Oxford University Press's Blog, page 902

September 17, 2013

Codes and copyrights

There is nothing random about trademarks. Behind each trademark lies a well-considered move. Symbols are used to �create an analogical correspondence between two elements �and a concise form of expressing the essence or �meaning of a certain object or idea. Should we want to �deliver an idea that is to be adopted only by a certain �person or circle of people, then that idea may be �expressed in a coded manner. Organizations use symbology in trademarks to communicate subtle information, whether through words, ambigrams, religious symbols, or codes.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

According to The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown, we should look for encoded messages either in Leonardo's paintings or in words such as ‘sang real’ or ‘saint grail’.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The registered trademarks ‘SANGREAL’ and ‘SAINT GRAAL’ are both for alcoholic beverages.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

At a close scrutiny, the words 'earth', 'air', 'fire', and 'water' can be identified. This is called an ambigram. This image is registered as a trademark for the territory of Bulgaria.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Two further examples of trademarks containing ambigrams with word elements: SUN and SINS.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

(Left) An image of the mason symbols ‘trammel’ and ‘angle’ is registered as a Community trademark. (Right) The image of a rose and a cross is registered as a trademark under the Madrid Agreement for various countries.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

The above trademark contains well-known religious symbols. At a close scrutiny, one can see the 99 names of Allah of the Koran.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

This black-on-white pattern is called a QR (‘Quick Response’) code. The combination of the words ‘QR Code’ was registered as word Community trademark.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Our eyes or brain can scarcely distinguish among QR codes originating from different manufacturers.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Since 2011, these QR codes have been submitted as trademark requests: (1) TALKING LABEL, for a Community trademark registration, (2) ZNAP, for goods and services in Classes 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, and 41 ...

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

...(3) FREND, for services in Classes 36, 38 and 42, and (4) Wiki Presi, for goods and services in Classes 35, 38 and 42.

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

These QR code trademark applications were rejected for lack of distinctive character by the OHIM and the German Patent and Trade Mark Office respectively.

Binka Kirova and Ivan Penkin are the authors of “The code: the Da Vinci code, TM code, QR code …” in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law. Binka Kirova has worked in the Bulgarian Patent Office in the Department of Information and Trade Mark Search Services since 1998. She has published articles in the field of trademarks in the newspaper Money and in the Legal World magazine. Ivan Penkin has a master’s degree in Marketing and Business Economics from the University of National and World Economy (UNWE) Sofia, Bulgaria. Since 2009, he has been serving as an expert in the Patent Office of the Republic of Bulgaria in the Department of Formal and Substantial Examination of Trademarks and Geographical Indications.

The Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (JIPLP) is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to intellectual property law and practice. Published monthly, coverage includes the full range of substantive IP topics, practice-related matters such as litigation, enforcement, drafting and transactions, plus relevant aspects of related subjects such as competition and world trade law.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Codes and copyrights appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesHow can a human being ‘disappear’?Striking Syria when the real danger is IranThe rise and fall of Lehman Brothers

Related StoriesHow can a human being ‘disappear’?Striking Syria when the real danger is IranThe rise and fall of Lehman Brothers

Striking Syria when the real danger is Iran

As the world’s attention focuses on still-escalating tensions in Syria, Tehran marches complacently to nuclear weapons status, notably nonplussed and unhindered. When this long-looming strategic plateau is finally reached, most probably in the next two or three years, Israel and the United States will have lost any once-latent opportunities to act preemptively. Then, with an irrevocable atomic fait accompli on their hands, national leaders in Jerusalem and Washington will do whatever they still can to contain a new nuclear menace.

Once again, America has been focusing on the wrong national enemy. Yes, recent Syrian crimes against humanity are plainly egregious, and thus warrant prompt and suitable action. This obligation reflects a distinctly fundamental or “peremptory” rule of international law, one that has its roots in the Hebrew Bible and is reaffirmed in the binding Nuremberg principles of 1950: Nullum crimen sine poena (No crime without a punishment).

Indeed, in the absence of a UN Security Council that is ready and willing to inflict proportionate punishment upon Syria, the residual “Responsibility to Protect” falls upon certain remaining “great powers,” even if one of these states must act unilaterally. From the particular standpoint of the United States, this expectation is reinforced by Article 6 of the US Constitution (the “Supremacy Clause”), which incorporates all authoritative treaty obligations into the national law of the United States, and also by assorted US Supreme Court decisions, especially the Paquete Habana (1900), which brings customary international law into US municipal law. In the specific matter of Syrian Assad regime use of chemical weapons against Syrian noncombatants, the United States is bound by the Geneva Protocol (1925); the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling, and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction (1997); and relevant customary international law, which now binds all states, even those that are not recorded parties to any of the pertinent treaties or conventions.

But this hierarchy of obligation only describes the jurisprudential or legal background of the crisis with Syria. It does not directly consider the more-or-less equally meaningful strategic or geopolitical issues. Significantly, in this latter connection, Washington seems yet to realize that Damascus is effectively a mere proxy or surrogate of the core leadership in Tehran. Waging any military operations against Syria alone, therefore, would fail to blunt the power and animosity of America’s most truly primary enemy in the region.

What if this power and animosity should result in a fully-nuclear Iran? What would Washington do next? Inevitably, perhaps in concert with Jerusalem or even other US allies, the United States would then attempt to institute a durable and dependable system of regional nuclear deterrence.

Map of the Middle East from the CIA World Factbook. Public domain via cia.gov.

This possibly last-ditch security effort would likely be well-intentioned and indispensable. More precisely, in order to avoid a future of palpably measureless lamentations, Washington would then need to reconstruct certain earlier elements of “Mutual Assured Destruction.” MAD, of course, was the nuclear threat-based scheme that had successfully preserved a delicate superpower peace during the US-Soviet Cold War.

But this would not be your father’s Cold War. Could this more-or-less desperate final effort actually work? Could MAD, once again, produce genuine stability?

To be sure, it will seem odd to wax nostalgic about the original Cold War. In retrospect, that historic and protracted standoff between “two scorpions in a bottle” (Manhattan Project physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s famous metaphor) could seem relatively congenial and benign. During that time, essentially from 1949 to the end of the Soviet Union, two dominant national players had shared a conspicuously overriding commitment to stay “alive.” At that time, more than any other presumed obligation, both sides were prudentially disposed toward “coexistence.” Then, each side was predictably rational.

To work, any military system of deterrence must normally be premised on an assumption of rationality. This means that each side must believe the other will value its continued national survival more highly than any other preference, or combination of preferences. In the Cold War era, this proved to be an indisputably reasonable and correct assumption.

Now, however, things are different. Now, we have several good reasons to doubt that a nuclear-endowed government in Tehran could maintain, over time, the same stable and necessary hierarchy of national preferences.

It is certainly possible that the principal decision-makers in Tehran would turn out to be rational – perhaps even just as rational as were the Soviets. There is, however, no way of knowing this for sure.

This brings up an unavoidable query, easily the most sobering question of all. What if nuclear deterrence were to fail specifically between Iran and Israel? What, exactly, would happen, if Tehran were to launch a nuclear attack against Israel, whether as an atomic “bolt from the blue,” or as a result of deliberate or inadvertent escalation? Reasons could include (1) incorrect information used in its vital decisional calculations; (2) mechanical, electronic, or computer malfunctions; (3) unauthorized decisions to fire, in the national decisional command authority; or (4) coup d’état.

None of this strategic scenario would even need to be considered if Iran could still be kept distant from nuclear weapons. Barring the very unlikely prospect of an eleventh-hour preemption against Iranian hard targets, however, it will become necessary to implement a broadly stable program for regional nuclear deterrence. Within this historically familiar threat system, one that has determined international power-management logic from the seventeenth-century Peace of Westphalia (1648) to the present, Israel might still be able to identify certain remaining deterrence options.

Of necessity, these options would pertain to both rational and irrational decision-makers in Tehran. By definition, irrational adversaries do not value their own national survival most highly. Nonetheless, they could still maintain a determinable and potentially manipulable ordering of preferences. Washington and Jerusalem, therefore, should promptly undertake a meticulous effort (1) to adequately anticipate this prospective ordering; and (2) to fashion deterrent threats accordingly. Future preference orderings would not be created in a vacuum. Assorted strategic developments could impact such orderings and become manifest in the form of certain game-changing “synergies,” or in more narrowly military parlance, as significant “force multipliers.”

One last observation here is critical, and brings us full circle, back to Syria. The preference orderings of a steadily nuclearizing Iran will also be impacted, especially in the short term, by whatever happens in Damascus. If an American missile strike is launched against certain hard targets of the al-Assad regime, President Barack Obama, however unintentionally, may also be declaring a de facto war against Iran. In such circumstances, Washington’s jurisprudential motives would not include a wider conflict, but any more plainly generous motives could prove to be irrelevant. Here, Tehran would almost certainly choose to accelerate the pace of its nuclear weapons program. In part, this acceleration would represent the result of an increased fear of becoming the object of (an American and/or Israeli) preemptive attack itself.

In the longer-term, Iran’s cumulative response to any American attacks on Syrian regime targets could trigger a reduced willingness to abide by the indispensable deterrence logic of Mutual Assured Destruction. It follows that any such American attacks, especially if they did not remain expectedly “tailored” or “limited,” could hasten the outbreak of a more-or-less region-wide war involving nuclear arms. Once again, this is not to suggest that a suitably proportionate American military response to Syria’s domestic use of chemical weapons would be inherently law-violating or inappropriate (as indicated here earlier, quite the contrary), but only that there might also be various unintended, yet distinctly substantial, nuclear consequences.

To the extent that the Lebanon-based Shiite militia group, Hezbollah, might become the beneficiary of any Iran-developed nuclear weapons — Hezbollah, after all, is a closely allied proxy of both Syria and Iran — such atomic consequences could include expanding regional and worldwide risks of nuclear terrorism. None of these potentially threatening possibilities will have been lost upon Vladimir Putin, who might well decide, in Russia’s considered response, to reinvigorate certain elements of the original Cold War. Ironically, should this happen, the more complex and intersecting effects of multiple state and sub-state participants could rapidly undermine any previously-expected deterrence benefits of Mutual Assured Destruction.

For the United States, and for Israel, Syria is not the real problem. Iran is the real problem. To be sure, launching certain proportionate attacks against Assad-regime military targets could conceivably be lawful or even law-enforcing, but such consciously “limited” operations could also represent an unwitting invitation to wider war, and ultimately to an Iranian acceleration of nuclear weapons-related activities.

Louis René Beres was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971), and is Professor of International Law at Purdue. Born in Zurich, Switzerland, on August 31, 1945, he is the author of many major books and articles dealing with nuclear strategy and nuclear war. His most recent publication dealing with Syria, Israel, and the law of war, appears in the Harvard National Security Journal, Harvard Law School (August, 2013). Ten years earlier, in Israel, Professor Beres served as Chair of Project Daniel (2003). Professor Beres is a frequent contributor to OUPblog.

If you’re interested in Middle Eastern politics, The Oxford Handbook of Islam and Politics, edited by John L. Esposito and Emad El-Din Shahin provides a comprehensive analysis of what we know and where we are in the study of political Islam. It enables scholars, students, and policymakers to understand the interaction of Islam and politics and the multiple and diverse roles of Islamic movements, as well as issues of authoritarianism and democratization, religious extremism and terrorism regionally and globally.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Striking Syria when the real danger is Iran appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesIsrael’s survival in the midst of growing chaosThe case against striking SyriaMoveOn.org and military action in Syria

Related StoriesIsrael’s survival in the midst of growing chaosThe case against striking SyriaMoveOn.org and military action in Syria

Poetry of the Preamble

“We the people of the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia, do ordain, declare, and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.”

The United States Constitution, in its first full draft, began with those words. Would it have made a difference to us, today, if the Preamble announced itself as the voice of the people of existing states, rather than (as it does) of “the people of the United States”?

I’ve spent the last three years reading and rereading the Constitution’s text. While the Preamble is not legally the most significant part of the document, first impressions matter. On Constitution Day, it is worth pausing for a minute to pay tribute to the most famous—and legally least significant—words to come out of the Philadelphia Convention:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The phrase “We the People of the United States” is etched deep in the national consciousness — and it isn’t true. The Constitution wasn’t written by “the people.” The “people” took no part in the drafting; indeed, they were not even represented there. The convention had been called by the Congress, a body in which the states, not the people, were represented. The people had no notice that the meeting would write a new constitution in their name. The formal purpose of the meeting was to “propose amendments” to the existing constitution, the Articles of Confederation. When the Convention’s work was done, the delegates instructed “the people” to approve or disapprove. No changes; no amendments. Just a simple “yes” or “no.” Nonetheless, they presumed to speak in the voice of “the people.”

Why? Consider these words: “Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son, Achilles…” This sound like prayer. But in fact, just like “we the people,” they are a deceptive claim of authorship. It is not I, the poet, who brings you the tale of Achilles and Hector, but Calliope herself. In epic poetry, the poet speaks the Goddess’s words; in constitution-making, the drafters speak to us in our own voice.

So successful has the Preamble’s invocation been that the generations that came after came to believe that they gave birth to the Constitution, that it issued from, rather than being all but imposed upon, “the people.” The Preamble has been almost too successful, in fact.

What are the purposes of the Constitution as laid out in the Preamble? Most people cannot recite them by memory. They are: “to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.”

“Form, establish, insure, provide, promote, secure” : these are strong verbs that signify governmental power, not restraint. “We the people” are to be bound—into a stronger union. We will be protected against internal disorder—that is, against ourselves—and against foreign enemies. The “defence” to be provided is “common,” general, spread across the country. The Constitution will establish justice; it will promote the “general” welfare; it will secure our liberties. The new government, it would appear, is not the enemy of liberty but its chief agent and protector.

“Limited government” as an idea receives at best an incidental nod; the states are nowhere to be found. “Trade” and “commerce” are not mentioned. The document’s stated aims are wholly public, not private. “We the people” hope for justice, security, and liberty, not for wealth.

Another idea is strikingly absent. “All men are created equal,” the Declaration of Independence had said. The Preamble makes no such claim. Human equality as an explicit concept will not appear in the Constitution until 1868, eight decades after the Federal Convention.

Finally, “we the people … ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” The two words have different connotations. “Ordination” is sacerdotal; priests and rabbis enter into their sacred functions by way of ordination. To “ordain” a Constitution or a government is more than simply to set it up. “Establishment” referred to churches—more than half of the thirteen states had established churches, official links between God and the State supported by tax funds. The new Constitution is brought to us by a Muse, ordained by the authority of the People, and established at the center of our common life. We can read these words as creating a national religion, one at which we still worship.

In 1950, the poet Charles Olson defined a poem as “energy transferred from where the poet got it … by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader … a high-energy construct and, at all points, an energy-discharge.” Beyond invoking the Muse, beyond specifying a purpose, the Preamble crackles with that “energy-discharge.” In the beginning, the nation is without form and void. There is darkness; then someone speaks in our voice: Let there be law.

Garrett Epps is Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore Law School. A former staff writer for the Washington Post, he has written for the New York Times, New Republic, The New York Review of Books, and the Atlantic. He is the author of American Epic: Reading the U.S. Constitution. Two of his nonfiction books, Democracy Reborn and To An Unknown God, have been finalists for the American Bar Association’s Silver Gavel Award. One of his two novels, The Shad Treatment, won the Lillian Smith Book Award. He lives in Washington, DC.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Detail of Preamble to Constitution of the United States. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Poetry of the Preamble appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901The first tanks and the Battle of SommeWhy send a woman to Washington when you can get a man?

Related StoriesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901The first tanks and the Battle of SommeWhy send a woman to Washington when you can get a man?

Francesca Caccini, the composer

In my last post I wrote about little known composer Sophie Elisabeth. Today’s subject, Francesca Caccini, is somewhat better known. The last decade or so has seen a renewed interest in her work. Born in Florence, Italy on 18 September 1587, Caccini was a prolific composer who also sang and was proficient at the harp, harpsichord, lute, theorbo, and guitar.

She was the first woman to compose an opera, and was employed by the Medici family for a total of three decades, becoming at one point the highest-paid musician on their payroll. I highly recommend reading this summary of Caccini’s life and accomplishments written by Suzanne Cusick to get a fuller picture of the composer’s life. My favorite tidbit: Caccini’s colleague and biographer reports that at age 12 she wrote a commentary on books 3 and 4 of the Aeneid.

As is the case with Sophie Elisabeth, much of Francesca Caccini’s music is lost to us. Her style has been compared to Monteverdi and Jacopo Peri, whose L’Euridice is the earliest opera for which the complete score has survived, and in which Caccini performed at age 13. A generation older than she, these two composers participated in an exciting time of transition in musical style as the Renaissance drew to a close, and Caccini certainly took part in ushering in the Baroque style.

A few of her compositions do survive, however. Caccini wrote beautiful songs like “Nube Gentil”, preserved in a collection of her music called Il Primo Libro delle Musiche:

Click here to view the embedded video.

She also wrote dramatic works (now often referred to as operas) like La liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina (“The Liberation of Ruggiero from the Island of Alcina”):

Click here to view the embedded video.

First performed in Florence in 1625, La liberazione is the only one of Caccini’s operas to survive intact. The libretto is based on one of the many subplots of the epic poem Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, and its plot would have been well known at the time: Good sorceress Melissa is on a mission to free Ruggiero from bad sorceress Alcina, who has the warrior under her sexual spell (check out Cusick’s exploration of the opera’s gender-related subtext). Melissa succeeds in freeing Ruggiero by disguising herself as his African teacher, and Alcina ultimately rides off on a dragon in a rage. The premiere performance wrapped up with a ballet for 24 horses and riders.

Caccini was indeed a remarkable person, and worthy of more study than she has yet received. Though essentially a highly-paid servant for the Medicis, she won the respect and admiration of many powerful people throughout her lifetime. According to her first biographer, she was an extremely evocative performer with the ability to elicit any number of passions from her audience. I personally would love to see a biopic on her life. She apparently had a longstanding feud with a librettist, which at one point involved her publicly recounting many of his sexual exploits with the court singers — tell me that isn’t blockbusting fodder. Plus, Daniel Day-Lewis would make a good Claudio Monteverdi:

Copy of a portrait of Claudio Monteverdi by Bernardo Strozzi, hanging in the Gallerie dall’Accademia in Venice (1640). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Meghann Wilhoite is an Assistant Editor at Grove Music/Oxford Music Online, music blogger, and organist. Follow her on Twitter at @megwilhoite. Read her previous blog posts on Sibelius, the pipe organ, John Zorn, West Side Story, and other subjects.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Francesca Caccini, the composer appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCelebrating Women’s Equality DayLullaby for a royal babyThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

Related StoriesCelebrating Women’s Equality DayLullaby for a royal babyThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narration

September 16, 2013

Five tips for medical students

With the new medical school term about to start, lots of fresh-faced medical students are about to hit the wards for the first time. Finding the right balance between lectures, bookwork, and bedside experience is difficult and different for everyone. Some learn best in the library, others in theatre, and others by sticking like glue to a qualified doctor. Whatever works for you, there are a few tips that I can pass on, based on my own experiences, several years of teaching medical students, and listening to the grumbles of senior clinicians and teachers.

See at least one patient every day. Everyone will tell you this, and nobody ever does it. However, if you only take one tip away from this post, please let this be it. There is no substitute for experience and the more histories you take and patients you examine, the better you will get. If you see a patient, take their history, examine them, and then read their notes to find out what has happened since admission, what their diagnosis was, and what treatment was started. You then have something to focus your reading on and a face to remind you of that condition. Yes you need to read up on them all, but it’s easier to remember facts if they have human details attached to them.

Always see the patient before you read the notes. This is a tip for junior doctors as well as medical students. Many patients will have been labelled with a diagnosis but sometimes these diagnoses are incorrect, or preliminary, or evolving. Even if they are correct, learning to listen for a murmur, or test for whispering pectoriloquy is more important than getting the answer right. You hear what you expect to hear and see what you expect to see, but signs change. You may turn around to present your findings, confidently stating that the patient has a pleural rub, only to discover that the registrar you are presenting to knows that the pneumonia has been treated and the rub is no longer present. Rely on your own ears and eyes. You won’t always get the answer right and you will miss things, but admitting you can’t hear something means that the person teaching you can correct your technique or show you ways of making signs more prominent. Remember that even senior cardiologists request echocardiograms to confirm valve lesions.

Medical students studying. Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Project HPEQ. Photo: Nugroho Nurdikiawan Sunjoyo / World Bank. Creative Commons License via World Bank Photo Collection Flickr.

You learn most from experience. Following a junior doctor around, taking histories and examining the patients they direct you towards, or asking senior clinicians to teach you examination skills and correct your examination routine are the best ways of learning medicine. The clinicians you learn from have years of experience and try to keep up to date with their subject. Many will be delighted to pass knowledge on to enthusiastic students. In addition, every patient tells a unique story, you cannot put emotions onto paper, feel enlarged livers from a textbook, or understand how uncomfortable cannulas are from inserting them on a model arm. The caveat to this is this is…

Don’t rely entirely on experiential learning. Experience is the most valuable way of learning, but only when reading around the subject backs it up. Perhaps the consultant teaching you has a preference for a particular way of performing a procedure, that doesn’t mean there aren’t other methods. Perhaps the patient you are seeing has been given a less common drug: is this because they have allergies or failed first line treatment? Your medical school library should have books on all subjects, borrowing one on the area you are rotating through will help you back up your learning. In addition, there are many online resources that can help, but try to stick to reliable, evidence based sources rather than just Googling your subject. Check also whether the textbook you are reading has associated web-based content.

Attend lectures and give feedback to your lecturers. Yes, a 9 a.m. start is difficult to get out of bed for, sitting through an hour on the glomerulonephritides may feel like it confuses you more, not less, and you will end up with copious notes that make little sense afterwards. However, when you are starting work at 7:30 a.m. and your Consultant is asking the 27 causes of the symptoms you’ve just diagnosed in your patient, you’ll look back with longing. If only you’d listened and made notes. If only you’d got up in time. Your lecturers should be experts on the subject and should give you up to date and interesting information. If they don’t, or their style isn’t very engaging, give feedback. Things won’t change unless you tell your medical school that there is a problem. Be honest, but polite and constructive in your criticism. Remember there is nothing more disheartening than lecturing to a half-empty room of bored and sleeping students, so get involved, ask questions, and recall your lecturer got up far earlier than you did.

Hopefully these tips will help you to get the most out of your time at medical school. It should be a fun experience and one of the best periods of your life, but remember that at the end of it you’ll be expected to be a doctor. That’s a scary thought, so do what you can now to make sure you’ll be the best doctor you can be. Good luck!

Elizabeth Wallin is one of the authors of the ninth edition of the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine. She is a Specialist Registrar in Renal Medicine at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK. Oxford Medical Handbooks are also available online as part of Oxford Medicine Online.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five tips for medical students appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTo medical students: the doctors of the futureHeaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everydayThe first tanks and the Battle of Somme

Related StoriesTo medical students: the doctors of the futureHeaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everydayThe first tanks and the Battle of Somme

Heaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everyday

I was in the Jerwood Centre in Grasmere on Friday 30th August to see the Wordsworth Trust’s fascinating exhibition, “Dorothy Wordsworth: Wonders of the Everyday”. The sad news of Seamus Heaney’s death could not have reached me in a more appropriate spot, for the Nobel Laureate opened this Centre in 2005.

Heaney was a ‘Wordsworthian’ in the true sense of the word. His deep affinity with both William and Dorothy Wordsworth found expression in a reverence for ordinary objects, obscure lives. His poetry has repeatedly re-visited and drawn imaginative nourishment from the work this brother and sister produced collaboratively, at the height of their powers, in their beloved Westmorland. He shared their passionate belief that ‘men who do not wear fine clothes can feel deeply’, and took particular pleasure — as they did — in the domestic, the quotidian. Dove Cottage, the Wordsworths’ home for a decade, has proved for Heaney — as for many contemporary poets – a place of pilgrimage and inspiration. He made a BBC documentary on location in Grasmere in 1974. In several contexts he has reflected on things once owned by the Wordsworths, or places familiar to them. Occasionally his poems have even seemed to ‘inhabit’ Dove Cottage itself, as if finding there a kind of second home.

Dove Cottage

Heaney would undoubtedly have enjoyed the current exhibition at the Jerwood, which celebrates the life and writings of a woman who ‘knew what home was’ – who ‘put into words moons and clouds and poor people on the roads, plants of fell-side and garden…bread and pies, the silences of evening by the fire, poetry read, and those she loved sharing the comfort’. This is the first exhibition to concentrate on Dorothy Wordsworth in her own right – looking closely at her relationships with female friends, her journals, letters and poems, not just her role as William’s sister. There is an impressive range in the materials selected for display; and a marvellous catalogue-book written by the exhibition’s curator, Pamela Woof, from which I have just quoted.It wouldn’t do to rush a visit to this exhibition; one needs a whole morning to take everything in – manuscripts, contemporary paintings, books, personal possessions. Short excerpts from Dorothy’s journals are arranged high up on the walls, like ‘found’ imagist poems. There are recordings to be listened to: Pamela has made an excellent selection from the journals, and reads them with beautiful slow distinctness. Very movingly, there is also a free-standing monument at the centre of the room, on which appears a list of unnamed travellers who wandered through Grasmere during the war years — people whose lives Dorothy glimpsed very briefly, and captured in her Grasmere Journal. (In 2013, this Journal was added to the UK’s Memory of the World Register — along with Domesday Book, the Winston Churchill Archives, and other important documents.)

Pamela Woof confesses that she found it hard to keep William out of her exhibition; but she is to be congratulated on getting the balance exactly right. There’s nothing sensational in the way the Wordsworths’ intense relationship is handled here. Visitors are able to see, in Dorothy’s own handwriting, the famous journal entry in which she describes her feelings on the day of William’s marriage to Mary; and they can reach their own conclusions about why some of this description was later crossed out. There is, too, a welcome opportunity to listen to a long section of the 1802 Grasmere Journal in which Dorothy describes how she responded to her brother’s experience of ‘writer’s block’ — reading to him, accompanying him in walks and gardening, selecting the right passage from Shakespeare to get his creative juices flowing.

The exhibition deals very briefly — and tactfully — with Dorothy’s later years, which were blighted by arteriosclerosis and dementia. Severely limited in her access to the natural world, she sought comfort in writing, reading aloud, and copying her verses out in different versions. There was a therapeutic dimension both in creating and ‘performing’ poetry, which by all accounts she found uplifting.

Here is one of the poems Dorothy wrote from her sick room. Dated by her as 1836 (and copied out for the Wordsworths’ friend and neighbour Isabella Fenwick in 1839), it gives us some insight into her state of mind as she looked back on a crisis in 1832-3 when her life was in danger. Other versions of this poem can be found in her Commonplace Book: the last five stanzas are a re-working of ‘Floating Island at Hawkshead’; and a version of the first three stanzas is already known to scholars as a stand-alone poem addressed to her doctor. See what you think of this version — newly acquired by the Wordsworth Trust — which is published here for the first time. How smoothly does the poem flow, and do the eight stanzas make a unified whole?

Lines addressed to my kind friend & medical attendant, Thomas Carr

Five years of sickness & of pain

This weary frame has travelled oer

But God is good & once again

I rest upon a tranquil shore

I rest in quietness of mind,

Oh! may I thank my God

With heart that never shall forget

The perilous path I’ve trod!

They tell me of one fearful night

When thou, my faithful Friend,

Didst part from me in holy trust

That soon my earthly cares must end.

Harmonious Powers with Nature work

On sky, earth, river, lake & sea;

Sunshine & storm, whirlwind & breeze,

All in one duteous task agree.

Once did I see a slip of earth

Self-loosened from the grassy shore

Float with its crest of trees adorn’d

On which the warbling birds their pastime take

Food, shelter, safety there they find;

There berries ripen flowrets bloom;

There insects live their lives, & die

A peopled world it is – in size a tiny room.

Perchance when you are wandering forth

Upon some vacant sunny day

Without an object, hope, or fear,

Thither your eyes may turn – the Lake is passed away.

Buried beneath the glittering Lake

Its place no longer to be found;

But the lost fragments shall remain

To fertilize some other ground.

Published with kind permission of the Wordsworth Trust, from a transcript made by Jeff Cowton, Curator of the Wordsworth Collection. This manuscript was sold at the Roy Davids Collection sale at Bonhams, London, on 8 May 2013.

Lucy Newlyn is Professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University, and a Fellow of St Edmund Hall. She has published widely on English Romantic Literature, and her latest book is William and Dorothy Wordsworth: ‘All in Each Other’.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Dove Cottage. By Christine Hasman [CC-BY-SA-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons; (2) and (3) Images of the manuscript of ‘Lines addressed to my kind friend & medical attendant, Thomas Carr’ published with kind permission of the Wordsworth Trust. Do not reproduce without the express permission of the Wordsworth Trust.

The post Heaney, the Wordsworths, and wonders of the everyday appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe first tanks and the Battle of SommeEzra Pound and James Strachey BarnesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901

Related StoriesThe first tanks and the Battle of SommeEzra Pound and James Strachey BarnesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901

September 15, 2013

The first tanks and the Battle of Somme

“And there, between them, spewing death, unearthly monsters.” To a Bavarian infantry officer on the Somme in the early morning hours of 15 September 1916, the rhomboid, tracked behemoths lurching at him amidst waves of attacking enemy infantry had no name. The British called them “tanks,” but he could not know this; neither he nor any of his commanders had ever seen or heard of them. That morning other reports from nearby announced sightings of an “extraordinary vehicle” mistaken for an ambulance until machine gun fire burst from its side; of machines spewing smoke which the men mistook for poison gas; of prehistoric or futuristic creatures, uncertain in gait and obscure in purpose. Ten days later the puzzlement on the Somme, if anything, had spread. From the remains of an infantry regiment near the village of Thiepval came a description of an egg-shaped machine, “5 or 6 meters long,” mounted with machine guns on its side and shovels on its front to push the earth aside. How the thing propelled itself was unclear. And had it just disgorged the 40 men around it, or had they followed on foot? It was hard to say.

British Mark I Tank, 1916. Photograph by British Government Photographer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

For almost two years the British had been working fitfully on it. The idea was hardly novel. “I shall produce unassailable, covered chariots,” Leonardo da Vinci had written in 1482 to Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, “which will enter the enemy lines with their artillery and will break through any troop formations, however numerous they may be. The infantry will be able to follow, without losses or obstacle.” By the eve of the First World War inventors of various stripes and nationalities had come up with armored cars, guns on caterpillar tractors, and, at least on paper, notional machines, mobile steel boxes perhaps, that would overcome hostile fire or carry a human element safely through it. The corpses in South Africa and Manchuria, left by the recent Boer and Russo-Japanese wars, convinced anyone who still needed convincing that exposed infantry could neither withstand nor break through modern firepower. In the summer and autumn of 1914 the reciprocal carnage wrought by the machine gun in the Great War and the impregnable trenches, earthworks, and gun emplacements that soon defined the lines of the Western Front lent new urgency to the designers’ reveries. From early 1915 proposals in the British army for a “machine-gun destroyer” or “landcruiser” or “landship” — an armor-clad Dreadnought to ply the fields of Flanders — wound their way slowly through the bureaucracy, while a prototype emerged almost as painfully from elaborate simulations at Shoeburyness in Essex and on Lord Salisbury’s estate at Hatfield Park. They were designing a water carrier, the authorities let it be known for secrecy’s sake, and they tried naming their brainchild a “reservoir,” a “receptacle,” a “cistern,” until they settled on the most mundane cognomen of all: “tank”.

The new machines acquired their most important advocate early, in the controversial figure of Douglas Haig, Commander of the British Expeditionary Force. He had first learned of them from an early promoter, Winston Churchill, and by 1916 he yearned to put them to use in the summer allied offensive on the Somme. But they were not ready on 1 July, when the British left their trenches and took 60,000 casualties, the worst day in their military history. By the time they were, British and Dominion forces had suffered many more casualties and made only modest gains, and huddled under the first of the autumnal rains that would make the Somme terrain even more impassable than it already was. Haig was determined to break through, and deploy his new weapon — the Mark I tank, weighing about 28 tons, moving at no more than four miles an hour, and carrying guns or machine guns — while he still could.

He did not break through, and his new weapon scarcely made any difference to the outcome. Forty nine tanks were on hand that day, supposed to reach the German front lines on a six-mile front about five minutes ahead of the first infantry wave. Most broke down or ditched, many before they even reached the departure line. Of the 18 that participated effectively, some arrived alongside their infantry or even behind them. Others lost their way and fired on their own men. In time shellfire or even bullets striking fuel lines incinerated those still in action. When they did break through, they devastated enemy defenses, and in the village of Flers one of them drove up the main road, firing sideways, as cheering troops followed behind. Then they provoked some local panics, by the Germans’ own admission. But mostly they bogged down, like the attacks themselves, and set off nothing like the general panic that had swept through some French Territorial and Algerian divisions entrenched at Ypres the year before, when the Germans had sent cylinders with nearly 200 tons of chlorine their way and introduced chemical warfare to the Western front.

[image error]

An early model British Mark I “male” tank, named C-15, near Thiepval, 25 September 1916. The tank is probably in reserve for the Battle of Thiepval Ridge which began on 26 September. The tank is fitted with the wire “grenade shield” and steering tail, both features discarded in the next models. Photo by Ernest Brooks, from the UK Government. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

No one yet knew how to use tanks. Most of Haig’s immediate subordinates had not even heard of them until the month before. To coordinate these under-powered and unpredictable machines with artillery, infantry, and aircraft, over a fire-swept and obstacle-strewn terrain, required not so much imagination, still less pure theory, as experience. Haig’s critics — they now included Churchill — deplored the premature revelation of a secret weapon, the squandering of surprise. His defenders saw the inescapable ordeal of trial and error. “It was a very valuable try-out” one officer said. In a way he was right. His compatriots were learning. Their tanks again fared poorly at the third battle of Ypres in the summer of 1917. But in November that year, at Cambrai, after an artillery preparation that achieved total surprise, 360 massed Mark IV tanks penetrated German defenses to a depth of several miles, as infantry followed and squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps flew overheard. Properly used, tanks could indeed break through.

The setback on the Somme had allowed the success at Cambrai in other, more ironical ways. It had convinced the German High Command that the new tanks had no future, and induced a benighted sense of assurance that could only oblige their enemies. “Our infantry laughs about the tanks,” senior staff officers claimed, wrongly. By 1918 they too had grasped the potential of massed tanks. But it was too late. By the time of the armistice the Germans could field only 45 front-line tanks against the Allies’ 3,500.

During the 1920s and 1930s — all lingering doubts resolved — engineers, visionaries, and strategists promoted the tank as a weapon of destiny, whatever the kind of land war their countries had to fight. The new advocates of armored warfare envisioned a concentrated and offensive role for the latter-day knight, the new instrument of shock on the battlefield — Basil Liddell Hart and J.F.C. Fuller in Britain, Estienne d’Orves and Charles de Gaulle in France, Mikhail Tukhachevsky in the Soviet Union, and Heinz Guderian in Germany, who took Hitler to the Kummersdorf proving grounds south of Berlin in 1933 to observe tanks in motion. “There is what can help me!” the new Führer exclaimed. “There is what I need!”

It had been just 17 years since the Mark I tanks had foundered in the ditches and shell-craters of the Somme.

Paul Jankowski is Raymond Ginger Professor of History at Brandeis University. His many books include Verdun: The Longest Battle of the Great War, Stavinksy: A Confidence Man in the Republic of Virtue, and Shades of Indignation: Political Scandals in France, Past and Present.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The first tanks and the Battle of Somme appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901Ezra Pound and James Strachey BarnesWhy send a woman to Washington when you can get a man?

Related StoriesTheodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901Ezra Pound and James Strachey BarnesWhy send a woman to Washington when you can get a man?

The rise and fall of Lehman Brothers

This September marks the fifth anniversary of Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy. While US markets have posted a stronger than expected year, full recovery has been slow since the “too big to fail” 2008 financial crisis. Robert W. Kolb takes a look back at Lehman Brothers’ decline in the following excerpt from The Financial Crisis of Our Time.

There really were Lehman brothers, two German immigrants who settled in Alabama in the middle of the nineteenth century, got their start by running a general store, and moved into cotton trading. After the Civil War, they moved their business to New York, entered the financial advisory industry, and the firm joined the New York Stock Exchange in 1887. Active in the investment banking business since the late 1880s, Lehman went through a series of mergers and divestitures, both as an acquiring firm and as a target. For a while, it was part of American Express, but it went public in the mid-1990s and was an independent company until its demise in 2008.

Lehman focused much of its real estate securitization activity in commercial real estate and was widely admired for its strategy in that area. But Lehman was also a big player in residential real estate, carrying as much as $25 billion in residential mortgages of highly questionable value as the end neared. Like other players on Wall Street, Lehman used extremely high leverage to earn profits of $4 billion in 2006. Following the collapse of Bear, Lehman possessed all the information one can imagine about the seriousness of the problems it faced. By June 2008, the public too received the message, if they did not already have it: Lehman posted a quarterly loss of $2.8 billion. At a time when other firms were scrambling to unload assets and secure partners, Lehman’s CEO Richard Fuld still was insisting that Lehman can “go it alone.”

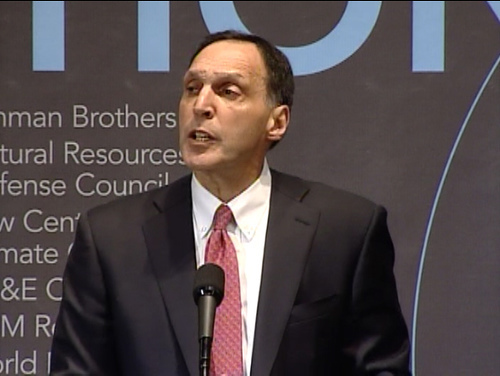

Richard S. Fuld, Jr at World Resources Institute forum, 2007.

As summer wore on and fall approached, the crisis deepened and Lehman’s prospects deteriorated. Despite Fuld’s proud go-it-alone stance, Lehman was seeking a merger partner in the summer and was scouring the Middle East and Asia for investment funds. Ironically, in hindsight, Lehman even tried to sell itself to AIG. In the summer, Lehman proposed to the Federal Reserve that Lehman could transform itself into a bank holding company subject to regulation by the Federal Reserve, a transformation that would allow Lehman to borrow from the Federal Reserve. However, the Fed rejected this plan. Later, Treasury Secretary Paulson explained this decision by saying that Lehman lacked good assets to deposit as collateral and that the federal government lacked the powers to offer Lehman support.

By September, matters were clearly worsening rapidly. Shortly after Labor Day, other Wall Street firms began to demand additional collateral for loans they had extended to Lehman. On September 9, the Korea Development Bank announced conclusively that it would not be investing in Lehman, and Lehman’s stock fell a further 37% on the news.

Realizing its desperate straits, Lehman intensified discussions with Barclays and Bank of America, seeking to be acquired. A key question in such matters turned on whether the Federal Reserve would offer guarantees to limit the potential losses of acquirers. Both Barclays and Bank of America were clearly looking for such a guarantee to make an acquisition palatable.

The Fed faced the following question: Is Lehman too big to fail, given current market conditions? After all, Lehman was bigger than Bear, and market conditions were worse in September than they had been in March, when the Fed put itself on the hook for $30 billion to get the Bear deal done. The Fed certainly had its hands full at the moment, that week of September 8–12, as Merrill Lynch, a much larger firm, was under simultaneous pressure. Also, the shares of Washington Mutual contributed to the stress by falling 30% that Wednesday and another 21% the next day, while AIG tottered on the brink of collapse. By September 11, a Thursday, Lehman’s survival depended on whether the Fed would guarantee some of its assets to help get a deal done, and Lehman was trying to limp to the weekend, when it would try to finalize a deal. The Wall Street Journal reported on September 12 that Lehman had experienced $10 billion in paper losses in 2008, had a market capitalization of $2.86 billion, and was holding a bonus pool of $3 billion, more than its entire market capitalization.

The weekend brought resolution, and it was not a victory. On Saturday night, the Fed refused to offer support for a Lehman deal, and Barclays and Bank of America abandoned their talks to acquire Lehman, proving that their pleas for Fed assistance were not mere bargaining ploys. Lehman had no alternatives remaining, and it filed for the largest bankruptcy in US history on September 15, 2008, ending its more than 150-year history.

The collapse of Lehman led almost immediately to bitter recriminations. Had the Fed and Treasury erred in not finding a way to save Lehman? Was the government trying to send a message of market discipline to show that some firms were not too big to fail? Could Lehman have done a better job for itself by acting more aggressively and wisely to restructure its miserable finances as the magnitude of the crisis developed? All these issues would attract much attention in time, but the market and public policy analysts had little leisure to reflect on these broader issues that were now of historical concern, for other larger shoes were already threatening to drop the same weekend.

Robert W. Kolb is Professor of Finance and Frank W. Considine Chair of Applied Ethics at Loyola University Chicago. He has been professor of finance at the University of Florida, Emory University, the University of Miami, and the University of Colorado, and has published more than 20 books, including The Financial Crisis of Our Time, Lessons from the Financial Crisis: Causes, Consequences, and Our Economic Future and Futures, Options, and Swaps.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Richard S. Fuld, Jr. January 2007 by the World Resources Institute Staff. Creative commons license via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The rise and fall of Lehman Brothers appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesCan supervisors control international banks like JP Morgan?On the Man Booker Prize 2013 shortlistFive important facts about the Irish economy

Related StoriesCan supervisors control international banks like JP Morgan?On the Man Booker Prize 2013 shortlistFive important facts about the Irish economy

September 14, 2013

James Fenimore Cooper: thoughts on a life

By John McWilliams

It is hard to conquer the contemporary prejudice that a “Classic” must be an old boring book written by a dead white male, but the prejudice must be faced down. To Herman Melville, Fenimore Cooper was “our national novelist.” To Walt Whitman, Cooper’s great hero Leatherstocking (alias Deerslayer, Pathfinder, Natty Bumppo) was “from everlasting to everlasting.” To Joseph Conrad, Cooper’s descriptions of the sea had a “sureness of effect that belong to a poetical conception alone.” And to D. H. Lawrence, Cooper’s descriptions of the forest and its contentious settlement in The Pioneers were “marvelously beautiful, some of the loveliest, most glamorous pictures in all literature.” Although we now appreciate pictorial description through visual media, and have become impatient of pictures in words, these four tributes by Cooper’s literary peers offer judgments that should remain widely shared.

The development of American fiction is inconceivable without Cooper’s achievement and influence. He published novels in almost every conceivable genre of fiction, on almost every subject important to his times, and achieved lasting influence in most of them. The Spy (1821), long regarded as the first American novel of lasting significance, was the first of five historical novels that rendered the American Revolution in complex, often self-divided patriotic terms. The five Leatherstocking Tales form a grand myth of the white settlement of the American continent at the admitted expense of both Native Americans and the environment. The image of the Indian in the Euro-American mind owes more to The Last of the Mohicans than to any other written text. For readers who can still entertain the possibility that heroism exists, there is no more engaging or convincing here in American fiction than Leatherstocking, troubled by the killings he necessarily commits, and forever opening paths for a commercial civilization he scorns. The tributes by Melville and Conrad attest to the power of Cooper’s seven sea novels, especially Cooper’s renderings of storm and sail in The Pilot, and of icy Arctic Seas (foreshadowing Melvillean whiteness) in The Sea Lions. Willa Cather’s novels of the Nebraska prairie, and Jack London’s novels of Alaskan and sea frontiers, gain great resonance by comparison and contrast to Cooper’s precedents.

Cooper’s daunting, lifelong energies led him to venture down still other fictional paths, nominally imaginary but rendered realistic through trenchant social commentary. He experimented with the unreliable first person narrative, the biography of an inanimate object, urban satire, the beast fable (The Monikins), and dystopian fiction (The Crater). His three-volume trilogy titled The Littlepage Manuscripts (Satanstoe, The Chainbearer, The Redskins) forms the first sustained family chronicle in American literature, a precursor of William Faulkner’s Snopes trilogy, and of John Cheever’s Wapshot novels. Cooper’s five European travel volumes implicitly challenge Washington Irving’s resort to nostalgia and sentimentality as Irving’s easy way to curry transatlantic approval. Cooper’s The American Democrat, as H.L. Mencken knew, remains a remarkably perceptive analysis of the merits and problems of New World republicanism, somewhat like Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, but one-sixth its length.

The last sentence of the first Leatherstocking tale, The Pioneers, pictures Leatherstocking retreating from the rapidly growing community of Templeton toward a west that is still inhabited almost entirely by Indians: “He [Leatherstocking] had gone far towards the setting sun—the foremost in that band of pioneers, who are opening the way for the march of the nation across the continent.” The identity here claimed for Leatherstocking is not unlike Cooper’s own: the foremost of American literary pioneers. Periodically, there are movements to denigrate Cooper by emphasizing the limitations he shares with many others of his era and by seeking to replace Cooper’s stature with rediscovered writers, often women or minorities. Such fictional rediscoveries can and should supplement Cooper’s achievement, but they have not displaced it. Cooper possessed–in spades–the merits of moral courage, broad historical knowledge, and the power of imagination. Ars Longa, Vita Brevis.

John McWilliams is College Professor of Humanities at Middlebury College, Vermont. He teaches courses in the Departments of Art History, History, Literary Studies and Religion. His most recent book is ‘New England’s Crises and Cultural Memory’. He edited and wrote the Introduction and Historical Essay in the Oxford’s World’s Classics edition of The Last of the Mohicans.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter, Facebook, or here on the OUPblog.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Portrait of James Fenimore Cooper by John Wesley Jarvis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post James Fenimore Cooper: thoughts on a life appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesOn the Man Booker Prize 2013 shortlistThe poetry of Federico García Lorca10 questions for David Gilbert

Related StoriesOn the Man Booker Prize 2013 shortlistThe poetry of Federico García Lorca10 questions for David Gilbert

Theodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901

Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States upon the death of William McKinley in the early morning of 14 September 1901. An assassin had fatally wounded McKinley eight days earlier. Vice President Roosevelt took the presidential oath at a friend’s home in Buffalo, New York, hurried to Washington for a brief Cabinet meeting, and then returned to the capital on 20 September 1901 to take over as chief executive. To the American people, he promised to continue “absolutely unbroken” the policies of William McKinley. He set the new tone for his administration in a private letter that he wrote to his closest friend, Henry Cabot Lodge, on 23 September 1901. “It is a dreadful thing to come into the presidency in this way; but it would be a far worse thing to be morbid about it.”

For the next seven and a half years, Roosevelt led the nation in a style that was anything but morbid and angst-ridden. Though Roosevelt grew fat in the White House and lost the sight of one eye, he reveled in the running of the nation. He told friends in those early days “I will be President” because, as he later said, “I have got such a bully pulpit.” Franklin D. Roosevelt later called his distant cousin “a preaching president.”

Orotone of Theodore Roosevelt as President in 1904. Photograph by Edward S. Curtis. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Roosevelt was the first chief executive to be a true celebrity and captivate the nation with his energy and charisma. As a reporter noted, when Roosevelt was present the public could “no more look the other way than a small boy can turn his head away from a circus parade followed by a steam calliope.” While Roosevelt was entertaining and fun as no president had been before or since, he was also a serious practitioner of presidential politics and policy.

During his two terms, the United States addressed issues of the conservation of natural resources as had not occurred previously in the nation’s history. He sought to establish the supremacy of the national government over private business interests and included organized labor in the settlement of such disputes as the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902. In the Hepburn Act of 1906 to regulate railroads, the Pure Food and Drug Act, and the Meat Inspection Act of the same year, he broadened the government’s power in the economy in ways that still remain controversial.

Roosevelt also used the power of the presidency to shape a world role for the United States. His acquisition of the Panama Canal in 1903-1904 remains controversial. He mediated an end to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 and sent the “Great White Fleet” of the United States Navy around the world in 1907-1908. He believed in both halves of his famous saying “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” While he used power, he did not send American troops into harm’s way in a reckless manner. In his 1913 autobiography, he recalled with pride: “We were at absolute peace” when he went out of office in March 1909.

Time took its toll on Roosevelt during his years in office, but he retained the same joy in being president that he displayed when he assumed power in September 1901. As his days lessened, he told a friend: “I have done my work, I am perfectly content; I have nothing to ask; and I am very grateful to the American people for what they have done for me.” In addition to being a strong president, Roosevelt had made his days in the White House an enjoyable period for the American people. He had reformed college football, jousted in print with political enemies, and saw his celebrity daughter Alice Roosevelt married in the White House. As his presidency drew to a close, he visited the home of his old friend, Henry Cabot Lodge. When the president was departing, Mrs. Lodge observed “The great and joyous days are over, we shall never have anything like them again-there is no one like Theodore.”

Nannie Lodge was right. Theodore Roosevelt was a unique figure in the American presidency. On the anniversary of his coming into the White House, it is good to remember what one historian called “the fun of him” and to recall the wise phrase of a reporter when Roosevelt died: “You had the hate the Colonel a whole lot to keep from loving him.”

Lewis L. Gould is Eugene C. Barker Centennial Professor Emeritus in American History at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include Theodore Roosevelt, The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, and The William Howard Taft Presidency.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Theodore Roosevelt becomes President, 14 September 1901 appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesWhy send a woman to Washington when you can get a man?Booksellers in revolutionBurlesque in New York: The writing of Gypsy Rose Lee

Related StoriesWhy send a woman to Washington when you can get a man?Booksellers in revolutionBurlesque in New York: The writing of Gypsy Rose Lee

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers