Oxford University Press's Blog, page 896

October 6, 2013

Confronting habitat loss in the 21st Century

By Alexander Gillespie

According to the Convention on Biological Diversity, ‘habitat’ means the place or type of site where an organism or population naturally occurs. Tomorrow is World Habitat Day. The obvious question is, why do we need a day devoted just to habitat? The short answer is that loss of habitat is now the foremost conservation concern of the 21st century. If you want to know more, read on.

Historically, habitat loss was the second most important reason for species loss: the first reason being species introduction. This is no longer the case. Globally in the 21st century, and particularly in some regions such as Europe, habitat loss is the primary cause of species extinction. Habitat destruction is caused by numerous factors, but the most important is exponential human population growth. The mid-term projection for 2050 is 9.1 billion people, this being considerably higher than the 6.5 billion who currently exist. Expanding human populations have already profoundly changed the global landscape over the past few centuries. It is estimated that between 1700 and 1980 the world’s forested woodlands declined by nearly 20 percent from 6.2 billion to 5.1 billion hectares. The degree of human disturbance of vegetated land varies widely from continent to continent. In Europe less than 12 percent of land has only low disturbance whereas other regions, such as South America, have 75 percent with low levels of disturbance. On a global level, 26 percent of all land surfaces are highly disturbed, 27 percent are subject to medium disturbance, and 47 percent are experiencing low disturbance. In some countries, very little natural vegetation remains. For example, in Bangladesh a mere 6 percent of original vegetation is left; and in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands all but 4 percent of lowland bogs have been undamaged.

Although there are many important habitats being lost, one of the best examples is the removal of the Earth’s tropical forests, which are probably the premier areas for species habitat on the planet. In the last 8,000 years about 45 percent of the Earth’s original forest cover has disappeared, mostly during the past century. The present area of the world’s forest is 3.9 billion hectares. This area is the equivalent to North, Central, and South America combined. The Earth lost 450 million hectares of its tropical forest cover between 1960 and 1990. Asia lost almost one-third of its tropical forest cover during this period, whereas Africa and Latin America each lost about 18 percent. Between 1990 and 2005 the world lost a further 3 percent of its total forest area, with an average decrease of some 0.2 percent per year. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazonia surged from 14,000 square kilometres per year in the early-1990s to consistently over 20,000 square kilometers per year between 1995 and 2005. Forty percent of the Amazon could be gone by 2050 if present trends continue. Likewise Papua New Guinea, which had a deforestation rate of close to 1.7 percent per year in 2007, was projected to have lost more than half of its forests by 2021.

Other habitats of particular note with regard to oceanic species are coastal zones. These habitats are valuable in every sense of the word. These are the areas where the oceanic upwelling systems collide as the cold, nutrient-rich, deep water currents run up against continental margins. They are centres for social and economic wealth, hotbeds for marine biodiversity, filters for marine pollution, and form part of a number of intricate ecological webs. They are the core habitats of the marine world and the critical habitats typically manifest themselves as coral reefs and/or habitats of seagrass or mangroves. With regards to mangroves, estimates in 2010 suggested that more than one in six mangrove species worldwide are in danger of extinction due to coastal development and other factors, including climatic change, logging and agriculture. Similarly, despite their clear importance, both warm water and cold water coral reefs and their dependent species are increasingly under threat and the current rate of loss of coral reefs is estimated to be 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate without human interference. The first global surveys on coral reefs began to appear in the late-1990s, from where it was apparent that these ecosystems, both warm and cold, were already highly damaged from multiple sources including overfishing, indiscriminate fishing methods such as deep sea or bottom trawling, land-based pollution, and even climate change. Episodes of coral bleaching over the past 20 years have been associated with several causes including increased ocean temperatures.

Habitat loss impacts upon 86 percent of all threatened mammals. In West Africa it has been shown that during the 20th century approximately ninety percent of the original range of the African elephant was lost. More than 70 percent of the habitat of each of the African Great Apes has been negatively affected by infrastructure development. For the orangutan, which is often threatened by the development of palm oil plantations, the figure is 64 percent. By 2030, it is expected that less than 10 percent of Great Ape habitats in Africa will be free from the impacts of infrastructure development, and for the orangutan, the figure is 1 percent. Habitat loss impacts upon 86 percent of all threatened birds. Of this figure, 87 percent are at risk because of habitat loss due to agricultural practices while habitat change as a result of inappropriate forestry extraction is responsible for 55 percent (668) of all bird species being at risk of extinction. Habitat loss has also been identified as a primary threat to species of Lynx, leopard, tiger, and lions. It is also a threat to some species of rhinoceros and was a concern for certain types of bear such as the panda. Habitat loss is also identified as having a significant impact on 87 percent of all threatened amphibians, as well as bats and habitat dependent insects such as butterflies. With regard to butterflies alone, Europe has lost 15 percent of its critical habitats between 1990 and 2006. Habitat loss is also primarily responsible for 91 percent of all threatened plants.

Habitat loss in the oceanic environment is a very direct concern for all species that are dependent upon such areas. Numerous examples of this range include, inter alia, sea turtles, dugongs, and cetaceans. Episodic losses of seagrass have also be associated with extreme weather events and bad management regimes allowing excess nutrient run-off, oil spills, sewage, and other pollutants. A 2009 study suggested that that the total area of known seagrass meadows decreased by 29 percent between 1879 and 2006, and that this rate was increasing to such a degree that a football-pitch size of seagrass was lost every thirty minutes. A number of highly endangered whales, especially small cetaceans such as Mexico’s Vaquita, are threatened by loss of habitat. It was the loss of habitat that drove the Baiji to extinction in China. Similar threats now challenge the highly endangered Western Pacific Grey whales, foraging in oil exploration grounds off Russia.

Convinced now, that a day to consider habitat is a serious enough issue?

Alexander Gillespie is Professor of Law at the University of Waikato, New Zealand and is the author of International Environmental Law, Policy, and Ethics, published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Jungle burned for agriculture in southern Mexico by Jami Dwyer, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Coral Reef in Florida by Jerry Reid (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service WO-3540-CD42A) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Confronting habitat loss in the 21st Century appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe precarious future of ocean megafaunaPrivate equity, hedge funds must be understood to be regulated effectivelyThe whale that inspired Greenpeace

Related StoriesThe precarious future of ocean megafaunaPrivate equity, hedge funds must be understood to be regulated effectivelyThe whale that inspired Greenpeace

October 5, 2013

Celebrating World Teachers’ Day

Today is World Teachers’ Day. What is World Teachers’ Day, you ask? It is “a day [first celebrated in 1994 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization] devoted to appreciating, assessing, and improving the educators of the world.” This internationally recognized day commemorates teachers around the globe and their commitment to children and learning. As I began thinking about this day and its significance, it occurred to me that the days we have set aside to celebrate the contributions of particular groups of people – days like Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Administrative Assistant’s Day – are days dedicated to acknowledging how much these groups of people do throughout the year, generally for children who take them for granted. (And yes, I do think that is how many admin assistants might explain their jobs as well!) But, as I thought more deeply about why we go out of our way to honor these groups of people, I realized that we set these days aside to focus on those roles and professions that provide one with the opportunity to change the lives of others. Celebrating World Teachers’ Day gives us all a chance to reflect on the incredible and crucial role that teachers play in the lives of children and the adults they become.

It is likely not a surprise to you to hear that teachers matter. Studies have shown that having a strong teacher, even for one school year, can lead to lasting academic and social performance gains. Researchers have demonstrated that, for children with social or behavioral difficulties, having a nurturing teacher can serve as a protective factor that mitigates the effect of their problems on learning and peer relationships.

There are more different and wonderful ways that teachers matter than I can discuss here, so I will limit myself to talking about the importance of teachers for language and literacy development. Becoming literate is arguably the most important academic task a child will tackle during childhood. Being able to successfully decode and comprehend written information allows a child access not only to stories, but also to informational text (for example, periodicals and biographies, as well as science, social studies, and math textbooks). Becoming literate, and learning to read, then, is an avenue for finding out more about the world around us, and a doorway into new worlds, where we can learn about the ways that other people think and act.

Children and their teacher in a classroom

Teachers help children with every step of this process. In preschool and kindergarten, it is vitally important for children to engage in word play – to sing songs, listen to and make up rhymes, and begin to identify the individual sounds in words. Through reading books to young children, teachers introduce them to unfamiliar vocabulary words they would never hear in casual conversation, and prime them to comprehend what they will read independently in later years. Most importantly, great teachers help young pre-readers and readers discover a love of literature. As children move up to first grade and beyond, teachers help them make sense of the tricky features of the English language by helping them break its code and pair together letters and sounds, recognize word patterns, and spell with accuracy. For the majority of children, for whom learning to read is a fairly arduous process, having teachers who help them become persistent learners smooths this path. Eventually, this hard work pays off, when a child can independently select a book he knows will be interesting to him, read it on his own, and then talk with others about the meaning of the text. This journey to reading success takes many years and requires that children receive ongoing, responsive, and personally tailored support – truly, every teacher who helps a child become a reader deserves recognition.

And, on days like World Teachers’ Day, they fortunately get that recognition. The thanks, and the reminder that reaching changes lives, of course comes at other times, too. And it is perhaps those unexpected moments of awareness that are most precious to teachers. I remember when my mother, a career elementary school teacher, received a letter from a student who had been in her third grade class when she herself was 31 years old. The former student, when he wrote this letter, was older than she had been when she taught him (as he mailed the letter about 24 years later). In it, he told her that he had become a writer, and explained that his confidence in his abilities stemmed from the fact that she had often encouraged him in his attempts to write, once remarking on one of his assignments, “I’ll be reading your book someday!”. He told her then, decades later, that he and his family had looked back on that assignment and her statement many times over the years, and that he was about to publish his first book after years of working as a journalist. The language and literacy skills she helped him develop many years earlier helped launch his career, and her belief that he could be a successful learner and writer likely aided him in facing the edits, critiques, and rejections that are part and parcel of being a writer. I suspect that each of us can think of one teacher, or a few teachers, who has had a similarly strong impact on our own lives, often by teaching us to read or, years after we had learned, teaching us that reading can actually be fun. If that is the case for you, does that teacher know how much he or she changed your life? If not, take the opportunity to say thank you today. If we really consider all the thanks owed to the educators of the world, we might be inclined to say that their work is priceless…just like the heartfelt cards that they receive from former students. There is no better way to say thank you to a teacher than by displaying the literacy skills he or she painstakingly taught you!

Jamie Zibulsky, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Fairleigh Dickinson University and directs the school’s MA/Certification program in School Psychology. She is co-author, with Dr. Anne Cunningham, of Book Smart: How to Support and Develop Successful, Motivated Readers. As a school psychologist, she focused on collaborating with teachers and parents to support children’s reading acquisition. Her current research focuses on the interaction between early reading skills and behavioral development, as well as teacher professional development efforts in the area of literacy.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only brain sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Children in a classroom, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Celebrating World Teachers’ Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesParricide in perspectiveHow film music shapes narrativeTo medical students: the doctors of the future

Related StoriesParricide in perspectiveHow film music shapes narrativeTo medical students: the doctors of the future

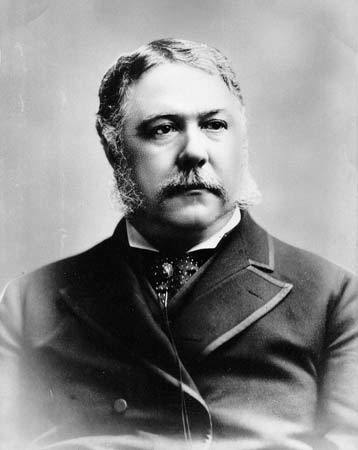

Five things you may not know about Chester Arthur

It is hard to imagine there is anything worth knowing about Chester Arthur. Many Americans might not even recognize that he was a president of the United States. By almost any measure, he is one of our most forgotten presidents: Never elected to the office in his office and a political hack before becoming Garfield’s Vice President, he was a terrible speaker, carried little influence within his own party, had become Vice President to appease his political mentor Roscoe Conkling (and his wing of the Republic party), ranks near the bottom of presidents in the numbers of books written about his presidency, and burned most of his personal papers the day before he died. Yet, there are at least five interesting, even memorable things worth knowing about Arthur.

The first is that no person ever became president with lower expectations than Arthur did. The highest political office Arthur held becoming Garfield’s running mate in 1880 was the Collector for the Port of the City of New York. His only qualification for the job was that he had been the political lieutenant for Roscoe Conkling, a colorful New York senator who led the Stalwart wing of the Republican party. Even so, President Hayes had dismissed Arthur for corruption. Thus, Arthur was unemployed and disgraced by the time of the 1880 presidential convention. Against Conkling’s wishes, Arthur agreed to be a compromise candidate for Vice President to placate Conkling’s wing of Party. The thinking was that Arthur was the least obnoxious Stalwart that could be found that he could be counted on to do nothing once Garfield got into office.

As Vice President, Arthur had done nothing except once to side with Conkling in a battle between the latter and Garfield over whom to appoint to head the Customs House in New York, Arthur’s old job. After Garfield outmaneuvered Conkling, Arthur receded to obscurity until Garfield died as a result of doctors’ incompetence in handling a gun shot wound from a would-be assassin. Everyone expected that, as president, Arthur would merely continue to be the political hack he had always been — to continue to do, in other words, Conkling’s bidding.

The second, surprising thing about Arthur is that he proved not to be what everyone had expected. He never did Conkling’s bidding. Indeed, shortly after becoming president, he met privately with Conkling, apparently to make a deal that got Conkling out of his way (including unsuccessfully offering him a seat on the Supreme Court). Arthur committed himself throughout his presidency (nearly a full term) to making appointments based on merit. The Senate rejected none of his major appointments, which included two excellent appointments to the Supreme Court.

Third, Arthur took advantage of Garfield’s death (which had been publicly understood to be an assassination by a frustrated office-seeker) to do something every other nineteenth century presidency had promised but failed to do. Most presidents before Garfield as well as Garfield had promised civil service reform, but none had achieved it. The opposition was largely based on concerns that diluting the president’s ability to remove people who worked in the civil service would weaken him and allow for a permanent class of elitists working for the government. With Garfield’s death, Arthur saw the writing on the wall. He urged Congress to enact civil service reform, and he became the first American president to sign a landmark law enacting such reform, the Pendleton Act.

The fourth is that Arthur was honest as president. Though he had spent his pre-vice presidential career steeped in the world of political corruption and known widely as Conkling’s “creature,” his administration was free of any political scandals, a rare accomplishment for a president of that era.

Finally, Arthur defended presidential prerogatives from being encroached upon by Congress. Early into his presidency, Arthur realized he had little chance to be elected to the office in his own right and thus was not hesitant to push back against efforts, even from within his own party, to strengthen Congress at the expense of the president. Instead, he helped to veto the President’s nominating, veto, and other powers throughout his time in office.

It is possible that none of these things might not impress some contemporary Americans. They may dismiss them as unimportant and archaic. Yet, they might also suggest, as I urge students and others to consider, that Arthur helped to demonstrate how the presidential office itself can transform someone. In Arthur’s case, the office drew him into defending its prerogatives and caring about leaving it at least as well off as he had found it. Arthur, in other words, rose to the occasion of being president, which ought to give pause to anyone who is cynical about politics.

Michael Gerhardt is Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. A nationally recognized authority on constitutional conflicts, he has testified in several Supreme Court confirmation hearings, and has published five books, including The Forgotten Presidents and The Power of Precedent. Read his previous blog posts on the American presidents.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Chester Alan Arthur. 1881-1885. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Five things you may not know about Chester Arthur appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFive things you may not know about Jimmy CarterThe first woman senatorImages from Broadway’s past

Related StoriesFive things you may not know about Jimmy CarterThe first woman senatorImages from Broadway’s past

October 4, 2013

A medieval saint in modern times

Saint Francis of Assisi died on this day in 1226, and when he was canonized just two years later, the fourth of October became his feast day. Even before his sainthood was official, St Francis was a popular figure among the faithful, and the religious order he had founded already had chapters throughout Europe. The troubled medieval papacy, keen to co-opt Francis’s popularity, fast-tracked his canonization, commissioned an official biography (while censoring previous versions), and constructed and decorated a monumental church dedicated to him in his hometown in the central Italian region of Umbria.

Interior of the basilica of San Francesco in Assisi. Photo by Ugo franchini at it.wikipedia, published under the GNU Free Documentation License via Wikimedia Commons.

San Francesco in Assisi, the saint’s burial site, was decorated extensively with frescoes by the leading Italian painters of the late 13th and early 14th centuries, including the most complete visual narrative of the saint, the so-called Legend of St Francis cycle in the Upper Church (San Francesco has an unusual design with two main spaces – the Lower Church houses Francis’s tomb). These frescoes, to which Giotto probably contributed, tell how the young Francis abandoned his life as a wealthy playboy and adventuring soldier. He gave up all his worldly possessions, fixed up some dilapidated churches in Assisi, and began wandering from town to town, preaching and begging. He soon had a following, and he received official sanction for his order when Pope Innocent III approved his rule (the tenets by which the Franciscan friars lived) in 1209. The frescoes at Assisi also depict episodes representing the Franciscan vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience – such as Francis giving his coat to a poor beggar and kneeling before the pope who had just confirmed the Franciscan rule. The paintings also demonstrate Francis’s holiness, depicting numerous miracles and his stigmatization – the miraculous appearance on his body of the wounds Christ suffered during the Crucifixion.

St Francis receiving the stigmata is one of the most common depictions of the saint, but the image of St Francis as a lover of animals is likely very recognizable to the general public. You’ve probably seen one of those little garden statues of a monk in a long hooded robe with some birds perched on him – that’s our guy! These make reference, like the fresco from the Assisi cycle (below) to an episode in Francis’s life recorded in several of his early biographies, including the Little Flowers of St Francis. While out walking with some other friars, he came upon a flock of birds that were chirping and twittering loudly. He decided to preach to them, and they fell silent and listened, flying away only when he had finished his sermon and given them his blessing. This charming scene stands for a broader theme of Francis’s devotion to and reverence for all of God’s creation.

Legend of St Francis: 15. Sermon to the Birds. Between 1297 and 1299. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The visual and literary traditions documenting St Francis’s life have kept his ideas alive nearly eight centuries after his death. As part of the feast day celebrations, which have branched out into different religions, some faithful bring their pets or livestock to church or synagogue for the blessing of the animals. The fourth of October is also World Animal Day, an interfaith, international holiday, raising money for animal and ecological causes. St Francis’s legacy also lives on with Pope Francis I. Since he was elected just over six months ago, he has been making quite a splash, in part by showing a dedication to the teachings of his namesake. He has suggested that Catholics redirect their attention toward the church’s mission of helping the poor, and has spoken about the Christian basis for environmental stewardship.

Kandice Rawlings is Associate Editor of Oxford Art Online, historian of Italian Renaissance art, and cat owner.

Oxford Art Online offers access to the most authoritative, inclusive, and easily searchable online art resources available today. Through a single, elegant gateway users can access — and simultaneously cross-search — an expanding range of Oxford’s acclaimed art reference works: Grove Art Online, the Benezit Dictionary of Artists, the Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, The Oxford Companion to Western Art, and The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms, as well as many specially commissioned articles and bibliographies available exclusively online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only art and architecture articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A medieval saint in modern times appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBack to (art) schoolJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneIn the buff: a classical view of National Nude Day

Related StoriesBack to (art) schoolJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneIn the buff: a classical view of National Nude Day

The precarious future of ocean megafauna

Being an enormous, hulking beast has long been an effective defense mechanism. The plains and forests of North America were once teeming with colossal creatures like giant ground sloths and woolly mammoths, behemoths that plodded along safe in the knowledge that few predators would dare challenge them. But once prehistoric humans crossed the Beringia land bridge at the end of the Pleistocene, it was the largest animals that found themselves at the top of the kill list. Humans, armed with tools and complex hunting strategies, were well-equipped to take on these giants. And since one woolly mammoth carcass could feed a village for weeks, why bother wasting time with bite-sized squirrels or meager groundhogs? Being enormous, which was once these species’ greatest asset, was now their greatest liability. And so, 10,000 years ago, our ancestors hunted the great North American megafauna to extinction.

We face a similar situation today. But this time, we’ve turned our attention to the ocean megafauna. Our great-grandfathers began targeting the largest whales first, hunting most species to near extinction. When 18th century European traders first happened across the nine meter long Steller’s sea cow along the coastlines of the Pacific North West, they finished what the aboriginal hunters had begun, slaughtering the very last of these gentle giants just 27 years after first setting eyes on them. But it’s not just aquatic mammals that we pursue without mercy. Our modern fishing methods have allowed us to pull giant tuna species out of the ocean by their millions. A global taste for sushi has reduced bluefin tuna numbers in the Northern Pacific by 96%. Their rarity means that a single bluefin tuna can now sell for over $1.5 million.

Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) ensnared near the mouth of the fish trap. Public Domain, courtesy of United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.

It seems that any sea creature that has the unfortunate trait of growing larger than the size of a coffee table is destined to run afoul of humanity. Manatees, sharks, manta rays, sailfish, sea turtles — the bigger the beast, the bigger our desire to kill it, eat it, stuff it, and mount it. And even when not hunting them on purpose, ocean megafauna are, due to their size, at serious risk of being pummeled by boat and shipping traffic or inadvertently drowned in fishing nets.

The IUCN Red List shows the extent of our thirst to exploit ocean megafauna. One third of pelagic sharks species are threatened with extinction — due almost exclusively to overfishing. This includes some of the largest of all shark species, including basking sharks, great white sharks, and great hammer head sharks. “Despite mounting threats, sharks remain virtually unprotected on the high seas,” says Sonja Fordham, Deputy Chair of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group. The demand for shark products, including shark fins for use in soup, has increased shark slaughters by 400% in the last 50 years. With shark fins selling for up to $256 per pound, and a single whale shark fin fetching up to $15,000, it is the largest shark species that bear the brunt of our insatiable appetite.

Ocean dwelling reptiles aren’t safe either. Of the seven marine turtle species alive today, five are listed by the IUCN as either “endangered” or “critically endangered.” The largest species, the leatherback turtle, can reach 1.8 meters in length and weigh over 500kg. But its bulk makes it vulnerable to entanglement in fishing nets, and its eggs are still collected and eaten in some areas of the world. Fishing nets pose a serious threat to many of the larger marine mammal species, with 70% of critically endangered North Atlantic right whales having been entangled in nets at least once in their lifetime. Entanglements and ship collisions are making it impossible for this species — numbering approximately 400 individuals — to claw their way back from the brink of extinction. Their enormous size, which once protected them from predators, will ultimately be their downfall.

It is entirely possible to cease the exploitation of ocean megafauna. There are campaigns to stop shark finning, protect endangered dolphin and whale populations, cease over-fishing, etc. It is not too late to reverse the current trends. So on this World Animal Day, why not pick a cause and a species that most excites you and get involved in the fight to preserve these ocean giants. Let’s not let animals like tuna, right whales, and great white sharks slip quietly into the history books alongside the sea cows and mammoths.

Justin Gregg is the author of Are Dolphins Really Smart? The Mammal Behind the Myth. He is a research associate with the Dolphin Communication Project, and Co-Editor of the academic journal Aquatic Mammals. He received his doctorate from Trinity College Dublin in 2008, having studied social cognition and the echolocation behavior of wild Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. With an undergraduate background in linguistics, Justin is particularly interested in the study of dolphin communication as it pertains to comparisons of human (natural) language and animal communication systems.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The precarious future of ocean megafauna appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHappy 60th Birthday: The science that makes transplantation workThe first ray gun

Related StoriesHappy 60th Birthday: The science that makes transplantation workThe first ray gun

The economics of cancer care

To mark Breast Cancer Awareness Month this October, here is an extract from Cancer: A Very Short Introduction by Nick James.

Around 40% of [cancer] patients develop advanced cancer at some stage, most of whom will ultimately die from the disease. New drugs are generally tested initially in this group of ultimately incurable patients with limited options. In breast cancer, for example, only a minority of patients die from the disease and hence expenditure on a newly licensed, end-stage drug will be relatively limited. However, if a drug works well in this group, it will often work better in earlier patients with potentially curable disease at high risk of relapse after their initial therapy. This group makes up around half of the patients who end up with advanced disease. Trials of successful end-stage drugs will thus take place in these patients and if successful the drug will ‘migrate’ into the earlier disease group.

This process is well illustrated by the Herceptin (trastuzumab) story. The drug was shown to prolong survival in advanced breast cancer in 2002. From the beginning, Herceptin has attracted huge publicity. The novel nature of the treatment rapidly became known amongst breast cancer patients leading to a clamour to enter the trials. So great was the demand that a lottery for trial entry had to be set up for interested eligible patients. After the drug obtained a licence, its high price (around £30,000 per year) led to restricted access in the UK and a different sort of lottery – the post-code lottery of UK cancer funding – began for a different group of women. The subsequent highly vocal campaign by women successfully overturned the restrictions but also set a precedent for other groups seeking access to expensive therapies that still bedevils purchasing authorities in the UK in particular.

Subsequent trials in earlier disease showed in 2006 that if given to women with early high-risk disease after surgery, Herceptin reduced the chances of a disease recurrence by about half compared to previous therapies. The licence for Herceptin was thus extended to this earlier disease group the same year. Unfortunately, we cannot currently identify those who will relapse after surgery and radiotherapy. As most women in the early, high-risk group were already cured by standard therapy, the numbers eligible to receive the drug increased hugely (about four-fold in the UK) – all patients at risk have to be treated, not just those destined to relapse. Following a vocal campaign by women with the disease, the drug was made available on the NHS to all eligible patients.

How, therefore, do healthcare systems make decisions about new treatments? Suppose a new treatment costs £30,000 and improves survival by 6 months, from 12 to 18 months. What is the real cost of providing this treatment?

£30,000?

£30,000 minus the treatment it replaces?

£30,000 minus the treatment it replaces and minus any consequent savings in other supportive care?

There is no correct answer — it depends on who is paying for what. Answer 1 is the cost to the patient if the treatment is not reimbursed by the healthcare system. This is sometimes the case in the UK where the NHS sets limits on which drugs it will buy. The old standard of care will be covered but not the new drug. Increasingly, it is also a problem for patients in insurance-based systems where the extra drug falls outside the reimbursement package covered by the insurance. Answer 2 is the price to a hospital providing specialist care where the hospital budget per patient is fixed (as happens in hospitals in the NHS and some managed-care systems in the USA). Answer 3 is the price to the organization funding the totality of the patient’s care: this may be the state via structures like the NHS or an insurance company. This then raises the further question of what exactly is included in the associated costs. For example, terminal care costs will probably be similar whenever a patient dies. However, if the survival time is longer, as in the example, they may then fall in a different financial year to the drug costs – how long must costs be deferred to count as savings? This is particularly the case with treatments which increase the cure rate, for which such costs may be postponed for many years. Again, there is no single simple answer to such questions – different healthcare systems tend to resolve these dilemmas in different ways. It is worth examining the sort of methodologies used by public health specialists and insurance companies in making these decisions on whether to fund a particular treatment.

Nick James is the co-founder of the CancerHelp UK website, author of Cancer: A Very Short Introduction, and Professor of Clinical Oncology at the University of Birmingham.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS

Image credit: By Federal Government [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post The economics of cancer care appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe first woman senatorFine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patientHappy 60th Birthday: The science that makes transplantation work

Related StoriesThe first woman senatorFine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patientHappy 60th Birthday: The science that makes transplantation work

October 3, 2013

The first woman senator

By Donald A. Ritchie

While I was racing through the tunnels that link the concourses at Atlanta’s Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, trying to make a tight connection, faces of famous Georgians adorning the walls flashed by. Among them I spotted Rebecca Latimer Felton and wondered how many other travelers might recognize her as the first woman to serve in the United States Senate. Not that her term lasted all that long. When the governor appointed her on 3 October 1922, the Senate was not in session. By the time it convened in November, an election had taken place that chose her successor. Nevertheless, Felton managed to get sworn in as a senator and deliver a speech in the Senate Chamber. Photographs of her at the time show a very elderly lady–she was 87–on the steps of the Capitol. Does she deserve to be memorialized at the airport or remembered at all?

Rebecca Felton. Public domain via U.S. Senate Historical Office.

Born near Decatur, Georgia, in 1835, Rebecca Latimer graduated from Madison Female College and married William Felton, a doctor and Methodist minister. During the Civil War they lost their home and both of their children to disease and depravation. They rebuilt their lives and in 1874, William Felton won election to the House of Representatives. Rebecca Felton accompanied him to Washington as his secretary and clerk, and also publicly campaigned for his reelections–first as a Democrat and then as a Populist. She was so fiery on the political hustings that a newspaper editorial asked “Which Felton is the Congressman and Which the Wife?”

Holding strong opinions, she never hesitated to express her mind in public as a lecturer and for thirty years as a columnist for the Atlanta Journal. She crusaded against the use of convict labor and for temperance, compulsory school attendance, and women’s rights–most of all the right to vote. Identifying herself as an “independent Democrat,” she was a Georgia delegate to the national convention of Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party in 1912. She often stood against the culture of her times, although not in matters of race. Historians have found her to be a complicated political figure who combined “progressive gender reform” with “reactionary race politics,” and noted that her calls for reform were always tainted by white supremacy. After she was widowed in 1909, she remained politically active, particularly promoting woman suffrage.

In September 1922, Georgia Senator Thomas E. Watson died, and Governor Thomas Hardwick, who planned to run for the vacant seat, made a calculated effort to attract women voters by appointing a woman to fill the vacancy. Watson’s widow rejected his first offer, and he turned to Rebecca Felton. Since the Senate was not due back into session until December, Hardwick expected the appointment to be purely ceremonial. The maneuver did not help, however, and Hardwick lost the Senate race to Walter George on 7 November.

Mrs. Rebecca L. Felton being greeted by prominent political women in Washington, D.C., November 20 1922. Public domain via the Library of Congress.

Meanwhile, across the nation women demanded that Felton be sworn into office. That opportunity came when President Warren G. Harding called Congress into special session on 21 November to deal with ship subsidy legislation. Although Walter George’s term began as soon as he was elected, Rebecca Felton traveled to Washington to claim the Georgia Senate seat, having persuaded George to wait a day to present his credentials. Other senators privately fretted over the constitutionality of seating an appointee after her successor had been duly elected. Felton had prepared two speeches, one to make outside the Capitol in case she was rejected, the other to make in the Senate Chamber in case she was seated. As it turned out, no man wanted to oppose her publicly, so she was able to take the oath of office on 21 November. The next day she rose in the chamber to deliver a short but memorable speech.

After thanking the gentlemen for offering a lady a chair, Senator Felton assured her colleagues that she was just the first of the women who would join them. “Let me say, Mr. President,” she concluded, “that when the women of the country come in and sit with you, though there may be but very few in the next few years, I pledge you that you will get ability, you will get integrity of purpose, you will get exalted patriotism, and you will get unstinted usefulness.” The public galleries, filled with activists from the National Woman’s Party and other groups, cheered her remarks. With that, Rebecca Felton ended her short term as a United States senator.

When she died in 1930 there were still no other women senators, but today a record twenty women are serving as senators. Rebecca Felton would likely ask why there aren’t more. For leading the way, she earned that spot at the Atlanta airport.

Donald A. Ritchie is historian of the US Senate, where he conducts an oral history program. A past president of the Oral History Association, he has also served on the councils of the International Oral History Association and the American Historical Association. He is the author of many books, including Doing Oral History: A Practical Guide (OUP, 2003), Reporting from Washington (OUP, 2005) and The U.S. Congress: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2010). He is also the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Oral History (OUP, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The first woman senator appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesImages from Broadway’s pastFive things you may not know about Jimmy CarterThe price of free speech

Related StoriesImages from Broadway’s pastFive things you may not know about Jimmy CarterThe price of free speech

Images from Broadway’s past

In Anything Goes, Broadway historian Ethan Mordden takes us on a tour of the history of Broadway musicals over the past 100 years. From classical shows such as the 1903 production of The Wizard of Oz, to Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II’s original production of Showboat, and leading right up to Bernadette Peters’s recent turn in the 2011 production of Follies, take a tour of the evolution of the musical through the years and “all that jazz” that is has captivated audiences for ages.

Rather Be Right

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

George M. Cohan as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in I’d Rather Be Right was the outstanding headliner musical of the 1930s. Cohan treats the show’s sweethearts (Austin Marshall, Joy Hodges) to a snack in Central Park. ROOSEVELT: This is the way I like to eat ice cream. At the White House, we have to have [Vice-President John Nance] Garner with it.

Anything Goes

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Ethel Merman leads the cast in “Blow, Gabriel, Blow.” (Note “Gabriel” tooting at rear.)

Vagabond King

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Before Alfred Drake (from the 1940s on) and Robert Preston (from the 1950s), the musical’s male stars were comics. One exception was the singing Shakespearean Dennis King. Playing the beggar-poet François Villon in The Vagabond King, he has been bathed, groomed, and perfumed for presentation at court (here with pompous courtier Julian Winter).

The Wizard of Oz

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The Star Comic. Irish-accented Bobby Gaylor sings “On a Pay Night Evening” in the title role of The Wizard of Oz, way back in 1903.

Jumbo

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Big Rosie and Jimmy Durante in Jumbo, in 1935. By then, minority-group stereotype humor was losing traction; Durante’s persona, as a proletarian Noo Yawk rogue, was social rather than ethnic.

Bells Are Ringing

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The First Couple. Boy Meets Girl in Bells Are Ringing (Judy Holliday, Sydney Chaplin).

Seventeen

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Boy Gets Girl in Seventeen (Kenneth Nelson, Ann Crowley) as the cast reprises the big ballad, “After All, It’s Spring.”

I Married An Angel

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

I Married Angel’s Second Couple (Walter Slezak, Vivienne Segal, right) is truly offbeat, as soigné cutups of Budapest. They’re old flames reunited. SLEZAK: You’ve been waiting for me for fifteen years?...Didn’t you get married? SEGAL: A little. Only four times.

Show Boat

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The first-act finale, as Parthy Ann Hawks discovers her incipient son-in-law is a murderer. Left to right, boat captain Charles Winninger, fiancés Howard Marsh and Norma Terris, Second Couple Sammy White and Eva Puck again, a pointing Edna May Oliver, sheriff Thomas Gunn, evil whistleblower Bert Chapman. Note the error above; it should be “Hawks’ Cotton Blossom.”

Porgy and Bess

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After Show Boat, there was nowhere to go but opera, in George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, seen as Catfish Row departs for the picnic on Kittiwah Island in “Oh, I Can’t Sit Down.” First Couple Todd Duncan and Anne Brown at far right.

Ethan Mordden is a recognized authority on the American musical, and the author of such books as Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre, Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s, Beautiful Mornin: The Broadway Musical in the 1940s, and Coming Up Roses: The Broadway Musical in the 1950s. He lives in Manhattan.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: All images in the public domain. Source: Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre.

The post Images from Broadway’s past appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBreaking Bad’s Faustian CastThinking through comedy from Fey to FeoEp. 3 – DRAMA

Related StoriesBreaking Bad’s Faustian CastThinking through comedy from Fey to FeoEp. 3 – DRAMA

Happy 60th Birthday: The science that makes transplantation work

Sixty years ago today, the world’s top science journal Nature published an article just 3½ pages long, which won a Nobel Prize for its lead author Peter Medawar and more importantly put doctors on the right path for making transplantation surgery the life-saver that it is today. Up until that point, the idea of using one person’s body parts to save the life of another was little more than a fanciful idea in science fiction. Some mavericks had claimed success in transplantation; they were perhaps lucky once but more likely, they were lying. The thinking at the time was that doctors just needed to work out the right surgical procedure to get transplantation to work. But they were wrong; Medawar’s landmark 3½ pages in Nature showed that whatever the actual procedure — even if the cutting and sewing was perfect — the transplantation would usually still fail. There’s a fundamental aspect of human biology that causes human tissue to be rejected when moved from one person to another. Medawar’s 3½ pages in Nature showed a way in which the problem could be solved.

Seeing the agony of airmen suffering from drastic skin burns at a War Wounds Hospital in Oxford in 1940 focused Medawar’s mind on solving the transplantation problem. “A scientist who wants to do something original and important must experience, as I did, some kind of shock that forces upon his intention the kind of problem that it should be his duty and will become his pleasure to investigate,” he said later.

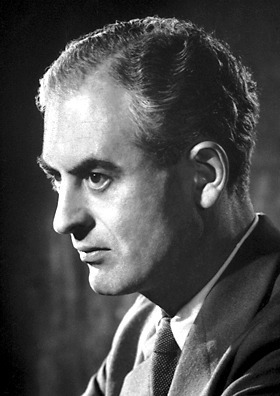

Peter Medawar, 1960. Public domain via Wikimedia commons.

From the moment he witnessed the hospital scene, Medawar ‘worked like a demon’, according to his wife Jean. Through careful observations of patients (and experiments on animals) he set out to examine — more carefully than anyone previously — what happened when skin was grafted from one person to another (or between animals). One breakthrough observation he made was when the same patient needed a second skin graft. He noted that if the second transplant used skin from the same (unrelated) donor as the first transplant, then this second graft was rejected very quickly. This kind of rejection is the hallmark of an immune system reaction; the recipient’s immune cells could recognise the graft as being like the one before and attacked it rapidly. It’s the same with say, the flu virus; when you recover from flu, you’ll be strong at fighting the same flu virus again, but not a different version of flu or some other virus. This with other observations he made amounted to unequivocal evidence that a reaction from the recipient’s immune cells caused graft rejection. He showed that transplantation wasn’t just about getting the surgery right; fundamentally it was a problem caused by an immune reaction. This shifted everyone’s thinking onto the right path.

Even so, this was still merely a prelude to his seminal experiment reported in those 3½ pages in Nature — published just a few months after Watson and Crick famously presented the iconic double helix structure of DNA in the same journal. In these few pages Medawar gave us a way to solve the problem of transplantation. That is, he found a way to transplant skin from one animal to another so that it would not be rejected — there would be no immune reaction at all — even if the animals were unrelated.

Medawar — with his research team of two others, Rupert Billingham and Leslie Brent — injected cells from one type of mouse into unborn foetal mice. They discovered that after birth, when tested as adults, the injected mice were able to accept skin from the unrelated mouse strain whose cells had been injected. Medawar’s wife, Jean, dubbed the treated mice ‘Super-mice’. These were startling results; the problem of transplantation had a solution. The Super-mice had become tolerant to skin grafts from unrelated mice whose cells they had been exposed to when foetuses. The implication was that, early in life, the immune system learns to not attack our own cells and tissues.

At first, Medawar would often deny that his research had any direct medical implications because his research didn’t reveal a method for human transplantation. His way of circumventing the natural barrier to transplantation had only been shown to work with young animals and he was cautious about claiming too much medical significance for his basic research. But in time, it became clear that transplantation would become a life-saving surgical procedure. Although his way of solving the difficulties in transplantation could not be a routine procedure for humans, the research began a sixty year-long adventure, involving thousands of scientists, in understanding our immune system. The details cannot be paraphrased with suitable brevity here, but genetic matching between people and the use of immune suppressive drugs make clinical transplantation a life-saving reality, and both directly build upon Medawar’s insights.

Happy 60th Birthday to these ground-breaking experiments that proved to be of exceptional medical importance — and changed the way we understand the human body.

Daniel M. Davis is currently a Professor of Immunology at the University of Manchester, UK, where he is the Director of Research at the Manchester Collaborative Center for Inflammation Research. He is the winner of the Oxford University Press/Times Higher Education Supplement Science Writing Prize (2000). He is the author of The Compatibility Gene: How Our Bodies Fight Disease, Attract Others and Define Ourselves.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Happy 60th Birthday: The science that makes transplantation work appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFeral politics: Searching for meaning in the 21st centuryThe first ray gunSagan and the modern scientist-prophets

Related StoriesFeral politics: Searching for meaning in the 21st centuryThe first ray gunSagan and the modern scientist-prophets

In the footsteps of the fashionable world

Each autumn, throughout the 1700s, London’s West End was transformed. Previously quiet squares were populated again, first by servants and tradesmen. After the houses were readied, their employers journeyed to the capital from their country estates between October and January. Snow, noted one observer, ‘brings up all the Fine folks [to London], flocking like half-frozen birds into a Farm-yard, from the terror…of another fatal month’s confinement…in the country’. For them, the business and pleasures of the coming months were varied. Parliamentary machinations preoccupied many. Social networks also had to be rewoven, and plans for the hectic round of visits and balls drafted. London was a pool of potential suitors for lords and ladies coming of age, and so prospective spouses were researched and courted. A family’s political, genealogical and financial fortunes might be secured by a shrewd match or devastated by an impulsive misalliance. At the root of this sometimes frenzied seasonal activity was one ambition: to secure or reaffirm membership of a new elite – the beau monde – the so-called ‘world of fashion’.

London’s West End was once the heartland of this glittering and frenetic world. Much of the fashionable world’s original footprint has disappeared, replaced by department stores, bus routes, tube stops, and apartment buildings. There are, however, a few places where the ghosts of the beau monde can still be found.

A smart address was essential for anyone in fashionable society. Spencer House, built in 1755-56 for John, 1st Earl Spencer (and still owned by the Spencer family today) is a rare survivor of the urban palaces that once accommodated elite families during the season – most were sold to developers in the twentieth century. Moreover, Spencer House retains much of its original eighteenth-century interior. Other examples of the decoration of such properties can be seen at the V&A, where the Norfolk House music room and sections of Northumberland House’s drawing room testify to the massive investment involved. Meander around the West End and the street names alone – Bedford Square, Portland Square, Grafton Street, Marlborough Street, Grenville Street – conjure a vanished world of aristocratic living.

2. Drury Lane Theatre and King’s Theatre Haymarket

Theatre and opera attendance was central to fashionable life. Drury Lane staged daily performances ranging from Shakespeare to new comedies of manners. An evening’s schedule could run for five hours, with prologues, epilogues, sung performances, and even additional short plays besides the headline show. Opera was performed at the King’s Theatre (on the site of what is now Her Majesty’s Theatre, Haymarket). Attracting performers from around Europe, it was a key fixture for the beau monde.

An Audience Watching a Play at Drury Lane Theatre by Thomas Rowlandson [public domain]

Attending these venues just once did not cut it. Fashionable society subscribed to boxes and attended repeatedly every week. For them, stage performances were rarely the draw; what counted were the social performances of the audience. The Hon. Frederick Robinson, for example, bemoaned that while the opera was ‘long and dull and the dances bad… I also go as I am sure to meet all my acquaintance’.In the eighteenth century, the land to the east of Chelsea Royal Hospital was a pleasure garden open to evening visitors in the spring and early summer. Ranelagh Gardens had opened in 1742, in direct competition to its famous predecessor Vauxhall Gardens. With tree-lined promenades, music, singing, fireworks and masquerades, the entertainments on offer at Ranelagh were modern and varied. Its principal innovation, however, was a dramatic rotunda – ‘a vast amphitheatre, finely gilt, painted and illuminated into which everybody that love eating, drinking and staring is admitted’. The Rotunda has long gone but you can still promenade down one of the garden’s original tree-lined walks. Squint a bit and you might glimpse Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, a few yards ahead.

The Rotunda at Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea near (now in) London by Thomas Bowles, 1754 [public domain]

4. SpitalfieldsA fine wardrobe was essential to the fashionable set. For men and women the most important and expensive clothing was that worn to court. Spitalfield’s silk-weavers spent months producing the sumptuous fabrics required, adorned with diamonds and embroidery. Settled by Huguenot refugees in the 1680s, Spitalfields was home to London’s silk industry. The royal family visited the district to promote its trade, and to advertise their insistence that only silks woven in England should be worn at court.

A mantua or court dress, 1740-1745. Photo by Gryffindor [CC-BY-SA 3.0]

5. I am The Only Running FootmanLife for the beau monde could not be managed without an army of supporting staff, from pastry chefs to rat catchers. The liveried servants, though, had the plum posts. Well-paid and well-dressed footmen accompanied their employers around town. Besides the occasional errand, a footman’s principal role was to look the part. Tall, handsome and fit, a team of young footmen on your carriage was the ultimate fashionable accessory. One such footman established this Mayfair pub, ‘The Only Running Footman’, in the early 1800s. Located near Berkeley Square, it sits surrounded by the grand streets that once housed the beau monde and their entourages.

Hannah Greig is a lecturer in eighteenth-century British history at the University of York. Prior to joining York she held posts at Balliol College, Oxford, and the Royal College of Art. Alongside her academic work, Dr Greig works as a historical adviser for film, television, and theatre. Recent credits include the feature film The Duchess (Pathe/BBC films 2008, directed by Saul Dibb) and Jamie Lloyd’s production of The School for Scandal (at the Theatre Royal in Bath). She is the author of The Beau Monde: Fashionable Society in Georgian London.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) An Audience Watching a Play at Drury Lane Theatre by Thomas Rowlandson [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons; (2) The Rotunda at Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea near (now in) London by Thomas Bowles, 1754 [public domain] via Wikimedia Commons; (3) A mantua or court dress, 1740-1745. Photo by Gryffindor [CC-BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In the footsteps of the fashionable world appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneThe pleasure gardens of 18th-century LondonWhy is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

Related StoriesJudging a book by its cover: recordings, street art, and John ColtraneThe pleasure gardens of 18th-century LondonWhy is Gandhi relevant to the problem of violence against Indian women?

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers

![The Rotunda at Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea near (now in) London by Thomas Bowles, 1754 [public domain]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1380927574i/3321398._SX540_.jpg)