Oxford University Press's Blog, page 909

August 27, 2013

Contemporary victims of creative suffering

Like many teachers, I intend to treat the upcoming 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington as an occasion to revisit Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famed “I Have a Dream” speech. Many of my students will, I expect, be deeply affected by Dr. King’s ability to impart a timeless quality to the “fierce urgency of now” that he associated with the Civil Rights Movement.

When celebrating King’s enduring relevance, however, we often neglect the implications of his message for issues that remain no less urgent today. So this year I also plan to focus on perhaps the speech’s most intimate moment, when King paused to address those on the front lines of the freedom struggle. Noting how his fellow civil rights activists had been victimized in ways both vicious and shrewd, he referred to them as “veterans of creative suffering.”

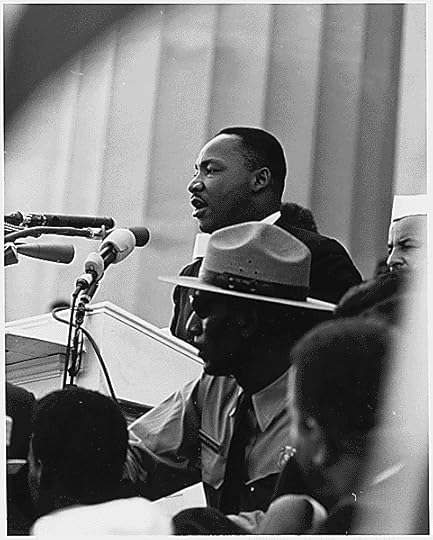

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaking at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 28 August 1963. Photo by Rowland Scherman via the National Archives.

That the sanctions of Jim Crow were borne so “creatively” was a tribute to the activists who met brutality with non-violent resistance, nullifying segregation’s moral standing and thus much of its power. But, as King understood well, segregationists worked creatively too, finding new ways to impose suffering on those who threatened their way of life. Considering the breadth, depth, and sophistication of the system that resisted civil rights advances allows us to appreciate the enormity of the Civil Rights Movement’s accomplishments as well as to recognize the ways in which those achievements remain under siege. Digging deep to comprehend the inner workings of civil rights opponents enables us, as we celebrate the promise and rewards of Dr. King’s dream, to also more clearly grasp the challenges associated with its fulfillment.

The hallmark of Jim Crow-style racial control was that its most visible agents — epitomized by the white hoods and burning crosses of the Ku Klux Klan — were undergirded by a full spectrum of “respectable” state and local leaders, from governors on down to school boards. Such comprehensive efforts meant that broad swaths of the white citizenry perpetrated and tolerated a campaign to maintain segregation.

As targets of that campaign, would-be black voters across the south were regularly stonewalled by local registrars, in myriad and sometimes inventive ways. (Sociologist Charles Payne notes that one woman in the Mississippi Delta reported being rebuffed when she was unable to compose on the spot an original poem about the Constitution.) City Councils passed dozens of ordinances limiting protestors’ ability to gather in public spaces, and privatized or closed playgrounds and pools rather than desegregate them. State legislatures established and funded Sovereignty Commissions to spy on civil rights agitators. Newspaper editors eagerly published activists’ names and addresses, an open invitation to physical reprisals. White business and civic leaders joined Citizens’ Councils, which regularly engineered firings and other economic sanctions. Such multifarious efforts were repeated in hundreds of combinations throughout the 1960s, a fact obscured in accounts that reduce segregation’s defenders to KKK types and stereotyped caricatures of marginal and ill-educated rural sheriffs.

While much has changed since 1963, those forces of resistance did not melt away. Social scientists have demonstrated how, as court decisions over the past two decades have loosened federal oversight over school desegregation plans, changes in local districting policies have led to a steady re-segregation of public schooling. Protests over the recent acquittal of George Zimmerman demonstrate the pervasiveness of the sentiment that self-defense statutes can intersect with racial prejudice to allow young black men to be unjustly murdered without sanction. Following a similar logic, legal scholar Michelle Alexander points to widening racial inequities in mass incarceration, indicting the system as the “new Jim Crow.”

Most palpably, the battle over how — or whether — to heed the lessons of the civil rights struggle played out earlier this summer with the Supreme Court’s striking down of Section 4 of the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts characterized that section’s voting rights provisions as “based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day.” The court’s dissenting opinion, penned by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, sharply rebuffed that assertion, emphasizing the “second-generation barriers” that seek to reconfigure discriminatory racial practices.

As in the 1960s, the power of these barriers resides in their insidious nature, with seemingly benign bureaucratic wrangling accomplishing what outright intimidation often cannot. As Justice Ginsburg contends, failing to grasp why voting rights protections against such measures have succeeded condemns us to repeat history.

This is precisely the history that Dr. King worked tirelessly to overcome. So as we celebrate his ideal of the “beautiful symphony of brotherhood,” remain mindful too of his admonition that we not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” That urgency remains as fierce now as when King stepped to the lectern on the National Mall fifty years ago.

David Cunningham is Associate Professor and Chair of Sociology and the Social Justice & Social Policy Program at Brandeis University. Over the past decade, he has worked with the Greensboro (N.C.) Truth and Reconciliation Commission as well as the Mississippi Truth Project, and served as a consulting expert in several court cases. He is the author of Klansville, U.S.A: The Rise and Fall of the Civil Rights-era Ku Klux Klan and There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence. His current research focuses on the causes, consequences, and legacy of racial violence.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Contemporary victims of creative suffering appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesSocial injustice and public health in AmericaWomen’s Equality DayThe KKK in North Carolina

Related StoriesSocial injustice and public health in AmericaWomen’s Equality DayThe KKK in North Carolina

Social injustice and public health in America

Although there has been much progress in the United States toward social justice and improved health for racial and ethnic minorities in the 50 years since the 1963 March on Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, much social injustice persists in this country — with profound adverse consequences for the public’s health.

Social injustice is manifested in a variety of ways. For example, among African Americans and other people of color, although life expectancy has increased and infant mortality has decreased during the past 50 years, wide gaps remain in these parameters between people of color and whites in the United States. While the rich get richer, the poor (disproportionately including racial and ethnic minorities) get poorer. The ongoing weakening of the social safety net — reflected in cutbacks in the food stamp program and other programs that serve those who have less — worsens the health and well-being of those who are most disadvantaged.

Public health has been defined as “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy.” These conditions include protection of human rights, such as access to quality medical care and preventive services, safe and healthful living and working environments, nutritious and safe food and clean water, and quality education and employment opportunities, as well as participation in the political decisions that affect people’s lives. Social injustice accounts for many of the barriers that remain in assuring these conditions for people to be healthy.

We believe that addressing social injustice and its many health consequences — and making Dr. King’s dream a reality — will require popular and political will and collective action based on a four-pronged approach: protecting human rights, supporting community-based initiatives, promoting sustainable human development, and strengthening the social safety net for those who are most vulnerable.

Protecting human rights: Human rights — globally recognized standards and norms that apply to all people — consist of both civil and political rights, such as the right to liberty and the right to vote, and economic, social, and cultural rights, including rights to education, to work, and to the highest attainable standard of health. Governments have obligations to assure that these rights are guaranteed, especially for racial and ethnic minorities, poor people, and other marginalized populations. Human rights standards prohibit discrimination on the basis of racial or ethnic group, socioeconomic status, and other factors.

Supporting community-based initiatives: Social injustice can also be effectively addressed by strengthening communities and the roles of individual people within communities — not only communities based on geographic location, but also other forms of social networks. Communities provide various types of support in identifying and reducing social injustice, promote participation and engagement of individuals, and facilitate development of groups and organizations to advocate for policies and to take actions to address social injustice. Engaged and mobilized communities are essential to addressing social injustice and its adverse health consequences.

Promoting sustainable human development: Both in the United States and elsewhere, addressing social injustice requires a commitment to sustainable human development, which in turn requires a combination of measures to promote economic growth and measures to promote social justice and reduce inequalities. Equity needs to be made an economic priority with government measures to ensure access to education, to create jobs, and to establish a minimum wage that enables workers and their families to meet their basic needs. Sustainable human development includes ways to ensure that social and physical environments are promoted and protected for current and future generations.

Strengthening the social safety net: Those who are poor and vulnerable depend on social safety-net programs and services that provide income support, facilitate access to health care and education, provide job training and employment opportunities, and serve other functions. In sum, they counteract some of the adverse consequences of social injustice. In recent years in the United States, many of these programs have suffered major cutbacks in financial and political support. This trend needs to be reversed.

As we mark the 50th anniversary of Dr. King’s speech, we as a society need to recommit to the realization of Dr. King’s dream and the achievement of social justice for all people. We all share a common interest in eliminating social injustice. As Dr. King said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Dr. Barry S. Levy and Dr. Victor W. Sidel are co-editors of the second edition of Social Injustice and Public Health, which was recently published by Oxford University Press. They are both past presidents of the American Public Health Association. Dr. Levy is an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Tufts University School of Medicine. Dr. Sidel is Distinguished University Professor of Social Medicine Emeritus at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein Medical College and an Adjunct Professor of Public Health at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Bandage soaked with blood in the shape of America. © Taylor Hinton via iStockphoto.

The post Social injustice and public health in America appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesFamily values and immigration reformWomen’s Equality DayWhy is the relationship between the US and Mexico strained?

Related StoriesFamily values and immigration reformWomen’s Equality DayWhy is the relationship between the US and Mexico strained?

Celebrating Women’s Equality Day

In 1971, when Representative Bella Abzug introduced a joint resolution to Congress creating Women’s Equality Day, she wasn’t likely thinking about women in popular music. After all, the subject is seemingly silly compared to what Women’s Equality Day commemorates—the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which guaranteed women the right to vote.

Though it was likely far from Abzug’s mind, 1971 was in fact an ideal time to think about women in popular music and how their representation in pop culture had shifted over the previous decade or so. In terms of significant releases, it was a banner year for women—in good ways and bad. Although Australian Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman” wasn’t released as a single until 1972, it appeared as a track on her 1971 debut album I Don’t Know How to Love Him. The song went on to become an anthem of the women’s liberation movement.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Less politically oriented but more artistically significant, Janis Joplin’s posthumously released Pearl showed the singer’s expanded range, bringing home the tragedy of a life cut short.

Click here to view the embedded video.

But perhaps the most significant release for divining the progress of women in the United States was Carole King’s Tapestry. The album, King’s second as a solo artist, was a surprise megahit, selling 25 million copies worldwide, winning four Grammy awards, and staying at the top of the Billboard chart for 15 weeks; it remained on the charts for six years. To this day, it’s one of the best-selling albums of all time.

All of these numbers are impressive. Tapestry, though, is more than an album which sold so many copies that used record stores have an overabundance of them to this day. It’s an album that represents a woman, who already had a decade-long career as a songwriter for teen acts, stepping out from behind the scenes as a mature singer-songwriter with a voice of her own.

Carole King’s career began as a songwriter over ten years earlier, when she began writing songs with her then-husband Gerry Goffin. Their relationship—both romantically and professionally—was a sign of the times. While the 1950s promised teen boys rebellion through rock ‘n’ roll, girls faced intense pressure to conform. A much-cited survey conducted by the Saturday Evening Post in 1962 found that 90% of women between the age of 16 and 21 wanted to be married by the age of 22. In the 1950s, the median marriage age for women dropped to just 20, and women were supposed to go straight from their father’s house to their husband’s. If they went to college, they were expected to find a husband by junior year. Though the birth control pill was approved for contraceptive use in 1960, it was almost impossible for unmarried women to obtain.

Certainly, King’s life reflected this reality. She met Gerry while the two of them were students at Queens College, and they married quickly after she became pregnant when she was just 17. Had it not been for a shared ambition to become songwriters, King might have become like one of the songs by groups such as The Chordettes, whose “A Girl’s Work Is Never Done” (1959) shows a teen girl doing endless housework, presumably in preparation for an adult life of more of the same. While King watched her daughter during the day, she also spent hours at the piano, writing songs to which Gerry would add lyrics in the evening.

Click here to view the embedded video.

In 1960, King and Goffin made a breakthrough in their songwriting career with “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” written for The Shirelles, a group of four African-American teen girls. The song outlines the sexual dilemma that teen girls of the time faced: Would a boy love her tomorrow, after they had gone “all the way”? It’s not clear if the song takes place before, or after, the big event, and its ambiguous temporal standpoint probably added to its appeal among teenagers at the time. It also stands out from pop tunes of the time, with a yearning major III chord corresponding with the third line of text, evidence of King’s growing skills as a songwriter.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The success of “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” ushered in an era in which King and Goffin became some of the most in-demand songwriters in the pop charts, writing songs for artists such as Aretha Franklin, Bobby Vee, The Drifters, Little Eva, and The Chiffons. During this time, King remained behind the scenes as a songwriter. (Fittingly, her only hit under her name, “It Might as Well Rain Until September” was a demo released as a single.) Like “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” many of King’s songs at this time dealt with the issues of teen life, from which she wasn’t so far removed. But around her, the musical landscape began to change, and her marriage fell apart.

Though she had already released one solo album, Writer, in 1970, Tapestry marked a departure from her earlier work. Rather than relying on her ex-husband as her lyrical partner, most of the songs were written by King (at the encouragement of her pal James Taylor, who would cover King’s “You’ve Got a Friend”). Even the Goffin/King songs that she “covered” feature a new level of maturity: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” takes on a slow, mournful quality that makes its timeframe no longer so ambiguous.

The album represents something not quite visible in popular music before 1971—and, for that matter, rarely seen since. It marks the presence of a mature, adult woman singing about mature, adult topics in a way that resonated with a very large audience of both men and women who had grown up with rock ‘n’ roll. In many ways, it’s a perfect soundtrack for Women’s Equality Day, not because it proclaims equality in any political way, but because it marks a moment in which a woman received critical acclaim for writing as herself.

Elizabeth K. Keenan received her doctorate in ethnomusicology at Columbia University in 2008. She is writing her first book, Popular Music, Cultural Politics, and the Third Wave Feminist Public, which investigates cultural politics and identity-based movements in US popular music since 1990. She has published in Women and Music, the Journal of Popular Music Studies, and Current Musicology, and has a forthcoming article, co-authored with archivist Lisa Darms, about the Riot Grrrl Collection in Archivaria.

Oxford Music Online is the gateway offering users the ability to access and cross-search multiple music reference resources in one location. With Grove Music Online as its cornerstone, Oxford Music Online also contains The Oxford Companion to Music, The Oxford Dictionary of Music, and The Encyclopedia of Popular Music.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Celebrating Women’s Equality Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationSophie Elisabeth, not an anachronismAnthems of Africa

Related StoriesThe 1812 Overture: an attempted narrationSophie Elisabeth, not an anachronismAnthems of Africa

August 26, 2013

10 questions for David Gilbert

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 27 August 2013, writer David Gilbert leads a discussion on Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis.

What was your inspiration for this book? (His new novel & Sons)

My father and my son.

Photo by Susie Gilbert

Where do you do your best writing?

In my office, late at night, wishing I still smoked.

Which author do you wish had been your 7th grade English teacher?

Harper Lee.

What is your secret talent?

I can stand on my head.

What is your favorite book?

Some days it’s Lolita, other days, Pale Fire.

Who reads your first draft?

A poor unlucky soul who lives in my basement.

Do you prefer writing on a computer or longhand?

Computer. But I do my most inspired writing on Post-Its.

What book are you currently reading? (Old school or e-Reader?)

Old school (not the book), Speedboat by Renata Adler.

What word or punctuation mark are you most guilty of overusing?

I hate the word off. It is an unreasonable hate. And I think the letter k is kind of a jerk. I overuse vague qualifiers, like sort of and kind of (see above). I wish I used exclamation points more but that’s a young man’s game.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

A first-grade homeroom teacher.

Did you have an “a-ha!” moment that made you want to be a writer?

Yes. Unfortunately it was while watching Hardcastle and McCormick on TV, which is a Stephen J. Cannell production (he of the ripping another perfect page from the typewriter, the sheet flying elegantly through the air, passing various awards and diplomas). Ruined me.

Do you read your books after they’ve been published?

No way (the thought alone just made me throw up a little).

David Gilbert is the author of the story collection Remote Feed and the novels The Normals and & Sons. His stories have appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, GQ, and Bomb. He lives in New York with his wife and three children.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only Oxford World’s Classics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 10 questions for David Gilbert appeared first on OUPblog.

Related Stories10 questions for Wayne KoestenbaumWalter Scott’s anachronismsA children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Related Stories10 questions for Wayne KoestenbaumWalter Scott’s anachronismsA children’s literature reading list from Oxford World’s Classics

Women’s Equality Day

Today we celebrate Women’s Equality Day in commemoration of the certification of the 19th Amendment, granting of women’s right to vote throughout the country. Women in the United States were granted the right to vote on 26 August 1920. However, the amendment was first introduced many years earlier in 1878 due to the efforts of the nineteenth-century women suffragists.

Here are some little-known facts about four of the remarkable leaders of the suffragist movement:

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1818 – 1902)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1818 – 1902)

Of the Bible, Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote, “I know no other books that so fully teach the subjection and degradation of women.” To that end, in 1895 and 1898, Stanton published her two volumes of the Woman’s Bible which highlighted scriptural passages that dealt with women and offered commentary. The publication of the Woman’s Bible caused some fracturing of the woman’s movement. While some women welcomed this publication, many others were shocked and separated themselves from Stanton.

The opening of the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments, likely written mostly by Stanton for the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention on woman’s rights, begins with the ringing phrase: “We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men and women are created equal.”

In Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s most famous essay, “Solitude of Self” (1892), which expresses thoughts that resonate then and now, she urged each woman not to lean on a man for protection or support but to achieve a sense of self and responsibility and claim “her birthright to self-sovereignty.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton bore and raised seven children.

At the 1848 Seneca Falls convention it was Mott, a Quaker minister, who was the main attraction, and it was her name that enticed people to the meeting. At the time, she was one of the most famous women in America. Yet despite her open-minded, often radical ideas, she opposed the demand for woman suffrage in the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments.

So principled and ardent were Lucretia Mott and her husband James in their stance against slavery that they refused to use cotton, cane sugar, and any goods or products produced by slave labor.

So skillful a debater and so assertive in her beliefs was Lucretia Mott that when she visited President John Tyler, he told her he wanted to hand her over to debate John C. Calhoun, one of the South’s most ardent pro-slavery defenders.

Lucretia Mott and her husband James helped to found Swarthmore College. She bore six children.

Susan B. Anthony (1820 -1906)

Susan B. Anthony (1820 -1906)

Anthony was the only one of these four women who never married. So dedicated and relentless was she in demanding woman’s rights that people dubbed her “Little Napoleon.” She occasionally expressed frustration that her fellow suffragists who were mothers could not devote themselves fully to the cause of woman’s rights as she was doing.

Anthony loved fine fashion. Thus, unlike Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucy Stone, she only reluctantly adopted the bloomer outfit that freed women from wearing corsets and the fashionable, voluminous dresses that restricted women’s freedom of movement.

Lucy Stone (1818 – 1893)

Lucy Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts and one of the first in the nation to earn a college degree, graduating from Oberlin Collegiate Institute in 1847 at the age of twenty-nine.

When Lucy Stone finally married in 1855 at the age of thirty-six, she and husband Henry Blackwell wrote and published a “Protest” that denounced the laws that restricted married women’s lives. A year later, she decided to keep her maiden name, arguing that since men could keep their names when married, why not women? Years later, married women who kept their maiden names were known as “Lucy Stoners.” Stone bore two children, though one died at birth.

From 1870 until her death in 1893, Stone edited and published the Woman’s Journal, the most enduring, influential nineteenth-century women’s suffrage newspaper in this country. It continued to be published (under a different name after 1917) until women finally won the right to vote in 1920.

Lucy Stone spent the first decade of her career as a lecturer for both abolition and for woman’s rights. She was a follower of William Lloyd Garrison and, like him, in the 1850s was a disunionist, urging northern states to separate from southern states in order to create a union without slavery.

In the controversy over the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of the Constitution giving black men citizenship and the right to vote, Lucy Stone supported both amendments while Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony opposed them, feeling women deserved those rights before black men.

Though Lucy Stone was one of the most famous women in America and devoted her life to fighting for woman’s rights, she does not appear in the marble statue in our nation’s Capitol which honors three nineteenth-century women suffragists: Anthony, Stanton, and Mott. Stone and her American Woman Suffrage Association (a rival to Anthony and Stanton’s National American Woman Suffrage Association) were on the wrong side of history and also virtually absent from three enormous volumes produced by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, History of Woman Suffrage, covering the nineteenth-century woman’s movement. Stanton’s daughter, Harriott, was the one to insist that the second volume include a chapter on Stone and the AWSA, or they would have been left out altogether.

Sally G. McMillen is the Mary Reynolds Babcock Professor of History at Davidson College. She is the author of Motherhood in the Old South and Southern Women: Black and White in the Old South, and Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women’s Rights Movement. She lives in Davidson, North Carolina.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credits: (1) Portrait of Lucy Stone, 1881. Painted by Ida Bothe. From Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Mrs. Charles F. D. Belden, niece of Lucy Stone, to the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in 1966. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902), circa 1880. Photographer unknown. US Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Lucretia Coffin Mott (1793 – 1880), 1842. Oil on canvas by Joseph Kyle. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (4) American civil rights leader Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906), Between ca. 1890 and 1906. Photograph by Frances Benjamin Johnston. From Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Women’s Equality Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe black quest for justice and innocenceReparations and regret: a look at Japanese internmentKrakatoa

Related StoriesThe black quest for justice and innocenceReparations and regret: a look at Japanese internmentKrakatoa

Shakespeare’s hand in the additional passages to Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy

Why should we think that Shakespeare wrote lines first published in the 1602 quarto of The Spanish Tragedy, a then-classic play by his deceased contemporary Thomas Kyd? Our answer starts 180 years ago, when Samuel Taylor Coleridge—author of ‘Kubla Khan’ and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner—said he heard Shakespeare in this material.

Because Coleridge is among our best critics, you would guess his insight would be tested, and widely. But two things worked against him. First was an Elizabethan record: in 1601 and 1602, theatrical entrepreneur Philip Henslowe paid the playwright Ben Jonson for revising The Spanish Tragedy. Second is the Additional Passages themselves: they’re uneven, full of awkward phrases that don’t sound like Shakespeare. For almost two centuries, then, these 325 lines of verse and prose have remained in a kind of Shakespearean hinterland. Most readers acknowledge their real force and passion, but at the same time recoil from their defects.

Most, but not all. During the past century, a scholar named Warren Stevenson kept the argument alive with his thesis, an essay, and finally a book arguing for Shakespeare’s authorship of the material. Supporting evidence came from Hugh Craig, who demonstrated, first, that the Additional Passages were not in Jonson’s style, and, next, that their vocabulary was in fact like Shakespeare’s. Then, in a wide-ranging essay of 2012, Brian Vickers summarized the existing evidence and adduced a number of extremely striking parallels between the Additional Passages and Shakespeare’s known works. The parallels Vickers points to, which include both things Shakespeare had already written and things he would go on to write, make it incredibly difficult to imagine that anyone else wrote the Additional Passages.

What to do with Henslowe and Jonson, though? And what about the extremely rough bits? The first problem goes away when one realizes that the Additional Passages must have been in existence by 1598-1599, for in the latter year they were parodied and echoed by the playwright (and Shakespeare admirer) John Marston in two of his plays. In 1601 and 1602, therefore, what Henslowe was paying Jonson for was different work on this classic play. It’s possible that Henslowe was prompted to do so by the impending quarto. Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a revenge tragedy on a story that Kyd had already treated, also may have influenced him.

But how to explain the bad writing in the Additional Passages? My argument, published in the September 2013 issue of Notes and Queries, is that what’s pushed us away from the Additional Passages for so long is their closeness to Shakespeare’s own pen. That is, that what we’ve taken as bad writing comes in part from Shakespeare’s bad handwriting.

I begin by noticing that the Additional Passages are absolutely consistent with Shakespeare’s spelling as it survives both in the three pages of the manuscript playbook, Sir Thomas More, and in various corruptions in the quartos and Folio of Shakespeare’s works. Scholars like John Jowett and Eric Rasmussen have been instrumental in helping us to understand such material. Shakespeare was a creative speller, students everywhere will be happy to learn. And although he wasn’t alone in spelling words the way he did, there are nevertheless 24 categories of correspondence between tendencies we’ve identified with his practice and the Additional Passages. In short, this material is spelled the way Shakespeare would have spelled it.

But the corruptions in this material, I go on to argue, come largely from the fact that Shakespeare’s handwriting was difficult for the copyist or printing-house compositor to make out. What got printed in various places, then, is a misreading of a messy text. Here is one example that happens to bring in both spelling and handwriting. In the long fourth Additional Passage, Hieronimo (the main character) enters, distracted to the point of madness, and says:

I prie through euery creuie of each wall,

Looke on each tree, and search through euery brake . . .

Now, ‘creuie’ is an extremely rare word (if it’s even a word). It’s more likely that the source for the quarto featured some form of the word ‘creuice’ (here spelled in the Elizabethan manner). Aaron in Titus Andronicus, for example, says ‘I pried me through the crevice of a wall.’ Of course, the letter ‘c’ could have been omitted by accident. But what I think happened was that the copy text contained a characteristic Shakespearean spelling. We know, from the Sir Thomas More pages and elsewhere, that he routinely dropped the final ‘e’ from words usually ended ‘-ce’. So: ‘ffraunc’ for ‘fraunce,’ ‘offyc’ for ‘office,’ and so forth. In the above passage, I believe that the copyist or compositor encountered the word ‘creuic’ and, not being familiar with Shakespeare’s habit, misread the small ‘c’ as an ‘e’.

Yet in the end, it’s not necessary to accept the argument about spelling or handwriting in order to see that these Passages are by Shakespeare. As the Vickers essay makes clear, the Additional Passages are written with the very words, phrases, imagery, and ideas that Shakespeare had used before the second half of the 1590s (when the Passages appear to have been penned) and would return to throughout his subsequent career. Above all, they give passionate voice to grief. And in this, they remind us of such characters as Titus, Venus, Shylock, and Leonato, all of whom grieve the loss (sometimes figurative) of someone younger. Taken in sum, the parallels with Shakespeare’s known work argue overwhelmingly for his authorship of the Additional Passages. No one else we know of was capable of writing them. I believe that evidence will show that they were composed after A Midsummer Night’s Dream and before Much Ado About Nothing, and as bravura pieces for Richard Burbage, the lead actor of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men later celebrated for his portrayal of Hieronimo.

Professor Douglas Bruster teaches English at the University of Texas at Austin. He is a trustee of the Shakespeare Association of America, and editorial board member of Shakespeare Quarterly and Studies in English Literature 1500-1900. He is the author of “Shakespearean Spellings and Handwriting in the Additional Passages Printed in the 1602 Spanish Tragedy” (available to read for free for a limited time) in Notes & Queries.

Founded under the editorship of the antiquary W J Thoms, the primary intention of Notes and Queries was, and still remains, the asking and answering of readers’ questions. It is devoted principally to English language and literature, lexicography, history, and scholarly antiquarianism.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Thomas Kyd – The Spanish Tragedie, or, Hieronimo is mad againe. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Portrait of Shakespeare – the so called Cobbe portrait – authenticity disputed! Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare’s hand in the additional passages to Kyd’s Spanish Tragedy appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Beatles and “She Loves You”: 23 August 1963A Who’s Who of the Edinburgh FestivalMoney, prices, and growth in pre-industrial England

Related StoriesThe Beatles and “She Loves You”: 23 August 1963A Who’s Who of the Edinburgh FestivalMoney, prices, and growth in pre-industrial England

Ready to study UK law?

Are you one of the 17,000 students about to embark on a law course in the UK? Why not get your teeth stuck into our quiz to find out how clued up you are before you start at university? We have so many preconceptions about the law from what we see on the TV and through films — but how much do you really know?

Are you one of the 17,000 students about to embark on a law course in the UK? Why not get your teeth stuck into our quiz to find out how clued up you are before you start at university? We have so many preconceptions about the law from what we see on the TV and through films — but how much do you really know?

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Martin Partington is Emeritus Professor of Law, Bristol University and author of Introduction to the English Legal System 2013-2014, Eighth Edition. For 5 years, he was Law Commissioner, and was retained by the Law Commission as a special consultant in order to complete its major programme of work on the reform of housing law until 2008. He was a special consultant to the Leggatt Review of Tribunals in 2001. He has been a member of numerous committees and bodies working within the English Legal System. In 2011-2012 he was a consultant to the Public Administration Select Committee of the House of Commons. He was appointed CBE in 2002, elected a Bencher of Middle Temple in 2006, and made an honorary Queens Counsel in 2008. For more fascinating facts on law, take a look at some gems taken from Geoffrey Rivlin’s book.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Photo by Alice Northover of definition in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary, filtered with Instagram.

The post Ready to study UK law? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemmaIs Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?Remembering the slave trade

Related StoriesThe Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemmaIs Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?Remembering the slave trade

Krakatoa

I know that if I ask someone to name a single volcano, the chances are that they will hit upon Krakatoa; such is the degree to which the cataclysmic 1883 blast of the volcano has etched itself into the public consciousness. Remotely located in the Sunda Strait, between the Indonesia islands of Sumatra and Java, the islands that made up the long-dormant volcano were pretty much unheard of prior to August, 130 years ago, when all hell broke loose. In fact the locals had been aware that something was not quite right with Krakatoa for quite a while. Swarms of small earthquakes had been periodically shaking the volcano for years until, in May 1883, the bursting open of steam vents on the flanks testified to the presence of fresh magma close to the surface. Activity increased in fits and starts over the next few weeks until, by mid-June, violent blasts were expelling columns of ash and pumice several kilometres into the atmosphere.

The climactic, paroxysmal, phase of the eruption began in earnest just after mid-day on the 26th of August, when a sequence of titanic explosions, heard all over Java, propelled a column of black ash and pumice to heights of more than 25 km. Even these, however, were dwarfed by what happened the following day. Although difficult to be certain, it looks as if the expulsion of vast quantities of magma had left the volcano structurally unstable so that it began to collapse in upon itself, allowing seawater to pour into the magma chamber. The violent fusion of molten rock and cold water triggered a detonation so ear-splitting that some have speculated that it may have been the loudest noise in recorded history. Whether true or not, its volume was sufficient to transmit the sound an astonishing distance; as far, in fact, as Alice Springs, 4,600km away in the heart of Australia. To put this in a European perspective, if the explosion had occurred in the Canary Islands, it would have been heard as far away as Liverpool and Copenhagen. Such was the shock to the planet’s atmosphere that the resulting pressure spike registered on barometers around the world as it circled the planet four times before dissipating.

At the same time that the detonation blasted magma upwards, it spawned colossal flows of hot ash, pumice, and debris that cascaded down Krakatoa’s flanks, displacing the surrounding waters of the Strait and promoting the formation of giant tsunamis. Within minutes, more than 160 communities on neighbouring coastlines were swamped by the sea. For the inhabitants, there was no escape from the unstoppable waves. At Anjer, on the east coast of Java, they were as high as the 40m lighthouse, which they brought crashing down. In all, this terrible conspiracy of the gods of the sea and the underworld — Neptune and Vulcan — consigned more than 36,000 people to their graves, making the eruption the second most lethal of the last 250 years.

The legacy of the blast did not, however, end there; the millions of tonnes of fine ash and sulphur particles ejected into the atmosphere reflecting sunlight back into space and causing temperatures across the globe to plunge by more than 1°C. Astonishingly, a similar cooling effect on the oceans could still be detected well into the twentieth century. Another bequest of the dust and gas scattered throughout the stratosphere was a spectacular atmospheric display that incorporated crimson, purple, and yellow sunsets alongside coloured suns and moons including – in the latter case – the blue variety.

However unprecedented the 1883 blast may have seemed to those in Europe and North America, to whom newly installed undersea telegraph cables brought news of the catastrophe within hours, it is worth bearing in mind that, from a geological point of view, the Krakatoa eruption was pretty small beer. In fact, it wasn’t even the biggest of the 19th century; that honour going to the 1815 eruption of another Indonesia volcano, Tambora, which was 3–4 times bigger and that killed approaching 100,000 people. This event had an even greater impact on the global climate, to the extent that the following year is renowned — in Europe and North America — as the ‘year without a summer’; an episode of widespread crop failures that triggered the last, great, subsistence crisis in the western world. Looking further back in time, the Krakatoa explosion is dwarfed by the great super-eruptions that shake the planet a couple of times every 100 millennia. The stupendous blast that tore open a 100 km hole in Sumatra around 74,000 years ago, for example, dumped ash across one percent of the planet’s surface, plunged our world into volcanic winter, and was more than 100 times bigger.

The anniversary of the 1883 Krakatoa blast is perhaps a good time to think about what future volcanic activity may hold in store for us, particularly as it is now nearly a quarter of a century since the last eruption big enough to give a volcanologist, like myself, sweaty palms. As regards where the next big bang will occur, your guess is as good as mine. Somewhere out there beneath one of the world’s 1500 or so active volcanoes I can guarantee, however, that pressure is building prior to unleashing an explosion that will put that of 1883 in the shade. Whether we have to wait a year, a decade or a century or more, it really is just a matter of time.

Bill McGuire is an academic, science writer, and broadcaster. He is currently Professor of Geophysical and Climate Hazards at UCL. Bill was a member of the UK Government Natural Hazard Working Group established in January 2005, in the wake of the Indian Ocean tsunami, and in 2010 a member of the Science Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE) addressing the Icelandic volcanic ash problem. He was also a contributing author on the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC) report on extreme events. His books include Waking the Giant: How a changing climate triggers earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes, Surviving Armageddon: Solutions for a Threatened Planet, and Seven Years to Save the Planet. Read his previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Krakatoa eruption 2008. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Krakatoa appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum10 facts about Galileo GalileiThe Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemma

Related StoriesThe ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum10 facts about Galileo GalileiThe Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemma

August 25, 2013

Why is the relationship between the US and Mexico strained?

Relations between the United States and Mexico, in spite of the two countries’ geographical proximity, are nothing but complex. While intimately linked, the negativity with which Mexico is regarded by American lawmakers and citizens has prevented the formation of a strong, bilateral alliance thus far. Shannon O’Neil, author of Two Nations Indivisible: Mexico, the United States, and the Road Ahead, analyzes the social, political, and economic dynamics at play between both countries, and evaluates prospective changes that could be made in the 21st century.

On changing immigration patterns in the United States:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the prospects of a successful partnership between the United States and Mexico:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On the impact of Mexico’s emerging security issues:

Click here to view the embedded video.

On Mexican domestic politics and their influence on the United States:

Click here to view the embedded video.

Shannon K. O’Neil is Senior Fellow for Latin American Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and author of Two Nations Indivisible: Mexico, the United States, and the Road Ahead. A frequent media commentator on foreign relations, she has published her work in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, and other periodicals.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why is the relationship between the US and Mexico strained? appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesThe Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemmaCross-border suspicions and law enforcement at US-Mexico borderIs Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?

Related StoriesThe Cuadrilla fracking site: a policing dilemmaCross-border suspicions and law enforcement at US-Mexico borderIs Edward Snowden a civil disobedient?

10 facts about Galileo Galilei

One of the most prolific scientists of all time, Galileo’s life and accomplishments has been studied and written about in detail for centuries. From his discovery of the moons of Jupiter to his fight with Pope Urban VIII, noted authors and playwrights have been fascinated with both Galileo’s life and contributions. With the addition of the Galileo Galilei article to Oxford Bibliographies in the Renaissance and Reformation, I’d like to share 10 interesting facts about Galileo.

One of the most prolific scientists of all time, Galileo’s life and accomplishments has been studied and written about in detail for centuries. From his discovery of the moons of Jupiter to his fight with Pope Urban VIII, noted authors and playwrights have been fascinated with both Galileo’s life and contributions. With the addition of the Galileo Galilei article to Oxford Bibliographies in the Renaissance and Reformation, I’d like to share 10 interesting facts about Galileo.

Galileo was have said to drop two cannon balls of different masses from the leaning tower of Pisa to demonstrate that their speed of descent was independent of their mass. Many people believe this story to be untrue though since its only source was Galileo’s secretary.

Galileo never married and had all his children out of wedlock with Marina Gambia, whom he met on a trip to Venice.

While many remember Galileo’s confrontation with the church, many forget that both his daughters joined the convent of San Matteo in Arcetri and remained there for the rest of their lives. Galileo even went as far as help out in the convent, repairing windows and making sure that the convent clock was in order.

Joseph Nicolas Robert-Fleury painted “Galileo before the Holy Office,” a representation of the scientist speaking before the clergy currently on display at the Luxembourg Museum.

Galileo was an accomplished lutenist, learning from his father, Vincenzo Galilei, who was a composer and music theorist.

While Galileo firmly believed in Copernicus’s theory that the Earth was not the center of the universe, he did not believe in his Kepler’s theory that the moon caused the tides.

In the last year of his life, when he was totally blind, Galileo designed an escapement mechanism for a pendulum clock called Galileo’s escapement.

German dramatist Bertolt Brecht wrote a play about Galileo entitled Life of Galileo which first appeared on Broadway in 1947 with Charles Laughton as the title character. Brecht worked closely with Laughton and re-worked the final version of the play with him. The play was adapted to the screen in 1975 with Chaim Topol (listed as Topol) as the lead and Sir John Gielgud as a Cardinal Inquisitor. The latest revival of the play is a 2012 off-Broadway production in which F. Murray Abraham played the lead role.

The song “Galileo” is the biggest hit of the folk group Indigo Girls. The song is about reincarnation through the lens of the story of Galileo’s role in the scientific revolution.

The middle finger of Galileo’s right hand is currently on exhibition at the Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy.

Matt Dorville works at Oxford University Press and is co-Founder of Critics and Writers, a site that aggregates book reviews, follows writers on tour, and highlights independent bookstores.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Galileo Galilei, 1636, by Justus Sustermans. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 10 facts about Galileo Galilei appeared first on OUPblog.

Related StoriesTen facts about toastsTen ways to use a bibliography100th anniversary of the first crystal structure determinations

Related StoriesTen facts about toastsTen ways to use a bibliography100th anniversary of the first crystal structure determinations

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers