Oxford University Press's Blog, page 904

September 11, 2013

Ezra Pound and James Strachey Barnes

The extent of Ezra Pound‘s involvement with Italian fascism during the Second World War has been one of the most troubling and contentious issues in modernist literary studies. After broadcasting on the wartime propaganda services of the Italian Fascist state and its successor, the Republic of Salò, Pound was indicted for treason by the United States government and arrested at the end of the war, eventually being found unfit to stand trial and instead committed to a psychiatric hospital. These episodes have obviously led to a number of major questions for scholars. Was Pound really insane? Were his actions really treasonous? Or did these broadcasts reveal the extent of Pound’s true sympathies for fascism and anti-Semitism?

Ezra Pound

Our research has tried to shed new light on these questions by exploring Pound’s relationship with James Strachey Barnes (1890-1955), an Italophile Englishman who also broadcast propaganda for Mussolini during the Second World War. Barnes is a figure who occasionally pops up in the footnotes of modernism – he was a cousin to Lytton Strachey, acquainted with Virginia Woolf and T. S. Eliot, and the inspiration for one of the characters in D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love . Barnes was also one of the major intellectual supporters of Italian fascism, writing a number of books in support of the fascist cause, running a pro-fascist think-tank, and meeting Mussolini on several occasions. This culminated in his propaganda work in Italy during the Second World War, where he compiled hundreds of broadcasts with titles such as “Thank God for the Blunders of our Enemies,” with the overall aim (as he stated) of “inciting the English people to revolt against their Government.”Pound and Barnes are known to have been friends and work-associates during the war, but despite the obvious significance of this relationship Barnes has only been a peripheral figure in Pound scholarship, and indeed little-remembered at all in the history of the inter-war radical right. One of the major problems is that the war (particularly the latter stages) remains one of the least-documented periods in Pound’s life, and almost all of Barnes’s personal papers were destroyed by his family after his death. But importantly, our research for the article found that enough documents still exist to allow us to begin to reconstruct the relationship between Barnes and Pound. The most significant of these was Barnes’s unpublished diary covering the period of 1943-5 (which eventually surfaced in the possession of his daughter-in-law, who was then living in Lund, Sweden), but we also drew upon a sequence of letters between Pound and Barnes held in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale, as well as various government files held at the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

From these documents a picture emerges not just of Barnes’s extensive collaborations with the Italian propaganda apparatus, but also of how this was often conducted with Pound’s close advice and support. And vice-versa. We now know that Pound followed Barnes’s broadcasts and offered detailed advice about their tone and content, and that Pound would often stay with Barnes in Rome and engage in long discussions on economics. When the Allies invaded the Italian mainland in September 1943 Barnes and Pound made plans to flee Rome together, with Barnes even managing to get a fake Italian passport issued for Pound to aid his escape (Pound had fled north before Barnes could get it to him). It was Barnes who lured Pound back to broadcast for the newly-formed Salò Republic, where Barnes and Pound would collaborate on programs said to contain “Pound’s most virulent anti-Semitism.” Barnes’s diary even recorded a letter from Pound to Mussolini, in which Pound promised to “fight” the “infamous propaganda” of the Allies, but warned the Duce that “I don’t need a ministry, but without a microphone I can’t send.”

So what does this mean for our understanding of Pound? Perhaps most crucially, it gives us important new material to reassess the extent to which he was a willing part of the official Fascist propaganda apparatus. Interestingly, after Barnes’s death, Pound attempted to distance himself from his previous association with Barnes, drafting a letter for The Times which stressed “the difference of angle” between the two, emphatically stating that “Pound never WAS fascist…Not only was he not fascist, he was ANTI-socialist and against the socialist elements in the fascist program.” But as much as Pound tried to wash his hands, Barnes’s papers provide a rather different picture, suggesting that, throughout the war, Pound had served as the revered and trusted mentor for a man who dubbed himself “the Italian Lord Haw-Haw.”

David Bradshaw is Professor of English Literature at Oxford University and a Fellow of Worcester College. James Smith is a Lecturer in English at Durham University. They are the authors of the paper ‘Ezra Pound, James Strachey Barnes (‘The Italian Lord Haw-Haw’) and Italian Fascism‘, published in the Review of English Studies.

The Review of English Studies was founded in 1925 to publish literary-historical research in all areas of English literature and the English language from the earliest period to the present. From the outset, RES has welcomed scholarship and criticism arising from newly discovered sources or advancing fresh interpretation of known material. Successive editors have built on this tradition while responding to innovations in the discipline and reinforcing the journal’s role as a forum for the best new research.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Ezra Pound US passport photo (undated) [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ezra Pound and James Strachey Barnes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe fall of MussoliniBurlesque in New York: The writing of Gypsy Rose LeePolio provocation: a lingering public health debate

Related StoriesThe fall of MussoliniBurlesque in New York: The writing of Gypsy Rose LeePolio provocation: a lingering public health debate

September 10, 2013

Prospects for China’s migrant workers

Let’s assume that Nobel economist Paul Krugman and others are right about China’s economy being “in big trouble” and headed for a “nasty slump.” What does this mean for the 150 million current Chinese workers who left their home villages to fill jobs in the new economy’s growth centers? When a rapidly emerging economy built on these internal migrants — aka surplus rural labor — begins to cool, what becomes of the peasants-turned-factory-workers who made the economic miracle possible?

The answer depends largely on public policy choices (past and present). China’s leaders have long understood the destabilizing effects of large-scale labor migration, which is why they institutionalized the modern hukou system of household registration in the 1950s. In post-market reform China, a hukou operates less like an internal passport than it once did, with fewer restrictions on mobility, but all Chinese still must register in the location of their birth, and access to many services is still tied to that location. Although government officials have discussed the issue and adopted minor reforms around the edges of the hukou system for some time, receipt of pensions, health care, unemployment insurance, and other basic social benefits still tends to be highly skewed in the new economy toward areas of rapid economic development and their registrants. Migrant workers and their families are typically stuck at the end of the social protection queue.

Take schooling, for example. Public education is a national entitlement for all Chinese children under age 14, but locally financed. Until recently, children of migrants were included in the budgets of their rural home districts, where they were registered but did not use services; at the same time, they were excluded from the budgets of their actual areas of residence, where they needed services but could not register. Some migrant-receiving urban districts addressed the mismatch by charging fees for migrant children to attend their schools. This practice caused severe material hardship for many migrant families and led others to use substandard schools that catered to migrant children. The Chinese government introduced new policies in 2003 that tied responsibility for education delivery to the receiving jurisdiction rather than the district of origin and forbade the imposition of differential school fees based on household registration status. The policies did not address the financing constraints of the receiving local governments, however, and did not offer fiscal relief for local and municipal jurisdictions faced with large numbers of migrant students. As a result, differences in local-provincial financing arrangements have led to substantial district-by-district differences in educational access and quality for children of migrants.

Alongside widely recognized problems like education financing, novel problems associated with labor migration are sure to emerge if and when the much-anticipated economic downturn occurs. Redundancies will probably hit migrants first. Some laid-off migrants will return to their rural home districts, where social insurance systems tend to be thin. Other laid-off migrants will stay in the cities, placing additional pressure on urban social programs. From the migrants’ perspective, it is not immediately clear which option—stay in the city or return to the countryside—is best. In keeping with the location of economic growth, greater priority has been given to developing social programs in urban areas to replace the old, pre-reform arrangements, which depended heavily on guarantees of lifetime employment and direct provision of social services by state-owned enterprises. But migrant workers have tended to fall through the cracks of these new, post-reform urban social programs. Meanwhile, rural services have only slowly improved, lagging far behind those offered by urban social programs.

From the perspective of the general welfare, public policy needs to strike a delicate balance of incentives for return migration vs. encouraging migrants to stay in cities, while also stimulating domestic consumption nationwide. Return migration, for example, ought to serve the dual goals of taking pressure off urban social systems and transferring skills, knowledge, and human resources to the countryside. Policy might steer return migration toward rural areas that demonstrate better prospects for future job growth. Return migrants also might be encouraged and/or assisted to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities back home. At the same time, urban enterprises will need to recall some of their laid-off workers when economic growth resumes, and that points to the value of providing reasonably generous unemployment benefits for migrants in cities alongside opportunities for up-skilling during periods of slower growth. Expanded public and private spending on pensions, unemployment benefits, health care, child care, and other benefits and services are likely to be used to stimulate domestic consumption and provide a counterweight to what many have referred to as China’s lop-sided, investment-heavy growth model. Making these benefits available everywhere and regardless of hukou could be seen as advancing both economic development and social protection goals.

China, of course, is not the first country to experience enormous economic growth driven by rural to urban migration. In many countries, the result was massive urban poverty and hardship; think of Dickensian London and America’s dangerous 19th and early 20th century slums. So far, China seems to have avoided the worst elements of these costly transitions. But the hukou system has caused hardships of its own—particularly for China’s migrant worker population—in the country’s post-market reform era. With many prominent economists predicting far slower economic growth rates in the future, policymakers must promptly address the issues facing migrant workers and their families. Will China’s leaders be able to cross this river before it floods, or will they be caught in the middle, feeling for the next stone?

Douglas J. Besharov, JD, is the Norman and Florence Brody Professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Policy and a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council of the United States. Karen Baehler is Scholar in Residence at the School of Public Affairs at American University. They co-edited Chinese Social Policy in a Time of Transition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: New constructed buildings at Shenzen China. © tekinturkdogan via iStockphoto.

The post Prospects for China’s migrant workers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe case against striking SyriaNational Grandparents Day TributeCops and Robbers Redux

Related StoriesThe case against striking SyriaNational Grandparents Day TributeCops and Robbers Redux

Israel’s survival in the midst of growing chaos

Nowadays, chaotic disintegration seems widely evident in world politics, especially in the visibly-fragmenting Middle East. What does it mean to live with a constant and unavoidable awareness of such fracturing? This vital question should be asked everywhere on earth, but most urgently in Israel.

For the Jewish State, an expanding shroud of anarchy may portend a special sort of vulnerability. Inevitably, Israel, the individual Jew in macrocosm, could become the world’s principal victim of any further deterioration and disorder. Given the natural interrelatedness of world politics, even the precipitating events of war, terror, and genocide could occur elsewhere.

Ultimately, bombs may fly conspicuously over Syria and Iran, but the most severe consequences could be experienced not in Damascus or Tehran, but in Tel-Aviv and Jerusalem.

Chaos, however, can be instructive. In a strange and paradoxical symmetry, even sorely palpable disintegrations can reveal determinable sense and form. Spawned by carefully rehearsed explosions of large-scale conflict and related crimes against humanity, the diminution of any residual world authority processes could display a discernible shape. How exactly should this eccentric geometry of chaos be correctly deciphered by Israel, and also by its generally reluctant allies in Washington?

Always the world, like the many individual countries that comprise it, is best understood as a system. It follows that what happens in any one part of this world, must affect, differentially, of course, what happens in all or several of the other parts. When a particular deterioration is marked, the corollary effects can undermine regional and global stability. When a deterioration is sudden and catastrophic, the perilously unraveling effects could be immediate and overwhelming.

Recognizing that any rapid and far-reaching collapse of order could occasion a substantial or even complete return to “everyone for himself” dynamics in world politics — what the seventeenth-century English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes, had called a “war of all against all” — Israel’s leaders must consider how they would best respond to imperiled national life in a crumbling “state of nature.”

As we are well aware, especially from urgent current news coming out of the Middle East, any such consideration is prima facie reasonable. It is all the more critical, to the extent that a decisive triggering mechanism of collapse could originate from certain direct attacks upon Israel. These potent aggressions could be chemical, biological, or ultimately nuclear. Moreover, pertinent prohibitions of international law would likely be of little protective benefit.

The flea market in the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel. Photo by Ester Inbar, available from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Use..., via Wikimedia Commons.

Any chaotic disintegration of the larger international system, whether slow and incremental, or sudden and catastrophic, will impact the Israeli system. In the most obvious manifestation of this predictable impact, Israel will have to orient its core strategic planning to a nuanced variety of worst-case scenarios. Analytic focus would be more on the entire range of conceivable self-help security options than on any more traditionally-favored kinds of alliance guarantees.

Diplomatic processes premised on assumptions of reason and rationality will soon have to be reconsidered, and reimagined. Israel’s judgments about any “Peace Process” or “Road Map” expectations will not become less important, but they will need to be made in evident consequence of anticipated world-system changes. From the standpoint of Israel’s overall security, any such reorientation of planning, from anticipations of largely separate and unrelated threats, to presumptions of interrelated or “synergistic” dangers, would provide a badly-needed framework for strategic decision. Should Israel’s leaders react to a presumptively unstoppable anarchy in world affairs, by hardening their commitment to national self-reliance, including certain preemptive military force, Israel’s enemies could surely respond, individually or collectively, in similarly “self-reliant” ways.

There are crucial and tangibly complex feedback implications of this “creation in reverse.” By likening both the world as a whole, and their beleaguered state in particular, to the concept of system, Israel’s leadership could finally learn, before it is too late, that states can die for different reasons. Following a long-neglected but still-promising Spenglerian paradigm of civilizational decline, these states can fall apart and disappear not only because of any direct, mortal blow, but also in combined consequence of distinctly less than mortal blows. Minor insults and impediments can incrementally prove fatal, either by affecting the organism’s overall will to live, or by making it possible for a more corrosively major insult to take effect.

Taken individually, Israel’s past and future surrenders of land, its understandable reluctance to accept certain life-saving preemption options, and its still-misdirected negotiation of peace agreements, may not bring about the end. Taken together, however, these insults occurring within a substantially wider pattern of chaos and anarchy could have a weakening effect on the Israeli organism. Whether the principal effect would be one that impairs the Jewish State’s will to endure, or one that could actually open Israel up to a devastating missile attack, or to a calamitous act of terror, remains plainly unclear.

Israel must ask itself the following authentically basic question. What is the true form and meaning of chaos in world politics, and how should this shifting geometry of disintegration affect our national survival strategy? The answers, assuredly, will come from imaginative efforts at a self-consciously deeper understanding of small state power obligations, especially in a worsening condition of Nature.

In the final analysis, such existential obligations will be reducible to various improved methods of national self-reliance, including assorted preparations for deterrence, preemption, and absolutely every identifiable form of war-fighting. For Israel, among other things, this will mean steady enhancements of ballistic missile defense, and also recognizable movements away from the country’s increasingly antiquated posture of deliberate nuclear ambiguity.

For Israel, in particular, further chaotic disintegration in world politics could soon offer a profoundly serious challenge. If this challenge is correctly accepted in Jerusalem, as an intellectual rather than political effort, the beleaguered country’s necessary strategies of national survival will stand a better chance of achieving success.

Louis René Beres (Ph.D., Princeton, 1971) is the author of many books and articles dealing with international relations and international law. He was born in Zürich, Switzerland, at the end of World War II. Read his previous articles for the OUPblog.

If you are interested in the subject of world politics, you may be interested in Rethinking World Politics: A Theory of Transnational Neopluralism by Philip G. Cerny. Cerny explains that contemporary world politics is subject to similar pressures from a wide variety of sub- and supra-national actors, many of which are organized transnationally rather than nationally.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Israel’s survival in the midst of growing chaos appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe case against striking SyriaMoveOn.org and military action in SyriaThe rebirth of international heritage law

Related StoriesThe case against striking SyriaMoveOn.org and military action in SyriaThe rebirth of international heritage law

Burlesque in New York: The writing of Gypsy Rose Lee

In celebration of the anniversary of the first burlesque show in New York City on 12 September 1866, I reread a fun murder mystery, The G-String Murders, by Gypsy Rose Lee. “Finding dead bodies scattered all over a burlesque theater isn’t the sort of thing you’re likely to forget. Not quickly, anyway,” begins the story.

The editors at Simon & Schuster liked the setting in a burlesque theater and appreciated Gypsy’s natural style, with its unpretentious and casual tone. Her knowledge of burlesque enabled her to intrigue readers, who were as interested in life within a burlesque theater as in the mystery. Providing vivid local color, the novel describes comedic sketches, strip routines, costumes, and the happenings backstage. In a typical scene in the book, Gypsy muses about her strip act: “The theater had been full of men, slouched down in their seats. Their cigarettes glowed in the dark and a spotlight pierced through the smoke, following me as I walked back and forth.” Describing her band with precision, she wrote, “Musicians in their shirt sleeves, with racing forms in their pockets, played Sophisticated Lady while I flicked my pins in the tuba and dropped my garter belt into the pit.”

Gypsy worked as hard on her writing as her stripping, and The G-String Murders became a best seller. “People think that just because you’re a stripper you don’t have much else except a body. They don’t credit you with intelligence,” Gypsy later complained. “Maybe that’s why I write.”

Gypsy Rose Lee, full-length portrait, seated at typewriter, facing slightly right, 1956. Photo by Fred Palumbo of the World Telegram & Sun. Public rights given to Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The G-String Murders briefly describes Gypsy’s career as a burlesque queen at a fictitious theater, based on those owned by the Minsky family, in New York City. In the book someone strangles a stripper, La Verne, with her G-string. The police turn up an abundance of suspects, including Louie, La Verne’s gangster boyfriend; Gypsy; and Gypsy’s boyfriend, Biff Brannigan, a comic working in the club. After someone tries to frame Biff by placing the lethal G-string in his pocket, he aids the police in solving the crime. He’s also concerned that the police suspect Gypsy and he wants to clear her by finding the actual murderer. After deducing the identity of the murderer, Biff proves his theory by suggesting that Gypsy act as bait and remains in the theater alone to tempt the murderer to strike again.

More than just a page-turner, Gypsy’s novel stresses the camaraderie among the women. Sharing a dressing room, they throw parties with everyone contributing to buy drinks and food. The women joke, drink together, and confide in each other. The women also sympathize with each other over man problems and working conditions. Gypsy describes the strippers’ dressing room with a complete lack of sentimentality. The cheap theater owner is indifferent to the disgusting condition of the stripper’s dressing room toilet. To help the women, the burlesque comics pool their meager resources to buy the strippers a new toilet.

Gypsy expressed her conviction in the importance of organized labor through a character in The G-String Murders: Jannine, one of the strippers recently elected secretary to the president of the Burlesque Artists’ Association. When the strippers receive a new toilet, the candy seller suggested having a non-union plumber install it to save money. She refuses, forbidding any non-union member to enter the women’s dressing room. She snapped, “Plumbers got a union. We got a union. When we don’t protect each other that’s the end of the unions.” She reminded the other strippers of conditions before they joined a union, when they performed close to a dozen shows without additional compensation.

In the novel, Gypsy provided Jannine with another opportunity to talk about solidarity among burlesque performers and the unequal class structure in the United States. In a tirade against the police over the treatment of the strippers during the murder investigation, Jannine raged that the performers, both the strippers and comedians, might squabble but they were loyal and do not inform on each other. When a police sergeant tried to interrupt her, she retorted: “It’s the social system of the upper classes that gives you guys the right to browbeat the workers!”

Gypsy peddled the G-String Murders in the same clever ways that she publicized herself. In a prepublication letter to her publishers, she offered to “do my specialty in Macy’s window to sell a book. If you prefer something a little more dignified, I’ll make it Wanamaker’s window.” In an interview, she joked that if people did not know her in bookstores, she would remove an earring and ask, “Now, do you recognize me?”

As an added bonus, Gypsy put a lot of herself into this book, so the reader learns quite a bit about her burlesque work life, her sense of humor, her political beliefs, and sense of independence. Spending time with this mystery is a perfect way to celebrate a New York City burlesque anniversary.

Noralee Frankel is author of Stripping Gypsy: The Life of Gypsy Rose Lee. She recently co-edited the U.S. History in Global Perspective for National History Day. Dr. Frankel is a historical consultant and can be reached through LinkedIn or Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Burlesque in New York: The writing of Gypsy Rose Lee appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat about Henry Hudson?Undocumented immigrants in 17th century AmericaContemporary victims of creative suffering

Related StoriesWhat about Henry Hudson?Undocumented immigrants in 17th century AmericaContemporary victims of creative suffering

Learning to sing: lessons from a yogi voice teacher

You know that stress dream that everyone has at one time or another? The one where you’re standing up in front of a giant group of people and something goes horribly wrong? You forget your speech, your voice cracks, you’re not wearing pants. Well that dream became a recurring reality for me my senior year of college (not the pants part thankfully). Mine was the singer’s nightmare. The one where you open your mouth to sing and the voice that comes out is not your own.

As a child and an adolescent I loved to perform. Singing wasn’t something I thought about; it was something I just did and as a result I was totally fearless. When I got to college the concept of thinking about singing as a science was entirely new to me. My teachers taught me to release my jaw and tongue, to inhale into my back and belly, to use muscular antagonism of the inspiratory and expiratory muscles, to keep my larynx low and stable, to lift my palate, and many other mechanics of singing. At first this new focus on technique was interesting, but eventually all of the technical language resulted in confusion. Every time I opened my mouth to sing I was afraid I would do something wrong. The result was a voice that was only a shadow of the one I used to call my own.

What happens when we’re afraid? In his article “The Anatomy of Fear,” John A. Call discusses the body’s reaction to fear: the heart-rate speeds up, our muscles tense, and the breath becomes fast and shallow.

The implications of this for a singer are huge. In singing the first rule of the inhale is release low. When a singer releases and expands through the lower body (belly, low back, and intercostals), it allows these muscles to work in tandem on the exhale. This gives the singer the ability to manage the air much more efficiently than if he/she had begun by expanding through the chest and clavicles. If a person is experiencing fear, the ability to take a low and relaxed or released breath becomes quite difficult.

Certainly singers need to learn proper singing technique, but sometimes I wonder, what is all of this focus on the physical costing us as artists? There was a time in my life when I operated solely on musical intuition. But as I learned more and more about the mechanics of singing I began attempting to operate on facts and science instead of artistic impulse. I don’t mean to suggest that I didn’t need to learn the mechanics—I had plenty of technical issues. But perhaps there is a more holistic approach to teaching singing that could facilitate proper technique without the loss of instinct.

After I graduated from college I took some time off from singing. When I decided to return to it I knew I needed a different approach. I had been practicing yoga as a form of exercise for a few years, but I felt confident that with the right guidance it could really help me as a singer. So I sought out a voice/yoga teacher.

Yoga session at sunrise in Joshua Tree National Park – Warrior I pose. Photo by Jarek Tuszynski. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons

My new teacher, Mark Moliterno, taught me that yoga recognizes that tension in the body is often a result of physical or psychological blockages to the breath. The practice of yoga seeks to release tension and free the breath. When properly implemented in the voice studio, yoga can be a pathway to efficient vocal technique and artistic freedom.

Mark pointed out that all of the confusion and fear that had built up during my college studies had caused me to physically disengage from the lower half of my body. So we set to work using yoga to reconnect me with my lower body and help me feel more secure in my singing.

We used postures like Tādāsana or Mountain Pose and Vìrabhadrāsana One or Warrior One to release tension in the body and connect me with the ground. Feeling my leg muscles engaged and my feet planted firmly on the floor helped me to feel more secure. We used pranayama or breath exercises to release tension within the muscles of the respiratory system. We used hip openers to release the tension in my jaw, and shoulder openers to release the tension in my tongue.

We did yoga and made music. Not once in this entire process did I think about any of the mechanics of singing. My technique improved because my body was open and the breath could function naturally and efficiently. Yoga was like this miracle that freed my voice and allowed me to trust myself again. But it isn’t a miracle, it’s a science that takes into account all parts of the person, and not just the anatomical.

Carrie -Yoga shoot #002. Photo by Joel Nilsson. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons

When singers start trying to function as anatomical machines, seeking after flawless technique, we can lose the ability to sing authentically. Yoga helped me to learn to sing with good technique without focusing on it, and dissolved the fear that kept me from trusting my musical instincts. It released the tension in my body and mind, unleashing the breath, and offering me a pathway to artistic freedom.

Mezzo-soprano, Laura Davis, is a singer, conductor, and voice teacher. She holds a Master of Music degree in Voice Pedagogy and Performance from the Catholic University of America and a Bachelor of Music degree in Sacred Music from Westminster Choir College. Recent performances include Suzuki in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, Dina in Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti, and Third Lady in Mozart’s The Magic Flute. After spending 10 years on the east coast conducting, performing, and teaching, Ms. Davis has returned to her home state of Colorado where she is in the process of opening a voice studio based on a holistic approach to singing.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Learning to sing: lessons from a yogi voice teacher appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesKeith Moon thirty-five years onThe lark ascends for the Last NightInterpreting Chopin on piano - Enclosure

Related StoriesKeith Moon thirty-five years onThe lark ascends for the Last NightInterpreting Chopin on piano - Enclosure

September 9, 2013

The case against striking Syria

Chemical weapons are horrendous agents. Small amounts can kill and severely injure hundreds of people in a matter of minutes, as apparently occurred recently in Syria. Some analysts consider them “poor countries’ nuclear bombs.” The international community has, with the Chemical Weapons Convention, banned their use, development, production, acquisition, stockpiling, retention, and transfer. Nevertheless, several countries have continued to develop, produce, acquire, stockpile, retain, and transfer these weapons.

Chemical weapons were used on a wide scale during World War I and were also used during World War II. Saddam Hussein used them in Iraq in the 1980s to crush internal opposition to his regime. A terrorist cult in Japan used them twice in the mid-1990s, killing 20 people and injuring hundreds. Now they have been used in Syria — maybe more than once.

Chemical weapons were used on a wide scale during World War I and were also used during World War II. Saddam Hussein used them in Iraq in the 1980s to crush internal opposition to his regime. A terrorist cult in Japan used them twice in the mid-1990s, killing 20 people and injuring hundreds. Now they have been used in Syria — maybe more than once.

Their use in Syria cannot go unchecked. But that is not the issue before the US Congress. The issue is whether or not President Obama should authorize the “limited” use of cruise missiles, launched from US ships in the eastern Mediterranean, to “degrade” Syrian President Assad’s ability to launch additional attacks.

There are three reasons why we oppose such a strike.

First, such an attack by the United States would likely violate international law and undermine the United Nations’ ability to enforce the Chemical Weapons Convention. The report of UN weapons inspectors who investigated the recent attack has not yet been issued. The United States does not have the right to enforce international treaties — militarily or by other means.

Second, a strike by the United States would have uncertain consequences within Syria. It is likely to kill and injure noncombatant women, men, and children. It may lead President Assad or others in Syria to use chemical weapons in retaliation. And it may lead to wider access to the massive store of chemical weapons there, leading to further use of chemical weapons in Syria — and beyond.

Third, and most importantly, such a strike by the United States would have uncertain consequences throughout the Middle East and beyond. It could lead to a much wider war in this region, where there is an overabundance of weapons supplied by the United States, Russia, and other countries. Such a strike would be equivalent to tossing a match into a barrel of gasoline. There is already much conflict in this region within countries, most prominently within Egypt and Iraq, and there is much potential conflict between countries. The reaction by several countries and non-state actors in the Middle East (and beyond) to a US strike cannot be predicted, but there is a predictably high likelihood of a miscalculation, or a whole series of miscalculations, that could easily lead to a much wider conflagration. We should remember that the assassination of one person ignited World War I.

The civil war in Syria, which has already led to more than 100,000 deaths and two million refugees, cries out for a nonmilitary solution. There needs to be a response to the chemical weapons attack there, but it should be an international nonmilitary response — not a US cruise missile attack that is likely do more harm than good. The suddenly increased focus on the civil war in Syria represents an opportunity for the international community to find ways to end this conflict and to promote peace in the region.

Barry S. Levy, MD, MPH, and Victor W. Sidel, MD, are co-editors of the following books, each in its second edition, published by Oxford University Press: War and Public Health, Terrorism and Public Health, and Social Injustice and Public Health. They are both past presidents of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Levy is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Sidel is Distinguished University Professor of Social Medicine Emeritus at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein Medical College and an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cover of the Chemical Weapons Convention used for the purposes of illustration via opcw.org.

The post The case against striking Syria appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy Parliament matters: waging war and restraining powerSocial injustice and public health in AmericaMoveOn.org and military action in Syria

Related StoriesWhy Parliament matters: waging war and restraining powerSocial injustice and public health in AmericaMoveOn.org and military action in Syria

Six methods of detection in Sherlock Holmes

Between Edgar Allan Poe’s invention of the detective story with The Murders in the Rue Morgue in 1841 and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes story A Study in Scarlet in 1887, chance and coincidence played a large part in crime fiction. Nevertheless, Conan Doyle resolved that his detective would solve his cases using reason. He modeled Holmes on Poe’s Dupin and made Sherlock Holmes a man of science and an innovator of forensic methods. Holmes is so much at the forefront of detection that he has authored several monographs on crime-solving techniques. In most cases the well-read Conan Doyle has Holmes use methods years before the official police forces in both Britain and America get around to them. The result was 60 stories in which logic, deduction, and science dominate the scene.

FINGERPRINTS

Sherlock Holmes was quick to realize the value of fingerprint evidence. The first case in which fingerprints are mentioned is The Sign of Four, published in 1890, and he’s still using them 36 years later in the 55th story, The Three Gables (1926). Scotland Yard did not begin to use fingerprints until 1901.

It is interesting to note that Conan Doyle chose to have Holmes use fingerprints but not bertillonage (also called anthropometry), the system of identification by measuring twelve characteristics of the body. That system was originated by Alphonse Bertillon in Paris. The two methods competed for forensic ascendancy for many years. The astute Conan Doyle picked the eventual winner.

TYPEWRITTEN DOCUMENTS

As the author of a monograph entitled “The Typewriter and its Relation to Crime,” Holmes was of course an innovator in the analysis of typewritten documents. In the one case involving a typewriter, A Case of Identity (1891), only Holmes realized the importance of the fact that all the letters received by Mary Sutherland from Hosmer Angel were typewritten — even his name is typed and no signature is applied. This observation leads Holmes to the culprit. By obtaining a typewritten note from his suspect, Holmes brilliantly analyses the idiosyncrasies of the man’s typewriter. In the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) started a Document Section soon after its crime lab opened in 1932. Holmes’s work preceded this by forty years.

HANDWRITING

Conan Doyle, a true believer in handwriting analysis, exaggerates Holmes’s abilities to interpret documents. Holmes is able to tell gender, make deductions about the character of the writer, and even compare two samples of writing and deduce whether the persons are related. This is another area where Holmes has written a monograph (on the dating of documents). Handwritten documents figure in nine stories. In The Reigate Squires, Holmes observes that two related people wrote the incriminating note jointly. This allows him to quickly deduce that the Cunninghams, father and son, are the guilty parties. In The Norwood Builder, Holmes can tell that Jonas Oldacre has written his will while riding on a train. Reasoning that no one would write such an important document on a train, Holmes is persuaded that the will is fraudulent. So immediately at the beginning of the case he is hot on the trail of the culprit.

FOOTPRINTS

Holmes also uses footprint analysis to identify culprits throughout his fictional career, from the very first story to the 57th story (The Lion’s Mane published in 1926). Fully 29 of the 60 stories include footprint evidence. The Boscombe Valley Mystery is solved almost entirely by footprint analysis. Holmes analyses footprints on quite a variety of surfaces: clay soil, snow, carpet, dust, mud, blood, ashes, and even a curtain. Yet another one of Sherlock Holmes’s monographs is on the topic (“The tracing of footsteps, with some remarks upon the uses of Plaster of Paris as a preserver of impresses”).

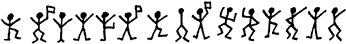

CIPHERS

Sherlock Holmes solves a variety of ciphers. In The “Gloria Scott” he deduces that in the message that frightens Old Trevor every third word is to be read. A similar system was used in the American Civil War. It was also how young listeners of the Captain Midnight radio show in the 1940s used their decoder rings to get information about upcoming programs. In The Valley of Fear Holmes has a man planted inside Professor Moriarty’s organization. When he receives an encoded message Holmes must first realize that the cipher uses a book. After deducing which book he is able to retrieve the message. This is exactly how Benedict Arnold sent information to the British about General George Washington’s troop movements. Holmes’s most successful use of cryptology occurs in The Dancing Men. His analysis of the stick figure men left as messages is done by frequency analysis, starting with “e” as the most common letter. Conan Doyle is again following Poe who earlier used the same idea in The Gold Bug (1843). Holmes’s monograph on cryptology analyses 160 separate ciphers.

DOGS

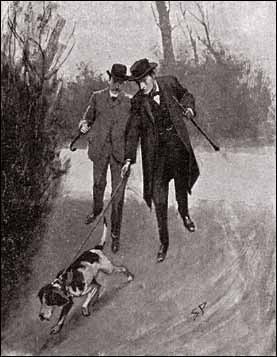

Conan Doyle provides us with an interesting array of dog stories and analyses. The most famous line in all the sixty stories, spoken by Inspector Gregory in Silver Blaze, is “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” When Holmes directs Gregory’s attention to “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time,” Gregory is puzzled by this enigmatic clue. Only Holmes seems to realize that the dog should have done something. Why did the dog make no noise when the horse, Silver Blaze, was led out of the stable in the dead of night? Inspector Gregory may be slow to catch on, but Sherlock Holmes is immediately suspicious of the horse’s trainer, John Straker. In Shoscombe Old Place we find exactly the opposite behavior by a dog. Lady Beatrice Falder’s dog snarled when he should not have. This time the dog doing something was the key to the solution. When Holmes took the dog near his mistress’s carriage, the dog knew that someone was impersonating his mistress. In two other cases Holmes employs dogs to follow the movements of people. In The Sign of Four, Toby initially fails to follow the odor of creosote to find Tonga, the pygmy from the Andaman Islands. In The Missing Three Quarter the dog Pompey successfully tracks Godfrey Staunton by the smell of aniseed. And of course, Holmes mentions yet another monograph on the use of dogs in detective work.

Conan Doyle provides us with an interesting array of dog stories and analyses. The most famous line in all the sixty stories, spoken by Inspector Gregory in Silver Blaze, is “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” When Holmes directs Gregory’s attention to “the curious incident of the dog in the night-time,” Gregory is puzzled by this enigmatic clue. Only Holmes seems to realize that the dog should have done something. Why did the dog make no noise when the horse, Silver Blaze, was led out of the stable in the dead of night? Inspector Gregory may be slow to catch on, but Sherlock Holmes is immediately suspicious of the horse’s trainer, John Straker. In Shoscombe Old Place we find exactly the opposite behavior by a dog. Lady Beatrice Falder’s dog snarled when he should not have. This time the dog doing something was the key to the solution. When Holmes took the dog near his mistress’s carriage, the dog knew that someone was impersonating his mistress. In two other cases Holmes employs dogs to follow the movements of people. In The Sign of Four, Toby initially fails to follow the odor of creosote to find Tonga, the pygmy from the Andaman Islands. In The Missing Three Quarter the dog Pompey successfully tracks Godfrey Staunton by the smell of aniseed. And of course, Holmes mentions yet another monograph on the use of dogs in detective work.

James O’Brien is the author of The Scientific Sherlock Holmes. He will be signing books at the OUP booth 524 at the American Chemical Society conference in Indiana on 9 September 2013 at 2:00 p.m. He is Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Missouri State University. A lifelong fan of Holmes, O’Brien presented his paper “What Kind of Chemist Was Sherlock Holmes” at the 1992 national American Chemical Society meeting, which resulted in an invitation to write a chapter on Holmes the chemist in the book Chemistry and Science Fiction. He has since given over 120 lectures on Holmes and science. Read his previous blog post “Sherlock Holmes knew chemistry.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) From “The Adventure of the Dancing Men” Sherlock Holmes story. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Missing Three-Quarter.” Illustration by Sidney Paget. Strand Magazine, 1904. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Six methods of detection in Sherlock Holmes appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSherlock Holmes knew chemistryThe ghost of Sherlock HolmesUnderstanding the history of chemical elements

Related StoriesSherlock Holmes knew chemistryThe ghost of Sherlock HolmesUnderstanding the history of chemical elements

MoveOn.org and military action in Syria

Last week, MoveOn.org announced its opposition to President Obama’s proposed military strikes in Syria. MoveOn will now begin mobilizing its eight million+ members to speak out against the Syrian action, and is already planning rallies around the country. As an early organizational supporter of Obama (MoveOn first endorsed him for President on 1 February 2008, back when most Democrats expected Hillary Clinton to become the nominee) this comes as a particularly important signal of progressive discontent with bombing the Assad military regime.

MoveOn did not reach this decision lightly. The organization has a longstanding record as an anti-war organization. Much of its early membership growth occurred in 2002-2003, as an outlet for protests against the Iraq War. Yet its opposition to limited bombings within Syria were not reached lightly. They came after a long cycle of member engagement and discussion. The most interesting element of this decision is likely what it tells us about how new political organizations use digital technologies to listen in novel ways.

Most political associations have taken no stance on the Syria debate. That’s understandable. International conflicts, human rights abuses, and civil wars abroad are outside the expertise of the AARP, NRA, and Environmental Defense Fund. Taking a stance on international conflicts can anger a lot of supporters without furthering the organization’s core goals.

Traditional, single-issue advocacy organizations face a simple choice when facing a complicated new public debate. Option 1: Ignore the topic, remaining focused on your primary area of expertise. Option 2: Rely on senior staff to take a stance and draft a statement. The hallmark of traditional advocacy groups is concentrated expertise. Members write checks. Expert staffers convert those financial resources into political influence within a small sphere of public affairs.

“Netroots” organizations like MoveOn tend to be multi-issue generalists rather than single-issue specialists. They aim to give voice to public sentiment while an issue is receiving public scrutiny. Ignoring a topic like Syria while it is in the center of public debate cuts against the very nature of these digitally-mediated advocacy organizations.

So how does a netroots organization like MoveOn arrive at its policy stance?

They began on 31 August 2013 with a mass email to their membership, titled “Syria.” The message included a link to a “Video teach-in,” where five experts on Middle East politics debated the pros and cons of the proposed limited missile strike. It also encouraged members to make their voices heard, by starting or signing petitions on the organization’s website. The user-generated petition platform allows for a form of deliberative discourse, as petition signatures provide a signal about which arguments and policy options are most preferable. Finally, the message encouraged members to donate to Doctors Without Borders, a nonprofit providing emergency healthcare inside Syria through six field hospitals.

As members visited the video teach-in and signed one another’s petitions, MoveOn staff also sent out surveys to a random subset of MoveOn members, asking for more detailed feedback on what stance and activities they would support.

On 3 September 2013, the staff called for a membership-wide email vote. Over 100,000 members weighed in over the next 24 hours, and 73% urged the organization to actively oppose the use of military force in Syria. Only then did MoveOn make its announcement that it would oppose Obama’s military strikes. Digital technologies provided three strong signals — user-generated petition activity, detailed member surveys, and a full-membership vote — all in the space of a few days.

Some remain skeptical about these digital engagement tools. Micah Sifry, of Personal Democracy Forum, offers an insightful challenge with his article “You Can’t A/B Test Your Response to Syria.” He writes:

“…while the e-groups are best equipped to move quickly in response to breaking events compared to their older forbears, Syria isn’t an issue like, say, the crackdown on labor rights in Wisconsin, or the Trayvon Martin killing, or the Texas abortion rights fight, where the progressive response was fairly clear and the main thing the managers of these groups had to do was fine-tune their calls to action.

To put it in a sentence, the answer to Syria can’t be A/B tested. But unfortunately for online activists, that’s the only really good tool in their toolbox. And now, to mangle metaphors, they’re playing a weaker hand than they might because of how that tool shapes their work. That is, they’re either admitting their ‘membership’ is divided or confused, or they’re papering over those issues with snap surveys.”

Sifry’s main point is a good one: after 10-15 years of netroots advocacy, one could hope for even better platforms for online deliberation than the ones we see on display from MoveOn and its ilk. Indeed, many digital advocacy professionals seem to agree that tools currently on display for online member deliberation pale in comparison to the tools they would one day like to build. Sifry’s argument is, in essence, that we aren’t getting there nearly fast enough.

But these new tools of online sentiment analysis (what I call “passive democratic feedback”) nonetheless represent a remarkable shift in how political associations make decisions. Gone are the days when major issues of public importance are blithely ignored by our leading advocacy organizations. Gone are the days when a select few senior staff dictate all of the decisions from on high. MoveOn’s Syria announcement is based in massive, careful efforts to use technology for digital listening.

Despite the commonplace accusations is rendering activism light, fleeting, and ineffectual, a deeper look at netroots advocacy groups reveals that our new, digital organizations are, in fact, the best representative.

David Karpf is an Assistant Professor in the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. He is the author of The MoveOn Effect: The Unexpected Transformation of American Political Advocacy. His research focuses on the Internet’s disruptive effect on organized political advocacy. He blogs at shoutingloudly.com and tweets at @davekarpf.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: democracy concept with vote button on keyboard. © gunnar3000 via iStockphoto.

The post MoveOn.org and military action in Syria appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy Parliament matters: waging war and restraining powerPunitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane interventionThe rebirth of international heritage law

Related StoriesWhy Parliament matters: waging war and restraining powerPunitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane interventionThe rebirth of international heritage law

The rebirth of international heritage law

In June this year, developments around the Great Barrier Reef were excitedly discussed and closely scrutinized by the World Heritage Committee, a subsidiary organ of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). More specifically, the region around the reef, mineral-rich soil in northeastern Queensland (Australia), has been developed by Australian and foreign mining companies. So the coal, Australia’s second largest export (amassing a whopping AUD 46.8 billion in 2011), can actually head to countries like China, ports as needed. The world’s largest coal-exporting port just so happens to be nearby.

The development of ports requires dredging, and that dredged soil is usually dumped at sea. The soil, rich in heavy metals, releases those metals into the water, and they slowly drift on to reefs, killing coral life.

Why does the World Heritage Committee care? Well the Great Barrier Reef is on the World Heritage List, along with 980 other properties in 160 countries around the world. Does that automatically give the World Heritage Committee, a body whose headquarters is in Paris, and just so happened to be sitting in Cambodia last June, any authority to tell the Australian people and government that they cannot fully exploit their natural resources, in pursuance of their right to Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources?

As it turns out, yes. That is what international heritage does: creates exceptions to States’ sovereign rights so certain goods, deemed worthwhile, can be safeguarded for generations to come. UNESCO, established in 1946, has since its establishment pursued the objective of protecting and safeguarding heritage. To this effect, it has passed on a number of international instruments, including recommendations, declarations, and a number of treaties. Of these, five are particularly relevant:

The 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict

The 1970 Convention on the Exports and Traffic of Cultural Property

The 1972 World Heritage Convention

The 2001 Underwater Cultural Heritage Convention

The 2003 Intangible Heritage Convention

These conventions, spanning 50 years, present on their own an important record of the evolution of this field of international law, and of international law more generally.

When it comes to the field specifically, the titles of these instruments alone already signal to one of the most important changes, the shift from cultural property to cultural heritage. This shift means distancing from notions of property and ownership, and a move towards stewardship of these goods. They mirror, to a certain extent, the consolidation of human rights internationally, which, at least if Samuel Moyn is to be believed, only really took off in the 1970s.

More importantly, and closely related, this shift also prefaces a shift that took place in the field in 2003, when the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention was approved. This instrument had been in the minds of some for a long time: the first mention to the need for such a convention dates back at least to the 1970s. And it responds to an important gap: protecting cultural manifestations which do not necessarily have a permanent physical presence. The fact that they do not have a permanent physical presence does not mean they are any less important than, say, the Great Barrier Reef. They are in fact perhaps even more important, as they are closely connected to identity. Because intangible heritage does not exist externally, it must exist internally, close to the heart of identity.

Also known as living cultures, intangible cultural heritage means “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity. For the purposes of this Convention, consideration will be given solely to such intangible cultural heritage as is compatible with existing international human rights instruments, as well as with the requirements of mutual respect among communities, groups and individuals, and of sustainable development.”

More specifically, it safeguards heritage as a process, as opposed to its icons. Physical manifestations of heritage are important, to be sure, but what matters most is how people connect to heritage, and the ways in which this connection influences people’s relationship to the environment, to human rights, and others. This notion reinforces the shift in UNESCO away from heritage as a symbol of sovereignty to heritage as a symbol of shared humanity. In international law more generally, it is another instance of the erosion of sovereignty in favor of a cosmopolitan ideal where peoples, and not necessarily States, coexist in full harmony.

This brings us back to the Great Barrier Reef. Protected under the World Heritage Convention, it is still formally protected as a site, and not as a process to which people feel connected. However, people’s connections to their heritage, and the process through which this connection is entrenched, is becoming more and more part of the equation even in protecting heritage. The notion of heritage as a process, enshrined in the 2003 Intangible Heritage Convention, is spreading to other heritage regimes, and triggering the rebirth of the field, from monuments and sites to living cultures. In the Great Barrier’s case, it is now less about the Reef itself than it is about what it means for our shared humanity. The good at stake is not only coral reefs, it is now the Reef standing for a humanity hopeful in a sustainable future, hopeful in reverting the negative effects of development, and saving the reef from ourselves, for the sake of present and future generations.

Lucas Lixinksi is a Lecturer at the University of New South Wales and is author of Intangible Cultural Heritage in International Law, part of the newly launched Cultural Heritage Law and Policy series.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Great Barrier Reef. Photo by NickJ. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The rebirth of international heritage law appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesReinvention of hybrid business enterprises for social goodPunitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane interventionRemembering the slave trade

Related StoriesReinvention of hybrid business enterprises for social goodPunitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane interventionRemembering the slave trade

A folklore and fairy tales reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

By Jessica Harris

This month our Oxford World’s Classics reading list is on folk and fairy tales. Many of these stories pre-date the printing press, and most will no doubt continue to be told for hundreds of years to come. How many of these have you heard of, and have we missed out your favourite? Let us know in the comments.

No list on folklore would be complete without Beowulf: probably the most famous English folk tale and a great story. This half-historical, half-legendary epic poem written by an unknown poet between the 8th and 11th century tells the story of the majestic hero Beowulf, who saves Hrothgar, the Danish king, from monstrous and terrifying enemies before eventually being slain. Through this tale of swashbuckling adventure we also see the power struggles and brutality of medieval politics.

Selected Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

In 1812 the Brothers Grimm took contemporary German folk tales and shaped them in their own bloodthirsty way, and in doing so captivated and horrified children for years to come. There are no morals here; no happy endings – the antagonists such as the evil stepmother won’t just steal your sweets but would kill you without a second thought. Here we have, for example, the original Snow White, with the Witch forced to dance in red-hot shoes until her death.

Le Morte Darthur by Thomas Malory

This text, written by Sir Thomas Malory in 1470, provides us with the definitive version of many of the King Arthur stories: the Knights of the Round Table, Sir Lancelot’s betrayal, and the Quest for the Holy Grail. Here we see the Round Table full of warring factions; we see Arthur the King discredited by Lancelot, who begins an affair with his wife, Guinevere, and we see Arthur’s supporters’ revenge that Arthur is powerless to prevent. The book shows how Arthur and his court lived and felt – and it’s no wonder the legend is such a fundamental part of British culture.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

When the mysterious Green Knight turns up at King Arthur’s court and challenges anyone to strike him with his axe and accept a return blow in a year and a day, Sir Gawain, the youngest Knight in Sir Arthur’s court, decides to prove his mettle by accepting the challenge. However, when he strikes the Green Knight and beheads him, the man laughs, picks up his head and tells Gawain he has a year and a day to live. Despite being written in the fourteenth century, this poem’s main theme – proving yourself – makes it instantly relatable and compelling.

Statue of Hans Christian Andersen reading The Ugly Duckling, in Central Park, New York City

Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales by Hans Christian AndersenThis collection of fairy tales is a world away from Grimm’s violent and sinister collection – this Danish author was the creator of charming, accessible stories such as The Ugly Duckling and the Emperor’s New Clothes. Despite being poorly received when they were first published in 1936 because of their informality and focus on being amusing rather than educational, these stories have entertained generations of children. Christian Andersen invented the “fairy tale” as we know it today – simple, timeless stories that explore universal themes and end happily.

Eirik the Red and Other Icelandic Sagas

This saga was originally told orally around 1000 CE and was written down in the thirteenth or fourteenth century and is a major landmark in Icelandic folk literature. It tells the story of Eirik’s exile for murder, the same fate as his father, and his discovery and settlement in “Vinland”, a lush, plentiful country. It is believed to describe one of the first discoveries of North America, five hundred years before Captain Cook.

This epic comes from Medieval Germany and is a masterpiece of fantasy storytelling. Written in 1200 but rediscovered in the 1700s, it has since become the German national epic – on a par with the Iliad or the Ramayana. This story has it all: dragons, invisibility cloaks, fortune telling, and hoards of treasure guarded by dwarves and giants. We see love, jealousy and conflict, and the story ends with awful slaughter. The story has inspired a number of adaptations, including Wagner’s Ring cycle.

The Mabinogion is a collection of eleven medieval Welsh stories which combine Arthurian legend, Celtic myth and social narrative to create an epic series – its importance as a record of the history of culture and mythology in Wales is enormous. The stories are fantastical: the Four Branches of the Mabinogi are tales about British pagan gods recreated as human heroes, and sociological: The Dream of Macsen Wledig is an exaggerated story about the Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus.

Jessica Harris graduated from Warwick University with a degree in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics and has been working as an intern in the Online Product Marketing department in the Oxford office of Oxford University Press.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Statue of Hans Christian Andersen reading The Ugly Duckling, in Central Park, New York City. By Dismas (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The post A folklore and fairy tales reading list from Oxford World’s Classics appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe poetry of Federico García Lorca10 questions for David GilbertWalter Scott’s anachronisms

Related StoriesThe poetry of Federico García Lorca10 questions for David GilbertWalter Scott’s anachronisms

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers