Oxford University Press's Blog, page 900

September 24, 2013

Politics, narratives, and piñatas in health care

Obamacare has been like the title character in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot: everyone talks about it but it never arrives. It is finally about to make its entrance. On 1 October 2013, all 50 states and the District of Columbia will open health insurance marketplaces (sometimes called “exchanges”) for people who aren’t covered by their employer or a government program. In these online marketplaces, insurers won’t be allowed to discriminate based on pre-existing conditions. On 1 January 2014, the law will begin subsidizing health insurance for millions of people — everyone between 100% and 400% of the poverty level. (The Supreme Court gave states the power to block the statute’s intended free medical care for their residents who were below that threshold, and many of them, in one of the nastier developments in recent American politics, have done so.)

This will have a dramatic effect on the politics of health care. Until now, the Republicans have been able to continue to use Obamacare as a political piñata. It’s complicated and poorly understood, and so they’ve been able to attach to it any derogatory label that they like. The House of Representatives has voted to repeal it so many times that it’s amazing that they ever manage to do anything else. Now, for huge numbers of voters, Obamacare will become easy to understand: it will be the reason why they can afford health care. Other government programs are complicated. It takes an expert to understand the details of Social Security, but most people know what it means to them. Obamacare will become like that.

It’s hard to predict what will happen to the Republicans’ narrative of Evil Obamacare in the face of these realities. Their opposition to the law was crystallized in their constitutional challenge to the law. They are now closely tied to a narrative that looks pretty nasty if you think about it.

Universal health insurance logically means that everyone has to have insurance. Yet the lawyers who challenged the Affordable Care Act (ACA) argued, on the basis of a strange notion of liberty, that this requirement — that everyone has to carry insurance — was an intolerable imposition. Call it Tough Luck Libertarianism. The challengers read into the Constitution the notion that the law’s trivial burden was intolerable, even when the alternative was a regime in which millions were needlessly denied decent medical care. Their Constitution is one in which, if you get sick and can’t pay for it, that’s your tough luck.

Since then, in their repeated attacks on Obamacare, they have continued to rely implicitly on what I’ve called Tough Luck Libertarianism. They haven’t had to take responsibility for that because the people whom their approach would hurt haven’t even known that they and their families were being threatened. The most politically maladroit aspect of Obamacare was the long delay in its implementation. Now, however, we’re in a different world. Once I know that I’m getting subsidized insurance, I’m likely to get mad if you try to take it away from me.

I don’t expect the Republicans to recant their views. They are so committed to eradicating Obamacare that they might shut down the federal government. But as public opinion shifts, they won’t be able to keep that up. What will happen will look a lot like what has happened with gay rights: the theme slowly becomes fainter and fainter, until you can’t hear it at all any more. This war, like that one, is essentially over. It doesn’t mean, however, that there won’t be some nasty fights in the endgame.

Andrew Koppelman is John Paul Stevens Professor of Law, Northwestern University. His books include The Tough Luck Constitution and the Assault on Health Care Reform, Defending American Religious Neutrality, A Right to Discriminate?, and The Gay Rights Question in Contemporary American Law.

This week we’re offering views and insights from Oxford University Press authors on the Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act in anticipation of open enrollment beginning on 1 October 2013. Read yesterday’s article by Theda Skocpol and Lawrence R. Jacobs: “What does health reform do for Americans?”.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Medical Stethoscope on folded American Flag for US Health Care concepts. © jcjgphotography via iStockphoto.

The post Politics, narratives, and piñatas in health care appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat does health reform do for Americans?Give peace a chance in SyriaThe Gold Corner

Related StoriesWhat does health reform do for Americans?Give peace a chance in SyriaThe Gold Corner

The Gold Corner

One of the more audacious trading operations in Wall Street history occurred in September 1869. The “Gold Corner” as it quickly became known, involved nothing less than an attempt to force up the price of gold using the resources of the United States government in the process. The mastermind behind the operation was the equally audacious Jay Gould.

Jay Gould, American financier. Photograph by Bain News Service. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The trading operation caused havoc on Wall Street. Previous attempts at “cornering” a stock or commodity future usually involved a speculator gaining access to a large amount of the available supply of the security or commodity and then running its price up before selling at a profit. But gold was different because of the large quantity held by the government at Ft. Knox.

Jay Gould was best known for his involvement with the Erie Railroad and had already become something of a legend in Wall Street circles. He maintained vast political connections, notably with Boss Tweed and the Tammany Hall gang that controlled New York City politics. But in order to corner the gold market, his connections would have to be higher and better placed. The United States Treasury held $100 million in gold at Fort Knox that it would frequently use to stabilize the gold market. Any attempt to corner the price depended upon the Treasury remaining away from the market. If it decided to intervene, or was tipped as to Gould’s intentions, the cornering operation would come undone. What Gould needed was nothing less than the ear of a compliant Ulysses S. Grant. In order to get within shouting distance of Grant, he decided to employ the banking house of Seligman and its long standing Washington connections.

Gould started accumulating about $7 million worth of gold and forced the price to a premium of over 140%. He was joined in the operation by Jim Fisk, a colleague at Erie, and Daniel Drew, another well-known speculator and railway financier. Then with the aid of rumor he helped force the price in excess of 160%. This forced the bears, those who believed the price would not rise, to begin covering their short positions, helping the price to remain firm at slightly over 160. The terrifying prospect of losing everything forced many bankers, including Jay Cooke, the best known Wall Street figure of the day, to implore Grant to intervene in the market. They finally convinced him that the price rise was nothing more than a ploy by speculators.

The Treasury entered the market in several days, adding to the gold supply, hoping to break the corner. The price began to fall and within an hour it had fallen 30%. But the next day, the financial community was in chaos. Several large and respected Wall Street firms failed.

Gould made a killing from the cornering operation. He sold most of his gold positions at the top of the market and made an estimated $10 million for his efforts. The Seligmans joined him in the profits. For years, it has been assumed that they were tipped before the Treasury entered the market and most fingers have pointed at Grant himself. No evidence has ever surfaced that the President forewarned his old friends the Seligmans of the impending stabilization operation although he has been suspect ever since. Others involved in the stabilization operation could easily have informed him. One of Gould’s cohorts in the operation was Abel Corbin, Grant’s son-in-law. Most insiders assumed that he initially used Corbin to keep Grant from ordering an intervention. Finally, the president was persuaded to intervene by the bankers and the selling panic quickly followed. But Gould would not escape the operation totally unscathed. He had angered too many people. He had not warned his partner Fisk in time and Fisk did not profit from the operation as he and the Seligmans did. When news of the gold corner was finally made public, Gould was attacked by an angry crowd in New York and barely escaped with his life. Thereafter, he always travelled with a bodyguard, even when he took an evening walk from his home on Fifth Avenue.

The fallout on Wall Street was predictable. The stock market collapsed on 24 September 1869 and the day became known as ‘Black Friday.’ Dozens of brokers failed as a result. This proved to be particularly inauspicious for the New York Stock Exchange, which had formally changed to its current name during the Civil War. Many of the stronger bankers, including Jay Cooke, mounted rescue operations to save others who were tottering on the brink. The shake-out did nothing to enhance the reputation of the exchange which had been in the forefront of Gould’s other manipulations for some time.

Gould recognized the link between the price of gold and commodities prices. A year after the gold corner, he was called to testify before a Congressional hearing looking into the corner. When asked about the operation, Gould replied in terms that traders understood:

“I went in with a view of putting gold up. At the time, the fact was established that we had an immense harvest and that there was going to be a large surplus of breadstuffs, either to rot or be exported… I found that with gold at [a premium of one hundred] 40 or 45, Americans would supply the English market with breadstuffs; but that it would require gold to be at that price to equalize our high price labor… with gold below 40 we could not export but with gold above 45 we would get the trade.”

Arguing that he was helping exports did not necessarily convince Congress that his motives were patriotic but it clearly demonstrated that Gould was well aware of the factors that made commodities prices and precious metals move in tandem.

Charles R. Geisst is Ambassador Charles A. Gargano Professor of Finance at Manhattan College, and the author of many books, including Wall Street: A History, Collateral Damaged: The Marketing of Consumer Debt to America, and Beggar-Thy-Neighbor: A History of Usury and Debt.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The Gold Corner appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901What does health reform do for Americans?The whale that inspired Greenpeace

Related StoriesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901What does health reform do for Americans?The whale that inspired Greenpeace

What is atonal? A dialogue

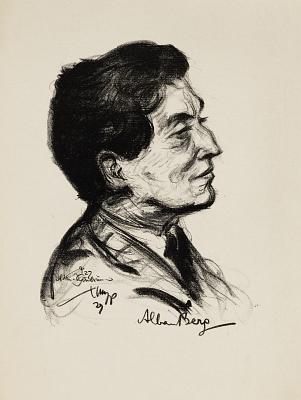

Viennese composer Alban Berg played a major role in the transformation of serious music as it entered the modern period. He was also a skilled, analytic writer, whose essays, lectures, and polemics provide a unique perspective on classical music in transition. A new English edition of his Pro Mundo – Pro Domo. edited by Bryan R. Simms, contains 47 essays, many of which are little known and have not been previously available in English. Below is a brief extract from one of his dialogues with critic Julius Bistron.

Docent [Julius] Bistron: So, my dear Meister Berg, let’s begin.

Alban Berg: You start, Professor, I’m happy to have the last word!

Alban Berg: You start, Professor, I’m happy to have the last word!

Bistron: You’re that sure of the matter?

Berg: As sure as a person can be about an issue in whose development and growth he has participated for a quarter century, with a certainty that comes not only from reason and experience but, even more, from belief.

Bistron: Good. It would probably be simplest if I first pose the title question of our dialogue: “What is atonal?”

Berg: It is not easy to answer this by a formula that could also serve as a definition. Where this expression was first used—apparently in a newspaper critique—it probably was, as the compound form of the term [a-tonal] clearly implies, a designation for music whose harmony did not comport with the traditional laws of tonality.

Bistron: So you mean in the beginning was the word, or, better, a word that compensates for the helplessness we feel when confronted with something new.

Berg: You might say that. But it is certain that this term “atonal” was used with a pejorative intention, just as terms like “arrhythmic,” “amelodic,” “asymmetric” were also used at this time. But while these borrowed terms were sometimes suitable as designations for specific phenomena, the word “atonal,” unfortunately I must say, served as a collective term for music that was assumed not only to lack relevance to a harmonic center, but also to have none of the other prerequisites of music, such as melody, rhythmic, formal divisibility into large and small. So the term “atonal” today really means as much as something that is not music, nonmusic, in fact something that is quite the opposite of what has always been understood as music.

Bistron: Aha, a term of reproach! And I see it as a valid one. So you’re saying, Mr. Berg, that there is no such contradiction and the lack of reference to a definite tonic does not actually shake the whole edifice of music?

Berg: Before I answer that question, Professor, let me put this forward: if this so-called atonal music cannot be related in harmonic terms to a major or minor scale—and after all there was music before the existence of this harmonic system— …

Bistron: … and what beautiful, artful, and imaginative music …

Berg: … it doesn’t follow that in the “atonal” artworks of the last quarter century, at least as regards the chromatic scale and the new chords derived from it, there cannot be found a harmonic center, although this, of course, is not identical to the concept of the old tonic. Even if this has not yet been brought into the form of a systematic theory.

Bistron: Oh, I find this reservation to be unjustified. The chromatic scale also follows a rule and comes from nature just as legitimately as the diatonic scale that was worked out earlier with simpler numbers—perhaps even more so. I believe I’m close to proving this.

Berg: All the better! But regardless of this, with “composition with twelve-tones related only one to another,” which Schoenberg first put into practice, we already have a system that in no way lags behind the older teaching of harmony in its regularity and cohesiveness of material.

Bistron: You mean the so-called twelve-tone rows? Would you like to speak about them further?

Berg: Not just now, Professor. Th at would lead us too far afield. Let’s just talk about the concept “atonal.”

Bistron: Certainly. But you still haven’t answered my earlier question: whether there is not in fact a contradiction between traditional music and the music of today and whether the renunciation of relation to a tonic does not in fact make the entire edifice of music totter.

Berg: I can answer your questions more easily by starting where we have found agreement—that the rejection of major and minor tonality in no way produces harmonic anarchy. Even if a few harmonic resources are lost along with major and minor, all of the other prerequisites of “serious” music are preserved.

Bistron: For example?

Berg: It is not enough just to tick them off without going into the matter further. Indeed, I must do so, because it is a question of showing that the concept of atonality, which related at f rst solely to harmony, has now become, as I said, a collective term for “nonmusic.”

Bistron: Nonmusic? I find this description too strong—I have never heard it before. I believe that the opponents of atonal sonorities want to stress the antithesis with so-called beautiful music.

Berg: As far as I’m concerned, that’s what it suggests. In any event, this collective term is intended to deny everything that makes up the content of music until now. I have already mentioned the words “arrhythmic,” “amelodic,” “asymmetric,” and I could cite a dozen more terms used to dismiss modern music, like cacophony or test-tube music, which have already partially faded from memory, or new ones like linearity, constructivism, New Objectivity, polytonality, machine music, etc. These may have relevance in certain specific cases, but they are all now brought together under a single umbrella in the phony notion of “atonal” music. The opponents of this music hold to it with great persistence so as to have a single term to dismiss all of new music by denying, as I said, the presence of what until now has made up music and thus to deny its justification for existing.

Bistron: You may be seeing things too darkly, Mr. Berg! Perhaps what you say may have been the case until not too long ago. But today people know that atonal music in and of itself can be engaging and in certain cases will be so. In cases that are truly artistic! It is only a matter of showing whether atonal music can really be called music in that same sense as with earlier works. That is, whether, as you say, only the harmonic basis of new music has been changed, with all other elements of traditional music still present.

Berg: And I do hold this and can prove it in every measure of a modern score. Prove it above all—to start with the most serious objection—by showing that this new music, as with traditional music, rests on motive, theme, main voice, and, in a word, melody, and that it progresses in just the same way as does all other good music.

Bistron: Well, is melody in the normal sense really possible in this atonal music?

Berg: Of course it is! Even, as is most often disputed, cantabile and songful melody.

Bistron: Now as concerns song, Mr. Berg, atonal music travels on new paths. Here there are certainly things not heard before, I would almost say things that seem at present to be outlandish.

Berg: But only in harmonic rudiments—there we are in agreement.

Bryan R. Simms is the editor of Pro Mundo – Pro Domo: The Writings of Alban Berg. He is Professor in the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California. He was formerly editor of the Journal of Music Theory and Music Theory Spectrum, and he has served on the Council of the American Musicological Society and Executive Board of the Society for Music Theory.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Alban Berg, by Emil Stumpp 1927. Deutsches Historisches Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What is atonal? A dialogue appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat does health reform do for Americans?The final judgement in the trial of Charles TaylorThe whale that inspired Greenpeace

Related StoriesWhat does health reform do for Americans?The final judgement in the trial of Charles TaylorThe whale that inspired Greenpeace

September 23, 2013

Fine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patient

Personalized medicine is one of the objectives of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 funding program and a high priority on the ESMO board’s strategic agenda: indeed, in oncology, many therapies share a narrow therapeutic index and high cost, implying that prescribing the wrong treatment to the wrong patient at the wrong time can have very negative consequences for both patients and public health systems.

While personalized medicine is the dream of every oncologist and the legitimate expectation of every cancer patient, it can only materialize in the next decade if extensive collaborative research efforts are launched and accompanied by a revolution in the sociology of medical research. The latter implies moving away from small-scale biomarker research projects with prolonged sequestration of data and entering an era of “team science” using high-throughput technologies and broad data sharing.

There is indeed a huge gap between our rapidly growing knowledge about the complex molecular-biological landscape of cancer and the extremely slow development of clinically useful and validated biomarkers. As a result, oncologists face serious challenges in daily clinical practice, including both the over- and undertreatment of patients and the prescription of ineffective therapies.

This remains true despite our living in the era of “targeted therapies”, given that the presence of the target does not equal efficacy of the corresponding targeted drug. A relevant example here is the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab, which is widely prescribed for women with HER2-positive breast cancer, both in the metastatic and the adjuvant setting. While this agent is considered to be the “star” of targeted drugs in view of its positive impact on breast cancer survival, oncologists know that roughly 50 percent of all patients with HER2-positive tumors do not actually benefit from the drug. The problem is that without validated biomarkers of drug resistance, we’re simply unable to identify those patients upfront.

Greater progress in treatment tailoring has been made in colorectal and lung cancer: the monoclonal antibody cetuximab, directed at the EGFR receptor, is known to be ineffective in the presence of RAF/RAS mutations and, therefore, its administration requires pre-testing of these “negative”-predictive biomarkers. Similarly, the targeted drugs gefitinib and erlotinib are prescribed in non-small cell lung cancer only when EGFR mutations have been identified. In such cases, these drugs can be administered with an almost 70-80 percent chance of antitumor activity.

The problems of potential overtreatment or undertreatment are particularly relevant to breast and colorectal cancers, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has been shown to improve survival “on average”. But there is no “average” patient in the clinic!

Each patient is unique, and therefore each treatment must be unique.

Our ability to identify the unique features of an individual patient’s cancer has been increasing dramatically. The last 15 years have witnessed the development and testing of multi-gene expression signatures in breast cancer, several of which have shown robust prognostic abilities. In other words, they identify a subgroup of women with hormone receptor-positive tumors who are very unlikely to experience a recurrence if treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy only. Two of these signatures − Mammaprint™ and OncotypeDX® – are undergoing prospective validation of their clinical utility in two large trials, MINDACT (EORTC10041/BIG3-04) and TailoRx, which are expected to report results in 2015-2016. Similar attempts to provide level-1 evidence for prognostic biomarkers in other solid tumors have not taken place, illustrating the huge commitment that is needed to change standard clinical practice.

The search for predictive multigene expression signatures − based on RNA expression – has been far less successful, and it is losing ground in favor of next generation DNA sequencing, or molecular screening. The dramatic decrease in the cost of the latter technology renders it accessible to researchers, treating physicians, and wealthy patients. The hope here is to use identify the actionable mutations within a tumor, in other words the “driver” mutations for which targeted drugs exist and that are expected to generate clinical benefit.

A word of caution is needed here: there is considerable danger of cancer micromanagement if this technology leaves the academic world for commercial laboratories too soon, since there is still little evidence for the majority of cancers that drug therapy directed by molecular screening actually improves patient survival.

Academic researchers need to be prepared to embrace complexity, since the likelihood that a single biomarker will explain a cancer’s behavior is extremely low: not only do tumors require in-depth characterization, but their microenvironment and the genetic background of the individual patient (host) need to be considered as well. This multidimensional approach can also benefit from modern molecular imaging techniques, implying the need for much closer collaboration with imaging experts.

Finally, a clear and straightforward regulatory path will need to be created for new diagnostic tests. There is currently very little incentive for companies to invest in molecular diagnostics in the European Union, and personalized oncology will remain an empty shell without a rigorous yet feasible methodology for obtaining regulatory approval of new “multiplex” molecular tests.

Martine J. Piccart, MD, PhD, is Professor of Oncology at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) and Director of Medicine at the Jules Bordet Institute, in Brussels, Belgium. Earning her medical degrees at the ULB and oncology qualifications in New York and London, she is also member of the Belgian Royal Academy of Medicine. Dr. Piccart is active in numerous professional organizations. Since January 2012, she has been President of the ESMO. She is immediate past-president of the EORTC, president-elect of ECCO and served on the ASCO Board. She is the author of the article ‘Personalised cancer management: closer, but not here yet’, which is published in Annals of Oncology.

Annals of Oncology is a multidisciplinary journal that publishes articles addressing medical oncology, surgery, radiotherapy, paediatric oncology, basic research, and the comprehensive management of patients with malignant diseases. It is published by OUP on behalf of the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Medical doctor comforting senior patient. By michaeljung, via iStockphoto.

The post Fine-tuning treatment to the individual cancer patient appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe demographic landscape, part II: The bad newsThe demographic landscape, part I: the good newsPolio provocation: a lingering public health debate

Related StoriesThe demographic landscape, part II: The bad newsThe demographic landscape, part I: the good newsPolio provocation: a lingering public health debate

What does health reform do for Americans?

Today, we’re kicking off a week long series on the Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act in anticipation of open enrollment beginning on 1 October 2013. Check back all this week for views and insights from Oxford University Press authors.

By Theda Skocpol and Lawrence R. Jacobs

The Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act that was passed by Congress and signed into law in March 2010 sets in motion reforms in US health insurance coming into full effect in 2014. Most Americans are confused about what the law promises — and no wonder. Opponents falsely decry the law as a “government takeover of health care.” Supporters are often tongue-tied, implying that the reforms are too complex to explain.But that is not true. The core parts of Affordable Care are easy to explain, and polls show they are popular with most Americans.

Health Reform Does Three Important Things

Sets new rules of the game for insurance companies

Most working Americans will still be covered by private health plans. But insurance companies will not be able to dump policyholders who become ill or refuse coverage to people with longterm health problems. Insurers must make profits by offering coverage to all applicants and improving the quality and affordability of care. They will be required to spend at least four of every five premium dollars on medical care — instead of padding bottom lines or inflating bonuses for executives.

Makes health coverage affordable for individuals and businesses

Health reform will make coverage affordable to more than nine of every ten US citizens and legal residents. Special credits will make private health plans affordable for middle-class families (earning up to $90,000 a year), and for businesses facing high insurance costs. Additional millions of Americans who work for modest wages will become eligible for expanded Medicaid coverage in their states.

Establishes health exchanges for comparison shopping

Health Exchanges are markets to let people and businesses shop for health plans whose benefits are described and compared in plain English. By going to a website, citizens and businesses will be able to see what health insurance plans are available and decide which kind of coverage, at what price, they might choose. Exchanges will also let people know if they are eligible for the new credits to help pay for coverage.

Every state — from Oregon and Vermont to Texas and South Carolina — has the right to take a strong role in implementing health reform. Its own elected officials, businesses, health providers, and citizen groups can decide how to set up their state’s health exchange and other programs to fit local conditions. Health reform does not impose “one size fits all” and the proof is evident around the country in red and blue states that are already putting health reform in place in various creative ways. Citizens groups can get involved in state-level decisions.

Questions and Controversies

Health reform remains politically contentious, and many citizens are still learning what the law promises to do. Here are some answers to frequently asked questions:

What reforms are already in place? Affordable Care already helps children, young adults, and senior citizens. Children with health problems cannot be denied coverage by insurance companies. Young adults can stay on their parents’ family plans until age 26 — and millions more already enjoy coverage they could not get before 2010. Medicare for senior citizens now includes free health checkups and additional help to cover prescription drugs. By 2014, all seniors will pay the same low prices for prescriptions. In addition, millions of Americans will receive rebate checks from insurance companies, because the reform requires premiums to be spent mainly on health care, not CEO salaries and bureaucracy. Companies have to refund premiums if they don’t spend eighty percent on actual health services.

What about the “individual mandate” — will the government force me to buy insurance I cannot afford? The brouhaha about the mandate is a lot of public fuss about very little. Starting in 2014, when good public or private health coverage is available to all Americans — and only after there are subsidies to help people pay — everyone will be asked to choose one of the plans available in his or her state. But the law says that people do not have to obtain coverage if they still cannot afford it, or if they have religious objections. Even when such exceptions do not apply, people can pay a small fine instead. The reason for asking individuals to contribute is obvious: when all Americans can afford insurance, we don’t want people to fail to sign up (or pay a fine) and thus force their neighbors to pay if they get very sick or end up in an accident. It’s just like car insurance: the system works only if everyone is included. America’s doctors and hospitals won’t leave someone to suffer or die, so we have to make sure everyone pays their share.

Can the United States afford health reform? The Affordable Care Act is already reducing the rate of increase in health costs. The law contains many provisions to encourage hospitals and doctors to experiment with cost-saving reforms. Right now, the United States wastes a lot of money on health care, without covering all our people. Affordable Care puts us on a better track, to provide coverage for everyone at prices families, businesses, and government can afford. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projects that the law will reduce the federal budget deficit modestly in the first decade and by a large amount in the second decade. Repealing or weakening Affordable Care would increase the federal budget deficit.

Will government bureaucrats decide what medical care is delivered? Absolutely not. Doctors along with patients and their families remain in full charge of medical decisions. And there are no “death panels” in health reform. That claim is a lie.

A version of this article originally appeared on Scholars Strategy Network.

Lawrence R. Jacobs and Theda Skocpol are the authors of Health Care Reform and American Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know, Revised and Updated Edition. Lawrence R. Jacobs is the Walter F. and Joan Mondale Chair for Political Studies and Director of the Center for the Study of Politics and Governance in the Hubert H. Humphrey Institute and Department of Political Science at the University of Minnesota. Theda Skocpol is the Victor S. Thomas Professor of Government and Sociology at Harvard University, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and past president of the American Political Science Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bandage soaked with blood in the shape of America. © Taylor Hinton via iStockphoto.

The post What does health reform do for Americans? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesGive peace a chance in SyriaCarnival Cruise and the contracting of everythingThe final judgement in the trial of Charles Taylor

Related StoriesGive peace a chance in SyriaCarnival Cruise and the contracting of everythingThe final judgement in the trial of Charles Taylor

The final judgement in the trial of Charles Taylor

The trial of former Liberian President Charles Taylor moved the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) into the limelight of international criminal justice for the last half decade. Without any doubt, the presence of a former Head of State in the dock drew international attention to the smallest of the ad hoc international criminal courts. The Appeals Chamber of the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) has now announced that it will render the appeal judgment in the case of Charles Taylor on 26 September 2013 at 11.00 a.m. CET. Taylor, who is in his sixties, was found guilty by the trial panel and sentenced to 50 years of imprisonment.

Given the importance of the Taylor case, the forthcoming issue of the Journal of International Criminal Justice contains a special symposium on the Taylor Trial Judgment and the future of the Residual Special Court. The symposium, edited by Laurel Baig and myself, features articles by Kai Ambos and Ousman Njikam on “Charles Taylor’s Criminal Responsibility,” Kevin Jon Heller on “The Taylor Sentencing Judgment,” Fidelma Donlon on the “Transition of Responsibilities from the Special Court to the Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone,” and Kirsten Keith on “Deconstructing Terrorism as a War Crime.”

The Taylor trial is the first completed criminal appeals process judging a former Head of State in modern international criminal law. There has been much debate about whether the SCSL was truly the first international criminal tribunal to have tried a head of state, pointing to the conviction of Karl Dönitz at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, who was the Head of State of the Nazi German Reich for about 20 days before Germany’s capitulation. But as the IMT did not have any appeal process, let’s simply give the credit to the SCSL of being the first ever to have accomplished such an historical task. The magnitude of this accomplishment is illustrated both by how long it has taken for the international community to fully try a former head of state and the practical challenges encountered by other courts, such as the incomplete Milosevic trial before the ICTY or the failure to arrest of Bashir for trial at the ICC. From a legal perspective, however, the SCSL should not be judged simply by such an historic achievement, but rather by the soundness of its legal and factual findings.

A daily news chalk board in Monrovia, Liberia. Photo by Lieutenant Colonel Terry VandenDolder, U.S. Africa Command. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Achievements of the SCSL

Looking back at the SCSL’s activities since mid-2002, when the first investigations started, it is obvious that bringing Charles Taylor to trial was not an easy task. The Court was plagued with challenges: financial constraints, challenging legal questions, the staggeringly slow pace of proceedings, lacking interest from the Sierra Leone population towards the end of the mandate, the precarious security situation in the first years of operations, the difficult relationship with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Then add further challenges unique to the Taylor proceedings such as the need to operate in three different countries and two different continents. These are only a few challenges amongst many more that endangered the success of this shoestring court. At the end of the day, SCSL has overcome these challenges to complete its mandate and contributed to Sierra Leone’s transition to peace and democracy. In retrospect, many of the problems encountered by the court now appear to be less acute in comparison to the other hybrid experiences in international criminal law.

Initially the sponsors of the court wished the court to deliver justice within three years. In the end it took more than a decade to accomplish the mandate. The Taylor trial alone lasted over six years. In its eleven years of existence, the SCSL issued 13 indictments against members of all warring factions resulting in eight convictions (not counting the Taylor conviction at the trial level, which if upheld would be the ninth). Only one accused, Johnny Paul Koroma, was never arrested and is believed to be deceased. Two accused (Foday Sankoh and Sam Bockarie) died shortly after charges were laid against them. Sam Hinga Norman died shortly before his judgment day in the Civil Defence Forces trial. Apart from those main “atrocity” trials, twelve contempt proceedings were initiated by the Prosecution resulting in ten convictions (one contempt case is still pending on appeal; one resulted in an acquittal, which so far is the one and only acquittal issued by the SCSL).

Following the Taylor Appeal Judgment, the SCSL will “transform” into the Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone (RSCSL) shortly after the completion of its mandate. According to the RSCSL statute this residual court will “continue the jurisdiction, functions, rights and obligations” of the SCSL. The developments leading to and the structure and work of this future organisation are explained in detail by Fidelma Donlon in the JICJ Symposium.

The Taylor Case and the Appeals Judgment

Taylor is accused of four charges of crimes against humanity (murder, rape, sexual slavery, other inhumane acts (i.e. mutilations), and enslavement), four charges of violations or Article 3 Common to the Geneva Conventions and of Additional Protocol II (acts of terrorism, murder, outrages upon personal dignity, cruel treatment, pillage) and for the conscription, enlistment or use of child soldiers. It is alleged that he committed those crimes on Sierra Leone soil from 30 November 1996 to 18 January 2002 remotely from Liberia.

Taylor was found guilty on all 11 counts by the trial judges on 26 April 2012. Even though Taylor’s conviction at trial may not have surprised the casual observer, he was actually convicted for far less than was initially charged by the prosecution. The prosecution was of the view that Taylor acted in concert with the leaders of the rebel movements in Sierra Leone (i.e. the RUF and AFRC) and that he and his co-conspirators shared the intend to commit all the crimes perpetrated in the Sierra Leone civil war. The judges rejected this claim, finding that the prosecution failed to proof the allegation that Taylor forged an agreement with the Sierra Leone rebels to commit crimes against the Sierra Leone population.

The Trial Chamber instead considered Taylor as an accessory and convicted him for aiding and abetting and planning crimes in a narrower time frame, i.e. from August 1997 to 18 January 2002. It found that Taylor aided and abetted by providing practical assistance, encouragement or moral support to the RUF in the commission of crimes during the course of their military operations in Sierra Leone. In that respect the Trial Chamber noted that “a common feature of all of the aforementioned forms of assistance is that they supported, sustained and enhanced the functioning of the RUF and its capacity to undertake military operations in the course of which crimes were committed” (Taylor Trial Judgment, para. 6936). It importantly and rather controversially held that the military operations of the RUF and RUF/AFRC were “inextricably linked to the commission of the crimes charged in the Indictment” (Taylor Trial Judgment, para. 6936). An individualized assessment of Taylor’s contribution to the specific crimes committed on Sierra Leone territory was therefore unnecessary. It was sufficient to simply proof that Taylor sustained the military operations of the rebels. As such military operations were, according to the Trial Chamber, “inextricably linked to the commission of the crimes” no proof to the substantial contribution to the individual crimes was any longer necessary. The Trial Chamber additionally found that Taylor devised a plan to attack major towns and the capital Freetown in late 1998 and early 1999 during which crimes were committed. Regarding his knowledge, the Trial Chamber found that Taylor was aware of the atrocities from at least the time when he assumed the presidency in Liberia in August 1997.

Many of the defence challenges on appeal questioned the evaluation of evidence by the trial judges. The facts of the case, and of the civil war more generally, were unsurprisingly complex. The trial judgment had to rely extensively on hearsay and circumstantial evidence. Some of the more troubling approaches to fact finding by the SCSL Chambers have been highlighted by Nancy Combs in her seminal book on “Fact Finding without Facts” and much of the same judicial attitudes towards inconsistencies and contradictions can be found in the Taylor Trial Judgment. It will be interesting to see how the Appeals Chamber addresses such challenges or whether it will simply rely on the principle that a “margin of deference” will be given to the fact finding of the Trial Chamber.

Apart from evidentiary questions one of the most controversial points on appeal will be the definition of aiding and abetting and whether this mode of attribution requires that the accused contributed with “specific direction” towards a crime. The Trial Chamber was of the opinion that the actus reus of aiding and abetting did not require such “specific direction”, relying on ICTY precedents in the Perišić Trial Judgment and Mrkšić Appeal Judgment. As other SCSL cases did in fact require such an element the rejection in the Taylor case is notable (RUF Trial Judgment, para. 277; CDF Trial Judgment, para. 229). In the Perišić Appeals Judgment, however, the ICTY Appeals Chamber controversially held that “specific direction” is a necessary element of aiding and abetting holding that:

“[I]n most cases, the provision of general assistance which could be used for both lawful and unlawful activities will not be sufficient, alone, to prove that this aid was specifically directed to crimes of principal perpetrators. In such circumstances, in order to enter a conviction for aiding and abetting, evidence establishing a direct link between the aid provided by an accused individual and the relevant crimes committed by principal perpetrators is necessary.”

More importantly, the SCSL Appeals Chamber’s own jurisprudence on this point is remarkable. In the CDF case it relieved an accused from criminal responsibility for aiding and abetting for providing military equipment, which was later used in the commission of crimes. At the time of his contribution CDF fighters were notorious for committing crimes against civilians. The Appeals Chamber stated that “the provision of logistics is not sufficient to establish beyond reasonable doubt that [the accused Fofana] contributed as an aider and abetter to the commission of specific criminal acts in Bo District” (see CDF Appeals Judgment, para. 102). The similarities with the Taylor case are striking and it will be interesting to see whether the Appeals Chamber will apply the same standards to Taylor. In a critical analysis of the Trial Chamber’s legal findings, Kai Ambos and Ousman Njikam highlight some considerable deficiencies in the Taylor Trial Judgment, placing the judgment’s assessment within the broader international criminal law jurisprudence on individual criminal responsibility by addressing the effect of the recent Perišić Appeal Judgment.

As mentioned above, the significance of the Taylor case is usually attributed to the fact that Taylor was indicted as the sitting Liberian head of state. The Appeals Chamber dismissed the legal questions surrounding any claims of immunity in 2004, before Taylor’s arrest and initial appearance in spring 2006 (when Taylor had already stepped down from his presidency). Any questions of immunity will therefore not feature in the forthcoming Appeal Judgment. His “special status” as a Head of State at a time when he allegedly contributed to the crimes in Sierra Leone was however considered as an aggravating circumstance in the sentencing judgment of the Trial Chamber. This “special status” and the extraterritoriality of Taylor’s acts trumped all mitigating circumstances. A detailed critique of the Sentencing Judgment by Kevin Jon Heller in the JICJ symposium points to some of the possible flaws of the 50 year sentence, in particular addressing the fact that Taylor was convicted as an accomplice and not as a principal. Comparing the sentence received by Taylor with other SCSL convicts, Heller concludes that the 50 years sentence may be disproportionate. The fact that the extraterritoriality of Taylor’s acts was considered as an aggravating circumstance is striking. Here the Chamber’s silence on the nature of the conflict in its verdict is notable. Other SCSL judgments found that despite the alleged assistance from Liberia, the nature was non-international in character. If this holding is correct, crimes committed in international armed conflicts would routinely deserve a higher penalty.

The historical pronouncement of the Appeals Chamber Judgment will be accessible over live stream.

Simon Meisenberg is a Legal Advisor, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (since 2011); former Senior Legal Officer (2009-2011) and Legal Officer (2005-2009) in the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Laurel Baig is the editor of the forthcoming symposium from Journal of International Criminal Justice entitled, Symposium: Last Judgment – The Taylor Trial Judgment and the Residual Future of the Special Court for Sierra Leone. This issue will be published online imminently, and all articles mentioned in the text of this blog post will be freely accessible for a limited time.

The views expressed here are those of the author alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, or the United Nations in general.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The final judgement in the trial of Charles Taylor appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCodes and copyrightsHow can a human being ‘disappear’?Carnival Cruise and the contracting of everything

Related StoriesCodes and copyrightsHow can a human being ‘disappear’?Carnival Cruise and the contracting of everything

Middle East food security after the Arab Spring

Syria and Egypt paradigmatically highlight the perils of food security in the Middle East. Oil exports of Egypt, the largest wheat importer of the world, ceased at the end of the 2000’s. Generating enough foreign exchange for food procurement became more difficult and plans for more self-sufficiency have failed in the face of limited water and land resources. The country needs economic diversification and alternative sources of income, but Asian producers are more competitive in mass markets like textiles. Political upheaval has not helped. Tourism has collapsed; Electrolux and a number of other multinationals have temporarily suspended operations. Transfers by oil-rich Gulf countries have become crucial for an economy on life support.

The situation in Syria is worse. Before its civil war it remained a small net-exporter of crude oil, but its overall petroleum balance has turned negative since 2008. Like Iran, it has a lack of refining capacity and needs to import petroleum products like diesel and heating oil. With the war and EU sanctions the situation has aggravated. Economic liberalization in the 2000’s dismantled agricultural support schemes and left farmers vulnerable to an epic drought that lasted from 2006-2011. Many migrated to the cities and put additional strain on the social fabric ahead of Syria’s uprising. Without aid deliveries of the World Food Program the country would face famine today. By October a quarter of all Syrians will rely on food aid, four million inside Syria and 2 million refugees in neighboring countries.

The food import dependence and lack of foreign exchange is all the more worrying as the global food crisis of 2008 has shown a diminished reliability of global food markets. Not only did prices skyrocket, some agricultural exporters like Argentina, Russia, and Vietnam announced export restrictions out of concern for their own food security. Naturally this sent shock waves through the Middle East, which imports a third of globally traded cereals.

The oil rich Gulf countries reacted by announcing investments in farmland abroad to secure privileged bilateral access to food production. Only a fraction of these investments has gotten off the ground, yet they have been controversial as they have been mostly announced in developing countries like Sudan or Pakistan that have severe food security issues themselves. Ill-conceived land investments will not offer equitable solutions to food security concerns of Middle Eastern nations, but rather economic diversification and trade agreements.

Eckart Woertz is senior researcher at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB) and author of Oil for Food. The Global Food Crisis and the Middle East, available via Oxford Scholarship Online. He can be followed on Twitter @eckartwoertz.

Oil for Food: The Global Food Crisis and the Middle East is available in print and through Oxford Scholarship Online. If you are a librarian, and would like to find out how to subscribe to Oxford Scholarship Online, please visit our Subscriber Services page. Alternatively, if you are an academic or student, why not recommend this valuable resource to your librarian?

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Syrian Flag. Image is available via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Middle East food security after the Arab Spring appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOil and threatened food securityGive peace a chance in SyriaMoralizing states: intervening in Syria

Related StoriesOil and threatened food securityGive peace a chance in SyriaMoralizing states: intervening in Syria

September 22, 2013

The whale that inspired Greenpeace

On 15 September 2013, Greenpeace celebrated its 42nd anniversary. The organization, which was born in Vancouver in 1971, began life as a one-off campaign against US nuclear testing in the far North Pacific. For many, however, it is probably best known for its dramatic anti-whaling protests, the first of which took place in 1975 off the coast of California. What is perhaps less well-known, however, is that if it were not for one particular cetacean—a killer whale named Skana—Greenpeace may never have embarked on the campaign that helped virtually eliminate commercial whaling and made Greenpeace household name.

A killer whale (Orcinus orca) in Vancouver Aquarium, 1998. Photograph by Jerzy Strzelecki. CC 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Skana was born and raised in the sheltered waters of Puget Sound. She was six years old when her entire pod was captured in Yukon Harbor, Washington, on 15 February 1967. She was sold to the Vancouver Aquarium, where she soon met a young New Zealand scientist named Paul Spong. Spong had recently completed his PhD in neuroscience from the prestigious Brain Research Institute at UCLA and was working as a research scientist at the University of British Columbia.

Spong had never worked with cetaceans and initially treated Skana much like a giant lab rat. His goal was to determine how much whales relied on their vision as opposed to their sonar. Over the next year, he conducted a series of experiments designed to test Skana’s visual acuity. He would place two cards in the water—one with a single line and one with two lines—and reward Skana whenever she chose the double-lined card. Gradually, Spong reduced the distance between the two lines until Skana could no longer distinguish between the two cards. At one-sixteenth of an inch, Skana’s rate of accuracy was 90 percent; at less then one-sixteenth, however, her success rate plummeted.

Before publishing his results, Spong decided to repeat the experiment one last time at one-sixteenth of an inch. Much to his surprise, Skana not only failed the test but also managed to choose the wrong card eighty-three times in a row. It was clear to Spong that such a result could not occur by mere chance: that would be the equivalent of getting eighty-three tails from eight-three coin tosses. Skana, for whatever reason, was deliberately choosing the wrong card.

At first, Spong became despondent with Skana’s conduct. His visual acuity data had been ruined, and Skana’s uncooperative behavior meant that she could not be trusted to perform further tests. Throughout the months he had been working with her, Spong had grown to enjoy Skana’s company, but he was still fearful of her size and power and continued to maintain an objective distance between himself and his subject. Now, he decided, it was time to abandon the formal experiments and simply spend time with Skana, observing her, interacting with her, and getting to know her better.

One day as Spong was sitting at the edge of the pool with his feet dangling in the water, Skana approached him slowly, as she often did, before suddenly slashing her open mouth across his bare feet. Her four-inch teeth, which could easily have severed his feet like twigs from a branch, merely grazed his skin with a gentle caress. He immediately pulled his feet out, gasping in astonishment. In short time, however, his curiosity overcame his fear, and he gingerly lowered his legs back into the water. Skana again raked her teeth across the tops and soles of his feet, and once more Spong instinctively jerked them out of the water. He repeated the procedure eleven times with the same result. Then, on the twelfth, he became determined to restrain his urge to flinch. This time, Skana delicately clasped his motionless feet in her mouth, let them go, and swam away making what sounded like contented vocalizations. Spong left his feet in the water, but Skana did not approach them again. Bewildered and excited, Spong felt like he had just undergone a role reversal: Skana was now the experimenter, and he was her subject.

At that point, according to Spong, he and Skana entered a “joyous period of mutual exploration”: “I dropped my posture of remoteness, opened my mind, and personally engaged myself in Skana’s learning. . . . This whale was no big brained rat or mouse. She was more like a person: inquisitive, inventive, joyous, gentle, joking, patient, and, above all, unafraid and exquisitely self-controlled.” Spong was soon convinced that cetaceans were in their own way as intelligent and emotionally sophisticated as humans and that hunting them was therefore akin to murder. Something had to be done to end the barbaric practice of whaling, but what?

If there was one organization that was both radical and skilled enough to challenge the whalers on the high seas, it was Greenpeace. By 1974, they had organized several lengthy Pacific Ocean voyages as part of their protests against US and French nuclear testing. Happily for Spong, Greenpeace was based in Vancouver, and one of its leading activists, Bob Hunter, was a well-known hippie journalist writing for the city’s major newspaper, the Vancouver Sun. Spong, himself a devotee of the sixties counterculture, organized a meeting with Hunter, and the two hit it off immediately. Hunter had read some of the literature on whale intelligence and shared Spong’s outrage about whaling. However, he was skeptical about the possibility of convincing others within Greenpeace to redirect the organization’s attention from nuclear weapons to whales.

In an effort to persuade Hunter to do his utmost to convince Greenpeace, Spong invited him to visit Skana. Within minutes of meeting her, Hunter was stroking her jaw and rubbing his head against hers. Then, as he was leaning out over the pool, Skana suddenly emerged from the water and took his head inside her mouth, holding it there for several seconds. “It was not possible for me to move a fraction of an inch,” Hunter recalled.

“I was like a crystal goblet in a vice. I experienced a flash of utter aloneness, knowing that if she chose to chomp, there was nothing anyone on earth could do to save me. I was completely at her mercy. Fear exploded in my chest, yet the feeling of trustful happiness continued in my head. As though satisfied, she let go and sank away—ever so gently—with a handful of my hair snagged around two huge teeth.”

For a hippie journalist steeped in the I Ching and Gestalt psychology, it was a life-changing experience. Hunter believed that Skana had intentionally revealed the path he should now follow. She had exposed his fear and illuminated the secret corners of his soul. He was now certain that whales represented a supreme form of power and intelligence rooted in oneness with nature, a state that humans, in their pathetic struggles to conquer the natural world, could never achieve.

Hunter was now ready to mount an anti-whaling crusade. Initially, he was unable to persuade Greenpeace to embrace the cause. Nevertheless, he and Spong were both obsessed with the idea. They developed a strategy they thought might stop the whalers while also delivering images of the horrors of whaling into living rooms around the world. They would harass whaling ships in small inflatable motor boats and film the encounter. Within a few months, Spong and Hunter’s enthusiasm had become infectious, and the other members of Greenpeace agreed to mount a protest in 1975. And they have been doing it ever since.

Greenpeace Ship Gondwana, 1990. Photograph by Monster4711. CC 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Whatever one might think of Greenpeace’s “Buddha of the deep” view of whales, there is no doubt that many whale species were—and some remain—close to extinction. Despite the success of the 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling, Japan continues to hunt whales under the guise of “scientific research.” Norway and Iceland don’t even bother to pretend that their whaling is anything other than commercial. The US Navy, meanwhile, has just released a report stating that it expects to kill hundreds of whales and dolphins as part of its bombing and mid-frequency sonar tests.

Skana died in captivity in 1980. It seems unlikely that she had any idea of the impact that her relationship with Spong and Hunter had on Greenpeace and the world’s whalers. Nevertheless, anyone concerned about the fate of the world’s whales can’t help but wish that a few Japanese whalers and American admirals could have a close encounter with someone like Skana.

Frank Zelko is Associate Professor of Environmental Studies and History at the University of Vermont. He is the author of Make it a Green Peace!: The Rise of Countercultural Environmentalism, which has just been published by OUP.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The whale that inspired Greenpeace appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKing Richard’s wormsThe first tanks and the Battle of SommeEdmund Gosse: nonconformist?

Related StoriesKing Richard’s wormsThe first tanks and the Battle of SommeEdmund Gosse: nonconformist?

September 21, 2013

Edmund Gosse: nonconformist?

By Michael Newton

“The trouble with you,” an old friend recently declared to me, “is that you have always been a conformist.” He meant that I had never undertaken that necessary radical break with my parents and their ideals and interests. Without such a generational rupture, it seemed to him, nobody could claim to be a fully independent, realised person. While he had been dropping acid and dropping (temporarily) out of college, I’d been reclining under a tree with John Keats. And surely there was nothing rebellious in that.

Edmund Gosse, that great forerunner of adolescent mutiny, might have disagreed with him. For it was in part by falling in love with the poetry of Keats and others that Gosse initiated the process that precipitated the crisis.

Portrait of Edmund Gosse by John Singer Sargent

Though there are famous precedents — most notably Shakespeare’s shrewdly riotous Prince Hal — it may be possible to trace our culture’s current certainty that the attainment of adulthood requires an act of rebellion to two late-Victorian nay-sayers: Samuel Butler and Edmund Gosse. Both published their record of filial disobedience just as the Victorian era expired, Butler’s The Way of All Flesh in 1903 and Gosse’s superb Father and Son in 1907. \ Both texts were to provide an extra dynamism to the early twentieth-century’s denunciation of its fathers’ and grandfathers’ world.Brought up among the Plymouth Brethren, destined for a life of service and spiritual rigour, young Edmund Gosse found himself, by temperament, by nature, in opposition to the tenets and atmosphere of his parent’s milieu. Three things likely served to bring young Gosse to his act of refusal. First, there was simply his love of literature: when the teenage Gosse hears Shakespeare denounced as a soul burning in hell, his instincts make him ardently side with the despised and marvellous writer. For Gosse, reading prompted the revolution. Gosse junior became a lover of many books; his biologist father, Philip Henry Gosse, saw the need for only one — the Bible, the book itself. More than this, Edmund believed that the interpretation of texts, as of people and the events of life, must necessarily be tentative, multiple, inconclusive; meanwhile Philip believed in the eternal inerrancy and permanence of the word.

Then there was the fact that for a young man in the 1870s devoted to poetry and the art of his time an adherence to Greece and a form of happy, hedonistic, paganism was inescapable. To love Keats and Shelley and Swinburne was to array yourself among the pantheon of the gods against the one God. The Hellenic charm of myth, of naiads and the gracious physique was greater than the offence of the tortured, abject body of the crucified Christ.

Finally, though it receives no direct mention in Father and Son itself, there was the force of Gosse’s rather mysterious sexuality. Though he married and became a contented father, Gosse certainly desired men, or rather one particular man – the sculptor Hamo Thorneycroft. (Siegfried Sassoon quipped that Gosse wasn’t homosexual, he was ‘Hamosexual’.) Such a love could find no place among his father’s dour precepts.

Perhaps it is the alleged conformist in me, yet in reading Father and Son it proves hard not to find one’s sympathies divided between Gosse the father and Gosse the son. Young Gosse engages us, of course, and he is the pure, articulate lens through which we view the world of the book. And yet, it is the apparently dour, but actually loveably earnest, passionate, baffled and yet resilient father who somehow garners our love. When Gosse makes the final break and makes his declaration of independence, we both sense the release of liberty as we sorrow with the perplexed man who loses his son.

Father and Son remains a key book in our understanding of ourselves. We live in a world where for many the battle lines of generational conflict have blurred. Yet nonetheless the book’s gentle, humorous analysis of the tensions between parents and children continues to be indispensable. Indeed in the era of Dennett and Dawkins, Gosse’s vivid account of the crisis provoked in at least some of the faithful by Darwin’s theory makes the book even more timely than it looked when this edition was first prepared. And in a world where fundamentalist forms of religion are rather on the rise than on the wane, it seems likely that Father and Son will remain required reading for some years to come, as many more follow him in choosing, against the will of their parents, a path of their own.

Michael Newton teaches at the University of Leiden. He has edited Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son for Oxford World’s Classics, and Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent and The Penguin Book of Ghost Stories for Penguin. He is the author of Savage Girls and Wild Boys: A History of Feral Children and Age of Assassins: A History of Conspiracy and Political Violence, 1865-1981 (both for Faber & Faber) and of a book for the BFI Film Classics series on Kind Hearts and Coronets. He is currently preparing an edition of Victorian and Edwardian fairy-stories for Oxford World’s Classics.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Portrait of Edmund Gosse by John Singer Sargent [Public Domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Edmund Gosse: nonconformist? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe poetry of Federico García Lorca10 questions for Wayne KoestenbaumA folklore and fairy tales reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Related StoriesThe poetry of Federico García Lorca10 questions for Wayne KoestenbaumA folklore and fairy tales reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Healing the divide between Christianity and the occult

Mormon critics have long tried to discredit Joseph Smith by identifying him with a host of contested religious movements from the ancient world. These include Gnosticism, hermeticism, alchemy, and the Jewish Kabbalah. What these movements share is a more robust connection between the material and supernatural worlds as well as a more optimistic understanding of humanity’s striving for God than traditional Christianity permits. By associating Smith with what came to be known as the occult, critics could portray his treasure seeking, aided by seer stones, as evidence of his untrustworthiness. Joseph’s magical worldview, they could argue, culminated with the fantastical story of the golden plates.

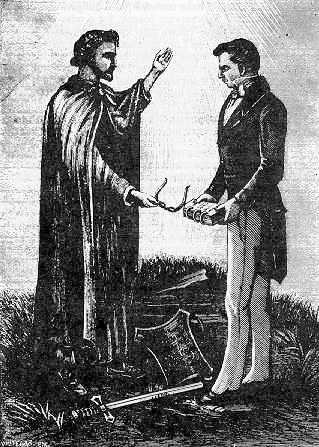

The Angel Moroni delivering the Golden Plates to Joseph Smith in 1827. From Reminiscences of Joseph the Prophet, by Edward Stevenson, Salt Lake City 1893. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Defenders admit to Joseph’s youthful indiscretions but point out that once he translated the plates into the Book of Mormon, he never dabbled in magic again. Devout Mormons also argue that if God really did give someone the task of finding the golden plates, what better person than a humble and pious young man with experience in digging for buried treasure? There is also, significantly, little evidence that Joseph was knowledgeable about the hermetic literature. Nonetheless, skeptics, undeterred, continue to search for the missing link that would demonstrate once and for all that Joseph was a fraud.I am with Joseph’s defenders in this argument, mainly because I think Joseph’s world had not yet differentiated between magic and religion as separate and opposed social spheres, but also because I think the Bible does not display a clear demarcation between the two. There is little need to trace any of Joseph’s activities, pre- or post- the golden plates, to any other source than the Bible, which treats seer stones, for example, in a matter-of-fact manner (Numbers 27:21 and 1 Samuel 28:6).

The debates about Joseph and his social context will continue, of course, but I am interested in taking a big step back in order to look at the broader picture. Reactions to Mormonism’s relationship to a magical worldview can serve as a template to the more general relationship of Christianity to the so-called occult. The occult is a loaded word, weighed down with sinister associations of black magic and demonology. Esotericism is a better term, but the occult has a stronger hold in general usage. It literally means hidden or secret religious knowledge and has the connotation of a methodical and even scientific approach to the spiritual realm. If Christianity is defined as faith in revealed truth, then the occult is the exact opposite: rational inquiry into paranormal experiences (experiences that lie beyond the quantifiable measurements of science but are, nonetheless, empirically grounded). But what if Christianity is not defined as blind faith, and what if the occult is not simply a pseudo-scientific examination of the supernatural?

Many people today are spiritual seekers, and that goes for more than the “spiritual but not religious” crowd. Even regular church-goers are unlikely to draw the same theological lines between Christianity and its competitors as generations in the past. The various branches of Christianity are learning to appreciate each other’s traditions, and for decades many Christians have been struggling to learn from Eastern religions. Arguably, there is a rift within Christianity that goes back much further than these ecclesial and global divisions. The antagonism I am talking about is the one between Christianity and the occult. Since the occult can be said to have pagan roots, and Christianity made its first missions, after the Jewish community, to pagan society, rethinking the relationship between Christianity and the occult can open up new avenues to getting at the very essence of the Christian faith.

The occult is more than just paganism, of course. It is as much an heir to Christianity as it is to ancient Greek and Roman rites and beliefs. Although the classical theism of Catholicism’s best theologians placed all things divine in an immaterial realm completely apart from the physical world, Catholic spiritual practices remained dependent on the conviction that material objects can be imbued with divine power. In fact, the division between Protestantism and Roman Catholicism, which has done so much to trouble the heart of Christendom, can be seen as a byproduct of unresolved issues in the relationship of Christianity to the occult. The Protestant reformers rejected transubstantiation, the central rite of Roman Catholicism, because they thought it was little more than a species of magic intent on transferring divine properties to mere matter. It is one of the great ironies of history that the birth of Protestantism coincided with the rebirth of the occult in the Renaissance. Alchemists tried to transform base metals into silver and gold. If transubstantiation is your starting point, then it is not hard to imagine that the lowest forms of matter can be raised to the highest. When Protestants sharply separated divine grace from anything pertaining to material change, they laid the foundation for modern science and thus the eclipse of the occult.

Many of the modern philosophers associated with the occult, most prominently Emanuel Swedenborg and Rudolf Steiner, were explicit about their dedication to Jesus Christ, even if their interpretations of his cosmic significance were speculative and from an orthodox vantage point heretical. Their work is marked by a longing for a more physical depiction of the divine and a more concrete, less abstract approach to the supernatural. Today, in even the most orthodox theological circles, one hears incessant calls for a new approach to the body, the cosmos, and the natural sciences. Christians are eager to rediscover spiritual practices that appeal to the eye and ear as well as the mind. Many young people follow the cross but also find healing in Tibetan singing bowls. It is time then for a renewed Christian encounter with the occult.

What would an occult-friendly form of Christianity look like? Mormonism is not rooted in or dependent on the occult in a direct way, but it does imbue Christianity with the spirit of the occult. A first step toward healing the divide between Christianity and the occult, then, should be a careful evaluation of what Mormon theology can contribute to conventional Christian attitudes toward the relationship of spirit to matter and the human potential to transform the physical world into the kingdom of God. Joseph’s golden plates look like alchemy to his critics, but they can also help all Christians to begin discovering their faith’s own ancient roots.

Stephen H. Webb has taught philosophy and religion for twenty-five years. He is the author of eleven books on such varied topics as the musical philosophy of Bob Dylan, theological critiques of the theory of evolution, the importance of the doctrine of providence in American history, the role of religion in public education, and the history of vegetarianism. He has been published in First Things, Books & Culture, and Touchstone. He is the author of Mormon Christianity: What Other Christians Can Learn From the Latter-day Saints.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Healing the divide between Christianity and the occult appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Holy CrossOf Mormonish and SaintspeakCarnival Cruise and the contracting of everything

Related StoriesThe Holy CrossOf Mormonish and SaintspeakCarnival Cruise and the contracting of everything

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers