Oxford University Press's Blog, page 907

September 2, 2013

Pension fund divestment is no answer to Russia’s homophobic policies

By Edward Zelinsky

A group of California state senators, including senate president pro Tem Darrell Steinberg, has called for California’s public employee pension plans to protest Russia’s homophobic laws and policies by ceasing to make Russian investments. While the senators are right to denounce Russia’s assault on human rights, they are wrong to call for the divestment of the Golden State’s public pension funds. The divestment of pension funds is not a proper means of advancing this or any other political protest, as meritorious as such protest may be.

Pension fiduciaries should invest pension resources solely to generate prudent, diverse, and productive returns to finance employees’ retirement benefits. Pension funds should not be used to promote other agendas, as worthy as those alternative agendas may be.

Public pension plans are a tempting target for advocates of various political and social goals. These advocates often act in good faith and frequently promote compelling objectives. However, the use of public pension funds to pursue alternative agendas is inappropriate, even to advance the most commendable of goals. Pension funds should be used to finance employees’ retirement benefits — period.

Similar efforts to divert public pension funds occurred in the wake of the Newtown massacre. To protest gun violence, pension funds in New York City, Chicago, and California sold their stocks in gun manufacturers. In that situation also, a compelling public policy goal — the reduction of gun violence — was pursued by inappropriate means, namely, the divestiture of public pension funds.

For two reasons, such divestiture is wrong. First, it is futile. When a pension plan sells its investments, someone else buys them. If the California public pension plans sell their Russian investments or decline to make such investments, someone else will purchase these investments. This game of musical chairs shuffles ownership but has no net economic impact.

Second, the use of pension funds for Cause A opens the door to the use of such funds for Cause B. If California pensions sell their Russian investments as they sold their gun stocks, there is no reason to stop there. The world is full of good causes. There are also causes with which I disagree but which are sincerely advocated by their supporters. There is no principled limit to pension fund divestiture once it starts.

For this reason, the law has evolved the fiduciary principle variously known as the duty of loyalty or as the exclusive benefit rule. Under this time-honored tenet, pension trustees can only invest pension funds to advance the financial welfare of retirees.

The precarious financial state of California’s pension plans demonstrates the wisdom of this fiduciary rule. The Golden State’s public pensions are seriously underfunded. This underfunding is ignored in Sacramento by assuming unrealistic rates of return. California’s pensions shouldn’t be used to pursue social agendas, even worthy ones. California’s pension trustees should invest pension resources to maximize prudent financial returns, not to pursue other agendas.

Senator Steinberg and his colleagues implicitly admit the validity of this critique, acknowledging that California’s pension trustees should only avoid Russian investments if such avoidance is “consistent with their fiduciary responsibilities.” However, it is never consistent with a pension trustee’s fiduciary responsibilities to make investment decisions on political or social policy grounds — as compelling as those grounds may be. Pension trustees should invest the funds committed to their care solely to provide retirement benefits.

Individuals, of course, should spend their own money as they like and should invest their own funds (including their IRAs and self-directed 401k accounts) as they see fit. If someone offered me a free trip to the Russian Olympics (no one has), I would say “no thanks” for the reasons Senator Steinberg and his colleagues articulate: to protest the use of “government as an instrument of discrimination [and] persecution.”

But that would be my individual decision relative to my own resources. A pension trustee’s fiduciary duty is not to pursue his own sense of right or wrong with plan resources, but to maximize the financial return to the plan and its participants.

I stand with Senator Steinberg and his colleagues in protesting Russia’s assault on human rights. But I respectfully disagree that public pension funds are proper instruments for advancing this or any similar protest.

Edward A. Zelinsky is the Morris and Annie Trachman Professor of Law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law of Yeshiva University. He is the author of The Origins of the Ownership Society: How The Defined Contribution Paradigm Changed America. His monthly column appears on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Pension pension or retirement concept with word on business office folder index. Photo by gunnar3000, iStockphoto.

The post Pension fund divestment is no answer to Russia’s homophobic policies appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesPunitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane interventionCan supervisors control international banks like JP Morgan?The dawn of a new era in American energy

Related StoriesPunitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane interventionCan supervisors control international banks like JP Morgan?The dawn of a new era in American energy

Buddhism or buddhisms: mirrored reflections

In terms of the way Buddhism is academically apprehended, the implication of Johan Elverskog’s argument in “The Buddhist Exchange: Irrigation, Crops and the Spread of the Dharma” — that Buddhism should be seen as a civilization — runs directly counter to the standard view of the relation between civilization and religion codified in contemporary religious studies. In the “standard model” a civilization is conceptualized as the societal container within which different religions may be held. This conception is no doubt a consequence of the ways in which Europe secularized in order to deal with the otherwise intractable wars of religion, which stretched across a century and a half (1524–1697). While it is the normative conception of the relation for post-Enlightenment liberal societies in the West, we cannot presume that it was so for all peoples at all times.

Such a theoretical conception of Buddhism as a civilization would do much to shift away from an almost exclusive focus on Buddhist doctrine, with its implicit cognitivist fallacy, while at the same time avoiding the Buddhist modernist notion that meditation can be adopted sanitized of any doctrinal commitments. The tension between these two opposing understandings of what is important about Buddhism appears unresolvable. A shift to a category other than “religion” or “philosophy” would provide a means of comprehending Buddhism more adequately.

Consider for example the translators who judged texts of the “profane sciences” worthy of translation from Sanskrit into Tibetan. While a distinction was drawn between that which is directly conducive to awakening, and that which is indirectly conducive, it was the entire culture of the Buddhist civilization that was of interest. Even more telling in their specificity, however, are the debates between different Tibetan teachers on the question of whether epistemology (hetuvidyā, grtan tshigs rig pa) is properly one of the sciences conducive to awakening or not. Thus, not only do the boundaries between “sacred and profane” trace out different contours in Buddhist thought (“awakening” having a different intellectual configuration from “salvation”), but also the borders are not sharp. Additionally, making the distinction between “religion” (sacred) and “civilization” (profane) turns out to have been an area of contestation.

Photo by Roberto Trm. Creative Commons License via Roberto Trm’s Flickr.

Anya Bernstein’s research highlights the difference between emic bases for categorization among contemporary Buryat Buddhists and the etic categories predominant in contemporary academia. As discussed previously, the default academic categories tend to be based on contemporary nation-states. Thus, we find much talk of Chinese Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism, Burmese Buddhism, and so on. For the Buryats studied by Bernstein, however, connections are based not on nation states. (Tibet, for example, is a problematic category, as David B. Gray’s discussion, summarized in the previous post, showed.) Rather, they rest on “karmic affinities,” that is, those of teaching lineages and reincarnation. Since these ways of categorizing socio-religious groupings are also used by at least some Buddhists themselves, they are an important additional system for contemporary researchers to take into account.

At the same time, the relevance of ethnic and nationalistic categories also emerges from Bernstein’s study. These are especially clear in conflicts between the authority of the officially recognized Buryat Buddhist establishment and the ethnically Tibetan lamas who operate on the basis of relations that not only cross, but effectively deny the religious significance of national boundaries. One dimension of this conflict is that of “tradition versus reform,” with the Tibetan lamas and their supporters asserting authority from within a modernist rhetoric of reforming and purifying, while their opponents based their claims on a politics of identity and tradition. The specific site of conflict discussed by Bernstein was ritual offerings to local deities which traditionally include vodka and meat. The Tibetan lamas asserted that “true” Buddhism, that is, a modernist claim regarding originary purity, did not include such offerings, while the local lamas claimed that the indigenous spirits would not take orders from outsiders. Thus, the conflict reveals that categories based on nation-states are not irrelevant to the study of Buddhism. However, rather than being employed uncritically as the default organizing principles, such categories need to be used for situations in which they are appropriate.

Gray’s inquiry on “How Tibetan is Tibetan Buddhism?” points to an alternative structure by which the study of Buddhism can be organized, that of religious movements and schools. Like Vajrayāna itself, the category Gray suggests as an alternative to “Tibetan Buddhism,” other important movements and schools extend across cultural boundaries. These extensions, such as the cult of Amitābha extending throughout the Mahāyāna cosmopolis, are important for understanding the coherence of the tradition—a characteristic ignored, obscured or minimalized by emphases on the characteristics thought to unify the variety of Buddhist forms within a nation-state.

The category “Tibetan Buddhism” appears firmly entrenched in popular culture. Thus, one sees groupings such as “Zen, Tibetan and mindfulness” as if these represented the range of Buddhism. On the one hand, this reveals the tendency of accepted categories to endure despite being dysfunctional in one way or other. On the other, it highlights another aspect of the social structures sustaining such categories. In other words, the popular formulations of the categories of Buddhism directly affect the academic categorizations. The popular formulations stand then in a dialectic relation to the scholarly categories, with both being influenced by the economics of popular religion on the one hand and the funding of academic institutions on the other.

As summarized in the previous post, Tansen Sen’s essay on “Rediscovering and Reconstructing Buddhist Interactions between ‘India’ and ‘China’” explores the ways in which modern political ends were at work in reimagining an historical relationship between an India and a China that serve as symbolic surrogates for the modern nation-states. This relationship was represented as one of peaceful sharing in which Buddhism was both the content being shared and the motivator for the sharing. The pan-Asianist rhetoric that Sen examines formed a common discourse among many different authors in late nineteenth and early twentieth century South and East Asia. Sen specifically focuses this paper on figures working at Cheena-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, India, in the 1930s and 40s. When considering the effects of using contemporary nation-states as the default organizing principle for Buddhist studies, Sen makes an important observation:

“The use of ‘India’ and ‘China’ as distinct, homogenous, and ‘politically identifiable’ units found in the writings of intellectuals and scholars associated with pan-Asianism and Cheena-Bhavana was not necessarily due to the limitations of modern vocabulary. Rather, they were deliberately used to accomplish the idealistic, nationalistic, political, or religious goals of these writers. The reconstructions of the ancient linkages between India and China were often part of the emerging nationalist historiography that let the concerns of the present shape the perceptions of the past.”

In addition to the endurance of these directly politicized motivations regarding “India” and “China” as monolithic constructs continuous over millennia, another implication of Sen’s study is worth considering. The goal of early twentieth century pan-Asianist rhetoric was to imagine a peaceful relation between Asian countries, in this case based on Buddhism. As indicated above, not only was Buddhism the content of exchange, but it was also presented as the motivator of change. In other words, the contemporary image of Buddhism as a “religion of peace” may itself also be a consequence of the pan-Asianist rhetoric examined by Sen.

Categories have lexical and rhetorical consequences, and should only be used when theoretically relevant. There is no one right way to categorize Buddhism—whether in terms of nations or ethnicities, lineages or mentalités, monastic institutions or doctrinal teachings, civilizations or individuals. Each of these, and other kinds of categorizations, can be heuristically useful for different kinds of research depending upon the theoretical framework of inquiry. Employing any of them as the single overarching default category system, however, distorts and limits our understanding.

Richard K. Payne is the Dean of the Institute of Buddhist Studies at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley; serves as Editor-in-Chief of the Institute’s annual journal, Pacific World; is chair of the Editorial Committee of the Pure Land Buddhist Studies Series; and is Editor-in-Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Buddhism. He also sporadically maintains a blog entitled “Critical Reflections on Buddhist Thought: Contemporary and Classical.” Read his previous OUPblog posts.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Buddhism or buddhisms: mirrored reflections appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesBuddhism beyond the nation stateCops and Robbers Redux10 facts about Galileo Galilei

Related StoriesBuddhism beyond the nation stateCops and Robbers Redux10 facts about Galileo Galilei

Punitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane intervention

The 1949 Geneva Conventions do not justify US missile strikes in Syria in response to chemical weapons attacks on the civilian population. The humanitarian principle of distinction prohibits the targeting of civilians, but does not sanction the decision to launch a military campaign responding to such attacks. International humanitarian law thus governs the conduct of war but not its initiation. Rules governing the initiation of war occur against a backdrop of international law favoring the peaceful resolution of conflict and the provision of life-saving forms of assistance to civilian victims of war.

To determine if international law permits the launching of US military strikes in Syria, it is the UN Charter, and not the Geneva Conventions, which must guide the US government and the American people. Use of force rules, originating in customary international law, and partially codified in the UN Charter, establish the lawful framework for the initiation of military activities by a government, with or without a formal declaration of war. Whether US military intervention is unilateral or multilateral, short-term or sustained, surgical or full court press, sea or air-based, utilizing Tomahawk missiles or Predator drones, the UN Charter is our framework and our guide.

Article 2, clause 4 of the UN Charter is the source of the general prohibition against the use of force, one of the cardinal principles of international law since 1945, given pride of place in a treaty dedicated to ending the “scourge of war.” But the Charter is not starry-eyed about the prospects of outlawing war, and contemplates two very pragmatic exceptions to the general prohibition. The first, explicitly codifying a long-standing customary norm, is the use of force by a state or states in self-defense, as defined by Article 51. The second permits certain military interventions when authorized by the Security Council under Chapter VII of the Charter. Until the United States has been attacked or the Security Council acts, Article 51 and Chapter VII do not give a green light to US strikes or other military campaigns.

There is one additional although controversial exception to the general prohibition against military force, and that is a so-called humanitarian intervention, or a military campaign calculated to stop widespread attacks on a civilian population, including acts of genocide, other crimes against humanity, and war crimes. The norm of humanitarian intervention is contested in part because it is not defined in the UN Charter, although many scholars and activists would claim it is supported by the Charter’s central objective to defend human rights and fundamental freedoms. Its more contemporary iteration, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), was championed by UN member states at the 2005 World Summit. While invoked by the Security Council and General Assembly in subsequent resolutions, R2P is an emerging standard that has yet to be codified in treaty form.

As defined by Secretary General Ban Ki-moon in 2009, R2P starts with life-saving humanitarian relief for the threatened population, and only contemplates military force as a last resort. R2P is fundamentally a call for non-lethal forms of assistance, including rescue, safe passage, shelter, medicine, food and clean water for war-affected individuals and populations. It impoverishes R2P to define it exclusively in military terms, and yet in common parlance R2P is code for armed intervention.

Both humanitarian intervention and R2P remain controversial because of the historical tendency for military interventions motivated by the protection of civilians to result in further and protracted suffering by civilians. Without the backing of the Security Council, humanitarian intervention is a potential rationale for military strikes by the United States in Syria. But R2P is a very thin reed on which to base a short-term military campaign by the US in response to the killing of Syrian civilians by chemical gas attack. This is so for one important reason. A militarized humanitarian intervention must be calculated to protect the civilian population that is being victimized. It can only be justified if it is both motivated to stop attacks on the civilian population and likely in practical terms to have that effect. A military intervention that raises the level of civilian risk violates R2P.

R2P is not a form of punishment or a rhetorical device. It does not sanction military retaliation against a state for attacking its own civilians, nor does it justify violence as a symbolic gesture for expressing solidarity with that oppressed population. If the United States launches “punitive,” “surgical,” or “symbolic” military strikes in Syria and we stop while the civilian population remains at risk, our responsibility to protect will be unmet. But if a US military campaign results in greater suffering by the civilian population we will have engaged in an inhumane intervention. In order to fulfill the United States’ Responsibility to Protect in Syria, we must commit ourselves to non-lethal and life-saving forms of humanitarian assistance for the Syrian people.

Jennifer Moore is on the faculty of the University of New Mexico School of Law. She is the author of Humanitarian Law in Action within Africa (Oxford University Press 2012).

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: UNITED NATIONS – PREAMBLE TO THE CHARTER OF THE UNITED NATIONS. Office for Emergency Management. Office of War Information. Domestic Operations Branch. Bureau of Special Services. 1941 – 1945. US National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Punitive military strikes on Syria risk an inhumane intervention appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesJust who are humanitarian workers?Gender politics and the United Nations Security CouncilThe Arms Trade Treaty: a major achievement

Related StoriesJust who are humanitarian workers?Gender politics and the United Nations Security CouncilThe Arms Trade Treaty: a major achievement

The poetry of Federico García Lorca

By D. Gareth Walters

It is apt that Spain’s best-known poet, Federico García Lorca, should have been born in Andalusia. Castile may claim to be the heart and the source of Spain, both historically and linguistically, but in broad cultural terms Andalusia has become for many non-Spaniards the very embodiment of Spain. Lorca’s poetry abundantly reflects this perception. His work is imbued with the Andalusian ‘deep song’ (cante jondo), more ancient in origin than the gypsies who were its performers. Among his poems are pieces that have the authentic flamboyance and violence of image of the native art. Yet for all the showiness, there is unfailingly a sense of rigour. Lorca’s abilities as a musician, allied to an almost scholarly interest in the songs and culture of Andalusia, led to a profound understanding of the poetic potential of the region. Above all, his poetry evokes rather than describes. His realizations of landscapes and experiences are elemental, not naturalistic; he reaches to the roots of objects and feelings.

In the light of such an apparently instinctive and intuitive understanding it might be believed that Lorca was a born poet, someone for whom the task of writing poetry would be second nature. Poetry, however, was a second vocation. Lorca was primarily a gifted musician: a talented pianist and an accomplished composer. Only when his musical ambitions were thwarted — partly by parental opposition, partly by the death of his teacher — did he embark on a career in literature. Between the ages of eighteen and twenty he wrote thousands of lines of verse, much of it of mediocre quality. (Although this poetry has now been published Lorca himself wisely never wished to do so.) This was a necessary apprenticeship: a means of purging himself of the merely derivative, of what comes across as second-hand emotion. In particular, he emerged from the process with a leaner, sharper style that characterises much of his poetry of the 1920s: Suites, Poem of the Cante Jondo, Songs, and Gypsy Ballads.

Bust of Federico García Lorca in Santoña, Cantabria

Lorca’s poetry has invariably stimulated ingenious, sometimes preposterous, interpretations. These have been provoked on the one hand by the linguistic substance which is both elusive and vivid as a result of the wealth of imagery. There is, too, the matter of Lorca’s homosexuality, often used by lazy commentators as a crude instrument of deconstruction. By contrast, emotions and experiences are variously concealed and transformed rather than directly expressed. Even in his final work, the incomplete collection of sonnets, the franker portrayal of homosexual love is far from confessional. Indeed, the poetry of the last years is often prompted by external circumstances rather than a purely lyrical impulse: the desire to evoke the exotic world of Moorish Andalusia (The Tamarit Divan), the result of a visit to Galicia (Six Galician Poems), and, most memorably, the reaction to the death of a bullfighter friend (Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías).Lorca did not travel widely outside Spain; indeed, for many years he divided his life between the family home in Granada and the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid, an informal college where he got to know Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel. His visit to America in 1929-30 was therefore exceptional. The fruit of his stay was Poet in New York, a surrealist-tinged collection of poems where an angry denunciation of the modern metropolis is combined with an anguished sense of identity. It is all too easy to read the poems in terms of a culture shock: the naïve Andalusian adrift in a great city. Yet, the sophistication and the rhetoric of its indignation suggest that this is Lorca’s most international work, one that sits alongside the dystopian visions of the city and the masses that were common in Anglo-American writers in that period.

Lorca’s achievement is multi-dimensional in its nature. If he has become the most representative poet of Spain it is just, because he epitomises a sense of a history of Spanish poetry — both its popular and learned components. His uncanny sense of rhythm makes the most familiar forms, notably the ballad, appear new, endowed with a protean, sinewy quality. Such compositions thus seem timeless, which is why his poetry could never become dated.

D. Gareth Walters has held chairs at the universities of Glasgow, Exeter, and Swansea. He is the author of numerous studies on Spanish literature including Canciones and the Early Poetry of Lorca: A Study in Critical Methodology and Poetic Maturity and The Cambridge Introduction to Spanish Poetry: Spain and Spanish America. He also edited the Oxford World’s Classics parallel text edition of Lorca’s Selected Poems.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bust of Federico García Lorca in Santoña, Cantabria. By Pere Joan Barceló [Public Domain]. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The poetry of Federico García Lorca appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 questions for Wayne Koestenbaum10 questions for David GilbertWalter Scott’s anachronisms

Related Stories10 questions for Wayne Koestenbaum10 questions for David GilbertWalter Scott’s anachronisms

September 1, 2013

Can supervisors control international banks like JP Morgan?

The dramatic failure of Lehman Brothers in 2008 has raised the question whether national supervisors are able to effectively control international banks. The London Whale, the notorious nickname for the illegal trading in the London office of JP Morgan, questions the effectiveness of international supervision.

The global financial crisis has brought into sharp focus the massive costs associated with the bail out of global systemic banks, which were perceived as too-big-to-fail. The governments’ handling of the financial crisis has reinforced too-big-to-fail doctrine. As a result, the most significant regulatory reform proposals have focused on the question of how to curtail the too-big-to-fail problem. Namely how can one reduce moral hazard and rein back expectations of future bail-outs of systemic banks?

The reform agenda has two priorities: first, reducing the probability of a systemic failure with substantially higher capital standards; second, reducing the impact of a systemic failure with resolution plans. These resolution plans should allow systemically important banks to fail or, at least, to be unwound in an orderly manner without imposing disproportionate costs on the taxpayer. On top of these reforms, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has prepared a list of 28 global systemic banks. The capital requirements and resolution plans are even more stringent for these global banks. JP Morgan is also on this ‘hit’ list.

But is this sufficient? I think not. National supervisors follow a narrow domestic interpretation of their mandate. US supervisors focus mainly on the US operations, UK supervisors on the UK operations, etc. They pay lip-service to international coordination, but when the going is getting tough, like in the crisis, they take a domestic approach responding to political demands from the Treasury and Congress. It is no surprise that major shortfalls happen in the overseas operations, such as the hidden trading in London at JP Morgan and the questionable practice of booking repos at net value to improve the balance sheet in the London office of Lehman.

Then why is international cooperation not on the reform agenda? Politicians and supervisors find it difficult to give up national powers. But that is exactly what is needed. As international banks operate on a global scale, their supervisors should also join forces and work on a common mandate. The endgame of resolution sets the incentives for supervision. The proposals start with a burden sharing agreement among national governments to rescue international banks, if needed. In the day-to-day supervision, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) can take a leading role and aid to oversee the global systemic banks on a consolidated basis replacing the fragmented approach by the national supervisors. Of course, the national supervisors will still contribute to the work of the BIS. This approach would make the global financial system a safer place.

Dirk Schoenmaker is dean of the Duisenberg school of finance at Amsterdam and author of Governance of International Banking: The Financial Trilemma published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Glass globe over stock data on computer screen. © scyther5 via iStockphoto.

The post Can supervisors control international banks like JP Morgan? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesEight years laterThe dawn of a new era in American energyHow can a human being ‘disappear’?

Related StoriesEight years laterThe dawn of a new era in American energyHow can a human being ‘disappear’?

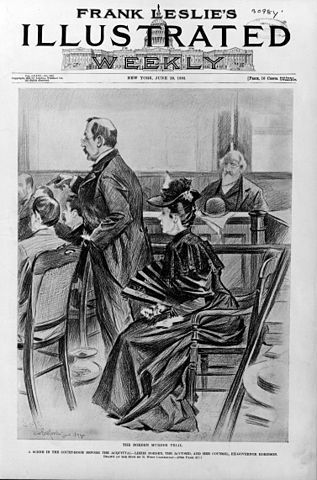

Parricide in perspective

It hardly seems like 24 years since Jose and Kitty Menendez were shot to death on 20 August 1989 by their two sons, Lyle and Eric. It was a crime that shocked the nation because the family seemed “postcard perfect” to many observers. Jose was an immigrant from Cuba who worked hard and became a multi-millionaire. He married Kitty, a young attractive woman he met in college, who was also hardworking. They were the parents of two handsome sons.

When their sons were arrested for the murders, the public wanted to know why two young men who had so much going for them would gun down the very people who had given them life and privilege. The prosecution argued that these men committed the crime to get their parents’ inheritance, valued at 14 million dollars. The defense argued that the boys had been physically, sexually, psychologically, and verbally abused by their parents for years and killed because they were in fear of their lives.

The first trial for Lyle and for Eric ended in a mistrial with jurors divided over whether the defendants were guilty of premeditated murder or not guilty by reason of self-defense. In a second trial, the defendants were convicted of two counts of first degree murder, as well as conspiracy to commit murder. The jurors found two special circumstances applied that could make them eligible for the death penalty: lying in wait and multiple murders. The jurors, however, recommended life in prison; the judge imposed a sentence of life in prison without parole.

The killing of parents, often referred to as parricide (which technically means the killing of a close relative), has fascinated the public for thousands of years. It is a recurrent theme in mythology and literature, as evident in the stories of Orestes, Oedipus, Alcmaeon, King Arthur, and Hamlet. Lizzie Borden, the 32-year-old daughter charged with killing her parents in 1892, remains notorious more than 100 years after the double murder occurred. The poem “Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother forty whacks, and when she saw what she had done, she gave her father forty-one” has immortalized her for generations.

The killing of parents, often referred to as parricide (which technically means the killing of a close relative), has fascinated the public for thousands of years. It is a recurrent theme in mythology and literature, as evident in the stories of Orestes, Oedipus, Alcmaeon, King Arthur, and Hamlet. Lizzie Borden, the 32-year-old daughter charged with killing her parents in 1892, remains notorious more than 100 years after the double murder occurred. The poem “Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother forty whacks, and when she saw what she had done, she gave her father forty-one” has immortalized her for generations.

As I write, two cases in New Mexico are making world news. One involves the case of a boy who at age 10 allegedly killed his father; in the other, a 15-year-old boy allegedly killed his father, mother, and three younger siblings. Fortunately, despite the attention that these cases receive, extensive analyses of more than 30 years of murder arrests in the United States provide no evidence that parricide is increasing. The two boys in New Mexico, the Menendez brothers, and Lizzie Borden, although headline grabbers, are in fact quite anomalous.

Here are some basic facts about the offspring killing their parents:

Parricides are rare events. They comprise about 2-5% of all homicides in the United States and in other countries where this phenomenon has been studied.

Most parents in the United States who are slain by their children are killed in single victim incidents by an offspring acting alone.

Most offspring who kill parents are adults. Less than 25% of “children” who kill their parents are under age 18.

Incidents with multiple offenders, such as the Menendez brothers, are very atypical events. Fewer than 10% of parricide victims are killed by offspring acting with one or more accomplices.

Double parricides involving mothers and fathers and other parental killings involving multiple victims such as familicides (killing of three or more family members) are also exceedingly uncommon, constituting about 8% of all parents killed by their offspring on the average in the United States every year.

Female parricide offenders such as Lizzie Borden are exceedingly rare. More than 80% of parricide offenders involved in single victim or multiple victim murders are males.

Parricides, among the most disturbing of crimes, are also among the most preventable of homicides. There are often warning signs that precede the killings. Such risk factors or circumstances include the severely abused, the severely mentally ill, the dangerously antisocial, and the enraged parricide offender. Homicidal thoughts and threats are not uncommon among these four types of parricide offenders and should always be taken seriously.

Kathleen M. Heide, PhD, is Professor of Criminology at the University of South Florida. Her lastest book, Understanding Parricide: When Sons and Daughters Kill Parents, was published in December 2012 by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Borden murder trial—A scene in the court-room before the acquittal – Lizzie Borden, the accused, and her counsel, Ex-Governor Robinson. Illustration in Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper, v. 76 (1893 June 29), p. 411. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

The post Parricide in perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesClosing the opportunity gap requires an early startCops and Robbers ReduxCross-border suspicions and law enforcement at US-Mexico border

Related StoriesClosing the opportunity gap requires an early startCops and Robbers ReduxCross-border suspicions and law enforcement at US-Mexico border

August 31, 2013

Bowersock and OUP from 1965 to 2013

Earlier this year, Oxford University Press (OUP) published The Throne of Adulis by G.W. Bowersock as part of Oxford’s Emblems of Antiquity Series, commissioned by editor Stefan Vranka from our New York office. It was especially thrilling that Professor Bowersock agreed to write a volume as it represents a homecoming of sorts for the noted classics scholar, who began his publishing career with OUP in 1965 with the monograph Augustus and the Greek World. In the video and slideshow below, we present reflections on changes in scholarly publishing through Professor Bowersock’s unique experience.

G.W. Bowersock on publishing in 1965:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Augustus and the Greek World (1965) and The Throne of Adulis (2013)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photos by Jonathan Kroberger.

Augustus and the Greek World (1965)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photos by Jonathan Kroberger.

Augustus and the Greek World (1965)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photos by Jonathan Kroberger.

Augustus and the Greek World (1965)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photos by Jonathan Kroberger.

Editor Stefan Vranka and author G.W. Bowersock

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photos by Jonathan Kroberger.

The Throne of Adulis (2013) and Augustus and the Greek World (1965)

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Photos by Jonathan Kroberger.

G. W. Bowersock is Professor Emeritus of Ancient History at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey. His many books include The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, From Gibbon to Auden: Essays on the Classical Tradition, Mosaics as History: The Near East from Late Antiquity to Islam, and Roman Arabia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Bowersock and OUP from 1965 to 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhat were the Red Sea Wars?Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the March on WashingtonThe ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum

Related StoriesWhat were the Red Sea Wars?Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the March on WashingtonThe ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum

The dawn of a new era in American energy

From global climate change to “fracking,” energy-related issues have comprised a source of heated debate for American policymakers. Needless to say, assessing the economic and environmental consequences of certain developmental shifts is often fraught with difficulty, particularly when considering existing national and international frameworks. Michael Levi, author of The Power Surge: Energy, Opportunity, and the Battle for America’s Future, provides insight into a new era of energy policy and renewable technologies in a field undergoing radical transformations.

On America’s “clean energy race” with China:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the global climate change debate and its impact on policy:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the driving forces behind renewable energy development:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the disputed environmental consequences of “fracking”:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Michael A. Levi is the Council on Foreign Relations’ David M. Rubenstein Senior Fellow for Energy and the Environment, and Director of the Program on Energy Security and Climate Change. He is author of The Power Surge: Energy, Opportunity, and the Battle for America’s Future.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The dawn of a new era in American energy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe two-state solution and the Obama administration: elusive or illusive?Why is the relationship between the US and Mexico strained?Closing the opportunity gap requires an early start

Related StoriesThe two-state solution and the Obama administration: elusive or illusive?Why is the relationship between the US and Mexico strained?Closing the opportunity gap requires an early start

August 30, 2013

Fall cleaning with OHR

The Oral History Review staff returns triumphant! A bit tanner, a bit wiser, and ready for another round of exploration into the theory and practice of oral history. We’ve already started arranging interviews, reviews, and commentary for the fall and look forward to engaging with you all once more. But before any of that, a few announcements:

To add to our nearly excessive number of social media accounts (OUPblog, Twitter, Facebook, Google +), we’re now on Tumblr and Soundcloud! If you run or know of any oral history projects on these platforms that we should follow, let us know!

Since we last blogged, the Oral History Association has put out more information about its upcoming annual meeting (9-13 October 2013, Oklahoma City). The program schedule and extended description of all the keynotes, plenaries, and special presentations are available at the conference’s homepage. You can also go there to register. Easy cheesy.

For those OHR subscribers who have mastered online access, a number of book and media reviews from Volume 40, Issue 2 are available now. For those who haven’t mastered online access, here’s a helpful tutorial. For those who haven’t subscribed to the OHR, here’s a friendly reminder of how to join.

We will resume our bi-weekly posting schedule on the 13th of September by introducing you all to David J. Caruso, manager of the Oral History program at the Chemical Heritage Foundation and our new Book Reviews Editor. Until then, drop a comment below, tweet, Facebook message, or send a carrier pigeon to UW-Madison with your latest news. We’ve missed you so.

Caitlin Tyler-Richards is the editorial/media assistant at the Oral History Review. When not sharing profound witticisms at @OralHistReview, Caitlin pursues a PhD in African History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her research revolves around the intersection of West African history, literature and identity construction, as well as a fledgling interest in digital humanities. Before coming to Madison, Caitlin worked for the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown University.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, or follow the latest OUPblog posts to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to only Oral History Review articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Fall cleaning with OHR appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOral history in disaster zonesHow to survive election season, oral history styleOHR signing off (temporarily!)

Related StoriesOral history in disaster zonesHow to survive election season, oral history styleOHR signing off (temporarily!)

Closing the opportunity gap requires an early start

Rarely is anything as highly valued yet poorly managed as the creation of education policy in the United States. Year after year, and lawmaker after lawmaker, evidence has been ignored in favor of a hunch, an ideology, or the latest quick-fix scheme. If heeded, that evidence would have led lawmakers toward enhancing children’s opportunities to learn. Parents know this, of course; when we have the means we provide enriched opportunities for our children. We know that when opportunities are denied, children will learn less.

The achievement gaps that we as a nation have been (rightfully) agonizing about for many decades are nothing more than the inevitable consequence of opportunity gaps. Yet, while the nation’s education policy has been conspicuously out of balance, we can’t seem to regain our equilibrium. Doggedly, we’ve persisted with our excessive focus on measuring outcomes and demanding improvement. So, for more than two decades, even predating the No Child Left Behind law, education policy and school improvement efforts have given short shrift to capacity-building and to resources.

Policies arising out of the so-called school accountability movement have instead used student testing to identify achievement gaps and to create strong incentives to improve test scores. Regrettably, these policies have not yet led to the next step. They have not turned to well-established research evidence that explains how achievement gaps arise and how they can be closed. If we expect to make any real progress, we need to balance the measurement of outcomes with a strong attention to inputs.

The overall opportunity gap is the result of a compilation—the cumulative effect of many separate obstacles. Make no mistake: the cumulative opportunity is shocking and terrible. So while we know, for instance, that high-quality preschool is important, a child denied that opportunity will faces an even larger opportunity gap if she is also without good health and dental care, if her parents have no stable employment, and if their housing situation is unsure and transient. Her opportunity gap would grow even more if her school has inexperienced and poorly trained teachers who themselves are unlikely to remain at the school for long, if the intervention required for low test scores at her school hinges on “turnaround” approaches that result in even more churn, and if the school also faces overcrowding and has serious maintenance issues.

And the gap would continue to grow if technology and learning materials at her school are spotty and outdated, if educators and others do not understand her family’s cultural or linguistic background and assume that these are deficits that cannot be built upon, if her neighborhood is not safe and if it has few enrichment opportunities after school or over the summer. Imagine as well that she’s shunted into dead-end, low track classes that evidence what former President Bush called a “soft bigotry of low expectations.”

The list, sadly, could go on and on. Responsible policy makers cannot avoid the reality that closing the achievement gap means seriously addressing these multiple obstacles. The answers point to the need to adopt, sustain, and support the sorts of enriching best practices that we already find in many schools serving advantaged communities.

It is here, though, that we must face a troubling truth: the genuine answers are not attractive to lawmakers—particularly those lawmakers angling for votes in the next election. A magic elixir, whether bottled as test-based accountability or market-based school choice, has been the preferred policy option. From the perspective of a politician, the smart and safe path is not long-term investment. It’s short-term appeals to exciting concepts like innovation or ‘tough’ concepts like accountability. As Upton Sinclair pointed out, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his livelihood depends upon his not understanding it.”

Interestingly and importantly, we now have a test case in front of us. President Obama, who has in many ways failed to address opportunity gap issues, did in his February State of the Union address set forth the goal of making “high-quality preschool available to every single child in America.” He proposes a tobacco tax to fund the federal initiative. High-quality preschool has a huge long-term payoff. Support for children’s development in the first five years can set them on a more successful trajectory for a lifetime. A recent meta-analysis of the research on effects of preschool programs in the United States since 1960 finds large initial effects as well as persistent effects on a broad range of outcomes.

As President Obama said in his State of the Union address, “Study after study shows that the sooner a child begins learning, the better he or she does down the road.” His proposal amounts to a small but important step in the right direction. But as a policy proposal, it’s also the miner’s canary, the fate of which will tell us as a society whether we’re willing to make the efforts needed to close the nation’s opportunity gaps. When will we take the actions needed to heed the evidence and restore balance to our education policy?

Kevin G. Welner is Professor of Education at the University of Colorado Boulder. He is the co-editor of Closing the Opportunity Gap: What America Must Do to Give Every Child an Even Chance.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only education articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Preschoolers learning to play the recorder. © CEFutcher via iStockphoto.

The post Closing the opportunity gap requires an early start appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCops and Robbers ReduxThe two-state solution and the Obama administration: elusive or illusive?Preparing for APSA 2013

Related StoriesCops and Robbers ReduxThe two-state solution and the Obama administration: elusive or illusive?Preparing for APSA 2013

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers