, with their individual conceptions of the world and how it works, and with their individual concerns and preoccupations, their likes and dislikes, their moods and emotions. The management literature can still offer valuable insights, however.

The literature on sense-making, for example, helps us to understand how people make sense of the world and how the sense they make of it adapts to new circumstances. One of the very important things that managers do is make sense of things for the employees reporting to them, explaining what the organization is about and how their work fits into it, for example. And one of the challenges when things go wrong is to make sense of what has happened and why, giving them a story that fits both with the grander organizational story and with their own personal life stories, on the basis of which they can adapt and move on.

The ethics of management are also important here. Though ‘business ethics’ is sometimes dismissed as an oxymoron, the fact is that managers are human beings, the people they manage are human beings, and no matter what the setting the relationships between any human beings are moral relationships. A good manager, like a good friend, will be compassionate and caring, truthful and fair, human-hearted, to use an Eastern term, or loving, to use a Western one. Of course, we would never put the word “loving” in a manager’s job description, just as we would never put in the word “coping”. It’s not scientific enough, not sufficiently output-oriented; it smacks of inefficiency and softness when we want to signal efficiency and hard results. But I don’t think you can manage well without it.

John Hendry is the author of Management: A Very Short Introduction and Between Enterprise and Ethics: Business and Management in a Bimoral Society. He was the founding Director of the University of Cambridge MBA and Head of the Reading University Business School, and is now Emeritus Professor of Management at Henley Business School and a Fellow of Girton College, Cambridge.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to on Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to OUPblog only Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credits: Author’s own drawings. All Rights Reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

The post Management for humans appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesRiding the tails of the pink ribbonFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldThe economics of cancer care

Related StoriesRiding the tails of the pink ribbonFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldThe economics of cancer care

October 10, 2013

Riding the tails of the pink ribbon

The iconic pink breast cancer awareness ribbon — once a consciousness-raising symbol — now functions primarily as a logo for the breast cancer brand.

The iconic pink breast cancer awareness ribbon — once a consciousness-raising symbol — now functions primarily as a logo for the breast cancer brand.

The breast cancer brand, like any other brand, is comprised of a “set of expectations, memories, stories and relationships that, taken together, account for a consumer’s decision to choose” the breast cancer brand over something else. It draws from a collection of recognizable symbols, images, and meanings within, in this case, mainstream breast cancer culture (i.e. pink ribbon culture) to encourage people to buy and display “pink.” Using basic advertising principles, the brand capitalizes on emotional resonance to increase social and financial investment in the brand.

The breast cancer brand has become so successful in forging emotional connections with potential consumers that the marketplace is filled with branded products, services, events, and advertisements that use the brand’s familiar associations (i.e. fear of the disease, hope for a cure, and the goodness of the cause) in the name of awareness and improving women’s lives. Those that incorporate the breast cancer brand into their business portfolios may, or may not, have actual ties to the breast cancer cause. Regardless, those who use the brand tend to make money, fortify public reputations and increase visibility and consumer loyalty.

Ads for the Avon breast cancer walk draw on imagery of triumphant women supporting a good cause while having a great time, showcasing passionately fabulous and amazing lifestyles.

Avon Walk for Breast Cancer. Avon.

After paying for the administrative overhead, some of the funds raised at the walks do go to breast cancer research grants. However, the organization earned only a C+ rating from Charity Watch (formerly known as American Institute of Philanthropy) in 2010 because the organization spent $39 for every $100 it raised. The 2010 report titled “Avon Raises Awareness for Its Cosmetics and for Breast Cancer” cautions consumers that companies may engage in such “high profile activities” based on the “amount of publicity and brand awareness they generate rather than the efficiency with which funds are raised or the level of awareness generated for breast cancer.”

Other companies use the breast cancer brand to sell pink products and lifestyles without a promise to contribute resources to the cause. The nylon hot pink awareness wig is a “curly haired costume accessory during Breast Cancer Awareness fundraisers to get passersby to smile while supporting the cause.” Oriental Trading Company has a line of breast cancer awareness party supplies that capitalize on the festive spirit associated with the breast cancer brand. Proceeds go directly to the profit centers of Oriental Trading Company. That is, unless the products are sold within the exclusive “Running Ribbon” product line that, for a limited time period, contributes 15% of proceeds to Susan G. Komen for the Cure®. It is up to the consumer to keep track of which pink ribbon purchases indirectly contribute to a breast cancer charity, and which ones do not.

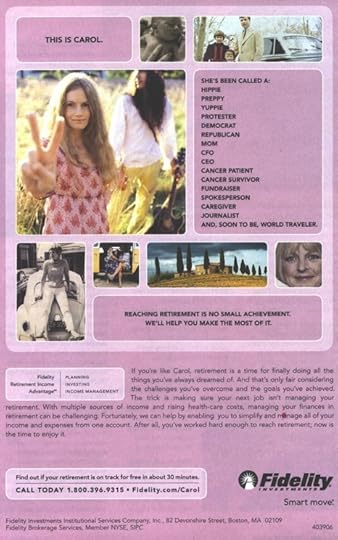

Still other companies use breast cancer associations without the congruence of an official mention of breast cancer or related advocacy. The first time I noticed one of these ads was in 2006. A full-page print advertisement from Fidelity Investments used the breast cancer brand to market financial planning and income management services to women. The Fidelity ad, awash in pink, painted a portrait of a breast cancer survivor named Carol.

This is Carol. Fidelity Ad.

The list of labels describing Carol, surrounded by select photographs, seems to be a trajectory of the various stages of her life as she transitions from rebellious youth (HIPPIE, PROTESTOR) to a successful female member of society (PREPPY, YUPPIE, MOM, CFO, CEO). While the generic list and accompanying narrative (i.e. if you’re like Carol) seems to cast Carol as the generic woman, the political and professional labels are too narrow to be inclusive. Fidelity’s targeted woman consumer has money and clout. According to Forbes, only 4% of CEOS running America’s largest companies in 2012 were women, and that was a record number.

What’s more, Fidelity recognizes that breast cancer is an important women’s health issue. In addition to high incidence rates particularly among women approaching retirement age, breast cancer has cache. A colleague told me about a breast surgeon who referred to breast cancer as “the happy cancer.” And it’s got the pink swag to go with it. Thus, Carol represents the quintessential she-ro of pink ribbon culture, a triumphant breast cancer survivor who fights the disease with style, learns from her experience, becomes a better person, and shares her wisdom with others. The Fidelity ad did not have to use the word breast cancer to create this association. The color pink, along with the accompanying list — CANCER PATIENT, CANCER SURVIVOR, FUNDRAISER, SPOKESPERSON — creates the tableau. Dominant narratives in pink ribbon culture fill in the blanks.

According to Action Marketing, Fidelity’s generic portrayal of Carol failed to represent an excellent marketing-to-women strategy. What’s more, the ad violated the “don’t think pink” rule, which was popularized in 2004 when branding consultants learned that using the color pink to market to women didn’t work. A recent study at Harvard found the same thing. Stereotypical gender cues like the cliché of pinkness suggest a superficial awareness of women’s lives that is unappealing and triggers defensiveness.

The lesson: Companies should reach out to women with scenarios they care about and can relate to, without jargon, condescension, or trivializing symbolism.

Apparently, not everyone got the message. Last month, Harbinger Fitness already began sending out marketing materials to blend in with the pink ribbon display. An email pitch with the subject line, “pink the new black get fit gear under thirty” profiled “Pretty in Pink Fitness Gifts” that would be perfect for a woman “this Holiday Season” or “after the holiday feasting.” I can only presume that breast cancer awareness month must have been named an official holiday. The pink-themed gear just for women includes a lifting strap vaguely in the shape of a pink ribbon. Yet there is no mention of breast cancer, fundraising, or advocacy. The company simply uses the breast cancer brand and its association with the color pink to market to women during the awareness season.

Apparently, not everyone got the message. Last month, Harbinger Fitness already began sending out marketing materials to blend in with the pink ribbon display. An email pitch with the subject line, “pink the new black get fit gear under thirty” profiled “Pretty in Pink Fitness Gifts” that would be perfect for a woman “this Holiday Season” or “after the holiday feasting.” I can only presume that breast cancer awareness month must have been named an official holiday. The pink-themed gear just for women includes a lifting strap vaguely in the shape of a pink ribbon. Yet there is no mention of breast cancer, fundraising, or advocacy. The company simply uses the breast cancer brand and its association with the color pink to market to women during the awareness season.

In Jersey Magazine, 2011

In Jersey Magazine

Research shows that women are turned off by such trivializing marketing techniques, but the pink ribbon is working well enough to keep the multi-billion-dollar breast cancer industry alive. Even if the same cannot be said for the some 40 thousand individuals who die from the disease each year.

Gayle A. Sulik MA, PhD is research associate at the University at Albany (SUNY) and founder of the Consortium on Breast Cancer. She was a 2008 Fellow of the National Endowment for the Humanities and is winner of the 2013 Sociologists for Women in Society Distinguished Lecturer Award for Pink Ribbon Blues.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images courtesy of Gayle Sulik.

The post Riding the tails of the pink ribbon appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldEducation depends on brainsMetro North disruption and “employer convenience”, double taxation – again

Related StoriesFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldEducation depends on brainsMetro North disruption and “employer convenience”, double taxation – again

The golden wings of the bicentennial: Giuseppe Verdi at 200

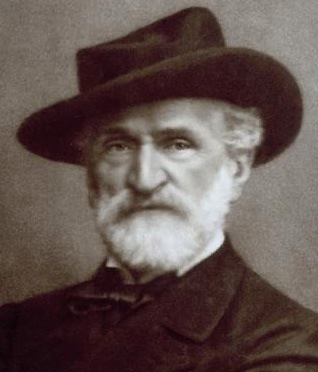

Giacomo Brogi (1822-1881), Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi (cropped). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

It is finally here. The big anniversary. The bicentennial. Today, Giuseppe Verdi turns 200. There has been excitement in the air for quite some time—leading opera houses presenting new productions and outreach initiatives to honor the great composer, publishing companies rushing to release a host of new books for all sorts of readerships, and public and private organizations around the world (governments and municipalities, research centers and fan clubs) working to celebrate the occasion as it deserves. Countless anniversary concerts, performances, and conferences are going on this week. So are exhibits and other initiatives: Porte aperte per Verdi (Open doors for Verdi), proudly announces the Teatro alla Scala, the celebrated opera house in Milan where Verdi enjoyed the first and final triumphs of his career. What I find most exciting, and in many ways moving, this mid-October week, is the excitement and dedication of scholars, practitioners, and lovers of opera around the world. Researchers boarding trains and airplanes (often on their own dough) to travel to conferences. Radio stations broadcasting an abundance of Verdi marathons and “complete” cycles, along with interviews and tributes. The world’s leading conductors and singers preparing and presenting major performances. People gathering around Verdi monuments from Parma to New York to offer impromptu renditions of the chorus of the Hebrews in Act 3 of Nabucco, “Va, pensiero.”Click here to view the embedded video.

Just as that iconic chorus flies “sull’ali dorate” (on golden wings), so do all of these initiatives fly on the wings of the bicentennial, which are golden in their own right—offering good return in terms of visibility and (where applicable) box office revenue. Even La Scala’s “porte aperte,” indirectly, constitute a precious opportunity for marketing and promotion. Sales at the gift shop and box office, to be sure, will be far above average today. We are often more excited about the revival of a lesser-known Verdi opera, a new production of one of his perennial favorites, or a coffee mug with his effigies, if it takes place or is purchased in an anniversary year, or—better still—on his very birthday. Aren’t we privileged to be able to say, from now on, “I was there”? The question is an important one. What will be left of all this next week, next month, or next year? A chipped coffee mug, the skeptical reader might respond. The danger exists that this bicentennial, like countless other celebrations, will end up not only celebrating, but also monumentalizing and enshrining Verdi. Distancing him and his work even more into a finished past.

But there is a bright side to the tale of this bicentennial: gone are the days when we built busts and statues of bronze or stone in piazzas, squares, and foyers. Instead, we have the opportunity to concentrate primarily on the interest in Verdi’s music and theater, which remains undiminished, with no real danger that it will fade after 2013. His operas continue to travel around the world in live performances and recordings, and new technologies—from the internet to high-definition simulcasts—have made them accessible to broader audiences. An increasingly interactive public engages with Verdi and his performers through e-lists and blogs. We continue to look for new meanings and expressive potential in Verdi’s works. His connection to Shakespeare continues to fascinate us and to prompt novel and insightful discussions (witness Garry Wills’ important 2011 book, Verdi’s Shakespeare: Men of the Theater). When we stage his works, we often seek to reinterpret them, re-contextualize them, and make them our own by bringing them closer to us in time and space—the much talked-about recent Metropolitan Opera production of Rigoletto by Michael Mayer, set in Las Vegas, is a telling example.

Even the large red volumes of the Works of Giuseppe Verdi—the series that, when complete, will provide critical editions of all of the composer’s works—might appear to be a monument in its own right, but it is indeed far more than that. To mention only one of the recent volumes, in Giovanna d’Arco we can now hear the protagonist pray explicitly to the Virgin Mary, and not to an unnamed supernatural entity as the censors in Milan had demanded in 1845 (we heard the text as Verdi and Solera had intended it in this summer’s performances at the Festival della Valle d’Itria in Italy). But performers can still shun this opportunity and use the traditional, censored poetry, as in last month’s performance at the Chicago Opera Theater (discussed in a recent blog entry by Garry Wills). Indeed, we continue to explore and to discuss (sometimes heatedly) the political and cultural significance of his works in his own time and beyond.

In addition to many volumes of the Works of Giuseppe Verdi still unpublished or in the making, much remains to be done, and opportunities for new work abound. Each time sketch materials for his operas are released by the Verdi heirs at Sant’Agata we learn more of the creative process, and have the opportunity to contemplate his music from a new vantage point. A forthcoming new English edition of Abramo Basevi’s widely cited Studio sulle opere di Giuseppe Verdi, prepared by Stefano Castelvecchi, engages a mid-nineteenth-century analytical study in a novel and stimulating way, making it accessible to a broad readership. The conference Verdi’s Third Century: Italian Opera Today, currently underway at New York University, has brought together scholars, practitioners, and critics to discuss the circulation and perception of Verdi—and of Italian opera—in today’s world, focussing principally on how Verdi’s works have been interpreted, imagined, and appropriated. Papers and round tables explore staging and singers, Verdi’s presence in silent cinema and in popular culture, the work of publishers, critics, and bloggers, to mention only some of the themes of the conference.

These are the golden wings of the bicentennial. Despite the ever-increasing span of time that separates us from Giuseppe Verdi, he remains someone whom we actively study, engage, and question, on this day and beyond. His presence is so vital that those spontaneous renditions of “Va pensiero” that resonate around the world today, probably along with crowds large and small singing “Happy birthday, dear Verdi,” will seem not only quaint, but also meaningful expressions of an important cultural presence that will not fade as the coffee mugs are inexorably chipped.

Francesco Izzo teaches music at the University of Southampton and is Co-Director of the American Institute for Verdi Studies. He is the author of Laughter between Two Revolutions: Opera Buffa in Italy, 1831-1848 and the editor of Verdi’s Un giorno di regno for the Works of Giuseppe Verdi (forthcoming). He authored the entry on Verdi in Oxford Bibliographies.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The golden wings of the bicentennial: Giuseppe Verdi at 200 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFrancesca Caccini, the composerBreaking Bad’s Faustian CastPragmatic preservation and the Vanderbilt Hotel

Related StoriesFrancesca Caccini, the composerBreaking Bad’s Faustian CastPragmatic preservation and the Vanderbilt Hotel

Shakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remains

What are we going to do with Richard III? More than a year after his bones were unearthed in Leicester, the last Plantagenet king is still waiting for a resting place. The initial plan, backed by the UK government and the University of Leicester, was that Richard’s remains should be interred in Leicester Cathedral, just a few hundred yards from the site where they were discovered. Yet a popular campaign on behalf of York Minster has sparked a fierce competition over these once reviled bones. Petitions on behalf of the rival cathedrals have each collected many thousands of signatures; a clutch of Richard’s distant relatives calling themselves the Plantagenet Alliance have demanded and been granted a judicial review. Meanwhile, Leicester Cathedral’s preferred design for the tomb — incised with a plain cross that seems to speak more of penance than of majesty — has so alienated some members of the Richard III Society that they have threatened to withdraw their promised donations.

The proposed design for the tomb of Richard III in Leicester Cathedral. By permission of architects van Heyningen and Haward.

The public squabble over some badly battered (but potentially lucrative) bones may not be very edifying, but it participates in a venerable tradition. For more than five hundred years, people have been arguing, sometimes violently, about the fate of Richard III’s remains. It came to blows in the city of York in 1491, six years after Bosworth. The schoolmaster John Burton, being “distempered with ale,” declared that Richard was “a hypocrite, a crouchback, and was buried in a dike like a dog.” Burton was then struck by another man, John Payntor, who insisted that Richard had not been buried like a dog, but “like a noble gentleman.”

The truth lay somewhere in between. For several days after Bosworth, Richard’s naked corpse had been placed on mocking display in a Leicester church. Analysis of the skeleton reveals the posthumous humiliation to which the body was subjected, including a sword-thrust through the buttocks. When the king’s remains received burial at last it was in a hastily dug grave — too short for his height — in the humble priory of the Greyfriars.

Human Remains found in trench one of the Grey Friars dig. A11-2012-SK1-19e. By permission of the University of Leicester.

It took Henry VII ten years to provide his predecessor with an inexpensive tomb, adorned by a distinctly disparaging epitaph. A few decades later the priory was dissolved, and the king’s body disappeared, apparently forever. In Shakespeare’s day it was rumoured that Richard’s exhumed corpse had been dragged through the streets by a jubilant mob and thrown in the River Soar.

Shakespeare was perhaps aware of the questions and controversies swirling around the fate of Richard’s remains. At the conclusion of his Richard III, the defeated tyrant’s body is simply left on stage (or, as in the recent production with Kevin Spacey in the title role, winched up to dangle ominously over the heads of the victors). Shakespeare has the victorious Henry give explicit commands regarding the burial of other combatants, but nothing is said about Richard. There is an ironic disjunction between the play’s relentless focus on Richard’s deformed body, which seems almost a character in itself, and the silence which surrounds his corpse at the end.

Richard’s modern admirers are apt to condemn Shakespeare for his depiction of the king as a hunchbacked psychopath. Yet if Shakespeare created a monster, he is also largely responsible for our enduring fascination with the figure of Richard III. And if Shakespeare’s play is full of fabrications, it is also suffused with genuine fragments and traces of Richard’s era. Much as the stones of the dissolved Greyfriars were employed to repair and expand the nearby church that became Leicester Cathedral, Richard III gathers up stray pieces of language, memories, and customs and assembles them in a new context. Even the century-old words of a drunken York schoolmaster find an echo in the play, wherein Richard is repeatedly likened by his enemies to a dead dog.

Shakespeare’s Richard III is, among other things, a play about the difficulty of laying the dead to rest. Significantly, it is Richard himself who is keenest to provide his victims with a final burial, imagining that the claims of the dead end with their interment. “I’ll turn yon fellow in his grave,” he says of the murdered Henry VI, “And then return lamenting to my love.” When the assassin Tyrrell assures him that the Princes in the Tower are dead, he presses “And buried, gentle Tyrrell?” Yet on the night before Richard’s own death in battle, these victims and more arise from their supposedly secure graves to pronounce vengeance upon him. As Richard learns too late, there is little point in shoving bodies under the earth when the longings and grievances of the past remain abroad.

Might Shakespeare’s play have something to whisper to those now seeking to claim Richard’s remains for Leicester or for York? Could we be a little naïve in imagining that interment in one cathedral or another will settle our accounts with him and with his age? Experience shows that burying Richard III has never been a very effective way of getting him to rest in peace. The modern world is shot through with particles and traces of his troubled times, some of them preserved in Shakespeare’s play, some in the unresolved legacy of conflict between north and south, some in the very legal system to which we turn to decide what to do with his remains. Wherever his bones come to rest this time around, Richard III will not cease to be our contemporary.

Philip Schwyzer is Professor of Renaissance Literature at the University of Exeter. He is the author of the book, Shakespeare and the Remains of Richard III.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) The proposed design for the tomb of Richard III in Leicester Cathedral. By permission of architects van Heyningen and Haward; (2) Human Remains found in trench one of the Grey Friars dig. A11-2012-SK1-19e. By permission of the University of Leicester. Do not reproduce either image without permission.

The post Shakespeare and the controversy over Richard III’s remains appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWatching Titus, feeling fleshShakespeare’s hand in the additional passages to Kyd’s Spanish TragedyMr Leggy has left the building (for a while)

Related StoriesWatching Titus, feeling fleshShakespeare’s hand in the additional passages to Kyd’s Spanish TragedyMr Leggy has left the building (for a while)

October 9, 2013

An interlude

Every word journalist is on the lookout for interesting pieces of information about language. H. W. Fowler, the author of the great and incomparable book Modern English Usage, confessed that his main reading was newspapers. Naturally: where else could he find so much garbled English? However, Fowler also took to task Dickens, Thackeray, and other greats, who died before they had a chance to profit by his strictures. I too have a heap of multifarious clippings and sometimes feel the desire to share part of my treasures with the world. Unfortunately, my treasures look more like paste than like diamonds.

Cherchez la femme.

From a student newspaper: “If a student said she wanted to study in America, it’s daunting for them to figure how they organize what’s private versus public….” She is right, and so are they. Foreign students are beset by problems and the mysteries of English, both public and private. What was it that Elizabeth, Elspeth, Betsy, and Bess found? A mare’s nest, if I remember correctly. A learned linguist writes: “…who explains everything explains nothing, does she?” I agree. If one hitches her wagon to a star, they may have a bad fall.

Producing the species by division, or, One murderer, two murderers, many murderers.

“It’s akin to telling a first-time murderer that they won’t be sent to prison as long as they give up their guns.” Politically correct but terrifying.

To be or to not be.

Inserting not between to and the infinitive is here to stay. This usage is not old, for I don’t remember seeing it forty years ago, or perhaps it occurred seldom and passed unnoticed. Today even George F. Will writes: “The broadcast and cable organizations that pay billions for the rights to televise football have an incentive to not call attention to health problems.” If you are received at Lady Windermere’s, you are fully respectable. Likewise, if George F. Will can say to not call attention, Hamlet is put to shame for all eternity.

Political jargon.

The second elements of compounds sometimes pry themselves loose from their roots and become productive suffixes. This happened to -gate after Watergate and to -burger, abstracted from hamburger. Such creations, though not always elegant, are not necessarily repellent (unless trodden to death). But when phrases begin to multiply like maggots, they inspire horror in timid hearts. Some people may remember the wonderful and efficient “reset button.” Requiescat in pace. But I truly enjoyed the following: “An analysis in the Times of Israel, citing unnamed sources, said that Obama’s decision to hit the pause button had ‘privately horrified’ Jerusalem.” The pause button! I am trying to think creatively: the hate button, the gluttony button, the lechery button…. Hit them and don’t be privately horrified.

More amazing horrors.

Slate reported that in the recent past no other new coinage had irritated people more than amazeballs. “In September 2012, amazeballs rolled into the Collins Online Dictionary, with the definition ‘an expression of enthusiastic approval’. The Urban Dictionary glosses it thusly: ‘Basically beyond amazing. Being so awesome that a regular word can’t describe you’. It appeared on PeretzHilton.com as early as 2009…. The word began trending on Twitter that year.” I detest the adverb thusly, though I see and hear it all the time. I also detest awesome—not because it is a wrong word but because, along with cool, it has become a marker or even the marker of all emotions. Be that as it may, the end of the article in Slate cannot but afford pleasure: “In November of last year, amazeballs… was added to the Dictionary of the Most Annoying Words in the English Language, when it was defined as ‘an exclamation inviting someone to hit you’.” Time to hit the pause button.

An example of a particularly repulsive verb has been sent to me by an unknown correspondent: “The effects of last night’s storm continue to repercush this morning.” Other back formations (such as to sculpt) do not arouse our ire only because we are used to them, but repercush…. In the nineteenth century, the phrase the genius of the language enjoyed some popularity. No doubt, repercush (from repercussion) has been brought to life by the genius of Modern English, and it is all over the place. Yet we (or some of us) shiver. Speakers create neologisms, and sensitive people object. Impact, which has replaced influence, may have nothing to recommend it, but the verb to impact is a well-known irritant. At one time, indignant readers implored the editors of popular journals to kill the noun meet. Lost battle, ladies and gentlemen: wilderness will take over and produce what is called in Academia the history of language. Stay away from it as long as you can.

Nothing is new under the linguistic moon.

The United States, 1863. A contributor to the short-lived periodical The Continental Monthly wrote an article titled “Word-Murder.” It was about the abuse of adverbs, the disease I call adverbialitis. “Actually was a nice word. We suffered a loss when it died, and it deserves this obituary notice. It was a pretty word to speak and to write, and there was a crisp exactness about its very sound that gave it meaning.” The Civil War is over, and many more wars have been fought since 1863, but the reinforcing adverb actually has proved to be invincible. As could be expected, if you reinforce everything you say, the effect is no longer felt: to be heard, you have to shout louder and louder. Sometimes, while listening to people, I take notice of the sentences that do not begin with actually. Those are few. But some clouds have an attractive lining: however annoying the interlocutor or the speaker may be, a linguist is never bored, for he/she/they can always ignore the content and observe the accent and usage. The author of the article in The Continental Monthly also buried the once workable adverbs positively, seriously, perfectly, really and truly, and the phrase upon my honor. Most of them are still alive, risen from the grave like John Barleycorn.

Now all the way to the British Isles! From a letter to the editor, dated July 15, 1905: “I wish to draw attention… to the misuse of the verb to lay in place of the verb to lie.” What a chestnut! The correspondent bemoans sentences like I am going to lay down. He then finds the same dreadful mistake in Anthony Trollope, and the editor refers to the confusion of lay and lie in Childe Harold. The confusion is ancient and ineradicable, so let the sleeping dogs lie, take the defeat lying down, “lay down,” and have a rest: no one is listening to you. Be grateful that hens still lay eggs, and, if that is not enough, murmur to yourself the end of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 138: “Therefore I lie with her, and she with me, / And in our faults by lies we flatter’d be.” By the way, some wide-awake undergraduates invariably giggle when they hear about the lay of the Nibelungen (a first class lay, I may add).

Nautical idioms?

Is the origin of the following idioms known? From E. W. J. B.’s letter to The Spectator 113, 1914, p. 496 (“Nautical Colloquialisms”): “…take the two expressions touch and go, meaning a narrow escape, and hard and fast, for an incisive conclusion. Both I believe to be instances from nautical experience—the first to signify a slight or momentary grounding and subsequent floating, the second a stranding of the vessel.” Perhaps an expert in nautical language or some regular reader of The Mariner’s Mirror will be able to tell us whether E. W. J. B.’s hypotheses are to be trusted.

Old Scotticisms.

Rather long ago I began reproducing items from Scots Magazine for 1760. There I found Scots words as opposed to their English equivalents and was surprised that some Scotticisms of the mid-eighteenth century are now part of the English Standard. Others were curious for their own sake. No one commented, and today I’ll close the series, to stage a graceful exit rather than to make a point.

S. compete, E. enter into competition;

S. adduce a proof, E. produce a proof;

S. in no event, E. in no case;

S. bygone, E. past;

S. a chimney, E. a grate;

S. to furnish goods to him, E. to furnish him with goods;

S. to be angry at a man, E. to be angry with a man;

S. butter and bread, E. bread and butter;

S. deduce, E. deduct;

S. a pretty enough girl, E. a pretty girl enough (!).

A Pretty Enough Girl

A Girl Pretty Enough.

And on this pretty note, I’ll finish today’s interlude. Enjoy the pictures by Karl Bryullov (1799-1852) and note that he and Pushkin (1799-1837) were born in the same year.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of blog@oup.com; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Italian Morning by Karl Bryullov, 1823. Public domain via Wikipaintings. (2) Bathsheba by Karl Bryullov, 1832. Public domain via Wikipaintings.

The post An interlude appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOstentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poeticaEtymology gleanings for September 2013Are you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and folly

Related StoriesOstentatious breeches, gods’ braggadocio, and ars poeticaEtymology gleanings for September 2013Are you daft or deft? Or, between lunacy and folly

Interrogating inequality around the globe

The Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association in New York brought together leading sociologists from around the world to discuss the field, focusing on “Interrogating Inequality.” Arne L. Kalleberg, Editor-in-Chief of Social Forces, was lucky enough to steal six sociologists 20 blocks south to Oxford’s New York office. He spoke to sociologists from South Korea, Brazil, Germany, and Israel shared their thoughts on the current state of sociological research, the global community of sociologists, and the state of inequality research in their home country.

The state of inequality research around the world

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sociologists in conversation: Germany

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sociologists in conversation: Israel

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sociologists in conversation: Brazil

Click here to view the embedded video.

Sociologists in conversation: South Korea

Click here to view the embedded video.

Published in partnership with the Department of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Social Forces is recognized as a global leader among social research journals. The journal emphasizes cutting-edge sociological inquiry and explores realms the discipline shares with psychology, anthropology, political science, history, and economics.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only sociology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Interrogating inequality around the globe appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldAre the differences in acceptance of LGBT individuals across Europe a public health concern?Place of the Year: Through the years

Related StoriesFive reasons why China has the most interesting economy in the worldAre the differences in acceptance of LGBT individuals across Europe a public health concern?Place of the Year: Through the years

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers