Oxford University Press's Blog, page 905

September 8, 2013

National Grandparents Day Tribute

Oxford University Press would like to take a moment to honor all grandparents, great-grandparents, and beyond, acknowledging the often extraordinary efforts (more are primary caregivers than ever before in history!) required to build and sustain a family. The information and statistics below have been drawn from numerous articles on the significance of grandparents in the Encyclopedia of Social Work online.

At the turn of the 20th century, only 6% of 10-year-olds had all four grandparents alive, compared with 41% in 2000 (Bengtson, Putney, & Wakeman, 2004). Accordingly, more adults are grandparents and, increasingly, great-grandparents, although they have proportionately fewer grandchildren than preceding generations.

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) with his granddaughter in Yasnaya Polyana.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Among parents aged 90 and older, 90% are grandparents and nearly 50% are great-grandparents, with some women experiencing grandmotherhood for more than 40 years. This is because the transition to grandparenthood typically occurs in middle age, not old age, with about 50% of all grandparents younger than 60 years. As a result, there is wide diversity among grandparents, who vary in age from their late 30s to over 100 years old, with grandchildren ranging from newborns to retirees.

Queen Henriette Marie with her daughter, granddaughter and son in law from the Family of Louis XIV. Painting by Jean Nocret (1615-1672).

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

While managing conditions related to their own aging process, many older adults assume caregiving responsibilities. In fact, about half of all individuals aged 55–64 spend an average of 580 hours per year caring for family members (Johnson & Schaner, 2005a).

Großmutter mit drei Enkelkindern, signiert Waldmüller - Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793-1835).

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Grandparents may have primary responsibility for raising grandchildren. About 2.5 million grandparents have responsibility for raising one or more grandchildren within the same household (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). Additionally, over 40% of grandparents in a custodial role are over 60 years of age (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

“The First Steps”. Georgios Jakobides (1853-1932).

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Most grandparents derive satisfaction from their role and interaction with grandchildren (Reitzes & Mutran, 2004; Uhlenberg, 2004).

The Naughty Grandson by Georgios Jakobides (1853-1932).

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

With over 2.4 million custodial grandparents providing primary care, skipped-generation households—the absence of the parent generation—are currently the fastest growing type. Among the challenges are reductions in free time, limitations on housing options, increased demands on resources, and even situations where the retiree needs to return to work to support this new family situation.

Old food seller and his granddaughter Varanasi Benares India.

Photo by Jorge Royan. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

Grandparent caregivers have been called the “silent saviors” of the family.

Mohov Mihail (1819-1903). Grandmother and granddaughter.

Public domain via Wikipedia Commons.

As a result of longer life expectancy, many of today’s families are multigenerational. Parents and children now share five or six decades of life, siblings may share eight or nine decades of life, and the grandparent–grandchild bond may last three or four decades.

As Bengston notes, longer years of shared living may offer a multigenerational kinship network to provide family continuity and stability across time as well as instrumental and emotional support in times of need.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, Delano grandparents, uncles, and cousins in Newburgh, New York. Photo provided by Franklin D. Roosevelt Library (NLFDR), National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Georgia Mierswa is a marketing associate at Oxford University Press. She began working at OUP in September 2011.

The Encyclopedia of Social Work is the first continuously updated online collaboration between the National Association of Social Workers (NASW Press) and Oxford University Press (OUP). Building off the classic reference work, a valuable tool for social workers for over 85 years, the online resource of the same name offers the reliability of print with the accessibility of a digital platform. Over 400 overview articles, on key topics ranging from international issues to ethical standards, offer students, scholars, and practitioners a trusted foundation for a lifetime of work and research, with new articles and revisions to existing articles added regularly.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social work articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post National Grandparents Day Tribute appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCops and Robbers ReduxThe thylacineBuddhism or buddhisms: mirrored reflections

Related StoriesCops and Robbers ReduxThe thylacineBuddhism or buddhisms: mirrored reflections

Understanding the history of chemical elements

After years of lagging behind physics and biology in the popularity stakes, the science of chemistry is staging a big come back, at least in one particular area. Information about the elements and the periodic table has mushroomed in popular culture. Children, movie stars, and countless others upload videos to YouTube of reciting and singing their way through lists of all the elements. Artists and advertisers have latched onto the iconic beauty of the periodic table with its elegant one hundred and eighteen rectangles containing one or two letters to denote each of the elements. T-shirts are constantly devised to spell out some snappy message using just the symbols for elements. If some words cannot quite be spelled out in this way designers just go ahead and invent new element symbols.

Moreover, the academic study of the periodic table has been undergoing a resurgence. In 2012 an International Conference, only the third one on this subject, was held in the historic city of Cuzco in Peru. Recent years have seen many new books and articles on the elements and the periodic table.

Exactly 100 years ago, in 1913, an English physicist, Henry Moseley discovered that the identity of each element was best captured by its atomic number or number of protons. Whereas the older approach had been to arrange the elements in order of increasing atomic weights, the use of Moseley’s atomic number revealed for the first time just how many elements were still missing from the old periodic table. It turned out to be precisely seven of them. Moseley’s discovery also provided a clear-cut method for identifying these missing elements through their spectra produced when any particular element is bombarded with X-ray radiation.

But even though the scientists knew which elements were missing and how to identify them, there were no shortage of priority disputes, claims, and counter-claims, some of which still persist to this day. In 1923 a Hungarian and a Dutchman working in the Niels Bohr Institute for Theoretical Physics discovered hafnium and named it after hafnia, the Latin name for the city of Copenhagen where the Institute is located. The real story, however, lies in the priority dispute that erupted initially between a French chemist Georges Urbain who claimed to have discovered this element, which he named celtium, as far back as 1911 and the team working in Copenhagen. With all the excesses of overt nationalism the British and French press supported the French claim because post-wartime sentiments persisted. The French press claimed, “Sa pue le boche” (It stinks of the Hun). The British press in slightly more restrained though no less chauvinistic terms announced that,

“We adhere to the original word celtium given to it by Urbain as a representative of the great French nation which was loyal to us throughout the war. We do not accept the name which was given it by the Danes who only pocketed the spoils of war.”

The irony was that Denmark had been neutral during the war but was presumably considered guilty by geographical proximity to Germany. Furthermore the French claim turned out to be spurious and the men from Copenhagen won the day and gained the right to name the new element after the city of its discovery.

Why are there so often priority debates in science? Generally speaking scientists have little to gain financially from their scientific discoveries. The one thing that is left to them is their ego and their claim to priority for which they will fight to the last. Another possibility is that women first discovered three or possibly four of the seven elements left to be discovered between the old boundaries of the periodic table (when it was still thought that there were just 92 elements). The three who definitely did discover elements were Lise Meitner, Ida Noddack, and Marguerite Perey from Austria, Germany, and France respectively. This is one of several areas in science where women have excelled, others being observational astronomy, research in radioactivity, and X-ray crystallography to name just a few.

One hundred years after the race began, these human stories spanning the two world wars continue to fascinate and provide new insight in the history of science.

Eric Scerri is a leading philosopher of science specializing in the history and philosophy of the periodic table. He is also the founder and editor in chief of the international journal Foundations of Chemistry and has been a full-time lecturer at UCLA for the past fourteen years where he regularly teaches classes of 350 chemistry students as well as classes in history and philosophy of science. He is the author of A Tale of Seven Elements, The Periodic Table: A Very Short Introduction, and The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image by GreatPatton, released under terms of the GNU FDL in July 2003, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Understanding the history of chemical elements appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHenry Moseley and a tale of seven elementsDid you know that we’re all made of stars?The thylacine

Related StoriesHenry Moseley and a tale of seven elementsDid you know that we’re all made of stars?The thylacine

September 7, 2013

What about Henry Hudson?

Henry Hudson envisioned that he would be the first explorer to find the elusive western passage through North America to the Orient. He persisted in this westward looking vision although his financier, the Dutch East India Company, insisted that he search eastward through the ice-bound sea north of Russia. Hudson had previously tried this northeastern route as well as a northerly route directly over the North Pole. Both had failed due to impassable ice.

On 25 March 1609, Hudson, an Englishman under contract with the Dutch, set sail in the Halve Maen (Half Moon). The Dutch specified that he should not attempt a west route even if the eastern route proved impossible, but Hudson had no interest in another failure. Therefore it is not surprising that he soon found a good reason to end this effort, using the weather as the excuse. As he sailed along the west coast of Norway, the ship encountered severe storms with gale force winds, but examination of the logs also shows much fair weather, raising some doubt that weather actually forced him back. Rather than return to Amsterdam as instructed, Hudson turned west and later anchored in a bay on the coast of Nova Scotia.

On the third of September Hudson sighted an opening to a bay, which appeared to be the mouth of a large river. The next morning they entered what came to be known as New York Bay and dropped anchor. Soon “people of the country” came to the ship carrying trade goods and seemed glad to see the Europeans. They traded green tobacco, deer skins, and maize for knives and beads. He reported that the native people wore skins of foxes and other animals, and were “very civil.” Hudson also noted that the people had copper tobacco pipes, and he inferred that copper naturally existed in the area. Over the next two days other trading sessions took place. Hudson recorded the Indian name for a large island in the river as Manna-Hata.

On the sixth of September five crewmen were determining water depths by boat when they were attacked by natives in two canoes, and one of the crewmen, John Colman, was killed by an arrow in the neck. When Indians came again with their trade goods, the ship’s crew captured two of them briefly, but set one free while the other jumped overboard. No more trading took place under these tense conditions.

Henry Hudson’s Half Moon sailing ship. Artist unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hudson weighed anchor on 13 September 1609 and began his exploration up the great river that still bears his name. He hoped this river might be a connection to the Orient. As the Halve Maen sailed up the river, Hudson wrote in his log, “It is as pleasant a land as one need tread upon; very abundant in all kinds of timber suitable for ship building and for making large casks or vats.” Sixty miles up the river they reported seeing many salmon. “Our boat went out and caught a great many very good fish.” Indians came to the ship and traded corn, pumpkins, and tobacco for what Hudson considered mere trifles, not knowing that the Indians saw these “trifles” as valuable for commerce among themselves.

On the twenty-second of September they found the river too shallow to continue farther upstream, and in the vicinity of present day Albany they turned the ship for a return to the sea. The ship’s log ends during the return crossing with a puzzling gap from the fifth of October to the seventh of November, when the Halve Maen docked in Dartmouth, England. There Hudson was detained by the Crown to prevent him from sailing again for the Dutch. After months of delay the Dutch portion of the crew continued to Amsterdam.

Henry Hudson failed in his quest for a passage through North America, as did many others. This third voyage, however, succeeded by claiming much of present day New York and parts of surrounding states for the Dutch, who began to settle the areas around New York Bay. The Dutch managed to hold their claim until 1674 when the land was ceded to the British.

Why did Hudson stop in England rather than Holland? There is no clear answer; perhaps he was avoiding repercussions for blatantly disregarding instructions, or perhaps the English component of the crew forced him to stop in England. The gap in the log might have shed light on this question. There are several known instances of dissent and mutiny among Hudson’s crews over his four voyages, the last one leading to his abandonment and disappearance with eight others on the shore of Hudson Bay in June 1611. Hudson’s greatest weakness was a leadership style that provoked his crews to mutiny, and in the end this weakness defeated his ambition for exploration.

Roger M. McCoy is Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Utah. His books include On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coast and Ending in Ice: The Revolutionary Idea and Tragic Expedition of Alfred Wegener.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post What about Henry Hudson? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesUndocumented immigrants in 17th century AmericaThe Reign of TerrorContemporary victims of creative suffering

Related StoriesUndocumented immigrants in 17th century AmericaThe Reign of TerrorContemporary victims of creative suffering

The thylacine

On the 7th of September each year, Australia observes National Threatened Species Day, so we thought this would be a good time to look at a species we couldn’t save. The following is an extract from the Encyclopedia of Mammals on the extinct thylacine (or Tasmanian tiger).

Up to the time of its extinction, the thylacine was the largest of recent marsupial carnivores. Fossil thylacines are widely scattered in Australia and New Guinea, but the living animal was confined in historical times to Tasmania.

Superficially, the thylacine resembled a dog. It stood about 60cm (24in) high at the shoulders, head–body length averaged 80cm (31.5in), and weight 15–35kg (33–77lb). The head was doglike with a short neck, and the body sloped away from the shoulders. The legs were also short, as in large dasyurids. The features that clearly distinguished the thylacine from dogs were a long (50cm/20in), stiff tail, which was thick at the base, and a coat pattern of black or brown stripes on a sandy yellow ground across the back.

Most of the information available on the behavior of the thylacine is either anecdotal or has been obtained from old film. It ran with diagonally opposing limbs moving alternately, could sit upright on its hindlimbs and tail rather like a kangaroo, and could leap 2–3m (6.5–10ft) with great agility. Thylacines appear to have hunted alone, and before Europeans settled in Tasmania they probably fed upon wallabies, possums, bandicoots, rodents, and birds. It is suggested that they caught prey by stealth rather than by chase.

At the time of European settlement, the thylacine appears to have been widespread in Tasmania, and was particularly common where settled areas adjoined dense forest. It was thought to rest during the day on hilly terrain in dense forest, emerging at night to feed in grassland and woodland.

From the early days of European settlement, the thylacine developed a reputation for killing sheep. As early as 1830, bounties were offered for killing thylacines, and the consequent destruction led to fears for the species’survival as early as 1850. Even so, the Tasmanian government introduced its own bounty scheme in 1888, and over the next 21 years, before the last bounty was paid, 2,268 animals were officially killed. The number of bounties paid had declined sharply by the end of this period, and it is thought that epidemic disease combined with hunting to bring about the thylacine’s final disappearance.

The last thylacine to be captured was taken in western Tasmania in 1933; it died in Hobart zoo in 1936. Since then the island has been searched thoroughly on a number of occasions, and even though occasional sightings continue to be reported to this day, the most recent survey concluded that there has been no positive evidence of thylacines since that time. In 1999, the Australian Museum in Sydney decided to explore the possibility of cloning a thylacine, using DNA from a pup preserved in alcohol in 1866, although it admitted that to do so successfully would require substantial advances in biogenetic techniques.

Adapted from the entry on the ‘Large Marsupial Carnivores’ in The Encyclopedia of Mammals edited by David MacDonald, which is available online as part of Oxford Reference. Copyright © Brown Bear Books 2013. David MacDonald is Founder and Director of Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only articles about earth and life sciences on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: a 19th century print of a Thylacine Wolf from Australia. William Home Lizars. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The thylacine appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 facts about Galileo GalileiTen facts about toastsTo medical students: the doctors of the future

Related Stories10 facts about Galileo GalileiTen facts about toastsTo medical students: the doctors of the future

September 6, 2013

Keith Moon thirty-five years on

When Harry Nilsson took a call on 7 September 1978 to tell him that the Who’s drummer Keith Moon had been found dead in Nilsson’s London apartment, it was a shock for two reasons. Firstly, Moon was the second star to die in the flat, the first having been Mama Cass, who had also borrowed it as a temporary London home. Secondly, after years of carousing together, it was impossible to believe that Moon’s iron constitution had finally succumbed to a lifetime of drink, drugs, and general excess. He had seemed indestructible, recovering from collapses on stage, gargantuan hangovers, accidental overdoses, and a myriad of events that would be stressful and difficult for anyone else — from fisticuffs to motor accidents.

Nilsson had met Moon as part of a circle of hard-drinking London friends, including Marc Bolan, Graham Chapman (of Monty Python), and Nilsson’s long-term buddy Ringo Starr. They would meet in mid-afternoon, drink brandy for six or seven hours, and then make their way to Tramp, the exclusive nightclub for more brandy and excitement. Their friendship blossomed during the making of Nilsson’s “Pussy Cats” album in Los Angeles, where as well as contributing some percussion tracks to the album (produced by John Lennon during his “lost weekend”) Moon was a fellow tenant of a beach house in Santa Monica. Lennon, Starr, Nilsson, bassist Klaus Voormann, and various of the other musicians moved in there with the idea of developing musical ideas by day and recording late into the night. What actually happened was days spent recovering from nights on the town, a round of drink and drugs in the afternoon, and then sporadic action in the studio at night. Nilsson’s voice deteriorated, and had to be re-recorded later in New York, but the partying continued unabated until Lennon called a halt to the sessions, realising the album was getting nowhere fast.

Keith Moon on drums. The WHO, MLG, Toronto, 21 October 1976. photo by Jean-Luc. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

However, from then on Moon and Nilsson were inseparable, whenever their respective musical schedules brought then to the same town at the same time. They often stayed together at Nilsson’s Curzon Place apartment, trying their hands at cooking (“everything came out a sort of grey mess,” Nilsson recalled) and even on one occasion attempting a weekend of sobriety. There were adventures on the Isle of Wight when Starr was filming “That’ll Be the Day” — Moon arrived, in style, by landing a helicopter on the roof of the hotel where the cast was staying. There were more attempts at recording together, and there were endless parties, including one at which Moon punched a hole in the wall of a London hotel while giving actor Peter Sellers a lesson in unconventional methods of opening bottles of booze.

The musical empathy between Nilsson and Moon is best seen in action in the somewhat bizarre musical sequences from Starr’s movie “Son of Dracula”. Although the band is miming on screen, Nilsson in full vampire costume as “Count Downe” pounds the piano and sings, as Moon thrashes away at the drums. The glances between them show them enjoying a sense of being fellow conspirators in musical mayhem, ably assisted on screen by Peter Frampton on guitar and Klaus Voormann on bass. Mostly, of course, Moon will be remembered for his highly individual drumming with the Who, but his moments on record and on screen with Nilsson are particularly poignant, given the unexpected nature of his death exactly 35 years ago today.

Alyn Shipton is the award-winning author of many books on music including Nilsson: The Life of a Singer-Songwriter, A New History of Jazz, Groovin’ High: the Life of Dizzy Gillespie, and Hi-De-Ho: The Life of Cab Calloway. He is jazz critic for The Times in London and has presented jazz programs on BBC radio since 1989. He is also an accomplished double bassist and has played with many traditional and mainstream jazz bands.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Keith Moon thirty-five years on appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe lark ascends for the Last NightThe Reign of TerrorInterpreting Chopin on piano - Enclosure

Related StoriesThe lark ascends for the Last NightThe Reign of TerrorInterpreting Chopin on piano - Enclosure

Reinvention of hybrid business enterprises for social good

On 1 August 2013, Delaware became the nineteenth state in the United States to adopt a version of a benefit corporation statute, which is designed to expand the range of legitimate purposes undertaken by business firms to include the interests of employees, environmental sustainability, and other nontraditional social goals beyond the traditional objective of profit-making for owners and investors. The event is noteworthy and perhaps a watershed moment in business history because Delaware sets the compass for US corporate law. More than half of publicly traded companies in the United States are incorporated in Delaware, and approximately two-thirds of the Fortune 500 are Delaware corporations. The adoption of the statute was also accompanied by a record number of immediate re-incorporations, including the well-known home goods retailer Method Products (supported by venture capital from European-based Ecover and San Francisco’s Equity Partners). More than a dozen other companies became Delaware benefit corporations as well.

Delaware joins an increasing number of US states which previously adopted versions of benefit corporation statutes, including the commercially important states of California (where clothes retailer Patagonia became the first registrant), Illinois, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. The United Kingdom adopted a similar corporate option in the form of the Community Interest Company, which was first authorized by national statute in 2004. Other countries around the world have also adopted legal variations of “hybrid” business forms that straddle the boundary between “for-profit” and “nonprofit” organizations. Delaware’s embrace, however, signals that this movement may have historical staying power.

As one who teaches in a prominent business school, I perceive a potential generational change in among students who are highly committed to business careers, but who are disillusioned by the narrow financial focus of “maximizing shareholder value” at all costs. These students are motivated by values that extend beyond the scope of augmenting their own personal wealth and advancing their own self-interests. The excesses of Wall Street that caused the worst global financial meltdown since the Great Depression have helped to fuel the disillusionment of this next generation of business leaders. I find heartening examples of Wharton students and those from many other business schools who are pursuing careers in which they are seeking to be a “part of the solution” to global problems, as well as finding opportunities to make a good living for themselves. The legal recognition of new business forms that allow for hybrid combinations of profit-making and social purpose suggest that idealistic pioneers – such as Ben & Jerry’s and Patagonia – may have begun to find traction in terms of changing the “rules of the game” and the basic assumptions of the motivating purposes of business enterprise, at least for a nontrivial part of the global economy.

The path for these new models of business will not be easy. Most probably, it will be difficult for many “hybrid” enterprises to contend with traditional competitors that continue to focus only on one “bottom line” of profitability. Legal recognition of new forms of “hybrid social enterprises,” however, may smooth the road for starting up these new business experiments. One might even imagine a gradual acceleration of business success if consumers begin to climb aboard (as they have done with other firms that have convincingly proclaimed “social good” as a part of their mission) and if new capital accumulation methods (such as the “crowdfunding” that has recently been approved for selective investors in the United States) begin to vie with traditional investment and financial markets.

In a world beset by increasingly worrisome problems of sustainability, economic inequality, and other major social issues, a shift of business models that may allow them to become stronger forces for social good will be most welcome. Delaware’s new statute may spark new research into how best to support and structure these new “hybrid social enterprises” in the future, and signal a new era in which the purpose of business enterprise is reconceived to include a broader and more diverse array of choices and missions than narrow financial theories have considered.

Eric W. Orts is the author of Business Persons: A Legal Theory of the Firm, which presents a foundational legal theory of business firms which is the first to embrace and explain the potential of benefit corporations and other “hybrid social enterprises.” Eric Orts is the Guardsmark Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He is also a Professor of Management, faculty director of the Initiative for Global Environmental Leadership, and faculty co-director the FINRA Institute at Wharton. He will be a visiting professor at INSEAD in France in the fall of 2013.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: group of young people at business school. © cokacoka via iStockphoto.

The post Reinvention of hybrid business enterprises for social good appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe trouble with LiborSpain and the UK: between a rock and a hard place over GibraltarSocial video – not the same, but not that different

Related StoriesThe trouble with LiborSpain and the UK: between a rock and a hard place over GibraltarSocial video – not the same, but not that different

To medical students: the doctors of the future

As a medical student, you are the future of health care. Despite the persistent negativity about the state of health care and the seemingly never-ending health care crisis, you have astutely perceived the benefits of becoming a physician. There is no doubt that health care delivery is unreasonably complex for everyone involved and, as much as political party loyalists insist that this is the fault of the ‘other’ party, the bureaucracy and inefficiencies have endured despite the back-and-forth changing hands of responsibility.

Fortunately, you have seen past the commotion and panic, and steadfastly remained optimistic. There is not a single medical student who ended up where he or she is by accident. The completion of rigorous undergraduate pre-medical prerequisite courses, outstanding grades, and top-notch MCAT scores required for application to medical school only come to those who have a well-thought-out plan, combined with a commitment and perseverance to become physicians. Medical school acceptance is exceedingly competitive, involving a multistep application process starting with preliminary applications, and then progressing to selective invitations for secondary applications and interviews. Academic excellence is the entry point, while interviews serve to distinguish young people who have a passion and a gift for helping humanity. Interviews are granted to few; offers of positions in a medical school class are even fewer.

You have already overcome all of these hurdles and remained focused. You are fortunate to begin your medical education at a time when you can shape the future of the profession. Medical education is becoming more innovative, going beyond traditional approaches to learning. The potential benefits for students are endless. With these advantages, come higher expectations. As a doctor of tomorrow, you will often expect yourself to improve the world around you for your patients.

You have already overcome all of these hurdles and remained focused. You are fortunate to begin your medical education at a time when you can shape the future of the profession. Medical education is becoming more innovative, going beyond traditional approaches to learning. The potential benefits for students are endless. With these advantages, come higher expectations. As a doctor of tomorrow, you will often expect yourself to improve the world around you for your patients.

The direction of health care will certainly improve as your generation of young physicians in training masters the knowledge and proficiencies necessary to become licensed MDs in a few years. The capabilities that will make you a leader are skills that cannot be measured, yet can absolutely be learned. Like many of today’s future doctors, you are likely to find yourself driven to improve the health care options available for patients or to use technology in new ways that have not been thought of before. There has been an increasing trend of physicians playing roles that have not been defined previously.

As a young physician, while you fulfill the requirements for licensing, you may discover that there is more than one way to be a doctor. Some of the ways to be a doctor involve non-clinical work, which typically does not enjoy a well-established path. If you choose to establish experience and find employment in alternative areas besides clinical practice, you will find that you don’t have built in access to guidance and direction. Yet, it is advantageous for you to understand all of the professional opportunities available to you while you embark on the road to becoming physicians. Knowledge is power. Every young doctor ought to appreciate the full array of options after graduation from medical school. This can help set the stage for career satisfaction in the long term. You can attain a career path that is challenging and fulfilling. The results for medicine as a profession will be enhanced when all doctors use their skills and talents in the way that fits best.

Heidi Moawad, MD is neurologist and author of Careers Beyond Clinical Medicine, an instructional book for doctors who are looking for jobs in non-clinical fields. Read her previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Multiracial medical students wearing lab coats studying in classroom. Photo by goldenKB, iStockphoto.

The post To medical students: the doctors of the future appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?How will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?Is your doctor’s behavior unethical or unprofessional?

Related StoriesWhy do women struggle to achieve work-life balance?How will a changing global landscape affect health care providers?Is your doctor’s behavior unethical or unprofessional?

Undocumented immigrants in 17th century America

“In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are under-written, the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc.

Having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our King and Country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine our selves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the eleventh of November in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Dom. 1620.”

When the Mayflower—packed with 102 English men, women, and children—set out from Plymouth, England, on 6 September 1610, little did these Pilgrims know that sixty-five days later they would find themselves not only some 3,000 miles from their planned point of disembarkation but also pressed to pen the above words as the governing document for their fledgling settlement, Plimouth Plantation. Signed by 41 of the 50 adult males, the “Mayflower Compact” represented the type of covenant this particular strain of puritans believed could change the world.

While they hoped to achieve success in the future, these signers were especially concerned with survival in the present. The lives of these Pilgrims for the two decades or so prior to the launching of the Mayflower had been characterized by Separatism. Their decision to separate from the Church of England as a way to protest and to purify what they saw as its shortcomings had led to the necessity of illegally emigrating from the country of England and seeking refuge in the Netherlands. A further separation was needed as these English families realized that the Netherlands offered neither the cultural nor economic opportunities they really desired. But returning to England was out of the question. Thus, in order to discover the religious freedom they desired, these Pilgrims needed to remove yet again, which became possible because of an agreement made with an English joint-stock company willing to pair “saints” and “strangers” in a colony in the American hemisphere.

Despite the fact that they were the ones who had recently arrived in North America, the Pilgrims taxed the abilities of both the land and its native peoples to sustain the newly arrived English. Such taxation became most visible at moments of violent conflict between colonists and Native Americans, as in 1623 when Pilgrims massacred a group of Indians living at Wessagussett. Following the attack, John Robinson, a Pilgrim pastor still in the Netherlands, wrote a letter to William Bradford, Plimouth’s governor, expressing his fears with the following words: “It is also a thing more glorious, in men’s eyes, than pleasing in God’s or convenient to Christians, to be a terrour to poor barbarous people. And indeed I am afraid lest, by these occasions, others should be drawn to affect a kind of ruffling course in the world.” As his letter makes clear, Robinson clearly hoped the colonists would offer the indigenous peoples of New England the prospect of redemption–spiritually and culturally–rather than the edge of a sword. The Wessagussett affair, however, illustrated such redemption had not been realized. From at least that moment on, relationships between English colonists and the indigenous peoples of North America more often than not followed ruffling courses.

While an established state church isn’t a main threat nearly 400 years later, some of the Pilgrims’ concerns still haunt many Americans. Like those English colonists preparing to set foot on North American soil, we remain afraid of those we perceive as different than us–culturally, racially, ethnically, and the like. But the tables are turned. We are now the ones striving to protect ourselves from a stream of illegal and “undocumented” immigrants attempting to pursue their dreams in a new land. Our primary method of protection? Separatism. Like the Pilgrims we often remain unwilling to welcome those we define as different. We’ll look to them for assistance when necessary, rely on their labor when convenient, take advantage of their needs when possible, but we won’t welcome them as neighbors and equals in any real sense nor do we seek to provide reconciliation and redemption to people eager to embrace the potential future they see among us.

Ruffled courses persist as the United States wrestles with how it ought to treat those men, women, and children who, like the Pilgrims of the seventeenth century, are looking for newfound opportunities. As we remember the voyage of the seventeenth-century immigrants who departed England on 6 September 1610 and recall their many successful efforts to establish a lasting settlement in a distant land, we do well to celebrate not only their need to separate but also their dedication to “covenant and combine [them]selves together into a civil body politic.” The world has enough ruffling courses and perhaps needs the purifying reform modeled by the Pilgrims and the potential redemption those like John Robinson hoped for as they agreed to work together for the common good. In short, one would hope that a people whose history was migration from another land would be more welcoming than we often are, especially in our dealings with the immigrants and the impending immigration reform of our own day.

Richard A. Bailey is Associate Professor of History at Canisius College. He is the author of Race and Redemption in Puritan New England. His current research focuses on western Massachusetts as an intersection of empires in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, fly fishing in colonial America, and the concept of friendship in the life and writings of Wendell Berry. You can find Richard on Twitter @richardabailey

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: The Mayflower Compact, 1620. Artist unknown, from Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Undocumented immigrants in 17th century America appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Reign of TerrorContemporary victims of creative sufferingWomen’s Equality Day

Related StoriesThe Reign of TerrorContemporary victims of creative sufferingWomen’s Equality Day

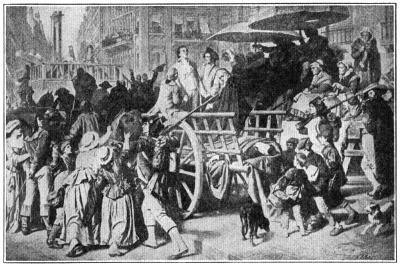

The Reign of Terror

By William Doyle

Two hundred and twenty years ago this week, 5 September 1793, saw the official beginning of the Terror in the French Revolution. Ever since that time, it is very largely what the French Revolution has been remembered for. When people think about it, they picture the guillotine in the middle of Paris, surrounded by baying mobs, ruthlessly chopping off the heads of the king, the queen, and innumerable aristocrats for months on end in the name of liberty, equality, and fraternity. It was social and political revenge in action. The gory drama of it has proved an irresistible background to writers of fiction, whether Charles Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities, or Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel novels, or many other depictions on stage and screen. It is probably more from these, rather than more sober historians, that the English-speaking idea of the French Revolution is derived.

Unquestionably the Terror was bloody. Over 16,000 people were officially condemned to death, as many again or more probably lost their lives in less official ways, and tens of thousands were imprisoned as suspects, many of them dying in prison rather than under the blade of the guillotine. But the French Revolution did not begin with Terror, and nobody planned it in advance. Robespierre, so often (and quite wrongly) regarded as its architect, was a vocal opponent of capital punishment when the Revolution began. But revolutions, simply because they aim to destroy what went before, create enemies. In France there were probably far more losers than winners, and not all of those who lost were prepared to accept their fate. So from the start there were growing numbers of counter-revolutionaries, dreaming of overturning the new order. How were they to be dealt with?

After three years of increasing polarisation, it was decided to force everybody to choose by launching a war. In war nobody can opt out: you are on our side or on theirs, and if you’re on theirs, you’re a traitor. If the war goes badly, it becomes increasingly tempting to blame it on treason, and to crack down on everybody suspected of it. By the first quarter of 1793, the war was going badly. The first proven traitor to suffer official punishment was the king himself, overthrown in August 1792 and executed the following January. After that the new republic found itself on the defensive against most of Europe. The measures it took to organise the war effort, including conscripting young men for the armies, provoked widespread rebellion throughout the country. By the summer huge stretches of the western countryside were out of control, and major cities of the south were denouncing the tyranny of Paris. When news came in early September that Toulon, the great Mediterranean naval base, had surrendered to the British, the populace of Paris mobbed the ruling Convention and forced it to declare Terror the order of the day. It seemed the only way to defeat the republic’s internal enemies.

Many of the instruments of Terror were already in place. A revolutionary tribunal had been established in March, and the guillotine had first been used a year earlier, designed as a reliable, fast, and humane way of executing criminals. Now they were systematically turned against rebels. Most victims of the Terror died in the provinces, after forces loyal to the Convention recaptured centres of resistance. This was mopping up a civil war. The vast majority of them were not aristocrats, but ordinary people caught up in conflicts that they could not avoid. Naturally, however, it was high profile victims who caught the eye, especially when, in the early summer of 1794, political justice was centralised in Paris. Often called the ‘great’ Terror, these last few months actually represented an attempt to bring the process under control. By then people were so sickened by the bloodshed (for unlike hanging, decapitation did shed a lot of blood) that the main site of execution was moved to the suburbs. The emergency was in fact over, and repression had done its work. The fortunes of war had also turned, and French armies were winning again. So everybody was looking for ways to end an episode of which the republic was becoming increasingly ashamed. Eventually a scapegoat was found, Robespierre, who had too often stood up to defend the increasingly indefensible.

Terror had built up slowly, and the proclamation of 5 September 1793 merely confirmed what was already happening. But it ended quite suddenly in July 1794, when it was possible to pin the blame shared by many on one incautiously vocal figure and a handful of his henchmen. But however ruthlessly, Terror had saved the republic from overthrow. Nor should we forget that other combatant states at the time resorted to repression of their own. In 1798, 30,000 people died in the great Irish rebellion, in a population only a sixth that of France. The British monarchy could be every bit as ruthless as the French republic, when it had to be.

William Doyle, Professor of History, University of Bristol and author of The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction and Aristocracy: A Very Short Introduction. Read Professor Doyle’s post on aristocracy here.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Very Short Introductions articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Execution of Marie Antoinette in 1793, [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons; (2) “Enemies of the people” headed for the guillotine during The Reign of Terror [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

The post The Reign of Terror appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe two-state solution and the Obama administration: elusive or illusive?Zeroing in on zero-hours workChallenges of the social life of language

Related StoriesThe two-state solution and the Obama administration: elusive or illusive?Zeroing in on zero-hours workChallenges of the social life of language

September 5, 2013

Spain and the UK: between a rock and a hard place over Gibraltar

The installation of a concrete reef by Gibraltar in disputed waters off the British territory, which is designed to encourage sea-life to flourish, was the final straw for Spain, which has long claimed sovereignty over the Rock at the southern tip of the country.

British diplomats say there is little room for doubt in international law that the waters are British, despite the Spanish government’s argument that they were not specifically referred to in the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht under which Spain ceded the territory to Britain.

As a result of the 72 concrete blocks dropped on the seabed, Madrid imposed extra border checks on the Spanish side that have caused lengthy traffic queues of up to several hours. Spain has similar reefs for environmental purposes in various areas of the Spanish coast.

The UK government in London says the checks are excessive and break EU free movement rules. The conservative Popular Party (PP) government of Mariano Rajoy insists they are needed to control smuggling, particularly of cigarettes. A European Union (EU) team is to monitor the border.

In a move that was reminiscent of the conflict over the Falklands in 1982 (another relic of the British Empire invaded by Argentina), the Royal Navy’s HMS Westminster docked in Gibraltar in the middle of August after a flotilla of Spanish fishing boats staged a protest about the reef.

In a reversal of the Spanish Armada, the Spanish fleet that sailed against England in 1588 and was defeated, other British warships joined HMS Westminster in what UK defence officials called a long-scheduled deployment in the Mediterranean and the Gulf. A British aircraft carrier, the Illustrious, sailed along the Spanish coast as part of the military training exercise.

Obviously, the two countries are not going to war. Spain, however, has threatened to join forces with Argentina and take the sovereignty issue to the United Nations, while the UK government might take the case of border controls to the European Court of Human Rights. In Spain, the spat is seen as a diversion from the country’s five-year recession and tough austerity measures, and the slush fund scandal in which the PP is embroiled.

The Rock of Gibraltar. Photo by Karyn Sig, 2006. Creative Commons License via Wikimedia Commons.

Unlike in the 16th century, Spain and the UK are allies and not sworn enemies today: both are members of NATO and of the EU. Some 12 million British tourists visit Spain every year, the largest country group, and two-way trade and direct investment is very strong.

The squabble comes at a time when Gibraltar is celebrating 300 years of British rule. The anniversary has been marked by a set of four Gibraltarian stamps, which bear the Union Jack, a portrait of Queen Elizabeth and the words from the Treaty “for ever, without any exception or impediment whatsoever” which Madrid regards as provocative.

While the previous Spanish government of the Socialist José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2004-2011) sought to ease the tone over the contentious issue of sovereignty by agreeing to set up with London a trilateral forum (Spain, the UK, and Gibraltar) to air grievances other than sovereignty, the PP killed this initiative by insisting on widening the forum to include local interests in the Campo de Gibraltar (the area in Spain close to the Rock). The UK and Gibraltar rejected this. Had the trilateral forum still existed, Gibraltar would probably have informed the Spanish government about the reef and the current situation might have been avoided.

The PP government hankers after a return to the 1984 Brussels Process, which established a bilateral negotiating framework with the UK for the discussion of all issues including sovereignty.

The trilateral forum was a modest step in winning the hearts and minds of Gibraltarians. The PP government’s heavy-handed response to the artificial reef, though it has legitimate concerns over other issues such as money laundering, has only served to harden Gibraltarian attitudes to Spain and remind them of previous crises, particularly the closing of the border in 1969 by General Franco, Spain’s dictator (1939-75). Last March, the US Department of State called the Rock “a major European centre of money laundering.”

The preamble to the Constitution declares that “her Majesty’s Government will never enter into arrangements under which the people of Gibraltar would pass under the sovereignty of another state against their freely and democratically expressed wishes.” In other words, Gibraltarians have the last word and it is highly unlikely they would ever vote to come under Spanish rule or even some kind of shared rule (the idea, as opposed to an actual agreement, was rejected in a 2002 referendum by 98.9% of votes, although it carried no legal weight). The residents of Hong Kong were not consulted when handed to China in 1997 when the New Territories’ lease ended; Gibraltar has a different status.

My wife and I suffered the consequences of the closure of the border, which was not re-opened until 1982. We were married in Gibraltar in 1974 because during the Franco regime Catholicism was the state religion and it was difficult for a Catholic (my wife) to marry a Protestant. Civil marriages did not exist in Spain. The only way to get to the Rock from Madrid, where we lived, was either by flying to London and then to Gibraltar or by train from the Spanish capital to the port of Algeciras and from there to Tangiers by boat and then in another ship to the British territory, an arduous journey and the route we took there and back.

We are hoping that by the time I appear at the Gibraltar Literary Festival at the end of October, it will not take hours to cross the border and common sense will have prevailed.

William Chislett, the author of Spain: What Everyone Needs to Know, is a journalist who has lived in Madrid since 1986. His book will be presented at the Cervantes Institute in London on 9 September, in Madrid on 24 September and at Gibraltar’s Literary Festival at the end of October. He covered Spain’s transition to democracy (1975-78) for The Times of London and was later the Mexico correspondent for the Financial Times (1978-84). He writes about Spain for the Elcano Royal Institute, which has published three books of his on the country, and he has a weekly column in the online newspaper El Imparcial.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Spain and the UK: between a rock and a hard place over Gibraltar appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy Parliament matters: waging war and restraining powerSpain’s unemployment conundrumThe trouble with Libor

Related StoriesWhy Parliament matters: waging war and restraining powerSpain’s unemployment conundrumThe trouble with Libor

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers